Abstract

Peptidic oligomers that contain both α- and β-amino acid residues, in regular patterns throughout the backbone, are emerging as structural mimics of α-helix-forming conventional peptides (composed exclusively of α-amino acid residues). Here we describe a comprehensive evaluation of diverse α/β-peptide homologues of the Bim BH3 domain in terms of their ability to bind to the BH3-recognition sites on two partner proteins, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1. These proteins are members of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family, and both bind tightly to the Bim BH3 domain itself. All α/β-peptide homologues retain the side chain sequence of the Bim BH3 domain, but each homologue contains periodic α-residue → β3-residue substitutions. Previous work has shown that the ααβαααβ pattern, which aligns the β3-residues in a 'stripe' along one side of the helix, can support functional α-helix mimicry, and the results reported here support this conclusion. The present study provides the first evaluation of functional mimicry by ααβ and αααβ patterns, which cause the β3-residues to spiral around the helix periphery. We find that the αααβ pattern can support effective mimicry of the Bim BH3 domain, as manifested by the crystal structure of an α/β-peptide bound to Bcl-xL, affinity for a variety of Bcl-2 family proteins, and induction of apoptotic signaling in mouse embryonic fibroblast extracts. The best αααβ homologue shows substantial protection from proteolytic degradation relative to the Bim BH3 α-peptide.

INTRODUCTION

Biological systems frequently encode recognition information in α-helical segments of proteins, to be read out by complementary surfaces on partner proteins.1 Many groups have explored unnatural oligomers as replacements for the poly-α-amino acid backbone, with the goal of maintaining the three-dimensional arrangements of side chains that make partner contacts while eliminating susceptibility to proteolytic degradation and enhancing conformational stability.2 A long-term aim of such efforts is to identify design strategies that are broadly applicable to mimicry of diverse α-helical signals. This prospect is encouraged by the regularity of the α-helix itself. Modest structural deviations between the α-helix and an unnatural analogue may be tolerated for mimicry of short helices, but such deviations will become increasingly problematic as length increases. To date, oligomers with purely unnatural backbones (e.g., β-peptides,3 peptoids,4 aromatic-rich oligomers5) have been evaluated for mimicry of segments containing up to three consecutive α-helical turns; helical protein recognition motifs of this size can be mimicked also via more traditional medicinal chemistry strategies, which focus on small, non-oligomeric molecules.6 Covalent cross-linking strategies that stabilize α-helical conformations of peptides represent an alternative to unnatural backbones.7 Recent results with purely hydrocarbon cross-links, between pairs of side chains or between the backbone and a side chain, have been particularly impressive in terms of biological activity.

We have pursued an approach to functional α-helix mimicry that is conceptually related both to the use of purely unnatural backbones and to strategies that retain the natural α-amino acid backbone while introducing unnatural components to confer stability. Our approach is based on modifying a helix-forming sequence by partial replacement of the original α-amino acid residues with analogous β-amino acid residues.8 If the β3-residues are distributed throughout the sequence, the resulting α/β-peptides can display substantial resistance to proteolysis9 while retaining the ability to form an α-helix-like conformation. We have evaluated this strategy for mimicry of an α-helical prototype in two protein-recognition contexts: interaction between a BH3 domain and the complementary cleft on an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein,10,11 and interaction between the C-terminal heptad repeat (CHR) segment of HIV protein gp41 and the complementary groove formed by two adjacent N-terminal heptad repeat (NHR) segments of gp41.12 In both systems, we have achieved success with an ααβαααβ heptad repeat backbone pattern, which leads to alignment of the β-residues as a 'stripe' along one side of the α/β-peptide helix. This α/β pattern permits the segregation of the unnatural residues to a region of the helical surface that makes minimal contact with the partner protein surface. Here we extend the α/β approach by comprehensively evaluating all possible ααβαααβ, ααβ and αααβ repeat patterns in the context of mimicking the Bim BH3 domain. Previous studies of self-assembling α/β-peptides (derivatives of GCN4-pLI13) showed that all three of these α/β patterns can lead to formation of α-helix-like conformations.8b,c BH3 domain mimicry serves as a useful testbed for assessment of functional α-helix-based design strategies that can subsequently be extended to other, longer systems, as illustrated by our results with gp41 CHR mimicry (10 α-helical turns).12

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Binding survey of diverse α/β patterns

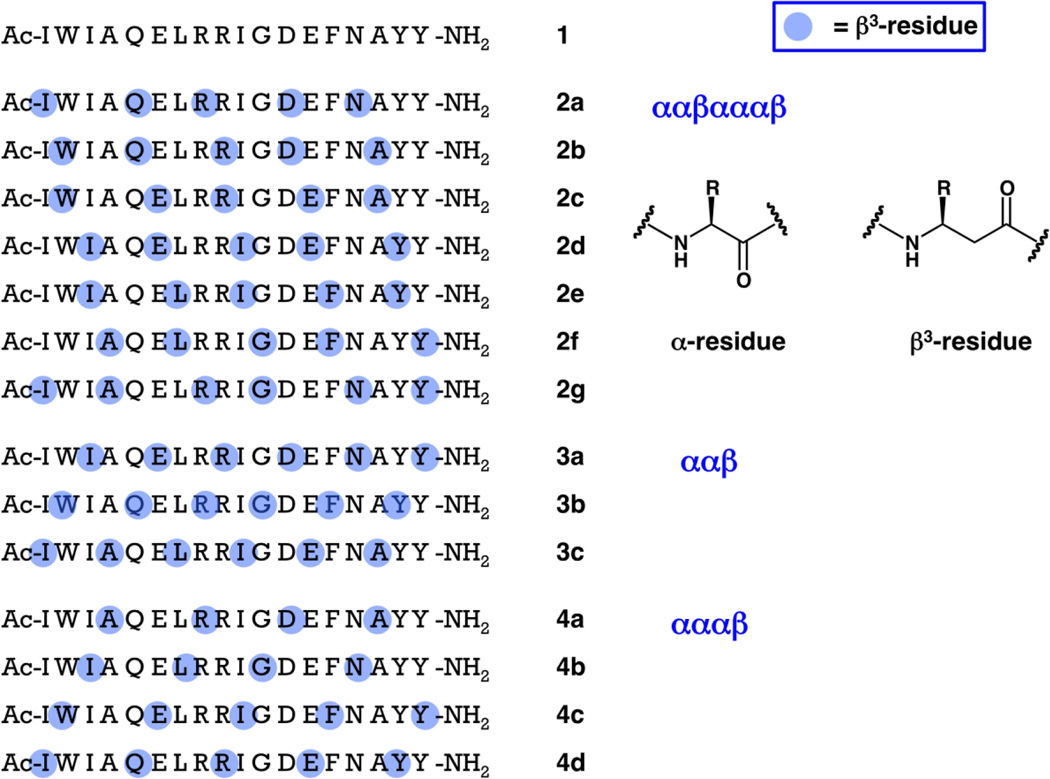

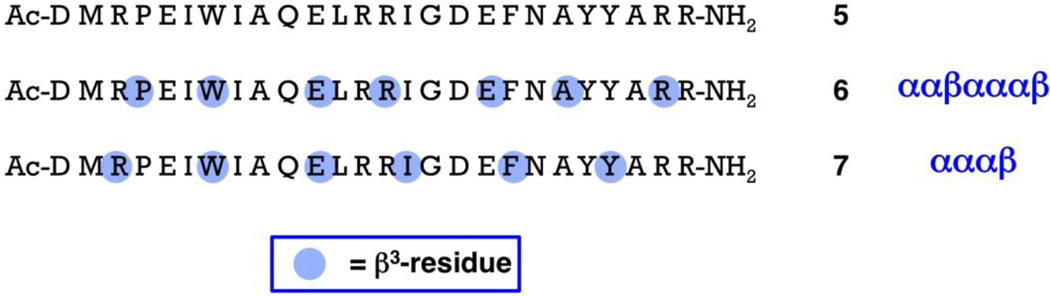

α/β-Peptides 2a–g, 3a–c and 4a–d share the side chain sequence of 18-mer α-peptide 1, which encompasses the core of the Bim BH3 domain plus some flanking residues (Figure 1). Each of these α/β-peptides contains α→β3 replacements at 5 or 6 of the 18 positions; the β3-amino acid residues retain the original Bim BH3 side chain but introduce a CH2 unit between the side chain-bearing carbon and the carbonyl. Members of family 2 share the ααβαααβ pattern, and all seven ways in which this pattern can be realized are represented. Family 3 contains all three versions of the ααβ pattern, and family 4 contains all four versions of the αααβ pattern. Prior studies of Bim BH3 have focused on longer peptides (α-residues only), such as 26-mer 5 (Figure 2),14 but during preliminary experiments we found that 18-mer 1 retains high affinity for the anti-apoptotic protein Mcl-1 and moderate affinity for Bcl-xL.15 Starting from a relatively short α-peptide prototype has facilitated our comprehensive evaluation of different α/β patterns because shorter peptides are generally easier to synthesize than longer analogues. This initial survey has allowed us to identify β3-residue patterns that ultimately proved to be very effective in the 26-mer format.

Figure 1.

Sequences of 18-mer α-peptide 1, derived from the Bim BH3 domain, and 18-mer α/β-peptides of families 2–4. The standard single-letter code is used to designate α-amino acid residues. Blue dots are used to indicate the positions of β3-amino acid residues, which bear the side chain of the α-amino acid residue identified by the single-letter code. Thus, all peptides shown here have the same sequence of side chains, but they have varying backbones (each β3-residue introduces an additional CH2 unit relative to the analogous α-residue).

Figure 2.

Sequences of 26-mer α-peptide 5, derived from the Bim BH3 domain, and 26-mer α/β-peptides 6 and 7, which are extensions of 18-mer α/β-peptides 2c and 4c, respectively. The standard single-letter code is used to designate α-amino acid residues. Blue dots are used to indicate the positions of β3-amino acid residues, which bear the side chain of the α-amino acid residue identified by the single-letter code. Thus, peptides 5–7 have the same sequence of side chains, but they have varying backbones (each β3-residue introduces an additional CH2 unit relative to the analogous α-residue).

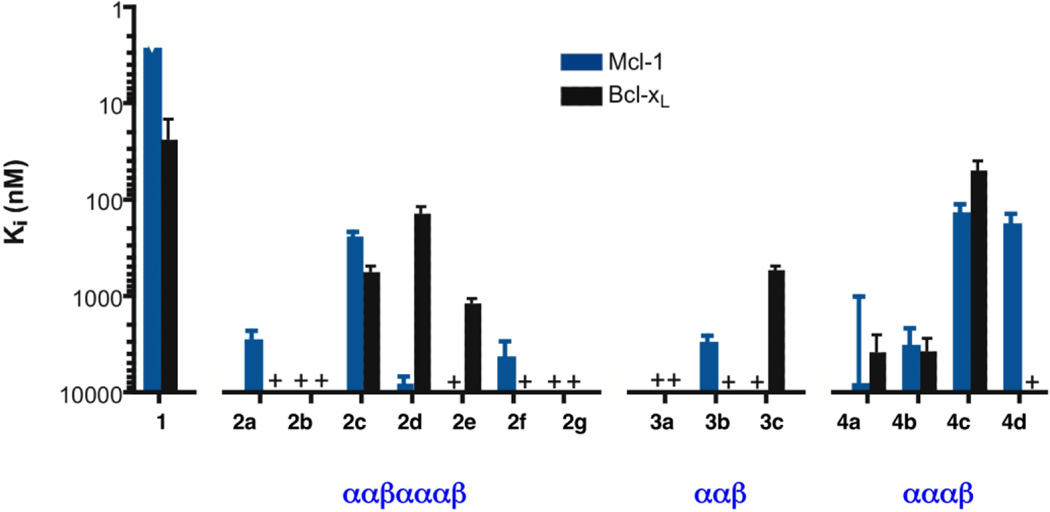

Figure 3 summarizes the affinities for Mcl-1 and for Bcl-xL of all possible α/β3 analogues of the Bim BH3 peptide 1 that have an ααβαααβ, ααβ or αααβ backbone pattern. We focused on Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL because these two anti-apoptotic proteins are representative of selectivity patterns among BH3 domains within the Bcl-2 family: some BH3 domain peptides (including Bim and Puma) are promiscuous and bind to all anti-apoptotic family members, but others bind to only select subsets.16 For example, Noxa binds to Mcl-1 but not Bcl-xL or Bcl-2, while Bad binds to Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 but not Mcl-1. The Ki data in Figure 3 were obtained via competition fluorescence polarization (FP) assays, in which each α/β-peptide is evaluated for its ability to displace from Bcl-xL or Mcl-1 a tight-binding, fluorophore-bearing BH3 domain peptide (a Bak-derived 16-mer and a Bim-derived 15-mer, respectively, that have been previously described).15 One among the ααβαααβ series approaches 1 in terms of binding to Bcl-xL (Ki ~ 23 nM for 1 vs. ~ 130 nM for 2d), and one among the αααβ series shows slightly improved affinity for this protein (Ki ~ 50 nM for 4c). A single member of the ααβ series binds detectably to Bcl-xL (Ki ~ 520 nM for 3c), with affinity 23-fold weaker than was observed for 1. The results obtained with Mcl-1 were less favorable than those obtained with Bcl-xL, since none of the 18-mer α/β-peptides approaches the high Mcl-1 affinity observed for the Bim BH3 α-peptide 1 (Ki < 3 nM). However, 2c, 4c and 4d displayed moderate affinity for Mcl-1. It is intriguing that some members of the α/β-peptide library display selectivity patterns distinct from that of the Bim BH3 prototype: α-peptide 1 binds ≥ 10-fold more tightly to Mcl-1 than to Bcl-xL, but 4c binds with similar affinities to these two proteins, and 2d binds ~60-fold more tightly to Bcl-xL than to Mcl-1.

Figure 3.

Graphical summary of inhibition constants (Ki) for binding to Mcl-1 (blue bars) or Bcl-xL (black bars) for 18-mer α-peptide 1 and homologous α/β-peptides in families 2–4, based on competition fluorescence polarization assays (see text for details). Note that the vertical axis is an inverse logarthmic scale, so that taller bars correspond to tighter binding (smaller Ki value, which should correspond to the Kd value).

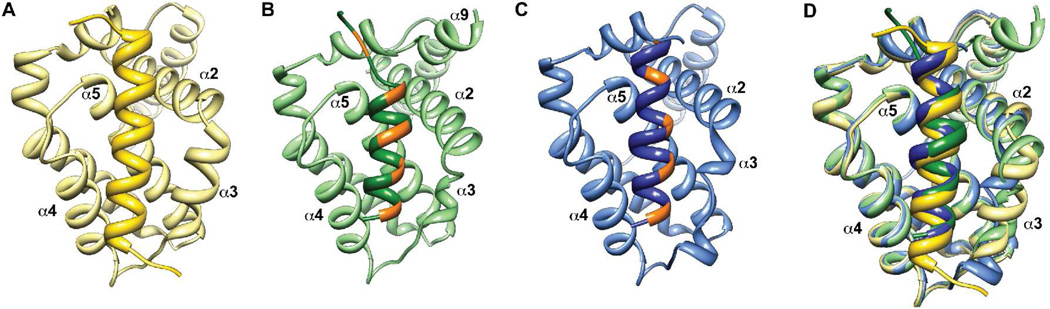

Co-crystal structures

We chose 2c and 4c among the 18-mer α/β-peptides for further scrutiny because each displayed significant affinity for both of the anti-apoptotic proteins employed in the initial binding studies. Each of these α/β-peptides was co-crystallized with Bcl-xL, and the structures of these complexes were solved to 1.5 Å (2c:Bcl-xL) and 2.5 Å (4c:Bcl-xL), respectively (Supplementary Table 3; Figures 4B,C). These new data enable a detailed comparison of the two α/β-peptide:Bcl-xL structures with the structure of Bim BH3 domain α-peptide 5 bound to Bcl-xL (PDB ID: 3FDL; Figure 4A). Bcl-xL is very similar in all cases, with the exception of helix α3, where differences in the traces of the backbones were observed (Figure 4D). This helix appears to be very flexible in Bcl-xL and has been shown to adopt different conformations depending on the identity of the bound ligand.18 Indeed, two different conformations for α3 are observed among the four copies of Bcl-xL found in the asymmetric unit of the complex with α/β-peptide 4c (only one of which is shown in Figures 4C,D). In the 2c:Bcl-xL complex, helix α9 is observed at the C-terminus of Bcl-xL (Figure 4B), but no electron density is apparent for this helix in the other structures. Overall, the similarities among Bcl-xL molecules in the various complexes suggest that it is reasonable to undertake detailed comparisons among the bound states of the Bim BH3 domain and the two different α/β-peptide analogues.

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of α-peptide 5 (A; yellow; PDB 3FDL17), α/β-peptide 2c (B; green) and α/β-peptide 4c (C; blue) bound to Bcl-xL. In each case only the backbone is shown. The BH3 domain-derived peptides are indicated by the darker-colored helix at the center of each panel; the lighter-colored portions correspond to Bcl-xL in each panel. For the two α/β-peptides, orange patches indicate the positions of the β3-residues. Both α/β-peptides bind comparably to Bim BH3-derived α-peptide 5 in a groove formed predominantly by helices α2-α5 of Bcl-xL. Part D shows an overlay of the three co-crystal structures, with colors as in parts A–C. Overall the structures are remarkably similar with the exception of the α3 helix of Bcl-xL.

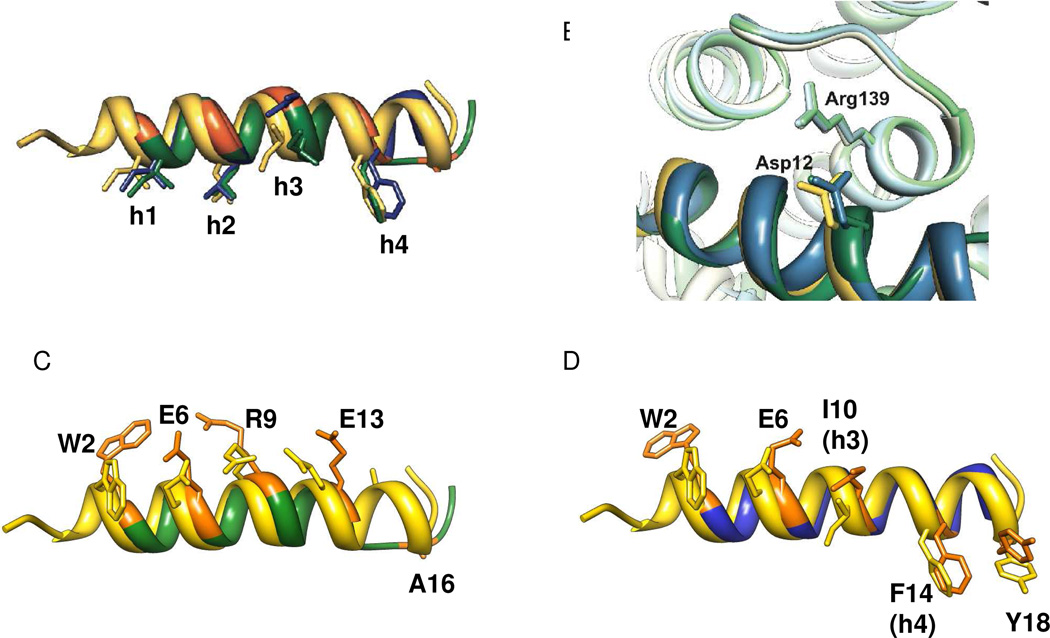

In both new structures the Bim-derived α/β-peptides make most or all of the expected side chain contacts with Bcl-xL, despite the multiple α→β3 substitutions (Figures 4 and 5). BH3 domain sequences are defined by four hydrophobic residues (at positions conventionally designated h1–h4) in a pattern that causes the nonpolar side chains to become aligned upon α-helix formation.11,19 In 18-mer α/β-peptide 2c, h1–h4 are Ile3, Leu7, Ile10 and Phe14, respectively, while in 4c these residues are Ile3, Leu7, β3-hIle10 and β3-hPhe14. In 26-mer α-peptide 5, h1–h4 are Ile8, Leu12, Ile15 and Phe19. These four side chains of α-peptide 5 dock into complementary pockets along the floor of the BH3-recognition groove of Bcl-xL, as is universally observed for BH3 domains bound to pro-survival proteins.11 The h1–h4 side chains of α/β-peptide 2c in the Bcl-xL-bound structure align well with those of α-peptide 5, and all four of these side chains from 2c occupy the appropriate pockets on Bcl-xL. α/β-Peptide 4c differs from α-peptide 5 and α/β-peptide 2c in that two of the key hydrophobic side chains are contributed by β3-residues, β3-hIle10 and β3-hPhe14, while all four key side chains are contributed by α-residues of 5 and 2c. Three of the four key hydrophobic side chains of α/β-peptide 4c, those at positions h1, h2 and h4, overlay reasonably well with the analogous side chains of α-peptide 5 (Figure 5A). The h3 side chain of 4c (β3-hIle10; blue in Figure 5A), however, deviates somewhat from the corresponding Ile side chains of 5 and 2c (Ile15 (yellow) and Ile10 (green), respectively); in contrast to the deep burial of the latter two side chains within the Bcl-xL cleft, the β3-hIle10 side chain of 4c is only partially buried.

Figure 5.

Overlay of α-peptide 5 (yellow), α/β-peptide 2c (green), and α/β-peptide 4c (blue) from the co-crystal structures shown in Figure 4. Part A highlights the positions of the h1–h4 side-chains. Part B highlights the intermolecular salt bridge between an Asp side chain on the outward-facing side of the α- or α/β-peptide and the Arg139 side chain from the Bcl-xL. Parts C and D show pairwise comparisons of α/β-peptide 5 with either α/β-peptide 2c (C) or α/β-peptide 4c (D). These images compare the β3-residue side chains of 2c or 4c with the corresponding α-residue side chains from 5; these side chains sets display a consistent offset for 2c (C) but not for 4c (D) except for the Trp residue, as discussed in the text.

In addition to the characteristic set of hydrophobic side chains, a second defining feature of BH3 domains is an Asp residue located between h3 and h4.11 Upon α-helix formation, the Asp side chain projects in a diametrically opposite direction relative to the h1–h4 stripe. Our structures of the 2c:Bcl-xL and 4c:Bcl-xL complexes reveal that the appropriate side chain carboxylate (Asp12 in each case) forms a salt bridge with Arg139 on the protein (Figure 5B), which matches the salt bridge observed in structures of authentic BH3 domain:anti-apoptotic protein complexes such as 5:Bcl-xL.17

Overlay comparisons of each Bcl-xL-bound α/β-peptide with Bim-derived α-peptide 5 are shown in Figures 5C (2c vs. 5) and 5D (4c vs. 5). In each case, the positions of the β3-residues within each α/β-peptide are highlighted in orange, and in these images the β3-residue side chains are orange as well (in contrast to Figure 5A). As anticipated, the ααβαααβ pattern of 2c causes the β3-residues to be aligned along one side of the helix (which is faces away from Bcl-xL; Figure 5C), while the α/β pattern of 4c causes the β3-residues to spiral around the helix periphery (Figure 5D). These images reveal unanticipated structural features. For 2c, the positions of all β3-residue side chains are spatially offset relative to the positions of the corresponding α-residue side chains in 5. In contrast, for 4c some of the β3-residue side chains align fairly closely with the corresponding α-residue, particularly those at position 10 (h4) and position 14. We speculate that partial alignment in the case of 4c arises because some β3-residue side chains make intimate contact with Bcl-xL. For 2c, on the other hand, there is not a strong need for side chain alignment, because in this case the β3-residues, and their α-residue counterparts on 5, project into the solvent.

The complex between α/β-peptide 2c and Bcl-xL displays one interesting difference relative to all complexes between BH3 domain α-peptides and pro-survival proteins: the α/β-peptide helix unwinds beyond Asn15. This C-terminal loss of helicity does not appear to be a consequence of crystal packing. The short non-helical segment of 2c includes one β3-residue, β3-hAla16, but any possible role of this unnatural subunit in the departure from helicity is impossible to determine by inspection of the crystal structure. The unusual conformation of the C-terminal segment of 2c allows this portion of the α/β-peptide to make contacts with Bcl-xL that have no parallels in other structures. For example, both β3-hAla16 and Tyr18 make nonpolar contacts with the protein surface, and there is an H-bond between the side chains of Tyr17 from 2c and Thr190 of the protein. It should be noted that comparable unwinding is not observed for α/β-peptide 4c, which is fully helical in the Bcl-xL-bound state. Nor is C-terminal helical unwinding observed in the recently reported crystal structure of a Puma-derived α/β-peptide bound to Bcl-xL. 10b The Puma-derived α/β-peptide has one additional C-terminal α-residue relative to 2c, and the side chain sequence is quite different from that of 2c, but these two α/β-peptides have in common the ααβαααβ backbone pattern, the β3-residue locations relative to the h1–h4 positions, and β3-hAla as the β3-residue nearest the C-terminus.

BH3 domain-derived α-peptides usually form very straight α-helices when bound to pro-survival proteins; for example, in the 5:Bcl-xL complex, the α-helix adopted by 5 has a 112 Å radius of curvature (a perfectly straight helix would have an infinite radius of curvature). α/β-Peptide 2c shows a more pronounced (although still subtle) bowing of the helix, resulting in a 54 Å radius of curvature. This observation is consonant with our previous findings for a Puma-derived α/β-peptide that has an ααβαααβ backbone pattern analogous to that of 2c (60 Å radius of curvature, averaged over two independent molecules in the crystal structure).10b In contrast, α/β-peptide 4c forms a very straight helix when bound to Bcl-xL (148 Å radius of curvature, averaged over four independent molecules in the crystal structure).

Despite the minor deviations from canonical BH3 α-peptide interactions with pro-survival proteins manifested by the BH3-derived α/β-peptides in the two new structures, i.e., the C-terminal helix unwinding observed for 2c and the imperfect burial of the h3 side chain for 4c, both of the new structures show that these α/β-peptides form a network of contacts with Bcl-xL that mimics remarkably well those of the natural Bim BH3 domain. For 2c, which has the ααβαααβ backbone pattern, this finding is consistent with structural data previously reported for a Puma-derived α/β-peptide.10b The β3-residue placement in 2c locates the β-stripe along the helix circumference between the stripe of h1–h4 side chains and the crucial Asp side chain. For 4c, the mimicry of a natural BH3 domain is striking because the αααβ pattern causes the β3-residues to spiral around the helix axis, and in the case of 4c the h3 and h4 residues are derived from β3-amino acids.

Global analysis of α→β replacements

In the course of exploring various α→β replacement patterns, we have placed a β3-residue at each position of the Bim BH3 18-mer, and these replacements have occurred in different backbone contexts (i.e., different α/β patterns). We wondered whether global analysis of our set of α/β-peptide binding data might identify sequence positions at which α→β replacement is either particularly favorable or particularly unfavorable in terms of binding to either Bcl-xL or Mcl-1. Figure 6 provides a summary of binding results for each of the two protein targets, based on competition FP data. The α/β-peptides are grouped into two classes: weak binders and strong binders. The backbone pattern of each α/β-peptide is represented by a sequence of 18 blocks in which blue represents a β3-residue (for binding to Bcl-xL or Mcl-1, respectively), and white or green represents an α-residue.

Figure 6.

Global analysis of BH3-derived α/β-peptide binding to Bcl-xL (upper panel) or Mcl-1 (lower panel). The numbers across the top of each panel correspond to the sequence positions in the Bim-derived 18-mers introduced in this paper (Figure 1). Five positions characteristic of BH3 domains, four hydrophobic residues (h1–h4) and an Asp residue (D) are indicated. The leftmost column of each panel classifies the α/β-peptides as strong or weak binders to the relevant pro-survival protein. The next column identifies each α- or α/β-peptide, with number designations as in Figure 1. The remaining columns indicate whether the indicated position within the designated α/β-peptide is occupied by a β3-residue (blue box) or by an α-residue (white or green box). The green boxes highlight positions in strong binders that appear to require an α-residue to form a complex with Bcl-xL (upper panel) or with Mcl-1 (lower panel).

The clearest pattern to emerge from this analysis is seen among the strong binders. For each target protein, several among the 18 positions are never occupied by a β3-residue (green in Figure 6). For Bcl-xL, α→β replacement at positions 5, 8, 11, 12 and 15 does not seem to be allowed for strong binding, and for Mcl-1 replacement at positions 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12 and 15 seems to be unfavorable. Although there is considerable overlap among the non-allowed positions for the two proteins (positions 8, 11, 12 and 15), our analysis identifies sequence positions that could be useful for design of protein-specific α/β-peptides. In particular, Bcl-xL tolerates α→β replacement at position 3 (the h1 site), position 4 and position 7 (the h2 site) among strong-binding α/β-peptides, but Mcl-1 does not appear to tolerate β3-residues at these positions. On the other hand, Mcl-1 tolerates α→β replacement at position 5 among strong binders, but Bcl-xL does not. The pattern at h3 (position 10) is intriguing, because this position is occupied by a β3-residue in four of six α/β-peptides that bind strongly to Bcl-xL, while this position is an α-residue in all of the weak binders (of course, h3 is an α-residue in the Bim BH3 domain, which is a strong binder). In contrast, only one of strong binders to Mcl-1 has a β3-residue at the h3 position.

Rationalizing the pattern of α→β tolerance in structural terms is challenging because we have structural data for only two Bim-derived α/β-peptides bound to Bcl-xL and no structures for α/β-peptides bound to Mcl-1. The behavior at some positions can be tentatively tied to patterns that are broadly recognized among complexes between BH3 domains and pro-survival proteins. For example, position 12 corresponds to the highly conserved Asp that forms a salt bridge to the protein in many complexes (Figure 5),11 and perturbing the carboxylate position is likely to be detrimental. Position 11 is a small residue (Ala or Gly) in most BH3 domains, and this residue occupies a sterically constrained region of the binding groove of pro-survival proteins. It therefore seems likely that this position would be very sensitive to even minor perturbations that arise from α→β replacement. A similar argument would apply to substitutions at the h1 and h2 sites (positions 3 and 7),11,14 which are apparently not allowed among tight binders to Mcl-1. Bcl-xL, however, tolerates α→β replacements at these critical positions, which may reflect a higher degree of flexibility in the binding groove of Bcl-xL relative to Mcl-1.18 All α/β-peptides with α→β replacement at position 8 or 15 also have replacement at position 11 or 12; therefore, we cannot draw a firm conclusion about the intrinsic sensitivity of position 8 or 15 to replacement. Residues at these two positions are expected to be oriented toward solvent and not to engage in strong interactions with the partner protein; indeed, these positions in the Bim BH3 domain tolerate alanine mutations.14 Therefore, we suspect that in the context of a different β3-residue substitution pattern, positions 8 and 15 might ultimately prove to tolerate α→β replacement.

The trend at position 5 for binding to Bcl-xL (α→β replacement not allowed) is puzzling because this position is expected to be oriented toward solvent in the bound state. α/β-Peptide 4d illustrates this puzzle, since this molecule has a β3-residue at position 5 (but not at 8, 11, 12 or 15) and binds only weakly to Bcl-xL; however, 4d binds strongly to Mcl-1. It is possible that the effects of α→β replacements on protein binding are cumulative, at least in some cases, and that rationalization based on purely local factors (as suggested in the previous paragraphs) will not always be possible. Despite this caveat, the analysis that emerges from Figure 6 offers a useful framework for future exploration of positional α→β replacement tolerance within BH3 domain-derived α/β-peptides. In this regard, it is striking that a very similar pattern of α→β replacement tolerance emerges when a comparable analysis is applied to smaller set of previously reported Puma-derived α/β-peptides10a (see Supplementary Figure S6). Hence, it is possible that these trends provide general rules that could be applied to all BH3 sequence frameworks. Moreover, the similarity between trends among Puma- and Bim-derived α/β-peptides raises the intriguing possibility that particular binding profiles, either broad or selective among pro-survival proteins, could be achieved with irregular α→β replacement patterns.

Extension of selected α/β patterns to 26-mer length

Among Bim BH3-derived α-peptides, improvement in pro-survival protein binding profile is observed upon extension from 18-mer (1) to 26-mer (5).11 We therefore examined the 26-mer α/β-peptides that correspond to 2c and 4c, i.e., 6 and 7, respectively. In each case, the backbone pattern was maintained (ααβαααβ for 6; αααβ for 7), as was the native sequence of side chains (i.e., each β3-residue in 6 or 7 is the homologue of the native α-residue). The 26-residue Bim BH3 α-peptide 5 is known to bind tightly to all pro-survival Bcl-2 family proteins.14,16a In our competition FP assays, we observed Ki < 3 nM for 5 binding to both Bcl-xL and Mcl-1. We turned to competition surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements in order to compare 5 with 26-mer α/β-peptides 6 and 7 against a larger set of pro-survival proteins. The SPR data summarized in Table 1 show that 7 is the better of the two α/β-peptides in terms of reproducing the binding profile of the Bim BH3 domain (5). α/β-Peptide 7 shows comparable affinities for Bcl-2, Bcl-w, Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 relative to α-peptide 5. In contrast, α/β-peptide 6 displays substantially weaker binding to Bcl-2, Bcl-w and Bcl-xL relative to α/β-peptide 5, although 5 and 6 bind similarly to Mcl-1. SPR results are shown for 18-mers 2c and 4c for comparison with results for the 26-mers. Both 18-mers bind more weakly to each pro-survival protein than do the corresponding 26-mers (6 and 7, respectively). For Bcl-2, Bcl-w and Bcl-xL, 4c binds significantly more tightly than does 2c, in the SPR format.

Table 1.

SPR binding data for α-peptide 5 and α/β-peptides 6, 7, 2c, and 4c

| IC50 (nm) [SPR]a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | Bcl-xL | Bcl-2 | Bcl-w | Mcl-1 |

| 5 | 13 ± 4 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 9 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 34 ± 6 | 96 ± 1 | 41 ± 13 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| 7 | 7.5 ± 2 | 5.2 ± 1 | 7.5 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.3 |

| 2c | 1005 ± 25 | 4890 ± 370 | 620 ± 35 | 70 ± 7 |

| 4c | 21 ± 1 | 107 ± 8 | 29 ± 2 | 109 ± 1 |

Relative binding of α- and α/β-peptides to pro-survival proteins determined by competition assays using a Biacore instrument.

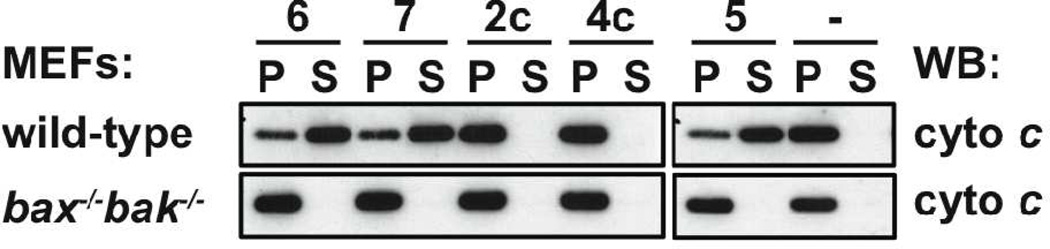

We used mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) extracts (produced by permeabilising the plasma membrane with digitonin, leaving the mitochondrial membranes unaffected) to determine whether α/β-peptides 6 and 7 can interact with the apoptosis signaling network; intact cells could not be employed in these studies because medium-length α/β-peptides typically do not cross membranes, as is also true for α-peptides of similar length. Wild type MEFs are protected from apoptosis by both Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL.20 The Bim BH3 peptide 5 can induce apoptotic signaling, as manifested by release of cytochrome c from mitochondria in the MEF extracts (Figure 7). This behavior is expected since α-peptide 5 binds tightly to both Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL, displacing pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax or Bak that initiate the cascade of events leading to cytochrome c release. α/β-Peptides 6 and 7 were observed to induce cytochrome c release in wild type MEF extracts (Figure 7), which is consistent with the SPR results showing tight binding to both Bcl-xL and Mcl-1. Importantly, no release was observed following treatment of MEFs derived from bax−/−/bak−/− mice, demonstrating that the activity of 6 and 7 in this assay depends on the expected signaling pathway. Neither of the18-mer α/β-peptides 2c or 4c induced cytochrome c release in MEF extracts, consistent with their relatively weak binding to Mcl-1 or Bcl-xL observed via SPR (Table 1).

Figure 7.

Cytochrome c release assay results. Permeabilised wild-type or bax−/−/bak−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were treated with 26-mer Bim BH3 α-peptide 5, homologous 26-mer α/β-peptide 6 or 7, or 18-mer α/β-peptide 2c or 4c. All three of the 26-mer oligomers cause cytochrome c release from the pellet fraction (P), which contains mitochondria, into the soluble (S) cytosolic fraction of wild-type MEFs. No release was observed with 18-mer α/β-peptide 2c or 4c, which is consistent with their weaker affinity for pro-survival proteins, relative to 26-mers 5–7. None of the peptides caused any cytochrome c release in bax−/−/bak−/− MEFs.

The use of unnatural oligomers to mimic signaling behavior of prototype α-peptides could be of therapeutic interest if the unnatural backbone resists biological degradation mechanisms. We used proteinase K to assess the susceptibility of α/β-peptides 6 and 7 to enzymatic cleavage. α-Peptide 5 is rapidly degraded under the conditions we employed (t1/2 ≤ 0.1 min; Table 2, as expected. α/β-Peptides 6 and 7 displayed ≥ 150-fold stabilization relative to 5 toward proteinase K degradation. This result is consistent with previous findings for oligomers with the ααβαααβ backbone.10a,12a The resistance of 7 is noteworthy because of the αααβ backbone pattern; 7 contains one fewer β3-residue than does 6.

Table 2.

Proteolysis α-peptide 5 and α/β-peptides 6 and 7

Half-life of α- and α/β-peptides (10 µM) in the presence of proteinase K (10 µg/mL) in pH 7.5 TBS with 5% DMSO. Remaining peptide was graphed versus time and fit to a simple exponential decay equation to obtain a half-life in GraphPad Prism4.

α-peptide 5 showed nearly complete degradation at the first time point (0.25 min); therefore, we provide an upper limit for the half-life.

We have previously shown that formation of an α-helix-like conformation by α/β-peptides leads to a CD signature with a single minimum, near 205 nm.8 A strong minimum in this region is observed for α/β-peptide 7, but not for 6. Variable-concentration CD analysis (Supporting Information) suggest that 7 may self-associate under these conditions, while 6 appears not to self-associate. It is interesting that α/β-peptides 6 and 7 show similar levels of resistance to proteinase K degradation despite the apparent differences in helix-forming and/or self-association propensity.

Conclusions

We have used Bim BH3 domain mimicry as a model system to conduct comprehensive evaluation of oligomers with alternative α/β3 arrangements. The most important outcome is our discovery that the αααβ pattern can provide functional mimicry of a signal-bearing α-helix while conferring significant resistance to proteolytic degradation. This finding expands the design horizon for α-helix-mimetic α/β-peptides, complementing previous work that highlighted the utility of the ααβαααβ pattern (this utility is reinforced by results provided here).8,10 Our observations show that it is not necessary to confine β-amino acid residues within an α/β-peptide sequence to regions of the helical surface that make little or no contact with the partner protein.

The signaling properties of some BH3 domains have been effectively mimicked with orally-bioavailable small molecules, which is a significant triumph in the realm of medicinal chemistry.6 However, this achievement does not provide a basis for extending α-helix mimicry to longer examples, encompassing more than four helical turns. In contrast, α/β-peptide design strategies are applicable to very long α-helical prototypes.10 The results reported here expand the range of α/β combinations to be considered when one undertakes to mimic an informational α-helix.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General

Protected α-amino acids, resins, and 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) were purchased from Novabiochem. Protected β3-homoamino acids were purchased from PepTech. 6-((4,4-difluoro-1,3-dimethyl-5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-2-propionyl)amino)hexanoic acid, succinimidyl ester (BODIPYTMR-X-SE) was purchased from Invitrogen. All other reagents and solvents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich or Fisher and used as received. Reverse-phase HPLC was carried out on Vydac analytical or preparative scale C18 columns using gradients between 0.1% TFA in water and 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile.

Peptide synthesis and purification

Peptides were synthesized using standard Fmoc-solid phase synthesis on Novasyn TGR resin or NovaPEG Rink amide resin. The primary synthesis of all peptides was performed in parallel in a fritted 96-well plate (Arctic white) at room temperature with a minimum coupling time of 1 h and deprotection time of 20 min. Microwave irradiation was used as previously described to repeat syntheses of selected α/β-peptides.8b Briefly, protected amino acids were activated with HBTU and N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) in the presence of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) in NMP for coupling reactions. Deprotections were effected using 20% piperidine in DMF. After the final deprotection, peptides were capped using acetic anhydride/DIEA in DMF. Peptides 1 and 5 were synthesized using an Applied Biosystems Synergy 432A automated peptide synthesizer as previously described.8b After synthesis was complete, peptides were cleaved from the resin using a solution of 95% TFA, 2.5% H2O, and 2.5% triisopropylsilane. Excess TFA was removed under a stream of nitrogen, and crude peptide was precipitated by addition of cold ether. Crude peptide solutions were purified using reverse-phase HPLC on preparative scale using C18 columns. The identity and purity of peptides were confirmed by MALDI-TOF-MS and analytical HPLC, respectively. After lyophilization, peptides were dissolved in DMSO, and concentration was determined by UV Spectroscopy, based on the fact that each peptide contains two Tyr side chains and one Trp side chain (ε280 =8250 cm−1 M−1).21 Fluorescently labeled peptides used as tracers in the competition and direct binding fluorescence polarization assays were synthesized as previously described.15

Protein expression and purification and binding measurements via FP

Expression and purification of Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 were performed as previously described.10a Fluorescence polarization (FP) assays were conducted at room temperature in 384-well, non-treated, black polystyrene plates (Costar). Competitive and direct binding FP assays were conducted as reported previously.10a Briefly, for Bcl-xL binding assays, the tracer used was the previously reported BODIPYTMR-Bak tracer (previously reported dissociation constant (Kd) = 2.5 nM; however, we have more recently observed Kd = 1.2 nM).10a For Mcl-1 binding assays, the tracer used was the previously reported Flu-Bim tracer (Kd = 1.4 nM).15 The Kd for tracer binding to pro-survival protein was re-measured with each new expression of protein and synthesis of tracer, and the resulting Kd value was used for calculation of inhibitor dissociation constant (Ki) values derived from that set of competition FP assays. Competition FP assays were conducted by adding 2 µL aliquots of serial dilutions of inhibitor in DMSO (final concentrations ranging from 4.2 pM to 25 µM) to 48 µL of tracer/protein mix in FP buffer (50 mM NaCl, 16.2 mM Na2HPO4, 3.8 mM KH2PO4, 0.15 mM NaN3, 0.15 mM EDTA, 0.5 mg/mL Pluoronic-F68, pH 7.5). For Bcl-xL binding assays, the final concentrations of BODIPYTMR-Bak tracer and Bcl-xL were 3 nM and 2 nM, respectively. For Mcl-1 binding assays, the final concentrations of Flu-Bim tracer and Mcl-1 were 10 nM each. Experiments were performed in duplicate. After a 5 h incubation time, plates were analyzed on an Envision 2100 plate reader. The Ki value for each inhibitor was calculated as previously described using GraphPad Prism.15

Binding measurements via SPR

Solution competition assays were performed using a Biacore 3000 instrument as described previously.18 Briefly, pro-survival proteins (10 nM) were incubated with varying concentrations of peptide for at least 2 h in running buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, 0.005% (v/v) Tween 20, pH 7.4) prior to injection onto a CM5 sensor chip on which either a wild-type BimBH3 peptide or an inert BimBH3 mutant peptide (Bim4E) was immobilized. Specific binding of the pro-survival protein to the surface in the presence and absence of competitor α- or α/β-peptides was quantified by subtracting the signal obtained on the Bim mutant channel from that obtained on the wild-type Bim channel. The ability of the peptides to prevent protein binding to immobilized BimBH3 was expressed as the IC50, calculated by nonlinear curve fitting of the data with Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software).

Cytochrome c release assay

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (wild-type, bax−/−/bak−/−) (~2 × 106 cells) were permeabilized in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 250 mM sucrose, 0.05% (w/v) digitonin (Calbiochem) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche), for 10 min on ice. The mitochondria-containing crude lysates were incubated with 10 µM peptide at 30° C for 1 h before pelleting. The supernatant was retained as the soluble fraction while the pellet, which contained intact mitochondria, was solubilized in 1% (v/v) Triton-X-100-containing lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-pH 7.4, 135 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Cytochrome c was detected with anti-cytochrome c antibody (7H8.2C12, BD Pharmingen).

Crystallization

We employed a “loop-deleted” form of human Bcl-xL (Δ27–82 and without membrane anchor), which forms an α1 domain-swapped dimer yet retains BH3 domain binding activity.17 Crystals were obtained by mixing Bcl-xL with the appropriate α/β-peptide at a molar ratio of 1:1.3 and then concentrating the sample to 10 mg/ml. Crystals were grown by the sitting drop method at room temperature in 1.5 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, 12% (v/v) glycerol for 2c or 25% (w/v) PEG 3350, 0.2 M lithium sulfate, 0.1 M Hepes pH 7.5 for 4c. Prior to cryo-cooling in liquid N2, crystals containing 4c were equilibrated into cryoprotectant consisting of reservoir solution containing increasing concentrations of ethylene glycol to a final concentration of 15%. Crystals containing 2c were mounted directly from the drop and plunge cooled in liquid N2.

Diffraction data collection and structure determination

Diffraction data were collected at the Australian Synchrotron MX2 beamline. The diffraction data were integrated and scaled with XDS.22 The structure was obtained by molecular replacement with PHASER23 using the structure of Bcl-xL from the Bim/Bcl-xL complex (PDB: 3FDL), with the Bim peptide removed, as a search model. Several rounds of building in COOT24 and refinement in PHENIX25 led to the final model.

Proteolysis

Stock solutions of each peptide were prepared in a TBS solution with 10% DMSO (for solubility) at 100 µM as determined by UV absorbance. A 25 µg/mL stock solution of proteinase K was prepared in TBS. For each proteolysis reaction, 25 µL of peptide stock solution was mixed with 15 µL TBS. A 10 µL aliquot of proteinase K stock solution was added to the mixture, and the reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature. A 100 µL aliquot of 1% TFA in 50:50 acetonitrile:H2O was added to quench the reaction at the desired time point. A 125 µL aliquot of the resulting solution was injected onto an analytical reverse phase HPLC column, and the amount of full-length peptide remaining was quantified using the absorbance at 220 nm of this peptide. Duplicate reactions were run for each time point. Half-life values were determined by plotting the percent remaining peptide versus time and fitting the data to an exponential decay using GraphPad Prism. Amide bond cleavage sites were identified by MALDI-MS analysis of crude reaction mixtures at various time points.

Circular Dichroism (CD)

All CD data were acquired using an Aviv 420 circular dichroism spectrophotometer. Peptide solutions were prepared in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, and the concentration was determined by UV absorbance. Data were acquired at 20°C with a step value of 1 nm from 260 to 190 nm and an averaging time of 5.0 sec. A 0.1 mm path length cell was used for all spectra. Signals were truncated to dynode voltages of < 400 V.

Supplementary Material

Figure 8.

Circular dichroism data for 26-mer Bim BH3 α-peptide 5 and homologous 26-mer α/β-peptides 6 and 7 (25 µM peptide in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research at UW-Madison was supported by NIH grant R01 GM-056414. W.S.H. was supported in part by an NIH fellowship (CA119875), and K.J.K. was supported in part by the Chemistry-Biology Interface Training Program (T32GM008505). In addition, this work was supported by fellowships and grants from Australian Research Council (Discovery Project Grant DP1093909 to W.D.F., P.M.C., B.J.S.), the NHMRC of Australia (Program Grant 461221 to P.M.C.), Australian Cancer Research Foundation (P.M.C.), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (SCOR 7015-02) and an Australian Postgraduate Award (to O.B.C.). Crystallization trials were performed at the Bio21 Collaborative Crystallisation Centre. Data were collected on the MX2 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, Victoria, Australia. Infrastructure support from NHMRC IRIISS grant #361646 and the Victorian State Government OIS grant is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supplementary tables 1–3, supplementary Figures 1–7, further details of peptide characterization. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Jochim AL, Arora PS. Mol. Biosyst. 2009;5:924. doi: 10.1039/b903202a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jochim AL, Arora PS. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:919. doi: 10.1021/cb1001747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Guarracino DA, Bullock BN, Arora PS. Biopolymers. 2011;95:1. doi: 10.1002/bip.21546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Guichard G, Huc I. Chem. Comm. 2011;47:5933. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (a) Goodman CM, Choi S, Shandler S, DeGrado WF. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:252. doi: 10.1038/nchembio876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hecht S, Huc I. Wenheim: Wiley-VCH; 2007. [Google Scholar]; (c) Schafmeister CE, Brown ZZ, Gupta S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1387. doi: 10.1021/ar700283y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Davis J, Tsou L, Hamilton A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;36:326. doi: 10.1039/b608043j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yin H, Hamilton AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2005;44:4130. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Werder M, Hauser H, Abele S, Seebach D. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1999;82:1774. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kritzer JA, Luedtke NW, Harker EA, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14584. doi: 10.1021/ja055050o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Stephens OM, Kim S, Welch BD, Hodsdon ME, Kay MS, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13126. doi: 10.1021/ja053444+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) English EP, Chumanov RS, Gellman SH, Compton TJ. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:2661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Hara T, Durell SR, Myers MC, Appella DH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1995. doi: 10.1021/ja056344c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hayashi R, Wang D, Hara T, Iera JA, Durell SR, Appella DH. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:7884. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Ernst JT, Kutzki O, Debnath AK, Jiang S, Lu H, Hamilton AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2002;41:278. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020118)41:2<278::aid-anie278>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kutzki O, Park HS, Ernst JT, Orner BP, Yin H, Hamilton AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11838. doi: 10.1021/ja026861k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ernst JT, Becerril J, Park HS, Yin H, Hamilton AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2003;42:535. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yin H, Lee GI, Sedey KA, Rodriguez JM, Wang HG, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5463. doi: 10.1021/ja0446404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yin H, Lee GI, Sedey KA, Kutzki O, Park HS, Orner BP, Ernst JT, Wang HG, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10191. doi: 10.1021/ja050122x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Ahn J-M, Han S-Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;28:5343. [Google Scholar]; (g) Hu X, Sun J, Wang H-G, Manetsch R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13820. doi: 10.1021/ja802683u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Shaginian A, Whitby LR, Hong S, Hwang I, Farooqi B, Searcey M, Chen J, Vogt PK, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5564. doi: 10.1021/ja810025g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Campbell F, Plante JP, Edwards TA, Warriner SL, Wilson A. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:2344. doi: 10.1039/c001164a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Lee JH, Zhang Q, Jo S, Chai SC, Oh M, Im W, Lu H, Lim H-S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:676. doi: 10.1021/ja108230s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, Carvajal D, Podlaski F, Filipovic Z, Kong N, Kammlott U, Lukacs C, Klein C, Fotohui N, Liu EA. Science. 2004;303:844. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oltersdorf T, et al. Nature. 2005;435:677. doi: 10.1038/nature03579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Arkin MR, Randal M, DeLano WL, Hyde J, Luong TN, Oslob JD, Raphael DR, Taylor L, Wang J, McDowell RS, Wells JA, Braisted AC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:1603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252756299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ding K, Lu Y, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Wang G, Qiu S, Shangary S, Gao W, Qin D, Stuckey J, Krajewski K, Roller PP, Wang S. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:3432. doi: 10.1021/jm051122a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Buhrlage SJ, Bates CA, Rowe SP, Minter AR, Brennan BB, Majmudar CY, Wemmer DE, Al-Hashimi H, Mapp AK. ACS Chem. Biol. 2009;4:335. doi: 10.1021/cb900028j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Fry DC. Biopolymers. 2006;84:535. doi: 10.1002/bip.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Lessene G, Czabotar PE, Colman PM. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:989. doi: 10.1038/nrd2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Walensky LD, Kung AL, Escher I, Malia TJ, Barbuto S, Wright RD, Wagner G, Verdine GL, Korsmeyer SJ. Science. 2004;305:1466. doi: 10.1126/science.1099191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang D, Liao W, Arora PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2005;44:6525. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang D, Lu M, Arora PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1879. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Henchey LK, Porter JR, Ghosh I, Arora PS. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:2104. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Moellering RE, Cornejo M, Davis TN, Del Bianco C, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Kung AL, Gilliland DG, Verdine GL, Bradner JE. Nature. 2009;462:182. doi: 10.1038/nature08543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Stewart ML, Fire E, Keating AE, Walensky AE. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:595. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bird GH, Madani N, Perry AF, Princiotto AM, Supko JG, He XY, Gavathiotis E, Sodroski JG, Walensky LD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002713107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Horne WS, Price JL, Keck JL, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4178. doi: 10.1021/ja070396f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Horne WS, Price JL, Gellman SH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Giuliano MW, Horne WS, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9860. doi: 10.1021/ja8099294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Price JL, Horne WS, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12378. doi: 10.1021/ja103543s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steer DL, Lew RA, Perlmutter P, Smith AI, Aguilar MI. Curr. Med. Chem. 2002;9:811. doi: 10.2174/0929867024606759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Horne WS, Boersma MD, Windsor MA, Gellman SH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2008;47:2853. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee EF, Smith BJ, Horne WS, Mayer KN, Evangelista M, Colman PM, Gellman SH, Fairlie WD. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:2025. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Sattler M, Liang H, Nettesheim D, Meadows RP, Harlan JE, Eberstadt M, Yoon HS, Shuker SB, Chang BS, Minn AJ, Thompson CB, Fesik SW. Science. 1997;275:983. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Petros AM, Nettesheim DG, Wang Y, Olejniczak ET, Meadows RP, Mack J, Swift K, Matayoshi ED, Zhang H, Thompson CB, Fesik SW. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2528. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Smits C, Czabotar PE, Hinds MG, Day CL. Structure. 2008;16:818. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu X, Dai S, Zhu Y, Marrack P, Kappler JW. Immunity. 2003;19:341. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Czabotar PE, Lee EF, van Delft MF, Day CL, Smith BJ, Huang DC, Fairlie WD, Hinds MG, Colman PM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701297104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Horne WS, Johnson LM, Ketas TJ, Klasse PJ, Lu M, Moore JP, Gellman SH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902663106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnson LM, Horne WS, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:10038. doi: 10.1021/ja203358t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbury PB, Zhang T, Kim PS, Alber T. Science. 1993;262:1401. doi: 10.1126/science.8248779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee EF, Czabotar PE, van Delft MF, Michalak EM, Boyle MJ, Willis SN, Puthalakath H, Bouillet P, Colman PM, Huang DC, Fairlie WD. J. Cell. Biol. 2008;180:341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boersma MD, Sadowsky JD, Tomita YA, Gellman SH. Protein Sci. 2008;17:1232. doi: 10.1110/ps.032896.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Chen L, Willis SN, Wei A, Smith BJ, Fletcher JI, Hinds MG, Colman PM, Day CL, Adams JM, Huang DC. Mol Cell. 2005;17:393. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Certo M, Del Gaizo Moore V, Nishino M, Wei G, Korsmeyer S, Armstrong SA, Letai A. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:351. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ku B, Liang C, Jung JU, Oh BH. Cell Res. 2011;21:627. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee EF, Sadowsky JD, Smith BJ, Czabotar PE, Peterson-Kaufman KJ, Colman PM, Gellman SH, Fairlie WD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:4318. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee EF, Czabotar PE, Yang H, Sleebs BE, Lessene G, Colman PM, Smith BJ, Fairlie WD. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:30508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.040725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelekar A, Thompson CB. Trends Cell. Biol. 1998;8:324. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willis SN, Chen L, Dewson G, Wei A, Naik E, Fletcher JI, Adams JM, Huang DC. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1294. doi: 10.1101/gad.1304105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabsch W. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2005;61:458. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Read RJ. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2001;57:1373. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Storoni LC, McCoy AJ, Read RJ. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:432. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.