Abstract

In this paper, a new dielectrophoresis (DEP) method based on capture voltage spectrum is proposed for measuring dielectric properties of biological cells. The capture voltage spectrum can be obtained from the balance of dielectrophoretic force and Stokes drag force acting on the cell in a microfluidic device with fluid flow and strip electrodes. The method was demonstrated with the measurement of dielectric properties of human colon cancer cells (HT-29 cells). From the capture voltage spectrum, the real part of Clausius–Mossotti factor of HT-29 cells for different frequencies of applied electric field was obtained. The dielectric properties of cell interior and plasma membrane were then estimated by using single-shell dielectric model. The cell interior permittivity and conductivity were found to be insensitive to changes in the conductivity of the medium in which the cells are suspended, but the measured permittivity and conductivity of cell membrane were found to increase with the increase of medium conductivity. In addition, the measurement of capture voltage spectrum was found to be useful in providing the optimum operating conditions for separating HT-29 cells from other cells (such as red blood cells) using dielectrophoresis.

INTRODUCTION

Biological cells have complicated internal and membrane structures. There are many factors that may affect the dielectric behavior of biological cells and tissues, such as the intracellular and membrane structure, membrane surface conductance, ions and molecules diffusion, and transport across membrane. The dielectric properties of biological cells are also frequency dependent, which are characterized by three dielectric dispersions, often referred to as α- (in the frequency region below a few kHz), β- (from kHz to MHz), and γ- (above MHz to GHz) dispersions.1 The most common approach to characterize cells is to use a core-shell dielectric model.2, 3, 4 For most biological cells consisting of cytoplasm and plasma membrane, spherical single-shell model has been widely used by researchers to represent blood cells5, 6 and cancer cells.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 In some cases, such as plants and most micro-organisms where the cell is surrounded by a cell wall, two-shell dielectric models were used.3 Some bacteria, like Escherichia coli, are rod-shape; hence, prolate spheroidal core-shell models12, 13 were developed and applied.14 Additionally, the biological membranes normally carry lipid, glycolipid, (glyco) protein membrane components, or charged molecules which are bound to or adsorbed onto the membrane surface.15 Hence, the net surface charge on the biological membranes is negative in most case. When the surface is immersed in an electrolyte, it attracts the ions of opposite charge and form an electric double layer.16 In the presence of an electric field, the counter ions inside the double layer migrate and become polarized, resulting in a change of dipole moment of cells. The double layer usually affects the dielectric properties of cells at low frequencies.

The dielectric properties of cells have been studied over decades. The most widely used technique for the analysis of cell suspensions is dielectric (impedance) spectroscopy. Dielectric spectroscopy is the direct measurement of permittivity and conductivity of heterogeneous systems as a function of frequency.17 Dielectric properties of various biological cells, such as mouse lymphocytes and erythrocytes,5 human erythrocytes,6, 18, 19 normal and malignant white blood cells,20 and leukemia cells,21 have been studied by this technique. However, dielectric spectroscopy is limited to the measurements of cell suspensions. For the analysis of a single cell, AC electrokinetics, which measures the movement of cells in electric fields, is more useful. One of AC electrokinetics techniques is electrorotation developed by Arnold and Zimmermann.22 It occurs when cells are subjected to a rotating electric field, and the dielectric properties of cells can be obtained by the measurement of the rate of rotation as a function of AC frequency.3, 7, 23 Another AC electrokinetics technique is dielectrophoresis (DEP), the movement of cells in non-uniform field. The DEP force can be either positive or negative depending on the value of Clausius–Mossotti (CM) factor. The dielectric properties of various cells have been estimated by measuring the DEP velocity spectrum,3 cross-over frequencies for different medium conductivity,12, 24, 25 or collection spectra.26, 27

From the collection of the dielectric properties obtained by above techniques, the typical value of cytoplasm relative permittivity and conductivity have been found in the range of 50-150 and 0.1-1.3 S/m, respectively; and the relative permittivity and conductivity of cell membrane were estimated to be around 2-15 and 10−8–10−4 S/m, respectively. The membrane thickness of biological cells is in the range of 4-10 nm.28, 29 The effects of surface charge distributions on the surface capacitance and conductance of lipid membrane have already been studied theoretically and experimentally.15, 17 Also, many theoretical models have been developed, which include the surface charge distributions in the calculation of dielectric properties of cell suspensions.30, 31, 32

To our knowledge, experimental measurement of cell properties with different ion concentrations in the surrounding medium has been limited in the literature. In the present study, cell dielectric properties were measured experimentally under different medium conductivities. We also established a new dielectrophoresis method to estimate the cell dielectric properties by measuring capture voltage spectrum where the DEP force and Stokes drag force are balanced.

The dielectric properties of cells, such as blood cells, breast cancer cells,7 and microorganisms,3, 12, 33 have been studied by many researchers. However, very few studies have been done on the dielectric properties of colon cancer cells. Colon cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world. The study of cell properties and separation of colon cancer cells from other biological materials is very important for cancer diagnosis. Here, HT-29 cell, one of the human colon cancer cell lines, was studied. Using the measured capture voltage spectrum, we are able to determine the dielectric properties of HT-29 cells and obtain the operating conditions for separating HT-29 cells from red blood cells (RBCs).

THEORY

For a sphere (with radius r, relative permittivity ɛs, and conductivity σs) suspended in a medium (with relative permittivity ɛm and conductivity σm) in an AC electric field, the time-averaged DEP force on the sphere is given by34, 35

| (1) |

where E is the amplitude of electric field, ɛ0 is the permittivity in vacuum, and ω (= 2πf) is the angular frequency of applied electric field. K*(ω) is the CM factor, which is given by

| (2) |

where the complex permittivities are given by and .

The direction of DEP force depends on the sign of the real part of CM factor. When the polarisability of sphere is greater than surrounding medium (Re[K*(ω)] > 0), the sphere experiences positive DEP force and moves towards the region of high electric field. When Re[K*(ω)] < 0, the sphere experiences negative DEP force and is repelled from the region of high electric field.

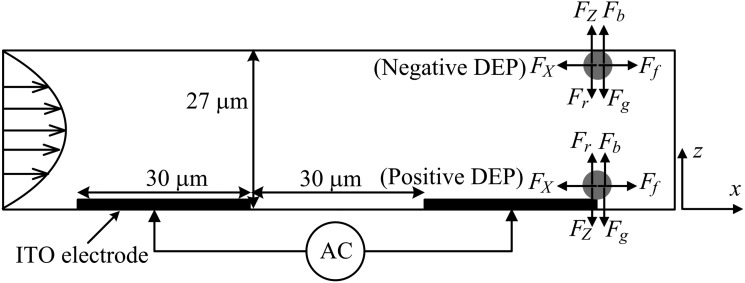

In the fluidic DEP device with interdigited microelectrodes (Fig. 1), the spheres experience the DEP forces in both the flow direction (FX) and vertical direction (FZ). The DEP force in the z-direction (FZ) will attract the cells to the edge of electrodes (under positive DEP) or repel the cells to top surface of channel (under negative DEP). The DEP force is usually larger than the difference of gravity force (Fg) and buoyancy force (Fb) of cells. In addition, the cell resting at the top or bottom surface of channel will experience a reaction force (Fr) to prevent it from moving in the z-direction. Hence, the cells will only move in the x-direction under the influence of the DEP force (FX) and Stokes drag force (Ff). The DEP force in the x-direction is given by

| (3) |

where V is the amplitude of AC voltage.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram (cross-sectional area of the channel) of DEP device and positions of captured cells under positive and negative DEP. FX: DEP force in the x-direction; FZ: DEP force in the z-direction; Ff: Stokes drag force; Fg: Gravity force; Fb: Buoyancy force; and Fr: Reaction force.

The Stokes drag force acting on the spherical particle is given by

| (4) |

where μ is the viscosity of fluid, uf is the local flow velocity, up is the velocity of the sphere, and c is the correction factor to account for near-wall effects. In the present study, the wall correction factor was calculated by the finite element software comsol to be 2.35.

For the channel dimension and flow velocity used in our experiments, the Reynolds number is less than 1 and the flow in the channel is completely laminar. The channel also has a large width to height aspect ratio of larger than 100. Hence, the fluid velocity profile in the channel height direction (z-direction) can be assumed to be parabolic. The local flow velocity for the sphere (one radius away from the bottom or top surface) is given by

| (5) |

where H is the height of channel, W is the width of channel, and Vflow is the volumetric flow rate.

For a fixed flow rate and frequency of applied electric field, there exists a critical voltage where the DEP force and Stokes drag force are balanced (up = 0). By measuring this critical voltage for different frequencies, we can estimate the real part of CM factor of the spheres,

| (6) |

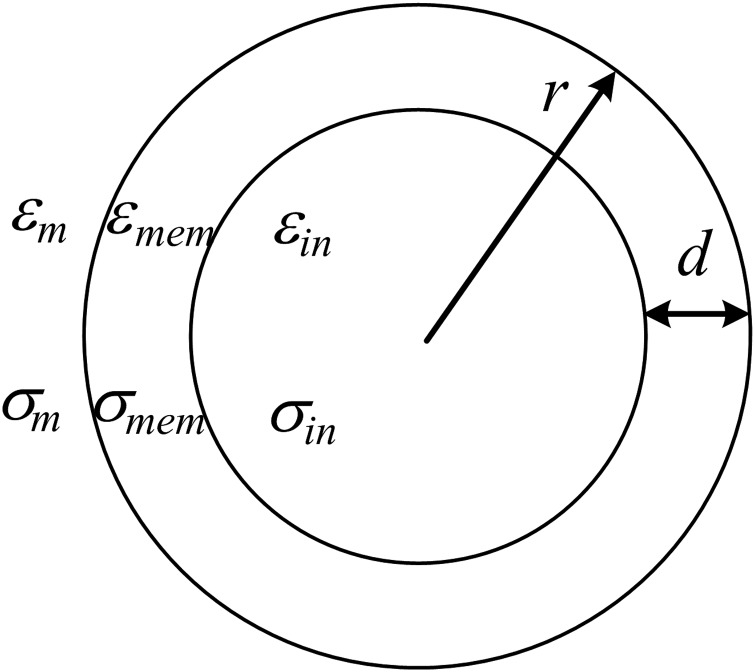

Biological cells that consist of cytoplasm and plasma membrane can be represented by the single-shell dielectric model (Fig. 2). For a cell suspended in a medium, the CM factor calculated with Eq. 2 can be obtained by substituting an effective complex permittivity for . The effective complex permittivity of a living cell (with radius r and membrane thickness d) is given by3

| (7) |

where the complex permittivities are given by and . The relative permittivity is denoted by ɛ and the conductivity denoted by σ, with the subscripts in and mem referring to the cell interior (cytoplasm) and cell membrane, respectively. With the spectrum of real part of CM factors calculated by Eq. 6, the four dielectric parameters of cells are estimated by nonlinear least square method with the Eqs. 2, 7.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of single-shell dielectric model used to represent a cell suspended in a medium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DEP device fabrication

The strip electrodes were fabricated from indium tin oxide (ITO) coated glass wafer. Positive photoresist AZ2001 is spin-coated at 1500 rpm on the ITO glass. The glass was baked at 95 °C for 2 min and then exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light at about 60 mJ/cm2 (Karl Suss MA4 Mask Aligner, Waterbury, VT, US) through a glass mask (IGI, Singapore). Subsequently, the glass was immersed into a solution of AZ400K and deionized water (1:3) for 1 min. After that, the glass was etched in a solution of ferric chloride (35 g), hydrochloric acid (37%, 250 ml), and deionized water (250 ml) for 12 min and then immersed in a 5% sodium carbonate solution to remove the surplus etching solution. After the etching process, the glass was rinsed with acetone and water to remove the photoresist.

The microfluidic channel with dimension of 20 (L) × 3 (W) × 0.027 (H) mm3 was fabricated by photolithography and micromolding technique. The master mold was produced by SU-8 3025 negative photoresist (Microchem Corp, US). SU-8 was spin-coated on a silicon wafer at 3000 rpm and then pre-baked at 95 °C for 10 min. The wafer was then exposed to UV light at about 150 mJ/cm2 through a film mask, baked at 65 °C for 1 min and at 95 °C for 3 min, and finally developed by SU-8 developer to remove the unexposed parts of SU-8. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Sylgard 184 silicone elastomer kit, Dow Corning, US) was poured onto the SU-8 master mold, baked in an oven (65 °C) for 1 h and then peeled off. Inlet and outlet holes were punched to access the microchannel. The PDMS microchannel was sealed with ITO glass by UV exposure.

Cell preparation and experimental setup

HT-29 cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in air, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin. For subculture, the cells were washed with 1 × phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA solution for 8 min at 37 °C to detach the cells from flask. The complete medium was then added to inhibit the effect of trypsin and the cells were washed by a centrifuge and resuspended in sucrose buffer (8.5% sucrose and 0.3% glucose) with conductivity of 0.01 S/m, 0.05 S/m, and 0.1 S/m, respectively. Horse red blood cells (i-DNA Biotechnology, Singapore) were washed and resuspended in 0.05 S/m sucrose buffer. Cells (∼106/ml) were pumped into the channel by a syringe pump (KDS Scientific, US). Sinusoid signal with amplitude up to 20 Vpp (peak to peak voltage, with high impedance) was applied to the electrodes by a universal signal generator (Agilent 33522 A, US). The voltage was increased slowly until a critical value (called capture voltage), where cells were just trapped by the electrode. At this capture voltage, the DEP force of cells is just equal to the Stokes drag force. The trapping positions of cells at both top and bottom surfaces of channel were shown in Fig. 1, depending on whether it is negative or positive DEP. The capture voltages (average values for cells with different sizes and from two different experiments) were obtained for the frequencies ranging from 5 kHz to 20 MHz.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Frequency spectrum of HT-29 cell capture voltage

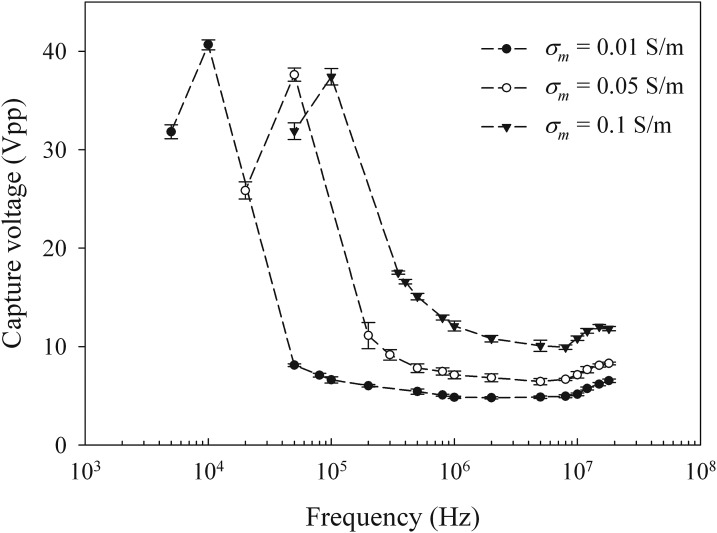

HT-29 cells in sucrose buffer with conductivity of 0.01 S/m, 0.05 S/m, and 0.1 S/m were injected to the DEP device in turn at a flow rate of 0.1 ml/h. The capture voltage was obtained for each conductivity at different frequencies of applied field (5 kHz-20 MHz for σm = 0.01 S/m, 20 kHz-20 MHz for σm = 0.05 S/m, and 50 kHz-20 MHz for σm = 0.1 S/m) (Fig. 3). The measurement was not conducted at very low frequencies since both electrode polarization and α-dispersion (tangential flow of ions on cell surface) would affect the DEP dielectric measurement. At the higher frequencies (>20 MHz), the trapping of cells was found to be unstable and this would affect the accuracy of capture voltage measurement.

Figure 3.

HT-29 cell capture voltage versus frequency of applied electric field with σm = 0.01 S/m, 0.05 S/m, and 0.1 S/m.

The cross-over frequencies (fc) were found around 25 kHz, 120 kHz, and 300 kHz for σm = 0.01 S/m, 0.05 S/m, and 0.1 S/m, respectively. At the cross-over frequency, the DEP force changes direction. When the frequency is bigger than fc, the cells experience positive DEP force and smaller voltage is needed to capture the cells. When the frequency is smaller than fc, the cells experience negative DEP force and very high voltage is needed to trap the cells. It is due to the cells being pushed to the top surface of channel, where the electric field is much weaker compared to that at the edge of electrodes. For a fixed medium conductivity, the capture voltage varies from the applied frequency due to different values of the CM factor. With the increase of medium conductivity, both capture voltage and cross-over frequency increase. Hence, cells become more difficult to be trapped in the high medium conductivity.

CM factor and dielectric properties of HT-29 cells

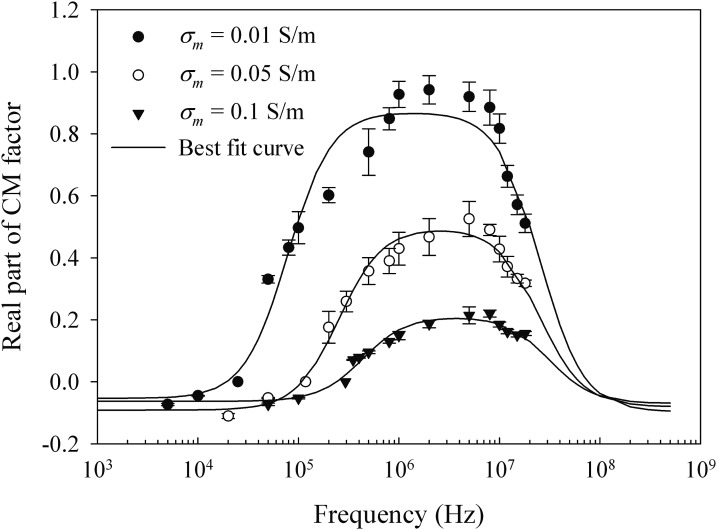

The real part of CM factors for different medium conductivities (Fig. 4) was calculated by Eq. 6 based on the data in Fig. 3. The parameters used in the calculation are listed in Table TABLE I.. The cell membrane thickness is assumed to be 5 nm. The real part of CM factor is negative when the frequency is less than fc and positive in the frequency range from fc to 80 MHz. The CM factors also change with the medium conductivity. With the lower medium conductivity, the cells have higher CM factors and, therefore, experience higher DEP force. A nonlinear least square method was used to estimate the four dielectric parameters of HT-29 cells (Table TABLE II.) by fitting the curves of real part of CM factors. In the low frequency range (< fc), cell membrane conductivity (σmem) contributes more to the real part of CM factors. When the frequency increases (fc to 10 MHz), changes in the real part of the CM factors are more related to the cell membrane permittivity (ɛmem) and cell interior conductivity (σin). At the high frequency range (>10 MHz), the influence of cell interior permittivity (ɛin) becomes dominant. Table TABLE II. also included the dielectric properties of several other types of cells reported by other researchers for comparison.

Figure 4.

Real part of CM factor of HT-29 cells versus frequency of applied electric field with σm = 0.01 S/m, 0.05 S/m, and 0.1 S/m.

TABLE I.

Parameters used for calculations.

| ɛ0 | 8.85 × 10−12 F/m |

| ɛm(water) | 78 |

| μ (water) | 1 × 10−3 Pa·s |

| H | 27 μm |

| W | 3 mm |

| r | 6.6 μm |

| d | 5 nm |

| c | 2.35 |

| 3.27 × 1013 V2/m3 | |

| 9.68 × 1012 V2/m3 |

TABLE II.

Estimated dielectric parameters of HT-29 cells and several other types of cells from literature.

| σm (S/m) | ɛmem | σmem (S/m) | ɛin | σin (S/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 4.68 ± 0.39 | (6.63 ± 0.024) × 10−6 | 58.31 ± 8.31 | 0.279 ± 0.032 |

| 0.05 | 6.01 ± 0.59 | (34.82 ± 1.36) × 10−6 | 61.14 ± 10.19 | 0.203 ± 0.017 |

| 0.1 | 7.67 ± 0.27 | (109.12 ± 0.50) × 10−6 | 63.27 ± 9.18 | 0.182 ± 0.006 |

| Other types of cells from literature | ||||

| Human breast cancer cell, MDA 231 (Ref. 7) | 14.69 ± 2.37 | NA | 52 ± 7.3 | 0.62 ± 0.073 |

| Mouse melanoma cell, B16F1 (Ref. 11) | 4.97 | 10−7 | 80.23 | 0.5 |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Ref. 20) | 7.4 ± 1.2 | (14.5 ± 4) × 10−6 | NA | NA |

| Human T-cell (Ref. 20) | 11.1 ± 1.4 | (27.4 ± 6.2) × 10−6 | NA | NA |

| RBC (Ref. 7) | 5.08 ± 0.45 | NA | 57 ± 5.4 | 0.52 ± 0.051 |

Cell interior conductivity was estimated to be around 0.18-0.28 S/m and was found to be insensitive to the conductivity of surrounding medium. With the use of isotonic sucrose buffer in the experiment, the cells do not gain or lose water. Hence, the ion concentration inside the cells would not change with the surrounding medium. Cell interior relative permittivity was determined mostly at high frequency range (>10 MHz) and was found to be approximately 58-63 with a relatively large standard deviation (±10). The large standard deviation is due to the lack of data points above 20 MHz. At the frequency above 20 MHz, the capture of cells is unstable. It is probably due to the γ-dispersion in this frequency range that is related to the rotation of water and protein molecules inside the cells. Gimsa et al. has reported that water bound to protein may have dispersions at the frequency around 15-20 MHz and cause dielectric displacement of cytoplasm.1, 36 With the increase in frequency, permittivity of cytoplasm would decrease and conductivity of cytoplasm would increase. The current single-cell model cannot explain this dispersion and a modified model is needed to explore the cell interior properties above 20 MHz.

The measured value of cell membrane relative permittivity (4.68 to 7.67) increases slightly with the increase of medium conductivity. The measured cell membrane conductivity increases from 6.63 × 10−6 S/m to 1.09 × 10−4 S/m when the medium conductivity increases from 0.01 S/m to 0.1 S/m. The change in cell membrane conductivity for different medium conductivity is approximately 1-2 orders of magnitude. The cell membrane itself is known to be insulating and has very low conductivity (<1 × 10−6 S/m15, 37, 38). However, the biological membrane is negatively charged and an electric double layer is formed on the cell surface. The electrical double layer acts as a capacitor and accumulates charges. The amount of surface charge can affect both the surface capacitance (permittivity) and conductance (conductivity) of membrane. The surface charge density is inversely proportional to Debye length, which is inversely proportional to the square root of medium conductivity.35 The increase of medium conductivity increases the surface charge density and the surface capacitance and conductance consequently. The Debye lengths were calculated to be approximately 11.75 nm, 5.25 nm, and 3.72 nm for σm = 0.01 S/m, 0.05 S/m, and 0.1 S/m, respectively. These Debye lengths are comparable to membrane thickness. This explains why the measured membrane permittivity and conductivity increase with the increase of medium conductivity since these two measured properties are effectively the sum of permittivity and conductivity of membrane as well as surface capacitance and conductance.

HT-29 cells and RBCs separation

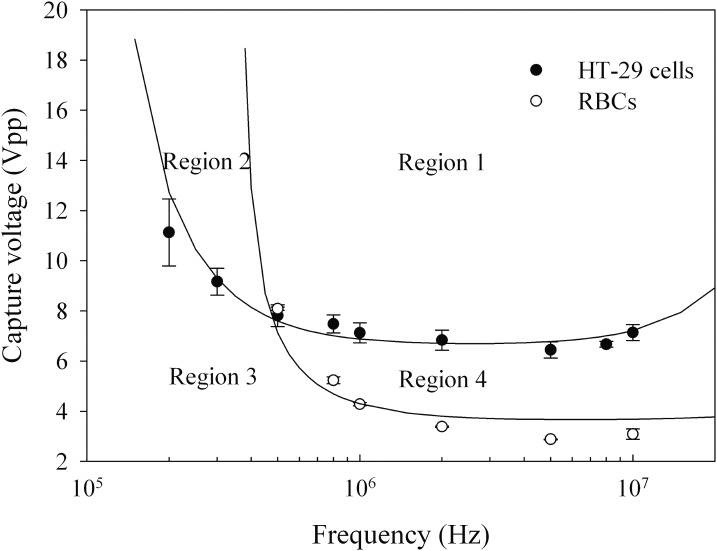

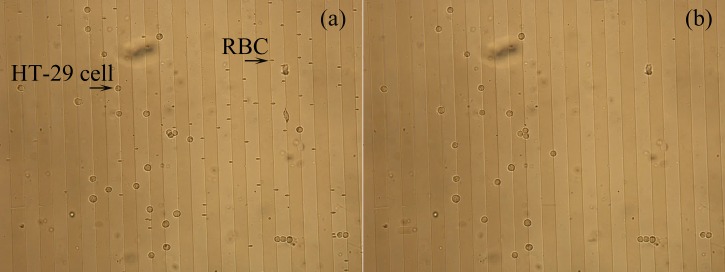

HT-29 cells and RBCs in 0.05 S/m sucrose buffer were injected to the DEP device at a flow rate of 0.1 ml/h. The spectra of capture voltage for both HT-29 cells and RBCs were obtained in the frequency range from 200 kHz to 10 MHz (Fig. 5). In this frequency range, cells are characterized by β-dispersion, avoiding both α- and γ-dispersion and electrode polarization. The cross-over frequencies were found to be around 120 kHz and 350 kHz for HT-29 cells and RBCs, respectively. For the frequencies above 120 kHz, four operational regions for cell handling are formed. When the electrical signal is adjusted to region “1,” both HT-29 cells and RBCs are captured at the edge of electrodes by positive DEP force (Fig. 6a). When the frequency is set between 150 kHz and 350 kHz and applied voltage is in the region “2” (below 20 Vpp), only HT-29 cells can be trapped and RBCs are released (Fig. 6b). RBCs experience negative DEP force below 350 kHz, and the applied voltage is not large enough to trap them. Hence, RBCs are pushed away from the electrodes by the fluid flow. HT-29 cells experience a strong positive DEP force above 150 kHz, so they can still be trapped by electrodes. When the electrical signal is adjusted to region “4,” only RBCs are trapped and HT-29 cells are released (images not shown). In this area, the voltage is large enough to trap RBCs, but not sufficient to capture the HT-29 cells. Hence, HT-29 cells and RBCs can be separated by choosing proper electric voltage and frequency based on their capture voltage spectra.

Figure 5.

Capture voltages of HT-29 cells and RBCs versus frequency of applied electric field with σm = 0.05 S/m.

Figure 6.

Images of HT-29 cells and RBCs separation with σm = 0.05 S/m. (a) f = 5 MHz and V = 10 Vpp, both HT-29 cells and RBCs were captured; (b) f = 300 kHz and V = 12 Vpp, RBCs were released.

CONCLUSION

The dielectric properties of HT-29 colon cancer cells were measured using dielectrophoretic capture voltage spectrum under various medium conductivities. The measurements of the cell interior permittivity and conductivity are insensitive to the change of medium conductivity. However, the measured permittivity and conductivity of cell membrane increase with the increase of medium conductivity. This dependence can be explained by the electric double layer theory. Additionally, the measured dielectric properties are valid for cells working in the middle frequency range (β-dispersion). Furthermore, with different capture voltage spectra between colon cancer cells and RBCs, the separation of these cells by dielectrophoresis under optimal operating conditions was demonstrated. The method presented in this paper has great potential for the measurement of dielectric properties of many types of biological cells and determining the optimal operating conditions for separating these cells using DEP based on their different capture voltage spectra.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is partially supported by the Singapore-MIT Alliance Computational Engineering program and the NRF (EWI) Research Grant (0803-IRIS-02) from Singapore. The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Wang Zhenfeng’s kind help for using their microfabrication facilities at A*STAR SIMTech. The authors also gratefully acknowledge Dr. Liu Yang for his helpful discussions.

References

- Schwan H. P., Adv. Biol. Med. Phys. 5, 147 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irimajiri A., Hanai T., and Inouye A., J. Theor. Biol. 78, 251 (1979). 10.1016/0022-5193(79)90268-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Holzel R., Pethig R., and Wang X.-B., Phys. Med. Biol. 37, 1499 (1992). 10.1088/0031-9155/37/7/003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethig R., Biomicrofluidics 4, 022811 (2010). 10.1063/1.3456626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asami K., Takahashi Y., and Takashima S., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1010, 49 (1989). 10.1016/0167-4889(89)90183-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordi F., Cametti C., and Biasio A. D., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1028, 201 (1990). 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90154-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker F. F., Wang X. B., Huang Y., Pethig R., Vykoukal J., and Gascoyne P. R., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 860 (1995). 10.1073/pnas.92.3.860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R. C., Noshari J., Anderson T. J., and Becker F. F., Electrophoresis 30, 1388 (2009). 10.1002/elps.v30:8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabuncu A. C., Liu J. A., Beebe S. J., and Beskok A., Biomicrofluidics 4, 021101 (2010). 10.1063/1.3447702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen C.-P. and Chang H.-H., Biomicrofluidics 5, 034101 (2011). 10.1063/1.3609263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oblak J., Križaj D., Amon S., Maček-Lebar A., and Miklavčič D., Bioelectrochemistry 71, 164 (2007). 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellarnau M., Errachid A., Madrid C., Juárez A., and Samitier J., Biophys. J. 91, 3937 (2006). 10.1529/biophysj.106.088534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai W., Zhao K. S., and Asami K., Biophys. Chem. 122, 136 (2006). 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R. S., Chang H.-C., and Revzin A., Biomicrofluidics 5, 032005 (2011). 10.1063/1.3608135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cevc G., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1031, 311 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyklema J., Fundamentals of Interface and Colloid Science, Solid-Liquid Interfaces Vol. II (Academic, San Diego, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Coster H. G. L., Chilcott T. C., and Coster A. C. F., Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 40, 79 (1996). 10.1016/0302-4598(96)05064-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beving H., Eriksson L. E. G., Davey C. L., and Kell D. B., Eur. Biophys. J. 23, 207 (1994). 10.1007/BF01007612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordi F., Cametti C., Misasi R., Persio R. D., and Zimatore G., Eur. Biophys. J. 26, 215 (1997). 10.1007/s002490050074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polevaya Y., Ermolina I., Schlesinger M., Ginzburg B.-Z., and Feldman Y., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1419, 257 (1999). 10.1016/S0005-2736(99)00072-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irimajiri A., Asami K., Ichinowatari T., and Kinoshita Y., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 896, 203 (1987). 10.1016/0005-2736(87)90181-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold W. M. and Zimmermann U., J. Electrost. 21, 151 (1988). 10.1016/0304-3886(88)90027-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holzel R. and Lamprecht I., Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1104, 195 (1992). 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90150-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszalek P., Zielinsky J. J., Fikus M., and Tsong T. Y., Biophys. J. 59, 982 (1991). 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82312-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marszałek P., Zieliński J. J., and Fikus M., Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 22, 289 (1989). 10.1016/0302-4598(89)87046-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchis A., Brown A. P., Sancho M., Martínez G., Sebastián J. L., Muñoz S., and Miranda J. M., Bioelectromagnetics 28, 393 (2007). 10.1002/(ISSN)1521-186X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoyne P. R. C., Noshari J., Becker F. F., and Pethig R., IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 30, 829 (1994). 10.1109/28.297896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hochmuth R., Evans C., Wiles H., and McCown J., Science 220, 101 (1983). 10.1126/science.6828875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markx G. H. and Davey C. L., Enzyme Microb. Technol. 25, 161 (1999). 10.1016/S0141-0229(99)00008-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chew W. C., J. Chem. Phys. 80, 4541 (1984). 10.1063/1.447239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prodan E., Prodan C., and Miller J. H., Biophys. J. 95, 4174 (2008). 10.1529/biophysj.108.137042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Biasio A. and Cametti C., Phys. Rev. E 82, 021917 (2010). 10.1103/PhysRevE.82.021917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markx G. H., Huang Y., Zhou X.-F., and Pethig R., Microbiology 140, 585 (1994). 10.1099/00221287-140-3-585 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones T. B., Electromechanics of Particles (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- Morgan H. and Green N. G., AC Electrokinetics: Colloids and Nanoparticles (Research Studies Press Ltd., Baldock, Hertfordshire, England, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Gimsa J., Muller T., Schnelle T., and Fuhr G., Biophys. J. 71, 495 (1996). 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79251-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwan H. P., Takashima S., Miyamoto V. K., and Stoeckenius W., Biophys. J. 10, 1102 (1970). 10.1016/S0006-3495(70)86356-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolina I., Polevaya Y., and Feldman Y., Eur. Biophys. J. 29, 141 (2000). 10.1007/s002490050259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]