Abstract

Osteopontin (OPN) is a matricellular protein with proinflammatory and profibrotic properties. Previous reports demonstrate a role for OPN in wound healing and pulmonary fibrosis. Herein, we determined if OPN levels are increased in a large cohort of systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients and if OPN contributes dermal fibrosis. Plasma OPN levels were increased in SSc patients, including patients with limited and diffuse disease, compared to healthy controls. Immunohistology demonstrated OPN on fibroblast-like and inflammatory cells in SSc skin and lesional skin from mice in the bleomycin-induced dermal fibrosis model. OPN deficient (OPN−/−) mice developed less dermal fibrosis compared to wild-type mice in the bleomycin-induced dermal fibrosis model. Additional in vivo studies demonstrated that lesional skin from OPN−/− mice had fewer Mac-3+ cells, fewer myofibroblasts, decreased TGF-beta (TGFβ) and genes in the TGFβ pathway and decreased numbers of cells expressing phosphorylated SMAD2 (pSMAD) and ERK. In vitro, OPN−/− dermal fibroblasts had decreased migratory capacity but similar phosphorylation of SMAD2 by TGFβ. Finally, TGFβ production by OPN deficient macrophages was reduced compared to wild type. These data demonstrate an important role for OPN in the development of dermal fibrosis and suggest that OPN may be a novel therapeutic target in SSc.

INTRODUCTION

Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis, SSc) is a chronic, multisystem autoimmune disease clinically characterized by progressive fibrosis of the skin and internal organs (Charles et al., 2006). SSc exhibits three cardinal features: inflammation and autoimmunity, vasculopathy, and excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) production and deposition. Immune dysregulation and inflammation are central processes, particularly early in the disease course, that ultimately lead to fibrosis, the clinical hallmark of SSc.

The molecular pathogenesis of tissue fibrosis in SSc shares similar pathways and mechanisms with wound healing (Wynn, 2007). During wound healing, tissue damage triggers the recruitment of inflammatory cells and the production of growth factors, inflammatory cytokines, and profibrotic cytokines. TGF-β is a central cytokine that drives recruitment and proliferation of fibroblasts and extracellular matrix (ECM) production (Douglas, 2010). TGF-β also is a critical differentiation factor leading to the accumulation of myofibroblasts (Hinz, 2007; Tomasek et al., 2002). In chronic wounds, these processes are disrupted leading to persistent inflammation, prolonged proteolytic activity and tissue damage, and excessive ECM deposition (Desmouliere et al., 2005; Gabbiani, 2003; O'Kane and Ferguson, 1997).

Dermal fibrosis in SSc also involves similar pathways including inflammation, fibroblast proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation, and ECM deposition (Abraham and Varga, 2005; Varga and Abraham, 2007; Varga and Whitfield, 2009). Skin biopsies of early SSc skin demonstrate perivascular infiltrates of mononuclear inflammatory cells, including CD4+ T-cells and macrophages, as well as upregulated TGF-β and chemokine expression (Fleischmajer et al., 1977; Higley et al., 1994; Varga and Abraham, 2007). TGF-β contributes to the development of dermal fibrosis, in part, through activation of downstream pathways, including SMAD 2/3, ERK and CCN2 (CTGF) (Brigstock et al., 2003). These processes lead to an increased numbers of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts and ECM deposition. (Chen et al., 2005; Kissin et al., 2006; Leask et al., 2001; Sargent et al., 2010; Varga and Whitfield, 2009).

Osteopontin (OPN) is a multifunctional matricellular protein produced by a broad range of cells including osteoclasts, osteoblasts, T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and fibroblasts (Anborgh et al., 2011; Rittling, 2011; Wang and Denhardt, 2008). Within the ECM, OPN binds to cell surface integrins and CD44 and modulates signaling in a wide variety of cell types (Anborgh et al., 2011; Rittling, 2011). OPN promotes inflammation through the recruitment of macrophages, dendritic cells and T cell and contributes to the development of Th1 cytokine responses (Ashkar et al., 2000; Rittling, 2011; Zheng et al., 2009). Finally, OPN also regulates fibroblast behavior and myofibroblast differentiation (Lenga et al., 2008). Expression of OPN in normal, healthy skin is low but increased during wound healing (Chang et al., 2008; Liaw et al., 1998; Sharma et al., 2006). Interestingly, OPN deficient (OPN−/−) mice have altered wound healing, with smaller collagen fibrils and disorganized ECM (Liaw et al., 1998). A subsequent report demonstrated that inhibition of OPN altered wound healing (Mori et al., 2008).

The expression of OPN in diseases that involve dermal fibrosis has not been thoroughly described. Interestingly, OPN was among a list of upregulated genes expressed in SSc skin in a study that utilized microarray analyses comparing SSc skin and healthy control skin (Gardner et al., 2006). A recent letter to the editor reported elevated OPN levels in a small cohort of SSc patients (Lorenzen et al., 2010). These data, combined with the established roles of OPN as a matricellular signaling modifier, make OPN an intriguing candidate mediator of dermal fibrosis. We hypothesized that OPN contributes to the development of dermal fibrosis. Accordingly, we sought to determine if OPN is increased in a large cohort of SSc patients and if OPN is a mediator of fibrosis in the bleomycin induced dermal fibrosis murine model.

RESULTS

Plasma Osteopontin Levels in Systemic Sclerosis Patients

The cohort consisted of 144 healthy controls and 320 scleroderma patients of similar ages (Table 1). Circulating OPN levels were determined in plasma from SSc patients and compared to control subjects (Figure 1A and B). In controls, age did not affect OPN levels but males were noted to have significantly higher mean OPN levels compared to females (males 39130±6100 pg/ml, females 19150±4538 pg/ml, p=0.008). Compared to healthy controls, SSc patients had higher OPN levels (p=0.0009). This difference was larger in female SSc patients compared to female controls (female SSc 45760±3610 pg/ml, p=0.0003). Male SSc patients tended to have higher OPN levels compared to male controls (male SSc 62660±12350 pg/ml, p=0.06). This slight difference may reflect the fewer male SSc cases examined than female SSc cases. There was no correlation with disease duration and OPN levels. Both patients with limited and diffuse SSc had increased OPN levels relative to controls (Figure 1A, p=0.009 and p=0.001, respectively), but no difference was observed between limited and diffuse SSc patients.

Table 1.

Human Subject Demographics.

| Healthy Control (n=144) | SSc Patuebts (n=320) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female = 78 Male = 66 |

Female = 279 Male = 40 |

| Age | 48.8±13.3 years | 52.5±12.1 years |

| Disease Duration | 6.2±7.4 years | |

| SSc type | Limited = 175 Diffuse = 143 |

|

| Autoantibodies | ANA+ = 0 | ANA+ = 320 ACA+ = 80 ATA+ = 80 ARA+ = 79 Ab Neg = 80 |

Figure 1. Osteopontin expression in SSc patients and Fibrotic mouse dermis.

(A) Plasma levels of OPN are increased in SSc patients overall and in limited and diffuse SSc compared to controls. Data presented as mean±SEM. (B) Plasma levels of OPN are increased in SSc-associated antibody (ACA, ATA, ARA) subsets of patients compared to controls. (C–H) IHC analyses with anti-OPN antibody demonstrates increased OPN immunoreactivity in skin from SSc patients (F–H) compared to controls (C–E). Scale bar is 200 µm (c,f), 50 µm (d, e) and 20 µm (e, h). (I) Increased number of fibroblasts (spindle shaped cells) and inflammatory cells (round cells) with OPN immunoreactivity were observed in control (open bars) compared to SSc skin (black bars). (J) qRTPCR analysis of total RNA from lesional skin of wild type mice received daily injection of bleo or PBS for 28 days demonstrates increased expression of OPN after bleo injection. Data presented as mean ± SEM of duplicated determinations from 10 mice per group. *p<0.05. (K) IHC analysis of bleo injected mouse skin demonstrated increased OPN expression compared to PBS injected skin. Scale bar is 200 µm in panel 1 and 3, and 50 µm in panel 4.

The scleroderma-associated autoantibodies (anti-centromere (ACA), anti-topoisomerase I (ATA), and anti-RNA polymerase III (ARA) subcategorize SSc patients into clinical subsets with a predisposition to developing certain systemic clinical manifestations such as pulmonary hypertension, interstitial lung disease and scleroderma renal crisis, respectively. (Arnett, 2006; Reveille et al., 2001) Therefore it was of interest to compare OPN levels in each group based on the presence of ACA, ATA and ARA. (figure 1B). Patients who had a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test but were negative for ACA, ATA, and ARA were called ACA/ATA/ARA Neg. OPN levels were elevated in all autoantibody subsets compared to healthy controls (p=0.03, 0.02, 0.0002, 0.03, respectively). Additional analyses were performed to determine if OPN levels were associated with clinical features of SSc. Compared to controls, SSc patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD), pulmonary hypertension (PHT), SSc renal crisis, or myositis had elevated OPN levels (p<0.0001, P=0.001, p<0.0001, p=0.009, respectively). However, comparison of patients without any of those four clinical features with patients with ILD, PHT, renal crisis or myositis demonstrated that only patients with ILD (p=0.04) and renal crisis (p=0.004) had increased OPN levels.

Expression of osteopontin in SSc skin biopsies

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on control (n=5) and SSc skin biopsies (n=8) to determine the expression patterns of OPN. Skin biopsies from controls demonstrated little OPN reactivity (Figure 1C–E) in the epidermis, papillary and reticular dermis. In contrast, SSc skin demonstrated increased OPN reactivity in the epidermis and dermis (Figure 1F). Within the dermis, OPN reactivity localized to fibroblastic cells (Figure 1G) and inflammatory cells. These data were quantified and presented in figure 1I. These data demonstrate that OPN is expressed in SSc skin, localizing to dermal fibroblasts and infiltrating inflammatory cells.

Expression of osteopontin in the bleomycin-induced dermal fibrosis model

The bleomycin (bleo)-induced dermal fibrosis model is commonly used to study biological pathways that are shared between the model and SSc (Yamamoto, 2002; Yamamoto and Nishioka, 2002, 2005). As seen in figure 1J, OPN mRNA level was significantly increased in bleo-induced fibrotic lesional skin compare to PBS injected skin (day 28). OPN reactivity by IHC was observed in the basal layer of epidermis, hair follicles and endothelial cells of bleo injected skin with relatively low reactivity in PBS injected skin (figure 1K). Interestingly, strong OPN reactivity was observed in fibroblast-like and inflammatory cells in the bleo-induced fibrotic skin. These data demonstrate that similar to SSc, OPN expression is increased in fibrotic skin in the bleo-induced dermal fibrosis model.

Osteopontin is a mediator of dermal fibrosis

To investigate the role of OPN in the development of dermal fibrosis, the bleo-induced dermal fibrosis model was performed in wild type (WT) and OPN deficient mice (OPN−/−). Lesional skin was analyzed on day 28. Histological analyses of lesional skin stained with H&E (figure 2A) demonstrated that bleo injections increased dermal thickness with obliteration of the subcutaneous adipose layer in WT mice compared to PBS injections. In contrast, the increase in dermal thickness induced by bleo in OPN−/− mice was significantly reduced relative to WT (Figure 2A, quantitative analysis in Figure 2B, p<0.001) and the subcutaneous adipose layer was relatively preserved. Masson’s trichrome staining demonstrated less deposition of extracellular matrix (blue) and less compaction of the matrix in the OPN−/− mice relative to WT mice (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. OPN−/− mice have reduced skin fibrosis in the bleomycin induced dermal fibrosis model.

OPN−/− and wild type mice received daily s.c. injections of PBS or bleomycin for 28 days, and lesional skin was examined. (A) H&E stain and Masson’s trichrome (MT). Scale bar = 200 µm. (B) Quantification of dermal thickness. The results represent the mean±SEM, 15 mice/group. Open bars, PBS; closed bars, bleomycin. *p<0.001. (C) Soluble collagen was quantified by Sircol colorimetric assay (Data presented as mean ± SEM, from 15 mice/group. Open bars, PBS; closed bars, bleomycin. *p<0.05). (D) Total RNA from lesional skin was analyzed for Col1a1 mRNA by qRTPCR. Data presented as mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations from 6 mice/group, *p<0.05.

To further quantify the amount of dermal fibrosis, soluble collagen content (Figure 2C) and col1a1 mRNA levels (Figure 2D) were measured using Sircol assay and qRT-PCR, respectively. Bleo increased collagen content in the skin of WT mice. In contrast, collagen was markedly reduced in the OPN−/− skin injected with bleo compared to WT (p<0.05). Similarly, OPN−/− skin injected with bleo had less col1a1 mRNA relative to wild type skin injected with bleo (p<0.05). Together these data demonstrate that OPN−/− mice have reduced dermal fibrosis in the bleo-induced dermal fibrosis model, indicating that OPN is an important mediator in the development of dermal fibrosis.

OPN−/− mice have reduced dermal inflammation

Dermal fibrosis in the bleo model results from the recruitment of inflammatory cells into the dermis which subsequently promote myofibroblast differentiation and ECM deposition. OPN has been reported to have both proinflammatory and profibrotic properties (Ashkar et al., 2000; Pardo et al., 2005). Therefore it was of interest to determine if the lack of OPN modulated the infiltration of dermal macrophages and inflammatory cytokines in the bleo-induced dermal fibrosis model.

IHC using anti-Mac-3 antibodies was performed on lesional skin biopsies after 28 days of SQ bleo or PBS control to label dermal macrophages. IHC images can be viewed in Supplementary figure 1A. Quantification of number of dermal Mac-3 positive cells in lesional biopsies demonstrated that OPN−/− mice injected with bleo had fewer Mac-3 positive macrophages compared to WT mice injected with bleo (Figure 3A, p<0.01). Consistent with a decrease in the number of Mac-3 positive cells, OPN−/− skin also had lower levels of CCL-2 mRNA (Figure 3B) and IL-6 mRNA (Figure 3C) as determined using qRTPCR. These data indicate that OPN−/− mice have decreased dermal inflammation in the bleo-induced dermal fibrosis model.

Figure 3. OPN−/− mice have decrease dermal inflammation.

(A) IHC with anti-MAC-3 antibody was performed on lesional skin from mice injected with PBS or bleo The number of Mac-3 positive macrophages was quantified in 6 high powered fields per mouse (4 mice per group, **p<0.01). Inflammatory cytokine mRNA level were decreased in OPN−/− mice injected with bleomycin compared to wild type mice (b. CCL-2, c. IL-6; 6 mice per group, *p<0.05.) Data presented as mean ± SEM. Open bars, PBS; closed bars, bleomycin.

Decreased myofibroblasts in OPN−/− skin

The myofibroblasts is an important cell in the development of fibrosis (Gabbiani, 1992; Hinz, 2007). Under the influence of TGFβ, myofibroblasts secrete large amounts of extracellular matrix, resulting in increased dermal thickness. We next sought to determine if the number of myofibroblasts were different in WT and OPN−/− mice in the bleo-induced dermal fibrosis model. IHC using antibodies against α-smooth muscle actin (SMA), a marker for myofibroblasts, was performed on lesional skin biopsies of wild type and OPN−/− mice. As seen in Supplementary Figure 1B and quantified in Figure 4A, OPN−/− skin injected with bleo had fewer SMA positive cells compared to WT skin injected with bleo (p=0.01). These data were further confirmed using qRTPCR assessment of SMA (Figure 4B). Bleo increased SMA expression in WT skin relative to PBS, but not OPN−/− mice. Together these data demonstrate that lesional skin in OPN−/− mice has decreased numbers of myofibroblasts.

Figure 4. OPN−/− mice have decreased TGFβ and downstream pathways.

(A) IHC with anti-SMA antibody was performed on lesional skin from mice injected with PBS or bleo. IHC with anti-SMA antibody demonstrated decreased myofibroblasts in OPN−/− mice Data presented as mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations in at least 6 microscopic fields, four mice/group. Open bars, PBS; closed bars, bleomycin. *p=0.0076. Total mRNA from lesional skin of OPN−/− mice injected with bleo demonstrated decreased levels of (B) SMA, (C) TGFβ, (D) CCN2, and (E) PAI-1.Data presented as mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations from 6 mice/group, *p<0.05.

OPN−/− mice have decreased TGFβ activation in vivo

Given the importance of TGFβ in the development of dermal fibrosis and myofibroblast differentiation, activation of TGFβ and its associated pathways was determined in vivo. Total RNA was isolated form lesional skin of WT and OPN deficient mice injected with PBS or bleo and used for qRTPCR. Interestingly, TGFβ levels induced by bleo was reduced in OPN−/− mice relative to WT mice (Figure 4C). In addition, OPN−/− skin also had lower levels of CCN2 mRNA (Figure 4D) and PAI-1 mRNA (Figure 4E), two genes that are increased by TGFβ.

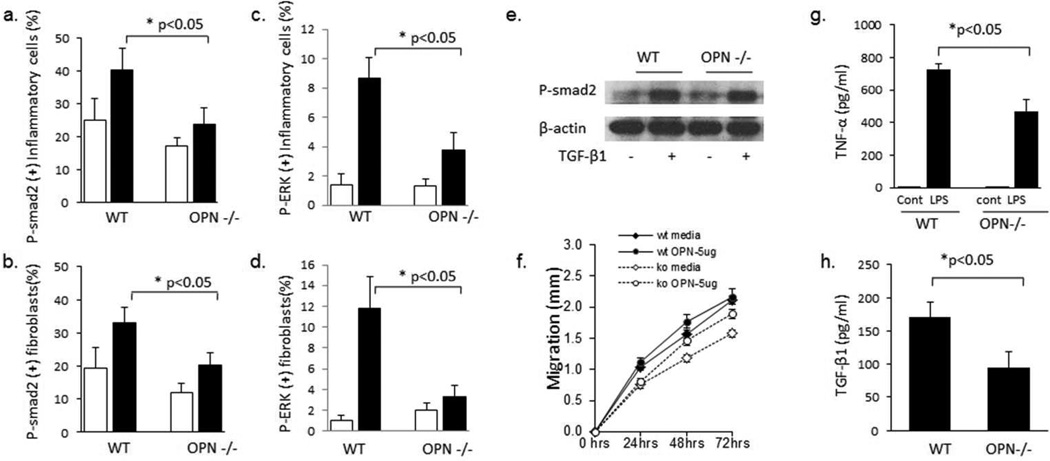

To further investigate whether OPN−/− mice had decreased activation of TGFβ pathways, lesional skin from WT and OPN−/− mice injected with PBS or bleo was used to determine the number of cells positive for the phosphorylated form of SMAD2 (pSMAD2) and ERK (pERK) by IHC. As seen in Supplementary figure 1C and quantified in figure 5A and 5B, bleo induced an increase in the number of inflammatory cells (Figure 5A) and fibroblasts (figure 5B) with immunoreactivity to pSMAD2. OPN−/− mice injected with bleo had a significant decrease in the number of number of inflammatory cells and fibroblasts with immunoreactivity to pSMAD2 relative to WT mice. Similar to pSMAD2, OPN−/− mice injected with bleo also had a significant decrease in the number of number of inflammatory cells and fibroblasts with immunoreactivity to pERK relative to WT mice (Figure 5C, D). These data are consistent with decreased activation of TGFβ pathways in vivo, however do not distinguish between a direct effect of OPN on the dermal fibroblast or an indirect in vivo effect through other cells or due to decrease TGFβ levels in OPN−/− mice.

Figure 5. OPN−/− mice have decreased phosphorylated SMAD2 in vivo but not in vitro.

IHC with anti-pSMAD2 antibody (A,B) or pERK antibody (C,D) was performed on lesional skin from mice injected with PBS or bleo. OPN−/− mice had decrease numbers of pSMAD2 inflammatory cells (A) and fibroblasts (B) after bleo injection. OPN−/− mice also had decrease numbers of pERK inflammatory cells (C) and fibroblasts (D) after bleo injection. Data presented as mean ± SEM in at least 6 microscopic fields, 4 mice per group. In contrast, in vitro stimulation of dermal fibroblasts with TGFb resulted in similar levels of SMAD2 phosphorylation in wild type and OPN−/− cells (E). (F) OPN−/− dermal fibroblasts had less migratory capacity in the scratch wound assay compared to wild type dermal fibroblasts which is partially restored by 5 µg/ml of OPN (representative of n=3 WT and 3 OPN−/−). (G,H) Bone marrow derived macrophages OPN−/− mice produced less TNFα (G) and TGFβ (H) relative to WT macrophages (WT n=4, OPN−/− n=4). Data presented as mean ± SEM.

To determine if OPN modulates the behavior of dermal fibroblasts in vitro, dermal fibroblasts from wild type and OPN−/− mice were stimulated with TGFβ and pSMAD2 was assessed by western blotting. As seen in figure 5E, TGFβ induced similar levels of phosphorylation of SMAD2 in both OPN deficient and WT dermal fibroblasts. In addition, mRNA levels of type I collagen and CCN2 were similarly induced by TGFβ in WT and OPN−/− dermal fibroblasts (data not shown). To determine if OPN regulates the migratory capacity of dermal fibroblasts, WT and dermal fibroblast migration was assessed using an in vitro wound closure assay (figure 5F). Interestingly, OPN−/− dermal fibroblasts had decrease migration relative to WT dermal fibroblasts. OPN was able to partially restore the migration of OPN−/− dermal fibroblasts. These data demonstrate that although OPN does not appear to modulate canonical TGFβ signaling in dermal fibroblasts, it is involved in dermal fibroblast migration.

To determine if TGFβ production by macrophages is modulated by OPN, bone marrow derived macrophages were cultured from WT and OPN−/− mice. Stimulation WT macrophages with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) increased TNF-alpha production, which was attenuated in OPN−/− macrophages (Figure 5G). Interestingly, basal production of TGFβ was also reduced in OPN−/− macrophages relative to WT macrophages (Figure 5H). These data demonstrate that TGFβ production is modulated by OPN. Combined with the in vivo decrease in TGFβ (figure 4C), these data suggest that one mechanism by which OPN regulates dermal fibrosis may be through modulation of TGFβ production.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we demonstrate that circulating levels of OPN are elevated in SSc patients, including both limited and diffuse as well as the autoantibody subsets of SSc patients. OPN expression also can be identified in lesional skin of SSc patients, localizing to both fibroblasts and inflammatory cells. Interestingly, when challenged with subcutaneous bleomycin, OPN−/− mice have decreased dermal thickness and dermal fibrosis. Additional studies demonstrate that OPN regulates the infiltration of macrophages to the skin as well inflammatory mediators and the TGFβ pathway in lesional skin in the bleo-induced dermal fibrosis model. In vitro studies demonstrate that OPN modulates TGFβ production by macrophages providing further evidence that one mechanism by which OPN modulates dermal fibrosis may be through TGFβ production. However, given the ability of OPN to regulate fibroblast migration, it is likely that OPN regulates multiple steps in the pathogenesis of dermal fibrosis, including fibroblast behavior as well.

OPN has been hypothesized to play a role in multiple physiological and pathophysiological states, including post-infarction myocardial remodeling and pulmonary diseases (Matsui et al., 2004; O'Regan, 2003; Schneider et al., 2010; Trueblood et al., 2001). Expression of OPN is increased post-myocardial infarction and OPN−/− mice have exaggerated left ventricular dilatation, suggesting that OPN plays a role in post-MI left ventricular remodeling (Trueblood et al., 2001). In addition, OPN−/− mice had decreased collagen content and cardiac fibrosis post-infarction and in the angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy model relative to wild type mice (Matsui et al., 2004; Trueblood et al., 2001). With regards to pulmonary diseases and models, several studies also have demonstrated that OPN expression is increased in mouse models of pulmonary fibrosis and in patients with chronic lung diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (Pardo et al., 2005; Prasse et al., 2009; Schneider et al., 2010). Lack of OPN decreases lung fibrosis in the intratracheal bleomycin induced lung fibrosis model (Berman et al., 2004; Takahashi et al., 2001). Furthermore, OPN induces fibroblast migration, proliferation and production of type I collagen (Pardo et al., 2005; Takahashi et al., 2001). Our studies now demonstrate that OPN plays a role in the development of dermal fibrosis. Together these studies indicate that OPN is an important mediator of the fibrotic response in multiple tissues.

The mechanism by which OPN contributes to the development of fibrosis is not known. Given the expression and responsiveness of OPN by multiple cellular components including inflammatory cells as well as mesenchymal cells, it is likely involved in multiple steps of the fibrotic process. Data from the current manuscript support a role for OPN in regulating dermal inflammation, TGFβ production, and fibroblast behavior.

OPN has multiple immunoregulatory effects. OPN is essential for the plasmacytoid dendritic cells production of IFN-α, a cytokine that is increased in SSc patients (Shinohara et al., 2006; Tan et al., 2006). OPN has been shown to support Th1 cytokine responses through the IL-12 production by macrophages and IFN-γ production by T-cells (Ashkar et al., 2000). Although SSc is often considered aTh2 disease, Th1 cells can be cultured from the skin of SSc patients and circulating Th1 cytokines are increased in SSc patients (Fujii et al., 2004; Valentini et al., 2001). Several studies have also demonstrated a role for OPN in macrophage migration and recruitment to sites of inflammation (Ashkar et al., 2000; Zheng et al., 2009). Consistent with this, OPN−/− mice had fewer numbers of Mac3+ cells in the dermis after bleomycin injection. Additional support for a role for OPN in macrophage recruitment is the decrease in CCL2, an important macrophage chemotactic factor, in OPN−/− mice. Therefore, one mechanism by which OPN regulates dermal fibrosis may be through the macrophage recruitment to the skin.

In addition to macrophage recruitment, our data supports a role for OPN in regulation of TGFβ production and downstream responses. Transcript levels of TGFβ and downstream genes such as CCN2 and PAI-1 and the number of cells expressing phosphorylated SMAD2 and ERK were decreased in OPN−/− mice. Furthermore, OPN deficient bone marrow derived macrophages produce less TGFβ in vitro. These data are consistent with a recent report investigating dystrophic muscle in mdx mice where muscle levels of TGFβ levels were reduced in OPN−/− mice (Vetrone et al., 2009). A major role for TGFβ in the fibrotic process is the promotion of myofibroblast differentiation. Consistent with this, OPN−/− mice had decreased SMA and SMA+ cells in the skin. These data suggest that through modulation of TGFβ, OPN may regulate the downstream fibrotic process.

Finally, OPN may also modulate the behavior of dermal fibroblasts directly. OPN has been reported to be a critical factor in myofibroblast differentiation in cultured cardiac and dermal fibroblasts, which could be important in the fibrotic process (Lenga et al., 2008). OPN also has been reported to play a role in the regulation of fibroblast proliferation and migration (Kohan et al., 2009; Pardo et al., 2005), which also could contribute to the development of dermal fibrosis. Finally, OPN also has been reported to regulate the expression of matrix metalloproteinases, which could increase the clearance of the ECM (Desai et al., 2007; Rangaswami and Kundu, 2007). In the current manuscript we do observe a role for OPN in dermal fibroblast migration, but do not see OPN-dependent differences in SMAD2 phosphorylation in response to TGFβ. However, these data do not rule out the possibility of OPN modulating other TGFβ driven signaling pathways such as ERK (Chen et al., 2005). Combined these previously published findings suggest that OPN may not only regulate the development of dermal inflammation and TGFβ production, but may also directly regulate the behavior of the fibroblasts in response to TGFβ and other mediators.

The increased plasma levels of OPN in SSc patients may have clinical importance. OPN levels have been reported to be increased in other diseases including rheumatoid arthritis (Zheng et al., 2009) and hepatic fibrosis (Huang et al., 2010); therefore, it will not likely be a diagnostic marker in and of itself. However, OPN may represent a prognostic marker and perhaps a disease activity marker. Indeed, OPN levels correlate with C-reactive protein levels in RA and the severity of hepatic fibrosis (Huang et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2009). An important limitation of the SSc samples used in the current study is the cross sectional approach. Future studies, using prospective samples and clinical data will be needed to determine if OPN levels have clinical utility in SSc patients. OPN levels are detectable and increased in SSc patients. It is interesting that OPN is elevated in the ACA+, ATA+ and ARA+ subsets of SSc. In particular the ARA+ patients tended to have even higher levels of OPN. Given the clinical significance of these autoantibodies, it will be important to determine if OPN levels correlate with specific clinical outcomes such as ILD, PHT, and SSc renal crisis. The current data demonstrate an association ILD and renal crisis, but additional studies are needed that control for multiple important clinical factors such as disease duration, autoantibodies, and treatment.

In conclusion, OPN levels are increased in SSc patients and in vivo studies in a murine model demonstrate an important role for OPN in the development of dermal fibrosis. Future studies seeking to understand the molecular mechanisms of the role of OPN in the development of dermal inflammation and fibrosis are needed. These data suggest that OPN may be a novel therapeutic target or biomarker in SSc. Additional studies using large prospective cohorts of patients are needed to advance our knowledge of the role of OPN in SSc and translate these findings into clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Osteopontin null (OPN−/−) mice and wild type (C57BL/6J; male) were acquired from Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) (Liaw et al., 1998; Schneider et al., 2010). The protocols were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHSC-Houston) Animal Care and Use Committee.

Systemic sclerosis patients and controls

SSc patients (n=320) and unrelated healthy controls (n=144) were selected from the Scleroderma Family Registry and DNA Repository and the Genes versus Environment in Scleroderma Outcomes Study (GENISOS). (Gourh et al., 2009) All SSc patients were classified based on the presence of scleroderma associated autoantibodies including ACA, ATA, and ARA. SSc patients negative for antinuclear antibodies were excluded from this study. Patients who had a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test but were negative for ACA, ATA, and ARA were called ACA/ATA/ARA Neg. The patients were classified as having limited or diffuse cutaneous SSc (LeRoy et al., 1988). All subjects provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the institutional review board of UTHSC-Houston, in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Plasma Osteopontin ELISA

OPN ELISAs were performed on plasma using an ELISA Duo Set. (R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN) Results are given as mean ± SEM in pg/ml.

Bleomycin induced skin fibrosis model

Bleomycin (0.02 units /day) (Teva Parenteral Medicines, Irvine, CA) dissolved in saline or saline alone was administered to eight week old mice by daily subcutaneous injections. On day 28, mice were sacrificed and lesional skin was obtained for protein lysates, total RNA, and histology (Takagawa et al., 2003). Each group consisted of 10–15 mice.

Histochemical studies and Immunohistochemistry

Five µm thick sections of paraffin-embedded skin tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Masson’s Trichrome. Skin fibrosis was quantified by measuring the thickness of the dermis, defined as the distance between the epidermal-dermal junction to the dermal-adipose layer junction, at six randomly selected sites/microscopic fields in each skin sample. (Wu et al., 2009) To analyze the accumulated collagen content in the lesional skin, deparafinized sections were stained with Masson’s Trichrome.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performing using antibodies against OPN (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), α-smooth muscle actin (SMA, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), Mac-3 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), phosphorylated-ERK (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or phosphorylated-SMAD2 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Specific isotype immunoglobulin served as negative controls. Bound antibodies were detected with secondary antibodies from Histomouse kit (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) and Vectastain kit (Vectorlabs, Burlingame, CA). Fibroblasts were identified by their spindle-shape morphology and inflammatory cells were identified by round morphology. Cells were counted and averaged in 6 randomly obtained high powered fields.

Determination of mRNA levels by quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from lesional skin tissue using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), and purified with RNA mini kit (Qiagen). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRTPCR) was performed using validated TaqMan Gene Expression Assays for Col1a1, IL-6, CCL-2, TGFβ SMA, CCN2, and PAI-1 (Applied Biosystems). Cyclophilin (PPIA) was used as an endogenous control to normalize transcript levels of total RNA of each sample. The data were analyzed with SDS 2.3 software using the comparative CT method (2-ΔΔCT method).

Quantification of tissue collagen

The collagen content of skin was determined by Sircol Collagen Assay (Biocolor, Newtown Abbey, UK). Collagen content was normalized to total protein content (Bradford assay; Biorad, Hercules, CA ).

Fibroblast and macrophages cultures and in vitro studies

Dermal fibroblasts were explanted from the dorsal skin of 6–8 week-old wild-type and OPN deficient mice and studied in parallel (Agarwal et al., 2011). Dermal fibroblasts from passage 3–5 were used in experiments.

To determine SMAD2 phosphorylation, dermal fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM-FBS overnight, followed by an overnight incubation in DMEM with 0.1% BSA. Cultures were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of TGFβ1 (R&D Systems Inc) for 24 hours. Protein lysates were used for western blotting using anti-pSMAD2 or anti-beta actin antibodies.

Cell migration was analyzed by wound-closure assay (Wu et al., 2009). Confluent monolayers dermal fibroblasts were incubated in DMEM/BSA with mitomycin C to block proliferation. A single scratch was performed across monolayers. Cultures were incubated in DMEM/BSA or 10 µg/ml OPN (R&D Systems Inc) for 72 hours. The width of the gaps was measured using phase contrast microscopy at six different sites at each time point.

Bone marrow derived macrophages were obtained from femurs of wild type and OPN deficient mice. Cells were isolated, washed, and cultured in DMEM with 20% FBS and 50 µg/ml M-CSF for 7 days at 37°C/5% CO2. For in vitro stimulation, cells were reseeded and cultured with and without lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/ml) for 24 hours. Supernatants were assessed for TNF-α and TGF-β levels by ELISA (R&D Systems Inc, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the means ± SEM. Mann-Whitney’s U-test (in vivo studies) or Student’s t-test (in vitro studies and OPN levels) was used for comparison between two groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GRANT SUPPORT: This study was supported by the Scleroderma Foundation New Investigator Award (Dr. Agarwal), NIH/NIAMS-K08AR054404 (Dr. Agarwal), NIH/NIAMS 5T32AR052283-03 (Dr. Wu), NIH/NHLBI RO1HL70952-09 (Dr. Blackburn), NIH/NIAMS Center of Research Translation (CORT) in Scleroderma (P50AR054144) (Dr. Mayes and Tan), the NIH/NIAMS Scleroderma Family Registry and DNA Repository (N01-AR-0-2251) (Dr Mayes)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abraham DJ, Varga J. Scleroderma: from cell and molecular mechanisms to disease models. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal SK, Wu M, Livingston CK, Parks DH, Mayes MD, Arnett FC, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 upregulation by type I interferon in healthy and scleroderma dermal fibroblasts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R3. doi: 10.1186/ar3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anborgh PH, Mutrie JC, Tuck AB, Chambers AF. Pre- and post-translational regulation of osteopontin in cancer. J Cell Commun Signal. 2011;5:111–122. doi: 10.1007/s12079-011-0130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett FC. Is scleroderma an autoantibody mediated disease? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:579–581. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000245726.33006.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkar S, Weber GF, Panoutsakopoulou V, Sanchirico ME, Jansson M, Zawaideh S, et al. Eta-1 (osteopontin): an early component of type-1 (cell-mediated) immunity. Science. 2000;287:860–864. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JS, Serlin D, Li X, Whitley G, Hayes J, Rishikof DC, et al. Altered bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in osteopontin-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1311–L1318. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00394.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigstock DR, Goldschmeding R, Katsube KI, Lam SC, Lau LF, Lyons K, et al. Proposal for a unified CCN nomenclature. Mol Pathol. 2003;56:127–128. doi: 10.1136/mp.56.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PL, Harkins L, Hsieh YH, Hicks P, Sappayatosok K, Yodsanga S, et al. Osteopontin expression in normal skin and non-melanoma skin tumors. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:57–66. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7325.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles C, Clements P, Furst DE. Systemic sclerosis: hypothesis-driven treatment strategies. Lancet. 2006;367:1683–1691. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68737-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Shi-wen X, van Beek J, Kennedy L, McLeod M, Renzoni EA, et al. Matrix contraction by dermal fibroblasts requires transforming growth factor-beta/activin-linked kinase 5, heparan sulfate-containing proteoglycans, and MEK/ERK: insights into pathological scarring in chronic fibrotic disease. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1699–1711. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61252-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai B, Rogers MJ, Chellaiah MA. Mechanisms of osteopontin and CD44 as metastatic principles in prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmouliere A, Chaponnier C, Gabbiani G. Tissue repair, contraction, and the myofibroblast. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.130102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas HE. TGF-ss in wound healing: a review. J Wound Care. 2010;19:403–406. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.9.78235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmajer R, Perlish JS, Reeves JR. Cellular infiltrates in scleroderma skin. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:975–984. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Shimada Y, Hasegawa M, Takehara K, Sato S. Serum levels of a Th1 chemoattractant IP-10 and Th2 chemoattractants, TARC and MDC, are elevated in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiani G. The biology of the myofibroblast. Kidney Int. 1992;41:530–532. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast in wound healing and fibrocontractive diseases. J Pathol. 2003;200:500–503. doi: 10.1002/path.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner H, Shearstone JR, Bandaru R, Crowell T, Lynes M, Trojanowska M, et al. Gene profiling of scleroderma skin reveals robust signatures of disease that are imperfectly reflected in the transcript profiles of explanted fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1961–1973. doi: 10.1002/art.21894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourh P, Arnett FC, Assassi S, Tan FK, Huang M, Diekman L, et al. Plasma cytokine profiles in systemic sclerosis: associations with autoantibody subsets and clinical manifestations. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R147. doi: 10.1186/ar2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley H, Persichitte K, Chu S, Waegell W, Vancheeswaran R, Black C. Immunocytochemical localization and serologic detection of transforming growth factor beta 1. Association with type I procollagen and inflammatory cell markers in diffuse and limited systemic sclerosis, morphea, and Raynaud's phenomenon. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:278–288. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B. Formation and function of the myofibroblast during tissue repair. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:526–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Zhu G, Huang M, Lou G, Liu Y, Wang S. Plasma osteopontin concentration correlates with the severity of hepatic fibrosis and inflammation in HCV-infected subjects. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:675–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin EY, Merkel PA, Lafyatis R. Myofibroblasts and hyalinized collagen as markers of skin disease in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3655–3660. doi: 10.1002/art.22186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohan M, Breuer R, Berkman N. Osteopontin induces airway remodeling and lung fibroblast activation in a murine model of asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:290–296. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0307OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Sa S, Holmes A, Shiwen X, Black CM, Abraham DJ. The control of ccn2 (ctgf) gene expression in normal and scleroderma fibroblasts. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:180–183. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.3.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenga Y, Koh A, Perera AS, McCulloch CA, Sodek J, Zohar R. Osteopontin expression is required for myofibroblast differentiation. Circ Res. 2008;102:319–327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw L, Birk DE, Ballas CB, Whitsitt JS, Davidson JM, Hogan BL. Altered wound healing in mice lacking a functional osteopontin gene (spp1) J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1468–1478. doi: 10.1172/JCI1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen JM, Kramer R, Meier M, Werfel T, Wichmann K, Hoeper MM, et al. Osteopontin in the development of systemic sclerosis--relation to disease activity and organ manifestation. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1989–1991. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y, Jia N, Okamoto H, Kon S, Onozuka H, Akino M, et al. Role of osteopontin in cardiac fibrosis and remodeling in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2004;43:1195–1201. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000128621.68160.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori R, Shaw TJ, Martin P. Molecular mechanisms linking wound inflammation and fibrosis: knockdown of osteopontin leads to rapid repair and reduced scarring. J Exp Med. 2008;205:43–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kane S, Ferguson MW. Transforming growth factor beta s and wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Regan A. The role of osteopontin in lung disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:479–488. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo A, Gibson K, Cisneros J, Richards TJ, Yang Y, Becerril C, et al. Up-regulation and profibrotic role of osteopontin in human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasse A, Stahl M, Schulz G, Kayser G, Wang L, Ask K, et al. Essential role of osteopontin in smoking-related interstitial lung diseases. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1683–1691. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangaswami H, Kundu GC. Osteopontin stimulates melanoma growth and lung metastasis through NIK/MEKK1-dependent MMP-9 activation pathways. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:909–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reveille JD, Fischbach M, McNearney T, Friedman AW, Aguilar MB, Lisse J, et al. Systemic sclerosis in 3 US ethnic groups: a comparison of clinical, sociodemographic, serologic, and immunogenetic determinants. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2001;30:332–346. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2001.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittling SR. Osteopontin in macrophage function. Expert reviews in molecular medicine. 2011;13:e15. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411001839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JL, Milano A, Bhattacharyya S, Varga J, Connolly MK, Chang HY, et al. A TGFbeta-responsive gene signature is associated with a subset of diffuse scleroderma with increased disease severity. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:694–705. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider DJ, Lindsay JC, Zhou Y, Molina JG, Blackburn MR. Adenosine and osteopontin contribute to the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. FASEB J. 2010;24:70–80. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-140772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Singh AK, Warren J, Thangapazham RL, Maheshwari RK. Differential regulation of angiogenic genes in diabetic wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2323–2331. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara ML, Lu L, Bu J, Werneck MB, Kobayashi KS, Glimcher LH, et al. Osteopontin expression is essential for interferon-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:498–506. doi: 10.1038/ni1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagawa S, Lakos G, Mori Y, Yamamoto T, Nishioka K, Varga J. Sustained activation of fibroblast transforming growth factor-beta/Smad signaling in a murine model of scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:41–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi F, Takahashi K, Okazaki T, Maeda K, Ienaga H, Maeda M, et al. Role of osteopontin in the pathogenesis of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:264–271. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.3.4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan FK, Zhou X, Mayes MD, Gourh P, Guo X, Marcum C, et al. Signatures of differentially regulated interferon gene expression and vasculotrophism in the peripheral blood cells of systemic sclerosis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:694–702. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–363. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueblood NA, Xie Z, Communal C, Sam F, Ngoy S, Liaw L, et al. Exaggerated left ventricular dilation and reduced collagen deposition after myocardial infarction in mice lacking osteopontin. Circ Res. 2001;88:1080–1087. doi: 10.1161/hh1001.090842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentini G, Baroni A, Esposito K, Naclerio C, Buommino E, Farzati A, et al. Peripheral blood T lymphocytes from systemic sclerosis patients show both Th1 and Th2 activation. J Clin Immunol. 2001;21:210–217. doi: 10.1023/a:1011024313525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–567. doi: 10.1172/JCI31139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga J, Whitfield ML. Transforming growth factor-beta in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) Front Biosci (ScholEd) 2009;1:226–235. doi: 10.2741/s22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetrone SA, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Kudryashova E, Kramerova I, Hoffman EP, Liu SD, et al. Osteopontin promotes fibrosis in dystrophic mouse muscle by modulating immune cell subsets and intramuscular TGF-beta. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1583–1594. doi: 10.1172/JCI37662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KX, Denhardt DT. Osteopontin: role in immune regulation and stress responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:333–345. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Melichian DS, de la GM, Gruner K, Bhattacharyya S, Barr L, et al. Essential roles for early growth response transcription factor Egr-1 in tissue fibrosis and wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1041–1055. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:524–529. doi: 10.1172/JCI31487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T. Animal model of sclerotic skin induced by bleomycin: a clue to the pathogenesis of and therapy for scleroderma? Clin Immunol. 2002;102:209–216. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Nishioka K. Animal model of sclerotic skin. V: Increased expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin in fibroblastic cells in bleomycin-induced scleroderma. Clin Immunol. 2002;102:77–83. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Nishioka K. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bleomycin-induced murine scleroderma: current update and future perspective. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:81–95. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Li R, Pan H, He D, Xu R, Guo TB, et al. Role of osteopontin in induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 and macrophage inflammatory protein 1beta through the NF-kappaB and MAPK pathways in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1957–1965. doi: 10.1002/art.24625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.