Abstract

Recent studies of spider phobia have indicated that disgust is a crucial disorder-relevant emotion and that the facial electromyogram (EMG) of the levator labii region is a reliable disgust indicator. The present investigation focused on EMG effects of psychotherapy in thirty girls (aged between 8 and 14 years) suffering from spider phobia. They were presented with phobia-relevant, generally fear-inducing, disgust-inducing and affectively neutral pictures in a first EMG session. Subsequently, patients were randomly assigned to either a therapy group or a waiting-list group. Therapy-group participants received a single session of exposure therapy in vivo. One week later a second EMG session was conducted. Patients of the waiting-list group received exposure therapy after the second EMG session. After therapy, the girls were able to hold a living spider in their hands and rated spiders more positive, and less arousing, fear- and disgust-inducing. Moreover, they showed a reduction of average levator labii activity in response to pictures of spiders, reflecting the reduction of feelings of disgust. A positive side effect of the therapy was a significant drop in overall disgust proneness and a decreased average activity of the levator labii muscle in response to generally disgust-inducing pictures. Results emphasize the role of disgust feelings in spider-phobic children and suggest that overall disgust proneness should also be targeted in therapy.

Keywords: Spider phobia, Children, EMG, Levator labii, Disgust proneness, Anxiety

1. Introduction

With a prevalence rate of 3.5% spider phobia is rather common in adults (Fredrikson et al., 1996). The disorder shows a very early onset in early childhood (Becker et al., 2007). Moreover, spiders are known to possess highly fear-inducing properties in children (Muris et al., 1997). In general, females are more likely to develop spider phobia than males (Essau et al., 2000; Federer et al., 2000; Fredrikson et al., 1996; Muris et al., 1999). The disease-avoidance model of spider phobia suggests that spiders are primarily avoided because of their association with disease and contamination (Matchett and Davey, 1991). This conception is in contrast to the idea that spiders are avoided because of the fear of being physically harmed (Öhman and Mineka, 2001) which is also addressed in the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). However, the majority of patients also experiences high levels of disgust during confrontation with spiders.

The typical facial expression of disgust is the nose wrinkle and the retraction of the upper lip (Ekman, 1971) coupled with increased electromyographic (EMG) activity of the levator labii region (e.g., Schienle et al., 2001; Stark et al., 2005; Vrana, 1993). The activation of this muscle region is specific to disgust and has been observed during symptom provocation in spider-phobic adults (De Jong et al., 2002; Vernon and Berenbaum, 2002) and children (Leutgeb et al., 2010). De Jong et al. (2002) and Leutgeb et al. (2010) showed enhanced levator labii muscle activity in spider phobics (relative to healthy controls) during exposure to spiders and generally disgust evoking stimuli. While De Jong et al. (2002) employed guided imagery Leutgeb et al. (2010) used passive picture viewing. Additionally, Vernon and Berenbaum (2002) revealed a higher frequency of facial expressions of disgust in spider phobics (relative to healthy controls) during a behavioral avoidance test with a living tarantula.

The disease-avoidance model predicts that concerns about spiders are associated with the apprehension of contamination. There are, indeed, data supporting the view that contamination sensitivity and habitual disgust might be important factors for the development and maintenance of spider phobia (for a review see Cisler et al. 2009; Olatunji et al., 2010). Besides feelings of disgust for spiders per se, studies have shown heightened overall disgust proneness in spider-phobic adults (e.g., De Jong et al., 2002; Merckelbach et al., 1993) and children (e.g., De Jong et al., 1997; Leutgeb et al., 2010).

It has been hypothesized that feelings of disgust and fear are independent from each other in spider phobia (De Jong et al., 2002) and that the role of disgust in the disorder is smaller than that of fear (Sawchuk et al., 2002; Tolin et al., 1997). However, Gerdes et al. (2009) argue that harmfulness alone cannot explain why spiders are feared so frequently. Moreover, De Jong and Muris (2002) claim that the essence of spider phobia is the fear of making physical contact with a disgusting stimulus. Besides fear, another diagnostic criterion for spider phobia (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) is pronounced avoidance if confronted with spiders. In line with this in a study by Mulkens et al. (1996) 75% of spider phobics (as opposed to 30% of non-phobics) refused to eat a cookie that had previously been touched by a spider. In this regard the mechanisms causing avoidance of spiders might primarily be activated by feelings of disgust, and not by fear (Woody et al., 2005). Consequently, both emotional reactions should be targeted in the course of psychotherapy.

Only a few investigations exist examining the influence of disgust on treatment outcomes for spider-phobic children. In the study by De Jong et al. (1997) there was a parallel decline of spider fear and feelings of disgust for spiders in the course of therapy, whereas overall disgust proneness remained unaffected. The authors concluded that overall disgust proneness might be a vulnerability factor of spider phobia, and not an epiphenomenon of the disorder. Olatunji et al. (2011) reported that changes in fear and disgust are important for a successful treatment of spider phobia.

The present study aimed to investigate the effect of exposure therapy in spider-phobic girls on facial EMG activity during the viewing of pictures displaying spiders and generally fear- or disgust-inducing contents. We expected reduced levator labii activity in response to pictures of spiders after psychotherapy. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation analyzing effects of exposure therapy on facial EMG activity.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty right-handed and non-medicated girls aged from 8 to 14 years participated in the current study. Participants were recruited via articles in local newspapers. All girls suffered from spider phobia (DSM-IV-TR: 300.29). Diagnoses were made by a board-certified clinical psychologist. Children were randomly assigned to either a therapy group (N = 16) or a waiting-list group (N = 14). Both groups were comparable with respect to age (M (SD): therapy group = 137.3 (15.0) months; waiting-list group = 138.5 (21.0) months). All participants and their parents gave written informed consent after the nature of the study had been explained to them. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Graz.

2.2. Procedure

First, all girls underwent a diagnostic session consisting of a clinical interview (Unnewehr et al., 1995; DIPS, child version) and a detailed interview checking diagnostic criteria of spider phobia according to the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Additionally, children filled out the Spider Phobia Questionnaire for Children (SPQ-C, Kindt et al., 1996), a child-adapted version of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Disgust Proneness (QADS, Schienle et al., 2002), and the trait-scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C, Spielberger et al., 1973). Finally, children underwent a behavior avoidance test. A spider (Tegenaria atrica, approximately 3 cm) was put in a transparent case and placed on a table 5 m from the participant who was then instructed to approach the box. The children received scores (range 0–12) according to their approach behavior (0 points = refuses to enter the room, 1 = stays 5 m away from the box, 2 = 4 m distance, 3 = 3 m distance, 4 = 2 m distance, 5 = 1 m distance, 6 = standing at the table, 7 = touching the box, 8 = opening the box, 9 = putting the hand into the box, 10 = touching the spider with one finger, 11 = removing the spider from the box and holding it in their hands for less than 20 s, 12 = removing the spider from the box and holding it in their hands for 20 s or longer). Subsequently, a diagnostic session with a parent, which consisted of a clinical interview (Unnewehr et al., 1995; parent version), was conducted. Diagnoses were determined on the basis of child and parent reports. For diagnosing spider phobia the DSM-IV-TR criteria had to be met, and there were cutoff scores for the SPQ (at least 15 points) and the behavior avoidance test (not more than 7 points, which means that they did not open the spider’s box). All patients reported to experience massive amounts of fear and disgust when confronted with spiders, profound avoidance behavior, and severe restrictions in their daily lives or intense suffering. Patients who suffered from any other mental disorder than spider phobia were excluded.

Approximately one week later all children underwent a combined session during which the electromyogram (EMG) and the electroencephalogram (EEG) were recorded. EEG data are not presented herein but will be reported elsewhere. During the experimental session children were exposed to a total of 130 pictures. The slides represented four different emotional categories: ‘Spider’ pictures depicted spiders in different environments, ‘Fear’ pictures depicted predators (e.g., shark, lion), ‘Disgust’ pictures represented different domains like ‘repulsive animals’ (e.g., maggots) or ‘poor hygiene’ (e.g., dirty toilet) and ‘Neutral’ pictures depicted household articles, or geometric figures. Pictures were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS, Lang et al., 1999) and a second picture set (Schienle et al., 2005). Thirty pictures were shown per category. Additionally, 10 positive ‘motivators’ were presented to make the children feel more comfortable (e.g., bunnies, kittens). ‘Negative’ pictures (‘Fear’, ‘Disgust’) were chosen to be appropriate for children (e.g., no mutilation or violence pictures were included). Pictures were shown in a random order for 6 s each. Inter-stimulus intervals varied between 4 and 8 s. After the experiment, children rated their impression of the pictures by means of the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM; Bradley and Lang, 1994) for ‘valence’ and ‘arousal’, and on two nine-point Likert scales on the dimensions ‘fear’ and ‘disgust’ (range 1–9, with ‘9’ indicating that the subject felt very positive, aroused, anxious or disgusted). Four sheets, each depicting all thirty pictures of one category were shown to the children who were asked to give affective ratings for the picture category as a whole. The sequence of categories was randomized.

The girls then were randomly assigned to either a therapy group or a waiting-list group. Children of the therapy group received a single session of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) according to Öst (1989), which lasted for a maximum of 4 h. The therapy consisted of detailed psychoeducation about fear and spiders, and exposure in vivo with participant modeling and cognitive restructuring. One week after therapy, a second EMG/EEG session with subsequent SAM rating was conducted. Children were exposed to the same picture set as in the first session. Moreover, children again filled out the Spider Phobia Questionnaire for Children (SPQ-C, Kindt et al., 1996), the child-adapted version of the Questionnaire for the Assessment of Disgust Proneness (QADS, Schienle et al., 2002), and the trait-scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C, Spielberger et al., 1973). Children of the waiting-list group received CBT after the second EMG/EEG session.

2.3. Data recording and analysis

EEG and EMG data were recorded with a Brain Amp 32 system (Brain Products, Gilching) and an Easy-Cap electrode system (Falk Minow Services, Munich). Data were sampled with 2500 Hz and passband was set to 0.016–1000 Hz. Prior to the placement of the electrodes, the sites on the participants’ scalp and face were cleaned with alcohol and gently abraded. All impedances of the EMG electrodes were below 10 kΩ. EMG electrodes were placed on the left hemisphere on the levator labii muscle according to the guidelines by Tassinary et al. (2007). Electrodes were referenced to FCz. Unipolar EMG channels were transformed to a bipolar montage. A bipolar horizontal electrooculogram (EOG) was recorded from the epicanthus of each eye, and a bipolar vertical EOG was recorded from the supra- and infra-orbital position of the right eye. The EOG was recorded to allow the identification of visual artifacts in EEG data. EMG data were visually inspected for artifacts, and in preparation for statistical analysis bandpass filtered (30–500 Hz, 24 dB/octave), rectified, and low pass filtered (8 Hz, 24 dB/octave). Smoothed EMG segments from individual stimuli were baseline corrected by a 1 s pre-stimulus baseline. Analyses were performed with Brain Vision Analyzer software Version 2.0 (Brain Products, Gilching). Average activity in the time interval of 2500–4500 ms following picture onset served as dependent variables in subsequent statistical analysis.

For statistical data analysis PASW Statistics (Version 18.0) was used. Behavior avoidance test and questionnaire data (see Table 1) were submitted separately to repeated-measurement ANOVAs with the between-subjects factor group (therapy group, waiting-list group) and the repeated-measurement factors time (time 1, time 2). Affective ratings (experienced valence, arousal, fear and disgust; see Table 1) and mean facial EMG activity were submitted separately to repeated-measurement ANOVAs with the between-subjects factor group (therapy group, waiting-list group) and the repeated-measurements factors time (time 1, time 2) and category (Spider, Disgust, Fear, Neutral). Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to correct for violations of sphericity. To clarify significant interactions, further analyses were conducted by means of within group one-way ANOVAs with post-hoc t-tests and between-groups t-tests.

Table 1.

Behavior avoidance test, questionnaire data (SPQ-C, QADS-C, STAI-C) and affective ratings of Spider, Disgust, Fear, and Neutral pictures (means, M and standard deviations, SD) of therapy and waiting-list group participants before (session 1) and after (session 2) therapy or time of waiting.

| Therapy group M (SD) |

Waiting-list group M (SD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 1 | Session 2 | |

| Behavior avoidance test | 5.7 (1.9) | 11.7 (0.7) | 4.7 (2.9) | 5.9 (2.2) |

| SPQ-C | 18.5 (2.9) | 5.2 (3.4) | 18.4 (3.6) | 17.9 (3.7) |

| QADS-C | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.7) |

| STAI-C | 36.4 (7.6) | 32.1 (6.7) | 32.5 (5.9) | 35.0 (8.2) |

| Spider pictures | ||||

| Valence | 1.8 (0.9) | 5.5 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.9 (0.9) |

| Arousal | 6.6 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.6) |

| Fear | 6.5 (2.1) | 1.4 (0.6) | 5.8 (2.0) | 5.9 (1.7) |

| Disgust | 6.0 (2.2) | 1.8 (0.9) | 7.1 (1.6) | 6.3 (2.3) |

| Disgust pictures | ||||

| Valence | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 2.9 (1.8) | 2.6 (1.4) |

| Arousal | 4.6 (2.1) | 2.9 (1.6) | 4.8 (2.0) | 4.9 (2.0) |

| Fear | 2.0 (2.1) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.8) |

| Disgust | 6.7 (1.9) | 4.4 (1.6) | 6.6 (2.7) | 6.8 (2.2) |

| Fear pictures | ||||

| Valence | 5.3 (2.0) | 5.7 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.0) | 6.1 (1.7) |

| Arousal | 2.5 (1.7) | 1.9 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.7) |

| Fear | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.3 (0.7) | 2.3 (1.9) | 1.9 (1.2) |

| Disgust | 1.3 (0.8) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.5) |

| Neutral pictures | ||||

| Valence | 6.3 (1.8) | 6.3 (1.9) | 7.2 (2.0) | 7.4 (1.9) |

| Arousal | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.0) |

| Fear | 1.1 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.1 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) |

| Disgust | 1.1 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.1 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) |

3. Results

3.1. Self-report and behavior avoidance test data

3.1.1. Questionnaires and behavior avoidance test

Data are listed in Table 1. ANOVAs revealed significant group × time interactions for the behavior avoidance test (F(1,28) = 49.5, p < .001), the SPQ-C (F(1,28) = 84.7, p < .001), the QADS-C (F(1,28) = 10.4, p = .003), and the STAI-C (F(1,28) = 14.4, p = .001). At session 1 therapy and waiting-list group did not differ in their behavior avoidance test performance or in any questionnaire score. From session 1 to session 2 therapy-group participants showed a significant improvement in behavior avoidance test performance (t(15) = 14.0, p < .001), a significant reduction in SPQ-C scores (t(15) = 12.7, p < .001), a significant reduction in QADS-C scores (t(15) = 4.1, p = .001), and a significant reduction in STAI-C scores (t(15) = 3.1, p < .007). Within the waiting-list group there were no changes from session 1 to session 2 in behavior avoidance test performance or SPQ-C and QADS-C scores. However, the waiting-list group showed a significant rise in STAI-C scores (t(13) = 2.3, p = .040).

3.1.2. Affective ratings

Data are listed in Table 1. The repeated-measurements ANOVAs revealed a significant group × time × category interaction for ratings of valence (F(3,84) = 12.9, p < .001), arousal (F(2.3,63.1) = 14.0, p < .001), fear (F(2.2,62.4) = 22.4, p < .001), and disgust (F(2.3,65.5) = 11.1, p < .001). Repeated-measurement ANOVAs within groups revealed significant time × category interactions for valence (F(3,45) = 17.7, p = .001), arousal (F(3,45) = 22.6, p = .001), fear (F(2.2,32.4) = 42.1, p = .001), and disgust (F(3,45) = 29.6, p = .001) for the therapy group, and a significant interaction for valence (F(3,39) = 4.0, p = .015) for the waiting-list group. At session 1 therapy and waiting-list group did not differ concerning their valence, arousal, fear, or disgust ratings of any picture category. Post-hoc t-tests (within each group comparing sessions and categories) revealed that the therapy group rated Spider pictures with higher valence (t(15) = 7.1, p < .001), and with lower arousal (t(15) = 9.3, p < .001), fear (t(15) = 10.0, p < .001), and disgust (t(15) = 6.8, p < .001) at session 2 in comparison to session 1. There were no changes in affective ratings for Spider pictures from session 1 to session 2 in the waiting-list group. Moreover, the therapy group rated Disgust pictures with lower arousal (t(15) = 2.7, p = .016) and disgust (t(15) = 4.6, p < .001) at session 2 in comparison to session 1. There were no changes in affective ratings for Disgust pictures from session 1 to session 2 in the waiting-list group. Additionally, the therapy group rated Fear pictures with lower fear (t(15) = 2.4, p = .028) at session 2 in comparison to session 1. The waiting-list group rated Fear pictures with higher valence (t(13) = 3.4, p = .005) at session 2 in comparison to session 1. In both groups, there were no changes in affective ratings for Neutral pictures from session 1 to session 2. Between-groups t-tests revealed that therapy-group participants displayed significantly higher valence (t(28) = 7.1, p < .001) and lower arousal (t(28) = 8.4, p < .001), fear (t(16.1) = 9.1, p < .001), and disgust ratings (t(16.6) = 6.7, p < .001) for Spider pictures at session 2 than waiting-list group participants. Therapy-group participants reported significantly higher valence (t(28) = 2.1, p = .043) and lower arousal (t(28) = 3.0, p = .005), and disgust ratings (t(28) = 3.4, p = .002) for Disgust pictures at session 2 than waiting-list participants. There were no differences between groups at session 2 concerning Fear or Neutral pictures.

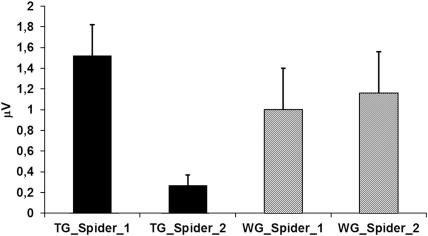

3.2. EMG data

Average EMG activity of the levator labii for Spider, Disgust, Fear, and Neutral pictures before and after therapy (therapy group) or time of waiting (waiting-list group) is shown in Table 2. Grand average waveforms of the levator labii for Spider pictures before and after therapy (therapy group) or waiting time (waiting-list group) are shown in Fig. 1. Average EMG activity of the levator labii for Spider pictures before and after therapy (therapy group) or time of waiting (waiting-list group) is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 2.

Average EMG activity (means, M and standard errors, SE in μV) of the levator labii in response to Spider, Disgust, Fear and Neutral pictures of therapy group and waiting-list group participants before (session 1) and after (session 2) exposure therapy or time of waiting.

| Therapy group M (SE) |

Waiting-list group M (SE) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Session 2 | Session 1 | Session 2 | |

| Spider pictures | 1.5 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) |

| Disgust pictures | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) |

| Fear pictures | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.2) |

| Neutral pictures | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.2) |

Fig. 1.

Grand average waveforms of the levator labii in response to Spider pictures of therapy-group (TG) and waiting-list group (WG) participants before (1) and after (2) exposure therapy or time of waiting.

Fig. 2.

Average EMG activity of the levator labii in response to Spider pictures of therapy group (TG) and waiting-list group (WG) participants before (1) and after (2) exposure therapy or time of waiting. Error bars represent standard errors.

The repeated-measurement ANOVA revealed a significant group × time × category interaction (F(1.6,45.6) = 3.5, p = .046). Repeated-measurements ANOVAs within groups revealed a significant time × category interaction in the therapy group (F(1.6,24.1) = 11.3, p = .001), but not in the waiting-list group (F(1.3,16.8) = 0.2, p = .736). At session 1 therapy group and waiting-list group did not differ concerning their facial EMG activity to any picture category (Spider: t(28) = 1.1, p = .293, Disgust: t(28) = 0.2, p = .822, Fear: t(28) = 1.1, p = .284, Neutral: t(28) = 0.9, p = .402). Post-hoc t-tests (within each group comparing sessions and categories) revealed that the therapy group experienced a significant reduction in facial EMG activity from session 1 to session 2 in response to Spider pictures (t(15) = 4.0, p = .001) and a trend to reduction in response to Disgust pictures (t(15) = 1.9, p = .071). There were no changes in facial EMG activity from session 1 to session 2 in response to Fear (t(15) = 1.3, p = .198) or Neutral (t(15) = 0.1, p = .991) pictures. The waiting-list group showed no changes in facial EMG activity from session 1 to session 2 (Spider: t(13) = 0.4, p = .663, Disgust: t(13) = 0.1, p = .989, Fear: t(13) = 0.6, p = .531, Neutral: t(13) = 0.4, p = .720). Between-groups t-tests revealed that therapy-group participants displayed significantly lower facial EMG activity at session 2 than waiting-list participants (t(16.8) = 2.2, p = .041) in response to Spider pictures. There were no differences between groups at session 2 concerning the other picture categories (Disgust: t(28) = 0.9, p = .401, Fear: t(28) = 0.5, p = .637, Neutral: t(28) = 0.7, p = .495).

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate effects of exposure therapy on facial EMG activity of the levator labii in response to pictures displaying spiders and generally fear- or disgust-inducing contents in 8- to 14-year-old spider-phobic girls.

Most importantly, there was a significant reduction of disgust-related facial EMG activity in response to spiders in the therapy group after exposure therapy, which was not present in the waiting-list group. In recent years there has been emerging evidence that positive effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy in spider phobia can not only be seen in behavioral performance, but also in psychophysiological activity (e.g., Leutgeb et al., 2009; Schienle et al., 2007, 2009; Straube et al., 2006). The current data are in line with these studies. The reduction in levator labii muscle activity was accompanied by changes in affective ratings: after psychotherapy participants rated spiders as less disgust-inducing (and also as less arousing and fear-inducing as well as more positive). Additionally, there was a significant decrease in behavioral avoidance (measured with the behavior avoidance test) and symptom severity according to the SPQ-C.

Interestingly, there were also changes in overall disgust reactivity due to psychotherapy. Firstly, according to the QADS-C scores, overall disgust proneness dropped significantly in the therapy group. Secondly, pictures showing overall disgust-inducing contents were rated less arousing and disgust-inducing by therapy-group participants in the second session as compared to the first session. Moreover, there was a trend for reduced disgust-related facial EMG activity in response to generally disgust-inducing pictures in the therapy group, which was not present in the waiting-list group. During exposure the patients were repeatedly confronted with a stimulus regarded as being disgusting – the spider. Therefore, it is highly likely that the above mentioned results are due to a generalization effect. The current study indicates that exposure therapy is rather successful in reducing feelings of disgust and avoidance motivated by disgust in spider-phobic girls. Moreover, it seems to have broader effects on overall disgust reactivity. Therefore, future research should clarify, if it could also be valuable to include exercises with overall disgusting stimuli in the course of exposure therapy in children. There have been approaches to address disgust specifically in the course of exposure therapy in spider-phobic women. In a single published study De Jong et al. (2000) report that counterconditioning strategies targeting the disgusting properties of spiders did not improve effectiveness of exposure therapy in spider-phobic women. However, our results indicate that it might be that the associated aspects of spider phobia (i.e., disgust proneness) can be more easily addressed in younger patients. This should be addressed in future investigations.

Moreover, overall trait anxiety was also affected by exposure therapy, as STAI-C scores were significantly reduced in the therapy group at the second session. This might be interpreted as an expected generalization effect on overall fearfulness after exposure therapy. However, STAI-C scores significantly increased in the waiting-list group. It has to be noted that at no time no group reached STAI-C scores that point to pathologically elevated trait anxiety. Moreover, the main limitation of the current study is that fear pictures did not induce feelings of high arousal and fear. The reason for this was that pictures were selected to be adequate for children (e.g., that they contained no weapons, violence or in any way disturbing contents like natural catastrophes). Pictures showed attacking animals (e.g., sharks, dogs, lions) and were rated rather heterogeneously by children, possibly also reflecting a general interest in animals (or conversely, the lack of it). Therefore, it has to be questioned if an emotional examination of overall fear-inducing contents has sufficiently been triggered in the current study. Consequently, this fact leaves an interpretation of the changes in overall trait anxiety difficult.

Finally, one limitation of the current study has to be mentioned: due to the fact that only the EMG of the levator labii was assessed we cannot rule out that our data reflect a more general reduction in responsiveness of the facial muscles as a consequence of CBT. Therefore, future studies should include measurements from further facial muscle regions, for example the corrugator supercilii.

5. Conclusions

One-session exposure therapy is very powerful in the treatment of spider phobia in children and has effects on behavior as well as on disgust-specific electromyographic facial activity. Moreover, the results of the current investigation suggest that it might be useful to include exercises targeting disorder-specific and also overall disgust proneness in the course of exposure therapy. This topic should be more specifically addressed in future studies.

Role of the funding source

The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): Project-Number: P21379-B18.

Contributors

Anne Schienle designed the current paradigm, Verena Leutgeb adapted the study for children. Verena Leutgeb collected the data (diagnostics, therapy, EMG-sessions). She also managed the literature search and the statistical analyses. Anne Schienle supervised this work. Verena Leutgeb wrote the first draft of this manuscript. Both authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Both authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors kindly thank the children who participated in the present study. The research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): P21379-B18.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM IV-TR. [Google Scholar]

- Becker E.S., Rinck M., Türke V., Krause P., Goodwin R., Neumer S. Epidemiology of specific phobia subtypes: findings from the Dresden Mental Health Study. European Psychiatry. 2007;22:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley M.M., Lang P.J. Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisler J.M., Olatunji B.O., Lohr J.M. Disgust, fear, and the anxiety disorders: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong P.J., Muris P. Spider phobia: interaction of disgust and perceived likelihood of involuntary physical contact. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:51–65. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(01)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong P.J., Andrea H., Muris P. Spider phobia in children: disgust and fear before and after treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:559–562. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong P.J., Vorage I., van den Hout M.A. Counterconditioning in the treatment of spider phobia: effects on disgust, fear and valence. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong P.J., Peters M., Vanderhallen I. Disgust and disgust sensitivity in spider phobia: facial EMG in response to spider and oral disgust imagery. Anxiety Disorders. 2002;16:477–493. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P. Universals and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion. In: Cole J., editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation. University Press; Lincoln: 1971. pp. 207–283. [Google Scholar]

- Essau C.A., Conradt J., Petermann F. Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of specific phobia in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:221–231. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federer M., Margraf J., Schneider S. Leiden schon Achtjährige an Panik? Prävalenzuntersuchung mit Schwerpunkt Panikstörung und Agoraphobie. Zeitschrift für Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie. 2000;28:205–214. doi: 10.1024//1422-4917.28.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrikson M., Annas P., Fischer G., Wik P. Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00048-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes A.B.M., Uhl G., Alpers G.W. Spiders are special: fear and disgust evoked by pictures of arthropods. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2009;30:66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kindt M., Brosschot J.F., Muris P. Spider Phobia Questionnaire for Children (SPQ-C): a psychometric study and normative data. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:277–282. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P.J., Bradley M., Cuthbert B. Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida; Gainesville, Florida: 1999. International affective picture system. [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb V., Schäfer A., Schienle A. An event-related potential study on exposure therapy for patients suffering from spider phobia. Biological Psychology. 2009;82:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb V., Schäfer A., Köchel A., Scharmüller W., Schienle A. Psychophysiology of spider phobia in 8- to 12-year old girls. Biological Psychology. 2010;85:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchett G., Davey G.C.L. A test of a disease-avoidance model of animal phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1991;29:91–94. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(09)80011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merckelbach H., de Jong P.J., Arntz A., Schputen E. The role of evaluative learning and disgust sensitivity in the etiology and treatment of spider phobia. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;15:243–255. [Google Scholar]

- Mulkens S.A.N., De Jong P.J., Merckelbach H. Disgust and spider phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:464–468. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Merckelbach H., Collaris R. Common childhood fears and their origins. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:929–937. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P., Schmidt H., Merckelbach H. The structure of specific phobia symptoms among children and adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:863–868. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A., Mineka S. Fears, phobias, and preparedness: toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychological Review. 2001;108:483–522. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B.O., Cisler J., McKay D., Phillips M.L. Is disgust associated with psychopathology? Emerging research in the anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2010;175:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B.O., Huijding J., de Jong P.J., Smits J.A.J. The relative contributions of fear and disgust reductions to improvements in spider phobia following exposure-based treatment. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2011;42:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst L.G. One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;27:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchuk C.N., Lohr J.M., Westendorf D.H., Meunier S.A., Tolin D.F. Emotional responding to fearful and disgusting stimuli in specific phobics. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:1031–1046. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Stark R., Vaitl D. Evaluative conditioning: a possible explanation for the acquisition of disgust responses? Learning and Motivation. 2001;32:65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Walter B., Stark R., Vaitl D. Ein Fragebogen zur Erfassung der Ekelempfindlichkeit, FEE. [A questionnaire for the assessment of disgust sensitivity, QADS]Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie. 2002;31:110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Walter B., Stark R., Vaitl D. Brain activation of spider phobics towards disorder-relevant, generally disgust- and fear-inducing pictures. Neuroscience Letters. 2005;388:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Hermann A., Rohrmann S., Vaitl D. Symptom provocation and reduction in patients suffering from spider phobia: an fMRI study on exposure therapy. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;257:486–493. doi: 10.1007/s00406-007-0754-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schienle A., Schäfer A., Stark R., Vaitl D. Long-term effects of cognitive behavior therapy on brain activation in spider phobia. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009;172:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D., Edwards C.D., Lushene R.E., Montouri J., Platzek D. Consulting Psychologist Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1973. STAIC preliminary manual. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R., Walter B., Schienle A., Vaitl D. Psychophysiological correlates of disgust and disgust sensitivity. Journal of Psychophysiology. 2005;19:50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Straube T., Glauer M., Dilger S., Mentzel H.J., Miltner W.H.R. Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on brain activation in specific phobia. NeuroImage. 2006;29:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassinary L.G., Cacioppo J.T., Vanman E.J. The skeletomotor system: surface electromyography. In: Cacioppo J.T., Tassinary L.G., Berntson G.G., editors. Handbook of psychophysiology. 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2007. pp. 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Tolin D.F., Lohr J.M., Sawchuck C.N., Lee T.C. Disgust and disgust sensitivity in blood-injection-injury and spider phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:949–953. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unnewehr S., Schneider S., Margraf J. Springer; Berlin: 1995. Diagnostisches Interview beipsychischen Störungen im Kindes- und Jugendalter (Kinder-DIPS) [Google Scholar]

- Vernon L.L., Berenbaum H. Disgust and fear in response to spiders. Cognition and Emotion. 2002;16:809–830. [Google Scholar]

- Vrana S.R. The psychophysiology of disgust: differentiating negative emotional contexts with facial EMG. Psychophysiology. 1993;30:279–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb03354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody S.R., McLean C., Klassen T. Disgust as a motivator of avoidance of spiders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19:461–475. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]