Abstract

We present a patient with lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (lelc) of the breast whose diagnosis is illustrative of the pathology nuances that must be taken into account to successfully reach correct identification of the disease. We also present an overview of our patient’s proposed treatment in the context of 16 other reported lelc cases. Although lelc cases are rare, a sufficient number have been reported to discern the natural history of this pathologic entity and to undertake a review of those cases and of the application of oncologic first principles in their management. Given the potential for locoregional spread and distant metastases in lelc, adjuvant therapy has a role in the treatment of this entity.

KEY WORDS: Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma, breast, radiotherapy

1. INTRODUCTION

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (lelc) is an undifferentiated carcinoma composed of malignant epithelial cells with an associated background of lymphocytes. Lymphoepithelioma was first described by Schminke 1 and Regaud and Reverchen 2 in 1921, but not until 1994 was a case of lelc in the breast reported 3. Schminke and Regaud and Reverchen each described patterns of growth of the malignant epithelial cells characteristic of this pathologic entity. The cells may be arranged singly (Schminke’s pattern) or in syncytial masses, nests, or cords (Regaud’s pattern). Since Kumar and Kumar’s first reported case in the breast 3, another 15 cases of breast lelc have appeared in the English medical literature 4–12.

Here, we present a patient with lelc of the breast whose diagnosis is illustrative of the pathologic nuances that must be taken into account to successfully reach correct identification of the disease. We also present an overview of our patient’s proposed treatment in the context of the 16 other reported lelc cases.

2. CASE PRESENTATION

A 55-year-old postmenopausal woman originally from Ghana presented with a 4-week history of left breast tenderness and an upper outer quadrant mobile breast mass. She had been mammographically screened, with the most recent mammogram (performed 1 year before her presentation) having demonstrated no abnormalities. Her past medical history was unremarkable, with a surgical history of Cesarean section, tubal ligation, and hernia repair. She was gravida 2, para 2, with menopause having occurred at age 53. On systems review, she denied fevers, chills, or night sweats. No weight loss was reported, and she was asymptomatic but for left breast tenderness.

Physical examination revealed no cervical or axillary adenopathy, but was significant for a diffusely swollen left breast with a discrete, mobile 4-cm mass. The exam was otherwise noncontributory.

Mammography revealed a 3- to 4-cm upper outer quadrant density with spot compression views showing lobulated margins. No evidence of calcifications was noted. Breast ultrasonography showed a 4.3×3.5×2.6-cm lobulated, poorly marginated, hypoechoic solid mass. Computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of distant metastases and the presence of an 8-cm left breast mass with a uniform low-density component (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Axial slice from computed tomography study of the thorax demonstrating a left breast mass.

Fine-needle aspirate yielded a cellular specimen noteworthy for single and groups of abnormal elongated cells with visible nucleoli presenting together with lymphocytes and plasma cells. A bone marrow biopsy revealed normocellular marrow with no evidence of lymphoproliferative disorder.

An excisional biopsy was followed by 3 successive pathology reviews. The initial consultant described a 6.5-cm mass, well circumscribed in relationship to the adjacent breast parenchyma, of lymphoid infiltrate with irregular germinal-like centres, favouring a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Given that lymphoma of the breast is a rare clinical entity, a second opinion was sought. The second consultant described a malignant epithelial lesion confirmed by staining for cytokeratins AE1, AE3, and Cam 5.2. The background lymphoplasmacytic population was thought to be reactive, with a diagnosis of medullary carcinoma favored. The need for confirmation of this diagnosis by a breast pathologist resulted in the third and final pathology review.

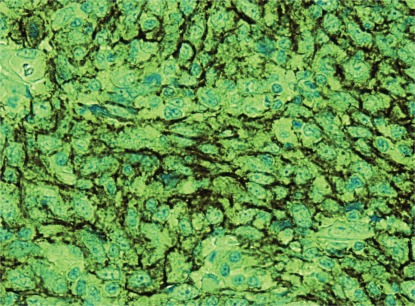

The third review, by an expert breast pathologist, described dense nodular aggregates of lymphocytes and plasma cells interspersed with and surrounded by fat and hyalinized stroma on microscopic examination. Germinal centers were observed in some aggregates. Microscopy showed sheets of large, loosely cohesive, and highly atypical cells (Figure 2). The cells had pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and moderately pleomorphic nuclei, with inconspicuous nucleoli, in a background of dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. The lymphoplasmacytic infiltration overshadowed the epithelioid cells in some areas. There was no in situ ductal or lobular carcinoma identified in the specimen. These histologic features led to the suspicion that this entity was a large B-cell lymphoma.

FIGURE 2.

Tissue section of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast (hematoxylin and eosin stain).

1.1. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical studies used the avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex method and monoclonal antibodies against low molecular weight cytokeratin, cytokeratin 5/6, cytokeratin 7, estrogen and progesterone receptors, c-Erb-2 (her2), epidermal growth factor (her1), CD117 (c-Kit), B-cell marker CD20, and T-cell marker CD3. The stains for lymphoid markers such as CD20 and CD3 were positive in the lymphoid infiltrate. No skewing in the kappa and lambda light chains ratio was observed, indicating a non-clonal lymphocytic infiltrate. The large epithelioid cells in the center of the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate were strongly positive for cytokeratin 7, with weak positive staining for low molecular weight cytokeratin and high molecular weight cytokeratins 5 and 6. Tumour cells were negative for both the estrogen and progesterone receptors, her2, and her1. Diffuse and strong positivity for CD117 was observed (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Immunohistochemical staining for CD117 (c-Kit) demonstrates strong positivity.

1.2. In-Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization with an ISH iView Blue Detection Kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, U.S.A.) to detect Epstein–Barr virus (ebv) in tumour epithelial cells and polymerase chain reaction to detect human papilloma virus both yielded negative results.

The differential diagnosis included medullary carcinoma, ductal or lobular carcinoma with lymphoid stroma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and lelc. Distinguishing the latter tumour from medullary breast carcinoma depends on circumscription and the syncytial growth pattern present in medullary carcinoma. In our case, the tumour demonstrated multinodular lesions without circumscription. Furthermore, in contrast to the features of medullary carcinoma, the margins of the tumour clusters were heavily permeated by numerous lymphocytes, resulting in poor margin definition. However, both tumour types share some features, such as an absence of ebv and negative results for hormone receptors. Although breast carcinomas can be associated with dense infiltration by lymphocytes, obscuring of the neoplastic cells in the lymphocytic background is unusual, in contrast to lelc.

Primary or secondary lymphoproliferative neoplasms of the breast should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. An lelc shows diffuse proliferation of lymphocytes and can mimic non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as in our case. Immunostaining for epithelial markers such epithelial membrane antigen or cytokeratin is very helpful, because the neoplastic epithelial cells within the intense lymphocytic infiltration will be highlighted. Based upon those features, a diagnosis of lelc of the breast was made.

Before management proceeded further, a review of the English medical literature was undertaken.

2. DISCUSSION

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas are tumours arising outside of the nasopharynx with characteristics similar to those of nasopharyngeal lymphoepithelioma. These tumours have been reported in many organs, and 16 cases of lelc of the breast have previously been published. Tables i and ii summarize the published cases. As with all of the published cases, our patient showed no evidence of ebv.

TABLE I.

Characteristics and treatment of reported cases of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (lelc) of the breast

| Reference | Age (years) | Side (L/R) | Size (cm) | Lymph node status | Surgery | Systemic therapy | Radiotherapy | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kumar and Kumar, 19943 | 65 | R | 2 | 0 | Mastectomy, alnd | No evidence of disease at 7 months | ||

| Cristina et al., 20004 | 54 | R | 1.5 | 0/19 | Wide local excision, alnd | Yes | No evidence of disease at 6 months | |

| Dadmanesh et al., 20015 | 43 | L | 1.9 | 1/1 | Quadrantectomy, alnd | No evidence of disease at 60 months | ||

| 53 | R | 2 | No evidence of disease at 72 months | |||||

| 49 | L | 1 | 0/19 | Quadrantectomy, alnd | Contralateral lelc 3 years later | |||

| 52 | R | 2.7 | 0/20 | No evidence of disease at 36 months | ||||

| 64 | R | 2 | 0/29 | Mastectomy, alnd | No evidence of disease at 60 months | |||

| 69 | R | 2.3 | 0/19 | Yes | No evidence of disease at 48 months | |||

| Naidoo et al., 20019 | 50 | R | 2.5 | 2/24 | Wide local excision, alnd | No evidence of disease at 3 months | ||

| Peştereli et al., 200210 | 56 | R | 2 | 2/27 | Mastectomy, alnd | Chemotherapy | No evidence of disease at 12 months | |

| Ilvan et al., 20046 | 59 | R | 3.5 | 0/20 | Wide local excision, alnd | Tamoxifen | Yes, 50.4 Gy | No evidence of disease at 53 months |

| 67 | R | 1.1 | 0/16 | Quadrantectomy | Yes, 50.4 Gy | No evidence of disease at 46 months | ||

| Sanati et al., 200412 | 62 | L | 3.0 | Wide local excision | ||||

| Kurose et al., 20058 | 47 | L | 2.8 | 0/33 | Mastectomy, alnd | Tamoxifen | At 4 months, biopsy-positive parasternal mass; cef and 40 Gy rt;at 19 months, parasternal mass and lung metastasis | |

| Saleh et al., 200511 | 51 | L | 1.3 | 1/8 | Wide local excision, alnd | |||

| Kulka et al., 20087 | 42 | R | 2.5 | 0/10 | Wide local excision ×2 |

L/R = left or right; alnd = axillary lymph node dissection; cef = cyclophosphamide–epirubicin–5-fluorouracil; rt = radiotherapy.

TABLE II.

Summary of the in-situ lobular component and receptor status

| Reference | In situ lobular component |

Receptor status |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen | Progesterone | her2 | ||

| Kumar and Kumar, 19943 | Positive, infiltrative | Positive | Positive | nd |

| Cristina et al., 20004 | Positive, infiltrative | Positive (42%) | Negative (<10%) | Negative |

| Dadmanesh et al., 20015 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | |

| Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | |

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | |

| Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | |

| Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | |

| Naidoo et al., 20019 | Negative | nd | nd | nd |

| Peştereli et al., 200210 | Positive, infiltrative | Positive (80%) | Positive (20%) | Negative |

| Ilvan et al., 20046 | Negative | Positive | Positive | nd |

| Negative | Weak positive | Weakly positive | nd | |

| Sanati et al., 200412 | Atypical lobular hyperplasia | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Kurose et al., 20058 | Negative | Negative | Negative | nd |

| Saleh et al., 200511 | Negative | Positive | Negative | nd |

| Kulka et al., 20087 | Negative | Weak positive | nd | Negative |

nd = not determined.

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas arising outside of the nasopharynx have morphologic features identical to those of nasopharyngeal lymphoepithelioma. On pathology review, a differential diagnosis of lymphoma and medullary carcinoma in addition to lelc can be generated 11. The undifferentiated malignant cells in a background of infiltrating lymphocytes can be mistaken for lymphoma, as occurred with the first reviewer. The application of immunohistochemistry can help to reveal the epithelial nature of the malignant cells and avoid a misdiagnosis. Similarly, the morphology of lelc of the breast is similar to that of medullary carcinoma and requires thorough review. These two entities show differences with respect to circumscription and the syncytial growth patterns of the tumour cells. Medullary carcinomas are reported to be well circumscribed and to displace adjacent breast tissue rather than invade it. The medullary tumour cells occur in syncytial masses (there is no noted equivalent in lelc of the breast). The stromal infiltrate in lelc has fewer plasma cells than are noted in medullary carcinoma, which manifests a prominent lymphoplasmacytic reaction. Recognition of these potential diagnostic pitfalls will facilitate an accurate diagnosis of this rare condition.

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma has been reported in a variety of anatomic sites that include skin 13–16, lacrimal and salivary glands 17,18, thyroid gland 19, thymus 20, breast 3, lung 21, esophagus 22, stomach 23, colon 24, hepatobiliary system 25,26, renal pelvis 27–30, ureter 28, kidney 27, bladder 31, prostate 27, uterine cervix 32, vulva 33,34, and vagina 35. The foregoing sites typically have better outcomes than are seen with aggressive nasopharyngeal tumours; however, they do demonstrate the potential for local spread, angioinvasion, and metastasis to lymph nodes. The paucity of published literature on both management and long-term follow-up makes recommendations difficult. For each anatomic site, measures to ensure local control (surgery or radiotherapy, or both) need to be combined with systemic therapy for the management of potential distant spread. With additional reports and longer periods of follow-up, improved insight into therapy and prognosis may be obtained.

As with all breast cancers, surgery is the primary therapy for lelc of the breast. Every woman in the published literature underwent an excision, quadrantectomy, or mastectomy. As in the more common breast cancer histologies, the clinical goal should be an assurance of clear margins. The presence of lymph node metastases in 4 of the 14 women who underwent an axillary lymph node dissection (28.6%) lends support to continued use of that procedure or of a sentinel lymph node biopsy. Internal mammary lymph nodes appear at risk of spread, given a notable parasternal recurrence in the case reported by Kurose et al. 8 and attributed to a nodal recurrence. Breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy both appear to be appropriate for primary therapy.

Radiotherapy was administered adjuvantly in 4 of the 13 reported cases in which information on additional treatment after surgery was available. The dose–fractionation and target volume were described in 2 of those 4 cases as 50.4 Gy delivered in 28 fractions to the breast alone. In 3 of the 4 cases, the women had undergone a wide local excision or a quadrantectomy, in which case the use of adjuvant radiotherapy would be consistent with standard breast-conserving therapy 36. A therapeutic rationale for the use of radiotherapy after mastectomy in the case reported by Dadmanesh et al. 5 was not provided. None of the women who underwent mastectomy had tumours larger than 5 cm or a burden of regional nodal metastasis, but it would not be unreasonable to consider the use of adjuvant radiotherapy in women who may have those features and to take an approach analogous to that for stage iii or locally advanced breast cancer 37. Radiotherapy may also have a palliative role, given that a parasternal mass treated with 40 Gy and cef (cyclophosphamide–epirubicin, and 5-fluorouracil) chemotherapy appears to have had some effect.

Chemotherapy was used in 2 of the reported cases. In the case reported by Peştereli et al. 10, it was used in an adjuvant fashion, and in the case of Kurose et al. 8, it was delivered after recurrence. Unfortunately, the Kurose group described only chemotherapy with cef being given. Assessment of efficacy is confounded by the delivery of radiotherapy, with one of the interventions or their combination having produced a response. However, in lelc arising in other anatomic sites, chemotherapy has demonstrated some potential efficacy and may merit consideration in cases involving the breast were there to be evidence of metastatic spread 18,21,27,31,38–40. Unfortunately, the data are insufficient to provide definitive guidance.

Hormonal therapy was used in 2 women, one of whom was negative for the estrogen and progesterone receptors and experienced recurrence. Of the 16 reported patients, hormone receptor status was known for 15, 8 of whom (53%) were strongly or weakly estrogen receptor–positive, with 4 being strongly or weakly progesterone receptor–positive. In reviewing the pathology, receptor status should always be assessed, with consideration given to hormonal therapy in women who are receptor-positive.

Interestingly, the present case is the first to assess the CD117 surface marker in lelc of the breast. The cell-surface marker CD117, a proto-oncogene, is a receptor for cytokine stem cell factor. Cellular signaling through CD117 plays a key role in cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. CD117 is most commonly associated with gastrointestinal stromal tumours, but it has also been reported in other malignancies 41,42. The significance of c-Kit expression in lelc of the breast, with its prognostic and therapeutic implications, needs further investigation 43.

In synthesizing the available historical case material and applying the standard oncologic principles of breast cancer therapy, a sentinel lymph node dissection was undertaken. After radiocolloid and patent blue dye injection, 2 sentinel lymph nodes were identified. On pathology review, no evidence of metastatic disease was detected. In the absence of nodal metastatic spread and given the paucity of data, the utility of chemotherapy is uncertain and may not be of benefit. An anthracycline-based regimen was offered to the patient, who declined it. Whole-breast radiotherapy with a dose of 5000 cGy in 200-cGy fractions was delivered over 5 weeks, with no noted adverse sequelae. Since completion of therapy, the patient has been seen for follow-up surveillance with medical history, physical examination, and annual mammography. Three years after primary therapy, she remains well, with no evidence of disease recurrence.

3. CONCLUSIONS

Lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma of the breast is a rare clinical entity. Pathologic diagnosis depends on a thorough histologic and immunohistochemical examination. The known characteristic pathologic features of lelc ensure an appropriate diagnosis. The demonstrated metastatic potential of lelc means that thorough staging, with axillary assessment and imaging is recommended. Breast-conserving therapy appears to be appropriate, although further follow-up is recommended before the use of breast-conserving surgery alone. The role of systemic therapy is unclear given the small series of patients available. In the presence of locoregional or distant metastasis, chemotherapy should be considered. Hormone receptors are noted to be positive (strongly or weakly) in a significant number of women and merit inclusion, where appropriate. The potential for targeted agents merits further consideration and may help to better elucidate the causes of this rare pathology.

4. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no known financial conf licts of interest.

5. REFERENCES

- 1.Schmincke A. On the subject of lymphoepithelial tumours [German] Beitr Pathol Anat. 1921;68:161–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regaud C, Reverchon L. A case of squamous epithelioma in the body of the superior maxillary [French] Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol. 1921;42:369–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar S, Kumar D. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast. Mod Pathol. 1994;7:129–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cristina S, Boldorini R, Brustia F, Monga G. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast. An unusual pattern of infiltrating lobular carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2000;437:198–202. doi: 10.1007/s004280000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dadmanesh F, Peterse JL, Sapino A, Fonelli A, Eusebi V. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast: lack of evidence of Epstein–Barr virus infection. Histopathology. 2001;38:54–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilvan S, Celik V, Ulker Akyildiz E, Senel Bese N, Ramazanoglu R, Calay Z. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast: is it a distinct entity? Clinicopathological evaluation of two cases and review of the literature. Breast. 2004;13:522–6. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(04)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulka J, Kovalszky I, Svastics E, Berta M, Füle T. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast: not Epstein–Barr virus–, but human papilloma virus–positive. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurose A, Ichinohasama R, Kanno H, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast. Report of a case with the first electron microscopic study and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2005;447:653–9. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naidoo P, Chetty R. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast with associated sclerosing lymphocytic lobulitis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:669–72. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0669-LLCOTB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peştereli HE, Erdogan O, Kaya R, Karaveli FS. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast. APMIS. 2002;110:447–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.100602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saleh R, DaCamara P, Radhi J, Boutross–Tadross O. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast mimicking nodular sclerosing Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Breast J. 2005;11:353–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.21577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanati S, Ayala AG, Middleton LP. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the breast: report of a case mimicking lymphoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2004;8:309–15. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arsenovic N. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: new case of an exceedingly rare primary skin tumor. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavalieri S, Feliciani C, Massi G, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2007;20:851–4. doi: 10.1177/039463200702000424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaich AS, Behroozan DS, Cohen JL, Goldberg LH. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a report of two cases treated with complete microscopic margin control and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:316–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, Tomaszewski MM, Gupta A, Ojha J. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blasi MA, Ventura L, Laguardia M, Tiberti AC, Sammarco MG, Balestrazzi E. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma involving the lacrimal gland and infiltrating the eyelids. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21:320–3. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2010.6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloching M, Hinze R, Berghaus A. Lymphepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257:399–401. doi: 10.1007/s004050000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shek TW, Luk IS, Ng IO, Lo CY. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the thyroid gland: lack of evidence of association with Epstein–Barr virus. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:851–3. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(96)90461-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicolato A, Ferraresi P, Bontempini L, Tomazzoli L, Magarotto R, Gerosa M. Multiple brain metastases from “lymphoepithelioma-like” thymic carcinoma: a combined stereotacticradiosurgical approach. Surg Neurol. 2001;55:232–4. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(01)00361-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho JC, Wong MP, Lam WK. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung. Respirology. 2006;11:539–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada T, Tatsuzawa Y, Yagi S, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like esophageal carcinoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:542–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02482349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herath CH, Chetty R. Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoepithelioma-like gastric carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:706–9. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-706-EVLGC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kon S, Kasai K, Tsuzuki N, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of rectum: possible relation with ebv. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197:577–82. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee W. Intrahepatic lymphoepithelioma-like cholangiocarcinoma not associated with Epstein–Barr virus: a case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2011;4:68–73. doi: 10.1159/000324485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nemolato S, Fanni D, Naccarato AG, Ravarino A, Bevilacqua G, Faa G. Lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4694–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamas EF, Nielsen ME, Schoenberg MP, Epstein JI. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary tract: a clinicopathological study of 30 pure and mixed cases. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:828–34. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terai A, Terada N, Ichioka K, Matsui Y, Yoshimura K, Wani Y. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the ureter. Urology. 2005;66:1109. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haga K, Aoyagi T, Kashiwagi A, Yamashiro K, Nagamori S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Int J Urol. 2007;14:851–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada Y, Fujimura T, Yamaguchi T, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Int J Urol. 2007;14:1093–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porcaro AB, Gilioli E, Migliorini F, Antoniolli SZ, Iannucci A, Comunale L. Primary lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder: report of one case with review and update of the literature after a pooled analysis of 43 patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003;35:99–106. doi: 10.1023/A:1025981106561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaul R, Gupta N, Sharma J, Gupta S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Cancer Res Ther. 2009;5:300–1. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.59916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niu W, Heller DS, D’Cruz C. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the vulva. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2003;7:184–6. doi: 10.1097/00128360-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slukvin II, Schink JC, Warner TF. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the vulva: a case report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2003;7:136–9. doi: 10.1097/00128360-200304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCluggage WG. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the vagina. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:964–5. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.12.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whelan T, Olivotto I, Levine M, on behalf of Health Canada’s Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: breast radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery (summary of the 2003 update) CMAJ. 2003;168:437–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shenkier T, Weir L, Levine M, Olivotto I, Whelan T, Reyno L, on behalf of the Steering Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Care and Treatment of Breast Cancer Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: 15. Treatment for women with stage iii or locally advanced breast cancer. CMAJ. 2004;170:983–94. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1030944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chow TL, Chow TK, Lui YH, Sze WM, Yuen NW, Kwok SP. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of oral cavity: report of three cases and literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;31:212–18. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hidaka H, Nakamura N, Asano S, Yokoyama J, Yoshida N, Toshima M. A case of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma arising from the palatine tonsil. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2002;198:133–40. doi: 10.1620/tjem.198.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mayer EK, Beckley I, Winkler MH. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder—diagnostic and clinical implications. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007;4:167–71. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laforga JB, Gasent JM. Expression of CD117 in primary anorectal malignant melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:176–7. doi: 10.5858/133.2.176.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steigen SE, Eide TJ. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (gists): a review. APMIS. 2009;117:73–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eroglu A, Sari A. Expression of c-Kit proto-oncogene product in breast cancer tissues. Med Oncol. 2007;24:169–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02698036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]