Background: Binding of SIRPα to its ligands CD47 and surfactant protein D (Sp-D) regulates many myeloid cell functions.

Results: Sp-D binds to N-glycosylated sites in the membrane-proximal domain of SIRPα and SIRPβ, another related SIRP.

Conclusion: Sp-D binds to a site on SIRPα distant from that of CD47.

Significance: Multiple ligand binding sites on SIRPα may afford differential regulation of receptor function.

Keywords: Glycosylation, Neutrophil, Protein Complexes, Receptors, Surfactant Protein D, SIRPα, SIRPβ

Abstract

Signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα), a highly glycosylated type-1 transmembrane protein, is composed of three immunoglobulin-like extracellular loops as well as a cytoplasmic tail containing three classical tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs. Previous reports indicate that SIRPα binds to humoral pattern recognition molecules in the collectin family, namely surfactant proteins D and A (Sp-D and Sp-A, respectively), which are heavily expressed in the lung and constitute one of the first lines of innate immune defense against pathogens. However, little is known about molecular details of the structural interaction of Sp-D with SIRPs. In the present work, we examined the molecular basis of Sp-D binding to SIRPα using domain-deleted mutant proteins. We report that Sp-D binds to the membrane-proximal Ig domain (D3) of SIRPα in a calcium- and carbohydrate-dependent manner. Mutation of predicted N-glycosylation sites on SIRPα indicates that Sp-D binding is dependent on interactions with specific N-glycosylated residues on the membrane-proximal D3 domain of SIRPα. Given the remarkable sequence similarity of SIRPα to SIRPβ and the lack of known ligands for the latter, we examined Sp-D binding to SIRPβ. Here, we report specific binding of Sp-D to the membrane-proximal D3 domain of SIRPβ. Further studies confirmed that Sp-D binds to SIRPα expressed on human neutrophils and differentiated neutrophil-like cells. Because the other known ligand of SIRPα, CD47, binds to the membrane-distal domain D1, these findings indicate that multiple, distinct, functional ligand binding sites are present on SIRPα that may afford differential regulation of receptor function.

Introduction

Signal regulatory proteins (SIRPs)3 are glycosylated type-1 transmembrane receptors belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily. Three members have been described so far, SIRPα, SIRPβ, and SIRPγ. The former two are expressed mainly on myeloid cells such as neutrophils (PMNs), macrophages, and dendritic cells as well as on neurons (1). SIRPα, the best characterized of the SIRPs, is expressed on the cell surface as a noncovalently linked cis-homodimer and contains three extracellular Ig loops (2). The membrane-distal loop termed D1 consists of an immunoglobulin variable-type domain, whereas the membrane-proximal D2 and D3 loops have structures consistent with immunoglobulin constant domains. There is a single pass transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic tail containing an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) that, in some cells, has been shown to interact with SHP-1 and SHP-2 (Src homology region domain-containing phosphatase), tyrosine phosphatases, therefore preventing signaling pathways regulated by some tyrosine kinases (3–5). Thus, SIRPα is an inhibitory receptor, whose activation leads to inhibition of several important myeloid cell functions such as phagocytosis by macrophages or cytokine production (6–8).

A major SIRPα ligand, CD47, is a membrane receptor with an unusual immunoglobulin-like structure that has been shown to interact with the distal Ig domain of SIRPα (D1) (9–12). Interestingly, splenic macrophages from CD47-expressing mice clear infused blood cells from CD47−/− mice, strongly suggesting that interaction of SIRPα with CD47 contributes to recognition of self (13). Two other SIRPα ligands have been reported in the literature, namely surfactant proteins D and A (Sp-D and Sp-A), both of which belong to the collectin family. Collectins represent a family of soluble humoral pattern recognition molecules capable of binding the carbohydrate moieties of microorganisms and therefore participate in the immune response against pathogens. Pulmonary surfactant is composed mainly of phospholipids, but also contains various surfactant proteins including Sp-D and representing 10% of the total surfactant pool (14). Sp-D, the focus of this study, consists of a central collagenous domain involved in oligomerization in a trimeric structure and a globular C-terminal lectin-like domain, responsible for carbohydrate recognition (CRD, carbohydrate recognition domain). The trimeric helical structure of Sp-D further oligomerizes into a tetrameric structure that is generally thought to facilitate recognition of bacterial and viral pathogens. The globular trimeric CRD has a high affinity for clustered sugars and specificity for saccharides such as maltose or glucose (15, 16). The ability to differentiate some carbohydrates from others has been suggested to represent an ancient form of pattern recognition that has evolved to discriminate self from foreign pathogen invaders. Indeed, Sp-D is an important component of the pulmonary surfactant involved in host innate immunity capable of binding most Gram-negative bacteria as well as several Gram-positive bacteria, leading to increased opsonization and killing of bacteria (14, 17, 18). Sp-D usually binds to its ligands by a CRD-dependent cell binding requiring calcium and inhibited by several saccharides (18, 19). Besides a high level of expression in the lungs, Sp-D expression has also been reported in the small and large intestinal epithelial cells of humans, pigs, rats and, to a lesser extent mice (20–23). Interestingly, Sp-D expression in these locations is limited to epithelial cells in contact with an environment (17). Sp-D function in the intestine, however, remains unknown.

Surfactant protein D has been reported to bind to macrophage SIRPα (24, 25). Sp-D binding to SIRPα was reported to activate SHP-1 phosphorylation leading to the inhibition of p38 activation and decreased cytokine production (24). However, little is known about the structural interaction of Sp-D with SIRPα and more specifically which SIRPα domain(s) binds to Sp-D.

Another closely related family member, SIRPβ, shares a high degree of homology with the SIRPα ectodomain, and whether Sp-D is also capable of binding to SIRPβ has not yet been studied. Intriguingly, no ligand has been described for SIRPβ so far. SIRPβ is a cysteine-linked homodimer with three immunoglobulin-like extracellular loops. SIRPβ, however, has a very short cytoplasmic tail, and the transmembrane domain has been reported to interact with DAP12, an adaptor protein containing an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) in human monocytic cell lines as well as in peritoneal macrophages (26, 27). DAP12 has been shown to trigger tyrosine kinase, Syk, leading to activation of MAPK (27, 28). Thus, SIRPβ has been proposed to function as an activating receptor promoting macrophage phagocytosis through DAP12 (27).

In this paper, using a panel of eukaryotically expressed recombinant SIRPα domains, we report that Sp-D binds to SIRPα D3 domain in a calcium- and saccharide-dependent manner. Furthermore, we show that Sp-D binds to all four N-glycosylated sites within or in immediate proximity of the D3 domain of SIRPα, with strongest binding to a N-glycosylated site located at Asn-240 on SIRPα. We show that Sp-D binds to and co-localizes with SIRPα expressed on CHO-SIRPα cells as well as to human promyelocytic cells and PMNs. Given the high degree of structural similarity of SIRPα with SIRPβ, we report that Sp-D avidly binds to the D3 domain of SIRPβ which opens new interpretations to the relative contributions of SIRP proteins to the regulation of acute inflammatory responses in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

Recombinant human Sp-D (R&D Systems) is commercially available. The following antibodies were used in this study: monoclonal mouse anti-human Sp-D (R&D Systems) and polyclonal goat anti-human Sp-D (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Rabbit polyclonal antiserum against recombinant SIRPα ectodomain was produced by Covance Research Products. Monoclonal antibodies against SIRPα D1 (SAF17.2) and SIRPα D3 (SAF4.2) have been described previously (9). LPS from Salmonella minnesota R595 was obtained from List Biological Laboratories.

Cell Lines

Human promyelocytic cell lines (HL60 and PLB985) used in this study were described previously (29, 30). They were differentiated as described previously (31). Briefly, they were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1.25% dimethyl sulfoxide for 6–7 days. Human embryonic kidney cell line with T antigen (HEK293T) and wild-type Chinese hamster ovary cell line (CHO-K1) were purchased from ATCC. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with plasmid pcDNA3 containing the SIRPα gene corresponding to GenBank entry BC 029662.1. The GenBank entry for SIRPβ constructs was NM 006065. Cells expressing the plasmid were selected with G418 and cloned. Clones stably expressing SIRPα were selected by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) as described previously (2).

Generation of Truncated and Mutated SIRPα Plasmid Constructs

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by overlap extension using complementary PCR primers containing the mutation (32). Forward and reverse end primers were designed with HindIII and BamHI sites. DNA constructs encoding various ectodomains of SIRPα tagged with His10 (SIRPα-His) were cloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) as described previously (9). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Purification of Recombinant Proteins

HEK293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Transient transfections of HEK293T cells with SIRPα plasmids were conducted using polyethylenimine (PEI) as described previously (33). His10-tagged recombinant proteins such as SIRPα D1D2D3-His were purified by gravity-flow chromatography using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Qiagen). Proteins were characterized by SDS-PAGE, and protein purity was assessed by staining the gel with Coomassie Blue.

In Vitro Binding Assays

In vitro binding assays were performed as described previously with several changes (34). Immulon II 96-well plates were coated overnight at 4 °C with 2 μg/ml SIRPα D1D2D3-His and blocked for 1 h with 3% BSA. 2 μg/ml rhSp-D in PBS containing 0.1 g/liter CaCl2, 0.1 g/liter MgCl2 6H2O (PBS with Ca2+/Mg2+), and 9% BSA were added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, 1 μg/ml monoclonal anti-human Sp-D in PBS containing Ca2+/Mg2+ and 3% BSA was added to the wells and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After extensive washes, 0.4 μg/ml horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) in PBS containing Ca2+/Mg2+ and 3% BSA was used to detect the primary antibody. Peroxidase was detected with one-step Ultra TMB ELISA (Thermo Scientific). The reaction was stopped with 1 m H2SO4, and the A405 nm was measured.

CD47 inhibition of Sp-D binding to SIRPα was performed as follows. Immulon II wells were coated with SIRPα D1D2D3-His at 1 μg/ml and further incubated with supernatants of transfected CHO cells containing soluble CD47 ectodomain fused to alkaline phosphatase (CD47AP) (34). Sp-D binding was assessed with mAb anti-SP-D as described above. Conversely, SIRPα D1D2D3-His-coated wells were incubated with Sp-D prior to CD47AP addition, and CD47 binding was evaluated by colorimetry using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) at 405 nm.

Production of Mouse Anti-human SIRPα D3-His

Female BALB/c mice were immunized by injecting 50 μg of purified human SIRPα D3-His emulsified with complete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich). Four boosts of 50 μg of SIRPα D3-His emulsified in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich) were subsequently administered intraperitoneally. Serum specificity was determined by ELISA. In brief, Immulon II 96-well plates were coated overnight at 4 °C with 20 μg/ml goat anti-rabbit IgG, γ-specific (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and blocked as mentioned previously. 20 μg/ml rabbit Fc-tagged SIRPα proteins were then added to the well before incubation with mouse anti-D3 serum diluted 1:1000. Detection was performed by adding 0.4 μg/ml peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, light chain-specific (Jackson Laboratories). Color was developed by ABTS (Sigma-Aldrich) and read at 405 nm.

To further determine serum specificity, and more specifically, CD47 binding in the presence of the anti-D3 serum, microtiter wells were coated with 0.5 μg/ml SIRPα D1D2D3 ectodomain overnight followed by incubation with a 1:25 dilution of anti-SIRPα D3 serum or comparable amounts of normal control serum. Cell culture supernatant containing soluble CD47AP was added to the wells. CD47 binding was further measured using p-nitrophenyl phosphate.

Serum inhibition binding assays were performed similarly. Coated SIRPα proteins were incubated with sera. Sp-D binding was detected with 1 μg/ml polyclonal goat anti-human Sp-D and 0.4 μg/ml peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), followed by Ultra TMB ELISA.

Immmunoblotting

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (9) using 5% Western blocking reagent (Roche Applied Science). Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF; Bio-Rad) membrane was incubated with mAbs anti-SIRPα (SAF17.2 or SAF4.2) and the addition of goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) conjugated to peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and revealed by Western blotting chemiluminescence (Roche Applied Science).

Far Western Blot Analysis

Far Western blotting was carried out according to a previously described procedure with slight modifications (35). 500 ng of denatured SIRP proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with a binding/blocking buffer (20 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm CaCl2, 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 5% BSA) for 3–4 h and incubated overnight at room temperature in binding/blocking buffer containing 5 μg/ml rhSp-D. Sp-D bound to the membrane was further detected with 0.1 μg/ml polyclonal anti-human Sp-D and 0.4 μg/ml peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG followed by chemiluminescence.

Treatment by N-Glycosidase F and O-Glycosidase

500 ng of denatured His-tagged SIRPα protein was incubated with 200 units/ml N-glycosidase F from Elizabethkingia miricola (Sigma-Aldrich) in a buffer containing 150 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 12 mm 1,10-phenanthroline, and 1.2% Nonidet P-40 overnight at 30 °C. To remove O-glycosylated carbohydrates, SIRPα was incubated with 250 milliunits/ml neuraminidase from Arthrobacter ureafaciens (Roche Applied Science) and 125 milliunits/ml O-glycosidase from Streptococcus pneumoniae (Roche Applied Science) in 50 mm sodium acetate, pH 5.0, overnight at 37 °C.

Preparation of Human Blood PMNs

Human PMNs were freshly isolated from healthy donors as described previously (36). In brief, blood was subjected to density gradient centrifugation with Polymorphprep (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway). Remaining erythrocytes were lysed by hypotonic lysis. PMN activation was induced with 0.2 μm phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 10 min at 37 °C.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells were incubated with 3 μg/ml rhSp-D in either DMEM containing 9% BSA (for CHO cells) or RPMI with 3% BSA (for suspension cells) for 2 h at room temperature and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 40 min at room temperature. A permeabilization step of 0.1% Triton X-100 in Hanks' balanced salt solution containing CaCl2 (HBSS+) for 10 min at room temperature was included when nucleus staining was applied. After a blocking step, cells were incubated with primary antibodies. SIRPα ectodomain was stained with a polyclonal rabbit anti-human SIRPα serum and Sp-D by monoclonal mouse anti-human Sp-D before to be subsequently labeled with 2 μg/ml secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Invitrogen). Nuclei were stained using 0.1 μm To-Pro3-iodide (Invitrogen) in HBSS+ (15 min at room temperature). Suspension cells were mounted in 1:1 (v/v) phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and were visualized on a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY).

Statistical Analysis

The statistical method used to analyze results was a Student's t test with two-tailed distribution using GraphPad Prism software. Results are expressed in mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

Sp-D Binds to SIRPα D3

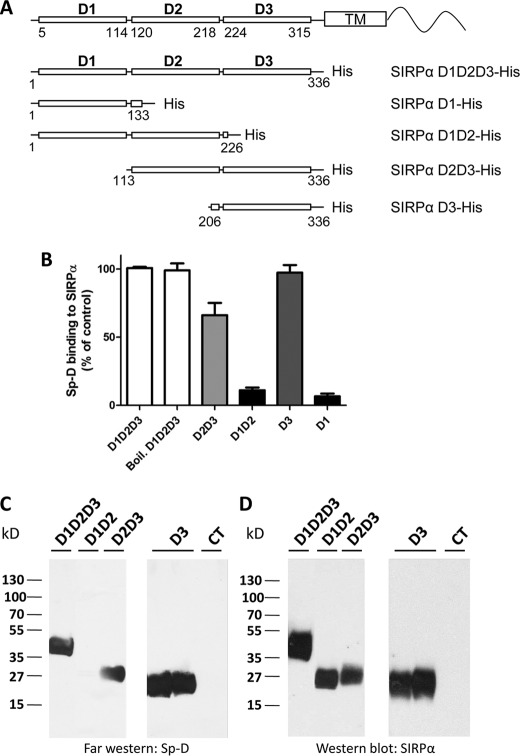

To determine which extracellular domain(s) is involved in Sp-D binding, mutant proteins containing various domains were generated and expressed in HEK293T cells. His-tagged whole or truncated extracellular domains were generated as shown in Fig. 1A and purified as detailed under “Materials and Methods.” Using an in vitro binding experiment as described previously (9), solutions of purified recombinant His-tagged proteins were incubated in microtiter plates to coat the wells. Subsequent ELISAs confirmed binding of the recombinant proteins. As shown in Fig. 1B, Sp-D was observed to label the SIRPα D1D2D3 ectodomain as well as the D2D3 and D3 domains, whereas significantly reduced binding was observed for the D1 and D1D2 domains. To further confirm that Sp-D binds to the D3 domain, we performed a far Western blot analysis. For these experiments, various truncated or complete extracellular domains of SIRPα were separated by electrophoresis and blotted on a membrane further incubated with Sp-D. As shown in Fig. 1, C and D, Sp-D bound to D3, but not to the D1D2 domains, confirming the in vitro binding experiments.

FIGURE 1.

Sp-D binds to the D3 domain of SIRPα. A, maps of soluble His-tagged SIRPα fusion proteins. Domains are in bold, whereas numbers indicate amino acid residues delineating the three domains according to the crystal structure of Hatherley et al. (48), and amino acids for domain-specific mutant constructs. B, in vitro binding assay of Sp-D to various SIRPα domains immobilized on an Immulon plate and assessed colorimetrically by using a one-step Ultra TMB ELISA. SIRPα D1D2D3 A405 was used as 100%. Boiled SIRPα was heated for 5 min at 100 °C. C, far Western blot analysis for Sp-D binding to various SIRPα domains. SIRPα domains were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane, which was subsequently incubated with Sp-D. D, Western blot of stripped membrane (C) using SIRPα mAb SAF17.2 and SAF4.2 (9) confirming the presence of protein in each lane. An unrelated protein (JAM-L) was used as a negative control (CT). Results are representative of one of three independent experiments. Error bars, S.E.

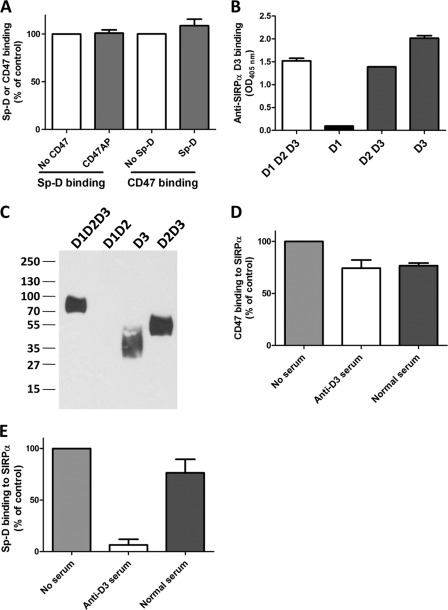

Another SIRPα ligand known to bind to a different region of the extracellular domain of SIRPα is CD47. In particular, CD47 has been shown to bind to the membrane distal D1 domain (9–12). As can be seen in Fig. 2A, CD47 binding to SIRPα did not impair Sp-D binding, nor was Sp-D binding to SIRPα inhibited by CD47, strongly suggesting that the D1 domain is not involved in Sp-D binding. However, treatment of SIRPα D1D2D3-His by SAF4.2, a monoclonal antibody specific for SIRPα D3, did not inhibit Sp-D binding either (data not shown). We hypothesized that the epitope recognized by this antibody was different from the Sp-D binding site(s). To investigate this possibility, we generated a polyclonal anti-human D3 serum by immunizing BALB/c mice with purified human D3-His protein. The polyclonal serum was specific for SIRPα D3 domain because it was observed to bind selectively to recombinant D3 domain (Fig. 2, B and C). Furthermore, binding specificity of anti-D3 antiserum to D3 and not D1 was verified by experiments, demonstrating that preincubation of SIRPα D1D2D3 with this pAb did not inhibit CD47 binding (Fig. 2D). Importantly, anti-D3 pAb was effective in dramatically decreasing Sp-D binding (Fig. 2E), which supports SIRPα D3-mediated binding interactions as being critical for Sp-D binding. Taken together, these results indicate that Sp-D associates with the membrane-proximal immunoglobulin loop D3 on SIRPα.

FIGURE 2.

Sp-D binding to SIRPα is not impaired by CD47 binding but is inhibited by an anti-human SIRPα D3 serum. A, in vitro binding assay showing that CD47 and Sp-D can both bind to SIRPα independently. Microtiter wells coated with SIRPα were first incubated with either recombinant ectodomain of CD47 or purified Sp-D, blocked, and then incubated with respective ligands to assess the binding of Sp-D (after incubation with CD47) or CD47 (after incubation with Sp-D). B, in vitro binding assay confirming anti-SIRPα D3 serum specificity for the D3 domain. Goat anti-rabbit IgG, γ-specific, was coated on microtiter plates, blocked, and subsequently incubated with rabbit Fc-tagged SIRPα WT or mutant proteins. Incubation with diluted anti-SIRPα D3 serum generated in BALB/c mice as detailed under “Materials and Methods” was followed by addition of peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. IgG binding was further determined by colorimetry using ABTS at 405 nm. C, Western blot of various SIRPα domains revealed with the mouse anti-human SIRPα D3 serum diluted 1:4000 followed by goat anti-mouse as described under “Materials and Methods.” D, CD47 binding to immobilized SIRPα D1D2D3 incubated with mouse normal and anti-D3 sera. Binding of CD47-AP was evaluated by colorimetry using p-nitrophenyl phosphate. E, Sp-D binding to immobilized SIRPα D1D2D3 incubated with normal and anti-D3 sera determined as indicated in Fig. 1B. Results are representative of one of three independent experiments. Error bars, S.E.

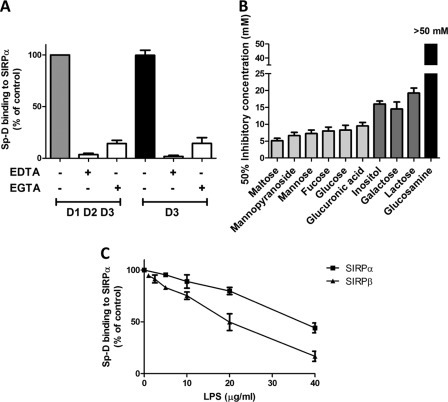

Sp-D Binding to SIRPα Is Calcium-dependent, Carbohydrate-specific, and Inhibited by LPS

Because Sp-D is a lectin-like molecule that has been shown to require calcium for pathogen binding, we further investigated whether Sp-D requires calcium to interact with SIRPα. As indicated in Fig. 3A, Sp-D binding to SIRPα, or a mutant containing only the D3 domain, was inhibited by 5 mm EDTA or EGTA, suggesting that Sp-D binding to SIRPα D3 is indeed calcium-dependent. In addition, the Sp-D binding has been reported to be mediated through its CRD that is sensitive to specific sugar residues. Thus, we examined the ability of various sugars to inhibit Sp-D association to SIRPα. As shown in Fig. 3B, mono- or disaccharides containing a glucosyl group such as glucose, maltose, and glucuronic acid as well as carbohydrates derived from mannose, e.g. methyl α-d-mannopyranoside strongly inhibited Sp-D binding to SIRPα. On the other hand, carbohydrates derived from galactose, i.e. lactose were less capable of inhibiting Sp-D, whereas glucosamine did not diminish Sp-D binding (Fig. 3B). These results are consistent with a previous report showing that carbohydrates with glucosyl residues are strong inhibitors, whereas glucosamine and galactosamine are weaker inhibitors (16). Our data are thus consistent with, Sp-D binding to SIRPα in a calcium as well as carbohydrate-dependent manner.

FIGURE 3.

Sp-D binding to SIRPα is calcium-dependent, sugar-specific, and inhibited by LPS. A, in vitro Sp-D binding to SIRPα is inhibited by EDTA and EGTA. Calcium chelators (5 mm) were added at the same time as Sp-D. Sp-D binding to microtiter wells coated with SIRPα D1D2D3 or D3 domains was assessed as in Fig. 1B. B, in vitro binding assay of Sp-D in presence of solutions of various carbohydrates is shown. Graded concentrations of sugars were added at the same time as Sp-D, and the sugar concentration inhibiting 50% of Sp-D binding was then calculated. C, in vitro binding assay of Sp-D to SIRPα and SIRPβ in presence of LPS was performed by adding increasing concentrations of LPS from S. minnesota at the same time as Sp-D. Error bars, S.E.

Sp-D is also known to bind with high affinity to rough LPS, the major component of Gram-negative cell walls (19). Therefore, we assessed whether Sp-D binding to SIRPα was affected by LPS from S. minnesota Re mutant that expresses a truncated rough LPS known to be a strong ligand for Sp-D (37). The Re mutant expresses the shortest form of LPS among different S. minnesota strains containing only lipid A and 3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid (38). As shown in Fig. 3C, increasing concentrations of LPS significantly decreased Sp-D binding to SIRPα. We observed 50% inhibition of Sp-D binding to SIRPα at a concentration of ∼40 μg/ml LPS, which is consistent with previous reports (39).

Sp-D Binds to N-Linked Glycans of SIRPα

We observed that Sp-D bound strongly to boiled SIRPα (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the structure recognized by Sp-D is not a conformational epitope of the protein. Indeed, the CRD of Sp-D detects carbohydrates including those expressed on glycosylated proteins (25). Because SIRPα is heavily glycosylated, we examined whether Sp-D detected glycans present on SIRPα in an N-linked or O-linked configuration. For these experiments, full-length extracellular domain mutants of SIRPα D1D2D3-His were digested by either N- or O-glycosidases to remove N-linked or O-linked sugars, respectively. As can be seen in supplemental Fig. S1B, the N-glycosidase-treated SIRPα molecular mass was significantly lower than that of nontreated samples, indicating that N-glycosidase F removed N-linked glycans of SIRPα. Interestingly, SIRPα treated with N-glycosidase F was unable to bind Sp-D (supplemental Fig. S1A), whereas O-glycosidase treatment did not prevent Sp-D binding to SIRPα (supplemental Fig. S1A), implying that SIRPα binds to N-linked glycans of SIRPα.

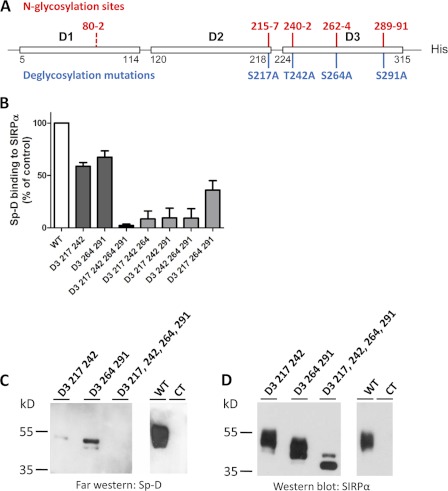

N-Linked Glycan at Position 240 in D3 Is Major Binding Site of Sp-D

To determine which N-glycosylation sites mediate Sp-D binding we analyzed SIRPα glycosylation using NetNGlyc software from ExPASy. From this analysis, one strong N-glycosylation sites is predicted to lie at the C-terminal domain of the D2 domain (position 215–217) and three in the D3 domain (positions 240–242, 262–264, 289–291) (Fig. 4A). We thus mutated predicted N-glycosylation sites (Asn-Xaa-Ser/Thr) by replacing the third amino acid by an alanine (S217A,T242A,S264A,S291A). Mutation of the four D3 N-glycosylation sites led to a major decrease of molecular mass as well as staining pattern consistent with loss of glycosylation (Fig. 4D), suggesting that SIRPα D3 domain is indeed the main glycosylated domain of SIRPα. SIRPα lacking all N-glycosylation sites present in D3, resulted in an absence of Sp-D binding (Fig. 4C), indicating that N-linked glycosylation of the SIRPα D3 domain is indeed critical in mediating binding interactions with Sp-D. However, it is possible that the absence of binding may be secondary to structural instability of SIRPα because the protein lacks main N-glycosylation sites. To rule out this possibility, we assessed whether the S217A,T242A,S264A,S291A mutant was still capable of binding CD47. Importantly, WT and mutant SIRPα were both observed to bind CD47 in a similar fashion, suggesting that the ligand binding structure of SIRPα is not impaired (data not shown). Furthermore, mutations in two D3 N-glycosylation sites promoted a significant decrease in Sp-D binding, which was confirmed by results of far Western blot analyses (Fig. 4, C and D). Thus, the mutagenesis results in this report suggest that binding of Sp-D to SIRPα D3 is mediated by contributions from all N-linked glycosylated residues in that domain.

FIGURE 4.

Sp-D binds to N-glycosylated sites on the SIRPα D3 domain. A, map of SIRPα N-glycosylation-sites as determined by the NetNGlyc 1.0 server from the Center of Biological Sequence Analysis. Strong putative N-glycosylation sites are indicated in red, whereas weak sites are in dashed red. B, in vitro binding assay of various mutants lacking one or several N-glycosylated sites in the SIRPα D3 domain as performed as in Fig. 1B. C, far Western blot analysis of various N-glycosylated site mutants. Purified N-glycosylated site mutants were separated by SDS-PAGE, and Sp-D binding was assessed as in Fig. 1C. An unrelated protein (JAM-L) was used as a negative control (CT). D, PVDF membrane from Fig. C stripped and blotted for SIRPα (SAF17.2) as for Fig. 1D. Results are representative of one of two independent experiments. Error bars, S.E.

To further examine the role of the above N-glycosylation sites in Sp-D binding, we mutated three of the four D3 N-glycosylation sites leaving only one intact (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, binding studies with these mutants suggest that all N-glycosylation sites on SIRPα D3 partially mediate Sp-D binding (Fig. 4B). However, the N-glycan linked to the Asn-240 site showed higher affinity for Sp-D than other sites because Sp-D binding to D3 mutants 217, 264, and 291 containing only the Asn-240 site was highest (Fig. 4B). This suggests that glycan linked to the 240 N-glycosylation site is the major Sp-D binding site.

Sp-D Binds to SIRPα Expressed in Cells

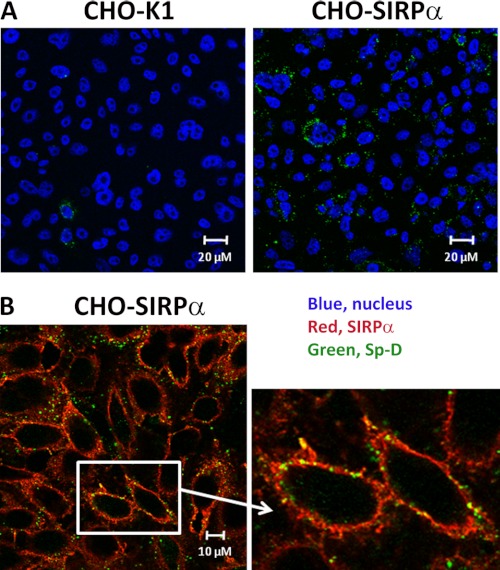

Because we observed that Sp-D bound purified soluble extracellular SIRPα domains in cell-free systems, we sought to verify that Sp-D was also able to bind SIRPα expressed on the eukaryotic cell surface. We first used CHO cells stably expressing functional human SIRPα (CHO-SIRPα). We examined whether CHO-SIRPα was able to bind Sp-D. As can be seen in Fig. 5A, we observed low levels of Sp-D binding to untransfected CHO-K1. However, Sp-D binding was significantly increased after SIRPα was expressed on the surface of CHO cells (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, incubation of CHO cells expressing SIRPα with Sp-D demonstrated co-localization of Sp-D with SIRPα (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Sp-D binds to CHO-K1 cells stably expressing SIRPα. A, CHO-K1 and CHO-SIRPα-expressing cells were incubated with Sp-D, and Sp-D binding was assessed by immunofluorescence using antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (green). Nuclei were stained with To-Pro3 after permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 (blue). B, co-localization of Sp-D and SIRPα on CHO-SIRPα was determined by immunofluorescence using anti-rabbit conjugated to Alexa Fluor 555 (red, SIRPα) and anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (green, Sp-D). Results are representative of one of four independent experiments.

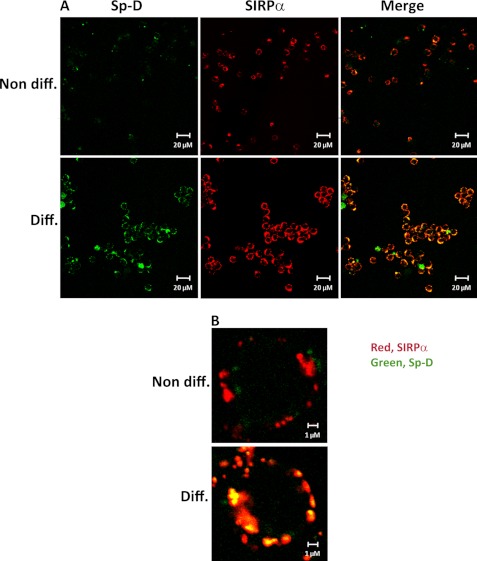

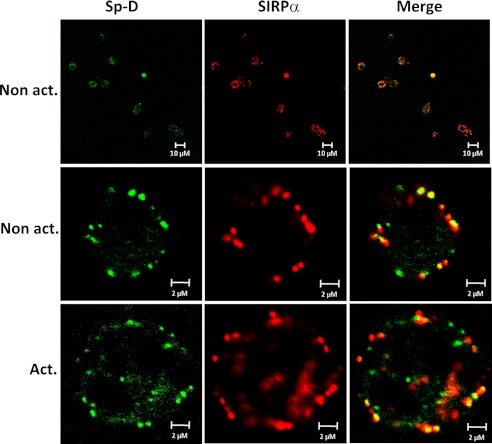

In other reports, surfactant protein Sp-D has been shown to bind to macrophage-expressed SIRPα and repress cytokine production (24, 25). However, little is known about Sp-D binding to neutrophils, which represent the first line of defense against pathogen invasion. Thus, we assessed Sp-D binding to human promyelocytic leukemia cells differentiated to neutrophil-like cells by dimethyl sulfoxide. We first examined SIRPα expression by these cells by flow cytometry. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, SIRPα expression was much higher in differentiated cells than in nondifferentiated cells. This observation was confirmed by immunofluorescence showing than SIRPα staining was much higher in differentiated cells than observed in nondifferentiated cells (Fig. 6). Accordingly, Sp-D binding to differentiated cells was significantly higher than observed in nondifferentiated cells, which directly correlated with increased SIRPα expression (Fig. 6). We also confirmed that Sp-D binding to cellular SIRPα is calcium-dependent and carbohydrate-specific (supplemental Fig. S3). Co-localization of Sp-D binding with SIRPα was observed on differentiated cells, whereas Sp-D and SIRPα did not co-localize as well in nondifferentiated cells (Fig. 6B). Extending these findings to natural human cells, we observed that Sp-D and SIRPα binding co-localized on nonactivated and activated human PMNs (Fig. 7). These findings are consistent with Sp-D binding to SIRPα on the cell surface of PMNs.

FIGURE 6.

Sp-D binding co-localizes with SIRPα expression on neutrophil-like cells. Two cell lines tested in this study, HL60 and PLB985, exhibited similar results (PLB985 staining results shown). Cells were stained as indicated in Fig. 5A. A, Sp-D binding is significantly increased on differentiated neutrophil-like cells versus nondifferentiated cells. B, Sp-D and SIRPα binding co-localize on neutrophil-like cells. Neutrophil-like cells were stained as in Fig. 5B. Results are representative of one of four independent experiments.

FIGURE 7.

Sp-D and SIRPα co-localize on human PMNs. Isolated human neutrophils (nonactivated and activated) were incubated with Sp-D and further stained for Sp-D and SIRPα as indicated in Fig. 5A. Results are representative of one of three independent experiments.

Sp-D Binds to SIRPβ D3

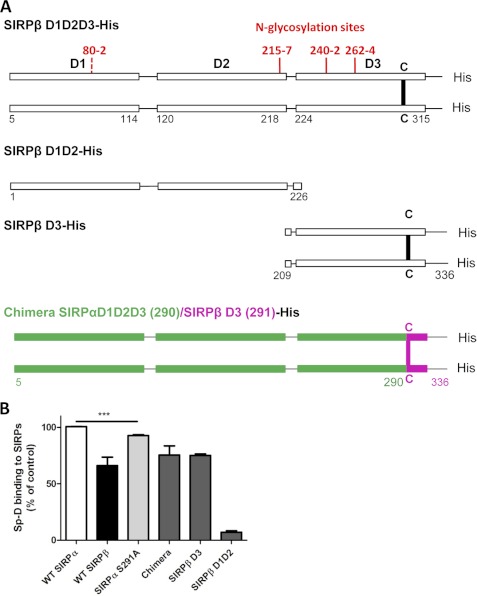

Another closely related member of the SIRP family, SIRPβ, is expressed as a covalent dimer on the cell surface with an ectodomain that is highly similar to SIRPα, yet it does not bind CD47, and the ligand(s) are unknown. Given that the D3 domains of SIRPα and SIRPβ share 93.7% homology (2), we hypothesized that Sp-D may also bind to SIRPβ, specifically to the D3 domain. To assess this possibility, we purified SIRPβ D1D2D3-His (Fig. 8A) and performed an in vitro binding assay. As shown in Fig. 8B, Sp-D bound to SIRPβ with only slightly less affinity than observed to SIRPα. Specificity of Sp-D binding to SIRPβ was confirmed by far Western blotting (data not shown). Furthermore, Sp-D binding to SIRPβ was confirmed to be calcium-dependent, sugar-specific, and inhibited by LPS (supplemental Fig. S4 and Fig. 3C). As shown in Fig. 8B, Sp-D bound to SIRPβ D3 and not to D1D2 domains, indicating that D3 is indeed the domain responsible for Sp-D binding to SIRPβ and confirming results obtained with SIRPα.

FIGURE 8.

Sp-D binds to SIRPβ D3 domain. A, map of SIRPβ mutants used in this study. Strong predicted N-glycosylation sites are indicated in plain red, whereas dashed red represents weak N-glycosylation sites according to the NetNGlyc 1.0 server from the Center of Biological Sequence Analysis. B, in vitro binding assay of Sp-D to various SIRPβ mutants as described in Fig. 1B. ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E.

We observed that Sp-D binding to SIRPβ is slightly lower than that to SIRPα (∼70% of SIRPα binding) (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, a significant difference between SIRPα and SIRPβ is in the specific, covalent dimerization of SIRPβ at a cysteine residue at position 290 (Fig. 8A). This residue lies at the same position of an N-glycosylation sequence present in SIRPα, indicating that a N-glycosylation site (Asn-289) on SIRPα is missing in SIRPβ. However, the other glycosylation sites at 215, 240, and 262 of SIRPβ are identical to those in SIRPα (data not shown). We thus investigated whether this missing N-glycosylation site could account for the difference in binding of Sp-D to SIRPβ compared with that observed with SIRPα. We generated a chimeric protein composed of D1D2 and part of D3 domain (1–291) from SIRPα fused with the N-terminal D3 domain of SIRPβ (292–336), including the disulfide bond at 290 necessary for dimerization (Fig. 8A). This chimeric protein thus contains the three first N-glycosylation sites of SIRPα in addition to the cysteine-mediated covalent bridge in SIRPβ. Sp-D bound similarly to the chimeric protein and WT SIRPβ, suggesting that the three first N-glycosylation sites of SIRPβ (215, 240, and 262) are not responsible for the decrease in Sp-D binding to SIRPβ compared with SIRPα (Fig. 8B). We next investigated whether the lack of a glycosylation site at 289 resulted in decreased Sp-D binding to SIRPβ. To explore this possibility, we generated a SIRPα mutant (S291A) that lacks glycosylation at that site, but contains the other three sites in D3. As can be seen in Fig. 8B, removal of the 289 N-glycosylation site of SIRPα resulted in a slight but very significant reduction of Sp-D binding to SIRPα, suggesting that this N-glycosylation site is an important site for Sp-D binding. Taken together, our results suggest that Sp-D binding to SIRPβ is D3 domain-dependent and that N-glycosylation at position 289 is required for Sp-D binding to SIRPα.

DISCUSSION

Neutrophils are the first immune cells to be recruited to a site of inflammation/infection and thus are one of the first lines of defense against pathogens. Among the proteins expressed at the surface of PMNs, SIRPα has been shown to regulate neutrophil migration, but also appears to be involved in other innate immune functions such as phagocytosis and cytokine production (7, 34, 40–42). Similarly, Sp-D secreted by specialized cells mainly in the lung, enhances the action of scavenger cells by opsonization (17). Interestingly, Sp-D has also been shown to be chemotactic for neutrophils (43, 44), suggesting a role in regulation of neutrophil migration. Others have reported that Sp-D is capable of binding SIRPα, leading to decrease of cytokine production by macrophages through the activation of SHP-1 and blockade of p38 (24). However, little is known about the interaction of SIRPα and Sp-D in neutrophils, and even less is known regarding the molecular basis of Sp-D binding to SIRPα. Given the potential importance of Sp-d-SIRPα binding interactions in regulating innate immune function, we performed extensive mutagenesis experiments to define the region(s) on SIRPα that bind to Sp-D. In experiments using domain deletion of SIRPα we determined that D3 of SIRPα exclusively mediates Sp-D binding. In concert with ours and other previous analyses indicating that CD47 binds exclusively to SIRPα D1 domain (9–12), the current results raise interesting possibilities regarding SIRPα function. Specifically, these data suggest that CD47 and Sp-D can bind SIRPα simultaneously. Indeed, CD47 binding to SIRPα does not prevent Sp-D binding and vice versa (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, Sp-D and CD47 have very different binding properties where CD47 detects a protein epitope on the immunoglobulin-variable D1 domain (2) and Sp-D binds to N-linked carbohydrates on the D3 domain. Further studies are needed to assess more precisely the binding affinity of Sp-D to SIRPα. However, from these results, we can now speculate that such distinct binding interactions might indicate differences in SIRPα function.

Sp-D belongs to the collectin family of collagen tail-containing lectins known to recognize carbohydrates at the surface of pathogens and to increase pathogen uptake by at least two distinct mechanisms, i.e. direct binding to pathogens, leading to enhanced uptake by scavenger cells and binding to surface receptors involved in immunity, resulting in the modulation of the receptor function (14, 45). Indeed, Sp-D has been reported to bind CD14 in a calcium- and carbohydrate-dependent manner (35). Sp-D is also capable of binding to soluble TLR2 and TLR4, pattern recognition receptors involved in pathogen recognition (46). However, the exact function of Sp-D binding to these receptors remains quite unclear. Interestingly, interaction of Sp-D with CD14 decreases CD14 binding to LPS (35). We similarly found that Sp-D binding to SIRPα is impaired in the presence of LPS (Fig. 3C). This observation is consistent with a previous report showing that Sp-D binds to macrophage SIRPα in the absence of pathogens, leading to activation of SIRPα, decreased cytokine production, and inhibition of inflammation. In contrast, when pathogens are present, it was shown that Sp-D CRD binds preferably to LPS or other bacterial carbohydrates. It was suggested that, under such conditions, the absence of ligand binding to SIRPα would release ITIM-mediated signals resulting in increased inflammation (24). However, this study did not take into account the role of CD47 in modulation of SIRPα function as it was proposed that CD47 and Sp-D exclusively bind SIRPα. Because our study demonstrates that SIRPα is capable of binding both proteins together, it is clear that regulation of SIRPα is more complex and dependent on both Sp-D and CD47, especially because CD47 is expressed on the surface of all nontransformed cells.

We also report that SIRPβ, a protein closely related to SIRPα, also binds Sp-D, and this adds new insights into the potential role of SIRPβ in innate immunity. In human monocytic cell lines as well as in peritoneal macrophages, SIRPβ has been reported to function through interactions with DAP12, an ITAM-containing adaptor protein (26, 27). However, no ligand has been identified so far, and to our knowledge, this is the first time that a binding partner for SIRPβ is described. We previously reported that SIRPβ is a covalently linked homodimer (47). Interestingly, recent studies from our group also indicate that SIRPα is a noncovalently linked cis-homodimer on the PMN cell surface, and dimerization is enhanced by activation with bacterial products (2). Although the mechanism(s) leading to dimerization in SIRPα are not clear, we previously found that dimerization was dependent on N-glycosylation most likely by promoting a conformation that favors dimerization (2). Intriguingly, the binding of Sp-D to SIRPα S291A lacking a 289 N-glycosylation site is still higher than that to SIRPβ, suggesting that another parameter participates to the difference of binding between SIRPα and SIRPβ besides the 289 N-glycosylation site. Furthermore, the LPS concentration necessary to inhibit 50% of Sp-D binding to SIRPβ was 2-fold lower than that of SIRPα. Thus, the data from this study imply that Sp-D has higher affinity for monomeric SIRPs (SIRPα, S291A SIRPα) than for SIRP dimers (SIRPβ, chimera) (supplemental Fig. S5). We speculate that both SIRPα and SIRPβ may form different populations of dimers because one depends on covalent interactions and the other is dependent on glycosylation. Accessibility of ligands to N-glycosylation sites may therefore be different between these two SIRPs. Sp-D is known to form oligomers, and the multimeric state of Sp-D may therefore modulate its binding to SIRPα. Further studies will be necessary to assess the influence of SP-D multimerization on SIRPα binding. Taken together, these data suggest that the conformational as well as the glycosylation states of SIRPs are likely crucial parameters of Sp-D affinity.

In summary, we show that Sp-D binds to the D3 domain of both SIRPα and SIRPβ in a calcium-dependent and sugar-specific manner. Furthermore, we report that Sp-D binds to the membrane-proximal domain (D3) of SIRPα as well as to D3 of SIRPβ. Thus, Sp-D represents the first described ligand for SIRPβ. These studies reveal the specific N-glycosylation sites bound by Sp-D and highlight residue at position 240 as a major Sp-D binding determinant on SIRPα.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK079392 and DK072564 (to C. A. P.). This work was also supported by a Senior Research Award from the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America sponsored by the Rodenberry Foundation (to B. F.) and by core facilities (confocal microscopy, molecular cloning, and cell culture) funded by a National Institutes of Health sponsored Digestive Diseases Research Development Center Grant R24 DK064399.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5.

- SIRP

- signal regulatory protein

- ABTS

- 2,2′-azinobis[3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid]-diammonium salt

- CRD

- carbohydrate recognition domain

- HEK293T

- human embryonic kidney cell line with T antigen

- PMN

- polymorphonuclear leukocyte (neutrophil)

- Sp-D

- surfactant protein D.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adams S., van der Laan L. J., Vernon-Wilson E., Renardel de Lavalette C., Döpp E. A., Dijkstra C. D., Simmons D. L., van den Berg T. K. (1998) Signal-regulatory protein is selectively expressed by myeloid and neuronal cells. J. Immunol. 161, 1853–1859 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee W. Y., Weber D. A., Laur O., Stowell S. R., McCall I., Andargachew R., Cummings R. D., Parkos C. A. (2010) The role of cis dimerization of signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) in binding to CD47. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 37953–37963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Veillette A., Thibaudeau E., Latour S. (1998) High expression of inhibitory receptor SHPS-1 and its association with protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 22719–22728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kharitonenkov A., Chen Z., Sures I., Wang H., Schilling J., Ullrich A. (1997) A family of proteins that inhibit signalling through tyrosine kinase receptors. Nature 386, 181–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fujioka Y., Matozaki T., Noguchi T., Iwamatsu A., Yamao T., Takahashi N., Tsuda M., Takada T., Kasuga M. (1996) A novel membrane glycoprotein, SHPS-1, that binds the SH2-domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 in response to mitogens and cell adhesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6887–6899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Okazawa H., Motegi S., Ohyama N., Ohnishi H., Tomizawa T., Kaneko Y., Oldenborg P. A., Ishikawa O., Matozaki T. (2005) Negative regulation of phagocytosis in macrophages by the CD47-SHPS-1 system. J. Immunol. 174, 2004–2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith R. E., Patel V., Seatter S. D., Deehan M. R., Brown M. H., Brooke G. P., Goodridge H. S., Howard C. J., Rigley K. P., Harnett W., Harnett M. M. (2003) A novel MyD-1 (SIRP-1α) signaling pathway that inhibits LPS-induced TNFα production by monocytes. Blood 102, 2532–2540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yamao T., Noguchi T., Takeuchi O., Nishiyama U., Morita H., Hagiwara T., Akahori H., Kato T., Inagaki K., Okazawa H., Hayashi Y., Matozaki T., Takeda K., Akira S., Kasuga M. (2002) Negative regulation of platelet clearance and of the macrophage phagocytic response by the transmembrane glycoprotein SHPS-1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39833–39839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee W. Y., Weber D. A., Laur O., Severson E. A., McCall I., Jen R. P., Chin A. C., Wu T., Gernet K. M., Parkos C. A. (2007) Novel structural determinants on SIRPα that mediate binding to CD47. J. Immunol. 179, 7741–7750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hatherley D., Graham S. C., Turner J., Harlos K., Stuart D. I., Barclay A. N. (2008) Paired receptor specificity explained by structures of signal regulatory proteins alone and complexed with CD47. Mol. Cell 31, 266–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seiffert M., Brossart P., Cant C., Cella M., Colonna M., Brugger W., Kanz L., Ullrich A., Bühring H. J. (2001) Signal-regulatory protein α (SIRPα) but not SIRPβ is involved in T-cell activation, binds to CD47 with high affinity, and is expressed on immature CD34+CD38− hematopoietic cells. Blood 97, 2741–2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vernon-Wilson E. F., Kee W. J., Willis A. C., Barclay A. N., Simmons D. L., Brown M. H. (2000) CD47 is a ligand for rat macrophage membrane signal regulatory protein SIRP (OX41) and human SIRPα1. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 2130–2137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oldenborg P. A., Zheleznyak A., Fang Y. F., Lagenaur C. F., Gresham H. D., Lindberg F. P. (2000) Role of CD47 as a marker of self on red blood cells. Science 288, 2051–2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wright J. R. (2005) Immunoregulatory functions of surfactant proteins. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 58–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haagsman H. P., Hawgood S., Sargeant T., Buckley D., White R. T., Drickamer K., Benson B. J. (1987) The major lung surfactant protein, SP 28–36, is a calcium-dependent, carbohydrate-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 13877–13880 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Persson A., Chang D., Crouch E. (1990) Surfactant protein D is a divalent cation-dependent carbohydrate-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 5755–5760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crouch E., Wright J. R. (2001) Surfactant proteins A and D and pulmonary host defense. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 63, 521–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crouch E. C. (2000) Surfactant protein D and pulmonary host defense. Respir. Res. 1, 93–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lim B. L., Wang J. Y., Holmskov U., Hoppe H. J., Reid K. B. (1994) Expression of the carbohydrate recognition domain of lung surfactant protein D and demonstration of its binding to lipopolysaccharides of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 202, 1674–1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akiyama J., Hoffman A., Brown C., Allen L., Edmondson J., Poulain F., Hawgood S. (2002) Tissue distribution of surfactant proteins A and D in the mouse. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 50, 993–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin Z., Floros J. (2002) Heterogeneous allele expression of pulmonary SP-D gene in rat large intestine and other tissues. Physiol. Genomics 11, 235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Madsen J., Kliem A., Tornoe I., Skjodt K., Koch C., Holmskov U. (2000) Localization of lung surfactant protein D on mucosal surfaces in human tissues. J. Immunol. 164, 5866–5870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Soerensen C. M., Nielsen O. L., Willis A., Heegaard P. M., Holmskov U. (2005) Purification, characterization, and immunolocalization of porcine surfactant protein D. Immunology 114, 72–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gardai S. J., Xiao Y. Q., Dickinson M., Nick J. A., Voelker D. R., Greene K. E., Henson P. M. (2003) By binding SIRPα or calreticulin/CD91, lung collectins act as dual function surveillance molecules to suppress or enhance inflammation. Cell 115, 13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Janssen W. J., McPhillips K. A., Dickinson M. G., Linderman D. J., Morimoto K., Xiao Y. Q., Oldham K. M., Vandivier R. W., Henson P. M., Gardai S. J. (2008) Surfactant proteins A and D suppress alveolar macrophage phagocytosis via interaction with SIRPα. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 178, 158–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dietrich J., Cella M., Seiffert M., Bühring H. J., Colonna M. (2000) Cutting edge: signal-regulatory protein β1 is a DAP12-associated activating receptor expressed in myeloid cells. J. Immunol. 164, 9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hayashi A., Ohnishi H., Okazawa H., Nakazawa S., Ikeda H., Motegi S., Aoki N., Kimura S., Mikuni M., Matozaki T. (2004) Positive regulation of phagocytosis by SIRPβ and its signaling mechanism in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29450–29460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McVicar D. W., Taylor L. S., Gosselin P., Willette-Brown J., Mikhael A. I., Geahlen R. L., Nakamura M. C., Linnemeyer P., Seaman W. E., Anderson S. K., Ortaldo J. R., Mason L. H. (1998) DAP12-mediated signal transduction in natural killer cells: a dominant role for the Syk protein-tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32934–32942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Drexler H. G., Quentmeier H., MacLeod R. A., Uphoff C. C., Hu Z. B. (1995) Leukemia cell lines: in vitro models for the study of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Leuk. Res. 19, 681–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tucker K. A., Lilly M. B., Heck L., Jr., Rado T. A. (1987) Characterization of a new human diploid myeloid leukemia cell line (PLB-985) with granulocytic and monocytic differentiating capacity. Blood 70, 372–378 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Collins S. J., Ruscetti F. W., Gallagher R. E., Gallo R. C. (1978) Terminal differentiation of human promyelocytic leukemia cells induced by dimethyl sulfoxide and other polar compounds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75, 2458–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ho S. N., Hunt H. D., Horton R. M., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. (1989) Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boussif O., Lezoualc'h F., Zanta M. A., Mergny M. D., Scherman D., Demeneix B., Behr J. P. (1995) A versatile vector for gene and oligonucleotide transfer into cells in culture and in vivo: polyethylenimine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7297–7301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu Y., Bühring H. J., Zen K., Burst S. L., Schnell F. J., Williams I. R., Parkos C. A. (2002) Signal regulatory protein (SIRPα), a cellular ligand for CD47, regulates neutrophil transmigration. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10028–10036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sano H., Chiba H., Iwaki D., Sohma H., Voelker D. R., Kuroki Y. (2000) Surfactant proteins A and D bind CD14 by different mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22442–22451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mackarel A. J., Russell K. J., Ryan C. M., Hislip S. J., Rendall J. C., FitzGerald M. X., O'Connor C. M. (2001) CD18 dependency of transendothelial neutrophil migration differs during acute pulmonary inflammation. J. Immunol. 167, 2839–2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kuan S. F., Rust K., Crouch E. (1992) Interactions of surfactant protein D with bacterial lipopolysaccharides: surfactant protein D is an Escherichia coli-binding protein in bronchoalveolar lavage. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raetz C. R. (1990) Biochemistry of endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59, 129–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Khamri W., Moran A. P., Worku M. L., Karim Q. N., Walker M. M., Annuk H., Ferris J. A., Appelmelk B. J., Eggleton P., Reid K. B., Thursz M. R. (2005) Variations in Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide to evade the innate immune component surfactant protein D. Infect. Immun. 73, 7677–7686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gardai S. J., McPhillips K. A., Frasch S. C., Janssen W. J., Starefeldt A., Murphy-Ullrich J. E., Bratton D. L., Oldenborg P. A., Michalak M., Henson P. M. (2005) Cell-surface calreticulin initiates clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of LRP on the phagocyte. Cell 123, 321–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ishikawa-Sekigami T., Kaneko Y., Okazawa H., Tomizawa T., Okajo J., Saito Y., Okuzawa C., Sugawara-Yokoo M., Nishiyama U., Ohnishi H., Matozaki T., Nojima Y. (2006) SHPS-1 promotes the survival of circulating erythrocytes through inhibition of phagocytosis by splenic macrophages. Blood 107, 341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oldenborg P. A., Gresham H. D., Lindberg F. P. (2001) CD47-signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) regulates Fcγ and complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J. Exp. Med. 193, 855–862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cai G. Z., Griffin G. L., Senior R. M., Longmore W. J., Moxley M. A. (1999) Recombinant SP-D carbohydrate recognition domain is a chemoattractant for human neutrophils. Am. J. Physiol. 276, L131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hartshorn K. L., Crouch E., White M. R., Colamussi M. L., Kakkanatt A., Tauber B., Shepherd V., Sastry K. N. (1998) Pulmonary surfactant proteins A and D enhance neutrophil uptake of bacteria. Am. J. Physiol. 274, L958–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haczku A. (2008) Protective role of the lung collectins surfactant protein A and surfactant protein D in airway inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 122, 861–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ohya M., Nishitani C., Sano H., Yamada C., Mitsuzawa H., Shimizu T., Saito T., Smith K., Crouch E., Kuroki Y. (2006) Human pulmonary surfactant protein D binds the extracellular domains of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 through the carbohydrate recognition domain by a mechanism different from its binding to phosphatidylinositol and lipopolysaccharide. Biochemistry 45, 8657–8664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu Y., Soto I., Tong Q., Chin A., Bühring H. J., Wu T., Zen K., Parkos C. A. (2005) SIRPβ1 is expressed as a disulfide-linked homodimer in leukocytes and positively regulates neutrophil transepithelial migration. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 36132–36140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hatherley D., Graham S. C., Harlos K., Stuart D. I., Barclay A. N. (2009) Structure of signal-regulatory protein α: a link to antigen receptor evolution. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26613–26619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.