Abstract

A modified theory is proposed for extracting cell dielectric properties from the peak frequency measurement of electrorotation (ER) and the crossover frequency measurement of dielectrophoresis (DEP). Current theory in the literature is based on the low frequency (DC) approximations for the equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity, which are valid when the measurements are performed in a medium with conductivity less than 1 mS/m. The present theory extracts the cell properties through optimizing an expression for the medium conductivity in terms of the peak ER, or DEP crossover, frequency according to its definition using full expressions of equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity. Various levels of approximation of the theory are proposed and discussed through a scaling analysis. The present theory can extract both membrane and interior properties from the low and the high peak ER, or DEP crossover, frequencies for any medium conductivity provided the peak ER, or DEP crossover, frequency exists. It can be reduced to the linear theory for the low peak ER and DEP crossover frequencies in the literature when the medium conductivity is less than 10 mS/m. However, we can determine the membrane capacitance and conductance via the slope and intercept, respectively, of the straight line fitting of the ER peak and DEP frequency against medium conductivity data according to the linear theory only when the intercept dominates the experimental uncertainty, which occurs when the medium conductivity is less than 1 mS/m in practice.

INTRODUCTION

Dielectrophoresis (DEP) and electrorotation (ER) were employed extensively in particle/cell manipulation1, 2, 3 and characterization4, 5, 6, 7, 8 in the literature. DEP (or ER) is a phenomenon associated with the movement (or rotation) of a particle or cell under the action of a non-uniform (or uniformly rotating) electric field. As the phenomena of DEP and ER as well as that of the traveling wave dielectrophoresis (twDEP) are all originated from the interaction of the applied field with its induced dipole moment on the particle associated with the polarization, they can be studied systematically and simultaneously in a unified approach under the scope of electrostatics,9, 10, 11 and it is convenient to group DEP, ER, and twDEP together under a title called “generalized dielectrophoresis”9, 12 for discussion. Detailed phenomena, theory, and application can be found from the books by Pohl,13 Jones,14 Morgan and Green,15 Hughes,16 and Chang and Yeo,17 as well as the recent review articles by Pethig18 and Lei and Lo.12 Lei and Lo reviewed the theory of generalized dielectrophoresis, including both the quasi-static and transient theory of spherical and ellipsoidal particles in an unbounded medium, and the quasi-static theory of spherical particle in the vicinity of wall(s). They also provided a section on the theoretical discussion of the Clausius-Mossotti factor, peak frequency of ER, and crossover frequency of DEP, using the human erythrocyte as an example for illustration. Effects of cell geometry, medium conductivity, and cytoplasm dispersion on both the real and imaginary parts of the Clausius-Mossotti factor were discussed. Also studied was the adequacy of representing the equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity using both the low frequency (DC) and high frequency (cytoplasm) limits for the evaluation of the low and high crossover (or peak) frequencies, respectively. Those results are helpful for the present study.

In the area of cell characterization, a major effort is to extract cell dielectric properties, such as membrane capacitance and membrane conductance, from the responses of the ER and DEP experiments. The procedures consist of suspending the cells in a medium of conductivity and permittivity , and applying a non-uniform stationary ac field for DEP experiments8, 19, 20 or a uniform rotating ac field for ER experiments.4, 20 Details of the apparatus and procedures can be found from the literature.19, 20 The measurements that are usually analyzed are the DEP cross-over frequency , defining the transition frequency between positive and negative DEP, and the peak frequency at which the electrorotation rate attains its maximum value. Full expressions for the effective dielectric properties14 of a cell, in terms of , and , involve nonlinear equations which cannot be solved analytically. To overcome this problem, the customary practice is to employ the low-frequency (DC) approximations of Schwan21 (see also Arnold and Zimmermann4) for the effective conductivity and permittivity of a cell

| (1a) |

and

| (1b) |

where , and are the conductance, conductivity, capacitance, and permittivity, respectively, of the cell membrane, and R and δ are the cell radius and membrane thickness, respectively. This approximation has been used in the DEP and ER studies of cell apoptosis,22, 23, 24 as well as for studies of induced cell differentiation and activation,19, 25, 26 for example.

In summary, the state-of-art theory and method in the current literature for deriving cell dielectric properties from the peak frequency measurement of ER and the crossover frequency measurement of DEP are based on two physical reasons: (1) the definitions of peak and crossover frequencies, which are associated with the Maxwell-Wagner phenomenon and (2) the low frequency (DC) limits for representing the effective cell permittivity and conductivity. There may exist two crossover (or peak) frequencies in the DEP (or ER) experiments if they are performed in a medium with suitable conductivity, and here mainly the lower frequency is considered. For the higher peak and crossover frequencies, it was suggested12 to apply the high frequency limit, i.e., assuming that both the equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity can be approximated as those of the cytoplasm (or cell’s interior), instead of the low frequency (DC) limit.

Consider the cases with the lower peak and crossover frequencies. The low (DC) frequency limit is valid only when the measured peak (or crossover) frequency is sufficiently low, which is the case when the experiment was carried out in a medium with sufficiently low conductivity (less than 1 mS/m according to the latter analysis in Sec. 2A). This is not satisfied for many experiments in the literature. For example, the DC limit is valid when the frequency is less than 10 kHz, and the effective cell conductivity is 52% higher than the DC limit when the frequency equals 100 kHz for human erythrocyte.12 On the other hand, the crossover frequency of the bovine red blood cell7 is 255 kHz; the measured crossover and peak frequencies of pancreatic beta-cells20 are from 207 to 427 kHz and 73 to 576 kHz, obtained from the DEP (with medium conductivity 48.7–101.4 mS/m) and ER (with medium conductivity 11.5–101.4 mS/m) measurements, respectively. Those crossover and peak frequencies in the literature are of one to two orders greater than the frequency that the low frequency assumption can be applied. There also exists 300% difference between the effective membrane conductance obtained from DEP and ER measurements reported for pancreatic beta-cells,20 which could have resulted from the invalid low frequency (DC) approximation. Furthermore, the low frequency approximations are certainly not valid for extracting cell dielectric properties from the higher peak and crossover frequency (of order 100 MHz) measurements.8, 27

Thus, the current theory is inappropriate for extracting cell properties from the experimental data for many cases in the literature, and it is worthwhile to review when the current theory will fail, and what kind of remedy should be made so that cell dielectric properties can still be studied using the DEP and ER experiments. The goal of this paper is to provide a modification of the current theory and method. The second part of the current theory (the DC limit approximation) will be replaced by the full expressions of the effective conductivity and permittivity according to the physics. In doing so, it will be found that the modified theoretical model will be described by a nonlinear equation for the peak (or crossover) frequency. The optimization method for extracting cell properties in the current literature19 cannot be applied directly for such a nonlinear equation, and an alternative method will be proposed in Sec. 2C. The present modified theory and method are both valid for essentially all medium conductivity values, and for both the low and the high peak (or crossover) frequencies, provided they exist.

THEORY

Current theory

The angular frequency corresponding to the peak rotation of a particle in a rotating electric field is4

| (2) |

where is the peak frequency, and is called the Maxwell-Wagner interfacial polarization time constant, which is associated with the accumulation of free charge at the surface of the cell. Equation 2 becomes

| (3) |

under the low frequency approximations in Eqs. 1a, 1b together with the assumption

| (4) |

The angular DEP crossover frequency19, 12

| (5) |

where is the crossover frequency, and . The crossover frequency exists only when is negative.12 Equation 5 reduces to

| (6) |

following the assumptions in Eqs. 1a, 1b, 4. Pethig et al.20 further reduced Eq. 6 to

| (7) |

under the condition

| (7a) |

The conductance in Eqs. 1b, 3, 6, 7 can be replaced by its effective value,4, 20 which takes into account the additional surface conductance associated with the double layer effect outside the particle (cell).

Equation 3 or 7 shows a linear relationship between or and . Such a linear relationship is convenient for extracting membrane properties from experimental data, as we can determine easily from the slope and from the intercept of the straight line which fits the experimental data. Pethig et al.20 found consistent results for from both measurements, but from of DEP experiment is three times greater than that from of ER experiment. Detailed examination of the data of Ref. 20 shows that the first and the second terms of Eqs. 3, 7 are of order unity while the third terms are of order , which are even of one order less than the standard deviation of the measured values of the first terms, and . This is why both the crossover and the peak frequency measurements give consistent results for but not , as the determination of is based mainly on the balance between the two major terms in Eq. 3 or 7, while the determination of needs the minor term, which is within the range of experimental uncertainty. In order to have a reliable measurement of using the above linear theory, we need to design an experiment such that all the three terms in Eq. 3 or 7 are of the same order of magnitude. One way to accomplish this is to lower the two major terms in the equations. This can be done by reducing the medium conductivity for experiment as both and decrease linearly with ,12 with the minor term remaining essentially unchanged. Two DEP crossover and ER peak frequencies may exist when the medium conductivity lies between and the conductivity of the cell interior .12, 18 This present study concerns mainly the lower of these two frequencies, referred to here as and , respectively. According to the data in Ref. 20, it is estimated that the membrane conductance can be reasonably evaluated if is reduced to the order of S/m. However, Eq. 7a is not satisfied when , and we need to apply Eq. 6 instead of Eq. 7 for extracting membrane properties. For a nonlinear expression such as that of Eq. 6, we may estimate the membrane properties through an optimization procedure such as that described by Huang et al.19 When , the linear equations, Eqs. 3, 7, are not adequate for extracting the membrane conductance. More detailed linear theory will be discussed in Sec. 2D.

Validity of the low frequency approximations for the equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity

The low-frequency (DC) approximations in Eqs. 1a, 1b employed in the current literature are valid only when the applied angular frequency (ω) is sufficiently small. However, the frequencies, and , are of order 1 MHz according to experiments of Pethig et al.20 It is therefore appropriate to question the validity of applying the low frequency approximations for the representation of the equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity.

The Clausius-Mossotti factor, , is defined as14

| (8) |

for a uniform spherical particle in a uniform medium, where , and ω is the applied electric angular frequency, with (or ) and (or ) the conductivity and permittivity of the particle (or medium), respectively. The peak frequency in Eq. 2 is obtained by setting , and the crossover frequency in Eq. 5 is obtained by setting , with the complex particle permittivity, , replaced by its equivalent value, . The peak and the crossover frequencies are not merely interrelated in a mathematical sense as above but also connected to each other physically. The induced dipole moment associated with the polarization of the particle/cell with loss in an applied electric field has two components,9, 12 one is in-phase and the other is 90° out-of-phase of the applied field, and their magnitudes are proportional to the real and imaginary parts of the Clausius-Mossotti factor, respectively. Specifically, the DEP crossover occurs at an applied electric frequency when the DEP force or the real part of the CM factor vanishes. At such an angular crossover frequency , the induced dipole moment has only the out-of-phase component, and it is always perpendicular to the applied field. The corresponding magnitudes of the time average DEP torque on the particle/cell equals , where E is the magnitude of the applied field. However, the DEP torque, and thus the rotation rate of the particle/cell, cannot be ensured to attain their maximum values when as may not equal , the local maximum value of . occurs when , which is true only for according to Eqs. 2, 5. In practice, is close to , as shown in the example of human erythrocytes.12

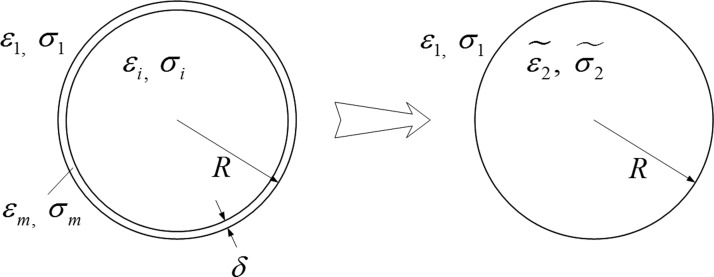

For a two shell model of a spherical cell with radius, R, and membrane thickness, δ, as shown in Figure 1, the complex permittivity of the equivalent cell is given by14

| (9) |

where and , with (or ) and (or ) the conductivity and permittivity of the membrane (or the interior material), respectively. For most mammalian cells, R is of three orders greater than δ, and so Eq. 9 can be simplified as (see Jones14)

| (10) |

under the conditions , , and . The real and imaginary parts of Eq. 10 can be expressed explicitly as

| (11a) |

and

| (11b) |

respectively, where is the permittivity of free space. The low frequency limit can be studied via a perturbation analysis of Eqs. 11a, 11b with a small value of ω. The leading order results are

| (11c) |

and

| (11d) |

Equations 11c, 11d can be reduced further to the DC limit approximations in Eqs. 1a, 1b if and are satisfied.

Figure 1.

The particle with a thin shell can be replaced by an equivalent uniform particle with equivalent permittivity and conductivity .

For human erythrocytes based on Gimsa et al.,28, , (from low to high frequency), (from low to high frequency), and (using an equilibrium radius 2.62 μm and ). Other mammalian cells in the literature have values of similar orders. Thus, we may take

| (12) |

to estimate the relative importance of the terms in Eqs. 11a, 11b. These terms can be categorized into two groups: one with a factor and one without it, and they vary across several orders of magnitudes. Retaining the leading term of each group in both the numerator and the denominator, Eqs. 11a, 11b reduce to

| (13a) |

and

| (13b) |

which are valid for all ω, the applied electric angular frequency. It is important that only “the terms of three orders less” are neglected because the term required for the determination of the membrane conductance is of two orders less than the leading term, as discussed in Sec. 2A. Equations 13a, 13b reduce to Eqs. 1a, 1b, respectively, as ω tends to zero.

The crossover and the peak angular frequencies (ω) are of the order of 1 MHz in the experiments of Ref. 20, and are quite far from zero. With , the terms in Eqs. 13a, 13b are

| (14a) |

and

| (14b) |

respectively. Thus Eq. 13a can be further simplified to

| (15) |

However, Eq. 13b remains unchanged. Equations 15, 13b are the most simplified forms of Eqs. 11a, 11b capable of extracting membrane conductance from the experimental data,20 based on the scales set in Eq. 12 and .

Comparing Eqs. 15, 13b with Eqs. 1a, 1b, respectively, there exist additional terms in Eqs. 15, 13b, so that they are different from the low frequency (DC) approximations. By retaining the scales in Eq. 12 and neglecting only the terms when they are of three orders less in comparison with the term left in either the numerator or denominator, further simplification is only possible by reducing ω. For example, Eq. 15 becomes

| (16a) |

which is the DC limit in Eq. 1a. However, Eq. 13b becomes

| (16b) |

The additional term, , is of the same order as the DC limit term, . Equation 16b can only be approximated as the DC limit result in Eq. 1b, i.e.,

| (16c) |

and the term is of one order less than . In the experiments of Ref. 20, the ER peak and DEP crossover frequencies range from for and for , respectively, which are well above ω = 0.1 MHz when the DC limit is a good approximation. However, it is found from the literature12, 18 that the ER peak and the DEP crossover frequencies decrease with the medium conductivity. Thus, Eqs. 16a, 16b, or even Eqs. 16a16a, 16c, can be applied if experiments are carried out in a medium of lower conductivity. For example, the upper bound ω = 0.3 MHz for Eqs. 16a, 16b to be valid corresponds to and 10 mS/m from the extrapolation of the ER and DEP data,20 respectively. Thus, Eqs. 16a, 16b may be applied to analyze the data when . Similarly, the upper bound ω = 0.1 MHz for Eqs. 16a, 16c to be valid corresponds to and 2.9 mS/m from the extrapolation of the ER and DEP data,20 respectively, and thus Eqs. 16a, 16c, the low frequency (DC) approximations, are appropriate when . Different levels of approximation for the equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity according to the above discussion are summarized in Table TABLE I.. Note that the appropriate ranges for and in Table TABLE I. are estimated based on the scales in Eq. 12—they require modification if different scales are employed for the cell properties.

TABLE I.

Different levels of approximation for the equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity appropriate for different values of medium conductivity , electrorotation peak , and dielectrophoresis crossover angular frequencies.

Modified theory

A modification of the theory is now presented for extracting the cell properties from the ER peak and DEP crossover frequency measurements when the low frequency (DC) approximation cannot be applied. In order to provide a remedy to the previous theory in the literature, the full expressions (Eqs. 11a, 11b) or their simplified expressions (Eqs. 13a, 13b or Eqs. 15, 13b) are employed instead of the low frequency (DC) approximations (Eqs. 1a, 1b), to represent the equivalent permittivity and conductivity in Eqs. 2, 5. Nonlinear algebraic equations for and are then obtained, which are expressed implicitly in terms of the medium conductivity , the medium permittivity, and cell properties. In order to extract the cell properties from these nonlinear equations, the optimization method described previously by Huang et al.19 is employed. The first step to apply the optimization method is to express explicitly the function to be optimized. Unfortunately, an explicit solution for (or ) from the above mentioned nonlinear equation cannot be obtained. However, a solution for can be obtained and is expressed explicitly in terms of (or ). Thus, the optimization method can still be applied after interchanging the roles of the dependent and independent variables. For the ER peak frequency data, Eq. 2 can be rewritten as

| (17a) |

As and are both functions of ω (equals ) and the cell properties, but not functions of according to Eqs. 11a, 11b, 13a, 13b, or 15, 13b, then Eq. 17a represents an explicit function for . Similarly, for the DEP crossover frequency data, a solution can be found for from Eq. 5. The physically possible, positive, root is

| (17b) |

Note that is retained here in Eqs. 17a, 17b but is neglected under the usual literature assumption of Eq. 4. For most of the experiments, , and at low frequencies is of two orders less than according to the scaling in Eq. 12. This term is retained because it is of the same order as the term for determining the membrane conductance.

Equations 17a, 17b can be written in a functional form as

| (18) |

where f stands for either or . Equation 18 is written in the same form, using , , and as variables, as those in the literature, but with more variables because the full expressions for and are employed. In Eq. 18, and are known quantities, and assumed to be and 1000, respectively, in the present study, f and R are measured from the experiments, and is a set of parameters to be determined through the optimization by minimizing the variance,

| (19) |

where is calculated using Eq. 18, is the medium conductivity in the experiment, and N is the number of the experimental data set, Rf and , employed for evaluating the cell properties.

Equation 18 is written for the most general case, employing the full expressions for and given by Eqs. 11a, 11b. They may take simpler forms if different levels of approximation (Table TABLE I.) are adopted. For example, Eq. 18 becomes

| (20) |

if the low frequency (DC) approximations together with Eq. 4 is employed. Equation 20 is consistent with the equation employed in Huang et al.,19 apart from their using an expression for f in terms of , and , i.e.,

| (20a) |

and performing an optimization by minimizing the variance

| (20b) |

where is the experimental value. Calculated results based on different levels of approximation are discussed in Sec. 3. The calculation for optimization can be performed rather easily with the aid of some commercial software, such as MATLAB and MATHEMATICA. The results in Sec. 3 were calculated using MATHEMATICA.

Linear theory for medium conductivity less than 0.01 S/m

Analytical results are available for and for both Level 4 and 5 approximations in Table TABLE I.. The result under the approximation of Level 5 gives the classical literature result.4, 20 The result using the Level 4 approximation, for the case , will now be discussed.

The peak frequency of electrorotation

With Eqs. 16a, 16b, 4, Eq. 2 can be written as

| (21) |

where

| (21a) |

in Eq. 21 is the additional term in comparison with the previous theory in Eq. 3. One of the two roots of Eq. 21 is given by

| (22) |

This root predicts that the ER peak frequency increases with , which is consistent with the experimental finding.20 Equation 22 can be approximated as

| (23) |

after using a binomial series expansion under the assumption

| (23a) |

Note that and accords to the scales in Eq. 12, whilst is the typical range reported in the literature.4, 20 Thus, Eq. 23a can be satisfied fairly if , and Eq. 23 is a good approximation to Eq. 22 for interpreting some of the previous experiments. Furthermore, the term in Eq. 23 can be neglected as it is of two orders less than and one order less than in Eq. 23 when . Thus, Eq. 23 can be reduced to

| (24) |

which is the same as Eq. 3 employed in the literature.4, 20 However, it should be noted that although Eqs. 3, 24 give the same result, they were derived under different assumptions. Equation 24 given here is derived using Eqs. 1a, 16b, 4, 23a, which differ significantly from Eqs. 1a, 1b, 4 employed for deriving Eq. 3 in the literature. In principle, the linear form of Eq. 24 provides the means to determine the cell dielectric properties from the slope and intercept of the straight line correlating the experimental data. However, as discussed in Sec. 2A, is still of one order less than when ; it is of the same order as the experimental uncertainty of for the ER experiments. Although the upper limit for the linear theory to be valid has been extended from under the DC limit approximation to here, the above mentioned “slope and intercept method” is still not applicable in practice for experiments with because of the experimental uncertainty. The “slope and intercept method” associated with the linear theory in Eq. 24 does provide reliable results if it is applied to experiments with . For ,it is suggested to use Eq. 22 to perform optimization for extracting cell properties under the Level 4 approximation in Table TABLE I..

The crossover frequency of dielectrophoresis

With Eqs. 16a, 16b, 4, Eq. 5 can be written as

| (25) |

where

| (25a) |

The four roots of Eq. 25 include the physically realistic (real and positive) one given by

| (26) |

Equation 26 can be approximated as

| (27) |

after using a binominal series expansion under the condition

| (27a) |

which can be satisfied nicely when . Following similar scaling analysis as that in Eq. 23, Eq. 27a can be further reduced to

| (28) |

It is also interesting to note that Eq. 28 is the same as Eq. 7, reported previously,20 although both equations were derived under different assumptions. The one derived here is based on Eqs. 1a, 16b, 4, 27a, which differ significantly from Eqs. 1a, 1b, 4, 7a employed in Ref. 20. Similar discussion of Eq. 24 for the linear theory of peak frequency also applies here for the linear theory of crossover frequency described by Eq. 28.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

To illustrate the applicability and use of the theory developed here, the experimental data of Ref. 20 have been used to calculate cell membrane and cell interior properties with different levels of approximation. The results are summarized in Table TABLE II.. The method, including the assumptions (see Table TABLE I.) and the equations employed for optimization, are indicated in the first column of Table TABLE II.. Pethig et al.20 presented their results in three groups: ER peak frequency for (column 5); ER peak frequency for (column 3); and the DEP crossover frequency for (column 6). Calculations based on both sets of the ER data () are shown in the fourth column of Table TABLE II.. The results in this table are presented in order of decreasing approximation, with the calculations in the bottom row employing the least approximations.

TABLE II.

Comparison of the cell dielectric properties using different approximations based on the experimental data of Ref. 20. The results in the row denoted by “slope and intercept” are the results adopted from Ref. 20, apart from the values in the fourth column, which were calculated in the present study. The results in the rows denoted by Level 5 and Level 4-1 are obtained via optimization by minimizing Δf in Eq. 20b. Other results are calculated by minimizing Δσ1 in Eq. 19 under different levels of approximation in Table TABLE I.. σ1, Gm, Cm, and σi are in unit mS/m, S/m2, mF/m2, and S/m, respectively.

| ER | ER | ER | DEP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ1 | 48.7–101.4 | 11.5–101.4 | 11.5–42.5 | 48.7–101.4 | |

| Slope and Intercept | Gm | 179 | −169 | 261 | 601 |

| Cm | 10.23 | 10.14 | 10.65 | 9.96 | |

| Level 5 with Eqs. 3, 7 | Gm | 103 | 179 | 230 | 889 |

| Cm | 10.20 | 10.12 | 10.62 | 9.90 | |

| Level 4-1 with Eqs. 22, 26 | Gm | 11099 | 2341 | 1103 | 1016 |

| Cm | 18.03 | 12.69 | 10.77 | 9.26 | |

| σi | 1.33 | 1.12 | 0.80 | 1.14 | |

| Level 4-2 with Eq. 17a, Eq. 17a and ɛ1 = 0 | Gm | 10907 | 2241 | 1254 | 878 |

| Cm | 17.88 | 12.76 | 13.26 | 9.89 | |

| σi | 1.33 | 1.16 | 0.78 | 1.25 | |

| Level 4 with Eqs. 17a, 17b | Gm | 10320 | 2110 | 1310 | 901 |

| Cm | 17.48 | 12.53 | 13.52 | 9.82 | |

| σi | 1.32 | 1.14 | 0.74 | 1.24 | |

| Level 3 with Eqs. 17a, 17b | Gm | 1321 | 1197 | 1181 | 935 |

| Cm | 11.92 | 11.32 | 11.20 | 10.11 | |

| σi | 0.97 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 1.23 | |

| Level 2 with Eqs. 17a, 17b | Gm | 1314 | 1202 | 1176 | 927 |

| Cm | 12.04 | 11.31 | 11.13 | 10.04 | |

| σi | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 1.23 | |

| ɛi/ɛ0 | 170 | 151 | 142 | 112 | |

| Level 1 with Eqs. 17a, 17b | Gm | 1345 | 1214 | 1197 | 984 |

| Cm | 11.83 | 11.27 | 10.92 | 9.91 | |

| σi | 1.13 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 1.24 | |

| ɛi/ɛ0 | 193 | 169 | 161 | 134 |

Apart from column 4, the row of data denoted by “slope and intercept” are the data adopted from Ref. 20. The results were obtained from the slope (for ) and the intercept (for ) of the straight line which fits the experimental data. The remaining data in Table TABLE II. are calculated based on the optimization using different levels of approximation as stated in Table TABLE I.. The results in the rows denoted by “Level 5” and “Level 4-1” are obtained via optimization by minimizing in Eq. 20b. The other results are calculated by minimizing in Eq. 19.

The results for “Level 5” were calculated using the same equations as those obtained using the “slope and intercept” method. Both results agree well for but only fairly for for the DEP case and the ER case with lower medium conductivity. According to Ref. 20, there is a large discrepancy between obtained from the ER peak frequency and the DEP crossover frequency measurement (601 versus 179 S/m2) at the higher medium conductivity range. The discrepancy is even larger (889 versus 103 S/m2) according to the Level 5 calculation. Also, although a positive value of 179 S/m2 is obtained by calculation, a physically impossible negative (−169 S/m2) is from the slope and intercept method for the ER case for . Such discrepancies and abnormality are not surprising results as the experimental uncertainty is of one order greater than the term employed for determining according to the linear theory as discussed in Sec. 2A. It will now be shown that such discrepancies and abnormality disappear as the inappropriate assumptions imposed on the linear theory are removed.

The results for “Level 4-1” and “Level 4-2” are based on the same theoretical background, except the former is obtained by minimizing while the latter by minimizing . They agree with each other as expected. The difference between the results for “Level 4-2” and “Level 4” is that the assumption in Eq. 4 has been applied to the former case (in accordance with normal practice reported in the literature). The agreement of the results between these two cases indicates that Eq. 4 is an acceptable approximation along with the Level 4 approximation. Thus, either one of these three cases (Level 4-1, Level 4-2, and Level 4) can be chosen as the representative case for the Level 4 approximation. The large discrepancy of between the results from the DEP and ER measurements still exist under the Level 4 approximation, which implies that Level 4 is still too simplified for extracting cell properties for . Note that the Level 4 approximation is appropriate for , as discussed in Sec. 2B.

As also discussed in Sec. 2B, all the neglected terms in the equations for and should be at least of one order less than the term involved in the determination of if is to be correctly determined. Such a condition is satisfied for the Level 3, 2, and 1 approximations and explains why the results in Table TABLE II. for these three levels are in agreement. It should also be noted that the results from ER measurements (column 3) are consistent with those from DEP measurements (column 6). The discrepancies for the data on the same row for Levels 3, 2, and 1 can be considered to be acceptable, because they are of the same order of the experimental uncertainty. The discrepancies for , , , and are within 37%, 19%, 8.8%, and 44%, respectively, across each row of the results of Level 1 (similar for the results of Levels 2 and 3). The corresponding discrepancies are 23%, 14%, 33%, and 26%, respectively, if the ER results () are compared with the DEP results. These discrepancies probably arise from the limited numbers of data and may decrease if more data points are employed for the optimization procedure. It is also found that the data in each row for Levels 3, 2, and 1 are essentially independent of the medium conductivity for the present conductivity range.

The average results of Level 1 are , , and , which imply that and if the membrane thickness, δ, is taken as 5 nm. The results and agree nicely, but those of and agree only fairly with the scales in Eq. 12. If these updated values are used for the scales, the recalculated scaling analyses of Eqs. 11a, 11b in Sec. 2B shows that Eq. 13a remains the same, but Eq. 13b becomes

| (29) |

There exists an additional term , which is of two orders less than . It is expected that the results of Level 2 in Table TABLE II. will alter slightly and approach more closely to those of Level 1 if Eq. 29 is employed instead of Eq. 13b in the Level 2 approximation. Note that the above average membrane conductivity for the pancreatic beta-cells, , is the effective membrane conductivity, which includes the surface conductance associated with the double layer effect outside the cells.

On comparing the data in each column of Table TABLE II., we find that for the ER data with and , use may be made of the approximations at either Level 1, 2, or 3, and even at Level 4 if the medium conductivity is reduced . For the DEP case, it is interesting to find that even the Level 5 approximation can provide fairly good results. The linear theory of Level 5 approximation can be applied here for the DEP case but not for the ER case probably because the assumption in Eq. 27a for DEP is fairly satisfied but not the assumption in Eq. 23a for ER. According to the discussion in Sec. 2D2, the equation in the Level 5 calculation for the DEP case is the same as that in the Level 4 calculation with the additional assumption, Eq. 27a. Thus, it is not surprising that the value accordingly to the Level 5 calculation agrees with that under the Level 4 calculation. However, is underestimated by 32% if it is evaluated from the intercept data.

As the cell dielectric properties extracted from both the DEP crossover and the peak ER measurements agree with each other provided, the Level 3, 2, or 1 approximation is employed for the calculation, one can then use the DEP (or ER) data to find cell properties and use the ER (or DEP) as an independent check for the result. Since there is no assumption made on the frequency for the Level 1 and 2 calculations, they can be employed to extract the cell dielectric properties from the high peak and crossover frequency experimental data. One can then study the changes of the cell dielectric properties before and after the dispersion by comparing the data derived from the lower to that from the higher peak (or crossover) frequency. However, it is not possible to study the continuous change of the cell dielectric properties associated with the dispersion from only the peak and crossover frequency measurements. Such a study can be performed by measuring the Clausius-Mossotti factor for a broad range of frequency.

It is of interest to note more cell properties can be extracted from the data if fewer assumptions are employed. Only values for and can be evaluated using the Level 5 approximation, but , , and can be obtained using the Level 3 and 4 approximations, and values for , , , and using the Level 1 and 2 approximations.

The theory developed here can be applied to evaluate the additional surface conductance () associated with the double layer effect by replacing with the effective conductance,4, 20, in the associated equations, and thus with an additional parameter in Eqs. 18, 20, or 20a for performing optimization. The theory can be extended in a similar manner to the more sophisticated cell model that includes the cell nucleus or the cell including a wall (such as the yeast cell). In this case, Eq. 9 should be replaced by the 3-shell model,14, 16 and there are more parameters to be optimized in Eq. 18. The theory can also be applied to engineered particles, coated with a shell whose thickness is not small in comparison with its radius, by commencing the analysis at Eq. 9 instead of Eq. 10. Finally, the theory can also be extended to study ellipsoidal particles by replacing Eqs. 8, 9 with the associated expressions for ellipsoids.14, 16 However, the effect of particle shape on the Clausius-Mossotti factor12 is minor near the crossover frequencies, and thus it is expected that the particle shape is not a crucial factor for determining the cell dielectric properties using the DEP crossover frequency measurements. Such a guess was applied to analyze the DEP crossover frequency measurements of Kuczensk et al.29 for the red blood cells, which are of a biconcave discoid shape in isotonic media. A calculation was performed using the present theory by assuming that the red blood cell is a sphere with an equivalent radius 2.3 μm (so that it has the same volume as the original cell) and membrane thickness 8 nm. Kuczensk et al. reported three and six data points for the high and low DEP crossover frequency, respectively, and here the latter was analyzed. Those six experimental crossover frequencies () are approximately 0.03, 0.1, 0.2, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 MHz for medium conductivity 0.8, 2.1, 6, 17, 43, and 120 mS/m, respectively. It was found that (or ) and (or ) using the slope and intercept method; (or ) and (or ) under the Level 5 assumption; (or ), (or ), and under the Level 3 assumption; and (or ), (or ), , and under the Level 2 assumption. As four of the six experimental values of the angular crossover frequency () are greater than 1 MHz, Level 5, 4, and 3 assumptions are invalid (see Table TABLE I.), and thus it is not surprised that negative (physically incorrect) values of were predicted using those assumptions. However, the results based on Level 2 assumption do agree fairly with the experimental findings of Gimsa et al.,28, , , and .

The optimization method employed here is a standard and well accepted method in rigid body dynamics, engineering design, economics, and other research areas. It is particularly useful for the situation when there are more unknowns than the number of equations, such as the case in the present problem. For example, there are four parameters to be determined (and thus four unknowns) if Level 1 calculation is employed. If there exist five sets of experimental data, we then have five equations by substituting those data into Eq. 18 separately. Some physical criteria (such as that all the cell properties should be positive) can be imposed in the optimization procedure for parameter searching, so that the method is not just a curve fitting procedure. Although Huang et al.19 had applied a similar method using Eq. 20a to obtain the membrane conductance and capacitance under the DC limit approximation, it is helpful to examine the reliability of the results using the present modified theory and method under the Level 1, 2, and 3 approximations as follows. According to the results in Table TABLE II., it is found that (1) the membrane capacitances () based on the “slope and intercept” method (the existing theory under the DC limit) agree with those obtained using the present modify theory and optimization method, (2) the results obtained from both the ER and DEP experimental data agree each other, (3) the cell properties are of the same orders as those reported in the literature, and (4) the calculated peak and crossover frequencies using Eqs. 2, 5 based on the optimized cell dielectric parameters in the Level 1 calculation of Table TABLE II. agree with those of the measurements in Ref. 20, as shown in Table TABLE III.. The calculated peak and crossover frequency values are 9%–37% and 1%–13%, respectively, greater than those of the experimental values, which are within or of the same order as the experimental uncertainty. Thus, it is of certain confidence to interpret the cell dielectric properties using the results based on the present modify theory and method. However, the optimization method of the present theory is limited by both the quantity and quality of the experimental data. It works better if more experimental data are involved in the calculation. As the experimental uncertainty is substantial (could be of order of 30%) for the DEP crossover and peak ER experiments, more attention should be paid for the accuracy of the measurements for extracting cell properties in comparison with those solely for determining the criteria for particle separation. On designing an experiment for studying the dielectric properties of mammalian cells, it is suggested that several measurements (at least 5 sets of data) should be performed with medium conductivity less than 1 mS/m, so that the membrane capacitance and conductance can be determined easily using the slope and intercept of the straight line fitting of the data. With the membrane capacitance and conductance known, it is more easy and accurate to determine the dielectric properties of cell’s interior using the optimization method under the Level 2 or 1 assumption.

TABLE III.

Comparison between the calculated peak ( ) and crossover ( ) angular frequencies based on the optimized parameters in the Level 1 calculation in Table TABLE II. and the corresponding experimental values ( ) in Ref. 20. NA stands for “not applied.” The medium conductivity σ1 and all the angular frequencies are in unit mS/m and MHz, respectively.

| σ1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.5 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 1.17 | NA | NA | NA |

| 21.7 | 0.70 | 0.93 | 1.33 | NA | NA | NA |

| 32.8 | 1.16 | 1.40 | 1.21 | NA | NA | NA |

| 42.5 | 1.53 | 1.83 | 1.20 | NA | NA | NA |

| 48.7 | 2.01 | 2.20 | 1.09 | 1.30 | 1.33 | 1.02 |

| 60.3 | 2.20 | 2.69 | 1.22 | 1.46 | 1.65 | 1.13 |

| 74.9 | 2.62 | 3.41 | 1.30 | 2.01 | 2.04 | 1.02 |

| 86.9 | 3.17 | 4.13 | 1.30 | 2.36 | 2.37 | 1.01 |

| 101.4 | 3.62 | 4.96 | 1.37 | 2.68 | 2.77 | 1.03 |

CONCLUSION

A modified theory is proposed for extracting the cell dielectric properties from either measurement of electrorotation peak frequency or the DEP crossover frequency made as a function of the conductivity of the cell suspending medium. This modified theory differs from the current theory in the literature in that it may be applied for the situation where the low frequency (DC) approximation for the equivalent cell permittivity and conductivity is not appropriate, and it can also be employed to extract both the cell interior and membrane properties. The present theory can predict consistent results for both electrorotation and DEP measurements performed at relatively high medium conductivities of the order 100 mS/m and greater. In fact, it can be employed to extract cell dielectric properties from the measurements of either the low or the high electrorotation peak (or DEP crossover) frequency at any medium conductivity, provided the electrorotation peak (or DEP crossover) frequency exists in that medium. The modified theory reduces to the same form of the current linear theory under the DC limit approximation in the literature when the medium conductivity is less than 10 mS/m. According to the linear theory, the cell membrane capacitance can be obtained from the slope of the straight line fitting of either the electrorotation peak frequency or the DEP crossover frequency as a function of the conductivity of the cell suspending medium. However, the cell membrane conductance can be determined from the intercept of the straight line only when the intercept value is sufficiently greater than the experimental uncertainty, which occurs when the medium conductivity is reduced to the order of 1 mS/m. On the other hand, the cell membrane conductance can be adequately evaluated under the linear theory using the optimization calculation from the DEP crossover frequency measurement in a medium with conductivity between 48.7 and 101.4 mS/m.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work is supported partially by the National Science Council through the grant NSC 99-2221-E-002-082-MY3 of Taiwan, Republic of China.

References

- Gascoyne P. R. C. and Vykoukal J., Electrophoresis 23, 1973 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. P., Electrophoresis 23, 2569 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng I.-F., Chang H.-C., Hou D., and Chang H.-C., Biomicrofluidics 1, 021503 (2007). 10.1063/1.2723669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold W. M. and Zimmermann U., J. Electrost. 21, 151 (1988). 10.1016/0304-3886(88)90027-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., Menachery A., Pells S., and De Sousa Paul, J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 182581 (2010). 10.1155/2010/182581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C.-C., Cheng I.-F., Yang W.-H., and Chang H.-C., Biomicrofluidics 5, 021102 (2011). 10.1063/1.3600650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J. E., Gagnon Z., and Chang H.-C., Biomicrofluidics 1, 044102 (2007). 10.1063/1.2818767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon Z., Mazur J., and Chang H.-C., Biomicrofluidics 3, 044108 (2009). 10.1063/1.3257857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-B., Huang Y., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R. C., J. Phys. D 27, 1571 (1994). 10.1088/0022-3727/27/7/036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C. Y. and Lei U., J. Appl. Phys. 102, 094702 (2007). 10.1063/1.2802185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y. J. and Lei U., Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 253701 (2009). 10.1063/1.3277157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lei U. and Lo Y. J., IET Proc. Nanobiotechnol. 5, 86 (2011). 10.1049/iet-nbt.2011.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl H. A., Dielectrophoresis (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1978). [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. B., Electromechanics of Particles (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H. and Green N. G., AC Electrokinetics: Colloids and Nanoparticles (Research Studies, London, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M. P., Nanoelectromechanics in Engineering and Biology (CRC, Boca Raton, Florida, 2003). [Google Scholar]

- Chang H.-C. and Yeo L. Y., Electrokinetically Driven Microfluidics and Nanofluidics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., Biomicrofluidics 4, 022811 (2010). 10.1063/1.3456626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Wang X.-B., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R. C., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1282, 76 (1996). 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00047-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., Jakubek L. M., Sanger R. H., Heart E., Corson E. D., and Smith P. J. S., IEE Proc. Nanobiotechnol. 152, 189 (2005). 10.1049/ip-nbt:20050040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan H. P., Adv. Biol. Med. Phys. 5, 147 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Becker F. F., and Gascoyne P. R. C., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1564, 412 (2002). 10.1016/S0005-2736(02)00495-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeed F. H., Coley H. M., and Hughes M. P., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1760, 922 (2006). 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R. and Talary M. S., IET Proc. Nanobiotechnol. 1, 2 (2007). 10.1049/iet-nbt:20060018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-B., Huang Y., Gascoyne P. R. C., Becker F. F., Hölzel R, and Pethig R., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1193, 330 (1994). 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90170-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., Bressler V., Carswell-Crumpton C., Chen Y., Foster-Haje L., García-Ojeda M. E., Lee R. S., Lock G. M., Talary M. S., and Tate K. M., Electrophoresis 23, 2057 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C., Waterfall M., Pells S., Menachery A., Smith S., and Pethig R., J. Electr. Bioimp. 2, 64 (2011). 10.5617/jeb.196 [DOI]

- Gimsa J., Müller T., Schnelle T., and Fuhr G., Biophys. J. 71, 495 (1996). 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79251-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R. S., Chang H.-C., and Revzin A., Biomicrofluidics 5, 032005 (2011). 10.1063/1.3608135.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]