Background: α-Synuclein has a central role in Parkinson disease, and it has been proposed to regulate mitochondrial morphology and autophagic clearance.

Results: α-Synuclein overexpression augments mitochondrial Ca2+ transients by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interactions.

Conclusion: Physiological levels of α-synuclein are required to sustain mitochondrial function and morphology integrity.

Significance: Mitochondrial Ca2+ represents an important site where α-synuclein can modulate cell bioenergetics and survival.

Keywords: α-Synuclein, Calcium, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Mitochondrial Transport, Signal Transduction

Abstract

α-Synuclein has a central role in Parkinson disease, but its physiological function and the mechanism leading to neuronal degeneration remain unknown. Because recent studies have highlighted a role for α-synuclein in regulating mitochondrial morphology and autophagic clearance, we investigated the effect of α-synuclein in HeLa cells on mitochondrial signaling properties focusing on Ca2+ homeostasis, which controls essential bioenergetic functions. By using organelle-targeted Ca2+-sensitive aequorin probes, we demonstrated that α-synuclein positively affects Ca2+ transfer from the endoplasmic reticulum to the mitochondria, augmenting the mitochondrial Ca2+ transients elicited by agonists that induce endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. This effect is not dependent on the intrinsic Ca2+ uptake capacity of mitochondria, as measured in permeabilized cells, but correlates with an increase in the number of endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria interactions. This action specifically requires the presence of the C-terminal α-synuclein domain. Conversely, α-synuclein siRNA silencing markedly reduces mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, causing profound alterations in organelle morphology. The enhanced accumulation of α-synuclein into the cells causes the redistribution of α-synuclein to localized foci and, similarly to the silencing of α-synuclein, reduces the ability of mitochondria to accumulate Ca2+. The absence of efficient Ca2+ transfer from endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria results in augmented autophagy that, in the long range, could compromise cellular bioenergetics. Overall, these findings demonstrate a key role for α-synuclein in the regulation of mitochondrial homeostasis in physiological conditions. Elevated α-synuclein expression and/or eventually alteration of the aggregation properties cause the redistribution of the protein within the cell and the loss of modulation on mitochondrial function.

Introduction

Parkinson disease (PD)3 is a common neurodegenerative disease characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (1) and formation of intraneuronal protein aggregates called Lewy bodies (2). The etiology of the disease is still unknown but probably involves a combination of genetic and environmental factors inducing mitochondrial dysfunctions (3).

Specific mutations in nuclear genes encoding α-synuclein (α-syn), DJ-1, LRRK2, PINK1, and parkin as well as within the mtDNA were identified in familial forms of PD (about 5–10% of cases), giving the possibility, by manipulating their expression levels in cellular and animal models, to investigate their physiological function and early pathogenic changes that may lead to neurodegeneration.

α-syn, a major component of Lewy bodies, is a small protein of 140 amino acids prevalently localized in the cytosolic compartment at the presynaptic level in neurons. Recently, it was also shown to localize to mitochondria (4, 5) and to contain a mitochondrial targeting sequence (6). α-syn function is still unclear, but emerging evidence suggests that it interacts with phospholipids membranes acting as critical regulator of vesicle dynamics at the synapse (7–9). Despite that the interpretation of the various phenotypes caused by wt or mutant α-syn overexpression and/or α-syn deficiency is complex and remains sometime controversial, alterations of mitochondrial function have been clearly documented in different cellular and animal models by several groups. α-syn accumulation has been associated with mitochondrial complex I dysfunction (6, 10, 11), and α-syn null mice display striking resistance to the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and dopamine release (12, 13). Mitochondrial defects including altered morphology, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, increased mitochondrial ROS, reduced complex I activity, and cytochrome c release were observed in α-syn transgenic mice (14) and in cells overexpressing α-syn (4, 15, 16). Recently, it has been shown that α-syn directly regulated the mitochondria dynamics by participating in the fusion/fission process and autophagy (17–19).

The molecular mechanisms underlying the observed dysfunctions need to be elucidated, and we decided to investigate the role of α-syn in mitochondrial function by overexpressing it in an exogenous system, SH-SY5Y or HeLa cells, and analyzing the effects on Ca2+ homeostasis in living cells. By directly measuring mitochondrial Ca2+ dynamics and by monitoring mitochondria morphology in living cells, we have found that α-syn is essential to control mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and mitochondrial architecture, playing a role in modulating the contacts between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In addition, we have found that the observed effects are dependent both to α-syn cytosolic distribution and abundance, as its redistribution to localized foci or its silencing abolished enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Thus α-syn is essential to sustain mitochondrial functions; when this action is lost the autophagic response is augmented.

This α-syn function certainly adds further complexity to the multifaceted nature of PD-related proteins, but the findings are particularly interesting, underlining the possibility that the modulation of ER-mitochondria cross-talk may represent a common pathway in neurodegeneration.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Constructs

Plasmids encoding wt and α-syn-(1–97) and TAT-fusion wt α-syn recombinant proteins were previously described (20). C-terminal Myc-tagged α-syn-(1–97) construct was generated by PCR amplification using the forward (5′-GAAGTTCGAATTCATGGATGTATTCATGAAAGGACT-3′) and reverse (5′-ACTTCTCACTCGAGTTACAGATCTTCTTCAGAAATAAGTTTTTGTTCCTTTTTGACAAAGCCAGTGGCTGC-3′) and cloned in pcDNA3 expression vector. The construct was verified by sequencing. Mitochondria-targeted RFP and GFP (mtRFP and mtGFP) and ER-targeted GFP (erGFP) expression vectors were kindly provided by Prof. R. Rizzuto, University of Padova. Plasmids encoding recombinant targeted aequorin probes were previously described (21).

Cell Cultures and Transfection

HeLa cells and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium high glucose (DMEM, Euroclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Euroclone), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin; 12 h before transfection, cells were seeded onto 13-mm (for aequorin measurements) or 24-mm (for tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) and ER-mitochondria contact sites analysis) glass coverslips and allowed to grow to 60–80% confluence. For Ca2+ and TMRM measurements, HeLa cells were co-transfected with aequorin and GFP/RFP constructs, respectively, and empty vector (mock) or α-syn expressing plasmids in a 1:2 ratio with the calcium-phosphate procedure as previously described (22). SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were transfected by using the TransFectin Lipid Reagent (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ca2+ measurements were performed 36 h later. Cells plated for Western blotting were collected 24–36 h after transfection. For TAT-mediated delivery, recombinant TAT fusion proteins were added directly onto the seeded aequorin-transfected cells and incubated for 2.5–5 h in DMEM, 10% FBS, and antibiotics at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After incubation with TAT fusion proteins, the cells were extensively washed with PBS before starting Ca2+ measurements. In the case of valproic acid (VPA) incubation, the cells were treated for 6 days in DMEM, 10% FBS, and antibiotics at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere and the day before the experiment transfected with mtAEQ or mtRFP. Where indicated the cells were treated with bafilomycin A1 (Sigma) 100 μm for 16 h.

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal anti-α-syn antibody (sc-12767, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used at a 1:30 dilution in immunocytochemistry analysis and at a 1:500 dilution in Western blotting analysis. Mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (AC-15, Sigma) was used at a 1:90,000 dilution in Western blotting. Mouse anti-Myc (4A6, Millipore) was used at a 1:50 dilution in immunocytochemistry and 1:2000 in Western blotting analysis. Rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3 antibody (LC3B, #2775 Cell Signaling) and rabbit polyclonal anti-p62 antibody (p62, #p0067 Sigma) were used at 1:750 and 1:1000 dilutions, respectively, in Western blotting analysis.

Immunocytochemistry Analysis

Transfected HeLa cells plated on coverslips were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 140 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1.5 mm KH2PO4, 8 mm Na2HPO4, pH 7.4) for 20 min and washed 3 times with PBS. Cell permeabilization was performed by 20 min of incubation in 0.1% Triton X-100 PBS followed by 30 min wash in 1% gelatin (type IV, from bovine skin, Sigma) in PBS at room temperature. The coverslips were then incubated for 90 min at 37 °C in a wet chamber with the specific antibody diluted in PBS. Staining was revealed by the incubation with specific AlexaFluor 488 or 594 secondary antibodies for 45 min at room temperature (1:100 dilution in PBS; Invitrogen). Fluorescence was analyzed with a Zeiss Axiovert microscope equipped with a 12-bit digital cooled camera (Micromax-1300Y; Princeton Instruments Inc., Trenton, NJ) or Leica Confocal SP2 microscope. Images were acquired by using Axiovision 3.1 or Leica AS software. Where indicated, raw images were smoothed by applying the Gaussian blur filter of the Image J 1.45e software for mitochondrial network morphology assessment.

Aequorin Measurements

Mitochondrial low affinity aequorin (mtAEQ) and cytosolic wt aequorin (cytAEQ) were reconstituted by incubating cells for 3 h (cytAEQ) or 1.5 h (mtAEQ) with 5 μm wt coelenterazine (Invitrogen) in DMEM supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. To functionally reconstitute low affinity ER-targeted aequorin (erAEQ), the ER Ca2+ content had to be drastically reduced. To this end, cells were incubated for 1.5 h at 4 °C in Krebs-Ringer modified buffer (KRB,125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1 mm Na3PO4, 1 mm MgSO4, 5.5 mm glucose, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 37 °C) supplemented with the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (5 μm), 600 μm EGTA, and 5 μm coelenterazine (Invitrogen). Cells were then extensively washed with KRB supplemented with 2% bovine serum albumin and 1 mm EGTA (21).

After reconstitution, cells were transferred to the chamber of a purpose-built luminometer, and Ca2+ measurements were started in KRB medium added with 1 mm CaCl2 or 100 μm EGTA or 1 mm EGTA according the different protocols and aequorin probes. 100 μm histamine in HeLa cells or 100 nm bradykinin were added as specified in the figure legends.

For mitochondrial Ca2+ measurements in permeabilized cells after reconstitution, the cells were transferred in an intracellular buffer (IB) (130 mm KCl, 10 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm KH2PO4, 1 mm MgSO4, 5 mm sodium succinate, 3 mm MgCl2, 20 mm HEPES, 5.5 mm glucose, 1 mm pyruvic acid supplemented with 2 mm EGTA, and 2 mm HEDTA, pH 7.0) and then permeabilized in the same buffer supplemented with 25 μm digitonin for 1 min. Cells were then perfused with IB/EGTA containing 1 mm ATP (IB/EGTA-ATP) and transferred to the luminometer chamber. Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria was initiated by replacing IB/EGTA-ATP buffer with IB containing a 2 mm EGTA-HEDTA-buffered Ca2+ of 1 μm, prepared as elsewhere described (23, 24).

All the experiments were terminated by cell lysis with 100 μm digitonin in a hypotonic Ca2+-rich solution (10 mm CaCl2 in H2O) to discharge the remaining reconstituted active aequorin pool. The light signal was collected and calibrated off-line into Ca2+ concentration values using a computer algorithm based on the Ca2+ response curve of wt and mutant aequorin as previously described (25, 26).

Western Blotting Analysis

HeLa cells were flooded on ice with 20 mm ice-cold N-ethylmaleimide in PBS to prevent post-lysis oxidation of free cysteines. Cell extracts were prepared by solubilizing cells in ice-cold 2% CHAPS in Hepes-buffered saline (50 mm HEPES, 0.2 m NaCl, pH 6.8) containing N-ethylmaleimide, 1 mm PMSF, and mixture protease inhibitors (Sigma). Postnuclear supernatants were collected after 10 min of centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4 °C. The total protein content was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Samples were loaded on a 15% SDS-PAGE Tris/HCl gel, transferred onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), and incubated overnight with the specific primary antibody at 4 °C. Detection was carried out by incubation with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1.5 h at room temperature. The proteins were visualized by the chemiluminescent reagent Immobilon Western (Millipore). Densitometric analyses were performed by using Kodak1D image analysis software (Kodak Scientific Imaging Systems, New Haven, CT). Means of densitometric measurements of at least three independent experiments, normalized by the endogenous β-actin values, were compared by Student's t test.

siRNA-mediated Knockdown

HeLa cells were transfected with cell validated predesigned siRNA oligonucleotides (Qiagen) directed against human α-syn (Hs_SNCA_5 siRNA, SI03026478, Target transcript: NM_000345) using the Attractene reagent (Qiagen), which is also highly suitable for cotransfection of plasmid DNA with siRNA. The siRNA transfection protocol was adjusted according to the manufacturer's instructions (18 pmol of each siRNA oligo were added for each 2 μl of Attractene). RNAi negative control duplex, i.e. scramble siRNA (which sequence matched no known mRNA sequence in the vertebrate genome) was purchased from Qiagen (AllStars Neg. siRNA AF 488, 1027284). Briefly, the day before the experiment the cells were seeded at 70–80% confluence in a 24-well plate in 500 μl of culture medium containing serum and antibiotics. The day after, transfection complexes were added dropwise and incubated under normal growth conditions. Gene down-regulation and mitochondrial Ca2+ transients were monitored after 36–48 h after transfection.

TMRM Analysis

The TMRM “non-quenching” method was used, which is adequate for the comparison of the membrane potential between two populations of cells (27), and thus a decrease in TMRM signal reflected mitochondrial depolarization. HeLa cells seeded on coverslips were cotransfected with α-syn-expressing plasmid and cytosolic-GFP as a marker of cotransfection, and 30 h after transfection cells were loaded with 20 nm TMRM for 30 min at 37 °C in KRB containing 1 mm CaCl2 and 5.5 mm glucose. TMRM fluorescence was registered at a 510-nm wavelength with a Leica SP2 confocal microscope at 40× magnification. The normalized TMRM fluorescence intensity was obtained by acquiring images before and after application of 10 μm proton ionophore carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) to redistribute TMRM away from mitochondria. Measurements were corrected for residual TMRM fluorescence after full Δψm collapse with FCCP. Basal average TMRM signal was normalized to the average remaining signal obtained upon FCCP treatment and shown as Δ fluorescence above the threshold. Regions of interest were off-line-positioned across the peripheral cell area, and TMRM fluorescence was analyzed using ImageJ software.

Analysis of Mitochondrial Morphology

mtRFP fluorescence from positive-cotransfected cells was used to reveal mitochondrial morphology.

Cells that displayed a network of filamentous mitochondria were classified as normal (not fragmented), and cells with fragmented or partially truncated mitochondria were classified as fragmented (see representative images in Fig. 3C). To evaluate mitochondrial shape, fluorescence microscopy images of randomly selected fields were acquired, and every single mitochondrion of the investigated cells was marked to analyze morphological characteristics such as its area, perimeter, and major and minor axes. On the basis of these parameters, the mitochondrion circularity and its form factor (4π × area/perimeter2 (28)), consistent with a measure of mitochondrial length and the degree of branching, were calculated as described in Dagda et al. (29).

FIGURE 3.

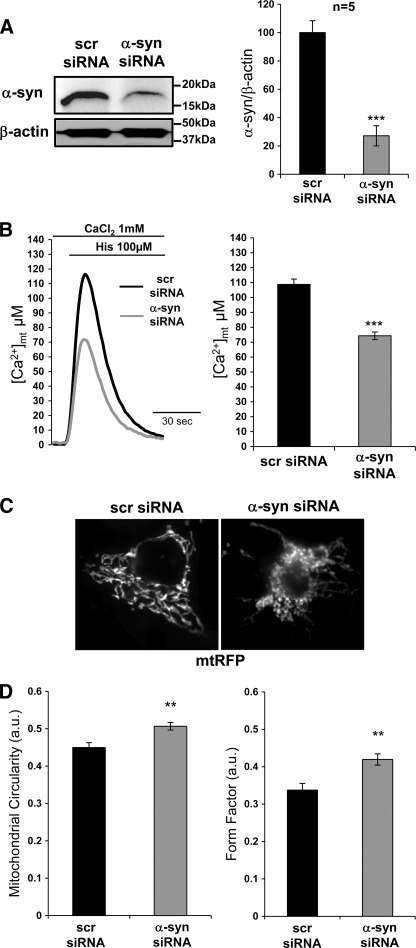

Silencing of α-synuclein impairs mitochondrial Ca2+ transients and morphology. A, shown are Western blotting and densitometric analysis of siRNA-mediated silencing of endogenous α-syn in HeLa cells. Results are the mean ± S.E. ***, p < 0.0001. B, mitochondrial Ca2+ transients were induced by cell stimulation, where 100 μm histamine was applied. The traces are representative of at least eight independent experiments. Bars indicate the average heights of peak values. Results are the mean ± S.E. ***, p < 0.0001. C, α-syn siRNA or Scr siRNA and mtRFP were co-transfected in HeLa cells. After 36–48 h cells were observed under fluorescence microscope to evaluate mitochondrial morphology. The panel displays representative mitochondrial phenotypes observed by monitoring mtRFP fluorescence. D, shown is quantification of mitochondrial morphology by calculating mitochondrial circularity and form factor (see “Experimental Procedures” for details). a.u., arbitrary units. A value of 1 corresponds to a perfect circle. Results are the mean ± S.E., **, p < 0.005, n = 25 cells/conditions, two independent experiments.

ER-mitochondria Contact Site Analysis

Cells plated on 24-mm-diameter coverslips were transfected with erGFP and mtRFP together with empty or α-syn or α-syn-(1–97)-expressing vectors. Fluorescence was analyzed in living cells by a Leica SP2 confocal microscope. Cells were excited separately at 488 or 543 nm, and the single images were recorded. Confocal stacks were acquired every 0.2 μm along the z axis (for a total of 40 images) with a 63× objective. Cells were maintained in KRB containing 1 mm CaCl2 and 5.5 mm glucose during acquisition of images. For mitochondria-ER interaction analysis, stacks were automatically thresholded using ImageJ, deconvoluted, three-dimensional-reconstructed, and surface-rendered by using VolumeJ (ImageJ). Interactions were quantified by Manders' colocalization coefficient as already described (30, 31).

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as the means ± S.E. Statistical differences were evaluated by Student's two-tailed t test for impaired samples, with p value 0.01 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Subcellular Localization of Overexpressed α-Synuclein and Effects on Calcium Homeostasis

The effects of α-syn overexpression were investigated by overexpressing it in dopaminergic neurons, the human neuroblastoma cells line SH-SY5Y, and in HeLa cells and analyzing the impact on Ca2+ signaling. Analysis of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis was performed using aequorin probes targeted to the mitochondrial matrix (mtAEQ), to the cytosol (cytAEQ), or to the lumen of the ER (erAEQ) (21). The expression level and subcellular localization of overexpressed wt α-syn were first verified. Western blotting analysis was performed on transfected SH-SY5Y or HeLa cells and showed a significant increase in α-syn expression compared with the endogenous level of empty vector-transfected cells (Fig. 1A). The endogenous level of α-syn in SH-SY5Y cells was hardly detectable. Equal loading of proteins was verified by probing the membrane with an anti-β-actin antibody, and quantification by densitometric analysis on the whole population revealed an increase of about 50% (100 ± 9.64% in mock cells versus 147.69 ± 9.87% in α-syn-overexpressing HeLa cells, p < 0.01, n = 3). However, considering that the average of transient transfections in HeLa cells was about of 25%, the overexpression of α-syn in transfected cells approached about 3-fold with respect to the endogenous content. Immunofluorescence experiments performed in HeLa and in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells revealed a diffuse cytosolic staining with no nuclear exclusion (Fig. 1B). Negative untransfected cells showing the endogenous levels of α-syn are visible in the panel relative to HeLa cells. SH-SY5Y untransfected cells show no fluorescence signal. The possible co-localization of α-syn and mitochondria was investigated by co-expressing α-syn and mtRFP probe in HeLa cells; no clear signal in mitochondria was detected with anti-α-syn antibodies, and the merging picture failed to reveal co-localization, indicating that the overexpressed α-syn was prevalently cytosolic (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, mtRFP failed to reveal morphological alterations in mitochondria of α-syn-overexpressing cells, as it showed the typical filamentous structure of mitochondrial network (see the Gaussian blur panel) as well as in cells transfected only with mtRFP (right panel of Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Western blotting analysis, immunolocalization, and Ca2+ measurements in wt α-synuclein-overexpressing cells. SH-SY5Y or HeLa cells were transfected with wt α-syn expression plasmid and analyzed by Western blotting (A) or immunocytochemistry (B). C, shown are HeLa cells co-transfected with mtRFP and α-syn or transfected with mtRFP only. The merge image revealed no colocalization between α-syn and mtRFP. Gaussian blur analysis was performed with ImageJ software to remove the signal out of focus. mtRFP fluorescence revealed intact filamentous mitochondrial morphology in α-syn-expressing cells as in cells transfected only with mtRFP. Mitochondrial Ca2+ transients, [Ca2+]m, in SH-SY5Y (D) or HeLa cells (E) overexpressing α-syn are shown. Cells were transfected with mtAEQ (control) or co-transfected with mtAEQ and wt α-syn. Bars represent the mean [Ca2+] values upon stimulation. Results are the mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.001. The traces are representative of at least nine independent experiments. Cytosolic ([Ca2+]c) (F) and ER ([Ca2+]er) (G) Ca2+ concentration in HeLa cells overexpressing wt α-syn are shown. Cells were transfected with cytAEQ or erAEQ (control) or co-transfected with cytAEQ or erAEQ and wt α-syn. Bars represent the mean [Ca2+] values upon stimulation (F) and resting [Ca2+] (G). Results are the mean ± S.E. Panel G shows the kinetics of ER refilling upon re-addition of CaCl2 1 mm to Ca2+-depleted cells (see “Experimental Procedures”). The traces are representative of at least 13 independent experiments. Where indicated 100 nm bradykinin or 100 μm histamine, two InsP3 generating agonists, were applied.

Then measurements of mitochondrial Ca2+ transients generated by cell stimulation were carried out using mtAEQ (21). Representative traces of typical experiments and statistical analysis are shown in Fig. 1, D and E. Where indicated, cells were exposed to 100 nm bradykinin (BK) or 100 μm histamine (His), causing the generation of inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate (InsP3) and the consequent opening of the InsP3 channels of the intracellular stores. Fig. 1D refers to SH-SY5Y, and Fig. 1E refers to HeLa cells; mitochondrial Ca2+ transients in α-syn-overexpressing cells were significantly higher than those observed in control cells (peak values: 53.5 ± 2.76 μm in control SH-SY5Y cells, n = 11, versus 70.6 ± 2.88 μm in α-syn-overexpressing SH-SY5Y cells, n = 14, p < 0.0005 and 116.52 ± 2.84 μm in control HeLa cells, n = 10, versus 140.74 ± 5.7 μm in α-syn-overexpressing HeLa cells, n = 9, p < 0.001), indicating that the observed effects were not cell type-specific. To verify whether α-syn could play a general role in Ca2+ homeostasis, Ca2+ measurements were also performed in the cytosol and in the lumen of the ER by using specifically targeted aequorin probes. Fig. 1, F and G, showed no significant differences between α-syn-overexpressing and control HeLa cells (cytosolic peak values: 3.33 ± 0.04 μm in control cells, n = 14, versus 3.24 ± 0.04 μm in α-syn-overexpressing cells, n = 13; ER Ca2+ levels: 424.00 ± 18.40 μm in control cells, n = 15, versus 415.90 ± 24.00 μm in α-syn-overexpressing cells, n = 13), highlighting the possibility that α-syn may have a specific mitochondrial role.

Cytosolic and ER Ca2+ measurements in SH-SY5Y cells also failed to reveal differences between controls and α-syn-overexpressing cells (not shown). To avoid possible biochemical alterations associated with increased α-syn levels and dopamine oxidation in dopaminergic SH-SY5Y cells, it was decided to perform the following experiments only in HeLa cells.

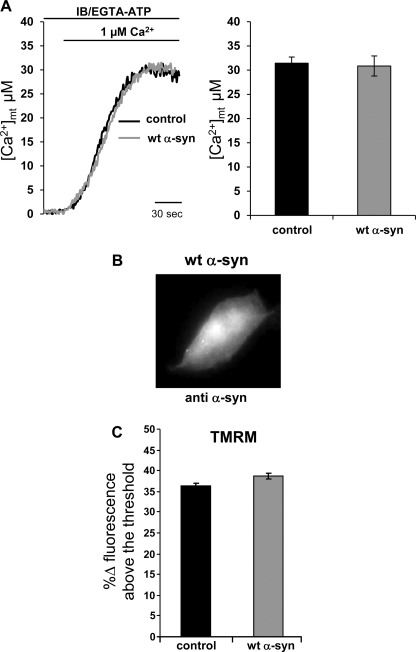

Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake Machinery Was Not Modified by α-Synuclein Overexpression

Mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation depends on the proton electrochemical gradient that drives rapid accumulation of cations across the ion-impermeant mitochondrial inner membrane and on the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter that, upon cell stimulation, is exposed to microdomains of high Ca2+ concentration that well match its low Ca2+ affinity and are sensed thanks to the close contact of mitochondria with ER Ca2+ channels (32). To investigate whether the overexpressed α-syn could directly interfere with the mitochondrial Ca2+ transport machinery, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in α-syn-overexpressing cells was investigated in permeabilized cells exposed to fixed Ca2+ concentration solution. Briefly, transfected HeLa cells were perfused with a solution mimicking the intracellular milieu (IB), supplemented with 2 mm EGTA, and permeabilized with 25 μm digitonin for 1 min (for details see “Experimental Procedures”). Then the perfusion buffer was changed to IB/EGTA-ATP-buffered Ca2+ of 1 μm, eliciting a gradual rise in mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m) that reached a plateau value of ∼30 μm (31.43 ± 1.27 μm in mock cells, n = 16, versus 30.86 ± 2.07 μm in α-syn-overexpressing cells, n = 14) (Fig. 2A). In α-syn-overexpressing HeLa cells, the [Ca2+]m increase was similar to that observed in controls. To exclude that the absence of effects was due to the release of α-syn after digitonin treatment, immunocytochemistry analysis was performed on permeabilized cells, and Fig. 2B showed diffuse intracellular α-syn distribution as in control cells. Because α-syn is not released after cell permeabilization, it is plausible to think that, due to its propensity to interact with lipids and membrane (33), it could be associated directly (or indirectly through other proteins) to intracellular membranes, including mitochondrial membranes as previously shown (34). Then mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was estimated in resting conditions by loading cells with the potential-sensitive probe TMRM. The results shown in Fig. 2C revealed no significant differences in the TMRM fluorescence measured in α-syn-overexpressing cells compared with the control (36.16 ± 0.99% in mock cells, n = 124, cells versus 38.81 ± 0.67% in α-syn-overexpressing cells, n = 209 cells), indicating that the driving force for mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation is equivalent in the two cell batches.

FIGURE 2.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in permeabilized cells and mitochondrial membrane potential are not affected by wt α-synuclein overexpression. A, shown are representative traces (left) and average plateau [Ca2+]m values (right, results are the mean ± S.E.) reached in permeabilized cells exposed to 1 μm Ca2+-buffered solution. Where indicated, the medium was switched from IB/EGTA-ATP to IB/1 μm Ca2+. The traces are representative of at least 14 independent experiments. B, shown is immunocytochemistry analysis on permeabilized HeLa cells overexpressing wt α-syn. The staining with monoclonal antibody against α-syn was revealed by AlexaFluor 488-conjugated antibody. C, HeLa cells (control and overexpressing wt α-syn) were loaded with TMRM probe to determine the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ). Bars represent the average TMRM fluorescence signals subtracted of signals remaining after FCCP treatment to collapse ΔΨ and are expressed as % Δ fluorescence. The analysis was performed on n = 124 mock cells and on n = 209 α-syn-overexpressing cells.

Threshold Levels of Endogenous α-Synuclein Are Required to Maintain Mitochondrial Network Architecture and Ca2+ Homeostasis

To address the possible role of α-syn in mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis, a siRNA-mediated silencing of endogenous α-syn was performed in HeLa cells, and mitochondrial Ca2+ measurements were carried out in these cells. Efficient knockdown of endogenous α-syn has been determined by Western blotting analysis. As shown in Fig. 3A, treatment with a siRNA specific for α-syn led to a ≈ 70% reduction of the endogenous protein level compared with cells treated with a scrambled control siRNA. The quantification was carried out by densitometric analysis, and the α-syn levels were normalized with respect to the β-actin levels as indicated in the histograms.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ measurements were performed after α-syn-mediated siRNA knockdown. As shown in Fig. 3B, down-regulation of the α-syn intracellular level is associated with a concomitant reduction in the mitochondria ability to take up Ca2+, the mitochondrial peak height being of 108.75 ± 3.60 μm in scrambled siRNA control cells, n = 8, versus 74.28 ± 2.53 μm in α-syn siRNA-treated cells, n = 10, p < 0.0001. To investigate the morphology of mitochondria, α-syn siRNA-treated HeLa cells were co-transfected with mtRFP and observed under a fluorescent microscope (Fig. 3C). When the scramble siRNA was applied, the majority of mtRFP-positive cells showed an intact network of tubular mitochondria, but interestingly, upon down-regulation of α-syn expression, the percentage of cells with truncated or fragmented mitochondria was significantly increased from about 15% in scramble siRNA-treated cells up to 70% in α-syn siRNA-treated cells. The analysis was performed on n = 33 cells from 2 independently transfected coverslips of each batch. Mitochondria morphology was classified as “tubular” or “fragmented” according to the images shown in Fig. 3C. Mitochondrial morphology was also quantified in the two batches of mtRFP-positive cells using ImageJ software (Fig. 3D). Evaluation of mitochondria circularity (as index of elongation) and form factor (as index of elongation and degree of branching) revealed a reduction both in elongation and in branching in α-syn siRNA-treated cells with respect to scrambled siRNA control cells (the value of 1 corresponding to a perfect circle (35)).

To establish a relationship between α-syn levels and mitochondrial Ca2+ signaling, we decided to modify its endogenous content by treating HeLa cells with VPA. VPA has been shown to cause a robust dose- and time-dependent increase in the levels of endogenous α-syn protein and mRNA (36). A 6-day treatment of HeLa cells with VPA caused a dose-dependent increase in α-syn protein levels, as documented by Western blotting analysis and quantification by densitometric analysis (Fig. 4A). Immunocytochemistry analysis also revealed a marked increase of the α-syn signal upon VPA treatment and more strikingly highlighted a dose-dependent intracellular redistribution of α-syn (Fig. 4B). Indeed, in cells exposed to high doses of VPA (≥250 μm), the antibody against α-syn revealed the formation of cytoplasmic foci reminiscent of stalled vesicles, as previously described (7, 37). Mitochondrial Ca2+ measurements in cells treated with increasing doses of VPA (from 0.1 μm up to 1 mm) revealed a significant increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake capacity at low VPA doses followed by a dose-dependent significant decrease at high doses (≥250 μm). Fig. 4, C and D, show the statistical analysis and representative experiments, with average Ca2+ peak values of 113.71 ± 3.57 μm in control cells (mtAEQ) n = 16, 143.95 ± 2.69 μm in α-syn-overexpressing cells n = 16 p < 0.0001, 133.91 ± 2.50 μm n = 6 p < 0.005 in 0.1 μm VPA treated cells, 115.22 ± 4.59 μm n = 5 in 10 μm VPA-treated cells, 94.63 ± 3.32 μm n = 6 in 250 μm VPA-treated cells p < 0.01, and 83.16 ± 1.86 μm n = 6 in 1 mm VPA-treated cells p < 0.001. To exclude the possibility that high doses of VPA could be toxic and thus damage the mitochondria, thus explaining the observed phenotype, the mitochondrial network integrity upon VPA treatment was explored by monitoring fluorescence in mitochondria labeled with mtRFP or mtGFP. Fig. 4E shows that VPA treatment does not affect mitochondrial network integrity, highlighting the presence of tubular structures similar to those observed in untreated cells. A double immunocytochemistry analysis was also performed to check whether VPA treatment could induce α-syn co-localization with mitochondria, but this was not the case (Fig. 4F).

FIGURE 4.

Dose-dependent valproic acid treatment increases the endogenous content of α-synuclein, induces its redistribution to cytoplasmic foci, and affects mitochondrial Ca2+ transients and autophagic process. HeLa cells were incubated with VPA in DMEM at 37 °C in CO2 atmosphere for 6 days at the indicated doses and then transfected with mtAEQ or mtRFP or mtGFP. Western blotting (A) and immunocytochemistry analysis (B) of α-syn expression levels and distribution after VPA treatment is shown. Numbers in panel A refer to normalized α-syn/β-actin ratio ± S.E. in four independent Western blottings. Statistical analysis (C) and representative experiments (D) of mitochondrial Ca2+ measurements in HeLa cells treated with VPA are shown. Results are the mean ± S.E. ***, p < 0.0001; **, p < 0.005; *, p < 0.01; NS, not significant. Where indicated the cells were stimulated with 100 μm histamine. The traces are representative of at least five independent experiments. E, mitochondrial morphology in HeLa cells treated with VPA was evaluated under fluorescent microscope by observing cotransfected mtRFP. F, immunocytochemistry analysis with anti α-syn antibody in HeLa cells treated with 1 mm VPA and transfected with mtGFP is shown. No α-syn and mtGFP colocalization was observed in these conditions. G, Western blotting analysis of LC3 I, LC3 II, and p62 levels in VPA-treated cells is shown; β-actin levels were also shown. Bars indicate the average values obtained by densitometric analysis of five independent experiments. Results are the mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.001.

Considering that autophagy is activated by defects in the InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release (34), autophagy levels were assayed by measuring LC3 II/LC3 I ratio in cells treated with VPA. The Western blotting and the densitometric analysis shown in Fig. 4G reveal that LC3 II/LC3 I ratio increased in 250 μm and 1 mm VPA-treated cells compared with untreated cells and with cells treated with 0.1–1 μm VPA. The levels of p62, another autophagy substrate, were also quantified by Western blotting and densitometric analysis (Fig. 4G). Interestingly, the observed increases in the autophagic process matched with a concomitant reduction in mitochondrial Ca2+ transients.

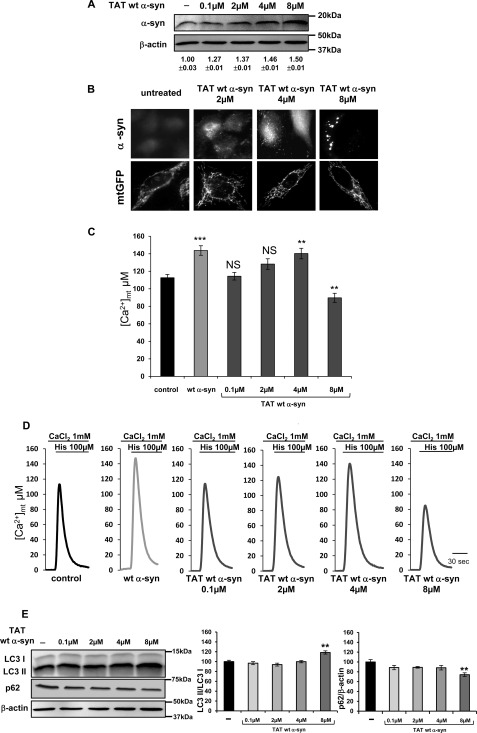

TAT-mediated wt α-Synuclein Delivery Affects Mitochondrial Ca2+ Homeostasis in Dose-dependent Manner

To exclude that the observed effects on mitochondrial Ca2+ were related to a general response to VPA treatment rather than to specific changes in α-syn levels and distribution, experiments were performed in HeLa cells where the α-syn intracellular concentration was increased by the exogenous addition of TAT wt α-syn fusion protein (20). As shown in Fig. 5, A and B, the Western blotting, the densitometric, and the immunocytochemistry analyses revealed a dose-dependent increase in the intensity of α-syn signal that paralleled α-syn redistribution from the cytoplasm to the cytosolic foci. Mitochondrial morphology was also evaluated by transfecting HeLa cells with mtGFP before TAT wt α-syn treatments; as documented in the panels of Fig. 5B, no alterations were observed, even at high TAT wt α-syn doses. Mitochondrial Ca2+ transients were monitored by transfecting HeLa cells with mtAEQ. An initial increase of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (at 4 μm TAT wt α-syn) was followed by a decrease at 8 μm TAT wt α-syn, when α-syn is predominantly localized to cytoplasmic foci (histograms represent the average peak values reached after cell stimulation and representative experiments are shown in Fig. 5, C and D; average peak values are 112.67 ± 3.72 μm, n = 9, in mock cells versus 143.75 ± 5.43 μm n = 5 in α-syn-overexpressing cells, p < 0.0005, 114.37 ± 4.34 μm n = 6 in 0.1 μm TAT wt α-syn-treated cells, 128.28 ± 6.08 μm n = 4 in 2 μm TAT wt α-syn-treated cells, 140.30 ± 6.01 μm n = 8 p < 0.005 in 4 μm TAT wt α-syn-treated cells, and 89.73 ± 5.19 μm n = 6 in 8 μm TAT wt α-syn-treated cells p < 0.005).

FIGURE 5.

Dose-dependent TAT-mediated wt α-synuclein delivery and effects on mitochondrial Ca2+ transients and autophagic process. HeLa cells were transfected with mtGFP or mtAEQ and then incubated with the indicated doses of TAT wt α-syn. Western blotting (A) and immunolocalization (B) of TAT wt α-syn are shown. Numbers in panel A refer to normalized α-syn/β-actin ratio ± S.E. in three independent Western blottings. Shown is statistical analysis (C) and representative experiments (D) of mitochondrial Ca2+ measurements in HeLa cells treated with TAT wt α-syn. Where indicated the cells were stimulated with 100 μm histamine. Bars represent the mean [Ca2+] values upon stimulation. Results are the mean ± S.E. ***, p < 0.0005; **, p < 0.005; NS, not significant. The traces are representative of at least four independent experiments. E, shown is Western blot analysis of LC3 I, LC3 II, and p62 levels in TAT α- syn-treated cells; β-actin levels were also shown. Bars indicate the average values obtained by densitometric analysis of four independent experiments. Results are the mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.001.

To confirm the increase of the autophagic process observed in concomitance with the reduction of mitochondrial Ca2+ transients in VPA-treated cells, the LC3 II/LC3 I ratio was also evaluated in TAT wt α-syn-treated cells. The Western blotting and the densitometric analysis shown in Fig. 5E revealed that the LC3 II/LC3 I ratio increased in 8 μm TAT α-syn-incubated cells, and under the same conditions the level of p62 decreased accordingly to the observed reduction in mitochondrial Ca2+ transients.

Enhancement of Mitochondrial Ca2+ Uptake Depends on α-syn Acidic C-terminal Domain

Because C-terminal truncation of α-syn seems to be one of the most common post-translational modifications of α-syn in the brains of patients with PD and it was shown that substoichiometric amounts of C-terminal-truncated α-syn enhance the in vitro aggregation of the more abundant full-length (38), it was felt to be interesting to study the effects of the overexpression of an α-syn mutant lacking the C-terminal domain (α-syn-(1–97)). Overexpression of the deletion mutant showed a diffuse intracellular pattern of distribution similar to the overexpressed wt α-syn as shown in Fig. 6A. In this case an anti-α-syn rabbit antiserum (kindly provided by Dr. E. Greggio, University of Padova) was used because the available α-syn monoclonal antibody previously used recognized an epitope in the C-terminal region. Unfortunately, we were not able to have it work in Western blotting. Fig. 6B shows that mitochondrial Ca2+ transients in α-syn-(1–97)-overexpressing cells are equivalent to those evoked in mock cells, indicating that the deletion of the C-terminal acidic domain completely abolished the ability of α-syn to enhance mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake (peak values: 100.4 ± 7.18 μm in mock cells n = 10 versus 100.3 ± 5.86 μm in α-syn-(1–97)-overexpressing cells n = 10). To better compare the effects of α-syn-(1–97) and wt α-syn, myc-tagged versions were constructed. Fig. 6, C and D document that both α-syn-(1–97) myc and wt α-syn myc were expressed and displayed a similar cytosolic distribution pattern. Fig. 6E confirms that the presence of the α-syn C-terminal tail is essential to enhance mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake; no differences in the mitochondrial Ca2+ transients generated by cell stimulation were observed between control cells and α-syn-(1–97) myc-overexpressing cells (peak values: 112.24 ± 3.71 μm in mock cells n = 32 versus 105.15 ± 4.04 μm in α-syn-(1–97) myc-overexpressing cells n = 19), whereas the expression of wt α-syn myc induced an increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ transients (peak values: 140.50 ± 5.77 μm n = 11) similar to that monitored in wt α-syn-untagged transfected cells. The monitoring of cytosolic Ca2+ transients failed to reveal differences with respect to control cells in both cases (Fig. 6F).

FIGURE 6.

Immunolocalization, Western blotting analysis, and Ca2+ measurements in HeLa cells expressing the C-terminal-truncated α-synuclein 1–97 mutant. HeLa cells were co-transfected with mtAEQ and α-syn-(1–97) or transfected with mtAEQ and empty vector (control). Two different constructs expressing α-syn-(1–97) were used: an untagged version in A and B and a myc-tagged construct in C–F. A wt α-syn myc construct was used as comparison. Immunolocalization (A) and mitochondrial Ca2+ measurements (B) in HeLa cells overexpressing α-syn-(1–97) are shown. Immunolocalization (C), Western blotting analysis (D), and mitochondrial (E) and cytosolic (F) Ca2+ measurements in HeLa cells overexpressing wt α-syn myc or α-syn-(1–97) myc are shown. Bars represent mean Ca2+ values upon stimulation. Results are the mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.001. Where indicated the cells were stimulated with 100 μm histamine. The traces are representative of at least 10 independent experiments.

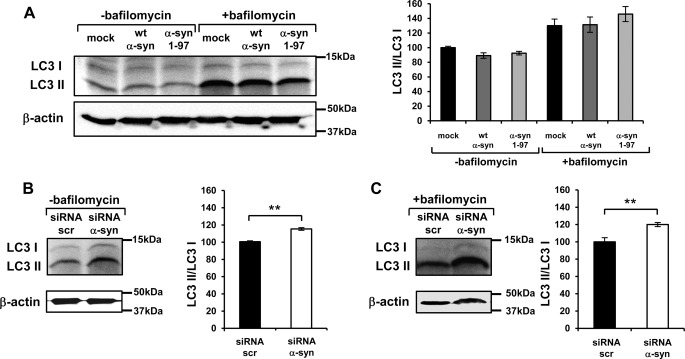

The autophagic process was also evaluated. Fig. 7A shows that the LC3 II/LC3 I ratio in wt α-syn- and α-syn-(1–97)-overexpressing cells was similar to that of control cells (even after bafilomycin treatment), in agreement with the situation observed for concentration VPA or TAT α-syn treatments that increased or did not affect mitochondrial Ca2+ transients. To further strengthen the findings, autophagy was evaluated in siRNA α-syn-treated cells and in their respective control transfected with scramble siRNA (Fig. 7, B and C), and an increased LC3 II/LC3 I ratio was found in α-syn-silenced cells both in absence (Fig. 7B) and in presence (Fig. 7C) of bafilomycin treatment, as previously reported (18).

FIGURE 7.

Evaluation of autophagy process in α-syn-overexpressing cells and in siRNA α-syn-treated cells. Western blotting analysis of LC3 I, LC3 II in wt α-syn and α-syn-(1–97)-overexpressing cells (A) or in α-syn siRNA-treated cells (B and C) both in the absence and in the presence of bafilomycin treatment; β-actin levels were also shown. Bars indicate the average values obtained by densitometric analysis of four independent experiments. Results are the mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.001.

α-Synuclein Increases Functional and Physical ER-Mitochondria Interactions and Acidic C-terminal Domain Is Required to This Function

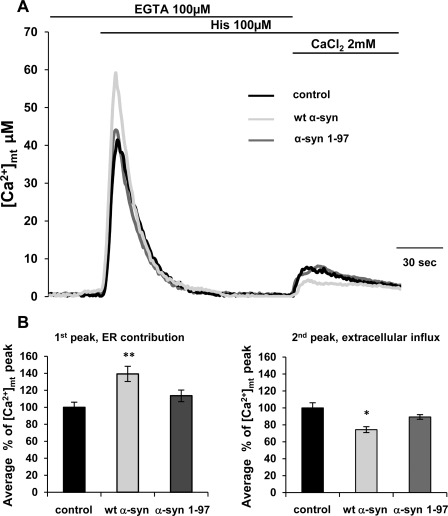

The Ca2+ measurements performed in permeabilized α-syn-overexpressing cells excluded the possibility that α-syn could directly affect the mitochondrial Ca2+ transporters activity; thus, to assess the molecular mechanisms responsible for α-syn action on mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis, the possibility that it could play a role in the formation and/or the stabilization of ER-mitochondria interactions has been investigated. First, the contribution of the ER Ca2+ release and that of the extracellular Ca2+ entry to the mitochondrial Ca2+ transients generation was analyzed separately. In these experiments, HeLa cells overexpressing either wt or α-syn-(1–97) were perfused in KRB containing 100 μm EGTA buffer and stimulated with 100 μm histamine; under these conditions a peak transient was generated reflecting the mitochondrial response to ER Ca2+ mobilization. Then the perfusion medium was switched to KRB supplemented with 2 mm CaCl2 (in the continuous presence of histamine), thus causing Ca2+ entry from the extracellular milieu that was primarily sensed by mitochondria located beneath the plasma membrane. The mitochondrial Ca2+ peak in response to ER Ca2+ mobilization (first peak) was significantly higher in cells overexpressing wt α-syn as compared with control cells; that in response to Ca2+ influx (second peak) was instead reduced (Fig. 8, A and B). As expected, in α-syn-(1–97) mutant-overexpressing cells, no effect was observed on mitochondrial Ca2+ transients, being the first and second peak equivalent to those of control cells (Fig. 8, A and B). The reduction of the second peak in α-syn-overexpressing cells is probably due to the effect of α-syn on Ca2+ influx induced by store depletion as previously documented (see “Discussion” and Ref. 39).

FIGURE 8.

Evaluation of the contribution of ER Ca2+ mobilization and of Ca2+ influx from the extracellular ambient on mitochondrial Ca2+ transients in wt and α-synuclein 1–97-overexpressing cells. HeLa cells were co-transfected with mtAEQ and α-syn constructs or transfected with mtAEQ only (control). To discriminate the contributions to [Ca2+]m transients, InsP3-induced Ca2+ release from intracellular stores was separated from the concomitant Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane. A, HeLa cells were perfused in KRB/EGTA 100 μm buffer and stimulated with histamine to release Ca2+ from the intracellular stores (first peak). Then, the perfusion medium was switched to KRB/Ca2+ 2 mm (in the continuous presence of histamine) to stimulate Ca2+ entry from the extracellular ambient (second peak). The traces are representative of at least 13 independent experiments. B, bars represent normalized mean [Ca2+] values upon stimulation, and results are the mean ± S.E. **, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.01.

Second, to directly test the possible involvement of α-syn in regulating ER-mitochondria contact sites, we performed live-cell confocal microscopy three-dimensional reconstructions of ER and mitochondria. HeLa cells were co-transfected with the mtRFP- and ER-targeted-GFP (erGFP) together with either wt α-syn or α-syn-(1–97) mutant, and ER-mitochondria co-localization was assessed. The single plane level analysis revealed a significant increase in ER-mitochondria contact sites in wt α-syn-overexpressing cells compared with mock cells, but not in α-syn-(1–97) mutant-overexpressing cells, as documented in the merging images of Fig. 9A. A more detailed quantification was carried out by acquiring confocal z axis stacks, applying volume rendering on the three-dimensional reconstructions and calculating the Manders' colocalization coefficient (31). Also with this analysis an enhancement in the ER/mitochondria co-localization was observed in α-syn-overexpressing cells with respect to mock-treated cells (mock cells, 100 ± 1.34%, n = 71 cells, and wt α-syn 109.23 ± 1.04%, n = 21 cells, p < 0.0001), but not in α-syn-(1–97) mutant-expressing cells (103.4 ± 1.04%, n = 37 cells), as documented in Fig. 9, B and C.

FIGURE 9.

ER-mitochondria interactions in HeLa cells overexpressing wt α-synuclein and truncated α-synuclein 1–97. A, shown are single plane confocal images showing ER (green, erGFP) and mitochondria (red, mtRFP) co-localization in mock or wt -syn or wt α-syn-(1–97)-transfected cells. Insets at higher magnification are also shown. B, bars represent normalized Manders' coefficient values calculated from z-axis confocal stacks. At least 21 cells were analyzed for each conditions (results are the mean ± S.E. ***, p < 0.0001). C, shown is three-dimensional reconstruction of mitochondria and ER in HeLa cells coexpressing mtRFP and an erGFP together with the void vector (mock), wt α-syn, or α-syn-(1–97) as indicated in each panel. Cells were excited separately at 488 or 543 nm, and the single images were recorded. The merging of the two images is shown for each condition. Yellow indicates colocalization of the two organelles. A better view of the area of colocalization is provided by the panels on the right. Confocal stacks were acquired every 0.2 μm along the z axis (for a total of 40 images) with a 63× objective.

DISCUSSION

A possible direct involvement of α-syn in Ca2+ homeostasis in living cells has been described by few reports, but the results were conflicting. An increase in membrane conductance and in cytosolic basal Ca2+ levels as well as augmented cytosolic Ca2+ transients were reported in A53T-expressing cells with respect to wt α-syn-expressing cells (40). Hettiarachchi et al. (39) in 2009 have instead shown that voltage-gated Ca2+ entry was similarly enhanced in neuronal cells expressing wt and mutant α-syn and that the Ca2+ influx pathways triggered by store depletion were significantly suppressed in wt α-syn-, A53T-, and S129D-expressing cells. Basal cytosolic Ca2+ levels and ER and mitochondria Ca2+ content were instead unaffected. A couple of reports described that overexpression of wt α-syn as well as that of A53T mutant enhanced the mitochondria ability to accumulate Ca2+ (16, 41), suggesting that α-syn-overexpressing cells could be more prone to mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, but the possibility that these increases could be physiological rather than pathological has not been considered. Mitochondria are essential for cell survival because they are involved in energy metabolism, cell signaling, and regulation in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis: their integrity is a key element for cell wellness. At the functional level, our study demonstrates that the α-syn is essential to maintain mitochondrial integrity and metabolism and that its depletion significantly reduces agonist-stimulated Ca2+ entry in mitochondrial matrix. We also found that wt α-syn overexpression induces an increase in the mitochondrial Ca2+ transients evoked by cell stimulation and that the entity of the transients is compatible with physiological levels of mitochondrial Ca2+ concentration. Intriguingly, by controlling these levels, α-syn also modulates the autophagic process; defects in ER-mitochondria Ca2+ transfer result in an activated autophagy, as previously documented (34).

The mechanism of these effects was investigated, and the results obtained in permeabilized cells excluded that α-syn could act in modulating the activity of mitochondrial Ca2+ transporters. Rather, evidence was obtained that α-syn plays a role in regulating the mitochondria/ER relationship. It is well known that mitochondria, despite the low affinity of the uniporter, can efficiently take up Ca2+ because sense high Ca2+ concentrations microdomains generated at the mouth of Ca2+ channels. In particular, in HeLa cells (but also in other cells type) mitochondria have been demonstrated to be juxtaposed to the InsP3 receptors, the main Ca2+ release channels of the ER, which also participate in the formation of contact sites (42). The ER-mitochondria contact sites were directly monitored and quantified by analyzing three-dimensional reconstructions of confocal images acquired from living cells co-transfected with erGFP and mtRFP and α-syn. Intriguingly, wt α-syn overexpression resulted in an increased tethering of the two organelles, whereas α-syn-(1–97) had no effects. The finding is particularly interesting because the intimate connection between ER and mitochondria has been reported to be at the basis of a bidirectional communication regulating a number of physiological processes ranging from mitochondrial energy production and lipid metabolism to Ca2+ signaling and cell death (43–45). Interestingly, the α-syn acidic C-terminal domain seems to be responsible for the observed phenotype, as the overexpression of α-syn-(1–97) mutant (in which the last 43 C-terminal residues were removed) failed to affect the mitochondrial Ca2+ transients and the formation of ER-mitochondria contact sites. Whether the presence of phosphorylation sites (i.e. Tyr-125, Tyr-133, and Tyr-136 or Ser 129) is necessary to this function is presently unknown. The C terminus has no structural elements, it has been shown to be necessary but not sufficient for a chaperone function (46), and it is thought that interactions between the C terminus and the central portion of the α-syn molecule may prevent or minimize aggregation/fibrillation (47).

In addition to the overexpression protocol, two alternative experimental procedures were used to increase the intracellular levels of α-syn: the VPA treatment and TAT-mediated delivery. Both of them confirmed the results obtained in α-syn-overexpressing cells and added new information on the possible mechanism of α-syn action. At high doses of VPA or TAT α-syn fusion protein, the increase in the α-syn expression levels correlated with a change in its intracellular distribution; the α-syn fluorescence is confined to punctuated cytoplasmic foci, and no diffuse cytosolic fluorescence signal was observed. When mitochondrial Ca2+ measurements were performed in these cells, a drastic reduction in mitochondrial Ca2+ transients was observed despite that the mitochondrial morphology was apparently unaltered. These data together with those obtained in α-syn siRNA experiments suggest that mitochondrial Ca2+ impairment possibly started before mitochondrial structure derangements, and it is related to α-syn sequestration out of the cytosol, thus proposing loss of function mechanism as responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction reported in dopaminergic cells of α-syn-related PD models. Interestingly, α-syn loss of function in addition to the effects on mitochondrial Ca2+ fluxes also resulted in increased autophagy, as documented both in α-syn siRNA and VPA or TAT α-syn-treated cells.

Our data also indicated that α-syn is required to maintain the mitochondrial network integrity as its down-regulation (but not its overexpression) clearly revealed a pattern of fragmented mitochondria. These results partially matched with recent data in the literature; some reports described no mitochondrial fragmentation upon α-syn overexpression (41), but others, even if through different mechanisms, have reported induced mitochondrial fragmentation (17, 19). These apparent discrepancies may be ascribed to the different expression level in cell models, the dose-dependent pathogenic role for the wt protein when overexpressed being well established (7). Even if we have not done accurate measurements of mitochondria volume and length, we can confidentially state that in our cell system, α-syn overexpression did not induce mitochondria fragmentation not only by the evaluation of mitochondrial morphology at fluorescence and confocal microscope but also because we found that that α-syn overexpression enhanced mitochondrial Ca2+ transients, the opposite to what it has been found in cells overexpressing the pro-fission protein Drp1 (48).

Altogether the data presented here indicate that α-syn is required for maintaining mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis and network integrity and for potentiating the ER-mitochondria connection, its C terminus acidic domain being essential to these functions. Some hypothesis can be done on the possible mechanisms; one intriguing possibility is that α-syn directly mediated the ER-mitochondria interaction by acting as a “bridge.” This mechanism is strongly supported by the finding that the molecular chaperone grp75 has been found to interact with α-syn (49, 50), and interestingly enough, grp75 has been demonstrated to couple InsP3 receptors with VDAC, the voltage-dependent anion channel of the outer mitochondrial membrane, and in this way to regulate the mitochondria Ca2+ uptake machinery (42).

As far as PD is concerned, several reports describe the fundamental contribution of mitochondria and ER to the cellular fate as well as a privileged communication between the two organelles as a key element for cell functions (7, 51, 52).

In summary, we have demonstrated that α-syn, by favoring Ca2+ transfer from the ER to mitochondria, sustains organelle function and morphological integrity. When the protein is defective, Ca2+ uptake is reduced, and mitochondria undergo massive fragmentation. Interestingly, it has been recently reported that in vivo RNAi-mediated α-syn silencing induces nigrostriatal degeneration and that the level of neurodegeneration correlates with the grade of down-regulation of α-syn protein and mRNA (53). When, however, protein is expressed at high levels, it is redistributed to cytosolic foci (7), and this also leads to the loss of its effect on mitochondrial signaling and to the increase of autophagic process. Overall, the data point to Ca2+-mediated signaling in mitochondria as an important site where α-syn can modulate cell bioenergetics and survival.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Laura Fedrizzi (University of Padova) for performing Ca2+ measurements on SH-SY5Y cells and Dr. Elisa Greggio (University of Padova) for providing α-syn rabbit antiserum.

The work was supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN 2008) and the local founding of the University of Padova (Progetto di Ateneo 2008).

- PD

- Parkinson disease

- α-syn

- α-synuclein

- mtRFP

- mitochondria-targeted RFP

- mtGFP

- mitochondria-targeted GFP

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- erGFP

- ER-targeted GFP

- TMRM

- tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester

- VPA

- valproic acid

- TAT

- Trans-Activator of Transcription

- mtAEQ

- mitochondrial aequorin

- cytAEQ

- cytosolic wt aequorin

- erAEQ

- ER-targeted aequorin

- KRB

- Krebs-Ringer modified buffer

- IB

- intracellular buffer

- FCCP

- carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- InsP3

- inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hirsch E. C., Hunot S., Faucheux B., Agid Y., Mizuno Y., Mochizuki H., Tatton W. G., Tatton N., Olanow W. C. (1999) Dopaminergic neurons degenerate by apoptosis in Parkinson disease. Mov. Disord. 14, 383–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spillantini M. G., Schmidt M. L., Lee V. M., Trojanowski J. Q., Jakes R., Goedert M. (1997) α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388, 839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thomas B., Beal M. F. (2007) Parkinson disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, R183–R194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shavali S., Brown-Borg H. M., Ebadi M., Porter J. (2008) Mitochondrial localization of α-synuclein protein in α-synuclein-overexpressing cells. Neurosci. Lett. 439, 125–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cole N. B., Dieuliis D., Leo P., Mitchell D. C., Nussbaum R. L. (2008) Mitochondrial translocation of α-synuclein is promoted by intracellular acidification. Exp. Cell Res. 314, 2076–2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Devi L., Raghavendran V., Prabhu B. M., Avadhani N. G., Anandatheerthavarada H. K. (2008) Mitochondrial import and accumulation of α-synuclein impair complex I in human dopaminergic neuronal cultures and Parkinson disease brain. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9089–9100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Auluck P. K., Caraveo G., Lindquist S. (2010) α-Synuclein. Membrane interactions and toxicity in Parkinson disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26, 211–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burré J., Sharma M., Tsetsenis T., Buchman V., Etherton M. R., Südhof T. C. (2010) α-Synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science 329, 1663–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nemani V. M., Lu W., Berge V., Nakamura K., Onoa B., Lee M. K., Chaudhry F. A., Nicoll R. A., Edwards R. H. (2010) Increased expression of α-synuclein reduces neurotransmitter release by inhibiting synaptic vesicle reclustering after endocytosis. Neuron 65, 66–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chinta S. J., Mallajosyula J. K., Rane A., Andersen J. K. (2010) Mitochondrial α-synuclein accumulation impairs complex I function in dopaminergic neurons and results in increased mitophagy in vivo. Neurosci. Lett. 486, 235–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Loeb V., Yakunin E., Saada A., Sharon R. (2010) The transgenic overexpression of α-synuclein and not its related pathology associates with complex I inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 7334–7343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dauer W., Kholodilov N., Vila M., Trillat A. C., Goodchild R., Larsen K. E., Staal R., Tieu K., Schmitz Y., Yuan C. A., Rocha M., Jackson-Lewis V., Hersch S., Sulzer D., Przedborski S., Burke R., Hen R. (2002) Resistance of α -synuclein null mice to the parkinsonian neurotoxin MPTP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 14524–14529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klivenyi P., Siwek D., Gardian G., Yang L., Starkov A., Cleren C., Ferrante R. J., Kowall N. W., Abeliovich A., Beal M. F. (2006) Mice lacking α-synuclein are resistant to mitochondrial toxins. Neurobiol. Dis. 21, 541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Martin L. J., Pan Y., Price A. C., Sterling W., Copeland N. G., Jenkins N. A., Price D. L., Lee M. K. (2006) Parkinson disease α-synuclein transgenic mice develop neuronal mitochondrial degeneration and cell death. J. Neurosci. 26, 41–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsu L. J., Sagara Y., Arroyo A., Rockenstein E., Sisk A., Mallory M., Wong J., Takenouchi T., Hashimoto M., Masliah E. (2000) α-Synuclein promotes mitochondrial deficit and oxidative stress. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 401–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Parihar M. S., Parihar A., Fujita M., Hashimoto M., Ghafourifar P. (2008) Mitochondrial association of α-synuclein causes oxidative stress. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 1272–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kamp F., Exner N., Lutz A. K., Wender N., Hegermann J., Brunner B., Nuscher B., Bartels T., Giese A., Beyer K., Eimer S., Winklhofer K. F., Haass C. (2010) Inhibition of mitochondrial fusion by α-synuclein is rescued by PINK1, Parkin, and DJ-1. EMBO J. 29, 3571–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Winslow A. R., Chen C. W., Corrochano S., Acevedo-Arozena A., Gordon D. E., Peden A. A., Lichtenberg M., Menzies F. M., Ravikumar B., Imarisio S., Brown S., O'Kane C. J., Rubinsztein D. C. (2010) α-Synuclein impairs macroautophagy. Implications for Parkinson disease. J. Cell Biol. 190, 1023–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nakamura K., Nemani V. M., Azarbal F., Skibinski G., Levy J. M., Egami K., Munishkina L., Zhang J., Gardner B., Wakabayashi J., Sesaki H., Cheng Y., Finkbeiner S., Nussbaum R. L., Masliah E., Edwards R. H. (2011) Direct membrane association drives mitochondrial fission by the Parkinson disease-associated protein α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 20710–20726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Albani D., Peverelli E., Rametta R., Batelli S., Veschini L., Negro A., Forloni G. (2004) Protective effect of TAT-delivered α-synuclein. Relevance of the C-terminal domain and involvement of HSP70. FASEB J. 18, 1713–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brini M. (2008) Calcium-sensitive photoproteins. Methods 46, 160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rizzuto R., Brini M., Bastianutto C., Marsault R., Pozzan T. (1995) Photoprotein-mediated measurement of calcium ion concentration in mitochondria of living cells. Methods Enzymol. 260, 417–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rizzuto R., Brini M., Murgia M., Pozzan T. (1993) Microdomains with high Ca2+ close to IP3-sensitive channels that are sensed by neighboring mitochondria. Science 262, 744–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rapizzi E., Pinton P., Szabadkai G., Wieckowski M. R., Vandecasteele G., Baird G., Tuft R. A., Fogarty K. E., Rizzuto R. (2002) Recombinant expression of the voltage-dependent anion channel enhances the transfer of Ca2+ microdomains to mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 159, 613–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brini M., Marsault R., Bastianutto C., Alvarez J., Pozzan T., Rizzuto R. (1995) Transfected aequorin in the measurement of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c). A critical evaluation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 9896–9903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barrero M. J., Montero M., Alvarez J. (1997) Dynamics of [Ca2+] in the endoplasmic reticulum and cytoplasm of intact HeLa cells. A comparative study. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27694–27699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Duchen M. R., Surin A., Jacobson J. (2003) Imaging mitochondrial function in intact cells. Methods Enzymol. 361, 353–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nerem R. M., Levesque M. J., Cornhill J. F. (1981) Vascular endothelial morphology as an indicator of the pattern of blood flow. J. Biomech. Eng. 103, 172–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dagda R. K., Cherra S. J., 3rd, Kulich S. M., Tandon A., Park D., Chu C. T. (2009) Loss of PINK1 function promotes mitophagy through effects on oxidative stress and mitochondrial fission. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 13843–13855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Brito O. M., Scorrano L. (2008) Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature 456, 605–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manders E. M., Verbeek F. J., Aten J. A. (1993) Measurement of colocalization of objects in dual-color confocal images. J. Microsc. 169, 375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rizzuto R., Pinton P., Carrington W., Fay F. S., Fogarty K. E., Lifshitz L. M., Tuft R. A., Pozzan T. (1998) Close contacts with the endoplasmic reticulum as determinants of mitochondrial Ca2+ responses. Science 280, 1763–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakamura K., Nemani V. M., Wallender E. K., Kaehlcke K., Ott M., Edwards R. H. (2008) Optical reporters for the conformation of α-synuclein reveal a specific interaction with mitochondria. J. Neurosci. 28, 12305–12317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cárdenas C., Miller R. A., Smith I., Bui T., Molgó J., Müller M., Vais H., Cheung K. H., Yang J., Parker I., Thompson C. B., Birnbaum M. J., Hallows K. R., Foskett J. K. (2010) Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell 142, 270–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koopman W. J., Verkaart S., Visch H. J., van der Westhuizen F. H., Murphy M. P., van den Heuvel L. W., Smeitink J. A., Willems P. H. (2005) Inhibition of complex I of the electron transport chain causes O[bardot,2]-mediated mitochondrial outgrowth. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C1440–C1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leng Y., Chuang D. M. (2006) Endogenous α-synuclein is induced by valproic acid through histone deacetylase inhibition and participates in neuroprotection against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 26, 7502–7512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gitler A. D., Bevis B. J., Shorter J., Strathearn K. E., Hamamichi S., Su L. J., Caldwell K. A., Caldwell G. A., Rochet J. C., McCaffery J. M., Barlowe C., Lindquist S. (2008) The Parkinson disease protein α-synuclein disrupts cellular Rab homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 145–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li W., West N., Colla E., Pletnikova O., Troncoso J. C., Marsh L., Dawson T. M., Jäkälä P., Hartmann T., Price D. L., Lee M. K. (2005) Aggregation promoting C-terminal truncation of α-synuclein is a normal cellular process and is enhanced by the familial Parkinson disease-linked mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2162–2167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hettiarachchi N. T., Parker A., Dallas M. L., Pennington K., Hung C. C., Pearson H. A., Boyle J. P., Robinson P., Peers C. (2009) α-Synuclein modulation of Ca2+ signaling in human neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells. J. Neurochem. 111, 1192–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Furukawa K., Matsuzaki-Kobayashi M., Hasegawa T., Kikuchi A., Sugeno N., Itoyama Y., Wang Y., Yao P. J., Bushlin I., Takeda A. (2006) Plasma membrane ion permeability induced by mutant α-synuclein contributes to the degeneration of neural cells. J. Neurochem. 97, 1071–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marongiu R., Spencer B., Crews L., Adame A., Patrick C., Trejo M., Dallapiccola B., Valente E. M., Masliah E. (2009) Mutant Pink1 induces mitochondrial dysfunction in a neuronal cell model of Parkinson disease by disturbing calcium flux. J. Neurochem. 108, 1561–1574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Szabadkai G., Bianchi K., Várnai P., De Stefani D., Wieckowski M. R., Cavagna D., Nagy A. I., Balla T., Rizzuto R. (2006) Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J. Cell Biol. 175, 901–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Csordás G., Hajnóczky G. (2009) SR/ER-mitochondrial local communication. Calcium and ROS. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 1352–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rizzuto R., Marchi S., Bonora M., Aguiari P., Bononi A., De Stefani D., Giorgi C., Leo S., Rimessi A., Siviero R., Zecchini E., Pinton P. (2009) Ca2+ transfer from the ER to mitochondria. When, how. and why. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 1342–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. de Brito O. M., Scorrano L. (2010) An intimate liaison: spatial organization of the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria relationship. EMBO J. 29, 2715–2723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Park S. M., Jung H. Y., Kim T. D., Park J. H., Yang C. H., Kim J. (2002) Distinct roles of the N-terminal binding domain and the C-terminal-solubilizing domain of α-synuclein, a molecular chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28512–28520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ulrih N. P., Barry C. H., Fink A. L. (2008) Impact of Tyr to Ala mutations on α-synuclein fibrillation and structural properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1782, 581–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Szabadkai G., Simoni A. M., Chami M., Wieckowski M. R., Youle R. J., Rizzuto R. (2004) Drp-1-dependent division of the mitochondrial network blocks intraorganellar Ca2+ waves and protects against Ca2+-mediated apoptosis. Mol. Cell 16, 59–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jin J., Li G. J., Davis J., Zhu D., Wang Y., Pan C., Zhang J. (2007) Identification of novel proteins associated with both α-synuclein and DJ-1. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 845–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burbulla L. F., Schelling C., Kato H., Rapaport D., Woitalla D., Schiesling C., Schulte C., Sharma M., Illig T., Bauer P., Jung S., Nordheim A., Schöls L., Riess O., Krüger R. (2010) Dissecting the role of the mitochondrial chaperone mortalin in Parkinson disease. Functional impact of disease-related variants on mitochondrial homeostasis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 4437–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Arduíno D. M., Esteves A. R., Cardoso S. M., Oliveira C. R. (2009) Endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria interplay mediates apoptotic cell death. Relevance to Parkinson disease. Neurochem. Int. 55, 341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Calì T., Ottolini D., Brini M. (2011) Mitochondria, calcium, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in Parkinson disease. Biofactors 37, 228–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gorbatyuk O. S., Li S., Nash K., Gorbatyuk M., Lewin A. S., Sullivan L. F., Mandel R. J., Chen W., Meyers C., Manfredsson F. P., Muzyczka N. (2010) In vivo RNAi-mediated α-synuclein silencing induces nigrostriatal degeneration. Mol. Ther. 18, 1450–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]