Background: Bv8 expression is strongly induced by G-CSF, but the mechanisms of this induction remain unknown.

Results: Stat3 activation is required for G-CSF induced Bv8 up-regulation.

Conclusion: Stat3 plays a key role in regulating G-CSF induced Bv8 expression.

Significance: Elucidating the signaling pathways implicated in Bv8 regulation is crucial to understand the role of this molecule in pathophysiological circumstances.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Chemokines, Stromal cell, Tumor Microenvironment, Vascular Biology, Bv8, G-CSF, Myeloid Cell, Prokineticin, Stat3

Abstract

Bv8, also known as prokineticin 2, has been characterized as an important mediator of myeloid cell mobilization and myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis. Bv8 expression is dramatically enhanced by G-CSF, both in vitro and in vivo. The mechanisms involved in such up-regulation remain unknown. Using pharmacological inhibitors that interfere with multiple signaling pathways known to be activated by G-CSF, we show that signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) activation is required for Bv8 up-regulation in mouse bone marrow cells, whereas other Stat family members and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation are not involved. We further identified CD11b+ Gr1+ myeloid cells as the primary cell population in which Stat3 signaling is activated by G-CSF. Bv8 expression induced by G-CSF was also significantly reduced by siRNA-mediated Stat3 knockdown. Moreover, chromatin immunoprecipitation studies indicate that G-CSF significantly induces binding of phospho-Stat3 to the Bv8 promoter, which was abolished by pretreatment with the Stat3 inhibitor WP1066. Luciferase assay confirmed that the phospho-Stat3 binding site is a functional enhancer of the Bv8 promoter. The key role of Stat3 signaling in regulating G-CSF-induced Bv8 expression was further confirmed by in vivo studies. We show that the regulation of Bv8 expression in human bone marrow cells is also Stat3 signaling-dependent. Stat3 is recognized as a key regulator of inflammation-dependent tumorigenesis. We propose that such a role of Stat3 reflects at least in part its ability to regulate Bv8 expression.

Introduction

Endocrine gland-derived VEGF (EG-VEGF)2 and Bv8, known also as prokineticin-1 and -2, respectively, are two related secreted proteins that belong to a larger class of peptides defined by a five-disulfide bridge motif called a colipase fold (1–3). Bv8 and EG-VEGF bind two highly related G-protein-coupled receptors, PKR1 and PKR2 (4, 5). Bv8 was initially identified from the skin of the frog Bombina variegata based on the ability to induce hyperalgesia and gastrointestinal motility (3). Later on, this highly conserved protein was also shown to regulate neuronal survival (6) and circadian rhythms (7).

Bv8 and EG-VEGF have been shown to promote tissue-specific angiogenesis and hematopoietic cell mobilization (2, 8, 9). Unlike EG-VEGF, Bv8 is mainly expressed by peripheral blood and bone marrow cells (8). Recently, Bv8 has been shown to be up-regulated in inflammatory granulocytes and to modulate inflammation-associated pain (10). Bv8 expression is up-regulated in CD11b+ Gr1+ cells after implantation of tumor cells (11). Analysis of several xenografts (11) as well as of a transgenic cancer model (12) suggested that Bv8 promotes tumor angiogenesis through increased peripheral mobilization of CD11b+ Gr1+ cells from the bone marrows and local stimulation of angiogenesis. Our earlier studies identified granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) as a strong inducer of Bv8 expression in vitro and in vivo (11). G-CSF is a principle regulator of granulopoiesis and neutrophil mobilization from the bone marrow (13) and is widely used in cancer therapy to reduce chemotherapy-associated neutropenia (14). However, some recent observations suggest that G-CSF can facilitate tumor angiogenesis (15–17) and also plays a role in the development of refractoriness to anti-VEGF agents (18). Thus, G-CSF and Bv8 may represent new therapeutic targets. Elucidation of the signal transduction events involved in Bv8 regulation should enhance our understanding of the role of this molecule in tumorigenesis.

Stat 3, a member of the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family of proteins, has been recently implicated as a major regulator of inflammation-associated tumorigenesis (19–22). In the present study, we report that Stat3 signaling plays an essential role in Bv8 regulation by G-CSF, both in mouse and in human bone marrow cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Fludarabine (Stat1 inhibitor) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). GDC-0973/XL518 (MEK1/2 inhibitor) was from Genentech (South San Francisco, CA). WP1066 (Stat3 inhibitor), N′-((4-oxo-4H-chromen-chromen-3-yl) methylene) nicotinohydrazide (Stat5 inhibitor), and PD98059 (MEK1/2 inhibitor) were from Calbiochem (EMD Millipore). Recombinant mouse IL6, IL10, G-CSF, stem cell factor, Flt3 ligand, recombinant human G-CSF, and thrombopoietin were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Antibodies specific for phospho-Stat1(Tyr-701), phopho-Stat3(Tyr-705), phospho-Stat5(Tyr-694), phospho-p42/44 MAPK, total Stat3, total p42/44 MAPK, or β-actin were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA).

Isolation of Mouse Bone Marrow Cells

6–8-week-old BALB/c mice from Charles River Laboratories were maintained under the guidelines of the Genentech animal care facility. Bone marrow cells were flushed from femurs and tibias with DMEM containing 10% FBS. Cells were then washed and resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 0.2% BSA (Serologicals Corp., Atlanta, GA) for further studies.

In Vitro Studies

For in vitro inhibition studies, two million freshly isolated mouse bone marrow cells were preincubated with various inhibitors at several concentrations for 1 h, with the exception of fludarabine, which was preincubated for 4 h. Cells were then incubated with 10 ng/ml mouse G-CSF for additional 4 h. All inhibitors were dissolved in DMSO as a stock solution and serially diluted to the desired concentration with culture medium. The final concentration of DMSO in cell culture systems was 0.02%. Mouse Bv8 expression was analyzed by TaqMan (11). Data were normalized against RPL19 expression and cell viability was evaluated in parallel.

To investigate Stat3 phosphorylation in different cell populations following treatment with various cytokines, red blood cells were first lysed using ammonium chloride-potassium buffer (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) followed by staining with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse Gr1 and allophycocyanin-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD11b antibodies (Pharmingen). CD11b+ Gr1+ and CD11b− Gr1− subsets were then obtained using FACS. Stat3 activation in different subsets was assessed by Western blot. G-CSF receptor (G-CSFR) expression levels in different cell subsets were analyzed by TaqMan. The TaqMan primers and probes for G-CSFR were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), and the assay ID number is Mm00432735_m1.

siRNA Experiments

Freshly isolated bone marrow cells were cultured overnight in DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 100 ng/ml mouse stem cell factor, 100 ng/ml human thrombopoietin, and 100 ng/ml mouse Flt3 ligand. After two washes, four million cells were resuspended in 2 ml of Accell siRNA delivery medium (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) supplemented with 100 ng/ml mouse stem cell factor, 100 ng/ml human thrombopoietin, and 100 ng/ml mouse Flt3 ligand. Cells were then incubated for 48 h with 0.5 μm Accell SMARTpool of siRNA targeting mouse Stat3 (a mixture of the four different Stat3 on-target siRNA oligonucleotides: CCAGUAUGCUUGUCGGUUG,UCAAUGUUCUUUAGUUAUA, GGCUGAUCAUCUAUAUAAA, and CUGGAAAACUGGAUAACUU) or mouse Stat5 (a mixture of the four different Stat5 on-target siRNA oligonucleotides: GAUUCAUCCUUCUUGCUUU, CGUGGAAGAACUUUUACGC, UGAACUACCUUAUCUACGU, and UUGUGGUCUCAGAAAUCGC). Accell Green nontargeting siRNA (Dharmacon) was used as a negative control. Equivalent numbers of cells from each transfection were incubated with 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse G-CSF or with PBS for 4 h. Bv8 expression was assessed by TaqMan. The knockdown levels of Stat3 and Stat5 were analyzed by Western blot and quantified by densitometry.

5′ Rapid Amplification of cDNA End (5′-RACE)

To identify the transcription start site of mouse Bv8, mRNA was purified from total RNA from mouse bone marrow cells using the NucleoTrap mRNA mini kit (Clontech). cDNA was generated, and 5′-RACE PCR was performed using the SMARTerTM RACE cDNA amplification kit (Clontech). The sequence of the Bv8 specific primer used for 5′-RACE is: 5′-GCAGCGGTAGCAGCAGAAGTAGCAG-3′. The resulting PCR product was then cloned, sequenced, and mapped to mouse Bv8 genomic sequence.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Bone marrow cells (4 × 106 cells in 1× Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 0.2% BSA) were incubated with 10 ng/ml mouse G-CSF or PBS for 30 min. ChIP was then performed using the SimpleChIPTM enzymatic chromatin immunoprecipitation kit (Magnetic Beads) from Cell Signaling according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Following pulldown using 10 μl of anti-phospho-Stat3 antibody or control rabbit IgG, Bv8 promoter fragments were quantified by quantitative real-time PCR using Bv8-specific primers from its promoter region. The forward primer is: 5′-TTCGTTGGCATGGAGACTGGAAAG-3′, and the reverse primer is: 5′-GAGTTCAAGAAGCATCCTGAGACC-3′. For pharmacological inhibition experiments, bone marrow cells were preincubated with 5 μm WP1066 or with the same volume of DMSO for 1 h followed by the addition of 10 ng/ml G-CSF for 30 min. the ChIP assay was then performed as mentioned above.

Bv8 Luciferase Reporter Assays

A fragment of the Bv8 promoter region, from −1762 to +90, containing ATG start codon and Stat3 interferon-sensitive response element (ISRE) binding site was obtained by amplification of mouse genomic DNA. The fragment was then cloned into pGL4.23(luc2/minP) luciferase vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to replace the minimal promoter of luc2 gene. To investigate whether the phospho-Stat3 ISRE binding site within this fragment is a functional enhancer, the consensus sequence of the ISRE binding site, GAAAGGAAACT, was mutated to TCCACCAGTCT or deleted using the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The sequences of mutagenic primers for introducing mutations are: forward, 5′-GGCATGGAGACTGTCCACCAGTCTGTC-3′, and reverse, 5′-GACAGACTGGTGGACAGTCTCCATGCC-3′. The sequences of primers for introducing deletions are: forward, 5′-GCCTTCGTTGGCATGGAGACTGCCGCCGAGACTTTCCACCAGTC-3′,and reverse, 5′-GACTGGTGGAAAGTCTCGGCGGCAGTCTCCATGCCAACGAAGGC-3′. The pGL4.23-Bv8 construct, containing wild type, mutated, or deleted ISRE binding site, was co-transfected into HEK293T cells with plasmid expressing mouse Stat3 ORF (GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD) or control vector. The pRL-TK Renilla reporter vector (Promega) was used for transfection control. The pGL4.23 vector was used as negative control. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed with the passive lysis buffer (Promega), and luminescence was measured using the Dual-Luciferase assay system (Promega). Luminescence (relative light units) was normalized to the Renilla luciferase expression from the pRL-TK Renilla luciferase reporter vector transfection control.

In Vivo Studies

Eight-week-old BALB/c mice (n = 5) were injected subcutaneously with 10 μg of human G-CSF (Neupogen, Amgen) in 100 μl of PBS, together with 10 or 20 mg/kg WP1066 in 100 μl of vehicle, which were administered intraperitoneally. All drugs were administered daily for three consecutive days. Control mice were given PBS and vehicle (mixture of 20 parts DMSO and 80 parts polyethylene glycol 300 (Sigma-Aldrich)). At the end of the study, bone marrow cells were isolated, and peripheral blood was collected for Bv8 expression analysis by TaqMan and/or ELISA (11).

Regulation of Bv8 Expression in Human Bone Marrow Cells

Freshly isolated bone marrow cells from five different healthy donors were obtained from AllCells (Emeryville, CA). Red blood cells were lysed by adding 4 volumes of 1× buffered ammonium chloride solution (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Cells were then washed and resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution medium containing 0.2% BSA. To investigate the role of Stat3 in regulating Bv8 expression, 2 million cells were pretreated with WP1066 at various concentrations for 1 h and then incubated with 10 ng/ml human G-CSF for additional 4 h. Human Bv8 expression was assessed by TaqMan as described previously (23).

RESULTS

Stat3, but Not Other Stat Family Members nor ERK, Is Required for G-CSF-mediated Bv8 Expression

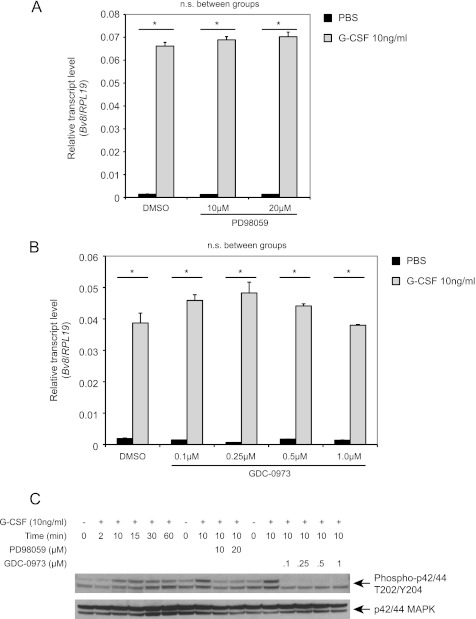

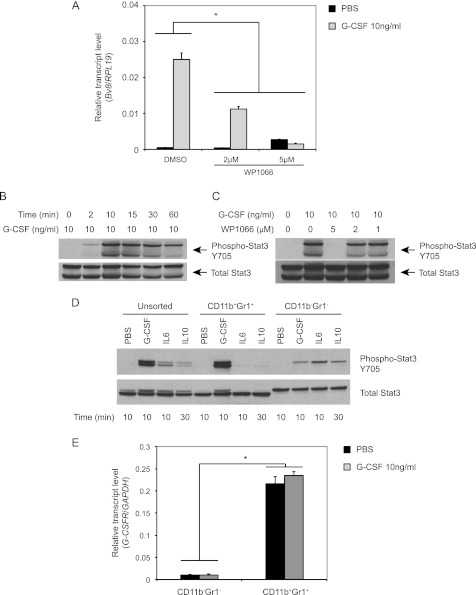

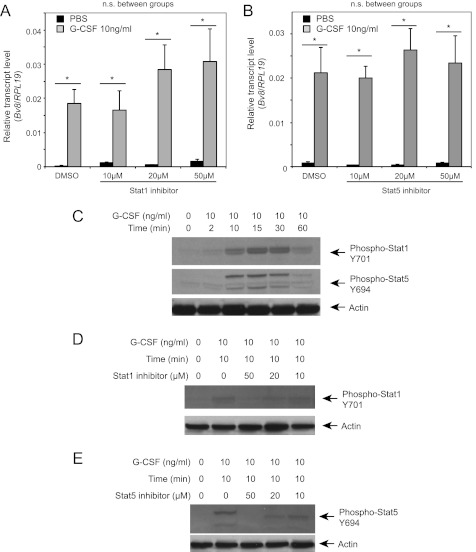

We previously identified G-CSF as a major positive regulator of Bv8 expression in vivo and in vitro (11). To elucidate the signal transduction pathways involved in such up-regulation, we pretreated the cells with various inhibitors of multiple G-CSF-activated signaling pathways, including the MEK/ERK and Jak-Stat pathways (24, 25). Pretreatment of bone marrow cells with the MEK1/2 inhibitors, PD98059 (Fig. 1A) or GDC-0973/XL518 (26, 27, 50) (Fig. 1B), had no effect on G-CSF-stimulated Bv8 expression at all concentrations tested. However, both inhibitors effectively suppressed G-CSF-induced ERK activation (Fig. 1C). Pretreatment with the Stat3 inhibitor WP1066, a cell-permeable AG490 tyrphostin analog, inhibited G-CSF-induced Bv8 expression in a dose-dependent manner with complete inhibition at 5 μm (see Fig. 3A). However, neither the Stat1 (Fig. 2A) nor the Stat5 inhibitor (Fig. 2B) had any significant effect. In contrast, both inhibitors (Fig. 2, D and E) completely inhibited G-CSF-induced Stat1 or Stat5 activation at 50 μm. None of the inhibitors had a significant effect on the viability of bone marrow cells at the concentrations tested (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

ERK is not involved in G-CSF-induced Bv8 up-regulation. A and B, Bv8 expression in bone marrow cells incubated with the MEK-1 inhibitor PD98059 (A) or GDC-0973 (B) was assessed by TaqMan. Error bars represent S.E. Asterisks indicate significant difference between G-CSF- and PBS-treated groups (p < 0.05). n.s., not significant. C, Western blot to detect phospho-p42/44 MAPK and total p42/44 MAPK after cells had been treated with G-CSF or after pretreatment with PD98059 or GDC-0973 for 1 h followed by G-CSF for an additional 10 min. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

FIGURE 3.

Stat3 activation is required for G-CSF induced Bv8 up-regulation. A, Bv8 expression in bone marrow cells. Error bars represent S.E. Asterisk indicates significant difference between WP1066 and control groups (p < 0.05). B–D, Western blot analysis to detect phospho-Stat3 after G-CSF treatment for the indicated time points (B), after treatment with 1, 2, or 5 μm WP1066 for 1 h followed by incubation with G-CSF for another 10 min (C), or in unsorted, CD11b+ Gr1+, and CD11b− Gr1− cells after treatment with G-CSF, IL6, and IL10 as indicated (D). E, G-CSFR expression in CD11b+ Gr1+ and CD11b− Gr1− cells after incubation with G-CSF or PBS for 4 h. Error bars represent S.E. Asterisk indicates significant difference in G-CSFR expression between the two cell subsets (p < 0.05). Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

FIGURE 2.

Stat1 and Stat5 are not involved in G-CSF induced Bv8 up-regulation. A and B, Bv8 expression analysis in bone marrow cells incubated with Stat1 (A) or Stat5 inhibitor (B). Error bars represent S.E. Asterisks indicate significant difference between G-CSF and PBS treated groups (p < 0.05). n.s., not significant. C, phospho-Stat1, phospho-Stat5, and β-actin levels after G-CSF treatment. D, phospho-Stat1 following pretreatment with Stat 1 inhibitor for 4 h. E, phospho-Stat5 after pretreatment with inhibitor for 1 h at the indicated concentrations followed by incubation with G-CSF for an additional 10 min. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Stat3 Activation in CD11b+ Gr1+ cells Is Required for G-CSF-mediated Bv8 Expression

To confirm that the Stat3 pathway can be activated by G-CSF in mouse bone marrow cells, we assessed Stat3 phosphorylation. We observed a rapid phosphorylation after the addition of G-CSF, starting at 2 min and peaking at 10 min. After 30 min, Stat3 phosphorylation decreased but was still above the nonstimulated background for at least 60 min (Fig. 3B). We further investigated the effects of WP1066 on G-CSF-activated Stat3 phosphorylation. Pretreatment with WP1066 blocked Stat3 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner, with complete inhibition at the concentration of 5 μm (Fig. 3C).

Stat3 is known to be activated by various cytokines including G-CSF, IL6, and IL10. However, previous studies indicated that among these cytokines, only G-CSF significantly up-regulates Bv8 expression (11). We hypothesized that Stat3-mediated Bv8 expression might be cell type-dependent. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed Stat3 phosphorylation in unsorted, CD11b+ Gr1+ cells and CD11b− Gr1− cells following treatment with IL6, IL10, or G-CSF at a maximal effective concentration 10 ng/ml. In unsorted bone marrow cells, all three factors were able to activate Stat3 signaling in a time-dependent manner. G-CSF activation of Stat3 was most prominent in CD11b+ Gr1+ cells, whereas IL6 or IL10 induced Stat3 phosphorylation mainly in CD11b− Gr1− cells (Fig. 3D). We further investigated whether the cell type-dependent G-CSF response may be due to the distinct expression of G-CSF receptor between these two cell populations. As shown in Fig. 3E, G-CSF receptor expression levels in CD11b+ Gr1+ cells were almost 20-fold higher than those measured in CD11b− Gr1− cells, regardless of whether the cells had been treated or not with G-CSF.

Because CD11b+ Gr1+ include granulocytic (CD11b+ Lys6G+) and monocytic (CD11b+ Ly6C+) cells, we sought to compare the G-CSF-induced Bv8 expression between these two subsets. As illustrated in supplemental Fig. 1, although G-CSF resulted in significant Bv8 up-regulation, the transcripts level in CD11b+ Ly6C+ cells were more than 2 orders of magnitude below the levels in CD11b+ Lys6G+ cells.

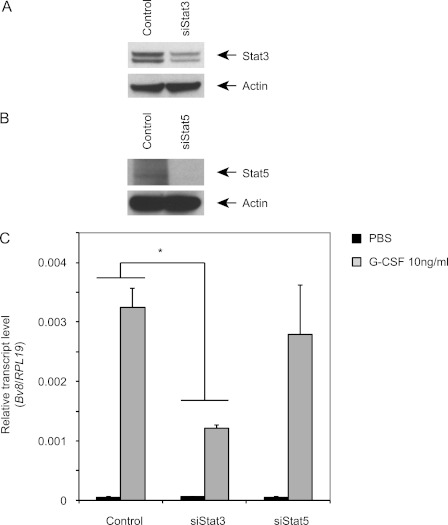

Stat3 siRNA Inhibits G-CSF-induced Bv8 Expression in Mouse Bone Marrow Cells

WP1066 has been shown to inhibit Stat3 activity and to have potent antitumor effects both in vitro and in vivo (28). However, this agent has been reported to inhibit also JAK-2 and Stat5 activities, at least in human glioma cells (28). To determine whether the observed effects of WP1066 are truly mediated by inhibition of Stat3 signaling, we knocked down Stat3 using Accell SMARTpool of siRNA for mouse Stat3. Densitometric analysis showed that siRNA-mediated Stat3 knockdown results in 51% decrease in Stat3 levels when compared with control siRNA treatment (Fig. 4A). In agreement with these findings, the knockdown resulted in more than 60% reduction in G-CSF-induced Bv8 expression (Fig. 4C). In contrast, although Stat5 siRNA almost completely knocked down Stat5 expression (Fig. 4B), the Bv8 expression levels remained similar to those in bone marrow cells treated with control siRNA(Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Stat3 siRNA inhibits G-CSF-induced Bv8 expression in bone marrow cells. Cells were transfected as indicated under “Experimental Procedures.” A and B, knockdown of Stat3 (A) or Stat5 (B) was assessed by Western blot. C, Bv8 expression was analyzed 48 h after siRNA transfection. Error bars represent S.E. Asterisk indicates significant difference between Stat3 siRNA and control siRNA treated groups (p < 0.05). Data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Bv8 Is a Direct Transcriptional Target of Stat3

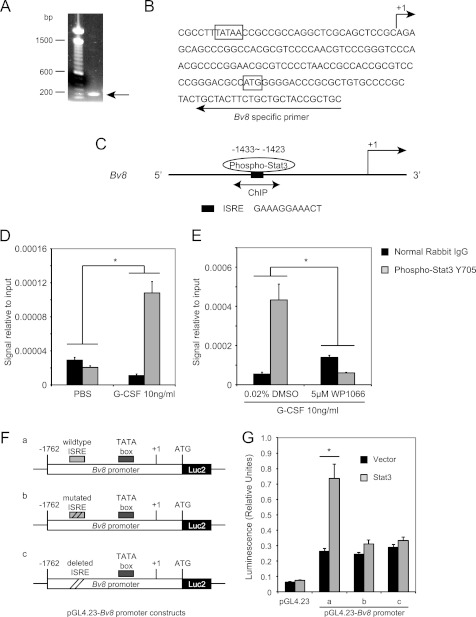

To determine whether Stat3-dependent Bv8 up-regulation occurs via direct binding to the Bv8 promoter region, we first performed 5′-RACE using mRNA from mouse bone marrow cells to identify the Bv8 transcription start site. A single band with an estimated size of 190 bp was obtained using Bv8-specific primers, which maps 25 nucleotides downstream of the ATG translational start codon, and the universal primer A mix provided in the SMARTerTM 5′-RACE kit (Fig. 5A). After the PCR product was cloned and sequenced, the transcription start site was mapped to 87 nucleotides upstream of the ATG translation start codon of mouse Bv8 (Fig. 5B), which was designated as the +1 position throughout this study. A typical TATA box was identified 25 bp upstream of the Bv8 transcription start site (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Bv8 is a direct transcriptional target of Stat3. A, agarose gel electrophoresis of the PCR product obtained from the 5′-RACE procedure. B, sequence of the mouse Bv8 gene around the translation start codon region. The arrow above the sequence indicates the transcription start site. The arrow below the sequence indicates the mouse Bv8-specific primer used for 5′-RACE. The translation start codon ATG and the TATA box are boxed. C, schematic diagram of Stat3 binding site within the proximal promoter region of the Bv8 gene. The bidirectional arrows mark the target regions for ChIP assays. D, G-CSF significantly induces the binding of phopho-Stat3 to the putative Stat3 binding site in the Bv8 promoter region. ChIPs were performed in bone marrow cells as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Error bars represent S.E. Asterisk indicates significant difference between G-CSF- and PBS-treated groups (p < 0.05). E, binding of phospho-Stat3 to the Bv8 promoter region following G-CSF treatment was blocked by pretreatment with 5 μm WP1066. Error bars represent S.E. Asterisk indicates significant difference between WP1066- and DMSO-treated groups (p < 0.05). The amount of immunoprecipitated DNA in each sample is represented as signal relative to the total amount of input chromatin, which is equivalent to one. F, schematic diagrams of the pGL4.23-Bv8 constructs, containing wild type ISRE (a), mutated ISRE (b), and deleted ISRE (c) binding site. G, Dual-Luciferase assay to investigate the role of phospho-Stat3 ISRE site in regulating mouse Bv8 promoter activity. Error bars represent S.E. Asterisk indicates significant difference between Stat3 ORF- and control vector-transfected groups (p < 0.05).

We then searched for putative Stat3 binding sites in the Bv8 promoter region. A typical Stat3 ISRE binding site was identified at −1433 to −1423 (Fig. 5C). To assess whether phospho-Stat3 could bind to this region, we performed ChIP experiments using a phospho-Stat3 antibody or rabbit IgG isotype control. As shown in Fig. 5D, binding of phospho-Stat3 to the identified site was significantly increased in G-CSF- but not in PBS-treated cells. Pretreatment of bone marrow cells with 5 μm WP1066 completely inhibited the G-CSF-induced binding of phospho-Stat3 to the Bv8 promoter region (Fig. 5E).

To further investigate the functional role of this phospho-Stat3 binding site in regulating Bv8 promoter activity, we compared Dual-Luciferase activities driven by the Bv8 promoter region from −1762 to +90 or by the same region with the phospho-stat3 ISRE consensus sequence mutated or deleted after HEK293T cells had been co-transfected with plasmid expressing mouse Stat3 ORF or control vector for 48 h (Fig. 5, F and G). As shown in Fig. 5G, when cells were co-transfected with control vector, both the wild type and the mutated/deleted 1.85-kb Bv8 promoter region, which contained the TATA box, were able to drive luciferase activity at comparable levels. However, when cells were co-transfected with plasmids expressing mouse Stat3 ORF, only the wild type 1.85-kb Bv8 promoter region resulted in significant increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 5G). The luciferase activity driven by the mutated or deleted Bv8 promoter region remained at a similar level as that in cells co-transfected with control vector.

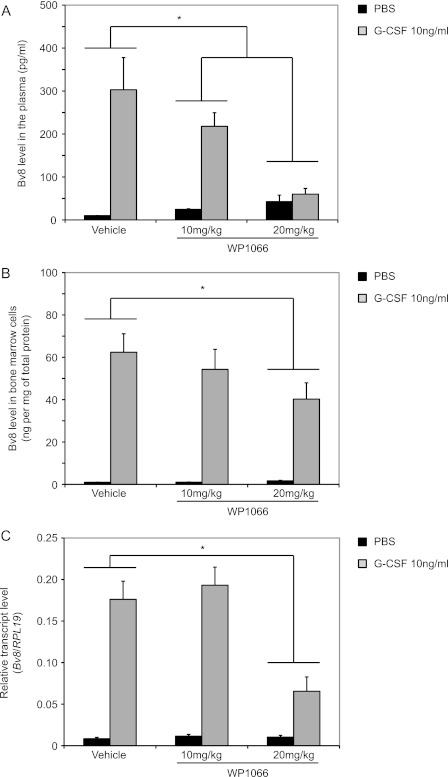

In Vivo Up-regulation of Bv8 Expression by G-CSF Is Reduced by Stat3 Inhibitor

We reported that G-CSF administration results in time- and dose-dependent increases in the levels of Bv8 protein in the bone marrow and in the serum of mice (11). We sought to determine whether such Bv8 increases could be also reduced by simultaneous treatment with WP1066 in vivo. In agreement with these studies, Bv8 expression levels in the bone marrow cells increased ∼60-fold above background levels following G-CSF administration for three consecutive days (Fig. 6, B and C). Serum Bv8 levels were also markedly increased (Fig. 6A). Vehicle had no significant effect on Bv8 levels in serum and bone marrow cells (data not shown). ELISA demonstrated a significant dose-dependent reduction in Bv8 levels, both in the plasma and in the bone marrow of mice treated with WP1066 when compared with vehicle-treated mice. In the presence of 20 mg/kg WP1066, Bv8 levels in the plasma of G-CSF-treated mice were comparable with those in PBS-treated mice (Fig. 6A). ELISA (Fig. 6B) and TaqMan data (Fig. 6C) indicated that 20 mg/kg WP1066 resulted in more than 60% Bv8 reduction in bone marrow cells.

FIGURE 6.

WP1066 reduces the Bv8 increases in peripheral blood and bone marrow cells following in vivo administration of G-CSF. A and B, Bv8 concentrations by ELISA in plasma (A) and bone marrow cells (B). C, Bv8 expression in bone marrow cells. ELISA data were normalized to total protein concentrations. Error bars represent S.E. Asterisks indicate significant difference between WP1066- and vehicle-treated groups (p < 0.05).

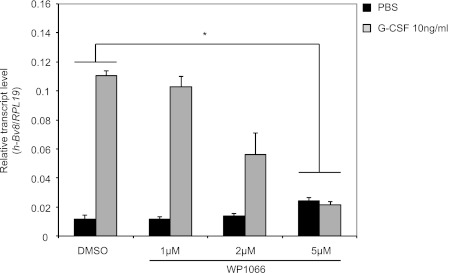

Stat3 Inhibitor Suppresses G-CSF-induced Bv8 Expression in Human Bone Marrow Cells

Earlier studies reported that G-CSF induces Bv8 expression in human bone marrow cells (23). To determine whether Stat3 plays a role in regulating G-CSF-induced Bv8 expression, human bone marrow cells were pretreated with WP1066 at various concentrations. In agreement with the aforementioned studies (23), 10 ng/ml G-CSF resulted in over 10-fold induction of Bv8 expression within 4 h (Fig. 7). WP1066 reduced G-CSF stimulated Bv8 expression in a dose-dependent manner, with complete inhibition at the concentration of 5 μm (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Stat3 signaling is required for G-CSF-dependent Bv8 induction in human bone marrow cells. Human Bv8 expression by TaqMan in pooled human bone marrow cells after pretreatment with different concentrations of WP1066 for 1 h followed by incubation with 10 ng/ml human G-CSF for additional 4 h. Error bars represent S.E. Asterisk indicates significant difference between WP1066- and DMSO-treated groups (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Angiogenesis plays an important role in tumor progression and metastasis. Inhibiting angiogenesis represents a clinically validated anticancer strategy (29–32). Although tumor cells have been traditionally thought to be the major source of angiogenic factors (33), tumor stromal cells, such as fibroblast, mesenchymal stem cells, immune cells, and different subpopulations of myeloid cells, are being increasingly recognized as sources of various proangiogenic factors (34–38). CD11b+ Gr1+ cells, a subpopulation of myeloid cells that includes neutrophils, macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (39), have been shown not only to contribute to tumor angiogenesis (11, 12, 15, 40, 41) but also to mediate refractoriness to anti-VEGF therapy (18, 41) as well as stimulate the formation of premetastatic niches that facilitate the metastatic process (42).

In evaluating the mechanism of angiogenesis mediated by CD11b+ Gr1+ cells, recent studies identified Bv8 as a critical mediator, and G-CSF was identified as a major inducer of Bv8 expression in vitro and in vivo (11). The observation that neutralizing anti-G-CSF antibodies abrogated the increase in Bv8 expression in CD11b+ Gr1+ cells following tumor implantation suggested a communication between tumor and CD11b+ Gr1+ cells, mediated by G-CSF. Most recently, we identified G-CSF as a key initiator and regulator of lung metastasis, which depends on Bv8-expressing Ly6G+ Ly6C+ cells. Neutralization of G-CSF, Bv8, or Ly6G+ Ly6C+ cells reduced metastasis (42). Therefore, to better understand the role of G-CSF and Bv8 in tumorigenesis, it is important to define the molecular mechanism responsible for G-CSF-induced Bv8 up-regulation.

The major signaling pathways regulated by G-CSF include the MEK/ERK and Jak/Stat pathways (24, 25). Using pharmacological inhibitors that interfere with those pathways, we ruled out the involvement of the MEK/ERK signaling because two independent MEK-1 inhibitors, PD98059 and GDC-0973, did not significantly reduce G-CSF-stimulated Bv8 expression. However, Stat3 inhibition using WP1066 or by siRNA significantly reduced Bv8 levels in bone marrow cells. In contrast, induction of Stat1 and Stat5 phosphorylation by G-CSF was much weaker (Fig. 2C). Blocking Stat1 or Stat5 activity had no significant effect on G-CSF-induced Bv8 expression. Our observation is consistent with previous studies reporting redundancy among the Jak kinases in G-CSF signaling (25), whereas Stats play an essential and nonredundant role (43–46). Indeed, several studies show that G-CSF stimulation mainly activates Stat3, and to a lesser extent Stat1 and Stat5, in bone marrow cells (43, 45, 47–49).

ChIP assay confirmed that phospho-Stat3 can directly bind to the Bv8 promoter. Dual-Luciferase assays further confirmed that the phospho-Stat3 binding site is a functional enhancer of the Bv8 promoter.

We identified CD11b+ Gr1+ cells as the primary cell population in which Stat3 signaling is activated by G-CSF. The finding that IL6 and IL10, two cytokines known to activate Stat3 signaling in bone marrow cells but having no effect on Bv8 expression, induce Stat3 phosphorylation mainly in CD11b− Gr1− cells supports the hypothesis that Stat3-mediated Bv8 expression is cell type-dependent. Our experiments provide evidence that such cell type-specific response is likely due to the distinct expression levels of the G-CSF receptor in CD11b+ Gr1+ versus CD11b− Gr1− cells. The finding that Bv8 expression in human bone marrow cells is also Stat3-dependent suggests that such a signaling pathway may also play a critical role in regulating Bv8 expression in human bone marrow-derived cells.

As already pointed out, Stat3 has been shown to be a central regulator of inflammation-associated tumorigenesis, including myeloid cell-dependent tumor promotion (19). We propose that such a role of Stat3 reflects, at least in part, its ability to regulate the G-CSF-Bv8 signaling axis, as reported here. Additional studies are required to further define the role of G-CSF-Stat3-Bv8 signaling in various tumor types as well as other pathophysiological conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bioinformatics Department, the Flow Cytometry laboratory, and the Animal Care facility for help. We also thank A. Chung for reading the manuscript, X. Wu for help with in vivo studies, and M. Tan for Bv8 ELISA.

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- EG-VEGF

- endocrine gland-derived VEGF

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA end

- ISRE

- interferon-sensitive response element

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Li M., Bullock C. M., Knauer D. J., Ehlert F. J., Zhou Q. Y. (2001) Identification of two prokineticin cDNAs: recombinant proteins potently contract gastrointestinal smooth muscle. Mol. Pharmacol. 59, 692–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. LeCouter J., Kowalski J., Foster J., Hass P., Zhang Z., Dillard-Telm L., Frantz G., Rangell L., DeGuzman L., Keller G. A., Peale F., Gurney A., Hillan K. J., Ferrara N. (2001) Identification of an angiogenic mitogen selective for endocrine gland endothelium. Nature 412, 877–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mollay C., Wechselberger C., Mignogna G., Negri L., Melchiorri P., Barra D., Kreil G. (1999) Bv8, a small protein from frog skin and its homologue from snake venom induce hyperalgesia in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 374, 189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Masuda Y., Takatsu Y., Terao Y., Kumano S., Ishibashi Y., Suenaga M., Abe M., Fukusumi S., Watanabe T., Shintani Y., Yamada T., Hinuma S., Inatomi N., Ohtaki T., Onda H., Fujino M. (2002) Isolation and identification of EG-VEGF/prokineticins as cognate ligands for two orphan G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293, 396–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin D. C., Bullock C. M., Ehlert F. J., Chen J. L., Tian H., Zhou Q. Y. (2002) Identification and molecular characterization of two closely related G-protein-coupled receptors activated by prokineticins/endocrine gland vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19276–19280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Melchiorri D., Bruno V., Besong G., Ngomba R. T., Cuomo L., De Blasi A., Copani A., Moschella C., Storto M., Nicoletti F., Lepperdinger G., Passarelli F. (2001) The mammalian homologue of the novel peptide Bv8 is expressed in the central nervous system and supports neuronal survival by activating the MAP kinase/PI 3-kinase pathways. Eur. J. Neurosci. 13, 1694–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng M. Y., Bullock C. M., Li C., Lee A. G., Bermak J. C., Belluzzi J., Weaver D. R., Leslie F. M., Zhou Q. Y. (2002) Prokineticin 2 transmits the behavioral circadian rhythm of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nature 417, 405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. LeCouter J., Lin R., Tejada M., Frantz G., Peale F., Hillan K. J., Ferrara N. (2003) The endocrine-gland-derived VEGF homologue Bv8 promotes angiogenesis in the testis: localization of Bv8 receptors to endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2685–2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. LeCouter J., Zlot C., Tejada M., Peale F., Ferrara N. (2004) Bv8 and endocrine gland-derived vascular endothelial growth factor stimulate hematopoiesis and hematopoietic cell mobilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 16813–16818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giannini E., Lattanzi R., Nicotra A., Campese A. F., Grazioli P., Screpanti I., Balboni G., Salvadori S., Sacerdote P., Negri L. (2009) The chemokine Bv8/prokineticin 2 is up-regulated in inflammatory granulocytes and modulates inflammatory pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14646–14651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shojaei F., Wu X., Zhong C., Yu L., Liang X. H., Yao J., Blanchard D., Bais C., Peale F. V., van Bruggen N., Ho C., Ross J., Tan M., Carano R. A., Meng Y. G., Ferrara N. (2007) Bv8 regulates myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis. Nature 450, 825–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shojaei F., Singh M., Thompson J. D., Ferrara N. (2008) Role of Bv8 in neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis in a transgenic model of cancer progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2640–2645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Christopher M. J., Link D. C. (2007) Regulation of neutrophil homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 14, 3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Smith T. J., Khatcheressian J., Lyman G. H., Ozer H., Armitage J. O., Balducci L., Bennett C. L., Cantor S. B., Crawford J., Cross S. J., Demetri G., Desch C. E., Pizzo P. A., Schiffer C. A., Schwartzberg L., Somerfield M. R., Somlo G., Wade J. C., Wade J. L., Winn R. J., Wozniak A. J., Wolff A. C. (2006) 2006 update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 3187–3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okazaki T., Ebihara S., Asada M., Kanda A., Sasaki H., Yamaya M. (2006) Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor promotes tumor angiogenesis via increasing circulating endothelial progenitor cells and Gr1+CD11b+ cells in cancer animal models. Int. Immunol. 18, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Voloshin T., Gingis-Velitski S., Bril R., Benayoun L., Munster M., Milsom C., Man S., Kerbel R. S., Shaked Y. (2011) G-CSF supplementation with chemotherapy can promote revascularization and subsequent tumor regrowth: prevention by a CXCR4 antagonist. Blood 118, 3426–3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Natori T., Sata M., Washida M., Hirata Y., Nagai R., Makuuchi M. (2002) G-CSF stimulates angiogenesis and promotes tumor growth: potential contribution of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297, 1058–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shojaei F., Wu X., Qu X., Kowanetz M., Yu L., Tan M., Meng Y. G., Ferrara N. (2009) G-CSF-initiated myeloid cell mobilization and angiogenesis mediate tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF therapy in mouse models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6742–6747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yu H., Pardoll D., Jove R. (2009) STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 798–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kujawski M., Kortylewski M., Lee H., Herrmann A., Kay H., Yu H. (2008) Stat3 mediates myeloid cell-dependent tumor angiogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3367–3377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bollrath J., Phesse T. J., von Burstin V. A., Putoczki T., Bennecke M., Bateman T., Nebelsiek T., Lundgren-May T., Canli O., Schwitalla S., Matthews V., Schmid R. M., Kirchner T., Arkan M. C., Ernst M., Greten F. R. (2009) gp130-mediated Stat3 activation in enterocytes regulates cell survival and cell cycle progression during colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 15, 91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kortylewski M., Xin H., Kujawski M., Lee H., Liu Y., Harris T., Drake C., Pardoll D., Yu H. (2009) Regulation of the IL-23 and IL-12 balance by Stat3 signaling in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 15, 114–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhong C., Qu X., Tan M., Meng Y. G., Ferrara N. (2009) Characterization and regulation of Bv8 in human blood cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 2675–2684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Avalos B. R. (1996) Molecular analysis of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor. Blood 88, 761–777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kamezaki K., Shimoda K., Numata A., Haro T., Kakumitsu H., Yoshie M., Yamamoto M., Takeda K., Matsuda T., Akira S., Ogawa K., Harada M. (2005) Roles of Stat3 and ERK in G-CSF signaling. Stem Cells 23, 252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Frémin C., Meloche S. (2010) From basic research to clinical development of MEK1/2 inhibitors for cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 3, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnston S. (2007) AACR-NCI-EORTC Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics, San Francisco, CA, October 22–26, 2007, Abstract No. C209, American Association for Cancer Research, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iwamaru A., Szymanski S., Iwado E., Aoki H., Yokoyama T., Fokt I., Hess K., Conrad C., Madden T., Sawaya R., Kondo S., Priebe W., Kondo Y. (2007) A novel inhibitor of the STAT3 pathway induces apoptosis in malignant glioma cells both in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene 26, 2435–2444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chung A. S., Lee J., Ferrara N. (2010) Targeting the tumor vasculature: insights from physiological angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferrara N., Mass R. D., Campa C., Kim R. (2007) Targeting VEGF-A to treat cancer and age-related macular degeneration. Annu. Rev. Med. 58, 491–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carmeliet P. (2003) Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat. Med. 9, 653–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kerbel R. S. (2008) Tumor angiogenesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 2039–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ferrara N. (2004) Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr. Rev. 25, 581–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lin W. W., Karin M. (2007) A cytokine-mediated link between innate immunity, inflammation, and cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1175–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coussens L. M., Werb Z. (2002) Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420, 860–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karnoub A. E., Dash A. B., Vo A. P., Sullivan A., Brooks M. W., Bell G. W., Richardson A. L., Polyak K., Tubo R., Weinberg R. A. (2007) Mesenchymal stem cells within tumor stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature 449, 557–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Orimo A., Weinberg R. A. (2006) Stromal fibroblasts in cancer: a novel tumor-promoting cell type. Cell Cycle 5, 1597–1601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shaked Y., Voest E. E. (2009) Bone marrow-derived cells in tumor angiogenesis and growth: are they the good, the bad, or the evil? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1796, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gabrilovich D. I., Nagaraj S. (2009) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 162–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shojaei F., Zhong C., Wu X., Yu L., Ferrara N. (2008) Role of myeloid cells in tumor angiogenesis and growth. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 372–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shojaei F., Wu X., Malik A. K., Zhong C., Baldwin M. E., Schanz S., Fuh G., Gerber H. P., Ferrara N. (2007) Tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF treatment is mediated by CD11b+Gr1+ myeloid cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 911–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kowanetz M., Wu X., Lee J., Tan M., Hagenbeek T., Qu X., Yu L., Ross J., Korsisaari N., Cao T., Bou-Reslan H., Kallop D., Weimer R., Ludlam M. J., Kaminker J. S., Modrusan Z., van Bruggen N., Peale F. V., Carano R., Meng Y. G., Ferrara N. (2010) Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor promotes lung metastasis through mobilization of Ly6G+Ly6C+ granulocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21248–21255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Meraz M. A., White J. M., Sheehan K. C., Bach E. A., Rodig S. J., Dighe A. S., Kaplan D. H., Riley J. K., Greenlund A. C., Campbell D., Carver-Moore K., DuBois R. N., Clark R., Aguet M., Schreiber R. D. (1996) Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell 84, 431–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thierfelder W. E., van Deursen J. M., Yamamoto K., Tripp R. A., Sarawar S. R., Carson R. T., Sangster M. Y., Vignali D. A., Doherty P. C., Grosveld G. C., Ihle J. N. (1996) Requirement for Stat4 in interleukin-12-mediated responses of natural killer and T cells. Nature 382, 171–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Teglund S., McKay C., Schuetz E., van Deursen J. M., Stravopodis D., Wang D., Brown M., Bodner S., Grosveld G., Ihle J. N. (1998) Stat5a and Stat5b proteins have essential and nonessential, or redundant, roles in cytokine responses. Cell 93, 841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Takeda K., Tanaka T., Shi W., Matsumoto M., Minami M., Kashiwamura S., Nakanishi K., Yoshida N., Kishimoto T., Akira S. (1996) Essential role of Stat6 in IL-4 signaling. Nature 380, 627–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nicholson S. E., Novak U., Ziegler S. F., Layton J. E. (1995) Distinct regions of the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor are required for tyrosine phosphorylation of the signaling molecules JAK2, Stat3, and p42, p44MAPK. Blood 86, 3698–3704 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tian S. S., Lamb P., Seidel H. M., Stein R. B., Rosen J. (1994) Rapid activation of the STAT3 transcription factor by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood 84, 1760–1764 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McLemore M. L., Grewal S., Liu F., Archambault A., Poursine-Laurent J., Haug J., Link D. C. (2001) STAT-3 activation is required for normal G-CSF-dependent proliferation and granulocytic differentiation. Immunity 14, 193–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Belvin M., Chan I. T., Friedman L., Hoeflich K. P., Prescott J., Wallin J. (April 14, 2011) U. S. Patent 20,110,086,837

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.