Abstract

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) is widely used as a neurotoxin in several models of Parkinson’s disease in mice. MPTP is metabolized to 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), which is a mitochondrial toxicant of central dopamine (DA) neurons. There are species, strain, and age differences in sensitivity to MPTP. Simultaneous measurement of the MPTP active metabolite MPP+ and dopamine (DA) in the brain would be helpful in mechanistic studies of this neurotoxin. The objective of this study was to develop a liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS) method for analysis of MPTP and MPP+ in brain tissue and correlate these in the same sample with changes in DA measured via HPLC coupled with electrochemical detection. Twenty-five C57BL/6J7 8-week old female mice were used in the study. Mice were given a single subcutaneous injection of MPTP (20 mg/kg) and were sacrificed 1, 2, 4, or 8 h later. Zero time control mice received an injection of 0.9% normal saline (10 ml/kg) and were killed 1 h later. Brains were rapidly harvested and quickly frozen, and microdissected brain regions were placed in 0.1 M phosphate-citric acid buffer containing 20% methanol (pH 2.5). A new LC/MS method was successfully developed that utilized selected reaction monitoring (SRM) of MPP+ m/z 170→127, 170→128, and 170→154 fragmentation for quantitation and area ratios (m/z 127)/(m/z 128) and (m/z 154)/(128) for identity confirmation. A similar SRM strategy from m/z 174 was unable to detect any significant levels of MPTP down to 0.4 ppb. According to this method, MPP+ was detected in the nucleus accumbens (NA) and the striatum (ST), with the levels in the NA being 3-times higher than those in the ST. The advantage of this approach is that the tissue buffer used in this procedure allowed concurrent measurement of striatal DA, thus enabling direct correlation between accumulation of tissue MPP+ and depletion of DA concentrations in discrete regions of the brain.

Keywords: MPTP, MPP+, LC/MS/MS, dopamine, HPLC

Introduction

1-Methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) is a neurotoxic chemical capable of selective destruction of nigrostriatal dopaminergic (NSDA) neurons located in the midbrain substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc). It was initially discovered as a contaminant of the synthetic opioid ‘designer drug’ 1-methyl-4-phenyl-4-propionoxypiperidine (MPPP) after use of the illicit drug caused Parkinsonism in drug addicts (Davis et al. 1979; Langston et al. 1983). Since then, MPTP has been used extensively in toxin-induced primate and rodent models of Parkinson’s disease (for reviews see Di Monte and Langston 2000; Przedborski et al. 2001; Jackson-Lewis and Smeyne 2005). There is sufficient evidence that MPTP by itself is not neurotoxic, but its toxicity is attributed to its active metabolite 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+). The lipophilic MPTP is widely distributed in the body and also rapidly crosses the blood–brain barrier. In the brain MPTP is oxidized by monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) to produce an intermediate, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-2,3-dihydropyridinium (MPDP+), which then auto-oxidizes to the dopaminergic neuron toxicant MPP+ (Salach et al. 1984; Dauer and Przedborski 2003). In the brain, this biotransformation occurs in MAO-B rich cells, especially glial cells. Once formed, MPP+ crosses the glial cell membranes into the extracellular fluid via a yet unknown mechanism and is selectively taken up by NSDA neurons causing mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death. MPP+ formed outside the brain does not cross the blood–brain barrier.

The neurotoxicity of MPTP varies widely between and within species. It is neurotoxic in primates, whereas in rodents only specific strains of mice, particularly C57BL/6 mice, are sensitive (Filipov et al. 2009). Moreover, central dopaminergic neurons in mice are differentially susceptible to MPTP neurotoxicity (Behrouz et al. 2007), suggesting possible regional differences in conversion of MPTP to MPP+. Knowledge of MPTP toxicity is still evolving, and an understanding of its neurotoxic mechanism would be facilitated by simultaneous measurement of its stable toxic metabolite MPP+ and neurochemicals associated with DA synthesis, storage, and metabolism in different brain regions.

Liquid chromatography-tandem quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with electrospray ionization in positive mode (ESI+) was therefore employed as a means of quantifying the conversion of MPTP to MPP+ in discrete brain regions while specifically uniting this analytical technique with existing high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) assays for DA (Lindley et al. 1990). The objective of this study was therefore to develop an LC-MS/MS method utilizing the same tissue suspension buffer (0.1 M phosphate-citric acid buffer containing 20% methanol, pH 2.5) used for neurotransmitter HPLC analysis so that changes in MPP+ and DA could be correlated in the same sample. In addition, this method enables a simple rapid analysis with prospects for analyzing other amine neurotransmitters such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin), epinephrine, norepinephrine, and their metabolites in brain samples collected in the same manner.

Materials and methods

Reagents

MPP+ was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) as MPP+ iodide (1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium iodide), characterized as ≥ 98% pure by HPLC. MPTP was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich as the free base, molecular weight 173.25.

Animals

Twenty-five C57BL/6J female mice of 7–8 weeks of age were used in this study. Mice were housed four mice per cage, allowed access to food and water ad libitum, and housed in a room at 25°C with a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on 06:00 h). MPTP-treated mice were kept in a room separate from controls under the same environmental conditions to ensure that controls were not contaminated with the neurotoxin. Animals were divided into five groups of five animals per group, each group representing one of the following time points: zero time saline-injected controls and 1, 2, 4, and 8 h post-MPTP injection. All procedures were approved by the Michigan State University Animal Care and Use Committee (AUF # 08/08-123-00).

MPTP administration

This experiment utilized a murine model of acute MPTP administration. This protocol has been shown to cause a significant reduction of DA in axon terminals of NSDA neurons 8 h post-MPTP administration and is commonly used in our laboratory (Behrouz et al. 2007). Neurotoxin-treated mice received a single injection of MPTP (20 mg/kg) subcutaneously (s.c.). Five mice from each group were killed by decapitation at 1, 2, 4, or 8 h following neurotoxin administration. Zero-time control mice were injected with 0.9% saline (10 mL/kg) and were killed 1 h later. Following decapitation, brains were immediately removed from the skull and frozen on dry ice.

Brain tissue preparation

Consecutive frozen coronal sections (500 μm) were prepared throughout the rostrocaudal extent of the brains using a cryostat set at −10°C (CTD-Model Harris, International Equipment Co., Needham, MA). Micropunches of the striatum (ST) and nucleus accumbens (NA) were collected for MPP+, MPTP, and DA determination according to the method of Palkovits (1973; 1983). At ~ +1.42 mm anterior to Bregma (Franklin and Paxinos 1996) an 18 gauge circular punch tool (1 mm inner diameter) was used to sample ST and a 21 gauge circular punch tool (0.5 mm inner diameter) was used to sample the NA. Brain tissue samples were placed in 50 μL of tissue buffer (0.1 M phosphate-citric acid buffer containing 20% methanol, pH 2.5) and centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 1 min to pellet the tissue. Tissue pellets were sonicated using three 1 s bursts (Sonicator Cell Disruptor, Heat Systems-Ultrasonic, Plainview, NY) and samples re-centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 1 min. The supernatant was drawn off and brought to 100 μL with tissue buffer. The brain tissue pellets were placed in 100 μL of 1 N NaOH to determine protein content using a colorimetric protein assay (Lowry and Rosebrough 1951). Samples were centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 3 min, and then transferred to glass vials and frozen (−20°C) until MPP+, MPTP, and DA analyses. Individual sample concentrations of DA were normalized to protein content of brain tissue.

LC-MS analyses of MPTP and MPP+

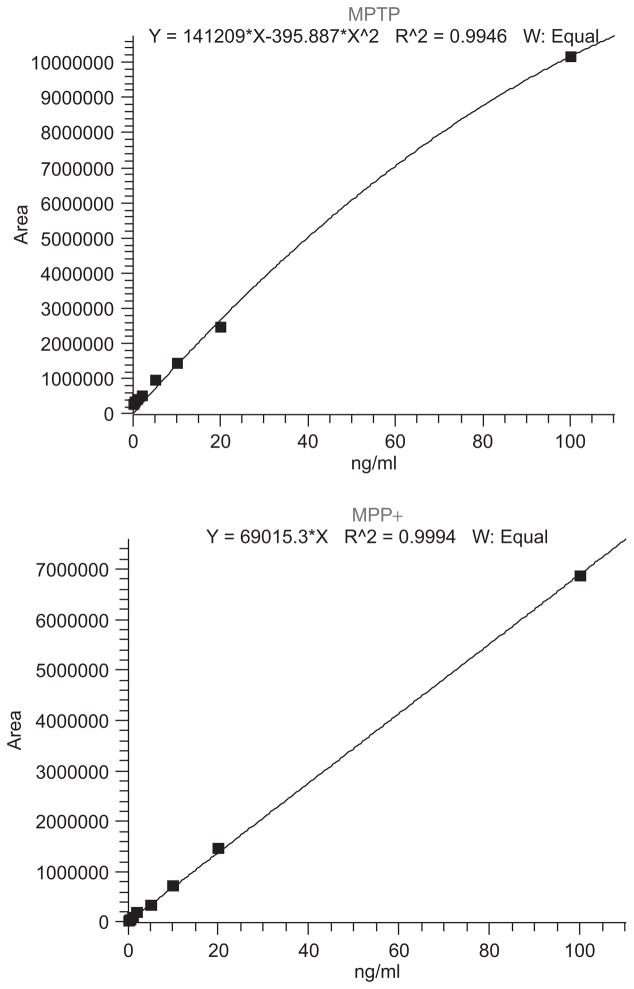

Ten microliters of each sample supernatant were injected onto a Thermo-Finnigan Surveyor HPLC connected to a Thermo-Finnigan TSQ Quantum ESI-MS/MS detector (Thermo-Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Tables 1 and 2 summarize critical parameters for gradient HPLC and mass spectrometry, respectively. A series of MPP+ and MPTP standards (0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 100, 1000 ng/mL) were measured, and the peak area of each sample was plotted against the known concentrations of individual standards without internal standard. This method of external standardization depends on the precision and repeatability of the HPLC autosampler. Thermo claims < 1.0% relative standard deviation (RSD) at 5 μL injection volume and greater for the Surveyor HPLC, thereby justifying this approach. Typical calibration plots for MPTP and MPP+ are shown in Figure 1. The linear equation of the line resulting from this plot was used to determine sample MPP+ concentrations by interpolating the peak area of samples in the equation of the line. The peak areas of standards and samples were measured using the analytical software Xcalibur (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). Individual sample concentrations of MPP+ and MPTP were normalized to protein content of brain tissue.

Table 1.

Optimized mass spectrometer settings for detection of MPTP and its metabolite MPP+.

| Scan width | 0.5 u |

| Dwell time per fragmentation | 0.5 |

| Collision energy ranges | 11–52 |

| Quadrupole 1 peak width (FWHM) | 0.7 |

| Quadrupole 3 peak width (FWHM) | 0.7 |

| Tube lens offset energy | |

| MPP+ | 78 |

| MPTP+H+ | 63 |

u = unifoed atomic mass unit; FWHM = full width [at] half maximum.

Table 2.

Optimized HPLC gradient settings for detection of MPTP and its metabolite MPP+.

| Time, min | A% | B% | μl/min |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 95 | 5 | 150 |

| 1 | 95 | 5 | 150 |

| 5 | 20 | 80 | 300 |

| 6 | 20 | 80 | 300 |

| 6.5 | 95 | 5 | 300 |

| 10 | 95 | 5 | 300 |

Solvent A = 0.1% acetic acid (aqueous), Solvent B = methanol. HPLC column = Surefire 2.1 mm C18 (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The injection volume was 10 μl.

Figure 1.

Typical calibration curves for MPTP (top) and MPP+ (bottom). Target SRM fragmentation peak area sums (for m/z 174→44, 77, 91, and 115 (top) and170→127, 128, and 154 (bottom)) were plotted as functions of concentration, ng/ml. Equations are listed at the top of each curve, along with coefficients of determination, R2. (See colour version of this figure online at www.informahealthcare.com/txm)

MPP+ fragment ions were m/z 127.0, 128.0, and 154.0, and quantitation was based on the sum of the individual areas for m/z 170→127, 170→128, and 170→154 fragmentations, with the m/z 170→127 and 170→154 fragmentations used as qualifiers.

HPLC analysis of DA

A Waters HPLC system (Milford, MA) was equipped with a Brownlee Spheri-5 RP18 column (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) and run isocratically with an aqueous mobile phase including 15% methanol, 0.01% sodium octylsulfate at pH 2.65. Electrochemical detection required equipment from ESA (part of Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA), including an ESA 5011 Analytical Cell, ESA 5021 Conditioning Cell, and ESA Coulochem 5100A, the last of which was set in positive polarity with an applied potential of 0.4 volts.

Statistical analysis

SigmaStat software version 3.1 (SysStat Software, Point Richmond, CA) was used to make statistical comparisons among groups using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). If a significant interaction was detected by ANOVA, Tukey’s post-hoc test was used for multiple comparisons and differ-ences (Miller and Miller 2000). Differences with a probability of error of less than 5% were considered statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05). Data sets that did not pass tests of normality were analyzed with SigmaStat software version 3.1 (SysStat Software, Point Richmond, CA) using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance on Ranks (Miller and Miller 2000). If a significant interaction was detected, Tukey’s post-hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. Differences with a probability of error of less than 5% were considered statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05).

Results

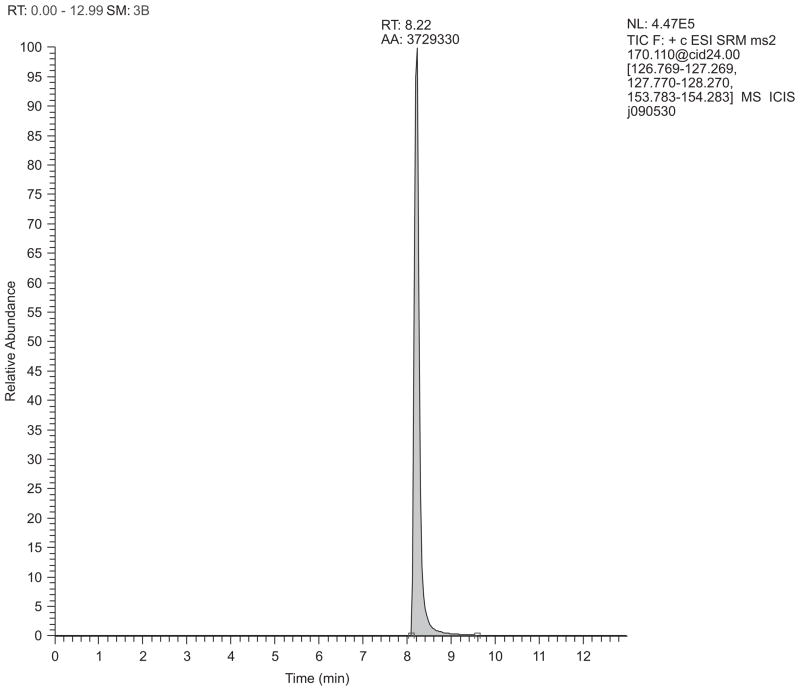

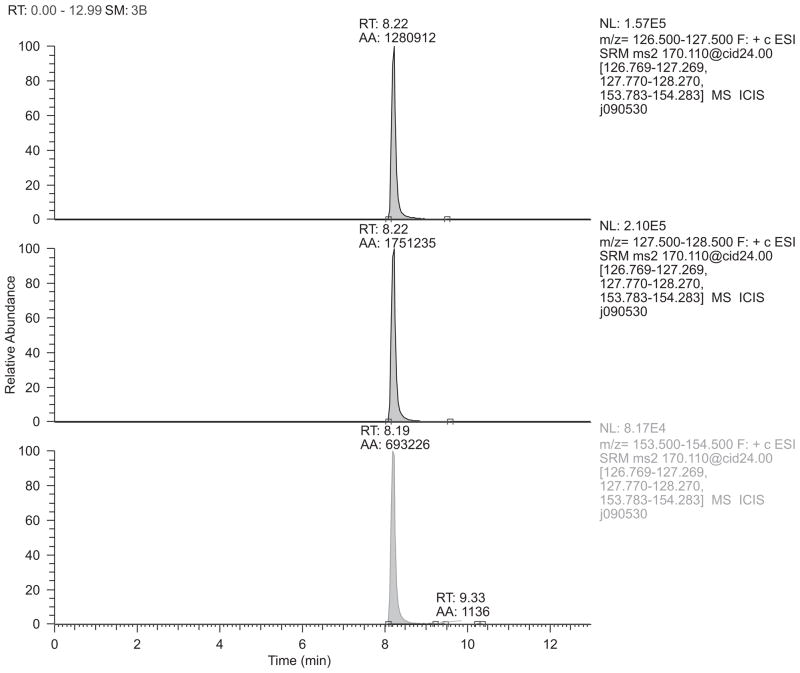

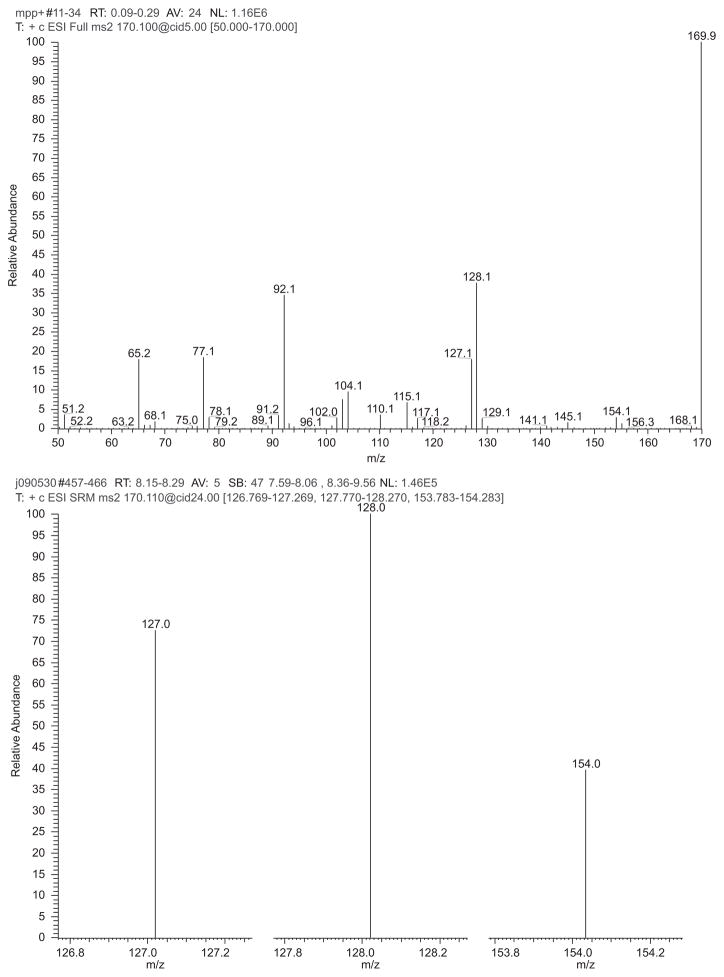

LC-MS gave reasonable chromatography of MPP+ with selective reaction monitoring (SRM) detection of the m/z 170→127, 128, and 154 ions (Figure 2). These ions occurred with relative areas of 1.0, 1.37, and 0.54, respectively, as seen in the ion chromatographs in Figure 3. Figure 4 (top panel) shows the product ion spectrum of MPP+ m/z 170 at low collision energy (5.00 V) intended to show principal ions with relatively good distribution over the m/z 50–175 range. This spectrum is in good agreement with published results of Hows et al. (2004) and Zhang et al. (2008). Figure 4 (bottom panel) shows the SRM spectrum of the three principal ions acquired under the conditions of MPP+ detection. Scheme 1 provides a hypothetical model accounting for generation of the m/z 154, 128, and 127 fragments of MPP+.

Figure 2.

Detection of MPP+ by LC/MS/MS. Shown is a total ion chromatogram (TIC) for a 100 ng/mL standard of MPP+, derived by combining selected reaction monitoring (SRM) data for the fragmentations m/z 170→127, 170→128, and 170→154. Chromatography utilized a Luna 3u C18(2) 150 × 2.0 mm column with 95% solvent A/5% solvent B (initial) at 300 μL/min, held until 2-min, then linearly changing to 50% A/50% B by 5-min. This composition was held until 11-min, followed by a linear gradient returning to the initial conditions by 12-min. Initial conditions were held until 15-min to enable re-equilibration of the column. Solvent A = 0.1% acetic acid made up in HPLC-grade water, B = HPLC-grade methanol. Injection volume = 10 μL.

Figure 3.

Detection of MPP+ by LC/MS/MS. Shown are individual ion chromatograms for the 100 ng/ml (ppb) standard of MPP+, specifically for selected reaction monitoring (SRM) data for the fragmentations m/z 170→127, 170→128, and 170→154, top-to-bottom. (See colour version of this figure online at www.informahealthcare.com/txm)

Figure 4.

MPP+ mass spectra. TOP, full scan product ion mass spectrum of m/z 170 ion obtained during direct infusion of 10 μg/mL MPP+. Bottom, SRM mass spectrum of selected MPP+ fragmentations m/z 170→127, 170→128, and 170→154 obtained by averaging the MPP+ chromatographic peak (i.e. 8.1–8.3 min retention time). (See colour version of this figure online at www.informahealthcare.com/txm)

Scheme 1.

Hypothetical scheme to account for the m/z 154, 128, and 127 fragments originating from the MPP+ m/z 170 parent ion during electro-spray ionization. MPP+ is an even-electron (EE+) species that can release a neutral molecule of methane to yield m/z 154. Electron loss (or potentially gain) initiates a cascade of retro-Diels Alder type electron rearrangements culminating in pyridine ring cleavage and loss of methyl isocyanide and a hydrogen atom (m/z 128) or loss of methyl isocyanide and hydrogen gas (m/z 127) (McLafferty and Turecek 1993).

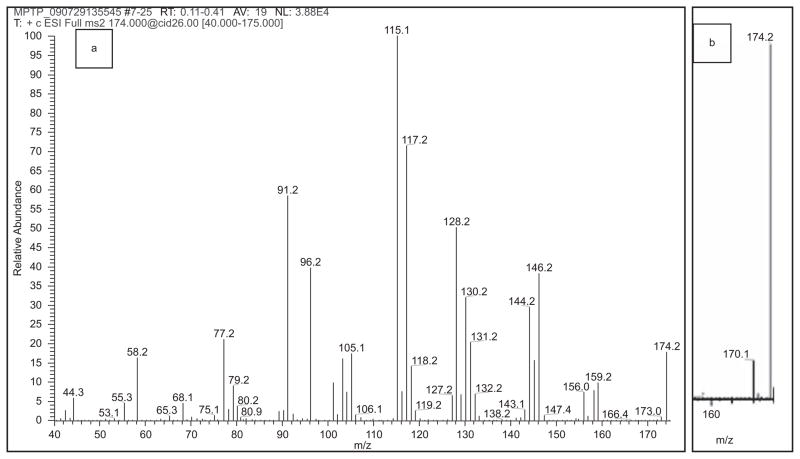

The MPP+ parental compound MPTP differs from MPP+ in that its free base form is not a cationic quaternary amine, but rather a cyclic tertiary amine requiring proton uptake for +1 charge. In Figure 5 the chromatography of MPTP is compared to that of MPP+ based on SRM for fragmentations m/z 174→44, 174→77, 174→91, and 174→115. Figure 6a shows the product ion spectrum of the MPTP + H+ m/z 174 ion, while Figure 6b shows a critical portion of the full scan spectrum of MPTP, illustrating a small amount of in-source generation of m/z 170, presumably MPTP oxidized to MPP+. Whereas the MPP+ spectrum of Figure 4 has a relatively simple pattern of fragmentations, MPTP (Figure 6a) offered an unusual pattern involving numerous paired peaks differing by 2 amu, specifically, m/z 42/44, 77/79, 103/105, 115/117, 128/130, 144/146, 156/158, and 172/174. This and the in-source generation of m/z 170 suggest that many of the fragments of MPTP arise from instrumental generation of both MPDP+ and MPP+.

Figure 5.

MPP+ and MPTP chromatography comparison. Shown are combined TIC chromatograms for MPP+ (top) derived as in Figure 2, and MPTP [bottom], the latter derived by combining individual SRM area counts for m/z 174→44, 174→77, 174→91 and 174→115 for MPTP. MPP+ was at 20 ng/ml and MPTP was at 100 ng/ml. (See colour version of this figure online at www.informahealthcare.com/txm)

Figure 6.

MPTP mass spectrometry. (a) Full scan product ion mass spectrum of m/z 174 ion obtained during direct infusion of 10 μg/mL MPTP. The CID (collision induced dissociation) energy was 26 V; a value of 5 V gives predominantly m/z 174.2, whereas a value of 52 V gives predominantly m/z 44.2. (b) Full scan mass spectrum of the m/z 155–175 region, indicating that introduction into the electrospray source caused a small amount of dehydrogenation to MPP+. (See colour version of this figure online at www.informahealthcare.com/txm)

Table 3 gives evidence for such a hypothesis, starting with the principal MPP+ fragments in column A as a beginning point and sorting MPTP fragments as belonging to MPTP, MPDP+, or MPP+. Put conversely, many of the ions specific to MPP+ could also be seen to arise from MPTP, and the distribution of ions in columns B and C indicate which ions may have arisen from +2 (=MPDP+) and +4 (=MPTP) variants of MPP+. The interpretations in Table 3 enabled the generation of Scheme 2 for the rearrangements leading to the ions utilized in MPTP detection, specifically ions m/z 44, 77, 91, and 115. Note that the boxed area essentially includes the mechanism of MPTP oxidation as observed from MAO-B enzyme activity in vivo (Salach et al. 1984).

Table 3.

Interpretation of MPTP mass spectrometry, assuming spontaneous generation of-H2 (to MPDP+) and-2H2 (to MPP+) analogs during fragmentation. MPP+ fragments in column A were listed as a starting point, and m/z values were seen in the MPTP product ion spectrum. Plus 2 (column B) and plus 4 (column C) analogs of MPP+ are also listed with projected hypothetical fragments arising from simple +2 or +4 calculations, and all of the m/z values listed were observed in MPTP fragmentation. Some unseen fragments are also shown in parentheses for continuity, and some additional fragments differing due to migration of a single proton are listed in columns labeled A−1, B−1, C−1, and C+1.

| A−1 | A

|

B–1 or A+1 | B

|

C–1 or B+1 | C

|

C+1 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPP+ C12 H12 N1 | MPDP+ C12 H14 N1 | MPTP+H C12 H16 N1 | |||||

| 170 | 172 | 174 | Molecular ion | ||||

| (154) | 156 | 157 | 158 | 159 | Loss of CH4 | ||

| 144 | 145 | 146 | (147) | Loss of HC=CH or analog | |||

| 128 | 130 | 131 | (132) | Loss of CH3NHCH3 or analog | |||

| 115 | 117 | 118 | (119) | C6H5C=C=CH2+ or analog | |||

| 103 | (104) | 105 | 106 | C6H5C=CH2+ or analog | |||

| 91 | (92) | (94) | 96 | Loss of C6H6 ring or analog | |||

| 77 | 79 | Pyridinyl ring C5H3N+ or analog | |||||

| 68 | CH3NH(CH)C=CH+ or analog | ||||||

| 58 | CH3NHCH2CH2+ or analog | ||||||

| (51) | (53) | 55 | CH3NHC=CH+ or analog | ||||

| 42 | 44 | CH3NHCH2+ or analog |

Scheme 2.

Hypothetical scheme to account for the m/z 44, 77, 91, and 115 fragments originating from the MPTP +H+ m/z 174 parent ion during electrospray ionization. The scheme proposes spontaneous generation of both MPDP+ and MPP+ species during fragmentation, and the boxed section is essentially the two step oxidation process observed in vivo from monoamine oxidases. The scheme is supported by the observation of +2 analogs of m/z 77 and 115 that would have to arise from the MPDP+ intermediate (McLafferty and Turecek 1993).

The LC-MS/MS method gave the following validation statistics. Calculation of lower limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ) was performed by the method of analyzing repeated blanks for any background signal present at the expected retention time of the compounds, determining the standard deviation of the values (n = 7) and multiplying by 3.3× or 10×, respectively, according to established methods (Swartz and Krull 1997; Miller and Miller 2000). The LOD for MPP+ was 0.023 ppb and LOQ was 0.069 ppb, and blank extracted tissue samples calculated at 0.009 ppb, well below the LOQ. Calibrators gave acceptable responses in the 0.5–100 ppb range, and calibrator areas were fit to linear or quadratic equations with an average coefficient of determination (r2) of 0.9993 ± 0.00077. MPTP did not perform as sensitively; i.e. the LOD for MPTP calculated as 0.36 ppb, with an LOQ of 6.74 ppb. Calibrators gave curvilinear response in the 0.5–100 ppb range and were fit to quadratic curves with typical coefficients of determination of 0.9946; note that the dynamic range of MPTP calibrators could easily be constrained to those between 0.5–20 ppb with the intention of imposing a linear relationship. The higher calculated LOQ of MPTP may explain difficulties in its detection in tissue analytical samples post-MPTP inoculation (data not shown).

Specificity of the determination of MPP+ was assured by examining qualifier product ion (m/z 127)/(m/z 128) and (m/z 154)/(128) area ratios. Qualification as the expected structure was considered confirmed when fragment area ratios matched those of standards ± 40%, similar to MS/MS criteria recommended by the Association of Official Racing Chemists for MS/MS techniques (summarized by Van Eenoo and Delbeke 2004). Table 4 lists such area ratios across the entire examined concentration range, indicating their relative uniformity and good correspondence between spike and sample ratios and those measured in standards. For example, the spike (m/z 127/m/z 128) average value of 0.739 fits easily into the calculated acceptable range of 0.39–0.90, as does that for the sample average value of 0.721.

Table 4.

Area counts for a typical MPP+ standard curve, showing concentration (ppb), the area counts and the monitored area ratios (m/z 127/m/z 128) and (m/z 154/m/z 128). Included are the average ratios and standard deviations, plus the acceptable ranges for correctly identified samples according to forensically acceptable AORC criteria. Average values for spike and sample results are also listed.

| Conc., ppb | m/z 170 products

|

area ratios

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z 127 area | m/z 128 area | m/z 154 area | (m/z 127/m/z 128) | (m/z 154/m/z 128) | |

| 0.5 | 20,063 | 32,226 | 13,448 | 0.623 | 0.417 |

| 1 | 29,327 | 35,136 | 14,845 | 0.835 | 0.422 |

| 2 | 42,821 | 73,941 | 20,990 | 0.579 | 0.284 |

| 5 | 115,333 | 193,520 | 68,835 | 0.596 | 0.356 |

| 10 | 226,119 | 357,167 | 145,175 | 0.633 | 0.406 |

| 20 | 479,537 | 746,763 | 289,211 | 0.642 | 0.387 |

| 100 | 2,069,283 | 3,472,955 | 1,357,258 | 0.596 | 0.391 |

| 1000 | 18,765,473 | 28,781,742 | 10,839,783 | 0.652 | 0.377 |

| Calibrator | Average | 0.644 | 0.380 | ||

| SD | 0.081 | 0.045 | |||

| Range | 0.39–0.90 | 0.23–0.53 | |||

| Spikes (n = 5) (10 ppb) | Average | 0.739 | 0.331 | ||

| SD | 0.075 | 0.102 | |||

| Samples (n = 61) | Average | 0.721 | 0.367 | ||

| SD | 0.093 | 0.073 | |||

MPTP was similar with the exception that acquisitions took place under high collision energies (40–52 V) for maximum sensitivity for this compound, principally arising from the m/z 174→44 fragmentation. Other fragmentations under such conditions are relatively suppressed in area counts. Nevertheless, specificity for this compound could still be assured by resorting to fragment area ratios: (1) (m/z 77)/(m/z 44) = 0.0263 ± 0.0012; (2) (m/z 91)/(m/z 44) = 0.0024 ± 0.00020; and (3) (m/z 115)/(m/z 44) = 0.0068 ± 0.00052 (n = 10).

The technique of LC-MS/MS enabled measurement of detectable levels of MPP+ in the NA and ST of MPTP treated mice. Concentrations (pg/μg protein) of MPP+ in the NA increased to ~ 3-times that of the ST in the first h and remained higher for up to 8 h (Figure 7). Measurements of MPTP in tissues using LC-MS garnered inconclusive results in that both the NA and ST had essentially no detectable MPTP (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Time of striatal and nucleus accumbens MPP+ following subcutaneous MPTP injection. Striatal MPP+ (one-way ANOVA on Ranks) concentrations were measured in the striatum to be (pg MPP+/μg protein): Control = not detectable, 1 h = 4.74 ± 0.84, 2 h = 2.60 ± 0.38, 4 h = 1.59 ± 0.15, and 8 h = not detectable. Nucleus accumbens MPP+ (one-way ANOVA) was measured to be (pg MPP+/μg protein): Control = not detectable, 1 h = 17.15 ± 1.99, 2 h = 12.44 ± 1.05, 4 h = 10.85 ± 1.00, and 8 h = 4.31 ± 1.31. Closed markers indicate a statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) as compared to the ‘0 hour-control’.

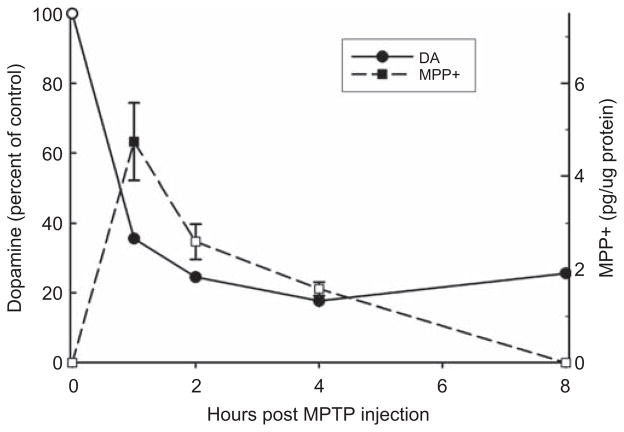

By using the same prepared samples of ST tissue, HPLC was able to detect DA over the 8 h time course (Figure 8). One hour following MPTP injection, DA decreased by over 60% as compared to control, and DA decline progressed to between 20–30% of control at 4 and 8 h post-MPTP administration. The initial large loss of striatal DA correlated with the highest levels of MPP+ and the levels of MPP+ decreased in the ST such that by 8 h there was no detectable MPP+.

Figure 8.

Time course correlation of striatal dopamine (DA) and MPP+ following subcutaneous MPTP injection. Striatal DA concentrations were measured to be (ng DA/mg protein): Control = 44.7 ± 10.3, 1 h = 15.9 ± 4.7, 2 h = 13.5 ± 3.4, 4 h = 7.9 ± 32.7, and 8 h = 11.5 ± 4.5. ■Indicates a statistically significant difference as compared to the control level of MPP+ (one-way ANOVA on Ranks). ● Indicates a statistically significant difference as compared to the control level of DA based upon raw data values (one-way ANOVA). ‘0 hour-control’ mice were injected with saline and then sacrificed at the 1-h time point.

Discussion

LC-MS/MS provides sensitivity for MPP+ analysis because it provides a clean baseline with little noise owing to SRM focus on mass m/z 170; it also provides specificity through chromatography to a specific retention time on a hydrophobic HPLC column. Specificity is enhanced relevant to simpler MS techniques such as selected ion monitoring (SIM) or full scan analysis because the SRM method utilizes MPP+-specific molecular fragmentations.

Overall, mass spectrometric detection of MPP+ succeeded because (1) the compound is inherently charged and relatively stable; (2) mobile phase conditions were matched to the tissue buffer composition; (3) this match enabled direct application of existing tissue buffers as HPLC sample dissolution solvent; (4) the mobile phase in turn facilitated electrospray in the ESI source with adequate solvent removal via nitrogen nebulization and acceleration of desolvated components into the triple stage quadrupole MS detector; (5) SRM was set up with adjustment of the first quadrupole to select mass m/z 170 exclusively; and (6) analysis was carried out by allowing the m/z 170 parent ion to undergo argon collisionally-induced dissociation in the second stage hexapole, followed by mass analysis of resulting fragments in the third quadrupole.

Specific MPP+ fragment ions were chosen as m/z 127, 128, and 154; quantitation was based on the sum of the peak areas for m/z 170→127, 170→128, and 170→154 fragmentations, with the ratio of qualifier product ions (m/z 127)/(m/z 128) and (m/z 154)/(m/z 128) used for assurance of identity. Qualification as the expected structure was considered confirmed when fragment area ratios matched those of the standard ± 40%, similar to MS/MS criteria recommended by the Association of Official Racing Chemists (summarized by Van Eenoo and Delbeke 2004) for MS/MS techniques. These three ions arise specifically as: m/z 128, loss of CH3N=CH; m/z 127, loss of H. from m/z 128; and m/z 154, simultaneous loss of H and CH3 from m/z 170, presumably as a neutral methane molecule; the latter loss may be specific to methylated quaternary amines, since the related compound paraquat (1,1′-dimethyl-4,4′-dipyridinium) shows a similar loss under ESI-MS conditions (Lee et al. 2004). Fragment identifications are tentative due to their unusual individual natures, but in any case agree with spectra generated by Boismenu et al. (1996) under similar conditions.

There were interesting findings in the mass spectometric study of these compounds. Guo (2005) has made the point that small quaternary amines such as MPP+ might be most dependably and sensitively analyzed by hydrophilic interaction chromatography coupled to ESI+-MS; in this regard, the present study achieved sufficient sensitivity using more routine reverse phase chromatography conditions. The product ion spectrum described here for MPP+ m/z 170 agrees with those published by Zhang et al. (2008) and Boismenu et al. (1996), both run by ESI+-MS. This agreement extends particularly to the major ions m/z 170, 154, 128, and 127, but also to the majority of minor peaks identified by these researchers (m/z 140, 115, 103, 92, 77, and 65). The more limited mass spectrum of Hows et al. (2004) agrees at least with the major ions. Both the Zhang and Hows research groups attribute the principal ion at m/z 128 to a quinolinium structure attained by an undescribed mechanism. While it is true that some low molecular weight nitrogenous compounds such as amino acids may form heterocyclic rings under conditions of pyrolysis (Sharma et al. 2003) and as a general principle many unimolecular processes can lead to reactive intermediates capable of rearrangements (Gruetzmacher 1992), the simple mechanism described here (Scheme 1) is a superior argument because it accounts for generation of both m/z 128 and 127 by loss of either a hydrogen atom or of an H2 molecule, respectively. Zhang et al. (2008) in contrast felt obliged to replace the N atom in quinoline with a carbon to explain m/z 127 by an inexplicable mechanism. The C2H4N or C2H5N losses of Scheme 1 are also supported by fragments obtained during electron impact mass fragmentation of the analogous 1-methyl-4-phenylpiperidines (Mabic and Castagnoli Jr. 1998).

MPTP is generally a more difficult compound with regards to consistency in its mass spectrum, possibly owing to subtle inherent reactivity. Mabic and Castagnoli, Jr. (1998) published a relatively straightforward electron impact mass spectrum for MPTP with m/z 173, 172, 144, 129, 115, 96, and 91, the spectrum of which is included in the Wiley Mass Spectral database (Palisade Mass Spectrometry, Newfield, NY). An electron impact mass spectrum obtained by direct insertion probe, on the other hand, showed an intense m/z 339 plus m/z 324, 296, 261, 218, 170, and 148 (from the AIST Integrated Spectral Database System of Organic Compounds of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Japan); this is clearly a dimer arising from intermolecular reactivity. Interestingly, the dimer is capable of generating an m/z 170 fragment, the size of an MPP+ structure. Ishii et al. (2002) carried out surface ionization mass spectrometry of MPTP yielding an intense m/z 170. The result was similar to those from three analogous tetrahydropyridines, obliging them to posit aromatization via an otherwise undescribed M-3 mechanism.

The present study of MPTP reflects aspects of these varied mass spectrometric findings. Figure 6b indicates some capacity for this compound to generate an m/z 170 fragment spontaneously in the electrospray ionization source before analysis by the first quadrupole; this m/z 170 fragment is presumably MPP+. The facility of this generation led to the conclusion that the dihydropyridine structure MPDP+ is a necessary intermediate, as shown in Scheme 2. This was a fortunate speculation even in the absence of support from an m/z 172 peak in Figure 6b, since it agreed with the well known reactivity of the MPDP+ intermediate (Gessner et al. 1984; 1985), particularly under oxidizing conditions, and since it helped explain the more complex m/z 174 product ion mass spectrum of MPTP in Figure 6a. Specifically, the observation of many ions differing by 2 amu values encouraged assignment of MPTP fragments as belonging to either MPTP+H+, MPDP+, or even MPP+ itself. Table 3 sorts out the respective ions and their likely origins as belonging to MPTP+H+ (Column C: m/z 174, 159, 96, 58), to MPDP+ (Column B: m/z 172, 157, 146, 117, 105, 79), or to MPP+ (Column A: m/z 144, 128, 115, 103, 91, 77, 68). In support of this argument, the peaks assigned as arising from an in situ generated MPP+ correspond fairly well to those observed for MPP+ examined directly (Figure 4, top panel), in some cases (m/z 144, 92) requiring adjustment by shift of a proton. The facile conversion of MPTP to its MPDP+ and MPP+ products during argon kinetic bombardment offer an additional dimension that may rationalize the lower detectable levels of MPTP in our system, given distribution of products across many more fragments in MPTP than in MPP+.

All tissue samples were analyzed for MPTP, yet this compound was only detected at the 1 h time point when values were above the LOD (0.36 ppb) but below the LOQ (6.74 ppb). There is one explanation for the difference in sensitivity between MPP+ and MPTP that may have a bearing on MPTP detectability. Cox et al. (2003) have indicated that tertiary amine functionalities on polystyrene polymers have several modes of ionization available (M−H+, M+H+, M.+) in contrast to analogous quaternary amines which simply have M+ when studied by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. This principle may account for the superior sensitivity of the system described here to MPP+ (a quaternary amine) in contrast to that of MPTP (a tertiary amine). In short, dependence on acid equilibration hampered by competing side reactions may limit detectability in the ESI source. The low levels and detectability of MPTP only at early time points are in agreement with the findings of other investigators (Hammock et al. 1989; Giovanni et al. 1991; Giuseppe et al. 2003; Ogunrombi et al. 2007). In fact, only one other investigator was able to measure MPTP after 30 min (Ogunrombi et al. 2007), and reported peak concentrations of MPTP occurred at 10 min following injection, falling to nearly undetectable levels at 30 min. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the inability to measure MPTP at later time points in the present study is due to its rapid metabolism.

Publications on measurement of MPP+ in brain tissue by LC-MS/MS exist, but these use buffers not suitably optimized for simultaneous measurement of MPP+ and neurotransmitter amines (and their less stable metabolites). For example, Hows et al. (2004) used 0.4 M perchlorate containing sodium metabisulfite (0.1%), EDTA (0.01%), and cysteine (0.1%). Zhang et al. (2008) homogenized 100 mg of brain tissue in 1 mL of 0.4 M perchloric acid, whereas Winnik et al. (2009) homogenized 10–15 mg of brain tissue in 150 μL of 12% acetic acid. Whereas these procedures work well for analysis of MPP+, they are not optimal for concurrent neurotransmitter amine analysis.

In the present study MPP+ was successfully quantified in the NA and ST of mice given a single dose of MPTP. It is not clear why levels of MPP+ in the NA are higher than in the ST. Since MPTP is biotransformed to MPP+ by MAO-B, which is in both glial and neuronal cells in the brain (Salach et al. 1984; Takada et al. 1990; Nakamura et al. 1995), it is possible that there is more MAO-B present in the NA than in the ST, or that MAO-B is more efficient in the NA. A study by Takada et al. (1990) mapping neuronal MAO-B staining in mice qualitatively showed higher neuronal MAO-B staining in the ST as opposed to the NA, which seemingly contradicts the findings of this study. However, due to the greater numbers of cells, glial MAO-B is believed to be more essential to MPTP toxicity than neuronal MAO-B. Further study must be conducted to determine the mechanism whereby the NA, while seemingly more resistant to MPTP toxicity, actually contains higher levels of MPP+ following MPTP injection.

The overall trends in total MPP+ concentrations were similar to those reported by Vaglini and Fascetti (1996), who measured striatal MPP+ concentration in mice given a single dose of 30 mg/kg MPTP. In their study only a small amount of MPP+ was still detectable 6 h after MPTP administration. A similar trend of MPP+ concentration in ST was also reported by Zhang et al. (2008), who used an even higher dose of MPTP at 40 mg/kg in mice. In general, MPP+ has a short half-life (4 h in mice) and, depending on the region of brain, only negligible amounts if any remain 8 h post-MPTP administration (Vaglini and Fascetti 1996).

The results of the present study also contrast with those of Fuller et al. (1989), who found that MPTP given s.c. to mice at 30 mg/kg resulted in detectable levels (5 μg/gm tissue) of both MPTP and MPP+ in brain tissue, whereas oral administration resulted in nearly undetectable levels of either compound in brain as compared with peripheral tissues. The half-life of MPP+ varied between 3 h (for whole brain) and 20 h (for lung and kidney). The differences in MPTP and MPP+ detectability are likely accounted for by the homogenization of entire brain samples, rather than examination of discrete tissue types, as well as the rapid clearance of MPTP from the brain.

In conclusion an LC/MS method for analysis of MPTP and MPP+ in brain tissue was developed and employed to correlate levels of toxic MPP+ metabolite with loss of DA measured via HPLC coupled with electrochemical detection. The LC/MS method utilized selected reaction monitoring (SRM) of MPP+ m/z 170→127, 170→128, and 170→154 fragmentations for quantitation and (m/z 127)/(m/z 128) and (m/z 154)/(m/z 128) fragment area ratios for identity confirmation. The advantage of this approach is that the tissue buffer used in this procedure allowed concurrent measurement of striatal DA, thus enabling direct correlation between accumulation of tissue MPP+ and depletion of DA concentrations in discrete regions of the brain.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Behrouz B, Drolet RE, Zayed ZA, Lookingland KJ, Goudreau JL. Unique response to mitochondrial Complex I inhibition in tuberoinfundibular dopamine neurons may impart resistance to toxic insult. Neuroscience. 2007;147:592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boismenu D, Mamer O, Ste-Marie L, Vachon L, Montgomery J. In vivo hydroxylation of the neurotoxin, 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium, and the effect of monoamine oxidase inhibitors: electrospray-MS analysis of intrastriatal microdialyzates. J Mass Spectrom. 1996;31:1101–1108. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199610)31:10<1101::AID-JMS397>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox FJ, Johnston MV, Dasgupta A. Characterization and relative ionization efficiencies of end-functionalized polystyrenes by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:648–657. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GC, Williams AC, Markey SP, Ebert MH, Caine ED, Reichert CM, Kopin IJ. Chronic Parkinsonism secondary to intravenous injection of meperidine analogues. Psychiatry Res. 1979;1:249–254. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Monte DA, Langston JW. MPTP and analogs. In: Spencer PS, Schaumburg HS, editors. Experimental and clinical neurology. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 812–818. [Google Scholar]

- Filipov NM, Norwood AB, Sistrunk SC. Strain-specific sensitivity to MPTP of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice is age dependent. Neuroreport. 2009;20:713–717. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32832aa95b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller RW, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Perry KW. Tissue concentrations of MPTP and MPP+ in relation to catecholamine depletion after the oral or subcutaneous administration of MPTP to mice. Life Sci. 1989;45:2077–2083. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner W, Brossi A, Shen R, Abell CW. Further insight into the mode of action of the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) FEBS Lett. 1985;183:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner W, Brossi A, Shen R, Fritz RR, Abell CW. Conversion of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and its 5-methyl analog into pyridinium salts. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 1984;67:2029–2272. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanni A, Sieber B, Heikkila RE, Sonsalla PK. Correlation between the neostriatal content of the 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium species and dopaminergic neurotoxicity following 1-methly-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrathydropyridine administration to several strains of mice. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 1991;257:691–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuseppe B, Busceti CL, Pontarelli F, Biagioni F, Fornai F, Paparelli A, Bruno V, Ruggieri S, Nicoletti F. Protective role of group-II metabotropic glutamate receptors against nigrostriatal degeneration induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruetzmacher HF. Unimolecular reaction mechanisms: the role of reactive intermediates. Int J Mass Spectrom Ion Processes. 1992;118–119:825–855. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. Analysis of quaternary amine compounds by hydrophilic interaction chromatography/mass spectrometry (HILIC/MS) J Liq Chromatogr R T. 2005;28:497–512. [Google Scholar]

- Hammock BD, Beale AM, Work T, Gee SJ, Gunther R, Higgins RJ, Shinka T, Castagnoli N., Jr A sheep model for MPTP induced Parkinson-like symptoms. Life Sci. 1989;45:1601–1608. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hows ME, Ashmeade TE, Billinton A, Perren MJ, Austin AA, Virley DJ, Organ AJ, Shah AJ. High-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry assay for the determination of 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium (MPP+) in brain tissue homogenates. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;137:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Watanabe-Suzuki K, Seno H, Suzuki O, Katsumata Y. Application of gas chromatography-surface ionization organic mass spectrometry to forensic toxicology. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;776:3–14. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Lewis V, Smeyne RJ. From man to mouse: The MPTP model of Parkinson disease. In: LeDoux M, editor. Animal models of movement disorders. New York: Elsevier academic press; 2005. pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Langston JW, Ballard P, Tetrud JW, Irwin I. Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science. 1983;219:979–980. doi: 10.1126/science.6823561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee XP, Kumazawa T, Fujishiro M, Hasegawa C, Arinobu T, Seno H, Ishii A, Sato K. Determination of paraquat and diquat in human body fluids by high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2004;39:1147–1152. doi: 10.1002/jms.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley SE, Gunnet JW, Lookingland KJ, Moore KE. 3, 4-Dihydroxypheny-lacetic acid concentrations in the intermediate lobe and neural lobe of the posterior pituitary gland as an index of tuberohypophysial dopaminergic neuronal activity. Brain Res. 1990;506:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabic S, Castagnoli N., Jr Studies on the electron-impact-induced fragmentation of 1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridines. J Mass Spectrom Soc Jpn. 1998;46:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty FW, Turecek F. Interpretation of mass spectra. 4. Sausalito, CA: University Science Books; 1993. pp. 69–70.pp. 349 [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Miller JN. Statistics and chemometrics for analytical chemistry. 4. New York: Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Akiguchi I, Kimura J. Topographic distributions of monoamine oxidase-B-containing neurons in the mouse striatum. Neurosci Lett. 1995;184:29–31. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)11160-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunrombi MO, Malan SF, Blanche GT, Castagnoli K, Castagnoli N, Bergh JJ, Petzer JP. Neurotoxicity studies with the monamine oxidase B substrate 1-methyl-3-phenyl-3-pyrroline. Life Sci. 2007;81:458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits M. Isolated removal of hypothalamic or other brain nuclei of the rat. Brain Res. 1973;59:449–450. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90290-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits M. Microdissection of brain areas by the punch technique. In: Ceullo A, editor. Brain microdissection techniques. New York: Wiley Interscience; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Przedborski S, Jackson-Lewis V, Naini AB, Jakowec M, Petzinger G, Miller R, Akram M. The parkinsonian toxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP): a technical review of its utility and safety. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1265–1274. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salach JI, Singer TP, Castagnoli N, Jr, Trevor A. Oxidation of the neurotoxic amine 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) by monoamine oxidases A and B and suicide inactivation of the enzymes by MPTP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;125:831–835. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)90614-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma RK, Chan WG, Seeman JI, Hajaligol MR. Formation of low molecular weight heterocycles and polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) in the pyrolysis of alpha-amino acids. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2003;66:97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Swartz ME, Krull IS. Analytical method development and validation. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1997. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Takada M, Li ZK, Hattoir T. Astroglial ablation prevents MPTP-induced nigrostriatal neuronal death. Brain Res. 1990;509:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglini F, Fascetti F. Striatal MPP+ levels do not necessarily correlate with striatal dopamine levels after MPTP treatment in mice. Neurodegeneration. 1996;5:129–136. doi: 10.1006/neur.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eenoo P, Delbeke FT. Criteria in chromatography and mass spectrometry- a comparison between regulations in the field of residue and doping analysis. Chromatographia. 2004;59 (Suppl 1):S39–S44. [Google Scholar]

- Winnik B, Barr DB, Thiruchelvam M, Montesanno MA, Richfield EK, Buckley B. Quantification of paraquat, MPTP, and MPP+ in brain tissue using microwave-assisted solvent extraction (MASE) and high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;395:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2929-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang MY, Kagan N, Sung ML, Zaleska MM, Monaghan M. Sensitive and selective liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry methods for quantitative analysis of 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium (MPP+) in mouse striatal tissue. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2008;874:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2008.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]