Abstract

Exposure to an acute stressor of inescapable swimming or intermittent tailshocks impairs classical eyeblink conditioning 24 h later in female rats (Wood, Beylin, & Shors, 2001). This effect is often attributed to a deficit in “learning,” but since stress has been shown to induce analgesia (Jackson, Maier, & Coon, 1979), an alternative explanation is that stressor exposure reduces conditioning by lessening the perceived intensity of the unconditioned stimulus (US). To address this possibility we examined the amplitude of the unconditioned response (UR) during training and found that although exposure to the stressor impaired trace conditioning, there was no difference in the UR amplitude. We also found that eyeblink responses to different US intensities (4–12 V) in the absence of training were unaffected by stressor exposure. Taken together, these experiments indicate that the stress-induced impairment of conditioning in females is not due to a decreased perception of US strength.

Keywords: Sex differences, Estrogen, Analgesia, Hippocampus, Unconditioned stimulus, Performance, Gender

Classical eyeblink conditioning is becoming an increasingly important paradigm for the study of learning. In our rat version of eyeblink conditioning, a white noise conditioned stimulus (CS) precedes and predicts an unconditioned stimulus (US), which is a periorbital shock to the eyelid. Through this pairing, the CS comes to elicit an eyeblink, or conditioned response (CR). Using this paradigm we have found that exposure to an acute stressor of inescapable tailshocks or forced swimming facilitates classical eyeblink conditioning 24 h later in male rats (Beylin & Shors, 1998; Shors, Weiss, & Thompson, 1992). In females, however, exposure to these same stressors impairs eyeblink conditioning (Shors, Lewczyk, Pacynski, Mathew, & Pickett, 1998; Wood, Beylin, & Shors, 2001; Wood & Shors, 1998). In both cases, stress is thought to modulate learning directly, but an alternative interpretation is that prior stressor exposure affects performance during eyeblink conditioning, and not learning, per se. In males, several possible performance explanations have been addressed (Servatius, Brennan, Beck, Beldowicz, & Coyle-DiNorcia, 2001; Shors, 2001), but less has been done to rule out performance deficits in females (but see Wood & Shors, 1998). Most notably, acute exposure to inescapable shock has been shown to induce analgesia 24 h after the stress or exposure if animals are “reminded” of the event (Jackson, Maier, & Coon, 1979). So, there remains the possibility that analgesia caused by stressor exposure prior to training reduces the perceived intensity of the training stimuli. If, for example, the US eyelid shock is perceived as less intense—and is therefore less salient—less conditioning would occur in stressed females.

One way of evaluating the salience of the US is to examine the magnitude of the UR. A more salient US will elicit an eyeblink UR with a larger amplitude, whereas a less salient stimulus will elicit a smaller response (Servatius, 2000). Using a technique developed by Servatius (2000), the present study tested whether stressor exposure changes the amplitude of the UR. In experiment 1, the UR amplitudes of female rats exposed to a stressor and then trained on trace eyeblink conditioning were compared to those from unstressed controls. To further test for stress-induced analgesia, both groups were given the hot plate test following training. In a second experiment, we used US alone presentations to further investigate the UR at several different US intensities, and without the possible confounds of the conditioning paradigm used in the first experiment.

Female Sprague–Dawley rats, 200–330 g were individually housed on wire racks with ad libitum food and water, and were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle, lights on at 8 am. The stress-induced impairment of eyeblink conditioning is affected by estrogen levels, with the largest deficit occurring when females are stressed during late diestrus (low estrogen levels) and then trained during proestrus (high estrogen levels) (Shors et al., 1998). To control for the estrous cycle we examined vaginal cytology daily until it was verified that each subject cycled twice through all phases of the cycle within 4–5 days. To obtain cell samples, loose vaginal cells were removed with cotton tipped applicators soaked in saline and rolled onto slides. The slides were stained with 1% toluidine blue and the estrous phase was assessed. Proestrus was marked by purple staining of epithelial cell nuclei; estrus was marked by dark blue clumped cornified cells; and diestrus was marked by dark leukocytes with scattered epithelial cells. Animals with abnormal cycles were excluded from the study.

For eyeblink surgery, rats were anesthetized with a small dose of sodium-pentobarbitol (15 mg/kg) and then maintained on isofluorine and oxygen. Four electrodes (insulated stainless steel wire 0.005 in.) attached to a head stage were implanted through the upper eyelid with the insulation through the muscle removed. The head stage was attached to the skull with dental cement and four anchoring screws.

Following at least one week of recovery, rats in diestrus were given 45 min of acclimation to the conditioning environment. The chamber consisted of an illuminated (7.5 W bulb) inner chamber (22 cm × 26 cm × 25 cm) with metal walls and a grounded floorgrid, within a sound-attenuating outer chamber (51 cm × 52 cm × 35 cm). Following acclimation, half the animals were returned to their homecages, while the other half were placed in Plexiglas restraining tubes and exposed to a stressor of 30 tailshocks (1 s; 1 mA) at a rate of 1/min.

Twenty-four hours after acclimation and stressor exposure, females (then in proestrus) were returned to the chamber for conditioning between 2 and 5 pm. Conditioning consisted of 200 trials a day for 2 days. For trace eyeblink conditioning a 250 ms white noise (82db, with a 25 ms rise/fall time) CS was separated from a 10 ms square-wave pulse to the eyelid (10 V) US by a 500 ms trace interval. Trials were presented in groups of 10 in the following order: 1 CS-alone trial, 4 paired trials, 1 US-alone trial, and 4 paired trials. The intertrial interval was randomized between 20 and 30 s.

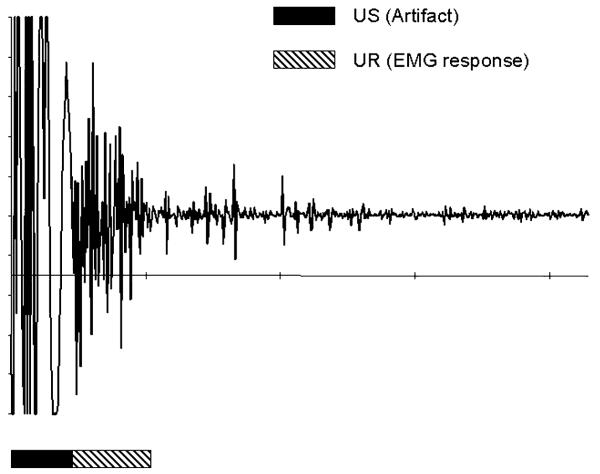

For eyeblink analysis, both CRs and URs were measured by changes in EMG activity recorded from the obicularis oculi muscle via two electrodes connected to a differential amplifier with a 300–500 Hz band pass filter and amplified × 10 k. EMG signals were relayed to a computer and digitized at 1000 samples/s with an A/D board. For CRs, EMG responses were scored as “eyeb links” when they exceed the trial baseline by 4 SD for 7 ms in a 10 ms period. An eyeblink was considered a CR if it occurred within 500 ms before the US presentation. Only the 10 US alone trials were analyzed for URs. They were assessed during a 100 ms period beginning 50 ms after the US presentation to allow for the artifact to dissipate. A UR was counted when the EMG response exceeded a baseline recording by 4 SD for 5 ms out of a 6 ms period (Fig. 1).UR amplitude was recorded as the absolute value of the largest peak/trough within a UR response.

Fig. 1.

The figure depicts the EMG response to the US. The artifact from the 10 ms, 10 V, square-wave pulse US is underlined in black, whereas the EMG of the UR is underlined in black and white hatched marks. The opening of the eyelid after the US can be observed and analyzed under these conditions.

Immediately after training, general analgesia was measured using the hotplate test to examine the paw-lick withdrawal response. Subjects were placed within a chamber (29 cm × 19.5 cm × 30 cm) on a modified hotplate (29 cm × 19.5 cm) that was kept between 52 and 53 °C. Latency to lick either back paw was recorded.

For the second experiment the subjects and procedures were the same as in the first experiment except that females were not exposed to paired stimuli. Instead, they were exposed to 50 US alone presentations of intensities ranging from 4 to 12 V (10 trials per voltage). US presentations were made at voltages that increased by 2 V from 4 to 12 V then decreased by 2 V from 12 to 4 V for 10 repetitions. The amplitude of the UR was assessed as previously described in experiment 1. Additionally, the number of blinks per voltage level was assessed.

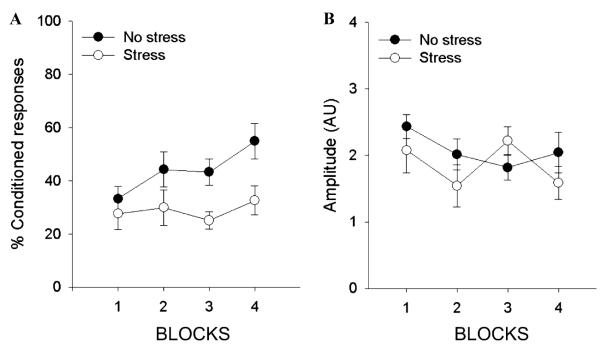

Results for the first experiment were analyzed with a repeated measures ANOVA revealing that both stressed (n = 8) and unstressed (n = 7) females emitted more CRs across blocks of 100 trials [F (3, 39) = 4.21, p < 05] and thus both groups showed evidence of conditioning. However, the percentage of CRs in the stressed group was smaller [F (1, 13) = 5.39, p < 05] (Fig. 2A) replicating the finding that stressor exposure decreases conditioning in females (Shors et al., 1998). Stressor exposure did not, however, affect the amplitude of the UR [F (1, 13) = 0.58, p > .05] (Fig. 2B). Likewise, an independent samples t test performed on the hot plate data showed no difference in the analgesic response between stressed and unstressed groups [t(10) = 0.91, p > .05].

Fig. 2.

(A) Stressor exposure significantly impaired conditioning in female rats compared to unstressed controls, as measured by the number of CRs across 4 blocks of 100 trials each. (B) Stressor exposure did not affect the amplitude of the UR (measured in arbitrary units), as measured during 10 US alone test trials per block.

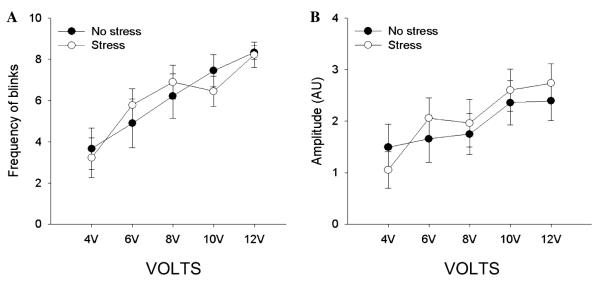

For the second experiment, a repeated measures ANOVA indicated that higher US voltage increased the number of URs [F (4, 64) = 24.44 p < .05] as well as their amplitude [F (4, 64) = 11.89, p < .05]. However, there no effect of stressor exposure (n = 9) on number of blinks [F (1, 16) = 0.00, p > .05] (Fig. 3A) or blink amplitude [F (1, 16) = 0.08 p > .05] (Fig. 3B) when compared to unstressed animals (n = 9).

Fig. 3.

(A) In both stressed and unstressed animals, the number of blinks increased with US intensity and there was no difference in the number of blinks at each voltage between stressed and unstressed animals. (B) Blink amplitude also increased with US intensity in both stressed and unstressed animals and there was no difference in the blink amplitude between groups.

In the first experiment, we replicated previous findings showing that exposure to an acute stressful event of intermittent tailshocks impairs trace eyeblink conditioning in female rats (Shors & Miesegaes, 2002; Wood & Shors, 1998). Stressor exposure did not, however, alter the magnitude of the UR. Since UR magnitude can be used to determine the perceived intensity of the US, this suggests that the US is not less salient for animals exposed to the stressor. Furthermore, exposure to the stressor did not affect general analgesia as measured by the hot plate test after training. In the second experiment, we again used stressed and unstressed females to investigate the UR, at several different US intensities, and without the potential confound of conditioning. As in the first experiment, there was no difference in UR magnitude between groups. Additionally, there was no difference in the number of blinks between groups at any of the US voltages. As expected, there was an increase in both the number of emitted URs and the UR amplitude with higher US voltages, indicating that these measures were, in fact, sensitive to changes in US salience. Thus, stressor exposure does not change the perceived intensity of the US, at least as reflected in the UR. A recent study reported that exposure to a stressor of inescapable tailshock reduced the magnitude of the UR in female rats during delay eyeblink conditioning (Beck & Servatius, 2003). However, more intense and longer duration of shocks were used and rats were trained 2 h after stressor exposure and at a time when stress-induced analgesia is more likely to occur. As shown here, we find no evidence for a decrease in the magnitude of the UR. Our results do not necessarily conflict with Beck and Servatius (2003) since the stressor and time of training were different. Together these findings suggest that it may be preferable to assess performance at least 1 day after stressor exposure and thereby avoid the potential problems that analgesia can impose on measures of learning.

Like the present study, previous experiments from our lab have attempted to rule out nonspecific effects on sensory/motor function as explanations for the effect of stress on conditioning in females. For example, stressor exposure does not modify gross motor activity (Shors & Wood, 1995), spontaneous blinking (Wood & Shors, 1998), or responding to an explicitly unpaired CS (Wood & Shors, 1998). Furthermore, stressor exposure does not affect analgesia as measured by the tail-flick (Wood & Shors, 1998). Additionally, the effect is not due to stimulus generalization between the tailshock and eyelid stimulation because a stressor of forced swimming also impairs conditioning in females (Shors et al., 1998). The present study adds to this body of evidence by showing that exposure to an acute stressor does not change the perceived intensity of the US. In combination, this supports the conclusion that the detrimental effect of stress on classical eyeblink conditioning reflects a deficit in learning, and not performance.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to David Waxler for writing the analysis programs. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (59970) and the National Alliance for Research on Depression and Schizophrenia to T.J.S. and by a predoctoral National Institute of Mental Health training Grant (AG19957-06) to D.B.

References

- Beck KD, Servatius RJ. Stress and cytokine effects on learning: What does sex have to do with it? Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science. 2003;38:179–188. doi: 10.1007/BF02688852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beylin AV, Shors TJ. Stress enhances excitatory trace eyeblink conditioning and opposes acquisition of inhibitory conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1998;112:1327–1338. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson RL, Maier SF, Coon DJ. Long-term analgesic effects of inescapable shock and learned helplessness. Science. 1979;206:91–93. doi: 10.1126/science.573496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servatius RJ. Eyeblink conditioning in the freely moving rat: square-wave stimulation as the unconditioned stimulus. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2000;102:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servatius RJ, Brennan FX, Beck KD, Beldowicz D, Coyle-DiNorcia K. Stress facilitates acquisition of the classically conditioned eyeblink response at both long and short interstimulus intervals. Learning and Motivation. 2001;32:178–192. [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ. Acute stress rapidly and persistently enhances memory formation in the male rat. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2001;75:10–29. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1999.3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Lewczyk C, Pacynski M, Mathew PR, Pickett J. Stages of estrus mediate the stress-induced impairment of associative learning in the female rat. NeuroReport. 1998;9:419–423. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Miesegaes G. Testosterone in utero and at birth dictates how stressful experience will affect learning in adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:13955–13960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202199999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Weiss C, Thompson RF. Stress-induced facilitation of classical conditioning. Science. 1992;257:537–539. doi: 10.1126/science.1636089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Wood GE. Contribution of stress and gender to exploratory preferences for familiar versus unfamiliar conspecifics. Physiology and Behavior. 1995;58:995–1002. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00153-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood GE, Beylin AV, Shors TJ. The contribution of adrenal and reproductive hormones to the opposing effects of stress on trace conditioning in males versus females. Behavioral Neuro-science. 2001;115:175–187. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.115.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood GE, Shors TJ. Stress facilitates classical conditioning in males, but impairs classical conditioning in females through activational effects of ovarian hormones. Protocols of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95:4066–4071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]