Case Report

A 78-year-old Chinese man presented with weight loss, diarrhea, and an altered sense of taste for the past 6 months. The patient had a history of prostate and cecal cancers, for which he had undergone a right hemicolectomy in 1988. At that time, 2 of 18 lymph nodes were positive. Since then, the patient has been undergoing periodic surveillance colonoscopies, and hyperplastic polyps have occasionally been identified and removed. In 2000 and 2003, his colonoscopies had normal findings. In 2007, a colonoscopy revealed a normal anastomosis and a large inflammatory polyp 60 cm within the descending colon.

On physical examination, the patient did not appear cachectic, and his abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended. He had hemoccult-positive stool. Of note, he had hyperpigmentation of both hands, alopecia, and atrophic nail changes (Figure 1). His carcinoembryonic antigen level was 3.3 ng/mL, his hemoglobin level was 14.4 g/dL, and his albumin level was 3.4 g/dL.

Figure 1.

Onychodystrophy with characteristic fingernail changes.

The patient underwent an upper endoscopy and colonoscopy to further investigate his condition. The upper endoscopy revealed a carpet of predominantly sessile polyps coating the gastric body, antrum, and duodenum (Figure 2). Multiple new polyps were found in the patient's remaining colon and rectum (Figures 3 and 4). Pathologic review of all specimens demonstrated multiple benign, juvenile-like polyps with cystically dilated and distorted hyperplastic glands; marked stromal edema; and a mixture of inflammatory cells, including eosinophils. In addition, there was a small adenoma in the antrum, a small tubular adenoma in the rectum, and a microscopic focus of moderate-to-severe dysplasia in the duodenum. Results of a gastric CLO test were negative, and no Helicobacter organisms were seen in gastric or duodenal specimens.

Figure 2.

A diffuse carpet of polyps lining the stomach, with a similar pattern of confluent polyp formation extending into the duodenum.

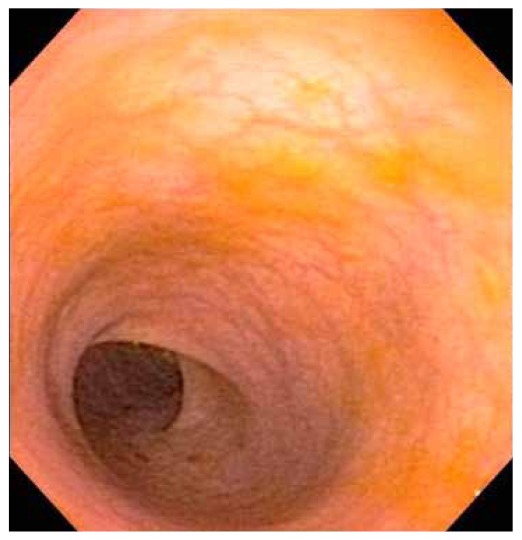

Figure 3.

Normal-appearing descending colon seen during the patient's routine surveillance colonoscopy in 2007.

Figure 4.

The portion of the descending colon from Figure 3 seen during a routine surveillance colonoscopy in 2010 with marked interval polyp development. This endoscopic finding extended proximally to the ileocolic anastomosis and terminal ileum.

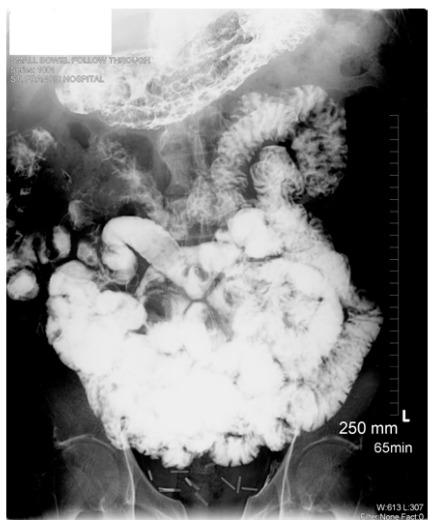

The patient underwent a small bowel follow-through, which revealed multiple jejunal and ileal polyps (Figure 5). A computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast had unremarkable findings. The patient's prostate-specific antigen level was 3.3 ng/mL, his erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 2 mm/hr, and his serum gastrin level was 406 pg/mL; in addition, testing for antinuclear antibody was negative. Genetic testing of peripheral blood revealed no adenomatous polyposis coli or MutY human homologue germline mutations. Subsequent upper enteroscopy, colonoscopy, and biopsies of duodenal, jejunal, and colonic polyps were performed after the patient was placed on proton pump inhibitor therapy. The findings of these procedures were similar to those from the first set of procedures, although the atypia in the duodenal polyp specimens had regressed.

Figure 5.

An upper gastrointestinal barium study with small bowel follow-through demonstrating multiple polyps in the stomach, duodenum, and small bowel.

Discussion

A number of syndromes exhibit polyposis of the gastrointestinal tract. Our patient is an unusual case, as he had both upper and lower gastrointestinal polyposis with anatomic distributions and unique histopathologies that were consistent with the rare Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CSS).

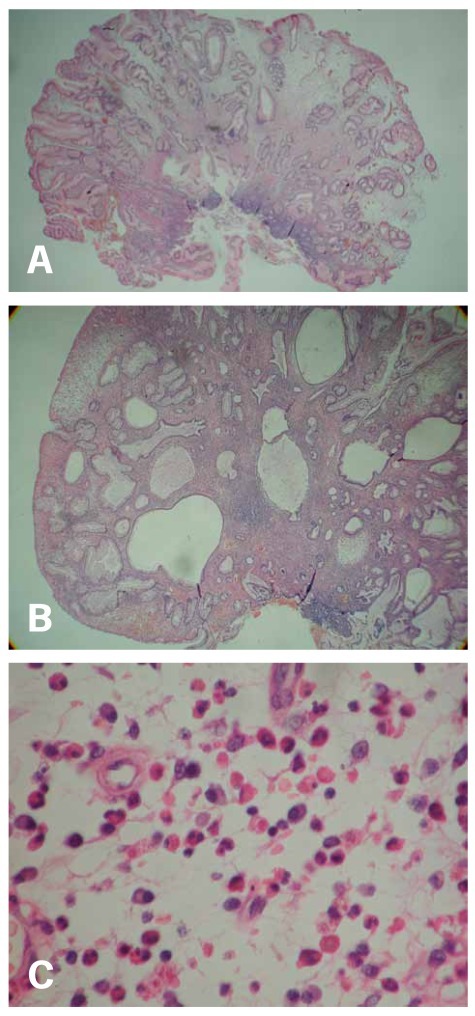

Our patient had widespread non-neoplastic polyposis throughout the stomach, small intestine, and colon. The pathology of these polyps was very similar to that of juvenile-type polyps, but it was unique in that the stroma showed striking edema and eosinophilic inflammation. The diagnosis of this patient (as with any case of CCS) involves a clinicopathologic correlation of endoscopic, pathologic, and cutaneous features.1,2 Patients may have dysgeusia and diarrhea and may be positive for antinuclear antiboda case of cronkhite-canada syndromeies.1–3 Approximately 400 cases of CCS have been reported worldwide, mainly from Japan.4 The characteristic pathology of CCS polyps, which was seen in our patient, consists of cystic gland dilation and elongation with variable hyperplasia, stromal edema, and eosinophilic inflammation (Figure 6).2,3,5 Adenomatous polyps may occasionally develop. CCS patients also have an increased risk of gastric and predominantly left-sided colon cancers.5–10

Figure 6.

Histology of gastrointestinal polyps. Both the gastric (A) and colonic (B) polyps are sessile and show hyperplastic, cystically dilated glands with edema and eosinophilic inflammation of the lamina propria (C). These composite features are most consistent with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. (Hematoxylin and eosin stains; 40x magnification for A, 80x magnification for B, and 800x magnification for C.)

The 5-year mortality rate for CCS has been reported to be 55%. Complications include gastrointestinal bleeding, intussusception, rectal prolapse, portal vein thrombosis, membranous glomerulonephritis, and protein-losing enteropathy.5,6,11,12 Forty-one percent of patients also have adenomas, including serrated adenomas, which are precursor lesions to colorectal cancer; they are associated with a 15% increased risk of cancer development.5,10 The most common sites for malignancy are the sigmoid colon and rectum, although our patient had prior right-sided colon cancer. Gastric cancer has been reported in 32 Japanese patients with CCS. These gastric cancers were usually large in size, well differentiated, and generally limited to the submucosa.8,13

CSS therapies have included corticosteroids for treatment of protein-losing enteropathy, weight loss, and diarrhea; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for suppression of polyps; and proton pump inhibitors for suppression of acid. Our patient was treated with sulindac (150 mg twice daily), pantoprazole sodium (Protonix, Wyeth), and prednisone. He also received endoscopic surveillance.

Other polyposis syndromes involve different segments of the gastrointestinal tract (Table 1). These polyps can be classified as hamartomatous, adenomatous, or hyperplastic in nature. Hamartomas are lesions that result from disorderly proliferation of normally occurring tissue with varying degrees of hyperplasia, inflammation, and fibrosis. CCS is considered to be a hamartomatous polyposis syndrome.14–16 The distribution and pathology of polyps in CCS patients are distinct. CCS is differentiated from other hamartoma-tous polyposis syndromes by its widespread polyp distribution in the stomach, small bowel, and colon. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome involves hamartomatous lesions throughout the gastrointestinal tract, mainly in the jejunum, followed by the colon, and then the stomach. In addition, these patients often have associated extraintestinal manifestations, such as pigmented macules in the skin and mouth. Symptom onset usually occurs prior to 30 years of age.17 Juvenile polyposis syndrome develops before 10 years of age and is characterized by hamartomatous polyps with an inflammatory component; these polyps are usually found in the colon and, to a much lesser degree, in the stomach and small intestine.17,18

Table 1.

Polyposis Colonic Syndromes and Distribution of Polyps in the Gastrointestinal Tract

| Distribution of polyps | ||||||||

| Syndrome | Age of symptom onset | Transmission | Stomach | Small bowel | Colon | Histology | Extraintestinal manifestations | Prognosis |

| Hyperplastic polyposis syndrome | >40 years | Familial clusters | 0% | 0% | 100% | Hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas | None | Colon cancer (mostly right-sided) |

| Cronkhite-Canada syndrome | 50–60 years | Sporadic | 100% | 50% | 100% | Hamartomatous polyps (juvenile type) exhibiting glandular hyperplasia, cystic dilation, mucosal edema, and eosinophilic inflammation | Alopecia, dermal hyperpigmentation, onychodystrophy, diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy, dysgeusia | Cachexia, colon cancer (mostly left-sided) |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | 10–30 years | Autosomal dominant | 25% | 64–96% | 25–35% | Hamartomas in the stomach and small bowel, adenomatous polyps in the colon | Mucocutaneous melanosis (mostly in the lips and buccal mucosa) | Colon, gastric, pancreatic, breast, and/or gynecologic cancers |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis | 15–20 years | Autosomal dominant | 10–30% | 10% | 100% | Adenomas | Hypertrophy of retinal pigment epithelium, brain tumors (Turcot syndrome), epidermoid cysts, mandibular osteomas, desmoids, thyroid tumors (Gardner syndrome) | Colon, duodenal, and/or thyroid cancers |

| Juvenile polyposis syndrome | < 10 years | Autosomal dominant | 14% | <10% | 100% | Hamartomas with an inflammatory component, usually solitary in nature, and commonly found in the rectum. Adenomas and hyperplastic polyps are less common. | Rectal bleeding, protein-losing enteropathy, intussusception | Colon and/or gastric cancers |

| Cowden syndrome | 9–20 years | Autosomal dominant | 20% | 20% | 30% | Hamartomas | Facial trichilemmomas, macrocephaly, mucocutaneous lesions, acral keratoses, thyroid disease, breast disease | Breast, thyroid, reproductive organ, and/or colon cancers |

Adenomatous polyposis syndromes are characterized by inheritance of an abnormal autosomal dominant gene that results in multiple colorectal adenomatous polyps. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) usually involves the colon and rectum and, to a much lesser extent, the stomach and small bowel. In FAP patients, the risk of adenomas progressing to colon cancer approaches 100% by the time these patients are 50 years of age.17

Hyperplastic polyps are often found in the rectum and are considered to be the most common type of nonmalignant colonic polyp. Hyperplastic polyposis syndrome is a specific entity in which hyperplastic polyps are found in abundance throughout the colon in the absence of gastric or small bowel involvement. Diagnostic criteria for hyperplastic polyposis syndrome include: 5 or more hyperplastic polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon, 2 of which are larger than 1 cm; any number of hyperplastic polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon in a patient who has a first-degree relative with hyperplastic polyposis; or, more than 30 hyperplastic polyps throughout the colon.13,19 This syndrome has a male predominance and is more common in patients over 40 years of age. Usually, the polyps are large, flat, and found along haustral folds. Polyps located in the proximal colon are usually sessile, serrated adenomas, which lead to an increased risk of right-sided colon cancer.19,20 CCS polyps have been described and interpreted as hyperplastic in appearance, but they are most appropriately characterized as hamartomatous and are distinct from hyperplastic polyps.

When encountering an unusual number or distribution of polyps during an endoscopy, clinicians can find it helpful to examine the entire gastrointestinal tract for additional involvement and to scrutinize the histopathology of the polyps. Recognition of extraintestinal manifestations also facilitates accurate identification of polyposis syndromes.

Biography

The authors wish to thank Dr. Janis Atkinson and Dr. Margaret Yungbluth, Department of Pathology, St. Francis Hospital, Evanston, Illinois, for their assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cronkhite LW, Jr, Canada WJ. Generalized gastrointestinal polyposis; an unusual syndrome of polyposis, pigmentation, alopecia, and onychotrophia. N Engl J Med. 1955;252:1011–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195506162522401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura M, Kobashikawa K, Tamura J, et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Intern Med. 2009;48:1561–1562. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson RD, Patel R, Hamilton JK, Boland CR. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome presenting as eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2006;19:209–212. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2006.11928163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riegert-Johnson DL, Osborn N, Smyrk T, Boardman LA. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome hamartomatous polyps are infiltrated with IgG4 plasma cells. Digestion. 2007;75:96–97. doi: 10.1159/000102963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calva D, Howe JR. Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:779–817. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarnum S, Jensen H. Diffuse gastrointestinal polyposis with ectodermal changes. A case with severe malabsorption and enteric loss of plasma proteins and electrolytes. Gastroenterology. 1966;50:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kao KT, Patel JK, Pampati V. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a case report and review of literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2009;2009:619378. doi: 10.1155/2009/619378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karasawa H, Miura K, Ishida K, et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated with huge intramucosal gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:113–117. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0506-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yashiro M, Kobayashi H, Kubo N, Nishiguchi Y, Wakasa K, Hirakawa K. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome containing colon cancer serrated adenoma lesions. Digestion. 2004;69:57–62. doi: 10.1159/000076560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egawa T, Kubota T, Otani Y, et al. Surgically treated Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:156–160. doi: 10.1007/pl00011711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, Ruprecht RM, Rajacich GM, Schwabe AD. The Cronhite-Canada syndrome. An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982;61:293–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeuchi Y, Yoshikawa M, Tsukamoto N, et al. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome with colon cancer, portal thrombosis, high titer of antinuclear antibodies, and membranous glomerulonephritis. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:791–795. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burt RW, Jass JR. Hyperplastic polyposis. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. In: Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosai J. Surgical Pathology. 9th ed. Vol 2. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2004. pp. 806–807. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills SE, Carter D, Greenson JK, Oberman HA, Reuter V, Stoler MH, editors. 4th ed. Vol 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology; p. 1453.p. 1555. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar V, Abbas A, Fausto N. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2010. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease; p. 818. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, Dunn DL, Hunter JG, Pollock RE. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005. Schwartz's Principles of Surgery; pp. 1086–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandrasoma P. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999. Gastrointestinal Pathology; pp. 317–318. [Google Scholar]

- 19.East JE, Saunders BP, Jass JR. Sporadic and syndromic hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas of the colon: classification, molecular genetics, natural history, and clinical management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:25–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover DC, Torlakovic G, Nesland JM. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:65–81. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Townsend CM, Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. 18th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2008. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Procedures; pp. 1392–1406. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margulis A. 2nd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1973. Alimentary Tract Roentgenology; p. 1063. [Google Scholar]