Abstract

Objective:

South Africa has high rates of traumatic experiences and alcohol abuse or dependence, especially among women. Traumatic experiences often result in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and PTSD has been associated with hazardous drinking. This article examines the relationship between traumatic events and hazardous drinking among women who patronized alcohol-serving venues in South Africa and examines PTSD as a mediator of this relationship.

Method:

A total of 560 women were recruited from a Cape Town township. They completed a computerized assessment that included alcohol consumption, history of traumatic events, and PTSD symptoms. Mediation analysis examined whether PTSD symptoms mediated the relationship between the number of traumatic event categories experienced (range: 0–7) and drinking behavior.

Results:

The mean Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test score in the sample was 12.15 (range: 0–34, SD = 7.3), with 70.9% reaching criteria for hazardous drinking (AUDIT ≥ 8). The mean PTSD score was 36.32 (range: 17–85, SD = 16.3), with 20.9% meeting symptom criteria for PTSD (PTSD Checklist with 20.9% meeting symptom criteria for PTSD (PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version ≥ 50). Endorsement of traumatic experiences was high, including adult emotional (51.8%), physical (49.6%), and sexual (26.3%) abuse; childhood physical (35.0%) and sexual (25.9%) abuse; and other types of trauma (83%). All categories of traumatic experiences, except the “other” category, were associated with hazardous drinking. PTSD symptoms mediated 46% of the relationship between the number of traumatic categories experienced and drinking behavior.

Conclusions:

Women reported high rates of hazardous drinking and high levels of PTSD symptoms, and most had some history of traumatic events. There was a strong relationship between traumatic exposure and drinking levels, which was largely mediated by PTSD symptoms. Substance use interventions should address histories of trauma in this population, where alcohol may be used in part to cope with past traumas.

South africa has high rates of both hazardous drinking and traumatic experiences, and studies from other settings suggest that these two public health issues are closely related (Kaysen et al., 2007; Khoury et al., 2010; McFarlane, 1998). The proportion of South Africans who drink alcohol is fairly low (in a national household survey, just 39% of men and 16% of women reported alcohol use in the past year). But considering only those who drink, South Africa has one of the highest per-capita rates of alcohol consumption in the world (Parry et al., 2005; Rehm et al., 2003). The prevalence of traumatic experiences also is very high in this setting, especially among women. Studies have documented that nearly half of South African women experience physical or sexual assault from a male partner in their lifetimes (Dunkle et al., 2004; Jewkes et al., 2002), and more than 30% have a history of childhood sexual abuse (Seedat et al., 2009; Suliman et al., 2009). In South Africa, women also are vulnerable to other types of traumatic events, including violent crimes and the unexpected loss of children or loved ones (Gass et al., 2011).

Some survivors of traumatic events may experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a psychiatric condition that affects cognitive, behavioral, and emotional processes. PTSD has been closely associated with drinking behavior—suggesting that alcohol may be used in part to numb PTSD symptoms (Breslau et al., 2003; Jané-Llopis and Matytsina, 2006). The relationship between traumatic exposure and alcohol use disorders, and the role of PTSD in mediating that relationship, had not been explored previously among South African women.

Traumatic experiences are events that involve actual or threatened death or severe injury to which the victim responds with fear, helplessness, or horror (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Common examples of traumatic events include physical assault, sexual assault, natural disasters, and serious accidents. The relationship between traumatic experiences and substance use, including alcohol use, has been well established in both the United States (Beseler et al., 2011; Clark and Foy, 2000; Kaysen et al., 2007; Khoury et al., 2010; McFarlane, 1998) and South Africa (Gass et al., 2011; Jewkes et al., 2002). Experiencing trauma may lead to earlier onset of alcohol consumption, more frequent drinking, heavier drinking, and a greater likelihood of developing an alcohol use disorder (Beseler et al., 2011; Clark and Foy, 2000; Clark et al., 2010; Dom et al., 2007; Kaysen et al., 2007).

Specifically, research has established a link between interpersonal violence and alcohol use. In the United States, studies have shown that women in physically abusive relationships and those who have experienced sexual assault drink greater quantities of alcohol and are at greater risk for alcohol use disorders compared with women who have not experienced these traumas (Clark and Foy, 2000; Kaysen et al., 2007). A limited number of studies in South Africa suggest a similar pattern (Gass et al., 2011; Jewkes et al., 2002). In addition, research in the United States indicates that girls who experience childhood abuse have an earlier age at onset of both drinking behavior and subsequent alcohol use disorders (Clark et al., 2010; Dom et al., 2007), with the severity of the childhood abuse directly linked to the severity of alcohol use (Clark and Foy, 2000; Dom et al., 2007; Kaysen et al., 2007; Khoury et al., 2010; McFarlane, 1998). Types of traumatic experiences other than interpersonal violence, such as witnessing severe injury or being in a life-threatening accident, also have been associated with alcohol use (Beseler et al., 2011), although these experiences are rarely explored exclusive of interpersonal traumas (McFarlane, 1998). Therefore, the relationship is not well understood.

Some studies suggest that experiencing one particular type of traumatic experience, particularly childhood sexual abuse, may have a greater impact on subsequent drinking behavior than exposure to trauma in general (Beseler et al., 2011; Kaysen et al., 2007; McFarlane, 1998). However, research indicates that having one traumatic experience significantly increases the likelihood of having another (Roodman and Clum, 2001; Sadavoy, 1997; Smith et al., 2010), making it difficult, and potentially misleading, to attempt to determine the specific trigger for drinking behavior. As a result, research has explored the cumulative effect of traumas on psychological and behavioral outcomes. Findings of these studies suggest a dose-response effect of trauma exposure (cumulative traumatic experiences) on the severity of substance use (Bensley et al., 2000; Dube et al., 2002) and other behavioral outcomes (Hillis et al., 2001; Mugavero et al., 2006).

The relationship between traumatic experiences and heavy drinking may be explained, in part, by the development of PTSD symptoms (Kaysen et al., 2007). PTSD is a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), psychiatric condition that develops in some people after exposure to a severe traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The diagnosis of PTSD consists of three symptom clusters: (a) re-experiencing (e.g., intrusive recollections of the trauma that are triggered by exposure to cues symbolizing the trauma), (b) avoidance (e.g., diminished participation in activities and avoidance of thoughts, people, places, and memories associated with the trauma), and (c) arousal (e.g., difficulty sleeping, irritability, difficulty concentrating, hypervigilance, and exaggerated startle response). Although exposure to any traumatic event has the potential to lead to PTSD, interpersonal violence—including childhood abuse, rape, and physical assault—is associated with a higher risk of developing PTSD compared with events that are less personally traumatic (Breslau, 2002; Breslau et al., 1999; Kessler et al., 1995; Resnick et al., 1993). Women are more vulnerable to developing PTSD because they are more likely to be exposed to invasive traumas, such as rape or physical attack, which are associated with a higher risk of development of PTSD (Davidson et al., 1991; Gavranidou and Rosner, 2003; Kessler et al., 1995; Stein et al., 2000). Research also has suggested that women may be more likely than men to develop PTSD regardless of the type of traumatic exposure, although the causality of this relationship is not well understood (Walker et al., 2004).

The presence of PTSD symptoms has been associated with a greater likelihood of substance use disorders (Breslau et al., 1991, 1997, 2003; Kaysen et al., 2007). Alcohol use disorders are disproportionately common among persons with PTSD, being the most common co-occurring psychiatric disorder among men with PTSD and the third most common among women with PTSD (Kessler et al., 1995). Severity of PTSD symptoms, particularly avoidance and arousal, tend to be higher among PTSD patients with co-occurring substance use disorders (Hien et al., 2010; Saladin et al., 1995). The relationship between PTSD and substance use may be explained in part by individuals with PTSD using alcohol and others substances to help to cope with their psychiatric symptoms (Jané-Llopis and Matytsina, 2006; Kaysen et al., 2007; Kessler et al., 1997; Saladin et al., 1995).

The aim of the current study was to explore the relationship between the experience of traumatic events and hazardous drinking among women attending alcohol-serving venues in one township in Cape Town, South Africa, and to examine PTSD as a mediator of this relationship. We hypothesized that, across all categories of traumatic experiences, exposure to trauma would be associated with greater odds of hazardous drinking. Furthermore, we hypothesized that increased trauma exposure (i.e., experiencing a greater number of different types of traumatic experiences) would be associated with drinking behavior and that this relationship would be explained largely by PTSD symptoms. This study contributes to our understanding of factors that precipitate hazardous drinking among women in a South African township and can therefore help to inform interventions to reduce problem drinking in this population.

Method

Study site

The study took place in a single peri-urban township in Cape Town, South Africa. This township was established in the early 1990s and has a fairly equal number of residents who are Xhosa-speaking Black African and Afrikaans-speaking Coloured. (Coloured is a South African demographic term for individuals of historically mixed race.) Using an adaptation of the Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts methodology (Weir et al., 2003), 609 street intercept surveys were conducted to identify places where people go to drink alcohol. Study staff members visited all identified venues to assess them for venue eligibility (space for patrons to sit and drink in the venue, >50 unique patrons per week, >10% female patrons, and willingness to have the research team visit the venue on a regular basis). Twelve venues, geographically dispersed throughout the township, were selected for inclusion in the study. Because venues attracted customers who were primarily either Black African or Coloured, six of each type of these venues were selected.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from the 12 study venues. Following a week of regular observations in the venues, during which time research staff members gained familiarity with the setting and patrons, the staff invited female patrons in the venue to be part of a cohort study to examine drinking and sexual behavior over the course of 1 year. Women were eligible to participate if they drank in the venue and lived in the township. A total of 604 women were approached to participate and given an appointment card to come to the study office to provide informed consent and complete a baseline assessment. Almost all (560, 92.7%) came for the initial appointment and enrolled in the study.

Structured interviews were completed using audio computer-assisted self-interview technology. Participants wore headphones, and the pre-recorded questions were delivered in a language of their choosing (English, Xhosa, or Afrikaans). Staff members instructed the participants on how to complete the audio computer-assisted self-interview assessment and were available to answer questions as needed. Participants received compensation for completing the survey in the form of a grocery gift card valued at 150 Rand (approximately $20). All study procedures were approved by the ethical review boards of the relevant institutions.

Measures

Traumatic experiences.

Adult emotional intimate partner violence (IPV), physical IPV, and sexual violence were measured using a shortened version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., 1996). The measure asked about two forms of emotional IPV (partner insulted or swore at you; threatened to hit or throw something at you), four forms of physical IPV (partner kicked, bit, or punched you; beat you; hit you with something; used a knife or gun on you), and five forms of sexual violence (someone used force to make you have sex; used threats to make you have sex; made you have anal sex against your will; made you drunk or high to force you to have sex; forced you to have sex with multiple men on one occasion). Questions asked about whether the incident had ever happened and how often it happened in the past 4 months. For the purpose of this study, only the lifetime experience (yes/no) was used, because we were interested in how past traumatic events may lead to the development of PTSD symptoms and chronic drinking patterns.

Childhood abuse was measured with a shortened version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein et al., 2003). The measure asked about experiences as a child (younger than 18 years) of physical or emotional abuse or neglect (hit by a family member so hard it left bruises or marks; called stupid, lazy, or ugly; parents too drunk or high to take care of the family) and sexual abuse (sexual touching; threats to do something sexual; forced to have sexual intercourse).

Other traumatic experiences were measured using an adaptation of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview, PTSD Section (Schneider et al., 2004). The original measure asks about lifetime experience of 26 traumatic experiences. Our measure included traumatic experiences that our team identified as most common and specific to the South African context. These included four items related to other experienced/observed violence (e.g., mugged or held up; diagnosed with a serious illness; having observed violence in the home) and five items related to other unexpected traumatic events (e.g., being in a serious car or train accident; having a son/daughter die). All items were asked about lifetime experience, with a yes/no response.

Alcohol consumption behavior.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to measure alcohol consumption (Babor et al., 2001; Saunders et al., 1993). The AUDIT was developed by the World Health Organization to screen for hazardous and harmful patterns of alcohol consumption and has been used across a range of settings and cultures, including South Africa (Peltzer et al., 2011; Pengpid et al., 2011). The measure includes 10 questions about the frequency and quantity of drinking, heavy episodic drinking, symptoms of alcohol dependence, and harm associated with alcohol use. Each question has a response range of 0–4. We used the recommended cutoff score of 8 to identify individuals as hazardous drinkers (Babor et al., 2001). The four-item CAGE screening (Ewing, 1984) for alcohol dependence also was administered and was highly correlated with AUDIT scores (r2 = .554, p < .001), providing validity for the AUDIT as a measure. The continuous AUDIT score was used in the regression analyses that examined the mediation hypothesis.

PTSD symptom severity.

The PTSD Checklist–Civilian Version (PCL-C) was used to assess symptoms of PTSD (α = .95). The measure includes 17 items that correspond to the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD (e.g., trouble sleeping; feeling jumpy; avoiding situations because they serve as reminders of trauma). Respondents indicated how much they had been bothered by each symptom in the past month using a 5-point (1–5) scale. Total scores on the checklist ranged from 17 to 85. To describe indication of potential PTSD diagnosis, we used a more sensitive cutoff score of 30 (Lang et al., 2003; Walker et al., 2002), as well as a more conservative cutoff of 50, which was originally proposed by the test developers (Weathers et al., 1993). The continuous symptom score was used for the mediation analyses.

Analysis

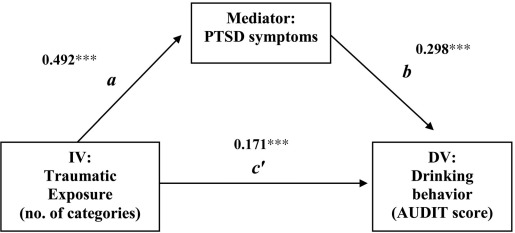

Quantitative analysis was conducted using SPSS Version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). First, we conducted descriptive analyses for demographic characteristics and traumatic experiences. Second, using logistic regression, we explored whether categories of traumatic experiences were associated with hazardous drinking (AUDIT ≥ 8). Third, we used a series of three regression equations to test our hypothesis that PTSD symptoms mediated the relationship between the number of traumatic categories experienced and alcohol use (see Figure 1, mediation diagram). We first estimated the overall effect of traumatic exposure on alcohol use (c effect). We then estimated the effect of traumatic exposure on PTSD symptoms (a effect). Finally, we predicted alcohol use through equations that included both PTSD (b effect) and traumatic exposure (c' effect) as predictors. We examined the extent to which the estimate of c' was smaller than c. We also computed an estimate of the ab effect (i.e., the mediated effect) and tested the significance of the ab effect through the computation of asymmetric confidence limits for the distribution of two normally distributed variables using the PRODCLIN program (MacKinnon et al., 2007). Finally, we computed the proportion of the total effect of traumatic exposure on alcohol use that was mediated by PTSD symptoms (ab / c).

Figure 1.

Mediation model tested. Standardized regression coefficients are shown. c = 0.318***. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; IV = independent variable; DV = dependent variable; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

***p < .001.

Results

The sample is described in Table 1. The 560 participants had a mean age of 34 years (range: 18–75) and included 61.3% who self-identified as Coloured and 36.4% who self identified as Black. The majority (80.7%) had children, but only 27.0% were married. Very few participants (3.6%) had a postsecondary education, and the majority (73.9%) were unemployed at the time of the survey.

Table 1.

Description of the sample (n = 560)

| Demographic characteristics | M (SD) or % |

| Age, M (SD) | 33.9 (11.6) |

| Race, % | |

| Coloured | 61.3 |

| Black | 36.4 |

| Other | 2.4 |

| Education, % | |

| Less than high school | 33.6 |

| Some high school | 62.9 |

| Completed high school | 3.6 |

| Currently employed, % | 26.1 |

| Currently married, % | 27.0 |

| Has children, % | 80.7 |

| Economic markers | |

| No. of people living in the home, M (SD) | 5.2 (2.5) |

| Home has electricity, % | 96.8 |

| Home has tap water, % | 89.6 |

| Home has refrigerator, % | 80.2 |

| Alcohol use | |

| AUDIT score, M (SD) | 12.15(7.3) |

| Hazardous drinking (≥8), % | 70.9 |

| Problem drinking (>16), % | 30.7 |

| Frequency of drinking alcohol, % | |

| Monthly or less | 28.2 |

| 2–4 times per month | 33.8 |

| 2–3 times per week | 25.9 |

| ≥4 times a week | 12.1 |

| No. of drinks per drinking day, % | |

| 1–2 drinks | 26.6 |

| 3–4 drinks | 26.2 |

| 5–6 drinks | 24.0 |

| ≥7 drinks | 23.2 |

| Frequency of consuming ≥6 drinks, % | |

| Less than monthly | 36.9 |

| Monthly | 25.1 |

| Weekly | 33.9 |

| Daily or almost daily | 5.0 |

Note: AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Alcohol use in this sample was irregular but heavy. Only 12.1% of the sample reported that they drank at least four times a week, but when asked how much they consume on days of drinking, almost half (47.2%) reported that they typically consumed five or more drinks per occasion. The mean AUDIT score in the sample was 12.2 (range: 0–34). The majority of the sample (70.9%) met the criteria for hazardous drinking (AUDIT ≥ 8), and almost a third (30.7%) met the criteria for severe problem drinking (AUDIT ≥ 16). PTSD scores in the sample ranged from 17 to 85 with a mean of 36.3 (SD = 16.3). More than half (52.3%) of the sample met sensitive criteria for PTSD (PCL-C ≥ 30), and a fifth (20.9%) met the more conservative criteria (PCL-C ≥ 50).

Endorsement of the seven categories of traumatic experiences was high (Table 2). For adult abuse by an intimate partner, 51.8% reported a lifetime experience of emotional abuse, 49.6% reported a history of physical abuse, and 26.3% reported a history of sexual abuse. As a child, 35.0% reported physical or emotional abuse or neglect, and 25.9% reported sexual abuse. In addition, 71.1% reported some other experienced or observed violence, and 65.7% reported another unexpected traumatic experience. Considering all traumatic experiences together, 90.7% of participants reported at least one experience. Participants endorsed anywhere from 0 to 7 traumatic categories, with a mean of 3.3 categories (SD = 2.0).

Table 2.

Report of lifetime traumatic experiences (n = 560)

| Variable | % reporting trauma |

| Adult emotional IPV, any | 51.8 |

| Sex partner insulted or swore at you | 44.1 |

| Sex partner threatened to hit / throw something at you | 39.3 |

| Adult physical IPV, any | 49.6 |

| Sex partner kicked, bit, or punched you | 38.9 |

| Sex partner beat you | 41.3 |

| Sex partner hit you with something | 28.2 |

| Sex partner used a knife or gun on you | 8.9 |

| Adult sexual abuse, any | 26.3 |

| Used force to make you have sex | 18.4 |

| Used threats to make have sex | 11.8 |

| Made you have anal sex | 8.2 |

| Made you use drugs/alcohol so they could force sex | 8.4 |

| Gang raped | 3.4 |

| Childhood physical/emotional abuse, any | 35.0 |

| Hit so hard it left me with bruises | 21.3 |

| Called stupid, lazy, or ugly | 22.5 |

| Parents too drunk/high to take care of the family | 9.8 |

| Childhood sexual abuse, any | 25.9 |

| Sexual touching | 20.5 |

| Threatened unless I did something sexual | 13.8 |

| Forced to have intercourse | 16.3 |

| Other experienced/observed violence, any | 71.1 |

| Mugged, car-jacked, threatened with a weapon | 25.9 |

| Observed violence in your home | 31.3 |

| As an adult, badly beaten up | 29.1 |

| Seen someone badly injured/kill, seen a dead body | 54.1 |

| Other unexpected events, any | 65.7 |

| Fire, flood, disaster destroyed home | 16.4 |

| Serious car or train accident | 15.9 |

| Diagnosed/hospitalized with serious/life-threatening illness | 19.5 |

| Had someone close die unexpectedly | 47.1 |

| Had a son/daughter die | 17.0 |

Note: IPV = intimate partner violence.

Traumatic experiences associated with hazardous drinking

Table 3 presents the associations between the seven categories of traumatic experiences and hazardous drinking. In all categories of traumatic experiences except for “other unexpected traumatic events,” women who had a lifetime experience of the trauma had significantly greater odds of reporting hazardous drinking compared with women who had not experienced the trauma (significant odds ratios ranging from 1.61 to 2.60).

Table 3.

Proportion of women who report hazardous drinking (AUDIT ≥ 8), by exposure to different categories of trauma (n = 560)

| Trauma categories | % Hazardous drinkers |

Unadjusted odds ratio [95% CI] | |

| Trauma % | No trauma % | ||

| Any adult emotional abuse | 79.0 | 62.2 | 2.28 [1.57, 3.32] |

| Any adult physical abuse | 77.7 | 64.2 | 1.94 [1.34, 2.82] |

| Any adult sexual abuse | 83.7 | 66.3 | 2.60 [1.61, 4.21] |

| Any childhood physical/emotional abuse | 77.0 | 67.6 | 1.61 [1.08, 2.40] |

| Any childhood sexual abuse | 82.8 | 66.7 | 2.39 [1.48, 3.85] |

| Other experienced/observed violence | 75.4 | 59.9 | 2.05 [1.39, 3.02] |

| Other unexpected traumatic events | 73.1 | 66.7 | 1.36 [0.93, 1.98] |

Posttraumatic stress disorder as a mediator between traumatic experiences and drinking behavior

The number of traumatic categories endorsed was strongly associated with the AUDIT score for drinking behavior (c effect = 0.318, p < .001). In the analysis of mediation (Figure 1), the number of traumatic categories endorsed was associated with PTSD (a effect = 0.492, p < .001), and PTSD was associated with drinking behavior (b effect = 0.298, p < .001). The effect of traumatic events on drinking behavior (c effect) was reduced when PTSD was included in the model (c' effect = 0.171, p < .001). This finding, along with the significance as indicated by 95% asymmetric confidence limits around the indirect effect (unstandardized estimate ab = 0.54, 95% CI [0.368, 0.722]), lends support to our mediation model. The proportion of the total effect of traumatic exposure on drinking behavior mediated by PTSD was 0.46 (unstandardized estimates ab / c = (4.05)(0.133) / 1.166 = 0.46). In parallel analyses, we examined the mediation hypothesis separately for each of the seven types of traumatic experiences. Very similar results were found; significant mediated effects of trauma through PTSD symptoms to hazardous drinking existed regardless of the type of trauma.

Discussion

Among our sample of women attending drinking venues in a Cape Town township, there was a high prevalence of traumatic experiences across all categories of trauma, and hazardous drinking was more common among women who had experienced traumas compared with women who had not. Reporting a greater number of categories of traumatic experiences was strongly associated with drinking behavior, and PTSD explained almost half of the total effect of traumatic exposure on alcohol consumption. The co-occurrence of PTSD and hazardous drinking has been described in other settings, but this is the first study to explore the relationship among South African women, for whom traumatic experiences are very common. The findings add to our understanding of the link between traumatic exposure and drinking behavior in this setting and strongly support the need for joint interventions that address both trauma/PTSD and heavy alcohol use.

The prevalence of adult physical IPV and sexual assault in this sample is similar to what has been identified in other South African studies (Dunkle et al., 2004; Jewkes et al., 2002; Seedat et al., 2009; Suliman et al., 2009), with about half of the women reporting lifetime physical IPV from a sexual partner and a quarter reporting a history of sexual assault. It is notable, however, that our sample was young, and lifetime prevalence of IPV and assault is likely to increase over time. The relationship between traumatic experience categories and hazardous drinking was significant for both adult and childhood abuse experiences. Given the high overlap between childhood and adult abuse experiences found in South Africa (Gass et al., 2011; Jewkes et al., 2002) and other settings (McIntyre and Widom, 2011; Widom et al., 2008), it was impossible to tease apart the independent effects of each on hazardous drinking. Nevertheless, the effect on hazardous drinking was strongest among women who reported sexual abuse, including either adult sexual assault or sexual abuse as a child. This is consistent with research in the United States that has shown that female survivors of sexual assault are at increased risk for problem drinking (Kilpatrick et al., 1997; Wilsnack et al., 1997).

Even using a very conservative cutoff on the PCL-C measure of PTSD, one fifth of the sample met symptom criteria for PTSD. It is important to note that our measure of PTSD is not diagnostic, and symptoms were not assessed specifically for a given trauma; therefore, the proportion meeting screening criteria for PTSD may overstate the true sample prevalence. Nevertheless, data from clinic-based studies in South Africa have reported similarly high rates of PTSD, ranging from 12% to 20% (Carey et al., 2003; Peltzer et al., 2007). For comparison, the prevalence of PTSD among adults in the United States is 3.4%, as assessed by the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiologic Surveys (Pagoto et al., 2012). The high rates of PTSD in South Africa must be understood within the cultural context in which violence is commonplace, stemming from the country's history of political violence and gross social inequalities (Jewkes and Abrahams, 2002; Kaminer et al., 2008). Although treatment for PTSD is sorely needed in this population, treatment services are widely lacking, especially in South Africa's most impoverished communities (Bruwer et al., 2011). Effective treatments for PTSD include cognitive–behavioral therapy (Foa and Rothbaum, 1998), cognitive reprocessing therapy (Resick et al., 2008), and pharmacological treatment (Stein et al., 2006).

Although our data are cross-sectional and cannot be used to establish the temporal relationship between the onset of heavy drinking and the development of PTSD symptoms, there does appear to be some preliminary support for the hypothesis that alcohol may be used in part to cope with distress, particularly given that the relationship remained when we looked exclusively at childhood trauma exposures. It is possible that women with PTSD may use alcohol to avoid triggers and numb their symptoms, particularly given the lack of more appropriate treatment options in the community. This mechanism, often referred to as the “self-medication hypothesis,” has been studied extensively in Western settings (Chilcoat and Breslau, 1998; Kaysen et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2009), including among samples of problem drinkers (Dom et al., 2007; Reynolds et al., 2005). However, such a model had not been examined previously in a South African setting. It has been suggested that the use of avoidant coping strategies may help to explain the relationship between PTSD and substance use (Santello and Leitenberg, 1993; Ullman et al., 2007; Valentiner et al., 1996). This deserves further investigation in the South African setting, where it may help to inform culturally appropriate ways to break the cycle between trauma and substance use.

Our conceptual model examined trauma exposure as a number of categories endorsed, which is more robust than a dichotomous measure of trauma exposure. Previous studies among women have shown that increasing types of traumatic experiences (e.g., childhood and adult abuse) were associated with greater trauma symptoms (Follette et al., 1996; Gold et al., 1994). In addition, a study in South Africa documented an increasing number of traumas among adolescents to be associated with greater PTSD symptoms (Suliman et al., 2009). However, it is important to note that the number of categories endorsed is not equivalent to the number of instances or the severity of the experience. It is also possible that one experience could have met multiple categories of traumatic exposure (for example, a sexual assault may include adult emotional, physical, and sexual abuse), or that someone may have experienced repeated traumatic events in a single category. From the sexual abuse literature, we know that longer duration, increased frequency, and more invasive sexual abuse, along with prior victimization or concurrent physical abuse, leads to poorer psychological outcomes (Walker et al., 2004).

It is likely that the relationship between traumatic exposure and drinking behavior is cyclical and reinforcing. The mediation analyses tested our conceptual hypothesis that traumatic events led to PTSD symptoms, which in turn led to higher levels of alcohol use. Longitudinal studies support this hypothesis (Beseler et al., 2011; Clark and Foy, 2000; Clark et al., 2010; Dom et al., 2007; Kaysen et al., 2007). However, it is also very likely that, in the context of heavy drinking, women increase their vulnerability to the opportunity for repeated traumas (Kilpatrick et al., 1997; McFarlane, 1998). We know from both research and our own observations in these settings that heavy drinking makes one more vulnerable to traumatic experiences, including physical and emotional violence from intimate partners and others, sexual assault, and the witnessing of traumatic events (Boles and Miotto, 2003; Foran and O'Leary, 2008). Nevertheless, the fact that we had strong associations between childhood abuse (likely preceding the onset of drinking) and hazardous alcohol consumption lends support to our hypothesis that alcohol was used by some as a way to cope with past traumas.

This study has limitations that may affect the generalizability of our findings. The sample included only women who attended alcohol-serving venues, with a large proportion reporting hazardous drinking behaviors and lifetime traumatic experiences. It is not possible to make conclusions about the relationship between traumatic experiences and drinking in the larger community population, but it is reasonable to assume that there might be an even stronger association in a sample that includes nondrinkers and infrequent drinkers. As our data are cross-sectional, we do not know whether traumatic experiences preceded the onset of hazardous drinking or whether hazardous drinking made women more vulnerable to traumatic experiences. Finally, in our measurement of traumatic experiences, we did not capture the number of events per category, repeated events, or the severity of events, which would have provided a richer measure of traumatic exposure than the number of categories endorsed. In addition, we may have missed other forms of traumatic experiences in these women's lives that were not asked in the assessment. To better understand how cumulative and sustained traumatic events may lead to PTSD and, in turn, to hazardous drinking, future research might collect more detailed data about traumatic exposure.

Our findings have implications for clinical interventions in this setting. Given the high level of co-morbidity of traumatic exposure and hazardous drinking in our sample, there is a great need to integrate treatment of trauma/PTSD and substance use. Our data suggest that traumatic experiences and related PTSD should be assessed and treated as potential drivers of hazardous drinking behavior. Clinical interventions that address comorbid trauma/PTSD and substance use in women are necessary and may provide therapeutic benefit in this population. Unfortunately, no evidence-based interventions exist to effectively address these co-occurring conditions. The Seeking Safety model, a cognitive group therapy treatment that was developed to concurrently address trauma and substance use treatment (Najavits, 2002), has shown promise, but a multisite randomized trial in the United States found that it was no more effective than a health education intervention (Hien et al., 2009). The authors of that study recommend future research that may include pharmacological treatment, the incorporation of exposure therapy and gender-specific content, and a longer treatment model. While we continue to pursue evidence of effective treatment in the United States, there may be benefit in simultaneously developing and testing culturally appropriate interventions for women in low-resource settings in South Africa, where traumatic experiences and rates of hazardous drinking are high.

This study lends strong evidence to the relationship between traumatic experiences and drinking behavior among South African women and helps to explain this relationship through PTSD symptoms. Our findings point to the urgent need for integrated treatment of trauma, PTSD, and hazardous alcohol use for women in this setting. Future research in this area is needed to understand more about the onset of hazardous drinking behavior following traumatic events and alternative ways of coping with trauma in this setting to inform the adaptation of appropriate clinical interventions.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01 AA018074, National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant K23 DA028660 and the Duke University Center for AIDS Research, a National Institutes of Health–funded program (P30 AI064518).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bensley LS, Van Eenwyk J, Simmons KW. Self-reported childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult HIV-risk behaviors and heavy drinking. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18:151–158. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00084-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ah-luvalia T, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beseler CL, Aharonovich E, Hasin DS. The enduring influence of drinking motives on alcohol consumption after fateful trauma. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1004–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles SM, Miotto K. Substance abuse and violence: a review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;8:155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N. Gender differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Gender-Specific Medicine. 2002;5:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Peterson EL, Lucia VC. Vulnerability to assaultive violence: Further specification of the sex difference in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:813–821. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson E. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48:216–222. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810270028003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Peterson EL, Schultz L. Psychiatric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:81–87. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130087016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Schultz LR. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the incidence of nicotine, alcohol, and other drug disorders in persons who have experienced trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer B, Sorsdahl K, Harrison J, Stein DJ, Williams D, Seedat S. Barriers to mental health care and predictors of treatment dropout in the South African Stress and Health Study. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62:774–781. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.7.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey PD, Stein DJ, Zungu-Dirwayi N, Seedat S. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban Xhosa primary care population: Prevalence, comorbidity, and service use patterns. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2003;191:230–236. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000061143.66146.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Investigations of causal pathways between PTSD and drug use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:827–840. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AH, Foy DW. Trauma exposure and alcohol use in battered women. Violence Against Women. 2000;6:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Martin CS. Child abuse and other traumatic experiences, alcohol use disorders, and health problems in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:499–510. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Hughes D, Blazer DG, George LK. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: An epidemiological study. Psychological Medicine. 1991;21:713–721. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700022352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dom G, De Wilde B, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B. Traumatic experiences and posttraumatic stress disorders: Differences between treatment-seeking early- and late-onscoholic patients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2007;48:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB. Adverse childhood experiences and personal alcohol abuse as an adult. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:713–725. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. The Lancet. 2004;363:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: The CAGE questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Rothbaum B. Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Follette VM, Polusny MA, Bechtle AE, Naugle AE. Cumulative trauma: The impact of child sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and spouse abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:25–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02116831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O'Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Seedat S. Gender differences in risk for intimate partner violence among South African adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:2764–2789. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavranidou M, Rosner R. The weaker sex? Gender and posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2003;17:130–139. doi: 10.1002/da.10103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SR, Milan LD, Mayall A, Johnson AE. A cross-validation study of the trauma symptom checklist: The role of mediating variables. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1994;9:12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Campbell ANC, Killeen T, Hu M-C, Hansen C, Jiang H, Nunes EV. The impact of trauma-focused group therapy upon HIV sexual risk behaviors in the NIDA Clinical Trials Network "Women and trauma" multisite study. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:421–430. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9573-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien DA, Wells EA, Jiang H, Suarez-Morales L, Campbell AN, Cohen LR, Nunes EV. Multisite randomized trial of behavioral interventions for women with co-occurring PTSD and substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:607–619. doi: 10.1037/a0016227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: A retrospective cohort study. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jané-Llopis E, Matytsina I. Mental health and alcohol, drugs and tobacco: A review of the comorbidity between mental disorders and the use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:515–536. doi: 10.1080/09595230600944461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Abrahams N. The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: An overview. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: Findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55:1603–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer D, Grimsrud A, Myer L, Stein DJ, Williams DR. Risk for post-traumatic stress disorder associated with different forms of interpersonal violence in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:1589–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Dillworth TM, Simpson T, Waldrop A, Larimer ME, Resick PA. Domestic violence and alcohol use: Trauma-related symptoms and motives for drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1272–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury L, Tang YL, Bradley B, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ. Substance use, childhood traumatic experience, and posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban civilian population. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:1077–1086. doi: 10.1002/da.20751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang AJ, Laffaye C, Satz LE, Dresselhaus TR, Stein MB. Sensitivity and specificity of the PTSD checklist in detecting PTSD in female veterans in primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:257–264. doi: 10.1023/A:1023796007788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC. Epidemiological evidence about the relationship between PTSD and alcohol abuse: The nature of the association. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:813–825. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre JK, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and crime victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:640–663. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, Leserman J, Swartz M, Stangl D, Thielman N. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: The importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20:418–428. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM. Seeking safety: A treatment manual for PTSD and substance use. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Bodenlos JS, Appelhans BM, Whited MC, Ma Y, Lemon SC. Association of post-traumatic stress disorder and obesity in a nationally representative sample. Obesity. 2012;20:200–205. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry CDH, Plüddemann A, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R. Alcohol use in South Africa: Findings from the first Demographic and Health Survey (1998) Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:91–97. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Davids A, Njuho P. Alcohol use and problem drinking in South Africa: Findings from a national population-based survey. African Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;14:30–37. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v14i1.65466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Seakamela MJ, Manganye L, Mamiane KG, Motsei MS, Mathebula TT. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a rural primary care population in South Africa. Psychological Reports. 2007;100:1115–1120. doi: 10.2466/pr0.100.4.1115-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengpid S, Peltzer K, Van der Heever H. Prevalence of alcohol use and associated factors in urban hospital outpatients in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011;8:2629–2639. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8072629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Rehn N, Room R, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Jernigan D, Frick U. The global distribution of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking. European Addiction Research. 2003;9:147–156. doi: 10.1159/000072221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Galovski TE, O'Brien Uhlmansiek M, Scher CD, Clum GA, Young-Xu Y. A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:243–258. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Mezey G, Chapman M, Wheeler M, Drummond C, Baldacchino A. Co-morbid post-traumatic stress disorder in a substance misusing clinical population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Sareen J, Cox BJ, Bolton J. Self-medication of anxiety disorders with alcohol and drugs: Results from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodman AA, Clum GA. Revictimization rates and method variance: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:183–204. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadavoy J. Survivors: A review of the late-life effects of prior psychological trauma. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997;5:287–301. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199700540-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin ME, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Understanding comorbidity between PTSD and substance use disorders: Two preliminary investigations. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:643–655. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santello MD, Leitenberg H. Sexual aggression by an acquaintance: methods of coping and later psychological adjustment. Violence and Victims. 1993;8:91–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li WJ, Wilson IB. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:1096–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seedat M, Van Niekerk A, Jewkes R, Suffla S, Ratele K. Violence and injuries in South Africa: Prioritising an agenda for prevention. The Lancet. 2009;374:1011–1022. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60948-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith K, Bryant-Davis T, Tillman S, Marks A. Stifled voices: Barriers to help-seeking behavior for South African childhood sexual assault survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2010;19:255–274. doi: 10.1080/10538711003781269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Ipser JC, Seedat S. Pharmacotherapy for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002795.pub2. Article No. CD002795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR. Gender differences in susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Suliman S, Mkabile SG, Fincham DS, Ahmed R, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Cumulative effect of multiple trauma on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Psychosocial correlates of PTSD symptom severity in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:821–831. doi: 10.1002/jts.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentiner DP, Foa EB, Riggs DS, Gershuny BS. Coping strategies and posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of sexual and nonsexual assault. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:455–458. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Newman E, Dobie DJ, Ciechanowski P, Katon W. Validation of the PTSD checklist in an HMO sample of women. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2002;24:375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JL, Carey PD, Mohr N, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Gender differences in the prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and in the development of pediatric PTSD. Archives of Women s Mental Health. 2004;7:111–121. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0039-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska XA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. 1993, October Paper presented at the 9th Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Pailman C, Mahlalela X, Coetzee N, Meidany F, Boerma JT. From people to places: focusing AIDS prevention efforts where it matters most. AIDS. 2003;17:895–903. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000050809.06065.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Dutton MA. Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Vogeltanz ND, Klassen AD, Harris TR. Childhood sexual abuse and women's substance abuse: National survey findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:264–271. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]