Abstract

Background.

The degree of involvement by the next-of-kin in deceased organ procurement worldwide is unclear. We investigated the next-of-kin’s authority in the procurement process in nations with either explicit or presumed consent.

Methods.

We collected data from 54 nations, 25 with presumed consent and 29 with explicit consent. We characterized the authority of the next-of-kin in the decision to donate deceased organs. Specifically, we examined whether the next-of-kin’s consent to procure organs was always required and whether the next-of-kin were able to veto procurement when the deceased had expressed a wish to donate.

Results.

The next-of-kin are involved in the organ procurement process in most nations regardless of the consent principle and whether the wishes of the deceased to be a donor were expressed or unknown. Nineteen of the 25 nations with presumed consent provide a method for individuals to express a wish to be a donor. However, health professionals in only four of these nations responded that they do not override a deceased’s expressed wish because of a family’s objection. Similarly, health professionals in only four of the 29 nations with explicit consent proceed with a deceased’s pre-existing wish to be a donor and do not require next-of-kin’s consent, but caveats still remain for when this is done.

Conclusions.

The next-of-kin have a considerable influence on the organ procurement process in both presumed and explicit consent nations.

Keywords: consent, deceased donor, health policy, law, next-of-kin

Introduction

There is a global organ shortage while the number of individuals on waiting lists continues to grow [1–4]. In 2010, 4529 Canadians were on the waiting list and 247 died waiting [5]. Similarly, there are currently 7686 individuals in the UK on the waiting list and 111 105 such individuals in the USA [6, 7]. To address this organ shortage, policy makers in various nations have debated the merits of legislative changes to consent policies for organ donation after death [8–10]. One strategy that has been vigorously debated in several nations is the implementation of ‘presumed consent’ for deceased organ donation. Presumed consent, sometimes referred to as the ‘opt-out’ approach, is a legislative organ donation policy that assumes an individual has a desire to donate unless he or she makes a statement of objection to donation. In contrast, explicit consent policies such as ‘first person consent’ require an individual to ‘opt-in’ by proactively affirming a desire to be a donor such as signing a donor card or indicating donor status on a driver’s license. Otherwise the next-of-kin is consulted to determine the deceased’s preferences with respect to deceased organ donation.

Nations with presumed consent have higher rates of deceased organ donation when contrasted to nations with explicit consent [11–13]. However, some authors remain unconvinced that presumed consent legislation alone explains this variation [14, 15]. There has also been resistance by the North American public to the idea of switching to an opt-out system [16, 17]. Interestingly, there is considerable range in the proportion of family members who refuse donation in both explicit and presumed consent nations, and both consent systems have an average family refusal rate of 34–38% [18]. However, data on family refusals are very limited, and values are not available for all nations. Due to the nature of deceased donation, the next-of-kin are often relied on by transplant officials in the organ procurement process. We set out to determine whether there are similarities across the two consent systems in how the next-of-kin are involved in the decision to donate after death. Specifically, we examined whether in practice nations always require the next-of-kin’s consent to procure organs, and whether the next-of-kin were able to veto procurement when the deceased had expressed a wish to donate. We collected data from 54 nations to compare and contrast the authority of next-of-kin in explicit and presumed consent systems for deceased organ donation.

Materials and methods

Definitions of presumed and explicit consent

We used World Health Organization definitions of presumed and explicit consent [19]. Explicit consent is defined as a system in which ‘cells, tissues or organs may be removed from a deceased person if the person had expressly consented to such removal during his or her lifetime’. Presumed consent is defined as a system that ‘permits material to be removed from the body of a deceased person for transplantation and, in some countries, for anatomical study or research, unless the person had expressed his or her opposition before death by filing an objection with an identified office or an informed party reports that the deceased definitely voiced an objection to donation’. Some nations have also proposed a ‘soft’ presumed consent law, where the next-of-kin is still involved in the donation decision [20].

Eligible nations

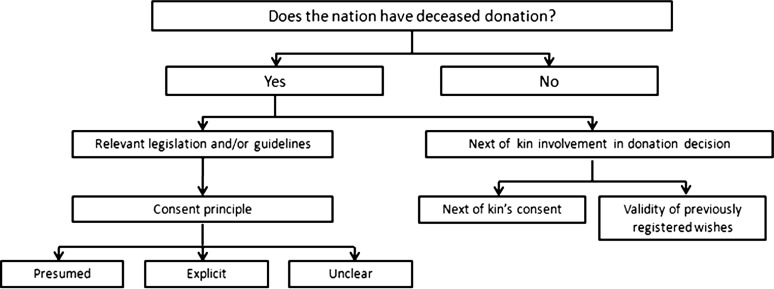

Our data of interest, next-of-kin involvement in deceased organ donation in nations with presumed and explicit consent, are presented in Figure 1. We first considered all nations where deceased organ donation is practiced as identified by the World Health Organization. We collected relevant transplant legislation and/or guidelines from each nation and categorized each nation as either presumed or explicit consent [19]. Foreign language legislation was translated into English. An example of a deceased donation clause that was interpreted as presumed consent was ‘if a deceased person did not express objection, when alive, it is allowed to recover cells, tissues or organs from such person human cadaver for transplantation purposes [21]’. An example of an explicit consent clause was ‘any person who has attained the age of 16 years may consent, (i) in writing signed by the person at any time or (ii) orally in the presence of a least two witnesses during the person’s last illness that the person’s body or the part or parts thereof specified in the consent be used after the person’s death for therapeutic purposes, medical education or scientific research [22]’. For nations with state level legislation, attempts were made to obtain each state’s legislation to determine if there was a difference in consent policies between states.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of data collected for each eligible nation.

Data collection

Data collection occurred from May 2009 to August 2010. Data were independently abstracted by a single author (A.M.R.) from government websites, legal databases and kidney, nephrology and transplantation foundations’ websites. Data were then independently reviewed by a second author (L.D.H.) for accuracy. Our categorization of each nation as presumed or explicit consent was verified with a second source, such as a published scientific article (Supplementary Appendix 1). In most cases, we also collected information directly from health professionals via electronic mail to ensure proper classification of the nation’s consent principle, confirm the appropriate legislation was collected and gain insight into the daily practices of deceased organ procurement (Supplementary Appendix 2). We gathered information to characterize the authority of the next-of-kin in the donation decision, specifically whether nations always required the next-of-kin’s consent and whether a validly recorded wish to be a donor was fulfilled. Electronic mail was utilized because of its ability to provide a clear paper trail and help reduce language misinterpretations. Telephone calls were utilized when requested, after which a follow-up email summarizing the call was sent back to the health professional for member checking. Health professionals included members of national kidney, nephrology and transplant foundations, ministry of health personnel and transplant staff. We sent all findings back to health professionals via electronic mail for review to ensure data quality and accuracy.

Results

We obtained data from 49 (75%) of the 65 nations reported to have active deceased organ donation programs by the World Health Organization (Supplementary Appendix 3) [M. Carmona (personal communication)]. An additional five nations (Armenia, Belarus, Costa Rica, Ecuador and Malta) were found through contact with nation representatives to also have deceased organ donation, so the total number of countries included in this review was 54 (Table 1, Figure 2). For the 16 missing nations, data collection was incomplete either because the required information was not available and/or because the health professional was non-responsive.

Table 1.

Legislation by nationa

| Nation | Province/Territory/State/Region | Name of legislation | Consent | Source | Source type |

| Armenia | Law on Organ and Tissue Transplantation, 2002 | Presumedb | National Assembly of the Republic of Armenia [23] (Hovhannisyan, L. Yerevan. June 2010) | Website and personal communication | |

| Australia | Australian Capital Territory | Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1978 | Explicit | The ACT Legislation Register [24] | Website |

| New South Wales | Human Tissue Act 1983 | New South Wales Government [25] | Website | ||

| Northern Territory | Human Tissue Transplant Act 1979 | Northern Territory Government—Department of the Chief Minister [26] | Website | ||

| Queensland | Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1979 | Queensland Government—Office of the Queensland Parliamentary Counsel [27] | Website | ||

| South Australia | Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1983 | Government of South Australia—Attorney-General’s Department [28] | Website | ||

| Tasmania | Human Tissue Act 1985 | Tasmania’s Consolidated Legislation Online [29] | Website | ||

| Victoria | Human Tissue Act 1982 | Victoria Government Health Information [30] | Website | ||

| Western Australia | Human Tissue and Transplantation Act 1982 | Government of Western Australia—State Law Publisher [31] | Website | ||

| Austria | Hospitals Law of 18 December 1956, Paragraph 62a-e, 1982 | Presumed | Gesundheit Österreich GmbH [32] | Website | |

| Belarus | Law of the Republic of Belarus ‘On Transplantation of Human Organs and Tissues’ | Presumed | The Belarusian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education (Komisarov, K. Minsk. June 2010) | Personal communication | |

| Belgium | Law of 13 June 1986 | Presumedc | Moniteur Belge [33] | Website | |

| Brazil | Law No. 9.434 of 4 February 1997 | Explicit | Ministério da Saúde [34–36] | Website | |

| Law No. 10.211 of 23 March 2001 | |||||

| Decree No. 2.268 of 30 June 1997 | |||||

| Canada | Alberta | Human Tissue and Organ Donation Act, 2006 | Explicit | CanLII Database [22, 37–48] | Website |

| British Columbia | Human Tissue Gift Act 1996 | ||||

| Manitoba | Human Tissue Gift Act, 1987 | ||||

| New Brunswick | Human Tissue Gift Act, 2004 | ||||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Human Tissue Act, 1990 | ||||

| Northwest Territories | Human Tissue Act, 1988 | ||||

| Nova Scotia | Human Tissue Gift Act, 1989 | ||||

| Nunavut | Human Tissue Act, 1988 | ||||

| Ontario | Trillium Gift of Life Network Act, 1990 | ||||

| Prince Edward Island | Human Tissue Donation Act, 1988 | ||||

| Quebec | Civil Code of Quebec | ||||

| Saskatchewan | Human Tissue Gift Act, 1978 | ||||

| Yukon | Human Tissue Gift Act, 2002 | ||||

| Chile | Law No. 20.413 of January 6, 2010 | Presumedd | Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile [49] | Website | |

| Colombia | Law No. 9, 1979 | Presumed | Punta Cana Group [50] | Website | |

| Law No. 73, 1988 | |||||

| Law No. 919, 2004 | |||||

| Decree 2493, 2004 | |||||

| Resolution 2640, 2005 | |||||

| Costa Rica | Law No. 7409 of 27 October 1994 | Presumed | Punta Cana Group [50] | Website | |

| Croatia | Law RH 50/88 | Presumed | Donor Network of Croatia [51] | Website | |

| Law RH 177/2004 | |||||

| Rule No. 152/2005 | |||||

| Cuba | Law No. 41 of 13 July 1983 on public health | Explicit | Legislative Responses to Organ Transplantation [52] | Book | |

| Decree No. 139 of 4 February 1988 | Trasplante [53] | Website | |||

| Czech Republic | Act 285/2002 Coll. Of 30 May 2002 on donation, removal, and transplantation of organs and tissues | Presumed | Transplants Coordinating Center (KST) (Fryda, P. Prague. March 2010) | Personal communication | |

| Denmark | Sundhedsloven – LBK No. 95 of 7 February 2008 | Explicit | Retsinformation [54] | Website | |

| Ecuador | Law No. 58 of 27 July 1994 | Presumed | Instituto Ecuatoriano de Dialisis y Trasplantes (Ortiz-Herbener, F. Guayaquil. July 2009) | Personal communication | |

| Estonia | Rakkude, Kudede Ja Elundite Käitlemise Ja Siirdamise Seadus | Explicit | Electronic Riigi Teataja (ERT) [55] | Website | |

| Finland | No. 101/2001 Act on the medical use of human organs and tissues | Presumed | Finlex [56, 57] | Website | |

| Law No. 547 of 11 May 2007 amending Law No. 101 | |||||

| France | Public Health Code | Presumed | Legifrance [58] | Website | |

| The Transplantation Act, 5 November 1997 | Explicit | Deutsche Stiftung Organ transplantation (Norba, D. June 2009. Frankfurt) Bundesgesetzblatt online [59] | Personal communication | ||

| Germany | Amendments to the Transplantation Act, 2007 | Website | |||

| Iceland | Act No. 16 of 6 March 1991 | Explicit | Althingi [60] | Website | |

| India | Act No. 42 of 1994, Transplantation of Human Organs Act | Explicit | CommonLII [61] MOHAN Foundation [62] | Website | |

| Transplantation of Human Organs (Amendment) Rules 2008 | Website | ||||

| Ireland | n/a | Explicit | n/a | n/a | |

| Israel | Organ Transplant Act, 2008 | Explicit | Israel Ministry of Health (Ashkenazi, T. Tel Aviv. May 2010) | Personal communication | |

| Italy | Law No. 91 of 1 April, 1999 Ministerial Decree of 8 April 2000 | Presumed | Portale Della Normativa Sanitaria [63, 64] | Website | |

| Japan | Law No. 104 of 16 July 1997e | Explicit | WHO International Digest of Health Legislation [65] | Website | |

| Kuwait | Decree-Law No. 55 of 20 December 1987 | Explicit | Legislative Responses to Organ Transplantation [52] | Book | |

| Lithuania | Law on Donation and Transplantation of Human Tissues, Cells and Organs | Explicit | Lithuanian National Transplantation Bureau (NTB) [66] | Website | |

| Luxembourg | Law of 25 November 1982 | Presumed | Luxembourg-Transplant [67] | Website | |

| Malaysia | Human Tissues Act 1974 | Explicit | The Attorney General of Malaysia [68] | Website | |

| Malta | n/a | Explicit | Transplant Support Group (Debattista, A. Hamrun. June 2010) | Personal communication | |

| Mexico | Ley General de Salud | Explicit | Centro Nacional de Trasplantes [69] | Website | |

| Reglamento de la Ley General de Salud | |||||

| Lineamientos para la asignación y distribución de órganos y tejidos | |||||

| Netherlands | The Organ Donation Act, 1996 | Explicit | Overheid [70] | Website | |

| New Zealand | Human Tissue Act 2008 | Explicit | The Parliamentary Counsel Office (PCO) [71] | Website | |

| Norway | Law No. 6 of 9 February 1973 | Presumed | Lovdata [72] | Website | |

| Paraguay | Law No. 1246/98 | Presumed | Punta Cana Group [50] | Website | |

| Philippines | Republic Act No. 7170 | Explicit | Chan Robles Virtual Law Library [73] | Website | |

| Poland | The Cell, Tissue and Organ Recovery, Storage and Transplantation Act, 2005 | Presumed | Poltransplant [21] | Website | |

| Romania | Law No. 95/2006 | Explicit | Agenţtia Nationalã de Transplant [74] | Website | |

| Russia | Law of 22 December 1992 | Presumed | Central Clinical Hospital of Russian Academy of Sciences (Pishchita, A. Moscow. June 2010) | Personal communication | |

| Saudi Arabia | Procedure of Deceased Organ Donation | Explicit | Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation [75] | Website | |

| Singapore | Human Organ Transplant Act | Presumed | Singapore Statutes Online [76, 77] | Website | |

| The Medical (Therapy, Education and Research) Act | |||||

| Slovak Republic | Law 576/2004, of 21 October 2004 | Presumed | Slovenské Centrum Orgánových Transplantácií [78] | Website | |

| Slovenia | The Removal and Transplantation of Human Body Parts for the Purposes of Medical Treatment Act | Presumed | Uradni list RS [79] | Website | |

| South Africa | National Health Act, 2003 | Explicit | Department of Health [80] | Website | |

| South Korea | Law 8852 | Explicit | Ulsan University Medical College (Kim, J. H. Seoul, June 2010) | Personal communication | |

| Spain | Law No. 30 of 27 October 1979 RD 2070/1999 on the removal and transplantation of organs | Presumed | Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation [81] | Website | |

| Sweden | Law No. 831 of 1 June 1995 | Presumed | Riksdag [82] | Website | |

| Switzerland | Federal Act of 8 October 2004 on the Transplantation of Organs, Tissues and Cells (Transplantation Act)f | Explicit | The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation [83] | Website | |

| Thailand | Rules of the Medical Council on the Observance on Medical Ethics | Explicit | Chulalongkorn University (Nivatvongs, S. Bangkok. June 2010) | Personal communication | |

| Medical Council's Announcement on Criteria for Brain Death Diagnosis | |||||

| Tunisia | Law No. 91-22 of 25 March 1991 | Presumed | CHU la Rabta (Hamouda, C. Tunis. June 2010) | Personal communication | |

| Law No. 49 of 12 June 1995 | |||||

| Law No. 18 of 1 March 1999 | |||||

| Decree No. 97 of 13 June 1997 | |||||

| Ordinance of 28 July 2004 | |||||

| Turkey | Law #2238 of 29 May 1979 | Presumed | Turkish Transplantation Society [84] | Website | |

| Law #2594 of 21 January 1982 | |||||

| UK | Human Tissue Act 2004g | Explicit | Office of Public Sector Information [85, 86] | Website | |

| Human Tissue (Scotland) Act 2006 | |||||

| USA | Uniform Anatomical Gift Acth | Explicit | National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws [87] | Website | |

| Venezuela | Law of 3 December 1992 | Explicit | Punta Cana Group [50] | Website |

n/a = not applicable.

Switched to ‘soft’ presumed consent March 2009.

Removed a clause that allowed next-of-kin to object to donation in the absence of a registered wish to donate February 2007. In practice next-of-kin’s objection still respected in absence of a registered decision.

Changed from explicit consent to presumed consent January 2010.

In July 2009 revisions were adopted that will be in effect in 1 year [R. Ida (personal communication)].

A federal law was in enacted July 2007 abolishing the previous mixture of presumed and explicit consent canons (states).

Applies to England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The most recent version of the UAGA has been implemented in the various states. A list can be found at http://www.anatomicalgiftact.org.

Fig. 2.

54 nations studied. Explicit consent nations in black, presumed consent countries in gray.

Legislation

Of the 54 nations, 25 have presumed consent and 29 have explicit consent. As detailed in Table 1 the consent principle has been changed or modified in five nations in recent years (Armenia, Belgium, Chile, Japan and Switzerland). We focused on their most current practice for this report. Two countries (Ireland and Malta) do not have official legislation regarding deceased organ donation, but both were operating under explicit consent when the study was conducted.

Role of next-of-kin in decision making

Nations with presumed consent

In all 25 nations with presumed consent, next-of-kin are informed of the intention to recover organs (Table 2). Variations exist in Austria and Russia, where it is necessary for the next-of-kin to be physically present in the hospital at the time of procurement to object to donation. All presumed consent nations provide a method for individuals to opt-out of donation. In addition, 19 of the 25 nations with presumed consent also provide a mechanism for individuals to register their wishes to be a donor, such as affirmative registration in an electronic registry. We found that 21 of the 25 presumed consent nations allow the next-of-kin to object and prevent a potential donation. In the other four nations (Belgium, France, Poland and Sweden) health professionals do not override the deceased’s registered wish to be a donor in the case of an objection from next-of-kin but will respect an objection if there is no such record. Exceptions and caveats to these practices are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Role of next-of-kin in presumed consent nations

| Nation | Next-of-kin informed | Next-of-kin’s authorization required if wishes are unknowna | Next-of-kin can veto donation |

| Armenia | Yes | n/a | Yes |

| Austria | Yesb | n/a | Yesb |

| Belarus | Yes | n/a | Yesc |

| Belgium | Yes | Nod | Noe |

| Chile | Yes | n/a | Yesf |

| Colombia | Yes | Yesg | Yes |

| Costa Rica | Yes | Yesg | Yes |

| Croatia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Czech Republic | Yes | n/a | Yes |

| Ecuador | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Finland | Yes | Yes | Noe |

| France | Yes | Noh | Yes |

| Italy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Luxembourg | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Norway | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Paraguay | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Poland | Yes | Noh | Yes |

| Russia | Yesb | Yesb | Yesb |

| Singapore | Yes | Yes | Noe |

| Slovak Republic | Yes | n/a | Yes |

| Slovenia | Yes | Yes | Yesi |

| Spain | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sweden | Yes | Noj | Noe |

| Tunisia | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Turkey | Yes | Yes | Yes |

‘Wishes Unknown’ refers to nations that provide a method for individuals to express a desire to be a donor in addition to a method to objecting to deceased donation. Nations that do not provide such a means are marked not applicable (n/a).

Next-of-kin must be present in the hospital at the time of donation for their opinion to be considered.

The transplant co-ordinator has the discretion to choose if the next-of-kin’s permission is necessary. In addition, there is an authorized law agent in attendance during procurement.

The next-of-kin are informed of the intended procurement but permission is not explicitly asked. An objection will be respected.

If the deceased expressed their wish to donate, then only they can revoke the decision and upon death their decision will be respected and next-of-kin will not be able to revoke it.

Legally, the next-of-kin’s permission is not required if no objection is made, but if there are doubts, the next-of-kin are consulted.

Presumed consent is only practiced if the next-of-kin are unreachable or unknown.

When the deceased’s wishes are unknown, the next-of-kin is asked what the deceased’s opinion on organ donation was. However, if the next-of-kin objects to donation the removal will not occur.

In rare cases where the next-of-kin raises an objection against donation the physician can decide not to proceed with removal, if he/she feels continuing would have a major negative impact on the next-of-kin.

If next-of-kin do not object, procurement will proceed under the presumption of consent. However, next-of-kin have a legal right to object and must be informed of this right. If they cannot be reached, donation may not occur.

Nations with explicit consent

In all 29 nations with explicit consent, the next-of-kin are approached regardless of whether the wishes of the deceased are known or not. In all 29 nations, authorization from the next-of-kin is required for organ procurement if the deceased’s wishes are unknown (Table 3). In cases where the deceased validly registered their wish to become a donor, procurement will occur in four nations without requiring next-of-kin’s authorization (the Netherlands, Romania, UK and most of the USA). However, there are exceptions and changes occurring in all four nations, presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Role of next-of-kin in explicit consent nationsa

| Nation | Next-of-kin’s authorization is required if deceased’s wishes are unknown | Next-of-kin’s consent is required even if deceased’s wishes are documented |

| Australia | Yes | Yes |

| Brazil | Yes | Yes |

| Canada | Yes | Yes |

| Cuba | Yes | Yes |

| Denmark | Yes | Yes |

| Estonia | Yes | Yes |

| Germany | Yes | Yes |

| Iceland | Yes | Yes |

| India | Yes | Yes |

| Ireland | Yes | Yes |

| Israel | Yes | Yes |

| Japan | Yes | Yes |

| Kuwait | Yes | Yes |

| Lithuania | Yes | Yes |

| Malaysia | Yes | Yes |

| Malta | Yes | Yes |

| Mexico | Yes | Yes |

| Netherlands | Yes | Nob |

| New Zealand | Yes | Yes |

| Philippines | Yes | Yes |

| Romania | Yes | Noc |

| Saudi Arabia | Yes | Yes |

| South Africa | Yes | Yes |

| South Korea | Yes | Yes |

| Switzerland | Yes | Yes |

| Thailand | Yes | Yes |

| UK | Yes | Nob |

| USA | Yes | Nod |

| Venezuela | Yes | Yes |

In accordance with the lack of assumption of consent in explicit consent, all nations with explicit consent systems in this study approached the next-of-kin about organ donation (whether the deceased’s wishes to be a donor were known or unknown).

A strong objection by the next-of-kin donation will stop procurement to avoid causing a major negative impact on the next-of-kin.

Permission is not formally asked or required, an objection will be respected.

States with first person consent make the deceased’s registered wishes paramount and procurement can occur with consent from the next-of-kin. However next-of-kin are required for a medical and social history of the potential donor before procurement can occur [M. Devenny (personal communication)].

Discussion

Several nations have debated the merits of changing the consent principle of deceased donation legislation from explicit to presumed consent [88–91]. Presumed consent nations have been shown to have statistically higher rates of deceased donation than explicit consent nations [11–13]. However, even supporters of presumed consent legislation concede that it is one of the more controversial strategies to improving donation rates in explicit consent nations, and it could divert attention and efforts from other proven strategies [92]. Indeed, studies conducted on both the Canadian and American public demonstrate a resistance to switching to this type of consent system [16, 17]. The importance of public support for such a legislative change was exemplified by Brazil’s unsuccessful implementation of presumed consent, which resulted in the policy being reverted back to explicit consent [93]. There has also been a recent call for research on personal-level factors that may affect deceased donation rates, particularly the role of next-of-kin [94].

To address this need, we conducted a global review to better understand the authority next-of-kin have in the decision to pursue deceased organ donation in nations with presumed and explicit consent. The results of this study help inform the current debate as to whether nations with explicit consent should consider a switch to presumed consent legislation to improve their deceased organ donation programs. Organ procurement systems are complex with key differences between what is legislated and what is done in practice. We found that many nations with presumed consent legislation follow a much softer system of consent in reality, which almost always includes next-of-kin in the decision making. The next-of-kin have a considerable influence over the decision to procure organs in both presumed and explicit consent nations. For example, while it was expected that next-of-kin approval would be required for procurement in all explicit consent nations, we were surprised to learn the same is true in many nations with presumed consent and that most countries permit next-of-kin to object to donation. Furthermore, of the 19 presumed consent nations that provide a method for individuals to express a wish to be a donor, 15 nations still require the next-of-kin’s authorization for organ procurement even when the deceased has registered a wish to become a donor. Deceased donation rates without context can also be misleading. For example, according to the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, Spain (a presumed consent nation) has the highest deceased donation rate per million population (p.m.p.) (34.13 p.m.p.) [95]. However, the founder and director of the Organizacion Nacional de Trasplantes (Spain’s governing transplantation organization) has repeatedly noted that Spain’s high levels of deceased donation should be attributed to its ‘Spanish Model’ rather than its legislation [14, 96, 97]. In Spain, transplant co-ordinators are required by law to search for a refusal by the deceased but since there is no national non-donor registry and most individuals do not record their decision (e.g. by carrying a donor card), the next-of-kin are consulted as a proxy decision-maker [98]. In addition, a series of organizational measures including a multi-level transplant co-ordinator network are used to facilitate transplantation [99]. It remains unclear whether the Spanish Model is feasible for nations with different infrastructure and economic constraints. An interesting comparison is the USA, which has the third highest rate for deceased donation across all nations and the highest rate amongst nations with explicit consent (26.27 p.m.p.) [95]. The USA has focused on maximizing the consent rate from next-of-kin. Available data show that the proportion of families that refuse donation varies considerably in both explicit and presumed consent nations, although on average both consent systems have a family refusal rate of approximately 34–38% [18]. Unfortunately, data on family refusals are very limited, and this value should be interpreted with caution since values are not available from all nations, rendering the rate to be inconclusive. Even so, previous work and our review both suggest that improvement of factors such as next-of-kin consent may have a larger and more immediate effect on transplantation rates than legislative changes [15]. Our results suggest that the next-of-kin strongly influence the decision to pursue organ donation in both consent systems. Future studies investigating the relationship between family refusals and donation rates are warranted.

Some donation programs have recognized this area of opportunity and are trying to improve next-of-kin authorization through the transplant co-ordinator. Training programs, such as the European Donor Hospital Education Programme (EDHEP) and the Donor Action Program, are designed to help improve the transplant staff’s communication about death and donation to the next-of-kin [92,100–102]. There has also been a focus on the dialogue between the co-ordinator and the next-of-kin. The ‘presumptive approach’ utilizes assumptive language, for example saying ‘when you decide to donate’ instead of ‘if you decide to donate’ [103]. The style has been criticized as undermining free and informed consent [104]. A less assumptive approach is used by some transplant co-ordinators in presumed consent European nations, wherein they ask the next-of-kin what the deceased would have wanted instead of explicitly asking for consent. Proponents of this method argue that the burden of the decision is placed back on the deceased instead of the next-of-kin [92]. Encouragingly, this style is not limited to presumed consent nations and is meant to be part of ‘first person consent’ [105]. Future studies on the exact phrasing transplant co-ordinators employ when approaching the next-of-kin about donation and variations in practice worldwide are warranted.

The limitations of our study are that we were unable to describe practices in 16 (25%) nations where transplantation is performed because of unreliable or unavailable data. We also dichotomized data for comparison reasons; however, it should be emphasized that these data are highly nuanced. However, our study does have a number of strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study to compare the authority of the next-of-kin in organ donation decision making in nations with explicit and presumed consent. We collected data from 54 nations to provide a broad overview of the issue, and we included nations from all five major regions as defined by the United Nations [106]. We only reported data collected and confirmed by health professionals to ensure accuracy.

It is important to emphasize that deceased donation programs are complex, affected not only by law, administration and infrastructure but also ideology and values. It is improbable that any single strategy or approach will cause a marked improvement on deceased donation rates. While presumed consent nations have demonstrated higher rates of deceased donation, the authority of the next-of-kin in the procurement process is a feature policy makers should factor into their decision when deciding whether to switch to presumed consent legislation. When an individual dies, best methods to support the wishes of the deceased, the wishes of the next-of-kin and the practice of transplantation remain a focus for research and quality improvement.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available online at http://ndt.oxfordjournals.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank health professionals from 54 nations who provided or reviewed data for accuracy. We thank Dariuz Gozdzik and Stephen Woo for their help with translation.

Funding. L.H. was supported by a Schulich Graduate Scholarship from the University of Western Ontario and a research award from the Lawson Health Research Institute. Dr A.G. was supported by a Clinician Scientist Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Aubrey P, Arber S, Tyler M. The organ donor crisis: the missed organ donor potential from the accident and emergency departments. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1008–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirste G. Organ exchange in Europe–barriers and perspectives for the future. Ann Transplant. 2006;11:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santiago-Delpin EA. The organ shortage: a public health crisis. What are Latin American governments doing about it? Transplant Proc. 1997;29:3203–3204. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)00870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langone AJ, Helderman JH. Disparity between solid-organ supply and demand. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:704–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe038117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.e-Statistics Report on Transplant, Waiting List and Donor Statistics. Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2010. Canadian Institute for Health Information. http://www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/internet/en/document/types+of+care/specialized+services/organ+replacements/report_stats2010 (19 May 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weekly Statistics. NHS Blood and Transplant. 2011. http://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/ukt/statistics/latest_statistics/latest_statistics.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Organ; Procurement and Transplantation Network. Current U.S. Waiting List. 2011. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/ (19 May 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brindley M. Another Step Forward in Campaign for Presumed Consent. WalesOnline; 2010. http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/health-news/2010/03/03/another-step-forward-in-campaign-for-presumed-consent-91466-25949977/ (24 March 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard C. Organ Donor Bill Sparks Testimony. The Journal Star. 2010. http://www.pjstar.com/news/x1669540174/Organ-donor-bill-sparks-testimony. [Google Scholar]

- 10.CTV Toronto. NDP wants law presuming consent for organ donation. The Canadian Press; 2008. http://toronto.ctv.ca/servlet/an/local/CTVNews/20080729/organ_donation_080729/20080729/?hub=TorontoNewHome. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abadie A, Gay S. The impact of presumed consent legislation on cadaveric organ donation: a cross-country study. J Health Econ. 2006;25:599–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gimbel RW, Strosberg MA, Lehrman SE, et al. Presumed consent and other predictors of cadaveric organ donation in Europe. Prog Transplant. 2003;13:17–23. doi: 10.1177/152692480301300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horvat LD, Cuerden MS, Kim SJ, et al. Informing the debate: rates of kidney transplantation in nations with presumed consent. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:641–649. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-10-201011160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matesanz R, Fabre JW. Too many presumptions. The Guardian. 2010. ; http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2008/nov/17/organ-donation-health (4 March 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpkin AL, Robertson LC, Barber VS, et al. Modifiable factors influencing relatives' decision to offer organ donation: systematic review. BMJ. 2009;338:b991. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallup Organization I. 2005. National Survey of Organ and Tissue Donation Attitudes and Behaviors. U S Department of Health and Human Services; ftp://ftp.hrsa.gov/organdonor/survey2005.pdf (21 March 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canadian Blood Services. 2010. Views Toward Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation. Ipsos Reid; http://www.bloodservices.ca/CentreApps/Internet/UW_V502_MainEngine.nsf/resources/Releases/$file/IPSOS+Report.pdf (21 March 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organización Nacional de Trasplantes. 2010. The Committee of Experts on the Organisational Aspects of Co-operation in Organ Transplantation. International Figures on Donation and Transplantation—2009. http://www.ont.es/publicaciones/Documents/Newsletter2010.pdf (17 May 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. WHO Guiding Principles on Human Cell, Tissue and Organ Transplantation. World Health Organization; 2009. http://www.who.int/transplantation/TxGP08-en.pdf (5 November 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sells RA. What is transplantation law and whom does it serve? Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1191–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poltransplant. 2005. The Cell, Tissue and Organ Recovery, Storage and Transplantation Act, 2005. http://www.poltransplant.pl/Download/transplantation_act.pdf (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 22.CanLII Database. 2010. Trillium Gift of Life Network Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. H.20. http://www.canlii.org/en/on/laws/stat/rso-1990-c-h20/latest/rso-1990-c-h20.html (4 March 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Assembly of the Republic of Armenia. 2009. Law on Organ and Tissue Transplantion 2002. http://www.parliament.am/legislation.php?sel=show&ID=1308&lang=rus (24 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 24.ACT Government. The ACT Legislation Register. 2009. Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1978. http://www.legislation.act.gov.au/a/1978-44/default.asp (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 25.NSW Legislation. 2010. Human Tissue Act 1983. http://www.legislation.nsw.gov.au/maintop/view/inforce/act+164+1983+cd+0+N (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Department of Health and Families. Human Tissue Transplant Act. Northern Territory Government. 2010 Available from: URL: http://notes.nt.gov.au/dcm/legislat/legislat.nsf/d7583963f055c335482561cf00181d19/3c2a5eb42a22878e692577540008776c?OpenDocument (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1979. Office of the Queensland Parliamentary Counsel. http://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/LEGISLTN/CURRENT/T/TransplAAnatA79.pdf (25 August 2010, date last accessed)

- 28.Attorney-General's Department. 2007. Transplantation and Anatomy Act 1983. http://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/LZ/C/A/TRANSPLANTATION%20AND%20ANATOMY%20ACT%201983.aspx (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tasmania's Consolidated Legislation Online. 2010. Human Tissue Act 1985. http://www.thelaw.tas.gov.au/tocview/index.w3p;cond=;doc_id=118%2B%2B1985%2BAT%40EN%2B20100826130000;histon=;prompt=;rec=;term= (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Victoria Government Health Information. 2010. Human Tissue Act 1982. http://www.health.vic.gov.au/humantissue/htact (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 31.State Law Publisher. 2008. Human Tissue & Transplantation Act 1982. http://www.slp.wa.gov.au/legislation/statutes.nsf/main_mrtitle_436_homepage.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gesundheit Österreich GmbH. 2010. Austrian Hospitals Act. http://www.goeg.at/index.php?pid=arbeitsbereichedetail&ab=110&smark=hospitals+law&noreplace=yes (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moniteur Belge. 2008. Law of 13 June 1986. http://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=nl&la=N&cn=1986061337&table_name=wet (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ministério da Saúde. 1997. Law No. 9.434 of 4 February 1997. http://dtr2001.saude.gov.br/transplantes/portaria/lei9434 (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ministério da Saúde. 1997. Decree No. 2.268 of 30 June 1997. http://dtr2001.saude.gov.br/transplantes/portaria/dec2268.htm (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ministério da Saúde. 2001. Law No. 10.211 of 23 March 2001. http://dtr2001.saude.gov.br/transplantes/portaria/lei10211.htm (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 37.CanLII; Database. Human Tissue and Organ Donation Act, 2006. 2009. http://www.canlii.org/en/ab/laws/stat/sa-2006-c-h-14.5/latest/sa-2006-c-h-14.5.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 38.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Gift Act, 1996. http://www.canlii.org/en/bc/laws/stat/rsbc-1996-c-211/latest/ (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 39.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Gift Act, 1987. http://www.canlii.org/mb/laws/sta/h-180/index.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 40.CanLII Database. 2008. Human Tissue Gift Act, 2004. http://www.canlii.org/nb/laws/sta/h-12.5/index.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 41.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Act, 1990. http://www.canlii.org/nl/laws/sta/h-15/20051121/whole.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 42.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Act, 1988. http://www.canlii.org/nt/laws/sta/h-6/index.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 43.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Gift Act, 1989. http://www.canlii.org/en/ns/laws/stat/rsns-1989-c-215/latest/ (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 44.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Act, 1988. http://www.canlii.org/en/nu/laws/stat/rsnwt-nu-1988-c-h-6/latest/rsnwt-nu-1988-c-h-6.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 45.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Donation Act, 1988. http://www.canlii.org/pe/laws/sta/h-12.1/index.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 46.CanLII Database. 2010. Civil Code of Quebec. http://www.canlii.org/en/qc/laws/stat/sq-1991-c-64/latest/sq-1991-c-64.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 47.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Gift Act, 1978. http://www.canlii.org/en/sk/laws/stat/rss-1978-c-h-15/latest/ (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 48.CanLII Database. 2010. Human Tissue Gift Act, 2002. http://www.canlii.org/yk/laws/sta/117/index.html (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. 2010. Law No. 20.413 of January 6, 2010. http://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1010132&idParte=&idVersion=2010-01-15 (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grupo Punta Cana. 2010. Legislation. http://www.grupopuntacana.org/mlegislacion.htm (25 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donor Network of Croatia. 2010. The Laws on Transplantation in Croatia. http://hdm.hr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=259:zakoni-o-transplantaciji-u-hrvatskoj&catid=48:zakoni-i-pravilnici&Itemid=70 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 52.World Health Organization. Legislative Responses to Organ Transplantation. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trasplante. 2010. Decree No. 139 of 4 February 1988. http://www.sld.cu/galerias/pdf/sitios/trasplante/decreto_139.pdf (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Retsinformation. 2008. Sundhedsloven. https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=114054#Kap12 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Electronic Riigi Teataja. Rakkude, Kudede Ja Elundite Käitlemise Ja Siirdamise Seadus. 2009. http://www.riigiteataja.ee/ert/act.jsp?id=12980151 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Finlex. No. 101/2001 Act on the Medical Use of Human Organs and Tissues. 2001. http://www.finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/2001/en20010101.pdf (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finlex. 2007. Law No. 547 of 11 May 2007 amending Law No. 101. http://www.finlex.fi/sv/laki/kokoelma/2007/20070081.pdf (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Legifrance. 2010. Public Health Code. http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichCode.do;jsessionid=6DF5BA38AE889EEB9D4B0BFE06417070.tpdjo06v_3?idSectionTA=LEGISCTA000006171785&cidTexte=LEGITEXT000006072665&dateTexte=20000621 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bundesgesetzblatt online. 2007. Amendments to the Transplantation Act, 2007. http://www.bgbl.de/Xaver/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 60.Althingi. 2009. Act No. 16 of 6 March 1991. http://www.althingi.is/lagas/137/1991016.html (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 61.CommonLII. 1994. Transplantation of Human Organs Act 1994. http://www.commonlii.org/in/legis/num_act/tohoa1994339/ (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 62.MOHAN Foundation. 2008. The Transplantation of Human Organs Rules, 2008. http://www.mohanfoundation.org/tho/tho_rules1.asp (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Portale Della Normativa Sanitaria. 1999. Law No. 91 of 1 April, 1999. http://www.normativasanitaria.it/jsp/dettaglio.jsp?id=19372 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Portale Della Normativa Sanitaria. 2000. Ministerial Decree of 8 April 2000. http://www.normativasanitaria.it/jsp/dettaglio.jsp?id=17738 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 65.WHO International Digest of Health Legislation. 1997. Law No. 104 of 16 July 1997. http://apps.who.int/idhl-rils/results.cfm?language=english&type=ByTopic&strTopicCode=IVC&strRefCode=Jap (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lithuanian National Transplantation Bureau. 2006. Law on Donation and Transplantation of Human Tissues, Cells and Organs. http://www.transplantacija.lt/content/teisesaktai.en.html (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luxembourg-Transplant. 2010. Law of 25 Nobember 1982. http://www.dondorganes.public.lu/fr/que-dit-loi/index.html (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 68.Human Tissues Act 1974. The Attorney General of Malaysia 2006; http://www.agc.gov.my/Akta/Vol.%203/Act%20130.pdf (26 August 2010, date last accessed)

- 69.Centro Nacional de Trasplantes. Marco Normativo. 2009. http://www.cenatra.salud.gob.mx/interior/marco_normativo_presentacion.html (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 70.The Organ Donation Act, 1996. Overheid 2009; http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0008066/geldigheidsdatum_16-07-2009 (26 August 2010, date last accessed)

- 71.Human Tissue Act 2008. The Parliamentary Counsel Office 2008; http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2008/0028/latest/DLM1152940.html (26 August 2010, date last accessed)

- 72.Lovdata. Law No. 6 of 9 February 1973. 2008. http://www.lovdata.no/cgi-wift/wiftldles?doc=/usr/www/lovdata/all/nl-19730209-006.html&emne=transplantasjonslov*&& (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chan Robles Virtual Law Library. Republic Act No. 7170. 1992. http://www.chanrobles.com/republicactno7170.htm (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 74.Agenþtia Nationalã de Transplant. Legislaþie. 2010. http://www.transplant.ro/Lege.htm (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 75.Saudi; Center for Organ Transplantation. Procedure of Deceased Organ Donation. 2010. https://www.scot.org.sa/en/en/directory-of-regulations/procedure-of-deceased-organ-donation.html (20 October 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 76.Human Organ Transplant Act. 2009. Singapore Statutes Online. http://statutes.agc.gov.sg/non_version/cgi-bin/cgi_retrieve.pl?actno=REVED-131A&doctitle=HUMAN%20ORGAN%20TRANSPLANT%20ACT%0a&date=latest&method=part&sl=1 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 77.The Medical (Therapy, Education and Research) Act. Singapore Statutes Online. 2010. http://statutes.agc.gov.sg/non_version/cgi-bin/cgi_retrieve.pl?&actno=Reved-175&date=latest&method=part (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 78.Slovenské Centrum Orgánových Transplantácií. 2004. Law 576/2004, of 21 October 2004. http://www.ncot.sk/ (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 79.Uradni list RS. The Removal and Transplantation of Human Body Parts for the Purposes of Medical Treatment Act. 2000. http://www.uradni-list.si/1/content?id=22590&part=&highlight=presaditvi (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 80.National Health Act 2003. Department of Health 2004. http://www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id=68039 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 81.Legislaciones Espana. Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. 2006. http://www.transplant-observatory.org/rcidt/Legislaciones/Forms/AllItems.aspx?RootFolder=%2frcidt%2fLegislaciones%2fEspana&FolderCTID=&View=%7bF8D89988%2d7B84%2d42B3%2dA966%2d618ADAE61FA7%7d (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 82.Riksdag. 2006. Law No. 831 of 1 June 1995. http://www.riksdagen.se/webbnav/index.aspx?nid=3911&bet=1995:831 (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 83.The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation. Federal Act of 8 October 2004 on the Transplantation of Organs, Tissues and Cells (Transplantation Act) The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation; 2007. http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/810_21/index.html (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Turkish Transplantation Society. Organ Transplantation Law. 1982. http://www.tond.org.tr/ (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 85.Human Tissue Act 2004. Office of Public Sector Information 2004; http://www.opsi.gov.uk/ACTS/acts2004/ukpga_20040030_en_1 (26 August 2010, date last accessed)

- 86.Human Tissue (Scotland) Act 2006. Office of Public Sector Information 2006; http://www.opsi.gov.uk/legislation/scotland/acts2006/asp_20060004_en_1 (26 August 2010, date last accessed)

- 87.Uniform Anatomical Gift Act. National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. 2010. http://www.anatomicalgiftact.org (26 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 88.DeMeer A. National Strategy Needed for Donation of Organs. London Free Press; 2011. http://www.lfpress.com/comment/editorial/2011/05/19/18165841.html (20 May 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 89.McDonagh M. Tackling the decline in organ donor rates. Irish Times. 2011 http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/health/2011/0329/1224293284073.html (20 May 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 90.National Assembly for Wales. Inquiry into Presumed Consent for Organ Donation. National Assembly for Wales; 2008. http://www.assemblywales.org/cr-ld7192-e.pdf (20 May 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 91.Scott O, Jacobson E. Implementing presumed consent for organ donation in Israel: public, religious and ethical issues. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9:777–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roels L, Rahmel A. The European experience. Transpl Int. 2011;24:350–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Csillag C. Brazil abolishes “presumed consent” in organ donation. Lancet. 1998;352:1367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60767-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rithalia A, McDaid C, Suekarran S, et al. Impact of presumed consent for organ donation on donation rates: a systematic review. BMJ. 2009;338:a3162. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Organ Donation and Transplantation: Activities, Laws and Organization 2010. Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. 2010. Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. http://www.transplant-observatory.org/Data%20Reports/2010%20Report%20final.pdf (15 October 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 96.Matesanz R, Miranda B. A decade of continuous improvement in cadaveric organ donation: the Spanish model. J Nephrol. 2002;15:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Matesanz R. Spain: a leader in harvesting hearts for transplantation. Circulation. 2007;115:f45–f46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61342-6. Rodriguez-Arias DF, Wright LF, Paredes D. Success factors and ethical challenges of the Spanish Model of organ donation. Lancet 2010; 376: 1109–1112 [1474–547X (Electronic)] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Quigley M, Brazier M, Chadwick R, et al. The organs crisis and the Spanish model: theoretical versus pragmatic considerations. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:223–224. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.023127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Blok GA, van DJ, Jager KJ, et al. The European Donor Hospital Education Programme (EDHEP): addressing the training needs of doctors and nurses who break bad news, care for the bereaved, and request donation. Transpl Int. 1999;12:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s001470050205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Roels L, Spaight C, Smits J, et al. Critical care staffs' attitudes, confidence levels and educational needs correlate with countries' donation rates: data from the donor action database. Transpl Int. 2010;23:842–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van DJ, Blok GA, Morley MJ. Participants' judgements of the European Donor Hospital Education Programme (EDHEP): an international comparison. Transpl Int. 1999;12:182–187. doi: 10.1007/s001470050208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zink S, Wertlieb S. A study of the presumptive approach to consent for organ donation: a new solution to an old problem. Crit Care Nurse. 2006;26:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Truog RD. Consent for organ donation–balancing conflicting ethical obligations. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1209–1211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0708194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hanto D, Peters T, Howard R, et al. Family disagreement over organ donation. Virtual Mentor. 2005 doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2005.7.9.ccas2-0509. , Vol.7. http://virtualmentor.ama-assn.org/2005/09/ccas2-0509.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.United Nations Statistics Division. Composition of Macro Geographical (Continental) Regions, Geographical Sub-regions, and Selected Economic and Other Groupings. 2010. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm ( 7 September 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.