Abstract

Macrophages function both under normothermia and during periods of body temperature elevation (fever). Whether macrophages sense and respond to thermal signals in a manner which regulates their function in a specific manner is still not clear. In this brief review, we highlight recent studies which have analyzed the effects of mild heating on macrophage cytokine production, and summarize thermally sensitive molecular mechanisms, such as heat shock protein (HSP) expression, which have been identified. Mild, physiologically achievable, hyperthermia has been shown to have both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects on macrophage inflammatory cytokine production and overall it is not clear how hyperthermia or HSPs can exert opposing roles on macrophage function. We propose here that the stage of activation of macrophages predicts how they respond to mild heating and the specific manner in which HSPs function. Continuing research in this area is needed which will help us to better understand the immunological role of body temperature shifts. Such studies could provide a scientific basis for the use of heat in treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: inflammation, hyperthermia, heat shock protein, fever, heat shock factor, cytokines, arthritis

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation is usually considered a beneficial event which helps to heighten the immune response initiated following tissue injury or infection. Molecular alarm signals generated from the damaged tissues or invading pathogens are recognized by antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as macrophages. Macrophages are key players in innate immunity and respond rapidly to danger signals generated from inflamed sites. Recognition of these danger signals through specific cell surface pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on macrophages results in the production of anti-microbial products as well as pro-inflammatory mediators (Depraetere, 2000; Fujiwara and Kobayashi, 2005).

Inflammation is a tightly regulated process with production of alarm signals sharply diminishing after the pathogens or cellular debris have been eliminated and tissue homeostasis restored. Many “stop signals” at appropriate checkpoints prevent further leukocyte infiltration into tissues if they are no longer needed (Serhan et al., 2007). If the balance between inflammation and resolution becomes dysregulated, excess macrophage responses will lead to chronic inflammation, and resultant disease states, which include atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), asthma (Nathan, 2002), and cancer (Grivennikov et al., 2010). Therefore, understanding the regulation of inflammation and its resolution could help in the development of new therapeutic approaches for inflammatory disease management.

Macrophages are optimally activated by a combination of two macromolecular signals in their environment: antigen recognition by PRPs and IFN-γ (Mosser, 2003; O’Shea and Murray, 2008) and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. These pro-inflammatory cytokines are important pyrogens capable of inducing the formation of the fever response and elevation of body temperature through complex neurological and behavioral changes (Kluger, 1991a,b; Cooper et al., 1994; Leon et al., 1997; Romanovsky et al., 1998, 2005). Fever is a highly conserved phenomenon in evolution (Kluger, 1979a, 1986; Mackowiak, 1981; Hasday et al., 2000). Although numerous human and animal studies reveal a positive correlation between the febrile response and a better survival rate, the mechanism by which increased core temperature improves host defense is still not clear. In addition, new studies suggest additional levels of complex interaction between macrophage function and body temperature. Nguyen et al. (2011) have shown that exposure to a cold environment induces alternative activation of adipose tissue macrophages. Thus, while it is likely that their function is responsive to thermal signals, the specific mechanisms by which macrophages sense and respond to temperature change in a way that specifically regulates their function has not been clarified.

To investigate the effect of febrile temperatures on macrophage activity, researchers often simply increase temperature in cell cultures, or elevate body temperature by external heat application in murine models. While these procedures do not reproduce critical features of actual fevers, several studies reveal both positive (Jiang et al., 2000b; Ostberg et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2012) and negative (Ensor et al., 1994; Fairchild et al., 2000; Hagiwara et al., 2007) effects on macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Both positive and negative effects of hyperthermia have been correlated with an induction of heat shock proteins (HSPs). The overall aim of this brief review is to present previous studies that have studied the impact of hyperthermia and HSPs on macrophage functions and to summarize available information regarding the underlying molecular mechanisms which may mediate this complex interaction of thermal signals.

FEVER-RANGE TEMPERATURES CAN ENHANCE MACROPHAGE PRO-INFLAMMATORY CYTOKINE PRODUCTION

Inducing hyperthermia has been used to study the role of febrile temperatures on the host defense system (Hasday et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2000a). It was shown that increasing core body temperature has a protective role in the outcome of infection; the improved survival seen was determined not to be simply due to thermal suppression of bacterial growth. Data published by our laboratory (Ostberg et al., 2000) as well as by others (Jiang et al., 1999b) shows that mild, systemic heating at a target temperature of 39.5°C significantly enhances the concentration of TNF-α (3-fold increase in sera; 2.5-fold increase in liver) and IL-6 (4-fold increase in sera; 2.6-fold increase in spleen, 3.4-fold in lung, and 15-fold in liver) in the blood and tissues of BALB/c mice challenged with bacteria endotoxin (LPS). In addition, Jiang et al. (1999a) identified hepatic Kupffer cells as the predominant source of excess TNF-α secretion while multiple organs including lung, spleen, and liver could produce excess IL-6 in the warmer animals. These temperature-induced changes in cytokine expression are associated with an induction of HSP72 in the liver.

Our laboratory has recently observed that mild elevation of body temperature not only significantly enhances subsequent LPS-induced release of TNF-α (3-fold increase), but also reprograms macrophages, resulting in sustained subsequent responsiveness to LPS, i.e., this treatment reduces “endotoxin tolerance” in vitro and in vivo (Lee et al., 2012). Heat treatment results in an increase in LPS-induced downstream signaling including enhanced phosphorylation of IκB kinase (IKK) and IκB, NF-κB nuclear translocation and binding to the TNF-α promoter in macrophages upon secondary stimulation. The induction of HSP70 is important for mediation of thermal effects on macrophage function (Lee et al., 2012). Our in vitro experiments also show that the production of nitric oxide (NO) and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) by peritoneal macrophages is increased by exposure to febrile temperature together with LPS and IFN-γ stimulation. This result is correlated with the presence of HSP70 in the heat-treated macrophages (Pritchard et al., 2005). Collectively, these data suggest that fever-range hyperthermia can enhance macrophage cytokine expression and HSP70 expression, which in turn may help to improve host defense in response to infection.

FEVER-RANGE TEMPERATURES CAN ALSO SUPPRESS MACROPHAGE PRO-INFLAMMATORY CYTOKINE PRODUCTION

In contrast to the research summarized above, other studies using the macrophage cell lines RAW264.7 or human monocyte-derived macrophages have shown that hyperthermia has anti-inflammatory effects and suppresses activated macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (TNF-α, reduced by 50–98%; IL-6, reduced by 83–87%; and IL-1β, reduced by 50–94%; Ensor et al., 1994; Fairchild et al., 2000; Hagiwara et al., 2007). This inhibition is linked to a marked reduction in cytokine gene transcription and mRNA stability (Ensor et al., 1995). In addition, this thermally suppressed cytokine production is mediated by the binding of heat shock factor (HSF)-1, a transcriptional repressor, to the heat shock response element in the cytokine promoter region, including IL-1β and TNF-α (Cahill et al., 1996; Singh et al., 2002). Recently, Cooper et al. (2010a,b) have shown that fever-range temperatures selectively reduce LPS-induced recruitment of NF-κB and Sp-1 transcription factors to the TNF-α promoter regions.

Heat-induced suppression may involve high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), an intra-nuclear protein that can be released by activated macrophages, necrotic or damaged cells during inflammation. HMGB1 helps immune cells to recognize damaged tissues and initiates intracellular signaling to activate NF-κB and pro-inflammatory cytokine production (Fiuza et al., 2003). Hyperthermia has been shown to inhibit macrophage HMGB1 secretion following LPS stimulation (Fairchild et al., 2000) and Hagiwara et al. (2007) found that high fever temperature (40°C) enhances HSF-1 and HSP70 expression. These increased levels of HSF-1 and HSP70 may reduce HMGB1 secretion and subsequent NF-κB activation and cytokine production. In general, these data support the concept that febrile temperatures can also have inhibitory effects on macrophage cytokine gene expression, an effect correlated with the activation of HSF-1 or induction of HSP70.

REGULATION OF HEAT SHOCK PROTEINS

Heat shock proteins are evolutionarily conserved proteins that can be induced by stress signals, including environmental stresses (e.g., heat shock), and pathophysiological states (e.g., fever, inflammation, and infection) as well as those induced by normal development stresses (Morimoto, 1993, 1998; Wu, 1995).

Heat shock proteins function as chaperones to assist with protein folding in order to protect cells from protein denaturation or cell death under stress conditions (Fink, 1999; Jaattela, 1999). Although HSPs are considered to be intracellular proteins, they can be mobilized to the plasma membrane or released into the extracellular environment and have immunomodulatory functions (Johnson and Fleshner, 2006). HSPs (e.g., HSP60, HSP70, HSP90, gp96, etc.) can be released from various cells through either a passive (during cell injury) or an active (translocation to the plasma membrane and then secretion) pathway. Previous studies have shown that HSP70 is released into the extracellular environment in a membrane-associated form after heat stress (Multhoff, 2007; Vega et al., 2008). HSPs are known to have both positive and negative effects in regulating macrophage function and this may depend on the cellular location of these HSPs. It is proposed that extracellular HSPs might serve as a danger signal to stimulate the immune response, whereas intracellular HSPs could serve as a negative regulator to control the inflammation (Schmitt et al., 2007).

PRO-INFLAMMATORY ROLE OF HEAT SHOCK PROTEINS ON MACROPHAGE FUNCTION

Previous studies have shown that extracellular HSPs exert immunostimulatory effects (Johnson and Fleshner, 2006). Wang et al. (2006) have shown that extracellular HSP70 binds to the lipid raft microdomain on the plasma membrane of macrophages and enhances their phagocytic ability. This HSP70-mediated phagocytosis enhances the processing and presentation of internalized antigens to CD4 T cells. Furthermore, extracellular HSPs can robustly stimulate the release of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12, NO, as well as chemokines by monocytes/macrophages (Lehner et al., 2000; Asea et al., 2002; Panjwani et al., 2002; Vega et al., 2008). This effect is mediated through the CD14/TLR (both TLR2 and TLR4) complexes which lead to the activation of downstream NF-κB and MAPK pathway (Asea et al., 2000; Kol et al., 2000; Vabulas et al., 2002). In addition, HSPs are actively synthesized in peritoneal macrophages in mice which are administrated with LPS (Zhang et al., 1994). HSP70 and HSP90 have been shown to be involved in the innate recognition of bacterial products. These HSPs are able to bind LPS and form a cluster with TLR4–MD2 within lipid raft to deliver LPS to the complex. Following stimulation, these HSPs further assist the trafficking and targeting of this complex to the Golgi apparatus (Triantafilou et al., 2001; Triantafilou and Triantafilou, 2004). These results indicate that elevation of extracellular HSPs may serve as endogenous danger signals to alert the host defense system through their cytokine-like function.

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY ROLE OF HEAT SHOCK PROTEINS ON MACROPHAGE CYTOKINE EXPRESSION

On the other hand, intracellular HSPs have been shown to have anti-inflammatory roles in suppressing macrophage cytokine production. Intracellular HSPs are involved in protecting the organism from a variety of insults by directly interfering with cell death pathway and suppressing the expression of inflammatory genes (Yenari et al., 2005). The protect roles of stress-inducible intracellular HSPs (such as HSP72) in lethal sepsis and infection are well known. Induction of HSP70 in vitro by heat shock response or through overexpression can reduce mortality in experimental models of septic shock and endotoxemia as well as down-regulate inflammatory gene expression (Snyder et al., 1992; Hotchkiss et al., 1993; Villar et al., 1994; Van Molle et al., 2002; Shi et al., 2006). It has been shown that intracellular HSP70 can interact with IKK, prevent IκB phosphorylation, and NF-κB activation (Ran et al., 2004). In addition, HSP70 is actively synthesized in macrophages after exposure to endotoxin. Intracellular HSP70 inhibits LPS-induced NF-κB activation by binding with TRAF6, the important adaptor protein downstream of TLR4 and preventing its ubiquitination (Chen et al., 2006). These results suggest that intracellular HSP70 may act as a suppressor to interfere NF-κB signaling and downstream inflammatory cytokine production. Furthermore, HSP72 has been shown to inhibit LPS- and TNF-α-induced HMGB1 release and subsequent pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages (Tang et al., 2007).

On the other hand, there is only one study by Bouchama et al. (2000) showing that hyperthermia (using target temperature 39, 41, and 43°C) inhibits LPS-stimulated IL-10 production by mononuclear cells isolated from healthy donor as compared to cells maintained at 43°C. In addition, by over-expressing HSP70 in human monocyte-derived macrophages, Ding et al. (2001) found that LPS-induced IL-10 production was significantly inhibited. In our unpublished data, we tried to address whether fever-range temperature affects macrophage IL-10 production at different activation stages. However, we found that temperature did not have any effect on IL-10 expression by either naïve macrophages or previously activated macrophages. Taken together, these studies suggest that intracellular HSPs may exert negative regulatory effects to dampen the inflammatory response in order to prevent tissue damage.

HEAT SHOCK PROTEINS AND INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS

There is some evidence that HSPs may play a role as immunological targets in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as RA (van Eden et al., 2005) and atherosclerosis (Xu, 2002). Increased HSP60 and HSP70 expression have been identified in the synovial tissues from animals with experimental induced arthritis and patients with RA (de Graeff-Meeder et al., 1990; Boog et al., 1992; Martin et al., 2003). Importantly, arthritis disease severity depends on the ability of human HSP60 and HSP70 to induce IL-10 production by monocytes/macrophages and fibroblast-like synoviocytes (MacHt et al., 2000; Luo et al., 2008). The production of IL-10 is negatively correlated with arthritis progression and joint destruction (Isomaki et al., 1996; Tanaka et al., 1996). Several clinical trials in RA patients using immunotherapies involving HSPs have shown to promote anti-inflammatory cytokine production and ameliorate disease severity, indicating that HSPs have immunoregulatory potential (Vischer, 1990; Rosenthal et al., 1991; Prakken et al., 2004).

On the other hand, HSP60 and HSP70 are also found in atherosclerotic lesions (Berberian et al., 1990; Kleindienst et al., 1993; Johnson et al., 1995). During the past decade, it has been noted that infections (e.g., chlamydiae infection) might contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis to directly stimulate cells of the arterial wall and/or other tissues to express high levels of HSPs (Kiechl et al., 2001). Chlamydial HSP60 (cHSP60) colocalizes with human HSP60 within macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions (Kol et al., 1998). Both chlamydial and human HSPs stimulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules by macrophages through TLR4/MD2-dependent pathway (Bulut et al., 2002). Because of the high homology between chlamydial and human HSPs, it is possible that cross-reactions of antibodies and T cells against HSPs between microbes and humans contribute to the development of atherosclerosis (Xu, 2002). Taken together, a better understanding of the role of HSPs in the inflammatory process may lead to the development of new therapies to modify aberrant immune responses.

DOES THE MATURATION STATE OF MACROPHAGES INFLUENCE THE EFFECT OF HEAT AND HEAT SHOCK PROTEINS?

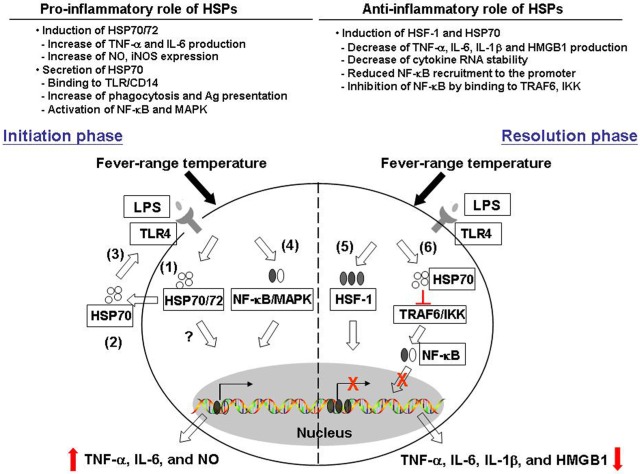

In this paper, we described previous studies revealing contrasting effects of febrile temperatures and HSPs on macrophage functions. Mild hyperthermia enhances macrophage TNF-α IL-6 as well as NO production in a HSP70/72-dependent mechanism. On the other hand, mild hyperthermia suppresses macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine production and this may involve an increase in HSF-1 and HSP70 expression. Thermally induced HSF-1 and HSP70 also play a role in blocking the transcription factors NF-κB and Sp-1 recruitment to the cytokine promoter and subsequent cytokine secretion (see Figure 1, for possible pathways by which thermal stress may result in both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects).

FIGURE 1.

Pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of heat and heat shock proteins. Fever range temperature exerts both positive and negative effects on macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine production. We proposed that these opposing effects may depend on the activation stage of macrophages as well as the cellular location of heat shock proteins. First, in the initiation phase of macrophage activation, fever range temperature enhances the production of LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and NO. (1) This thermally enhanced cytokine production is associated with an induction of HSP70/72 in these cells. (2) HSP70 can then be released into the extracellular environment, and (3) exerts its cytokine effect through the CD14/TLR pathway. (4) This leads to the activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathway and subsequent cytokine gene transcription. On the other hand, fever-range temperature can also suppress LPS-induced TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β production and HMGB-1 release. (5) This is due to thermally induced HSF-1 binding directly to the heat shock response element in the cytokine promoter region and functions as a transcriptional repressor. (6) In addition, LPS and heat treatment can also induce HSP70 expression. HSP70 then binds to TRAF6 or IKK and inhibits subsequent NF-κB activation and cytokine production.

One possible explanation for these opposing results is that the resultant effect of heat is determined by the specific activation state of macrophages used for the analysis. For example, enhancing effects of heating were observed using cells freshly isolated from mice early after LPS injection (Jiang et al., 1999a,b; Lee et al., 2012). These cells express a naïve phenotype. On the other hand, the suppressing effects were obtained using RAW264.7 cells which express an activated phenotype (Ensor et al., 1994; Fairchild et al., 2000; Hagiwara et al., 2007). Therefore, we propose that in cells associated with the early activation stage of inflammation, febrile temperature may stimulate macrophage cytokine production, which helps to eliminate invading pathogens, whereas if heat is applied to cells associated with the resolution phase, a suppression of macrophage cytokine production occurs to prevent further tissue damage. This idea, if correct, would suggest that one of the functions of natural fever may be to help resolve inflammation. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is no previous study addressing the role of heat/HSP on alternatively activated macrophage functions. This indicates that more research is needed to identify the mechanistic basis of the contrasting effects of hyperthermia on macrophage function.

CONCLUSION

The host inflammatory response to injury or infection is clearly a complex process. Pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted by activated macrophages are essential for successful host defense. However, uncontrolled inflammatory cytokine production will also cause tissue damage. The febrile response is a well recognized component of inflammation and has been shown to provide a beneficial effect for the host but whether the thermal element of fever has a direct role in regulating macrophage function is still not clear. By using hyperthermia, many studies have reported that febrile temperatures can regulate macrophage pro-inflammatory cytokine production both in vitro and in vivo. These effects are associated with the induction of HSP. However, these effects can be either positive or negative and much more research is needed to understand how these two contrasting effects coincide.

In addition, we also summarized research which shows both the pro- and anti-inflammatory roles of HSPs. Extracellular HSPs might serve as a danger signal to stimulate the immune response, whereas intracellular HSPs could serve as a negative regulator to control the inflammation. Studies of the roles and mechanisms of heat as well as HSPs in inflammatory disorders could provide more information for therapeutic strategies targeting the molecular levels.

Finally, it is important to remember that most of the research on the role of elevated temperature on macrophage function does not actually use a physiological fever (i.e., induced by endoxin or other pyrogens), but instead, simply forces the elevation of body temperature using external heating. While some studies described above do include the addition of LPS, or use heat in the presence of infectious antigens, fever involves many biochemical, neurological, and vascular changes not seen in conditions of forced hyperthermia (Kluger, 1979b, 1991a; Gordon, 1993; Romanovsky et al., 1998, 2005). Therefore, it is possible that the elevated temperature associated with actual fever may have additional and more complex regulatory effects on macrophage function.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lingwen Zhong, Thomas A. Mace, Nicholas Leigh, Bonnie Hylander and Maegan Capitano for their helpful discussions of the data summarized here. We also acknowledge grant support from NIH P01 CA094045, R01 CA135368-01A1, R01 CA071599-11, and the Roswell Park Cancer Institute Core Grant CA016056.

REFERENCES

- Asea A., Kraeft S. K., Kurt-Jones E. A., Stevenson M. A., Chen L. B., Finberg R. W., Koo G. C., Calderwood S. K. (2000). HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat. Med. 6 435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A., Rehli M., Kabingu E., Boch J. A., Bare O., Auron P. E., Stevenson M. A., Calderwood S. K. (2002). Novel signal transduction pathway utilized by extracellular HSP70: role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4. J. Biol. Chem. 277 15028–15034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberian P. A., Myers W., Tytell M., Challa V., Bond M. G. (1990). Immunohistochemical localization of heat shock protein-70 in normal-appearing and atherosclerotic specimens of human arteries. Am. J. Pathol. 136 71–80 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boog C. J., de Graeff-Meeder E. R., Lucassen M. A., Van Der Zee R., Voorhorst-Ogink M. M., Van Kooten P. J., Geuze H. J., van Eden W. (1992). Two monoclonal antibodies generated against human hsp60 show reactivity with synovial membranes of patients with juvenile chronic arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 175 1805–1810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchama A., Hammami M. M., Al Shail E., De Vol E. (2000). Differential effects of in vitro and in vivo hyperthermia on the production of interleukin-10. Intensive Care Med. 26 1646–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulut Y., Faure E., Thomas L., Karahashi H., Michelsen K. S., Equils O., Morrison S. G., Morrison R. P., Arditi M. (2002). Chlamydial heat shock protein 60 activates macrophages and endothelial cells through Toll-like receptor 4 and MD2 in a MyD88-dependent pathway. J. Immunol. 168 1435–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill C. M., Waterman W. R., Xie Y., Auron P. E., Calderwood S. K. (1996). Transcriptional repression of the prointerleukin 1beta gene by heat shock factor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 271 24874–24879 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Wu Y., Zhang Y., Jin L., Luo L., Xue B., Lu C., Zhang X., Yin Z. (2006). Hsp70 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation by interacting with TRAF6 and inhibiting its ubiquitination. FEBS Lett. 580 3145–3152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A. L., Brouwer S., Turnbull A. V., Luheshi G. N., Hopkins S. J., Kunkel S. L., Rothwell N. J. (1994). Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and fever after peripheral inflammation in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 267 R1431–R1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Z. A., Ghosh A., Gupta A., Maity T., Benjamin I. J., Vogel S. N., Hasday J. D., Singh I. S. (2010a). Febrile-range temperature modifies cytokine gene expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages by differentially modifying NF-{kappa}B recruitment to cytokine gene promoters. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 298 C171–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Z. A., Singh I. S., Hasday J. D. (2010b). Febrile range temperature represses TNF-alpha gene expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages by selectively blocking recruitment of Sp1 to the TNF-alpha promoter. Cell Stress Chaperones 15 665–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Graeff-Meeder E. R., Voorhorst M., van Eden W., Schuurman H. J., Huber J., Barkley D., Maini R. N., Kuis W., Rijkers G. T., Zegers B. J. (1990). Antibodies to the mycobacterial 65-kd heat-shock protein are reactive with synovial tissue of adjuvant arthritic rats and patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Am. J. Pathol. 137 1013–1017 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depraetere V. (2000). “Eat me” signals of apoptotic bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2 E104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X. Z., Fernandez-Prada C. M., Bhattacharjee A. K., Hoover D. L. (2001). Over-expression of hsp-70 inhibits bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced production of cytokines in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Cytokine 16 210–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensor J. E., Crawford E. K., Hasday J. D. (1995). Warming macrophages to febrile range destabilizes tumor necrosis factor-alpha mRNA without inducing heat shock. Am. J. Physiol. 269 C1140–C1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensor J. E., Wiener S. M., Mccrea K. A., Viscardi R. M., Crawford E. K., Hasday J. D. (1994). Differential effects of hyperthermia on macrophage interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression. Am. J. Physiol. 266 C967–C974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild K. D., Viscardi R. M., Hester L., Singh I. S., Hasday J. D. (2000). Effects of hypothermia and hyperthermia on cytokine production by cultured human mononuclear phagocytes from adults and newborns. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 20 1049–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink A. L. (1999). Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol. Rev. 79 425–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiuza C., Bustin M., Talwar S., Tropea M., Gerstenberger E., Shelhamer J. H., Suffredini A. F. (2003). Inflammation-promoting activity of HMGB1 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood 101 2652–2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara N., Kobayashi K. (2005). Macrophages in inflammation. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy 4 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C. J., (ed.) (1993). “Fever,” in Temperature Regulation in Laboratory Rodents (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ), 41–45 [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov S. I., Greten F. R., Karin M. (2010). Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140 883–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara S., Iwasaka H., Matsumoto S., Noguchi T. (2007). Changes in cell culture temperature alter release of inflammatory mediators in murine macrophagic RAW264.7 cells. Inflamm. Res. 56 297–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasday J. D., Fairchild K. D., Shanholtz C. (2000). The role of fever in the infected host. Microbes Infect. 2 1891–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss R., Nunnally I., Lindquist S., Taulien J., Perdrizet G., Karl I. (1993). Hyperthermia protects mice against the lethal effects of endotoxin. Am. J. Physiol. 265 R1447–R1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isomaki P., Luukkainen R., Saario R., Toivanen P., Punnonen J. (1996). Interleukin-10 functions as an antiinflammatory cytokine in rheumatoid synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 39 386–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaattela M. (1999). Heat shock proteins as cellular lifeguards. Ann. Med. 31 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Akashi S., Miyake K., Petty H. R. (2000a). Lipopolysaccharide induces physical proximity between CD14 and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) prior to nuclear translocation of NF-kappa B. J. Immunol. 165 3541–3544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Cross A. S., Singh I. S., Chen T. T., Viscardi R. M., Hasday J. D. (2000b). Febrile core temperature is essential for optimal host defense in bacterial peritonitis. Infect. Immun. 68 1265–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Detolla L., Singh I. S., Gatdula L., Fitzgerald B., Van Rooijen N., Cross A. S., Hasday J. D. (1999a). Exposure to febrile temperature upregulates expression of pyrogenic cytokines in endotoxin-challenged mice. Am. J. Physiol. 276 R1653–R1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Detolla L., Van Rooijen N., Singh I. S., Fitzgerald B., Lipsky M. M., Kane A. S., Cross A. S., Hasday J. D. (1999b). Febrile-range temperature modifies early systemic tumor necrosis factor alpha expression in mice challenged with bacterial endotoxin. Infect. Immun. 67 1539–1546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. D., Berberian P. A., Tytell M., Bond M. G. (1995). Differential distribution of 70-kD heat shock protein in atherosclerosis. Its potential role in arterial SMC survival. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. D., Fleshner M. (2006). Releasing signals, secretory pathways, and immune function of endogenous extracellular heat shock protein 72. J. Leukoc. Biol. 79 425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiechl S., Egger G., Mayr M., Wiedermann C. J., Bonora E., Oberhollenzer F., Muggeo M., Xu Q., Wick G., Poewe W., Willeit J. (2001). Chronic infections and the risk of carotid atherosclerosis: prospective results from a large population study. Circulation 103 1064–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst R., Xu Q., Willeit J., Waldenberger F. R., Weimann S., Wick G. (1993). Immunology of atherosclerosis. Demonstration of heat shock protein 60 expression and T lymphocytes bearing alpha/beta or gamma/delta receptor in human atherosclerotic lesions. Am. J. Pathol. 142 1927–1937 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger M. J. (1979a). Fever. Its biology, Evolution, and Function. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- Kluger M. J. (1979b). Temperature regulation, fever, and disease. Int. Rev. Physiol. 20 209–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger M. J. (1986). Is fever beneficial? Yale J. Biol. Med. 59 89–95 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger M. J. (1991a). “The adaptive value of fever,” ed.Mackowiak P. A. (New York: Raven Press; ), 105–124 [Google Scholar]

- Kluger M. J. (1991b). Fever: role of pyrogens and cryogens. Physiol. Rev. 71 93–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kol A., Lichtman A. H., Finberg R. W., Libby P., Kurt-Jones E. A. (2000). Cutting edge: heat shock protein (HSP) 60 activates the innate immune response: CD14 is an essential receptor for HSP60 activation of mononuclear cells. J. Immunol. 164 13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kol A., Sukhova G. K., Lichtman A. H., Libby P. (1998). Chlamydial heat shock protein 60 localizes in human atheroma and regulates macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha and matrix metalloproteinase expression. Circulation 98 300–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.-T., Zhong L., Mace T. A., Repasky E. A. (2012). Elevation in body temperature to Fever range enhances and prolongs subsequent responsiveness of macrophages to endotoxin challenge. PLoS ONE 7 e30077 10.1371/journal.pone.0030077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehner T., Bergmeier L. A., Wang Y., Tao L., Sing M., Spallek R., Van Der Zee R. (2000). Heat shock proteins generate beta-chemokines which function as innate adjuvants enhancing adaptive immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 30 594–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon L. R., Kozak W., Peschon J., Glaccum M., Kluger M. J. (1997). Altered acute phase responses to inflammation in IL-1 and TNF receptor knockout mice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 813 244–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X., Zuo X., Zhang B., Song L., Wei X., Zhou Y., Xiao X. (2008). Release of heat shock protein 70 and the effects of extracellular heat shock protein 70 on the production of IL-10 in fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Cell Stress Chaperones 13 365–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacHt L. M., Elson C. J., Kirwan J. R., Gaston J. S., Lamont A. G., Thompson J. M., Thompson S. J. (2000). Relationship between disease severity and responses by blood mononuclear cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis to human heat-shock protein 60. Immunology 99 208–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackowiak P. A. (1981). Direct effects of hyperthermia on pathogenic microorganisms: teleologic implications with regard to fever. Rev. Infect. Dis. 3 508–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. A., Carsons S. E., Kowalewski R., Bernstein D., Valentino M., Santiago-Schwarz F. (2003). Aberrant extracellular and dendritic cell (DC) surface expression of heat shock protein (hsp)70 in the rheumatoid joint: possible mechanisms of hsp/DC-mediated cross-priming. J. Immunol. 171 5736–5742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto R. I. (1993). Cells in stress: transcriptional activation of heat shock genes. Science 259 1409–1410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto R. I. (1998). Regulation of the heat shock transcriptional response: cross talk between a family of heat shock factors, molecular chaperones, and negative regulators. Genes Dev. 12 3788–3796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosser D. M. (2003). The many faces of macrophage activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73 209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhoff G. (2007). Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70): membrane location, export and immunological relevance. Methods 43 229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. (2002). Points of control in inflammation. Nature 420 846–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K. D., Qiu Y., Cui X., Goh Y. P., Mwangi J., David T., Mukundan L., Brombacher F., Locksley R. M., Chawla A. (2011). Alternatively activated macrophages produce catecholamines to sustain adaptive thermogenesis. Nature 480 104–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea J. J., Murray P. J. (2008). Cytokine signaling modules in inflammatory responses. Immunity 28 477–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostberg J. R., Taylor S. L., Baumann H., Repasky E. A. (2000). Regulatory effects of fever-range whole-body hyperthermia on the LPS-induced acute inflammatory response. J. Leukoc. Biol. 68 815–820 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjwani N. N., Popova L., Srivastava P. K. (2002). Heat shock proteins gp96 and hsp70 activate the release of nitric oxide by APCs. J. Immunol. 168 2997–3003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakken B. J., Samodal R., Le T. D., Giannoni F., Yung G. P., Scavulli J., Amox D., Roord S., De Kleer I., Bonnin D., Lanza P., Berry C., Massa M., Billetta R., Albani S. (2004). Epitope-specific immunotherapy induces immune deviation of proinflammatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 4228–4233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard M. T., Li Z., Repasky E. A. (2005). Nitric oxide production is regulated by fever-range thermal stimulation of murine macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 78 630–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran R., Lu A., Zhang L., Tang Y., Zhu H., Xu H., Feng Y., Han C., Zhou G., Rigby A. C., Sharp F. R. (2004). Hsp70 promotes TNF-mediated apoptosis by binding IKK gamma and impairing NF-kappa B survival signaling. Genes Dev. 18 1466–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanovsky A. A., Almeida M. C., Aronoff D. M., Ivanov A. I., Konsman J. P., Steiner A. A., Turek V. F. (2005). Fever and hypothermia in systemic inflammation: recent discoveries and revisions. Front. Biosci. 10 2193–2216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanovsky A. A., Kulchitsky V. A., Simons C. T., Sugimoto N. (1998). Methodology of fever research: why are polyphasic fevers often thought to be biphasic? Am. J. Physiol. 275 R332–R338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M., Bahous I., Ambrosini G. (1991). Longterm treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with OM-8980. A retrospective study. J. Rheumatol. 18 1790–1793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt E., Gehrmann M., Brunet M., Multhoff G., Garrido C. (2007). Intracellular and extracellular functions of heat shock proteins: repercussions in cancer therapy. J. Leukoc. Biol. 81 15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan C. N., Brain S. D., Buckley C. D., Gilroy D. W., Haslett C., O’Neill L. A., Perretti M., Rossi A. G., Wallace J. L. (2007). Resolution of inflammation: state of the art, definitions and terms. FASEB J. 21 325–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Tu Z., Tang D., Zhang H., Liu M., Wang K., Calderwood S. K., Xiao X. (2006). The inhibition of LPS-induced production of inflammatory cytokines by HSP70 involves inactivation of the NF-kappaB pathway but not the MAPK pathways. Shock 26 277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh I. S., He J. R., Calderwood S., Hasday J. D. (2002). A high affinity HSF-1 binding site in the 5′-untranslated region of the murine tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene is a transcriptional repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 277 4981–4988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder Y. M., Guthrie L., Evans G. F., Zuckerman S. H. (1992). Transcriptional inhibition of endotoxin-induced monokine synthesis following heat shock in murine peritoneal macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol. 51 181–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Otsuka T., Hotokebuchi T., Miyahara H., Nakashima H., Kuga S., Nemoto Y., Niiro H., Niho Y. (1996). Effect of IL-10 on collagen-induced arthritis in mice. Inflamm. Res. 45 283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D., Kang R., Xiao W., Wang H., Calderwood S. K., Xiao X. (2007). The anti-inflammatory effects of heat shock protein 72 involve inhibition of high-mobility-group box 1 release and proinflammatory function in macrophages. J. Immunol. 179 1236–1244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafilou K., Triantafilou M., Dedrick R. L. (2001). A CD14-independent LPS receptor cluster. Nat. Immunol. 2 338–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triantafilou M., Triantafilou K. (2004). Heat-shock protein 70 and heat-shock protein 90 associate with Toll-like receptor 4 in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32 636–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabulas R. M., Ahmad-Nejad P., Ghose S., Kirschning C. J., Issels R. D., Wagner H. (2002). HSP70 as endogenous stimulus of the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor signal pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 277 15107–15112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eden W., Van Der Zee R., Prakken B. (2005). Heat-shock proteins induce T-cell regulation of chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5 318–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Molle W., Wielockx B., Mahieu T., Takada M., Taniguchi T., Sekikawa K., Libert C. (2002). HSP70 protects against TNF-induced lethal inflammatory shock. Immunity 16 685–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega V. L., Rodriguez-Silva M., Frey T., Gehrmann M., Diaz J. C., Steinem C., Multhoff G., Arispe N., De Maio A. (2008). Hsp70 translocates into the plasma membrane after stress and is released into the extracellular environment in a membrane-associated form that activates macrophages. J. Immunol. 180 4299–4307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J., Ribeiro S. P., Mullen J. B., Kuliszewski M., Post M., Slutsky A. S. (1994). Induction of the heat shock response reduces mortality rate and organ damage in a sepsis-induced acute lung injury model. Crit. Care Med. 22 914–921 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vischer T. L. (1990). Follow-up with OM-8980 after a double-blind study of OM-8980 and auranofin in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 9 356–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Kovalchin J. T., Muhlenkamp P., Chandawarkar R. Y. (2006). Exogenous heat shock protein 70 binds macrophage lipid raft microdomain and stimulates phagocytosis, processing, and MHC-II presentation of antigens. Blood 107 1636–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. (1995). Heat shock transcription factors: structure and regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 11 441–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q. (2002). Role of heat shock proteins in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22 1547–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yenari M. A., Liu J., Zheng Z., Vexler Z. S., Lee J. E., Giffard R. G. (2005). Antiapoptotic and anti-inflammatory mechanisms of heat-shock protein protection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1053 74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. H., Takahashi K., Jiang G. Z., Zhang X. M., Kawai M., Fukada M., Yokochi T. (1994). In vivo production of heat shock protein in mouse peritoneal macrophages by administration of lipopolysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 62 4140–4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]