Abstract

BACKGROUND

Somatostatinomas are rare neuroendocrine tumours with an annual incidence of 1 in 40 million. They arise in the pancreas or periampullary duodenum. Most are clinically non-secretory and do not cause the somatostatinoma syndrome. Many are metastatic at presentation and their management is typically multimodal.

CASE HISTORIES

Four cases of somatostatinoma are described. Two patients with periampullary disease presented with biliary obstruction, one with frank jaundice and one with incidental bile duct obstruction on investigation of hepatitis B. Each patient had type 1 neurofibromatosis and resection of the somatostatinoma by means of a pylorus-preserving proximal pancreaticoduodenectomy has resulted in long-term survival. Another two patients with metastatic pancreatic somatostatinomas presented with abdominal pain. Contrasting management illustrates current treatment strategies that are dependent in part on the distribution of the disease.

DISCUSSION

The pathophysiology, presentation, clinical associations and role of diagnostic imaging are discussed for periampullary and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Operative treatment has an important role in both the curative and palliative settings in conjunction with appropriate medical treatments and these are described. Management options depend on the extent of the disease and the cases are used to illustrate the rationale of such strategies.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine tumor, Somatostatinoma

Somatostatinomas are rare neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) with an incidence of 1 in 40 million. These unusual tumours arise predominantly in the pancreas and peripancreatic duodenum and patients often present with non-specific symptoms. Rarely, patients present with somatostatinoma syndrome (diabetes, gallstones and steatorrhoea) when the tumour is secretory.

Four patients with somatostatinomas (two periampullary in origin and two pancreatic) illustrate the contrasting presentations of this rare disease, providing an opportunity to discuss the current options for the surgical and oncological management of this rare condition.

Case History 1

During routine occupational health screening, an asymptomatic 50-year-old nurse was found to be hepatitis B positive. Clinical examination was unremarkable aside from multiple cutaneous fibromas and café-au-lait spots in keeping with a known diagnosis of type 1 neurofibromatosis (NF1). While the liver biochemistry and gut hormone profile was normal, ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated biliary and pancreatic duct dilatation (common bile duct 7.4mm, pancreatic duct 7mm) and a 3.5cm soft tissue mass situated between the right kidney and pancreas. Subsequent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated an ampullary mass; biopsies suggested a carcinoid tumour with foci of an adenocarcinoma. Neuroendocrine differentiation in an ampullary lesion in a patient with NF1 led to a putative diagnosis of an ampullary somatostatinoma.

At laparotomy, a small mobile mass at the duodenal papilla and a 5cm tumour arising from the left adrenal gland were identified. Alpha blockade was required to mitigate the effects of handling the tumour during extirpation, indicating a functional adrenal neoplasm. A partial adrenalectomy was combined with a pylorus preserving partial pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPP). Histological examination demonstrated complete excision of a 1.3cm ampullary somatostatinoma (Fig 1) as well as a left adrenal phaeochromocytoma. The patient made a good recovery and remains well 13 years later, with no evidence of recurrence.

Figure 1.

Microscopic appearances of ampullary somatostatinoma (case 1); haematoxylin and eosin staining (left) and strongly positive immunostaining with somatostatin (right)

Case History 2

A 46-year-old man presented with painless obstructive jaundice and weight loss. Ultrasonography demonstrated a dilated biliary tree and subsequent ERCP suggested an obstructing ampullary tumour although biopsies were negative for malignancy. The patient subsequently underwent a laparotomy at which the tumour was thought to be arising in the pancreatic head and was deemed unresectable. During assessment for palliative radiotherapy, a strong family history of NF1 was elicited and an alternative diagnosis of a NET was sought. The patient was then referred to a specialist centre for further opinion.

Table 1.

Tumour characteristics of four patients with somatostatinomas

| © | Age (years) | Presentation | Tumour location | Tumour size | Spread | Association | Survival |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | Incidental | Ampulla | 1.3cm | Nil | NF1 | 13 years* |

| 2 | 46 | Painless jaundice and weight loss | Periampullary (x2 lesions) | 1.5cm 2.2cm | Local lymph node involvement (3/13) | NF1 | 11 years* |

| 3 | 34 | Right upper quadrant and epigastric pain | Head of pancreas | 3cm | Liver: bilobar spread | Nil | 3 months* |

| 4 | 69 | Right upper quadrant pain (?incidental) | Body of pancreas | 1.3cm | Liver: bilobar spread | Nil | New diagnosis |

NF1 = type 1 neurofibromatosis

still alive

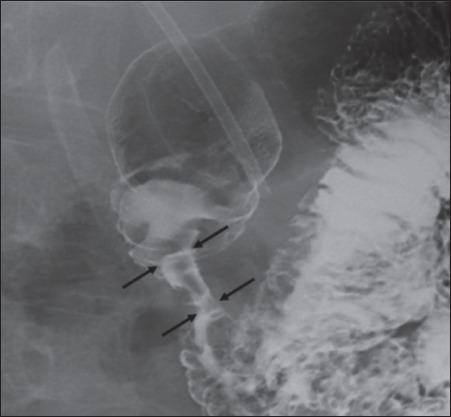

Repeat CT failed to demonstrate any pancreatic mass or contraindication to resection, while a barium meal and endoscopy again suggested a duodenal origin (Fig 2). The gut hormone profile was negative and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 was marginally elevated (37pmol/l, normal <33pmol/l). A second laparotomy demonstrated a small obstructing ampullary mass with marked distal obstructive pancreatopathy but no evidence of distant spread. PPPP was performed. The patient recovered quickly and remains well 11 years later, with no evidence of recurrence.

Figure 2.

Barium meal showing stricture of descending duodenum (black arrows) (case 2)

Case History 3

A 34-year-old man presented with severe right upper quadrant pain and dyspepsia of 4 months' duration. Abdominal examination revealed 2cm hepatomegaly. Serum biochemistry was unremarkable except for an elevated alanine transferase (77iu/l: normal <40iu/l). Initial CT demonstrated a contrast enhancing 1cm lesion in the right liver and a cystic lesion in the tail of the pancreas.

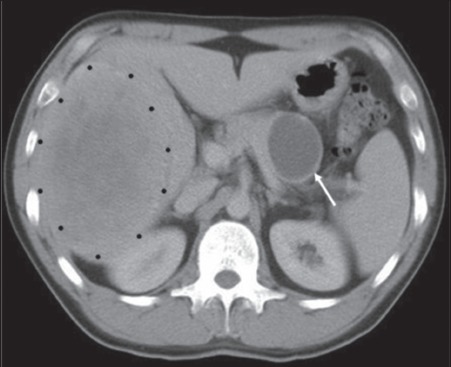

Further investigation at a specialist hepatobiliary centre revealed negative hepatitis serology, a negative autoantibody screen and negative tumour markers. CT confirmed a 4cm × 4cm × 6cm cystic lesion in the tail of the pancreas, with no vascular involvement or lymphadenopathy, and a 14cm hepatic mass (Fig 3). A percutaneous liver biopsy suggested a metastatic somatostatinoma (on immunohistochemical analysis). The pancreatic lesion was sampled at endoscopic ultrasonography: cyst fluid analysis revealed high amylase (>17,000iu/l), an elevated CA19-9 (326pmol/l), normal carcinoembryonic antigen and no malignant cells. An octreotide scan demonstrated intense up-take in both the distal pancreas and right liver.

Figure 3.

Computed tomography showing both a cystic pancreatic primary (white arrow) and large volume right hepatic secondary tumour (black dots) (case 3)

The patient underwent preoperative right portal vein embolisation to compensate for a functionally inadequate left lobe. At laparotomy, multiple small (5mm) irregular nodules were sampled and shown to contain a NET on frozen section. A distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy was performed, combined with radiofrequency ablation-assisted right hepatectomy. Histological examination demonstrated a low grade primary pancreatic NET with metastatic disease in the liver. Immunohistochemistry showed strong staining for somatostatin and synaptophysin. The patient made a slow post-operative recovery and has received adjuvant therapy with streptozotocin.

Case History 4

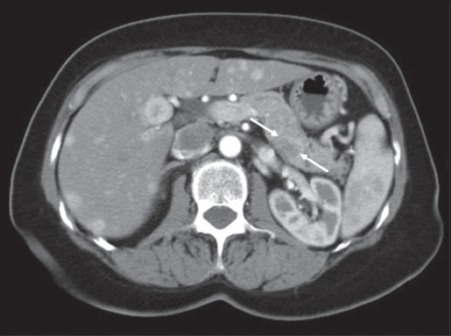

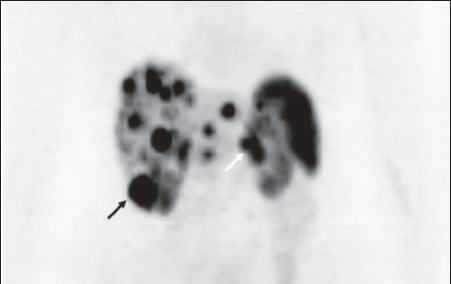

A 69-year-old woman with a two-month history of right hypochondrial pain underwent abdominal ultrasonography that showed gallstones in a thick walled gallbladder and a right renal mass. CT unexpectedly identified multiple hypervascular lesions within the liver and a 13mm low density lesion in the body of the pancreas as well as a 2.3cm right renal mass (Fig 4). A subsequent liver biopsy demonstrated a metastatic NET. Intense staining for somatostatin in the absence of staining for vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, gastrin, insulin and glucagon confirmed the diagnosis of a low grade somatostatinoma. Elevated levels of chromogranin A and B (only) in the blood supported the diagnosis of a non-functioning NET. Subsequent positron emission tomography (PET) and octreotide scans confirmed bilobar liver and extrahepatic disease (Fig 5) as seen on CT. The patient is preparing for primary treatment with either streptozotocin-based chemotherapy or radiolabelled octreotide.

Figure 4.

Computed tomography showing a lesion in the posterior body of pancreas (white arrows) and multiple hypervascular lesions throughout the liver (case 4)

Figure 5.

Positron emission tomography showing extensive hepatic metastases as well as uptake in the inferior pole of the right kidney (black arrow) and the pancreatic primary tumour (white arrow) (case 4)

Discussion

Somatostatin is a cyclic peptide of 14 amino acids that is secreted from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and delta cells of the pancreas under physiological conditions. Its release results in a general inhibition of other GI hormones including insulin, glucagon, cholecystokinin and gastrin via paracrine modulation and a reduction in splanchnic perfusion. These effects may have therapeutic benefits and analogues such as octreotide and lanreotide are used in a variety of clinical contexts including the palliation of vomiting, symptomatic control in neuroendocrine and thyroid tumours, and prevention of complications following pancreatic surgery.

First described in 1977, a somatostatinoma is a rare NET with an incidence of 1 in 40 million.1 A mean of 8 cases are reported in the worldwide literature annually.2 It is typically a solitary tumour situated in the pancreas or periampullary duodenum;3 there have been occasional reports of lesions in the colon and rectum.4,5 The gender distribution is equal and the tumour may be functional or non-functional.3,6 Functional tumours may induce the somatostatinoma syndrome of diabetes, gallstones and steatorrhoea, resulting from the suppressive effect of the hormone on insulin, cholecystokinin and pancreatic exocrine function respectively. The syndrome is rare and most tumours present either with obstructive symptoms or as an incidental abnormality during endoscopy or cross-sectional imaging. The expression of somatostatin receptors does not indicate that a tumour is functional. Three-quarters (78%) of somatostatinomas are malignant and the great majority of these (70–92%) present with metastatic disease.7,8 There are no known environmental risk factors.

Somatostatinomas are less frequently associated (1%) with multiple endocrine neoplasia than other NETs of the pancreas.9 However, duodenal somatostatinomas are commonly associated with NF1 in up to 50% of cases and this association appears to be associated with a lower risk of metastasis at presentation.3,8 A phaeochromocytoma should be sought and excluded in patients with NF1 presenting with a duodenal somatostatinoma since there is a well recognised association between these three diseases.10

Imaging for a suspected somatostatinoma, which typically presents at a size of 5cm, commences with either CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Although the tumour is isodense (and therefore not visible on unenhanced CT), a hypervascular lesion is characteristic with intravenous contrast enhancement.11 Dual phase CT and MRI have equivalent sensitivities for the detection of NETs of the pancreas although MRI is considered superior for the detection of liver and bony metastases.12

Endoscopic ultrasonography enables biopsy and assessment of vascular involvement. This technique is the optimal modality for localisation of pancreatic lesions as it is able to discriminate lesions as small as 5mm although the tail can be inaccessible. Somatostatin subtype 2 receptors are expressed in approximately 80% of all gastroenteropancreatic NETs.13,14 Indium-labelled octreotide (111In-octreotide) has a high sensitivity for the identification of primary gastrinoma and metastases (over 2cm diameter) and is generally considered a useful preoperative localisation technique for all pancreatic NETs except insulinoma.9,15 Elevated plasma levels of chromogranin A or pancreatic polypeptide are found in 50–80% of patients and are non-specific markers of pancreatic NETs.9 Elevated circulating levels of somatostatin (>14mmol/l) are strongly indicative of a somatostatinoma but are rarely found.16

Surgical resection is indicated either when a somatostatinoma is deemed resectable or as part of a debulking treatment for patients with metastatic disease in whom removal of >90% of the tumour volume is anticipated.17 As most somatostatinomas are located in the periampullary duodenum or pancreatic head, a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy is the most common resection although a total pancreaticoduodenectomy may be required. Since a high proportion of patients present with metastatic disease, the role of debulking has been carefully examined.17,18 Only 65% of cases that proceeded to operation in a historical series were in fact macroscopically resectable.19

Aggressive surgical resection of hepatic metastatic disease has been associated with improved outcome compared with alternative therapies such as hepatic artery embolisation (HAE), radiofrequency ablation or radioactive octreotide. The five-year survival rate after surgical resection of hepatic metastases has been shown to be 76% compared with 50% for HAE and 26% for medical therapy.17 Complete resection of hepatic metastases improves survival threefold compared with incomplete resection.20 Half those patients with ‘tumour bulk’ symptoms (eg pain and vomiting) from a functional tumour describe benefit from surgical debulking of the tumour (with a mean duration of 39 months), compared with the best combination chemotherapy offering a median survival of 26 months.17,21

Overall, the five-year survival rate for patients with pancreatic and periampullary somatostatinomas is 60–100% with localised disease or 15–60% with metastatic disease.6,22–24 Large size (>3cm), poor differentiation and lymph node involvement are poor prognostic markers. Tumours that are hormonally inactive (non-functioning) predominate and, being typically poorly differentiated, have a worse prognosis than functioning somatostatinomas.

Summary

The clinical presentations of the four cases of somatostatinomas illustrate some important points regarding this disease. The non-functioning duodenal somatostatinoma in case 1, causing partial biliary obstruction, was discovered incidentally. Despite the absence of a duodenal mass lesion on CT, the presence of NF1 raised the possibility of a somatostatinoma: the presence of a phaeochromocytoma illustrates another facet of von Recklinghausen's disease.

The periampullary somatostatinoma in case 2 presented with icterus. Over 50% of these lesions present with jaundice and the tumour was hormonally silent. Despite poor histological features (pancreatic parenchymal invasion and lymph node metastasis), the patient remains well 11 years following surgery.

In case 3 the presenting symptoms were from large volume metastatic disease in the right lobe of the liver and an asymptomatic, non-functioning primary tumour in the pancreatic tail. Pancreatic somatostatinomas are more commonly functional than duodenal. Despite multimodal preoperative imaging including octreotide scintigraphy, multiple small volume lesions in the left liver were not identified until laparotomy: lesions <2cm are not reliably identified by this modality. Debulking surgery removed more than 90% of the disease burden.

The last patient had disseminated disease in the pancreas, right kidney and both lobes of the liver. The actual symptom (pain) may have reflected concurrent gallstones rather than the extensive somatostatinoma. Since meaningful debulking was unachievable, the patient is being treated with primary chemo- or radiotheraputic means.

References

- 1.Ganda OP, Weir GC, Soeldner JS, et al. ‘Somatostatinoma’: a somatostatin-containing tumor of the endocrine pancreas. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:963–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197704282961703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.House MG, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD. Periampullary pancreatic somatostatinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:869–874. doi: 10.1007/BF02557523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao C, Shah A, Hanson DJ, Howard JM. Von Recklinghausen's disease associated with duodenal somatostatinoma: contrast of duodenal versus pancreatic somatostatinomas. J Surg Oncol. 1995;59:67–73. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930590116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ectors N. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: diagnostic pitfalls. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:679–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris GJ, Tio F, Cruz AB., Jr Somatostatinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1987;36:8–16. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930360104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soga J, Yakuwa Y. Somatostatinoma/inhibitory syndrome: a statistical evaluation of 173 reported cases as compared to other pancreatic endocrinomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 1999;18:13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinik AI, Strodel WE, Eckhauser FE, et al. Somatostatinomas, PPomas, neurotensinomas. Semin Oncol. 1987;14:263–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doherty GM. Rare endocrine tumours of the GI tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberg K, Eriksson B. Endocrine tumours of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:753–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappelli C, Agosti B, Braga M, et al. Von Recklinghausen's neurofibromatosis associated with duodenal somatostatinoma. A case report and review of the literature. Minerva Endocrinol. 2004;29:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King CM, Reznek RH, Dacie JE, Wass JA. Imaging islet cell tumours. Clin Radiol. 1994;49:295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81790-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Debray MP, Geoffroy O, Laissy JP, et al. Imaging appearances of metastases from neuroendocrine tumours of the pancreas. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:1065–1070. doi: 10.1259/bjr.74.887.741065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angeletti S, Corleto VD, Schillaci O, et al. Use of the somatostatin analogue octreotide to localise and manage somatostatin-producing tumours. Gut. 1998;42:792–794. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reubi JC. Neuropeptide receptors in health and disease: the molecular basis for in vivo imaging. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1825–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Termanini B, Gibril F, Reynolds JC, et al. Value of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: a prospective study in gastrinoma of its effect on clinical management. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:335–347. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9024287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakamoto T, Miyata M, Izukura M, et al. Role of endogenous somatostatin in postprandial hypersecretion of neurotensin in patients after gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 1997;225:377–381. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamberlain RS, Canes D, Brown KT, et al. Hepatic neuroendocrine metastases: does intervention alter outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:432–445. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anene C, Thompson JS, Saigh J, et al. Somatostatinoma: atypical presentation of a rare pancreatic tumor. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:819–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konomi K, Chijiwa K, Katsuta T, Yamaguchi K. Pancreatic somatostatinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1990;43:259–265. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930430414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen H, Hardacre JM, Uzar A, et al. Isolated liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors: does resection prolong survival? J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:88–92. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moretel CG, Lefkopoulo M, Lipsitz S, et al. Streptozocin-doxorubicin, streptozocin-fluorouracil or chlorozotocin in the treatment of advanced islet-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:519–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansour JC, Chen H. Pancreatic endocrine tumors. J Surg Res. 2004;120:139–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamy A, Heymann MF, Bodic J, et al. Duodenal somatostatinoma. Anatomic/clinical study of 12 operated cases. Ann Chir. 2001;126:221–226. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(01)00493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Brien TD, Chejfec G, Prinz RA. Clinical features of duodenal somatostatinomas. Surgery. 1993;114:1144–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]