Abstract

Objectives

Animal studies and clinical trials have examined the potential benefits of statins in asthma management with contradictory results. The objective of this study was to determine if asthma patients on concurrent statins are less likely to have asthma-related hospitalisations.

Design

A retrospective cohort study using Mississippi Medicaid data for 2002–2004.

Participants

Asthma patients ≥18 years were identified using the ICD9 code 493.xx from 1 July 2002 through 31 December 2003. The index date for an exposed subject was any date within the identification period, 180 days prior to which the subject had at least one inhaled corticosteroid prescription and at least an 80% adherence rate to statins. Asthma patients on inhaled corticosteroids, but not on statins, were selected as the unexposed population. The two groups were matched and followed for 1 year beginning the index date.

Main outcomes measures

Patient outcomes in terms of hospitalisations and ER visits were compared using conditional logistic regression.

Results

After matching, there were 479 exposed subjects and 958 corresponding unexposed subjects. The odds of asthma-related hospitalisation and/or emergency room (ER) visits for asthma patients on concurrent statins were almost half the odds for patients not on statins (OR=0.55; 95% CI (0.37 to 0.84); p=0.0059). Similarly, the odds of asthma-related ER visits were significantly lower for patients on statins (OR=0.48; 95% CI (0.28 to 0.82); p=0.0069).

Conclusion

The findings suggest beneficial effects of statins in asthma management. Further prospective investigations are required to provide more conclusive evidence.

Article summary

Article focus

Statins have been shown to have promising therapeutic potential in mediating anti-inflammatory processes in animal model studies as well as clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune encephalomyelitis, inflammatory colitis and psoriasis.

Along the same line of reasoning, recently there has been some discussion regarding the use of statins in asthma management in addition to inhaled corticosteroid therapy.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the beneficial effects of statins on asthma outcomes using the Mississippi Medicaid claims database.

Key messages

The findings suggest that statins may be beneficial in asthma management.

The study accounts for several additional potential confounders not previously explored in the other observational studies.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study uses a propensity score-matched cohort study design, which in itself should take into account potential confounding effects.

The study was conducted using Medicaid claims data, and therefore, there is a possibility of misclassification due to coding errors during claims processing.

Introduction

Inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzymes A (HMG CoA) reductase, that is, statins are conventionally prescribed as anti-hyperlipidemics. In the past decade, they have been shown to have promising therapeutic potential in mediating inflammatory processes.1–5 Statins have been shown to be effective in animal model studies as well as clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis,6–8 autoimmune encephalomyelitis,9 10 inflammatory colitis11 12 and even psoriasis13 due to their anti-inflammatory properties. A recent observational study reported a striking 41% reduction in mortality (OR, 0.59; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.92) in persons on statins either prior to or during hospitalisation with influenza infection.14 Given this, there has been some discussion pertaining to the use of statins in the management of asthma.15–19

Animal model studies using rats suggest that systemic lovastatin inhibits antigen-induced bronchial smooth muscle hyper-responsiveness.20 It also reduces the increased cell number in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids and histological changes induced by antigen exposure. Levels of immunoglobulin E in sera and interleukins -4, -6 and -13 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluids did not change significantly. Similar experiments have been conducted with mice21 22 with findings that support the beneficial role of statins in asthma management. The proposed mechanism of action for this observation is that statins inhibit the geranylgeranylation of a monomeric GTP-binding protein RhoA and its downstream metabolites, which are involved in the agonist-induced Ca2+ sensitisation of airway smooth muscle contraction. The RhoA/RhoA kinase pathway is now being investigated as the new target for the treatment of airway hyper-responsiveness. A study conducted by McKay and colleagues23 showed the inhibitory effects of simvastatin on inflammatory cell infiltration in a murine model of allergic asthma. Similar experiments have been conducted with pravastatin and simvastatin, the results of which suggest asthma management to be an emerging indication for statins.24–26

Apart from the animal model studies described above, four small-scale clinical trials have been conducted with mixed results. A randomised double-blind crossover placebo-controlled trial investigated the effect of oral atorvastatin on measures of asthma control and airway inflammation.27 The trial included 54 adults with allergic asthma receiving inhaled corticosteroids alone. The authors found no clinically important improvements in a range of clinical indices of asthma control measures despite expected changes in serum lipids. They concluded that statins were ineffective for the short-term therapy of asthmatic inflammation. However, a change in the airway inflammation as well as a reduction in the sputum macrophage count was observed indicating that statins could have beneficial effects in other chronic lung diseases. A similar clinical trial with oral simvastatin was conducted using 16 patients with asthma whereby the authors found no improvement in asthma symptoms, pulmonary function or measures of asthmatic inflammation.28 Two other clinical trials showed improvements in asthma symptoms, lung function and sputum eosinophil counts in subjects on statins.29 30 A recent study of short-term treatment with atorvastatin in 71 smokers with asthma failed to show improvements in lung function but may have improved their asthma quality of life score.31 Given the small samples and contradicting conclusions of the above studies, these results should be interpreted cautiously.

Stanek and colleagues32 conducted the first observational study using the Medco National Integrated Database to explore the relationship between statin treatment and asthma. A total of 6574 inhaled corticosteroid-treated adult asthmatics were studied. Statin exposure was independently associated with a significant 33% reduction in recurrent asthma-related hospitalisation/ER visits over 12 months (OR, 0.67; 95% CI 0.58 to 0.76; p<0.0001). A recent study using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Database found statin use in patients with asthma to be independently associated with the decreased risk of hospitalisation due to asthma (HR, 1.02; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.03; p<0.001).33

The contradicting results between small clinical trials and larger observational studies clearly suggest that more studies investigating the potential role of statins in the management of asthma are required to make any clinical or policy-guiding decisions. The purpose of this study was to investigate the beneficial effects of statins on asthma outcomes using the Mississippi Medicaid claims database. The various animal model studies and clinical trials described above show varying results and have their own limitations. Another observational study using a different data set is economically more feasible and provides us with an overview of the situation in the real-world setting. This study uses a propensity score-matched cohort study design, which in itself should take into account confounding effects due to the variables used to compute the propensity scores.34 Prior hospitalisations, ER and office visits due to asthma, adherence to inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) medications and average number of short-acting β agonists during the study period were used to compute the propensity scores. These had not been taken into account in the earlier observational studies. Prior hospitalisations due to asthma and average number of short-acting β agonists can be an indicator of the severity of the disease, whereas non-compliance to the medications is a potential confounder as it could lead to hospitalisation/ER visits.

Methods

Data source

For the purpose of the study, the 2002–2004 Mississippi Medicaid claims data were analysed. Medicaid is a federal programme that provides healthcare coverage to many of the most vulnerable populations in the USA, including low-income children and their parents, low-income elderly, pregnant women with low family income and the disabled poor. The claims data for each year are comprised of a Person Summary File and four Claims Files—inpatient (IP), institutional long-term care (LT), prescription drug (RX) and other services (OT). The Person Summary File includes person-level data on eligibility, demographics, managed care enrolment, a summary of utilisation and Medicaid payment by type of service. Each observation in the claims files represents a transaction or record of the charges and payments made to the healthcare provider for the services rendered to the Medicaid enrollee, including details such as the date of service, expenditures for utilised services, associated diagnostic information and provider and procedure type. The Person Summary File has a record for every individual enrolled in the programme at anytime during the year; however, the claims files may have more than one or no records for each Medicaid beneficiary depending on his/her utilisation of services. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Mississippi and use of the data was approved by a data use agreement finalised by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Study design and sample

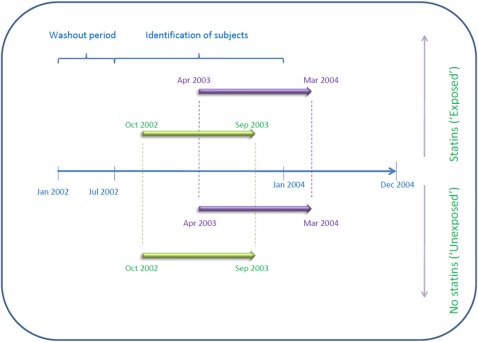

A retrospective cohort design was utilised. The study involved analysis of the Medicaid beneficiary claims from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2004. It is important to note that because the study period under consideration is prior to the implementation of Medicare Part D, the database does include prescription claims for Medicaid-eligible patients aged 65 years and older. Asthmatic adults above 18 years of age were identified using the ICD9 code 493.xx, within the 18-month identification period starting 1 July 2002 and concluding 31 December 2003 as graphically represented in figure 1. The index date for a particular subject in the exposed group was any date within the identification period, 6 months prior to which the subject had at least one prescription for an ICS, at least an 80% adherence rate to statins (ie, proportion of days covered ≥0.8), in addition to already having been diagnosed as having asthma. The subjects on statin and ICS therapy were identified using the National Drug Codes for these drugs, respectively. A total of 589 beneficiaries were initially identified to be in the exposed group. Similarly, Medicaid beneficiaries identified as asthmatics and on ICS therapy were selected as the unexposed population with the only difference being that these patients were not on concurrent statin therapy.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the study design.

The study design included a washout period from 1 January 2002 to 31 June 2002 in order to track the prescription records of patients identified and included in the study. The 589 subjects in the exposed group were initially matched to a pool of 7390 subjects in the unexposed group using propensity scores (within a range of ±0.005) computed using the covariates described later. Each exposed subject was matched to 10 corresponding subjects from the unexposed group; following which the unexposed subjects were assigned the index date of the exposed subjects they were matched to. This was done in order to maximise the number of exposed subjects that had at least two corresponding subjects from the unexposed group with an ICS prescription 6 months prior to the index date and were eligible throughout the same period. Following these procedures, 479 exposed subjects were obtained, along with corresponding 958 unexposed subjects. A detailed flow diagram representing subject selection can be found in figure 2. The two cohorts were then followed for a period of 1 year beginning the index date, and their outcomes in terms of asthma-related hospitalisations and ER visits were compared.

Figure 2.

Algorithm displaying the identification of study subjects'. ICS, inhaled corticosteroids.

Study variables

Covariates

The exposed and unexposed groups were matched on age, gender, race, regions of Mississippi and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) using propensity scoring. The age of the subjects as of 31 December 2002 was computed. Gender was classified into male and female. Race was grouped into three categories: Caucasians, African–American and others. Additionally, subjects were categorised into rural and urban regions of Mississippi based on the county of residence. This variable was used to serve as a surrogate indicator of the access to care and control for differences in provider type. The CCI was computed and used as an indicator of additional comorbidities.

Adherence to ICS, average number of short-acting β agonists per subject, prior hospitalisations, ER visits, office and laboratory visits due to asthma were additionally controlled for in the analysis performed on the matched cohorts. These could only be computed after the unexposed subjects were assigned their index dates and hence could not be used for the propensity score calculations. The proportion of days covered was used as an indication of adherence to ICS therapy and was computed for the 6 months prior to the index date for each subject. Short-acting β agonists are the most effective therapy for rapid reversal of airflow obstruction and prompt relief of asthmatic symptoms. The average number of short-acting β agonists per subject was computed for 6 months prior to the index date and was used as an indicator of the severity of the disease. The number of hospitalisations, ER visits, office and laboratory visits attributed to a primary diagnosis of asthma in the 6-month washout period prior to the index date were also used as indicators of the severity of the disease.

Outcome variables

Hospitalisation due to asthma was coded dichotomously (as occurrence and non-occurrence of event), using the principal diagnosis code for hospitalisation, through 1-year after the index date for both the exposed and unexposed. Additionally, ER visit due to asthma was computed in a similar manner.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the exposed and unexposed subjects pre- and post-matching. Means and SDs were calculated for continuous data, whereas percentages were used for categorical data. Differences between exposed and unexposed groups were assessed using t tests or χ2 tests depending on whether the variable was continuous or categorical.

After the identification of the exposed and unexposed based on the inclusion criteria described previously, propensity scores were calculated for the subjects in both groups. The propensity score for an individual is defined as the conditional probability of being treated given the individual's covariates and thus reduces bias by balancing the covariates in the two groups.34 Logistic regression was used to compute and save the probability of being in the exposed group for all subjects based on their age, gender, race, region and CCI as discussed previously.

After the matched exposed and unexposed cohorts were obtained, conditional logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between statin use and the two outcome variables, asthma-related hospitalisations and ER visits.

Results

As discussed previously, 589 subjects met the inclusion criteria for the exposed cohort. The pool of unexposed subjects included 7390 individuals prior to matching on the propensity scores. Table 1 compares the demographic characteristics among the exposed and unexposed cohorts before and after matching. Prior to matching, the average age of asthma patients on concurrent statin therapy was significantly higher than that of those not on statin therapy (48.87 (±19.17) vs 63.28 (±12.25)). A significantly higher proportion of asthma patients who were not on concurrent statin therapy were African–American as compared with those on statin therapy (54.44% vs 42.95%) before matching. Additionally, those on concurrent statin therapy had a significantly higher average CCI than those not on concurrent statin therapy (4.01 (±2.48) vs 2.65 (±2.17)).

Table 1.

Study sample characteristics before and after matching

| Characteristic | Before matching |

p Value | After matching |

p Value | ||

| Exposed (589) | Unexposed (7390) | Exposed (479) | Unexposed (958) | |||

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.28 (±12.25) | 48.87 (±19.17) | <0.0001* | 62.59 (±12.13) | 63.48 (±12.92) | 0.2124 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.5750 | 0.1994 | ||||

| Male | 125 (21.22) | 1642 (22.22) | 101 (21.09) | 231 (24.11) | ||

| Female | 464 (78.78) | 5748 (77.78) | 378 (78.91) | 727 (75.89) | ||

| Race, n (%) | <0.0001* | 0.4716 | ||||

| White | 334 (56.71) | 3321 (44.94) | 269 (56.16) | 540 (56.37) | ||

| Black | 253 (42.95) | 4023 (54.44) | 208 (43.42) | 417 (43.53) | ||

| Other | 2 (0.34) | 46 (0.62) | 2 (0.42) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Region, n (%) | 0.0544 | 0.0287* | ||||

| Urban | 167 (28.35) | 2379 (32.19) | 138 (28.81) | 331 (34.55) | ||

| Rural | 422 (71.65) | 5011 (67.81) | 341 (71.19) | 627 (65.45) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index, mean (SD) | 4.01 (±2.48) | 2.65 (±2.17) | <0.0001* | 3.75 (±2.22) | 3.48 (±2.16) | 0.0300* |

*p<0.05.

After matching, the exposed cohort comprised of 479 individuals with 958 individuals in the unexposed cohort. Post-matching, a significantly higher proportion of asthma patients on concurrent statin therapy were from the rural areas of Mississippi (71.19% vs 65.45%; p=0.0287) as compared with those not on statin therapy (table 1). Additionally, the average CCI of patients on concurrent statin therapy was higher than that of those not on statin therapy (3.75 (±2.22) vs 3.48 (±2.16); p=0.03), but the difference was much smaller compared with the difference prior to matching.

The proportion of exposed and unexposed subjects using additional medications, besides ICS, for asthma management can be found in table 2.

Table 2.

Additional medications used for asthma management

| Medication | Exposed (479), n (%) | Unexposed (958), n (%) |

| Mast cell stabilisers | 2 (<1) | 5 (<1) |

| Leukotriene modifiers | 134 (28) | 318 (33) |

| Long-acting β agonists | 48 (10) | 126 (13) |

| Theophylline | 42 (9) | 142 (15) |

| Ipratropium | 31 (6) | 100 (10) |

| Short-acting β agonists | 180 (38) | 462 (48) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 81 (17) | 294 (31) |

Descriptive information on the covariates adjusted for in the final conditional logistic regression model can be found in table 3. Subjects with asthma on concurrent statin therapy were significantly less adherent to their ICS therapy (0.47 (±0.27) vs 0.51 (±0.28)), used lesser number of short-acting β agonist prescriptions on an average (2.74 (±2.10) vs 3.49 (±2.85)) and had fewer ER visits due to asthma 6 months prior to the index date (0.02 (±0.14) vs 0.06 (0.29)) when compared with subjects not on concurrent statin therapy.

Table 3.

Additional covariates adjusted for in the conditional logistic regression analysis

| Characteristic | Exposed (479), mean (±SD) | Unexposed (958), mean (±SD) | p Value |

| Adherence to ICS therapy (PDC) | 0.47 (0.27) | 0.51 (0.28) | 0.0146* |

| Average no. of short-acting β agonist prescriptions per subject | 2.74 (2.10) | 3.49 (2.85) | <0.0001* |

| No. of asthma office and laboratory visits 6 months prior the index date | 0.21 (0.64) | 0.24 (0.65) | 0.5031 |

| No. of asthma hospitalisation events 6 months prior the index date | 0.03 (0.19) | 0.05 (0.24) | 0.1002 |

| No. of asthma ER events 6 months prior the index date | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.06 (0.29) | 0.0063* |

*p<0.05.

ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; PDC, proportion of days covered.

The results of the conditional logistic regression conducted on the matched data and the ORs for hospitalisation/ER admission due to asthma among patients on concurrent statin therapy as opposed to those not on statin therapy are displayed in table 4. At least one asthma-related hospitalisation was observed in 3.79% of the subjects on concurrent statin therapy and 6.47% of the subjects not on concurrent statin therapy, 12 months after index date. At least one ER visit due to asthma was observed in 4.18% of the subjects on concurrent statin therapy and 9.08% of the subjects not on concurrent satin therapy, 12 months after index date. The odds of a hospital visit and/or ER visit due to asthma for asthma patients on concurrent statin therapy were almost half the odds for patients not on statin therapy (unadjusted OR=0.51; 95% CI (0.34 to 0.76)). Similarly, they were also less likely to be hospitalised (unadjusted OR=0.56; 95% CI (0.32 to 0.98)) and visit the ER (unadjusted OR=0.44; 95% CI (0.27 to 0.73)) due to asthma exacerbations as opposed to those not on statin therapy. The above ORs have not been adjusted for additional variables such as prior asthma-related hospitalisations, ER visits, office and lab visits, number of short-acting β agonist prescriptions and adherence to ICS therapy. The adjusted conditional ORs after accounting for these factors are also found in table 4. A statistically significant relationship between statin use and the combined end point as well as asthma-related ER visits remained after adjustment for these other variables.

Table 4.

Conditional ORs of hospitalisations due to asthma associated with statin use

| Outcome | Unadjusted OR†, (95% CI) | p Value | Adjusted OR‡, (95% CI) | p Value |

| Asthma hospitalisation and/or ER visit | 0.51 (0.34 to 0.76) | 0.0010* | 0.55 (0.36 to 0.84) | 0.0059* |

| Asthma hospitalisation | 0.56 (0.32 to 0.98) | 0.0436* | 0.63 (0.35 to 1.13) | 0.1183 |

| Asthma ER visit | 0.44 (0.27 to 0.73) | 0.0013* | 0.47 (0.28 to 0.82) | 0.0069* |

*p<0.05.

Adjusted for variables used to create propensity scores.

Adjusted for prior asthma-related hospitalisations, ER visits, office and laboratory visits, number of short-acting β agonist prescriptions and adherence to ICS therapy.

ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

Discussion

Over the 3 years of data analysed, 589 subjects met the inclusion criteria for the exposed cohort, prior to matching, and were classified as subjects on statin therapy, with 7390 subjects in the unexposed cohort. When comparing the demographic characteristics of patients on concurrent statin therapy to those not on statins, significant differences were observed. The average age of the asthmatic patients on statin therapy was significantly higher than those not on statin therapy. This was not surprising as patients with statin therapy would likely have hyperlipidaemia, a condition more prevalent in older adults. Additionally, a significantly higher proportion of patients on statin therapy were Caucasian when compared with the unexposed population and also had a higher average CCI score. In order to control for the above differences, propensity scores were computed and the study groups were matched on their propensity to be in the exposed cohort.

The final sample comprised of considerably older subjects with the average age of the exposed and unexposed being 62.59 (±12.13) years and 63.48 (±12.92) years, respectively. Most of the study subjects were women, which is consistent with the previous prevalence reports which indicate that asthma is more prevalent in women in general.35 Additionally, a higher proportion of the sample was Caucasian, lived in rural regions and had a considerable number of comorbid conditions.

A higher proportion of the unexposed subjects were on additional asthma controller therapy (table 2). It is interesting to note, however, that the average number of short-acting β agonist prescriptions were significantly higher for patients not on statin therapy, and thus, one might expect their condition to be better managed, which does not seem to be the case. Thus, the other way to look at it is that their condition is more severe or is not being managed well and hence the higher average number of quick relief prescriptions.

A significant reduction in the odds of hospitalisation and ER visits due to asthma was found to be associated with statin use. Even after controlling for the confounders mentioned above, patients not on concurrent statin therapy were almost twice as likely to have hospitalisation and/or ER visits attributable to asthma when compared with patients on statin therapy. These findings suggest that statins are beneficial in asthma management. This is in accordance with other observational studies conducted to investigate this relationship.32 33

There are several limitations of this study. The study was conducted using Medicaid claims data, and therefore, there is a possibility of misclassification due to coding errors during claims processing. Further, even though the subjects in the unexposed group were matched to the exposed population based on their propensity scores, significant differences between the two groups were still observed when compared across their CCI scores and the region (urban vs rural) to which they belonged. This could be attributed to two plausible explanations. First, the cohorts were matched on propensity scores allowing a range of ±0.005. Second, each subject was initially matched to 10 corresponding subjects from the unexposed pool, following which two controls were selected based on their continuous eligibility throughout the study period and ICS prescription records within 180 days prior to the index date. However, both of the above measures were incorporated into the study design to maximise the sample size. Even after matching, subjects on statin therapy had a significantly higher average CCI score compared with those not on statin therapy. It is unlikely that this difference could have biased the findings towards a lower risk of hospitalisation due to asthma in these subjects. Another limitation is that the population studied had an average age of approximately 63 years and were sicker patients in general due to the higher CCI scores, which limits the generalisability of the study to some extent.

The findings of this study contribute significantly to the growing body of literature that suggests that statins have beneficial effects in preventing asthma exacerbations. Some researchers suggest that the addition of a statin to ICS therapy in clinical practice will not prove beneficial in the management of asthma referring to the practice as a ‘snake oil panacea’.36 However, further investigation employing different data sets, different methodologies and accounting for other confounding variables which may have been overlooked is required to provide conclusive evidence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Lokhandwala T, West-Strum D, Banahan BF, et al. Do statins improve outcomes in patients with asthma on inhaled corticosteroid therapy? A retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001279. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001279

Contributors: The research was conducted as part of TL's Master's thesis project, with DW-S as the chair of the thesis committee and JB, BFB and YY serving as committee members. TL was responsible for the literature review, conceptualisation, data management, data analysis and for preparing the first draft of the manuscript. DW-S, BFB, JB and YY helped with the conceptualisation and troubleshooting and provided valuable insights during the preparation of the final manuscript document. Additionally, BFB helped with the preparation of the Data Use Agreement to obtain Medicaid data for analysis from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of University of Mississippi.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Stoll L, Denning G, Weintraub N. Endotoxin, TLR4 signaling and vascular inflammation: potential therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. Curr Pharm Des 2006;12:4229–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganotakis E, Mikhailidis D, Vardas P. Atrial fibrillation, inflammation and statins. Hellenic J Cardiol 2006;47:51–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Endres M. Statins: potential new indications in inflammatory conditions. Atheroscler Suppl 2006;7:31–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Athyros V, Elisaf M, Mikhailidis D. Inflammatory markers and the metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis 2005;183:187–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeki A, Kenyon N, Goldkorn T. Statin drugs, metabolic pathways, and asthma: a therapeutic opportunity needing further research. Drug Metab Lett 2011;5:40–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leung B, Sattar N, Crilly A, et al. A novel anti-inflammatory role for simvastatin in inflammatory arthritis. J Immunol 2003;170:1524–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanda H, Hamasaki K, Kubo K, et al. Antiinflammatory effect of simvastatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2002;29:2024–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazi I, Boumpas D, Mikhailidis D, et al. Clustering of cardiovascular risk factors in rheumatoid arthritis: the rationale for using statins. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2007;25:102–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paintlia A, Paintlia M, Singh I, et al. Combined medication of lovastatin with rolipram suppresses severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Exp Neurol 2008;214:168–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanislaus R, Gilg A, Singh A, et al. Immunomodulation of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the Lewis rats by Lovastatin. Neurosci Lett 2002;333:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jong Y, Joo S, Jung M, et al. Simvastatin inhibits NF-κB signaling in intestinal epithelial cells and ameliorates acute murine colitis. Int Immunopharmacol 2007;7:241–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nermina J, Nursal G, Feriha E. Effects of statins on experimental colitis in normocholesterolemic rats. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006;4:954–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namazi M. Statins: novel additions to the dermatologic arsenal? Exp Dermatol 2004;13:337–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandermeer M, Thomas AR, Kamimoto L, et al. Association between use of statins and mortality among patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infections: a mutli-state study. J Infect Dis 2011;205:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paraskevas I, Tzovaras A, Briana D, et al. Emerging indications for statins: a pluripotent family of agents with several potential applications. Curr Pharm Des 2007;13:3622–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samson K, Tanaka O, Yokoe T, et al. Inhibitory effects of fluvastatin on cytokine and chemokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2006;36:475–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ennis M. New therapeutic interventions in airway inflammatory and allergic diseases. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem 2006;5:353–6 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takizawa H. Novel strategies for the treatment of asthma. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2007;1:13–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hothersall E, McSharry C, Thomson NC. Potential therapeutic role for statins in respiratory disease. Thorax 2006;61:729–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiba Y, Arima J, Sakai H, et al. Lovastatin inhibits bronchial hyperresponsiveness by reducing RhoA signaling in rat allergic asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:705–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiba Y, Sato S, Misawa M. Inhibition of antigen-induced bronchial smooth muscle hyperresponsiveness by lovastatin in mice. J Smooth Muscle Res 2008;44:123–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiba Y, Sato S, Misawa M. Lovastatin inhibits antigen-induced airway eosinophilia without affecting the production of inflammatory mediators in mice. Inflamm Res 2009;58:363–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKay A, Leung BP, McInnes IB, et al. A novel anti-inflammatory role of simvastatin in a murine model of allergic asthma. J Immunol 2004;172:2903–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imamura M, Okunishi K, Ohtsu H, et al. Pravastatin attenuates allergic airway inflammation by suppressing antigen sensitization, interleukin 17 production and antigen presentation in the lung. Thorax 2009;64:44–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim DY, Ryu YS, Lim EJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of simvastatin in mouse allergic asthma model. Eur J Pharmacol 2007;557:76–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tschernig A, Baumer W, Pabst R. Controversial data on simvastatin in asthma: what about the rat model? J Asthma Allergy 2010;3:57–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hothersall E, Chaudhuri R, McSharry C, et al. Effects of atorvastatin added to inhaled corticosteroids on lung function and sputum cell counts in atopic asthma. Thorax 2008;63:1070–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menzies D, Nair A, Meldrum K, et al. Simvastatin does not exhibit therapeutic anti-inflammatory effects in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:328–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cowan D, Cowan J, Palmay R, et al. Simvastatin in the treatment of asthma: lack of steroid-sparing effect. Thorax 2010;65:891–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maneechotesuwan K, Ekjiratrakul W, Kasetsinsombat K, et al. Statins enhance the anti-inflammatory effects of inhaled corticosteroids in asthmatic patients through increased induction of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:754–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braganza G, Chaudhuri R, McSharry C, et al. Effects of short-term treatment with atorvastatin in smokers with asthma—a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm Med 2011;11:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanek E, Aubert R, Xia F, et al. Statin exposure reduces the risk of asthma-related hospitalisations and emergency room visits in asthmatic patients on inhaled corticosteroids. [abstract]. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;123:S65 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang C, Chan W, Chen Y, et al. Staitn use in patients with asthma—a nationwide population-based study. Eur J Clin Invest 2011;41:507–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med 1998;17:2265–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for health statistics. National Surveillance for asthma—United States 1980-2004. Surveill Summ 2007;56:1–54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin B. Statins for the treatment of asthma: a discovery well, dry hole or just snake oil. Thorax 2009;64:4–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.