Abstract

Objective

To assess how age-related social comparisons, which are likely to arise inadvertently or deliberately during assessments, may affect older people's performance on tests that are used to assess their needs and capability.

Design

The study randomly assigned participants to a comparison with younger people or a no comparison condition and assessed hand grip strength and persistence. Gender, education, type of residence, arthritis and age were also recorded.

Setting

Age UK centres and senior's lunches in the South of England.

Participants

An opportunity sample of 56 adults, with a mean age of 82.25 years.

Main outcomes measures

Hand grip strength measured using a manual hand dynamometer and persistence of grip measured using a stopwatch.

Results

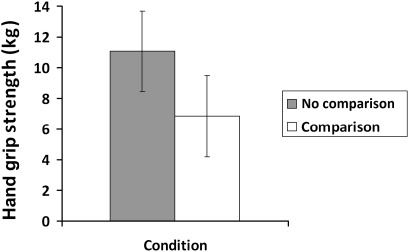

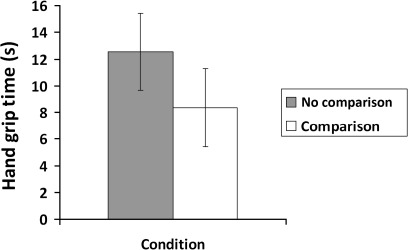

Comparison caused significantly worse performance measured by both strength (comparison =6.85 kg, 95% CI 4.19 kg to 9.5 kg, control group =11.07 kg, 95% CI 8.47 kg to 13.68 kg, OR =0.51, p=0.027) and persistence (comparison =8.36 s, 95% CI 5.44 s to 11.29 s; control group =12.57 s, 95% CI 9.7 s to 15.45 s, OR =0.49, p=0.045). These effects remained significant after accounting for differences in arthritis, gender, education and adjusting for population age norms.

Conclusions

Due to the potential for age comparisons and negative stereotype activation during assessment of older people, such assessments may underestimate physical capability by up to 50%. Because age comparisons are endemic, this means that assessment tests may sometimes seriously underestimate older people's capacity and prognosis, which has implications for the way healthcare professionals treat them in terms of autonomy and dependency.

Article summary

Article focus

What is the relationship between ageing and physical strength, measured by hand grip?

Does stereotype threat affect older people's physical capacities?

Substantial variability in diagnosis of physical strength could be caused by inadvertent invocation of age stereotypes during assessment.

Key messages

Psychosocial factors may influence how strongly physical effects of ageing manifest themselves.

Age comparison creates a stereotype threat, which can reduce older people's hand grip strength by up to 50%—as large as the normal range from middle to old age.

Healthcare professionals should be aware of the potential for age comparison and stereotypes to affect outcomes of assessments of older people.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Hand grip is an ‘objective measure’ of physical capability among older people. It is predictive of frailty, morbidity, disability and mortality.

This first experimental test of the impact of age comparison on older people's hand grip strength demonstrates that it is impaired by comparison with younger people.

This research was conducted in a non-medical setting and involved participants in good health with a small convenience sample. However the effects remain significant even when age, gender, education, degree of arthritis in the hands, type of residence and location of testing are accounted for.

Further research is needed to evaluate the prevalence of age comparisons in clinical testing settings, and effects on people of different ages.

Physical and mental decline is often seen as an inevitable part of ageing.1 2 However, expectation of decline may be based, at least in part, on negative stereotypes3 4 and media images of ageing, which often dwell on issues such as degenerative disease, illness and dependency in later life.5 Physical decline may be made even more salient by comparison with younger people, whose idealised media presentations convey super fitness and strength.6 We contend that such comparisons, which may be prevalent in situations in which older people are clinically evaluated, can ironically result in behavioural confirmation of their own physical decline.

In medical and healthcare settings, older adults may frequently encounter situations in which they feel that they may be judged in terms of their age or confirm negative age stereotypes. For instance, age is a salient factor in many doctor–patient interactions; age thresholds may often be used as relevant cues or eligibility criteria for assessing an individual's need for treatment or care. Subtle age cues also exist as healthcare professionals are likely to be younger than the retired patients they are treating. Moreover, there is often a degree of age segregation in hospitals, with specific wards for children and older patients in geriatric wards. These factors may raise the possibility for social comparisons and the salience of age-related stereotypes, which may be damaging to older people's cognitive and physical functioning.7

Detrimental impacts of unconscious negative age stereotypes have been assessed on a number of behavioural and functional outcomes,8 including older people's memory performance,9 10 handwriting,11 time to complete action sequences12 and physiological responses to stress.13 14 Importantly, subtle but more explicit and ecologically relevant influences can affect older people's cognitive performance via social comparisons.

Previous research has shown that older people's (aged 58 years and older) cognitive ability and performance on mathematical tasks can be impaired if they are told prior to the testing situation that their performance will be compared with younger people.15 16 This age-related social comparison raises awareness of negative stereotypes of ageing regarding the relative incompetence of older people in comparison with younger people, which leads to behavioural confirmation of age stereotypes and a deficit in cognitive performance. These and other studies17 establish that the threat of being stereotyped negatively can have adverse effects on the cognitive and memory performance of older people. This has particular relevance for understanding, diagnosing and treating diseases, with evidence to suggest that negative age stereotypes may have significant harmful effects on people with Alzheimer's disease.18 However, the aim of the present research was to move beyond tests of relatively complex cognitive ability to see whether social comparison can affect basic physical capacity. Unlike cognitive ability, physical ability can be observed directly and is manifest when people engage in everyday tasks. Negative stereotypes of ageing assume inevitable physical decline, reflected by incapability, frailty, weakness, sickness, helplessness and dependency.19 Therefore, it seems probable that situations that involve social comparison with younger people have the potential to trigger behavioural confirmation of physical decline among older people. We hypothesised that age-based social comparison would affect physical performance even in a task that requires little or no skill.

Hand grip dynamometry

To test this idea, the present study investigates the impact of a social comparison with younger people on older people's hand grip strength and persistence, a measure of physical capability. Although grip strength requires little or no skill, it is an index of a person's ability to do many everyday activities, ranging from opening a door to writing, carrying bags and opening jars and cans. Importantly, grip strength dynamometry is a widely used diagnostic measure of individual disability/capability, muscle strength and functionality because it serves as a simple and reliable indicator of an individual's strength and persistence.20

Hand grip declines by up to 50% between the ages of 25–29 and 75+ years,20 and much of this decline happens after the age of 50.21 Hand grip strength has been shown to be an important predictor of disability in later life.22 23 A meta-analysis of 13 studies (with a total N =44 636) found that high grip strength was associated with lower subsequent mortality, controlling for age, gender and body weight (also apparent in a meta-analysis of a further 14 studies, N =53 476).24 Given the substantive importance of hand grip strength as a clinical indicator, it is important to know whether it can be influenced by psychosocial factors.

We contend that a social comparison with younger people prior to the testing situation should impair older people's physical performance on the hand dynamometer (representing hand grip strength). Moreover, because the ageing stereotype implies reductions in both strength and stamina, we expect the participants in the comparison condition to be less persistent, as measured by how long participants can hold the hand dynamometer at their maximum level.

Methods

Design and participants

Managers of 15 Age UK centres and senior's lunches in the South East of England were contacted to arrange visits to conduct the study. Eleven agreed, and 56 participants (36 women) took part from these organisations. Participants were aged between 67 and 98 years (M =82.25, SD =7.21). All participants considered themselves mentally and physically well at the time of the study. The majority of participant's lived independently in their own home.

Materials and procedure

Potential participants were approached at social activities organised by the different centres. Testing was conducted individually by three female experimenters in their mid-20s. Volunteers were tested in sequence though not all could be tested in cases when they had to leave prior to a testing session becoming available. No testing sessions were unfilled. In order to avoid participants becoming aware of the study design and hypotheses prior to participation, all testing was restricted to one morning in any one centre. In practice, this allowed testing of no more than seven participants. Participants were tested in a private area and were randomly assigned to condition by flip of a coin. Condition was evenly assigned across both gender and testing location (p=0.86 and 0.96, respectively). Procedures complied with British Psychological Society Ethical Guidelines and were approved by the School of Psychology Ethics Panel. Participants gave informed consent and were free to withdraw from the study at any time. All were fully debriefed in writing at the end.

The comparison condition procedure followed previous research,15 informing participants that “the purpose of this research is to see whether older people perform differently on various tasks and the ways in which they deal with the world in comparison with young people. Both older and young people will be taking part in this research.” In the control condition, participants were merely informed that “The purpose of this research is to see how people deal with the world and how they perform on various tasks.” A manual hand dynamometer, held horizontally, was used to measure grip strength in kilograms. While sitting, participants were instructed to “please squeeze this handle as hard as you can, for as long as you can.” Grip strength was measured in kilograms, three times with a 30-s recovery period between trials. The maximum strength-level and time in seconds (from start to finish) were recorded on each trial. After the trials, participants were interviewed to record their age (in years), gender (coded 1= female, 2= male), residence (own home vs other, coded 0 and 1, respectively) and education level (age left full-time education). Because arthritis can affect grip strength,25 participants were asked whether they, ‘suffer from arthritis in the hands’ (responding, ‘Yes, severely’, ‘Yes, mildly’, ‘Yes, very slightly’ or ‘No, not at all’, coded 1 to 4, respectively).

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using SPSS V.18.0, and p<0.05 was used as a criterion for statistical significance. After removing a single outlier from the comparison condition (3 SDs from mean on all trials), preliminary analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 analyses were conducted to establish whether participant demographics, including age, gender, type of residence and education level, were randomly distributed across condition. Descriptive statistics were used to inspect the distribution of scores on the grip strength (in kilograms) and persistence (in seconds). Correlation analyses were used to investigate relationships among measured variables. We then used ANOVA to evaluate the effect of condition on strength and persistence and followed-up with analyses that treated arthritis, demographics and age and gender grip strength norms as covariates. Finally, because participants were nested within locations, we conducted a multilevel analysis including location as a random intercept.

Results

Participant demographics did not vary significantly by condition nor did the severity of participants' arthritis (table 1). Across conditions, hand grip persistence ranged from 0 to 48 s and grip strength ranged from 0 to 28.4 kg. The three grip strength scores correlated highly and formed a reliable measure (Cronbach's α =0.96) as did the persistence times (Cronbach's α =0.91). Average scores were computed for both hand grip persistence and strength across the three trials.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants assigned to the comparison and control groups, and group difference determined by a one-way analysis of variance (95% CI)

| Characteristic | Comparison group, mean (SD) (n=27) | Control group, mean (SD) (n=28) | F or χ2 | (P) df=1,53 |

| Age (years) | 83.15 (7.38) | 82.07 (6.94) | F =0.31 | 0.58 |

| Gender | 18 F, 9 M | 18 F, 10 M | χ2 =0.3 | 0.86 |

| Education (school leaving age) | 15.26 (1.83) | 15.29 (1.63) | F =0.003 | 0.96 |

| Type of residence | H 22, R 5 | H 22, R 6 | χ2 =0.33 | 0.57 |

| Self-reported arthritis | 3.37 (0.97) | 3.32 (1.06) | F =0.03 | 0.86 |

df, degrees of freedom; F, female; H, own home; M, male; R, other residence.

Strength and persistence were quite highly correlated (r =0.51, p<0.001). Participants who reported more arthritis had significantly lower grip strength (r =0.30, p<0.05). Strength and persistence were not significantly related to age, gender or educational level. Bivariate relationships among the variables are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Means, SDs and correlations among variables

| Variable | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | M | SD |

| 1. Age | −0.19 | −0.11 | −0.17 | 0.11 | −0.14 | −0.09 | 82.60 | 7.11 |

| 2. Gender | 0.18 | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 36F, 19M | ||

| 3. Education | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 15.27 | 1.72 | ||

| 4. Arthritis | −0.03 | 0.30* | 0.20 | 3.35 | 1.00 | |||

| 5. Residence | 0.09 | 0.25 | 44 H, 10 R | |||||

| 6. Grip strength (kg) | 0.51*** | 9.00 | 7.42 | |||||

| 7. Grip persistence (s) | 10.51 | 7.81 |

All Pearson product moment correlation r unless specified otherwise.

*p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

M, mean.

Age comparison and physical performance

Differences between the comparison and no comparison condition were analysed using ANOVA. We hypothesised that comparison with the young should lead to impaired physical performance. As shown in table 3, the effect of condition on mean strength was significant (p=0.038; comparison M =6.9, 95% CI 4.13 to 9.68; control M =11.02, 95% CI 8.29 to 13.74). The OR is 0.51, meaning that performance is reduced by almost half by the presence of a comparison.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance results for effect of condition (comparison vs control) on hand grip strength and persistence (95% CI)

| Comparison group | Control group | Significance |

||||

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | df | F | P | η2 | |

| Grip strength (kg) | ||||||

| Basic model (no covariates) | 6.9 (1.38) | 11.02 (1.36) | 1,53 | 4.51 | 0.038 | 0.078 |

| Strength adjusting for self-reported arthritis | 6.85 (1.32) | 11.07 (1.3) | 1,52 | 5.21 | 0.027 | 0.091 |

| Strength adjusting for age and gender norms, education level, residence and arthritis | 6.86 (1.46) | 11.07 (1.31) | 1,48 | 4.73 | 0.035 | 0.090 |

| Grip persistence (s) | ||||||

| Basic model (no covariates) | 8.36 (1.46) | 12.57 (1.43) | 1,53 | 4.23 | 0.045 | 0.074 |

| Persistence adjusting for self-reported arthritis | 8.32 (1.44) | 12.61 (1.41) | 1,52 | 4.52 | 0.038 | 0.038 |

| Persistence adjusting for age and gender norms, education level, residence and arthritis | 8.33 (1.46) | 12.61 (1.44) | 1,48 | 4.64 | 0.036 | 0.09 |

There is a significant effect of self-reported arthritis on grip strength (F=6.08, df =1,52, P=0.017, η2=0.105) but not for persistence (F=2.52, df=1,52, P=0.12, η2=0.046).

η2, effect size estimate; df, degrees of freedom.

Because arthritis also affected strength, we used it as a covariate in the second analysis. The analysis confirmed that there was a significant effect of arthritis (p=0.017), but importantly, there remained a significant effect of comparison on grip strength (p=0.027; see figure 1). Hand grip strength was worse for those in the comparison group (6.85, 95% CI 4.19 to 9.5) compared with those in the control group (11.07, 95% CI 8.47 to 13.68). Figure 2 shows the similar significant effect of condition on grip persistence (p=0.045), with those in the comparison group showing less persistence (8.36, 95% CI 5.44 to 11.29; 12.57, 95% CI 9.7 to 15.45, respectively, OR =0.49). When arthritis was included as a covariate, there was no significant effect of arthritis and the effect of comparison remained significant (p=0.038; comparison M =8.32, 95% CI 5.44 to 11.21; control M =12.61, 95% CI 9.78 to 15.45).

Figure 1.

Physical strength as a function of condition (self-reported arthritis is a covariate) showing means and 95% CIs.

Figure 2.

Hand grip persistence as a function of condition (self-reported arthritis is a covariate), showing means and 95% CIs.

Controlling for demographic variables and norms

National21 26 and international27 age and gender norms for hand grip strength show that men have higher strength and that strength decreases between the ages of 50 and 90 years. Because the participants in this study did not represent a random sample of the population, it seemed appropriate to determine whether comparison affected their performance after adjusting for the national age and gender norm for each participant. To be as conservative as possible, we included the age and gender international hand strength norms along with educational level, residence and arthritis as covariates in an analysis of covariance. As shown in table 3, the effects of comparison remained significant (>33% reduction) on both strength (p=0.036; comparison estimated M =6.86, 95% CI 4.18 to 9.53; control estimated M =11.07, 95% CI 8.44 to 13.69) and persistence (p=0.037; comparison estimated M =8.33, 95% CI 5.37 to 11.27; control estimated M =12.61, 95% CI 9.72 to 15.49).

To see whether this comparison specific to age was operating in the comparison versus control condition, we inspected the partial correlation between age and grip strength, controlling for age and gender strength norms, education and arthritis scores. This revealed that although grip strength was significantly negatively related to age in the comparison condition (r = −0.47, p<0.05), it was unrelated to age in the control condition (r =0.14, p=0.50). These two correlations differed significantly, Z =1.97 (p<0.05). This demonstrates that in the comparison condition performance declined strongly with age. In the control condition, it did not. Finally, the multilevel analysis confirmed that the effects of condition remained significant, and the F and p values for both strength and persistence remained essentially identical after the variance due to location was accounted for.

Discussion

This study establishes new findings that demonstrate the importance of social comparisons when assessing older adults' physical capability. It shows that social comparison with younger people can impair performance, by up to 50%, on an objective measure of strength that is, used in both clinical and non-clinical assessment of older people. This evidence complements and extends previous research that suggests that the threat of being stereotyped negatively can have adverse effects on older people's cognitive performance,15–17 both strength and persistence on the hand grip task were significantly impaired by the presence of an age comparison. Moreover, even after controlling for other potentially contributory variables, this difference remained significant. Finally, the fact that the impairment was stronger among older people is consistent with the interpretation that the comparison induced them to focus on negative expectations about their age. Strikingly, the introduction of a social comparison with younger people was sufficient to cause as large a drop in mean physical performance (grip strength) as is observed in population means between the ages of 25 and 75 years21 or between the ages of 55 and 85 years.27 It is as if the effect of ageing has been doubled. Because we tested across several locations, there is some variation due to location, but the multilevel analysis revealed that this did not reduce the effect of condition, suggesting that the effects are not likely to be underestimated due to type 1 error.

A social comparison with younger people creates a threatening stereotypic expectancy that leads to underperformance and less persistence on the hand grip task. Given that age-based comparisons are frequent, if not endemic, in everyday life,3 it is likely that older people may quite often find themselves facing negative age comparisons, and consequently, many may also perform everyday physical tasks suboptimally, and appear, and believe that they are more dependent on help than is actually necessary.

Implications

An important question arising from this research is how the impairing effects of age comparisons might be mitigated. People of all ages are aware of negative stereotypes of older people's competence and capability.3 Research suggests that negative social comparisons have a larger impact on the cognitive performance of people who identify strongly with the stereotyped group.28 However, effects can be reduced if people can view themselves as part of other groups.29 In the case of older people, evidence shows that those who have closer friendships with younger people are less vulnerable to age comparisons.15 16 This seems to occur because older people who have more social contact with younger people view the two groups as less distinct. One of the factors that is likely to affect older people's vulnerability to age comparisons is the extent to which age segregation makes them aware of being part of a ‘different’ group from younger people. When comparisons are made, these differences may spring to mind more readily, resulting in behaviour that further reinforces negative stereotypes.

The findings raise a particular concern for older people who are likely to undergo evaluations or competency tests, for the purposes of medical, employment or insurance, or social care and support assessments. Previous research has shown the potential negative effects that stereotypes can have on levels of dependency in later life.30 One damaging consequence of an assessment that implicitly or explicitly uses ‘when you were younger’, or an age threshold (eg, ‘now that you are over 65’) as a reference point, may be that it actively induces social comparisons and negative age stereotypes and causes older people to present as less physically able than they really are. This in turn could foster a cycle of increasing dependency and withdrawal from physical tasks. Even among individuals who regard themselves as physically fit, negative stereotypes associated with older people's general physical decline may have adverse effects. For example, in the present research, the comparison affected participants regardless of whether they experienced arthritis. The finding that a simple social comparison can ostensibly reduce an older person's physical strength by as much as half indicates that it needs to be taken seriously as a factor in clinical diagnosis and assessment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Swift HJ, Lamont RA, Abrams D. Are they half as strong as they used to be? An experiment testing whether age-related social comparisons impair older people's hand grip strength and persistence. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001064. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001064

Contributors: DA supervised the research, HJS conceived the idea for the experiment and together with RAL conducted the experiment. All authors contributed to data analysis and writing of the article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council and by Age UK. The authors are independent of the funders.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Participants signed an informed consent form. They were not patients and were not tested in a medical setting.

Ethics approval: The ethics approval was provided by School of Psychology Ethics Panel, University of Kent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from the Dryad repository, doi:10.5061/dryad.sp0ts0hc.

References

- 1.Timiras PA, ed. Physiological Basis of Aging and Geriatrics. New York: CRC Press, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychol Rev 1996;103:403–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams D, Russell PS, Vauclair M, et al. Ageism in Europe: Findings From the European Social Survey. Age UK, 2011. http://www.ageuk.org.uk/Documents/EN-GB/For-professionals/ageism_across_europe_report_interactive.pdf?dtrk=true (accessed Feb 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuddy AJC, Norton MI, Fiske ST. This old stereotype: the pervasiveness and persistence of the elderly stereotype. J Soc Issues 2005;61:267–85 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkinson J, Ferraro K. Thirty years of ageism research. In: Nelson TD, ed. Ageism: Stereotyping and Prejudice Against Older Persons. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002:247–76 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murnen SK, Smolak L, Mills JA, et al. Thin, sexy women and strong, muscular men: grade-school children's responses to objectified images of women and men. Sex Roles 2003;49:427–37 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahana B, Kahana E. Changes in mental status of elderly patients in age-integrated and age-segregated hospital milieus. J Abnorm Psychol 1970;75:177–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meisner BA. A meta-analysis of the positive and negative age stereotype priming effects on behavior among older adults. J Gerontol B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2012;67B:13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy B. Improving memory in old age through implicit self-stereotyping. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;71:1092–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein R, Blanchard-Fields F, Hertzog C. The effects of age stereotype priming on the memory performance of older adults. Exp Aging Res 2002;28:169–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy B. Handwriting as a reflection of aging self-stereotypes. J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;33:81–94 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banfield JF, Pendry LF, Mewse AJ, et al. The effects of an elderly stereotype prime on reaching and grasping actions. Soc Cogn 2003;21:299–319 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auman C, Bosworth HB, Hess TM. Effect of health-related stereotypes on physiological responses of hypertensive middle-aged and older men. J Gerontol: Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005;60B:P3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy BR, Hausdorff JM, Hencke R, et al. Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of aging. J Gerontol: Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2000;55:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abrams D, Crisp RJ, Marques S, et al. Threat inoculation: experienced and imagined intergenerational contact prevents stereotype treat effects on older people's maths performance. Psychol Aging 2008;23:934–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrams D, Eller A, Bryant J. An age apart: the effects of intergenerational contact and stereotype threat on performance and intergroup bias. Psychol Aging 2006;21:691–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hess TM, Auman C, Colcombe SJ, et al. The impact of stereotype threat on age differences in memory performance. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2003;58:P3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholl JM, Sabat SR. Stereotypes, stereotype threat and ageing: implications for the understanding and treatment of people with Alzheimer's disease. Ageing Soc 2008;28:103–30 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hummert ML. Multiple stereotypes of elderly and young adults: a comparison of structure and evaluations. Psychol Aging 1990;5:182–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohannon RW, Peolsson A, Massy-Westropp N, et al. Reference values for adult grip strength measured with a Jamar dynamometer: a descriptive meta-analysis. Physiother 2006;92:11–15 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathieowetz V, Kashman N, Volland G, et al. Grip and pinch strength: normative data for adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1985;66:69–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D, et al. Midlife handgrip strength as a predictor of old age disability. JAMA 1999;281:558–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taekema DG, Gussekloo J, Maier AB, et al. Handgrip strength as a predictor of functional, psychological and social health. A prospective population-based study among the oldest old. Age Ageing 2010;39:331–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper R, Kuh D, Hardy R. Objectively measured physical capability levels and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraser A, Vallow J, Preston A, et al. Predicting ‘normal’ grip strength for rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:521–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skelton DA, Greig CA, Davies JM, et al. Strength, power and related functional ability of healthy people aged 65-89 years. Age Ageing 1994;23:371–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson-Ransberg K, Petersen I, Frederiksen H, et al. Cross-national differences in grip strength among 50+ year-old Europeans: results from the SHARE study. Eur J Ageing 2009;6:227–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shih M, Pittinsky TL, Ambady N. Stereotype susceptibility: identity salience and shifts in quantitative performance. Psychol Sci 1999;10:80–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenthal HE, Crisp RJ. Reducing stereotype threat by blurring intergroup boundaries. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2006;32:501–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coudin G, Alexopoulos T. ‘Help me! I'm old!’ How negative aging stereotypes create dependency among older adults. Aging Ment Health 2010;14:516–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.