Abstract

The prophenoloxidase subunit A3 (proPOA3) gene was cloned from Culex pipiens pallens, which had an open reading frame of 2,061 bp encoding a putative 686 amino acid protein. The deduced amino acid sequence shares 98% with proPOA3 from Cx. quinquefasciatus. ProPOA3 is expressed at all developmental stages of Cx. pipiens pallens. Significant negative correlation was observed between proPOA3 expression and deltamethrin resistance in resistant Cx. pipiens pallens. Furthermore, proPOA3 expression levels were significantly lower in deltamethrin-resistant mosquitoes than in susceptible mosquitoes collected at four locations in Eastern China. However, we did not find any substantial change in proPOA3 expression in field-collected resistant Anopheles mosquitoes. Moreover, overexpressing proPOA3 in C6/36 cells led to more sensitivity to deltamethrin treatment. In laboratory and field-collected resistant Cx. pipiens pallens, a valine to isoleucine mutation (769G>A) and two synonymous mutations (1116G>C and 1116G>A) were identified in proPOA3. In addition, the mutation frequency of 769G>A and 1116G>C increased gradually, which corresponded with raised deltamethrin resistance levels. Taken together, our study provides the first evidence that proPOA3 may play a role in the regulation of deltamethrin-resistance in Cx. pipiens pallens.

Keywords: Culex pipiens pallens, deltamethrin resistance, prophenoloxidase, mutation

1. Introduction

Insect-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, filariasis, chikungunya, and West Nile fever cause serious mortality and morbidity in humans, and pose significant threats to public health (Moreira et al. 2009). Among all applicable strategies, chemical control plays an important role in controlling disease-spreading vectors. As a fourth generation synthetic pyrethroid, deltamethrin blocks insect ion channels to cause a disruption to transmembrane potentials (Vais et al. 2001). It is commonly used in impregnating bed nets or as residual spray to control vectors (Curtis et al. 2003). Because of its high efficacy, rapid knockdown rate, and low mammalian toxicity, deltamethrin has been used extensively. Unfortunately, an excessive and continuous use of deltamethrin induced the development and spread of resistance, which presents the major obstacle in controlling arthropod-borne diseases.

The evolution of insecticide resistance is conferred through one or more possible mechanisms, typically requiring the interaction of multiple genes (Joussen et al. 2008). Using suppression subtractive hybridization and a microarray, previous studies by our group identified several differentially expressed genes between a deltamethrin-susceptible strain (DS-strain) and a deltamethrin-resistant strain (DR-strain) in Culex pipiens pallens (He et al. 2009; Tan et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2008). One of these genes, encoding prophenoloxidase subunit A3 (proPOA3), was found to be downregulated in DR-strain compared to DS-strain mosquitoes. Until now, however, the correlation between prophenoloxidase (proPO) gene expression and insecticide resistance and the underlying mechanisms were still unclear.

ProPO has multiple functions, including cuticular sclerotization, wound healing and pathogen or parasite defense in invertebrates (Cerenius and Soderhall 2004). In insect hemolymph, proPO is secreted as an inactive precursor and activated by serine proteinase cascade (Lee et al. 2000). There are nine proPO genes in Anopheles gambiae, ten in Aedes aegypti (Christophides et al. 2002; Waterhouse et al. 2007), and three in Cx. quinquefasciatus (Wang et al. 2011). Although previous findings strongly implied that proPO genes play an important role in arthropod immunity (Asada 1997; Mucklow et al. 2004), some studies speculated that proPO has specific physiological or cooperative functions, some of which are unknown (Zou et al. 2008). Therefore this study was designed to isolate and characterize the proPOA3 gene from Cx. pipiens pallens.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Mosquito strains and cell line

All laboratory mosquitoes were reared at 28 °C with 70–80% humidity and a constant light/dark cycle (14 h: 10 h). One laboratory-reared Cx. pipiens pallens population and ten field-collected mosquito populations (seven populations of Cx. pipiens pallens, one of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus, one of An. sinensis, and one of An. minimus) were used in this study (Table S1). For each field-collected mosquito population, mosquito larvae were brought back to the insectary after morphological identification and cohorts of 3-day old adult females were split into two groups using a modified bottle bioassay and insecticide susceptibility test. According to the bottle bioassay protocol (WHO, 1996), five batches of 25 non-blood fed females, three days post adult emergence, were exposed to 0.05% deltamethrin-impregnated papers for 1 h. Then, mosquitoes were transferred into insecticide-free tubes and maintained on 6% sucrose solution. Mortality was recorded after 24 h post exposure. For the insecticide susceptibility test, after 1 h exposure to 0.05% deltamethrin, the adult mosquitoes knocked down were recorded as DS-strain, and those not knocked down were recorded as DS-strain. All these mosquitoes were immediately processed for DNA isolation, or saved in RNAlater reagent (Ambion, USA) for future use. The laboratory colony was collected from Tangkou (Shandong province, China) and maintained for deltamethrin selection. We maintained three larval trays for each generation, about 1,000 larvae per tray. Before selection, the 50% lethal concentration (LC50) was determined by larval bioassay, and used as the select concentration. Three hundred fourth-instar larvae, divided into five groups, were exposed to five different concentrations of deltamethrin for 24 h. Another 60 fourth-instar larvae without treatment were used as control. For each group, larvae were divided into three replicates (Chen et al. 2010). The experiment was carried out at 28°C under approximately 14 h: 10 h light/dark cycle. Dead and surviving mosquitoes were recorded after 24 h, and Probit analysis was used to calculate LC50. In total, 28 generations of selected adult mosquitoes were reared, with an LC50 for the 28th generation of 0.74 ppm deltamethrin. Ae. albopictus C6/36 cells were purchased from the China Center for Type Culture Collection (Wuhan, China). Cells were cultured in DMEM/high glucose media (Invitrogen, USA), containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, USA) in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator at 28 °C.

2.2 RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Adult mosquitoes of field-collected and laboratory-reared mosquito populations and the Ae. albopictus C6/36 cell line were used. All mosquitoes had emerged for three days and were fed on glucose. Total RNA was extracted from mosquitoes using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The purity of the total RNA extracted was determined by spectrophotometer. RNA samples with an absorbance ratio at OD260/280 between 1.9 and 2.2 were used for further analysis. RNA integrity was also verified by 1 % agarose gel electrophoresis and samples without smears were used for the following experiment. The cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.3 Cloning and sequencing

The open reading frame (ORF) of proPOA3 was amplified using a pair of specific primers: forward primer: 5′-ATGGTGTCCAACCAGACGCGTTTTTCC-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-CTATGTTCTAGCGATGACGGT-3′, which were designed based on the homology alignment of Cx. quinquefasciatus phenoloxidase subunit A3 (GenBank accession No. XM_001867378.1). PCR reactions were carried out using an Ex taq kit (TaKaRa, Japan) following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

The amplification of 3′-cDNA ends (3′-RACE) and 5′-cDNA ends (5′-RACE) of proPOA3 were carried out using a SMART™ RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech, USA). The specific primer sequences for 3′-RACE and 5′-RACE were: 5′-GTGGCACTGCTTCACAGGAGGGACA-3′ and 5′-CCCGTGAAAACGCAGCAAA CGAAGC-3′, respectively. The sequences of 3′-RACE and 5′-RACE adaptor primers supplied by the SMART™RACE cDNA Amplification Kit were: 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′ and 5′-CTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT-3′, respectively. The touchdown PCR conditions were set as follows: five cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 72°C for 3 min, followed by five cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 70 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 3 min, and 27 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 3 min. The PCR products were separated by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and purified using a QIA quick Gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany). The PCR fragments were ligated into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega, USA), and the ligation mixture was transformed into DH5α competent cells and selected with IPTG and X-Gal for proPOA3-positive samples, which were sent for sequencing (Invitrogen Biotechnology Co, Shanghai, China). Finally, all sequences were assembled to generate a putative full-length cDNA library of proPOA3.

2.4 Sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree reconstruction

The standard protein-/protein BLAST sequence comparison program (http://beta.uniprot.org/?tab=blast) was used to search for sequences in the SWISSPROT databases with similarities to the translated sequences of proPO genes. Deduced amino acid sequences were aligned using the ClustalW2 program (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html). A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the ClustalW2 program using the neighbor-joining method. A total of 100 bootstrap analyses were performed for the phylogenetic analysis.

2.5 Quantitative PCR analysis

Quantitative PCR was performed on the ABI PRISM 7300 (Applied Biosystems, USA) using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each reaction was performed in 20 μL volume containing Power SYBR Green PCR Master mix, specific forward and reverse primers, and diluted cDNA. Primers of proPOA3 and β-actin used here are listed in Table S2. The PCR conditions were set as following: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min. A melting curve program was run immediately after the PCR program and the data were analyzed with 7300 System SDS Software v1.2.1 (Applied Biosystems, USA). Both melting curve and gel electrophoresis analysis of the amplification products were applied to confirm that the primers amplified only a single product of expected size. In addition, the PCR products were also sequenced for confirmation. The raw threshold cycle (Ct) values were normalized against β-actin standard to obtain normalized Ct values, which were then used to calculate relative expression levels using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Developmental stage-specific expression of proPOA3 in Cx. pipiens pallens was determined by quantitative PCR. The samples include eggs, L1–L4 larvae, pupae and adults from laboratory DS-strain and DR-strain mosquitoes. The LC50 of these two strains for deltamethrin were 0.02 ppm and 0.74 ppm, respectively. The expression level of proPOA3 in eggs of the DS-strain was considered as 1. The experiment was repeated three times using independently purified cDNA samples.

The laboratory-reared Cx. pipiens pallens population subjected to deltamethrin selection was used to determine proPOA3 expression levels. Five generations (G0, G8, G14, G22, and G28) were chosen in this study, with the corresponding LC50 values at 0.02 ppm, 0.10 ppm, 0.31 ppm, 0.48 ppm and 0.74 ppm, respectively. Sixty randomly selected female adult mosquitoes per each generation were used for proPOA3 expression analysis.

Field-collected populations of Cx. pipiens pallens, Cx. tritaeniorhynchus, An. sinensis, and An. minimus were used to detect expression of proPOA3. All female adult mosquito populations were divided into DR-strain and DS-strain by insecticide susceptibility test. A quantitative PCR assay was repeated three times in independent experiments, with three replicates for each sample.

2.6 Construction of the eukaryotic expression plasmid

The entire ORF of proPOA3 was constructed into the eukaryotic pIB/V5-His expression vector (Invitrogen, USA). The ORF of proPOA3 was amplified using a pair of specific primers: forward primer: 5′-CGGGATCCGAGATGGAAATGGTGTCCA ACCAGACGCGTTTTTCC-3′, which harbored a BamHI recognition site (GGATCC, shown in bold); reverse primer: 5′-GCTCTAGATGTTCTAGCGATGACGGT-CTTC-3′, which contained an XbaI recognition site (TCTAGA, shown in bold). A Kozak sequence (GAGATGG) was inserted just before the starting codon ATG and two additional AA were added to avoid frame shift mutation (Kozak 1986; Sano et al. 2002). The stop codon TAG was removed and ligated with a His tag to generate a fusion gene. The fused gene was ligated into a vector through BamHI and XbaI digestion. Positive clones were verified by PCR and sequencing.

2.7 Transient transfection and cellular viability analysis

C6/36 cells (8,000 cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate, which was pre-incubated in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator at 28 °C overnight. Transfection was performed using FuGENE® HD transfection reagent (Roche, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 0.125 μg diluted pIB/V5-His-proPOA3 or pIB/V5-His (as control) plasmids and 0.35 μL transfection reagent were added to 50 μL serum-free MEM separately, and the solutions were mixed gently and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, the mixture was layered onto serum-free MEM washed cells. Six hours after transfection, cells were changed into complete medium. Twenty-four hours later, cells were treated with various concentrations of deltamethrin ranging from 0 to 102 μg/mL in a final volume of 200 μL. Deltamethrin was dissolved in DMSO (0.1%, v/v) (Sigma, USA). Plates were incubated for 68 h, and 10 μL of CCK-8 (Dojindo, Japan) solution was added to each well. Four hours later, the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Biotek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

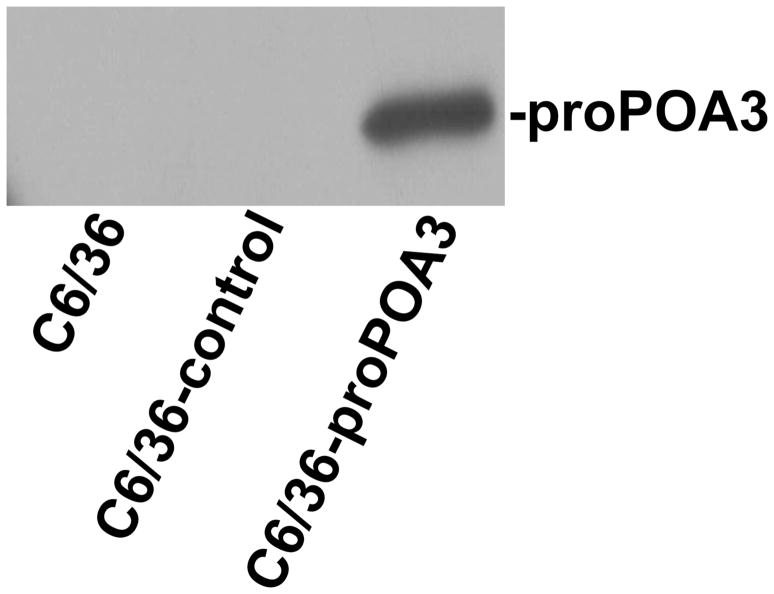

To confirm transfection and expression efficiency of exogenous proPOA3, a western blotting analysis was also conducted. Protein was extracted from C6/36, C6/36-proPOA3 and C6/36-control cells. A 10% SDS-PAGE was performed for 20 min at 80 V and for 120 min at 100 V. The proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane at 350 mA for 70 min with Trans-Blot SD Cell and Systems (Bio-Rad, USA). The fusion protein was detected using an anti-his monoclonal antibody (1:500, Abmart, China) and a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:2000, Beyotime, China). Detection was carried out with a BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8 Detection of proPOA3 mutations by sequencing

The mutations in proPOA3 were first screened in deltamethrin-selected laboratory-reared Cx. pipiens pallens mosquitoes. A total of 300 female adult mosquitoes from five generations (G0, G6, G16, G22 and G28) were used for the PCR assay. Genomic DNA was extracted from individual mosquitoes as previously described (Collins et al. 1987). The forward primer 5′-ATGGTGTCCAACCAGACGCGTTTTTCC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CTATGTTCTAGCGATGACGGT-3′ were used for amplification of the ORF and intron regions. The PCR reaction was carried out using KOD-Plus-Neo kit (TOYOBO, Japan) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. PCR products were purified and sequenced. Furthermore, five field-collected Cx. pipiens pallens populations (from Qingdao, Weishan, Wuxi, Nanjing, Huaibei) were used in this test. All populations were divided into DR-strain and DS-strain by insecticide susceptibility test before PCR analysis. Two pairs of primers were designed to amplify fragments of proPOA3 containing the mutations (Table S3).

2.9 Statistical analysis

Calculations were performed using Stata (Version 7.0, StataCorp, LP). All hypothesis testing was two-sided, with a P value < 0.05 considered significant. The frequency of mutations was calculated, and the statistical difference among populations was examined using Student’s t-test. Linear regression analysis was used to correlate transcription level or frequency of mutation and deltamethrin resistance level (LC50) in Cx. pipiens pallens.

3. Results

3.1 Cloning the full-length cDNA of proPOA3 gene

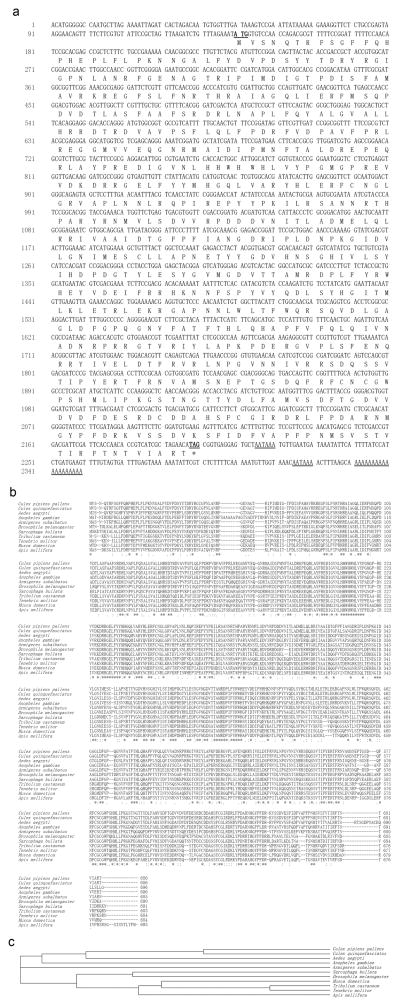

The full length of proPOA3 gene, amplified from Cx. pipiens pallens, contains 2,349 base pairs (bp), while the ORF region of proPOA3 has 2,061 bp and encodes for a protein with 686 amino acids (GenBank Accession No: FJ755838.1). The start codon ATG was found at position 140–142 and an in-frame stop codon TAG was located at position 2198–2200 with the tailing signal sequence “AATAAA” and poly (A) presenting at the 3′-untranslated region (Fig. 1a). The deduced amino acid sequence showed high similarity with Cx. pipiens pallens proPOA3 and proPOs from other insects when analyzed by ClustalW2 software, which indicated that proPOs are conserved between species (Fig. 1b). Phylogenetic relationships by the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei 1987) showed that proPOA3 of Cx. pipiens pallens shared the highest homology with Cx. quinquefasciatus (98% identity) (Fig. 1c). Structure analysis using the CDD software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) showed that the putative protein contains three domains: Hemocyanin_N domain (all-alpha domain) from position 78 to 142, Hemocyanin_M domain (copper containing domain, active domain) from position 149 to 413, and Hemocyanin_C domain (Ig-like domain) from position 421 to 679.

Fig. 1.

(a) The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of proPOA3 in Cx. pipiens pallens. The deduced amino acid sequence is presented below the nucleotide sequence in single letter code. The initial code “ATG” and the termination codon “TAG” are denoted in bold italic letters and underlined. The asterisk denotes the stop codon. The tailing signal sequence “AATAAA” and poly (A) in the 3′-untranslated region are underlined. (b) Amino acid alignment of proPOA3 in Cx. pipiens pallens and prophenoloxidase in other species. Asterisks indicate identical amino acid and dots indicate similar amino acids. (c) Phylogenetic relationships of proPOA3 in Cx. pipiens pallens and prophenoloxidase in other species. Species name and GenBank Accession Nos.: Cx. pipiens pallens: >gi|224999309; Cx. quinquefasciatus: >gi|170064165; Ae. aegypti: >gi|157136174; An. gambiae: >gi|20803449; Armigeres subalbatus: >gi|40557564; Drosophila melanogaster: >gi|17136630; Sarcophaga bullata: >gi|5579390; Tribolium castaneum: >gi|86515394; Tenebrio molitor: gi|4514633; Musca domestica: >gi|40362984; Apis mellifera: >gi|58585196.

3.2 Quantitative PCR analysis

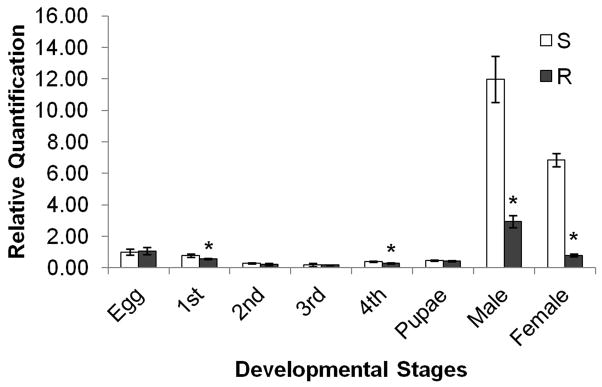

The proPOA3 gene is transcribed at all developmental stages of Cx. pipiens pallens (Fig. 2). Transcription levels of proPOA3 were relatively low in eggs, L1–L4 larvae and the pupal stage, but drastically increased in the adult stage. Transcription levels of proPOA3 were higher in male than female adults in both strains (P < 0.05). Comparison between the DS-strain and the DR-strain indicated no significant differences in proPOA3 transcription in eggs, L2 and L3 larvae, and pupae. In the DS-strain, the transcription of proPOA3 was slightly increased in L1 and L4 larvae (1.36-fold and 1.30-fold, respectively, P < 0.05), and significantly increased in male (4.08-fold, P < 0.05) and female adults (8.63-fold, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Quantitative PCR analysis of Cx. pipiens pallens proPOA3 transcripts at several developmental stages. The expression level of proPOA3 in susceptible strain eggs was considered as 1. These data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) of three independent experiments. S: deltamethrin-susceptible strain; R: deltamethrin-resistant strain. * P < 0.05 compared with deltamethrin-susceptible strain.

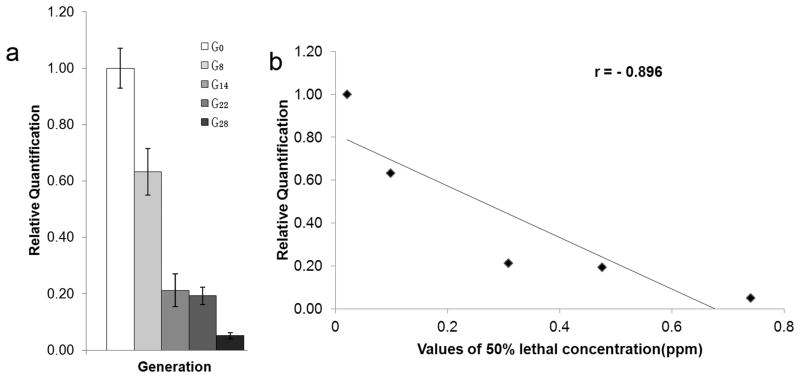

Laboratory-reared Cx. pipiens pallens populations with various resistance levels were then used for proPOA3 transcription analysis. Fig. 3a shows that transcriptional expression of proPOA3 significantly decreased during deltamethrin selection. After 28 generations of deltamethrin selection, the LC50 was increased 36.29 fold, whereas the proPOA3 transcriptional expression was decreased by 95%. Regression analysis found a significant negative correlation between the proPOA3 transcriptional expression and the LC50 of deltamethrin (r = −0.896, P < 0.05, Fig. 3b). Interestingly, from G0 to G14, the LC50 value was increased by 0.29 ppm, while a rapid decrease of the proPOA3 transcriptional expression was observed (78.77% downregulation). In the subsequent 14 generations (G14 to G28), the LC50 value was increased by 0.43 ppm, while the proPOA3 transcriptional expression was only slightly decreased (16.06% downregulation). This suggests that the decrease of proPOA3 transcriptional expression seemed to precede the increase in deltamethrin resistance.

Fig. 3.

(a) Quantitative PCR analysis of Cx. pipiens pallens proPOA3 transcripts in five mosquito generations (G0, G8, G14, G22 and G28) after deltamethrin selection. The 50% lethal concentrations (LC50) value at G0, G8, G14, G22, G28 were 0.020 ppm, 0.10 ppm, 0.31 ppm, 0.48 ppm and 0.74 ppm, respectively. These data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) of three independent experiments. (b) Relationship between proPOA3 transcriptional levels and deltamethrin resistance (LC50) of C. pipiens pallens.

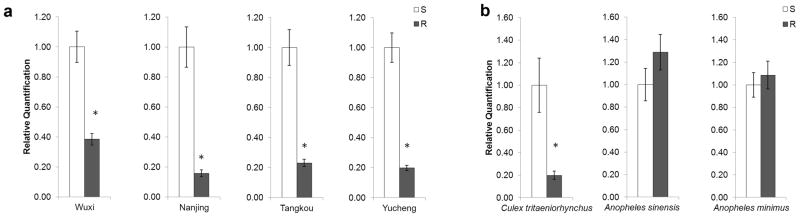

The proPOA3 differential transcriptional expression was also analyzed in field-collected Cx. pipiens pallens populations. Fig. 4a showed that the expression levels of proPOA3 were significantly higher in the DS-strain than the DR-strain in four different regions of mainland China (2.60-fold in Wuxi, 6.33-fold in Nanjing 4.33-fold in Tangkou, and 5.02-fold in Yucheng, respectively, P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

(a) Quantitative PCR analysis of Cx. pipiens pallens proPOA3 transcripts in three field-collected mosquito populations from Wuxi, Nanjin, Tangkou and Yucheng. These data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) of three independent experiments. (b) Quantitative PCR analysis of proPOA3 transcripts in other mosquito species (Cx. Tritaeniorhynchus, An. sinensis, An. minimus). Data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) of three independent experiments. S: the deltamethrin susceptible individuals; R: deltamethrin-resistant individuals. * P < 0.05 compared to deltamethrin-susceptible strain.

To determine whether decreased proPOA3 transcription was associated with deltamethrin resistance in other mosquito species, expression levels between susceptible and resistant strains of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus, An. sinensis and An. minimus were also evaluated. Fig. 4b shows that the transcriptional level of proPOA3 was 5.03-fold higher in the DS-strain of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus compared with the DR-strain (P < 0.05), which was similar to the results found in Cx. pipiens pallens. However, the transcriptional expression of proPOA3 showed no significant differences between the susceptible and the resistant individuals in Anopheles species (P > 0.05).

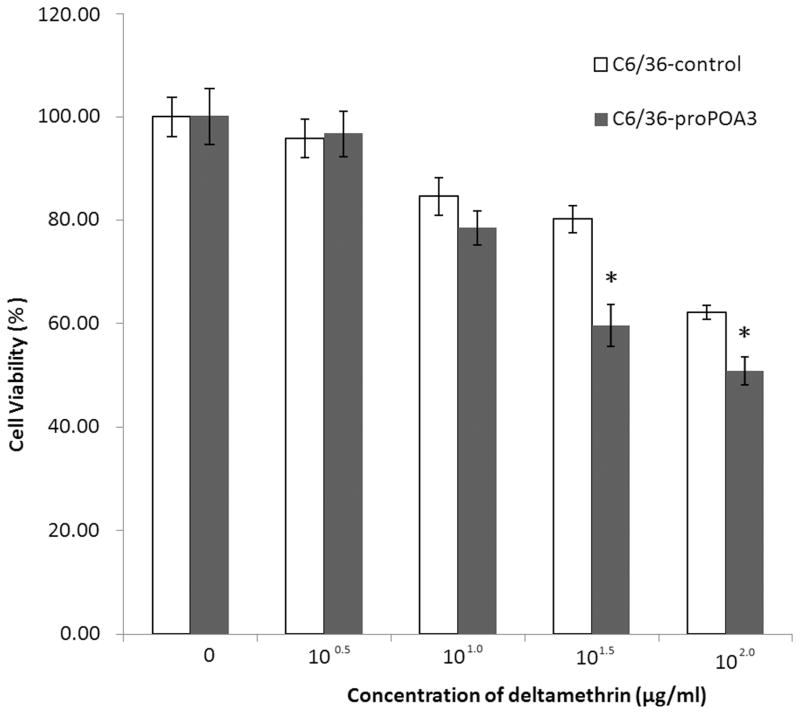

3.3 Deltamethrin sensitivity analysis of proPOA3-overexpressing C6/36 cells

To further investigate the mechanisms of proPOA3 involved in deltamethrin resistance, a C6/36 cell line transiently transfected with pIB/V5-His-proPOA3 and pIB/V5-His control was used. Western blotting analysis using anti-His antibodies identified a protein of around 85 kDa with pIB/V5-His-proPOA3 transfection (Fig. S1), confirming that the exogenous fusion protein proPOA3-his was successfully synthesized in C6/36 cells. The dose response of cell viability over a wide range of concentrations (0, 100.5 μg/mL, 101.0 μg/mL, 101.5 μg/mL, and 102.0 μg/mL) of deltamethrin was measured based on a cytotoxicity assay using CCK-8 kit. The viability of C6/36-proPOA3 and C6/36-control cells both decreased with increased deltamethrin dosage as expected (Fig. 5). The decreased viability in C6/36-proPOA3 cells compared to controls under high dosage deltamethrin treatment (101.5 and 102.0 μg/mL) suggested that proPOA3 overexpression might sensitize C6/36 cells to deltamethrin treatment.

Fig. 5.

Overexpressed proPOA3 leads to an increased susceptibility to deltamethrin in C6/36 cells. C6/36-proPOA3 and C6/36-control cells were treated with deltamethrin at the indicated concentrations, and viable cells were measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. In each group, the percentage of viable cells is shown relative to the absorbance value of 0 μg/mL. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from one representative experiment out of three. * P < 0.05 compared to C6/36-control. The experiment was repeated three times and showed the same pattern.

3.4 Distribution of mutation proPOA3 associated with deltamethrin resistance

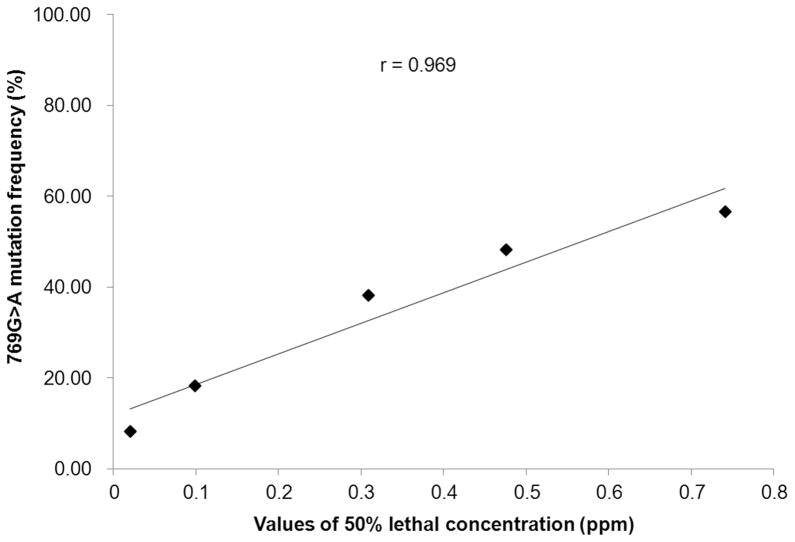

A sequence analysis of proPOA3 genes was carried out in laboratory-reared deltamethrin-selected Cx. pipiens pallens. Three point mutations were found at the 769th and 1116th base, which were both located in the exon region of proPOA3. The non-synonymous point mutation (769G>A) resulted in a switch from valine to isoleucine, whereas two other mutations (1116G>C and 1116G>A) were synonymous. Interestingly, the 769G>A and 1116G>C mutations could be detected simultaneously, which means that when homozygous mutation (G/G→A/A)/heterozygous mutation (G/G→G/A) occurred at the 769th base, a homozygous mutation (G/G→C/C)/heterozygous mutation (G/G→G/C) at the 1116th base could also be detected. Thus, five genotypes could be detected: (769G/G + 1116G/G), (769G/A + 1116G/C), (769A/A + 1116C/C), (769G/G + 1116G/A), and (769G/G + 1116A/A). Under deltamethrin selection, the frequency of the wild type allele (769G/G + 1116G/G) decreased from 85.00% to 43.33% after 28 generation selection (P < 0.05), whereas the frequency of 769G>A (1116G>C) was significantly increased from 8.34% to 56.67% (P < 0.05) (Table 1). A significant positive correlation between the 769G>A (1116G>C) mutation frequency and the LC50 of deltamethrin in Cx. pipiens pallens was found using a regression analysis (r = 0.969, P < 0.05, Fig. 6). The mutation 1116G>A on the other hand disappeared after 14 generations of deltamethrin selection. These results suggest that the frequencies of the mutations 769G>A and 1116G>C increased with raised levels of deltamethrin resistance in Cx. pipiens pallens populations.

Table 1.

Frequencies of proPOA3 mutations in Cx. pipiens pallens populations after deltamethrin selection.

| Population | LC50 | Sample size (n) | Wild type (769G/G+1116G/G) | Mutations

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 769G>A (G/A) | 769G>A (A/A) | 1116G>A (G/A) | 1116G>A (A/A) | ||||

| G0 (Parental) | 0.0204 | 60 | 51 (85.00%) | 4 (6.67%) | 1 (1.67%) | 1 (1.67%) | 3 (5.00%) |

| G8 | 0.0985 | 60 | 46 (76.67%) | 9 (15.00%) | 2 (3.33%) | 1 (1.67%) | 2 (3.33%) |

| G14 | 0.3088 | 60 | 37 (61.67%) | 19 (31.67%) | 4 (6.67%) | 0 | 0 |

| G22 | 0.4758 | 60 | 31 (51.67%) | 25 (41.67%) | 4 (6.67%) | 0 | 0 |

| G28 | 0.7403 | 60 | 26 (43.33%) | 28 (46.67%) | 6 (10.00%) | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 6.

Relationship between the frequency of 769G>A mutation and LC50 of deltamethrin treatment in C. pipiens pallens.

We also performed a nucleotide diversity analysis in field-collected Cx. pipiens pallens populations. The homozygous or heterozygous mutations 769G>A and 1116G>C also occurred simultaneously. Table 2 summarizes the frequencies of 769G>A (1116G>C) and 1116G>A in mosquitoes from five different locations. The mutation 769G>A (1116G>C) was mostly detected in resistant individuals from Qingdao (42.85%), Weishan (11.54%), and Nanjing (23.92%) populations. The 1116G>A mutation was detected both in resistant (13.64%) and susceptible (9.52%) individuals from Wuxi. However, neither mutation was detected in resistant or susceptible individuals from Huaibei populations. These data confirmed that the frequencies of the mutations 769G>A and 1116G>C, but not of 1116G>A were higher in resistant mosquitoes than in susceptible field-collected Cx. pipiens pallens mosquitoes. However, the emergence of 769G>A and 1116G>C mutations is restricted to some regions only.

Table 2.

Frequencies of proPOA3 mutations in five field-collected Cx. pipiens pallens populations from East China.

| Population | Phenotype | Sample size (n) | Wild type (769G/G+1116G/G) | Mutations

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 769G>A (G/A) | 769G>A (A/A) | 1116G>A (G/A) | 1116G>A (A/A) | ||||

| Qingdao | Resistant | 35 | 20 (57.14%) | 9 (25.71%) | 6 (17.14%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 18 | 17 (94.44%) | 1 (5.56%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Weishan | Resistant | 26 | 23 (88.46%) | 1 (3.85%) | 2 (7.69%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 36 | 36 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nanjing | Resistant | 46 | 35 (76.09%) | 9 (19.57%) | 2 (4.35%) | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 23 | 42 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Wuxi | Resistant | 22 | 19 (86.36%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (13.64%) |

| Susceptible | 42 | 38 (90.48%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (9.52%) | |

| Huaibei | Resistant | 27 | 27 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Susceptible | 21 | 21 (100%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

4. Discussion

In the present study, we isolated and characterized the proPOA3 gene from Cx. pipiens pallens. The gene was expressed in all developmental stages of Cx. pipiens pallens. The expression of proPOA3 in the DR-strain was slightly decreased in the larval stage, and dropped drastically in the adult stages compared to the DS-strain. Furthermore, the decrease of proPOA3 transcriptional level corresponded with increased deltamethrin-resistance in the laboratory-reared deltamethrin-selected population. Moreover, the decreased proPOA3 transcriptional levels were consistently detected in bottle bioassay survivals in four field-collected Culex populations from Eastern China. In addition, overexpressed proPOA3 in C6/36 cell resulted in decreased deltamethrin resistance. Taken together, these results indicated that proPOA3 might play a role in resistance to deltamethrin in Culex mosquitoes. Insecticide resistance, which is assumed to be a pre-adaptive phenomenon, involves multiple resistance mechanisms or genes (Cohuet et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2007). Typically, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s), esterases, glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs), and target site insensitivity are known to be responsible for deltamethrin resistance in mosquitoes (Li et al. 2007). Our previous studies also found a definitive link between resistance and other genes not belonging to these families. These genes, including those for myosin regulatory light chain (MRLC) (Yang et al. 2008), glycogen branching enzyme (GBE) (Xu et al. 2008) and ribosomal protein L39 (RPL39) (Tan et al. 2007), play an important roles in other physiological processes before being characterized as insecticide resistant-associated genes. The phenoloxidase (PO) family varies among mosquito species (Christophides et al., 2002; Waterhouse et al., 2007), indicating that its members have diverse functions. Here, we propose that proPOA3 not only plays an important role in immune defense, but could also be involved in insecticide resistance. The correlation between the expression of proPOA3 and deltamethrin resistance levels suggests that proPOA3 could be an insecticide-resistant associated gene

Insecticide-resistant insects have reduced levels of fitness in an insecticide-free environment, which is commonly known as fitness cost of resistance (Shi et al. 2004). This fitness cost includes decreased adult longevity, preimaginal survival and fecundity (Agnew et al. 2004; Berticat et al. 2008), which may be results of gene variations, metabolic equilibrium disruption, or other mechanisms (Berticat et al. 2008). POs act as important enzymes in arthropod immune systems and have been assessed in several experimental studies (Schwarzenbach et al. 2005). However, maintaining an active immune system is costly for insects (Schmid-Hempel 2005). Schwarzenbach and Ward found that high-PO yellow dung flies died earlier than low-PO flies when no food was available (Schwarzenbach and Ward 2006). Therefore, the reduced proPOA3 expression in DR-strain mosquitoes may be partially explained as the fitness cost of insecticide resistance.

Here, we found that transcriptional levels of ProPOA3 were lower in deltamethrin-resistant than in susceptible Culex mosquitoes, but no significant difference was detected in An. sinensis and An. minimus, which suggests that proPOA3 may only be involved in deltamethrin resistance in Culex, but not in Anopheles species. It has been reported that highly deltamethrin-resistant Cx. pipiens pallens strains could be easily obtained in laboratory by deltamethrin selection, while An. sinensis failed to exhibit higher resistance to deltamethrin, indicating that the mechanism of insecticide-resistance occurrence and development varied between species (Zhou et al. 2001). We speculate that proPOA3 might only be involved in insecticide resistance in mosquito species that can rapidly develop higher resistance, such as Cx. pipiens pallens. Furthermore, this species-specific role of proPOA3 may also be a result of long-term adaptive evolution of species to other aspects, such as the region, environment, or susceptible pathogens. More experiments are required to fully elucidate this question.

By using sequence analysis, the non-synonymous point mutation 769G>A and the synonymous point mutation 1116G>C were found to be involved in deltamethrin resistance. Conserved domain analysis showed that both mutations exist in the hemocyanin_M domain (copper-containing domain) of proPOA3. The copper-containing domain is the active site of proPO, in which dioxygen bridges two copper atoms in a side-on configuration (Decker and Terwilliger 2000). The non-synonymous point mutation 769G>A resulted in a switch from valine to isoleucine, which could lead to changes in the physico-chemical property and may help the development of deltamethrin resistance. Here, we found that 769G>A and 1116G>C have a restricted regional limitation (these two mutations were not detected in field-collected mosquitoes from Wuxi and Huaibei), which can be partially explained by history (the mutations need longer time to spread), selection (advantage and fitness cost vary among alleles), random de novo mutations, or gene flow (imported by active or passive migration from other areas). Among the mutations, we did not find a strong correlation between the 1116G>A mutant and deltamethrin-resistance, and this correlation disappeared early on in the trial. It needs to be further studied whether this is a random mutation or whether it is induced by other mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health of US (R01 AI075746), the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2008ZX10004-010) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 30972564 and 30901244).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agnew P, Berticat C, Bedhomme S, Sidobre C, Michalakis Y. Parasitism increases and decreases the costs of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes. Evolution. 2004;58:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada N. Genetic variants affecting phenoloxidase activity in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem Genet. 1997;35:41–49. doi: 10.1023/a:1022208529461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berticat C, Bonnet J, Duchon S, Agnew P, Weill M, Corbel V. Costs and benefits of multiple resistance to insecticides for Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerenius L, Soderhall K. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:116–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Zhong D, Zhang D, Shi L, Zhou G, Gong M, Zhou H, Sun Y, Ma L, He J, Hong S, Zhou D, Xiong C, Chen C, Zou P, Zhu C, Yan G. Molecular ecology of pyrethroid knockdown resistance in Culex pipiens pallens mosquitoes. Plos one. 2010;5:e11681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophides GK, Zdobnov E, Barillas-Mury C, Birney E, Blandin S, Blass C, Brey PT, Collins FH, Danielli A, Dimopoulos G, Hetru C, Hoa NT, Hoffmann JA, Kanzok SM, Letunic I, Levashina EA, Loukeris TG, Lycett G, Meister S, Michel K, Moita LF, Muller HM, Osta MA, Paskewitz SM, Reichhart JM, Rzhetsky A, Troxler L, Vernick KD, Vlachou D, Volz J, von Mering C, Xu J, Zheng L, Bork P, Kafatos FC. Immunity-related genes and gene families in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298:159–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1077136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohuet A, Krishnakumar S, Simard F, Morlais I, Koutsos A, Fontenille D, Mindrinos M, Kafatos FC. SNP discovery and molecular evolution in Anopheles gambiae, with special emphasis on innate immune system. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:227. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins FH, Mendez MA, Rasmussen MO, Mehaffey PC, Besansky NJ, Finnerty V. A ribosomal RNA gene probe differentiates member species of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;37:37–41. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.37.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis CF, Jana-Kara B, Maxwell CA. Insecticide treated nets: impact on vector populations and relevance of initial intensity of transmission and pyrethroid resistance. J Vector Borne Dis. 2003;40:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker H, Terwilliger N. Cops and robbers: putative evolution of copper oxygen-binding proteins. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:1777–1782. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.12.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Sun H, Zhang D, Sun Y, Ma L, Chen L, Liu Z, Xiong C, Yan G, Zhu C. Cloning and characterization of 60S ribosomal protein L22 (RPL22) from Culex pipiens pallens. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;153:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussen N, Heckel DG, Haas M, Schuphan I, Schmidt B. Metabolism of imidacloprid and DDT by P450 CYP6G1 expressed in cell cultures of Nicotiana tabacum suggests detoxification of these insecticides in Cyp6g1-overexpressing strains of Drosophila melanogaster, leading to resistance. Pest Manag Sci. 2008;64:65–73. doi: 10.1002/ps.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Wang R, Soderhall K. A lipopolysaccharide- and beta-1,3-glucan-binding protein from hemocytes of the freshwater crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus. Purification, characterization, and cDNA cloning. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1337–1343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic resistance to synthetic and natural xenobiotics. Annu Rev Entomol. 2007;52:231–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Liu H, Zhu F, Zhang L. Differential expression of genes in pyrethroid resistant and susceptible mosquitoes, Culex quinquefasciatus (S.) Gene. 2007;394:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira LA, Saig E, Turley AP, Ribeiro JM, O’Neill SL, McGraw EA. Human probing behavior of Aedes aegypti when infected with a life-shortening strain of Wolbachia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucklow PT, Vizoso DB, Jensen KH, Refardt D, Ebert D. Variation in phenoloxidase activity and its relation to parasite resistance within and between populations of Daphnia magna. Proc Biol Sci. 2004;271:1175–1183. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano K, Maeda K, Oki M, Maeda Y. Enhancement of protein expression in insect cells by a lobster tropomyosin cDNA leader sequence. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03659-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid-Hempel P. Evolutionary ecology of insect immune defenses. Annu Rev Entomol. 2005;50:529–551. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.50.071803.130420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbach GA, Hosken DJ, Ward PI. Sex and immunity in the yellow dung fly Scathophaga stercoraria. J Evol Biol. 2005;18:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbach GA, Ward PI. Responses to selection on phenoloxidase activity in yellow dung flies. Evolution. 2006;60:1612–1621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi MA, Lougarre A, Alies C, Fremaux I, Tang ZH, Stojan J, Fournier D. Acetylcholinesterase alterations reveal the fitness cost of mutations conferring insecticide resistance. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W, Sun L, Zhang D, Sun J, Qian J, Hu X, Wang W, Sun Y, Ma L, Zhu C. Cloning and overexpression of ribosomal protein L39 gene from deltamethrin-resistant Culex pipiens pallens. Exp Parasitol. 2007;115:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vais H, Williamson MS, Devonshire AL, Usherwood PN. The molecular interactions of pyrethroid insecticides with insect and mammalian sodium channels. Pest Manag Sci. 2001;57:877–888. doi: 10.1002/ps.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Lu A, Li X, Shao Q, Beerntsen BT, Liu C, Ma Y, Huang Y, Zhu H, Ling E. A systematic study on hemocyte identification and plasma prophenoloxidase from Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus at different developmental stages. Exp Parasitol. 2011;127:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse RM, Kriventseva EV, Meister S, Xi Z, Alvarez KS, Bartholomay LC, Barillas-Mury C, Bian G, Blandin S, Christensen BM, Dong Y, Jiang H, Kanost MR, Koutsos AC, Levashina EA, Li J, Ligoxygakis P, Maccallum RM, Mayhew GF, Mendes A, Michel K, Osta MA, Paskewitz S, Shin SW, Vlachou D, Wang L, Wei W, Zheng L, Zou Z, Severson DW, Raikhel AS, Kafatos FC, Dimopoulos G, Zdobnov EM, Christophides GK. Evolutionary dynamics of immune-related genes and pathways in disease-vector mosquitoes. Science. 2007;316:1738–1743. doi: 10.1126/science.1139862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Yang M, Sun J, Qian J, Zhang D, Sun Y, Ma L, Zhu C. Glycogen branching enzyme: a novel deltamethrin resistance-associated gene from Culex pipiens pallens. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:449–458. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Qian J, Sun J, Xu Y, Zhang D, Ma L, Sun Y, Zhu C. Cloning and characterization of myosin regulatory light chain (MRLC) gene from Culex pipiens pallens. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;151:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Gao Q, Li J, Shen B, Chao J, Zhu C. The preliminary study on occurrence and development of deltamethrin resistance in Anopheles minimus. Chin J Schisto Control. 2001;13:337–339. [Google Scholar]

- Zou Z, Shin SW, Alvarez KS, Bian G, Kokoza V, Raikhel AS. Mosquito RUNX4 in the immune regulation of PPO gene expression and its effect on avian malaria parasite infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18454–18459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804658105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.