Abstract

Examining the patterns of archaeal diversity in little-explored organic-lean marine subsurface sediments presents an opportunity to study the association of phylogenetic affiliation and habitat preference in uncultured marine Archaea. Here we have compiled and re-analyzed published archaeal 16S rRNA clone library datasets across a spectrum of sediment trophic states characterized by a wide range of terminal electron-accepting processes. Our results show that organic-lean marine sediments in deep marine basins and oligotrophic open ocean locations are inhabited by distinct lineages of archaea that are not found in the more frequently studied, organic-rich continental margin sediments. We hypothesize that different combinations of electron donor and acceptor concentrations along the organic-rich/organic-lean spectrum result in distinct archaeal communities, and propose an integrated classification of habitat characteristics and archaeal community structure.

Keywords: archaea, marine sediments, oligotrophy, subsurface, phylogeny, uncultured archaea

Introduction

Marine sedimentary microbial communities are key mediators of global biogeochemical cycles (e.g., D’Hondt et al., 2002, 2004; Wellsbury et al., 2002). The Domain Archaea accounts for a large portion, perhaps the majority, of deep-subsurface prokaryotic cells and biomass (Biddle et al., 2006; Lipp et al., 2008), and by implication, global biomass (Parkes et al., 1994; Whitman et al., 1998). The majority of studies thus far have focused on relatively organic-rich deep-subsurface sediments (e.g., Parkes et al., 1994, 2005; Reed et al., 2002; Wellsbury et al., 2002; D’Hondt et al., 2004; Biddle et al., 2006; Inagaki et al., 2006; Sørensen and Teske, 2006; Kendall et al., 2007; Heijs et al., 2008; Nunoura et al., 2008). However, abyssal sediments >2000 m water depth cover a much larger extent of the ocean floor (∼89%; Dunne et al., 2007) and, in contrast to margin or coastal sediments, are generally oligotrophic, with low organic carbon content (<1%) and slow rates of deposition (Seiter et al., 2004; Dunne et al., 2007). Electron acceptors such as oxygen or nitrate penetrate these oligotrophic sediments on a scale of meters (D’Hondt et al., 2004) or tens of meters (Gieskes and Boulègue, 1986; D’Hondt et al., 2009), in contrast to organic-rich continental margin or shelf sediments where these strong electron acceptors are used up within centimeters. This expansion of the oxic and nitrate-reducing zone in oligotrophic sediments is a function of the slow rates of carbon deposition and microbial carbon remineralization. The combination of higher-energy electron acceptor type and slower flux of electron donor substrates likely imposes distinct constraints on life in oligotrophic marine sediments, which cover the majority of the surface of Earth.

Several phylum-level uncultured archaeal lineages have been identified as typical deep-subsurface sediment-associated groups (Inagaki et al., 2003, 2006; Parkes et al., 2005; Biddle et al., 2006, 2008; Sørensen and Teske, 2006; Teske and Sørensen, 2008; Fry et al., 2008). These include the Marine Benthic Group B (MBG-B, Vetriani et al., 1999), a deeply branching phylum-level lineage; the Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotal Group (MCG, Inagaki et al., 2003), a frequently detected crenarcheotal lineage with high intragroup diversity; the South African Gold Mine Euryarchaeotal Group (SAGMEG, Takai et al., 2001); and the Marine Benthic Group D (MBG-D, Vetriani et al., 1999), a euryarchaeotal group affiliated with the Thermoplasmatales. All of these are approximately phylum-level in divergence, with the exception of the MBG-D, which groups along with the MG-II archaea (DeLong, 1992; Fuhrman et al., 1992) and MG-III archaea (Fuhrman and Davis, 1997) in a well-supported clade affiliated with the Thermoplasmatales (Durbin and Teske, 2011). However, our current datasets on archaeal community composition in deep marine sediments are biased toward organic-rich continental margin sediments (Teske and Sørensen, 2008). Relatively few studies have surveyed the archaeal diversity of abyssal or ocean gyre sediments to date. A more or less comprehensive list includes: Vetriani et al., 1999; Inagaki et al., 2001; Sørensen et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2004; Nercessian et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2005; Gillan and Danis, 2007; Li et al., 2008; Tao et al., 2008; Roussel et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2010a, Liao et al., 2011; Durbin and Teske, 2010, 2011. Most of these studies are limited to shallow sediments (<1 m deep) or to few depth intervals. Thus, the available database for archaeal communities in oligotrophic marine subsurface sediments has not yet reached the same coverage as eutrophic sediments. Nonetheless, initial datasets from the South Pacific (Durbin et al., 2009; Durbin and Teske, 2010, 2011) and other datasets in the literature point to profoundly different archaeal communities, with little or no overlap at the phylum and subphylum level.

Examining the patterns of archaeal diversity in little-explored oligotrophic sediments presents an opportunity to study the association of phylogenetic affiliation and habitat preference in uncultured Archaea. We expect a linkage between sediment habitat type and phylogenetic identity, since the distinct physiological demands – sustaining metabolism and growth with low-energy electron acceptors in anaerobic, organic-rich sediments, in contrast to electron donor limitation in oxidized sediments – should select for distinct organisms in organic-lean, oxidized sediments that differ from those in organic-rich, reduced sediments. Specialization in terminal electron acceptors with higher redox potential for a given substrate may differentiate organisms adapted to oxic/suboxic organic-lean environments from those adapted to more organic-rich, typically anoxic environments.

However, an important caveat is that free-energy yield is highly contingent on in situ conditions, possibly subverting the expected hierarchy of electron acceptor energy yields based on standard conditions. Factors such as syntrophy (McInerney and Beaty, 1988), biotic (Wang et al., 2008, 2010b), or abiotic (König et al., 1997, 1999) release from feedback inhibition, pH (Postma and Jakobsen, 1996; Thamdrup, 2000), and substrate competitive release or substrate-pooling (e.g., Lever et al., 2010) may all impact in situ energetics of metabolisms. Additionally, redox niche adaptation likely extends beyond simply the ability to use a particular electron acceptor. In situ redox state (Eh) determines the thermodynamic favorability of a given biosynthetic pathway, as biosynthetic pathways feasible under highly reduced conditions are less favorable in more oxidized environments; fatty acid biosynthesis (palmitate) is a classic example (McCollom and Amend, 2005). Low substrate concentrations in organic-lean environments may be countered with high-substrate-affinity catabolic enzymes, as in the oligotrophic archaeon Nitrosopumilus maritimus (Martens-Habbena et al., 2009). Economical use of electron acceptors with a high redox potential, as shown for ammonia-oxidizing Thaumarchaeota (Schleper and Nicol, 2010), may allow organisms to take advantage of the expanded redox transition zones in organic-lean environments.

With the largely unexplored complexity of organismal redox adaptation noted, we hypothesize that different combinations of electron donor and acceptor concentrations along the organic-rich/organic-lean spectrum result in distinct archaeal communities that have optimized their energetic requirements for cell maintenance and growth. This hypothesis article examines published archaeal 16S rDNA clone library datasets across a wide spectrum of sediment trophic states and terminal electron-accepting processes.

Sampling Sites

This study analyses archaeal communities in organic-lean subsurface sediments from the South China Sea (Wang et al., 2010a), the Fairway Basin in the Western Tropical Pacific (Roussel et al., 2009), the Peru Basin offshore Peru (Sørensen et al., 2004), the equatorial upwelling zone west of the Galapagos (Teske, 2006; Teske and Sørensen, 2008), and the South Pacific Subtropical Front northeast of New Zealand (Durbin and Teske, 2011; Table 1; Figure 1). These sediments were contrasted with organic-rich sediments of ODP Leg 201 sites 1227 and 1229, located beneath the highly productive Peruvian upwelling zone, with the methane-clathrate-bearing deep-subsurface sediments of ODP site 1230 in the Peru Trench (Parkes et al., 2005; Biddle et al., 2006; Inagaki et al., 2006; Sørensen and Teske, 2006), and with sediments from the Cascadia Margin offshore Oregon recovered during ODP Leg 204 (Inagaki et al., 2006; Nunoura et al., 2008). ODP Leg 201 Site 1226 south of Galapagos was included as an example of a mesotrophic deep marine sediment, and IODP Expedition 308 sites U1319 and U1320 were included as examples of turbidite continental slope sediments (Nunoura et al., 2009). Methane seep sediments from the Mediterranean provided an example of a deepwater, yet highly reducing shallow sediment environment (Heijs et al., 2008). A phylogenetic and environmental outgroup is provided by sequences from two non-marine anoxic habitats, an anaerobic digestor (Chouari et al., 2005) and rumen (Sundset et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Overview of site characteristics and parameters relating to trophic state of organic-lean to organic-rich marine subsurface sediments.

| Site | Marine Province, location | Water depth | Length of cored Sediment and total sediment thickness, mbsf | Log[10] range, and mbsf range of cell counts | Sedimentation rate, m/My [DSDP/ODP site] | TOC, % weight of sediment | Max. DIC, mM | Ammonia, μM | Oxygen depletion depth, mbsf | Nitrate depletion depth, mbsf | Sulfate concentration minima [mM] and depth [mbsf] | Sulfide/reduced metals | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPG11 | South Pacific Gyre 41°51.13S, 153°06.38 W | 5076 | 2.98 [67] | 3.87–6.63 [2.96–0.1] | 0.9 [averaged over entire sediment column] | 0.51 (0.0–0.05 mbsf) | 2.44 mEq (alkalinity) | Below detection | No depletion | No depletion | No depletion | −/− | D’Hondt et al. (2009), Durbin and Teske (2010) |

| SPG12 | South Pacific Subtrop. Front 45°57.86S, 163°11.05W | 5306 | 4.98 [130] | 5.37–6.3 [4.9–0.25] | 1.8 [averaged over entire sediment column] | 0.34 (0.0–0.05 mbsf) | 3.23 mEq (alkalinity) | Below detection | ∼0.70 | 2.55 | No depletion | −/+ | D’Hondt et al. (2009), Durbin and Teske (2011) |

| ODP Leg 201, site 1231 | Peru Basin 12°01.29 S, 81°54.24 W | 4813 | 119.1 [∼120] | 5.14–8.24 [81.64–0.01] | Closest analog: Eocene-Quaternary, 4-10 [DSDP 321]* | 0.07–0.7 | 3.64 | 7.64–32.72 | No data | 0.1–0.4 | No depletion | −/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003f), D’Hondt et al. (2004), *Shipboard Scientific Party (1976) |

| ODP Leg 201, site 1225 | Eastern Equat. Pacific 02°46.22 N, 110°34.30 W | 3760 | 315.6 [∼320] | 5.26–6.87 [320–0.85] | Closest analog: Miocene-Quaternary, 15–65 [ODP 851]* | 0.00–0.53 | 3.98 | 6.15–38.48 | No data | ∼1.5 | No depletion | −/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003a), *Shipboard Scientific Party (1992a) |

| ODP Leg 201, site 1226 | South Equat. Current near Galapagos 03°05.80 S, 90°49.07 W | 3297 | 418.9 [421] | ∼6–8.67 [420–0.01] | Closest analog: Miocene-Quaternary, ∼40 [ODP 846]* | 0.25–3.49 | 7.03 | 51.7–641 | No data | Not resolved | Partial depletion (18.9 mM at 246 m depth) | +/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003b), *Shipboard Scientific Party (1992b) |

| MD05-2902 North Core | South China Sea, Pearl River Basin 17°57.70 N, 114°57.33 E | 3697 | 9.42 [>850] | No data | Closest analog: Miocene, 11–17 Pliocene to Pleistocene, 27–63 [ODP 1148]* | 0.2–1.4 | Closest analog: 9.14 [ODP 1148]* | Closest analog: 640-1390 [ODP 1148]* | No data | No data | Closest analog: 3 mM at 630–650 m [ODP 1148]* | +/+ | Wang et al. (2010a), *ODP Leg 184: Shipboard Scientific Party (2000b) |

| MD05-2896 South Core | Southern, South China Sea 08°49.59 N, 111°26.47 E | 1657 | 11.03 [>500] | No data | Closest analog: Miocene to recent, 30–50 [ODP 1143]* | 0.2–1.3 | Closest analog: 11.18 [ODP 1143]* | Closest analog: 200–1900 [ODP 1143]* | No data | No data | Closest analog: 6.3 mM at 500 mbsf [ODP 1143]* | +/+ | Wang et al. (2010a), *ODP Leg 184: Shipboard Scientific Party (2000a) |

| ZoNeCo-12: MD06-3022, MD063026, MD063027, MD063028 | Fairway Basin, Coral Sea 24°S, 163°E | 2294 (MD06-3022), ∼2700 others | 9.4 [>>560] | 6.2–8.3 [9.4–0.2] | Closest analog: Neogene, 10 [ZoNeCo-5 sites in Fairway Basin]* | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | 18 mM at 7.5 mbsf Extrapolated depletion depth at 3022: ∼60 m | +/+ | Roussel et al. (2009), *Dickens et al. (2001) |

| IODP leg 308, site U1320 | Brazos Basin 27°18.08 N, 94°23.25 W | 1480 | 299.6 | <4–6.08 [284.8–7.5] | 1810 [Holocene to 80 ky] | 0.03–1.99 | 15.99 [alkalinity] | 132–3816 | No data | No data | Depletion to 0.6 mM at 22 mbsf | +/+ | Expedition 308 Scientists (2006b) |

| IODP leg 308, site U1319 | Brazos Basin 27°15.96 N, 94°24.19 W | 1440 | 157.5 | <4–6.08 [157.5–4.4] | 150 [Holocene} 2310 [>90–150 ky] | 0.16–1.9 | 19.45 [alkalinity] | 291 – 4411 | No data | No data | Depletion to 0.5 mM at 15 mbsf | +/+ | Expedition 308 Scientists (2006a) |

| ODP Leg 201, site 1227 | Peru Margin 08°59.45 N, 79°57.35 W | 427 | 151 (> > ) | 6.25–7.70 [151-0.15] | Miocene-Quaternary: 20-50 [ODP 684]* | 1.16– 10.57 | 25.78 | 3168.2–8875.5 | No data | Not resolved | Depletion at ∼41 mbsf | +/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003c) *Shipboard Scientific Party (1988a) |

| ODP Leg 201, site 1229 | Peru Margin 10°58.57 S, 77°57.46 W | 151 | 192.9 (>>) | 6.43–9.97 [185.7–90.45] | Quaternary∼80 [ODP 681]* | 0.83–3.97 | 21.14 | 5335.69–6746.53 | No data | Not resolved | Depletion at ∼32 mbsf | +/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003d) *Shipboard Scientific Party (1988b) |

| ODP Leg 201, site 1230 | Peru Trench 09°06.78 S, 80°35.01 W | 5086 | 277.3 (>>) | 6.1–8.62 [257.7–0.01] | Miocene-Quaternary: 100–250 [ODP 685]* | 1.27–3.98 | 162.95 | 1920–40170 | No data | Not resolved | Depletion at ∼9 mbsf | +/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003e) *Shipboard Scientific Party (1988c) |

| ODP Leg 204, site 1244 | Cascadia Margin 44°35.18 N, 125°07.19 W | 890 | 380 (>>) | ∼6–7, qPCR [123–2.0]* | 60–270 | 0.87–1.75 | 68.9 [alkalinity] | Max. 22700 | No data | No data | Depletion to ∼0.5–1 mM at ∼11 mbsf | +/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003g) *Nunoura et al. (2008) |

| ODP Leg 204, site 1245 | Cascadia Margin 44°35.16 N, 125°08.95 W | 870 | 540 (>>) | Not detected in qPCR* | 100–620 | 0.71–1.46 | 73.31 [alkalinity] | Max. 21800 | No data | No data | Depletion to ∼0.5–1 mM at ∼8 mbsf | +/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003h) *Nunoura et al. (2008) |

| ODP Leg 204, site 1251 | Cascadia Margin 44°34.21 N, 125°04.44 W | 1216 | 445 (>>) | ∼6–8, qPCR [204.2–4.5]* | 600–1600 | 0.58–3.06 | 122.37 [alkalinity] | Max. 14800 | No data | No data | Depletion to ∼0.5 - 1 mM at ∼3 mbsf | +/+ | Shipboard Scientific Party (2003i) *Nunoura et al. (2008) |

| Napoli cold seep | Eastern Mediterranean 33°43.47 N, 24°42.09 E | 1947 | 0.28 (>>) | No data | Not applicable | 1.22–3.95 | No data | 217.2–40.6 | No data | 0 cmbsf | Not resolved | +/no data | Heijs et al. (2008) |

| Kazan mud volcano | Eastern Mediterranean 35°26.00 N, 30°33.50 E | 1720 | 0.34 (>>) | No data | Not applicable | 2.59–17.4 | No data | 30.0–158.5 | No data | ∼6 cmbsf | Depletion at 0.35–0.40 mbsf [0.25 mbsf]* | +/no data | Heijs et al. (2008)*Kormas et al. (2008) |

| Amsterdam mud volcano | Eastern Mediterranean 35°19.85 N, 30°16.85 E | 2050 | 0.31 (>>) | No data | Not applicable | 3.9–4.31 | No data | 50.6–152.5 | No data | 0 cmbsf | Not resolved | +/no data | Heijs et al. (2008) |

From top to bottom: ultraoligotrophic site without depletion of oxygen or nitrate (SPG11); oligotrophic sites with nitrate depletion within meters (SPG12, ODP 1225 and 1231); mesotrophic sites (ODP 1226, South China Sea, Coral Sea); and eutrophic sites (IODP 308 sites U1319, U1320 with caveats; ODP Leg 201 sites 1227, 1229, 1230; ODP Leg 204 sites 1244, 1245, 1251) characterized by high DIC and NH4 porewater concentration maxima, and high sedimentation rates. Outgroup, Mediterranean seep sediments.

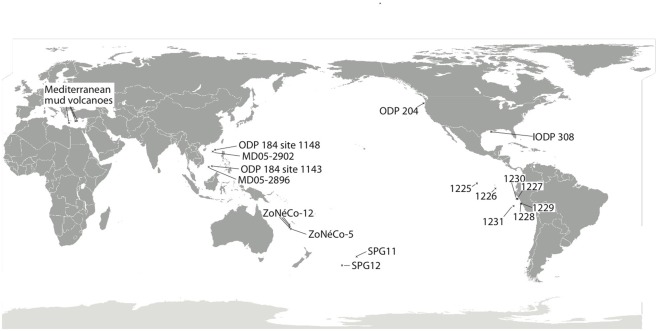

Figure 1.

Map depicting approximate location of marine sediment cores discussed in the current review. SPG11 occurs just inside the southern South Pacific Gyre, while SPG12 lies on the subtropical front separating the gyre from the Southern Ocean (D’Hondt et al., 2009). Sites MD05-2896 and MD05-2902 (Wang et al., 2010a) are from the South China Sea, with additional geochemical data on these sites sourced from nearby ODP Leg 184 Sites 1143 and 1148 (Shipboard Scientific Party, 2000a,b). The ZoNéCo-12 sites lie in the Fairway Basin in the Coral Sea (Roussel et al., 2009), with additional information from ZoNéCo-5 sites (Dickens et al., 2001). The IODP 308 sites (U1319, U1320) are located in the turbidite depositional Brazos-Trinity Basin on the continental slope of the northern Gulf of Mexico (Nunoura et al., 2009). The ODP Leg 201 Sites (Shipboard Scientific Party, 2003a–f; D’Hondt et al., 2004) include sites from the eastern equatorial upwelling region (1225), South Equatorial Current (1226), Peru Margin (1227, 1229), Peru Trench (1230), and the Peru Basin (1231). The ODP Leg 204 Cascadia Margin sites include sites 1244, 1245, and 1251 (Nunoura et al., 2008). Mud volcano/cold seep sites are represented by three examples from the eastern Mediterranean (Heijs et al., 2008).

Although geochemical data were incomplete, two sites from the South China Sea (MD05-2896, MD05-2902; Wang et al., 2010a) and several sediment columns from the Coral Sea (ZoNéCo-12 sites; Roussel et al., 2009) were included as oligotrophic to mesotrophic sedimentary environments (Table 1; Figure 1) based on nearby ODP sites with complementary geochemistry data. Approx. 195 km separates ODP Leg 184 Site 1148 and MD05-2902, both are located at similar depths (Site 1148: ∼3700; MD05-2902: ∼3300 m) in the Pearl River Basin, Northern South China Sea. ODP Leg 184 Site 1143 and MD05-2896 are separated by ∼210 km within the Dangerous Grounds geologic province of the South China Sea. Although these sites are at significantly different depths (approx. 1650 m for MD05-2896 and ∼2770 m for Site 1143), they share a common sedimentary regime of pelagic drape amid broken carbonate platforms distant from the continental shelf (Hutchison, 2004). Analogs for the ZoNeCo-12 sites in the Fairway Basin south of New Caledonia come from a prior geochemical survey (ZoNéCo-5) of the same marine basin. The sites from these two surveys are ∼127 to 285 km distant, and are located at similar depths (ZoNeCo-5: 2700 m; ZoNeCo-12: ∼2500–2700 m), with presumably similar sedimentation regimes (Dickens et al., 2001).

Some oligotrophic sediments are problematic since their microbial community structure and geochemical characteristics overlap with those of hydrothermal sediments (Inagaki et al., 2001; Nercessian et al., 2005; Li et al., 2008) and the deep-water column. Several studies of oligotrophic abyssal sediments (Wang et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2005; Gillan and Danis, 2007) sampled only surficial sediments and recovered the same archaeal phylum, the Marine Group I Crenarchaeota, that is presumed dominant in the overlying water column (e.g., Karner et al., 2001; Church et al., 2003; Agogué et al., 2008; Durbin and Teske, 2010). Because of the high potential for cross-contamination and the phylogenetic similarity between oxic sediments and the overlying water column, to confidently label MG-I clones collected from oxic sediments as indigenous requires stringent contamination controls and/or investigations of the diversity of contamination sources (Durbin and Teske, 2010). Due to these difficulties, MG-I sequences were excluded from the current analysis.

The Sedimentary Trophic State Spectrum

In the following section, we summarize some of the most informative biogeochemical and microbiological parameters for oligotrophic marine subsurface sediments (Table 1) and show that these sites appear to fall into several natural groups.

Sedimentation rates

Sedimentation rates can approximate sediment trophic states, albeit with some exceptions for high-carbonate or turbidite-associated sedimentation and changing oceanographic conditions in the surface ocean, which can all enrich or impoverish deep marine sediments relative to the expected trophic state based on surface ocean productivity, or if a significant fraction of sedimentation is inorganic carbonate or silicate. Sedimentation rates at SPG Sites 11 and 12, are near 0.9 and 1.8 m/My, averaged over the entire depth and age of the sediment column (D’Hondt et al., 2009). For reference, averaged ocean sedimentation rates for the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Ocean based on DSDP cores ranged from 30 to 50 m/my for quaternary sediments, and decreased to 2–5 m/my for paleocene sediments (Whitman and Davis, 1979). Among ODP Leg 201 sites, Site 1231 is the slowest-accumulating site, but still 4 to 10 times or 2 to 5 times faster than the South Pacific sites SPG11 or SPG12 (Table 1). The Peru Margin, Peru Trench, and Cascadia Margin sites form a cohort with increasingly high sedimentation rates, up to 1600 m/my at Cascadia Margin site 1251 (Table 1), three orders of magnitude higher than at the South Pacific sites (Table 1), dramatically illustrating the different constraints shaping eutrophic margin environments and ultraoligotrophic gyre sediments. An extreme outlier are the Gulf of Mexico slope turbidite sediments sampled on IODP Expedition 308 (Table 1).

Porewater DIC

Concentrations of porewater DIC above or below the mean seawater concentration are an indicator of the magnitude and direction of net metabolism. Net heterotrophy due to remineralization of organic matter to CO2 increases DIC concentrations, at least at the more oligotrophic end of the scale; in highly organic-rich sediments, a large fraction of organic carbon may be remineralized not to CO2 but to methane. Nevertheless, because DIC directly reflects metabolic rates, it integrates over unknowns inherent in interpreting sedimentation rates or electron acceptor depletion profiles. Comparisons of maximum DIC for Leg 201 sites suggest a spectrum from highly DIC-enriched Cascadia Margin sites 1244, 1245, and 1251 and Peru Trench Site 1230, to Peru Margin sites 1229 and 1227, the Gulf of Mexico Expedition 308 sites, the South China Sea sites, to ODP sites 1226, 1225, and 1231; the SPG sites 12 and 11 mark the DIC-poor end of the spectrum (Table 1). Here, alkalinity (∼96% of which is DIC, at seawater pH) remains at seawater values throughout the sampled sediment column at SPG11, while SPG12 displays a downcore alkalinity increase concomitant with oxygen drawdown, and stabilizing thereafter (Table 1). Maximal porewater NH4 concentrations show the same trend and sort the sites into the same sequence as porewater DIC (Table 1), reflecting the origin of NH4 from remineralization of buried biomass.

Organic carbon availability

Organic carbon concentration is not a directly proportional measure of sediment trophic state, as substrate lability and organic carbon residence time can vary between sediments with similar organic carbon contents. Therefore, trophic state of the sediment can change without necessarily affecting the sediment organic carbon percent weight, and organic carbon content between sites of possibly different trophic state can overlap. Among the South Pacific Gyre sites, organic carbon content values for SPG11 ranged from 0.59 to 0.45 dry weight% over the upper 9 cmbsf (centimeter below surface), with little change after the upper 2 cmbsf; surface sediments (0–5 cmbsf) from SPG12 contained 0.34% (D’Hondt et al., 2009). A global TOC analysis in marine sediments showed that abyssal sediments contain less than or at most 1 weight% TOC, close to the global mean for marine sediments (Seiter et al., 2004); this is consistent with the oligotrophic sites in this survey. Higher TOC values in the range of up 1–2% are shared by the South China Sea sites and the Gulf of Mexico turbidite sediments (Table 1). The eutrophic Leg 201 sites varied between ∼1 and 10% TOC for different horizons, with ∼4% most typical for the majority of the sediment column, and typically decreasing with depth (Table 1). Interestingly, the Cascadia Margin Leg 204 sites showed lower TOC concentrations (maxima ca. 1.5–3%) than the Leg 201 Peru Margin and Peru Trench sediments, and resembled in this regard the Gulf of Mexico turbidites (Table 1).

Cell densities

Total prokaryotic cell densities at the SPG sites are the lowest yet recorded for any equivalent depth horizon (D’Hondt et al., 2009). For all sites, cell counts declined with sediment depth, with the lowest value typically being the deepest. Cell counts ranged from 103.9 to 106.6 per ml over the upper 2.8 m at SPG11, and 105.4 to 106.3 per ml over the upper ∼5 m at SPG12, again setting SPG11 apart. These cell counts were lower than those of deepwater ODP sites 1231 and 1225 at comparable depth; the deepwater ODP sites had similar or higher cell counts over a much broader depth range, and declined to their lowest levels of ∼105 at greater depths, 81.6 mbsf for 1231 and 320 mbsf for 1225. Given their location on continental margins, the Gulf of Mexico turbidite sediments of Expedition 308 had unusually low cell densities; the maxima in the range of 105.3 to 106.08 cells per ml were found near the sediment surface, and cell densities decreased rapidly with depth (Nunoura et al., 2009). Cell counts of the mesotrophic ODP 1226 and the eutrophic Peru Margin and Trench sites ranged from 106 to 1010 cells per cm3 throughout the sediment column (Table 1). No direct cell counts are available from the ODP 204 sites; the qPCR data for 16S rRNA gene copy numbers have to be viewed with caution, given occasionally complete PCR inhibition (Nunoura et al., 2008).

Oxygen, nitrate, and sulfate gradients

Typically, electron acceptors for microbial metabolism are depleted downcore in order of declining energy yield; depletion depth increases with organic substrate scarcity. Thus, organic-carbon limited sediments are expected to be deeply permeated by high-energy electron acceptors. Within increasingly organic-rich sediments, oxidants retreat toward the seawater/sediment interface, leading to a shrinking zone of oxidant availability. The porewater gradients of the strongest oxidants (oxygen, nitrate) are therefore strongly compressed toward the sediment surface, whereas the porewater profiles of weaker oxidants (oxidized metals, sulfate) extend deeply into the sediment column (D’Hondt et al., 2002, 2004).

At the ultraoligotrophic SPG11 site, oxygen drawdown is minimal and nitrate drawdown is not evident; porewater oxygen remains at ∼160 μM at 280 cmbsf and is unlikely to be depleted downcore, unless there are deep biotic or abiotic sediment oxygen sinks (D’Hondt et al., 2009). At site SPG12, oxygen becomes depleted near 70 cmbsf, and nitrate is depleted at 253–258 cmbsf (D’Hondt et al., 2009). Oxygen data are not available for ODP sediment cores; sediment cores from ODP sites 1225 and 1231 show nitrate depletion on the scale of 10–40 cmbsf for 1231, and ∼150 cmbsf for site 1225 (Table 1). The surficial 1–2 m sediment horizons, and the nitrate and oxygen porewater profiles therein, are generally lost or disturbed during ODP coring. Nitrate and oxygen profiles in centimeter resolution can be obtained from sediment cores with undamaged surface layers, sampled by submersible or ROV. For example, downcore nitrate depletion occurred between 6 and 22 cmbsf for the Kazan mud volcano, and indirect evidence points to oxygen penetration within the upper 6 cm. Nitrate remained near 1–2 μM in the other two mud volcano sites (Amsterdam and Napoli), and no oxygen penetration could be inferred (Heijs et al., 2008).

Sulfate was not measurably drawn down at the SPG12 site, nor at the oligotrophic ODP sites 1231 and 1225. Mesotrophic ODP site 1226 displayed sulfate drawdown but not depletion over the entire sampled sediment column, along with apparent metal redox cycling to at least ∼70 mbsf and methanogenesis throughout nearly the entire sediment column. Likewise, the ODP proxy sites from the South China Sea revealed sulfate drawdown but not depletion over several hundred meters of sediment. Sulfate profiles for the shallow Coral Sea cores are incomplete; however, extrapolating from the upper 9 m sulfate profile of Core MD06-3022 (Roussel et al., 2009) suggests a minimum depletion depth of 60 m or greater. The Gulf of Mexico and Peru Margin sites displayed sulfate depletion within tens of meters (D’Hondt et al., 2004), the Peru Trench and Cascadia Margin sites showed sulfate depletion within a few meters (Table 1). Often, porewater sulfate concentrations below depletion depth do not decrease to zero, but fluctuate in the range of 0.5 or 1 mM, reflecting sulfide reoxidation after exposure of sulfidic cores to oxygen. In Mediterranean mud volcano sediments, sulfate was depleted within the ∼40 cm measured for the Amsterdam and Napoli mud volcanoes, while the Kazan seep displayed little to no drawdown of sulfate (Heijs et al., 2008). Geochemical and microbial variability within each mud volcano site is evident from another recent survey of the Kazan mud volcano, where sulfate was drawn down within 25 cm sediment depth (Kormas et al., 2008).

Metal redox cycling

Metal reduction represents a key avenue for anaerobic terminal electron-accepting processes (Thamdrup, 2000). Manganese and iron reduction are both typical suboxic processes (Berner, 1981), with manganese reduction comparable to nitrate reduction, and reduction of amorphous iron oxyhydroxides closer to sulfate reduction in energy yield (Lovley and Goodwin, 1988). However, the fact that iron reduction involves both soluble and solid reactants and products, and the different bioavailability of different iron oxide phases, complicate iron geochemistry by introducing additional contingent factors. These include chemical surface inactivation (Fredrickson et al., 1998; Urrutia et al., 1998, 1999); retention of reduced iron in clay lattices, which counteracts product inhibition of iron reduction (König et al., 1997, 1999) and favors increased in situ free-energy yields for iron reduction; and the pH and phase dependence of free-energy yields (Postma and Jakobsen, 1996; Fredrickson et al., 1998), which may result in higher in situ energy yields for sulfate reduction. In particular, precipitation of the reduced byproducts of sulfate and iron reduction results in a mutualistic positive feedback that equalizes energy yields for both (Wang et al., 2008, 2010b). Together, these factors allow recalcitrant metal oxides to persist deep in anoxic zones (D’Hondt et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008, 2010b), while Mn and reactive Fe(III) are mostly reduced nearer to the sediment-water interface (König et al., 1997; Thamdrup, 2000; Wang et al., 2008).

Sediment redox state can be characterized by considering iron and sulfate reduction together. Ultraoligotrophic, oxic site SPG11 shows no evidence of either iron or sulfate reduction (Table 1). The anaerobic, oligotrophic sites SPG12, 1225, and 1231 display net iron reduction but no sulfide production. In mesotrophic and eutrophic sites from the South China Sea, Coral Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the Peru Margin, Peru Trench, and Cascadia Margin, the precipitation of metal sulfides indicates co-occurring sulfate and iron reduction. Table 1 presents presence/absence patterns for sulfide and reduced metals for different sites, using both direct measurement of sulfide (Leg 201 and Mediterranean sites), dissolved porewater iron and manganese (Leg 201, Leg 204, and IODP 308 sediments), as well as indirect indicators for the presence or absence of reduced sulfur and metal species, such as a measured lack of net sulfate reduction (SPG12, SPG11), the presence of authigenic sulfide minerals (Leg 184, Leg 204), or brown–green color transitions (König et al., 1997; Thamdrup, 2000) that are an indicator of sedimentary Fe(III)/Fe(II) redox fronts (SPG12, Leg 184 sites, ZoNéCo sites, IODP308 sites).

Sediment trophic state hierarchy

In terms of electron acceptor gradients, oxygen and nitrate penetration over tens of centimeters to meters, and the absence of sulfate depletion, characterize the oligotrophic sites SPG12, ODP 1231, and ODP 1225; the lack of oxygen depletion at SPG11 sets this ultraoligotrophic site apart. Based on cell densities, nitrate and oxygen penetration depth, sedimentation rate, and possibly maximum DIC value, SPG12 is the most organic-lean among the oligotrophic sites, which would also include ODP deepwater sites 1231 and 1225. ODP Site 1226 and the South China Sea sites displayed sulfate drawdown but not depletion several hundred meters deep into the sediment, with the Coral Sea and the Fairway Basin also possibly in that category, suggesting a “mesotrophic” label for these sites. By contrast, eutrophic sites have oxygen and nitrate penetration depths of mere centimeters to millimeters, and sulfate depletion depths of tens of meters or less. The Gulf of Mexico Expedition 308 sites show a curious mixture of eutrophic characteristics (high DIC and NH4 porewater concentration maxima, very high sedimentation rates) combined with mesotrophic (low TOC content) or even oligotrophic characteristics (very low cell numbers). The fully eutrophic sediments are represented by the Peru Margin, Peru Trench, and Cascadia Margin sites. Where available, DIC and NH4 porewater concentrations are perhaps the most reliable trophic state indicators, as they directly reflect the rate and amount of biomass recycled by microbial communities. Maximum DIC values range from seawater concentrations for ultraoligotrophic SPG11, to >10 mM for mesotrophic sites, and significantly more for eutrophic sites (Table 1). Maximum NH4 values range from below detection for the ultraoligotrophic SPG sites, to ca. 0.5–2 mM for mesotrophic sites, and to >3 mM for eutrophic sites (Table 1).

Phylogeny of Oligotrophic Archaea

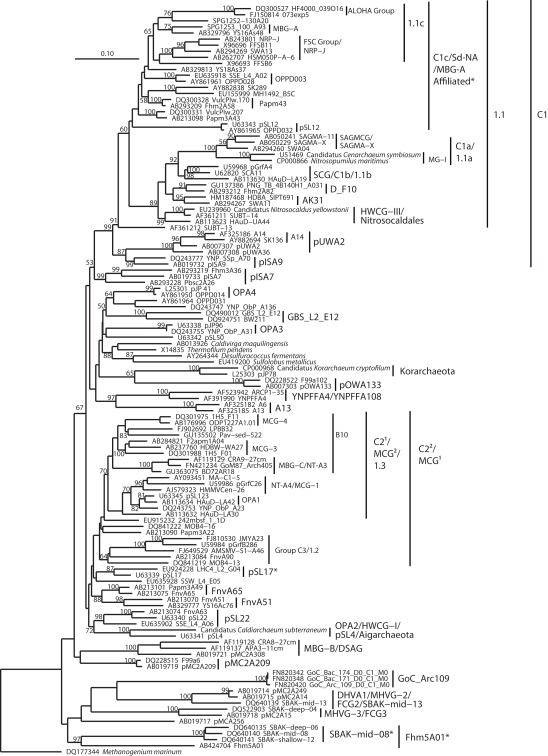

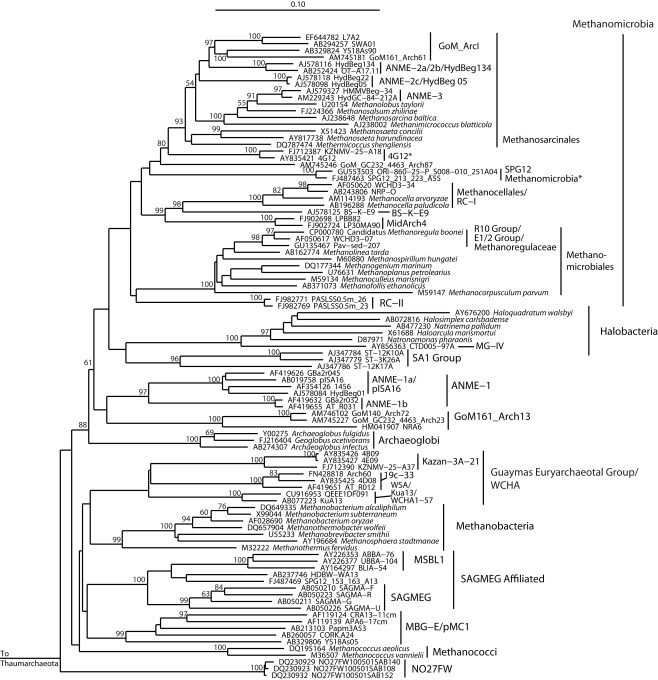

A key problem in surveying the archaeal diversity of marine sediments is reliably defining phylogenetically meaningful groups. Long branch attraction, hyperthermophile high-GC convergence (Boussau and Gouy, 2006; Brochier-Armanet et al., 2008), and chimeric sequences in public databases (Hugenholtz and Huber, 2003; Ashelford et al., 2005) result in statistically poorly supported clades – often para- or polyphyletic on closer inspection – that are highly dependent on details of species selection, and have little use in a phylogenetic context, but that are nevertheless reported in the literature. A related complication is the proliferation of different names for equivalent groups or nearly equivalent groups, which hampers comparability of results. As an attempt to address some of these difficulties, we constructed phylogenies of the major archaeal lineages (Figure 2), of the Euryarchaeota (Figures 3–5) and Crenarchaeota (Figure 6), which reflect the nomenclature introduced by a range of studies (Tables 2 and 3). Although these phylogenies do not address the deep relationships between archaeal phyla, such as the placement of Micrarchaeum and Parvarchaeum, and the grouping of Archaeoglobi, Methanomicrobia, and Halobacteria, these phylogenies are similar to well-supported clades reported in previous studies (e.g., Brochier-Armanet et al., 2008; Baker et al., 2010). Particular attention was given to the Thermoplasmata (Figure 5), in an effort to distinguish phylogenetically valid clades, alongside the organic-rich-associated MBG-D clade, that occur in oligotrophic sediments. The phylogenetic structure of the uncultured Thermoplasmata, and other highly diversified groups, such as the MCG archaea, remains a work in progress.

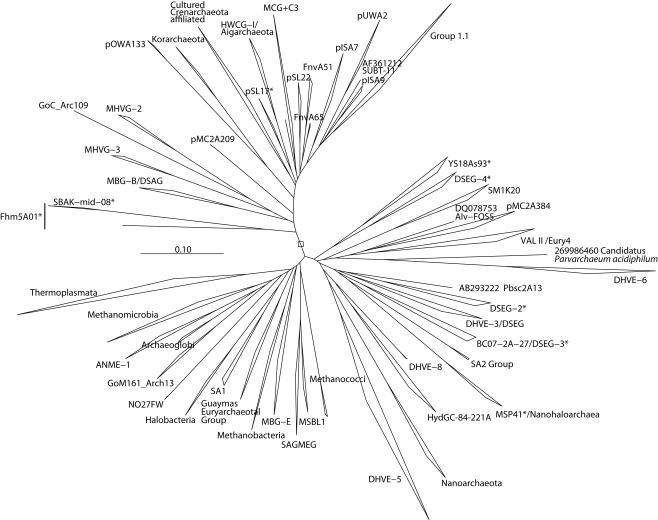

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic context of major phylum or class-level lineages of cultured and uncultured Archaea, as estimated by the ARB neighbor-joining algorithm. Sites with nucleotides at least 60% conserved within all Euryarchaeota included in the tree were used in the analysis for Euryarchaeota and Crenarchaeota together. Certain lineages, such as Methanopyrus kandleri, were excluded due to their tendency to attract hyperthermophiles to the base of the tree.

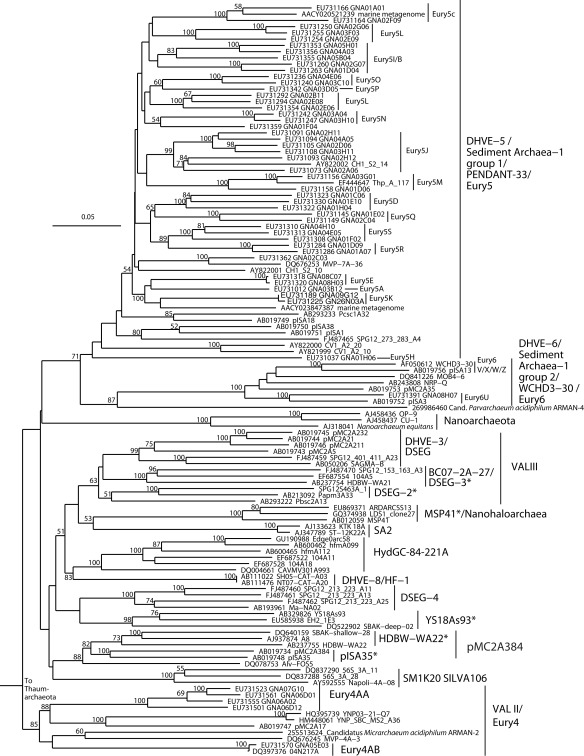

Figure 3.

Neighbor-joining 16S rRNA gene phylogeny of apparently deeply branching Euryarchaeota, designated DHVEG-II after Takai and Horikoshi (1999). Alignment size, filtered using the arch_ssuref mask available in ARB, is 1090 sites. Statistical support was estimated using 500 maximum likelihood bootstrap replications in TreeFinder (Jobb et al., 2004). Branches are annotated with names and acronyms that are used in the literature (Table 3). The archaeal taxa marked with asterisks are novel designations introduced either in Durbin and Teske, 2011 or in this study (Table 3).

Figure 5.

Neighbor-joining 16S rRNA gene phylogeny of Thermoplasmata-affiliated monophyletic lineages in the Euryarchaeota. Alignment size, filtered using the arch_ssuref mask available in ARB, is 1145 sites. Statistical support was estimated using 500 maximum likelihood bootstrap replications in TreeFinder (Jobb et al., 2004). Branches are annotated with names and acronyms that are used in the literature (Table 3). The archaeal taxa marked with asterisks are novel designations introduced either in Durbin and Teske, 2011 or in this study (Table 3).

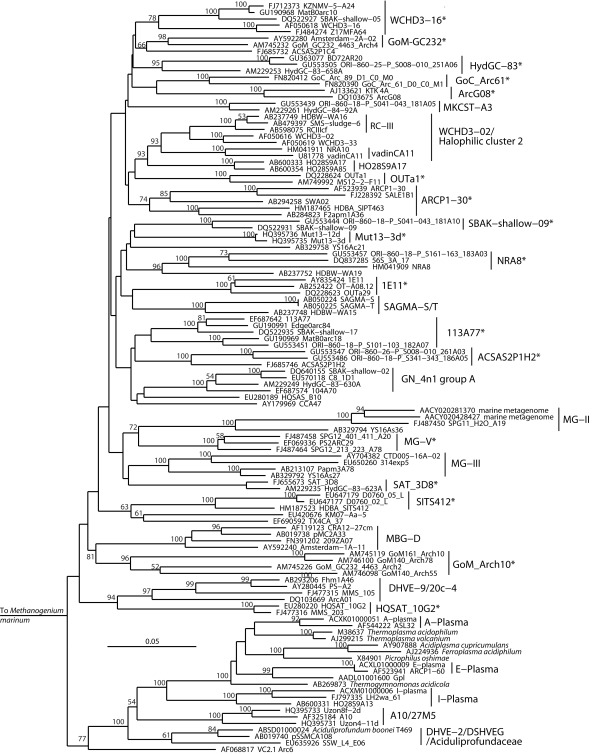

Figure 6.

Neighbor-joining 16S rRNA gene phylogeny of Crenarchaeota/Thaumarchaeota and associated deeply branching lineages. Alignment size, filtered using the arch_ssuref mask available in ARB, is 1177 sites. Bootstrap support was estimated using 500 maximum likelihood bootstrap replications in TreeFinder (Jobb et al., 2004). Branches are annotated with names and acronyms that are used in the literature (Table 3). The archaeal taxa marked with asterisks are novel designations introduced either in Durbin and Teske, 2011 or in this study (Table 3). Note that further MBG-B groups are defined in Robertson et al. (2009).

Table 2.

Relevant methodological features for the archaeal clone library studies compared in this review.

| Study site | Extraction depths, mbsf | Extraction protocol | DNA or RNA? | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Primer annealing temp.°C | Pre-screening | No. of clones, MG-I excluded | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPG12 | 0.60–4.11 | S, BB, PC | DNA | 8f | 1492r | 55 | No | 320 | Durbin and Teske (2011) |

| ODP 201: Site 1231 | 1–43 | S, BB, PC; S, EL, PC | DNA | 8f ▶ 344f | 1492r ▶ 915r | 58 | No | 124 | Sørensen et al. (2004) |

| ODP 201: Site 1225 | 1.5, 7.8 | S, EL, PC | DNA | 8f ▶ 8f | 1492r ▶ 915r | 58 | No | 18 | Teske (2006) |

| ODP 201: Site 1226 | 1.3–45.2 | S, BB | DNA | 21f | 915r | 58 | No | 32 | Biddle et al. (unpublished) |

| ZoNéCo-12 | 0.2–9.4 | S, BB | DNA | 8f ▶ 344f | 1492r ▶ 915r | 51 ▶ 57 | No | 280 | Roussel et al. (2009) |

| MD05-2902 | 0.0–9.42 | S, HT, HS, EL, PC | DNA | 21f | 958r | 55 | T-RFLP | 1078 | Wang et al. (2010a) |

| MD05-2896 | 0.05–11.03 | S, HT, HS, EL, PC | DNA | 21f | 958r | 55 | T-RFLP | 1212 | Wang et al. (2010a) |

| IODP 308: | |||||||||

| Site 1319 | 4.3–76.9, | S, BB | DNA | 21f | 958r | 50 | No | 287 | Nunoura et al. (2009) |

| Site 1320 | 2.9–256.9 | DNA | |||||||

| ODP 201: Site 1227 | 6.55–45.35, 1–50 37.8 | S, BB, PC | RNA DNA RNA | 8f 21f 8f | 915r 958r 915r | 58 50 58 | No No No | Sørensen and Teske (2006) Inagaki et al. (2006) Biddle et al. (2006) | |

| ODP 201: Site 1229 | 29.4, 86.8; 6.7–86.7 | S, BB, PC | RNA DNA | 8f 109f | 915r 958r | 58 45-42 | No No | Biddle et al. (2006) Parkes et al. (2005) | |

| ODP 201: Site 1230 | 11 1–278 | S, BB, PC | RNA DNA | 8f 21f | 915r 958r | 58 50 | No No | 1347 | Biddle et al. (2006) Inagaki et al. (2006) |

| ODP 204: | |||||||||

| Site 1244 Site 1245 Site 1251 | 0.45–129.2 157.9–194.7 4.5–330.6 | S, BB | DNA | 349f | 806r | 50 | No | 470 | Nunoura et al. (2008) |

| Cold seeps: | |||||||||

| Napoli Kazan | 0.0–0.28 0.0–0.34 | S, BB, EL, PC | DNA | 21f 21f ▶ 21f | 1406r 1406 ▶ 958r | 57.5 | No | 237 | Heijs et al. (2008) |

| Amsterdam | 0.0–0.31 | 21f | 1406r | ||||||

| Outgroups: | |||||||||

| Anoxic digestor | HT, EL, PC | DNA | 21f | 1390r | 59 | No | 271 | Chouari et al. (2005) | |

| Reindeer rumen | S, BB | DNA | Met86F | Met1340R | 53 | No | 97 | Sundset et al. (2009) |

Extraction protocol column lists key features of nucleic acid extractions: S, use of sodium dodecyl sulfate as a membrane disruption agent; HT, high temperature (membrane disruptor); HS, high salt (membrane disruptor); BB, using of bead beating as means of cell lysis; EL, enzymatic cell lysis; PC, phenol–chloroform extraction and purification. If nested amplification was used, nested primer set is indicated by carrot; multiple primer sets used in parallel separated by comma. Pre-screening indicates whether entire clone libraries were sequenced, or phylotype abundances in clone libraries were extrapolated based on T-RFLP screening and sequencing of unique T-RFLP profiles. Primer references: 8f, 1492r, Teske et al. (2002); 21f, 915r, 958r, DeLong (1992); 1406r, Lane (1991); 1390r, Zheng et al. (1996); Met96F, Met1340R, Wright and Pimm (2003); 344f, Sørensen et al. (2004); 109f, Groβkopf et al. (1998a); 349f, Takai and Horikoshi (2000).

Table 3.

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 | Figure 5 | Figure 6 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC07-2A-27 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | 19c-33 | SILVA 106 | 1E11 | *Novel | 1.1 | Ochsenreiter et al. (2003) | |

| DHVE-3 | Takai and Horikoshi (1999) | 4G12 | *Novel | 113A77 | *Novel | 1.2 | Ochsenreiter et al. (2003) | |

| DHVE-5 | Takai and Horikoshi (1999) | ANME-1 | Hinrichs et al. (1999) | 20c-4 | SILVA 106 | 1.3 | Ochsenreiter et al. (2003) | |

| DHVE-6 | Takai and Horikoshi (1999) | ANME-1a | Teske et al. (2002) | 27M5 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | 1.1a | Ochsenreiter et al. (2003) | |

| DHVE-8 | Nercessian et al. (2003) | ANME-1b | Teske et al. (2002) | A-Plasma | Dick et al. (2009) | 1.1b | Ochsenreiter et al. (2003) | |

| DSEG | Takai et al. (2001) | ANME-2C | Orphan et al. (2001) | A10 | SILVA 106 | 1.1c | Ochsenreiter et al. (2003) | |

| DSEG-2 | *Durbin and Teske (2011) | ANME-3 | Knittel et al. (2005) | ACSAS2P1C4 | *Novel | A13 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |

| DSEG-3 | *Durbin and Teske (2011) | ANME-2a/2b | Orphan et al. (2001) | ACSAs2P1H2 | *Novel | A14 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |

| DSEG-4 | *Durbin and Teske (2011) | BS-K-E9 | SILVA 106 | ArcG08 | *Novel | AK31 | SILVA 106 | |

| Eury4 | Robertson et al. (2009) | E1/2 Group | Cadillo-Quiroz et al. (2006) | ARCp1-30 | *Novel | Aloha Group | Pester et al. (2011) | |

| Eury4AA | Robertson et al. (2009) | GoM_ArcI | SILVA 106 | DHVE-2 | Takai and Horikoshi (1999) | B10 | McDonald et al. (2011) | |

| Eury4AB | Robertson et al. (2009) | GoM161_Arch13 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | DHVE-9 | Pagé et al. (2004) | C1 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |

| Eury5 | Robertson et al. (2009) | HA1-57 | SILVA 106 | DSHVEG | Takai et al. (2001) | C1a | Hugenholtz (2002) | |

| Eury5c | Robertson et al. (2009) | HydBeg134 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | E-Plasma | Dick et al. (2009) | C1b | Hugenholtz (2002) | |

| Eury5D | Robertson et al. (2009) | Kazan-3A-21 | SILVA 106 | GN_4n1 group A | Jahnke et al. (2008) | C1c | Hugenholtz (2002) | |

| Eury5E | Robertson et al. (2009) | Kua13 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | GoC_Arc61* | *Novel | C21 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |

| Eury5H | Robertson et al. (2009) | MBG-E | Vetriani et al. (1999) | GoM_Arch10 | *Novel | C22 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |

| Eury5I/B | Robertson et al. (2009) | MG-IV | López-Garcia et al. (2001) | Halophilic cluster 2 | Jahnke et al. (2008) | C3 | Hales et al. (1996) | |

| Eury5J | Robertson et al. (2009) | MidArch4 | SILVA 106 | HO28S9A17 | SILVA 106 | C3 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |

| Eury5K | Robertson et al. (2009) | MSBL1 | Van der Wielen et al. (2005) | HQSAT_10G2 | *Novel | D_F10 | SILVA 106 | |

| Eury5L | Robertson et al. (2009) | NO27FW | DeSantis et al. (2006) | HydGC-83 | *Novel | DHVA1 | Takai and Horikoshi (1999) | |

| Eury5L | Robertson et al. (2009) | pISA16 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | I-Plasma | Dick et al. (2009) | DSAG | Takai et al. (2001) | |

| Eury5M | Robertson et al. (2009) | pMC1 | Hugenholtz (2002) | KM07 | *Novel | FCG2 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |

| Eury5N | Robertson et al. (2009) | pMC1 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | MBG-D | Vetriani et al. (1999) | FCG3 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |

| Eury5O | Robertson et al. (2009) | R10 Group | Hales et al. (1996) | MG-II | Fuhrman et al. (1992) | Fhm5A01 | *Novel | |

| Eury5P | Robertson et al. (2009) | RC-I | Groβkopf et al. (1998b) | MG-III | Fuhrman and Davis (1997) | FnvA51 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |

| Eury5Q | Robertson et al. (2009) | RC-II | Groβkopf et al. (1998b) | MG-V | *Durbin and Teske (2011) | FnvA65 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |

| Eury5R | Robertson et al. (2009) | SAGMEG | Takai et al. (2001) | MKCST-A3 | SILVA 106 | FSC Group | Takai et al. (2001) | |

| Eury5S | Robertson et al. (2009) | SAGMEG-Affiliated | *Novel | Mut13-3d | *Novel | GBS_L2_E12 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |

| Eury6 | Robertson et al. (2009) | Methanomicrobia | *Durbin and Teske (2011) | NRA8 | *Novel | GoC_Arc109 | SILVA 106 | |

| Eury6U | Robertson et al. (2009) | WSA | Hugenholtz (2002) | OUTa1 | *Novel | HWCG-I | Nunoura et al. (2005) | |

| Eury6V/X/W/Z | Robertson et al. (2009) | SAGMA-S/T | Schleper et al. (2005) | HWCG-III | Nunoura et al. (2005) | |||

| HDBW-WA22 | *Novel | SAT_3D8 | *Novel | MBG-A | Vetriani et al. (1999) | |||

| HF-1 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | SBAK-shallow-09 | *Novel | MBG-A Affiliated | *Novel | |||

| HydGC-84-221A | McDonald et al. (2011) | SITS412 | *Novel | MBG-B | Vetriani et al. (1999) | |||

| MSP41 | *Novel | vadinCA11 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | MBG-C | Vetriani et al. (1999) | |||

| Nanohaloarchaea | Narasingarao et al. (2012) | |||||||

| PENDANT-33 | Schleper et al. (2005) | vadinCA11 | SILVA 106 | MCG-1 | Inagaki et al. (2003) | |||

| pISA35 | *Novel | WCHD3-02 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | MCG2 | Inagaki et al. (2006) | |||

| pMC2A384 | McDonald et al. (2011) | WCHD3-16 | *Novel | MCG-1 | Teske and Sørensen (2008) | |||

| SA2 | Eder et al. (2002) | MCG-3 | Teske and Sørensen (2008) | |||||

| Sediment Archaea-1 group 1 | Hugenholtz (2002) | MCG-4 | Teske and Sørensen (2008) | |||||

| Sediment Archaea-1 group 2 | Hugenholtz (2002) | MG-I | DeLong (1992) | |||||

| SM1K20 | SILVA 106 | MG-I | Fuhrman et al. (1992) | |||||

| VAL II | Jurgens et al., 2000 | MHVG-2 | Takai et al. (2001) | |||||

| VALIII | Jurgens et al., 2000 | MHVG-3 | Takai et al. (2001) | |||||

| WCHD3-30 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | NRP-J | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||

| YS18As93 | *Novel | NT-A3 | Reed et al. (2002) | |||||

| NT-A4 | Reed et al. (2002) | |||||||

| OPA1 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |||||||

| OPA2 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |||||||

| OPA3 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |||||||

| OPA4 | Hugenholtz (2002) | |||||||

| OPPD003 | SILVA 106 | |||||||

| Papm43 | SILVA 106 | |||||||

| pISA7 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| pISA9 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| pMC2A209 | SILVA 106 | |||||||

| pOWA133 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| pSL12 | SILVA 106 | |||||||

| pSL17 | *Novel | |||||||

| pSL22 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| pSL4 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| pUWA2 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| SAGMA-X | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| SAGMCG | Takai et al. (2001) | |||||||

| SBAK-mid-08 | *Novel | |||||||

| SBAK-mid-13 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| SCG | Takai et al. (2001) | |||||||

| Sd-NA | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

| YNPFFA4/YNPFFA108 | DeSantis et al. (2006) | |||||||

Archaeal Occurrence Trends Across Sites

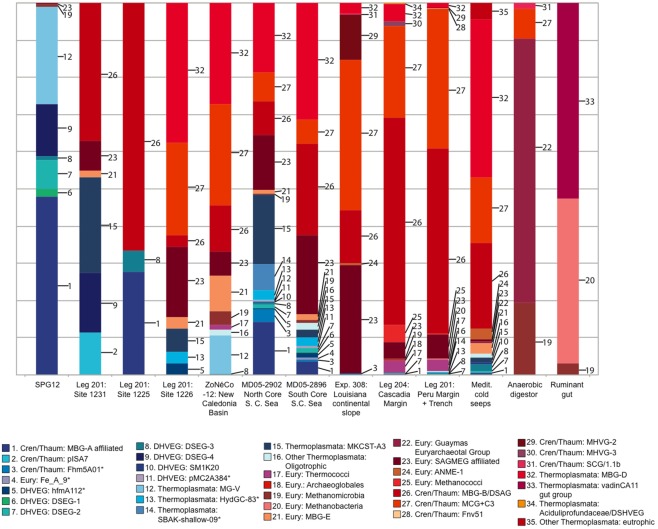

Relative abundances of deeply branching Archaeal lineages in 16S rRNA gene clone libraries from oligotrophic and organic-rich sediments are compiled in Figure 7. These 16S rRNA gene clone library data should not be understood as accurate proportional representation of archaeal lineages in the environment; diverging methodologies, clone library size limitations and the resulting detection thresholds qualify what is subsequently called “abundance.” High-throughput sequencing approaches are very likely to modify these initial clone library-based surveys (Biddle et al., 2008, 2011). Yet, the clone library data provide a window into distinctly different detection patterns of archaeal clades within organic-lean and organic-rich sediments. All clades absent from eutrophic sites, or which occur at less than 1.5% relative abundance in any eutrophic site, are colored blue (numbers 1-16 in Figure 7). Those clades found only in the eutrophic end-member sites, or which occur in these sites at more than 1.5% frequency, are colored red. Overall, archaeal phyla that predominate either in the oligotrophic or in the eutrophic endmember sites are declining in relative abundance along environmental gradients of redox state, organic carbon content and biomass remineralization (Figure 7; Table 1). Dominant benthic archaeal groups of organic-rich sediments disappear in the most oxidized sediment environments, and vice versa.

Figure 7.

Representation of archaeal lineages in 16S rRNA gene clone libraries across a spectrum of oligotrophic to eutrophic marine subsurface sediments. The sites are arranged from oligotrophic (left) to eutrophic (right). Clades 1–16, colored blue, were either entirely absent from eutrophic sites, or comprised less than 1.5% of total clones in any eutrophic site. Some archaeal datasets were pooled from multiple sites of a geographic region (Brazos Basin, Peru Margin/Trench, Cascadia Margin, Mediterranean seeps). For Peru Margin/Trench sites, sequences labeled “Thermococci” (Inagaki et al., 2006) also include an unspecified number of Methanococci. As outgroup examples of anaerobic, extremely organic-rich environments, an anaerobic wastewater digestor (Chouari et al., 2005) and a ruminant foregut (Sundset et al., 2009) are included.

A specific archaeal assemblage of MBG-B, MCG, SAGMEG and MBG-D archaea is found repeatedly in the eutrophic subsurface sediments of the Peru Margin (ODP sites 1227,1229), Peru Trench (ODP site 1230), Cascadia Margin (ODP sites 1244, 1245, 1251), and the highly reducing Mediterranean methane seeps, and also in the Gulf of Mexico 308 sites with mixed eutrophic/mesotrophic/oligotrophic characteristics. These uncultured archaeal lineages that are commonly detected in clone libraries (Table 2) should be congruent with the cren- and euryarcheotal proportion (15–45%) of phylogenetically informative pyrosequencing fragments in the Peru Margin and Brazos Basin metagenomes (Biddle et al., 2008, 2011). The archaeal groups that are typically found in eutrophic sediments also persist to a considerable extent into organic-leaner sediments. For example, MCG is found in all mesotrophic sites in the South China Sea, Fairway Basin, and ODP site 1226; MBG-B persists in the same sites in the mesotrophic spectrum, and also in ODP sites 1225 and 1231 (Figure 7). Some members of these and other archaeal clades that are typically found in anaerobic, eutrophic marine sediments also occur in reducing, non-marine habitats. For example, the MCG occurred in the anaerobic digestor and in several marine samples; the Guaymas Euryarchaeotal Group (Dhillon et al., 2005) was also found in the anaerobic digestor (Chouari et al., 2005) and in the Mediterranean methane seeps (Heijs et al., 2008); and methanogens were recovered in the rumen library and among the Peru Margin/Trench sequences.

The oligotrophic end of the sediment spectrum starts with an entirely different archaeal community. The most oligotrophic site featured in Table 1 is SPG11, where oxygen is present throughout the measured sediment column and DIC (alkalinity) does not vary from seawater values (D’Hondt et al., 2009). All archaeal sequences recovered for this site were members of MG-I, and formed sediment-specific clades within this lineage (Durbin and Teske, 2010). However, MG-I archaea also appear occasionally in very deep sediment samples (such as ODP1230; Inagaki et al., 2006) where they almost certainly represent seawater or drilling fluid contamination; for this reason, MG-I archaea are not included in Figure 7. The oligotrophic site SPG12 resembles SPG11 in the dominance of MG-1 archaea (subsurface clusters) in the upper sediment layers and lacks the typical archaea of eutrophic sites (MCG, MBG-B, MBG-D); only a single SAGMEG-related clone and two divergent Methanogen-affiliated clones were recovered from SPG12. The dominant archaea at SPG12, including MG-V, DSEG-2, DSEG-4, and the MBG-A-related lineages, were not recovered from any of the organic-rich sediments (Figure 7). ODP sites 1225 and 1231 resemble SPG12 geochemically and microbiologically. Their clone libraries include a significant proportion of groups found in organic-lean sites (DSEG-4, MBG-A), but also include some groups abundant at eutrophic sites (MBG-B).

The intermediate, mesophilic spectrum includes ODP site 1226, and the South China and Coral Sea sites. In comparison to oligotrophic sites, these sites yielded a smaller proportion of lineages typical for organic-lean sites, congruent with more organic-rich habitat characteristics. As a caveat, the South China and Coral Sea cores are relatively shallow; deeper coring and sampling in these locations might impact the archaeal diversity results. The impact of shallow sampling can be seen in the detection of organic-lean archaeal lineages in the Mediterranean cold seep dataset, attributable to the shallow horizons sampled as well as the geochemically heterogeneous nature of cold seeps that are surrounded by organic-lean deep-sea sediments (Figure 7).

Despite these complications, the proportion of lineages common in organic-lean sediments decreases as measures of sediment organic richness increase. Certain archaeal clades occur – in changing configuration – in oligotrophic sediments, but do not occur or occur only rarely in eutrophic sediments. There are three likely drivers of such a changes in community composition:

-

(1)

Refractory organic matter. Organic matter changes significantly in composition and quantity during sinking, and is expected to become more refractory overall after passage through the deep-sea water column (Wakeham et al., 1997). Microbes that can metabolize the highly refractory substrates in oligotrophic sediments where competition for electron donors is strong would have an advantage over microbes not able to use these substrates.

-

(2)

Low sedimentation rates. Oligotrophic sediments are primarily characterized by slow sedimentation rates, leading to a low substrate flux for microbes and hence energy limitation. As the incoming carbon substrates are microbially degraded, increasingly recalcitrant compounds become enriched.

-

(3)

Deep permeation of high-energy electron acceptors. Since decreasing sedimentation and carbon flux leads to slower depletion of electron acceptors, energy-rich electron acceptors (oxygen, nitrate) permeate a larger depth range of the sediment column in oligotrophic sediments, in contrast to the surficial sediments to which they are confined otherwise. Thus, some subsurface Archaea may specialize in the electron acceptor that maximizes the energy yield for a given substrate, and this leads to the predominance of specific archaeal lineages in oligotrophic sediments.

These variables are expected to be congruent to some degree. It also seems likely that some combination of these three factors determines community composition: while electron acceptor specialization may be a determinative factor for one group, another group may thrive since it uses a particularly recalcitrant carbon substrate.

This discussion of low-energy adaptations of microbial cells in oxidized, oligotrophic sediments should not distract from the fact that low-energy adaptations should also apply to microorganisms in organic-rich subsurface sediments where the lack of high-energy electron acceptors and of fresh carbon substrates impose very low free-energy fluxes at or near maintenance-energy requirements (Lever et al., 2010), such that microbial activity persists in sediment horizons over geological time scales (Parkes et al., 2005) and sustains very slow biomass turnover on time frames ranging from years to millennia (Jørgensen, 2011). The different archaeal communities in oligotrophic and eutrophic sediments should not be viewed in terms of simplistic “low-energy vs. high energy” habitat characteristics; instead, the distinct reduction potentials, substrate spectra, electron donors, and acceptors in oligotrophic and eutrophic sediment environments determine which catabolic, carbon-fixing, and biosynthetic pathways are feasible (McCollom and Amend, 2005).

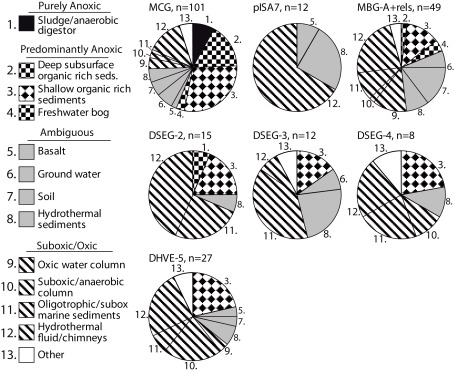

Association of Archaeal Lineages with High-Energy Electron Acceptors

The link between redox specialization and specific benthic archaeal lineages is not limited to sedimentary habitats: archaeal clades typical for oligotrophic sediments appear frequently in other oxic or suboxic environments, and less often in anoxic environments. In other words, mutually independent clone library surveys demonstrate that a given archaeal lineage is preferentially found in a particular redox environment. Figure 8 shows the number of different studies that have recovered a given lineage from a particular redox environment, for all relevant sequences in the SILVA SSU Ref v.95 database (Pruesse et al., 2007). Based on geochemical metadata for each sequence data set, the redox status of the environments considered was conservatively identified as purely anoxic, predominantly anoxic, ambiguous, and suboxic/oxic (Figure 8). Methodological biases inherent in DNA extraction method, PCR primer selection and cloning methodology rule out a strict proportionality of geochemical regime to clone library membership and relative abundance (Teske and Sørensen, 2008). Therefore, these cumulative presence/absence data can be thought of as “averaging” of experimental variability associated with PCR surveys of microbial diversity.

Figure 8.

Habitat–lineage association showing the number of different studies that have recovered oligotrophic lineages that are rarely or not found in eutrophic sediments from a particular redox environment. All sequences belonging to the relevant clades in SILVA SSU Ref V.95 (Pruesse et al., 2007) were examined by counting each instance of a clade being recovered within a specific study and habitat; the habitats were then cataloged and categorized as anoxic, oxic/suboxic, or ambiguous in cases of uncertain or heterogeneous redox status. See text for explanation of habitat redox categorization.

Notably, lineages from oxidized, organic-lean sediments have not been recovered from purely anoxic environments such as anaerobic digestors, indicating basic physiological incompatibility (Figure 8). However, some predominantly anoxic sites, mostly shallow organic-rich sediments, harbor lineages that are commonly found in oxidized sediments (Figure 8). These organic-rich sediment environments can be distinguished from the purely anoxic environments (such as anoxic bioreactors) because they often have oxidized niches or micro-environments that co-occur with anoxic niches (e.g., Jørgensen, 1977; Mäkelä and Tuominen, 2003; Jørgensen et al., 2005; Glud, 2008), particularly for near-shore marine sediments where weathering mineral input may introduce significant quantities of metal oxides (Poulton and Raiswell, 2002). These permeable boundaries between sediment habitat types might also work the other way around. For example, a key component of organic-rich, reduced marine subsurface sediments, the MCG archaea, also occur in freshwater bogs and in surficial, partially oxidized sediments (Kubo et al., 2012).

Hydrothermal fluids are often highly reduced and anoxic at their source, but turn more oxidized within the thermally habitable mixing gradient between an anoxic, hydrothermal source fluid, and an oxic endmember such as seawater, oxygenated groundwater, or atmosphere-exposed surface water (e.g., Amend and Shock, 1998; Teske et al., 2002; Spear et al., 2005; Dias and Barriga, 2006; Rogers and Amend, 2006). As a consequence of hydrothermal convection and seawater admixture, archaeal lineages that are associated with oxidized, organic-lean sediments could thrive in the shallow, partially mixed and partially oxidized vent subsurface, and are then frequently recovered from hydrothermal fluids (Figure 8). The second largest group of source habitats for these archaeal lineages that tolerate partially oxidized conditions are environments with heterogeneous or variable redox states, such as soil (Conrad, 1996), ground water (Jakobsen, 2007), and surficial hydrothermally influenced sediments and mineral deposits permeated by hydrothermal fluid (Teske et al., 2002; Nercessian et al., 2005; Dias and Barriga, 2006; Severmann et al., 2006). These habitats provide access to high-energy electron acceptor niches.

Thus, partially oxidized environments, including oxic/suboxic sediments or water column, and the redox-oscillating environments of hydrothermal fluids and chimney surfaces, account for a majority or plurality of detection of organic-lean archaeal lineages, such as the pISA7 Crenarchaeotal and the DHVEG-II Euryarchaeotal lineages (Figure 8). As a caveat, these trends are suggestive but require consistency checks over increasingly fine-grained phylogenetic scales; minority clades within lineages may have metabolisms that are atypical for that lineage. The observed patterns also reflect uncertainty in identifying the exact redox state of the environment from which the clone was recovered, particularly problematic for datasets with sketchy or unspecific sequence-source descriptions. With these limitations, these results are again compatible with a metabolism requiring high-energy electron acceptors and oxidized redox conditions for the archaeal lineages from organic-lean habitats.

Problems and Prospects for Future Research

Considerable uncertainty remains regarding the phylogeographic trends described and their putative link to environmental redox state. Principally, these uncertainties revolve around the familiar problems of primer and PCR bias, the significant variation in availability of key geochemical measurements, and the meager database especially at the oligotrophic end of the spectrum. Improving the cross-comparability of 16S rRNA survey data would require consistent molecular methodology as well as unified geochemical metadata across a wide range of marine sediment environments; this problem is acute in large-scale molecular surveys of the marine microbial world (Zinger et al., 2011). New sampling sites with good metadata, for example the oligotrophic sediments of North Pond underlying the North Atlantic subtropical gyre, are being explored (Ziebis et al., 2012) and will enlarge the molecular database as well. Additional evidence from cultivations, genome sequencing, and environmental genomics, is needed to further query the functional repertoire of archaeal 16S rRNA lineages. For example, genome analysis, enrichments, and cultivations of Thaumarchaeota (MGI archaea) suggest an ammonia-oxidizing metabolism for this archaeal lineage (Pester et al., 2011), a conclusion at least partially consistent with the largely suboxic/microoxic habitat preferences of the MG-I-related lineages discussed here.

Detailed environmental 16S rRNA surveys and geochemical measurements are complementary to genomic and cultivation approaches, given that neither genomics nor cultivations currently are capable of delivering the phylogenetic resolution or coverage of 16S rRNA surveys. Using such surveys and comprehensive geochemical datasets as hypothesis-generating and -refining tools, one can better constrain the putative redox adaptation of different microbial clades, and thus the role redox adaptation may play as an evolutionary force that shapes the biogeography of deep 16S rRNA clades. One approach would be to examine the hierarchical level at which phylogenetic lineages assort between sediments where the same electron acceptors persist in different environmental contexts, e.g., the spatially expanded suboxic/oxic strata of abyssal sediments and the spatially compressed suboxic/oxic strata perched on top of deep anoxic sediments, or even metal oxides persisting into euxinic sediments. This would allow examination whether factors such as reductant/oxidant concentration or sediment redox potential, as distinct from electron acceptor availability, play key roles in redox adaptation, possibly in determining the type of biosynthetic pathways utilized.

Big-picture studies examining the deep phylogeography of microbes have established that deeply rooted clades indeed assort according to habitat (von Mering et al., 2007), and have additionally revealed several factors that may explain some of the variance observed in archaeal biogeography, with the most important habitat-defining distinctions being salinity and terrestrial vs. aquatic (Auguet et al., 2010). Microbial biogeography has also been explored by focusing on a specific subset of environmental parameters that are hypothesized to determine habitat specialization, revealing, for example, that carbon lability differences between soils correlate with the relative abundance of different bacterial phyla, observations which are in line with hypotheses about the physiology of “copiotroph” or “oligotroph” organisms (Fierer et al., 2007). In a similar fashion, the current review proceeds from the hypothesis that marine sediments of different redox state represent different habitat niches for microbes, and examines the patterns of community membership and abundance across these putative distinct habitats. The definition of distinct redox habitats implies specific microbial activities and physiologies in each habitat; thus, working hypotheses on microbial function emerge from the analysis of diversity patterns across these habitats. However, when comparing different environments defined operationally by one or a few variables, it should be kept in mind that other parameters may co-vary. For example, the freshwater–saltwater biogeographic divide which appears to be rarely crossed in evolution (Logares et al., 2009; Auguet et al., 2010) could be maintained due to differences in exterior osmotic pressure, sulfur compound availability, carbonate speciation, pH, or biosynthetic requirements. Caution in overinterpreting the functional significance of biogeographic patterns is warranted.

Conclusion

Archaeal communities undergo a marked shift along gradients of sediment trophic state. Archaeal lineages found in oligotrophic, oxidized sediments significantly expand the higher-order taxonomic diversity within the Archaea. These lineages have most often been found in other environments that are suboxic or oxic, with some proportion occupying habitats of ambiguous redox state, or primarily anoxic habitats that contains partially oxidized microniches (organic-rich surficial sediments). Such a lineage distribution is consistent with redox specialization determining in large part the distribution of archaeal lineages in the marine subsurface. Since the phylogenetic groups associated with this diversity shift were deeply branching (possibly class or phylum level), redox specialization could represent a fundamental correlate with deep phylogenetic diversification within the archaeal domain. Further studies are needed to resolve the phylogenetic placement of these novel lineages, as well as to explore the how the defining characteristics of oligotrophic sediments – nutrient limitation, oxidized environmental redox state, and availability of high-energy electron acceptors – have shaped archaeal evolution.

Methods for Sampling, Nucleic Acid Extraction, and Diversity Analysis

This study reanalyzes archaeal 16S rRNA sequences from gravity cores at site SPG12, sampled during Cruise Knox02RR to the South Pacific Gyre (D’Hondt et al., 2009; Durbin and Teske, 2010, 2011). Additional published sequences from different marine sediments were used for this study (Table 2); the published sampling procedures are briefly summarized here. Archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences for the Mediterranean cold seeps were derived from the upper 20–30 cm sediments, which were subsampled from a box core using aluminum cores and divided into two or three subsections before freezing (Heijs et al., 2008). Samples from the South China Sea were retrieved via gravity coring and subsampling from the center of the split cores (Wang et al., 2010a), while sediments from the Coral Sea were sampled via piston core and aseptically subsampled (Roussel et al., 2009). Archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences from SPG12 were extracted and amplified from sediments subsampled from gravity core sections using a sterilized cut-off syringe, at a sampling resolution of 10 cm. Archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences for the Gulf of Mexico IODP 308 samples were obtained from advanced piston-cored and XCB-cored sediments at depth horizons 4.45, 12.0, and 77 m of the Brazos Basin core U1319A; and at four depths (2.9, 7.4, 13.9, and ca. 28m) within the sulfate-reducing zone, and 92.4, 226.9, and 256.0 m of Brazos Basin core U1320A (Nunoura et al., 2009). Archaeal 16S sequences for the Peru Margin ODP sites were derived from the upper sulfate-methane transition zone (SMTZ) at site 1227 (37.8 mbsf, Biddle et al., 2006; 35.35, 34.25, 37.75, and 40.35 mbsf, Sørensen and Teske, 2006), as well as intervals above and below the SMTZ (6.55, 7.35, 21.35, 45.35 mbsf; Sørensen and Teske, 2006). Sequences from site 1229 were obtained from the upper and lower SMTZs at 29.4/30.2 and 86.8/86.67, mbsf respectively (Parkes et al., 2005; Biddle et al., 2006), as well as from 6.7 and 42.03 mbsf (Parkes et al., 2005). Site 1230 was sampled at 11.0 mbsf near the SMTZ (Biddle et al., 2006). ODP site 1226 was sampled from approximately 1.3, 7.2, 26.2, and 45.2 mbsf; methane and sulfate coexist throughout the sediment column and suggest that both methanogenesis and sulfate reduction occur. Finally, ODP sites 1244, 1245, and 1251 were sampled mostly below the SMTZ, from 0.45, 6.7, 16.2, 31.2, and 129.2 mbsf (1244), 157.9 and 194.7 mbsf (1245), and 4.5, 22.7, 43.2, 64.2, 82.7, 104.5, 123.1, 142.2, 169.9, 179.9, 204.2, 228.2, and 330.6 mbsf (Nunoura et al., 2008).

Diversity survey methods

While all studies used slightly different nucleic acid extraction protocols (Table 2), most involved chemical cell-membrane disruption with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), mechanical membrane disruption with bead beating, and phenol–chloroform extraction (e.g., Zhou et al., 1996). The sites with the largest sample size and most extensive geochemical data, i.e., SPG12, the Peru Margin and Peru Basin sites, and the Mediterranean cold seeps, all used some variation of a SDS/bead beating/phenol–chloroform based extraction protocol, although some sequences from 1231 were only amplified using an enzymatic-lysis + SDS based extraction (Sørensen et al., 2004). Primers used for 16S rRNA gene amplification differed within and between oligotrophic, mesotrophic, and eutrophic sediments. Primer and PCR bias undoubtedly plays an important, but unknown role in the between-library differences observed for all libraries. Finally, although amplicon size has been shown to influence clone library composition, all amplicons considered here fell into a size range from 850 or 900 nucleotides to 1500 nucleotides (Table 2) in which variation in amplicon size minimally impacts clone library composition (Huber et al., 2009).

Database searches and phylogenetic identification

A search for all available Archaeal 16S sequences from oligotrophic marine sediment sites was conducted first by identifying closest relatives to SPG12 Archaeal sequences via BLAST searches and searches within the ARB v.95 REF 16S/18S database (Pruesse et al., 2007). If a sequence was derived from an oligotrophic sediment environment, defined as any marine benthic environment not situated on a continental slope or shelf, all sequences from the associated publication were imported and aligned in ARB (Ludwig et al., 2004). Any closest relatives presented in the associated publication were also imported and aligned. Further internet searches using keywords yielded no additional publications. Studies with archived sequence reads or published abundances of representative phylotypes were then used for comparative analysis. The archaeal ARB file is available from the authors on request (amdurbin@gmail.com; teske@email.unc.edu) or online at http://jmartiny.bio.uci.edu/lab/Data.html.

For all earlier clades subsumed by a later taxonomy, the original definition is depicted, unless the later, subsuming taxonomy significantly expanded or changed the original definition, in which case both are depicted; however, only phylogenetically valid clades were depicted. For example, the GreenGene 2006/2008 taxonomy (DeSantis et al., 2006) subsumed some identical taxonomic designations of Hugenholtz (2002); when valid clades shared the same name but phylogenetically differed between these two taxonomies, both definitions are given. We used the GreenGenes taxonomy according to the November 2008 GreenGenes version (greengenes236469.arb.gz, downloadable from http://greengenes.lbl.gov/Download/Sequence_Data/Arb_databases/), which differed from the original GreenGenes release (DeSantis et al., 2006) by adding a few novel designations. The GreenGenes 2011 release differed substantially from the 2008 release in that it removed many GreenGenes 2008 designations, and added, modified, or kept unmodified relatively few. In this case, only the 2011 additions or modifications were noted according to their 2011 definitions (McDonald et al., 2011), while those designations common to both versions were noted according to the GreenGenes 2008 release (Table 3).

For the Thermoplasmata-affiliated sequences (Figure 5), a lack of monophyletic clades defined for this group was addressed via an extensive analysis including all diversity represented by 16S rRNA gene sequences >1000 bp available in SILVA v.106. In constructing this tree, the primary goal was to create the deepest stable clades achievable using an alignment ∼1000 bp and minimal chimera screening beyond that already performed by SILVA’s Pintail screening, by removing sequences that appear to destabilize clades, avoiding clades with shallow internal branch lengths relative to terminal branch lengths. After amending monophyletic clades with new sequences, the newly populated and expanded clade should be as consistent as its earlier version, with stable bootstrap support and with the same intergroup distance to the neighbor clades. Statistical support was estimated with 500 maximum likelihood bootstrap replications using TreeFinder (Jobb et al., 2004).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the NASA Astrobiology Institutes “Environmental genomes” (NCC 2-1054), “Subsurface biospheres” (NCC 2-1275), and by NSF (NSF-Ocean Drilling Program 0527167). Andreas Teske was further supported by a Hanse Institute Fellowship, and by the Center for Dark Energy Biosphere Investigations (C-DEBI). We thank Jennifer Biddle, Amanda Martino, and Chris House for the summary on the archaeal communities in ODP site 1226 (Figure 4), and Marc Alperin for a thoughtful reading of the manuscript.

Figure 4.

Neighbor-joining 16S rRNA gene phylogeny for clades of cultured and uncultured Euryarchaeota. Alignment size, filtered using the arch_ssuref mask available in ARB, is 1220 sites. Statistical support was estimated using 500 maximum likelihood bootstrap replications in TreeFinder (Jobb et al., 2004). Branches are annotated with names and acronyms that are used in the literature (Table 3). The archaeal taxa marked with asterisks are novel designations introduced either in Durbin and Teske, 2011 or in this study (Table 3).

References

- Agogué H., Brink M., Dinasquet J., Herndl G. J. (2008). Major gradients in putatively nitrifying and non-nitrifying Archaea in the deep North Atlantic. Nature 456, 788–792 10.1038/nature07535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amend J. P., Shock E. L. (1998). Energetics of amino acid synthesis in hydrothermal ecosystems. Science 281, 1659–1662 10.1126/science.281.5383.1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashelford K. E., Chuzhanova N. A., Fry J. C., Jones A. J., Weightman A. J. (2005). At least 1 in 20, 16S rRNA sequence records currently held in public repositories is estimated to contain substantial anomalies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 7724–7736 10.1128/AEM.71.12.7724-7736.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auguet J.-C., Barberan A., Casamayor E. O. (2010). Global ecological patterns in uncultured Archaea. ISME J. 4, 182–190 10.1038/ismej.2009.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B. J., Comolli L. R., Dick G. J., Hauser L. J., Hyatt D., Dill B. D., Land M. L., VerBerkmoes N. C., Hettich R. L., Banfield J. F. (2010). Enigmatic, ultrasmall, uncultivated archaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8806–8811 10.1073/pnas.0914470107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner R. A. (1981). A new geochemical classification of sedimentary environments. J. Sed. Petrol. 51, 359–365 [Google Scholar]

- Biddle J. F., Fitz-Gibbon S., Schuster S. C., Brenchley J. E., House C. H. (2008). Metagenomic signatures of the Peru Margin subseafloor biosphere show a genetically distinct environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10583–10588 10.1073/pnas.0709942105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle J. F., Lipp J. S., Lever M. A., Lloyd K. G., Sørensen K. B., Anderson R., Fredricks H. F., Elvert M., Kelly T. J., Schrag D. P., Sogin M. L., Brenchley J. E., Teske A., House C. H., Hinrichs K.-U. (2006). Heterotrophic Archaea dominate sedimentary subsurface ecosystems off Peru. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 3846–3851 10.1073/pnas.0600035103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]