Abstract

Objective

Several stress-related states and conditions that are considered to involve sympathetic over-activation are accompanied by increased circulating levels of inflammatory immune markers. Prolonged sympathetic over-activity involves increased stimulation of the β-adrenergic receptor. While prior research suggests that one mechanism by which sympathetic stimulation may facilitate inflammation is via β-adrenergic receptor activation, little work has focused on the relationship between circulating inflammatory immune markers and β-adrenergic receptor function within the human body (in vivo). We examined whether decreased β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity, an indicator of prolonged β-adrenergic over-activation and a physiological component of chronic stress, is related to elevated levels of inflammatory immune markers.

Methods

Ninety-three healthy participants aged 19–51 years underwent the chronotropic 25 dose (CD25) isoproterenol test to determine in vivo β-adrenergic receptor function. Circulating levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (sTNF-R1) were determined.

Results

β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity was lower in people with higher CRP concentrations (r = .326, P = 0.003). That relationship remained significant after controlling for socio-demographic and health variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), leisure-time exercise (LTE) and smoking status. No significant relationship was found between CD25 and IL-6 or sTNF-R1.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates a link between in vivo β-adrenergic receptor function and circulating inflammatory immune markers in humans. Future studies in specific disease states may be promising.

Keywords: β-adrenergic receptor, chronotropic 25 dose, C-reactive protein, cytokines, inflammation, isoproterenol

INTRODUCTION

Sympathetic over-activity has been related to a wide range of pathological states and conditions. Prolonged sympathetic over-activity involves increased stimulation of the β-adrenergic receptor which leads to reduced β-adrenergic receptor function (1–4). Altered β-adrenergic receptor function has been implicated in the pathophysiology of ischemic heart disease, heart failure, metabolic syndrome and hypertension (1, 5–10) and is considered a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) by increasing myocardial energy production, oxidative stress and enhancing apoptotic pathways (4). Prolonged β-adrenergic stimulation, indicated by decreased in vitro or in vivo assessed β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity (3, 11), has also been related to psychopathological factors such as anxiety, prolonged life stressors, hostility, depression, as well as the procoagulant response to acute stressors (12–19). CVD and numerous of the above mentioned states and conditions are related to stress. Thus, prolonged β-adrenergic stimulation–accompanied by down regulation of β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity – has been considered a physiological component of chronic stress resulting from chronically increased stress hormones (i.e. catecholamines) (3, 11, 20).

Increased inflammatory immune markers are frequently observed in states and conditions associated with sympathetic over-activity. For example, C-reactive protein (CRP), an acute phase protein which is considered a stable marker for inflammation, has been related to increased risk for CVD, hypertension and metabolic syndromes (21–24). Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α affect CRP production (25, 26) and have also been linked to CVD as well as Alzheimer’s disease and cancer (27–29). In addition, stressful experiences, negative emotions and symptoms of depression and anxiety have been associated with elevated levels of CRP and pro-inflammatory cytokines (30–33). Because of bidirectional relationships between depression/anxiety and CVD, immunological dysregulation has been considered a possible link between mood disorders and CVD (34–36).

Increased concentrations of inflammatory markers in clinical conditions may in part result from sympathetic over-activation. Prolonged sympathetic activation, accompanied by altered catecholamine and glucocorticoid circulation, facilitates inflammation through the induction of cytokines, CRP and the activation of the corticotrophin-releasing hormone/substance P/histamine axis (25). Altered β-adrenergic receptor function may be one sympathetic factor that underlies such a dysfunctional sympathetic immune interface. The β-adrenergic receptor group consists of three subtypes (β1, β2, β3 ;28) and mediates several catecholamine-induced end organ sympathetic responses such as vasodilatation and heart rate increase, but also a variety of immune functions including immune cell trafficking, adhesion, and increased pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion due to the adrenergic receptor activation of leukocytes and adipocytes (3, 11, 37–41). A pro-inflammatory effect of β-adrenergic receptor activation is suggested by in vitro findings demonstrating that pro-inflammatory responses in human monocytes are mediated by a β-adrenergic mechanism (42). Additionally, research in rodents found that chronic β-adrenergic stimulation using isoproterenol, a non-selective β-adrenergic receptor agonist, is sufficient to induce pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (43, 44) and that the intra-cerebroventricular application of isoproterenol induces IL-1β mRNA in several regions of the rat brain (45). In clinical samples, the link between β-adrenergic receptor function and inflammation was suggested by studies showing that β-blocker treatment reduces CRP concentrations in coronary heart disease (46) as well as after acute myocardial infarction (47). Finally, CRP concentrations in twins were predicted by genetic variants in the catecholaminergic/β-adrenergic pathway (48).

β-adrenergic responsiveness has frequently been assessed in vitro by measuring isoproterenol-induced cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production in human lymphocytes (49, 50). Studies using this technique reveal associations of lymphocyte β-adrenergic receptor function with tension-anxiety, prolonged stressors, hostility, depression, as well as the procoagulant response to acute stressors (12–17). However, there are limitations to using in vitro assessment as an indicator for human β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity. β-adrenergic receptor function in lymphocytes indicate the ratio of isoproterenol-stimulated cAMP to basal cAMP on lymphocytes, but does not directly reflect the in vivo status because the neurohormonal environment of a peripheral cell receptor such as on lymphocytes may differ from a post-synaptic cell receptor (3). Moreover, although under basal conditions β-adrenergic receptor function in lymphocytes may reflect β-adrenergic receptor function within the body, the validity of β-adrenergic receptor function in lymphocytes can be undermined because stressors and sympathetic arousal may stimulate a redistribution of lymphocyte subsets, due to a partially β-adrenergic mediated release of lymphocytes from the spleen and lymphatic notes (49–52).

One technique for measuring β-adrenergic receptor function in vivo involves assessing the chronotropic 25 dose (CD25). CD25 refers to the dose of isoproterenol, which is necessary to increase heart rate by 25 beats per minute. Low CD25 values indicate high receptor sensitivity (49, 53). Correlational studies indicate an inverse relationship between CD25 and lymphocyte β-adrenergic sensitivity (54). Studies using the CD25 method in humans have found relationships of β-adrenergic receptor function with Type A behavior pattern, anxiety, hostility as well as decreased maximal heart rate with aging (55–60).

While prior studies suggest that β-adrenergic receptor manipulation alters immune parameters and that sympathetic nervous system abnormalities and inflammation often overlap, studies have rarely addressed the functional relationship between in vivo β-adrenergic receptor function and inflammatory markers in humans. Therefore, we examined the association of CD25 with the inflammatory markers CRP, IL-6 and sTNF-R1 in a sample of healthy unmedicated adults. We hypothesized that reduced β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity (i.e., higher chronotropic 25 dose values) is related to increased levels of CRP, IL-6 and sTNF-R1.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were healthy volunteers from a larger study on health, stress and ethnicity. The study was approved by the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Institutional Review Board. The study group for isoproterenol testing consisted of 39 women (19 African Americans and 20 white participants) and 54 men (24 African Americans and 30 whites) between 19 and 51 years (see Table 1 for sample characteristics). Participants were recruited between 2006 and 2010 using advertisements and announcements. Exclusionary criteria were: Current diagnoses of a clinical illness other than hypertension, history of psychosis or sleep disorder, current alcohol or drug abuse, moderate or heavy smoking (>10 cigarettes/day), increased caffeine intake (>600 mg/day), hormonal medication (including the contraceptive pill or hormone replacement therapy), blood pressure (BP) ≥ 170/105 mm Hg, severe obesity (class II obesity, body mass index (BMI) ≥ 35) and any medication use. Two subjects with antihypertensive medication were accepted for participation and enrolled after a 3-week drug washout period supervised by the study physician.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study group (N = 93).

| Age, years | 35.1 (9.7) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.3 (3.6) |

| Women, N (%) | 39 (41.9) |

| African Americans, N (%) | 43 (46.2) |

| White, N (%) | 50 (53.8) |

| Current smoker, N (%) | 10 (10.7) |

| Leisure-time exercise1 | 77.9 (121.3) |

| Baseline heart rate, bpm | 65.1 (10.1) |

| Mean arterial blood pressure, mmHg | 91.5 (12.0) |

| Chronotropic 25 dose, μg | 1.4 (0.8) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L1 | 0.9 (1.0) |

| Interleukin 6, pg/mL1 | 3.6 (2.5) |

| Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, pg/mL1 | 888.2 (420.5) |

Notes: Values shown as mean (SD) unless otherwise noted.

= untransformed data are displayed, statistical analyses based on log-transformed data

Procedure

After prescreening, physical examination by a physician, and giving informed consent, participants arrived between 4:00 PM and 5:00 PM at the UCSD General Clinical Research Center. The isoproterenol stimulation test was conducted in the evening between 7:00 PM and 9:00 PM. To avoid effects of pain caused by needle sticks on inflammatory parameters, all blood samples were obtained through an intravenous catheter, which was placed after arrival between 4:00 PM and 5:00 PM. To yield more reliable measures of inflammatory parameters, we used average values which resulted from analyzing 3 blood samples. Blood samples were taken in the evening at about 7:00 PM, at 10:30 PM before lights were turned off and at 6:30 AM after subjects were wakened at 6:00 AM.

Isoproterenol Stimulation Test and Chronotropic 25 Dose

Participants were connected to an electrocardiogram monitor to measure heart rate. After a 30-min rest and assessment of basal heart rate, an intravenous low-dose bolus (0.1 μg) of isoproterenol was administered to ensure that no adverse reactions to the drug occurred. Following the 0.1 μg bolus, subjects were infused with incremental bolus doses (0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 μg) until an increase of heart rate by 25 beats/min above basal heart rate was observed or until the 4.0 μg bolus was completed. The maximum heart rate after each bolus was calculated as the mean of the three shortest R-R intervals in the electrocardiogram. There was a 5-min time interval between bolus injections. Standardized calculation of CD25 values was performed as described previously (49, 53).

Immunological Measures

Plasma was stored at −80 C° until thawed for assay. CRP was assayed using the high sensitivity Denka-Seiken method (61). IL-6 and sTNF-R1 were determined using commercial ELISAs according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Quantikine, R&D Systems, MN). Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were <3% for CRP and <5% for sTNF-R1 and IL-6, respectively. Assay sensitivities were <0.05 mg/L for CRP, <0.72 pg/mL for IL-6 and <0.61 pg/mL for sTNF-R1.

Covariates

Socio-demographic and health-related variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, BMI, smoking status (smoker/non-smoker), physical activity (weekly-activity-score of the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionaire (LTE), (62)), blood pressure and heart rate (HR) may be related to β-AR function (3, 55, 56, 63, 64) and may also be confounded with concentrations of circulating inflammatory immune markers (65–69). Thus, these variables were considered as control variables in adjusted regression models.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS version 17.0 for Windows (Chicago, SPSS, Inc.). Occasional missing values occurred due to heterogeneous technical difficulties and multiple assessments. The rate of missing values for each of the three immunological measures was between 2.2 % and 7.5 % for CRP, between 6.5 % and 8.6 % for IL-6 and between 1.1 % and 7.5 % for sTNF-R1. Regarding covariates, the rate of missing values was 7.5 % for mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) and 7.5 % for LTE. CD25 values and immunological parameters above 3 standard deviations were considered to be extreme outliers and treated as missing values. The rate of extreme outliers was 3.2 % for CD25, between 3.2 % and 4.3 % for CRP measures, between 2.2 % and 6.4 % for IL-6 measures and 0.0 % for sTNF-R1 measures (Note: CRP scores indicated no potentially ongoing acute phase response since all scores were below 10 mg/L, 70).

To avoid disproportional high rates of missing data due to averaging immunological values from three assessments, missing values of single immunological assessments were replaced by multiple imputation (MI) if complete data for the two other assessments were available. MI was conducted with the use of NORM software version 2.03 (71). MI is considered a “state of the art” method to deal with missing data and is superior to traditional missing data techniques (72, 73). For the imputation process, observed data from all study variables were included. To avoid biased estimations, the MI procedure was run after exclusion of extreme outliers and missing values which were due to outliers were not imputed. Missing values for covariates (MAP and LTE) were also imputed. We conducted five imputations followed by five independent statistical analyses (74–76). Descriptive statistics and results from these five analyses were combined according to Rubin’s rules (77). Correlation coefficients were Z-transformed before combining (78) and subsequently back transformed (79). LTE values and immunological data were log-transformed before MI since these variables were not normally distributed (tested by Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests) and skewed data may bias the estimations (73, 80). After each imputation procedure, immunological data were antilog-transformed before calculating average values which were again log-transformed to reach normal distribution for further analyses.

Pearson correlation analyses were performed to examine potential bivariate associations between CD25 and inflammatory markers. Hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted to examine relationships between CD25 (step 2) and inflammatory markers (dependent variables) after adjusting for covariates (step 1). Our final regression models included 84 observations for CRP, 74 observations for IL-6 and 88 observations for sTNF-R1.

RESULTS

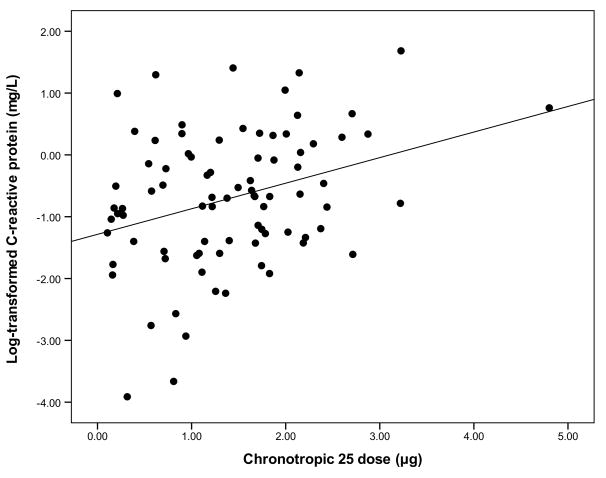

Mean values and standard deviations for demographic and biological variables are shown in Table 1. Bivariate relationships between study variables are presented in Table 2. With respect to CD25 and inflammatory markers, correlation analyses revealed a significant linear association between CD25 and CRP. Among all study variables, CRP showed the strongest relationship with CD25 (r = .326, P = 0.003) (Figure 1). A hierarchical regression analysis was used to examine if the observed association between CD25 (step 2) and CRP (dependent variable) remained significant after entering potential covariates on step 1. Results for step 1 indicated that this model significantly accounted for variance in CRP (P < 0.001; R2 = .336) with BMI (β = 0.394, P = 0.002) and age (β = 0.246, P = 0.04) being significant predictors of CRP but not sex (β = −0.062, P = 0.48), ethnicity (β = 0.045, P = 0.70), smoking status (β = −0.027, P = 0.79), LTE (β = −0.056, P = 0.39), MAP (β = 0.084, P = 0.45) and HR (β = −0.004, P = 0.92). Results for step 2 indicated that the inclusion of CD25 significantly accounted for variance in CRP even after taking potential confounders into account (β for CD25 = 0.220, P = 0.04; ΔR2 = .036).

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlations between metric study variables.

| Variable | Age | BMI | HR | MAP | LTE1 | CD25 | CRP1 | IL-61 | sTNF-R11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | – | .521*** | .027 | −.001 | −.173 | .235* | .445*** | .106 | .003 |

| BMI | – | .194* | .303** | −.216* | .189* | ,535*** | .321** | .077 | |

| HR | – | .201* | −.240* | .080 | .110 | .220 | .219 | ||

| MAP | – | .042 | −.103 | .169 | .060 | .129 | |||

| LTE1 | – | −.017 | −.206 | −.001 | −.109 | ||||

| CD25 | – | .326** | −.033 | −.170 | |||||

| CRP1 | – | .159 | −.005 | ||||||

| IL-61 | – | .188 | |||||||

| sTNF-R11 | – |

Notes: BMI = body mass index; CD25 = chronotropic 25 dose; CRP = C-reactive protein; HR = baseline heart rate; IL-6 = interleukin 6; LTE = leisure-time exercise; MAP = baseline mean arterial blood pressure; sTNF-R1 = soluble tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor 1.

= based on log-transformed data.

P < 0.05;

P < .01,

P < .001.

Figure 1.

In the present investigation, we included 16 subjects with moderateobesity (class I obesity, BMI 30.0–34.9). Considering i) the strong relationship between BMI and CD25, ii) the potentially confounding role of BMI on the relationship between CD25 and inflammation, and iii) our intention to study a potential relationship between in vivo β-adrenergic receptor function and inflammation under non-pathological conditions, an exploratory model excluding these obese participants (N = 16, 10.8 %) was run. Results for step 1 indicated that this model significantly accounted for variance in CRP (P = 0.02; R2 = .259) with BMI (β = 0.300, P = 0.03) being a significant predictor of CRP but not age (β = 0.251, P = 0.06), sex (β = −0.019, P = 0.87), ethnicity (β = 0.027, P = 0.84), smoking status (β = −0.038, P = 0.75), LTE (β = −0.102, P = 0.44), MAP (β = 0.111, P = 0.39) and HR (β = −0.036, P = 0.77). Results for step 2 again indicated that the inclusion of CD25 significantly accounted for additional variance in CRP (β for CD25 = 0.288, P = 0.02; ΔR2 = .062). The exclusion of moderately obese participants thus strengthened the relationship between CD25 and CRP.

Although CD25 was not related to other inflammatory measures in the bivariate correlations, the same procedure (determining confounders followed by hierarchical analyses) was conducted for IL-6 and sTNF-R1. Using this approach, there were no significant associations of CD25 with IL-6 or with sTNF-R1 (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the association of β-adrenergic receptor function with plasma levels of inflammatory markers in a sample of healthy unmedicated adults. β-adrenergic receptors mediate several catecholamine-induced effects. A decreased sensitivity of these receptors is considered a physiological component of chronic stress (3, 11, 20) and an overactive sympathetic nervous system (49, 50). While prior findings in animals as well as human in vitro studies suggest that prolonged β-adrenergic receptor over-activation may facilitate inflammation (42–44), this study is the first study to include CD25, an in vivo marker of β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity. Our main finding is that higher CD25 values (reflecting decreased β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity) are related to higher circulating levels of the acute phase protein CRP. This association remained significant even after taking into account for several socio-demographic and health variables which may theoretically be confounded with CD25 and inflammation respectively.

The observed link between β-adrenergic receptor function and CRP is in line with previous research. First of all, catecholamines such as epinephrine increase the production of CRP in isolated hepatocytes in the presence or absence of IL-6 (81). In young mice, chronic β-adrenergic receptor stimulation with isoproterenol was sufficient to increase circulating CRP, whereas chronic treatment with β-adrenergic antagonists resulted in reduced CRP concentrations in aging mice (82, 83). The latter findings are quite interesting because chronic isoproterenol application in animal models may resemble prolonged catecholamine-induced β-adrenergic receptor over-activation in humans. Our findings also seem to be compatible with studies focusing on anti-inflammatory effects of β-adrenergic antagonists in clinical samples. For example, treatment of CVD patients with β-adrenergic antagonists has been shown to reduce circulating CRP concentrations (46, 47). A cross-sectional study among 2340 participants taking antihypertensive medications found lower serum CRP level among participants taking a β-blocker than among those not taking a β-blocker (84). Last but not least, CRP secretion is substantially heritable and plasma CRP concentrations in twins were predicted by multiple, common genetic variants in the catecholaminergic/β-adrenergic pathway (48).

Although the exact pathways by which β-adrenergic receptors may affect CRP are not clear, there are some potential mechanisms to be considered. First of all, a prolonged sympathetic over-activation may increase CRP production via pro-inflammatory cytokines. Especially, the secretion of IL-6 but also of TNF-α and IL-1 by the liver and adipose tissue has been proposed to increase hepatic CRP production (25, 85–91). Such a pathway would be in line with in vitro findings showing that pro-inflammatory responses in human monocytes are mediated by β-adrenergic receptor activation (42) and with animal studies demonstrating that chronic β-adrenergic stimulation increases pro-inflammatory cytokine expression (43, 44).

Curiously, in the present study no relationship between CD25 and IL-6 was observed. Assuming that CRP is induced by IL-6 in the liver, the observed association between CD25 and CRP may simply reflect the fact that CRP is a more integrative, stable and reliable marker for inflammation than IL-6. The latter may be supported by a higher average correlation coefficient for CRP (av.r = .878) than for IL-6 (av.r = .496) (average correlation coefficients were calculated from Z-transformed correlation coefficients of the three measures for each of the three inflammatory markers). Longitudinal analyses have found that CRP is stable during long-term follow-up, as long as it is not measured within 2 weeks of an acute infection (92, 93). Unlike CRP, the half-life of IL-6 is short and serum levels of IL-6 reflect only unbound IL-6. Moreover, CRP is less sensitive to minor health changes than IL-6 (70, 94–97).

As mentioned above, epinephrine, as well as glucagon, increases the production of CRP in isolated human hepatocytes even in the absence of IL-6 (81). In addition, exercise decreases CRP irrespective of any significant changes in IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-alpha in patients with fibromyalgia (98). Therefore, it may be possible that β-adrenergic receptor function is also related to CRP via pathways that are currently not known and that do not involve mechanisms involving pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 or TNF-alpha. The latter might also explain why sTNF-R1, which has similar stability as CRP (av.r = .932), was not related to CD25.

Although our data and the findings of previous studies suggest an association between β-adrenergic receptor function and CRP, it remains unclear what mechanism underlies that association. We suggest that a prolonged over-activation of β-adrenergic receptors may be related to a wide range of inflammatory alterations which might be better reflected by CRP, as an integrated and reliable inflammatory marker, than by specific pro-inflammatory cytokines. Features which have been related to reduced in vivo or vitro β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity (i.e. anxiety, perceived stress, hostility and depression) have also been linked to increased levels of inflammatory markers (12–15, 17, 31, 33, 56–59, 99, 100). The observation that psychological stress is important for almost all of these features may be interesting in view that β-adrenergic receptors are involved in stressor-induced pro-inflammatory alterations in animals (101, 102), and that α- and β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are sufficient to block stressor-induced increases in innate immunity (43, 103). Therefore, our finding of a robust relationship between inflammation and in vivo β-adrenergic receptor function in humans implicates that in vivo assessment of β-adrenergic receptor function may be promising in stress-related clinical states and conditions which have been linked to both sympathetic nervous system abnormalities and inflammation. Finally, our findings are interesting in light of the fact that previous human in vitro research has suggested an impact of β-adrenergic receptor function on the cardiovascular system by mediating the procoagulant response to acute stressors (16). Assuming the observed link between CD25 andCRP, and the association of elevated CRP with an increased risk for CVD (21–24), interesting results may arise from longitudinal studies which focus on CD25 as an additional predictor for pathological alterations in the cardiovascular system.

A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First of all, it may be important to consider alternative explanations of the observed relationship between CD25 and CRP. For example, β-AR function decreases with age (63, 63) and increased inflammatory markers such as CRP have also been related to higher age (66). Although we control for numerical age, we cannot exclude that the CD25-CRP relationship may be partially confounded by physiologic age since physiologic age may not always match numerical age. We also cannot exclude that the relationship between CD25 and CRP is due to confounding variables, which were not assessed in this study, although the impact of the most probable covariates was carefully examined. Secondly, a more complete understanding of the association between β-adrenergic receptor function and inflammation may arise from studies that assess immunological function more comprehensively. Finally, because of the cross-sectional design, causality in the relation between CD25 and CRP cannot be determined.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that decreased β-adrenergic receptor sensitivity (i.e., higher chronotropic 25 dose values) predicts CRP in a sample of healthy adults. To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate a link between inflammation and β-adrenergic receptor function using an in vivo method in humans. Future studies which focus on CD25 and inflammation in clinical samples may be promising.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by Grants HL36005 and HL44915 from the National Institutes of Health (J.E.D.).

List of Abbreviations

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- cAMP

cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate

- CD25

Chronotropic 25 Dose

- CRP

C-Reactive Protein

- CVD

Cardio Vascular Diseases

- HR

Heart Rate

- LTE

Leisure-time Exercise

- IL

Interleukin

- MAP

Mean Arterial Blood Pressure

- sTNF-R1

Soluble Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 1

References

- 1.Brodde O-E. Beta-adrenoceptors in cardiac disease. Pharmacol & Ther. 1993;60:405–430. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90030-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood AJ. Physiological regulation of beta-receptors in man. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1982;4:807–817. doi: 10.3109/10641968209061614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. The promise of adrenergic receptor studies in psychophysiologic research ii: Applications, limitations, and progress. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:448–457. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure: Physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1747–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lefkowitz RJ, Rockman HA, Koch WJ. Catecholamines, cardiac beta-adrenergic receptors, and heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:1634–1637. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liggett SB. Beta-adrenergic receptors in the failing heart: The good, the bad, and the unknown. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:947–948. doi: 10.1172/JCI12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kardia S, Kelly R, Keddache M, Aronow B, Grabowski G, Hahn H, Case K, Wagoner L, Dorn G, Liggett SB. Multiple interactions between the alpha2c- and beta1-adrenergic receptors influence heart failure survival. BMC Medical Genetics. 2008;9:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhalla NS, Dixon IMC, Rupp H, Barwinsky J. Experimental congestive heart failure due to myocardial infarction : Sarcolemmal receptors and cation transporters. Heidelberg, ALLEMAGNE: Springer; 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodde OE. Beta1- and beta2-adrenoceptor polymorphisms and cardiovascular diseases. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22:107–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert E, Lambert G. Stress and its role in sympathetic nervous system activation in hypertension and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2011;13:244–248. doi: 10.1007/s11906-011-0186-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. The promise of receptor studies in psychophysiologic research. Psychosom Med. 1988;50:555–566. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimsdale JE, Mills P, Patterson T, Ziegler M, Dillon E. Effects of chronic stress on beta-adrenergic receptors in the homeless. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:290–295. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzola-Pomietto P, Azorin J-M, Tramoni V, Jeanningros Rg. Relation between lymphocyte beta-adrenergic responsivity and the severity of depressive disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;35:920–925. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)91238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills PJ, Ziegler MG, Patterson T, Dimsdale JE, Hauger R, Irwin M, Grant I. Plasma catecholamine and lymphocyte beta 2-adrenergic receptor alterations in elderly alzheimer caregivers under stress. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:251–256. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suarez EC, Shiller AD, Kuhn CM, Schanberg S, Williams RB, Jr, Zimmermann EA. The relationship between hostility and beta-adrenergic receptor physiology in health young males. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:481–487. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Kaenel R, Mills PJ, Ziegler MG, Dimsdale JE. Effect of beta-adrenergic receptor functioning and increased norepinephrine on the hypercoagulable state with mental stress. Am Heart J. 2002;144:68–72. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu B-H, Dimsdale JE, Mills PJ. Psychological states and lymphocyte [beta]-adrenergic receptor responsiveness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:147–152. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00133-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherwood A, Hughes JW, Kuhn C, Hinderliter AL. Hostility is related to blunted β-adrenergic receptor responsiveness among middle-aged women. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:507–513. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000132876.95620.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes JW, Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, Suarez EC, Hinderliter AL. Hostility, social support, and adrenergic receptor responsiveness among african-american and white men and women. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:582–587. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041546.04128.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleaveland CR, Rangno RE, Shand DG. A standardized isoproterenol sensitivity test: The effects of sinus arrhythmia, atropine, and propranolol. Arch Intern Med. 1972;130:47–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.130.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, Corti MC, Wacholder S, Ettinger WH, Heimovitz H, Cohen HJ, Wallace R. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and c-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. The American journal of medicine. 1999;106:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koenig W, Sund M, Frohlich M, Fischer H-G, Lowel H, Doring A, Hutchinson WL, Pepys MB. C-reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men : Results from the monica (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease) augsburg cohort study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation. 1999;99:237–242. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jialal I, Devaraj S, Venugopal SK. C-reactive protein: Risk marker or mediator in atherothrombosis? Hypertens. 2004;44:6–11. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000130484.20501.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mugabo Y, Li L, Renier G. The connection between c-reactive protein (crp) and diabetic vasculopathy. Focus on preclinical findings. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2010;6:27–34. doi: 10.2174/157339910790442628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elenkov IJ. Neurohormonal-cytokine interactions: Implications for inflammation, common human diseases and well-being. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogel CFA, Sciullo E, Wong P, Kuzmicky P, Kado N, Matsumura F. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines and c-reactive protein in human macrophage cell line u937 exposed to air pollution particulates. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113 doi: 10.1289/ehp.8094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, Cooper NR, Eikelenboom P, Emmerling M, Fiebich BL, Finch CE, Frautschy S, Griffin WS, Hampel H, Hull M, Landreth G, Lue LF, Mrak R, Mackenzie IR, McGeer PL, O’Banion MK, Pachter J, Pasinetti G, Plata-Salaman C, Rogers J, Rydel R, Shen Y, Streit W, Strohmeyer R, Tooyoma I, Van Muiswinkel FL, Veerhuis R, Walker D, Webster S, Wegrzyniak B, Wenk G, Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation and alzheimers disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:383–421. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heikkilä K, Ebrahim S, Rumley A, Lowe G, Lawlor DA. Associations of circulating c-reactive protein and interleukin-6 with survival in women with and without cancer: Findings from the british women’s heart and health study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2007;16:1155–1159. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansson GK, Hermansson A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:204–212. doi: 10.1038/ni.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bankier B, Barajas J, Martinez-Rumayor A, Januzzi JL. Association between c-reactive protein and generalized anxiety disorder in stable coronary heart disease patients. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2212–2217. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctot KL. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446–457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with c-reactive protein, il-1, and il-6: A meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:171–186. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rief W, Hennings A, Riemer S, Euteneuer F. Psychobiological differences between depression and somatization. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grippo AJ, Johnson AK. Stress, depression and cardiovascular dysregulation: A review of neurobiological mechanisms and the integration of research from preclinical disease models. Stress. 2009;12:1–21. doi: 10.1080/10253890802046281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF, Glaser R. Psychoneuroimmunology: Psychological influences on immune function and health. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:537–47. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steiner M. Serotonin, depression, and cardiovascular disease: Sex-specific issues. Acta Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1748–1716.2010.02236.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishopric NH, Cohen HJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta adrenergic receptors in lymphocyte subpopulations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1980;65:29–33. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(80)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brodde O-E. Physiology and pharmacology of cardiovascular catecholamine receptors: Implications for treatment of chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 1990;120:1565–1572. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90060-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kammer GM. The adenylate cyclase-camp-protein kinase a pathway and regulation of the immune response. Trends Immunol. 1988;9:230–235. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nieto JL, Laviada IsD, Guillen A, Haro A. Adenylyl cyclase system is affected differently by endurance physical training in heart and adipose tissue. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51:1321–1329. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanders VM. The role of adrenoceptor-mediated signals in the modulation of lymphocyte function. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1995;5:283–298. doi: 10.1016/0960-5428(95)00019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grisanti LA, Evanson J, Marchus E, Jorissen H, Woster AP, DeKrey W, Sauter ER, Combs CK, Porter JE. Pro-inflammatory responses in human monocytes are [beta]1-adrenergic receptor subtype dependent. Mol Immunol. 2005;47:1244–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson JD, Campisi J, Sharkey CM, Kennedy SL, Nickerson M, Greenwood BN, Fleshner M. Catecholamines mediate stress-induced increases in peripheral and central inflammatory cytokines. Neuroscience. 2005;135:1295–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray DR, Prabhu SD, Chandrasekar B. Chronic {beta}-adrenergic stimulation induces myocardial proinflammatory cytokine expression. Circulation. 2000;101:2338–2341. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.20.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yabuuchi K, Maruta E, Yamamoto J, Nishiyori A, Takami S, Minami M, Satoh M. Intracerebroventricular injection of isoproterenol produces its analgesic effect through interleukin-1[beta] production. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;334:133–140. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jenkins NP, Keevil BG, Hutchinson IV, Brooks NH. Beta-blockers are associated with lower c-reactive protein concentrations in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2002;112:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anzai T, Yoshikawa T, Takahashi T, Maekawa Y, Okabe T, Asakura Y, Satoh T, Mitamura H, Ogawa S. Early use of beta-blockers is associated with attenuation of serum c-reactive protein elevation and favorable short-term prognosis after acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 2003;99:47–53. doi: 10.1159/000068449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wessel J, Moratorio G, Rao F, Mahata M, Zhang L, Greene W, Rana BK, Kennedy BP, Khandrika S, Huang P, Lillie EO, Shih P-AB, Smith DW, Wen G, Hamilton BA, Ziegler MG, Witztum JL, Schork NJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, O’Connor DT. C-reactive protein, an ‘intermediate phenotype’ for inflammation: human twin studies reveal heritability, association with blood pressure and the metabolic syndrome, and the influence of common polymorphism at catecholaminergic/[beta]-adrenergic pathway loci. J Hypertens. 2007;25:329–343. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328011753e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. The promise of adrenergic receptor studies in psychophysiologic research II: Applications, limitations, and progress. Psychosom Med. 1993;55:448–458. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. The promise of receptor studies in psychophysiologic research. Psychosom Med. 1988;55:555–566. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Tits LJ, Michel MC, Grosse-Wilde H, Happel M, Eigler FW, Soliman A, Brodde OE. Catecholamines increase lymphocyte beta 2-adrenergic receptors via a beta 2-adrenergic, spleen-dependent process. American Journal of Physiology - Endocrinology And Metabolism. 1990;258:191–202. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.1.E191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tohmeh JF, Cryer PE. Biphasic adrenergic modulation of beta-adrenergic receptors in man. Agonist-induced early increment and late decrement in beta-adrenergic receptor number. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1980;65:836–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI109735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cleaveland CR, Rangno RE, Shand DG. A standardized isoproterenol sensitivity test. The effects of sinus arrhythmia, atropine, and propranolol. Arch Intern Med. 1972;130:47–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.130.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brodde OE, Kretsch R, Ikezono K, Zerkowski HR, Reidemeister JC. Human beta-adrenoceptors: Relation of myocardial and lymphocyte beta-adrenoceptor density. Science. 1986;231:1584–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.3006250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Christou DD, Seals DR. Decreased maximal heart rate with aging is related to reduced β-adrenergic responsiveness but is largely explained by a reduction in intrinsic heart rate. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:24–29. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90401.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jain S, Dimsdale JE, Roesch SC, Mills PJ. Ethnicity, social class and hostility: Effects on in vivo [beta]-adrenergic receptor responsiveness. Biol Psychol. 2004;65:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(03)00111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sherwood A, Hughes JW, Kuhn C, Hinderliter AL. Hostility is related to blunted {beta}-adrenergic receptor responsiveness among middle-aged women. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:507–513. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000132876.95620.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu B-H, Kang E-H, Ziegler MG, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. Mood states, sympathetic activity, and in vivo β-adrenergic receptor function in a normal population. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:559–564. doi: 10.1002/da.20338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hughes JW, Sherwood A, Blumenthal JA, Suarez EC, Hinderliter AL. Hostility, social support, and adrenergic receptor responsiveness among african-american and white men and women. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:582–587. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000041546.04128.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le Melledo J-M, Arthur H, Dalton J, Woo C, Lipton N, Bellavance F, Koszycki D, Boulenger J-P, Bradwejn J. The influence of type a behavior pattern on the response to the panicogenic agent cck-4. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:513–520. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roberts WL, Moulton L, Law TC, Farrow G, Cooper-Anderson M, Savory J, Rifai N. Evaluation of nine automated high-sensitivity c-reactive protein methods: Implications for clinical and epidemiological applications. Part 2. Clin Chem. 2001;47:418–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Godin G, Shephard RJ. Godin leisure-time exercise questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bao X, Mills PJ, Rana BK, Dimsdale JE, Schork NJ, Smith DW, Rao F, Milic M, O’Connor DT, Ziegler MG. Interactive effects of common beta2-adrenoceptor haplotypes and age on susceptibility to hypertension and receptor function. Hypertens. 2005;46:301–307. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000175842.19266.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ebstein RP, Stessman J, Eliakim R, Menczel J. The effect of age on beta-adrenergic function in man: A review. 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gameiro C, Romao F. Changes in the immune system during menopause and aging. doi: 10.2741/e190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Singh T, Newman AB. Inflammatory markers in population studies of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;10:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eklund CM. Proinflammatory cytokines in crp baseline regulation. 2009 doi: 10.1016/s0065-2423(09)48005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petersen AMW, Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1154–1162. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00164.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arnson Y, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 34:J258–J265. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1805–1812. doi: 10.1172/JCI18921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: A primer. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8:3. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Enders CK. A primer on the use of modern missing-data methods in psychosomatic medicine research. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:427–436. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221275.75056.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Graham JW. Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:549–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allison PD, Hauser RM. Reducing bias in estimates of linear models by remeasurement of a random subsample. Soc Method Res. 1991;19:466. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: J. Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fisher RA. Statistical methods for research workers. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd Ltd; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marshall A, Altman D, Holder R, Royston P. Combining estimates of interest in prognostic modelling studies after multiple imputation: Current practice and guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Darmawan IN. Norm software review: Handling missing values with multiple imputation methods. Evaluation Journal of Australasia. 2002;2:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 81.O’Riordain MG, Ross JA, Fearon KC, Maingay J, Farouk M, Garden OJ, Carter DC. Insulin and counterregulatory hormones influence acute-phase protein production in human hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1995;269:323–330. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.269.2.E323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hu A, Jiao X, Gao E, Koch WJ, Sharifi-Azad S, Grunwald Z, Ma XL, Sun J-Z. Chronic beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation induces cardiac apoptosis and aggravates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by provoking inducible nitric-oxide synthase-mediated nitrative stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:469–475. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hu A, Jiao X, Gao E, Li Y, Sharifi-Azad S, Grunwald Z, Ma XL, Sun JZ. Tonic beta-adrenergic drive provokes proinflammatory and proapoptotic changes in aging mouse heart. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:215–226. doi: 10.1089/rej.2007.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Palmas W, Ma S, Psaty B, Goff DC, Darwin C, Barr RG. Antihypertensive medications and c-reactive protein in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bastard JP, Jardel C, Delattre J, Hainque B, Bruckert E, Oberlin F. Evidence for a link between adipose tissue interleukin-6 content and serum c-reactive protein concentrations in obese subjects. Circulation. 1999;99:2219–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fontana L, Eagon JC, Trujillo ME, Scherer PE, Klein S. Visceral fat adipokine secretion is associated with systemic inflammation in obese humans. Diabetes. 2007;56:1010–1013. doi: 10.2337/db06-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kern PA, Saghizadeh M, Ong JM, Bosch RJ, Deem R, Simsolo RB. The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue. Regulation by obesity, weight loss, and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2111–2119. doi: 10.1172/JCI117899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Klein S, Fontana L, Young VL, Coggan AR, Kilo C, Patterson BW, Mohammed BS. Absence of an effect of liposuction on insulin action and risk factors for coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2549–2557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Maachi M, Pieroni L, Bruckert E, Jardel C, Fellahi S, Hainque B, Capeau J, Bastard JP. Systemic low-grade inflammation is related to both circulating and adipose tissue tnf[alpha], leptin and il-6 levels in obese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:993–997. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Warren RS, Starnes HF, Jr, Gabrilove JL, Oettgen HF, Brennan MF. The acute metabolic effects of tumor necrosis factor administration in humans. Arch Surg. 1987;122:1396–1400. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1987.01400240042007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yudkin JS, Stehouwer CDA, Emeis JJ, Coppack SW. C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: Associations with obesity, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction : A potential role for cytokines originating from adipose tissue? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:972–978. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ockene IS, Matthews CE, Rifai N, Ridker PM, Reed G, Stanek E. Variability and classification accuracy of serial high-sensitivity c-reactive protein measurements in healthy adults. Clin Chem. 2001;47:444–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836–843. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bataille R, Klein B. Serum levels of beta 2 microglobulin and interleukin-6 to differentiate monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 1992;80:2433–2434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Emile C, Fermand J-P, Danon F. Interleukin-6 serum levels in patients with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1994;86:439–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb04765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Heinrich PC, Castell JV, Andus T. Interleukin-6 and the acute phase response. 1990 doi: 10.1042/bj2650621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kao PC, Shiesh SC, Wu TJ. Serum C-reactive protein as a marker for wellness assessment. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2006;36:163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ortega E, Garcia JJ, Bote ME, Martin-Cordero L, Escalante Y, Saavedra JM, Northoff H, Giraldo E. Exercise in fibromyalgia and related inflammatory disorders: known effects and unknown chances. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2009;15:42–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stewart JC, Janicki-Deverts D, Muldoon MF, Kamarck TW. Depressive symptoms moderate the influence of hostility on serum interleukin-6 and c-reactive protein. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:197–204. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181642a0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.O’Donovan A, Hughes BM, Slavich GM, Lynch L, Cronin M-T, O’Farrelly C, Malone KM. Clinical anxiety, cortisol and interleukin-6: Evidence for specificity in emotion-biology relationships. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:1074–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bierhaus A, Wolf J, Andrassy M, Rohleder N, Humpert PM, Petrov D, Ferstl R, von Eynatten M, Wendt T, Rudofsky G, Joswig M, Morcos M, Schwaninger M, McEwen B, Kirschbaum C, Nawroth PP. A mechanism converting psychosocial stress into mononuclear cell activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1920–1925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cole SW, Arevalo JMG, Takahashi R, Sloan EK, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Sheridan JF, Seeman TE. Computational identification of gene-social environment interaction at the human il-6 locus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911515107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hanke M, Bailey M, Powell N, Stiner L, Sheridan J. Beta-2 adrenergic blockade decreases the immunomodulatory effects of social disruption stress (sdr) Brain Behav, and Immunity. 2008;22:39–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]