Abstract

The intensive care unit (ICU) family meeting is an important forum for discussion about the patient’s condition, prognosis, and care preferences; for listening to the family’s concerns; and for decision making about appropriate goals of treatment. For patients, families, clinicians, and health care systems, the benefits of early and effective communication through these meetings have been clearly established. Yet, evidence suggests that family meetings still fail to occur in a timely way for most patients in ICUs. In this article, we address the “quality gap” between knowledge and practice with respect to regular implementation of family meetings. We first examine factors that may serve as barriers to family meetings. We then share practical strategies that may be helpful in overcoming some of these barriers. Finally, we describe performance improvement initiatives by ICUs in different parts of the country that have achieved striking successes in making family meetings happen.

Keywords: Family meetings, Intensive care, Communication, Quality improvement

1. Introduction

Among the most essential responsibilities of clinicians in the intensive care unit (ICU) is communication with patients and their families. Because ICU patients are usually unable to participate directly [1], complex discussions about diagnosis, prognosis, treatment plans, or patients’ care preferences occur more often with families (a term used broadly to include individuals who may or may not be relatives but are important in the patient’s life and may be legally authorized to make health care decisions). The “ICU family meeting” (or “family conference”) is generally understood to refer to this type of discussion, although the specifics of content, duration, venue, participants, and process may vary [2]. Frequently, the discussion addresses issues of pivotal importance—matters of life and death, literally—such as the benefits and burdens of intensive care therapies and the goals and values of the patient and family.

Evidence establishes the importance of the family meeting to critically ill patients and families. Over 3 decades of research, ICU families have consistently ranked communication as their preeminent concern, at least as important as caregivers’ clinical skills [3]. A recent randomized, controlled, multicenter trial showed that, together with the use of printed informational materials, proactive, protocolized meetings by ICU physicians with families of patients dying in the ICU significantly reduced the prevalence and level of family member anxiety and depression and posttraumatic stress disorder as long as 3 months after the death [4]. In-depth analyses of transcripts of family meeting audiotapes illuminate the relationship between specific clinician statements and family satisfaction [5,6]. It is also clear from a series of other studies that a scheduled and structured approach to family meetings can help to optimize efficient utilization of scarce and expensive ICU resources, as measured by length of stay in the ICU and hospital and duration of invasive treatments with limited clinical benefit [7–9]. Conversely, poor communication is associated with adverse outcomes for patients, families, clinicians, and health care systems [10–12].

Yet, research continues to reveal inadequacies in ICU communication [6,13,14]. One major problem is that family meetings fail to occur in a timely fashion; for many patients, no meeting is held at all, even during a prolonged ICU stay [9,13,15]. In a large, national survey of physician and nurse directors of ICUs, respondents affirmed the importance of regular meetings of clinicians with families but reported that such meetings were not conducted in two thirds of ICUs under their direction [13]. A minority few of ICU families in a leading academic medical center met with an attending ICU physician in the usual course of care [9]. Of 1500 patients in the multicenter Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments who were treated for more than 2 weeks in ICUs, fewer than 40% reported discussion with their doctor about prognosis or treatment preferences [16].

Why don’t family meetings take place promptly for most ICU patients? With unambiguous data showing benefit, what explains the failure to integrate this essential, evidence-based practice into regular care more consistently? Although empirical and theoretical articles have addressed how to approach family meetings in terms of content and process [2,5,6], we are unaware of published literature about how to increase their frequency and regularity as opportunities for optimal discussions. In this article, we begin by examining factors that may serve as barriers to family meetings. We then discuss practical strategies that may be helpful in overcoming barriers and making family meetings happen.

2. Barriers

Factors related to clinicians, to patients and families, and to processes, structures, and systems of care may serve as barriers to the implementation of family meetings in a timely and consistent basis. Table 1 summarizes potential barriers, which are discussed more fully below.

Table 1.

Barriers to family meetings in the ICU

|

2.1. Time

Few ICU physicians have the time to conduct thorough discussions on a regular basis with families of all patients under their care. In the United States, the average ICU cares for about 10 patients on any given day [17]. Available data about the duration of family meetings are limited, but approximately 30 minutes appears to be typical [4,6,9]. Based on these figures, an ICU physician would have to spend 5 hours a day to meet with each patient’s family. Additional time is needed to arrange and prepare for these meetings and to document them in medical records. For some patients and families, the issues are straightforward and can be covered relatively quickly; on occasion, a brief update may suffice. More and more, however, scarce ICU resources are restricted to patients with the highest acuity of illness, the most complex problems, and continual fluctuations of status. Discussions about these patients are not usually simple nor are they short. Families want not only information but also the opportunity to be heard; time for physicians to listen is then added to time in which they speak [18]. In addition, families of ICU patients are often emotionally distressed—anxious, depressed, traumatized, or grieving [4,12,19]. These forms of distress can interfere with the cognitive processing of information, which must therefore be given slowly and repeated to ensure comprehension. Attention to emotions, required for optimal communication with ICU families [6], also takes time.

In a large ICU staffed, as is common, by a single attending physician who has responsibility not only for all aspects of clinical care but also for teaching and administration, the physician’s time for family meetings is limited. Time is also an important issue for physicians who do not maintain a full-time presence in the ICU but instead make discrete visits for individual ICU patients while spending most of the workday in distant areas of the hospital or in community-based offices. Often, these visits occur during hours, such as the early morning, when family visiting in the ICU may be restricted. Multiple phone calls or other contacts may then be needed to establish a mutually acceptable meeting schedule, whereas more time will also be spent in traveling to and from the meeting. A physician who practices primarily outside the ICU may spend idle time waiting for a family member or for another participating clinician who fails to arrive at the appointed hour.

2.2. Multiple caregivers

Care of the ICU patient is often fragmented among multiple professionals. The primary care physician, if not an intensivist, may assume a less prominent role as critical care issues increase in importance. In a teaching hospital’s ICU, physicians at various levels of training are involved on a rotating basis. Even attending physicians who are primarily assigned to the ICU typically rotate and may change as often as twice a day. Most critically ill patients are also treated by a variety of specialists, each focusing on dysfunction of an individual organ or system; these physicians, too, transfer care among colleagues on different days, nights, and weekends. Multiple shifts of nurses add other layers of complexity. With so many caregivers for a single patient, none may be clearly identified as primarily responsible for meeting with the family. Each clinician may assume that another is playing this role (or prefer that another do so) and thus fail to initiate a family meeting. The family will often hesitate to take this initiative, particularly if it is not clear whom they should address.

Even if responsibility for communication is clear, dispersion of care among multiple professionals makes it more difficult for a single clinician to explain all essential components of the clinical situation, as families want and as informed family decision making requires. Ideally, a physician in this situation will prepare for a family meeting either by speaking in advance with colleagues who rotated off service and with consultants who are focusing on specific problems or by arranging to have these clinicians participate directly in the meeting. This process, however, is often difficult and time consuming, creating an impediment and a disincentive to communication with the family.

2.3. Skills

Effective communication with ICU families requires a high level of proficiency in multiple skills. The clinician must be able to explain complex physiology and technology in terms understandable by a layperson; to provide prognostic information while acknowledging uncertainty; to elicit information about values, goals, and treatment preferences of the patient; to listen with patience and sensitivity; to address emotions including anger, grief, and guilt; to attend to dynamics within the family; to assist in decision making about life-sustaining therapies; to describe and prepare families for a patient’s death; and to negotiate resolution of conflicts. In the ICU, clinicians face the further challenges of counseling families with whom they have no prior relationship but for whom there is now a crisis. Yet few physicians receive appropriate training or role modeling in any of these skills, and it is only very recently that an ICU-specific curriculum has been developed for this purpose [20].

In a national survey of ICU directors, inadequate training of physicians in communication skills was identified as a major barrier to high-quality palliative care for critically ill patients and their families [13]. Physicians lacking these skills are unable fully to utilize opportunities to meet informational, emotional, and other needs in family meetings. Feeling insecure (either consciously or unconsciously), they are also more likely to avoid these meetings altogether, focusing instead on tasks they know how to perform better and believe they can complete successfully. Deficiencies in communication skills thereby serve as a specific and important barrier to family meetings in the ICU, although one that many physicians may find difficult to recognize or acknowledge.

2.4. Culture and language

The challenges of communication are compounded by the diversity of needs of families from different cultures. Within ICUs in the United States and elsewhere, clinicians confront a broad range of attitudes not only about illness and death but also about disclosure of information, decision making, and life-prolonging therapies, as well as cross-cultural differences in family dynamics (on which the specifics of individual families are superimposed). Yet few clinicians have the training or knowledge to approach ICU communication in a culturally sensitive way. Although translators may be available to assist in meetings with families who speak a different language, evidence has recently emerged that translators frequently make material alterations when interpreting during family meetings, with potentially negative effects on communication between clinicians and families [21]. In addition, the translator may not always be readily available, adding to the burden and complexity of scheduling.

2.5. Stress

It is hard to overestimate the emotional stresses for clinicians practicing in the critical care setting. Death is a regular event, occurring more frequently in ICUs than anywhere else in the hospital [22]. Evidence suggests that physicians are often troubled by personal fears of dying [23] and also that repeated exposure to death during medical training is psychologically traumatic, particularly in the absence of supervision and input from experienced counselors at a senior level [24]. Long work shifts present dozens of decisions about triage and intensive care therapies, each carrying significant and often permanent consequences. With rapid changes in patient status, there is little “down time” for rest or relief of tension, especially in the face of institutional pressures to maximize bed turnover and minimize length of stay. Physical and emotional fatigue take their toll. The cumulative impact of these stresses contributes to the phenomenon of “burnout,” now recognized as a major problem for both physicians and nurses in the ICU [25,26].

Integration of palliative care as part of comprehensive critical care for all patients and families is increasingly accepted as the most appropriate approach, as contrasted with a more traditional model in which restorative and palliative care are seen as separate and sequential [27]. For ICU clinicians, however, practice in the newer model is challenging because they must integrate multiple goals in formulating and implementing each plan of care. On the one hand, every reasonable restorative effort that is consistent with the patient’s values and preferences must be made, whereas on the other, the comfort and dignity of the patient must be maintained. This is a delicate balance that may be emotionally as well as cognitively difficult, requiring continual recalibration and adjustment as the critical illness evolves. Attention to families, who have other needs and may have their own agenda, adds to the stresses that clinicians in the ICU face on a day-to-day basis. At times, these clinicians may instinctively avoid families as a strategy for emotional self-protection.

2.6. Space

Many ICUs lack a dedicated, private area that is suitable for family meetings [13]. Although this may seem like a minor issue, neither the impact on families nor the challenge of creating such a space is trivial. Families sometimes express concern that patients who appear unconscious may actually hear bedside discussions that are not intended for their ears while being unable to participate or signal awareness in a meaningful way. In addition, the patient’s “room” is really a cubicle at best, often without walls or even curtains, and invariably noisy and distracting. Because there are rarely enough chairs by the bed of a critically ill patient, the physician will often remain standing, implicitly ready to leave. Hallways, although a convenient and common venue for conversations between physicians and families, afford even less privacy than the bedside and convey even more strongly the impression that the physician’s departure is imminent. Discussions in open waiting areas not only violate the privacy of the patient and participating family members but may also disturb and distress other families who cannot avoid overhearing them.

The absence of an appropriate space for family meetings has been associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression among ICU families [12]. Although the mechanism of this association has not been empirically examined, it may result in part from the impact of inadequate space on the frequency, duration, and overall quality of meetings between clinicians and patients’ families. In most hospitals, space is at a premium and likely to be claimed for uses other than family meetings. Administrators at the hospital level and even in the ICU itself may not appreciate the importance of allocating space for this purpose, whereas clinicians may recognize the need but lack the authority and resources to address it. Clinicians probably feel as uncomfortable as families during discussions of sensitive issues in an inappropriate setting; if the only space available is unsuitable, they may tend to avoid these discussions altogether.

2.7. Ill-defined goals

Virtually every task is easier to perform when its nature and purpose are clearly defined. For ICU family meetings, however, this clarity is often lacking. Goals for family meetings are diverse and variable, influenced by factors including the patient’s medical status at a particular juncture, the availability of new diagnostic or therapeutic information, the family’s requests for discussion of specific topics or assistance with specific decisions, the history of prior communications with the family, and the clinician’s impressions of the family’s understanding, interest, and receptivity and of the family’s emotional profile and internal dynamic. Depending on these factors, the main goal of an individual family meeting may be to convey specific information, such as results of a diagnostic procedure; to review short-term projections and plans, such as the patient’s expected status and plan of care for the following day; or to establish overall care goals that are realistic and appropriate in light of the patient’s prognosis, values, and treatment preferences. Some family meetings focus on care at the end of life, including discussions about the potential benefits and burdens of life-sustaining therapies and about the process of withdrawing such therapies. Others are conducted primarily to provide emotional support to the family. The range of goals is broad, as are the corresponding levels of complexity. Many family meetings encompass multiple goals, whereas individual goals may be accomplished through multiple meetings. However, most ICUs lack a process either to articulate these goals clearly for families and for clinicians or to determine whether goals of meetings have been achieved. In the absence of well-defined goals, meetings are unlikely to satisfy any of the participants and, compared to activities with a clearer purpose, less likely to attract the time and attention of ICU clinicians.

3. Strategies that may be helpful

The Institute of Medicine has identified improvement of palliative care in the ICU, which includes effective communication with patients and their families, as a national health priority [28]. For all health care providers and fields, it has also prioritized “closing the gap” between current knowledge of optimal care and current clinical practice [29]. The ICU family meeting is known to be an effective strategy, positively associated with outcomes valued by patients, families, clinicians, and health care systems. How, then, can we implement this “best practice” in a more timely and consistent way? Our review of barriers to implementation can serve as a framework for suggested approaches, which are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Strategies to help make family meetings happen

|

3.1. Maximize time efficiency for physicians

Several strategies may help to maximize efficient use of physician time for family meetings without sacrificing physician involvement in discussions of essential topics. A first step is to ask physicians practicing in the ICU to identify days of the week and times of the day that would be most convenient for meeting with families. Their responses can be used to structure a weekly schedule in which specific time blocks that are generally manageable for the physicians are set aside for family meetings, to be used as needed. If no block is convenient for a particular physician, that individual might be able to make adjustments in the regular scheduling of other activities or, as a fallback, afforded flexibility to meet on a case-by-case basis at times outside the regular blocks. The main blocks could then be included in a printed schedule that is posted in the ICU and the family waiting area and also made directly available either as part of a general family information leaflet or as an independent document that is personally distributed by staff to each family visiting the ICU. Because families themselves may have conflicting commitments, such as for work or childcare, adjustments may need to be made on an ad hoc basis. Adjustments would obviously also be required when rapid or unexpected changes in the course of the patient’s illness call for an urgent meeting. The basic schedule, however, provides a solid framework for scheduling, gives notice to everyone, and establishes a presumption of availability during specified periods, both for physicians and for families.

During the family meeting, personal participation by the physician is essential. Families want to hear directly from the doctor in charge, particularly about the patient’s condition and prognosis. In general, it is also the physician who can best describe the overall plan of care and the benefits and burdens of specific treatments. The physician’s recommendations for treatment are usually very important to the family. With effective organization and assignment of other tasks, however, it is often possible to limit the time spent by physicians in family meetings to discussion of these core topics. Details of scheduling, for example, do not need to occupy the attending physician’s time but instead can be handled by a member of the ICU staff or a case manager with more availability and flexibility, to whom this responsibility can and should be formally assigned. Although they are also very busy, a physician trainee, nursing manager or staff, or a social worker may be able to play this role. This individual could also be responsible for notifying all those invited of the time of the meeting and for assembling participants other than the physician in the designated meeting area. By prior arrangement, the physician would be paged to arrive as the meeting is begun. This can save waiting time for physicians, but they must be prepared to respond promptly when contacted, so that the family and other participants are not made to wait. In addition, the family can be advised in advance that the physician will be present for discussion of certain topics but will leave after these are covered, whereas other members of the team will stay to answer questions, review issues, and provide additional emotional and practical support. By making family meetings less onerous for physicians in terms of time, strategies like these may help to make these meetings happen sooner and more often.

3.2. Use printed informational aids

Use of printed informational materials can serve as another strategy for achieving time efficiencies as well as other benefits in communicating with families. Two large, randomized, controlled trials have recently demonstrated the value of leaflets and brochures as resources for ICU families, including information about topics as emotionally sensitive as bereavement [4,30]. In addition, many high-quality randomized, controlled trials in other contexts establish that printed materials can serve as decision aids, improving knowledge relevant to treatment decisions, creating more realistic expectations of outcomes, and involving patients or families positively in decision making [31]. Such aids are effective for a diverse range of decisions, including decisions about life-sustaining treatments such as mechanical ventilation and tube feeding. They function best as a supplement rather than a replacement for the traditional process of counseling of patients and families by physicians. Printed materials may, however, suffice for certain information that families would otherwise seek or be given in a face-to-face meeting. Several innovative ICUs have also developed “family meeting booklets” that describe the general nature and purpose of the family meeting, review the typical roles of various participants, and encourage families to prepare in advance by identifying topics and formulating questions of interest. Materials like these can help to structure and focus discussion on key issues, which in turn may shorten meetings (without sacrificing core content) and thereby make it easier for clinicians to meet with families more regularly.

3.3. Educate physicians about reimbursement for time spent meeting with families

Regulatory language relating to payment for critical care services may be interpreted by some physicians as precluding reimbursement for time spent in family meetings. However, provisions applicable to care of Medicare beneficiaries specify circumstances in which such discussions are in fact reimbursable as critical care time. For purposes of billing for “critical care services” under the critical care Current Procedural Terminology codes 99291 and 99292, “time involved with family members or other surrogate decision makers, whether to obtain a history or to discuss treatment options (as described in Current Procedural Terminology), may be counted toward critical care time when these specific criteria are met: (a) the patient is unable or incompetent to participate in giving a history and/or making treatment decisions, and (b) the discussion is necessary for determining treatment decisions” [32]. A recent transmittal from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services explains that, “For family discussions, the physician should document: (i) the patient is unable or incompetent to participate in giving a history and/or making treatment decisions, (ii) the necessity to have the discussion…, (iii) medically necessary treatment decisions for which the discussion was needed, and (iv) a summary in the medical record that supports the medical necessity of the discussion” [33]. The Medicare payment policy is clear, however, that “All other family discussions, no matter how lengthy, may not be additionally counted towards critical care” [33]. To remove an unnecessary financial disincentive for family meetings, it is useful to educate physicians about the specifics of billing for time in such meetings and particularly about practices with respect to documentation that will support reimbursement for this type of service.

3.4. Include the family meeting in checklists, goal sheets, and other reminder tools

Successful implementation of “best practices” in other areas of ICU care suggests that use of simple reminders and triggers will also be effective in improving practice with respect to family meetings. It is now well documented that in a complex, high-intensity workplace like the ICU, the simplest of tools, a checklist, can play a crucial role in promoting frequency and consistency of adherence to best practice [34]. Following earlier demonstrations of their value in trauma and anesthesiology settings, checklists are increasingly used to facilitate translation of evidence into practice for ICU processes ranging from prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections to withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies. A similar strategy, implementation of a “daily goals form,” increased the proportion of doctors and nurses who understood the goals of patient care each day in the ICU from less than 10% to greater than 95% while also significantly reducing ICU length of stay [35]. The evidentiary foundation for effective communication with ICU families in general and for family meetings in particular is as strong as the data supporting any other ICU practice targeted by recent performance improvement initiatives, all of which have been enhanced by use of these practical tools. Along with other processes or activities, the family meeting can be included in an ICU checklist or on a daily goals sheet for each patient to help promote adherence to this important practice. This approach has the additional advantage of providing written documentation of adherence, which can be reviewed with clinicians for performance feedback and improvement.

3.5. Clarify goals of meetings using a simple tool

A simple tool can also be created for clarification of meeting goals. Such a tool might include a list of goals across the range that is common for ICU family meetings, from which clinicians can make choices based on their own as well as the families’ assessments of needs at a particular interval of the patient’s illness. The tool could provide space for identification of other goals that are less commonly targeted but that may be important in individual situations. The completed tool could then be made available to all participants in advance or at the start of the meeting. Models for such tools exist for other processes of care and communication, including analysis of defects in patient care and operating room briefings for surgical teams [36,37]. We have developed and are piloting a tool for identification of family meeting goals. Ideally, a tool of this type will be brief and straightforward so that its use does not impose additional burdens but rather helps to reduce them by making the purpose of the meeting clear to everyone involved and providing focus and priorities for the discussion. Identification of goals may also help to identify appropriate participants for particular meetings. Other potential benefits include promoting collaboration and coordination among multiple members of the health care team, improving the consistency of information that is provided to families, and integrating individual communications into a larger framework for decision making in accordance with patient values and preferences. This approach also provides a method for evaluating effectiveness by reference to whether the stated goals of the meeting were met.

3.6. Engage and empower nurses in the family meeting process

Almost universally, it is the bedside nurse who develops the closest relationship with both the ICU patient and the family. Physician presence is sporadic, whereas the nurse is involved constantly. For a variety of reasons, however, nurses are not always active participants in the family meeting process and may not be present when the physician conducts a family meeting away from the patient’s bedside. This is unfortunate because the nursing perspective is unique, families value communication by nurses, and nurses themselves express interest in expanding their role as well as frustration about perceived limitations [2]. Assuming it can be accomplished without interfering with other aspects of patient care, greater nursing involvement in family meetings can help to lighten the burdens of arranging and conducting meetings that are now shouldered primarily by physicians. Again, there are certain core topics that families will want to, and should, discuss with the physician, and we believe that the professional obligation of physicians includes participation in family meetings. Ideally, the nurse should also be involved because nurses can contribute in many valuable ways. One crucial role for the nurse is simply to focus the attention of the team on the need for a family meeting—this task can be specifically assigned to the nurse, possibly in conjunction with use of a checklist as a written reminder. Communication with the family is a care issue that would be appropriate for the nurse to raise on daily patient rounds and, as discussed above, to include on daily goals sheets. Nurses may be able to help with arranging the time and location of meetings, discussing with families what to expect and how to prepare, assembling and introducing participants, and bringing important family questions and insights about the patient and family to the attention of the physician. In addition, the nurse is often the only individual who is present for the bedside visits of multiple clinicians (and family members) and may therefore be able to help identify key participants for family meetings as well as to organize and integrate information from diverse caregivers into a larger framework. Functioning in these roles, the nurse can play an essential role in improving the consistency of information, which enhances family satisfaction and decision making [38]. It is likely that specific assignment of these kinds of responsibilities to nurses will enhance not only the frequency and timeliness of family meetings but also the quality and effectiveness of meetings and the personal gratification that these all-important providers derive from their work.

3.7. Involve other professionals and staff: social work, pastoral care, case management

The most effective ICU teams are truly interdisciplinary, encompassing and integrating the contributions not only of physicians and nurses but also of other professionals. As for most important areas of critical care practice, the approach to family meetings should take full advantage of the available range of these diverse resources. Along with nurses, social workers and pastoral care representatives can play a valuable role in facilitating family meetings. Social workers have specific training in family dynamics and skills for empathic listening and emotional counseling. They are also expert in management of transitions among care settings, often an important issue when continuation or discontinuation of critical therapies is discussed. They can explore possibilities for practical and financial support for families facing common burdens of a loved one’s critical illness. Spiritual support has been identified as a key domain of high-quality palliative care for critically ill patients and their families. Family members feel more supported in and satisfied with ICU decision making if pastoral care services are provided and if spiritual needs are discussed in a family meeting [39]. Family satisfaction with pastoral care is a significant determinant of satisfaction with the overall ICU experience [40]. Most participants in a family meeting will welcome the input of a pastoral care professional to the assessment and management of families’ (and patients’) spiritual needs, and physicians may be more willing to participate in meetings if this input is available. Social workers and chaplains can be a source of comfort, strength, and practical advice not only for ICU families but also for other members of the professional team. They are usually able and willing to assist with many challenging aspects of family meetings and should be recruited to help in planning and implementing a program for this purpose. In most ICUs, case managers collect data about a range of aspects of patient care; some ICUs have been successful in assigning these staff members to assist in facilitating arrangements for family meetings. Ethics consultants facilitate family meetings in ICUs in some institutions [7].

3.8. Provide positive reinforcement

If increasing the frequency of family meetings is identified as a goal, then clinicians who work to accomplish this goal ought to be rewarded. Not only does this strategy provide appropriate recognition and appreciation for the effort, but positive reinforcement is a powerful stimulus to repeat the behavior. Physicians and other ICU team members, like almost everybody else, take pride in doing their job well and are pleased to receive praise for a job well done. For those who are successful in conducting meetings in a timely way with a high proportion of families, positive reinforcement can take a variety of forms. For example, the ICU could create a special award for the physician who conducts the largest number of meetings with families in a specified period, post a photo of this physician on the unit, and disseminate news of the winner more broadly in the institution. Even a simple letter from an individual with administrative authority that acknowledges a special effort is usually a welcome expression of recognition and can become a valuable component of an employment file or professional portfolio. Whatever strategy is chosen, the impact will be felt, the behavior will be reinforced, and an additional incentive for excellence will be established.

3.9. Encourage and support training in communication skills

Clinicians with confidence in their communication skills and in their knowledge of relevant substantive content are more likely to embrace the responsibility to conduct family meetings than those who feel insecure in these areas. Compared to other strategies we have reviewed, training in skills is not as simple or straightforward, but it may be most important and likely to succeed. Rigorous evidence has established that communication skills can be taught effectively and that, using an appropriate pedagogic approach, these skills will endure over long-term follow-up [41]. Because trainers themselves need special skills, optimal training in communication may not be available at an individual institution but can be obtained through national programs. The pioneering End-of-Life Education for Physicians program [42] has for the past decade educated physicians across the country in communication and other skills. The End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) program provides similar training specifically for nurses [43]. In 2006, ELNEC introduced an ICU-specific “train-the-trainer” curriculum entitled “ELNEC—Critical Care,” which is composed of 8 modules including “Communication,” “Ethical Issues in Critical Care Nursing,” and “Loss, Grief and Bereavement” [44]. Nurses completing this program receive a range of materials for teaching others when they return to their local institutions. More recently, the National Palliative Care Research Center has supported development and preliminary implementation of a curriculum for training critical care fellows in communication skills [20]. This program includes 7 modules including one that is specifically devoted to “Conducting a Family Conference.” Ideally, future additions to this curriculum and others will focus specifically on training for culturally sensitive communication. Investment by an ICU or hospital in communication skills training for key ICU clinicians would likely be returned with a high yield in quantity as well as quality of family meetings.

3.10. Consult palliative care specialists

In our review of potentially helpful strategies, we have focused primarily on ICU teams and their internal capabilities. We believe that family meetings are a core responsibility for ICU clinicians, as much so as management of hemodynamic instability, respiratory failure, or life-threatening hemorrhage. At the same time, the recent growth spurt of palliative care programs across the country has made this resource available for specialty input in the care of ICU and other patients in most US hospitals [45]. Consultants on palliative care teams can provide valuable support to critical care clinicians in making family meetings happen. They can help to identify, contact, and assemble appropriate participants, coordinating schedules and making other arrangements. After preliminary discussions with the family, with the ICU team, and with consultants, they can assist in formulating an agenda and integrating information from multiple caregivers. Certification in palliative medicine (now recognized as a specialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties) and palliative nursing requires specific knowledge and training in skills for conducting a family meeting; for addressing emotional distress including depression, anxiety, and grief; and for maintaining continuity of care across different care settings. Palliative care specialists are also expert in relieving pain and discomfort for patients who are continuing to receive restorative treatments as well as for those from whom such treatments are withheld or withdrawn. Their role in ICU family meetings is undoubtedly an important explanation for the association of palliative care consultation with favorable ICU outcomes, including earlier identification of care goals and shorter stays in the ICU and hospital [8,46]. Where this resource is available, as in most US hospitals today, ICUs should therefore reach out to palliative care services for assistance in optimizing family meeting practices. The most effective strategy will be shaped by the integrative palliative care model, in which palliative care, including effective communication, is integrated early in the course of critical illness rather than only when patients are obviously or imminently dying [27,47].

3.11. Identify automatic triggers for family meetings

Identification of certain clinical situations as “automatic” triggers for a family meeting (with or without palliative care specialty input) is another approach that ICUs have used successfully. Lilly et al [9] demonstrated the effectiveness of a proactive process in which a formal family meeting was held within 72 hours of admission for patients predicted by the ICU attending physician to have a length of ICU stay longer than 5 days, a mortality risk greater than 25%, or a significant decline in functional status. As reported by Campbell and Guzman [8], efficient use of critical care resources was enhanced by palliative care consultation, which included assistance with family meetings, for all patients experiencing global cerebral ischemia after cardio-pulmonary resuscitation or multiple organ system failure for 3 days or more. Another successful program of proactive palliative care consultation targeted patients who were either admitted to the ICU after 10 or more days in the hospital, older than 80 years in the presence of 2 or more life-threatening comorbidities (eg, end-stage renal disease, severe congestive heart failure), diagnosed with active stage IV malignancy, status post cardiac arrest, or status post intracerebral hemorrhage requiring mechanical ventilation [46]. An alternative (or additional) strategy is to mandate a family meeting (or palliative care consultation) to address goals of care when selected procedures are under consideration—for example, tracheotomy for protracted ventilator dependence or feeding tube placement after a prolonged period of critical illness.

3.12. Relax restrictions on family presence in the ICU

Families want to be close to loved ones who are critically ill [48]. They want access to the ICU, for visiting and for participation in communications about patients. Patients themselves express that the presence of their family members is comforting and important [48]. Yet, most adult ICUs impose restrictions on family presence [49]. Although such restrictions may favor the efficient flow of work in certain circumstances and may be necessary when procedures are performed or emergencies arise, the benefits of more liberal access for families are increasingly recognized and the Institute for Healthcare Quality Improvement has encouraged relaxation of restrictions as a strategy for improving the quality of care [50]. Allowing families to spend more time in the ICU should make them more available for meetings at the convenience of clinicians, even on the shortest notice and at very early or late hours. Extended opportunities to observe the patient and the processes of care can also help families to understand issues that arise in family meetings, which may in turn make these meetings easier and faster. In addition, the caring and compassionate message that is conveyed by liberal access is likely to enhance trust, which in turn facilitates the process of communication. Although empirical evidence regarding this practice remains scant, it appears that an increasing number of ICUs are permitting families to be present even during daily patient care rounds. Others have experimented successfully with initiating daily “family rounds” as a separate process at a specific time each day [51]. Data indicate that this strategy is valued by families and enhances relationships and improves communication between families and physicians while also serving as a platform for educating trainees in communication skills [51]. At a minimum, an ICU with significant limitations on family visiting will want to reevaluate this policy as part an initiative to improve implementation of best practice with respect to family meetings.

3.13. Performance measurement, feedback, and improvement

As part of its national Transformation of the ICU (TICU) performance improvement initiative, the Voluntary Hospital Association, Inc (VHA) sponsored development of a “Care and Communication Bundle” of measures of ICU palliative care quality [15]. This bundle, which includes 9 “process measures” (ie, measures focusing on what caregivers do, as distinct from direct measurement of patient outcomes) and 1 “structural measure,” is now posted in full on the Web site of the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [52]. During the past 3 years, dozens of ICUs in the TICU program have implemented these measures along with other bundles of quality measures addressing different aspects of ICU practice. A key measure in the VHA Care and Communication Bundle quantifies the proportion of patients with documentation in the medical record that an interdisciplinary family meeting was conducted on or before day 5 of the ICU stay. For this purpose, a “family meeting” is defined in terms of topics under discussion: “A discussion addressing each of the following topics is recommended: (1) the patient’s condition (diagnosis and prognosis), (2) goals of treatment, (3) the patient’s and family’s needs and preferences (could address preparation of an advance directive, if not already done), (4) the patient’s and family’s understanding of the patient’s condition and goals of treatment at the conclusion of the meeting” [15]. A family meeting is defined as “interdisciplinary” if it “involved at least the attending physician (either primary attending or ICU attending), a member of another discipline (nurse, social worker, or pastoral care representative), and the patient (and/or family). Whenever possible, a nurse should be involved along with the physician” [15]. In the TICU program, performance on this measure is evaluated through retrospective review of medical records of patients who have been in the ICU for at least 5 days [15].

The ICUs in VHA’s TICU program have used a wide range of creative strategies to achieve high performance on the family meeting measure and others in the Care and Communication Bundle. They have also shared these strategies with each other, resulting in a highly successful synergy in the overall program. All such efforts were initiated, organized, and overseen by a Nurse Manager, but each of these nurses forged an early partnership with a “Physician Champion.” At the same time, many of these efforts enhanced the role of nursing staff in identifying communication needs and facilitating and documenting meetings between physicians and ICU families as well as other practices targeted by the measure set. All efforts began with a baseline evaluation of current performance on the family meeting measure—that is, review of a sample of medical records to determine the proportion of patients for whom a family meeting was held within the first 5 days in the ICU [15]. In each ICU, analysis of the baseline data called attention to opportunities for improvement and stimulated enthusiasm for further activities to achieve this goal. Thereafter, each of the ICUs convened a special interdisciplinary project team to identify and address barriers to optimal performance. Educational programs to address gaps in knowledge (eg, knowledge of legal and regulatory standards applying to withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies and to application of advance directives) were implemented. Project teams also focused attention of clinicians on key topics for discussion in family meetings. The ICUs developed new printed materials for families, including information that is specifically relevant for convening and conducting family meetings and defining the roles of various members of the health care team as they relate to the patient, family, and communication process. Many teams also focused on developing new tools for case finding and documentation that would streamline and optimize these processes. Restrictions on family visiting were reevaluated, and several teams found it helpful to liberalize these policies. The ICUs in institutions with palliative care teams called on these specialists to assist in the performance improvement effort. Departments of social work and hospital chaplaincy also played valuable roles. Some ICUs assigned case managers to facilitate arrangements for family meetings and to collect data on adherence to this practice. Ongoing, consistent reporting and feedback of performance to ICU team members has been an essential element of these initiatives.

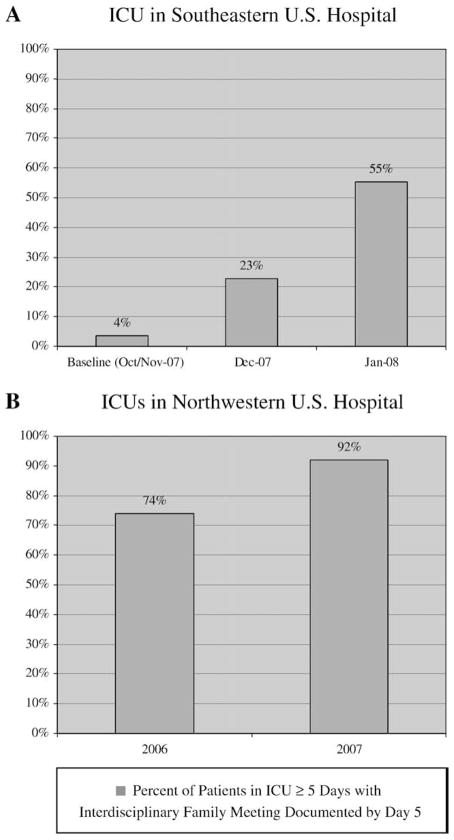

With well-defined and feasible goals, strong interdisciplinary commitment, and practical approaches like those we have reviewed in this article, ICUs in the VHA TICU program have achieved strikingly positive results even in a relatively short time (Fig. 1). The potential for rapid improvement with effective planning and implementation is seen in Fig. 1A, which shows impressive incremental improvements as early as the first several months after formal efforts to increase the frequency of family meetings were initiated in a 30-bed combined medical-surgical ICU in an 961-bed tertiary care hospital in the Southeastern United States. This ICU continues to improve performance. Fig. 1B presents before-and-after data from 3 ICUs (surgical, medical, and mixed medical-surgical) totaling 40 beds from a 369-bed tertiary care hospital in a state in the Northwest, where the Nurse Manager led a 1-year performance improvement initiative that increased the proportion of patients with documented family meetings by ICU day 5 from 74% to 92%. These results, which were accomplished without additional resources through leveraging of existing resources and programs, show that an ICU with respectable performance at baseline can still improve substantially. For all of these ICUs, an important target has been to decrease variability in practice while improving performance.

Fig. 1.

Results of initiatives in 2 different hospitals to improve ICU performance on the family meeting measure in the VHA Care and Communication Bundle of ICU Palliative Care Quality Measures [52]. This measure’s numerator is “number of patients who have documentation in the medical record that an interdisciplinary family meeting was conducted on or before day 5 of ICU admission,” and the denominator is “total number of patients with an ICU length of stay more than 5 days.” A. Improvement of performance during the first 4 months (October 2007–January 2008) of efforts in a 30-bed combined medical-surgical ICU in a Southeastern US 961-bed hospital. Data were collected through review of medical records for 129 patients with ICU length of stay 5 days or longer across 3 periods: October-November 2007 (n = 56), December 2007 (n = 35), and January 2008 (n = 38). B. Results of a 1-year (2006–2007) performance improvement initiative involving 3 ICUs (medical ICU, surgical ICU, mixed ICU) totaling 40 beds in a 359-bed hospital in the Northwest US. For collection of these data, medical records were reviewed for consecutive patients in defined periods during the second quarters of 2006 (n = 23) and 2007 (n = 50), respectively, with ICU length of stay 5 days or longer.

4. Conclusion

We have suggested a series of strategies that may be helpful in making family meetings happen in the ICU. Some of these strategies will be more appropriate for certain ICUs than for others, and all would require adaptation to the needs, resources, clinicians, and “culture” of a specific ICU; each ICU has its own “ecosystem,” and the environments of different ICUs can be vastly different, even within a single institution. In this article, we have focused on approaches to address some of the barriers that are commonly encountered across a range of ICUs based on the published literature, our own clinical and administrative experience, and our work with the VHATICU national initiative. We have emphasized approaches that are practical and straightforward. For the most part, these strategies can be accomplished with resources that are already available in or to the typical ICU. The ICUs seeking additional resources from the hospital may wish to present to hospital administrators the accumulating evidence that a proactive family meeting program can help to reduce ICU length of stay and may achieve other efficiencies in utilization of expensive resources, without increasing ICU mortality. We have summarized some of that information here, and the Center to Advance Palliative Care, www.capc.org, is a rich repository of additional information for this purpose. Whether new resources become available, we are optimistic that creative and committed ICUs can succeed in improving adherence to this important evidence-based practice.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the very creative and dedicated ICU professionals involved in the TICU Program of the VHA who have skillfully translated knowledge into practice and improved palliative and other care for critically ill patients and families. Dr Nelson is the recipient of a K02 Independent Scientist Research Career Development Award (AG024476) from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). This work was supported in part by R21 AG029955 from NIA. The VHA sponsored the development of the Care and Communication Bundle of ICU Palliative Care Quality Measures. Dr Nelson, Dr Pronovost, and Mr Bassett have served as Subject Matter Expert consultants for the VHA TICU Program. The VHA had no role in the conception or writing of this article, or in the collection of any data that are presented, or in the decision to prepare or submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr Nelson, Dr Pronovost, and Mr Bassett have served as Subject Matter Expert consultants for the Voluntary Hospital Association, Inc, Transformation of the ICU program, which sponsored the development of the Care and Communication Bundle of ICU Palliative Care Quality Measures.

Dr Gay has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Prendergast TJ, Luce JM. Increasing incidence of withholding and withdrawal of life support from the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:15–20. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, et al. The family conference as a focus to improve communication about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Opportunities for improvement. Crit Care Med. 2001;29 (Supp):N26–33. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickey M. What are the needs of families of critically ill patients? A review of the literature since 1976. HeartLung. 1990;19:401–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1679–85. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218409.58256.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, et al. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:844–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123:266–71. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109:469–75. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, et al. Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: results of a multiple center study. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1413–8. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbott KH, Sago JG, Breen CM, et al. Families looking back: one year after discussion of withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining support. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:197–201. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200101000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1893–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson JE, Angus DC, Weissfeld L, et al. End-of-life care for the critically Ill: A national ICU survey. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2547–53. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239233.63425.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. Half the families of ICU patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;8:3044–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, et al. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: A practical new tool for palliative care performance measurement and feedback. Qual Saf Healthcare. 2006;115:264–71. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teno JM, Fisher E, Hamel MB, et al. Decision-making and outcomes of prolonged ICU stays in seriously ill patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S70–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halpern NA, Pastores SM, Thaler HT, et al. Changes in critical care beds and occupancy in the United States 1985–2000: differences attributable to hospital size. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2105–12. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227174.30337.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1484–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, et al. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1722–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. [Accessed July 15, 2008]; www.dgim.pitt.edu/iepc/research_new.html.

- 21.Pham K, Thornton JD, Engelberg RA, et al. Alterations during medical interpretation of ICU family conferences that interfere with or enhance communication. Chest. 2008;134:109–16. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: An epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seravalli EP. The dying patient, the physician, and the fear of death. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1728–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson VA, Sullivan AM, Gadmer NM, et al. “It was haunting.”: physicians’ descriptions of emotionally powerful patient deaths. Acad Med. 2005;80:648–56. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:686–92. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:698–704. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson JE. Identifying and overcoming the barriers to high-quality palliative care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34 (Suppl):S324–31. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237249.39179.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching death: Improving care at the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press (Institute of Medicine); 1997. pp. 97–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the twenty-first century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. pp. 263–71. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:438–42. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. [Accessed July 15, 2008];Medicare Claims Processing Manual. Chapter 12 Section 30.6.12. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12/pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Critical care visits and neonatal intensive care. [Accessed July 15, 2008];CMS Bulletin. 2008 Jun 9; Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/Transmittals/downloads/R1350CP/pdf.

- 34.Hales BM, Pronovost PJ. The checklist—a tool for error management and performance improvement. J Crit Care. 2006;21:231–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Ngo K, et al. Developing and pilot testing quality indicators in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2003;18:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pronovost PJ, Holzmueller CJ, Martinez E, et al. A practical tool to learn from defects in patient care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:102–8. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Makary MA, Holzmueller CJ, Thompson D, et al. Operating room briefings: working on the same page. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:351–6. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Meeting the needs of intensive care unit patient families. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:135–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2005117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gries CJ, Curtis JR, Wall RJ, et al. Family member satisfaction with end-of-life decision making in the ICU. Chest. 2008;133:704–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wall RJ, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Refinement, scoring, and validation of the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit (FS-ICU) survey. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:271–9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251122.15053.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, et al. Efficacy of a cancer research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:650–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. [Accessed July 15, 2008]; www.epec.net.

- 43. [Accessed July 15, 2008]; www.aacn.nche.edu.

- 44.Ferrell BR, Dahlin C, Campbell ML, et al. End-of-life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) training program: improving palliative care in critical care. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2007;30:206–12. doi: 10.1097/01.CNQ.0000278920.37068.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldsmith B, Dietrich J, Du Q, et al. Variability in access to hospital palliative care in the United States. J Pall Med. 2008;11:1094–102. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–5. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nelson JE, Meier DE. Palliative care in the intensive care unit, part I. J Intensive Care Med. 1999;14:130–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson JE, Puntillo K, Penrod J, et al. Patients/families define ICU palliative care quality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:A517. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee MD, Freidenberg AS, Mukpo DH, et al. Visiting hours policy in New England intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:497–501. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254338.87182.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berwick DM, Kotagal M. Restricted visiting hours in ICUs: Time to change. JAMA. 2004;292:736–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mangram AJ, Mccauley T, Villarreal D, et al. Families’ perception of the value of timed daily “family rounds” in a trauma ICU. Am Surg. 2005;71:886–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. [Accessed July 15, 2008]; www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov.