Abstract

Phenylalanine is an essential amino acid required for the synthesis of catecholamines including dopamine. Altered levels of phenylalanine and its metabolites in blood and cerebrospinal fluid have been reported in schizophrenia patients. This study attempted to examine for the first time whether phenylalanine kinetics is altered in schizophrenia using L-[1-13C]phenylalanine breath test (13C-PBT). The subjects were 20 chronically medicated schizophrenia patients (DSM-IV) and the same number of age- and sex-matched controls. 13C-phenylalanine (99 atom% 13C; 100 mg) was administered orally and the breath 13CO2 /12CO2 ratio was monitored for 120 min. The possible effect of antipsychotic medication (risperidone (RPD) or haloperidol (HPD) treatment for 21 days) on 13C-PBT was examined in rats. Body weight (BW), age and diagnostic status were significant predictors of the area under the curve of the time course of Δ13CO2 (‰) and the cumulative recovery rate (CRR) at 120 min. A repeated measures analysis of covariance controlled for age and BW revealed that the patterns of CRR change over time differed between the patients and controls and that Δ13CO2 was lower in the patients than in the controls at all sampling time points during the 120 min test, with an overall significant difference between the two groups. Chronic administration of RPD or HPD had no significant effect on 13C-PBT indices in rats. Our results suggest that 13C-PBT is a novel laboratory test that can detect altered phenylalanine kinetics in chronic schizophrenia patients. Animal experiments suggest that the observed changes are unlikely to be attributable to antipsychotic medication.

Keywords: 13C-phenylalanine breath test, dopamine, metabolism, phenylalanine hydroxylase, schizophrenia, stable isotope

Introduction

L-Phenylalanine is an essential amino acid required for catecholamine biosynthesis. Altered levels of phenylalanine and its metabolites, including another precursor for dopamine biosynthesis, the downstream amino acid tyrosine, could be related to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia.1, 2 Indeed, serum phenylalanine levels were found to be significantly higher,3 and tyrosine levels lower4 in drug-free patients with schizophrenia than in healthy controls. However, Wei et al.5 reported no significant difference between serum phenylalanine levels of drug-free schizophrenics and healthy controls, although the ratio of tyrosine to phenylalanine was significantly lower in patients with early-onset disease than in controls. The phenylalanine level in cerebrospinal fluid was significantly higher in schizophrenia patients with or without neuroleptics than in controls.6 However, Potkin et al.7 found no significant difference in plasma phenylalanine or tyrosine levels between chronic schizophrenia patients with or without neuroleptics and controls. Phenylethylamine, a metabolite of phenylalanine that is considered an endogenous neuroamine, was significantly higher in plasma samples from medicated patients with schizophrenia than in those from controls.8, 9

The enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) converts phenylalanine to tyrosine using the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin; this activity takes place in the liver and kidney.10, 11 The PAH gene has been studied extensively in phenylketonuria (PKU), an autosomal recessive genetic disorder characterized by mental retardation, epilepsy, eczema and other clinical manifestations.12, 13, 14 Mutations in PAH are responsible for over 98% of PKU cases and more than 500 causative mutations have been reported (http://www.pahdb.mcgill.ca/).13 The possible association between PKU and psychiatric disorders was first described in 1935 by Penrose,15 who stated that PKU mutation heterozygotes might be predisposed to mental disorders. In 1974, Kuznetsova studied 300 parents of PKU patients and suggested that PKU heterozygotes may have increased susceptibility to late-onset schizophrenia.16, 17 Although a recent molecular genetic study focusing on two PKU-causing PAH mutations in 190 schizophrenia patients and 336 controls reported a contradictory negative result,18 Richardson et al. found that a novel PAH mutation, K274E, may possibly be associated with psychiatric disorders in African-Americans.19, 20, 21 Furthermore, the same research group screened samples from 123 patients with psychiatric disorders for PAH mutations and found decreased phenylalanine kinetics in schizophrenia patients with the K274E mutation compared with patients without the mutation.22 A meta-analysis including two eligible studies (164 cases and 51 controls) detected no significant association between PAH and schizophrenia.23 However, two more recent studies have suggested that PAH polymorphisms confer susceptibility to schizophrenia24 and modify features of psychotic disorders.25

The enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) uses tetrahydrobiopterin to catalyze the conversion of tyrosine to L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), which is the rate-limiting step in the syntheses of dopamine and noradrenaline.10 One of the mechanisms by which TH is regulated is feedback inhibition by its end products, that is, dopamine and noradrenaline.26, 27 TH is normally found in the adrenal glands and central nervous system,10, 28 but a study of TH in peripheral blood found overexpression of TH mRNA in schizophrenia.29 However, previous genetic studies30, 31 and a meta-analysis23 of reported studies has shown no positive evidence for an association between genetic polymorphisms in TH and schizophrenia.

13C-labeled substrates have been applied for various rapid, noninvasive breath tests in medicine.32 The L-[1-13C]phenylalanine breath test (13C-PBT) has been used to measure the in vivo activity of the PAH enzyme in PKU.33, 34 Yamashita et al.35 first described the use of the 13C-PBT in patients with psychiatric disorders, administering 100 mg per body of L-[1-13C]phenylalanine (13C-phenylalanine) to 4 patients with depression and 11 healthy control subjects and describing changes of the pattern of phenylalanine kinetics in depression patients. Although phenylalanine, tyrosine and the enzymes involved in their metabolisms have been thoroughly studied in the brain and periphery, as outlined above, we could find no previous reports on the administration of 13C-PBT, which provides a real-time assessment of the whole-body kinetics and metabolism of phenylalanine, in patients with schizophrenia or mood disorders.

The aim of the present study was to examine whether phenylalanine kinetics as assessed by 13C-PBT are altered in schizophrenia patients. Given that reduced PAH activity may be related to schizophrenia susceptibility, we hypothesized that phenylalanine metabolism is suppressed in schizophrenia patients. We also performed experiments in rats to elucidate the possible effects of typical or atypical antipsychotic medication on phenylalanine kinetics.

Materials and methods

Participants

The subjects were 20 schizophrenia patients and the same number of healthy age- and sex-matched controls. The patients were recruited from the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (NCNP) Hospital and associated psychiatric hospitals (Henmi Hospital and Yamada Psychiatric Hospital). These hospitals are located in the same geographical area in the western part of metropolitan Tokyo. The schizophrenia patients were diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM- IV) criteria36 and careful examination of medical records by the consensus of at least two experienced psychiatrists. Age- and sex-matched healthy controls were recruited through advertisements in free local information magazines and by announcements on our website. All healthy control subjects were screened by psychiatrists using the Japanese version of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)37, 38 to confirm no past or current history of major psychiatric illness. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant or lactating, reported psychoactive drug use or alcohol abuse within the previous 6 months, or had a history of severe head injury, an endocrine disease, a respiratory disease, or a serious physical disorder, especially any type of disease of the kidneys or liver, where phenylalanine is mainly metabolized. Participants underwent blood testing of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), cholinesterase (ChE), blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels to rule out kidney or liver dysfunction. Data on total protein, albumin, total bilirubin and platelet counts were also collected from the patients' medical records to check liver function, although one patient was missing such data. Individuals who showed any blood test abnormalities were not enrolled in the study. All participants were biologically unrelated Japanese who resided in the western part of Tokyo. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of the NCNP. Signed informed consent was obtained from each subject after a detailed description of the study aim and protocol.

Principle of the 13C-PBT

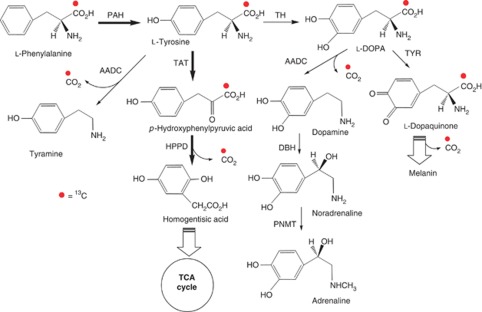

The kinetic values for L-[1-13C]phenylalanine represent those for unlabeled phenylalanine.39 Orally administered phenylalanine is absorbed at the brush border membrane of the proximal small intestine. Approximately three-fourths of absorbed dietary phenylalanine is irreversibly converted to tyrosine by PAH in the liver and kidney.10, 11, 24 The most quantitatively important route of tyrosine metabolism is degradation to p-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid and then homogentisic acid by transamination and subsequent decarboxylation, respectively.40 The other two major pathways of phenylalanine metabolism are the conversion of tyrosine into tyramine by aromatic amino acid decarboxylase and the conversion of L-DOPA into dopamine by aromatic amino acid decarboxylase in the adrenal glands and central nervous system (Figure 1).10, 28, 41 The 13CO2 derived from administered 13C-phenylalanine can be produced not only by the three main pathways but also by other, minor ones: the conversion of phenylalanine to phenylethylamine and melanin synthesis from tyrosine. The 13CO2 /12CO2 ratio measured in the 13C-PBT is expected to reflect the total 13CO2 produced in vivo from administered 13C-phenylalanine through all of the mechanisms described above, although the three main pathways are the major contributors to 13CO2 production.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating main routes for L-[1-13C]phenylalanine (13C-phenylalanine) metabolism. The conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine is observed in the liver and kidney and is the main step of the metabolism of phenylalanine. The most quantitatively major three pathways for tyrosine metabolism is the degradation forming p-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid and homogentisic acid, the conversion of tyrosine into tyramine and the conversion of L-DOPA into dopamine via tyrosine. In all of the main three routes, 13CO2 was exhaled. The 13CO2 /12CO2 ratio measured in the 13C-phenylalanine breath test is expected to reflect the total 13CO2 produced in vivo from administered 13C-phenylalanine through these reaction routes. Minor pathways and pathways without release of 13CO2 were omitted. Circles upon the carbon mark 13C-labeled carbon. Striped arrows indicate the multiple consecutive reactions. PAH, phenylalanine hydroxylase; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; AADC, aromatic amino acid decarboxylase; TAT, tyrosine transaminase; HPPD, 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid dioxygenase; DBH, dopamine β-hydroxylase; L-DOPA, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine; PNMT, phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase; TYR, tyrosinase.

The Δ13CO2 (‰) at each sampling point was calculated from the infrared (IR) absorption intensities of 13CO2 (2280±10 cm−1) and 12CO2 (2380±10 cm−1) by IR spectrometry (Equation (A) in Supplementary Table S1).33, 42 Then, data were obtained on the maximal Δ13CO2 (Cmax; ‰) and time to reach the maximal Δ13CO2 (Tmax; min). The amount of 13C-phenylalanine metabolized and exhaled as 13CO2 within 120 min was expressed as the cumulative recovery rate (CRR; %) and area under the Δ13CO2-time curve (AUC; ‰*min). The CRR was defined as the ratio of the total amount of exhaled 13CO2 to the administered dose of 13C-phenylalanine (Equation (B) to (E) in Supplementary Table S1).43

13C-PBT procedures

The method of 13C-PBT was performed as previously described.44 Participants were instructed to fast beginning at 0000 hours, drink water (but no juice, alcohol or other beverages) liberally, and refrain from smoking for at least 3 h before the breath test. Fasting blood samples were drawn before the start of the breath test. The blood samples were allowed to stand at room temperature for at least 30 min and separated by centrifugation at 3000 r.p.m. for 10 min. Supernatants were stored as serum at −20 °C until biochemical analysis for AST, ALT, ChE, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels by SRL Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). The baseline breath samples were collected twice into special breath-sampling bags (retention volume: 1300 ml each; Otsuka Electronics, Osaka, Japan). The subjects then drank aqueous solutions of 13C-phenylalanine (99 atom% 13C; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Cambridge, UK), 100 mg per subject in 100 ml of water, at 1000 h. Breath samples were collected into special breath-sampling bags (retention volume: 250 ml each; Otsuka Electronics) 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min after ingestion of the 13C-phenylalanine solution. All breath samples were collected after 10 sec of breath holding, which allows mixing of the gas in both the trachea and pulmonary alveoli to decrease the effects of respiratory dead space. Throughout the 13C-PBT, participants were instructed to remain quietly in a resting position. The 13CO2 /12CO2 ratio of the special breath-sampling bags was analyzed by IR spectrometry (UBiT-IR300 and UBiT-AS10, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) within 3 days of collection of each breath sample.

Clinical status and antipsychotic medication

The participants with schizophrenia were considered relatively stable on antipsychotic drugs. Current clinical symptoms in schizophrenic subjects were assessed using the positive and negative symptom scale (PANSS) and its Positive, Negative and General Psychopathology subscales.45 PANSS scoring was performed by a single experienced psychiatrist. Doses of antipsychotics and depot antipsychotics were converted to chlorpromazine equivalents (CPZeq) according to published guidelines.46, 47

Animals

Male Wistar rats weighing 300–400 g at postnatal day 42 were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Yokohama, Japan) for analysis of the influence of antipsychotics on the 13C-PBT results. Rats were housed under standard lighting conditions on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle and provided food and water ad libitum. All experimental procedures were approved by the ethics review committee for animal experimentation at the National Institute of Neuroscience, Japan and conducted according to the institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals.

13C-PBT in rats

The animal studies were performed during P56 to 80. Rats were randomly assigned to receive vehicle, risperidone (RPD), or haloperidol (HPD) for 21 days (N=15 for each group). RPD oral solution (1.0 mg ml–1; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Antwerp, Belgium) was administered in the rats' drinking water. HPD (Sigma-Aldrich Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in 0.1 M citric acid and administered diluted 1:100 in the rats' drinking water. The body weight (BW) and water or solution consumption of each rat were checked five times a week to adjust the concentrations of the solutions so that the rats received RPD or HPD at doses of 2.5 or 2.0 mg kg–1 per day, respectively, for 21 days. This duration of drug treatment was chosen based on prior reports that described the pharmacological effects of RPD and HPD in rats.48, 49 On the 21st day of drug administration, we checked the blood HPD concentrations of six rats randomly chosen from the 15 rats of the HPD group. The mean level of the blood HPD concentration was 6.8±4.3 ng ml–1, which is enough to induce pharmacological effects in rats.50 After 21 days of treatment, rats were fasted for over 15 h in mesh-floor cages (to prevent coprophagy) with 60 ml water. During the dark phase, fasted rats were injected intraperitoneally with saline solution containing 0.1% 13C-phenylalanine (10 ml kg–1 BW) and placed individually in an animal chamber (PC-250 K, 9000 ml, Sanplatec, Osaka, Japan) connected to an auto-breath collect device (Auto-breath collector, Otsuka Electronics), with a pump (Vacuum pump VP0125, Nitto Kohki, Tokyo, Japan) controlled by a programmed timer (PRO-io2, Digital Electronics, Osaka, Japan) for gas exchange in the chamber (Supplementary Figure S1). The air of the chamber was filtered (Millex FA, Millipore, MA, USA) and collected automatically into the special breath-sampling bags by the auto-breath sampling system as breath samples 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min after the injection of 13C-phenylalanine. To avoid excessive accumulation of expired CO2 gas, the chamber air was continuously exchanged by the pump with programmed timer through a hole (10 mm) on the chamber ceiling throughout the 120 min test except for the 8 and 12 min allowed for breath accumulation before the 10, 20 and 30 min and 45, 60, 90 and 120 min sampling points, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2).

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 11.0 (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was used to conduct all statistical tests, except for 95% confidence interval (CI), which was analyzed using the R software (http://www.r-project.org). General descriptions of continuous variables were expressed as mean±s.d. Differences in blood test values between the patients and controls were examined by using the t-test. The correlation between each index of 13C-PBT (AUC, CRR0–120, and Cmax) and each value of liver blood tests was examined using the Pearson's correlation analysis. The normality and the homoscedasticity of the dependent variables were checked, and stepwise multiple regression analyses were employed to examine the effect of diagnostic status (patients/controls) on indices of 13C-PBT (AUC, CRR0−120, and Cmax), controlling for gender, age and BW. A 2 × 8 (group × sampling point) repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to examine group differences in Δ13CO2 or CRR over time, controlling for age. Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied for lack of sphericity. The Cmax, AUC and CRR0–120 were compared between the patients and controls using the t-test and ANCOVA, controlling for age and BW and for age, BW and ALT. Tmax was the value of a discrete variable and was compared between the two groups using the Mann–Whitney test. In patients, the correlation between each index of 13C-PBT (AUC, CRR0–120, and Cmax) and CPZeq and PANSS total score was examined using Pearson's correlation analysis. A stepwise multiple regression was employed to assess independent predictors of AUC, CRR0–120 and Cmax, using gender, age, BW, CPZeq and PANSS total score as candidate predictors. For analysis of animal experiment results, a 3 × 7 (Group × sampling point) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine differences in Δ13CO2 over time between experimental groups. The Cmax and AUC were compared between experimental groups using one-way ANOVA and the Tmax by the Kruskal–Wallis test. The mean difference and median difference of the Cmax and AUC, and Tmax, respectively, among experimental groups and its 95% CI were calculated. Two-tailed p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and controls

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients and controls are shown in Table 1. Laboratory assessments of the liver and kidneys of all subjects fell within the normal ranges, although ALT was slightly, but significantly increased in the patients compared with that in the controls (t(30.1)=2.40, P=0.023). The duration of illness of the schizophrenia patients was 19.1±13.3 years. The majority (85%) of the schizophrenia patients were chronic inpatients, and the mean length of hospitalization was 2.7±4.3 years at the time of the 13C-PBT; this duration would not be considered unusually long in Japan, where long-term hospitalization due to disability in daily living is common, so that psychiatric hospitalization does not necessarily mean that the patient is in the acute phase of illness. The drug regimen of 17 of 20 of the schizophrenic participants had not been changed over the previous 3 months. Relatively large doses of antipsychotics were prescribed. These data demonstrate that the majority of the schizophrenic participants were in the chronic phase.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical variables of schizophrenia patients and healthy controls.

| Patients | Controls | t-test (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 10/10 | 10/10 | |

| Age (year) | 47.9±13.4 | 47.6±14.6 | 0.937 |

| Body weight (kg) | 63.2±12.0 | 61.5±9.8 | 0.625 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.1±4.0 | 23.0±2.6 | 0.311 |

| Age of onset (year) | 28.9±10.8 | ||

| Duration of illness (year) | 19.1±13.3 | ||

| Number of inpatients (%) | 17 (85.0) | ||

| Psychopathology score (PANSS) | |||

| Total | 61.4±13.3 | ||

| Positive scale | 11.3±3.7 | ||

| Negative scale | 19.0±7.3 | ||

| General psychopathology scale | 31.1±7.0 | ||

| CPZeq (mg per day) | 844.0±639.6 | ||

| AST (U l–1, reference value:10–40) | 19.1±6.1 | 18.7±4.5 | 0.792 |

| ALT (U l–1, reference value:5–40) | 18.9±10.5 | 12.4±6.0 | 0.023 |

| Cholinesterase (U l–1, reference value: m 242–495; f 200–459) | 300.9±90.3 | 327.7±57.3 | 0.269 |

| BUN (mg dl–1, reference value: 8.0–22.0) | 10.0±2.9 | 12.6±3.7 | 0.018 |

| Cr (mg dl–1, reference value: m, 0.61–1.04; f, 0.47–0.79) | 0.68±0.15 | 0.68±0.13 | 0.938 |

| Total protein (g dl–1, reference value: 6.7–8.3) | 7.0±0.5 | ||

| Albumin (g dl–1, reference value: 3.8–5.3) | 4.3±0.5 | ||

| Total bilirubin (mg dl–1, reference value: 0.2–1.2) | 0.5±0.2 | ||

| Platelet counts ( × 104 per μl, reference value: 14–35) | 22.1±5.5 |

Abbreviations: BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CPZeq, total antipsychotic dose in chlorpromazine equivalents; Cr, creatinine; f, female; m, male; PANSS, positive and negative symptom scale.

One patient was missing the total protein, albumin, total bilirubin and platelet counts data.

Predictors of indices of 13C-PBT

The results of the stepwise regression analyses are shown in Table 2. BW (β=−0.458, P=0.002) and diagnostic status (β=−0.281, P=0.047) were significant predictors of Cmax. BW (β=−0.503, P<0.001), age (β=0.295, P=0.023) and diagnostic status (β=−0.261, P=0.044) were significant predictors of AUC and entered into the final regression model. BW (β=−0.318, P=0.025), age (β=0.346, P=0.015) and diagnostic status (β=−0.304, P=0.032) were significant predictors of CRR0–120. Gender was not a significant predictor of any of these indices of 13C-PBT (data not shown).

Table 2. Stepwise multiple regression for L-[1-13C]phenylalanine breath test indices as dependent variables.

| Dependant variable | Predictor variablea | β | Adjusted r2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax | Body weight (kg) | −0.458 | 0.273 | 0.002 |

| Diagnostic statusb | −0.281 | 0.047 | ||

| AUC | Body weight (kg) | −0.503 | 0.396 | <0.001 |

| Age (year) | 0.295 | 0.023 | ||

| Diagnostic status | −0.261 | 0.044 | ||

| CRR0−120 | Body weight (kg) | −0.318 | 0.282 | 0.025 |

| Age (year) | 0.346 | 0.015 | ||

| Diagnostic status | −0.304 | 0.032 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the Δ13CO2-time curve; Cmax, the maximal Δ13CO2 (‰); CRR0−120, the cumulative recovery rate during the 120 min test.

Possible predictor variables included diagnostic status, sex, age and body weight.

Diagnostic status was measured on a nominal scale: 1=healthy control; 2=schizophrenia.

Decreased Cmax, AUC and CRR in schizophrenia

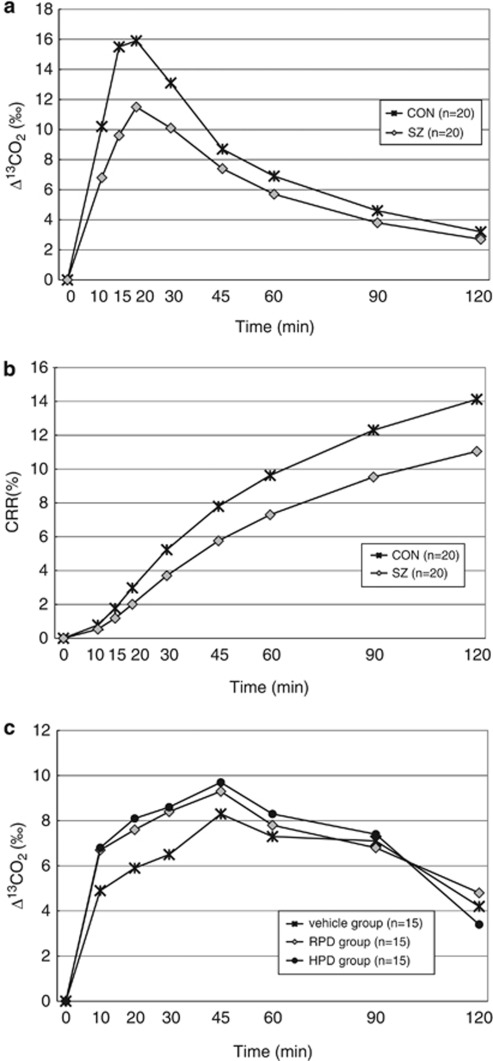

The results of the 13C-PBT are shown in Figure 2 as the time course of mean values of Δ13CO2 (Figure 2a) and CRR (Figure 2b) in the patients and controls. The repeated measures ANCOVA controlling for age and BW indicated a significant difference in Δ13CO2 over time between the two groups (F(1, 36)=4.57, P=0.039). The repeated measures ANCOVA with Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment revealed no significant interaction between the diagnostic status and sampling point (F(1.81, 65.04)=2.55, P=0.091). The repeated measures ANCOVA controlling for age and BW indicated a significant difference in CRR over time between the patients and controls (F(1, 36)=4.87, P=0.034). The repeated measures ANCOVA with Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment revealed a significant interaction between the diagnostic status and sampling point (F(1.09, 39.26)=4.73, P=0.033, Table 3), implying different patterns of change in CRR over time in the patients and controls. Δ13CO2 values were lower in the patients than in the controls at all sampling points during the 120 min test, with an overall significant difference between the two groups.

Figure 2.

(a) Time courses of 13CO2 excretion by schizophrenia patients and healthy controls during L-[1-13C]phenylalanine breath test. (b) Time courses of cumulative recovery rate (CRR; %) in schizophrenia patients and healthy controls during L-[1-13C]phenylalanine breath test. (c) Time courses of 13CO2 excretion by rats of vehicle group, risperidone (RPD) group and haloperidol (HPD) group during L-[1-13C]phenylalanine breath test. Values are expressed as mean. SZ, schizophrenic group; CON, control group; Time, time after ingesting the solution of L-[1-13C]phenylalanine (99 atom% 13C; 100 mg).

Table 3. Repeated measures analysis of covariance in schizophrenia patients and healthy controls for change in Δ13CO2 and CRR during the 120 min L-[1-13C]phenylalanine breath test.

| Parameter | Patients (n=20) | Controls (n=20) | Repeated measures ANCOVAa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±s.d. | Mean±s.d. | F | P | |

| Δ13CO2 | ||||

| Δ13CO2 at 10 min (‰) | 6.8±6.8 | 10.2±7.3 | ||

| Δ13CO2 at 15 min (‰) | 9.6±7.9 | 15.5±8.6 | ||

| Δ13CO2 at 20 min (‰) | 11.5±7.9 | 15.9±6.7 | ||

| Δ13CO2 at 30 min (‰) | 10.1±5.6 | 13.1±4.6 | ||

| Δ13CO2 at 45 min (‰) | 7.4±3.4 | 8.7±2.5 | ||

| Δ13CO2 at 60 min (‰) | 5.7±2.5 | 6.9±2.0 | ||

| Δ13CO2 at 90 min (‰) | 3.8±1.6 | 4.6±1.6 | ||

| Δ13CO2 at 120 min (‰) | 2.7±1.3 | 3.2±1.1 | ||

| Interactionb | 2.55 | 0.091 | ||

| Between group | 4.57 | 0.039 | ||

| CRR | ||||

| CRR at 10 min (%) | 0.5±0.5 | 0.8±0.5 | ||

| CRR at 15 min (%) | 1.2±1.1 | 1.8±1.1 | ||

| CRR at 20 min (%) | 2.0±1.6 | 3.0±1.5 | ||

| CRR at 30 min (%) | 3.7±2.5 | 5.2±2.1 | ||

| CRR at 45 min (%) | 5.8±3.3 | 7.8±2.6 | ||

| CRR at 60 min (%) | 7.3±3.8 | 9.6±2.9 | ||

| CRR at 90 min (%) | 9.5±4.6 | 12.3±3.5 | ||

| CRR at 120 min (%) | 11.0±5.1 | 14.1±4.0 | ||

| Interactionb | 4.73 | 0.033 | ||

| Between group | 4.87 | 0.034 | ||

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; CRR, the cumulative recovery rate.

Repeated measures analysis of covariance with age and body weight as covariates.

Interaction between diagnostic status and sampling point.

The Cmax was significantly lower in the patients than in the controls (t(38)=2.07, P=0.046) and remained significantly different in the ANCOVA controlling for age and BW (F(1, 36)=4.53, P=0.040). The Tmax did not differ significantly between the two groups (U=134.5, P=0.076, Mann–Whitney test). The AUC tended to be smaller in the patients than in the controls (t(38)=1.92, P=0.063); this trend became significant in the ANCOVA controlling for age and BW (F(1, 36)=4.37, P=0.044) and in the ANCOVA controlling for age, BW and ALT (F(1, 35)=6.25, P=0.017). The CRR0–120 was significantly smaller in the patients than in the controls (t(38)=2.12, P=0.041) and remained significant in the ANCOVA controlling for age and BW (F(1, 36)=4.99, P=0.032). These results are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Clinical variables and 13C-PBT in the patients

There was no significant correlation between each index of 13C-PBT and each value of liver blood tests in subjects (Supplementary Table S3).

We analyzed whether the symptom severity of schizophrenia and antipsychotic medication affected any patient indices of 13C-PBT. None of the Cmax, AUC or CRR0−120 in the patients correlated significantly with the PANSS total score or CPZeq (data not shown). Further, stepwise multiple regression analysis found only age to be a significant predictor of Cmax, AUC and CRR0−120, whereas no other variables, such as sex, BW, PANSS total score or CPZeq, ever entered into these regression models (Supplementary Table S4).

Animal experiments

We investigated whether typical or atypical antipsychotic medication affected any index of 13C-PBT in rats. The results of the 13C-PBT are shown in Figure 2c as the time course of the mean values of Δ13CO2 in the vehicle, RPD and HPD groups. A repeated measures ANOVA demonstrated no statistically significant main effect of group on Δ13CO2 (F(2, 42)=0.84, P=0.439, Supplementary Table S5). The repeated measures ANOVA with Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment revealed no significant interaction between the group and sampling point. Although mean Cmax and AUC values were lower in the vehicle group than in the RPD or HPD group, one-way ANOVA revealed no significant difference in Cmax or AUC between the experimental groups (Supplementary Table S6). Median Tmax did not differ among the three groups. Mean differences of Cmax among groups were as follows: vehicle vs RPD, 0.7‰ (95% CI, 4.0–2.6‰); vehicle vs HPD, 1.0‰ (95% CI, 3.3–1.3‰). Mean differences of AUC among groups were as follows: vehicle vs RPD, 84.1‰ (95% CI, 395.0–226.9‰); vehicle vs HPD, 107.8‰ (95% CI, 306.4–90.8‰). Median differences of Tmax among groups were as follows: vehicle vs RPD, 0 min (95% CI, 0–25 min); vehicle vs HPD, 0 min (95% CI, 0–15 min).

Discussion

We found significant differences in 13C-PBT indices between the schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Diagnostic status (schizophrenia/control) was found to be a significant predictor of the 13C-PBT indices Cmax, AUC and CRR0−120. A repeated measures ANCOVA controlling for age and BW revealed different patterns of change in CRR over time in the two groups; Δ13CO2 values (‰) were lower in the schizophrenia patients than in the controls at all sampling points during the 120 min test, with an overall significant difference between the two groups. In the patient group, none of Cmax, AUC or CRR0−120 was significantly correlated with symptom severity or dose of antipsychotic medication, and the animal experiments demonstrated that chronic administration of RPD or HPD had no significant effect on any index of 13C-PBT, indicating that the observed differences in the 13C-PBT indices were unlikely to be attributable to antipsychotic medication. To our knowledge, this is the first report that utilizes the 13C-PBT to demonstrate decreased phenylalanine kinetics in schizophrenia. Our results agree with previous reports of abnormal phenylalanine metabolism in schizophrenia.4, 8, 51

The 13C-PBT has been shown to be useful for assessing hepatic function and PAH activity, as phenylalanine is metabolized by PAH predominantly in the liver as well as in the kidney.11, 52, 53 Considering this effect, we screened the subjects and excluded those subjects with abnormal hepatic or renal parameters (that is, AST, ALT, ChE, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels of the patients and controls, and total protein, albumin, total bilirubin and platelet counts of the patients). ChE, in particular, was reported to be significantly correlated positively with the 13C-PBT results.52 We confirmed that there was no statistically significant difference in ChE between the patients and controls (Table 1). ALT was slightly, but significantly, increased in the patients compared with that in the controls (Table 1). However, the ALT levels in the patients were all within the normal range. Additionally, a previous study reported that ALT level did not correlate with 13C-PBT results.52 In our data, Pearson's correlation coefficients between indices of 13C-PBT (AUC, CRR0–120 and Cmax) and ALT in the patients were all close to 0 (r=0.01, r=0.09 and r=0.04, respectively; Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, when ANCOVA was conducted to compare AUC between the patients and controls, controlling for ALT as well as age and BW, the obtained P values for AUC decreased from 0.044 (ANCOVA controlling for age and BW, Supplementary Table S2) to 0.017 rather than increased. All these data ensure that increased ALT within the normal range was unrelated to the decreased 13C-PBT results observed in our patients. Besides ALT, none of indices of 13C-PBT correlated significantly with the liver blood test values in subjects (Supplementary Table S3). Therefore, the observed difference in the 13C-PBT indices between the patients and controls is unlikely to be attributable to impaired liver or kidney function in the patients.

In PKU, which shows decreased 13C-PBT indices,33, 34 excess phenylalanine occurs in the brain leading to competitive inhibition of the transport of other large neutral amino acids at the blood–brain barrier. The cerebral imbalance of phenylalanine and these amino acids has been thought to cause decreased synthesis of myelin and neurotransmitters in the brain, which could result in mental retardation and other brain dysfunctions, although the mechanism remains to be fully elucidated.54 The postulated pathogenesis of brain dysfunction in PKU could overlap that of schizophrenia. Our results suggest that treatment of phenylalanine imbalance may have a therapeutic potential in schizophrenia.

The Δ13CO2 measured in the 13C-PBT involves the amount of change in 13CO2 produced by the conversion of L-DOPA into dopamine, although this reaction is a quantitatively minor pathway for the synthesis of 13CO2 and occurs in both the brain and the periphery. The decreased 13C-PBT indices in schizophrenia may have resulted in part from decreased catecholamine synthesis. This could in turn lead to compensatory dopamine receptor supersensitivity, which is in line with the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia.51

The parameters measured by the 13C-PBT are influenced not only by the metabolic pathways mentioned above but also by other complicated physiologic and cell biological factors in vivo, including fasting period, gastric emptying rate, rate of digestive absorption, rate of uptake by the liver or kidneys, transport of phenylalanine and its metabolites across the plasma membrane.33 In the current study, Tmax was not significantly different between the patients and controls and the fasting period was consistent (that is, at least 10 h), suggesting that the indices were only marginally influenced by the rate of digestive absorption or the dietary composition.44

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small. Second, our subjects were all medicated, although both human and animal data showed no significant effect of antipsychotic medication on the 13C-PBT indices. Replication studies with a larger sample size, preferably including drug-free patients, are warranted. Third, the majority of the subjects were inpatients, implying that severe forms of schizophrenia were overrepresented in our sample.

In conclusion, the 13C-PBT provided evidence of altered whole-body kinetics of phenylalanine in neuroleptic-treated chronic schizophrenia. The 13C-PBT may detect a subgroup of schizophrenia patients whose phenylalanine kinetics is altered. Breath tests utilizing stable isotopes such as 13C-PBT are simple, noninvasive, economical and repeatable laboratory tools that can be applied to a variety of metabolic abnormalities and may drive innovation in future psychiatric practice.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants (Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health; H21-kokoro-002), an Intramural Research Grant (21-9) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of NCNP (HK) and a grant-in-aid for exploratory research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture (HK). We thank Dr Yasuhide Kakita, Dr Yuhi Yamada, Hirofumi Uchiyama, Mikako Kubo, Yoshihisa Honda, Akiko Chino, Takako Kodama, Yu Sakurada, Shigeko Okamura, Ikki Ishida, Takahiro Tomomori, Hidehiko Takeda, Toshiki Tani, Kyuichi Miyazaki, Anna Nagashima and Kenta Nozoe for assistance with the neuropsychological tests and recruitment of participants and all of the volunteers for their participation. We would also like to thank Hideji Nonomura and Dr Masayuki Uchida for their technical advice. We are grateful to Ms Misty Richards for her support and encouragement.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/tp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Howes OD, Kapur S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III—the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:549–562. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A. Dopamine as the wind of the psychotic fire: new evidence from brain imaging studies. J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13:358–371. doi: 10.1177/026988119901300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poisner AM. Serum phenylalanine in schizophrenia: biochemical genetic aspects. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1960;131:74–76. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao ML, Gross G, Strebel B, Bräunig P, Huber G, Klosterkötter J. Serum amino acids, central monoamines, and hormones in drug-naive, drug-free, and neuroleptic-treated schizophrenic patients and healthy subjects. Psychiatry Res. 1990;34:243–257. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(90)90003-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Xu H, Ramchand CN, Hemmings GP. Low concentrations of serum tyrosine in neuroleptic-free schizophrenics with an early onset. Schizophr Res. 1995;14:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)00080-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reveley MA, De Belleroche J, Recordati A, Hirsch SR. Increased CSF amino acids and ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22:413–420. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(87)90163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkin SG, Cannon-Spoor HE, DeLisi LE, Neckers LM, Wyatt RJ. Plasma phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:749–752. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060047006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O′Reilly R, Davis BA, Durden DA, Thorpe L, Machnee H, Boulton AA. Plasma phenylethylamine in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;30:145–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90168-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen PA, Leysen JE, Megens AA, Awouters FH. Does phenylethylamine act as an endogenous amphetamine in some patients. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;2:229–240. doi: 10.1017/S1461145799001522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufton S, Jennings I, Cotton R. Structure and function of the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases. Biochem J. 1995;311:353–366. doi: 10.1042/bj3110353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller N, Meek S, Bigelow M, Andrews J, Nair K. The kidney is an important site for in vivo phenylalanine-to-tyrosine conversion in adult humans: a metabolic role of the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1242–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlandsen H, Stevens RC. The structural basis of phenylketonuria. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;68:103–125. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scriver CR. The PAH gene, phenylketonuria, and a paradigm shift. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:831–845. doi: 10.1002/humu.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surtees R, Blau N. The neurochemistry of phenylketonuria. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:S109–S113. doi: 10.1007/pl00014370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrose LS. Inheritance of phenylpyruvic amentia (phenylketonuria) Lancet. 1935;226:192–194. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel F. Phenotypic deviations in heterozygotes of phenylketonuria (PKU) Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;177:337–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova LI. Frequency and phenotypic manifestations of schizophrenia in the parents of patients with phenylketonuria. Sov Genet. 1974;8:554–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell J, Heston L, Sommer S. Novel association approach for determining the genetic predisposition to schizophrenia: case-control resource and testing of a candidate gene. Am J Med Genet. 1993;48:28–35. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320480108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HM, Richardson MA. Aromatic amino acid hydroxylase genes and schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:626–630. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MA, Guttler F, Guldberg P, Reilly M, Suckow R, Read L, et al. Phenylalanine hydroxylase gene mutation associated with schizophrenia and African-American ethnic status Schizophr Res 1999b3695(abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MA, Guttler F, Guldberg P, Read L, Clelland J, Chao H, et al. Functional and psychiatric associations of the phenylalanine hydroxylase gene Molecular Psychiatry 19994(Suppl 1S41(abstract 41). [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MA, Read LL, Clelland JD, Chao HM, Reilly MA, Romstad A, et al. Phenylalanine hydroxylase gene in psychiatric patients: screening and functional assay of mutations. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:543–553. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, He L. Meta-analysis shows association between the tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) gene and schizophrenia. Hum Genet. 2006;120:22–30. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talkowski ME, McClain L, Allen T, Bradford LD, Calkins M, Edwards N, et al. Convergent patterns of association between phenylalanine hydroxylase variants and schizophrenia in four independent samples. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:560–569. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen SE, Fanous AH, Walsh D, O′Neill FA, Kendler KS. Polymorphisms in SLC6A4, PAH, GABRB3, and MAOB and modification of psychotic disorder features. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Stokes A, Roskoski RJ, Vrana K. Dopamine, in the presence of tyrosinase, covalently modifies and inactivates tyrosine hydroxylase. J Neurosci Res. 1998;54:691–697. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981201)54:5<691::AID-JNR14>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinski G, Kittner B, Bräutigam M. Direct inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase from PC-12 cells by catechol derivatives. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1986;332:346–350. doi: 10.1007/BF00500085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick P. Tetrahydropterin-dependent amino acid hydroxylases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:355–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Jia F, Yuan G, Chen Z, Yao J, Li H, et al. Tyrosine hydroxylase, interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are overexpressed in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from schizophrenia patients as determined by semi-quantitative analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2010;176:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro H, Arinami T, Saito T, Akazawa S, Enomoto M, Mitushio H, et al. Systematic search for variations in the tyrosine hydroxylase gene and their associations with schizophrenia, affective disorders, and alcoholism. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81:388–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunugi H, Kawada Y, Hattori M, Ueki A, Otsuka M, Nanko S. Association study of structural mutations of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene with schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease. Am J Med Genet. 1998;81:131–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Meer K, Roef M, Kulik W, Jakobs C. In vivo research with stable isotopes in biochemistry, nutrition and clinical medicine: an overview. Isotopes Environ Health Stud. 1999;35:19–37. doi: 10.1080/10256019908234077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treacy E, Delente J, Elkas G, Carter K, Lambert M, Waters P, et al. Analysis of phenylalanine hydroxylase genotypes and hyperphenylalaninemia phenotypes using L-[1-13C]phenylalanine oxidation rates in vivo: a pilot study. Pediatr Res. 1997;42:430–435. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntau AC, Röschinger W, Habich M, Demmelmair H, Hoffmann B, Sommerhoff CP, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin as an alternative treatment for mild phenylketonuria. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2122–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita S, Kajiwara M, Naruse H, Ohshima A, Higuchi T. 13C-Phenylalanine breath breath test using an infrared spectroscopy for detection of metabolic changes in depressive disorder. 13C medicine. 2002;12:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders4th ednAmerican Psychiatric Press: Washington DC; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 (Suppl 20:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsubo T, Tanaka K, Koda R, Shinoda J, Sano N, Tanaka S, et al. Reliability and validity of Japanese version of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:517–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TR.Isotope effect: implications for pharmaceutical investigationsIn: Brown TR (ed).Stable isotopes in pharmaceutical research Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam; 199713–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fulenwider J, Nordlinger B, Faraj B, Ivey G, Rudman D. Deranged tyrosine metabolism in cirrhosis. Yale J Biol Med. 1978;51:625–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchi R, Chiellini G, Scanlan TS, Grandy DK. Trace amine-associated receptors and their ligands. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:967–978. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison LK, Ezzeldin H, Carpenter M, Modak A, Johnson MR, Diasio RB. Rapid identification of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency by using a novel 2-13C-uracil breath test. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2652–2658. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano Y, Hase Y, Kawajiri M, Nishi Y, Inui K, Sakai N, et al. In vivo studies of phenylalanine hydroxylase by phenylalanine breath test: diagnosis of tetrahydrobiopterin-responsive phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:714–719. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000141520.06524.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Takatori K, Iida K, Higuchi T, Ohshima A, Naruse H, et al. Optimum conditions for the 13C-phenylalanine breath test. Chem Pharm Bull. 1998;46:1330–1332. doi: 10.1248/cpb.46.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki A, Inada T, Fujii Y, Yagi G, Yoshio T, Nakamura H, et al. Equivalent Dose of Psychotropics. Seiwa Shoten: Tokyo, Japan; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia. American Psychiatric Press: Washington DC; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wakade CG, Mahadik SP, Waller JL, Chiu FC. Atypical neuroleptics stimulate neurogenesis in adult rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:72–79. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HD, Dunnavant FD, Jarman T, Deutch AY. Effects of antipsychotic drugs on neurogenesis in the forebrain of the adult rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1230–1238. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt U, Dahmen N, Fischer V, Weigmann H, Rao ML, Reuss S, et al. Chronic oral haloperidol and clozapine in rats: a behavioral evaluation. Neuropsychobiology. 1999;39:86–91. doi: 10.1159/000026566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerkenstedt L, Edman G, Hagenfeldt L, Sedvall G, Wiesel FA. Plasma amino acids in relation to cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites in schizophrenic patients and healthy controls. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:276–282. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.3.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Furube M, Hirano S, Takatori K, Iida K, Kajiwara M. Evaluation of 13C-phenylalanine and 13C-tyrosine breath tests for the measurement of hepatocyte functional capacity in patients with liver cirrhosis. Chem Pharm Bull. 2001;49:1507–1511. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Suzuki S, Kohno T, Aoki M, Ito A, Takayama T, et al. L-[1-13C] phenylalanine breath test reflects phenylalanine hydroxylase activity of the whole liver. J Surg Res. 2003;112:38–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Spronsen FJ, Hoeksma M, Reijngoud DJ. Brain dysfunction in phenylketonuria: is phenylalanine toxicity the only possible cause. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:46–51. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0946-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.