Abstract

Oxidative stress is thought to be involved in the development of behavioral and histopathological alterations in animal models of psychosis. Here we investigate the causal contribution of reactive oxygen species generation by the phagocyte NADPH oxidase NOX2 to neuropathological alterations in a rat model of chronic psychosocial stress. In rats exposed to social isolation, the earliest neuropathological alterations were signs of oxidative stress and appearance of NOX2. Alterations in behavior, increase in glutamate levels and loss of parvalbumin were detectable after 4 weeks of social isolation. The expression of the NOX2 subunit p47phox was markedly increased in pyramidal neurons of isolated rats, but below detection threshold in GABAergic neurons, astrocytes and microglia. Rats with a loss of function mutation in the NOX2 subunit p47phox were protected from behavioral and neuropathological alterations induced by social isolation. To test reversibility, we applied the antioxidant/NOX inhibitor apocynin after initiation of social isolation for a time period of 3 weeks. Apocynin reversed behavioral alterations fully when applied after 4 weeks of social isolation, but only partially after 7 weeks. Our results demonstrate that social isolation induces rapid elevations of the NOX2 complex in the brain. Expression of the enzyme complex was strongest in pyramidal neurons and a loss of function mutation prevented neuropathology induced by social isolation. Finally, at least at early stages, pharmacological targeting of NOX2 activity might reverse behavioral alterations.

Keywords: apocynin, behavior, brain, parvalbumin, psychosis, social isolation

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that psychosocial stress leads to oxidative stress in the brain, thereby contributing to the development of mental disorders such as anxiety and psychosis.1 Data from psychotic patients have shown a key role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of mental disorders (reviewed in Yao and Ravinder2).

NOX enzymes are proteins that transfer electrons across biological membranes to catalyze the reduction of molecular oxygen and generate the superoxide anion O2−.3 In the central nervous system, NOX isoforms are heterogeneously distributed in different regions and cell types,4 and thought to be involved in redox regulation of cell fate and neuronal activity.5 From a pathological point of view, NOX enzymes have been implicated in the generation of oxidative stress seen in a variety of brain disorders, from psychiatric to neurodegenerative diseases.4

Some progress in the understanding of the mechanistic link between oxidative stress and psychiatric diseases has come from animal models. In the ketamine-induced model of psychosis,6 we and others have previously shown that NOX2 is a major source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the brain, controlling glutamate release and behavioral alterations,7, 8 and that decrease of parvalbumin in GABAergic neurons is prevented by NOX2 deficiency and by the treatment with the antioxidant/NOX inhibitor compound apocynin.8, 9, 10

The social isolation rearing of young adult rats is defined as a model of chronic psychosocial stress11, 12 and provides a non-pharmacological tool to study long-term alterations reminiscent of several symptoms seen in schizophrenic patients.13 These include hyper-reactivity to novel environments,14 cognitive impairment15 as well as decrease in parvalbumin-positive neurons.16 We previously described a possible involvement of NOX2 in isolation-induced neuropathology.17 However, in the absence of NOX2 knockout rats and specific NOX2 inhibitors, causal relationships have not yet been established and the possibility that NOX2 activation is a late epiphenomenon could not be excluded.

A natural polymorphism of the Ncf1 gene controlling NOX2-dependent ROS has recently been reported in wild rats and in inbred laboratory strains.18, 19 Importantly, a one nucleotide difference determines the functional effects. Indeed, DA.Ncf1DA rats with lower capacity for ROS production18, 20 differ only at the Ncf1 locus from the congenic strain DA.Ncf1E3 coding for the p47phox protein, which is an essential component of the NOX2/NADPH oxidase complex, and a methionine instead of a threonine at position 153 reduces the capacity of oxidative burst by 40%.20 For simplicity we will refer to this polymorphism throughout the text as ‘loss-of-function mutation'.

Dysfunctions of cortical glutamatergic neurotransmission are observed in schizophrenic patients and in animal models of schizophrenia,21 and thought to be involved in the development of behavioral alterations.22 These dysfunctions are reflected by an increased cortical release of glutamate with consequent alterations in the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor.23 More specifically, the subunit 2A of the receptor is the most affected.24

Here, we have investigated the role of NOX2 in the development of the neuropathology induced by social isolation. Using time-course analysis, animals with NOX2 loss of function mutation as well as pharmacological tools, we demonstrate a crucial role of NOX2 in this experimental model of psychosis.

Materials and methods

Note that for space reasons, details are provided in Supplementary Materials and methods. Also, behavioral tests and immunohistochemical/western blot assays were performed on the same sets of animals.

Animals

A total number of 30 wistar (Harlan, S Pietro al Natisone, Udine, Italy), 10 DA (with the ROS low-responder Ncf1DA allele) and 10 DA.Pia4 (with the ROS high-responder Ncf1E3 allele) dams provided offspring for inclusion in the study. For simplicity, DA.Pia4 rats and DA rats will be indicated as Ncf1E3 and Ncf1DA, respectively. The Ncf1E3 and Ncf1DA rats were from the Medical Inflammation Research animal house, Karolinska Institute (Stockholm, Sweden).

Animals were housed as described previously.17 This study was performed in conformity with ethical guidelines, and national and international laws.7, 17

Details regarding genotyping of animals are provided in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Social isolation protocol

The social isolation procedure was performed on male rats, as described previously.17

The experimental protocol lasted 2, 4 or 7 weeks for wistar rats and 7 weeks for Ncf1E3 and Ncf1DA rats.

Details are provided in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Apocynin treatment

Animals were firstly exposed to behavioral tests after 4 or 7 weeks of social isolation. Then, control and isolated rats received approximately 5 mg/kg per day of apocynin (Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland)8, 17, 25 in drinking water from week 4 to week 7 (protocol 1, n=6 controls and 6 isolated) or from week 7 to week 10 (protocol 2, n=6 controls and 6 isolated). Behavioral tests were repeated at the end of each protocol.

Behavioral tests

Open field test

The open field test was performed as described previously.17, 26, 27

Details are provided in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Novel object recognition test

The novel object recognition test was performed as described previously.17, 28, 29, 30 The discrimination index was calculated using the following formula: (N−F)/(N+F) (N=time spent in exploration of the novel object during the choice trial; F=time spent in exploration of the familiar object in the choice trial).31

Details are provided in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Microdialysis

Intracerebral microdialysis in awake freely moving rats was performed as described previously.7, 30 A vertical probe was positioned in the medial prefrontal cortex of rats: AP +3.7 mm from bregma, L ±0.7 mm from midline and DV −2.8 from dura.32, 33 Three baseline samples were collected to evaluate cortical basal levels of glutamate.

Details are provided in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Quantification of glutamate in the dialysate

Glutamate concentrations were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography as described previously.8, 34 Details are provided in Supplementary Materials and methods.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis were performed as described previously,7, 17 using monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies against 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG; 1:10; JaICA, Shizuoka, Japan), parvalbumin (1:1000; Calbiochem, Zug, Switzerland), p47phox (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), GAD67 (1:2000; Chemicon, Zug, Switzerland) glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:4000; Chemicon), ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA-1) (1:500; Wako, Neuss, Germany) and CD68 (1:100; AbD Serotec, Dusseldorf, Germany). Fluorescence images were obtained using an epifluorescence system. Merged images of single fluorescence channels were obtained using the AxioVision Rel. 4.5 software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Specificity of the antibody against p47phox was tested comparing the staining obtained on the spleen and brain tissues of wild-type and p47phox knockout mice (kindly provided by Prof. Ralph Brandes, Faculty of Medicine, Goethe-University, Frankfurt, Germany) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Quantifications of immunohistochemistry have been performed using the Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Biberach an der Riss, Germany).

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously,18 using polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies against c-fos (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-JNK (1:200; Cell Signaling, Allschwil, Switzerland), JNK (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-ERK (1:200; Cell Signaling), ERK (1:200; Cell Signaling), phospho-p38 (1:1000; Cell Signaling) and p38 (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), IBA-1 (1:1000; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), NOX2 (1:1000; Biosciences Pharmingen, Erembodegem, Belgium), parvalbumin (1:4000; kindly provided by Professor Do Kim, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland), calretinin (1:1000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), NMDA receptor subunit 2A (1:500; Abcam), NMDA receptor subunit 2B (1:500; Abcam), p47phox (1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GAD67 (1:1000; Chemicon) and α-actin (1:4000; Sigma-Aldrich). Optical densities of the bands were measured using the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) and normalized with α-actin.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction methods, and primer and product size have been described previously.17, 35

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the Sigma Stat 3.1 software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The statistical tests are indicated in the figure legends. For all tests, a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are expressed as means±standard error (s.e.m.).

Results

Time dependence of behavioral alterations and glutamate elevations in response to social isolation

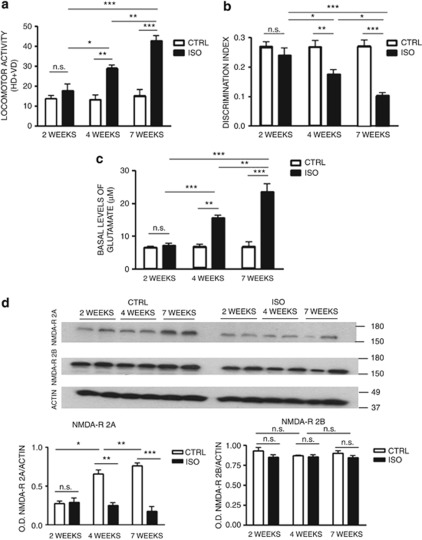

To define the time course of behavioral alterations induced by social isolation, we isolated rats for 2, 4 or 7 weeks. At the end of the isolation period, we performed the open field test and the novel object recognition test. We focused on behavioral functions that are regulated by nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex, such as spontaneous locomotor activity and novel object discrimination.23 These two brain regions appear to be most affected by social isolation, in terms of neurochemistry, neuronal organization and stress-induced injury.34, 36 Results from the open field test showed no significant difference in locomotor activity between control and isolated rats after 2 weeks of social isolation (Figure 1a). Increased locomotor activity in isolated rats was detected after 4 weeks of social isolation with respect to control animals (Figure 1a) and became more significant after 7 weeks of social isolation (Figure 1a). Similar results were obtained in the novel object recognition test. Thus, decrease in discrimination index started around 4 weeks after the beginning of social isolation, and worsened after 7 weeks (Figure 1b). To correlate these behavioral alterations with disorders in neurotransmission and alterations in NMDA receptors, we evaluated cortical basal levels of glutamate by intracerebral microdialysis and NMDA receptors subunit 2A and 2B levels by western blotting in control and isolated rats (n=6 for each time point). Glutamate levels were stable in control animals over the 7-week period. In contrast, in isolated animals, glutamate levels progressively increased after 4 and 7 weeks of social isolation (Figure 1c). Western blotting results showed a physiological time-dependent increase in the subunit 2A of the NMDA receptor in the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens from week 2 to week 7, whereas no increase in this subunit was observed in isolated animals during the same period of the brain development (Figure 1d and Supplementary Figure 2A and B). The levels of the subunit 2B of the NMDA receptor remained stable over the considered time points in control and isolated animals (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Alterations in behavior and cortical basal levels of glutamate appear after 4 weeks of social isolation. (a) Locomotor activity in the open field test in control (CTRL) and isolated (ISO) rats after 2, 4 and 7 weeks of social isolation (n=6 for each group in each time point). HD=horizontal displacements (number of crossings of the black lines); VD=vertical displacements (number of rearings). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test; r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=61.022, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=14.589, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=11.280, P<0.001. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant, P=0.259. (b) Discrimination index in the novel object recognition test in CTRL and ISO rats after 2, 4 and 7 weeks of social isolation (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=43.073, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=6.921, P<0.01; Ftxr(2,30)=7.284, P<0.01. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant, P=0.252. (c) Basal levels of glutamate in the prefrontal cortex of CTRL and ISO rats after 2, 4 and 7 weeks of social isolation (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance for repeated measures, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=76.842, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=24.338, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=21.953, P<0.001. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant, P=0.714. (d) Representative images of western blotting for N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit 2A (NMDA-R 2A), subunit 2B (NMDA-R 2B) and actin in the prefrontal cortex of CTRL and ISO rats for a period of 2, 4 and 7 weeks, with optical density (OD) protein bands normalized to the actin protein values (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance for repeated measures, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. For NMDA receptor subunit 2A: Fr(1,30)=173.020, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=32.237, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=89.073, P<0.001. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant, P=0.997. For NMDA receptor subunit 2B: Fr(1,30)=5.025, P=0.033; Ft(2,30)=0.507, P=0.607; Ftxr(2,30)=0.738, P=0.487; NS=not significant; rearing within 2 weeks, P=0.061; rearing within 4 weeks, P=0.677; rearing within 7 weeks, P=0.195; CTRL 2 weeks vs CTRL 4 weeks, P=0.278; CTRL 4 weeks vs CTRL 7 weeks, P=0.762.

Impact of social isolation on DNA oxidation in specific brain regions

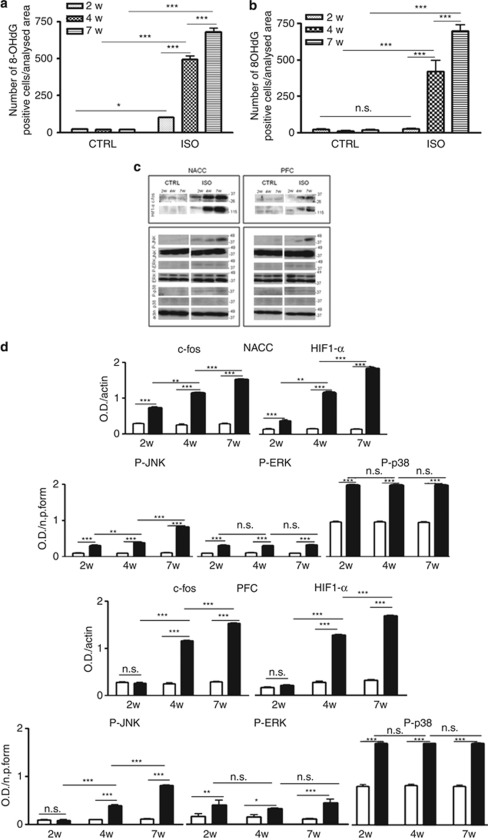

Alterations in behavior induced by social isolation and impairment in extracellular release of glutamate in rodent model of schizophrenia depend on oxidative stress.7, 17 Therefore, to correlate the profile of behavior and neurotransmission alterations with oxidative stress, we performed immunohistochemistry in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex of control and isolated rats (n=4, controls n=4, isolated for each time point), using an antibody raised against 8-OHdG, a readily detectable marker of oxidative stress to DNA.37 Both in the nucleus accumbens and in the prefrontal cortex of control rats, no signs of oxidative stress were detected at 2, 4 or 7 weeks of social isolation (Supplementary Figure 3A, B, E, F, I, J, M, N, Q, R and U, V). The nucleus accumbens, but not the prefrontal cortex, of isolated rats already showed an increase in 8-OHdG after 2 weeks of social isolation (Supplementary Figure 3C, D and O, P). After 4 weeks of social isolation, both the nucleus accumbens (Supplementary Figure 3G, H) and the prefrontal cortex (Supplementary Figure 3S, T) stained positively for 8-OHdG. This staining was further enhanced by 7 weeks of social isolation (Supplementary Figure 3K, L and W, X). Quantitative analysis, obtained through a count of 8-OHdG-positive cells in the nucleus accumbens and in the prefrontal cortex (Metamorph software), confirmed the visual impression (Figures 2a and b).

Figure 2.

Increase of oxidative stress in the nucleus accumbens after 2 weeks of social isolation and in the prefrontal cortex after 4 weeks of social isolation. (a) Quantification of 8-hydroxy-2-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG)-positive cells in the nucleus accumbens of control (CTRL) and of isolated rats (ISO) during a period of 2 weeks (2W), 4 weeks (4W) and 7 weeks (7W) (n=4 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. Fr(1,18)=477.096, P<0.001; Ft(2,18)=85.071, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,18)=87.630, P<0.001. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001. (b) Quantification of 8-OHdG-positive cells in the prefrontal cortex of control and of isolated rats during a period of 2 weeks (2W), 4 weeks (4W) and 7 weeks (7W) (n=4 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. Fr(1,18)=343.261, P<0.001; Ft(2,18)=116.700, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,18)=117.575, P<0.001. ***P<0.001; NS.=0.831. (c) Representative images of western blotting for c-fos, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), phospho-JNK (P-JNK), JNK, phospho-ERK (P-ERK), ERK, phospho-p38 (P-p38), p38 and actin in the nucleus accumbens (NACC) and prefrontal cortex (PFC) of CTRL and ISO rats during a period of 2 weeks (2W), 4 weeks (4W) and 7 weeks (7W) (n=6 for each group in each time point). (d) Optical density (OD) protein bands in the NACC normalized to the actin protein values of: c-fos (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=485.998, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=333.517, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=350.582. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; HIF-1α (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=939.904, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=714.198, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=719.777. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. OD protein bands in the NACC normalized to the non-phosphorylated form of the protein: P-JNK (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=164.382, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=183.754, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=161.450. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; P-ERK (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=345.543, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=0.417, P=0.662; Ftxr(2,30)=1.070, P=0.356. ***P<0.001; NS ISO 2W vs ISO 4W, P=0.984, ISO 4W vs ISO 7W, P=0.365; P-p38 (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=866.972, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=0.0211, P=0.979; Ftxr(2,30)=0.0544, P=0.947. ***P<0.001; NS ISO 2W vs ISO 4W, P=0.998, ISO 4W vs ISO 7W, P=0.955. OD protein bands in the PFC normalized to the actin protein values of: c-fos (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=850.086, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=417.383, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=396.376. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; HIF-1α (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=735.577, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=866.865, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=877.991, P<0.001. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. OD protein bands in the PFC normalized to the non-phosphorylated form of the protein: P-JNK (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=267.683, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=209.161, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=182.040, P<0.001; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; P-ERK (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=321.018, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=0.258, P=0.774; Ftxr(2,30)=0.701, P=0.504; ***P<0.001; NS ISO 2W vs ISO 4W, P=0.970; ISO 4W vs ISO 7W, P=0.886; P-p38 (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=159.224, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=0.0332, P=0.967; Ftxr(2,30)=0.179, P=0.837; ***P<0.001; NS ISO 2W vs ISO 4W, P=0.964; ISO 4W vs ISO 7W, P=0.977. The P-JNK, P-ERK and P-p38 were also normalized with α-actin. Virtually identical results were obtained (data not shown).

We next investigated possible isolation-induced changes in the levels of some indirect markers of oxidative stress, such as the immediate-early gene and redox-sensitive transcription factor c-fos, the HIF-1α protein, as well as the phosphorylated form of the MAP kinase JNK (p-JNK) (Figures 2c and d). In control animals, only weak levels of these indirect markers of oxidative stress were found. In contrast, in isolated animals there was a strong and time-dependent increase of these markers in the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex (Figures 2c and d). We also detected an increase of the phosphorylated form of the MAP kinase ERK and a weak increase of the phosphorylated form of p38 MAP kinase in isolated rats compared with controls. However, the expression of these two proteins did not seem to follow the time dependence of the increase observed for the other proteins (Figures 2c and d). Neither in the nucleus accumbens nor in the prefrontal cortex there were social isolation-induced differences in the expression of the total form of JNK, ERK and p38 (Figures 2c and d).

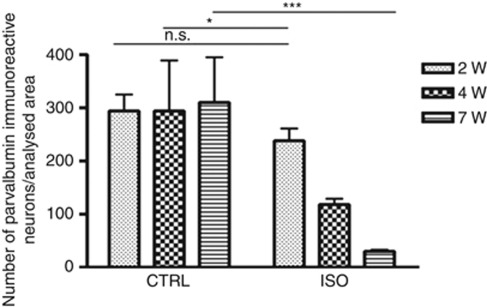

Loss of parvalbumin immunoreactivity

We next investigated the time dependence of the loss of parvalbumin protein in specific brain regions of isolated rats. This decrease reflects a loss of inhibitor phenotype of GABAergic neurons.8 In the prefrontal cortex and in the nucleus accumbens of control rats, parvalbumin protein amount (evaluated by immunohistochemistry and western blotting) was stable (Supplementary Figure 4A, B, E, F, I, J and M). In contrast, a statistically significant loss of parvalbumin content was detected starting from 2 weeks of social isolation in the nucleus accumbens (Supplementary Figure 4M) and from 4 weeks of social isolation in the prefrontal cortex (Supplementary Figure 4G, H). The loss of parvalbumin became even more marked after 7 weeks (Supplementary Figure 4K, L and M). Quantification of western blotting results in the nucleus accumbens (Supplementary Figure 4N) and quantitative analysis of immunohistochemistry in the prefrontal cortex (Figure 3), obtained through a count of parvalbumin-positive neurons (Metamorph software), confirmed these results.

Figure 3.

Loss of parvalbumin immunoreactivity in the prefrontal cortex after 4 weeks of social isolation. Quantification of parvalbumin immunoreactive neurons in the prefrontal cortex of control (CTRL) and of isolated (ISO) rats during a period of 2 weeks (2W), 4 weeks (4W) and 7 weeks (7W) (n=3–4 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,16)=20.459, P<0.001; Ft(2,16)=2.867, P=0.086; Ftxr(2,16)=3.492, P=0.055; *P<0.05; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant, P=0.360.

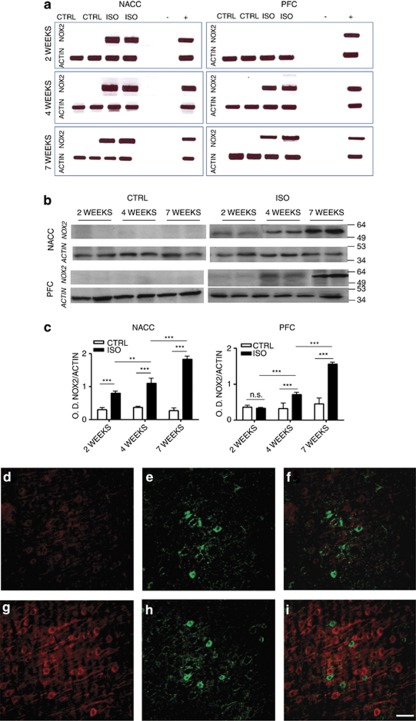

Social isolation induces early NOX2 elevations in the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex

The NOX2 complex is an important source of oxidative stress in the brain.7, 8, 9, 17 We have previously shown that after 7 weeks of social isolation, there are marked elevations of NOX2 in critical brain regions.17 To evaluate whether these NOX2 elevations are early or late events in the brain pathology induced by social isolation, we investigated the time course of NOX2 elevations. In the nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex of control rats, expression levels of NOX2 were below detection threshold as assessed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (30 cycles) (Figure 4a). In contrast, in isolated rats, a marked expression of NOX2 mRNA was observed already after 2 weeks in the nucleus accumbens and after 4 weeks in the prefrontal cortex (Figure 4a). To verify whether there were indeed elevations in NOX2 protein levels, we analyzed the expression of NOX2 by western blotting. No or only faint bands corresponding to the NOX2 protein were detected in control rats (Figure 4b). In contrast, the NOX2 protein was readily detectable in the nucleus accumbens after 2 weeks and after 4 weeks in the prefrontal cortex (Figure 4b). Quantification of NOX2 protein (ImageJ software; normalized with actin control) revealed that the expression of NOX2 in the nucleus accumbens progressively increased from week 2 to week 7 of social isolation (Figure 4c), whereas in the prefrontal cortex, NOX2 protein began to be expressed at 4 weeks and increased up to 7 weeks (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Increase of NOX2 in the nucleus accumbens (NACC) after 2 weeks of social isolation and in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) after 4 weeks of social isolation. (a) Representative images of reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for NOX2 and actin mRNA in the NACC and PFC of control (CTRL) and isolated (ISO) rats for a period of 2, 4 and 7 weeks. (−)=negative control: no SuperScript enzyme and 1 μl of water instead of 1 μl of cDNA (+)=positive control: spleen tissue. (b, c) Representative images of western blotting for NOX2 and actin in the NACC and PFC of CTRL and ISO rats for a period of 2, 4 and 7 weeks (b) with optical density (OD) protein bands normalized to the actin protein values (c) (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis for NACC: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=420.000, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=41.131, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=50.536, P<0.001; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; for PFC Fr(1,30)=95.395, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=62.384, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=43.345, P<0.001; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant ISO vs CTRL within 2 weeks, P=0.769. (d–i) Representative images of immunohistochemistry for p47phox (d, g) and GAD67 (e, h) in the PFC of CTRL and ISO animals. Panels f and i are merged images of p47phox and GAD67 staining. Red staining: p47phox; green staining: GAD67. Scale bar: 55 μm.

Social isolation induces an increase in the expression of p47phox subunit in pyramidal neurons

To determine which cell subpopulation of the brain was responsible of the NOX2 complex-derived increase of oxidative stress, we performed a double staining for the NOX2 subunits p47phox GAD67, a marker of GABAergic neurons, glial fibrillary acidic protein, a marker of astrocytes, and IBA-1, a marker of microglia in the prefrontal cortex of control and isolated animals. A weak red staining, corresponding to p47phox, was detected in controls (Figure 4d). Social isolation (7 weeks) induced a significant increase of the p47phox staining (Figure 4g and Supplementary Figure 5A, D and G). This was also confirmed by the analysis of the p47phox protein levels by western blotting in control and isolated animals (Supplementary Figure 6A and B). Merged images of the red and green staining GAD67 showed that the staining for p47phox was distinct from the GAD67 staining (Figures 4f–i and Supplementary Figure 5C, F and I). More specifically, the p47phox staining was located in cells whose density, distribution, anatomical connections with other neurons (in particular GABAergic neurons) and soma shapes unequivocally identify the p47phox-positive cells as pyramidal neurons.38, 39 The small green dots surrounding the cell body of the pyramidal neurons are dendrites from GABAergic neurons. These results indicate that the large majority of cells in which an increased p47phox subunit expression was observed were pyramidal neurons. Neither astrocytes nor microglia showed an increase of p47phox (data not shown).

To quantify the expression levels of GAD67 (green staining; Figures 4e–h), we performed western blotting analysis. Results showed a decrease in GAD67 expression in isolated animals compared with controls (Supplementary Figure 7A and B).

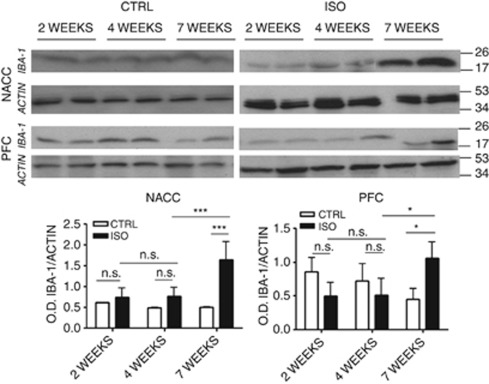

Impact of social isolation on microglial cells

Microglia is strongly affected in individuals with social stress-induced psychotic disorders40 and in animal models of chronic psychosocial stress.17

To evaluate the effects of social isolation on microglia cell number during brain development, we investigated possible alterations in IBA-1 protein expression in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex of controls and animals isolated for 2, 4 or 7 weeks by western blotting. In control animals, levels of IBA-1 protein were stable during the three considered time points both in the nucleus accumbens and in the prefrontal cortex (Figure 5). We could not observe any differences in IBA-1 expression between controls and isolated animals after 2 or 4 weeks of social isolation. Thus, only rats exposed to 7 weeks of social isolation showed an increase in the microglial cell number compared with controls (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of 2, 4 and 7 weeks of social isolation on the proliferation and activation of microglia. Representative images of western blotting for the ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA-1) and actin in the nucleus accumbens (NACC) and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of controls (CTRL) and isolated (ISO) rats for a period of 2, 4 and 7 weeks with optical density (OD) protein bands normalized to the actin protein values (n=6 for each group in each time point). Statistical analysis for NACC: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=95.395, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=62.384, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=43.345, P<0.001; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant ISO vs CTRL within 2 weeks, P=0.769, ISO vs CTRL within 4 weeks, P=0.069, time within ISO 4 weeks vs 2 weeks, P=0.524; for PFC: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. Fr(1,30)=0.0136, P=0.908; Ft(2,30)=0.522, P=0.599; Ftxr(2,30)=6.977, P=0.003; *P<0.05; NS=not significant ISO vs CTRL within 2 weeks, P=0.078, ISO vs CTRL within 4 weeks, P=0.298, time within ISO 4 weeks vs 2 weeks, P=0.998.

Analysis of activation of microglia, performed by immunohistochemistry for CD68, revealed that social isolation did not affect activation of microglia. Indeed, no staining for CD68 was observed in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex of control and isolated animals after 2, 4 or 7 weeks (data not shown for the absence of staining at week 2 and 4, absence of staining at 7 weeks shown in Supplementary Figure 8A–H), indicating that the increase of NOX2-derived oxidative stress was not mainly due to microglia activation. Note that CD68-positive microglial cells were found in other brain regions of the same animals (such as the forceps minor and the anterior commissure), indicating the validity of the antibody (Supplementary Figure 8I–L).

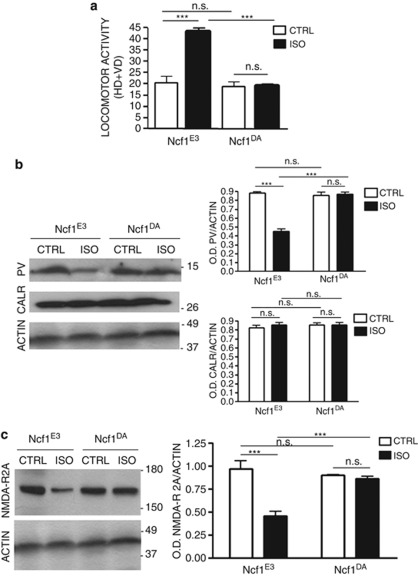

Ncf1 polymorphism influence the development of behavioral and neuropathological alterations induced by social isolation

To investigate the functional role of NOX2, we used DA rats that differed only in the Ncf1 locus: Ncf1E3 that has a normal NOX2 activity and Ncf1DA that has a strongly reduced NOX2 activity. After 7 weeks of social isolation rearing, we investigated the effect of this polymorphism on locomotor activity. Under control conditions, we did not observe any difference in locomotor activity, parvalbumin expression and subunit 2A of the NMDA receptor in Ncf1E3 rats and in Ncf1DA rats (data not shown). Note also that we did not observe any marked difference in the basal behavior, levels of parvalbumin and NMDA receptor subunit 2A and the social isolation response between Ncf1E3 and wistar rats (Supplementary Figure 9A–C). As wistar rats may also have the polymorphism, we genotyped all wistar rats used in our experiments and found that all of them had at least one Ncf1E3 allele, and therefore had normal NOX2 activity (data not shown).

Similarly as described above for wistar rats, social isolation led to increased motor activity as well as decreased central nervous system expression of parvalbumin and subunit 2A of the NMDA receptor (Figures 6a–c). In contrast, social isolation had no impact on motor activity of Ncf1DA rats (Figure 6a). Similarly, there was no decrease in protein expression of parvalbumin and subunit 2A of the NMDA receptor in isolated Ncf1DA rats (Figures 6b and c). Importantly, calretinin, a Ca2+-binding protein found in another subpopulation of GABAergic neurons, was stable for all conditions (including social isolation of Ncf1E3 rats), showing the specificity of the loss of parvalbumin (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

The Ncf1 mutation protects from the increase in locomotor activity, loss of parvalbumin protein and decrease in N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit 2A induced by 7 weeks of social isolation. Rats carrying a loss of function mutation (Ncf1DA strain) and isogenic controls (Ncf1E3 strain) were compared with respect to their response to social isolation. (a) Locomotor activity in the open field test of Ncf1E3 and Ncf1DA rats reared and control (CTRL) or social isolation (ISO) conditions for a period of 7 weeks (n=10 per group). HD=horizontal displacements (number of crossings of the black lines); VD=vertical displacements (number of rearings). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. gen=genotype; r=rearing condition. Fgen(1,36)=34.354, P<0.001; Fr(1,36)=27.681, P<0.001; Fgenxr(1,36)=26.718, P<0.001; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant. Ncf1E3 vs Ncf1DA, P=0.628; Ncf1DA CTRL vs Ncf1DA ISO, P=0.948. (b) Representative images of western blotting for parvalbumin (PV), calretinin (CLRT) and actin in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of Ncf1E3 and Ncf1DA control (CTRL) and isolated (ISO) for a period of 7 weeks with optical density (OD) protein bands normalized to the actin protein values (n=6 per group). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. gen=genotype; r=rearing condition. For PV: Fgen(1,20)=64.195, P<0.001; Fr(1,20)=72.038, P<0.001; Fgenxr(1,20)=81.554, P<0.001; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant. Ncf1E3 CTRL vs Ncf1DA CTRL, P=0.480; Ncf1DA CTRL vs Ncf1DA ISO, P=0.705. For CLRT: Fgen(1,20)=0.359, P=0.556; Fr(1,20)=0.359, P=0.556; Fgenxr(1,20)=0.359, P=0.556. NS=not significant. (c) Representative images of western blotting for the NMDA receptor subunit 2A (NMDA-R 2A) and actin in the PFC of Ncf1E3 and Ncf1DA CTRL and ISO for a period of 7 weeks with OD protein bands normalized to the actin protein values (n=6 per group). Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. gen=genotype; r=rearing condition. For PV: Fgen(1,20)=10.207, P=0.005; Fr(1,20)=26.485, P<0.001; Fgenxr(1,20)=20.401, P<0.001; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant Ncf1E3 CTRL vs Ncf1DA CTRL, P=0.361; Ncf1DA CTRL vs Ncf1DA ISO, P=0.661.

Treatment with the antioxidant/NOX inhibitor apocynin is more efficient when started early during social isolation

We have previously demonstrated that apocynin treatment during 7 weeks of social isolation prevents the development of behavioral and neuropathological alterations.17 To determine if apocynin might also have therapeutic effects, we treated isolated rats according to two different protocols. A first set of control and isolated rats was treated with apocynin during the second half of the social isolation period (weeks 4–7). Another set of animals was treated with apocynin 3 weeks starting from week 7, and were kept under isolation conditions until week 10 (Figure 7a). For both protocols, we evaluated the increase of locomotor activity and decrease in discrimination index in isolated animals with respect to controls.

Figure 7.

Effect of 3 weeks of apocynin (APCN) treatment on the increase of locomotor activity and decrease of discrimination index in isolated rats. (a) Protocol 1: APCN treatment (5 mg/kg per day) from week 4 (4w) to week 7 (7w) of social isolation. Protocol 2: APCN treatment (5 mg/kg per day) from week 7 (7w) to week 10 (10w) of social isolation. BT=behavioral tests. (b) Effect of protocols 1 and 2 on locomotor activity and discrimination index in control (CTRL) and isolated (ISO) rats. Statistical analysis: two-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. r=rearing condition; t=time of social isolation. For locomotor activity, protocol 1: Fr(1,30)=140.778, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=34.926, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=30.952, P<0.001. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant, P=0.680. For locomotor activity protocol 2: Fr(1,30)=199.299, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=2.228, P<0.125; Ftxr(2,30)=1.338, P=0.278. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. For discrimination index protocol 1: Fr(1,30)=15.003, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=1.897, P=0.168; Ftxr(2,30)=7.791, P=0.002. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; NS=not significant, P=0.403. For discrimination index protocol 2: Fr(1,30)=56.645, P<0.001; Ft(2,30)=43.472, P<0.001; Ftxr(2,30)=42.450, P<0.001. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Results show that apocynin treatment fully reversed the increase of locomotor activity and the decrease of discrimination index if the treatment started at 4 weeks of social isolation, whereas only a partial reversal could be achieved if treatment was started later (Figure 7b).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the development of neuropathology in a rat social isolation model and its causal relationship with increased oxidative stress in specific brain areas. We demonstrate that social isolation leads to early neuropathology and increased expression of the NOX2 subunit p47phox in cortical pyramidal neurons followed by altered behavior. Both loss of function polymorphism in the NOX2 subunit p47phox or a treatment with the antioxidant/NOX inhibitor apocynin after apparition of the symptoms largely prevents behavioral and neuropathological alterations induced by social isolation.

To our knowledge, the results shown here are the first time course of behavioral changes in the rat model of social isolation. Our study demonstrates that increased NOX2 expression, oxidative stress and neuropathological alterations occur first in the nucleus accumbens and only at later time points in the prefrontal cortex. Thus, behavioral alterations correlate best with oxidative stress and neuropathological alterations in the prefrontal cortex. This does however not exclude a role of the nucleus accumbens.

The nucleus accumbens and the prefrontal cortex are particularly sensitive to social stress in humans and rodents.41, 42, 43, 44, 45 An early involvement of the nucleus accumbens in response to social isolation was described previously: already after 3 weeks of social isolation, expression of the corticotropin-releasing factor in the nucleus accumbens is increased46 and the monoaminergic innervation in areas connecting to the nucleus accumbens are modified.47 In our study, we have shown that important neuropathological changes occur in the nucleus accumbens even before behavioral alterations are detectable. This might reflect a time delay in the response to oxidative stress; alternatively, it may indicate that behavioral alterations are due to concomitant neurochemical changes in the nucleus accumbens and in the prefrontal cortex.48, 49

Another novelty of this work is the demonstration of a causal involvement of p47phox in the progression of the brain pathology induced by social isolation. This conclusion is based on two observations: (i) the early neuronal elevations of p47phox and oxidative stress in response to social isolation; and (ii) the prevention of neuropathological alterations in rats with a decrease of function polymorphism in the Ncf1 gene coding for the NOX2 subunit p47phox.

The fact that NOX2 mRNA and protein are increased in the early phase strongly suggests that NOX2 is a major source of oxidative stress in the onset of psychosis. Early oxidative stress during the maturation window of normal brain development has been observed in perinatal pharmacological mouse model of psychosis induction, and has been implicated in schizophrenia-like behavioral dysfunctions in adulthood.10 Several observations suggest that oxidative stress is an important feature of human psychosis. This concept is mostly based on measurements of putative biomarkers of oxidative stress, such as reduction of reduced GSH in cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue in schizophrenic patients,50 increased levels of plasma thioredoxin-1 at the onset of schizophrenia51 or low total plasma antioxidant levels in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia.52 As NOX enzymes are major ROS generator, an increased activity of NOX2 or possibly other NOX isoforms may represent an important cause of redox modifications in psychosis.

The social isolation model is an important tool in psychosis research. Social isolation represents a profound psychological stressor for rodents,53 leading to reproducible neuropathology that mimics certain aspects of the response of the human brain to stressful situations.54 Rats are the best suited rodent model for this type of research, presumably because they have evolved different behavioral attitudes to react to external stimuli, such as alterations in its own social organization and stress-induced emotionality.55 Thus, rat behavioral responses to social deprivation are stronger than those observed in mice, presumably because the development of normal behavior in rats very strongly depends on social interactions.15

Despite the usefulness of the rat model, the required genetic proof of principle in rats is challenging, given the difficulties to obtain knockout rats. However, recent work has demonstrated the existence of a loss of function mutation in the Ncf1 gene coding for the p47phox subunit of NOX2. Through gene mapping experiments, it was found that an Ncf1 allele exchanging a single amino acid, threonine to methionine at position 153, leads to lower oxidative burst.18, 20 Importantly, the locus is highly polymorphic in the wild rat population, with a dominant effect of the fully functional E3 allele with threonine at position 153. It has been approximated that 60% of wild rats in northern Europe are homozygous for the Ncf1DA alleles and therefore have a low ROS response.18, 19 Rat laboratory strains, including wistar, are also polymorphic for the Ncf1 locus.19 In our study, we have used inbred DA rats that were polymorphic only with respect to the Ncf1 locus. The effects observed in Figure 6, showing the impact of homozygosis for the low oxidative burst allele Ncf1DA on social isolation, are therefore due only to a single-nucleotide polymorphism.20 Indeed, rats with low oxidative burst are protected from behavioral and neuropathological alterations induced by social isolation. As this polymorphism is widespread in wild rats, it might have been selected by evolution. Indeed, the polymorphism could confer resistance to stress to a subpopulation of rats. The balancing selection could be that rats with higher oxidative burst response might be protected from infectious and autoimmune diseases. In humans, an inverse correlation between schizophrenia and arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis has indeed been described.56, 57, 58

Together with the above-described genetic proof of concept, a pharmacological approach was performed. There are presently no specific NOX2 inhibitors; however, the anti-oxidant/NOX inhibitor apocynin shows neuroprotective properties in several brain disorders, such as cerebral ischemia59, 60 or Alzheimer disease.61 We and others have previously demonstrated that prophylaxis with apocynin prevents brain neuropathology in models of psychosis.8, 17 Here we demonstrate that apocynin is also efficacious when started after induction of behavioral alterations. However, complete curative effects, leading to normalization of altered behavior in isolated animals, are only observed when treatment is started relatively early. This is an important finding of this study as it may open new therapeutic approaches in human psychosis.

The data presented here provide the first investigation on the localization of the NOX2 complex in specific neuronal subpopulations. The large majority of GABAergic neurons did not show an increase in the expression of the NOX2 subunit p47phox induced by social isolation. Indeed, virtually all p47phox-expressing cells were pyramidal neurons, which are the predominant population of glutamatergic neurons in the cerebral cortex.38, 39 In control animals, the p47phox staining was weak, but after social isolation, it was intense. Several questions arise from this observation:

Why does the increase in the NOX2 complex occur selectively in glutamatergic pyramidal neurons, but the GABAergic neurons appear mostly affected? Our working hypothesis at this point is a diffusion of hydrogen peroxide from glutamatergic to GABAergic neurons. Indeed, this neuronal subpopulation is particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress.62, 63, 64 Such a paracrine action of ROS has been previously suggested in neuron–glia signaling in the hippocampus.65

What is the stimulus leading to increase of the NOX2 complex? At this point, the mechanisms leading to NOX2 upregulation in neurons are not understood. In the ketamine mouse model, neuronal production of interleukin-6 is necessary for the activation of NADPH oxidase in the brain.9

How could the increase in the NOX2 complex be related to glutamate levels? Basically we can consider two options: a cell autonomous effect of NOX2-derived ROS in glutamatergic neurons or a paracrine effect on GABAergic neurons (see above) or glial cells. In glutamatergic neurons, specific pathways leading to glutamate release may be inhibited by redox mechanisms, including specific enzymes involved in glutamate production, transport, exocytosis66 or redox-sensitive kinases or phosphatases regulating molecular pathways of glutamate release,67 or due to redox-sensitive ion channels, such as ryanodine receptors.68 Alternatively, a paracrine effect of NOX2-derived ROS might be due to an acute inhibition of GABAergic neurons, thereby blocking the inhibitory effect on glutamatergic neurons and subsequently leading to overproduction of glutamate.

Social isolation induced a decrease in the expression levels of GAD67, which is a marker for all GABAergic neurons and not related to a specific subtype. These results are in line with previous finding showing a consistent reduction of this global GABAergic marker in post-mortem brain samples from psychotic patients69, 70, 71 and other animal models of psychosis.72, 73, 74 Note however that the extent of GAD67 decrease (∼45%) was markedly smaller than the parvalbumin decrease (∼85%) after 7 weeks of social isolation. And we did not observe any decrease in specific markers of other GABAergic subtypes, namely calretinin (Figure 6b) and calbindin (data not shown). Thus, our results suggest that the main target cells in the social isolation model are parvalbumin-positive neurons; however, we cannot exclude some changes in gene expression also in other GABAergic subtypes.

Contradictory evidence exists about the effects of social isolation on the cortical expression of the subunit 2A of NMDA receptor. Thus, either increase75 or decrease24 in this brain region has been described previously. Our results are clearly in favor of the latter. Indeed, as expected, in the cortex of control animals, the expression of the NMDA receptor subunit 2A progressively increased from the second week to the seventh week after weaning.76, 77, 78 In contrast, NMDA receptor subunit 2A levels in the prefrontal cortex of isolated animals did not increase during this critical age period of brain development. Importantly, in rats with a decrease of function Ncf1 allele, the NMDA receptor subunit 2A shows a normal age-dependent increase after 7 weeks. These findings suggest that NOX2-derived oxidative stress is responsible for abnormal development of NMDA glutamate receptors.

Many reports describe the presence of NOX2 and its subunit p47phox in cells other than neurons in the brain, in particular microglia.4 Yet, there are also studies reporting the presence of p47phox in neurons, but not in the glia.79, 80 It is thought that increased NOX2 occurs in inflammatory conditions in microglia and regulates microglia activation.81, 82 However, under our experimental conditions, in spite of microglia proliferation at week 7, no or little activated microglia (as evidenced by the absence of CD68 staining) was observed. This might explain why p47phox staining was below detection level in the microglia.

In conclusion, this study provides strong evidence that psychosocial stress leads to a rapid upregulation of the NOX2 complex in neurons with subsequent generation of oxidative stress, ultimately leading to the development of neuropathological alterations. The NOX2-derived oxidative stress leads to increased glutamate levels, interferes with normal brain development and reduces the number of parvalbumin-positive inhibitory neurons. Thus, our results provide new elements for the understanding of the early neuropathological processes leading to stress-induced psychosis. Our data suggest that NOX2 is central in stress-induced central nervous system signaling and that NOX2-related pathways might provide new diagnostic and curative approaches for psychosis-related mental disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Olivier Plastre, Dr Paolo Tucci, Dr Margherita Zotti and Dr MariaGrazia Morgese for excellent technical support for western blotting and behavioral test and Katharine Brieger for help with editing. This work has been supported by the Swiss National Foundation (Grant No. 3200A0-103725), the Italian PRIN to LT, the Swedish Medical Research Council, the European Union Grants MASTERSWITCH (HEALTH-F2-2008-223404) and EURATRANS (HEALTH-F4-2010-241504).

KHK and VJ are founding members of the startup company GenKyoTex (http://www.genkyotex.com), which develops NOX inhibitors. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter of this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- van Winkel R, Stefanis N, Myin-Germeys I. Psychosocial stress and psychosis. A review of the neurobiological mechanisms and the evidence for gene–stress interaction. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:1095–1105. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Ravinder R. Oxidative stress in schizophrenia: pathogenetic and therapeutic implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1999–2002. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard K, Krause K. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorce S, Krause K-H. NOX enzymes in the central nervous system: from signaling to disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2481–2504. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infanger D, Sharma R, Davisson R. NADPH oxidases of the brain: distribution, regulation, and function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1583–1596. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubeníková-Valesová V, Horácek J, Vrajová M, Höschl C. Models of schizophrenia in humans and animals based on inhibition of NMDA receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1014–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorce S, Schiavone S, Tucci P, Colaianna M, Jaquet V, Cuomo V, et al. The NADPH oxidase NOX2 controls glutamate release: a novel mechanism involved in psychosis-like ketamine responses. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11317–11325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1491-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens M, Ali S, Dao D, Lucero J, Shekhtman G, Quick K, et al. Ketamine-induced loss of phenotype of fast-spiking interneurons is mediated by NADPH-oxidase. Science. 2007;318:1645–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1148045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens M, Ali S, Dugan L. Interleukin-6 mediates the increase in NADPH-oxidase in the ketamine model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13957–13966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4457-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell SB, Sejnowski TJ, Behrens MM. Behavioral and neurochemical consequences of cortical oxidative stress on parvalbumin–interneuron maturation in rodent models of schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:1322–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss I, Feldon J. Environmental animal models for sensorimotor gating deficiencies in schizophrenia: a review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:305–326. doi: 10.1007/s002130100800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng A, Feldon J, Ferger B. Long-term social isolation and medial prefrontal cortex: dopaminergic and cholinergic neurotransmission. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Seeman P, Marsden C, Fone K. Increased dopamine D2High receptors in rats reared in social isolation. Synapse. 2009;63:476–483. doi: 10.1002/syn.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Ellenbroek B. Animal behavior models of the mechanisms underlying antipsychotic atypicality. Progr Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapiz M, Fulford A, Muchimapura S, Mason R, Parker T, Marsden C. Influence of postweaning social isolation in the rat on brain development, conditioned behavior, and neurotransmission. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2003;33:13–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1021171129766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte M, Powell S, Swerdlow N, Geyer M, Reynolds G. Deficits in parvalbumin and calbindin immunoreactive cells in the hippocampus of isolation reared rats. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:893–898. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavone S, Sorce S, Dubois-Dauphin M, Jaquet V, Colaianna M, Zotti M, et al. Involvement of NOX2 in the development of behavioral and pathologic alterations in isolated rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson P, Holmberg J, Tordsson J, Lu S, Akerström B, Holmdahl R. Positional identification of Ncf1 as a gene that regulates arthritis severity in rats. Nat Genet. 2003;33:25–32. doi: 10.1038/ng1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson P, Johansson Å, Wedekind D, Klöting I, Klinga-Levan K, Lu S, et al. Inconsistent susceptibility to autoimmunity in inbred LEW rats is due to genetic crossbreeding involving segregation of the arthritis-regulating gene Ncf1. Genomics. 2004;83:765–771. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultqvist M, Sareila O, Vilhardt F, Norin U, Olsson L, Olofsson P, et al. Positioning of a polymorphic quantitative trait nucleotide in the Ncf1 gene controlling oxidative burst response and arthritis severity in rats. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2373–2383. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léna I, Chessel A, Le Pen G, Krebs M, Garcia R. Alterations in prefrontal glutamatergic and noradrenergic systems following MK-801 administration in rats prenatally exposed to methylazoxymethanol at gestational day 17. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;192:373–383. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0719-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva FCC, do Carmo de Oliveira Cito M, da Silva MIG, Moura BA, de Aquino Neto MR, Feitosa ML, et al. Behavioral alterations and pro-oxidant effect of a single ketamine administration to mice. Brain Res Bull. 2010;83:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fone KCF, Porkess MV. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of post-weaning social isolation in rodents—relevance to developmental neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1087–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Sun L, Jia H, Meng Q, Wu S, Li N, et al. Isolation rearing induces social and emotional function abnormalities and alters glutamate and neurodevelopment-related gene expression in rats. Progr Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:1173–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz M, Marden J, Zhou W, Zhang Y, Williams A, Sharov V. SOD1 mutations disrupt redox-sensitive Rac regulation of NADPH oxidase in a familial ALS model. J Clin Invest. 2008;18:659–670. doi: 10.1172/JCI34060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa H. Age dependent effects of space limitation and social tension on open-field behavior in male rats. Physiol Behav. 2005;84:429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carratù M, Borracci P, Coluccia A, Giustino A, Renna G, Tomasini M. Acute exposure to methylmercury at two developmental windows: focus on neurobehavioral and neurochemical effects in rat offspring. Neuroscience. 2006;141:1619–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, Delacour J. A new one-trial test for neurobiological studies of memory in rats. 1: behavioral data. Behav Brain Res. 1988;31:47–59. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(88)90157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Sleight A, Woolley M, Topham I, Marsden C, Fone K. 5-HT6 receptor antagonists reverse delay-dependent deficits in novel object discrimination by enhancing consolidation—an effect sensitive to NMDA receptor antagonism. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabace L, Cassano T, Colaianna M, Castrignanò S, Giustino A, Amoroso S. Neurochemical and neurobehavioral effects of ganstigmine (CHF2819), a novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, in rat prefrontal cortex: an in vivo study. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini M, Bartolini L, Kopf S, Pepeu G. Acetylcholine release from the frontal cortex during exploratory activity. Brain Res. 1998;784:218–227. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carli M, Calcagno E, Mainolfi P, Mainini E, Invernizzi R. Effects of aripiprazole, olanzapine, and haloperidol in a model of cognitive deficit of schizophrenia in rats: relationship with glutamate release in the medial prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;214:639–652. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press: New York; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Czéh B, Perez-Cruz C, Fuchs E, Flügge G. Chronic stress-induced cellular changes in the medial prefrontal cortex and their potential clinical implications: does hemisphere location matter. Behav Brain Res. 2008;190:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchizono Y, Takeya R, Iwase M, Sasaki N, Oku M, Imoto H, et al. Expression of isoforms of NADPH oxidase components in rat pancreatic islets. Life Sci. 2006;80:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alquicer G, Morales-Medina JC, Quirion R, Flores G. Postweaning social isolation enhances morphological changes in the neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion rat model of psychosis. J Chem Neuroanat. 2008;35:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen A, Murphy J. Reactions of oxyl radicals with DNA. Pharmacol Res. 1995;18:1033–1077. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnavelas J, Lieberman A, Webster K. Organization of neurons in the visual cortex, area 17, of the rat. J Anat. 1977;124:305–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M.Development of projection and local circuit neurons in neocortex Cerebral CortexPeters and Jones (eds). vol. 7. Development and maturation of cerebral cortex. Plenum Press: New York; 1988133–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wohleb E, Hanke M, Corona A, Powell N, Stiner L, Bailey M, et al. Adrenergic receptor antagonism prevents anxiety-like behavior and microglial reactivity induced by repeated social defeat. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6277–6288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0450-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern S, Oakes TR, Stone CK, McAuliff EM, Kirschbaum C, Davidson RJ. Glucose metabolic changes in the prefrontal cortex are associated with HPA axis response to a psychosocial stressor. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:517–529. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei N, Everaerd W, Elzinga B, van Well S, Bermond B. Psychosocial stress impairs working memory at high loads: an association with cortisol levels and memory retrieval. Stress. 2006;9:133–141. doi: 10.1080/10253890600965773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb J, Hayley S, Gandhi R, Poulter MO, Anisman H. Synergistic and additive actions of a psychosocial stressor and endotoxin challenge: circulating and brain cytokines, plasma corticosterone and behavioral changes in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:573–589. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato J, Bankson M, Yamamoto B. Prior exposure to chronic stress and MDMA potentiates mesoaccumbens dopamine release mediated by the 5-HT(1B) receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:946–954. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JC, D'Almeida V, Antunes IB, Tufik S. Distinct behavioral and neurochemical alterations induced by intermittent hypoxia or paradoxical sleep deprivation in rats. Progr Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukkes JL, Mokin MV, Scholl JL, Forster GL. Adult rats exposed to early-life social isolation exhibit increased anxiety and conditioned fear behavior, and altered hormonal stress responses. Hormones Behav. 2009;55:248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gos T, Becker K, Bock J, Malecki U, Bogerts B, Poeggel G, et al. Early neonatal and postweaning social emotional deprivation interferes with the maturation of serotonergic and tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive afferent fiber systems in the rodent nucleus accumbens, hippocampus and amygdala. Neuroscience. 2006;140:811–821. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Wang W, Shao F, Li N. Isolation rearing alters social behaviors and monoamine neurotransmission in the medial prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens of adult rats. Brain Res. 2011;1385:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius K, Steiniger-Brach B, Helboe L, Fink-Jensen A, Wörtwein G. Socially isolated rats exhibit changes in dopamine homeostasis pertinent to schizophrenia. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2011;29:347–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do KQ, Cabungcal JH, Frank A, Steullet P, Cuenod M. Redox dysregulation, neurodevelopment, and schizophrenia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:220–230. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owe-Larsson B, Ekdahl K, Edbom T, Ösby U, Karlsson H, Lundberg C, et al. Increased plasma levels of thioredoxin-1 in patients with first episode psychosis and long-term schizophrenia. Progr Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1117–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XF, Zheng YL, Xiu MH, Chen DC, Kosten TR, Zhang XY. Reduced plasma total antioxidant status in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Progr Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1064–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karelina K, DeVries A. Modeling social influences on human health. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:67–74. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden CA, King MV, Fone KCF. Influence of social isolation in the rat on serotonergic function and memory—relevance to models of schizophrenia and the role of 5-HT6 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohus B, Benus R, Fokkema D, Koolhaas J, Nyakas C, van Oortmerssen G, et al. Neuroendocrine states and behavioral and physiological stress responses. Prog Brain Res. 1987;72:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)60196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF, Yolken RH. The schizophrenia–rheumatoid arthritis connection: infectious, immune, or both. Brain Behav Immunity. 2001;15:401–410. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov S, Gottesman I, Moises H, Nicol S. Negative association between schizophrenia and rheumatoid arthritis. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:669–678. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorwood P, Pouchot J, Vinceneux P, Puéchal X, Flipo R, De Bandt M, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis and schizophrenia: a negative association at a dimensional level. Schizophr Res. 2004;66:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LLYK, Yang XF, Zheng JS. Apocynin attenuates cerebral infarction after transient focal ischaemia in rats. J Int Med Res. 2007;35:517–522. doi: 10.1177/147323000703500411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Tompkins KD, Simonyi A, Korthuis RJ, Sun AY, Sun GY. Apocynin protects against global cerebral ischemia–reperfusion-induced oxidative stress and injury in the gerbil hippocampus. Brain Res. 2006;1090:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lull M, Levesque S, Surace M, Block M. Chronic apocynin treatment attenuates beta amyloid plaque size and microglial number in hAPP(751)(SL) mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeevalk G, Derr-Yellin E, Nicklas W. Relative vulnerability of dopamine and GABA neurons in mesencephalic culture to inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase by malonate and 3-nitropropionic acid and protection by NMDA receptor blockade. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;257:1124–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guentchev M, Voigtländer T, Haberler C, Groschup MH, Budka H. Evidence for oxidative stress in experimental prion disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:270–273. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Y, Gawai KR, Nie Z, Ramkumar V, Helfert RH. Age-related reductions in the activities of antioxidant enzymes in the rat inferior colliculus. Hearing Res. 1999;135:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins C, Sweatt J. Reactive oxygen species mediate activity-dependent neuron–glia signaling in output fibers of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7241–7248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07241.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosic M, Ott J, Barral S, Bovet P, Deppen P, Gheorghita F, et al. Schizophrenia and oxidative stress: glutamate cysteine ligase modifier as a susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:586–592. doi: 10.1086/507566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantano C, Reynaert N, van der Vliet A, Janssen-Heininger Y. Redox-sensitive kinases of the nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1791–1806. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser BL, Ward CW, Lederer WJ. X-ROS signaling: rapid mechano-chemo transduction in heart. Science. 2011;333:1440–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.1202768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti A, Auta J, Davis JM, Gerevini VD, Dwivedi Y, Grayson DR, et al. Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a postmortem brain study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossein Fatemi S, Stary JM, Earle JA, Araghi-Niknam M, Eagan E. GABAergic dysfunction in schizophrenia and mood disorders as reflected by decreased levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and 67 kDa and reelin proteins in cerebellum. Schizophr Res. 2005;72:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Weickert CS, Wyatt E, Webster MJ. Decreased glutamic acid decarboxylase67 mRNA expression in multiple brain areas of patients with schizophrenia and mood disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:970–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge D, Behrens M, Grace AA. A loss of parvalbumin-containing interneurons is associated with diminished oscillatory activity in an animal model of schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2344–2354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5419-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts CD. The changing roles and targets for animal models of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:845–855. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkman HO, Loetscher E. GAD(67): the link between the GABA-deficit hypothesis and the dopaminergic- and glutamatergic theories of psychosis. J Neural Transm. 2003;110:803–812. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0826-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnock-Jones J, Jennings C, Robbins M, Cluderay J, Cilia J, Reid J, et al. Increased expression of the NR2A NMDA receptor subunit in the prefrontal cortex of rats reared in isolation. Synapse. 2009;63:836–884. doi: 10.1002/syn.20665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R, Anderson E, Lynch G, Baudry M. Selective impairment of learning and blockade of long-term potentiation by an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, AP5. Nature. 1986;319:774–776. doi: 10.1038/319774a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RJ, Stewart MG, Rose SPR. Increases in NMDA receptor binding are specifically related to memory formation for a passive avoidance task in the chick: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Brain Res. 1995;674:352–356. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00014-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmignoto G, Vicini S. Activity-dependent decrease in NMDA receptor responses during development of the visual cortex. Science. 1992;258:1007–1011. doi: 10.1126/science.1279803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Kim M, Shin K-S, Chung Y-B, Jung KW, Cha CI, Hoon Shin D. Immunohistochemical study of p47Phox and gp91Phox distributions in rat brain. Brain Res. 2005;1040:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano F, Kolluri NS, Wientjes FB, Card JP, Klann E. NADPH oxidase immunoreactivity in the mouse brain. Brain Res. 2003;988 (1–2:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka H, Niizuma K, Katsu M, Okami N, Sakata H, Kim G, et al. NADPH oxidase mediates striatal neuronal injury after transient global cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:868–880. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrano A, Hoozemans J, van der Vies S, Rozemuller A, van Horssen J, de Vries H. Amyloid beta induces oxidative stress-mediated blood–brain barrier changes in capillary amyloid angiopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1167–1178. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.