Background: Molecular chaperone regulation of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) trafficking in epithelia is poorly described.

Results: Hsp70 increases ENaC functional and surface expression in epithelia.

Conclusion: ENaC exits the endoplasmic reticulum via a Sec24D-dependent mechanism; this is promoted by Hsp70.

Significance: Improved understanding of ENaC trafficking may lead to novel therapeutic targets in blood pressure abnormalities and in cystic fibrosis.

Keywords: ENaC, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Epithelial Cell, Heat Shock Protein, Intracellular Trafficking, Molecular Chaperone, Sodium Channels

Abstract

The epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) plays an important role in the homeostasis of blood pressure and of the airway surface liquid, and inappropriate regulation of ENaC results in refractory hypertension (in Liddle syndrome) and impaired mucociliary clearance (in cystic fibrosis). The regulation of ENaC by molecular chaperones, such as the 70-kDa heat shock protein Hsp70, is not completely understood. Building on the previous suggestion by our group that Hsp70 promotes ENaC functional and surface expression in Xenopus oocytes, we investigated the mechanism by which Hsp70 acts upon ENaC in epithelial cells. In Madin-Darby canine kidney cells stably expressing epitope-tagged αβγ-ENaC and with tetracycline-inducible overexpression of Hsp70, treatment with 1 or 2 μg/ml doxycycline increased total Hsp70 expression ∼2-fold and ENaC functional expression ∼1.4-fold. This increase in ENaC functional expression corresponded to an increase in ENaC expression at the apical surface of the cells and was not present when an ATPase-deficient Hsp70 was similarly overexpressed. The increase in functional expression was not due to a change in the rate at which ENaC was retrieved from the apical membrane. Instead, Hsp70 overexpression increased the association of ENaC with the Sec24D cargo recognition component of coat complex II, which carries protein cargo from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi. These data support the hypothesis that Hsp70 promotes ENaC biogenesis and trafficking to the apical surface of epithelial cells.

Introduction

The epithelial sodium channel (ENaC)2 is important in maintaining salt and water homeostasis in a number of organ systems. Through its action in the distal nephron, ENaC plays a critical role in control of blood pressure (1), as is evidenced by the severe conditions caused by ENaC dysregulation. In the absence of ENaC, salt wasting can occur in the kidneys, leading to hypotension and a condition known as pseudohypoaldosteronism type 1 (2). In contrast, patients with Liddle syndrome have salt-sensitive hypertension, which results from ENaC functional overexpression in the distal nephron (2–5). In addition to its critical role in blood pressure regulation, ENaC also plays an important role in the airway epithelia. In patients with cystic fibrosis, ENaC function appears elevated, which is hypothesized to cause airway surface liquid volume depletion, decreased mucociliary clearance, and increased bacterial colonization of the airway (6). Because ENaC clearly has a key role in the normal homeostasis of a number of tissues and organ systems, it is critical to understand the mechanisms underlying ENaC regulation to better understand diseases pertaining to these organs.

ENaC is likely a heterotrimer of three homologous subunits: α, β, and γ. This hypothesized structure is based on the structure of a related ENaC/degenerin family member, the acid-sensing ion channel (7). This heterotrimeric structure is also supported by recent atomic force microscopy data (8). Each subunit of ENaC contains N- and C-terminal intracellular domains, as well as a large extracellular domain with many glycosylation sites (9, 10). As with many secreted and membrane proteins, ENaC subunits are most likely assembled in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Either the initial assembly of ENaC subunits or their exit from the ER appears to be inefficient in model systems, and a significant fraction of newly synthesized channel is targeted for degradation by an ER-associated degradation pathway (ERAD) (11–13). ENaC that successfully exits the ER is transported to the Golgi by an as yet unknown mechanism. The C terminus of the ENaC α-subunit appears to control the exit of ENaC from the ER and contains a consensus sequence for interaction with coat complex II (COP II) machinery (14). However, direct evidence of an interaction of ENaC with COP II has not been presented.

Once in the Golgi, ENaC can undergo glycosyl side chain modification, as well as proteolytic cleavage of the α- and γ-subunit extracellular domains by furin, a Golgi-resident protein convertase (15). This proteolysis is associated with an increase in the open probability (Po) of ENaC once it reaches the apical epithelial surface. ENaC can also, by an unknown mechanism, reach the cell surface without undergoing glycosyl and proteolytic processing in the Golgi, arriving at the membrane in an uncleaved, low Po form (16).

Regulation of ENaC at the cell surface can occur either by modification of the total number of channels present (N) or by cleavage of the uncleaved channels that were delivered to the cell surface, thus modifying ENaC Po. Conversion of uncleaved, low Po to cleaved, higher Po ENaC at the cell surface can result either from the action of prostasin or other endogenous channel-activating proteases or from the action of exogenous proteases such as trypsin or elastase (15, 17–21). The number of active ENaC at the cell surface can also be regulated by the rate at which channels are retrieved, a process that is regulated by the E-3 ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 and that is disrupted in Liddle syndrome (22–24).

Our group has previously shown that Hsp70, the stress-inducible 70-kDa heat shock protein, promotes both surface expression and function of ENaC when overexpressed in Xenopus oocytes (25). Based on these data, we hypothesized that Hsp70 would also regulate ENaC functional and surface expression in mammalian epithelia. Here we use Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells as a model system to investigate the mechanism by which Hsp70 regulates ENaC. We show that Hsp70 does, in fact, increase ENaC functional and surface expression in epithelial cells. Our data further suggest that Hsp70 increases the interaction of ENaC with the COP II machinery known to transport proteins from the ER to the Golgi. These data therefore support the hypothesis that Hsp70 promotes ENaC biogenesis and trafficking.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

We employed Type I MDCK cells that stably express C-terminally epitope-tagged murine ENaC subunits (α-HA, β-V5, and γ-Myc), which appear to traffic and function similarly to the native subunits in model systems (13). The cells were selected to have tetracycline-inducible expression of Hsp70 or ATPase-deficient Hsp70 (T37G, (26, 27)), which are also epitope-tagged (C-terminal Myc/His). The cells were cultured in 50:50 Ham's F-12 (Cellgro; Mediatech, Manassas, VA) and DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini, West Sacramento, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). The cells are maintained under antibiotic selective pressure with addition of puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich), G418 Sulfate (Cellgro, Mediatech), blasticidin S HCl (Invitrogen), hygromycin B (Roche Applied Science), and Zeocin (Invitrogen) to the medium.

For cell surface expression analysis, the cells were grown in polarized monolayers on Transwell plates (Costar; Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA) and assessed when resistance reached 300 Ω·cm2. For ion transport measurements, the cells were grown in monolayers on Snapwell plates (Costar; Corning Life Sciences) and used when resistance was ≥500 Ω·cm2. The cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h prior to the experiment. Unless otherwise indicated, the cells were treated with doxycycline (Dox; Sigma-Aldrich) for the final 24 h of the dexamethasone treatment.

Antibodies and Protein Reagents

Murine anti-Hsp70 (StressMarq, Victoria, Canada), anti-V5 epitope (for β-ENaC; Invitrogen), anti-Myc epitope (for γ-ENaC; Invitrogen), and anti-Sec24D (Abnova, Taiwan) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Rat anti-HA epitope (for α-ENaC; Roche Applied Science) and rabbit anti-Hsc70 (Stressgen, Farmingdale, NY) were also used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Millipore. Purified human Hsp70 with a C-terminal His tag was purchased from StressMarq.

Immunoblot

The cells were lysed on ice for 30 min in RIPA buffer (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris·HCl, pH 8, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing a 1:1000 dilution of protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysates were collected, passed through a 21-gauge needle, and centrifuged (14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C) to remove particulates.

Protein content in the lysate supernatants was determined using DC protein assay reagents (Bio-Rad) and BSA as a standard. Equal amounts of protein (25 μg, unless otherwise indicated) were resolved using SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose using semi-dry techniques (Bio-Rad). Nonspecific protein binding was diminished by incubating the membrane in either 5% BSA or 5% nonfat milk in TBS (10 mm Tris·HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl) with 0.05% Tween 20. Primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied in TBS with 0.05% Tween 20 with 1% nonfat milk or 1% BSA. Immunoreactivity was detected by chemiluminescence (SuperSignal; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and fluorography. Densitometry was performed using an AlphaImager 2200 system (AlphaInnotech, Santa Clara, CA).

Co-immunoprecipitation

The cell lysates were prepared as described above in RIPA buffer, except that SDS was omitted from the RIPA. Protein A- or G-Sepharose beads (protein A for rabbit antibodies and protein G for rat and mouse antibodies; Invitrogen) were washed with PBS and combined with primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Afterward, the beads were washed with PBS and combined with 250 μg of cell lysates on a rotator overnight at 4 °C. The beads were washed in RIPA buffer lacking SDS, and then the precipitated proteins were released from beads by heating in Laemmli sample buffer (125 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.006% bromphenol blue, 1.8% 2-mercaptoethanol) and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Associated proteins were detected by immunoblot analysis.

Short Circuit Current Measurement

The cells grown on Snapwell plates with resistance >500 Ω·cm2 were mounted in a vertical Ussing chamber setup and underwent continuous voltage clamping (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA). The bath solution was 115 mm NaCl, 25 mm NaHCO3, 2.4 mm KH2PO4, 1.2 mm K2HPO4, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 1.2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, pH 7.4, at 37 °C and was the same in the apical and basal chambers. Short circuit current (Isc) was analyzed using Acquire & Analyze data acquisition software (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA). Resistance was monitored and calculated by Ohm's law using 2-mV bidirectional pulses every 90 s. Amiloride, cycloheximide, and trypsin (all from Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved as 100× concentrated stocks in bath solution. Apical application of 10 μm amiloride and 10 μg/ml trypsin (final concentration) was used where indicated. Both apical and basolateral applications of 100 μg/ml cycloheximide (final concentration) were used in ENaC retrieval assays.

Cell Surface Expression Assay

The cells were grown on Transwell plates until resistance measured ≥300 Ω·cm2. The cells were placed on ice for 20 min and washed with ice-cold PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+, pH 7.4. The apical surface of the cells was then treated with 1 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (200 mg/ml stock in Me2SO; Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in biotinylation buffer (10 mm H3BO4, 137 mm NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2, pH 8.0) for 25 min on ice. This step was repeated one time for an additional 25 min. The cells were then washed three times with quenching buffer (192 mm glycine, 25 mm Tris HCl, pH 8.3) and incubated on ice in quenching buffer for 20 min. The cells were washed in PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (containing SDS) as described above. Biotinylated proteins were precipitated using NeutrAvidin beads (Invitrogen), resolved by SDS-PAGE, and revealed by immunoblotting.

Pulse-Chase Assay

Pulse-chase assays were performed using modifications of a published protocol (14). After the dexamethasone and Dox treatments described above (1 μg/ml each), the cells were starved in DMEM lacking methionine and cysteine (Invitrogen, Mediatech) for 1 h. After starvation, the medium was replaced with 0.5 ml of the same medium containing 50–100 μCi of [35S]Met/Cys (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) for 20 min. The cells were washed in PBS containing excess methionine and cysteine (2.5 mm each) and chased for indicated times in the 50:50 Ham's F-12 medium/DMEM described under “Cell Culture” above (including 10% fetal bovine serum), also containing excess Met and Cys. The cells were washed with PBS and lysed in RIPA without SDS, as described above. Labeled proteins were recovered by immunoprecipitation as described above, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and revealed by fluorography on a Typhoon PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare) after gels were fixed in 30% methanol, 10% acetic acid for 20 min and dried.

Where indicated, two sequential immunoprecipitation steps were performed. The first immunoprecipitation was performed as described above. Recovered proteins were released from beads by heating for 30 min at 65 °C in Laemmli sample buffer lacking bromphenol blue. After heating, 10% of the sample was removed for analysis, whereas the remaining fraction was combined with RIPA buffer lacking SDS to reduce the concentration of SDS in the buffer to below 0.2%. This diluted sample was then combined with beads conjugated to a second primary antibody and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rotation. After washing, the samples were released from beads by heating in Laemmli sample buffer for 3.5 min at 95 °C. Recovered proteins were again resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by fluorography as described above.

Densitometric Analysis

Fluorographic images of immunoblots were digitized using an Alphaimager 2200 digital analysis system (AlphaInnotech, San Leandro, CA). Densitometric analysis of these images was performed using Alphaimager analysis software (version 5.5; AlphaInnotech) with two-dimensional integration of the selected band. For pulse-chase analyses, densitometric signal was determined using ImageQuant TL software on the Typhoon PhosphorImager. For comparison within an individual experiment, the density of untreated control was arbitrarily set to 1.0, with the remaining densities expressed relative to this reference density.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed Student's t test or a one-way ANOVA as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat software (version 2.03; Aspire, Ashburn, VA). A p value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Hsp70 Overexpression in MDCK Epithelial Cells

MDCK epithelial cells, which are commonly used to study ENaC trafficking and function (28–30), were used as a representative model system. MDCK cells are a useful model because they form polarized monolayers when grown on permeable supports; this allows measurement of ion transport, as well as correlation of these ion transport measurements with direct biochemical assessment of surface expression. In addition, these cells do not endogenously express high levels of ENaC under normal conditions and can be selected to stably express epitope-tagged αβγ-ENaC (α-HA, β-V5, and γ-Myc). These C-terminally epitope-tagged ENaC subunits have previously been shown to traffic and function similarly to the native subunits in model systems (13).

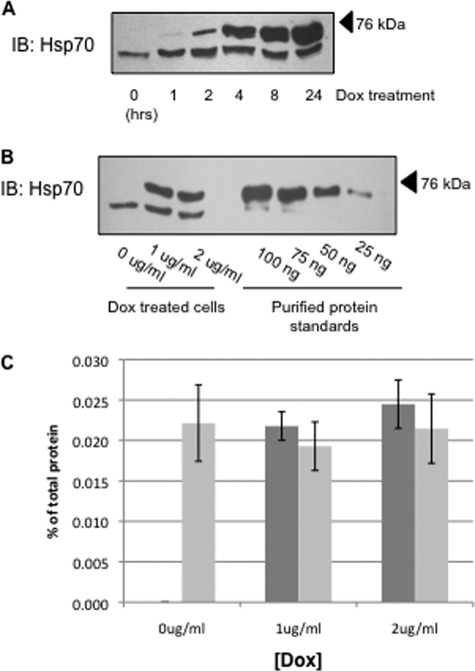

We selected clones of MDCK cells that stably express αβγ-ENaC and that have tetracycline-inducible overexpression of human Hsp70 or an ATPase-deficient version of human Hsp70 (T37G), which are also epitope-tagged (C-terminal Myc/His). Fig. 1A demonstrates a time course of Dox-induced Hsp70 expression. The epitope tag on the induced protein reduced its electrophoretic mobility, which facilitated quantification of both the endogenous (lower bands) and overexpressed (upper bands) proteins by immunoblot analysis. The amount of Hsp70 overexpression increases with the increased length of Dox treatment, with the 24-h treatment having the highest level of Hsp70 overexpression. All of the subsequent experiments were therefore performed using a 24-h incubation with Dox.

FIGURE 1.

Overexpression of Hsp70 in MDCK cell lysates. A, MDCK cells were treated with 1 μg/ml Dox for indicated time periods, and Hsp70 was detected in cell lysates by immunoblot (IB). The lower bands and upper bands represent the endogenous Hsp70 protein and the Myc/His-tagged construct of Hsp70 protein, respectively. B, Hsp70 expression was determined by immunoblot after a 24-h incubation with the indicated amount of Dox. This immunoreactivity was compared with that of purified Hsp70 protein to quantify Hsp70 expression. C, densitometric analysis of bands from five independent Hsp70 immunoblots quantifying endogenous (light bars) and overexpressed (dark bars) chaperone. The error bars indicate S.E.

To quantify Hsp70 overexpression and estimate total cellular expression of Hsp70, we treated cells with or without Dox to induce overexpression of Hsp70 and compared the Hsp70 immunoreactivity with that of a commercially available, purified Hsp70 (Fig. 1B, representative immunoblot). This purified Hsp70 standard was also C-terminally His-tagged, so the electrophoretic mobility of this protein is again slightly less than that of the native chaperone and is more similar to that of the Dox-induced, Myc/His-tagged chaperone in our cell lysates. Densitometric quantification of these experiments is summarized in Fig. 1C and suggests that induced Hsp70-Myc/His expression in 25 μg of total cell lysate is ∼0.22–0.24% of total lysate protein. This appears to be slightly higher than the expression of native Hsp70, which is in the range of 25–30 ng/25 μg (approximately 0.20%) of total cellular protein. This represents a slightly greater than 2-fold whole cell overexpression of Hsp70 when cells are treated with 1 or 2 μg/ml Dox. Importantly, this overexpression of Hsp70 did not alter the expression of Hsc70 (70-kDa heat shock cognate protein) in these cells (Fig. 2).

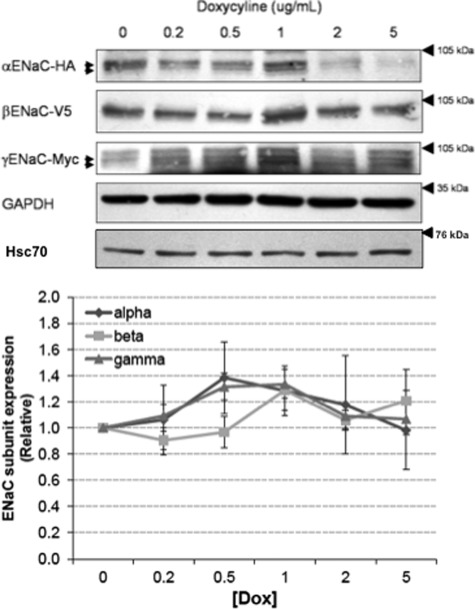

FIGURE 2.

Effect of Hsp70 overexpression on whole cell Hsc70 and ENaC expression in MDCK cells. MDCK cells were treated with the indicated amount of Dox for 24 h, and expression of the ENaC subunits was determined by immunoblot analysis using antibodies directed to the epitope tags on each of the subunits. Immunoblot detection of Hsc70 protein expression was conducted using an Hsc70-specific antibody. GAPDH immunoreactivity was used as a loading control. Densitometric quantification of α-, β-, and γ-ENaC expression are depicted graphically (means ± S.E.); none of these changes in relative expression (versus 0 Dox control) are statistically significant by ANOVA. These data are representative of three independent experiments.

Hsp70 Does Not Significantly Alter Whole Cell ENaC Expression

We next tested the influence of Hsp70 overexpression on whole cell expression of the ENaC subunits. The cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Dox, and whole cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the α, β, and γ ENaC subunits using antibodies directed to the epitope tags (α-HA, β-V5, or γ-Myc) as indicated (Fig. 2). Although in some experiments, there was increased expression of all three ENaC subunits with an intermediate level of Hsp70 overexpression (1 μg/ml Dox) that decreased with higher levels of Dox (5 μg/ml) and was consistent with the previous data of our group from Xenopus oocytes (25), these data did not achieve statistical significance. These data suggest that Hsp70 overexpression does not significantly alter the whole cell expression of ENaC in MDCK cells.

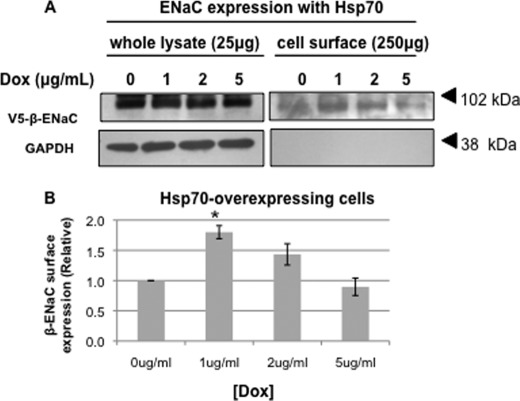

Increased Hsp70 Expression Leads to Increased ENaC Surface and Functional Expression

We next examined the effect of Hsp70 overexpression on ENaC expression at the apical surface using a surface biotinylation assay on MDCK cells grown as polarized monolayers (Fig. 3). Consistent with our hypothesis, β-ENaC expression at the apical cell surface (biotin-tagged) increased significantly with 1 μg/ml (Fig. 3A). There was also a trend toward increased surface expression in cells treated with 2 μg/ml Dox that was not statistically significant. Importantly, as a control, biotinylated GAPDH was not detected in the NeutrAvidin-precipitated proteins, suggesting that we were detecting only surface β-ENaC and that our cells were not leaky to the membrane-impermeant biotin. These data indicate that Hsp70 increases the expression of ENaC at the apical cell surface.

FIGURE 3.

Hsp70 overexpression increases the surface expression of ENaC in MDCK cells. MDCK cells were treated with the indicated amount of Dox for 24 h. β-ENaC at the apical surface was detected by surface biotinylation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, representative immunoblots for β-ENaC (using an antibody to the V5 epitope tag) of whole cell lysates and NeutrAvidin-precipitated proteins are shown. Immunoblots for GAPDH were used as a control for protein loading (whole cell lysates) and to ensure that the membrane-impermeant biotin did not label intracellular proteins (NeutrAvidin precipitates). B, densitometric quantification of immunoblots from three independent biotinylation experiments. The error bars indicate S.E. *, p = 0.004 versus 0 μg/ml Dox treatment (ANOVA).

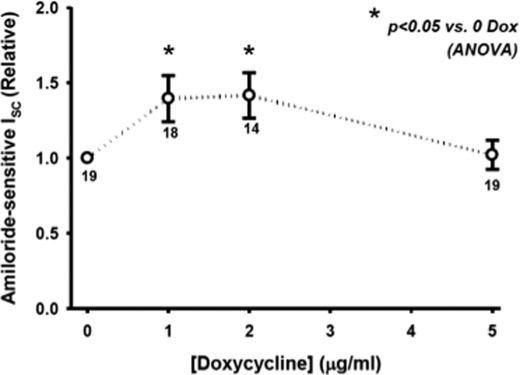

To determine whether Hsp70 also promotes ENaC functional expression, we determined the amiloride-sensitive short circuit current (Isc) in Ussing chambers. As shown in Fig. 4, Hsp70 overexpression induced by 1 or 2 μg/ml Dox caused an increase in amiloride-sensitive Isc. Again, Hsp70 overexpression with 5 μg/ml was ineffective at increasing ENaC functional expression, as it was for surface expression (Fig. 3) and whole cell expression (Fig. 2). Together, these data suggest that Hsp70 overexpression can increase ENaC functional expression at least in part by increasing the expression of ENaC at the apical membrane.

FIGURE 4.

Hsp70 expression increases ENaC functional expression in MDCK cells. MDCK cells were grown as epithelial monolayers on semi-permeable supports and incubated with the indicated concentration of Dox for 24 h. Amiloride-sensitive Isc was determined in Ussing chambers as described under “Experimental Procedures” and are expressed relative to samples incubated without Dox. The means ± S.E. for n replicates are indicated. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA.

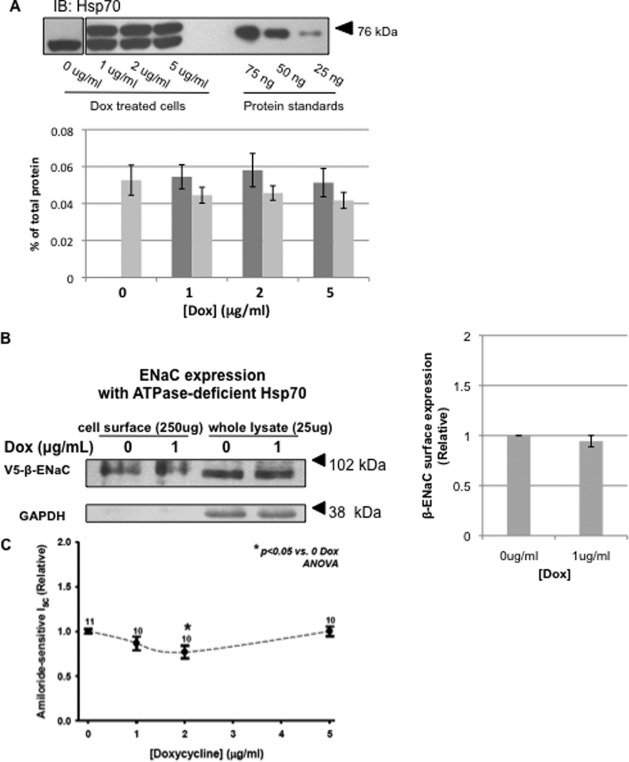

As a control experiment, we constructed a homologous MDCK cell line with Dox-inducible expression of an ATPase-deficient Hsp70. Because Hsp70 binding to cellular clients depends on its ATPase activity, removal of this activity should inactivate the chaperone; this has been shown for ATPase-deficient constructs of BiP, the ER-luminal Hsp70 homolog (26, 27). Fig. 5A demonstrates the successful overexpression of ATPase-deficient (T37G) Hsp70-Myc/His at levels similar to those of endogenous Hsp70, as well as at levels similar to those of functional Hsp70-Myc/His (Fig. 1). Importantly, overexpression of ATPase-deficient Hsp70 did not result in an increase in expression of β-ENaC at the apical surface (Fig. 5B) or in amiloride-sensitive current in Ussing chambers (Fig. 5C). These control data therefore suggest that the positive effect of Hsp70 on ENaC functional and surface expression requires Hsp70 ATPase activity and is not merely an artifact of overexpression.

FIGURE 5.

Influence of ATPase-deficient Hsp70 on ENaC functional expression. MDCK cells with inducible expression of ATPase-deficient Hsp70-Myc/His were treated with indicated concentrations of Dox for 24 h. A, representative immunoblot (IB) showing the endogenous Hsp70 (lower bands) and induced ATPase-deficient Hsp70-Myc/His (upper bands) proteins. These panels are from the same immunoblot; however, intervening sample lanes were removed. The graph depicts densitometric analysis of three independent experiments. Light gray bars represent endogenous Hsp70, whereas dark gray bars indicate Myc/His-tagged ATPase-deficient Hsp70. The error bars indicate S.E. B, representative surface biotinylation experiment of cells with inducible overexpression of ATPase-deficient Hsp70 (of n = 3 independent experiments). Immunoblots for β-ENaC (using an antibody to the V5 epitope tag) of whole cell lysates and NeutrAvidin precipitated proteins are shown. Immunoblots for GAPDH were used as a control for protein loading (whole cell lysates) and to ensure that the membrane-impermeant biotin did not label intracellular proteins (NeutrAvidin precipitates). C, cells with inducible ATPase-deficient Hsp70 expression were grown as epithelial monolayers on semi-permeable supports. After 24 h in the presence of indicated concentrations of Dox, amiloride-sensitive Isc was determined using Ussing chambers and is expressed relative to samples incubated without Dox. The means ± S.E. for n replicates are indicated. Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA.

Hsp70 Overexpression Does Not Alter Retrieval of Functional ENaC from Apical Membrane

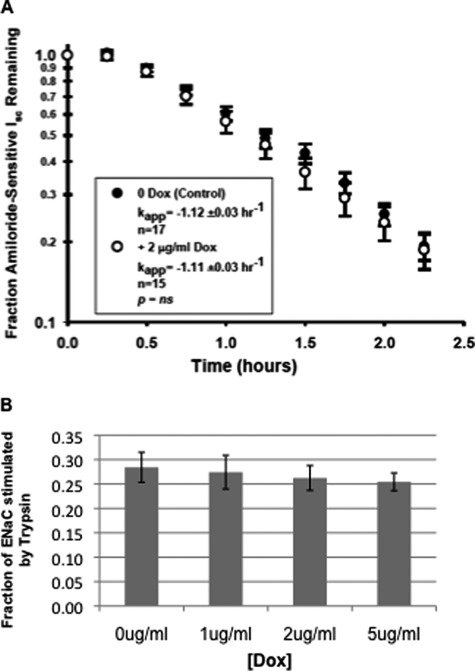

We sought to determine the mechanism by which Hsp70 increases ENaC functional expression. We first addressed whether Hsp70 overexpression influenced the rate at which functional ENaC was retrieved from the apical surface. After induction of Hsp70 overexpression and determination of base-line Isc, cells were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit new protein synthesis, and the apparent first order rate constant of decay of amiloride-sensitive Isc was determined (Fig. 6A). These data indicate that Hsp70 overexpression does not change the rate at which functional ENaC was removed from the apical cell surface.

FIGURE 6.

Hsp70 overexpression does not affect the rate at which functional ENaC is retrieved from or the relative expression of uncleaved versus cleaved ENaC at the apical surface of MDCK cells. A, MDCK cells were treated without or with Dox for 24 h, and a base-line Isc was established in Ussing chambers. Cycloheximide (100 μg/ml) was then added, and amiloride-sensitive Isc was determined at the indicated times. Pseudo-first order rate constants (kapp) for the decay of amiloride-sensitive Isc were determined by regression using SigmaPlot 8.0. B, MDCK cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of Dox for 24 h, and a base-line Isc was established in Ussing chambers. Trypsin (10 μg/ml) was then applied to the apical surface to cleave and activate inactive ENaC channels, and amiloride-sensitive Isc was determined. The data are presented as the changes in Isc with trypsin relative to the total amiloride-sensitive Isc (mean ± S.E., n = 16).

Hsp70 Overexpression Does Not Alter Proportion of Cleaved and Uncleaved ENaC at Apical Surface

The open probability (Po) of ENaC is regulated by proteolysis of the extracellular loops of its α and γ subunits, with both the uncleaved, low Po channel and the cleaved, higher Po channel being delivered to and found at the apical surface (16). Because the uncleaved channel at the surface can be activated by exogenous proteases, we tested whether Hsp70 overexpression may increase the fraction of cleaved ENaC at the surface as a mechanism by which ENaC functional expression was increased. To determine whether this is the case, after a base-line Isc was determined in Ussing chambers, the apical surface of the cells was treated with trypsin (10 μg/ml) to cleave and fully activate all ENaC channels and then with amiloride to determine amiloride-sensitive Isc. Fig. 6B shows that the fraction of total amiloride-sensitive Isc induced by trypsin did not change as a function of added Dox. These data indicate that the fraction of cleaved versus uncleaved ENaC channels at the apical surface was unaffected by Hsp70 overexpression and that altered cleavage is not a contributing mechanism by which Hsp70 promotes ENaC functional expression.

Hsp70 Promotes Processing of Newly Synthesized ENaC Subunits

Given that Hsp70 did not significantly impact the retrieval of ENaC from the membrane or increase the fraction of cleaved channel at the apical surface, we focused our investigation on the role of Hsp70 in ENaC biogenesis. We therefore examined the expression and interaction of newly synthesized ENaC subunits in a pulse-chase assay (Fig. 7). After pulse labeling, ENaC subunits were immunoprecipitated from whole cell lysates at up to 60–90 min of chase. Fig. 7A demonstrates that there was a trend toward newly synthesized β-ENaC persisting longer in Hsp70-overexpressing cells. In addition, in a sequential immunoprecipitation, there was a similar trend toward an increase in the amount of ∼65-kDa (presumably cleaved) α-ENaC associated with β-ENaC with Hsp70 overexpression. Fig. 7B demonstrates that there was a more rapid appearance of the ∼65 kDa α-ENaC when Hsp70 was overexpressed. These data are consistent with Hsp70 promoting the cleavage of α-ENaC that presumably occurs in the Golgi or later compartments by furin after exit from the ER.

FIGURE 7.

Hsp70 promotes interaction between the β- and α-subunits of ENaC. MDCK cells with inducible overexpression of Hsp70-Myc/His were incubated without or with Dox for 24 h. Newly synthesized proteins underwent radiolabeling in a pulse-chase experiment as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, 250 μg of lysates were subjected to two consecutive immunoprecipitation (IP) steps. 10% of the proteins precipitated with anti-V5 (for β-ENaC) were removed for resolution by SDS-PAGE and PhosphorImager analysis, whereas the remainder was used for the second immunoprecipitation step with anti-HA (for α-ENaC) and subsequent SDS-PAGE and PhosphorImager analysis. Desitometric quantification of precipitated β-ENaC and α-ENaC are presented graphically (means ± S.E., n = 3 independent experiments, no differences achieved statistical significance). B, labeled proteins were precipitated with anti-HA, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and revealed by phosphorimaging. These data are representative of four independent experiments. The fluorograms in A and B are from noncontiguous lanes of the same experimental gels.

Hsp70 Increases Association between ENaC and COP II Transport Machinery

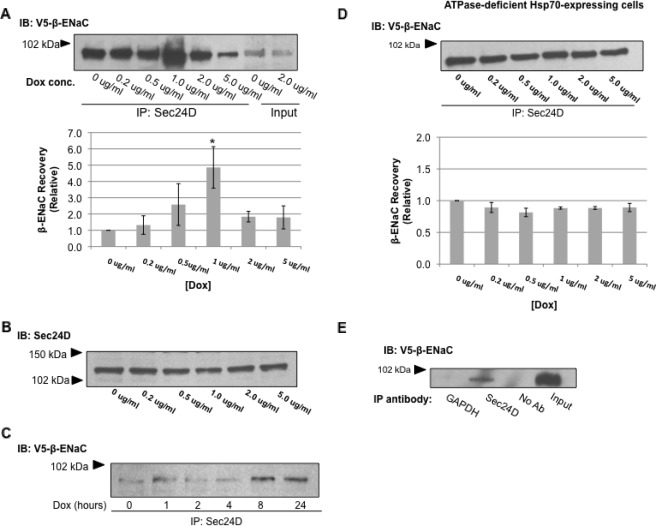

Because our pulse-chase data suggest that Hsp70 may promote α-ENaC cleavage, which presumably occurs in the Golgi or later compartments, we tested whether Hsp70 would increase ENaC association with COP II machinery that carries cargo from ER to Golgi (reviewed in Refs. 31 and 32). We therefore examined the association of ENaC with Sec24D, the cargo recognition component of the COP II machinery. Although the C terminus of α-ENaC controls its exit from the ER and contains a consensus COP II ER exit motif (14), direct evidence of ENaC interaction with COP II or its movement from the ER to the Golgi via COP II has not been published.

To demonstrate this interaction, we immunoprecipitated Sec24D from cell lysates and probed immunoblots of the recovered proteins for V5-β-ENaC. Fig. 8A shows that there is a clear association between Sec24D and β-ENaC and that this association is increased when Hsp70 overexpression is stimulated with 1 μg/ml Dox. This increased association occurs without a change in the whole cell expression of Sec24D as determined by immunoblot (Fig. 8B). To confirm that Hsp70 increases the association between ENaC and Sec24D, a time course experiment was performed. Lysates of cells treated with 1 μg/ml Dox for 0–24 h were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-Sec24D, and the recovered proteins were immunoblotted with anti-V5 to detect β-ENaC (Fig. 8C). Association between Sec24D and V5-β-ENaC increased over these 24 h of Dox treatment. As an additional control, we tested the influence of ATPase-deficient Hsp70 overexpression on this Sec24D/β-ENaC interaction in similar experiments. Overexpression of ATPase-deficient Hsp70 had no effect on the interaction of Sec24D and β-ENaC (Fig. 8D), again suggesting that promotion of this interaction requires a functional Hsp70. We also tested the specificity of this co-precipitation and found that β-ENaC was not detected in the precipitated proteins when anti-Sec24D was either omitted from or replaced by an irrelevant antibody (anti-GAPDH) in the precipitation reaction (Fig. 8E). Together, these data suggest that Hsp70 promotes association of ENaC with COP II and its exit from the ER and therefore increases the delivery of ENaC to the apical cell surface. These data also demonstrate that small (∼2-fold) changes in chaperone abundance can significantly influence the client selection of Sec24D/COP II.

FIGURE 8.

Hsp70 promotes interaction between ENaC and Sec24D, the cargo recognition component of COP II. A, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations (conc.) of Dox for 24 h to induce Hsp70-Myc/His overexpression. The samples underwent immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Sec24D, and β-ENaC was detected in the precipitated proteins by immunoblot (IB) using anti-V5. Input samples represent 10% of the total protein subject to immunoprecipitation. Fold change in V5-β-ENaC co-precipitated with Sec24D was determined by densitometric analysis of precipitated V5 from three independent experiments. The data are presented relative to the control, 0 μg/ml Dox (means ± S.E.). *, p = 0.039 for 1 μg/ml Dox versus 0 μg/ml Dox treatment (ANOVA). B, immunoblots of whole cell lysates were probed with anti-Sec24D after treatment with the indicated amount of Dox for 24 h. C, cells were treated with 1 μg/ml Dox for the indicated times. Cell lysates underwent immunoprecipitation with anti-Sec24D, and β-ENaC was detected in the precipitated proteins by immunoblot using anti-V5. D, MDCK cells with inducible overexpression of ATPase-deficient Hsp70-Myc/His were treated with the indicated amount of Dox for 24 h. Proteins in whole cell lysates underwent immunoprecipitation with anti-Sec24D, and β-ENaC was detected in the precipitated proteins by immunoblot with anti-V5. Densitometric quantification of the precipitated V5 is also depicted relative to the 0 μg/ml Dox treatment. These data are representative of n = 3 independent experiments. E, to test the specificity of the Sec24D/β-ENaC co-precipitation, control co-precipitation experiments were performed with an irrelevant primary antibody (α-GAPDH) or without primary antibody control precipitation, along with a Sec24D immunoprecipitation. The precipitated proteins were detected by immunoblot using anti-V5.

DISCUSSION

ENaC has critical roles in blood pressure regulation in the kidney and in the decreased mucociliary clearance and increased bacterial colonization in the cystic fibrosis airway (1, 6). It is clear that a more comprehensive understanding of ENaC regulation is necessary, because this may lead to therapeutics better able to combat the effects of dysregulated ENaC. Because ENaC subunits must be assembled into a trimeric complex, presumably within the endoplasmic reticulum, and this process is reported to be somewhat inefficient (13), we hypothesized that this assembly process would be readily influenced by molecular chaperones.

We became interested in the 70-kDa heat shock proteins, Hsc70 and Hsp70, because of their altered expression in response to sodium 4-phenylbutyrate, which promotes improved intracellular trafficking of the most common mutation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) ΔF508 (31, 32). We previously demonstrated that Hsp70 and Hsc70, which are ∼85% identical and typically considered to be functionally equivalent, in fact have opposite and antagonistic effects on ENaC in Xenopus oocytes, where Hsp70 promoted and Hsc70 inhibited ENaC functional and surface expression (13). With more recent data that 4-phenylbutyrate also promotes ENaC functional expression in nasal epithelial cells (33), we herein tested whether Hsp70 would similarly promote ENaC functional and apical surface expression.

We selected MDCK cells that had ∼2-fold overexpression of Hsp70 when treated with 1 or 2 μg/ml of Dox for 24 h (Fig. 1). This level of Hsp70 overexpression is similar to that achieved by treating epithelial cells with sodium 4-phenylbutyrate (34, 35), a maneuver that corrects the trafficking of ΔF508-CFTR (36) and increases ENaC trafficking (33) in epithelial cells. Thus, we feel this is an appropriate level of Hsp70 expression to examine in our studies. 2-fold Hsp70 overexpression with 1 μg/ml of Dox did not significantly alter the whole cell expression of all three ENaC subunits (Fig. 2) but did result in increased ENaC functional expression (Fig. 4) and a corresponding increase in the expression of β-ENaC at the apical surface (Fig. 3). Because surface expression of the β-ENaC subunit is dependent upon expression and assembly of the entire ENaC channel (10, 37), we feel that surface expression of this subunit is representative of the fully assembled channel. Together, these data suggest that Hsp70 increases ENaC function by altering its trafficking.

To ensure that these observations were not due to a nonspecific artifact of chaperone overexpression, we performed a number of control experiments in homologous cells engineered to have inducible expression of a nonfunctional, ATPase-deficient Hsp70. Importantly, overexpression of this ATPase-deficient Hsp70 did not lead to increased ENaC functional or apical surface expression (Fig. 5), suggesting that these effects were specifically due to overexpression of a functional chaperone.

With regards to ENaC functional expression, which we defined as amiloride-sensitive Isc in Ussing chambers, we observed a biphasic response when we examined Isc as a function of increasing Dox. Treating cells with 1 or 2 μg/ml Dox caused an increase in amiloride-sensitive Isc that was not seen at the highest dose of Dox examined (5 μg/ml). This was not unexpected, because we previously observed a similar biphasic response in Xenopus oocytes, where co-injection of 10 ng of Hsp70 cRNA promoted ENaC functional and surface expression, whereas co-injection of a greater amount of Hsp70 cRNA (30 ng) inhibited ENaC functional and surface expression (25). This biphasic response may reflect the mechanism by which Hsp70 is regulated under normal conditions. Hsp70 is a stress-induced protein, and its transcription is typically controlled by the transcription factor HSF-1 (heat shock factor 1) in response to increased temperature or cellular stress (38). However, once sufficient Hsp70 protein expression is achieved to bind the client protein, the “excess” Hsp70 can act as a negative feedback mechanism by binding to and inactivating of HSF-1, which decreases in Hsp70 expression. As part of this response, excess Hsp70 may also have other cellular effects, such as altering mRNA turnover via Hsp70 binding to AU repeat elements n mRNA 3′-UTRs (39, 40) or altering mRNA transcription of other HSF-1-responsive genes (41). Regulation of the unfolded protein response by BiP, the ER-luminal Hsp70 homolog, may have a similar mechanism. BiP typically binds and sequesters the unfolded protein response mediators IRE1, ATF6, and PERK. If there is excess unfolded protein in the ER, BiP preferentially binds the unfolded protein and frees these mediators to initiate the unfolded protein response (42).

ENaC functional expression can be regulated either by modification of the total number of channels present at the cell surface (change in N as a result of altered trafficking) or by cleavage of the inactive channels that were delivered to the cell surface, thus modifying the open probability (Po). Because we observed an increase in the functional and surface expression of ENaC with overexpressed Hsp70, we sought to identify which of these mechanisms are impacted by Hsp70. Our data suggest that Hsp70 overexpression alters neither the fraction of cleaved, higher Po versus uncleaved, low Po ENaC at the cell surface (Fig. 6B) nor the rate of retrieval of functional ENaC from the cell surface (Fig. 6A). Although our data do not directly address the fraction of cleaved versus uncleaved ENaC in other compartments of the cell, these data suggested to us that the influence of Hsp70 on ENaC trafficking was most likely exerted during biogenesis and delivery to the cell surface.

ENaC that successfully avoids ERAD and exits the endoplasmic reticulum is transported to the Golgi apparatus, where it can undergo glycosyl processing and proteolytic cleavage by furin (15). This proteolysis is associated with an increase in ENaC Po at the apical epithelial surface. ENaC can, by an unknown mechanism, also reach the cell surface without undergoing glycosyl and proteolytic processing in the Golgi, arriving at the apical membrane in an uncleaved, low Po form (16). Because the fraction of uncleaved versus cleaved channel at the cell surface appears unaffected by Hsp70 overexpression, it is unlikely that Hsp70 influences either the proteolytic cleavage of ENaC or the mechanism by which ENaC can bypass Golgi processing. Instead, we hypothesized that Hsp70 affects ENaC trafficking prior to the Golgi and/or Golgi bypass pathway.

A number of data suggest that CFTR and ENaC trafficking involve similar mechanisms (43–46); therefore we examined mechanisms of CFTR trafficking regulation to test their applicability to ENaC trafficking. CFTR that leaves the endoplasmic reticulum is trafficked via a COP II-dependent mechanism (47). We therefore examined the interaction of the ENaC with Sec24D, the cargo selection molecule of the COP II machinery (48, 49), and found that Sec24D associated most strongly with β-ENaC when cells were treated with 1 μg/ml of Dox (Fig. 8A) and that this interaction increased during the initial 24 h of Dox-induced Hsp70 overexpression (Figs. 1A and 8C). Again, the ATPase function of Hsp70 was required for these effects, because ATPase-deficient Hsp70 overexpression did not alter the association of ENaC with Sec24D (Fig. 8D). These data do not address whether Sec24D interacts directly with β-ENaC or with another ENaC subunit within αβγ-ENaC. The latter possibility is more plausible, because a region in the C terminus of the α-ENaC controls the ER exit of ENaC and contains a putative COP II interaction motif (14). Furthermore, the ENaC subunits should likely associate prior to exit from the ER. Nevertheless, these data are the first direct evidence of an interaction between ENaC and a COP II component and suggest that ENaC traffics from the ER to the Golgi via COP II.

As newly synthesized ENaC subunits undergo ERAD unless assembled into channels, our pulse-chase data (Fig. 7) may suggest that Hsp70 overexpression somewhat stabilizes and decreases the ERAD of newly synthesized ENaC subunits. However, these data do not specifically address whether there is decreased ERAD (11–13, 50) or an increase in channel assembly efficiency. Decreased ERAD would result in an increase in the concentration of newly synthesized ENaC subunits, leading to increased biogenesis of the whole channel. Alternatively, Hsp70 overexpression could primarily result in a greater proportion of newly synthesized ENaC subunits that are appropriately conformed for subunit association and assembly, which would also result in an increase in channel biogenesis. Once properly assembled, ENaC becomes a client for COP II cargo machinery and exits the ER. When Hsp70 levels are increased, the amount of properly assembled ENaC increases, leading to an increased amount of ENaC exiting the ER and being delivered to the apical cell surface.

In summary, our data are consistent with Hsp70 increasing ENaC functional and surface expression by increasing the number of ENaC channels at the apical surface of mammalian epithelial cells. This is in agreement with our previous results in Xenopus oocytes suggesting that Hsp70 increased ENaC functional and surface expression (25). Our data does not suggest, however, that Hsp70 affects either fractional cleavage of ENaC at the cell surface or its rate of retrieval from the cell surface. Instead, Hsp70 appears to promote the interaction of newly synthesized ENaC with COP II ER export machinery that facilitates ENaC delivery to the Golgi or later compartments. These data are the first to demonstrate such an interaction of ENaC with COP II components and further fundamentally suggest that relatively small changes in chaperone abundance (here, an approximately 2-fold overexpression of functional Hsp70) can result in significant shifts in the clientele of trafficking machinery.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants T32 DK07748 (to R. A. C.), R01 DK58046, (to R. C. R.), and R01 DK73185 (to R. C. R.).

- ENaC

- epithelial sodium channel

- Hsp70

- stress-induced 70-kDa heat shock protein

- CFTR

- cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- Dox

- doxycycline

- MDCK

- Madin-Darby canine kidney cells

- COP II

- coat complex II

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

- ER-associated degradation pathway

- RIPA

- radioimmune precipitation assay

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rossier B. C. (2004) The epithelial sodium channel. Activation by membrane-bound serine proteases. Proc. Am. Thorac Soc. 1, 4–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossier B. C., Pradervand S., Schild L., Hummler E. (2002) Epithelial sodium channel and the control of sodium balance. Interaction between genetic and environmental factors. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 877–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hummler E. (2003) Epithelial sodium channel, salt intake, and hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 5, 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pradervand S., Vandewalle A., Bens M., Gautschi I., Loffing J., Hummler E., Schild L., Rossier B. C. (2003) Dysfunction of the epithelial sodium channel expressed in the kidney of a mouse model for Liddle syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 2219–2228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rossi E., Farnetti E., Debonneville A., Nicoli D., Grasselli C., Regolisti G., Negro A., Perazzoli F., Casali B., Mantero F., Staub O. (2008) Liddle's syndrome caused by a novel missense mutation (P617L) of the epithelial sodium channel beta subunit. J. Hypertens. 26, 921–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsui H., Grubb B. R., Tarran R., Randell S. H., Gatzy J. T., Davis C. W., Boucher R. C. (1998) Evidence for periciliary liquid layer depletion, not abnormal ion composition, in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis airways disease. Cell 95, 1005–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jasti J., Furukawa H., Gonzales E. B., Gouaux E. (2007) Structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1 at 1.9 A resolution and low pH. Nature 449, 316–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stewart A. P., Haerteis S., Diakov A., Korbmacher C., Edwardson J. M. (2011) Atomic force microscopy reveals the architecture of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 31944–31952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canessa C. M., Merillat A. M., Rossier B. C. (1994) Membrane topology of the epithelial sodium channel in intact cells. Am. J. Physiol. 267, C1682–C1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canessa C. M., Schild L., Buell G., Thorens B., Gautschi I., Horisberger J. D., Rossier B. C. (1994) Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature 367, 463–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kashlan O. B., Mueller G. M., Qamar M. Z., Poland P. A., Ahner A., Rubenstein R. C., Hughey R. P., Brodsky J. L., Kleyman T. R. (2007) Small heat shock protein αA-crystallin regulates epithelial sodium channel expression. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 28149–28156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Staub O., Gautschi I., Ishikawa T., Breitschopf K., Ciechanover A., Schild L., Rotin D. (1997) Regulation of stability and function of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) by ubiquitination. EMBO J. 16, 6325–6336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Valentijn J. A., Fyfe G. K., Canessa C. M. (1998) Biosynthesis and processing of epithelial sodium channels in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 30344–30351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mueller G. M., Kashlan O. B., Bruns J. B., Maarouf A. B., Aridor M., Kleyman T. R., Hughey R. P. (2007) Epithelial sodium channel exit from the endoplasmic reticulum is regulated by a signal within the carboxyl cytoplasmic domain of the α subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33475–33483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughey R. P., Bruns J. B., Kinlough C. L., Harkleroad K. L., Tong Q., Carattino M. D., Johnson J. P., Stockand J. D., Kleyman T. R. (2004) Epithelial sodium channels are activated by furin-dependent proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18111–18114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hughey R. P., Bruns J. B., Kinlough C. L., Kleyman T. R. (2004) Distinct pools of epithelial sodium channels are expressed at the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48491–48494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Caldwell R. A., Boucher R. C., Stutts M. J. (2004) Serine protease activation of near-silent epithelial Na+ channels. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C190–C194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caldwell R. A., Boucher R. C., Stutts M. J. (2005) Neutrophil elastase activates near-silent epithelial Na+ channels and increases airway epithelial Na+ transport. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 288, L813–L819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adebamiro A., Cheng Y., Johnson J. P., Bridges R. J. (2005) Endogenous protease activation of ENaC. Effect of serine protease inhibition on ENaC single channel properties. J. Gen. Physiol. 126, 339–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bruns J. B., Carattino M. D., Sheng S., Maarouf A. B., Weisz O. A., Pilewski J. M., Hughey R. P., Kleyman T. R. (2007) Epithelial Na+ channels are fully activated by furin- and prostasin-dependent release of an inhibitory peptide from the γ-subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6153–6160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jovov B., Berdiev B. K., Fuller C. M., Ji H. L., Benos D. J. (2002) The serine protease trypsin cleaves C termini of β- and γ-subunits of epithelial Na+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 4134–4140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kamynina E., Debonneville C., Bens M., Vandewalle A., Staub O. (2001) A novel mouse Nedd4 protein suppresses the activity of the epithelial Na+ channel. FASEB J. 15, 204–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kamynina E., Debonneville C., Hirt R. P., Staub O. (2001) Liddle's syndrome. A novel mouse Nedd4 isoform regulates the activity of the epithelial Na+ channel. Kidney Int. 60, 466–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Knight K. K., Olson D. R., Zhou R., Snyder P. M. (2006) Liddle's syndrome mutations increase Na+ transport through dual effects on epithelial Na+ channel surface expression and proteolytic cleavage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2805–2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goldfarb S. B., Kashlan O. B., Watkins J. N., Suaud L., Yan W., Kleyman T. R., Rubenstein R. C. (2006) Differential effects of Hsc70 and Hsp70 on the intracellular trafficking and functional expression of epithelial sodium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5817–5822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hendershot L., Wei J., Gaut J., Melnick J., Aviel S., Argon Y. (1996) Inhibition of immunoglobulin folding and secretion by dominant negative BiP ATPase mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 5269–5274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hendershot L. M., Wei J. Y., Gaut J. R., Lawson B., Freiden P. J., Murti K. G. (1995) In vivo expression of mammalian BiP ATPase mutants causes disruption of the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 283–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hanwell D., Ishikawa T., Saleki R., Rotin D. (2002) Trafficking and cell surface stability of the epithelial Na+ channel expressed in epithelial Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 9772–9779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lu C., Pribanic S., Debonneville A., Jiang C., Rotin D. (2007) The PY motif of ENaC, mutated in Liddle syndrome, regulates channel internalization, sorting and mobilization from subapical pool. Traffic 8, 1246–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morris R. G., Schafer J. A. (2002) cAMP increases density of ENaC subunits in the apical membrane of MDCK cells in direct proportion to amiloride-sensitive Na+ transport. J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 71–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Duden R. (2003) ER-to-Golgi transport. COP I and COP II function (Review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 20, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barlowe C. (2002) COPII-dependent transport from the endoplasmic reticulum. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prulière-Escabasse V., Planès C., Escudier E., Fanen P., Coste A., Clerici C. (2007) Modulation of epithelial sodium channel trafficking and function by sodium 4-phenylbutyrate in human nasal epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34048–34057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Choo-Kang L. R., Zeitlin P. L. (2001) Induction of HSP70 promotes ΔF508 CFTR trafficking. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 281, L58–L68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suaud L., Miller K., Panichelli A. E., Randell R. L., Marando C. M., Rubenstein R. C. (2011) 4-Phenylbutyrate stimulates Hsp70 expression through the Elp2 component of elongator and STAT-3 in cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 45083–45092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rubenstein R. C., Egan M. E., Zeitlin P. L. (1997) In vitro pharmacologic restoration of CFTR-mediated chloride transport with sodium 4-phenylbutyrate in cystic fibrosis epithelial cells containing ΔF508-CFTR. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2457–2465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Firsov D., Schild L., Gautschi I., Mérillat A. M., Schneeberger E., Rossier B. C. (1996) Cell surface expression of the epithelial Na channel and a mutant causing Liddle syndrome. A quantitative approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 15370–15375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shi Y., Mosser D. D., Morimoto R. I. (1998) Molecular chaperones as HSF1-specific transcriptional repressors. Genes Dev. 12, 654–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilson G. M., Sutphen K., Bolikal S., Chuang K. Y., Brewer G. (2001) Thermodynamics and kinetics of Hsp70 association with A + U-rich mRNA-destabilizing sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 44450–44456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Laroia G., Cuesta R., Brewer G., Schneider R. J. (1999) Control of mRNA decay by heat shock-ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Science 284, 499–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abravaya K., Myers M. P., Murphy S. P., Morimoto R. I. (1992) The human heat shock protein Hsp70 interacts with HSF, the transcription factor that regulates heat shock gene expression. Genes Dev. 6, 1153–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kaufman R. J. (2002) Orchestrating the unfolded protein response in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 1389–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lang F., Henke G., Embark H. M., Waldegger S., Palmada M., Böhmer C., Vallon V. (2003) Regulation of channels by the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase. Implications for transport, excitability and cell proliferation. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 13, 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dieter M., Palmada M., Rajamanickam J., Aydin A., Busjahn A., Boehmer C., Luft F. C., Lang F. (2004) Regulation of glucose transporter SGLT1 by ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 and kinases SGK1, SGK3, and PKB. Obes. Res. 12, 862–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wagner C. A., Ott M., Klingel K., Beck S., Melzig J., Friedrich B., Wild K. N., Bröer S., Moschen I., Albers A., Waldegger S., Tümmler B., Egan M. E., Geibel J. P., Kandolf R., Lang F. (2001) Effects of the serine/threonine kinase SGK1 on the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) and CFTR. Implications for cystic fibrosis. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 11, 209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sato J. D., Chapline M. C., Thibodeau R., Frizzell R. A., Stanton B. A. (2007) Regulation of human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) by serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK1). Cell Physiol. Biochem. 20, 91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang X., Matteson J., An Y., Moyer B., Yoo J. S., Bannykh S., Wilson I. A., Riordan J. R., Balch W. E. (2004) COPII-dependent export of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator from the ER uses a di-acidic exit code. J. Cell Biol. 167, 65–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Miller E., Antonny B., Hamamoto S., Schekman R. (2002) Cargo selection into COPII vesicles is driven by the Sec24p subunit. EMBO J. 21, 6105–6113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Miller E. A., Beilharz T. H., Malkus P. N., Lee M. C., Hamamoto S., Orci L., Schekman R. (2003) Multiple cargo binding sites on the COPII subunit Sec24p ensure capture of diverse membrane proteins into transport vesicles. Cell 114, 497–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nishikawa S., Brodsky J. L., Nakatsukasa K. (2005) Roles of molecular chaperones in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) quality control and ER-associated degradation (ERAD). J. Biochem. 137, 551–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]