Abstract

Introduction

Infarction-related cardiogenic shock (ICS) is usually due to left-ventricular pump failure. With a mortality of 30% to 80%, ICS is the most common cause of death from acute myocardial infarction. The S3 guideline presented here characterizes the current evidence-based treatment of ICS: early revascularization, treatment of shock, and intensive care treatment of multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) if it arises. The success or failure of treatment for MODS determines the outcome in ICS.

Methods

Experts from eight German and Austrian specialty societies analyzed approximately 3600 publications that had been retrieved by a systematic literature search. Three interdisciplinary consensus conferences were held, resulting in the issuing of 111 recommendations and algorithms for this S3 guideline.

Results

Early revascularization of the occluded vessel, usually with a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is of paramount importance. The medical treatment of shock consists of dobutamine as the inotropic agent and norepinephrine as the vasopressor of choice and is guided by a combination of pressure and flow values, or by the cardiac power index. Levosimendan can be given in addition to treat catecholamine-resistant shock. For patients with ICS who are treated with PCI, the current S3 guideline differs from the European and American myocardial infarction guidelines with respect to the recommendation for intra-aortic balloon pulsation (IABP): Whereas the former guidelines give a class I recommendation for IABP, this S3 guideline states only that IABP “can” be used in this situation, in view of the poor state of the evidence. Only for patients being treated with systemic fibrinolysis is IABP weakly recommended (IABP “should” be used in such cases). With regard to the optimal intensive-care interventions for the prevention and treatment of MODS, recommendations are given concerning ventilation, nutrition, erythrocyte-concentrate transfusion, prevention of thrombosis and stress ulcers, follow-up care, and rehabilitation.

Discussion

The goal of this S3 guideline is to bring together the types of treatment for ICS that lie in the disciplines of cardiology and intensive-care medicine, as patients with ICS die not only of pump failure, but also (and even more frequently) of MODS. This is the first guideline that adequately emphasizes the significance of MODS as a determinant of the outcome of ICS.

Provided they reach hospital, patients with acute myocardial infarction have a more than 90% probability of surviving (1). If cardiogenic shock develops, however, whether initially or in the course of the infarction, only one in two survives (2). All the progress made in the treatment of myocardial infarction seems to have ground to a halt before these 5% to 10% of heart attack patients: The publication of the most important evidence-based progress in treatment of patients with infarction-related cardiogenic shock (ICS)—the earliest possible reperfusion of the infarcted vessel by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—is already more than 10 years old (3).

One main cause of the high mortality among patients with ICS is the development of prolonged shock leading to multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (4). Consequently, ICS is not just a disease of the heart, but a disease of all the organs of the patient, who requires intensive care.

The current European (5) and American myocardial infarction guidelines focus their recommendations on “cardiological” treatment of the coronary arteries and the cardiovascular system; the “intensive care medicine” treatment of MODS is little regarded. This deficit motivated German and Austrian cardiologists, intensivists, cardiac surgeons, anesthetists, and rehabilitation specialists, together with their professional associations, to develop an S3 guideline for “infarction-related cardiogenic shock”, under the auspices of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften). The aim of this German-Austrian guideline, with its seven algorithms and 111 recommendations, is to provide an adequate picture of both the cardiological and the intensive care aspects of this syndrome, since the prognosis of patients with ICS depends not only on the impaired cardiac function, but, much more, on the resulting impairment of organ blood supply and microcirculation with consequent MODS.

The full version and the guideline report are available at www.leitlinien.net (in German).

Shortened print versions have so far appeared in the journals Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin, Intensiv- und Notfallbehandlung, and Kardiologe (6).

Methods

Concept and development of the guideline

The guideline was developed between 2004 and 2010 (see Leitlinienreport (guideline report) at www.leitlinien.net). First, 16 sessions were held on the various sections of the guideline with those listed in Box 1 from the medical societies as shown. Next, a multipart nominal group process—with Prof. I. Kopp (AWMF) in the chair—was carried out from 19 August 2008 to 25 September 2009, in which each medical society had one vote. The recommendations were agreed in consensus. Recommendations on which there was no consensus are inidicated accordingly and the different interpretations of the evidence laid out (Table 1). Before publication, the draft guideline was made available to other medical societies from October to December 2009 on the home page of the AWMF, the German Cardiac Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie – Herz- und Kreislaufforschung), and other medical societies for discussion (consultation phase). Comments were forwarded to the expert groups for their opinion and discussion as to whether any changes were needed (see Leitlinienreport at www.leitlinien.net). In the event no changes were made, but important comments were added as footnotes. All members agreed that there would be no patient participation (see Leitlinienreport at www.leitlinien.net).

Box 1. Medical societies and experts involved in guideline development.

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie – Herz und Kreislaufforschung (DGK) (German Cardiac Society) (lead society) (1)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internistische Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin (DGIIN) (German Society of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine) (2)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Thorax-, Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie (DGTHG) (German Society for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery) (3)

Österreichische Gesellschaft für Internistische und Allgemeine Intensivmedizin (ÖGIAIM) (Austrian Society of Internal and General Intensive Care Medicine) (4)

Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Intensivmedizin (DIVI) (German Interdisciplinary Association of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine) (5)

Österreichische Kardiologische Gesellschaft (ÖKG) (Austrian Society of Cardiology) (6)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesie und Intensivmedizin (DGAI) (German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine) (7)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Prävention und Rehabilitation (DGPR) (German Society of Preventive Medicine and Rehabilitation) (8)

-

Prof. Hans Anton Adams, Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Stabsstelle Interdisziplinäre Notfall- und Katastrophenmedizin (5*)

Prof. Christoph Bode, Universitätsklinikum Freiburg der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Medizinische Universitätsklinik, Abteilung Innere Medizin III – Kardiologie und Angiologie (1)

Prof. Josef Briegel, LMU Klinikum der Universität München, Klinik für Anaesthesiologie (7*)

Prof. Michael Buerke, Universitätsklinikum Halle (Saale) der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Innere Medizin III (1, 2*)

Dr. Arnd Christoph, Kliniken der Stadt Köln gGmbH, Krankenhaus Merheim, Medizinische Klinik II (1)

Prof. Georg Delle-Karth, Universitäts-Kliniken des Allgemeinen Krankenhauses Wien, Universitäts-Klinik für Innere Medizin II, Klinische Abteilung für Kardiologie (6*)

Prof. Lothar Engelmann, Universität Leipzig, Einheit für multidisziplinäre Intensivmedizin des Universitätsklinikums (2)

Prof. Raimund Erbel, Universitätsklinikum Essen, Westdeutsches Herzzentrum Essen, Klinik für Kardiologie (1)

Dr. Markus Ferrari, Universitätsklinikum Jena, Klinik für Innere Medizin I (1)

Prof. Hans-Reiner Figulla, Universitätsklinikum Jena, Klinik für Innere Medizin I (1)

Dr. Ivar Friedrich, Universitätsklinikum Halle (Saale) der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Herz- und Thoraxchirurgie (3)

Dr. J. T. Fuhrmann, Technische Universität Dresden, Medizinische Fakultät “Carl Gustav Carus,” Medizinische Klinik/Kardiologie (1)

Dr. Alexander Geppert, KH Wilhelminenspital Wien, 3. Medizinische Abteilung, Kardiovaskuläre Intensivmedizin (4*, 6)

Prof. Gunter Görge, Klinikum Saarbrücken, Medizinische Klinik II (1, 2)

Dr. Jürgen Graf, Universitätsklinikum Marburg, Klinik für Anästhesie und Intensivtherapie (2)

Prof. Gerhard Hindricks, Universität Leipzig, Herzzentrum Leipzig, Klinik für Innere Medizin/Kardiologie, Abteilung für Rhythmologie (1)

Prof. Uwe Janssens, St. Antonius Hospital Eschweiler, Klinik für Innere Medizin (1, 2)

Prof. Burkert Mathias Pieske, Medizinische Universität Graz, Universitätsklinik für Innere Medizin, Klinische Abteilung für Kardiologie (1, 6)

Dr. Roland Prondzinsky, Carl-von-Basedow-Klinikum Saalekreis GmbH, Bereich Merseburg, Klinik für Innere Medizin I (1)

Dr. Sebastian Reith, Universitätsklinikum Aachen, Medizinische Klinik I (1)

Dr. Martin Ruß, Universitätsklinikum Halle (Saale) der Martin- Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Innere Medizin III (1, 2) (secretary)

Dr. Dirk Schmitt, Universität Leipzig, Herzzentrum Leipzig, Klinik für Herzchirurgie (3)

Prof. Friedrich A Schöndube, Universitätsklinikum der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Klinik für Thorax-, Herz- und Gefäßchirurgie (3*)

Prof. Gerhard Schuler, Universität Leipzig, Herzzentrum Leipzig, Klinik für Innere Medizin/Kardiologie (1)

Prof. Bernhard Schwaab, Klinik Höhenried, Abteilung Kardiologie (8*)

Prof. Rolf-Edgar Silber, Universitätsklinikum Halle (Saale) der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Herz- und Thoraxchirurgie (3)

Prof. Ruth Strasser, Technische Universität Dresden, Medizinische Fakultät “Carl Gustav Carus,” Medizinische Klinik/Kardiologie (1)

Prof. Ulrich Tebbe, Klinikum Lippe-Detmold, Klinik für Kardiologie und Angiologie (1)

Prof. Hans-Joachim Trappe, Klinikum der Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Marienhospital Herne, Medizinische Klinik II (1, 2)

Prof. Karl Werdan, Universitätsklinikum Halle (Saale) der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Universitätsklinik und Poliklinik für Innere Medizin III (1*, 2) (coordination)

Prof. Uwe Zeymer, Klinikum der Stadt Ludwigshafen, Medizinische Klinik B (1)

Prof. Manfred Zehender, Universitätsklinikum Freiburg der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Medizinische Universitätsklinik, Abteilung Innere Medizin III – Kardiologie und Angiologie (1)

Prof. Hans-Reinhard Zerkowski, Genolier Swiss Medical Network, Genolier (VD), Schweiz (3)

Prof. Bernhard Zwißler, LMU Klinikum der Universität München, Klinik für Anaesthesiologie (7)

Numbers in parentheses identify affiliation with a medical society.

* Delegate of the relevant society with a vote in the nominal group process.

Addresses are those valid at the time the guideline was being developed.

Table 1. Recommendation grade and evidence levels.

| Recommendation grade | |

| ↑↑ | Strongly recommended: "shall" (usually based on studies with evidence level 1++ or 1+) |

| ↑ | Recommended: "should" (usually based on studies with evidence level 2++ or 2+) |

| ↔ | No recommendation: "may" (no confirmed study results exist that demonstrate either a beneficial or a harmful effect) |

| ↓ | Rejected: "should not" (negative recommendation) |

| ↓↓ | Strongly rejected: "shall not" (strong negative recommendation) |

| Evidence levels | |

| 1++ | High-quality systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or RCTs with a very low risk of bias |

| 1+ | Well performed systematic reviews of RCTs or RCTs with a low risk of bias |

| 2++ | High-quality systematic reviews of case-control or cohort studies with very low risk of confounders or bias and a high probability of causal relationships |

| 2+ | Well performed systematic reviews of case-control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounders or bias and a moderate risk of noncausal relationships |

| 3 | Nonanalytic studies |

| 4 | Consensus opinion of experts based on studies and clinical experience or in the interests of patients’ safety (e.g., monitoring) |

In accordance with the AWMF recommendation for recommendation grading, the recommendation and grading system of this S3 guideline follows the pattern of the National Care Guideline "Chronic CHD" (www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/themen/khk/nvl_khk), which follows the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network for the grading of evidence (www.sign.ac.uk/)

The guideline is valid until next revised or until January 2014 at the latest.

The S3 guideline “Infarktbedingter kardiogener Schock: Diagnose, Monitoring und Therapie” (Infarction-Related Cardiogenic Shock: Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Treatment) was developed under conditions of editorial independence; coordination and logistic support were financed by the German Cardiac Society. Travel costs were borne by the medical societies, and the expert work was done on a voluntary basis without the payment of any fees. All the members of the guideline development group have declared any conflicts of interest relating to the development of the S3 guideline; the list forms part of the guideline report at www.leitlinien.net/.H

The aims of the guideline and who the guideline is for

The aim of the S3 guideline “Infarktbedingter kardiogener Schock: Diagnose, Monitoring und Therapie” (Infarction-Related Cardiogenic Shock: Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Treatment) is to improve the quality of care of patients with ICS, by publishing evidence-based recommendations. It also presents the “state of the art” in diagnostics, monitoring, and treatment, thus representing a starting point for comparative studies. This is particularly to be emphasized, because many of the recommendations in this S3 guideline are based on expert opinions because of the lack of high-quality evidence.

The recommendations in the S3 guideline are directed at physicians managing patients with shock and acute myocardial infarction: that is, in particular, cardiologists and specialists in internal medicine, intensivists, heart surgeons, anesthetists, physicians working in interdisciplinary emergency admission services, emergency physicians, and rehabilitation specialists, along with the care staff working with them.

Data acquisition and evaluation of recommendations and evidence

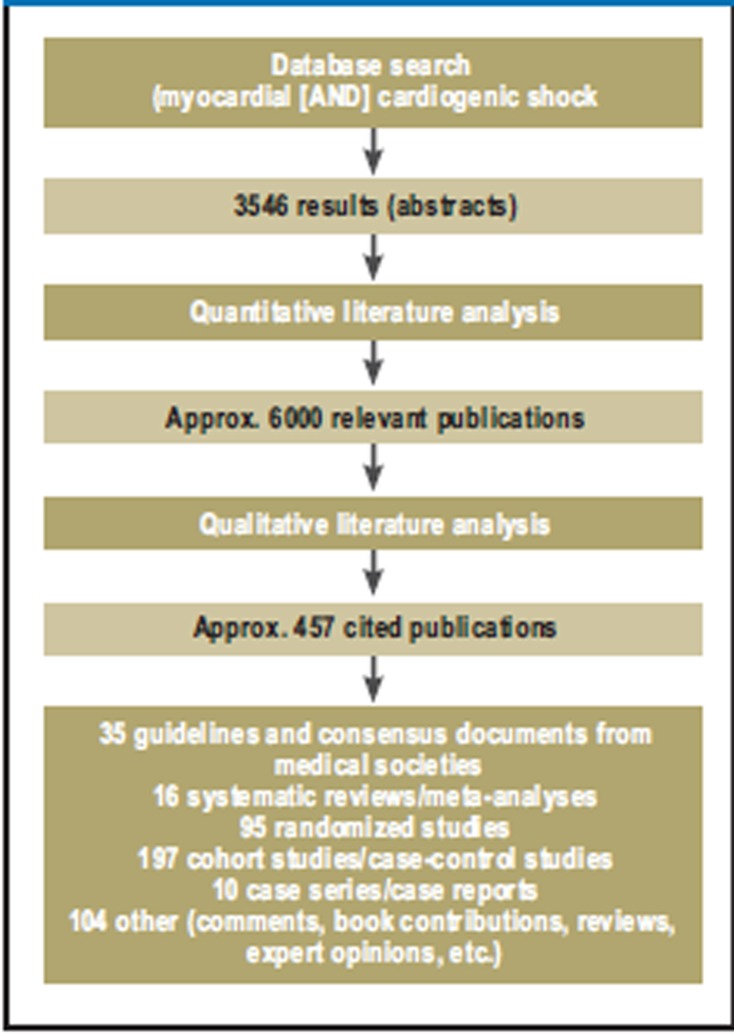

A systematic search was conducted of international guidelines in order to produce a statement of the thematic areas and questions on which there was consensus (“source guidelines”; see Leitlinienreport at www.leitlinien.net/). In addition, a primary systematic literature search was carried out (PubMed: search terms (abstracts) “myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock”) (Figure 3) of publications from 1 January 1990 to 30 September 2009 (3546 results). Evidence tables were produced for the themes “Revascularization” and “IABP implantation.”

Figure 3.

Literature search and selection of relevant publications

The evidence in the study data and the assigning of recommendation grades was done in the above-mentioned nominal group process in accordance with the recommendation grades and evidence levels listed in Table 1.

Results

The contents list of the guideline is reproduced in Box 2; a selection of the recommendations is given in eTable 1. Recommendations that particularly deserve discussion will be presented in more detail in the present article (Box 3).

Box 2. Contents of the German–Austrian S3 guideline “Infarction-related cardiogenic shock: diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment”.

Introduction

Method

Synopsis:

Diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of infarction-related cardiogenic shock

Definition, diagnosis, and monitoring

Earliest possible coronary revascularization

Cardiovascular support

Treatment of complications of infarction-related cardiogenic shock

Supportive therapy for multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS)

Nutrition and insulin therapy, red cell substitution and prophylaxis, considerations regarding limitation of treatment

Aftercare and rehabilitation

References

eTable 1. A selection of recommendations of the German-Austrian S3 guideline “Infarktbedingter kardiogener Schock: Diagnose, Monitoring und Therapie” (Infarction-Related Cardiogenic Shock: Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Treatment).

| Diagnosis and monitoring | |

| E1/2 ↑↑ | Act fast! Diagnosis and treatment should be carried out immediately and simultaneously. The diagnosis of infarction-related cardiogenic shock is based on clinical assessment (signs of underperfusion of organs) and on noninvasive hemodynamic measurements (e.g., after exclusion of hypovolemia: RRsyst <90 mm hg for at least 30 min) |

| E 32/33 ↑ | Cardiovascular management should be guided by hemodynamic perfusion pressure ranges (e.g., mean arterial pressure 65 to 75 mmHg and cardiac index >2.5 L × min-1 × m-2 or SVR 800 to 1000 dyn × s × cm-5 or SvO2/ScvO2 >65% or cardiac power (CP)/cardiac power index (CPI) >0.6 W/> 0.4 W × m-2) |

| Coronary revascularization as early as possible! | |

| E 13 ↑↑ | The infarct vessel should be revascularized as soon as possible, usually by means of PCI, in patients in the initial phase of shock within 2 hours from first contact with a physician, otherwise as early as possible |

| E 14 ↑ | Intracoronary stenting should be preferred |

| Inotropic drugs and vasopressors in patients with systolic pump failure | |

| E 34–E 38 | Dobutamine should be given as an inotropic drug (↑) and norepinephrine as a vasopressor (↑). In cases of catecholamine-refractory cardiogenic shock, levosimendan or phosphodiesterase-III ‧inhibitors should be used (↔), with levosimendan being preferred (↑) |

| Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) in patients with systolic pump failure | |

| E 44 ↑ | In patients undergoing fibrinolysis treatment, IABP should be carried out adjunctively |

| E 45 ↔ | In patients undergoing PCI, IABP may be considered, but the available evidence is unclear |

| Patients with infarction-related cardiogenic shock who have survived cardiac arrest | |

| E 78 ↑ | In resuscitated patients whose cardiac arrest was rapidly reversed by defibrillation, earliest possible PCI should be considered on a case by case basis, since this is expected to improve the prognosis. |

| E 79/80 ↑ | Mild hypothermia (32°C to 34°C) for 12 to 24 hours should be induced in comatose patients after cardiopulmonary resuscitation, both after resuscitation because of ventricular fibrillation (E 79) and because of asystole and also after cardiac arrest in hospital (E 80) |

| Pulmonary dysfunction: respiratory support, ventilation, analgosedation, and weaning | |

| E 84 ↑ | Patients with backward failure should be invasively ventilated |

| E 86 ↑ | Invasive ventilation should be preferred to noninvasive ventilation |

| E 88 ↑ | If ventilation is still indicated after hemodynamic stabilization, lung-protective ventilation should be given (VT ≤ 6 mL × kg-1; peak pressure le; 30 mbar) |

| E 93 ↑ | Analgosedation should be consistently measured and recorded using a sedation scale |

| E 94 ↑ | Weaning should always follow a standardized established weaning protocol |

| Supportive treatment of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and general intensive care measures including prophylaxis | |

| E 99 ↑ | Blood glucose levels should be kept <150 mg × dl-1/< 8.3 mmol × l-1 by means of insulin |

| E 100 ↓↓ | Glucose-insulin-potassium infusions should not be given |

| E 101 ↑ | Red cell concentrate transfusions should be given when hemoglobin values are <7.0 g × dl-1 /4.3 mmol × l-1 or hematocrit <25% and the values be brought up to 7.0 to 9.0 g × dl-1/4.3 to 5.6 mmol × l-1 or ≥25%. |

↑ / ↓↓ strongly recommended (“shall/shall not”); ↑ recommended (“should”); ↔ no evidence-based recommendation possible. The numbering refers to the print version of the guideline (6)

Box 3. What is new in comparison to the established guidelines?

Pressure monitoring is not enough for hemodynamic treatment after revascularisation! Additional cardiac output monitoring is mandatory.

Dobutamine is the inotropic agent of choice; norepinephrine is the vasopressor of choice; levosimendan can be used in addition in patients with catecholamine-refractory shock.

Even in resuscitated patients, earliest possible PCI should be considered on a case by case basis.

Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (IABP) has been “down-graded.”

If ventilation is needed, it should be invasive and lung-protective.

Diagnosis and monitoring: initial phase

A preliminary diagnosis of “infarction-related cardiogenic shock” (ICS) (E 1/2 in eTable 1) usually has to be made quickly by the emergency physician during the prehospital phase on the basis of the 12-lead ECG (“STEMI,” ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction) and clinical findings (“cardiogenic shock”) (recommendation ↑↑). Even in the rare case of ICS following NSTEMI (no ST elevation on the ECG), the physician can diagnose ICS on the basis of clinical criteria in a patient with ACS.

The most important—though not ubiquitous—symptom of ICS is hypotension <90 mm Hg systolic for at least 30 minutes, associated with signs of reduced organ perfusion. Invasive measurement of cardiac output (e.g., cardiac index < 2.2 L × min-1 × m-2 and PAOP > 15 mm Hg) (3) is not necessary for a diagnosis of ICS. However, one patient in four with ICS presents without initial hypotension; in such cases, the diagnosis must rest on clinical signs of reduced organ perfusion (cold extremities, oliguria, altered mental status, e.g., agitation).

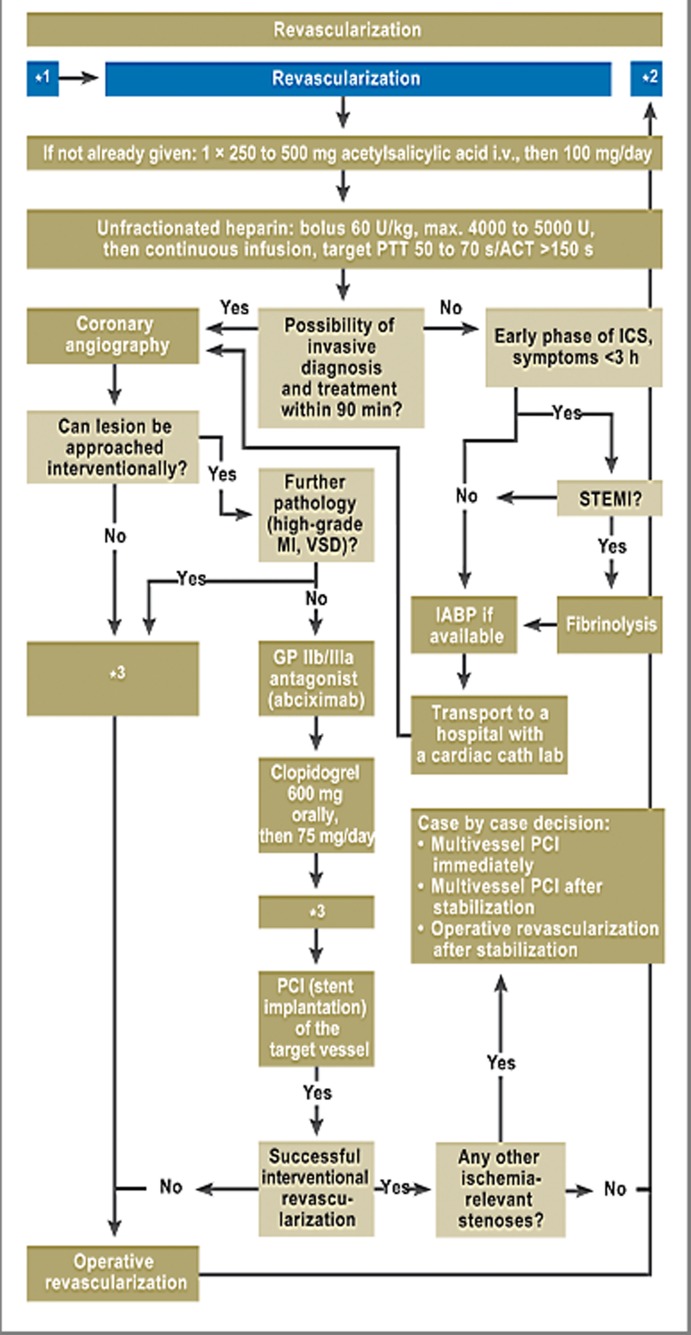

Revascularization

Revascularization of the infarcted coronary artery (Figure 1) is performed as early as possible, usually by PCI (↑↑, E13 in eTable 1). Initial cardiovascular and respiratory stabilization of the PCS patient—dobutamine/norepinephrine, ventilation for those with respiratory failure, adequate volume replacement for those with right ventricular infarction—is necessary so that the coronary intervention may be carried out safely and efficiently.

Figure 1.

Revascularization is the most important element of treatment of ICS.

*1 After initial stabilization/before cardiac catheter investigation;

*2 Persistent shock after revascularization;

*3 Currently there is not enough evidence for the use of IABP in PCI or ACB; in patients who have received fibrinolytic treatment, the IABP should be used

The superiority of the principle of earliest possible coronary revascularization has been evident since the SHOCK trial (3, 7). Early reperfusion of the coronary arteries is an important predictor of long-term survival (2) (eTable 2); when this is achieved, 132 lives can be saved for every 1000 shock patients treated (7).

eTable 2. Results of the SHOCK study: 30-day to 6-year survival rates of the two groups.

| Early revascularization | Conservative medical treatment | ||

| Primary endpoint | |||

| Survival: 30 days | 56.0% | 47.6% | p = 0.11 |

| Secondary endpoints | |||

| Survival: 6 months | 49.7% | 36.9% | p = 0.027 |

| Survival: 12 months | 46.7% | 33.6% | p < 0.04 |

| Survival: 6 years | 32.8% | 19.6% | p = 0.03 |

PCI on the coronary infarct artery usually takes the form of stent implantation (↑, E 14 in eTable 1) with intensive use of platelet aggregation inhibitors. If interventional revascularization is unsuccessful, surgery should be carried out as rapidly as possible. If several significant coronary stenoses are present, decisions may in some cases have to be made about further interventional or surgical revascularization.

Resuscitated patients form a special subgroup, which may make up as much as 30% of all patients with ICS (8, 9). Early PCI should be considered in rapidly defibrillated patients (↑, E 78 in eTable 1) and mild hypothermia (32° to 34°C) induced for 12 to 24 hours (↑, E 79/80 in eTable 1).

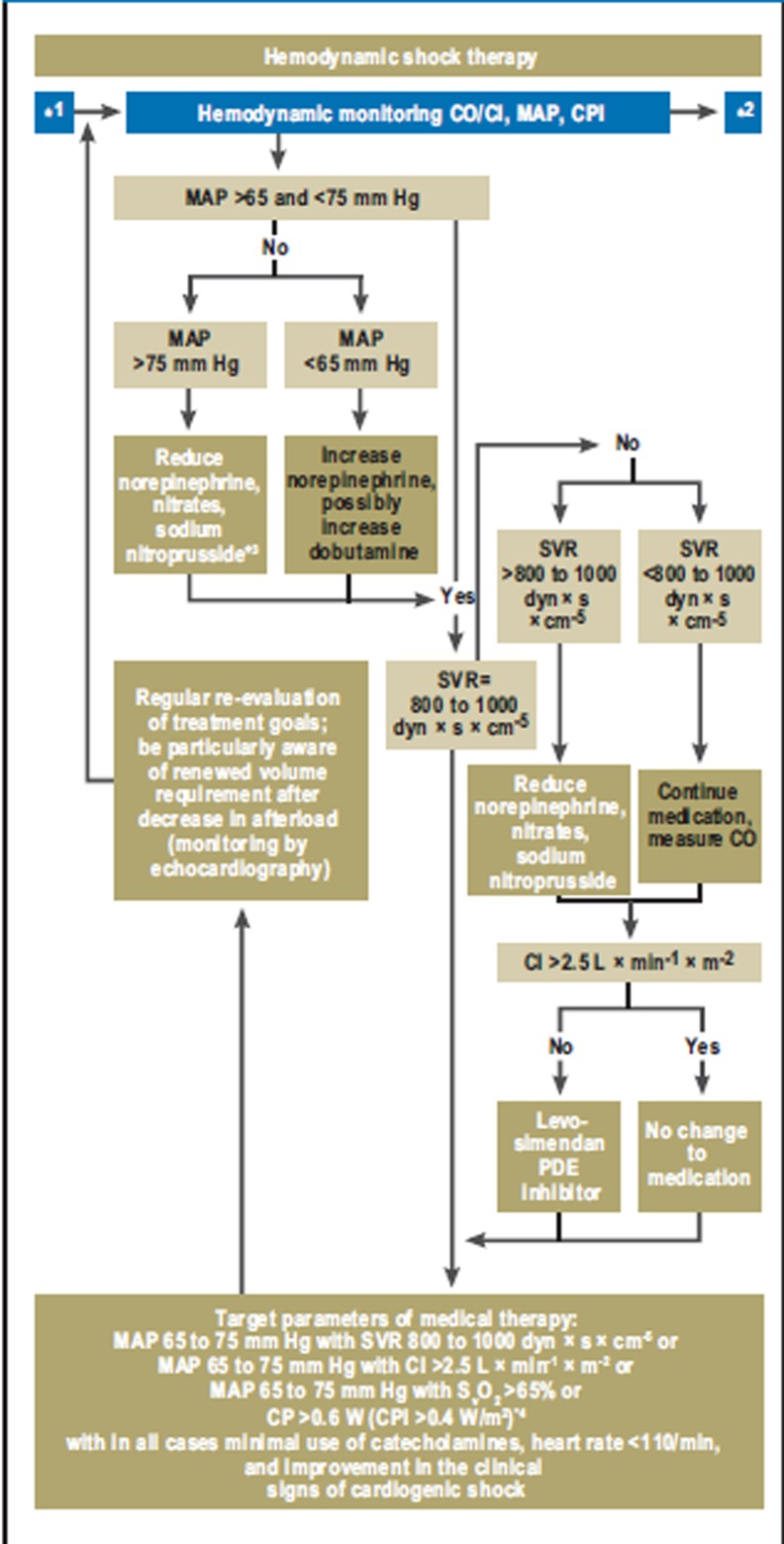

Persistent shock after revascularization

The goals of hemodynamic management if shock symptoms persist are blood pressure stabilization and ensuring adequate organ perfusion (↑, E 32/33 in eTable 1; Figure 2). To achieve this goal with adequate preloading and the least possible use of catecholamines, close invasive monitoring including repetitive invasive measurement of cardiac output (↑↑, E 12) is necessary (Figure 2). As to perfusion pressure, a mean arterial pressure between 65 and 75 mm Hg and cardiac index (cardiac output related to body surface area) of >2.5 L × min-1 × m-2 should be aimed at; as blood flow equivalents, a SVR of 800 to 1000 dyn × s × cm-5, a SvO2 >65%, or the cardiac power (product of cardiac output and mean arterial pressure as a measure of overall cardiac hydraulic performance) or cardiac power index (CP > 0.6 W or CPI > 0.4 W × m-2) (10– 13) may be chosen instead of cardiac index (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hemodynamic shock therapy: Hemodynamic shock therapy focuses on achieving adequate organ perfusion using the minimum of catecholamines.

*1 Shock after revascularization;

*2 Treatment of MODS;

*3 In patients with raised SVR, norepinephrine treatment is always ended before treatment with nitrates or sodium nitroprusside is started. ÖKG and ÖGIAIM (see Box 1) prefer treatment with nitroglycerine rather than sodium nitroprusside in patients with raised SVR, even though catecholamine treatment has been stopped.

*4 CP > 0.6 W corresponds to a cardiac output of 5 L/min with an MAP of 65 mm Hg and SVR of 880 dyn × s × cm-5

Which vasopressor and which inotrope?

Norepinephrine is the vasopressor of choice in patients with MAP values below 65 mm Hg (↑, Figure 2; E 34 to E 38 in eTable 1). The MAP can usually be effectively raised by intravenous infusion of 0.1 to 1 µg × kg-1 × min-1. In the SOAP II study of 1679 patients with shock of various etiologies (14), norepinephrine showed a tendency to lower mortality than dopamine (28-day mortality 45.9% vs. 50.2%; odds ratio [OR] 1.19; confidence interval [CI] 0.98 to 1.44; p = 0.07) and significantly fewer arrhythmias (12.4% vs. 24.1%), especially atrial fibrillation. In the prospectively defined subgroup of patients with cardiogenic shock, the norepinephrine treatment led to a significantly better survival rate than the dopamine treatment (OR 0.75; p = 0.03; [14]).

Dobutamine is the inotrope of choice (↑, Figure 2; E 34 to E 38 in eTable 1). In the dose range of 2.5 to 10 µg × kg-1 × min-1 there is a dose–effect relationship. In a multicenter cohort observation study of 1058 shock patients treated with catecholamines (15), application of dopamine was an independent risk factor for mortality, while application of dobutamine or norpinephrine was not.

In ICS refractory to catecholamine treatment, current research results support the additional use of levosimendan (loading dose 12 to 24 µg × kg-1 over 10 minutes, followed by 0.05 to 0.2 µg × kg-1 × min-1) more than that of phosphodiesterase III inhibitors such as enoximone or milrinone (↑, Figure 2; E 34 to E 38 in eTable 1) (16). Patients with coronary heart disease with decompensated heart failure who have previously been treated with beta-blockers will have more hemodynamic benefit from a phosphodiesterase III inhibitor than from dobutamine (17).

Skepticism about intraortic balloon counterpulsation

Both the European and the American myocardial infarction guidelines regard the use of IABP as a class I recommendation. The favorable hemodynamic effect of IABP is ascribed to an increase in diastolic coronary perfusion with a simultaneous decrease in the afterload. In ICS patients, however, the hemodynamic effects of IABP are moderate (18): Although IABP can relieve the left ventricle—as is seen by lower BNP concentrations—the cardiac index is not significantly improved in the first few days after the onset of shock. Even more importantly, neither MODS (measured as the APACHE II score), which determines the prognosis, nor the systemic inflammation (measured as the serum IL-6 concentration) is improved by the IABP treatment (18).

These sobering results of the randomized controlled IABP SHOCK trial (18) are confirmed by the negative results of a Cochrane analysis of six randomized studies of a total of 190 ICS patients (19) and a meta-analysis of 10 529 ICS patients from nine cohort studies (20). The ICS patients treated with PCI (the recommended standard therapy) derived no benefit from adjunctive IABP treatment; rather, they even showed an absolute increase in mortality of 6% (ARR +6%; RRR +15%) (20); only when used together with systemic fibrinolysis did adjunctive IABP lead to an 18% reduction in mortality (ARR –18%; RRR –26%) (20). It is to be hoped that the currently ongoing prospective multicenter IABP SHOCK II study (26) will elucidate whether the adjunctive use of IABP in PCI-treated ICS patients can reduce mortality. Even weaker is a “may” recommendation in selected cases for the use of mechanical cardiac support systems, which, principally in animal experiments, have proved able to improve hemodynamics, reduce wall tension, and improve coronary flow reserve. However, large clinical user studies are currently under way and are expected to produce greater clarity on this point in the near future (21).

For this reason, the German–Austrian S3 guideline gives (E 44 to E 47 in eTable 1) only a weak recommendation (↑, E 44) for the use of IABP in ICS patients treated with systemic fibrinolysis, and only “may” information for patients treated with PCI (↔ E 45).

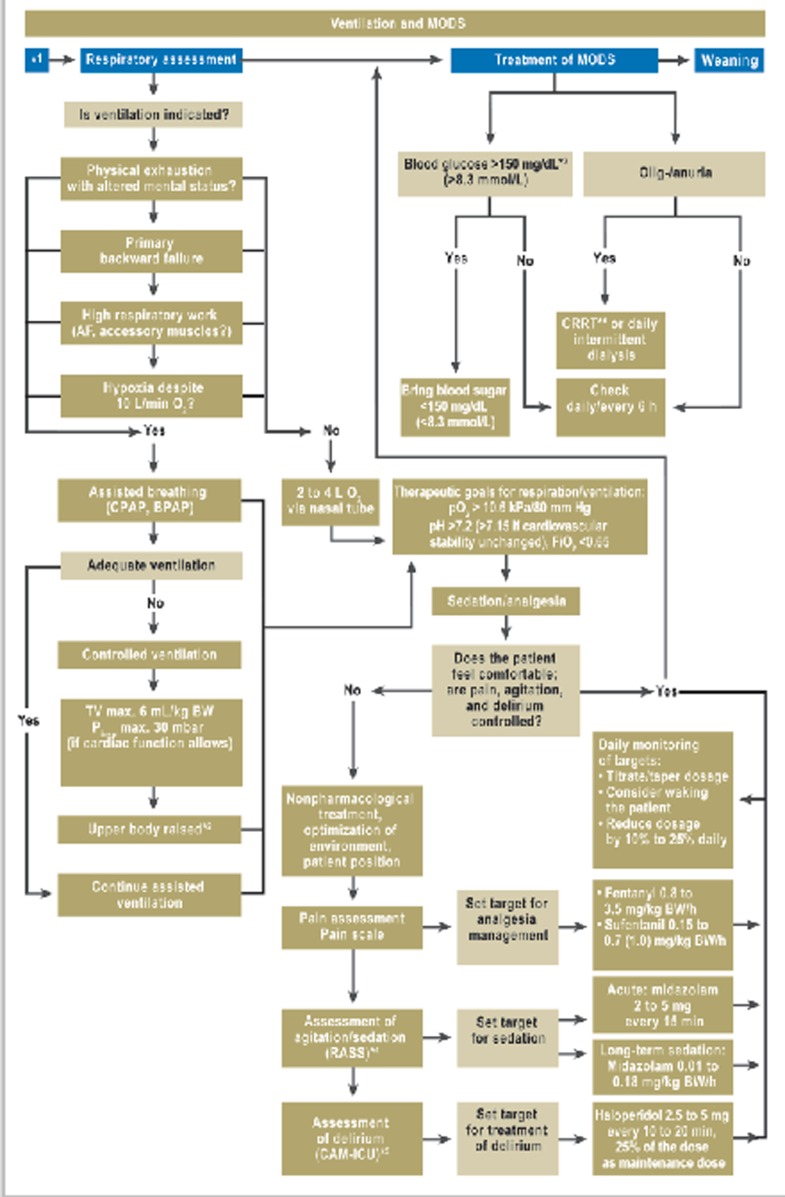

Ventilation

Mechanical ventilation of an ICS patient ensures oxygenation and relieves the heart of the work of breathing. In contrast to the recommendation for noninvasive ventilation in patients with decompensated heart failure, in patients with ICS invasive ventilation should be preferred (↑, eFigure; E 86 in eTable 1). The reasons for this are the constant, stable ventilation conditions provided by invasive ventilation and the avoidance of psychomotor excitement that would exhaust the patient. Although hemodynamic stability is the main focus initially, the advantages of lung-protective ventilation should be made use of at the earliest possible moment (↑, E 88 in eTable 1), although the available data in this regard, especially in ICS patients, are very sparse (22). The depth of analgesia/sedation should be recorded three times a day using the Richmond Agitation–Sedation scale (↑, E 93 in eTable 1). Weaning, which is often difficult in ICS patients, should follow a weaning protocol (↑, E 94 in eTable 1), and before weaning starts, the following conditions should be fulfilled: hemodynamic stability, absence of myocardial ischemia, and absence or regression of inflammation or infection.

eFigure.

Ventilation and treatment of MODS:

*1 Hemodynamic shock treatment;

*2 In the sepsis guidelines, it is recommended to position the upper body at an angle of 45°

*3 ÖGIAIM (see Box 1) recommends a blood glucose range of 80 to 120 mg/dL (4.4 to 6.7 mmol/L);

*4 RASS: Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale;

*5 CAM-ICU (Confusion Assessment Method for Intensive Care Units): test to evaluate delirium in the intensive care unit;

*6 CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy

Intensive care

The initially favorable results of continuous intravenous insulin therapy with the aim of achieving normoglycemia in intensive care patients were not confirmed in later studies such as the NICE-SUGAR study (23). In view of these results and of the fact that high blood glucose levels are unfavorable prognostic indicators in heart attack patients (24), a “middle way” is recommended in ICS patients, aiming to keep blood glucose values below 150 mg × dL-1/< 8.3 mmol × L-1 (↑, eFigure; E 99 in eTable1 ).

The use of insulin–glucose–potassium infusions, for which there have been convincing experimental results, has not proved effective in clinical studies of patients after myocardial infarction (24) and should therefore not be used in ICS patients either (↓↓, E 100 in eTable 1).

At what Hb threshold value should intensive care patients receive red cell concentrates? There is controversy about this, especially in regard to intensive care patients with cardiac disease and older patients in whom increased oxygen requirement of the underperfused heart may be assumed. Given the available data, in ICS patients red cell concentrates should be given from a Hb value < 7.0 g × dL-1/<4.3 mmol × L-1 or hematocrit < 25%. Target values are Hb 7.0 to 9.0 g × dL-1/4.3 to 5.6 mmol × L-1 or hematocrit 25% (↑, E 101), or, in older patients (>75 years), 30% (↑, E 101 in eTable 1).

Mandatory measures in ICS patients are thrombosis prophylaxis—by means of intravenous administration of heparin—and stress ulcer prophylaxis.

Recommendations for aftercare/rehabilitation

Once the ICS patient has survived the shock, particular attention must be paid to risk stratification in the post-intensive-care phase. The current rehabilitation guidelines list both acute STEMI/NSTEMI and decompensated heart failure as class I/A indications for cardiological rehabilitation. In patients with ICS, inpatient rehabilitation lasting usually about 3 to 4 weeks should be aimed at if possible, because of the severity of the infarction event.

Discussion

The most effective treatment measure for reducing mortality among ICS patients is revascularization of the infarct vessel as early as possible (eTable 2). Despite successful revascularization, almost one in two ICS patients still dies. This is due to the sequelae of protracted shock: the severe systemic inflammatory reaction (SIRS) and the multiorgan dysfunction syndrome (MODS) (18). Consequently, any further progress can only be achieved through effective anti-SIRS (25), anti-MODS, and general intensive care medical treatment, which hitherto have not received enough attention in ICS. Above all, comparison with the available evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock shows the deficits in, for example, lung-protective ventilation and weaning, and in the standardized early hemodynamic stabilization. These aspects emphasize intensive care medicine approaches to the treatment of ICS, rather than cardiological approaches, and the present German-Austrian guideline takes more account of them than do the European and American myocardial infarction guidelines.

Weaknesses and limitations of the guideline

High-quality randomized controlled studies and meta-analyses relating to the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of ICS are available only for a few aspects, so that the guideline recommendations very often have to rely on expert opinions. So far, recommendations about nursing have been entirely omitted, both in terms of the catheter lab and the intensive care unit, since the work begun on the nursing aspects has not yet been brought to the desired conclusion. It is to be hoped that this guideline, which shows how little evidence there is on some points, will encourage the carrying out of high-quality studies.

Glossary.

ACB aorto-coronary bypass

ACS acute coronary syndrome

ARR absolute risk reduction

AWMF Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany)

BNP B-type natriuretic peptide

CI cardiac index

CO cardiac output

CP/CPI cardiac power/cardiac power index

DGK Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kardiologie – Herz- und Kreislaufforschung (German Cardiac Society)

GP IIb/IIIa, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa

IABP intra-aortic balloon pump

ICS infraction-related cardiogenic shock

IL interleukin

MAP mean arterial pressure

MR mitral regurgitation

MODS multiorgan dysfunction syndrome

NIV noninvasive ventilation

NSTEMI non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

PAOP pulmonary artery occlusion pressure

PCI percutaneous coronary intervention

RRR relative risk reduktion

STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

SvO2 venous oxygen saturation

SVR systemic vascular resistance

VT tidal volume

VSD ventricular septal defect

Weaning gradual reduction of ventilatory support and intensive medical care

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

The authors thank all participants, all the medical societies involved, and the AWMF (Box 1), who have contributed to the development of this guideline.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

K. Werdan has received lecture fees from Baxter, Datascope, Maquet, and Orion, has held a position on the Advisory Boards of Baxter and Datascope, and has received research funding from Datascope.

G. Delle-Karth has received consultancy fees from Orion, Abbott, Bayer AG, and St Jude Medical and lecture fees from Orion, Abbott, Biotronik, Daiichi Sankyo, and Eli Lilly. He has received reimbursement of travel or conference costs from Medtronic, Biosensors, Abbott, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, and Orion. He has received funding for research projects from Medtronic, Abbott, Boston Scientific, Braun, Siemens, GE Healthcare, and Biosensors.

A. Geppert has received reimbursement of travel and event costs from Medtronic, Abbott, and Orion Pharma, and has received lecture fees from Orion Pharma and Medtronic.

M. Ruß and F.A. Schöndube declare that no conflict of interest exists.

M. Buerke has received lecture fees from Orion Pharma, Datascope, and Abbott.

References

- 1.Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1112570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, et al. Early revascularization and long-term survival in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2006;295:2511–2515. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock SHOCK Investigators. Should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock? N Engl J Med. 1999;341:625–634. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kohsaka S, Menon V, Lowe AM, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome after acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1643–1650. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van de Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force on the Management of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werdan K, Ruß M, Buerke M, et al. Deutsch-österreichische S3-Leitlinie Infarktbedingter kardiogener Schock. Diagnose, Monitoring und Therapie. Der Kardiologe 2011 5 166-224; Intensivmed 2011; 48: 291-344. Intensiv- und Notfallbehandlung. 2011;36:49–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, White HD, et al. One-year survival following early revascularization for cardiogenic shock. Jama. 2001;285:190–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arntz HR, Bossaert LL, Danchin N, Nikolaou NI. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 5 Initial management of acute coronary syndromes. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1353–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolan JP, Soar J. Postresuscitation care: entering a new era. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:216–222. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283383dca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter G, Moshkovitz Y, Kaluski E, et al. The role of cardiac power and systemic vascular resistance in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of patients with acute congestive heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2003;5:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(03)00100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fincke R, Hochman JS, Lowe AM, et al. Cardiac power is the strongest hemodynamic correlate of mortality in cardiogenic shock: A report from the SHOCK trial registry. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;44:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendoza DD, Cooper HA, Panza JA. Cardiac power output predicts mortality across a broad spectrum of patients with acute cardiac disease. Am Heart J. 2007;153:366–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russ MA, Prondzinsky R, Carter JM, et al. Right ventricular function in myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: Improvement with levosimendan. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:3017–3023. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b0314a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, et al. Comparison of Dopamine and Norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:779–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakr Y, Reinhart K, Vincent JL, et al. Does dopamine administration in shock influence outcome? Results of the Sepsis Occurrence in Acutely Ill Patients (SOAP) Study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:589–597. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201896.45809.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuhrmann JT, Schmeisser A, Schulze MR, et al. Levosimendan is superior to enoximone in refractory cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2257–2266. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181809846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metra M, Nodari S, D’Aloia A, et al. Beta-blocker therapy influences the hemodynamic response to inotropic agents in patients with heart failure: A randomized comparison of dobutamine and enoximone before and after chronic treatment with metoprolol or carvedilol. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;40:1248–1258. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prondzinsky R, Lemm H, Swyter M, et al. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: the prospective, randomized IABP SHOCK Trial for attenuation of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:152–160. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b78671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unverzagt S, Machemer MT, Solms A, et al. Intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation (IABP) for myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007398.pub2. CD007398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjauw KD, Engstrom AE, Vis MM, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intra-aortic balloon pump therapy in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: should we change the guidelines? Eur Heart J. 2009;30:459–468. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cyrus T, Mathews SJ, Lasala JM. Use of mechanical assist during high-risk PCI and STEMI with cardiogenic shock. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75(Suppl 1):1–6. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouraki K, Schneider S, Uebis R, et al. Characteristics and clinical outcome of 458 patients with acute myocardial infarction requiring mechanical ventilation. Results of the BEAT registry of the ALKK-study group. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100:235–239. doi: 10.1007/s00392-010-0235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cobb LA, Killip T, Lambrew CT, et al. Glucose-insulin-potassium infusion and mortality in the CREATE-ECLA trial. Jama. 2005;293:2596–2597. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2597-a. 2597; Letters and authors’ reply: 2005; 293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The Triumph-Investigators. Effect of tilarginine acetate in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock: the TRIUMPH randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2007;297:1657–1666. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.15.joc70035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiele H, Schuler G, Neumann FJ, et al. on behalf of the IABP-Shock II Trial Investigators: Intraaortic balloon counterpulsation in myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: Design and rational of the intraaortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock II trial (IABP-SHOCK II) Am Heart J. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.012. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]