Abstract

Follicular T-helper (TFH) cells cooperate with GL7+CD95+ germinal center (GC) B cells to induce antibody maturation. Herein, we identify the transcription factor IRF4 as a T-cell intrinsic precondition for TFH cell differentiation and GC formation. After immunization with protein or infection with the protozoon Leishmania major, draining lymph nodes (LNs) of IFN-regulatory factor-4 (Irf4−/−) mice lacked GCs and GC B cells despite developing normal initial hyperplasia. GCs were also absent in Peyer’s patches of naive Irf4−/− mice. Accordingly, CD4+ T cells within the LNs and Peyer’s patches failed to express the TFH key transcription factor B-cell lymphoma-6 and other TFH-related molecules. During chronic leishmaniasis, the draining Irf4−/− LNs disappeared because of massive cell death. Adoptive transfer of WT CD4+ T cells or few L. major primed WT TFH cells reconstituted GC formation, GC B-cell differentiation, and LN cell survival. In support of a T-cell intrinsic IRF4 activity, Irf4−/− TFH cell differentiation was not rescued by close neighborhood to transferred WT TFH cells. Together with its known B lineage-specific roles during plasma cell maturation and class switch, our study places IRF4 in the center of antibody production toward T-cell–dependent antigens.

Keywords: interleukin-21, inducible costimulator, CXC-chemokine receptor 5, apoptosis

Apart from Th1 and Th2, the family of Th subsets now includes Th17 and Th9 (1). In addition, follicular T-helper (TFH) cells are defined based on their location within germinal center cells (GCs) of lymphoid organs (2, 3). Here, these cells produce cytokines that normally define other subsets, such as the Th2 product IL-4 (4, 5) or the Th17 product IL-21 (6), which is involved in GC B-cell generation (7–10). TFH cell propagation is supported by the transcription factor B-cell lymphoma (BCL)-6 and suppressed by Blimp1 (11–13). Further markers used to define TFH cells include inducible costimulator (ICOS), programmed death-1 (PD-1), and CXC-chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5), which mediate their migration into GCs (2, 14–16).

The IFN-regulatory factor (IRF) family of transcription factors includes nine members in mammals that bind to related target-gene sequences (17). We and others have described important roles of IRFs during Th cell differentiation. In particular, IRF1 is decisive for Th1 cell generation because it is ubiquitously expressed and redundantly addresses many genes with independent Th1-supporting function (17–19). In contrast, IRF4 controls Th2 and Th17 cell differentiation (20–23), with ensuing total resistance of Irf4−/− mice in a Th17-dependent mouse model of multiple sclerosis (24). In addition, regulatory T-cell (Treg)-specific IRF4 deficiency or lack of IRF4 binding protein lead to a generalized autoimmune syndrome (25, 26). Finally, we reported on the role of IRF4 during Th9 differentiation (27). Remarkably, IRF4 is also a B-cell intrinsic prerequisite for class switch and plasma cell maturation (28, 29).

Given these pleiotropic activities of IRF4 on B and T cells, we wondered whether IRF4 also contributes to the interaction of TFH and GC B cells. Herein, we use chronic leishmaniasis, a model infection with prominent T- and B-cell interactions (30) to prove a decisive T-cell intrinsic role of IRF4 for murine TFH cell development.

Results

Irf4−/− Mice Fail to Generate GCs.

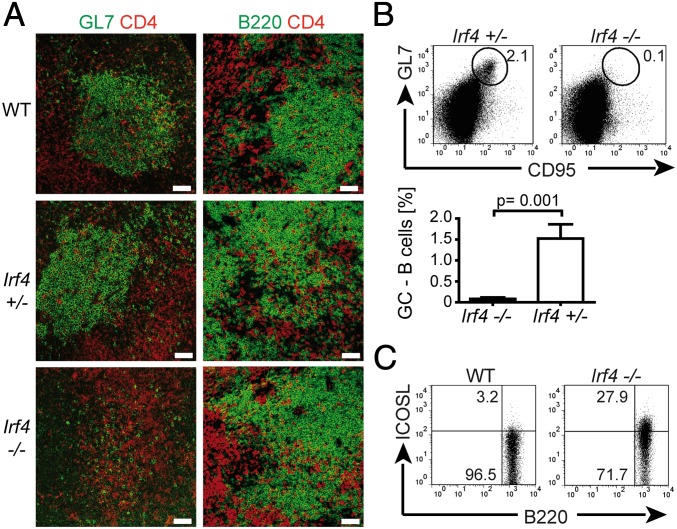

To study the development of TFH cells in vivo, we infected Irf4−/− mice and Irf4-competent control mice with Leishmania major (30). Two weeks later, draining popliteal lymph nodes (LNs) were analyzed (Figs. 1 and 2). By immunohistology, prominent GC formation was observed in WT and Irf4+/− LNs, including presence of GL7+ GC cells (Fig 1A). In contrast, GCs were totally absent in Irf4−/− LNs and few GL7+ cells were dispersed throughout the LN. However, Irf4−/− LNs did contain normal B and CD4 T-cell areas (Fig. 1A, Bottom Right). We confirmed the lack of GCs in Irf4−/− mice that were immunized with the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide instead of L. major infection (Fig. S1) and in Peyer’s patches (PP) from naive mice (Fig. 3A).

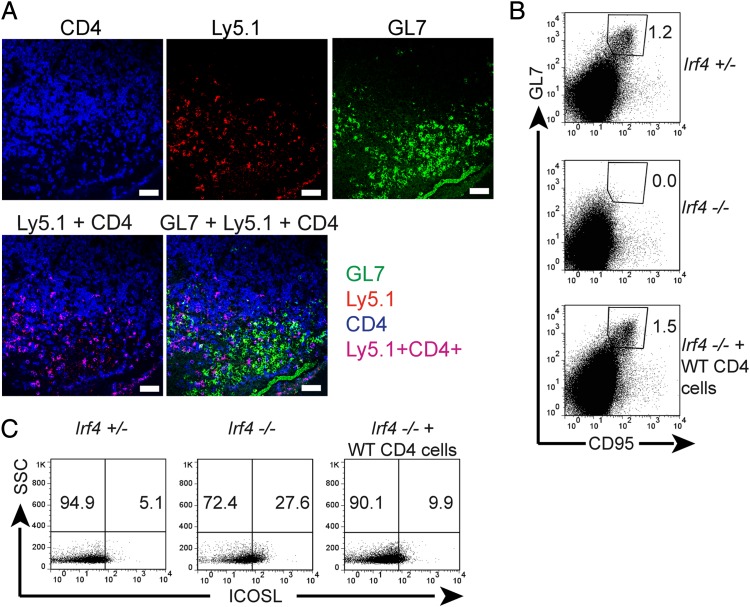

Fig. 1.

Lack of GC formation in Irf4−/− mice. Mice of the indicated genotypes were infected with L. major. Two weeks later, popliteal LNs were prepared. (A) Tissue sections were stained for CD4 (red), GL7 (green, Left), or B220 (green, Right), and analyzed by fluorescence-microscopy (20× magnification). (Scale bars, 50 μm.) (B and C) LN cell suspensions were stained for the indicated surface molecules and analyzed by flow cytometry. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells in the respective circles or rectangles. Panels are from one representative mouse per group. Three different experiments, each with two or three mice per group. (B) B220+ B-cell gate. Percentages (mean ± SD) of GL7+CD95+ B cells compiled from all mice tested.

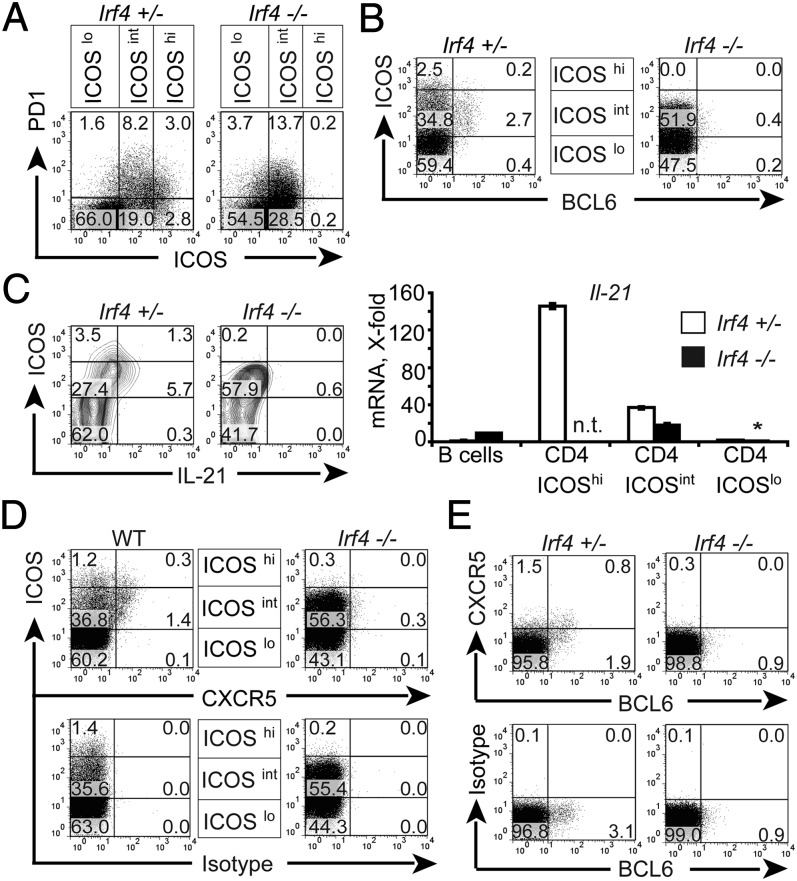

Fig. 2.

Lack of TFH cells in L. major infected Irf4−/− mice. Irf4−/−, WT mice, and Irf4+/− mice (three per group) were infected with L. major and their popliteal LN cells analyzed 2 wk later for expression of extracellular ICOS, CXCR5, and PD-1 (A) and intracellular BCL-6 (B) and IL-21 (C). (A; B; C, Right; D; and E) Direct ex vivo analysis. (C) Analysis after restimulation for 4 h with PMA and ionomycin (Left). (Right) CD4+ cells from pooled LN cells of all mice per group sorted according to ICOS expression (see A), and analyzed for IL-21 compared with HPRT (hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase) expression by RT qPCR. Bars denote the SD of duplicate qPCR determinations of each sample. The asterisk signifies that this value was set to one. n.t., not tested. (D and E) Single CD4+ cells were gated similar to gate B of Fig. S2B. Numbers in A–E indicate percentages of cells in the respective rectangles. Data are from one representative mouse per group. Three experiments with similar outcomes.

Fig. 3.

Lack of TFH cell differentiation in PP of naive Irf4−/− mice. (A–C) PP of naive mice were analyzed as described for Figs. 1 and 2.

A strong reduction in GC B cells coexpressing the markers GL7 and CD95 (31, 32) was verified by flow-cytometry of single LN cell suspensions from L. major infected Irf4−/− mice (Fig. 1B, note the compiled data of three different experiments). Again, the finding was reproduced in PP from naive mice (Fig. 3B). In control FACS-stainings, GL7 was only weakly expressed on WT and Irf4−/− CD4+ cells. Thus, Irf4−/− mice form the architecture of normal LNs, but lack GC formation. Furthermore, the ICOS ligand (ICOSL) molecule was strongly up-regulated on Irf4−/− B compared with WT B cells (Fig. 1C), possibly because of a feedback-loop between ICOSL and its partner ICOS (33) expressed on TFH cells. Together with missing GC formation, these findings suggest a defect in TFH cells within Irf4−/− mice.

Irf4−/− Mice Fail to Generate TFH Cells.

To directly test this theory, LN cells of L. major infected mice were analyzed for expression of TFH marker molecules. In Irf4+/− mice, TFH cells expressing BCL-6, IL-21, and PD-1 were present and coexpressed ICOS at high (ICOShi) or intermediate (ICOSint) levels. Importantly, Irf4−/− CD4+ cells totally lacked ICOShi cells, although ICOSint cells were present at even enhanced frequency (Fig. 2A). Both findings were confirmed in PP of naive mice (Fig. 3C). As for PD-1, its expression was comparable in CD4+ cells of infected Irf4−/− and Irf4+/− mice (Fig. 2A), but was also reduced in Irf4−/− CD4+ cells of naive PP (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, amounts of BCL-6 protein, a central molecule for TFH cell function (11–13), were considerably lower in Irf4−/− than in Irf4+/− CD4+ cells (Fig. 2B).

An even stronger defect was noted with respect to IL-21 production (Fig. 2C): after short-term restimulation, IL-21 protein was synthesized by many of the ICOShi and ICOSint Irf4+/− control cells (thus further characterizing them as the source of TFH cells), but not by Irf4−/− CD4+ cells (Fig. 2C, Left). To measure expression of Il-21 at the mRNA level, we performed quantitative PCR (qPCR) directly ex vivo (Fig. 2C, Right) after sorting ICOShi (only control mice), ICOSint, and ICOSlo cell populations (Fig. 2A), Again, most Il-21 mRNA was detected in ICOShi Irf4+/− control cells, but the lower levels in ICOSint cells were further reduced in their Irf4−/− counterparts. These data demonstrate a striking defect of Irf4−/− CD4+ cells to express TFH cell markers.

Analysis of CXCR5 Expression.

Expression of the CXCR5 molecule permits TFH cell migration into GCs (16), but is found at even higher levels in B cells (15). Recently T–B conjugates have been described in FACS analyses of LN cell preparations (5). These conjugates might contain TFH cells tightly interacting with B cells and complicate testing of CXCR5 expression on T cells. Indeed, we identified CD4+ events with considerable CXCR5 costaining (Fig. S2A) as aggregates of CD4+ T and B220+ B cells (Fig. S2B). In contrast, CXCR5-staining was weaker on single CD4+ T cells, despite nice staining of single B cells within the same sample (Fig. S2B). Mechanical dissociation and reanalysis confirmed lower CXCR5 staining on T cells. Thus, outgating of B–T conjugates did not remove any TFH cells with particularly strong CXCR5 staining, and was routinely used during data acquisition (with the exception of Figs. S2 and S3). We detected B–T conjugates not only in the Leishmania model, but also in PP of naive mice (Figs. S2 and S3) or after MOG immunization. Although CXCR5 clearly remains a marker of TFH cells, these T–B conjugates suggest critical care during its staining on T cells.

When we now compared CXCR5 expression on Irf4−/− and WT cells, we found that CXCR5 staining was totally absent in Irf4−/− CD4+ cells (Fig. 2D), confirming their lack of TFH cells. Importantly, this conclusion required exclusion of B–T conjugates from the analysis (Fig. S3, gate B), because gating on all viable CD4+ events revealed CD4+CXCR5+ events (Fig. S3A) as a result of aggregating CXCR5-expressing Irf4−/− B cells (Fig. S3B, gate A). Mechanical disruption of the conjugates and reanalysis confirmed these conclusions (Fig. S3C) and excluded removal of CXCR5+ Irf4−/− TFH cells. As anticipated, we found a positive correlation for expression of CXCR5 and BCL-6 in Irf4+/− mice (Fig. 2E). Similar data were gained from PP of Irf4−/− mice (Fig. 3C, and Fig. S3 D and E). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that Irf4−/− T cells do not differentiate into TFH cells in vivo, but CXCR5 deficiency may explain lack of GC formation in Irf4−/− mice because of altered T-cell migration.

To rule out a defect of Irf4−/− T cells in their receptor-triggered antigenic response as a trivial reason for TFH cell deficiency, we restimulated LN cells of infected mice in vitro. In response to Leishmania antigens, Irf4−/− and Irf4+/− control CD4+ cells secreted the precursor T-cell product IL-2 into their supernatants at the same order of magnitude (Fig. S4A). Similarly, the frequency of intracellularly stained IL-2–producing CD4+ cells was similar between the two genotypes (Fig S4B).

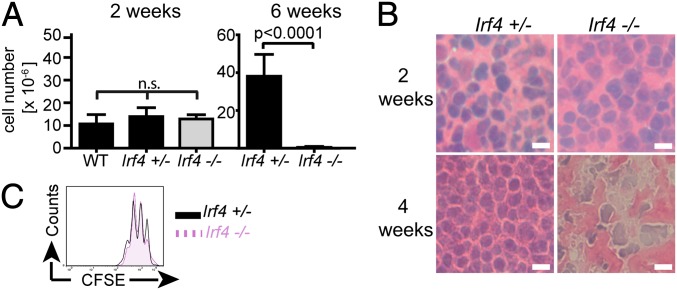

Lack of Irf4−/− TFH Cells Is Not Caused by a Cell Viability Problem.

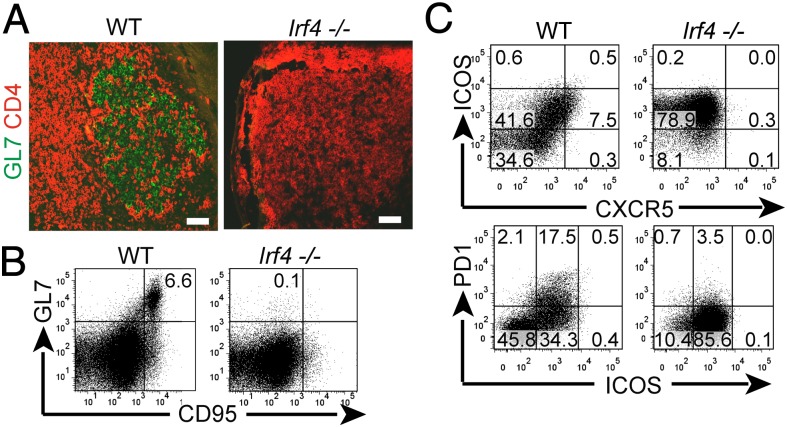

Previously, we reported on apoptotic death of Irf4−/− draining LN cells after about 6 wk of leishmaniasis (34). We therefore aimed to exclude that a cell viability problem hindered GC formation earlier after infection. In naive young Irf4−/− and Irf4+/− mice, the size of popliteal LNs was comparable (about 1 × 106 cells). Furthermore, the increase in LN size and histological appearance 2 wk after infection were similar (Fig. 4 A and B), but Irf4−/− and Irf4+/− CD4+ LN T cells were comparably able to secrete IL-2 (Fig. S4) and to proliferate in response to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin (Fig. 4C). These data confirm functional integrity of Irf4−/− LN CD4+ T cells at the time point when the lack of GC formation was noted. In contrast, Irf4−/− LNs had almost totally disappeared 6 wk after infection (Fig. 4A), and severe damage in LN cell morphology was already visible 4 wk after infection (Fig. 4B). Cell death did not occur in other LNs of infected Irf4−/− mice. The divergence in LN cell viability of WT and Irf4−/− mice 6 but not 2 wk after infection is underscored by the compiled statistical significance of all mice tested (Fig. 4A). In conclusion, lack of Irf4−/− GC formation cannot be explained by disturbed cell viability.

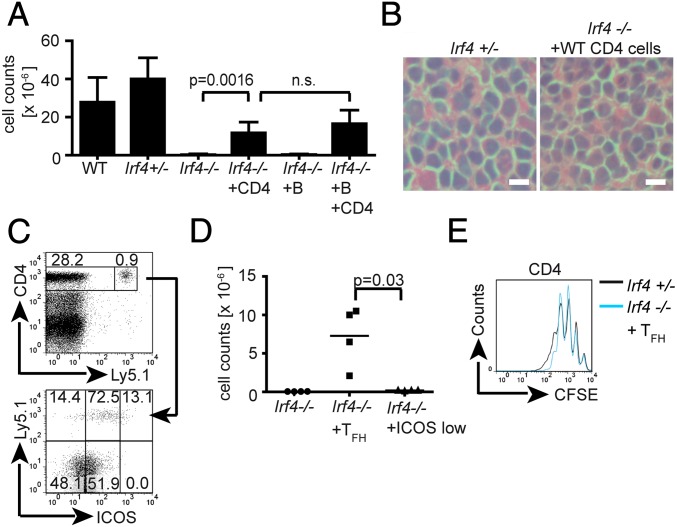

Fig. 4.

Disappearance of lesion-draining LNs in L. major infected Irf4−/− mice. Mice of the indicated genotypes were infected with L. major. At the indicated time points, popliteal LNs were prepared and (A) cell numbers in single-cell suspensions counted (mean ± SD) or (B) tissue sections processed for HE staining and microscopy (40× magnification). (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (C) To control for proliferative capacity 2 wk after infection, cells were labeled with 5-(and 6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE), stimulated for 72 h with PMA/ionomycin, and stained for CD4. Data are representative of five (A) or three (B and C) different experiments, each with three mice per group and (B and C) show the results of one representative mouse per group.

Rescue of GC Formation by WT CD4+ T Cells.

Although a primary Irf4−/− TFH cell defect was likely, a B-cell defect with altered T–B interactions and secondary TFH cell deficiency remained possible. To directly prove a T-cell intrinsic TFH promoting IRF4 activity, Irf4−/− mice were reconstituted intraperitonially with purified CD45 (Ly5.1+) congenic CD4+ cells from naive mice at the start of infection. Two weeks later—that is, at the maximum of GC formation in WT mice—transferred WT CD4+ T cells had perfectly rescued the appearance of GCs and GL7+ Irf4−/− B cells (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the WT cells tended to accumulate close to the GC areas, but endogenous CD4+ T cells mostly remained outside of them. By flow cytometry, WT CD4+ T-cell transfer totally rescued the generation of Irf4−/− GL7+CD95+ GC B cells (Fig. 5B) and the compensatory up-regulation of ICOSL on Irf4−/− B cells was almost reverted (Fig. 5C). Because WT CD4+ cells can induce GC formation and GC B-cell differentiation in Irf4−/− mice, their TFH defect is caused by an intrinsic T- but not B-cell defect. Accordingly, B-cell–specific deficiency in IRF4 leads to disturbed plasma cell differentiation, but no change in GC formation (28). However, this plasma cell defect precludes demonstration of effects of the transferred WT CD4+ T cells on antibody formation in our mice.

Fig. 5.

Rescue of GC formation by WT CD4+ T cells. Irf4−/− mice (A–C) or Irf4+/− mice (B and C) were infected with L. major. Where indicated, Irf4−/− mice received 8 × 106 Ly5.1 congenic WT CD4+ cells by intraperitoneal adoptive transfer on the day of infection. Two weeks later, popliteal LNs were prepared. (A) Tissue sections were stained with antibodies to CD4 (blue), Ly5.1 (red), and GL7 (green) followed by fluorescence-microscopy (20× magnification). (Scale bars, 50 μm.) (B and C) Cells in suspension were stained for B220, GL7, ICOSL, and CD95 and analyzed (B220+ gate) by flow cytometry. Numbers refer to percentages in the quadrant below the number (C) or within the indicated gate (B). SSC, side scatter. Data are from one representative mouse per group. Three (A) or two (B and C) different experiments, each with three mice per group, were performed with similar outcome.

Rescue of LN Cell Survival by WT CD4+ T Cells.

Like GC formation, LN cell survival 6 wk after infection was rescued to a great extent by transferred CD4+ cells and normal histological morphology was regained (Fig. 6 A and B). Most of the surviving LN cells did not express the Ly5.1 marker of the transferred WT cells (Fig. 6C) and Ly5.1-expressing cells were all CD4+. Thus, LN cell viability was not secondary to outgrowth of WT CD4+ cells. Instead, WT CD4+ cells caused improved survival of endogenous Irf4−/− B and T cells. Of note, WT CD4+ T cells were perfectly able to become ICOShi cells within Irf4−/− LNs (Fig. 6C). Thus, the defect in Irf4−/− TFH cells is not caused by deficiencies of accessory cells (e.g., in antigen presentation or production of necessary cofactors). Furthermore, even the side-by-side presence of WT TFH cells did not catalyze ICOShi expression, and thus TFH cell differentiation in endogenous Ly5.1− Irf4−/− CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Rescue of LN cell survival by WT CD4+ cells. (A–C) Where indicated, Irf4−/− mice received 8 × 106 Ly5.1 congenic WT B or CD4+ cells or both by intraperitoneal transfer, were infected, and analyzed 6 wk later in comparison with infected WT or Irf4+/− mice. (A) Popliteal LN cell numbers. (B) H&E staining (40× magnification) (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (C, Upper) total life cell gate. Numbers refer to the percentage of CD4+Ly5.1− or CD4+Ly5.1+ among total cells. (Lower) Relative cell percentages among CD4+Ly5.1+ cells (Upper numbers) or CD4+Ly5.1− cells (Lower) within the respective rectangles. (D and E) TFH cells (CD4+ICOShiCXCR5+) or control CD4+/ICOS−/CXCR5− cells sorted (Fig. S6) from 2 wk-infected Ly5.1+ WT mice were transferred intraperitoneally (2 × 105 per mouse) into Irf4−/− mice which, together with control mice, were infected with L. major. After 6 wk, cell numbers of the draining LNs were counted (D) and the proliferative capacity of the cells determined by CFSE dilution (E). Data are representative of three (A–C) or two (D and E) different experiments, each with three (A–C) or two (D and E) mice per group. (D) Accumulated data ± SD of all mice per group in the two experiments or data from one representative mouse (E).

Unlike T cells, transferred WT B cells neither protected LNs from cell death nor modified the effect of WT CD4+ cells (Fig. 6A). As a positive control for their functionality, we took advantage of the unrelated Irf4−/− B-cell defect (28, 35), leading to drastically reduced serum IgM levels. Analysis of mouse sera after B-cell transfer revealed that the transferred WT B cells raised IgM in Irf4−/− mice almost to WT amounts (Fig. S5A).

Rescue of LN survival mirrored susceptibility toward L. major: transferred WT CD4+, but not B cells, led to a healing phenotype, as measured by lesion size and parasite burden and compared with control Irf4+/− mice (Fig. S5 B and C). However, a high parasite load is probably not the main reason for ensuing cell death in Irf4−/− LN cells, because susceptible BALB/c or IRF1-deficient mice contain even more Leishmania (18), but keep the original size of the LN and develop a cheesy necrosis inside of it.

To formally link TFH cells and protection from cell death, we transferred as few as 2 × 105 FACS-sorted (Fig. S6) WT TFH cells from LNs and spleens of L. major infected Ly5.1+ WT mice. For comparison, ICOS−CXCR5− CD4+ T cells from the same organs were transferred into different Irf4−/− mice. All mice were infected and the draining LNs analyzed 6 wk later. Transfer of TFH cells, but not of ICOS−CXCR5− CD4+ T cells rescued endogenous LN cell viability, as seen from cell numbers and normal proliferative behavior (Fig. 6 D and E). Transferred TFH cells also rescued a resistant phenotype during leishmaniasis (Fig. S5D), and ICOS−CXCR5− CD4+ T cells did not. Taken together, these data suggest a link between the TFH cell defect and cell death in the draining Irf4−/− LNs during chronic leishmaniasis.

Role of IL-21.

Next, we considered lack of a particular TFH cell product as primary cause of LN cell death and missing Irf4−/− GC formation. An important candidate was IL-21, which is induced within TFH cells via the ICOS–c-Maf axis (9, 36) and is required for GC B-cell differentiation (7–10). We considered IL-21 as well, because expression of ICOS and IL-21 by Irf4−/− cells is disturbed (Fig. 2 and ref. 21), and because IRF4 binds the ICOS promoter (25) and mediates cell responses to IL-21 together with STAT3 (37). To test for a role of IL-21, we compared the effects of adoptively transferred purified Il21−/− and WT CD4+ T cells on GC formation and LN cell survival in Irf4−/− mice 2 wk after infection (Fig. 7).

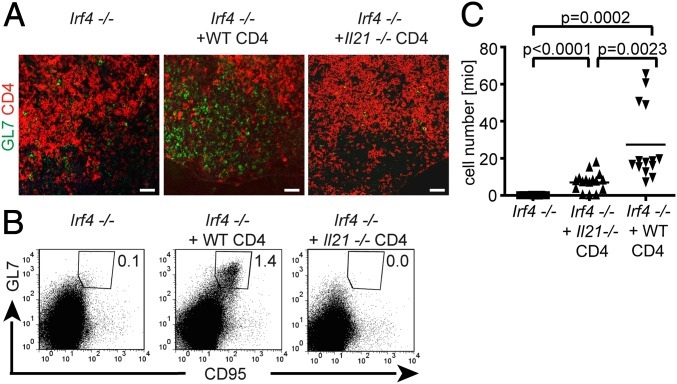

Fig. 7.

Role of IL-21. Irf4−/− mice were infected with L. major. Where indicated, they also received 8 × 106 purified Il21−/− or WT CD4+ cells by intraperitoneal adoptive transfer. Two weeks (A and B) or 6 wk (C) after infection, draining LNs were prepared (B and C) as cell suspensions. (A) Tissue sections stained with antibodies to CD4 (red) and GL7 (green) and analyzed by fluorescence-microscopy (20× magnification). (Scale bars, 50 μm.) (B) FACS analysis of gated B220+ B cells stained for GL7 and CD95. Numbers indicate frequencies of B cells coexpressing GL7 and CD95. (C) Cell numbers within the draining LNs of individual mice with or without transfer of the indicated cells. Data are from one mouse representative for all experiments (A and B) or were compiled from the results of three individual experiments (C).

Although transferred WT cells again perfectly rescued the appearance of GCs and GL7+ cells (Fig. 7A), only few GL7+ cells were detectable after transfer of Il-21−/− CD4+ cells and were spread throughout the LN as in control Irf4−/− mice. Furthermore, transferred WT but not Il-21−/− CD4+ cells rescued the frequency of GL7/CD95 coexpressing GC B cells (Fig. 7B), in comparison with Irf4−/− mice without cell transfer.

To analyze whether IL-21 was also involved in the rescue of LN cell survival by WT cells (Fig. 6), part of the mice was analyzed 6 instead of 2 wk after infection. Transfer of Il-21−/− CD4+ cells created an intermediate phenotype compared with Irf4−/− mice receiving either no or WT CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7C). Accumulation of all data from the different experiments revealed less potent effects of Il-21−/− than of WT CD4+ cells with clear statistical difference. However, even if their effects on Irf4−/− LN cell survival were weaker, they still were demonstrable with high significance compared with Irf4−/− mice without cell transfer.

Discussion

In the past, IRF4 has been characterized as an important transcription factor for differentiation of Th2, Th9, and Th17 cells. In addition, aspects of Treg cell function entirely depend on IRF4 (20–23, 25–27). In the B-cell lineage, IRF4 is important for plasma cell differentiation and isotype switching (28, 29). Our results link these previous findings in B and T cells and show an additional important role of IRF4 for development of TFH cells, which are mainly responsible for the intricate organization of T–B interactions and antibody maturation in vivo.

For our analysis, we used infection of mice with L. major, a model characterized by strong B- and T-cell interactions and LN hyperplasia (30). When analyzing LNs of WT and Irf4−/− mice at the height of GC formation in WT mice, a striking defect of Irf4−/− mice became apparent: despite normal structure of B- and T-cell areas, their LNs totally lacked GC formation and differentiation of GC B cells. These findings were confirmed in PPs of naive mice and after immunization with a peptide instead of L. major infection. In parallel, LN CD4+ T cells expressed strongly reduced amounts of the TFH cell-related (2, 11–13, 15, 16) molecules ICOS, IL-21, and BCL-6.

A remarkable result was obtained with respect to the TFH marker CXCR5 in that LN cell suspensions contained conjugates of adherent B–T cells, which conferred the risk for misinterpreting FACS data on CXCR5-expression in CD4+ T cells, because of stronger CXCR5 expression on B cells. Similar B–T conjugates have recently been described and characterized for their B-cell part (5). The lower amounts of CXCR5 on single T cells correlated with high expression of ICOS and IL-21, indicating that CXCR5 can still be used to characterize TFH cells. These findings were again confirmed in LNs of mice immunized with a peptide or in PPs from naive mice.

Integration of this information in the analysis of Irf4−/− TFH cell development revealed that Irf4−/− LN CD4+ cells were completely CXCR5−. Importantly, this defect was only notable when the B–T conjugates were either out-gated or mechanically separated, because CXCR5 expression on Irf4−/− B cells was as high as in WT mice. Lack of CXCR5 on Irf4−/− CD4+ but not B cells suggests a T-cell intrinsic differentiation defect that cannot solely be caused by binding of IRF4 to the cxcr5 gene promoter. With respect to ICOS, its promoter has previously been linked to IRF4 (25). However, ICOS expression is not totally IRF4-dependent, because frequencies of Irf4−/− cells with intermediate ICOS expression were even increased (Figs. 2 and 3), perhaps in a feedback-loop triggered by deficient terminal TFH cell differentiation. Lower ICOS expression may be one reason why Irf4−/− T cells produced almost no IL-21, because Il-21 transcription is induced by an axis via ICOS and c-Maf (36). However, impaired IL-21 production may also mirror an intrinsic deficiency of Irf4−/− T cells, given that naive Irf4−/− CD4+ T cells stimulated in vitro under Th17-inducing conditions also produced less IL-21 (21). In contrast to ICOS, the TFH cell marker PD-1 was normally expressed in T cells of L. major infected Irf4−/− mice. Therefore, missing T-cell stimulation is unlikely to explain absent Irf4−/− TFH cell development, a conclusion supported by normal IL-2 production in response to Leishmania antigens.

Importantly, missing Irf4−/− TFH cells and GCs correlated with eventual total LN cell death after initial LN hyperplasia. We have previously described enhanced in vitro sensitivity of Irf4−/− CD4+ cells to activation-induced cell death (34). Herein, we observed that death of Irf4−/− LN cells could be avoided by presence of WT CD4+ but not B cells. Only few CD4+ WT cells were required for protection, based on their low frequency within the surviving LN cells. LN cell survival was also saved by very few Leishmania primed WT TFH cells, thus linking TFH cells and protection from cell death. LN cell survival correlated with resistance to the parasite. Nevertheless, it is difficult to attribute this feature solely to the presence of TFH cells, because Irf4−/− mice are also devoid of Th9 or Th17 cells (20, 26, 27). A direct causal link of parasite burden and LN cell survival is not likely, given that draining LNs of mice from other highly susceptible strains behave totally differently.

Of note, adoptive transfer of WT CD4+ cells rescued not only LN cell survival, but also appearance of GCs and GC B cells with normalized expression of ICOSL in accordance with the feedback-loop between ICOS and ICOSL (33). These findings underline that the Irf4−/− TFH cell defect is T-cell intrinsic and support a report on normal GC formation in mice with a B-cell–specific defect of IRF4 (28). Transfer of Il-21−/− CD4+ T cells proved a central role for IL-21 during the rescue of GC formation. In contrast, IL-21 was necessary but not sufficient for protection from LN cell death, because Il-21−/− CD4+ T cells supported cell survival only partially. LN cell survival during a chronic immune response is of central importance and may be regulated by independent effector molecules, such as IL-4, which is produced locally by TFH cells (4, 5) and which (like IL-21) cannot be produced by Irf4−/− Th cells (22, 23).

As for the mechanism how IRF4 affects TFH cell differentiation, we consider an important role to their key transcription factor BCL-6 (11–13), because its amounts are strongly reduced in Irf4−/− CD4+ T cells. Apparently, this BCL-6–enhancing function of IRF4 is cell-type–specific, because IRF4 suppresses BCL-6 transcription in B cells (38). In addition, IRF4 physically binds to BCL-6 (39) and lack of this interaction may explain why Irf4−/− Th cells are totally unable to differentiate into TFH cells, although they still express some BCL-6. Possibly, the TFH inducing capacity of BCL-6 requires its interaction with IRF4.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a decisive role of IRF4 for development of TFH cells and, as a consequence, formation of GCs, differentiation of GC B cells, and survival of LN cells during an immune response. Together with the earlier findings that IRF4 also targets class-switching and terminal plasma cell differentiation, our study places IRF4 in the center of B–T cooperation during the formation of an adaptive immune response.

Materials and Methods

Mice and L. major Infection or Immunization.

WT C57BL/6 mice, purchased from Charles River, CD45.1 congenic, Il-21−/− (from National Institutes of Health Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Centers), and Irf4+/− and Irf4−/− mice (bred in our own animal facilities) were used at 6–10 wk of age. Infection with promastigotes of the L. major strain MHOM/IL/81/FEBNI into the footpad, determination of lesion development or parasite burden, and leishmania-specific in vitro cell restimulation were performed as previously described (18, 34). Popliteal LNs or spleens were removed at the indicated timepoints for histology, qPCR, and FACS analysis, as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Total IgM levels were measured in a sandwich ELISA by coating with goat anti-mouse IgM followed by application of mouse sera and detection with AP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM (both reagents from Chemicon/Millipore). Immunization with MOG peptide and adjuvant was performed as previously described (20). All animal experiments were approved by “Regierungspräsidium Gießen” [permission number: V54-19c20-15(1) MR 20/6 Nr47/2009], the local institutional committee.

Statistics.

For statistical analysis, we used an unpaired t test with Welch’s correction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Uli Steinhoff for helpful discussions. This work was supported by a Landes-Offensive zur Entwicklung Wissenschaftlich-ökonomischer Exzellenz (LOEWE) grant Tumor and Inflammation (Germany), Behring-Röntgen-Stiftung, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB TR22), and Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, Germany.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1205834109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nowak EC, Noelle RJ. Interleukin-9 as a T helper type 17 cytokine. Immunology. 2010;131:169–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breitfeld D, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1545–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaerli P, et al. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1553–1562. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King IL, Mohrs M. IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells in reactive lymph nodes during helminth infection are T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1001–1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reinhardt RL, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chtanova T, et al. T follicular helper cells express a distinctive transcriptional profile, reflecting their role as non-Th1/Th2 effector cells that provide help for B cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:68–78. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant VL, et al. Cytokine-mediated regulation of human B cell differentiation into Ig-secreting cells: Predominant role of IL-21 produced by CXCR5+ T follicular helper cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:8180–8190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linterman MA, et al. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J Exp Med. 2010;207:353–363. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogelzang A, et al. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zotos D, et al. IL-21 regulates germinal center B cell differentiation and proliferation through a B cell-intrinsic mechanism. J Exp Med. 2010;207:365–378. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston RJ, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325:1006–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nurieva RI, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu D, et al. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akiba H, et al. The role of ICOS in the CXCR5+ follicular B helper T cell maintenance in vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175:2340–2348. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Förster R, et al. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell. 1996;87:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haynes NM, et al. Role of CXCR5 and CCR7 in follicular Th cell positioning and appearance of a programmed cell death gene-1high germinal center-associated subpopulation. J Immunol. 2007;179:5099–5108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohoff M, Mak TW. Roles of interferon-regulatory factors in T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:125–135. doi: 10.1038/nri1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohoff M, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-1 is required for a T helper 1 immune response in vivo. Immunity. 1997;6:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taki S, et al. Multistage regulation of Th1-type immune responses by the transcription factor IRF-1. Immunity. 1997;6:673–679. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brüstle A, et al. The development of inflammatory T(H)-17 cells requires interferon-regulatory factor 4. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:958–966. doi: 10.1038/ni1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huber M, et al. IRF4 is essential for IL-21-mediated induction, amplification, and stabilization of the Th17 phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20846–20851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809077106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohoff M, et al. Dysregulated T helper cell differentiation in the absence of interferon regulatory factor 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11808–11812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182425099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rengarajan J, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) interacts with NFATc2 to modulate interleukin 4 gene expression. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1003–1012. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langrish CL, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y, et al. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009;458:351–356. doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Q, et al. IRF-4-binding protein inhibits interleukin-17 and interleukin-21 production by controlling the activity of IRF-4 transcription factor. Immunity. 2008;29:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staudt V, et al. Interferon-regulatory factor 4 is essential for the developmental program of T helper 9 cells. Immunity. 2010;33:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein U, et al. Transcription factor IRF4 controls plasma cell differentiation and class-switch recombination. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:773–782. doi: 10.1038/ni1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sciammas R, et al. Graded expression of interferon regulatory factor-4 coordinates isotype switching with plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2006;25:225–236. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lohoff M, Matzner C, Röllinghoff M. Polyclonal B-cell stimulation by L3T4+ T cells in experimental leishmaniasis. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2120–2124. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.2120-2124.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagresle C, Bella C, Daniel PT, Krammer PH, Defrance T. Regulation of germinal center B cell differentiation. Role of the human APO-1/Fas (CD95) molecule. J Immunol. 1995;154:5746–5756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laszlo G, Hathcock KS, Dickler HB, Hodes RJ. Characterization of a novel cell-surface molecule expressed on subpopulations of activated T and B cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:5252–5262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe M, et al. Down-regulation of ICOS ligand by interaction with ICOS functions as a regulatory mechanism for immune responses. J Immunol. 2008;180:5222–5234. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lohoff M, et al. Enhanced TCR-induced apoptosis in interferon regulatory factor 4-deficient CD4(+) Th cells. J Exp Med. 2004;200:247–253. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mittrücker HW, et al. Requirement for the transcription factor LSIRF/IRF4 for mature B and T lymphocyte function. Science. 1997;275:540–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauquet AT, et al. The costimulatory molecule ICOS regulates the expression of c-Maf and IL-21 in the development of follicular T helper cells and TH-17 cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:167–175. doi: 10.1038/ni.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon H, et al. Analysis of interleukin-21-induced Prdm1 gene regulation reveals functional cooperation of STAT3 and IRF4 transcription factors. Immunity. 2009;31:941–952. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito M, et al. A signaling pathway mediating downregulation of BCL6 in germinal center B cells is blocked by BCL6 gene alterations in B cell lymphoma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta S, Jiang M, Anthony A, Pernis AB. Lineage-specific modulation of interleukin 4 signaling by interferon regulatory factor 4. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1837–1848. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.