Abstract

Objective:

Childhood maltreatment is associated with early alcohol use initiation, alcohol-related problem behaviors, and alcohol use disorders in adulthood. Heavy drinking risk among individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment could be partly attributable to stress sensitization, whereby early adversity leads to psychobiological changes that heighten sensitivity to subsequent stressors and increase risk for stress-related drinking. We addressed this issue by examining whether the association between past-year stressful life events and past-year drinking density, a weighted quantity–frequency measure of alcohol consumption, was stronger among adults exposed to childhood maltreatment.

Method:

Drinking density, stressful life events, and childhood maltreatment were assessed using structured clinical interviews in a sample of 4,038 male and female participants ages 20–58 years from the Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders. Stress sensitization was examined using hierarchical multiple regression analyses to test whether stressful events moderated the association between maltreatment and drinking density. Analyses were stratified by sex and whether the impact was different for independent stressful events or dependent stressful events as related to a participant's actions.

Results:

Independent stressful events were associated with heavier drinking density among women exposed to maltreatment. In contrast, drinking density was roughly the same across independent stressful life events exposure among women not exposed to maltreatment. There was little evidence for Maltreatment × Independent Stressor interactions in men or Maltreatment × Dependent Stressor interactions in either gender.

Conclusions:

Early maltreatment may have direct effects on vulnerability to stress-related drinking among women, particularly in association with stressors that are out of one's control.

Childhood maltreatment, which is typically defined to comprise physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect, is a well-established risk factor for early alcohol use initiation, alcohol-related problem behaviors, and alcohol use disorders in adulthood (Enoch, 2011). According to retrospective data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, approximately 8.4%, 6.0%, and 5.6%, respectively, of individuals in the United States report childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect, and a great majority of those are subjected to multiple forms of childhood adversity (Green et al., 2010).

A number of hypotheses have been proposed to explain increased risk for negative alcohol-related outcomes associated with childhood maltreatment. One possibility is that common environmental risk factors, such as a chaotic home environment, contribute to both maltreatment exposure and later drinking behaviors (Young-Wolff et al., 2011b). Alternatively, the association between maltreatment and alcohol-related outcomes could be indirect, such as the result of gene–environment interactions, in which a genetic predisposition toward problem drinking is potentiated by early maltreatment, or gene–environment correlations, in which individuals with a genetic predisposition are more likely to experience early maltreatment (Enoch, 2011; Young-Wolff et al., 2011a). Another possibility is that maltreatment directly increases risk for heavy drinking in adulthood. These alternatives are not incompatible, and there may be multiple pathways into stress-related drinking outcomes.

One relatively unexplored direct mechanism is stress sensitization, whereby early adversity leads to psychobiological changes that heighten sensitivity to subsequent stressors and increase risk for stress-related drinking. Early life stress has been shown to alter vulnerability to substance use disorders through its long-term effects on hypothalamic stress-response circuitry, through altered gene expression in the mesolimbic dopamine reward pathway, and via abnormalities in brain development (Enoch, 2011; Francis et al., 1999; Heim et al., 2000, 2002; Liu et al., 2000; Meaney et al., 2002). Stress sensitization in humans has been primarily studied in relation to the onset and recurrence of mood disorders, and a range of early life stressors (e.g., maltreatment, parental death) are associated with increased sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of stressful life events (SLEs) experienced in adolescence and adulthood (Dienes et al., 2006; Dougherty et al., 2004; Hammen et al., 2000; Harkness et al., 2006; Kendler et al., 2004; Morris et al., 2010; Rudolph and Flynn, 2007). Investigators have recently extended this line of research to include other outcomes, including anxiety disorders (Espejo et al., 2006; McLaughlin et al., 2010a) and the tendency to commit intimate partner violence (Roberts et al., 2011). Consistent with predictions of the stress sensitization hypothesis, the association between proximal stressors and adverse outcomes is consistently stronger among adults exposed to childhood adversity.

The current study was undertaken to investigate the stress sensitization hypothesis in relation to alcohol consumption and extends prior research in four important ways. First, to our knowledge, no previous study has examined whether the association of SLEs and alcohol consumption is stronger among adults with a history of childhood maltreatment. Given evidence that early adversity is associated with increased emotional reactivity (Glaser et al., 2006; Wichers et al., 2009), deficits in executive functioning and emotion regulation (McLaughlin and Hatzenbuehler, 2009; McLaughlin et al., 2009), and maladaptive coping strategies (Bal et al., 2003; Futa et al., 2003), we hypothesized that individuals with early exposure to maltreatment would be especially vulnerable to stress-related drinking.

Second, our study methodology allowed us to examine the causal relation between SLEs and alcohol consumption with greater power than in prior studies. An important conceptual and methodological challenge to the study of stress sensitization is that exposure to SLEs is not random. Individuals who experience more events at one time in their lives also report more events at other times (Andrews, 1981; Fergusson and Horwood, 1984). This could be because of the stability of adverse life circumstances (e.g., unemployment, living situation), but it could also be attributable to aspects of behavior and personality (Brett et al., 1990). If individuals with familial liability for heavy drinking are more likely to experience childhood maltreatment (e.g., if the perpetrator is related to the child, or via lower parental monitoring in alcoholic families) and adulthood SLEs (e.g., alcohol-related death of a family member), a stronger SLE-drinking association among those maltreated could simply index familial heavy drinking risk. The relation between SLEs and adult alcohol consumption could also be direct, for example, if maltreated individuals consume more alcohol and their heavier drinking leads to greater SLE exposure (e.g., car accident, injuries, job loss).

Because of this confounding, observational studies will never be able to control the SLE exposure of participants or to unconfound adult SLEs from trauma history. However, we can attempt to separate SLEs that are likely to be outcomes of an individual's behavior (i.e., “dependent SLEs” [dSLEs]) from those that are fateful or “independent” (iSLEs). Although the occurrence of independent events may still be elevated among those with trauma history because of exposure to other correlated environmental or genetic risk factors, we at least have better confidence that these events belong as covariates rather than as dependent variables in our causal equation. While the moderating role of maltreatment on the relation between SLEs that are dependent on one's behavior and alcohol consumption is ambiguous, studying SLEs that are random or not likely to be caused by a person's temperament or actions provides a clearer test of stress sensitization. Our study looked separately at the impact of dependent and independent SLEs, allowing us to better tease apart the mechanisms underlying the association between SLEs and drinking behaviors. Our assessment also improved on typically used checklists and inventories by objectively measuring SLEs independently of the participant's reactions or symptoms that developed after the event occurred.

Third, given evidence that childhood adversity may increase sensitivity to the depressogenic effects of SLEs, we adjusted for past-year depression symptoms in our analyses. This reduced the likelihood that stress sensitization results for alcohol consumption were actually attributable to past-year depression symptoms and clarified the specific effects of childhood maltreatment on stress-related drinking.

Fourth, this study examined gender as a moderator of stress sensitivity. To date, there is inconsistent evidence regarding whether risk for adverse alcohol-related outcomes associated with SLEs varies with gender (Keyes et al., 2011). A number of studies have found a stronger association of childhood maltreatment with excessive drinking and alcohol use disorders in women than men (Enoch, 2011; Simpson and Miller, 2002). There is also evidence that the mechanism for this effect may differ between men and women. Studies of female twin pairs discordant for childhood sexual abuse indicate that rates of alcohol use disorders are greater in the siblings exposed to sexual abuse compared with their unexposed siblings, suggesting that the association between maltreatment and alcohol use disorders is at least in part causal (Dinwiddie et al., 2000; Kendler et al., 2000; Nelson et al., 2002). In our own sample of female twins, this held true even after adjusting for a large number of potentially confounding risk factors, including parental psychopathology and parenting quality (Kendler et al., 2000). However, results from co-twin control studies of men show weaker direct effects (Nelson et al., 2002) and suggest that the increased risk for alcohol use disorders in men associated with history of childhood sexual abuse (Dinwiddie et al., 2000) and childhood maltreatment (Young-Wolff et al., 2011b) may be indirect and attributable to broader environmental adversity. These differences highlight the importance of investigating gender-specific processes underlying the association between childhood maltreatment and drinking behaviors in adulthood.

In summary, we used a large community-based sample of adult twins with detailed narrative data on dimensions of past-year SLEs (e.g., severity, event dependence) to (a) examine whether the association between SLEs (iSLEs or dSLEs) and past-year alcohol consumption varies with childhood maltreatment history, (b) investigate whether joint effects of childhood maltreatment and SLEs remain after adjusting for past-year depression symptoms, and (c) address whether Maltreatment × SLE interactions differ with gender.

Method

Subjects

The sample comprised individuals from the Virginia Adult Twin Study of Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders (VATSPSUD), a longitudinal study of White adult twins born in Virginia between 1934 and 1974, originally identified through the population-based Virginia Twin Registry (now part of the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry). Data for the current study come from our sample of male–male (MM) and male–female (MF) twin pairs interviewed across two waves of data collection: a telephone interview conducted 1993–1996, and an in-person interview conducted 1995–1998. The two interviews were at least 12 months apart, with an average interval of 18 months. Of 9,415 men and women eligible to participate in Wave 1 (MM/MF1), 6,812 individuals (72.4%) were interviewed, and 5,621 of these (82.5%) also participated in Wave 2 (MM/MF2) (see Kendler and Prescott, 2006). Data from the MM/MF sample was used for this study because it included assessment of multiple types of trauma and maltreatment. Participants from a parallel study of female–female twin pairs were not included in the current analyses because the assessment of SLEs was somewhat different, and participants were not asked the same questions on trauma and maltreatment (Kendler and Prescott, 2006). Data from the men in this sample were previously analyzed in a study examining pairs discordant for childhood maltreatment and risk for adult alcohol use disorders (Young-Wolff et al., 2011b) and in a study investigating the relation between age at drinking onset and stress-related drinking (Lee et al., 2012), but data on alcohol consumption in relation to trauma history have not been previously examined for these subjects. Additionally, this is the first report on childhood maltreatment history in relation to alcohol consumption or SLEs among the female twins from the MF pairs.

Childhood maltreatment was assessed at MM/MF1, and individual-level covariates, SLEs, and past-year alcohol consumption data were collected during MM/MF2. Consistent with previous research in this sample (Lee et al., 2012), and because we are interested in studying the influence of SLEs on drinking behaviors among current drinkers, we excluded lifetime abstainers (n = 254) and occasional drinkers who completely abstained from alcohol use in the year before the Wave 2 interview (n = 1,106). The analyses for this study are based on data from a total of 4,038 participants (3,122 men and 916 women) ages 20–58 (Mage = 36.0 years) who were current drinkers as of the MM/MF2 interview. All were informed about the purpose of the study and gave informed consent.

Measures

Childhood maltreatment.

Childhood maltreatment was assessed as part of the trauma history section of the Wave 1 structured interviews. Items were adapted from the posttraumatic stress disorder section of the National Comorbidity Study interview (Bromet et al., 1998). Participants were asked if they had experienced nine traumatic events and, if they responded yes, the age at which they first occurred. Childhood maltreatment was defined as experiencing one or more episodes of physical abuse (“Have you ever been physically abused?”), sexual abuse or molestation (“Have you ever been sexually abused or molested?”), or serious neglect (“Were you ever seriously neglected as a child?”) before age 15 (Young-Wolff et al., 2011b). This operationalization of childhood maltreatment (i.e., combining physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect) is commonly used in maltreatment research (e.g., Topitzes et al., 2009; Zielinski, 2009), and the age cutoff of 15 years is consistent with many prior investigations of childhood maltreatment (e.g., Dervic et al., 2006; Gibb et al., 2001; Showers et al., 2006).

Past-year stressful life events.

We assessed a variety of past-year SLEs occurring primarily to the participant (e.g., job loss, major financial problems, legal problems, divorce/ separation, robbery, serious illness/injury). Participants were also asked about SLEs occurring to members of their social networks. For each of six categories (spouse/partner, children, parents, co-twin, other siblings, and “someone else close to you”), we asked whether the network member had died, had experienced a serious illness or a serious personal crisis, or the respondent had serious trouble getting along with that person.

Using criteria adapted from Brown (1989), each SLE was rated objectively by trained interviewers on long-term contextual threat (LTCT) using a four-point scale (minor, lowmoderate, high-moderate, and severe). Long-term is defined as lasting at least a week, and ratings of high-moderate or severe LTCT required that an event or its impact persisted at least 10 days. The contextual aspect indicates that ratings were based on what most people would be expected to feel about an event given the respondent's particular life circumstances (e.g., age, financial situation), without taking into account what participants said about their reaction or the psychiatric or physical symptoms that followed the event (see Brown and Harris, 1989). Threat refers to the degree to which adapting to the event required changes to the core aspects of the participant's life plans or self-concept. Interviewers underwent extensive training and monitoring to ensure, as much as possible, that the interviewers were objective and did not allow participants’ emotional responses to influence the ratings. Interrater reliability of 92 randomly selected LTCT items was rs = .69, κ = .67, and 1-month test–retest reliability of LTCT among 191 individuals was rs = .60, κ = .41 (Kendler et al., 1998). As in previous research in this sample on SLEs and alcohol consumption (Lee et al., 2012), we analyzed only SLEs with high-moderate or severe LTCT ratings to focus on events that would likely have a longer term impact on drinking than events with minor or low-moderate LTCT ratings.

After using a structured set of probes to inquire about a specific event, interviewers rated whether that event was definitely independent, probably independent, probably dependent, or definitely dependent on the respondent's behavior using standardized, validated criteria adapted from Brown (1989). Interrater and test–retest reliabilities for categorizing events into independent or dependent were rs = .89 and rs = .77, respectively (Kendler et al., 1999). The independence rating for an SLE varied based on the impact of the event on each participant given his or her unique circumstances. For example, the same event (e.g., job loss) could be classified as either independent or dependent depending on the individual's situation. However, all SLEs involving interpersonal difficulties (e.g., divorce, trouble getting along with others) were categorized as dependent unless convincing evidence was presented to the contrary. These LTCT and event dependence ratings have been published extensively, and interested readers are referred to prior VATSPSUD studies for additional details (e.g., Kendler et al., 1998, 1999; Kendler and Prescott, 2006).

Past-year alcohol consumption.

Past-year alcohol consumption was based on a weighted quantity/frequency measure representing the average number of drinks consumed per month in the past year. Participants reported the number of drinks consumed on a typical day when they drank in the past year and the largest number of drinks they consumed on any single day in the past year. Interviewers grouped the responses into quantity categories: 1–3, 4–6, 7–9, 10–12, and 13 or more drinks. Participants also reported the number of days they consumed a drink in a typical month in the past year. Next, participants were asked to indicate the frequency with which they consumed their maximum number of drinks and one quantity category lower than their past-year maximum quantity using a provided list of frequency categories ranging from never to every day. The latter served as an intermediate measure to assess frequency of heavier drinking in case the maximum drinking was atypical.

Based on this information, we calculated the number of drinks consumed on days when a participant had (a) the largest number of drinks, (b) an intermediate number of drinks, and (c) a typical number of drinks. These three quantity estimates were weighted by their frequencies, resulting in past-year drinking density (PYDD), an estimate of the number of drinks consumed per month during the past year that is more accurate than a typical Quantity × Frequency measure (see Lee et al., 2012, for additional details on PYDD). PYDD scores were positively skewed, with some individuals having extreme values. We truncated PYDD at 720 (i.e., 24 drinks/ day) and log-transformed before analysis.

Covariates.

We examined several potentially confounding variables that could affect the associations among our key variables (maltreatment, SLEs, and alcohol consumption), including age, years of education, and number of past-year major depression symptoms based on criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Depression symptoms were assessed using an adapted version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM disorders (SCID; Spitzer and Williams, 1985). (See Kendler and Prescott, 2006, for details on depression and other assessments).

Statistical analyses

We investigated whether the association of SLEs with PYDD varied with exposure to maltreatment by testing a series of regression models. Models were estimated separately for iSLEs and dSLEs in men and women, adjusting for age and education. We first tested the separate main effects of maltreatment and iSLEs on PYDD. Next, we included both the maltreatment and iSLE main effects. We then added the interaction of Maltreatment × iSLEs. Finally, we included past-year depression symptoms to test whether Maltreatment × iSLE interaction effects on alcohol consumption were mediated by depression symptoms. This set of analyses was then repeated for dSLEs.

Standard errors and statistical tests were adjusted to account for nonindependence of data from twin pairs using hierarchical multiple regression (Proc Mixed) in SAS software Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Fewer than 3% of individuals had more than two dSLEs or iSLEs; therefore, these variables were recoded to have a maximum value of 2.

Results

Correlations and descriptive statistics for key variables are presented in Table 1. Group means of alcohol consumption for each category of SLEs and maltreatment are shown by sex in Table 2. In both sexes, maltreatment was significantly correlated with exposure to past-year iSLEs and dSLEs. Women had greater exposure to maltreatment, iSLEs and dSLEs, and stronger associations of maltreatment with SLEs and PYDD than men. The prevalences of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and serious neglect were 5.8%, 3.6%, and 3.5%, respectively, among men and 9.1%, 13.7%, and 4.0%, respectively, among women. Bivariate tetrachoric correlations among the three types of maltreatment ranged from .43 (for sexual abuse with physical abuse) to .69 (for physical abuse with severe neglect).

Table 1.

Correlations and descriptive statistics for demographic variables, childhood maltreatment, past-year stressful life events, and PYDD in men and women

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | Men (n = 3,122) M(SD)/% | Women (n = 916) M (SD)/% | |

| 1. Age, in years | – | −.07 | .02 | .11 | −.05 | −.14 | −.02 | 36.1 (9.0) | 35.7 (8.7) |

| 2. Education, in years | −.10 | – | −.07 | −.06 | −.07 | −.07 | −.05 | 13.7 (2.6) | 14.1 (2.3) |

| 3. Maltreatment | .06 | −.20 | – | .17 | .28 | .02 | .14 | 10.3% | 20.3% |

| 4. iSLEs | .08 | −.10 | .25 | – | .26 | .02 | .28 | 0.3(0.6) | 0.5 (0.7) |

| 5. dSLEs | −.02 | −.10 | .34 | .38 | – | .10 | .36 | 0.3 (0.6) | 0.4 (0.6) |

| 6. PYDD, drinks per month | −.18 | .05 | .02 | .03 | .11 | – | .15 | 18.8(2.7) | 7.7 (2.0) |

| 7. Depression symptoms | .04 | −.09 | .23 | .34 | .38 | .12 | – | 1.4(2.2) | 2.2 (2.6) |

Notes: Male correlations are above the diagonal; female correlations are below the diagonal. Correlations with maltreatment are bi-serial or poly-choric (as appropriate). Maltreatment = childhood maltreatment (coded 1/0); iSLEs = number of independent high-moderate or severe past-year stressful life events (categorized as 0, 1, ≥2); dSLEs = number of dependent high-moderate or severe past-year stressful life events (0, 1, ≥2); PYDD = log-transformed past-year drinking density (weighted Quantity × Frequency estimate of drinks per month in past year); depression = past-year DSM-IV depression symptoms (of 9); PYDD mean = group mean of log-transformed past-year drinking density, back-transformed to be in the original metric of drinks per month. Correlations are significant atp < .05 if the absolute value is greater than .03 for men and .06 for women.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics on PYDD by number of past-year independent and dependent stressful life events (SLEs) and childhood maltreatment

| Variable | No. of SLEs | Maltreated |

Not maltreated |

||

| n | PYDD M(SD) | n | PYDD M(SD) | ||

| iSLEs | |||||

| Women | None | 100 | 6.31 (2.1) | 512 | 7.89 (1.6) |

| 1 | 50 | 9.51 (2.2) | 146 | 7.17 (1.7) | |

| ≥2 | 36 | 13.08 (2.7) | 72 | 6.77 (2.2) | |

| Men | None | 211 | 20.09 (1.4) | 2,146 | 18.63 (2.6) |

| 1 | 71 | 23.95 (3.5) | 476 | 17.73 (2.9) | |

| ≥2 | 36 | 14.08 (3.1) | 173 | 23.42 (1.4) | |

| dSLEs | |||||

| Women | None | 105 | 6.20 (1.9) | 566 | 7.28 (1.89) |

| 1 | 45 | 11.12 (2.9) | 115 | 8.60 (1.99) | |

| ≥2 | 35 | 12.03 (2.3) | 50 | 9.84 (2.2) | |

| Men | None | 206 | 18.79 (3.1) | 2,312 | 17.68 (2.6) |

| 1 | 75 | 21.44 (3.1) | 328 | 22.31 (3.0) | |

| ≥2 | 37 | 25.45 (3.3) | 155 | 31.85 (3.0) | |

Notes: PYDD = past-year drinking density; mean PYDD = group mean of logtransformed PYDD, back-transformed to be in the original metric of drinks per month; iSLEs = high-moderate or severe independent past-year stressful life events (0, 1, ≥2); dSLEs = high-moderate or severe dependent past-year stressful life events (0, 1, ≥2).

Relation of drinking to independent SLEs

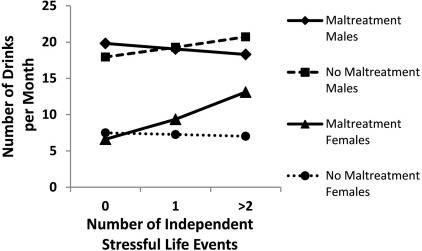

Multiple regression analyses were used to predict PYDD from maltreatment and iSLEs (Table 3). There were no significant main effects of maltreatment or iSLEs in either gender (Models 2a and 3a). Maltreatment × iSLE interactions were statistically significant in women (Model 4a): Among women who reported maltreatment, level of drinking was higher among those with more iSLEs (Figure 1). In contrast, among those with no history of maltreatment, PYDD was roughly the same across level of SLE exposure (0, 1, or ≥ 2 independent events). Conversely, among men, there was little evidence that maltreatment history moderated the association between iSLEs and PYDD (Model 4a).

Table 3.

Results from regression models predicting PYDD from childhood maltreatment and past-year independent and dependent stressful life events

| iSLEs | Model 1ab(SE) | Model 2ab(SE) | Model 3 ab(SE) | Model 4ab(SE) | Model 5 ab(SE) |

| Women (n = 916) | |||||

| Maltreatment | 0.11 (0.09) | – | 0.10 (0.09) | −0.11 (0.11) | −0.18(0.11) |

| iSLEs | – | 0.07 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.10(0.06) |

| Maltreatment × iSLEs | – | – | – | 0.36** (0.12) | 0.34** (0.11) |

| Depression symptoms | – | – | – | – | 0.07*** (0.01) |

| Men (n = 3,122) | |||||

| Maltreatment | 0.06 (0.08) | – | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.10 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.09) |

| iSLEs | – | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.01 (0.04) |

| Maltreatment × iSLEs | – | – | – | −0.12 (0.11) | −0.11 (0.11) |

| Depression symptoms | – | – | – | – | 0.07*** (0.01) |

| dSLEs | Model 1bb(SE) | Model 2bb(SE) | Model 3bb(SE) | Model 4bb(SE) | Model 5bb(SE) |

| Women (n = 916) | |||||

| Maltreatment | 0.11 (0.09) | – | 0.05 (0.09) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.10(0.11) |

| dSLEs | – | 0.20*** (.05) | 0.19*** (.06) | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.07) |

| Maltreatment × dSLEs | – | – | – | 0.20 (0.12) | 0.19(0.12) |

| Depression symptoms | – | – | – | – | 0.06*** (0.02) |

| Men (n = 3,122) | |||||

| Maltreatment | 0.06 (0.08) | – | 0.02 (0.08) | 0.08 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.09) |

| dSLEs | – | 0.19*** (0.04) | 0.19*** (0.04) | 0.21*** (0.04) | 0.14** (0.05) |

| Maltreatment × dSLEs | – | – | – | −0.15 (0.11) | −0.15 (0.11) |

| Depression symptoms | – | – | – | – | 0.06*** (0.01) |

Notes: PYDD = past-year drinking density (weighted Quantity × Frequency measure of drinks per month); iSLEs = high-moderate or severe independent past-year stressful life events (0, 1, ≥2); dSLEs = high-moderate or severe dependent past-year stressful life events (0, 1, ≥2); b = unstandardized regression weight. Intercept, age, and education were included in all models. PYDD was log-transformed using the equation: ln(x + 1).

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Model prediction of past-year drinking density (PYDD) by number of past-year independent stressful life events (iSLEs) and childhood maltreatment.Notes: Expected values of PYDD are based on parameter estimates from Model 4a in Table 3, using group means for demographic covariates. Regressionequations used log-transformed PYDD scores to adjust for positive skewness. Predicted values of PYDD (shown here) are back-transformed to be in theoriginal metric of drinks per month.

To investigate whether these gender differences in stress sensitization were significant, we tested for a three-way interaction among childhood adversity, iSLEs, and gender in predicting PYDD. Consistent with results from our two-way interactions stratified by gender, moderation of the iSLE– PYDD association by maltreatment was significantly weaker among men than among women (three-way interaction: b = −0.86, SE = 0.17, p < .0001).

Next, we tested whether the interaction between childhood maltreatment and iSLEs among women remained after adjusting for past-year major depression symptoms. Depression symptoms were significantly associated with PYDD; however, adjusting for depression symptoms had little influence on the strength or significance of the Maltreatment × iSLE interactions in either gender. For example, in women, the interaction regression coefficient after including depression symptoms was bMaltreatment × iSLE = 0.34 (SE = 0.11) (Model 5a, Table 3), very similar to that obtained without covariates (bMaltreatment × iSLE = 0.36, SE = 0.12; Model 4a, Table 3). These findings indicate that greater stress-related drinking among women with a history of childhood maltreatment is not explained by co-occurring depression symptoms.

Relation of drinking to dependent stressful life events

We repeated this series of analyses for dSLEs (Table 3). Childhood maltreatment was not associated with PYDD among men or women (Model 1b). There were significant main effects of dSLEs predicting heavier PYDD in both men and women (Model 2b), and these effects were retained after adjusting for the main effect of maltreatment history (Model 3b). However, Maltreatment × dSLE interactions were not significant for either sex, indicating that the association between exposure to events caused in part by participant behavior and past-year drinking behavior did not vary with childhood maltreatment history (Model 4b). Consistent with the results for iSLEs, major depression symptoms were significantly associated with PYDD; however, adding past-year major depression symptoms to the model (Model 5b, Table 3) had only a trivial effect on the strength of the dSLE × Maltreatment interaction in men or women.

Discussion

Although researchers have increasingly noted the need for studies that examine the interactive effects of childhood maltreatment and proximal stressors on drinking behaviors, to our knowledge, this is the first application of the stress sensitization hypothesis to alcohol-related outcomes. The availability of a large community-based sample with detailed measures of past-year SLEs provided a unique opportunity to examine how childhood maltreatment and recent SLEs combine and interact to predict alcohol consumption. Results indicated that fateful or independent SLEs were associated with greater alcohol consumption among women exposed to childhood maltreatment. This suggests that accounting for preexisting vulnerability such as maltreatment history may help explain individual differences in stress-related drinking. Conversely, childhood maltreatment was not associated with greater stress-related drinking in the context of dependent events—those to which participants’ behavior contributed. These findings are consistent with prior research among adolescents indicating that stress sensitization effects on depression risk are stronger in association with independent than with dependent events (Harkness et al., 2006).

There are a number of potential explanations for greater stress-related alcohol consumption among individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment. These mechanisms can be usefully conceptualized as operating at several levels within brain systems as well as the level of psychological processes and psychiatric disorders. Early life stress can affect brain development in ways that increase vulnerability to substance use disorders by changing modulation of the pleasurable effects of alcohol, impairing self-regulation, and decreasing the capacity to cope with stress (Cicchetti and Toth, 2005; Clarke et al., 2008; Cole and Putnam, 1992; Hien et al., 2005; McLaughlin et al., 2010b; Spanagel, 2009). Childhood maltreatment is associated with heightened hypothalamicpituitary-adrenocortical axis response to stress in adulthood (Heim et al., 2000), potentially contributing to vulnerability for stress-related drinking among maltreated women. Moreover, childhood maltreatment may be in part a parental response to very difficult children who are emotionally labile and genetically vulnerable to stress even before maltreatment (i.e., gene–environment correlation). Early adversity might also potentiate genetic vulnerability for using alcohol to cope with subsequent stressors, and sensitization effects may also be mediated by gene–environment interactions (Enoch, 2011; Young-Wolff et al., 2011a).

Early adversity is consistently associated with maladaptive coping strategies (Bal et al., 2003; Futa et al., 2003; Leitenberg et al., 2004; Shipman et al., 2000). Poorer coping among those exposed to early maltreatment could be the direct result of abuse experiences or indirectly attributable to risk factors commonly associated with childhood maltreatment (e.g., dysfunctional family relationships, family violence, parental psychopathology, and poor parenting; Dube et al., 2001; Fergusson et al., 1996; Green et al., 2010). This constellation of risk factors likely increases exposure to unhealthy models of coping and limits opportunities for the development of adaptive coping. To the extent that other healthy coping strategies are lacking, individuals with a history of maltreatment may be particularly vulnerable to using alcohol for its reinforcing effects during times of stress. Indeed, there is some evidence that tension reduction drinking motives mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and alcohol use disorder symptoms among women (Grayson and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Schuck and Widom, 2001). From a clinical standpoint, family and school-based prevention programs that teach maltreated children self-regulation techniques and tools for coping with the aftereffects of abuse may be particularly beneficial in reducing later risk for using alcohol as a coping strategy.

Childhood maltreatment might also contribute to stress-related drinking via its effects on other forms of psychopathology. There is growing evidence that childhood adversity leads to long-lasting changes in stress reactivity that alter vulnerability to the pathogenic effects of SLEs on depression (Dienes et al., 2006; Dougherty et al., 2004; Hammen et al., 2000; Harkness et al., 2006; Kendler et al., 2004; Rudolph and Flynn, 2007). If maltreatment potentiates risk for the development of depression following subsequent SLEs, stress sensitization results for alcohol consumption could be attributable to co-occurring depression symptoms. We attempted to clarify the specificity of childhood maltreatment on risk for stress-related drinking by adjusting for past-year major depression symptoms. The regression of alcohol consumption on depression symptoms had a negligible influence on the effect sizes of Maltreatment × SLE interactions on alcohol consumption, suggesting in our sample that childhood maltreatment is associated with a liability to stress-related drinking over and above the effects of past-year major depression.

Unlike the findings for independent life events, there was a significant main effect of dependent life events on past year drinking, unrelated to history of childhood maltreatment, suggesting that a different mechanism is involved in the link between drinking and dependent events. It is consistent with the hypothesis that some dependent events are associated with drinking through reverse causation: drinking or drinking-related behavior contributing to exposure to stressors. Although these results are provocative, additional longitudinal studies are needed that investigate the dynamic nature of SLEs and alcohol consumption over time and the influence of childhood maltreatment on these processes.

Sex differences in stress sensitization

We hypothesized sex differences in stress-sensitization based on prior evidence that childhood maltreatment directly affects risk for alcohol use disorders in women (Kendler et al., 2000; Nelson et al., 2002), whereas the effects in men appear to be mediated by background environmental factors (Dinwiddie et al., 2000; Young-Wolff et al., 2011b). Our results indicated that fateful SLEs were associated with alcohol consumption only among women, but not men, exposed to childhood maltreatment. In our prior report on SLEs and early drinking onset in a subset of the current sample (Lee et al., 2012), we also found sex differences in the association between early-onset alcohol use and stress-related drinking. Although these fi ndings might suggest different etiologic pathways for stress-related drinking behaviors in men and women, as of yet the mechanisms underlying gender differences in sensitization effects are uncertain and multiple explanations are possible.

Gender differences in the interactive effects of early maltreatment and current stressors on drinking could result from variations in any of the potential mechanisms underlying stress sensitization, including alterations in stress response circuitry, use of alternative coping strategies, gene–environment interactions, and comorbid psychopathology. Gender differences may also be attributable to differences in the pattern, type, meaning, or severity of stressors. In our sample, women experienced a greater number of SLEs, and it is possible that men were not exposed to a high enough level of SLE quantity or severity to evoke or detect sensitization effects. Some support for this hypothesis comes from findings in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, which indicated that stress-sensitization effects on liability to posttraumatic stress disorder occurred in the context of fewer SLEs among women compared with men (McLaughlin et al., 2010a). Gender differences in stress sensitization might also be mediated by more severe maltreatment among women. We did not assess severity directly, but women were more likely to report each form of maltreatment (sexual abuse, physical abuse, and serious neglect). Studies with more detailed assessments of chronicity and severity of childhood maltreatment are required to evaluate this potential explanation.

We recognize that the absence of findings in men is not definitive. Stress processes on alcohol consumption may also be more difficult to detect among men because they had a lower prevalence of maltreatment and drank more heavily than women, even in the absence of SLEs. However, our sample had a greater number of men than women (75%), and the small effect sizes of maltreatment on alcohol consumption among men suggest that absence of sensitization findings among men is not completely attributable to low power. Continued study of stress sensitization may help to clarify the inconsistent literature on the relations between SLEs and alcohol-related outcomes and improve understanding of gender differences in vulnerability to stress-related drinking.

It is noteworthy that even though women exposed to childhood maltreatment and recent SLEs had heavier drinking relative to other women, overall they were still less likely to exhibit heavy drinking than men. Given that women are more vulnerable than men to both the short- and long-term adverse physiological consequences of heavy drinking (including blackouts, memory impairment, and brain and other organ damage; Mancinelli et al., 2009), a better understanding of how childhood maltreatment and other kinds of childhood trauma increase risk for stress-related drinking is important for reducing the health impact of drinking in women.

Limitations

This study should be considered in light of a number of limitations. First, our sample comprises White individuals, and future studies with more diverse samples are needed. Second, the cross-sectional nature of our analyses precludes direct investigation of causal associations between SLEs and alcohol consumption. We used event dependence as a way to examine the confounding role of an individual's behavior on their SLE exposure. Although it is possible that sensitization effects are explained by a reverse process—that heavier drinking (or greater familial liability) among women with a history of maltreatment contributed to greater SLE exposure— this mechanism is unlikely to account for sensitization effects because there was no main effect of iSLEs on alcohol consumption among women, and increased stress-related drinking associated with childhood maltreatment did not occur in the context of dependent events. Nevertheless, our measures of alcohol consumption are not timed; therefore, we cannot be sure whether drinking changed in response to occurrence of iSLEs, and our use of the term “stress-related drinking” must be interpreted within the context of this design limitation. However, it is provocative that we found an interaction between stress and maltreatment given our use of aggregate measures of past-year alcohol consumption.

Our measure of childhood maltreatment did not assess chronicity or severity of maltreatment, relationship to the abuser, or emotional abuse, and we were thus unable to investigate the importance of these dimensions of maltreatment on risk for heavy drinking. Despite this limitation, our investigation of childhood maltreatment was strengthened by the use of multiple indices (physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect) that tend to co-occur. Our inter-rater and test-retest reliabilities for SLE severity (LTCT) ratings are somewhat lower than would be desired, and the reliability and validity of our measures of childhood maltreatment, alcohol consumption, and SLE exposure are subject to biases of retrospective self-report. Available evidence indicates that retrospective reports of child abuse are likely underestimated (Della Femina et al., 1990; Fergusson et al., 2000; Green et al., 2010; Hardt and Rutter, 2004), and few reports of childhood maltreatment are false positives (Widom and Morris, 1997; Widom and Shepard, 1996). This suggests that although stress sensitization effects may be weakened by underreporting, results from the current study are not likely attributable to false-positive reports.

We examined the confounding role of past-year major depression symptoms and found that it did not account for higher rates of stress-related drinking among women with a history of childhood maltreatment. However, it is possible that other forms of comorbid psychopathology, such as anxiety syndromes, might mediate stress sensitivity results for alcohol consumption among women.

Acknowledgments

Patsy Waring, Frank Butera, Sarah Woltz, Barbara Brooke, and Lisa Halberstadt supervised data collection. Indrani Ray and Steven Aggen provided programming and database management. Linda Corey and the staff of the Mid-Atlantic Twin Registry assisted with subject identification and recruitment.

Footnotes

Data collection was supported by Grants MH/AA-49492, AA/DA-09095, and AA-00236 from the National Institutes of Health and funds from the Carman Trust and the W.M. Keck, John Templeton, and Robert Wood Johnson Foundations. Analyses supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Individual Predoctoral Fellowship F31AA018611 to K.C.Y.W. No conflict of interest exists. Portions of these results were presented as posters at the Alcoholism and Stress Conference (May 2011) and the NIH National Graduate Student Research Conference (October 2011).

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G. A prospective study of life events and psychological symptoms. Psychological Medicine. 1981;11:795–801. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700041295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bal S, Crombez G, Van Oost P, Debourdeaudhuij I. The role of social support in well-being and coping with self-reported stressful events in adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:1377–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett JF, Brief AP, Burke MJ, George JM, Webster J. Negative affectivity and the reporting of stressful life events. Health Psychology. 1990;9:57–68. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet E, Sonnega A, Kessler RC. Risk factors for DSM-IIIR posttraumatic stress disorder: Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147:353–361. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW. Life events and measurement. In: Brown GW, Harris TO, editors. Life events and illness (pp. 3–45) New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO, editors. Life events and illness. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, D, Toth, SL, editors. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. Child maltreatment. 2005;1:409–438. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke T-K, Treutlein J, Zimmermann US, Kiefer F, Skowronek MH, Rietschel M, Schumann G. HPA-axis activity in alcoholism: Examples for a gene-environment interaction. Addiction Biology. 2008;13:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Putnam FW. Effect of incest on self and social functioning: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Femina D, Yeager CA, Lewis DO. Child abuse: Adolescent records vs. adult recall. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1990;14:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90033-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dervic K, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA. Protective factors against suicidal behavior in depressed adults reporting childhood abuse. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:971–974. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243764.56192.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienes KA, Hammen C, Henry RM, Cohen AN, Daley SE. The stress sensitization hypothesis: Understanding the course of bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;95:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie S, Heath AC, Dunne MP, Bucholz KK, Madden PAF, Slutske WS, Martin NG. Early sexual abuse and lifetime psychopathology: A co-twin-control study. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:41–52. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Davila J. A growth curve analysis of the course of dysthymic disorder: The effects of chronic stress and moderation by adverse parent-child relationships and family history. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1012–1021. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Croft JB, Edwards VJ, Giles WH. Growing up with parental alcohol abuse: Exposure to childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1627–1640. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch MA. The role of early life stress as a predictor for alcohol and drug dependence. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:17–31. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1916-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espejo EP, Hammen CL, Connolly NP, Brennan PA, Najman JM, Bor W. Stress sensitization and adolescent depressive severity as a function of childhood adversity: A link to anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:287–299. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Life events and depression in women: A structural equation model. Psychological Medicine. 1984;14:881–889. doi: 10.1017/s003329170001984x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Woodward LJ. The stability of child abuse reports: A longitudinal study of the reporting behaviour of young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:529–544. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: I. Prevalence of sexual abuse and factors associated with sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1355–1364. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199610000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DD, Caldji C, Champagne F, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor–norepinephrine systems in mediating the effects of early experience on the development of behavioral and endocrine responses to stress. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:1153–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futa KT, Nash CL, Hansen DJ, Garbin CP. Adult survivors of childhood abuse: An analysis of coping mechanisms used for stressful childhood memories and current stressors. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Wheeler R, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Emotional, physical, and sexual maltreatment in childhood versus adolescence and personality dysfunction in young adulthood. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15:505–511. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.6.505.19194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser JP, van Os J, Portegijs PJ, Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: Associations with fi rst onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Henry R, Daley SE. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:782–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Bruce AE, Lumley MN. The role of childhood abuse and neglect in the sensitization to stressful life events in adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:730–741. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, Nemeroff CB. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Wagner D, Wilcox MM, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. The role of early adverse experience and adulthood stress in the prediction of neuroendocrine stress reactivity in women: A multiple regression analysis. Depression and Anxiety. 2002;15:117–125. doi: 10.1002/da.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien D, Cohen L, Campbell A. Is traumatic stress a vulnerability factor for women with substance use disorders? Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:813–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Stressful life events and major depression: Risk period, long-term contextual threat, and diagnostic specifi city. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186:661–669. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. The assessment of dependence in the study of stressful life events: Validation using a twin design. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:1455–1460. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798008198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1475–1482. doi: 10.1017/s003329170400265x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Genes, environment and psychopathology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hasin DS. Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: The epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L, Kendler KS, Young-Wolff KC, Prescott CA. The effects of age at drinking onset and stressful life events on alcohol use in adulthood: A replication and extension using a population-based twin sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:693–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitenberg H, Gibson LE, Novy PL. Individual differences among undergraduate women in methods of coping with stressful events: The impact of cumulative childhood stressors and abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Caldji C, Sharma S, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Infl uence of neonatal rearing conditions on stress-induced adrenocorticotropin responses and norepinephrine release in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2000;12:5–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancinelli R, Vitali M, Ceccanti M. Women, alcohol and the environment: An update and perspectives in neuroscience. Functional Neurology. 2009;24:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine. 2010a;40:1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, Sheridan MA, Marshall P, Nelson CA. Delayed maturation in brain electrical activity partially explains the association between early environmental deprivation and symptoms of attention-defi cit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2010b;68:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Mechanisms linking stressful life events and mental health problems in a prospective, community-based sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hilt LM. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Brake W, Gratton A. Environmental regulation of the development of mesolimbic dopamine systems: A neurobiological mechanism for vulnerability to drug abuse? Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Ciesla JA, Garber J. A prospective study of stress autonomy versus stress sensitization in adolescents at varied risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:341–354. doi: 10.1037/a0019036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PAF, Cooper ML, Dinwiddie SH, Bucholz KK, Martin NG. Association between selfreported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes: Results from a twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:139–145. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC. Adulthood stressors, history of childhood adversity, and risk of perpetration of intimate partner violence. American Journal of PreventiveMedicine. 2011;40:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M. Childhood adversity and youth depression: Infl uence of gender and pubertal status. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:497–521. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck AM, Widom CS. Childhood victimization and alcohol symptoms in females: Causal inferences and hypothesized mediators. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1069–1092. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman K, Zeman J, Penza S, Champion K. Emotion management skills in sexually maltreated and nonmaltreated girls: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:47–62. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showers CJ, Zeigler-Hill V, Limke A. Self-structure and childhood maltreatment: Successful compartmentalization and the struggle of integration. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:473–507. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Miller WR. Concomitance between childhood sexual and physical abuse and substance use problems: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:27–77. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R. Alcoholism: A systems approach from molecular physiology to addictive behavior. Physiological Reviews. 2009;89:649–705. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Topitzes J, Mersky JP, Reynolds AJ. Child maltreatment and adult cigarette smoking: A long-term developmental model. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:484–498. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M, Geschwind N, Jacobs N, Kenis G, Peeters F, Derom, C, van Os J. Transition from stress sensitivity to a depressive state: Longitudinal twin study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195:498–503. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.056853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Morris S. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization, Part 2: Childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Shepard RL. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: Part 1. Childhood physical abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Young-Wolff KC, Enoch MA, Prescott CA. The infl uence of gene-environment interactions on alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders: A comprehensive review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011a;31:800–816. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young-Wolff KC, Kendler KS, Ericson ML, Prescott CA. Accounting for the association between childhood maltreatment and alcohol-use disorders in males: A twin study. Psychological Medicine. 2011b;41:59–70. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinski DS. Child maltreatment and adult socioeconomic wellbeing. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:666–678. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]