Abstract

Disability is pervasive in schizophrenia and is refractory to current medication treatments. Inability to function in everyday settings is responsible for the huge indirect costs of schizophrenia, which may be as much as three times larger than direct treatment costs for psychotic symptoms. Treatments for disability are therefore urgently needed. In order to effectively treat disability, its causes must be isolated and targeted; it seems likely that there are multiple causes with modest overlap. In this paper, we review the evidence regarding the prediction of everyday disability in schizophrenia. We suggest that cognition, deficits in functional capacity, certain clinical symptoms, and various environmental and societal factors are implicated. Further, we suggest that health status variables, recently recognized as pervasive in severe mental illness, may also contribute to disability in a manner independent from these other better-studied causes. We suggest that health status be considered in the overall prediction of real-world functioning and that interventions aimed at disability reduction targeting health status may be needed, in addition to cognitive enhancement, skills training, and public advocacy for better services.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, disability, cognition, functional capacity, intrinsic motivation, environmental factors, health status

Schizophrenia is one of the world’s most disabling illnesses 1, with patients experiencing deficits in a variety of everyday functional domains 2. Most of these impairments are homogeneous across different countries and cultures, with functional abilities appearing to be equivalently impaired in patients who are demographically similar across Western and developing countries 3,4.

There are several aspects of the ability to perform cognitive and functional skills that are impaired in people with schizophrenia, including cognitive functioning indexed by performance on neuropsychological tests 5 and performance on targeted assessments of functional skills 6. There are also a variety of environmental and cultural influences that impact on everyday functioning, in both positive and adverse directions. These include disability compensation, opportunities, residential support, and various elements of attitudes and stigma 7,8.

Illness symptoms, including depression, negative symptoms, psychosis, and awareness of illness, also impact on functioning 9. Interestingly, these influences do not appear to impact on functioning through some type of influences on ability variables, but rather seem to have a direct impact on functioning that does not reduce the abilities that underlie function.

Finally, there are a large array of factors that impact everyday functioning in people without serious mental illness that have received little research attention despite the fact that they are quite prevalent in people with severe mental illness. These factors include metabolic disorders, heart disease, pulmonary conditions, and their everyday functional sequelae. While the presence of these conditions in schizophrenia is well documented 10, there have been few attempts to determine the extent to which these factors impact on everyday functioning and where their influence would occur.

In this paper, we review the evidence that allows for the quantification of the influences of various factors on real-world functioning in people with schizophrenia. We base our review on published literature that examines the correlations between various potential predictive factors and everyday outcomes. Furthermore, we propose several additional areas of investigation that might add to the understanding of the previously unaccounted for variance in disability in everyday functioning. We also examine whether it is possible that the above factors, if suitably addressed, could reduce the occurrence of everyday disability in schizophrenia.

FACTORS AFFECTING EVERYDAY FUNCTIONING IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

Despite the striking nature of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses, the most costly problem in these conditions is impairments in everyday functioning. These impairments lead to a total cost that is substantially greater than that associated with the treatment of psychosis by both medications and psychiatric admissions. Impaired everyday functioning in people with schizophrenia spans the major functional domains of independence in residence, productive activities, and social functioning 11. Achievement of typical milestones is less common than in the healthy population, and many functional skills (i.e., social, vocational, and independent living) themselves are performed at lower levels.

Impaired everyday functioning is a complex phenomenon, because there are many factors that contribute to adequate outcomes. They include the ability to perform functional skills, the motivation to perform the skills, recognition of the situations where skilled performance is likely to be successful, as well as factors that interfere with ability, motivation, and the situation recognition required to optimize skills performance. These interfering factors include symptoms, health status, and medication side effects. Further, there are environmental factors that directly and indirectly influence functioning in the real-world. Direct influences include lack of opportunities to achieve functional goals (e.g., living in a neighborhood where no one speaks your language; high unemployment rates) or legal restrictions (e.g., immigration status). Indirect environmental influences include disincentives, such as contingent relationships between disability compensation and health insurance, which then force people to decide between attempting to work and receiving treatment for their illness.

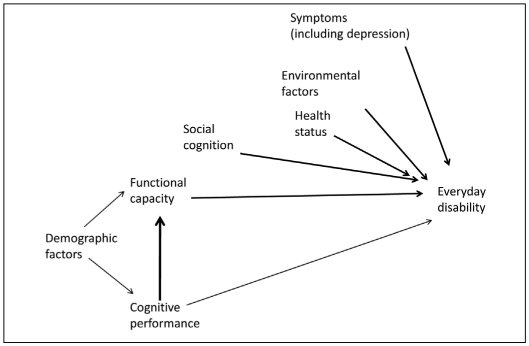

Figure 1 shows our model of the cascade to impairments in everyday functioning. The direct influences include functional capacity, social cognition, symptoms, environmental factors, and health status. Some of these variables have been investigated in much detail than others and many have never been examined in a systematic multivariate study that included all or even any other of the different potential predictors. Further, the influences of some factors on functional outcome, such as performance on neurocognitive tests, are found to be much stronger when other potentially mediating factors, such as functional capacity, are not considered. Similarly, many features of schizophrenia impact on everyday outcomes without influencing their performance-based precursors: cognition, functional capacity, and social cognition. Thus, our model is not the result of a meta-analysis, but rather a theoretical summary of the multiple potential influences on everyday functional disability identified across multiple research studies in people with schizophrenia.

Figure 1 Predictors of everyday disability in people with schizophrenia.

Cognitive functioning

In the past 20 years, there has been a burst of interest in the influence of cognitive deficits on everyday functioning. There have been many detailed reviews of this literature, so we will summarize the results of these reviews rather than cover old ground. Several of these findings are most important. These include the size of the correlation between cognitive deficits and everyday functional deficits, the specificity of this relationship across different cognitive ability domains, and which aspects of everyday functioning are more vs. less associated with cognitive impairments.

The findings across studies are generally consistent. Individual cognitive ability domains (e.g., learning, attention, executive functioning) have small to moderate correlations with global indices of everyday functioning 12. Further, composite scores manifest a generally moderate to large correlation with everyday functioning 5,12. When everyday functioning is rated by a clinician observer, the correlations with cognition are higher than when patients self-report their functioning 13. There is little evidence that there are specific cognitive deficits that predict specific functional deficits, possibly because “specific” cognitive deficits measured with neuropsychological tests are themselves quite multifactorial. More consistent evidence suggests that there are certain functional domains, social outcomes in particular, that are more strongly predicted by impairments other than cognition, including social cognition deficits 14 and negative symptoms 15.

Achieving independence in residential functioning seems most strongly correlated with cognitive intactness 11. Many people with schizophrenia are not seeking work, so the correlation between cognitive abilities and being employed can be reduced as a result. However, when patients are in structured programs and seeking employment, higher baseline levels of cognitive functioning and experiencing a cognitive benefit from remediation interventions both predict vocational success 16,17. Thus, the predictive nature of cognitive impairment in employment settings requires a desire on the part of patients to seek and sustain work.

Functional capacity

This is a rapidly developing concept and refers to the skills that underlie functional success. These skills include the ability to perform in the areas of residential functioning, work, and social skills 18. These abilities can be measured with tests that are administered in a manner similar to neuropsychological batteries, in a structured, quantified, and performance-based assessment that does not rely on self-report or the environmental opportunity or personal motivation to achieve functional milestones. Thus, it is possible to validly measure whether an individual could perform the skills necessary to work or live independently, even if the unemployment rate was high and the individual did not have the financial resources to afford a residence.

Several studies have found that indices of functional capacity are at least as strongly correlated with real-world functional outcomes as cognitive performance 9. Further, the correlation between performance-based neuropsychological assessments and the results of functional capacity assessments are quite high, averaging about r=.6 or more (and are found to be remarkably consistent across studies) 13. It has been hypothesized that cognitive impairments may exert their influence on everyday functioning through their relationship with functional capacity 19. Thus, cognitive deficits may reduce the ability to perform critical everyday functional acts, which in turn reduces the chances of successful everyday functioning.

In some studies, cognitive performance has been found to exert a minimal influence on real-world functioning when the influence of functional capacity was considered 9,19. However, given the high correlations between neuropsychological performance and functional capacity measures, some studies have found the opposite result: that neuropsychological performance accounts for all of the variance in everyday outcomes and functional capacity does not contribute 20. This is likely a function of statistical artifacts and more studies have found functional capacity to be most proximal to everyday functioning than the reverse.

Recently, a systematic large-scale study 6 was undertaken which aimed to determine which functional capacity measures were simultaneously most strongly related to both cognitive performance and everyday functioning. The results of this study suggested that several different functional capacity measures were strongly correlated with neuropsychological performance and related to everyday functioning and that both long and shorter forms had suitable psychometric properties as indexed through correlations with neuropsychological performance. Other studies have suggested that functional capacity measures have psychometric properties (test-retest reliability, variance, and practice effects) that are very similar to those seen for neuropsychological tests 21.

A critical set of validity data for functional capacity measures (and especially relevant to a world-wide audience) has been the findings that functional capacity measures show considerable similarity across studies performed in different countries. One of the arguments previously raised in support of neuropsychological functioning as a core feature of schizophrenia was the similarity in performance across the course of the illness and in different countries and cultures. Similar data have been produced for assessments of functional capacity. For example, patients in Sweden and New York City were found to be remarkably similar in their performance in functional capacity assessments, more similar than their performance on neuropsychological assessments 3. This similarity was found despite marked cultural differences in social support for people with schizophrenia, where it was close to three times more likely that a person with schizophrenia would be living independently in Sweden than in New York because of local social support factors.

In a study completed in China 4, it was found that functional capacity measures were quite sensitive to schizophrenia compared to healthy people, across a wide educational range spanning from 1 to 20 years. There was a substantial education effect that did not interact with illness, suggesting that the lives of more educated people are more complex and require more functional skills. That said, college educated people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were found to be performing similarly to healthy people who completed only middle school, suggesting considerable compromise associated with severe mental illness compared to healthy people. The effect sizes of this difference were similar to previous studies completed in the US.

Social cognition

As noted above, social cognition may be more strongly related to real-world social outcomes than neuropsychological performance 22. Social cognition refers, in general, to domains of ability that are cognitive, but directly linked to the skills required for social functioning, such as interpersonal perception and interactions. Domains of social cognition include emotion recognition, in both visual and auditory modalities, inference of other’s impressions of one’s self, judgment of intentions, and other related domains 23. Several reviews 24,25 and a recent meta-analysis 14 suggested that social cognition has consistent correlations with social functioning, including social milestones such as marriage or equivalent stable relationships and other social functions such as developing and maintaining friendly relationships.

One of the issues associated with social cognition, however, is that its definition and measurement is not as advanced as neuropsychological performance or even functional capacity. There is very little known about the psychometric properties of these measures, and many of them have been modified by individual research groups, leading to reduced comparability across studies related to more standardized neuropsychological assessment methods. Further, there has been very little research examining the contribution of social cognition to other functional domains such as employment, where social abilities are required to acquire and maintain many different jobs.

Symptoms, including depression

Psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia have been found to have remarkably little association with everyday functioning on a cross-sectional basis 5. While this seems counter-intuitive, patients can achieve sustained remission of their psychotic symptoms and still manifest considerable disability in multiple functional domains. Further, patients with persistent psychosis may be able to sustain independence in residential functioning. This situation may be partly due to the consistent finding that cognitive impairments are also not very strongly associated with the current presence of psychosis, a finding now replicated for functional capacity performance 9,19. Naturally, significant psychosis can be a major impediment to functioning, through its impacts on organization and judgment. However, this variable relationship between psychosis and outcome is the basis for a minimal cross-sectional correlation.

Other symptoms of schizophrenia do impact on everyday functioning. Negative symptoms, for instance, have an impact on a number of elements of everyday functioning. An interesting example is that of social amotivation and its impact on social functioning. Social amotivation is a classical deficit symptom, wherein the individual with this symptom is not interested in or actively avoids social contact. This form of amotivation is probably related to anhedonia and other reduced levels of social reinforcement obtained from interactions 26. It has been shown that social amotivation is more strongly related to social outcomes than either neuropsychological performance or social skills measured with a structured assessment 15. This is an interesting result because of its intervention implications. Social skills training, although widely delivered, might be futile in an individual whose lack of motivation to engage in social activities is the origin of social functioning deficits.

There has been an extensive debate about the relationship between negative symptoms and cognitive deficits 27. Rather than present the details of the debate, we will simply say that several different studies have shown that the contributions of cognitive impairments and negative symptoms to real-world functioning can be quantified separately and that there is some overlap between negative symptoms and cognition, although that overlap is small compared to the much more substantial correlations between each of these domains and everyday outcomes.

Depression has been a partially overlooked phenomenon in schizophrenia, with somewhat less research than deserved by its prevalence and impact on the morbidity and mortality of the illness. It is clear that many people with schizophrenia have symptoms of depression and may meet criteria for major depression concurrently to schizophrenia. Mood symptoms, even mild to moderate ones, have also been shown to exert a negative influence on everyday functioning 28. In contrast to common clinical impression, this adverse influence is not because of a negative impact of depression on neuropsychological and functional capacity. The influence seems more direct, and in three studies 9,19,29 with different patient populations we have shown that depression severity is minimally correlated with performance on ability measures, while being moderately correlated with impairments in everyday functioning. In fact, in a recent set of analyses we completed, we found that depression was the strongest predictor of everyday functioning deficits, having a larger (albeit not significantly) impact on everyday outcomes than neuropsychological performance or functional capacity 29. Thus, depression is an important symptom to consider when attempting to identify the causes of disability in schizophrenia.

Anhedonia

For well over 100 years, the idea that anhedonia was a central feature of schizophrenia has been advanced, starting with Kraepelin and Bleuler. Recent advances in the study of negative symptoms have made strides in understanding the complex nature of alterations in hedonic capacity in people with schizophrenia 30.

Many everyday acts are likely performed because of their intrinsically reinforcing consequences. Recent research has suggested that different types of anhedonia may be operative in schizophrenia and major depression. In major depression, the modal phenomenon seems to be the reduced ability to experience pleasure after engaging in potentially pleasant acts (consummatory anhedonia). In schizophrenia, there seems to be preserved ability to experience pleasure 26, while deficits in the ability to anticipate pleasureable consequences (anticipatory anhedonia) apparently predominate. In anticipatory anhedonia, the positive consequences of previously performed behavior are difficult to recall and the motivation to repeat these acts is therefore reduced. Interestingly, the little research done on depression and anhedonia in people with schizophrenia suggests an increased frequency of consummatory anhedonia in individuals with schizophrenia who have depressive symptoms. Thus, depressed people with schizophrenia may have qualitatively similar hedonic deficits compared to people with major depression 31. Individuals with persistent cognitive deficits such as those seen in schizophrenia may also be unable to volitionally retrieve their memories of previous positive experiences, leading to an increase in the inability to anticipate the pleasurable consequences of every action.

Recent research has suggested that individuals who endorse current reduced levels of intrinsic motivation on a questionnaire receive less benefit from active treatments aimed at cognitive enhancement than more motivated individuals 32,33. Reduced motivation to exert effort, while still attending the sessions, may lead to less engagement in the task, possibly leading to less brain activation and promotion of cognitive remediation benefits. Treatment of anhedonia and related reductions in motivation would seem to be a critical goal for improving the functioning of people with schizophrenia.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors are clearly related to real-world functioning. People with schizophrenia typically start out with less intrinsic advantages than the population as a whole and their illness leads to additional reductions in opportunities. Individuals with lifelong disability are financially challenged and may not have the resources to pay for an independent residence, which, combined with having more modest familial resources, can lead to a cascade of disadvantage.

Financial disadvantage has other potential adverse impacts. Not having adequate clothing can lead to disadvantages in seeking employment, and being impoverished can also lead to reduced nutritional possibilities and dietary choices that lead to adverse health outcomes. Living in poor neighborhoods also increases the risk of becoming a crime victim, whether it is property crimes or physical assaults, and people with schizophrenia are disproportionately likely to be a victim of a violent crime. Further, living in poor neighborhoods also increases the logistical challenge for getting to work if one can obtain a job.

Other environmental factors are operative as well. Disability compensation and health insurance are intrinsically linked for many patients in America. Thus, seeking employment may lead to suspension of insurance benefits, and individuals wishing to pursue recovery and to seek employment may paradoxically run the risk of having to suspend their medication treatment for their illness. Several studies have shown that the single best predictor of not being employed with schizophrenia in America is disability compensation, not because $400 a month is adequate to live on, but due to the intrinsic link between disability compensation and health insurance, which makes seeking a job without health insurance benefits implausible 7,8.

Difficult economic times also impact people with schizophrenia disproportionately, because of cut-backs in support services and because individuals who are more qualified than they are may be competing for the same jobs or residences when the economy contracts.

Health status

Patients with schizophrenia have higher rates of obesity and attendant medical comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension) than general population comparison samples 34,35. The current obesogenic environment has had a disproportionately large adverse impact on patients with schizophrenia. Several studies have pointed out how maladaptive lifestyles, including poor dietary choices, sedentary behavior, little physical exercise, and high rates of smoking, interact with treatment with antipsychotic medication to cause morbidity and mortality far exceeding population norms 36.

The propensity for schizophrenia to shorten lives is exacerbated by a relative lack of adequate medical screening, monitoring, and intervention for obesity and related metabolic comorbidities which spans health service delivery systems 37. This has led to the untenable situation that, despite treatment-related improvements in outcomes in the last decades with respect to psychiatric symptoms and quality of life, the mortality gap for patients with schizophrenia has not narrowed, but may actually be widening 38,39.

The impact of obesity and medical comorbidities on everyday disability in schizophrenia has received little attention and has never been quantified in the way that symptoms, cognition and functional capacity have been. In the psychiatrically healthy population, the magnitude of obesity, for example, correlates directly with the degree of disability in the performance of everyday activities (defined on a continuum between minor restriction and complete lack of ability to perform physical activities in relevant domains of life), with more severe degrees of obesity having a disproportionately larger negative impact 40.

Obesity-related impairments in mobility, flexibility, motor coordination, muscle mechanics, strength, and gait efficiency manifest themselves in difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs) in such diverse areas as dressing, bathing, walking several blocks, climbing stairs, doing housework, shopping, using public transportation, and the performance of any sort of vigorous activities 41. These impairments are not just due to physical size and related impairments in mobility but can result from baseline dysfunction (e.g., reduced mobility, flexibility, and persistence) or can also be associated with the occurrence of medical conditions caused or worsened by obesity. From a medical mechanistic perspective, atherosclerotic, hyperglycaemic and hypertensive end-organ damage may cause decline in cognitive, motoric, and gait abilities 40. Examples would include stroke, heart disease, vascular dementia, poor wound healing, and claudication among other conditions.

Obese people with schizophrenia may experience qualitatively similar impairment in physical functioning and resultant disability, compared to people without mental illness. Indirect supporting evidence comes from observations of impairments in quality of life, which obese people with schizophrenia report to experience even more as physical than psychological problems, resulting from perceived physical limitations 42,43. When these impairments are combined with the impairments associated with severe mental illness, there may be additive or even interactive influences.

Physical fitness

Patients with schizophrenia in America are much less physically fit than their mentally healthy counterparts. Their physical functional capacity, that is the ability to sustain physical activity, is markedly impaired 44,45. Causes include reduced heart and musculoskeletal strength, endurance, speed, and, perhaps, flexibility. Pulmonary disease, possibly from a high prevalence of tobacco use, is experienced as rate-limiting shortness of breath beyond a certain activity threshold. The presence of low levels of pulmonary disease, then, may have a negative impact on moderately strenuous physical activities, which become difficult to pursue 46. At the same time, anaerobic activities – those that require the greatest physical efforts – may be impossible to complete, which has multiple functional implications 47. On a continuum of worsening impairment in everyday activities, patients, for example, may elect not to grocery shop, come for appointments, engage in vocational activities or physical exercise prescription, interact with peers or socialize effectively, because the physical demands are unpleasantly high or simply unattainable.

The lack of physical activity paired with sedentary behavior and combined with adverse effects of various treatments leads to a cycle of worsening in self-efficacy, obesity, and disability. In mentally healthy people, improving physical fitness increases the ability to engage in meaningful everyday activities in social, vocational and independence domains, and reduces physical disability 48. We hypothesize that similar reductions in physical disability and improvements in ADLs can be expected in patients with schizophrenia. Because some of the above-mentioned clinical variables – for example, cognitive performance, motivation, or negative symptoms – may interfere with effective delivery of interventions to improve physical fitness in schizophrenia, special programs may be necessary.

Thus, physical limitations may exacerbate the functional deficits which can be produced by cognitive, symptomatic and functional capacity limitations. These physical limitations further reduce real-world performance in areas where the intrinsic limitations of schizophrenia are also operative. Thus, the cascade of influences on everyday functional impairment include deficits in cognition, functional capacity, the presence of specific symptoms and, newly introduced, the presence of multiple physical limitations associated with abnormalities in health status.

CONCLUSIONS

Disability in schizophrenia results from a cascade of multiple influences. These include ability variables such as cognition and functional capacity which have been studied in detail recently, as well as certain clinical symptoms. These variables have been quantified in several studies and reviews, leading to the conclusion that they account for about half of the measurable variance in everyday functioning. Environmental factors influence real-world functioning to a substantial extent, as evidenced by studies on the relationship between compensation and vocational and residential outcomes.

We suggest that there is an additional influence: the correlates of poor health status may be a predictor as well. This influence operates at several levels. There are direct impairments associated with size, mobility, and flexibility. Further, the underlying physiological impairments directly lead to deficits in everyday functioning, possibly through modification of cognitive abilities. In addition, stigma, a potent influence on outcomes in severe mental illness in any case, is likely amplified when obesity enters the equation.

The influence of health status on outcome in schizophrenia seems apparent, but has not been studied in the same detail as other determinants of outcome. We believe that future studies aimed at prevention and treatment of metabolic syndromes should also quantify the influence of these variables on everyday outcomes in critical functional domains.

References

- 1.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contributions of risk factors: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey PD, Raykov T, Twamley EM. Validating the measurement of real-world functional outcome: Phase I results of the VALERO study. Am J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121723. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey PD, Helldin L, Bowie CR. Performance-based measurement of functional disability in schizophrenia: a cross-national study in the United States and Sweden. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:821–827. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McIntosh BJ, Zhang XY, Kosten T. Performance based assessment of functional skills in severe mental illness: results of a large-scale study in China. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:1089–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green MF, Schooler NR, Kern RD. Evaluation of functionally-meaningful measures for clinical trials of cognition enhancement in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:400–407. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenheck RA, Frisman LK, Sindelar J. Disability compensation and work: a comparison of veterans with psychiatric and nonpsychiatric impairments. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:359–365. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A. Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(1):1–93. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung WW, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Functional implications of neuropsychological normality and symptom remission in older outpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14:479–488. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClure MM, Bowie CR, Patterson TL. Correlations of functional capacity and neuropsychological performance in older patients with schizophrenia: evidence for specificity of relationships? Schizophr Res. 2007;89:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leifker FR, Patterson TL, Heaton RK. Validating measures of real-world outcome: the results of the VALERO Expert Survey and RAND Panel. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:334–343. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fett AK, Viechtbauer W, Dominguez MD. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:573–588. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leifker FR, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. The determinants of everyday outcomes in schizophrenia: influences of cognitive impairment, clinical symptoms, and functional capacity. Schizophr Res. 2009;115:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–1802. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGurk SR, Mueser KT, Pascaris A. Cognitive training and supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: one-year results from a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:898–909. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey PD, Velligan DI, Bellack AS. Performance-based measures of functional skills: usefulness in clinical treatment studies. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1138–1148. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA. Prediction of real world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: a comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1116–1124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinrichs RW, Ammari N, Miles AA. Cognitive performance and functional competence as predictors of community independence in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:381–387. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leifker FR, Patterson TL, Bowie CR. Psychometric properties of performance-based measurements of functional capacity. Schizophr Res. 2010;119:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey PD, Penn DL. Social cognition: the key factor predicting social outcome in people with schizophrenia? Psychiatry. 2010;7:41–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penn DL, Sanna LJ, Roberts DL. Social cognition in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:408–411. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Couture SM, Penn DL, Roberts DL. The functional significance of social cognition in schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:S44–SS63. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green MF, Leitman DI. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:670–672. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gard DE, Kring AM, Gard MG. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harvey PD, Koren D, Reichenberg A. Negative symptoms and cognitive deficits: what is the nature of their relationship? Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:250–258. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reickmann N, Reichenberg A, Bowie CR. Depressed mood and its functional correlates in institutionalized schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2005;77:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabbag S, Twamley EW, Vella L. Predictors of the accuracy of self assessment of everyday functioning in people with schizophrenia. Submitted for publication. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horan WP, Kring AM, Gur RE. Development and psychometric validation of the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS) Schizophr Res. 2011;132:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kollias CT, Kontaxakis VP, Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ. Association of physical and social anhedonia with depression in the acute phase of schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2008;41:365–370. doi: 10.1159/000152378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Medalia A, Revheim N, Casey M. Remediation of memory disorders in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2000;30:1451–1459. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi J, Mogami T, Medalia T. Intrinsic Motivation Inventory: an adapted measure for schizophrenia research. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:966–976. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allison DB, Newcomer JW, Dunn AL. Obesity among those with mental disorders: a National Institute of Mental Health meeting report. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150:1115–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298:1794–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10:52–77. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoang U, Stewart R, Goldacre MJ. Mortality after hospital discharge for people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: retrospective study of linked English hospital episode statistics, 1999-2006. BMJ. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5422. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capasso RM, Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM. Mortality in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: an Olmsted County, Minnesota cohort: 1950-2005. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alley DE, Chang VW. The changing relationship of obesity and disability, 1988-2004. JAMA. 2007;29:2020–2027. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain NB, Al Adawi S, Dorvlo AS. Association between body mass index and functional independence measure in patients with deconditioning. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87:21–25. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31815e61af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strassnig M, Brar JS, Ganguli R. Body mass index and quality of life in community-dwelling patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;62:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolotkin R, Corey-Lisle PK, Crosby RD. Impact of obesity on health-related quality of life in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Obesity. 2008;16:749–754. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strassnig M, Brar JS, Ganguli R. Low cardiorespiratory fitness and physical functional capacity in obese patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;126:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vankampfort D, Probst M, Scheewe T. Lack of physical activity during leisure time contributes to an impaired health related quality of life in patients with early schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2011;129:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parameswaran K, Todd DC, Soth M. Altered respiratory physiology in obesity. Can Respir J. 2006;13:203–210. doi: 10.1155/2006/834786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleg JL, Piña IL, Balady G. Assessment of functional capacity in clinical and research applications: an advisory from the Committee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention, Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;102:1591–1597. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.13.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fentem PH. ABC of sports medicine. Benefits of exercise in health and disease. BMJ. 1994;308:1291–1295. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6939.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]