Abstract

Background:

Newly diagnosed patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) are currently treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib, nilotinib or dasatinib. However, incomplete eradication of residual disease is a general problem of long-term TKI therapy. Activation of mouse haematopoietic stem cells by interferon-α (IFNα) stimulated the discussion of whether a combination treatment leads to accelerated eradication of the CML clone.

Methods:

We base our simulation approach on a mathematical model describing human CML as a competition phenomenon between normal and malignant cells. We amend this model to incorporate the description of IFNα activity and simulate different scenarios for potential treatment combinations.

Results:

We demonstrate that the overall sensitivity of CML stem cells to IFNα activation is a crucial determinant for the benefit of a potential combination therapy. We furthermore show that pulsed IFNα together with continuous TKI administration is the most promising strategy for a combination treatment in which the therapeutic benefit prevails adverse side effects.

Conclusion:

Our modelling approach is a highly beneficial tool to quantitatively address the competition between normal and leukaemic haematopoiesis in treated CML patients. We derive testable predictions for different experimental settings that are suggested before the clinical implementation of the combination treatment.

Keywords: CML, interferon-α, combination therapy, mathematical modelling

The clinical application of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib, nilotinib or dasatinib for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) had important implications not only for treatment success but also for the understanding of the pathomechanisms of the disease (Savage and Antman, 2002). Although treatment with imatinib could still not be demonstrated to be curative, it is suited to achieve a sustained control of the disease in the majority of patients. The 6-year overall survival rate achieved 88% and exceeds all other CML therapies (Hochhaus et al, 2009).

The TKI imatinib was one of the first cancer-specific drugs that proved efficient to specifically inhibit the action of the BCR–ABL oncoprotein. BCR–ABL is commonly expressed in cells with the so-called ‘Philadelphia chromosome’, a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 that is characteristic for CML cells. However, it appears that even after a massive reduction of the tumour load over many years of treatment (referred to as cytogenetic/molecular remission) a residual disease is retained in many patients (Goldman, 2009). Regularly, these patients show a rapid increase in cancer load if imatinib treatment is stopped (Michor et al, 2005). These observations lead to the hypothesis that at least some leukaemic stem cells are able to hide from the imatinib effect, for example, by entering an inactive, quiescent state (Komarova and Wodarz, 2007). Contrasting the above mentioned relapse kinetics, a sustained molecular remission after imatinib cessation is observed in a small number of patients (Rousselot et al, 2007; Mahon et al, 2010). These cases suggest that an eradication of the leukaemia is in principle possible and propose the view that CML stem cells are not always found in a treatment-protected (potentially quiescent) state but can be targeted over time.

These findings add to a long-standing discussion on whether TKIs affect CML stem cells or whether these particular cells are protected from the therapeutic effect (Michor et al, 2005; Glauche et al, 2007). Although it is regularly suggested that leukaemic cells treated with imatinib survive in a state of extended quiescence, the long-term treatment success in a number of patients is a strong argument in favour of an occasional activation of these cells, which makes them susceptible to the (cytotoxic) drug effect. Six-year follow-up data for patients under long-term imatinib treatment indicates that the majority of patients, which do not show resistance mutations against imatinib, remain in sustained molecular remission and show further declining BCR–ABL/ABL ratios (Hochhaus et al, 2009). These findings can only be explained under the assumption that the expansion of the leukaemic stem cell clone is stopped or even inverted, indicating that imatinib also acts on the level of stem cells. We advocate the view that imatinib preferentially targets activated, cycling stem and non-stem cells whereas only quiescent stem cells remain sheltered (Roeder et al, 2006). Assuming that normal haematopoiesis as well as the growth of the malignant CML clone is based on the reversible activation of preferentially quiescent stem cells, the cytotoxic effect of TKI imatinib on activated CML stem cells leads to a slow but sustained reduction of the CML clone. But, as documented in in vitro experiments (Druker et al, 1996; Graham et al, 2002), imatinib itself appears to induce prolonged quiescence among the CML stem cells and, therefore, make them less sensitive to cell-cycle-dependent drug effects. The persistence of residual CML cells in many patients is in good agreement with this assumption.

Others and we have previously raised the idea that a combination of TKIs with a cell-cycle-stimulating drug could potentially increase the efficacy of treatment (Jorgensen et al, 2006; Roeder et al, 2006; Drummond et al, 2009; Foo et al, 2009; Essers and Trumpp, 2010). This idea is based upon the assumption that the activating effect on CML stem cells makes them more susceptible to the cytotoxic effect of TKIs and leads to a faster reduction of the residual clone. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) has already been used in the clinic for the activation and mobilisation of human haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) into peripheral blood before stem cell extraction and appeared as a first candidate drug for a combination treatment alongside with imatinib (Jorgensen et al, 2006). However, a small clinical trial with cyclic administration of TKI imatinib and G-CSF did not show the expected results; in fact no clinical benefit of the combination treatment was observed (Drummond et al, 2009). However, both the choice of the stem cell-activating drug as well as the conducted cyclic treatment regimen might be critical determinants of the specific, nonbeneficial outcome. We will come back to these objections in the context of the analysis provided below.

Recently, we reported about the activating effect of interferon-α (IFNα) that directly acts on murine HSCs and induces increased cell-cycle activity (Essers et al, 2009). Although the findings were obtained in mice, these results again fostered the discussion on enhancing the TKI treatment in CML patients by cell-cycle-stimulating drugs (Essers and Trumpp, 2010). Before the introduction of TKI treatment, IFNα monotherapy was the standard therapy for patients with CML. Both the role of IFNα in innate and acquired immune responses as well as its anti-proliferative properties in many cell types in vitro made the drug a highly attractive therapy for the treatment of cancer (Borden et al, 2007). The novel findings on the stem cell-activating effects of IFNα add another aspect to this interpretation, suggesting an additional mechanism on the stem cell level that seems to differ from the immunological effect. Without necessarily focussing on the stem cell-activating effect of IFNα, a number of recently published studies hint towards an advantage of the combination therapy (Guilhot et al, 2009; Simonsson et al, 2011) but also demonstrate that severe side effects put a natural limit on treatment combinations (Cortes et al, 2010).

Owing to such heterogeneous results, our objective is to apply a comprehensive and validated, although simplifying, mathematical model of CML progression and therapy, which is suitable to address different treatment regimens in a systematic manner. The suggested model has been successfully used to describe the pathogenesis of CML and the sustained treatment response of patients under imatinib monotherapy. Within the amended model framework, we are able to study different possible pharmacological scenarios for the IFNα-mediated stem cell activation and predict long-term outcomes for different treatment regimens. The model represents a useful tool to identify promising and safe treatment combinations that could decrease potential side effects. Within the scope of this study, we address three different aspects of a possible combination treatment of TKIs and IFNα:

We investigate different possibilities of how a potentially quiescence-inducing effect of TKIs combines with the stem cell-activating effect of IFNα. Specifically, we consider three scenarios: (i) strong activation of leukaemic stem cells similar to normal HSCs, (ii) weak activation of leukaemic stem cells and (iii) no activation of leukaemic stem cells.

Furthermore, we study the possibility that the application of a cell-cycle-activating drug leads to an additional temporary reduction of the self-renewal ability of the affected cells. As we demonstrate below, the results in Essers et al (2009) suggest that the application of IFNα induces an impaired self-renewal ability of HSCs, potentially due to the stimulated proliferation and an alteration of the stem cell–niche interaction.

Finally, we address the question how these effects need to be combined in a temporal manner as we predict that the timing of administration is crucial for the clinical benefit. Therefore, we analyse three distinct temporal treatment regimens: (i) continuous TKI plus continuous application of IFNα as a cell-cycle-activating drug, (ii) continuous TKI plus pulsed application of IFNα and (iii) pulsed TKI plus pulsed application of IFNα.

The outlined, three-step analysis results in a matrix of possible outcome scenarios. Within this matrix, we identify the scenarios in which the combination of imatinib with a stem cell-activating drug such as IFNα appears beneficial for the clinical outcome and the reduction of the minimal residual disease. We will further discuss these results and suggest critical experiments that need to be carried out before a clinical implementation of the combination treatment.

Methods

Modelling normal haematopoiesis and CML

CML is perceived as a clonal competition phenomenon between normal haematopoietic and leukaemic stem cells. This concept has been translated into a single-cell-based model framework that was originally developed to describe murine and human haematopoiesis (Roeder and Loeffler, 2002; Roeder et al, 2005), and has been successfully applied to CML (Roeder et al, 2006; Horn et al, 2008). Owing to small differences in their cell-specific parameters, the leukaemic cells are able to outcompete the normal cells in a dynamic process, thus mimicking the clinically observed chronic phase in human CML.

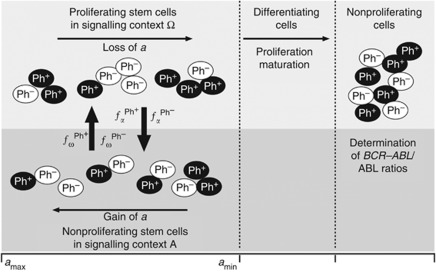

Technically, the mathematical model assumes that (both normal and leukaemic) stem cells reside in either of the two signalling contexts, named A and Ω, and that they can reversibly change between them (Figure 1). Importantly, the signalling contexts impose different effects on the cellular development: whereas context A is inspired by the concept of a stem cell-supporting niche and promotes cellular quiescence and regeneration, context Ω represents an escape of HSCs from the niche signals and promotes proliferation and differentiation. A cell’s tendency to switch from one context to the other is determined by the cell number in the target context (i.e., the ‘packing density’ given a certain niche-specific carrying capacity that is implemented by a specific sigmoid activation/deactivation function fα/ω) and by a cell-specific affinity a to reside in context A. The affinity a is gradually lost in context Ω, but regained in A up to the maximum value amax. Therefore, the system is able to establish a dynamically stabilised equilibrium, balancing quiescent cells in A and proliferating cells in Ω.

Figure 1.

Stem cell model. The model setup is characterised by two different signal contexts, A and Ω between which the cells can reversibly change depending on the cell number within the target context and the cell-specific affinity a (encoded in the transition functions fα/ω). Whereas activated cells in Ω undergo divisions and exponentially degrade their cell-specific affinity a, cells in A are quiescent and regain their affinity value. Cells with a>amin are referred to as stem cells, whereas cells with a<amin are referred to as differentiating cells. The differentiating cells undergo a proliferative phase before they mature without further division. Leukaemic cells (Ph+) have slightly altered transition kinetics between A and Ω. Model parameters are further adapted depending on the particular treatment scenario. BCR–ABL/ABL ratios are calculated based on the fraction of leukaemic cells in the pool of maturing cells.

If the cell-specific affinity a decreases below a certain threshold amin, the cell loses the ability to change back to context A, and is committed to undergo further proliferation and differentiation. Hence, the affinity a can be interpreted as a measure of the long-term repopulation potential of an individual cell. Accordingly, the residence in context A is necessary to prevent differentiation and, therefore, to maintain the HSC population. In this interpretation, self-renewal appears as a mechanistic consequence of the stem cells’ ability to attach to the niche-like environment and is functionally independent from their proliferative abilities.

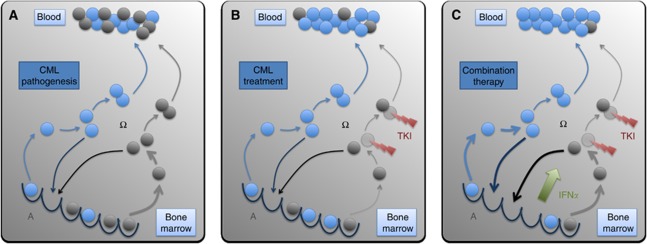

In order to explain the competitive advantage of leukaemic cells compared with normal HSCs, we assume that the leukaemic cells have an increased and unregulated proliferative activity (Figure 2A). Technically, the transition characteristics fα and fω, which describe the transit of cells between A and Ω, differ such that leukaemic cells have (I) an increased and cell number-independent probability per time step to be activated into cycle and (II) a slightly increased propensity to find an empty niche site, which is modelled by an altered probability to change to the niche-like signalling context A. Both assumptions are necessary to consistently explain characteristics of CML pathogenesis (Roeder et al, 2006; Horn et al, 2008). Further details of the implementation are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Figure 2.

CML pathogenesis and treatment. (A) Normal (blue) and leukaemic (grey) stem cells are regularly activated from their bone marrow niches (bottom, signalling context A) and subsequently divide (signalling context Ω). For the maintenance of a balance between quiescent and activated cells, some cells return to the niches and self-renew while others undergo further proliferation and differentiation, and contribute to peripheral blood. Owing to an increased activation of the leukaemic cells compared with normal cells the leukaemic pool slowly outcompetes normal haematopoiesis. (B) TKIs preferentially target activated leukaemic cells, thus leading to a significant reduction of tumour load. However, we also assume that leukaemic stem cells are even less likely to be activated under TKI treatment (indicated by the thinner arrows). Therefore, a residual pool of leukaemic cells persists over long time scales. (C) IFNα-mediated activation of both normal and leukaemic stem cells leads to a fast and sustained reduction of the residual leukaemic cells as these activated leukaemic (stem) cells are target for the primary TKI-mediated cell kill.

Tumour load in the peripheral blood is clinically measured in terms of BCR–ABL transcript levels. Within the mathematical model, BCR–ABL/ABL percentages are approximated using cell numbers in the population of fully differentiated cells according to the following equation:

in which n1 denotes the number of leukaemic cells and n2 the number of normal cells (Branford et al, 1999).

Modelling the TKI effect

Treatment of CML patients with TKI imatinib is assumed to induce (I) a cytotoxic effect and (II) inhibition of the proliferative activity of leukaemic stem cells (Figure 2B). Technically, the apoptotic effect (I) is modelled by a selective kill of a fixed percentage of leukaemic cells per time step (degradation rate rdeg), while the proliferation inhibition (II) is modelled by a reduction of the activation of leukaemic cells into cycle, that is, altering transition characteristic fω to a basal level (Supplementary Figure 1). The transition characteristic fω is assumed to remain unregulated, that is, independent of cell numbers in Ω. Thus, in our mathematical model imatinib therapy effects are described within a two-dimensional parameter space (rdeg, fω). It has been shown previously that these assumptions are sufficient to consistently explain CML emergence, genesis and treatment with TKI imatinib for a population of patients (Roeder et al, 2006; Horn et al, 2008). For a detailed parameter overview see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

In earlier applications of our model (Roeder et al, 2006), we assumed a gradual onset of the effect of TKI activity within the leukaemic stem cell population resulting in an optimal fitting of the short-term BCR–ABL/ABL response within the first 6 months after start of imatinib therapy. However, for the analysis of different treatment scenarios within the scope of this manuscript we use a simplified model version and suppose that all drugs act instantly and only as long as they are administered. Building on this simplification, we do not model the effect of single administrations of either TKI or IFNα but rather describe their cumulative effect within the bone marrow as a binary/on–off variable. It can be shown that model results on long-term kinetics of CML patients under TKI administration are not affected by these simplifications (Supplementary Figure 3).

Stem cell activation by IFNα

Although activation of HSCs with IFNα could so far only be shown in mice, we here explore whether and under which conditions a potentially similar effect in the human situation could improve TKI therapy of CML patients. In Essers et al (2009), it has been demonstrated that IFNα treatment (at time point 0) increases the fraction of dividing HSCs in a B6 mouse model within a 24 h interval from 20 up to 70%. In terms of the model, a similar effect is achieved under the assumption that about 3 to 4% of the stem cells are additionally activated from A into Ω during each simulation time step measuring 1 h (IFNα-mediated activation, for technical details see Supplementary Materials and Supplementary Figure 2).

Essers et al (2009) additionally showed that in a chimeric situation between wild-type and IFNα-receptor knockout cells the continuous administration of IFNα over the course of 3 weeks leads to a complete eradication of the wild-type clone. However, application of IFNα to wild-type mouse did not significantly influence peripheral blood cell counts and showed no long-term effect on the stem cell level after 3 weeks application. In terms of the model, this fast out-competition in the chimeric situation can only be explained under the assumption that IFNα (besides the stem cell activation) induces an additional defect in the cells ability to reattach to the niche-like signalling context A and, thus, to retain their self-renewal ability (IFNα-mediated self-renewal deficit (SRD)). However, for small stem cell numbers this effect is alleviated as the system aims to compensate a total loss of HSCs, which in turn can explain the stabilised haematopoiesis in the nonchimeric situation. As this secondary effect of the IFNα-mediated SRD has important consequences for therapy outcome, it is studied separately in the Results section.

Modelling the combination of effects

Although the IFNα effects on stem cells are only demonstrated in mice, we here make the assumption that IFNα acts similarly in humans (Figure 2C). Building on this working hypothesis, we provide a model description of the TKI effect on leukaemic cells and of a set of different potential IFNα effects on normal as well as on leukaemic cells. However, it is still speculative how these effects superimpose in the case of a combination therapy. To disentangle the superposition of effects in a systematic manner we study the system response in three dimensions:

We analyse the stem cell-activating effect of IFNα under the assumptions that IFNα activates normal HSCs and has no/weak/strong activating effect on CML stem cells. Technically, for the strong activation, 3% of the normal and leukaemic stem cells in context A are additionally activated into context Ω per simulation time step (1 h). For the weak activation, only 0.2% of the leukaemic stem cells are additionally activated while activation of the normal HSCs remains at 3%. In the case of no activation, the leukaemic stem cells are completely insensitive to IFNα-mediated activation. Additional, potentially immunological effects of IFNα are neglected for this study.

We analyse whether the additional IFNα-mediated SRD of normal and leukaemic cells changes the therapeutic prediction for the first dimension.

For the range of combinations in (1) and (2), we address whether the continuous or pulsed administration of the drugs appears both safe and clinically beneficial.

An overview about the different simulated scenarios is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of the simulation scenarios.

| Strong activation | Weak activation | No activation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cont. TKI and cont. IFNα | |||

| w/o SRD | Figure 3 (+) | Figure 3 (+) | Figure 3 (+) |

| with SRD | Figure 4 (+) | Figure 4 (!) | Figure 4 (−) |

| Cont. TKI and pulsed IFNα | |||

| w/o SRD | Figure 5 (+) | Figure 5 (+) | Figure 5 (+) |

| with SRD | Supp. Figure 4 (+) | Supp. Figure 4 (+) | Supp. Figure 4 (+) |

| Pulsed TKI and pulsed IFNα | |||

| w/o SRD | Figure 6A–C (−) | Figure 6D–F (!) | Figure 6G–I (!) |

| with SRD | Supp. Fig. 5A–C (−) | Supp. Fig. 5D–F (!) | Supp. Fig. 5G–I (!) |

| Pulsed TKI and cont. IFNα | |||

| w/o SRD | Supp. Figure 7 (−) | Supp. Figure 7 (−) | Supp. Figure 7 (−) |

| with SRD | Supp. Figure 6 (!) | Supp. Figure 6 (−) | Supp. Figure 6 (−) |

Abbreviations: cont.=continuous; IFNα=interferon-α, SRD=self-renewal deficit; Supp.=Supplementary; TKI=tyrosine kinase inhibitor. w/o (or with) SRD refers to the simulation scenarios in which the additional IFNα-mediated SRD of normal and leukaemic cells was taken into account (or not, respectively). Symbols in parentheses indicate whether the simulation scenarios predict beneficial or neutral treatment effects (+), therapy failure (−), or scenarios in which temporary, high values of BCR–ABL/ABL ratios have to be expected (!).

Technical implementation

The simulation model is implemented in C++. All simulation results shown are averages over 100 simulation runs with identical parameters. Averaging is required to represent a generalised behaviour as the model-inherent stochasticity induces small quantitative differences between different simulation runs, even if using identical parameter values. Further details as well as parameter specifications are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Results

Administration of TKI with a stem cell-activating drug

For the systematic investigation of a combination therapy for CML patients, we use an idealised ‘average patient’ under monotherapy with TKI imatinib as the standard reference. First-line response under imatinib leads to a rapid molecular response within the first year of treatment, but model simulations suggest that tumour eradication is only expected to occur after about 25 years of continuous treatment. However, the initial treatment effect of the TKI can hardly be enhanced. Therefore, we argue that a combination therapy with IFNα, aiming at the accelerated eradication of the residual pool of leukaemic stem cells, appears most advisable after 9 to 12 months of initial, successful imatinib therapy. This corresponds to the time frame in which the decline of BCR–ABL/ABL ratios changes from the rapid initial reduction towards the slower long-term decline.

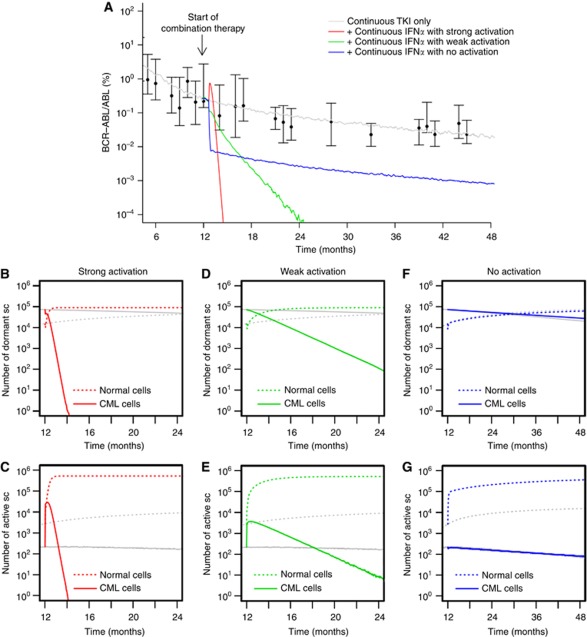

Under the assumption that continuous administration of IFNα induces an activation of both normal and leukaemic stem cells, the selective cytotoxic effect of TKI imatinib on leukaemic cells leads to a fast eradication of the malignant clone (Figure 3A). In fact, the continuous administration of both TKI imatinib and IFNα leads to a new constellation among the stem cell population (Figure 3B and C) with an increased number of activated stem cells as compared with the quiescent ones (owing to the stem cell-activating effect of IFNα). Under these novel conditions, the leukaemic clone has a competitive disadvantage as it is primarily targeted by the cytotoxic TKI effect. The intensity of the activation of leukaemic cells (i.e., whether it is comparable to the activation of normal cells or gradually weaker) only influences the speed of eradication but does not change the outcome qualitatively (compare the red and green curves in Figure 3A–E). However, if the activation only affects normal HSCs but not the leukaemic cells, the therapeutic benefit is lost (blue line in Figure 3A). In fact, the model predicts reduced BCR–ABL/ABL ratios in the peripheral blood, while the dynamics on the stem cell level only show an increased number of activated normal stem cells. Although normal cells undergo repeated activation (Figure 3G; and thus have an increased contribution to peripheral blood) these cells do also regularly re-enter the niche-like environment A (Figure 3F), thus keeping the overall ratio between normal and leukaemic stem cells at levels similar to TKI monotherapy (indicated by the slow decline in Figure 3A, parallel to the grey curve).

Figure 3.

Continuous TKI plus continuous IFNα. (A) Shown are different response scenarios on the level of BCR–ABL/ABL ratios in peripheral blood: strong activation of leukaemic stem cells similar to normal HSCs (red), weak activation (green) and no activation of leukaemic cells (blue, only normal cells are activated by IFNα). Patient data (black) from the German cohort of the IRIS study (Hochhaus et al, 2009; Roeder et al, 2006) and simulation results for monotherapy with TKI imatinib (grey) are provided for reference. Subfigures (B–G) show corresponding stem cell number in A (quiescent) and Ω (activated), compared with TKI monotherapy (grey) for strong (B, C), weak (D, E), and no activation scenarios (F, G).

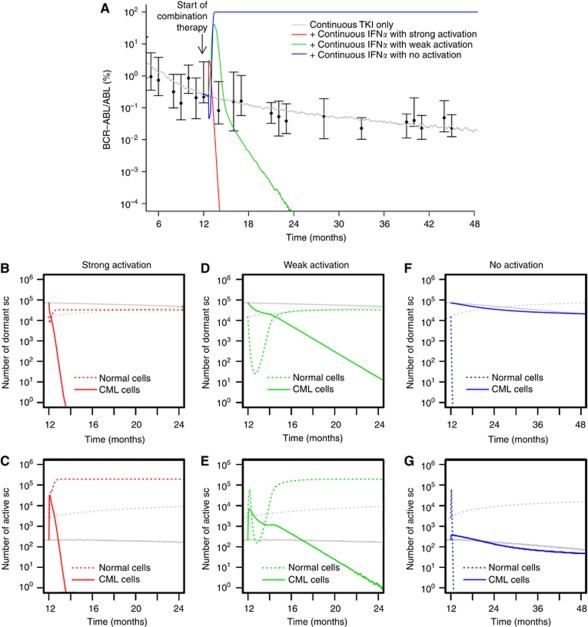

Stem cell activation with SRD

For the case that IFNα also induces a SRD in the affected stem cells, it makes a difference whether normal and leukaemic stem cells are activated equally. For the simplest scenario that both cell types are activated equally into the cell cycle due to IFNα administration (and have an equal SRD induced by the drug), the cytotoxic TKI effect on leukaemic cells influences the clonal composition in favour of the normal cells. The dynamics of this process are similar to the above scenario without the SRD (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Continuous TKI plus continuous IFNα with SRD. (A) BCR–ABL/ABL ratios in peripheral blood are shown for strong activation of leukaemic stem cells similar to normal HSCs (red), weak activation (green) and no activation of leukaemic cells (blue). However, in contrast to Figure 3, we assume that IFNα induces an additional SRD among normal and leukaemic cells. Subfigures (B–G) show corresponding stem cell numbers in A (quiescent) and Ω (activated), compared with monotherapy with TKI imatinib (grey) for strong (B, C), weak (D, E), and no activation scenarios (F, G).

The dynamics of tumour reduction are delayed for the scenario in which leukaemic cells are only weakly activated by IFNα compared with normal HSCs. Figure 4A indicates that only after a massive initial increase of leukaemic cells in the peripheral blood the combination treatment results in a beneficial therapeutic effect.

The picture changes drastically for the case that the stem cell-activating effect acts only on normal cells but spares the leukaemic cells. In this scenario, the leukaemic stem cell pool is preserved but the normal cells are repeatedly activated. Owing to their SRD, the normal cells are rapidly diluted (Figure 4F and G), which is indicated by the fast increase in BCR–ABL/ABL ratios, corresponding to immediate therapy failure (Figure 4A). In this scenario, the beneficial effect of the TKI treatment specifically acting on leukaemic stem cells is neutralised by the selective activation of normal HSCs by IFNα that spares the leukaemic cells and induces an additional binding deficit of the normal cells.

Influence of the treatment regimen

Severe side effects of a continuous combination therapy with imatinib and IFNα raise the question whether a treatment benefit can still be achieved by a scheduled and discontinuous administration of the drugs. From a clinical point of view, two general strategies for a pulsed treatment regimen need to be distinguished: (1) continuous TKI plus pulsed application of IFNα, and (2) pulsed TKI plus pulsed IFNα. Both regimens are studied in more detail below. The hypothetical, third option (continuous IFNα plus pulsed TKI) is clinically not relevant as it places IFNα as primary therapy instead of the TKI. However, our model predicts no therapeutic benefit in the majority of cases (Supplementary Figure 6 and 7).

Continuous TKI plus pulsed IFNα

As a general case, we study the scenario that IFNα is administered once every second week while TKI treatment continues without interruption. The overall outcome is closely similar to the above scenario of the continuous administration of both drugs with slower therapeutic benefit: For the case that both leukaemic and normal stem cells are equally activated by IFNα, the malignant clone declines but can only be eradicated after about 3 years past initial therapy start (Figure 5A). This overall trend is superimposed by an oscillation resulting from the pulsed administration of IFNα, which is also distinctly visible on the level of stem cells (Figure 5B–G). This oscillation is most likely less pronounced in a clinical setting as oscillations on the stem cell level would be compensated and/or washed-out at later cell stages of blood differentiation. It should also be kept in mind that if blood samples of patients are drawn at a rhythm that coincides with the pulsed therapeutic regimen, the results can be severely biased as potential treatment-induced oscillations might not be detected owing to a confounding of the treatment effect and the measurement frequency.

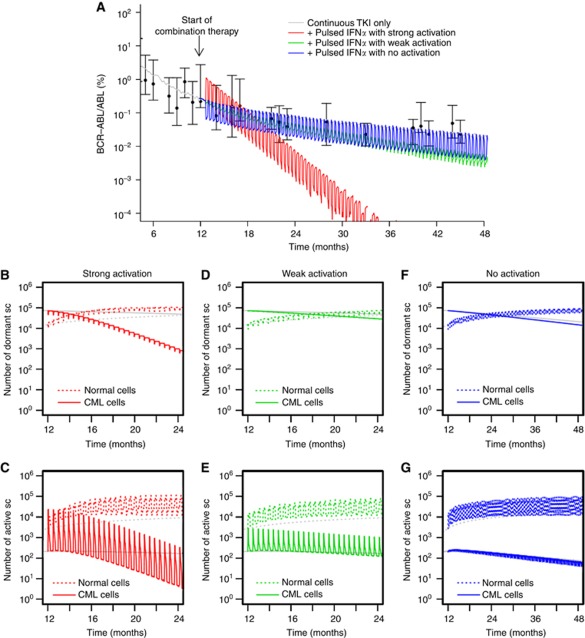

Figure 5.

Continuous TKI plus pulsed IFNα. (A) BCR–ABL/ABL ratios in peripheral blood are shown for pulsed application of IFNα (1 day within 14 days) for different activation scenarios: strong activation of leukaemic stem cells similar to normal HSCs (red), weak activation (green) and no activation of leukaemic cells (blue, only normal cells are activated by IFNα). For the corresponding simulations we do not include the additional, IFNα-induced SRD. However, the simulation results only change marginally if the effect is taken into account (Supplementary Figure 4). Subfigures (B–G) show corresponding stem cell numbers in A (quiescent) and Ω (activated), compared with monotherapy with TKI imatinib (grey) for strong (B, C), weak (D, E), and no activation scenarios (F, G).

For weaker activation of the leukaemic cells, the overall decline of tumour load is even further slowed down (Figure 5A). Again, for the case that IFNα does not activate leukaemic stem cells there is no therapeutical benefit, as the ratio between normal and leukaemic stem cells remains largely untouched, also resulting in similar dynamics on the stem cell level (Figure 5F and G).

Surprisingly, under the assumption that IFNα induces an additional SRD among both the normal and leukaemic cells, therapy failure is not observed as for the scenario described above in which only normal HSCs are activated while leukaemic ones are not. In the pulsed scenario, the time interval between successive IFNα administrations is sufficient for the system to stabilise the pool of normal cells instead of its rapid dilution. The same, close correspondence between the scenarios with and without SRD applies in the cases of strong and weak activation of the leukaemic clone (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure 4).

Pulsed TKI plus pulsed IFNα

For the case that both TKI and IFNα are applied in a pulsed fashion, the overall therapeutic outcome changes significantly. As a representative example, we study the case in which the TKI is administered continuously for 2 weeks and then suspended. After 1 day of IFNα administration (without parallel TKI application), the TKI therapy starts again after a time shift of 6 days (Figure 6A).

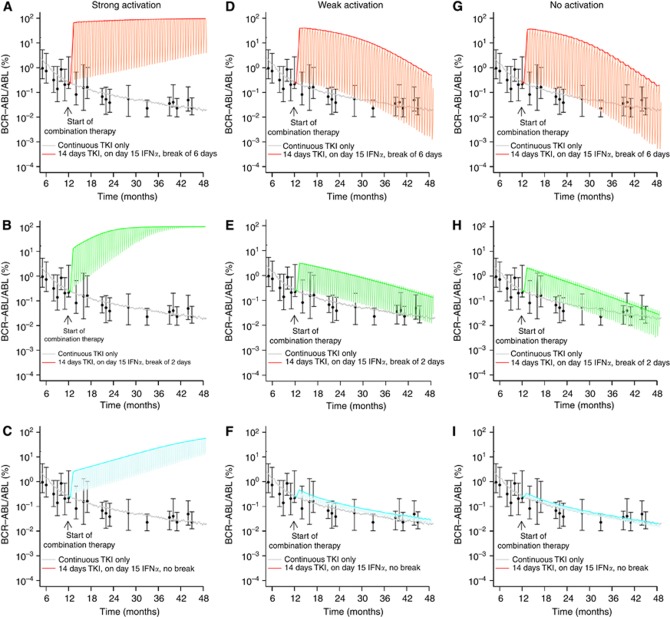

Figure 6.

Pulsed TKI plus pulsed IFNα. We show predicted BCR–ABL/ABL ratios in peripheral blood for the following representative treatment cycles: pulsed application of the TKI (day 1 to 14, no IFNα), pulsed application of only IFNα (day 15, no TKI), treatment interruption of x subsequent days past day 15 for different durations of the treatment interruption x: x=6 days (A, D, G, shown in red), x=2 days (B,E, H, shown in green) and x=0 days (C, F, I, shown in blue). Subfigures A–C correspond to the scenarios with strong activation of leukaemic stem cells by IFNα, subfigures D–F to the weak activation and subfigures G–I to the scenario in which leukaemic stem cells are not activated by IFNα. Thick curves correspond to smoothed values of the maximal BCR–ABL/ABL ratios, whereas the thin lines indicate the expected oscillations due to the cyclic treatment regimen.

Apparently, the pulsed treatment regimens induce a cyclic behaviour in the BCR–ABL/ABL ratios. However, as our model does not include any regulation of cellular output on the level of later cell stages, such as precursors, this effect might be overestimated. Nevertheless, our simulation results indicate that a treatment interruption of TKI after the administration of IFNα is not beneficial for the therapeutic outcome and might in fact counteract the strategy of the combination treatment. Even though our model does not appropriately reflect the pharmacokinetics of the drugs (i.e., the model does not account for the sustained presence of the drugs post administration), the simulations show in principle that no clinical benefit is obtained if the action of the two drugs does not superimpose at any given point of time.

For the scenarios in which we assume that IFNα activates both leukaemic stem cells and normal HSCs similarly (strong activation, Figure 6A–C), we observe a regrowth of the leukaemic clone. In these cases, the increased potential of the leukaemic cells to reoccupy empty niches after the activation cycle turns into a competitive advantage that overcompensates the TKI-mediated therapeutical benefit. Shortening the treatment interruption of the TKI increases the time to therapy failure as the cytotoxic effect on leukaemic cells is more pronounced in a phase where the cells are still activated.

For the other scenarios in which leukaemic stem cells are only weakly, or not at all, activated by IFNα there is no additional benefit of the combination therapy (Figure 6D–I). Although the pulsed application induces a typical fluctuation pattern, the balance between leukaemic stem cells and normal HSCs is not effectively changed. In the limit of shorter breaks between IFNα application and the next TKI treatment cycle, the BCR–ABL/ABL ratios converge towards the results of TKI monotherapy (Figure 6F and I).

Compared with the results in Figure 5, in which pulsed doses of IFNα are administered simultaneously with the continuous TKI application, none of the results for the pulsed/pulsed therapy in Figure 6 shows a superior behaviour. Therefore, we argue that a clinical benefit from potential IFNα-mediated stem cell activation can only be achieved for the case that TKI and IFNα are both pharmacologically active in an overlapping time interval.

Simulation results for the pulsed/pulsed application scenario in Figure 6 are obtained under the assumption that IFNα does not induce an additional SRD. However, taking this effect into account yields qualitatively similar results (Supplementary Figure 5).

Conclusion

We presented a novel mathematical model analysis to describe the combined effects of TKI such as imatinib and the cell-cycle-activating drug IFNα for the treatment of human CML. The model approach allowed us to study a variety of different pharmacological combination effects between TKIs and IFNα as well as different treatment regimens and to gain a systematic understanding of the combination therapy with the ultimate goal to guide clinical applications.

Summarising our model suggests that a successful combination therapy of TKIs with IFNα in CML patients requires the simultaneous application of both drugs in overlapping time intervals. In addition, a less-frequent application of IFNα reduces the speed of eradication but might also prevent a possible exhaustion of normal haematopoiesis. We showed that such adverse behaviour is possible for the case that IFNα does not activate leukaemic stem cells but induces a SRD among normal cells (cf. Figure 4). Furthermore, it has been documented that combination of TKI imatinib with IFNα imposes severe side effects on the patients (Cortes et al, 2010). Our findings indicate that a less-frequent administration of IFNα, which could decrease potential side effects of the combination therapy, is still helpful even though the time to eradication is predicted to increase. We demonstrated that a weekly or biweekly administration of IFNα under optimal conditions still shows a significant advantage compared with imatinib monotherapy and can reduce time to tumour eradication from ∼25 years to 3 years. Even in a less-favourable situation (i.e., IFNα does not induce activation of leukaemic stem cells), a pulsed IFNα therapy under continuing TKI administration shows no adverse effects compared with standard TKI monotherapy. These findings support recent clinical results that argue in favour of lower doses/longer cycles of IFNα administration in combination therapies to reduce severe side effects, but retaining the curative intent (Simonsson et al, 2011).

It remains speculative how the pharmacological effects of IFNα and TKIs act together on the level of HSCs in general and on leukaemic stem cells in particular. However, as shown by our simulation study, it is the combination of effects (whether they are, e.g., independent from each other or mutually compensating) as well as the translation into the human system that determine the possible clinical benefit. We demonstrated that especially the level of activation of the leukaemic stem cells is a major determinant of the speed of tumour eradication. For the continuous application of TKIs and IFNα, our model predicts therapy failure in cases in which leukaemic stem cells (but not normal HSCs) are completely insensitive to the activating effect of IFNα. A similarly critical situation is observed if both TKI and IFNα are administered in a pulsed, but sequential, fashion, which does not allow for a simultaneous pharmacological effect of both drugs. In these cases, a strong activation of leukaemic stem cells compared with normal HSCs induces a competitive advantage of the leukaemic clone and results in therapy failure. As we are not aware of any reports that suggest a correlation between IFNα administration and rapid leukaemic relapse, we consider this as an indirect evidence that CML stem cells are at least partially sensitive to IFNα.

It has been repeatedly discussed that the occurrence of secondary mutations in CML stem cells alters their responsiveness to TKIs and induces therapy failure (La Rosee and Deininger, 2010). Although it is not yet resolved whether such critical secondary mutations already pre-exist in the leukaemic clone before initial treatment or whether they are generated under TKI therapy (Sorel et al, 2004; Komarova and Wodarz, 2005; Jiang et al, 2007), it is sensible to assume that increased cell proliferation due to IFNα administration increases the risk for such unfavourable alterations. However, a quantification of this risk is nontrivial and beyond the scope of this publication. We argue that lower doses/longer cycles of IFNα administration in combination with TKI treatment appear as the favourable option, which should also minimise the risk for secondary mutations.

The presented model accounts for clonal behaviour of CML in the untreated and treated situation but it does not correctly represent the pharmacokinetic residence times of the administered drugs. Unlike in earlier applications of our model (e.g., in Roeder et al, 2006 in which we assumed a decelerated effect on the leukaemic stem cell population with a better fitting of the short-term BCR–ABL/ABL response after start of imatinib therapy), we made the simplifying assumption that all drugs act instantly and only as long as they are administered. Especially in the case of pegylated IFNα these assumptions do not hold. However, to account for the temporal extension of the drug activity, we model drug application as a temporal process extending over at least 24 h instead of modelling single-application events with sophisticated pharmacokinetics. Under these limitations, our general conclusion holds true that a therapeutic benefit is only achieved if IFNα is at any time supported by the immediate presence of the selective cytotoxic effect on the activated leukaemic cells.

Second-generation TKIs (like dasatinib or nilotinib) show increased efficiency against CML and currently replace imatinib as a first-line therapy (Kantarjian et al, 2010; Saglio et al, 2010). However, as the mechanism of action of these drugs, namely the inhibition of BCR–ABL tyrosine kinase and the resulting, targeted cytotoxic effect on leukaemic cells, are reportedly very similar to imatinib (Sawyers, 2010), our modelling results will in principle also apply for the situation that imatinib is replaced by a second-generation TKI.

The situation is different for alternative drugs that are regularly used to activate HSCs. Some of these drugs, like HU or 5-FU, induce a strong cytotoxic effect on proliferating cells while others, like G-CSF and AMD3100, lead to a mobilisation of HSCs from the bone marrow into the peripheral blood. Owing to these differences in their modes of action, the adaptation of the simulation results for IFNα to these alternative drugs would require a more detailed understanding of the drug effects on the stem cell level. Furthermore, we have restricted our model analysis of IFNα to the experimentally described activation of HSCs (Essers et al, 2009), thus intentionally neglecting additional immunological effects, which might also show a therapeutical benefit for the treatment of leukaemia patients.

Summarising our findings, we argue that before a clinical implementation of a combination therapy it is necessary to experimentally verify whether (1) IFNα leads to a similar activation of human HSCs as in mice, (2) CML stem cells are also activated by IFNα and (3) how this activation changes under the additional administration of a TKI. Appropriate experimental models in the mouse, such as xenografts with human HSCs and CML cells, are valuable systems for studying the drug combinations. However, especially the IFNα-dependent activation of both normal and leukaemic cells might require the correct environmental context, which is only given in the human situation. Simulation approaches, as the one presented here, are important tools to direct and justify the necessary experimental and clinical research that is currently pursued by our collaborators and us.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andreas Hochhaus for discussions and critical comments on our manuscript. This research was supported by the European Commission project EuroSyStem (200 270), by the German Research Council (DFG), grant RO3500/1-2, and by the German Ministry for Education and Research, BMBF-grant on Medical Systems Biology ‘HaematoSys’ (BMBF-FKZ 0315452). KH was partly funded by the Leipzig Interdisciplinary Research Cluster of Genetic Factors, Clinical Phenotypes, and Environment (LIFE Centre, Universität Leipzig). LIFE is funded by means of the European Union, by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Social Fund (ESF) and by means of the Free State of Saxony within the framework of its excellence initiative. ME and AT are supported by the Dietmar Hopp Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Borden EC, Sen GC, Uze G, Silverman RH, Ransohoff RM, Foster GR, Stark GR (2007) Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6(12): 975–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branford S, Hughes TP, Rudzki Z (1999) Monitoring chronic myeloid leukaemia therapy by real-time quantitative PCR in blood is a reliable alternative to bone marrow cytogenetics. Br J Haematol 107(3): 587–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes J, Quintas-Cardama A, Jones D, Ravandi F, Garcia-Manero G, Verstovsek S, Koller C, Hiteshew J, Shan J, O'Brien S, Kantarjian H (2010) Immune modulation of minimal residual disease in early chronic phase chronic myelogenous leukemia: a randomized trial of frontline high-dose imatinib mesylate with or without pegylated interferon alpha-2b and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Cancer 117(3): 572–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker BJ, Tamura S, Buchdunger E, Ohno S, Segal GM, Fanning S, Zimmermann J, Lydon NB (1996) Effects of a selective inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase on the growth of Bcr-Abl positive cells. Nat Med 2(6): 561–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond MW, Heaney N, Kaeda J, Nicolini FE, Clark RE, Wilson G, Shepherd P, Tighe J, McLintock L, Hughes T, Holyoake TL (2009) A pilot study of continuous imatinib vs pulsed imatinib with or without G-CSF in CML patients who have achieved a complete cytogenetic response. Leukemia 23(6): 1199–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers MA, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA, Trumpp A (2009) IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature 458(7240): 904–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essers MA, Trumpp A (2010) Targeting leukemic stem cells by breaking their dormancy. Mol Oncol 4(5): 443–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo J, Drummond MW, Clarkson B, Holyoake T, Michor F (2009) Eradication of chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells: a novel mathematical model predicts no therapeutic benefit of adding G-CSF to imatinib. PLoS Comput Biol 5(9): e1000503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauche I, Horn M, Roeder I (2007) Leukaemia stem cells: hit or miss? Br J Cancer 96(4): 677–678; author reply 679–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman JM (2009) Treatment strategies for CML. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 22(3): 303–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham SM, Jorgensen HG, Allan E, Pearson C, Alcorn MJ, Richmond L, Holyoake TL (2002) Primitive, quiescent, Philadelphia-positive stem cells from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia are insensitive to STI571 in vitro. Blood 99(1): 319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilhot F, Preudhomme C, Guilhot J, Mahon F-X, Nicolini FE, Rigual-Huguet F, Legros L, Guerci A, Rea D, Coiteux V, Maloisel F, Gardembas M, Bulabois C-E, Berger MG (2009) Significant higher rates of undetectable molecular residual disease and molecular responses with pegylated form of interferon a2a in combination with imatinib (IM) for the treatment of newly diagnosed chronic phase (CP) chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) patients (pts): confirmatory results at 18 months of part 1 of the spirit phase III randomized trial of the french CML group (FI LMC). ASH Annu Meeting Abstracts 114(22): 340 [Google Scholar]

- Hochhaus A, O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Druker BJ, Branford S, Foroni L, Goldman JM, Muller MC, Radich JP, Rudoltz M, Mone M, Gathmann I, Hughes TP, Larson RA (2009) Six-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 23(6): 1054–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn M, Loeffler M, Roeder I (2008) Mathematical modeling of genesis and treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Cells Tissues Organs 188(1–2): 236–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Saw KM, Eaves A, Eaves C (2007) Instability of BCR-ABL gene in primary and cultured chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 99(9): 680–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen HG, Copland M, Allan EK, Jiang X, Eaves A, Eaves C, Holyoake TL (2006) Intermittent exposure of primitive quiescent chronic myeloid leukemia cells to granulocyte-colony stimulating factor in vitro promotes their elimination by imatinib mesylate. Clin Cancer Res 12(2): 626–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, Cortes J, Shah S, Ayala M, Moiraghi B, Shen Z, Mayer J, Pasquini R, Nakamae H, Huguet F, Boque C, Chuah C, Bleickardt E, Bradley-Garelik MB, Zhu C, Szatrowski T, Shapiro D, Baccarani M (2010) Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 362(24): 2260–2270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova NL, Wodarz D (2005) Drug resistance in cancer: principles of emergence and prevention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(27): 9714–9719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova NL, Wodarz D (2007) Effect of cellular quiescence on the success of targeted CML therapy. PLoS One 2(10): e990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosee P, Deininger MW (2010) Resistance to imatinib: mutations and beyond. Semin Hematol 47(4): 335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon FX, Rea D, Guilhot J, Guilhot F, Huguet F, Nicolini F, Legros L, Charbonnier A, Guerci A, Varet B, Etienne G, Reiffers J, Rousselot P (2010) Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol 11(11): 1029–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michor F, Hughes TP, Iwasa Y, Branford S, Shah NP, Sawyers CL, Nowak MA (2005) Dynamics of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature 435(7046): 1267–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder I, Horn M, Glauche I, Hochhaus A, Mueller MC, Loeffler M (2006) Dynamic modeling of imatinib-treated chronic myeloid leukemia: functional insights and clinical implications. Nat Med 12(10): 1181–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder I, Kamminga LM, Braesel K, Dontje B, Haan Gd, Loeffler M (2005) Competitive clonal hematopoiesis in mouse chimeras explained by a stochastic model of stem cell organization. Blood 105(2): 609–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder I, Loeffler M (2002) A novel dynamic model of hematopoietic stem cell organization based on the concept of within-tissue plasticity. Exp Hematol 30(8): 853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousselot P, Huguet F, Rea D, Legros L, Cayuela JM, Maarek O, Blanchet O, Marit G, Gluckman E, Reiffers J, Gardembas M, Mahon FX (2007) Imatinib mesylate discontinuation in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in complete molecular remission for more than 2 years. Blood 109(1): 58–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, le Coutre P, Etienne G, Lobo C, Pasquini R, Clark RE, Hochhaus A, Hughes TP, Gallagher N, Hoenekopp A, Dong M, Haque A, Larson RA, Kantarjian HM (2010) Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 362(24): 2251–2259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DG, Antman KH (2002) Imatinib mesylate--a new oral targeted therapy. N Engl J Med 346(9): 683–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyers CL (2010) Even better kinase inhibitors for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 362(24): 2314–2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsson B, Gedde-Dahl T, Markevarn B, Remes K, Stentoft J, Almqvist A, Bjoreman M, Flogegard M, Koskenveesa P, Lindblom A, Malm C, Mustjoki S, Myhr-Eriksson K, Ohm L, Rasanen A, Sinisalo M, Sjalander A, Stromberg U, Weiss Bjerrum O, Ehrencrona H, Gruber F, Kairisto V, Olsson K, Sandin F, Nagler A, Lanng Nielsen J, Hjorth-Hansen H, Porkka K (2011) Combination of pegylated interferon-{alpha}2b with imatinib increases molecular response rates in patients with low or intermediate risk chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 118: 3228–3235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorel N, Bonnet ML, Guillier M, Guilhot F, Brizard A, Turhan AG (2004) Evidence of ABL-kinase domain mutations in highly purified primitive stem cell populations of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 323(3): 728–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.