Abstract

For decades, the peopling of the Americas has been explored through the analysis of uniparentally inherited genetic systems in Native American populations and the comparison of these genetic data with current linguistic groupings. In northern North America, two language families predominate: Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dene. Although the genetic evidence from nuclear and mtDNA loci suggest that speakers of these language families share a distinct biological origin, this model has not been examined using data from paternally inherited Y chromosomes. To test this hypothesis and elucidate the migration histories of Eskimoan- and Athapaskan-speaking populations, we analyzed Y-chromosomal data from Inuvialuit, Gwich’in, and Tłįchǫ populations living in the Northwest Territories of Canada. Over 100 biallelic markers and 19 chromosome short tandem repeats (STRs) were genotyped to produce a high-resolution dataset of Y chromosomes from these groups. Among these markers is an SNP discovered in the Inuvialuit that differentiates them from other Aboriginal and Native American populations. The data suggest that Canadian Eskimoan- and Athapaskan-speaking populations are genetically distinct from one another and that the formation of these groups was the result of two population expansions that occurred after the initial movement of people into the Americas. In addition, the population history of Athapaskan speakers is complex, with the Tłįchǫ being distinct from other Athapaskan groups. The high-resolution biallelic data also make clear that Y-chromosomal diversity among the first Native Americans was greater than previously recognized.

Keywords: haplogroup, haplotype, Arctic, Inuit, Thule

The peopling of the Americas is a question of fundamental importance in anthropological and historical disciplines (1, 2). Much research on the issue has focused on testing the hypothesis that several separate migrations entered the New World, with each migration being associated with different linguistic, dental, and presumably, genetic characteristics (3). Under this model, Amerind is the largest, most varied, and oldest language family in the Americas. However, some have questioned the use and/or appropriateness of this linguistic classification (4, 5). Despite this controversy, the designation of the Na-Dene and Eskimo-Aleut language families is well-established, although the inclusion of Haida with Athapaskan, Eyak, and Tlingit (forming the Na-Dene family) has been reconsidered (6, 7).

In addition, there has been debate concerning the validity (or strict separation/genetic differentiation) between speakers of Athapaskan and Eskimo-Aleut languages. It has been argued based on blood group markers and cranial trait data that some Inuit are more closely related to non-Inuit groups and that certain Athapaskan-speaking populations have greater genetic affinity with non-Athapaskan groups (8, 9). Complete correlations between genetics and linguistic classifications are lacking from mtDNA data (5). Even the dental traits used to justify a three-migration hypothesis did not group all Na-Dene speakers into a single category separate from the other two (Amerind and Eskimo-Aleut) groups and furthermore, suggested the inclusion of Aleuts with Athapaskan speakers from northwestern America (3). Thus, although it is generally accepted that the two language families differ from each other, it is not clear whether they have different genetic origins or instead, are the result of separate migrations from the same source.

Not surprisingly, the number and timing of migrations into the Americas are still vigorously debated (10). Previous work focused mostly on mtDNA variation in northern Native American populations (2, 5, 10–15). Work using the Y chromosome to explore these issues, however, used relatively low-resolution haplogroup and haplotype data or did not test the correlation between Y-chromosomal diversity and language use (Athapaskan vs. Eskimoan) in a localized geographic space (16, 17). Here, we rectify this issue by generating the highest resolution nonrecombining region of the Y-chromosome (NRY) dataset to date for the Americas and analyzing populations that fill a major geographic gap between the previously studied Alaskan Inupiat and Greenlandic Inuit.

We characterized the NRY in Athapaskan [Gwich’in (Kutchin) and Tłįchǫ (Dogrib)] and Inuvialuktun (Inuvialuit) speakers from the Canadian Northwest Territories. This analysis led to the more precise identification of indigenous haplogroups and a better understanding of the extent of recent European admixture. In addition, by generating highly resolved Y-chromosome lineages, we were able to confirm the phylogeny of haplogroup Q, providing a detailed basis for future work. We also assessed whether Athapaskan and Eskimoan speakers derived from separate migrations (i.e., whether their genetic variation was structured by language) and examined the relationships of populations within and among these linguistic groups. In doing this assessment, we have expanded our understanding of the migration histories of Aboriginal [the term aboriginal describes indigenous populations in Canada, including First Nations (Indians), Inuit, and Métis] populations from northern North America.

Results

Haplogroup Q Phylogeny.

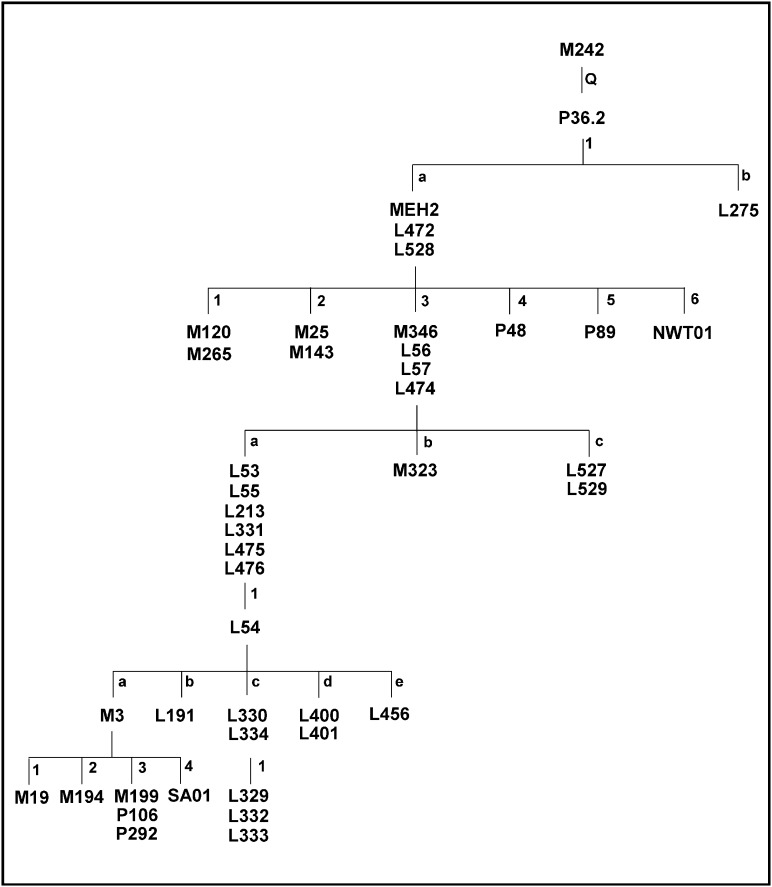

The structure of the haplogroup Q phylogeny is essentially the same as presented in the work by Dulik et al. (18), but it is enhanced for Native American and Aboriginal Y chromosomes (Fig. 1 and Table S1). The relative position of the Q1a3 branch was verified. A single Chumash haplotype possessed the four markers defining Q1a3 but lacked all nine markers defining Q1a3a, Q1a3b, and Q1a3c. Q1a3a remains defined as described in the work by Dulik et al. (18). Five of the Aboriginal participants had the L54 marker, which defines Q1a3a1*, but lacked any additional derived markers, including the Native American-specific M3. The remaining samples from this branch had the M3 marker but none of the four derived markers common in South America (19, 20).

Fig. 1.

A revised phylogeny of Y-chromosome haplogroup Q.

A number of haplogroup Q Y chromosomes did not belong to the Q1a3 branch. Most of these chromosomes had markers defining Q1a but lacked those markers that define Q1a1, Q1a2, Q1a3, Q1a4, and Q1a5. M323, which formerly defined Q1a6 (19), is now positioned as a derived mutation in relation to M346 (21). A marker detected in this analysis, called NWT01, differentiated almost one-half of the Inuvialuit Y chromosomes from all others. We have classified these Y chromosomes as belonging to haplogroup Q1a6. In addition to this haplogroup, two samples had the P89 marker, which defines haplogroup Q1a5. Thus, three of six known Q1a branches are found in the Americas (Q1a3, Q1a5, and Q1a6).

NRY Haplogroup Variation.

We observed significant differences in NRY haplogroup frequencies among the three Aboriginal groups from northern Canada (Table 1 and Table S1). All populations had high to moderate frequencies of Q1a3a1a*. The Athapaskan-speaking Gwich’in and Tłįchǫ had higher frequencies of C3b than the Inuvialuit, whereas the Inuvialuit had significantly more Q1a6 lineages. Additional haplogroups that seem to be indigenous in origin were found at low frequencies in the Athapaskan groups. Four samples (three Gwich’in and one First Nation member from British Columbia) belonged to paragroup Q1a3a1*. We also identified 10 samples (9 Athapaskans and 1 Inupiat samples) (22) that clustered with these haplotypes, suggesting a common origin for them. Another Q1a3a1* lineage belonged to a Mi’kmaq from Nova Scotia, but it is not clear that this person’s Y chromosome also shares a recent origin with these other haplotypes. Finally, one Tłįchǫ and one Slave belonged to Q1a5, whereas a similar Y-chromosome short tandem repeat (Y-STR) haplotype was found in one Alaskan Athapaskan (22). This SNP was previously described in the work by Karafet et al. (19), although its geographic distribution was not discussed.

Table 1.

NRY haplogroup frequencies for northern North American populations

| Gwich’in | Tłįchǫ | Inuvialuit | Inupiat | Other | |

| C3b | 8 | 13 | 1 | 2 | |

| E1b1b1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| H1a | 1 | ||||

| I1 (xI1a, I1b1, I1c, I1d1) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| J1c3 | 1 | ||||

| J2a | 1 | ||||

| J2b | 1 | ||||

| N1c1 | 2 | ||||

| Q1a3a1* | 3 | 1 | |||

| Q1a3a1a* | 6 | 15 | 6 | 2 | |

| Q1a5 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Q1a6 | 1 | 25 | 3 | ||

| R1a1a1* | 1 | 1 | |||

| R1b1a2 | 13 | 3 | 18 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 33 | 37 | 56 | 5 | 10 |

Asterisks indicate paragroups.

Earlier studies of Aboriginal and Native American Y chromosomes struggled to identify the number of indigenous founder haplogroups from those haplogroups that recently came from European and African sources (16, 23–26). Based on our examination of genealogical information and high-resolution genotypes, we were able to distinguish between these sources; 48% of the Gwich’in and 43% of the Inuvialuit Y chromosomes were more typically found in Europeans. By contrast, only 19% of the Tłįchǫ lineages were nonindigenous. Comparisons of these data with data from worldwide populations (www.yhrd.org) showed exact or near matches between the haplotypes of nonindigenous lineages and those haplotypes of Europeans. Hence, although these men are Aboriginal, some of their genetic ancestry traces back to Europe.

NRY Phylogeography.

Because variation accumulates with time, a relative chronology can be constructed by assessing haplogroup STR diversity, ρ, and mean pairwise differences (Table 2 and Table S2). We noted that Q1a Y chromosomes had far greater diversity than C3 Y chromosomes, and within Q1a, those chromosomes with M3 (Q1a3a1a*) had the greatest amount. The Q1a3a1a* network exhibited only one definitive haplotype cluster, which was composed entirely of Athapaskan-speakers (mostly Tłįchǫ) and distinctive in having a duplication of the DYS448 locus (Fig. S1). All other Q1a3a1a* lineages were dispersed among longer branches of the network, indicating that they derived from a common source much farther in the past. Tłįchǫ Q1a3a1a* showed the lowest intrapopulation variance (Vp) estimate, whereas values were higher in the Gwich’in and Inuvialuit. The low diversity of the Tłįchǫ is likely caused by a recent founder event. Interestingly, when comparisons were expanded to include populations from southeast Alaska, the Tlingit had far greater diversity within this haplogroup, possibly as a result of their geographic location and increased interaction with other Native Americans (27).

Table 2.

Diversity estimates of major NRY haplogroups

| Haplogroup | Population | N | h | Haplotype diversity | MPD | ρ ± σ | Vp |

| C3b | 44 | 23 | 0.944 ± 0.018 | 2.641 ± 1.437 | 2.03 ± 0.66 | 0.115 | |

| C3b | Gwich’in | 8 | 5 | 0.786 ± 0.151 | 1.607 ± 1.060 | 1.38 ± 0.80 | 0.061 |

| C3b | Tłįchǫ | 13 | 5 | 0.782 ± 0.079 | 1.872 ± 1.143 | 1.50 ± 0.78 | 0.073 |

| C3b | Athapaskan (inferred) | 13 | 10 | 0.962 ± 0.041 | 3.282 ± 1.805 | 2.38 ± 0.80 | 0.150 |

| Q1a (including Q1a3, Q1a5, and Q1a6) | 81 | 52 | 0.979 ± 0.007 | 6.347 ± 3.040 | 9.57 ± 1.52 | 0.625 | |

| Q1a6 | 123 | 41 | 0.951 ± 0.008 | 2.478 ± 1.348 | 1.67 ± 0.38 | 0.130 | |

| Q1a6 | Inuvialuit | 20 | 10 | 0.916 ± 0.034 | 1.737 ± 1.054 | 1.20 ± 0.52 | 0.080 |

| Q1a6 | Inupiat (inferred) | 60 | 19 | 0.901 ± 0.019 | 1.918 ± 1.107 | 1.43 ± 0.51 | 0.034 |

| Q1a6 | Yupik (inferred) | 33 | 17 | 0.945 ± 0.020 | 3.218 ± 0.126 | 2.38 ± 0.67 | 0.093 |

| Q1a3a1a* | M3-positive | 41 | 28 | 0.959 ± 0.019 | 5.328 ± 2.625 | 5.44 ± 0.98 | 0.376 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Tłįchǫ | 15 | 8 | 0.848 ± 0.071 | 1.438 ± 0.927 | 0.87 ± 0.39 | 0.056 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Gwich’in | 6 | 3 | 0.600 ± 0.215 | 3.867 ± 2.256 | 2.33 ± 0.85 | 0.129 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Inuvialuit | 4 | 3 | 0.833 ± 0.222 | 5.000 ± 3.068 | 2.75 ± 0.90 | 0.183 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Tlingit | 7 | 7 | 1.000 ± 0.076 | 5.524 ± 3.022 | 4.00 ± 0.95 | 0.356 |

| Q1a3a1a* | M3-positive + inferred | 199 | 116 | 0.989 ± 0.002 | 6.433 ± 3.059 | 7.93 ± 1.27 | 0.406 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Athapaskan (M3-inferred) | 31 | 21 | 0.974 ± 0.014 | 5.978 ± 2.930 | 5.87 ± 1.02 | 0.397 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Inupiat (M3-inferred) | 46 | 30 | 0.971 ± 0.013 | 6.041 ± 2.930 | 5.13 ± 0.92 | 0.049 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Yupik (M3-inferred) | 81 | 51 | 0.979 ± 0.006 | 6.591 ± 3.146 | 7.63 ± 1.48 | 0.368 |

h, number of haplotypes; MPD, mean pairwise differences; N, number of samples; ρ, average distance from root haplotype; σ, SE for ρ; Vp, intrapopulation genetic variance. Asterisks indicate paragroups.

Haplogroups Q1a6 and C3b had roughly one-third of the diversity of Q1a3a1a*, suggesting that they arose more recently and at approximately the same time. The majority of Y chromosomes for each of these haplogroups belonged to single haplotype clusters, suggesting that they likely originated from two different ancestors relatively recently (one for each haplogroup). Q1a6 is especially important, because it is largely confined to the Inuvialuit, Inuit, and Inupiat populations. Although no SNP data were presented in the work by Davis et al. (22), a number of their STR haplotypes were similar to the Q1a6 lineages and in several cases, shared with the Inuvialuit (Fig. S2). Furthermore, Q1a6 may also be present in Greenlandic Inuit and Aleuts, although these populations were characterized with fewer STRs. Diversity estimates indicated the greatest assortment of haplotypes in the Yupik and less assortment in Inupiat and Inuvialuit. This trend of slightly decreasing values from west to east suggests an origin for Q1a6 in the westernmost Arctic and its dispersal through an eastward expansion.

Haplogroup C3b was found at comparatively high frequencies in Athapaskan populations. The Tłįchǫ and Gwich’in C3b lineages were similar to one another, forming a single large cluster (Fig. S3). We reduced our NRY data to 8-STR loci haplotypes to compare them with published data (17, 22, 28) and determine the directionality of movement by bearers of C3b Y chromosomes. Vp estimates for the 8-STR haplotypes showed the greatest diversity in the Tanana Athapaskans and Alaskan Athapaskans of the work by Davis et al. (22), moderate values among the Tłįchǫ and Gwich’in, and the lowest values in the Apache, thus forming a north to south gradient of C3b diversity.

The evolutionary mutation rate (29) was used to calculate times to most recent common ancestor (TMRCAs), because previous estimates using the pedigree-based mutation rate gave values that were too recent and conflicted with nongenetic data (18). In most cases, the estimates from Batwing were greater than those estimates from Network—a difference previously noted (30, 31). Unlike ρ-estimates, the estimates generated with Batwing are useful only when the demographic model that is used is appropriate for the sample set. In this case, the model involves a population at a constant size that expands exponentially at time β. Although generally useful, the 95% confidence intervals of Batwing estimates show that the TMRCAs are not precise. In addition, if the root haplotypes were incorrectly inferred for the ρ-statistics, then the TMRCAs could be skewed (31, 32). Regardless, the relative chronology of these haplogroups should not be affected.

The TMRCAs for M3-derived Y chromosomes indicated a coalescent event between 13,000 and 22,000 y ago (Table 3). TMRCAs from each population were substantially more recent, although the dates mirror the diversity estimates in showing the varied collection of Q1a3a1a* haplotypes in each population. The TMRCAs for Q1a6 and C3b were comparable. For Q1a6, the TMRCA was between 4,000 and 7,000 y ago. The overall TMRCA estimate of the C3b lineages was 5,000 y ago with ρ-statistics and about two times that value with Batwing. Similar estimates were calculated for each of the ethnic groups, with a range between 4,000 and 6,000 y ago; Alaskan Athapaskans had greater diversity and an older TMRCA.

Table 3.

TMRCAs of major NRY haplogroups

| Haplogroup | Population | N | ρ-Statistic TMCRA (y ago) | ρ-Statistic SE | Batwing TMCRA (y ago) | Batwing 95% confidence interval |

| C3b | 44 | 4,900 | ± 1,590 | 10,590 | 3,860–37,550 | |

| C3b | Gwich’in | 8 | 3,320 | ± 1,930 | 5,920 | 1,470–30,350 |

| C3b | Tłįchǫ | 13 | 3,620 | ± 1,880 | 5,370 | 1,390–29,680 |

| C3b | Athapaskan (inferred) | 13 | 5,760 | ± 1,920 | 7,890 | 2,670–26,070 |

| Q1a6 | 123 | 4,030 | ± 920 | 7,220 | 2,810–21,190 | |

| Q1a6 | Inuvialuit | 20 | 2,900 | ± 1,430 | 5,720 | 1,630–29,780 |

| Q1a6 | Inupiat (inferred) | 60 | 3,460 | ± 1,230 | 7,160 | 2,510–27,310 |

| Q1a6 | Yupik (inferred) | 33 | 5,740 | ± 1,620 | 7,780 | 2,360–33,330 |

| Q1a3a1a* | M3-positive | 41 | 13,140 | ± 2,370 | 22,010 | 7,780–83,170 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Tłįchǫ | 15 | 2,090 | ± 950 | 4,770 | 1,260–25,280 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Gwich’in | 6 | 5,640 | ± 2,050 | 11,640 | 3,120–54,540 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Inuvialuit | 4 | 6,640 | ± 2,180 | 9,790 | 2,610–49,200 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Tlingit | 7 | 9,660 | ± 2,290 | 22,280 | 6,210–110,720 |

| Q1a3a1a* | M3-positive + -inferred | 199 | 19,160 | ± 3,070 | 30,000 | 13,530–76,060 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Athapaskan (M3-inferred) | 31 | 14,180 | ± 2,470 | 22,290 | 8,820–81,580 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Inupiat (M3-inferred) | 46 | 12,390 | ± 2,220 | 27,280 | 9,940–95,530 |

| Q1a3a1a* | Yupik (M3-inferred) | 81 | 18,430 | ± 3,570 | 17,260 | 5,870–68,570 |

Asterisks indicate paragroups.

Population Comparisons.

To make intrapopulation comparisons of Y-chromosome variation, we estimated genetic distances (RST values) from the Y-STR (15 loci) haplotypes and visualized them through a multidimensional scaling plot (Fig. 2 and Table S3). The Athapaskan-speaking populations of the Northwest Territories and Alaska appeared on the right side of the plot, whereas the Eskimoan-speaking populations were positioned to the left. Without exception, the Athapaskan and Eskimoan speakers were significantly different from each other. The Inuvialuit and Inupiat were not significantly different from each other, but the Yupik were from all other populations. Similar patterns of genetic differentiation were also observed for the Athapaskan speakers, where all except the Tłįchǫ were not significantly different from one another. However, when RST values were calculated with only lineages of indigenous origin, the Tłįchǫ were not significantly different from the Gwich’in.

Fig. 2.

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot of RST values estimated from Y-STR haplotypes among northern North American populations. The dotted circles enclose populations that share insignificant genetic distances.

An analysis of molecular variance was conducted to assess whether geography or linguistic affiliation was a better predictor of genetic variation. Using three geographic groups to cluster the data, we noted that the variation among groups was not significant, and among population within-group variation was high (Table S4). When the data were clustered by linguistic affiliation, the among group variation rose to 12%, whereas the among population within-group value fell to about 2.4%. This finding suggested that their paternal genetic history is structured along linguistic instead of geographic lines.

Discussion

Much of the genetic research on northern Aboriginal populations has centered on the origins of Inuit peoples, particularly from Greenland, and the possible contributions of historic European (Norse) populations to their genetic makeup. This study has examined Y-chromosome diversity in the Inuvialuit to better understand the origin of their Aboriginal lineages. We accomplished this task effectively by using high-resolution haplotypes. In addition, the samples came from populations living in a region not previously well-described, thus filling a significant geographic void in genetic information about northern Aboriginal history.

From an mtDNA perspective, Inuit populations around the Arctic seemed similar to one another, with low levels of genetic diversity (13–15). The general model for Inuit origins proposes a discontinuity between the earliest inhabitants of Greenland (Paleo-Eskimo) and later (Dorset and Thule) cultures (13, 14, 33). Debate continues as to whether Inuit are wholly descended from Thule tribes that migrated across the Arctic about 1,000 y ago (14) or whether modern Inuit formed out of interactions between the previous Dorset inhabitants and later Thule migrants (13). A complete ancient Paleo-Eskimo mitogenome was sequenced to test these models (33). The sample belonged to haplogroup D2a1, which does not appear in modern Inuit populations and is most similar to Aleut and Siberian Yupik D2a1a mitogenomes (15, 33–35), suggesting a genetic discontinuity between ancient and modern Inuit populations.

From an NRY perspective, many Eskimoan Y chromosomes belonged to Q1a6, which has a TMRCA that predates the Paleo-Eskimo material culture. The Y chromosome of the ancient Paleo-Eskimo man was assigned to paragroup Q1a*, but the NWT01 locus was not sequenced (36). Assignment of the Paleo-Eskimo Y chromosome to Q1a6 does not conflict with these data or the TMRCA of Q1a6. Furthermore, autosomal analysis of the ancient Paleo-Eskimo genome suggested that this man had close affinities with the Nganasan, Koryak, and Chukchi of northeastern Siberia. In fact, four Koryaks also have Q1a* Y chromosomes (37), with the number of repeat differences being within the typical range of confirmed Q1a6 haplotypes. Thus, although a discontinuity in mtDNAs between the Paleo-Eskimo and modern Inuit has been shown, this finding may not be the case for Y chromosomes.

Our Q1a6 TMRCAs were comparable with the estimate that the work by Rasmussen et al. (36) calculated from genomic SNP data for a migration from Siberia to the Americas. Although the work by Rasmussen et al. (36) inferred a Siberian origin for this migration, an origin in northwestern North America with a subsequent back migration across the Bering Strait is equally likely (as seen with M3) (38), given that Q1a6 is found at higher frequencies and with greater diversity in Eskimoan speakers. In addition, NRY lineages common to coastal Siberian populations (i.e., C3c and N1c) were not present in American Arctic groups.

In addition to identifying this Eskimo-Aleut haplogroup, we also noted significant genetic differences between Inuvialuit and Athapaskan speakers. Previous mtDNA studies found haplotype sharing between Inuit and Athapaskan speakers (12, 14). This finding was evident from the high frequency of A2 mtDNAs in both linguistic groups and reduced genetic diversity relative to populations to the south—possibly caused by more recent reexpansions from Beringia or northwestern North America (12). In contrast, their Y-chromosome diversity was structured by language affiliation, which suggested that the distribution of genes and language are consistent with at least two migratory events. It is especially convincing given that some number of Inuvialuit and Gwich’in live in the same communities (Aklavik and Inuvik). Furthermore, within the Eskimoan-speaking populations, the Inuvialuit and Inupiat (Inuit speakers) and Yupik (Yupik speakers) have genetically diverged from each other.

However, the data for Na-Dene-speaking populations did not show the same correspondence between populations and language. The Tlingit, who speak the most divergent language of those languages in the Athapaskan-Eyak-Tlingit linguistic family (7, 39), are not significantly different from the Gwich’in and Athapaskan Indians from Central Alaska. Because the Tłįchǫ speak an Athapaskan language closer to the language of the Gwich’in, we expected that the Tłįchǫ and Gwich’in would be more similar to one another than to the Tlingit. However, the Tłįchǫ were genetically distinct from other Athapaskan speakers, possibly because of their lower levels of European admixture. This finding, however, does not explain the small genetic distance between Tlingit and Gwich’in and may indicate that the Tlingit sample is too small and unrepresentative to allow for a complete comparison. The genetic differences between these Aboriginal groups do suggest that the spread of Inuit culture across the Arctic was not simply a cultural phenomenon and that Athapaskan Indians living in the interior were not differentiated by their cultural adaptations to local environments alone (at least from a strictly paternal genetic perspective).

Previous studies using Y-chromosomal data have not conclusively determined whether the Americas were peopled by a single migration event or multiple migrations (23–25, 28, 40). Initial data from STRs, Y-chromosome centromeric heteroduplexes, and surveys of the M3 marker suggested a single migratory event (41–45). The presence of haplogroup C in the Americas has been cited as evidence for a second migration and has also been used as evidence of a separate homeland for Native American progenitors (23, 24). Our data are most consistent with the model in the work by Forster et al. (12) that proposes a single migration into the Americas followed by a second subsequent expanding wave. The first wave was associated with the initial peopling of the Americas through Beringia, and the founding populations were likely composed of Q-MEH2 (xL54), Q-L54, and C-M217 Y chromosomes. Other Y chromosomes were likely present in the founding population at low frequencies but subsequently lost over time.

Q-L54 is unmistakably a founding haplogroup and provides a clear connection to southern Siberia, where L54 is also found (18). The designation of Q-L54 as a major founding haplogroup is also supported by the presence of Q-L54 (xM3) Y chromosomes in our sample set. However, the geographic distribution of this paragroup is not yet clear. By contrast, Q-M3 arose (either in Beringia or Alaska) from a Q-L54 founder and has been shown to be ubiquitous and diverse in most indigenous populations, pointing to its primacy in the first expansions of men throughout the Americas.

Furthermore, a handful of C-M217 Y chromosomes without the P39 marker were found in southeast Alaska and Colombia, South America (23, 27, 46, 47). The spread of C-P39 involved mostly Athapaskan speakers and was associated with a second wave of expansion, which is the same as Q1a6 for Eskimoan speakers. These second wave expansions likely originated from American sources that amalgamated with the first wave inhabitants as they spread throughout the north. Because of the imprecision of TMRCA estimates, it is not possible to determine whether haplogroup C3b originated before Q1a6 or vice versa.

The disparities in language, culture, and Y-chromosome diversity between Athapaskan- and Eskimoan-speaking populations likely reflect the effects of demic expansions after the initial migratory event that brought human groups to the Americas. This second wave likely occurred roughly in parallel, resulting in different migration and population histories, and contributed to the genetic makeup of extant Aboriginal populations of North America. We should emphasize that we are referring to the populations themselves and not the languages that they speak. We can only say that speakers of these two language families have comparatively recent paternal histories. This analysis has allowed us to develop a more detailed picture of the paternal genetic history of Aboriginal and Native Americans, and it shows that the diversity of the founding indigenous American populations was greater than previously acknowledged.

Methods

Buccal cells and genealogical data were obtained with informed consent from participants residing in 12 settlements during two expeditions to the Northwest Territories in 2009 and 2010 (Fig. S4). Data and sample collections were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board, the Aurora Research Institute, the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, the Gwich’in First Nation, and the Tłįchǫ Government. DNA samples were extracted using QIAamp DNA Mini kits (Qiagen) using the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications (SI Methods). Samples were characterized using published methods (48, 49). An SNP was discovered using the primers originally designated for Q4 in the work by Sengupta et al. (32). This SNP, named NWT01, is a C to G transversion at np 65 in the amplicon (Y position 2,888,083 in Build 37.2).

Comparative data came from published literature (Table S2) (22, 27, 48–50). Statistical analysis included estimates of haplotype diversity, mean pairwise differences and analysis of molecular variance using Arlequin v3.11 (51), and Vp estimates assessed as in the work by Kayser et al. (52). Genetic distances (RST values) were calculated using 15 Y-STR loci and visualized with a multidimensional scaling plot in SPSS v.11 (53). Reduced median–median joining networks and ρ-statistics were generated with Network v4.6.0.0 (www.fluxus-engineering.com) (54). TMRCAs were calculated as described elsewhere (SI Methods) (55).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gwich’in, Inuvialuit, Tłįchǫ, and other First Nations individuals from the Northwest Territories and Nunavut and Alaska Native individuals for their collaboration and participation. We also thank the Gwich’in First Nation, the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation, and the Tłįchǫ First Nation Government for their support of this research (SI Text). We thank Emöke Szathmary for her insightful remarks on the manuscript and Janet Ziegle and Applied Biosystems for providing technical assistance. Funding was provided by the National Geographic Society, IBM, the Waitt Family Foundation, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

2A complete list of The Genographic Consortium can be found in SI Text.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1118760109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fiedel SJ. The peopling of the New World: Present evidence, new theories, and future directions. J Archaeol Res. 2000;8:39–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schurr TG. The peopling of the New World: Perspectives from molecular anthropology. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2004;33:551–583. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg JH, Turner CG, II, Zegura SL. The settlement of the Americas: A comparison of the linguistic, dental, and genetic evidence. Curr Anthropol. 1986;27:477–497. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolnick DA, Shook BA, Campbell L, Goddard I. Problematic use of Greenberg’s linguistic classification of the Americas in studies of Native American genetic variation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:519–522. doi: 10.1086/423452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunley K, Long JC. Gene flow across linguistic boundaries in Native North American populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1312–1317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409301102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell L. American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krause ME, Golla V. Northern Athapaskan languages. In: Helm J, editor. Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution; 1981. pp. 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ousley SD. Relationships between Eskimos, Amerindians, and Aleuts: Old data, new perspectives. Hum Biol. 1995;67:427–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szathmary EJE, Ossenberg NS. Are the biological differences between North American Indians and Eskimos truly profound? Curr Anthropol. 1978;19:673–701. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Rourke DH, Raff JA. The human genetic history of the Americas: The final frontier. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R202–R207. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budowle B, et al. HVI and HVII mitochondrial DNA data in Apaches and Navajos. Int J Legal Med. 2002;116:212–215. doi: 10.1007/s00414-001-0283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster P, Harding R, Torroni A, Bandelt HJ. Origin and evolution of Native American mtDNA variation: A reappraisal. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:935–945. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helgason A, et al. mtDNA variation in Inuit populations of Greenland and Canada: Migration history and population structure. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2006;130:123–134. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saillard J, Forster P, Lynnerup N, Bandelt HJ, Nørby S. mtDNA variation among Greenland Eskimos: The edge of the Beringian expansion. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:718–726. doi: 10.1086/303038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Starikovskaya YB, Sukernik RI, Schurr TG, Kogelnik AM, Wallace DC. mtDNA diversity in Chukchi and Siberian Eskimos: Implications for the genetic history of Ancient Beringia and the peopling of the New World. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1473–1491. doi: 10.1086/302087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosch E, et al. High level of male-biased Scandinavian admixture in Greenlandic Inuit shown by Y-chromosomal analysis. Hum Genet. 2003;112:353–363. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0913-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malhi RS, et al. Distribution of Y chromosomes among native North Americans: A study of Athapaskan population history. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2008;137:412–424. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dulik MC, et al. Mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome variation provides evidence for a recent common ancestry between Native Americans and Indigenous Altaians. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:229–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karafet TM, et al. New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree. Genome Res. 2008;18:830–838. doi: 10.1101/gr.7172008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jota MS, et al. A new subhaplogroup of native American Y-Chromosomes from the Andes. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2011;146:553–559. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.International Society of Genetic Genealogy . ISOGG Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree 2011, Version 6.75. 2011. Available at http://isogg.org/tree/. Accessed September 23, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis C, et al. Y-STR loci diversity in native Alaskan populations. Int J Legal Med. 2011;125:559–563. doi: 10.1007/s00414-011-0568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karafet TM, et al. Ancestral Asian source(s) of new world Y-chromosome founder haplotypes. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:817–831. doi: 10.1086/302282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lell JT, et al. The dual origin and Siberian affinities of Native American Y chromosomes. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:192–206. doi: 10.1086/338457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarazona-Santos E, Santos FR. The peopling of the Americas: A second major migration? Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1377–1380. doi: 10.1086/340388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bortolini MC, et al. Y-chromosome evidence for differing ancient demographic histories in the Americas. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:524–539. doi: 10.1086/377588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schurr TG, et al. Genetic diversity in Haida and Tlingit populations from Southeast Alaska is shaped by clan, language and migration history. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zegura SL, Karafet TM, Zhivotovsky LA, Hammer MF. High-resolution SNPs and microsatellite haplotypes point to a single, recent entry of Native American Y chromosomes into the Americas. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:164–175. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhivotovsky LA, et al. The effective mutation rate at Y chromosome short tandem repeats, with application to human population-divergence time. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:50–61. doi: 10.1086/380911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirabal S, et al. Y-chromosome distribution within the geo-linguistic landscape of northwestern Russia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:1260–1273. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi W, et al. A worldwide survey of human male demographic history based on Y-SNP and Y-STR data from the HGDP-CEPH populations. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:385–393. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sengupta S, et al. Polarity and temporality of high-resolution y-chromosome distributions in India identify both indigenous and exogenous expansions and reveal minor genetic influence of Central Asian pastoralists. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:202–221. doi: 10.1086/499411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilbert MT, et al. Paleo-Eskimo mtDNA genome reveals matrilineal discontinuity in Greenland. Science. 2008;320:1787–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1159750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubicz R, Schurr TG, Babb PL, Crawford MH. Mitochondrial DNA variation and the origins of the Aleuts. Hum Biol. 2003;75:809–835. doi: 10.1353/hub.2004.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zlojutro M, et al. Genetic structure of the Aleuts and Circumpolar populations based on mitochondrial DNA sequences: A synthesis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2006;129:446–464. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rasmussen M, et al. Ancient human genome sequence of an extinct Palaeo-Eskimo. Nature. 2010;463:757–762. doi: 10.1038/nature08835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malyarchuk B, et al. Ancient links between Siberians and Native Americans revealed by subtyping the Y chromosome haplogroup Q1a. J Hum Genet. 2011;56:583–588. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karafet TM, et al. Y chromosome markers and Trans-Bering Strait dispersals. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;102:301–314. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199703)102:3<301::AID-AJPA1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenberg JH. The Na-Dene problem. In: Greenberg JH, editor. Languages in the Americas. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. pp. 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santos FR, et al. The central Siberian origin for native American Y chromosomes. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:619–628. doi: 10.1086/302242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pena SD, et al. A major founder Y-chromosome haplotype in Amerindians. Nat Genet. 1995;11:15–16. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santos FR, Pena SD, Tyler-Smith C. PCR haplotypes for the human Y chromosome based on alphoid satellite DNA variants and heteroduplex analysis. Gene. 1995;165:191–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00501-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos FR, Rodriguez-Delfin L, Pena SD, Moore J, Weiss KM. North and South Amerindians may have the same major founder Y chromosome haplotype. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:1369–1370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Underhill PA, Jin L, Zemans R, Oefner PJ, Cavalli-Sforza LL. A pre-Columbian Y chromosome-specific transition and its implications for human evolutionary history. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:196–200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bianchi NO, et al. Origin of Amerindian Y-chromosomes as inferred by the analysis of six polymorphic markers. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;102:79–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199701)102:1<79::AID-AJPA7>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergen AW, et al. An Asian-Native American paternal lineage identified by RPS4Y resequencing and by microsatellite haplotyping. Ann Hum Genet. 1999;63:63–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1999.6310063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geppert M, et al. Hierarchical Y-SNP assay to study the hidden diversity and phylogenetic relationship of native populations in South America. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2011;5:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.fsigen.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaieski JB, et al. Genetic ancestry and indigenous heritage in a Native American descendant community in Bermuda. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2011;146:392–405. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhadanov SI, et al. Genetic heritage and native identity of the Seaconke Wampanoag tribe of Massachusetts. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;142:579–589. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolnick DA, Bolnick DI, Smith DG. Asymmetric male and female genetic histories among Native Americans from Eastern North America. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:2161–2174. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin (version 3.0): An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol Bioinform Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kayser M, et al. An extensive analysis of Y-chromosomal microsatellite haplotypes in globally dispersed human populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:990–1018. doi: 10.1086/319510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.SPSS Inc . SPSS Inc. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bandelt HJ, Forster P, Röhl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xue Y, et al. Male demography in East Asia: A north-south contrast in human population expansion times. Genetics. 2006;172:2431–2439. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.