Abstract

In the present retrospective study, we tested the hypothesis that neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) as a treatment for patients with colorectal carcinoma liver metastases (CRLM) may reduce intrahepatic micrometastases. The incidence and distribution of intrahepatic micrometastases were determined in specimens resected from 63 patients who underwent hepatectomy for CRLM (21 treated with NAC and 42 without). In addition, the therapeutic efficacy of NAC was evaluated histologically. Intrahepatic micrometastases were defined as microscopic lesions spatially separated from the gross tumor. The distance from these lesions to the border of the hepatic tumor was measured on histological specimens and the density of intrahepatic micrometastases (number of lesions/mm2) was determined in regions close to (<1 cm) the gross hepatic tumor. Of the 21 patients treated with NAC, 13 were identified as having a partial response according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines; thus, the overall response rate was 62%. Histologic evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of NAC was significantly associated with tumor response to NAC according to the RECIST guidelines (p=0.048). In all, 260 intrahepatic micrometastases were detected in 39 patients (62%). Intrahepatic micrometastases were less frequently detected in NAC-treated patients than in untreated patients (5/21 [24%] vs. 34/42 [81%], respectively; p<0.001). There were no significant differences in the distance and density of intrahepatic micrometastases between the two groups (p=0.313 and p=0.526, respectively). In conclusion, NAC reduces the incidence of intrahepatic micrometastases in patients with CRLM, but NAC has no significant effect on their distribution when intrahepatic micrometastases are present.

Keywords: Liver neoplasms, colorectal metastases, intrahepatic micrometastases, immunohistochemistry, surgical resection, hepatectomy margin

Introduction

Hepatectomy offers the hope of a cure in selected patients with colorectal carcinoma liver metastases (CRLM) and is currently recognized as the standard of care [1,2]. The established consensus is that a negative hepatectomy margin decreases the rate of local recurrence and improves survival [3-6]. However, the hepatectomy margin status can be influenced by the resection line chosen by the surgeon during the procedure, as well as the spread of the cancer. Recent evidence indicates an increasing trend of the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in patients with resectable CRLM [7-9] with the aim of providing sufficient time before surgery to assess tumor biology, to treat occult metastases, and thus, to decrease the radicality of the resection [8]. However, the incidence and distribution of intrahepatic micrometastases in patients treated with NAC prior to hepatectomy for CRLM have not yet been investigated.

The incidence and distribution of intrahepatic micrometastases are influenced by the number and location of tissue sections examined. Therefore, in the present study we evaluated the density of intrahepatic micrometastases (number of lesions/mm2) in the areas surrounding the advancing border of gross hepatic tumors. Our hypothesis was that NAC as a treatment for patients with CRLM may reduce intrahepatic micrometastases. To address this, we investigated the incidence and distribution of intrahepatic micrometastases in specimens resected from patients treated with or without NAC for CRLM.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between January 2005 and December 2011, 68 consecutive Japanese patients with CRLM underwent radical resection with curative intent at Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital (Niigata, Japan). Five patients who underwent repeat hepatectomy for intrahepatic recurrences were excluded from the data analysis. Thus, 63 patients formed the study group (45 men and 18 women; median age 67 years; age range 33-83 years). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital.

Of the 63 patients included in the study, 21 were treated with NAC prior to hepatectomy for CRLM. The NAC agents used were 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan alone or as part of combination regimens (i.e. FOLFOX or FOLFIRI). Nine patients also received targeted therapy, such as bevacizumab directed against vascular endothelial growth factor [10]. The primary tumor location was the colon in 37 patients and the rectum in the remaining 26. According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual [11], at the time of colorectal resection three patients had Stage I tumors, 16 had Stage II tumors, 12 had Stage III tumors, and 32 had Stage IV tumors. Twenty-seven patients had synchronous liver metastases and 36 had metachronous liver metastases. Synchronous liver metastases were defined as those found simultaneously with the primary tumor or detected within 1 month of resection of the primary colorectal tumor; in contrast, metachronous liver metastases were defined as those found later than 1 month after primary colorectal surgery. Of the 27 patients with synchronous liver metastases, five underwent simultaneous resection for both colorectal primary and liver secondary tumors. The distribution of liver metastases was unilobar in 41 patients and bilobar in 22. The median serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level prior to hepatectomy was 10.2 ng/mL (range 1.6-987.2 ng/mL). None of the patients received ablation therapy before the hepatectomy. The response to NAC was assessed by contrast-enhanced spiral computed tomography (CT) and was evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guidelines [12].

The extent of hepatic resection was categorized according to the number of Couinaud segments resected (<3 vs. ≥ 3), whereas the type of hepatic resection was either anatomic or nonanatomic [5]. The hepatectomy procedure was individualized for each patient on the basis of hepatic tumor status (size, number, location) and the patient’s general condition. Nonanatomic partial hepatectomy was more likely to be performed in patients with small or subcapsular tumors, whereas patients with larger tumors, more deeply located tumors, or those with a better general condition tended to undergo more extensive hepatectomy procedures.

Pathologic evaluation

Resected specimens were submitted to the Department of Surgical Pathology, Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital for histologic evaluation to determine the number of hepatic tumors, the size of the largest tumor, histologic tumor grade, the mode of intrahepatic micrometastases, and the hepatectomy margin status. In 1986, our institution established uniform standards for the final histopathologic description of liver tumors. The liver analysis technique used herein has been standardized over the 25 years since 1986 until the end of the present study (December 2011) and includes a numerical description of the margin width in millimeters. In the present series, 146 hepatic tumors were resected. Thirty patients had a solitary tumor, whereas 33 had multiple tumors. Hepatic deposits were quantified in each patient by preoperative imaging and macroscopic examination of multiple slices from resected specimens, not including satellite lesions, according to the criteria of Taylor et al [13]. The largest hepatic tumors ranged in size from 0.5 to 9.8 cm (median 2.8 cm). All patients had adenocarcinoma. The hepatic tumors were well differentiated in three patients, moderately differentiated in 55, and poorly differentiated in five. The histologic grade applied to the hepatic tumor was determined on the basis of areas with the highest grade. The therapeutic efficacy of NAC was evaluated histologically according to the Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma [14]. The response to NAC was evaluated histologically and was classified as either Grade 0 (no effect), Grade 1 (mild effect), Grade 2 (moderate effect), or Grade 3 (marked effect) [14]. Hepatectomy margin status was determined histologically as either R0 (no residual tumor) or R1 (microscopic residual tumor) on the basis of the absence or presence of histologically verified tumor cells on the hepatectomy margin, respectively. For hepatectomy margins determined to be R0, the actual width of the hepatectomy margin was measured histologically for each resected specimen. For hepatectomy margins determined to be R1, the width of the hepatectomy margin was recorded as 0 cm. In patients with multiple tumors, the closest margin was recorded as representative.

Multiple tissue blocks were cut from the advancing margin of the largest hepatic tumor in each patient, with a median of six paraffin blocks (range 2-31 blocks) per patient. Lymphatic and blood vessels were distinguished immunohistochemically using a specific marker for lymphatic vessels (D2-40 monoclonal antibody; SIG-730, 1:200 dilution; Signet Laboratories, Dedham, MA, USA) and a panendothelial marker for both blood and lymphatic vessels (CD34 monoclonal antibody; 1:200 dilution; DakoCytomation, Denmark), as described previously [4,5]. Four serial 3 μm sections were recut and prepared from each block: one for hematoxylin-eosin staining, one for immunohistochemical staining with the D2-40 monoclonal antibody, one for immunohistochemical staining with the CD34 monoclonal antibody, and one as a negative control. Intrahepatic micrometastases were defined as any microscopic lesions separated from the gross tumor by a rim of nonneoplastic liver parenchyma. Macroscopic hepatic lesions detected on preoperative imaging, during surgery, or by inspection of resected specimens were excluded. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokeratin-20 was not used in the present study to identify intrahepatic micrometastases.

We analyzed the distribution of intrahepatic micrometastases in resected specimens from the number and mode of intrahepatic micrometastases as well as distances between the advancing border of gross hepatic tumors and each of the intrahepatic micrometastases. The density of intrahepatic micrometastases (number of lesions/mm2) was calculated according to the area surrounding the advancing border of gross hepatic tumor, in both close (<1 cm) and distant (≥ 1 cm) zones, as described previously [5].

Statistical analysis

Medical records and survival data were obtained for all 63 patients. The cut-off levels for patient age (65 years) and the size of the largest hepatic tumor (3 cm) were determined based on respective median values. The cut-off value for preoperative serum CEA (5 ng/mL) was determined on the basis of a reference range of serum CEA levels of ≤5 ng/mL. Categorical variables were compared by Fisher’s exact test or the Pearson Χ2 test, whereas continuous variables were compared by the Mann- Whitney U-test. All statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics 17 (SPSS Japan, Tokyo, Japan). All tests were two tailed and p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinicopathologic characteristics according to NAC

Of the 63 patients in the present study, 21 were treated with NAC prior to hepatectomy for CRLM and 42 were not. Compared with patients who did not receive NAC, patients treated with NAC were characterized by a more advanced AJCC stage of the primary colorectal tumor (p=0.001) and a higher incidence of synchronous liver metastases (p<0.001) and multiple liver metastases (p<0.001; Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics according to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

| Without NAC | With NAC | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (≤65/>65 years) | 20/22 | 11/10 | 0.793 |

| Gender (M/F) | 32/10 | 13/8 | 0.253 |

| Serum CEA before hepatectomy (≤5/>5 ng/mL) | 12/30 | 8/13 | 0.567 |

| Location of the primary tumor (colon/rectum) | 23/19 | 14/7 | 0.424 |

| Stage* of primary colorectal tumor (I-II/III-IV) | 18/24 | 1/20 | 0.001 |

| Timing of detection of liver metastases (synchronous/metachronous) | 10/32 | 17/4 | <0.001 |

| Distribution of liver metastases (unilobar/bilobar) | 31/11 | 10/11 | 0.052 |

| Extent of hepatic resection (<3/≥3 segments) | 23/19 | 10/11 | 0.606 |

| Type of hepatic resection (anatomic/non-anatomic) | 32/10 | 19/2 | 0.307 |

| Hepatectomy margin status (0/<1/≥1 cm) | 1/28/13 | 0/17/4 | 0.441 |

| No. liver metastases (solitary/multiple) | 26/16 | 4/17 | 0.002 |

| Size of the largest hepatic tumor (≤3/>3 cm) | 24/18 | 13/8 | 0.790 |

| Histologic grade* of liver metastases (G1/G2/G3) | 2/38/2 | 1/17/3 | 0.418 |

| Intrahepatic micrometastases (absent/present) | 8/34 | 16/5 | <0.001 |

Data show the number of patients in each group.

The staging and grading of tumors was according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual [11].

Abbreviations: NAC (neoadjuvant chemotherapy); CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen)

Using the RECIST guidelines, we determined that, of the 21 patients treated with NAC, one had progressive disease, seven had stable disease, and 13 exhibited a partial response (Table 2). Thus, the overall response rate for these patients was 62%. Histologic evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of NAC was significantly associated with tumor response to NAC according to the RECIST guidelines (p=0.048; Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between histologic therapeutic efficacy and tumor response in 21 patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy

| Histologic evaluation of therapeutic efficacy | CR | PR | SD | PD | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0.048 |

| Grade 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | |

| Grade 2 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Grade 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Data show the number of patients in each group. The therapeutic efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was evaluated histologically according to the Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma [14] as follows: Grade 0, no effect; Grade 1, mild effect; Grade 2, moderate effect; Grade 3, marked effect. Abbreviations: CR (complete response); PR (partial response); SD (stable disease); PD (progressive disease)

Detection of intrahepatic micrometastasis

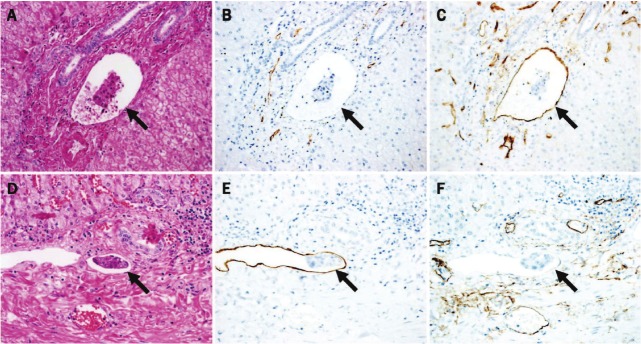

In all, 260 intrahepatic micrometastases were detected in 39 of 63 patients (62%). Intrahepatic micrometastases were less frequently detected in NAC-treated patients than in untreated patients (5/21 [24%] vs. 34/42 [81%], respectively; p<0.001; Table 1). The mode of intrahepatic micrometastases included portal venous invasion (52 lesions; Figure 1A-C), hepatic venous invasion (58 lesions), sinusoidal invasion (86 lesions), intrahepatic lymphatic invasion (16 lesions, Figure 1D-F), bile duct invasion (14 lesions), and stromal invasion of the portal tracts (34 lesions). The number of intrahepatic micrometastases ranged from 1 to 22 (median six per patient). Distances from the advancing border of gross hepatic tumors to each intrahepatic micrometastasis ranged between 0.1 and 17 mm (median 2 mm). Intrahepatic micrometastases occurred more frequently in the zone close to (<1 cm) the gross hepatic tumor (255/260 lesions; 98%) than in the distant (≥ 1 cm) zone (5/260 lesions; 2%). For the 39 patients with intrahepatic micrometastases, the mean density of intrahepatic micrometastases in the close (<1 cm) zone was 77.5 x 10–4 lesions/mm2.

Figure 1.

(A-C) Portal venous invasion and (D-F) lymphatic invasion within the portal tracts. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining. Tumor cell clusters (arrow) at the advancing border of portal tract invasion are clearly visible within a vessel that is accompanied by arteries and bile ductules. (B) Immunohistochemical staining with the D2-40 monoclonal antibody reveals tumor cell clusters clearly outlined by endotherial cells showing no D2-40 immunoreactivity, indicating portal venous invasion (arrow). (C) Immunohistochemical staining with an anti-CD34 monoclonal antibody reveals tumor cell clusters clearly outlined by CD34-immunopositive endotherial cells (arrow). (D) Hematoxylin-eosin staining. Tumor cell clusters (arrows) at the advancing border of portal tract invasion are clearly visible within a vessel that is accompanied by bile ductules. (E) Immunohistochemical staining with the D2-40 monoclonal antibody reveals tumor cell clusters clearly outlined by D2-40-immunopositive endothelial cells, indicating lymphatic invasion (arrow). (F) Immunohistochemical staining with an anti-CD34 monoclonal antibody reveals tumor cell clusters clearly outlined by endotherial cells showing no CD34 immunoreactivity (arrow). (original magnification; A-C: x 250; D-F: x 300).

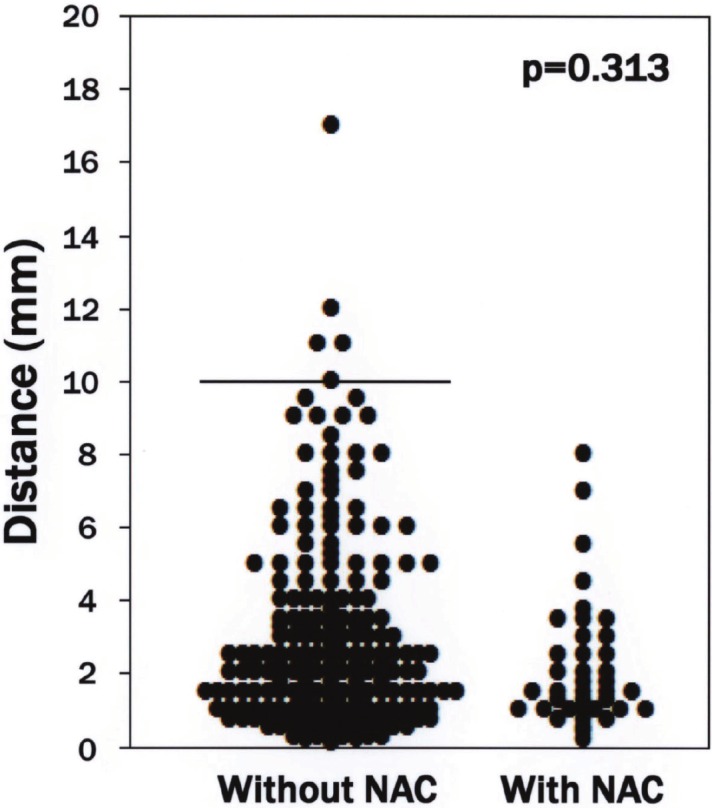

Distribution of intrahepatic micrometastasis according to NAC

The median distance from the advancing border of gross hepatic tumors to each intrahepatic micrometastasis in patients who were not treated with NAC was 2.25 mm (range 0.1-17 mm), compared with 1.5 mm (range 0.2-8 mm) in NAC-treated patients. There was no significant difference in the distance between the intrahepatic micrometastases and the advancing border of gross hepatic tumors between the two groups (p=0.313; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of cases based on distance between the advancing border of gross hepatic tumors and each intrahepatic micrometastasis. The median distance from the advancing border of gross hepatic tumors to each intrahepatic micrometastasis was not apparently different between patients treated with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy (p=0.313). Bar indicates 10 mm. Abbreviations: NAC (neoadjuvant chemotherapy).

The mean density of intrahepatic micrometastases in the zone close to (<1 cm) the gross hepatic tumor in patients treated with and without NAC was 87.7 x 10–4 and 75.9 x 10–4 lesions/mm2, respectively. There was no significant difference in the density of intrahepatic micrometastases in the close (<1 cm) zone between the two groups (p=0.526).

Discussion

Current evidence suggests that NAC may provide survival benefits in patients with CRLM [7-9]. However, there is little information in the literature regarding the incidence and distribution of intrahepatic micrometastases in patients treated with NAC prior to hepatectomy for CRLM. Thus, in the present study we investigated the incidence and distribution of intrahepatic micrometastases in specimens resected from patients treated with or without NAC for CRLM. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate that NAC reduces the incidence of intrahepatic micrometastases in patients with CRLM. However, when intrahepatic micrometastases are present, their distribution is not affected by NAC.

The incidence of intrahepatic micrometastases reported in previous studies varies widely, ranging from 31% to 70% [4,5,15-18]. In the present study, the incidence of intrahepatic micrometastases was lower in patients treated with NAC, despite these patients being at a more advanced stage of CRLM (Table 1). Furthermore, histologic evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of NAC revealed a significant association between tumor response and NAC (Table 2). Together, these findings suggest that NAC reduces the risk of cancer spread in the liver in patients with CRLM.

The theoretical mechanisms underlying the intrahepatic spread of CRLM include metastasis from the primary colorectal site and remetastasis from existing liver metastases. Metastasis to the liver from a colorectal primary tumor is usually hematogenous, whereas intrahepatic lymphatic invasion is in effect lymphatic “remetastasis” from liver metastases (Figure 1D-F) [4,5]. In the present series, 98% of intrahepatic micrometastases were located in the zone close to (<1 cm) the gross hepatic tumor, with the mean density of intrahepatic micrometastases in this zone being 77.5 x 10–4 lesions/mm2. These values are similar to those reported previously, namely an incidence of 95% and a mean density in the zone close to the hepatic tumor of 74.8 x 10–4 lesions/mm2 [5]. Furthermore, stratification according to NAC administered prior to hepatectomy revealed that when intrahepatic micrometastases are present, NAC has no effect on their distribution (Figure 2). Thus, theoretically, a 1-cm hepatectomy margin would eradicate the majority of intrahepatic micrometastases present within the resected domain. Because the status of intrahepatic micrometastases cannot be evaluated accurately before hepatectomy, the currently recommended ≥ 1 cm hepatectomy margin should remain the goal for resections of CRLM when feasible, even in patients treated with NAC prior to hepatectomy for CRLM [4-6].

The two main limitations of the present study are the retrospective analysis of a small number of patients and the range of different anticancer agents administered to some patients. However, we believe that these limitations do not greatly affect the results of the study because the differences between groups were too marked to have resulted from any potential bias.

In conclusion, NAC reduces the incidence of intrahepatic micrometastases in patients with CRLM. However, NAC has no significant effect on the distribution of intrahepatic micrometastases when they are present.

References

- 1.Fong Y, Cohen AM, Fortner JG, Enker WE, Turnbull AD, Coit DG, Marrero AM, Prasad M, Blumgart LH, Brennan MF. Liver resection for colorectal metastases. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997;15:938–946. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khatri VP, Petrelli NJ, Belghiti J. Extending the frontiers of surgical therapy for hepatic colorectal metastases: is there a limit? J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:8490–8499. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.6155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawlik TM, Scoggins CR, Zorzi D, Abdalla EK, Andres A, Eng C, Curley SA, Loyer EM, Muratore A, Mentha G, Capussotti L, Vauthey JN. Effect of surgical margin status on survival and site of recurrence after hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2005;241:715–724. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000160703.75808.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korita PV, Wakai T, Shirai Y, Sakata J, Takizawa K, Cruz PV, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Intrahepatic lymphatic invasion independently predicts poor survival and recurrences after hepatectomy in patients with colorectal carcinoma liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3472–3480. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakai T, Shirai Y, Sakata J, Valera VA, Korita PV, Akazawa K, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Appraisal of 1 cm hepatectomy margins for intrahepatic micrometastases in patients with colorectal carcinoma liver metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2472–2481. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhir M, Lyden ER, Wang A, Smith LM, Ullrich F, Are C. Influence of margins on overall survival after hepatic resection for colorectal metastasis: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2011;254:234–242. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318223c609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benoist S, Nordlinger B. The role of preoperative chemotherapy in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2385–2390. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0492-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chua TC, Saxena A, Liauw W, Kokandi A, Morris DL. Systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized trials of the clinical response and outcomes of neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy for resectable colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:492–501. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0781-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehmann K, Rickenbacher A, Weber A, Pestalozzi BC, Clavien PA. Chemotherapy before liver resection of colorectal metastases: friend or foe? Ann Surg. 2012;255:237–247. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182356236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F, Couture F, Sirzén F, Cassidy J. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:2013–2019. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th edition. Fleming ID, editor. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor M, Forster J, Langer B, Taylor BR, Greig PD, Mahut C. A study of prognostic factors for hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Am J Surg. 1997;173:467–471. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugihara K, editor. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum: Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma. 2nd English edition. Tokyo: Kanehara; 2009. pp. 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nanko M, Shimada H, Yamaoka H, Tanaka K, Masui H, Matsuo K, Ike H, Oki S, Hara M. Micrometastatic colorectal cancer lesions in the liver. Surg Today. 1998;28:707–713. doi: 10.1007/BF02484616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sasaki A, Aramaki M, Kawano K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Kitano S. Prognostic significance of intrahepatic lymphatic invasion in patients with hepatic resection due to metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:105–111. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ambiru S, Miyazaki M, Isono T, Ito H, Nakagawa K, Shimizu H, Kusashio K, Furuya S, Nakajima N. Hepatic resection for colorectal metastases: analysis of prognostic factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:632–639. doi: 10.1007/BF02234142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yokoyama N, Shirai Y, Ajioka Y, Nagakura S, Suda T, Hatakeyama K. Immunohistochemically detected hepatic micrometastases predict a high risk of intrahepatic recurrence after resection of colorectal carcinoma liver metastases. Cancer. 2002;94:1642–1647. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]