Highlights

► Residue 2 in frog skin peptide aDrs can be enzymatically converted to a d-amino acid. ► The d-amino acid does not affect the kinetic parameters of aggregation. ► The diastereomers assemble to amyloids with different superstructural architectures. ► pH-triggered, melting of the amyloid is markedly altered by the d-amino acid.

Keywords: d-Amino acid, Bioactive peptide, Self-assembly, Functional amyloid, Posttranslational modification, Amphibian skin

Abstract

Amyloid fibrils are commonly observed to adopt multiple distinct morphologies, which eventually can have significantly different neurotoxicities, as e.g. demonstrated in case of the Alzheimer peptide. The architecture of amyloid deposits is apparently also determined by the stereochemistry of amino acids. Post-translational changes of the chirality of certain residues may thus be a factor in controlling the formation of functional or disease-related amyloids.

Anionic dermaseptin (aDrs), an unusual peptide from the skin secretions of the frog Pachymedusa dacnicolor, assembles to amyloid-like fibrils in a pH-dependent manner, which could play a functional role in defense. aDrs can be enzymatically converted into the diastereomer [d-Leu2]-aDrs by an l/d-isomerase. EM and AFM on fibrils formed by these isomers have shown that their predominant morphology is controlled by the stereochemistry of residue 2, whereas kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of aggregation are barely affected. When fibrils were grown from preformed seeds, backbone stereochemistry rather than templating-effects apparently dominated the superstructural organization of the isomers. Interestingly, MD indicated small differences in the conformational propensities between the isomers.

Our results demonstrate how d-amino acid substitutions could take active part in the formation of functional or disease-related amyloid. Moreover, these findings contribute to the development of amyloid-based nanomaterials.

Introduction

It is quite evident that the self-assembly of polypeptides to higher order structures relies on the chiral properties of their building blocks, the amino acids. This applies accordingly to amyloid, a highly ordered oligomeric state of polypeptides, which is characterized by a cross-β sheet structure [1–3]. Several structures have been proposed, which are consistent with this motif. In the most simple case, the underlying structure could be β-sheet tapes, which exhibit a left-handed twist in the fiber direction and perpendicular to the polypeptide strands due to the l-chirality of naturally occurring amino acids [4]. This example clearly underscores that the structural organization of supermolecular structures such as amyloid is determined in a decisive manner by the apparent homochirality of protein biochemistry. A few cases, however, have been demonstrated where a d-amino acid is enzymatically incorporated into animal peptides at a well-defined position [5,6], albeit always close to the termini. To date, in all vertebrate and several invertebrate peptides the d-amino acid is the second residue of the mature product. This stereo-inversion can have drastic consequences on receptor interactions as e.g. in dermorphins and deltorphins where the all l-forms lack opioid activity. More subtle differences between the two isomeric species have been reported for other cases. In particular, in bombinins H, antimicrobial peptides from the skin of fire-bellied toads, the d-residue substitution modulates the folding propensity under conditions, which promote self-aggregation [7,8]. Many more diastereomeric peptides probably exist, yet may have gone unnoticed due to the difficult analytics [9,10]. After all, it is a justified and interesting question, whether an enzymatically insertable d-amino acid could have consequences on the amyloid-like structures formed by natural peptides.

Strikingly, amyloid is involved in over 20 disease states, which include the neurodegenerative disorders Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease and numerous amyloidoses [1,11–13]. By contrast, a few cases of diverse functional roles for amyloid in biology have been shown to date [1,14,15], and most recent results even add support to the notion of an integrate role of amyloid in innate immunity [16–24]. In this respect, the antimicrobial activity of the otherwise disease-associated Aβ peptide is worth being mentioned [25]. Another example of an amyloid structure involved in innate immunity may be peptide aDrs2 from the skin of the Mexican tree frog (Pachymedusa dacnicolor), albeit one where the amyloid, assembled form is a deposit form rather than the active form [17]. We suspect that aDrs could also exist in a diastereomeric form naturally, since the processed N-terminus of aDrs matches the consensus of a modifying l/d-isomerase and, furthermore, an aDrs-derived model peptide was positive in our assay [26]; enzymes of this kind must be present in the skin secretions as d-amino acid containing peptides (i.e., [Ile2]-deltorphin and dermorphin) also were observed in this source [27]. Whenever amyloid participates in physiological processes, the inherent danger of the detrimental accumulation of aggregates requires a tight regulation of its formation [28,29]. It is therefore tempting to speculate that the d-residue could represent a smart means to control amyloid formation.

Here, we used aDrs peptide as a model of amyloid generation with the aim to explore the regulatory potential of an enzymatic d-amino acid substitution at residue Leu-2. We report the consequences of this d-amino acid substitution on the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of aggregation and the superstructural organization of the resulting amyloid.

Material and methods

Peptide synthesis and preparation of amyloidous gels

All peptides were prepared by solid-phase peptide synthesis and provided by Peptide Specialty Laboratories (Heidelberg, Germany). The peptides were purified by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using a 0.1% (v/v) HCl-acetonitrile gradient solvent system. Peptide (monomeric) stock solutions (10 mg/ml, pH 8.0) were adjusted to pH 3.0 with a defined volume of diluted HCl and incubated for at least 7 days.

Thioflavin T (ThT) assay

ThT stock solution (0.08 % (w/v) ThT in 0.1 N HCl) was added to peptide samples at the desired pH for fluorescence measurement (excitation at 440 nm, emission 482 nm, slitwidth 10 nm).

Fourier transform-infra red spectroscopy (FTIR)

Hydrogen exchange of the peptides was performed by repeated dissolution in D2O and lyophilization at a neutral pD. Peptide samples were dissolved in DCl/D2O to a final concentration of 2 mM and allowed to aggregate.

All spectra were collected at room temperature on a Bruker spectrometer (model Tensor 27) as previously described [7]. The amide I’ region (1600–1700 cm−1) of the sample spectrum was examined [30]. Prior to curve fitting, peaks resulting from water vapor were interactively removed and a 13-point Savitsky-Golay smoothing filter was applied. A straight baseline passing through the ordinates at 1600 and 1700 cm−1 was subtracted. Second-derivative spectra were calculated in order to identify peak positions. The contributions of the individual peaks were estimated by fitting Gauss peaks at the most likely band assignments. Secondary structure was correlated to band frequencies according to [31].

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Peptide samples were spotted on carbon coated formvar covered copper grids (Ager Scientific), negatively stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate (Electron Microscope Sciences) and examined with a Jeol 2010 electron microscope operated at 100 kV.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM)[32]

Peptide samples were spotted on freshly cleaved mica, cleaned silicon wafer (EtOH, H2O) or plasma cleaned carbon coated formvar covered copper grid and excess sample solution was removed with filter paper. AFM measurements were performed with a Nanoscope V multimode (Bruker, Santa Barbara, CA) with a J-scanner (nominal scan size 130 μm) in Tapping Mode. Measurements in liquid were performed at room temperature in 5 mM ammoniumacetate buffer, pH 6.25, or 100 mM NaCl with oxide sharpened silicon nitrite cantilevers (NP-S, Veeco NanoProbe, USA) with nominal spring constants of around 0.1 N/m and resonance frequencies between 14 and 26 kHz. Measurements in air were performed at room temperature with doped silicon pointprobes (Nanosensors, Switzerland) with nominal spring constants of 28–76 N/m and resonance frequencies between 295 and 410 kHz. The samples were scanned at approximately 1 Hz, the measured scan size varied from 20 μm to 500 nm. The tapping amplitude during imaging was set to 90% of the free vibrating amplitude of the cantilever.

Polarized light microscopy

Gels (10 mg/ml) were examined for birefringence with a light microscope (Olympus) under the crossed polarizers of the differential contrast device using a DPlanApo 40 objective.

Seeding experiments

For the preparation of seeds, preformed gels (10 mg/ml) were diluted 10-fold into a glass-vial and sonicated in a Elmasonic S water bath (Elma, Singen, Germany). Alternatively, for the preparation of seeds consisting of amorphous granules, preformed gels (10 mg/ml) were adjusted to pH 6.25 with ammoniumacetate buffer, incubated for 45 min and sonicated briefly, because in [d-Leu2]-aDrs samples a precipitate was clearly visible at this time. Monomeric stock solutions (1 mg/ml) were adjusted to pH 3.0 with a defined volume of diluted HCl and seeds were immediately added (1/9 of the volume). Samples were incubated for 20 h, which was definitely shorter than the lag-period in the absence of seed, and subjected to TEM or AFM analysis.

Molecular dynamics simulation

The conformational properties of two stereoisomeric peptides (in the following denoted as LLGD, and LL’GD), which represent the N-terminal tetrapeptides of aDrs and [d-Leu2]-aDrs, were investigated by atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulation using the GROMOS11 package of programs [33]. The program MOE [34] was used to build initial extended-chain structures of the peptides. The N-terminus and the side chain of residue Asp-4 were protonated (corresponding to a pH value <4), while the C-terminus was capped with a N-methylamide group. The peptides were described using the 54A7 force-field parameter set, [35] and water was represented by approximately 2080 copies of the three-site simple-point-charges water (SPC) model [36]. The systems were simulated at a constant pressure of 1 atm and a constant temperature of 298.15 K.

The MD trajectories pertaining to production runs of 29.8 ns length were analyzed with the gromos++ package of programs [37]. This involved the determination of backbone dihedral angle probability distributions and the monitoring of intrasolute hydrogen bonding. Further details concerning the performed simulations and analyses are provided in the Supplemental section.

Results and discussion

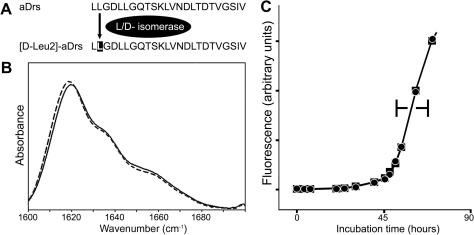

Here, we present our study on the effect of an inversion of backbone stereochemistry in the second N-terminal position on the self-assembly of aDrs peptide (Fig. 1). Thereby diastereomers are generated; their properties, unlike that of all d-peptides [38–40] (which represent enantiomers), may differ from those of the parent peptide. On the other hand, no secondary structure elements are disrupted here as it is, for example, the case in some age-induced diastereomers of Aβ [41,42]. Both aDrs and [d-Leu2]-aDrs assemble to thioflavin T- and congo-red-positive amyloid-like aggregates at acidic pH (data not shown). Their FTIR spectra are dominated by a peak with a maximum at 1620 cm−1, which is in agreement with the tight inter-chain hydrogen-bonds characteristic of amyloid. A close comparison of the FTIR spectra revealed no obvious significant differences between the isomers (Fig. 1) and suggested that variations, if any, do not occur at the bulk secondary structural level. This outcome was not quite unexpected as the substitution site is located peripherally and, furthermore, distantly from the aggregation-prone sequence, which is contained within the C-terminal segment 13-24 (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison between peptides aDrs and [d-Leu2]-aDrs. (A) Sequences and enzymatic interconversion. Inverted characters within a sequence denote a d-amino acid. (B) Overlay of FTIR spectra of amyloidous gels formed by aDrs (dotted line) and [d-Leu2]-aDrs (solid line). (C) Aggregation kinetics of aDrs (■) and [d-Leu2]-aDrs (●). Upon a decrease in pH, ThT-fluorescence was recorded over time.

Kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of aggregation

The kinetics of amyloid formation is commonly characterized by a lag period. This parameter results from the formation of a high-energy nucleation core as a prerequisite for fibril growth. Examination of both the duration of the lag period as well as the speed of fibril growth of aDrs isomers did not reveal any effect of the d-residue (Fig. 1). Moreover, we determined the so-called critical concentration (equlibrium concentration of monomer under dialysis conditions and lowest concentration where filaments are observed) to be 5 μM for both isomers. A potential natural strategy for the regulated formation of functional amyloid would probably have targeted these parameters. Indeed, several cases of functional amyloid involve components, which exert unusual lag phases. For instance, the kinetics of aggregation by fragment rMα of Pmel17, a major component of mammalian melanosomes, is highly accelerated in comparison to Aβ (amyloid β) and proceeds without obvious lag phase in order to avoid the prolonged presence of toxic polymerization intermediates [16]. Another example is the triggered fibrillization of CsgA, which for itself has an extraordinary long lag period and requires CsgB as a nucleator in the biosynthesis of amyloidous curli [43].

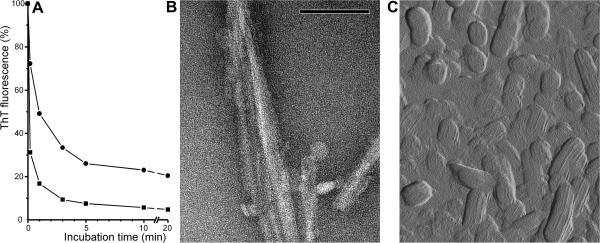

More parameters arise from the aDrs-specific pH-dependent reversal of aggregation, which, however, is not commonly observed among amyloid species. Thereby, upon a shift in pH to above pH 5, the amyloid fibrils quickly disassemble in a cooperative manner due to electrostatic repulsion between deprotonated aspartic acid residues [17]. In the diastereomeric form, the kinetics of this process is markedly altered (Fig. 2), whereas the transition-pH remains unaffected by the d-residue (data not shown). In the course of the ‘melting’ of both aDrs and [d-Leu2]-aDrs, ‘backward’ granular aggregates, 10–500 nm in size, are transiently formed within the transition interval (pH 5–6.5) (Fig. 2). These have a residual capability to bind ThT, which is thought to intercalate into hydrophobic ridges along the fibrils [17]. Therefore, the observed differences in the base-level fluorescence between the diastereomers also reflect different degrees of aligned structures within those apparently amorphous structures. Indeed, AFM directly reveals a striated surface texture even in late globular aggregates (Fig. 2). However, despite their fibril-like appearance, the early metastable amorphous structures do not have the capability to seed fibril formation, which is a clear argument against a possible amyloidic nature. Interestingly, these aggregates are highly cytotoxic and thus can serve as an agent against eukaryotic offenders as active components of the innate immune system.

Fig. 2.

Disaggregation of amyloid in response to a pH-increase. (A) Kinetics of amyloid formed by aDrs (■) and [d-Leu2]-aDrs (●). Amyloidous gels were grown in absence of ThT and after addition of ThT fluorescence was recorded over time upon a decrease in pH. Reproducability of the plots was within ±10% (absolute). (B) Negative stain TEM of [d-Leu2]-aDrs fibrils coexisting with amorphous aggregates after 1 h incubation without ThT at pH 6.25. In control experiments, aDrs fibrils could no longer be observed at this time. Scale bar, 100 nm. (C) AFM amplitude error image of [d-Leu2]-aDrs ‘amorphous’ aggregates after 1.5 h incubation without ThT at pH 6.25 in solution reveals a striated surface tecture. Sampling size 1.57 × 1.90 μm.

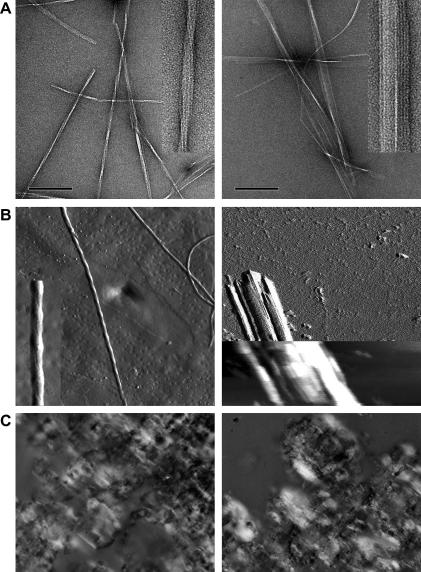

Morphological differences between isomers

Furthermore, morphological differences were obviously present between higher order structures formed by the different isomers. The predominant morphology for aDrs were rope-like fibrils with a periodic twist of h = 330 nm built up by protofilaments of a = 4.5 nm. By contrast, [d-Leu2]-aDrs exclusively formed sheet-like stacks of protofilaments with no explicit twist (Fig. 3). AFM revealed a predominant thickness of d = 9 nm for these stacks, which is consistent with two layers of protofilaments. We never observed rope-like structures in [d-Leu2]-aDrs samples. This fundamental difference in superstructural organization, in particular the different tendency to associate laterally into aligned filamentous multimers (crystallites), is also reflected in the microscopic appearance under linearly polarized light (as depicted in Fig. 3). Consistently, the [d-Leu2]-aDrs samples were characterized by a high content of large crystallites.

Fig. 3.

Morphological differences between amyloid formed by the aDrs isomers. (A) Negative stain TEM images and (B) AFM amplitude error images predominanly reveal rope-like fibrils for aDrs amyloidous gel (left panels) and a sheet-like morphology for [d-Leu2]-aDrs (right panels). Height image (B, insert, right panel) of the sheet-like crystallites reveales a predominant thickness of d = 9 nm, which is consistent with 2 layers of protofilaments. TEM scale bar, 200 nm, insert 2.5×. AFM sampling size 2 μm, insert 2.5× (left panel), and 1 μm, insert 2× (right panel). (C) Polarized light microscopy indicates a different tendency for lateral association into sheet-like crystallites between aDrs (left panel) and [d-Leu2]-aDrs (right panel).

Polymorphism phenomena seem to be a frequent attribute of amyloid-forming peptides and switching between different superstructures is frequently observed [44]. Aβ(1–40), for example, predominantly forms either fibrils with a periodic twist (50- to 200-nm period) or filaments with no resolvable twist but laterally associated to dimers or multimers in dependence of whether mechanical stress is applied [45]. A similar behavior has been described for the insulin B-chain [46] and other peptides [44]. Most interestingly, different mature fibril morphologies may result in different neurotoxic properties, a finding of general importance with far-ranging implications. In particular, the toxicity of “quiescent” Aβ(1–40) rope-like fibrils was reported to be significantly higher than that of the agitated untwisted species [45]. Inconveniently, the pH-instability of aDrs fibrils prevented an experimental investigation in this case.

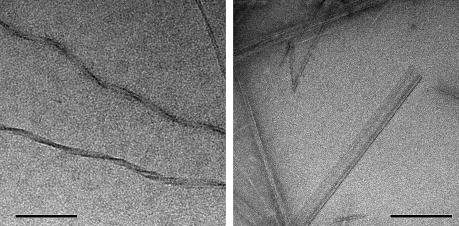

Inheritance of superstructure morphologies

Next we were interested to see whether the respective superstructure morphologies would be inheritable as it is observed for several amyloids and prion strains [44,45,47,48]. Seeding of aDrs or [d-Leu2]-aDrs with preformed fibrils of either morphology diminished the lag period by obviously acting as nucleators. No gels were formed in control experiments without seeds. Furthermore, aDrs peptide could act as nucleator for the polymerization of [d-Leu2]-aDrs, and vice versa. The morphology, however, was not inherited to the daughter superstructures under our experimental conditions, which were largely dictated by the pH-profile of fibrillation (Fig. 4). Instead, the stereochemistry of the monomers apparently determined the predominant morphology. This fact indicates that in this case the inherent thermodynamic preference cannot be overcome by templating as opposed to by inheritance effects observed for other peptides such as Aβ(1–40) [45]. These are apparently less determined in the selection of the superstructures and do inherit their morphology. Nevertheless, the polymorphism of Aβ(1–40) superstructures is due to, or at least accompanied by, structural differences at the molecular level as evidenced by solid-state NMR [45]. Noteworthy, Aβ(1–40) contains several Glys throughout the sequence. Gly can, as a matter of fact, rather freely assume Φ, Ψ values typical of both l- and d-amino acids [49]. In the enkephalins, for example, Glys can indeed substitute for the d-residue present in the frog opioid peptides. We were therefore interested to see whether in the aDrs system a certain superstructure could be stereochemically ‘locked in’ by the complementary rotamers of the bulky Leu-2 enantiomers. In the MD simulations in explicit water, the backbone conformational distributions p(Φ) and p(Ψ) of the stereoisomeric N-terminal tetrapeptides LLGD and LL’GD were found to be rather similar, except for small differences in peak heights for p(Φ) of residue Gly-3, as well as peak positions and heights for p(Ψ) of residue Asp-4 (Fig. S4). In both peptides, the Φ-torsion of the latter residue sampled predominantly conformational ensembles indicative of β-strand like (shoulder at 243°) or PII-like (peak at 291°) secondary structure motives. However, the Ψ-torsion of residue Asp-4 revealed predominantly conformational ensembles indicative of β-strand like conformations (peak at 132°) for peptide LLGD, or PII-like (peak at 149°) secondary structure motives in peptide LL’GD (Fig. 5). Moreover, the simulation of peptide LLGD presented a backbone hydrogen bond between residues Asp-4 (backbone amide hydrogen atom) and Leu-2 (backbone carbonyl oxygen atom) with an occurrence of 15.1%, while this hydrogen bond occurred in only 6.3% of the simulation of peptide LL’GD. The relevance of these findings, which were derived from a simulated water environment, for the higher-order superstructures formed by the peptides in their amyloid state, cannot be proven yet; however, it is a striking fact that polyproline type II helices are also suspected to be of importance in amyloidogenesis [50]. Further simulations will be necessary to show whether it is indeed the conformation of the N-terminal segment, which crucially affects fibril twist and thus the resulting superstructure.

Fig. 4.

Morphology of amyloid formed by the aDrs isomers cross-seeded with preformed fibrils as revealed by negative stain TEM. Monomeric aDrs solution was brought to pH 2 and sonicated fibrils from the [d-Leu2]-aDrs sample in Fig. 3 served as parent (left panel), whereas [d-Leu2]-aDrs was seeded with aDrs fibrils (right panel). Scale bar, 200 nm.

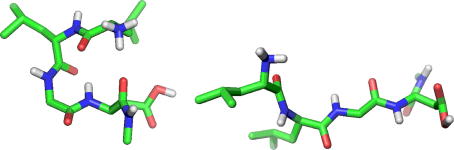

Fig. 5.

Structures from MD simulation of the tetrapeptide H3N+–Leu–Leu–Gly–Asp–NH–CH3 with residue Leu-2 either in the l- (left structure) or d- (right structure) form. The structures are representatives of conformational differences between the two peptides as observed in the sampled configurational ensembles. The all-l structure corresponds to a trajectory frame sampled at 12.024 ns and shows backbone hydrogen bonding between residues Asp-4 (backbone amide hydrogen atom) and Leu-2 (backbone carbonyl oxygen atom). The [d-Leu2]-stereoisomer corresponds to a trajectory frame sampled at 12.720 ns and shows PII-like backbone torsions for residue Asp-4. Figures were generated using the pymol program [55].

It is an interesting fact that several other natural aggregation-prone peptides are candidates for a stereoisomerization by a l/d-isomerase, of which genes are present throughout the species up to man. These include the insulin B-chain and, most interestingly, ovCNP, a C-type II member of the natriuretic peptide-family from the venom of male platypus, a primitive mammal [51], for which the existence of the diastereomeric form has been experimentally demonstrated [52]. CNP is situated in the context of atrial amyloidosis and explicitly shares with several other amyloidogenic peptides the ability to assemble to ion-selective pores within bilayers [53]. The role of the d-residue in any of these processes is however unclear.

Conclusion

Our study on the effect of a stereochemical modification on aDrs aggregation revealed interesting aspects of superstructural organization and polymorphism, which is in the focus of current research. In fact, this modification results in a fundamental change in superstructural organization, which is particularly remarkable considering that the site of stereoinversion is not localized within the aggregation-prone sequence and, furthermore, this modification can be enzymatically introduced. Therefore, our results could not only contribute to the understanding of natural strategies to control protein aggregation in cases where amyloid with its unique properties is a functional, integrated component of the organism, but also could provide conceptual clues about the pathogenesis of protein deposition disorders, i.e., certain neurodegenerative diseases or amyloidoses. There, the differential toxicity of superstructure morphologies is certainly important, and cross-seeding effects are thought to be crucially involved in the complex development of such pathological states [54]. Moreover, a superstructural switch might be a valuable feature when implemented into amyloid-based nanomaterials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professors Günther Kreil (Salzburg) and Christian Obinger (Wien) for helpful suggestions and Professor Heinz Falk (Linz) for useful comments on linear dichroism. We gratefully acknowledge the expertise of Klaus Haselgrübler (CNSA, Linz) and Dr. V.C. Barroso (Institute of Polymer Science, Linz). We thank the Anton Paar GmbH – Austria for the support. This work was supported by the Austrian science fund FWF grants P19393 and P22782 (A.J.).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: aDrs, anionic dermaseptin; ThT, thioflavin T; PII, polyproline type II helix.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Chiti F., Dobson C.M. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:333–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.123901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin N., Perugia E., Wolf S.G., Klein E., Fridkin M., Addadi L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4242–4248. doi: 10.1021/ja909345p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toyama B.H., Weissman J.S. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011;80:557–585. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-090908-120656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson J.S. Adv. Protein Chem. 1981;34:167–339. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60520-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreil G. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997;66:337–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jilek A., Kreil G. Chem. Monthly. 2008;139:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zangger K., Gößler R., Khatai L., Lohner K., Jilek A. Toxicon. 2008;52:246–254. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozzi A., Mangoni M.L., Rinaldi A.C., Mignogna G., Aschi M. Biopolymers. 2008;89:769–778. doi: 10.1002/bip.21006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai L., Sheeley S., Sweedler J.V. Bioanal. Rev. 2009;1:7–24. doi: 10.1007/s12566-009-0001-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scaloni A., Simmaco M., Bossa F. Methods Mol. Biol. 2003;211:169–180. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-342-9:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sipe J.D. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1992;61:947–975. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.004503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pepys M.B. Annu. Rev. Med. 2006;57:223–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skovronsky D.M., Lee V.M., Trojanowski J.Q. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2006;1:151–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowler D.M., Koulov A.V., Balch W.E., Kelly J.W. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maji S.K., Perrin M.H., Sawaya M.R., Jessberger S., Vadodaria K., Rissman R.A., Singru P.S., Nilsson K.P., Simon R., Schubert D., Eisenberg D., Rivier J., Sawchenko P., Vale W., Riek R. Science. 2009;325:328–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1173155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang H., Arce F.T., Mustata M., Ramachandran S., Capone R., Nussinov R., Lal R. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1775–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gößler-Schöfberger R., Hesser G., Muik M., Wechselberger C., Jilek A. FEBS J. 2009;276:5849–5859. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Code C., Domanov Y.A., Killian J.A., Kinnunen P.K. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:1064–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H., Sood R., Jutila A., Bose S., Fimland G., Nissen-Meyer J., Kinnunen P.K. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:1461–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao H., Tuominen E.K., Kinnunen P.K. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10302–10307. doi: 10.1021/bi049002c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auvynet C., El Amri C., Lacombe C., Bruston F., Bourdais J., Nicolas P., Rosenstein Y. FEBS J. 2008;275:4134–4151. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kagan B.L. Biophys. J. 2011;100:1597–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris F., Dennison S.R., Phoenix D.A. Curr. Chem. Biol. 2011;5:142–153. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kagan B.L., Jang H., Capone R., Teran Arce F., Ramachandran S., Lal R., Nussinov R. Mol. Pharm. 2011;9:708–717. doi: 10.1021/mp200419b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soscia S.J., Kirby J.E., Washicosky K.J., Tucker S.M., Ingelsson M., Hyman B., Burton M.A., Goldstein L.E., Duong S., Tanzi R.E., Moir R.D. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A. Jilek, C. Mollay, K. Lohner, G. Kreil, Amino Acids. (2011) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007s00726-00011-00890-00726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Wechselberger C., Severini C., Kreil G., Negri L. FEBS Lett. 1998;429:41–43. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00545-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fowler D.M., Koulov A.V., Alory-Jost C., Marks M.S., Balch W.E., Kelly J.W. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith A.M., Scheibel T. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2010;211:127–135. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byler D.M., Susi H. Biopolymers. 1986;25:469–487. doi: 10.1002/bip.360250307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson M., Mantsch H.H. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995;30:95–120. doi: 10.3109/10409239509085140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stine W.B., Jr., Snyder S.W., Ladror U.S., Wade W.S., Miller M.F., Perun T.J., Holzman T.F., Krafft G.A. J. Protein Chem. 1996;15:193–203. doi: 10.1007/BF01887400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmid N., Christ C.D., Christen M., Eichenberger A.P., van Gunsteren W.F. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2012;183:890–903. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The molecular operating environment (MOE), Chemical Computing Group, Inc., 2009.

- 35.Schmid N., Eichenberger A.P., Choutko A., Riniker S., Winger M., Mark A.E., van Gunsteren W.F. Eur. Biophys. J. 2011;40:843–856. doi: 10.1007/s00249-011-0700-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., van Gunsteren W.F., Hermans J. In: Interaction Models for Water in Relation to Protein Hydration. Pullman B., editor. Reidel Dordrecht; The Netherlands: 1981. pp. 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eichenberger A.P., Allison J.R., Dolenc J., Geerke D.P., Horta B.A.C., Meier K., Oostenbrink C., Schmid N., Steiner D., Wang D., van Gunsteren W.F. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:3379–3390. doi: 10.1021/ct2003622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cribbs D.H., Pike C.J., Weinstein S.L., Velazquez P., Cotman C.W. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:7431–7436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wadai H., Yamaguchi K., Takahashi S., Kanno T., Kawai T., Naiki H., Goto Y. Biochemistry. 2005;44:157–164. doi: 10.1021/bi0485880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esler W.P., Stimson E.R., Fishman J.B., Ghilardi J.R., Vinters H.V., Mantyh P.W., Maggio J.E. Biopolymers. 1999;49:505–514. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199905)49:6<505::AID-BIP8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaneko I., Morimoto K., Kubo T. Neuroscience. 2001;104:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kubo T., Nishimura S., Kumagae Y., Kaneko I. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;70:474–483. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapman M.R., Robinson L.S., Pinkner J.S., Roth R., Heuser J., Hammar M., Normark S., Hultgren S.J. Science. 2002;295:851–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1067484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fändrich M., Meinhardt J., Grigorieff N. Prion. 2009;3:89–93. doi: 10.4161/pri.3.2.8859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petkova A.T., Leapman R.D., Guo Z., Yau W.M., Mattson M.P., Tycko R. Science. 2005;307:262–265. doi: 10.1126/science.1105850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dzwolak W., Smirnovas V., Jansen R., Winter R. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1927–1932. doi: 10.1110/ps.03607204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chien P., Weissman J.S., DePace A.H. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:617–656. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamaguchi K., Takahashi S., Kawai T., Naiki H., Goto Y. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;352:952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fraternali F., Anselmi C., Temussi P.A. FEBS Lett. 1999;448:217–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blanch E.W., Morozova-Roche L.A., Cochran D.A., Doig A.J., Hecht L., Barron L.D. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;301:553–563. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Plater G.M., Martin R.L., Milburn P.J. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Pharmacol. Toxicol. Endocrinol. 1998;120:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0742-8413(98)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torres A.M., Menz I., Alewood P.F., Bansal P., Lahnstein J., Gallagher C.H., Kuchel P.W. FEBS Lett. 2002;524:172–176. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kourie J.I., Culverson A.L., Farrelly P.V., Henry C.L., Laohachai K.N. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2002;36:191–207. doi: 10.1385/CBB:36:2-3:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lundmark K., Westermark G.T., Olsen A., Westermark P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6098–6102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501814102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The PyMOL molecular graphics system, DeLano, W.L., <http://www.pymol.org>, 2002.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.