Background: Intrauterine estrogen plays a critical role in differentiation of endometrial stromal cells during decidualization.

Results: FRA-1 is a downstream target of estrogen receptor regulation in the uterine stroma. Loss of FRA-1 expression inhibits stromal cell differentiation and migration.

Conclusion: FRA-1 regulates stromal differentiation and remodeling during early pregnancy.

Significance: This study identifies a novel downstream mediator of estrogen receptor signaling during decidualization.

Keywords: Cell Migration, Estrogen, Estrogen Receptor, Gene Expression, Uterus

Abstract

Concerted actions of estrogen and progesterone via their cognate receptors orchestrate changes in the uterine tissue, regulating implantation during early pregnancy. The uterine stromal cells undergo steroid-dependent differentiation into morphologically and functionally distinct decidual cells, which support embryonic growth and survival. The hormone-regulated pathways underlying this unique cellular transformation are not fully understood. Previous studies in the mouse revealed that, following embryo attachment, de novo synthesis of estrogen by the decidual cells is critical for stromal differentiation. In this study we report that Fos-related antigen 1 (FRA-1), a member of the Fos family of transcription factors, is a downstream target of regulation by intrauterine estrogen. FRA-1 expression was localized in the differentiating uterine stromal cells surrounding the implanted embryo. Attenuation of estrogen receptor α (Esr1) expression by siRNA mediated silencing in primary uterine stromal cells suppressed FRA-1 expression. Furthermore, chromatin immunoprecipitation demonstrated direct recruitment of ESR1 to an estrogen response element in the Fra-1 promoter. Down-regulation of Fra-1 expression during in vitro decidualization blocked stromal differentiation and resulted in a marked decrease in stromal cell migration. Interestingly, FRA-1 controls the expression of matrix metalloproteinases MMP9 and MMP13, which are critical modulators of stromal extracellular matrix remodeling. Collectively, these results suggest that FRA-1, induced in response to estrogen signaling via ESR1, is a key regulator of stromal differentiation and remodeling during early pregnancy.

Introduction

Implantation, a critical event in early pregnancy, is initiated by attachment of the blastocyst to the uterine luminal epithelium. In rodents and humans, as the embryo breaches the luminal epithelium following attachment and invades into the stroma, the stromal cells undergo a dramatic transformation to form a specialized tissue, known as the decidua. During this process, termed as decidualization, fibroblastic stromal cells proliferate and then differentiate into the secretory decidual cells that support embryo growth and survival until placentation ensues (1–4). The decidual tissue also undergoes extensive remodeling to control embryo invasion and accommodate the growing embryo. As the decidua forms around the implanted embryo, the uterine endothelial cells proliferate to create an extensive vascular network, which is embedded in the decidua and critical for embryo development (5, 6). These morphological and functional changes in the pregnant uterus are regulated by the actions of the steroid hormones 17β-estradiol (E)2 and progesterone (P), which act via their cognate nuclear receptors to control the expression of critical gene networks (7).

It is well documented that the ovarian E and P regulate preimplantation epithelial receptivity, leading to embryo attachment (1–4, 8). Previous studies, using genetically engineered mouse models, established that P signaling via the progesterone receptor is critical for decidualization (9). Our recent studies showed that the decidual stromal cells express an enzymatic machinery that supports intrauterine steroidogenesis (10). Specifically, we noted a marked induction of expression of P450 aromatase, a key enzyme that converts androgens to E. We also provided evidence that, in the absence of ovarian E, this locally produced E, acting in concert with P, is able to support the advancement of stromal differentiation. Consistent with this finding, treatment of these mice with letrozole, a specific inhibitor of P450 aromatase, blocked uterine stromal differentiation and impaired development of the angiogenic network in the stroma (10).

To delineate the pathways controlled by intrauterine E during decidualization, we analyzed gene expression profiles of uterine tissue subjected to experimentally induced decidualizaion in the presence or absence of letrozole treatment (10). Our study revealed that Fos-related antigen 1 (Fra-1) is one of the genes whose expression is down-regulated in the letrozole-treated uteri. The FRA-1 protein belongs to the Fos family of transcription factors, which also includes c-Fos, FosB, and FRA-2, and participates in the formation of the dimeric transcription factor, activator protein-1, in partnership with the Jun family proteins (11). The FRA-1 activity is implicated in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and remodeling in a variety of tissues (12–14). At the gene and protein levels, FRA-1 exhibits maximum homology to c-Fos, a well known target of regulation by estrogen receptor α (ESR1) (15, 16). Interestingly, E regulation of c-Fos expression was observed previously in the luminal and glandular epithelia of the uterus (17).

In this study, we addressed the regulation and function of FRA-1 during endometrial stromal cell differentiation. Our study provides strong evidence that the intrauterine E signals via ESR1 to regulate Fra-1 expression in differentiating uterine stromal cells. Using a primary culture system in which undifferentiated stromal cells isolated from pregnant mouse uterus undergo decidualization, we demonstrated that the loss of FRA-1 expression prevents stromal differentiation and migration during early pregnancy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Progesterone and 17β-estradiol were purchased from Sigma. Antibodies against FRA-1, ESR1, and calnexin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Animals and Tissue Collection

All experiments involving animals were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and the studies were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health standards for the use and care of animals. Female mice (CD-1 from Charles River, Wilmington, MA) in proestrus, were mated with adult males. The presence of a vaginal plug after mating was designated as day 1 of pregnancy. The animals were euthanized at various stages of gestation, and the uteri were collected.

Artificial Decidualization

Decidualization was experimentally induced in hormone-primed mice as described previously (18). Briefly, mice were ovariectomized and 2 weeks following ovariectomy, were injected with 100 ng of E in 0.1 ml of sesame oil for 3 consecutive days. This was followed by daily injections of 1 mg of P for 3 consecutive days. Decidualization was initiated in one horn by injection of 50 μl of oil. The other horn was left unstimulated. The animals were treated with P for an additional 3 days after stimulation and then euthanized to collect the uterine tissue.

Primary Stromal Cell Culture

Isolation of primary stromal cells was performed as described previously (19). Briefly, uteri were collected from day 4 pregnant mice and subjected to enzymatic digestion using pancreatin and dispase enzymes for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction was terminated upon addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and the supernatant containing the epithelial cell clumps was discarded. The partially digested tissue was then incubated with collagenase at 37 °C for 45 min. The reaction was again terminated by adding 10% FBS, and the suspension was vortexed to disperse stromal cells. The resulting suspension was passed through a sieve (80 μm) to further enrich the stromal cell population. Stromal cells were then cultured in DMEM containing 2% FBS and P (1 μm) to induce differentiation.

Immunohistochemistry

Polyclonal antibody against FRA-1 was used for immunohistochemistry as described previously (20). Briefly, paraffin-embedded uterine tissue was sectioned at 4 μm and mounted on slides. Sections were rehydrated and washed in PBS for 20 min and then incubated in a blocking solution containing 10% normal goat serum for 30 min before incubation with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Immunostaining was performed using Avidin-Biotin kit for rabbit primary antibody (Invitrogen). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, mounted, and examined under bright field. Red deposits indicate the sites of positive immunostaining.

Western Blotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared from mouse primary stromal cell cultures undergoing in vitro differentiation. Briefly, cells were washed with ice-cold balanced solution and lysed with the radioimmuneprecipitation assay buffer (0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40 in PBS) containing protease inhibitor mixture, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, 0.1 mg/ml), and phosphatase inhibitor (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich). This was followed by passing the cells through a 25-gauge syringe and centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min to remove the cell debris. Typically 20–50 μg of the protein extract was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Amersham Biosciences). The membrane was blocked with 5% albumin in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with a primary antibody against FRA-1, ESR1, or calnexin. The blot was then incubated with the corresponding HRP-conjugate secondary antibody for 45 min at room temperature. The HRP was detected by chemiluminescence.

Alkaline Phosphatase Activity Assay

For detecting alkaline phosphatase activity, cultured stromal cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 10 min and were incubated in the dark at 37 ºC for 60 min in 2 mm α-naphthyl phosphate and 4 mm Fast Violet in 0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 8.7. In presence of the substrate α-naphthyl phosphate, alkaline phosphatase activity releases orthophosphate and naphthol derivatives from the substrate. The naphthol derivatives are simultaneously coupled with the diazonium salt present in the incubating medium to form a dark dye marking the site of enzyme action. The slides were rinsed in water to terminate the enzymatic reaction and visualized under a microscope.

siRNA Transfection

siRNA corresponding to mouse Fra-1 (5′-3′ sense GGAAGGAACUGACCGACUUtt and antisense AAGUCGGUCAGUUCCUUCCtc), mouse Esr1 (5′-3′ sense GGGAGAAUGUUGAAGGCACAtt and antisense UGUGCUUCAACAUUCUCCCtc) and a scrambled negative control were obtained (Ambion, Austin, TX) and transfected using the siPORT NeoFX transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, the annealed oligonucleotide was complexed with the transfecting reagent in Opti-MEM I reduced serum medium. The complex containing 20 nm siRNA in 5 μl of the reagent was dispersed into culture plates while the primary cells were attaching. The cells were again subjected to a second administration of siRNA after 36 h with the Silent Fect reagent (Bio-Rad) and cultured for an additional 24–48 h before analyzing gene expression.

ChIP Assay

Primary stromal cells isolated from day 4 pregnant mouse uterus were cultured for 24 h in the presence of steroid hormones. ChIP was performed using a commercially available kit from Upstate Biotech according to the manufacturer's instruction (Millipore). Briefly, 1.5 × 107 to 2 × 107 primary stromal cells were isolated from day 4 pregnant mouse uteri and cultured in 15-cm plates in the presence of P. After 24 h, the chromatin was cross-linked by adding 1% formaldehyde to the tissue culture medium for 10 min at room temperature followed by addition of 1 m glycine for 5 min. The cross-linked chromatin was sonicated to obtain DNA fragments ranging from 200 bp to 1 kb. The sonicated chromatin was diluted in ChIP dilution buffer and precleared using protein G-agarose. The input sample is 1% of the precleared supernatant. Immunoprecipitation was performed overnight at 4 °C with 5 μg of ESR1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1 μg of RNA polymerase II, and the nonspecific anti-mouse IgG antibodies. The immune complexes were further precipitated using protein-agarose beads washed with buffers, followed by elution of the protein-DNA complexes. Reverse cross-linking was then performed at 65 °C for 5 h, and the DNA was purified using spin columns. Quantitative and regular PCR were performed on these purified DNA samples using specific primers.

Wound Healing Assay

Primary stromal cells were cultured in the presence of steroid hormones to induce differentiation. The confluent monolayer of mouse stromal cells was uniformly scratched with a 10-μl sterile pipette tip. The cell debris were washed away, and the remaining cells were cultured in fresh medium for an additional 48 h. Wound width was monitored by phase contrast microscopy at regular intervals. The extent of cell migration was assessed by calculating the wound closure and expressed as a percentage of the initial wound.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least three or four times in independent trials. Real-time PCRs for each gene and sample were performed in three or four replicates. Statistical significance was assessed by analysis of variance at a significance level of p < 0.05 and is indicated by an asterisk in the figures.

RESULTS

Intrauterine E Regulates FRA-1 Expression in Mouse Uterus during Decidualization

Our previous study showed that treatment with letrozole blocks the uterine biosynthesis of E and prevents decidualization (10). To identify pathways that operate downstream of intrauterine E to critically control decidualization, we examined the changes in uterine mRNA expression profiles in response to letrozole treatment. As described previously, uteri were collected from untreated or letrozole-treated mice 72 h following administration of the decidual stimulus, and total RNA isolated from these tissues was subjected to microarray analysis (10). We identified several hundred mRNAs whose expression was altered significantly in the decidual uterus in response to letrozole. One of the mRNAs, whose level was markedly down-regulated in response of letrozole, encoded FRA-1, a member of the Fos family of transcription factors (11). We verified the results of the microarray analysis by performing real-time PCR analysis of RNA obtained from uteri of untreated and letrozole-treated mice. Our results confirmed a significant down-regulation of Fra-1 mRNA upon letrozole treatment relative to the untreated control (Fig. 1A). This inhibition of gene expression was specific because the expression of Esr1 was not significantly altered in response to letrozole.

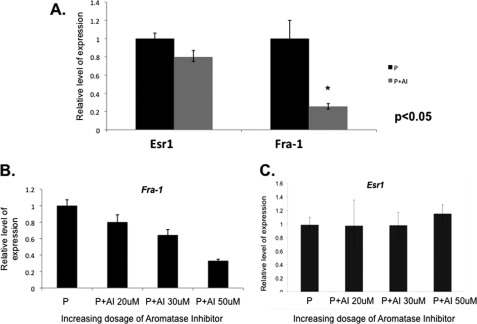

FIGURE 1.

E signaling regulates Fra-1 expression during decidualization. A, mice were ovariectomized and subjected to artificially induced decidualization as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cohorts of these animals were treated with progesterone alone (P) or P along with aromatase inhibitor (P + AI), and the uterine horns were separately collected after 72 h of stimulus (n = 5). Total RNA was isolated from these uterine samples, and real-time PCR analysis was performed using Fra-1- and Esr1-specific primers. B and C, stromal cells isolated from mice on day 4 of pregnancy were subjected to in vitro decidualization in the presence of increasing concentrations of aromatase inhibitor (AI) for 72 h. The RNA was analyzed by real-time PCR to monitor the expression of the Fra-1 and Esr1 transcript. Error bars, S.E.

To analyze further the regulation of Fra-1 expression by intrauterine E, we used a well established in vitro decidualization system. We showed previously that primary cultures of stromal cells isolated from pregnant (day 4) uteri undergo decidualization in the presence of P, which acts in concert with E produced by the decidual cells to promote the differentiation process (10). As shown in Fig. 1B, inhibition of E biosynthesis in primary stromal cell cultures by addition of increasing amounts of letrozole impaired Fra-1 mRNA expression but not Esr1 expression in a dose-dependent manner, indicating that Fra-1 is indeed a downstream target of regulation by intrauterine E during early pregnancy (Fig. 1C).

Induction of FRA-1 during Decidualization

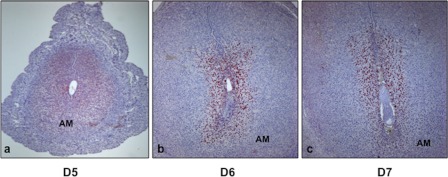

We next examined the spatial expression of FRA-1 in pregnant mouse uterus (Fig. 2, a–c). Using immunohistochemistry, we detected nuclear expression of FRA-1 in only sub-epithelial stromal cells at the implantation site on day 5 of pregnancy (a). As pregnancy progressed to days 6 and 7, the expression of FRA-1 intensified in the decidualizing stromal cells surrounding the implanted embryo (b and c). FRA-1 was strongly expressed in both antimesometrial and mesometrial decidual cells (b and c). These results showed that FRA-1 is localized specifically in differentiating stromal cells during early pregnancy.

FIGURE 2.

FRA-1 expression in mouse uterine stromal cells during in vivo decidualization. Uterine cross-sections were obtained from mice on different days of pregnancy (a–c). Immunohistochemical analysis was performed against FRA-1 on day 5 (a), day 6 (b), and day 7 (c) of gestation. AM indicates antimesometrial region of the uterus.

ESR1 Signaling Regulates FRA-1 Expression in Differentiating Stromal Cells

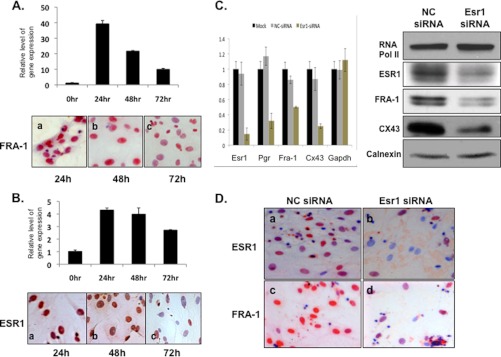

To examine whether the E regulation of Fra-1 in uterine stromal cells is mediated by ESR1, we employed the in vitro decidualization system. We observed that the expression profile of Fra-1 mRNA closely overlapped with that of Esr1 mRNA (Fig. 3, A and B, upper). Immunocytochemical studies confirmed a similar temporal pattern of expression and prominent nuclear localization of FRA-1 as well as ESR1 at 24 and 48 h of decidualization (Fig. 3, A and B, lower), consistent with the possibility that ESR1 regulates FRA-1 expression.

FIGURE 3.

Fra-1 is regulated by ESR1 during decidualization. Primary stromal cells isolated from day 4 pregnant mouse uterus were subjected to in vitro differentiation in the presence of P. A and B, cells were isolated to analyze the levels of Fra-1 (A, upper) and Esr1 (B, upper) mRNAs by real-time PCR. The protein levels of FRA-1 (A, lower) and ESR1 (B, lower) were analyzed by immunocytochemistry. C, endogenous expression of Esr1 mRNA was silenced by transfecting a siRNA specific to this transcript in mouse primary stromal cells. Cells were also transfected with a control scrambled (NC) siRNA. Mock represents treatment of cells with the transfection reagent without the oligonucleotides. After 48 h of transfection, RNA was subjected to real-time PCR, using gene-specific primers for Esr1, Pgr, Cx43, Fra-1, and GAPDH. The relative levels of gene expression in the Esr1 siRNA-treated samples compared with the mock or scrambled (NC) siRNA treatments are shown (left). Whole cell protein extracts obtained from Esr1 siRNA- and NC siRNA-treated cells were subjected to Western blot analysis using antibodies against FRA-1, ESR1, CX43, RNA polymerase II, and calnexin (right). D, endometrial stromal cells obtained from Esr1 siRNA- and NC siRNA-treated cells were subjected to immunocytochemical analysis using antibodies against ESR1 (upper) and FRA-1 (lower). Error bars, S.E.

To investigate the role of ESR1 in regulating Fra-1 expression, we employed an RNAi-mediated gene knockdown strategy. Cultured uterine stromal cells were treated with Esr1 mRNA-specific siRNA or negative control siRNA for 48 h. We observed that cells transfected with Esr1 siRNA exhibited >80% reduction in Esr1 mRNA expression compared with cells transfected with control siRNA (Fig. 3C, left). Down-regulation of Esr1 mRNA also led to a significant reduction in the level of well known targets of ESR signaling such as progesterone receptor (Pgr) and connexin 43 (Cx43) as well as Fra-1 mRNA expression, whereas the expression of GAPDH mRNA remained unaltered (Fig. 3C, left). Consistent with the observed alteration in the mRNA levels, those of ESR1, CX43, and FRA-1 proteins were also reduced in the Esr1 siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 3, C, right, and D). Taken together, these results indicated that E signaling via ESR1 regulates FRA-1 expression in uterine stromal cells.

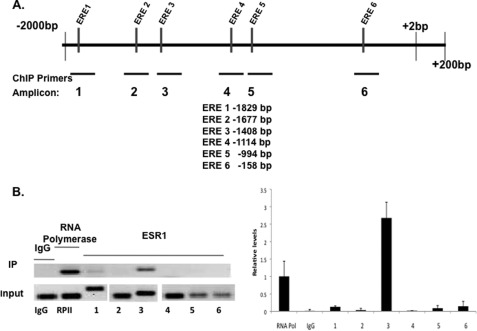

We next considered the possibility that the Fra-1 gene is a direct target of regulation by ESR1 during mouse stromal cell decidualization. We identified six putative binding sites for ESR1 in the Fra-1 promoter (Fig. 4A) using in silico analysis. We then performed ChIP analysis to examine ESR1 occupancy at these sites after 24 h of in vitro decidualization. As expected, a significant recruitment of RNA polymerase II was observed at the transcription initiation site of the Fra-1 gene at this time point (Fig. 4B). Little or no recruitment of ESR1 was seen at candidate estrogen response element (ERE) sites 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6. In contrast, a marked recruitment of ESR1 was observed at the region −1408 (ERE 3) of the Fra-1 promoter at 24 h of decidualization (Fig. 4B). This observation was consistent with a direct regulation of Fra-1 by ESR1 in the decidualizing stromal cells.

FIGURE 4.

Recruitment of ESR1 to the Fra-1 promoter. A, schematic representation of the potential ESR1 binding sites in Fra-1 gene (GenBank Accession No. AF017128). Putative EREs in the Fra-1 promoter region were determined by in silico analysis of the proximal promoter region (−1 to −2000 bp) using Consite and TESS software. Primers were designed to amplify specific regions containing ERE-like sequences, which exhibited variations of 2–3 bases from the consensus EREs. In ChIP, using ESR1 antibody, the candidate ESR1 binding sites are located at −1829 bp (ERE 1), −1677 bp (ERE 2), −1408 bp (ERE 3), −1114 bp (ERE 4), −994 bp (ERE 5), −158 bp (ERE 6), and the corresponding PCR amplicons, flanking each potential binding site, are amplicon 1 (−1964 to −1729), amplicon 2 (−1694 to −1505), amplicon 3 (−1523 to −1373), amplicon 4 (−1204 to −1050), amplicon 5 (−1071 to −931), and amplicon 6 (−275 to −118). In ChIP using RNA polymerase II antibody, RNA polymerase II binding was assessed using a primer set flanking the transcription initiation site. B, mouse primary stromal cells were cultured in the presence of P for 24 h, fixed with formaldehyde, and subjected to ChIP analysis. Immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed using the ESR1 antibody. IP with RNA polymerase II and IgG antibodies was used as the positive and negative control, respectively. The immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were recovered and amplified by PCR (32 cycles) using indicated primer pairs for each amplicon (upper). The input lane represents 1% of each soluble chromatin. IP lane represents the amplified PCR product for each amplicon. Relative levels of recruitment at various sites of the Fra-1 promoter were determined by real-time PCR and normalized to input DNA and RNAP II values. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments. Error bars, S.E.

Fra-1 Is Critical Mediator of Mouse Stromal Cell Decidualization

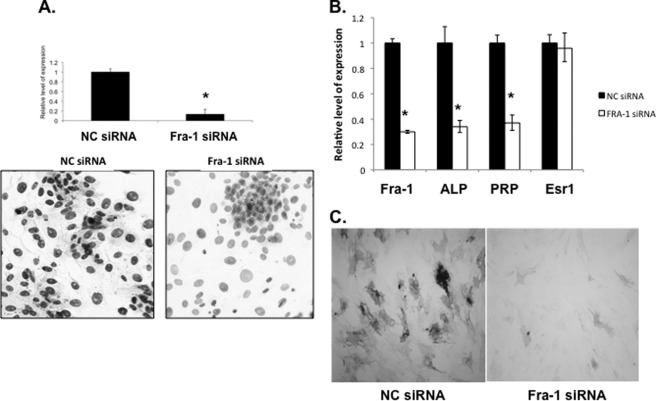

We next addressed the role of Fra-1 in stromal differentiation by RNAi-mediated knockdown of its mRNA expression. Primary stromal cells were isolated from uteri of day 4 pregnant mice as described previously and transfected with siRNA targeted specifically to the Fra-1 mRNA. Cells were also transfected with a scrambled siRNA (NC) as a control. Cells transfected with Fra-1 siRNA exhibited a remarkable decrease in Fra-1 mRNA expression (Fig. 5A, upper) and FRA-1 immunostaining (Fig. 5A, lower), whereas transfection with NC siRNA did not affect Fra-1 expression either at the transcript or protein level.

FIGURE 5.

Fra-1 is a critical regulator of mouse stromal cell decidualization. Primary mouse stromal cells transfected with Fra-1 and scrambled (NC) siRNA were collected 48 h after treatment. A, down-regulation of Fra-1 mRNA (upper) and protein (lower) was assessed by real-time PCR and immunocytochemistry, respectively. B, differential gene expression of decidualization markers such as alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and prolactin-related protein (PRP) in cells transfected with NC siRNA and Fra-1 siRNA was quantitated by real-time PCR. C, alkaline phosphatase activity in NC (left) and Fra-1 (right) siRNA-treated stromal cells. Error bars, S.E.

We next investigated the impact of this blockade of Fra-1 expression on stromal differentiation by monitoring the expression of mRNAs encoding well characterized decidualization markers, such as alkaline phosphatase and prolactin-related protein. The siRNA-mediated down-regulation of Fra-1 in stromal cells led to a sharp decline in the levels of mRNAs corresponding to alkaline phosphatase and prolactin-related protein (Fig. 5B) and also alkaline phosphatase activity (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the Esr1 mRNA level remained unaltered in cells treated with either Fra-1 or NC siRNA. These results showed that Fra-1 expression is critical for successful progression of uterine stromal cell decidualization.

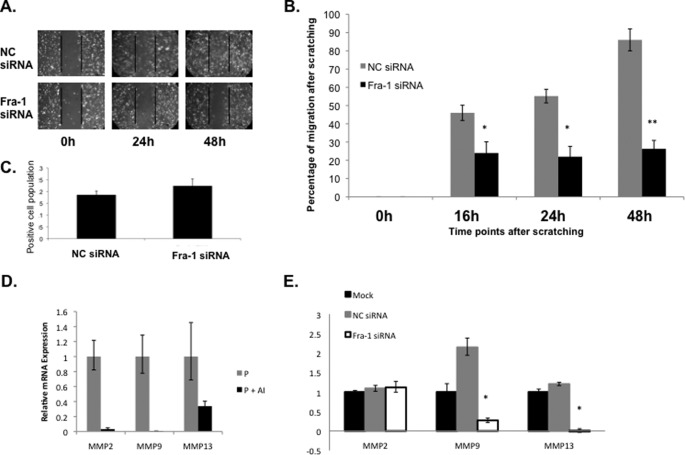

Fra-1 Regulates Stromal Cell Remodeling by Controlling Synthesis of Matrix Metalloproteinases

It is well known that the uterine stroma undergoes extensive remodeling, including stromal cell migration during decidualization, to accommodate the growing embryo. Because FRA-1 is a known regulator of cell migration in a variety of tissues, we next investigated whether FRA-1 serves a similar role during stromal decidualization. To assess stromal cell migration, we employed an in vitro wound-healing assay as described previously (21). As shown in Fig. 6A, stromal cells transfected with NC siRNA exhibited efficient would healing, indicative of proper cell migration. In contrast, the cells treated with Fra-1 siRNA displayed a significant decrease in cell motility compared with the cells transfected with NC siRNA. Quantification of wound closure demonstrated that the cells treated with NC siRNA exhibited >80% wound closure at 24 h and almost complete closure by 48 h (Fig. 6, A, upper, and B), whereas those treated with Fra-1 siRNA exhibited <30% wound closure even after 48 h of culture (Fig. 6, A, lower, and B).

FIGURE 6.

Fra-1 regulates uterine stromal remodeling. Primary mouse stromal cells were transfected with Fra-1-specific and scrambled (NC) siRNAs. siRNA-transfected confluent monolayer of primary stromal cells were subjected to wound-healing assay to monitor cell migration. A, cells were recorded photographically under phase contrast microscopy at 0, 24, and 48 h following application of the wound. B, quantitative representation of stromal cell migration from five independent experiments is shown. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.001. C, cells were fixed after 48 h of the migration assay and subjected to immunocytochemical analysis using anti-Ki67 antibody. Proliferation of stromal cells as indicated by Ki-67 positive staining was similar in response to NC and Fra-1 siRNA treatments. D and E, relative level of gene expression of MMP2, MMP9, and MMP13 was analyzed by real-time PCR analysis. Error bars, S.E.

To clarify further this impairment in wound closure in FRA-1-deficient cells, we assessed the proliferation status of these cells. Stromal cells transfected with control NC or Fra-1 siRNA were fixed at 48 h after the wound-healing assay and subjected to immunocytochemical analysis using the anti-Ki67 antibody. Drawing from five independent fields of NC and Fra-1 siRNA-transfected cells, the cells that displayed positive Ki67 staining were analyzed by paired t tests (Fig. 6C). We failed to observe any significant difference (p = 0.132) in cell proliferation between the two siRNA-treated cell populations. This indicated that the defect in wound healing in Fra-1-silenced cells is likely due to impaired cell migration, not proliferation.

Previous studies indicated that FRA-1 regulates the expression of specific matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in other tissues (22). Interestingly, our previous microarray experiments indicated that treatment with letrozole, which inhibits Fra-1 expression in the uterine stromal cells, also suppressed the expression of MMP2, MMP9, and MMP13 (10). We performed real-time PCR to confirm the results of our microarray analysis (Fig. 6D). These findings raised the possibility that the induction of Fra-1 expression downstream of intrauterine E signaling stimulates the expression of a group of MMPs that contribute to cell migration.

We, therefore, examined whether these MMPs are indeed regulated by FRA-1 during stromal cell migration and remodeling. To test this possibility, cells treated with NC- and Fra-1-specific siRNAs were subjected to a wound-healing assay, followed by RNA extraction and real-time PCR analysis to measure expression of these MMPs. We observed that loss of Fra-1 expression led to significant down-regulation of MMP9 and MMP13 mRNAs, whereas expression of MMP2 mRNA remained unaltered (Fig. 6E). The loss of Fra-1 expression led to significant down-regulation of MMP9 and MMP13 mRNAs, whereas the expression of MMP2 mRNA remained unaltered, indicating that FRA-1 specifically regulates MMP9 and MMP13, well known regulators of cell migration. It is conceivable that a factor other than FRA-1 functions downstream of intrauterine estrogen to regulate MMP2 mRNA expression. Collectively, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that FRA-1 regulates stromal cell migration by influencing expression of specific secreted factors, such as MMP9 and MMP13, which are likely modulators of the extracellular matrix in the stromal compartment during embryo implantation.

DISCUSSION

During early pregnancy in the mouse, E, along with P, plays a pivotal role in preparing the uterus for embryo implantation. Whereas ovarian E is critical during the preimplantation period, it is not essential for decidualization, which can proceed in ovariectomized mice when only P is provided exogenously. We previously reported that an intrauterine source of E in the decidua contributes significantly to stromal differentiation and uterine neovascularization following embryo attachment (10). There is strong evidence from our laboratory and elsewhere for the presence of a steroidogenic machinery in the stromal cells undergoing differentiation (23, 24). Particularly striking is the induction of P450 aromatase, which converts testosterone to E within the uterus. Blockade of this aromatase activity by letrozole inhibited decidualization as well as neovascularization, indicating an essential role of locally produced E in these processes. To understand the mechanisms by which the intrauterine E controls decidualization, we sought to identify the pathways regulated by this hormone in the uterus. When we disrupted E production by administering letrozole and performed gene expression profiling, we noted that the expression of Fra-1 in the decidual uterus was significantly repressed in response to letrozole. The present study shows that FRA-1 is a critical mediator of the actions of locally produced E during decidualization.

Although intrauterine E signaling is essential for decidualization, the precise mechanism by which it regulates the differentiation process is poorly understood. Our recent studies indicated that silencing of Esr1 expression by siRNAs in primary endometrial stromal cultures inhibited decidualization, thereby indicating an important role of ESR1-regulated pathways in this process.3 One of the well established mechanisms by which ESR1 regulates gene expression is by binding to the ERE(s) in the upstream regulatory region of a target gene. However, thus far, progesterone receptor (Pgr) is the only gene identified as a direct target of ESR1 in endometrial stromal cells. The observation that intrauterine E controls Fra-1 expression in decidual stromal cells, which also contain ESR1, raised the possibility that, during the early stages of differentiation, locally produced E acts via ESR1, which then directly controls Fra-1 expression in these cells. In support of this concept, we provide evidence that ESR1 binds specifically and strongly to the ERE located at −1400 region of the Fra-1 gene (Fig. 4B).

FRA-1 plays important roles in regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration in various tissues. Previous studies indicated that mice lacking c-Fos develop osteoporosis due to a defect in the osteoclast lineage. This defect in differentiation is rescued by overexpression of FRA-1, suggesting overlapping functions of c-Fos and FRA-1 in osteoclast differentiation (25). Additionally, ectopic expression of FRA-1 accelerates differentiation of osteoprogenitors to mature osteoblasts (26). Consistent with these observations, development of a conditional knock-out model of Fra-1 confirmed its critical role in osteoblast differentiation (27). Whereas expression of c-Fos and Jun proteins in the uterus had been previously reported, the expression and function of FRA-1 in stromal differentiation have not been investigated until now (17, 28). In this study, we observed robust nuclear expression of FRA-1 in differentiating endometrial stromal cells surrounding the implanted embryo. Attenuation of Fra-1 expression in primary stromal cells severely influenced the expression of well known decidualization biomarkers, indicating a key role of FRA-1 in stromal cell differentiation (Fig. 5B).

Our study also uncovered a role of FRA-1 in stromal cell migration during decidualization. During implantation, invasion of the embryo through the maternal decidua requires extensive remodeling of the uterine stromal compartment, particularly at the maternal-embryo interface. This remodeling involves migration and reorganization of the differentiating stromal cells to accommodate the growing embryo. Recently, to study stromal cell migration during decidualization, Grewal et al. employed a co-culture of human blastocyst and a monolayer of human endometrial stromal cells (21). Using time-lapse microscopy, they documented the migration of stromal cells away from the site of the embryo. Additionally, they used a wound-healing assay, a well established experimental read-out of cell migration and remodeling activities, to confirm the migratory properties of the differentiating human endometrial stromal cells. There is little doubt that such remodeling is also operational in the decidua during implantation in the mouse; however, the regulators of stromal cell migration during decidualization remain poorly understood. Previous reports suggested a role of FRA-1 in cell migration (29). We, therefore, assessed its role in stromal cell migration by using the wound-healing assay. Quantification of wound closure in stromal cells in which Fra-1 expression is silenced by siRNA revealed significant impairment in cell mobility compared with the control siRNA-treated stromal cells (Fig. 6). Furthermore, our studies indicated that the loss of local production of E and hence FRA-1 expression, is associated with decreased production of MMPs, which are well known regulators of extracellular matrix and tissue remodeling. These results are consistent with previous reports that FRA-1 governs the expression of MMP9 and MMP13 in various cell types and in pathological conditions, such as mesothelioma (22, 29, 30).

The connection between FRA-1 and the MMPs raises the possibility that the migration defect of FRA-1-deficient stromal cells is due to reduced expression of MMPs. Previous studies have shown that MMPs and the tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) play active roles in cell migration and remodeling in various tissues (31). Interestingly, it was previously reported that administration of hydroxamic acid, an inhibitor of MMPs, to pregnant mice severely impairs the progress of decidualization, indicating a critical role of MMPs in remodeling and maintenance of the implantation chamber (32). Our finding, that the expression of MMP9 and MMP13 is regulated by FRA-1 in differentiating endometrial stromal cells, is important because it provides a plausible mechanism by which this transcription factor, acting downstream of the signaling by intrauterine E, regulates remodeling of the stromal compartment during decidualization. Future studies will address the mechanisms by which FRA-1 regulates the MMPs and the MMPs, in turn, control uterine stromal remodeling during decidualization.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/National Institutes of Health through Grant U54 HD055787 as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research and also by Grant R01 HD 43381. This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant C06 RR16515–01 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (to I. C. B.).

A. Das, M. J. Laws, I. C. Bagchi, and M. K. Bagchi, unpublished results.

- E

- 17β-estradiol

- ERE

- estrogen response element

- ESR1

- estrogen receptor α

- FRA-1

- Fos-related antigen 1

- MMP

- matrix metalloproteinase

- P

- progesterone

- NC

- negative control.

REFERENCES

- 1. Carson D. D., Bagchi I., Dey S. K., Enders A. C., Fazleabas A. T., Lessey B. A., Yoshinaga K. (2000) Embryo implantation. Dev. Biol. 223, 217–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dey S. K., Lim H., Das S. K., Reese J., Paria B. C., Daikoku T., Wang H. (2004) Molecular cues to implantation. Endocr. Rev. 25, 341–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ramathal C. Y., Bagchi I. C., Taylor R. N., Bagchi M. K. (2010) Endometrial decidualization: of mice and men. Semin. Reprod. Med. 28, 17–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rubel C. A., Jeong J. W., Tsai S. Y., Lydon J. P., Demayo F. J. (2010) Epithelial-stromal interaction and progesterone receptors in the mouse uterus. Semin. Reprod. Med. 28, 27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hyder S. M., Stancel G. M. (1999) Regulation of angiogenic growth factors in the female reproductive tract by estrogens and progestins. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 806–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laws M. J., Taylor R. N., Sidell N., DeMayo F. J., Lydon J. P., Gutstein D. E., Bagchi M. K., Bagchi I. C. (2008) Gap junction communication between uterine stromal cells plays a critical role in pregnancy-associated neovascularization and embryo survival. Development 135, 2659–2668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tsai M. J., O'Malley B. W. (1994) Molecular mechanisms of action of steroid/thyroid receptor superfamily members. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63, 451–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoshinaga K., Adams C. E. (1966) Delayed implantation in the spayed, progesterone-treated adult mouse. J. Reprod. Fertil. 12, 593–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lydon J. P., DeMayo F. J., Funk C. R., Mani S. K., Hughes A. R., Montgomery C. A., Jr., Shyamala G., Conneely O. M., O'Malley B. W. (1995) Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev. 9, 2266–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Das A., Mantena S. R., Kannan A., Evans D. B., Bagchi M. K., Bagchi I. C. (2009) De novo synthesis of estrogen in pregnant uterus is critical for stromal decidualization and angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12542–12547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Milde-Langosch K. (2005) The Fos family of transcription factors and their role in tumourigenesis. Eur. J. Cancer 41, 2449–2461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frost J. A., Geppert T. D., Cobb M. H., Feramisco J. R. (1994) A requirement for extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) function in the activation of AP-1 by Ha-Ras, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, and serum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 3844–3848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chinenov Y., Kerppola T. K. (2001) Close encounters of many kinds: Fos-Jun interactions that mediate transcription regulatory specificity. Oncogene 20, 2438–2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adiseshaiah P., Lindner D. J., Kalvakolanu D. V., Reddy S. P. (2007) FRA-1 proto-oncogene induces lung epithelial cell invasion and anchorage-independent growth in vitro, but is insufficient to promote tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 67, 6204–6211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young M. R., Colburn N. H. (2006) Fra-1 a target for cancer prevention or intervention. Gene 379, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weisz A., Rosales R. (1990) Identification of an estrogen response element upstream of the human c-fos gene that binds the estrogen receptor and the AP-1 transcription factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 5097–5106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baker D. J., Nagy F., Nieder G. L. (1992) Localization of c-Fos-like proteins in the mouse endometrium during the peri-implantation period. Biol. Reprod 47, 492–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheon Y. P., DeMayo F. J., Bagchi M. K., Bagchi I. C. (2004) Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-2β, a cysteine protease inhibitor in decidua: a potential regulator of embryo implantation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10357–10363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Q., Kannan A., Wang W., Demayo F. J., Taylor R. N., Bagchi M. K., Bagchi I. C. (2007) Bone morphogenetic protein 2 functions via a conserved signaling pathway involving Wnt4 to regulate uterine decidualization in the mouse and the human. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31725–31732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Q., Cheon Y. P., Kannan A., Shanker S., Bagchi I. C., Bagchi M. K. (2004) A novel pathway involving progesterone receptor, 12/15-lipoxygenase-derived eicosanoids, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ regulates implantation in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11570–11581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grewal S., Carver J. G., Ridley A. J., Mardon H. J. (2008) Implantation of the human embryo requires Rac1-dependent endometrial stromal cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 16189–16194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Song Y., Qian L., Song S., Chen L., Zhang Y., Yuan G., Zhang H., Xia Q., Hu M., Yu M., Shi M., Jiang Z., Guo N. (2008) Fra-1 and Stat3 synergistically regulate activation of human MMP-9 gene. Mol. Immunol. 45, 137–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ben-Zimra M., Koler M., Melamed-Book N., Arensburg J., Payne A. H., Orly J. (2002) Uterine and placental expression of steroidogenic genes during rodent pregnancy. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 187, 223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peng L., Arensburg J., Orly J., Payne A. H. (2002) The murine 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) gene family: a postulated role for 3β-HSD VI during early pregnancy. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 187, 213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fleischmann A., Hafezi F., Elliott C., Remé C. E., Rüther U., Wagner E. F. (2000) Fra-1 replaces c-Fos-dependent functions in mice. Genes Dev. 14, 2695–2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jochum W., David J. P., Elliott C., Wutz A., Plenk H., Jr., Matsuo K., Wagner E. F. (2000) Increased bone formation and osteosclerosis in mice overexpressing the transcription factor Fra-1. Nat. Med. 6, 980–984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eferl R., Hoebertz A., Schilling A. F., Rath M., Karreth F., Kenner L., Amling M., Wagner E. F. (2004) The Fos-related antigen Fra-1 is an activator of bone matrix formation. EMBO J. 23, 2789–2799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mitchell J. A., Lye S. J. (2002) Differential expression of activator protein-1 transcription factors in pregnant rat myometrium. Biol. Reprod. 67, 240–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ramos-Nino M. E., Blumen S. R., Pass H., Mossman B. T. (2007) Fra-1 governs cell migration via modulation of CD44 expression in human mesotheliomas. Mol. Cancer 6, 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ramos-Nino M. E., Scapoli L., Martinelli M., Land S., Mossman B. T. (2003) Microarray analysis and RNA silencing link Fra-1 to CD44 and c-Met expression in mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 63, 3539–3545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kessenbrock K., Plaks V., Werb Z. (2010) Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 141, 52–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Alexander C. M., Hansell E. J., Behrendtsen O., Flannery M. L., Kishnani N. S., Hawkes S. P., Werb Z. (1996) Expression and function of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors at the maternal-embryonic boundary during mouse embryo implantation. Development 122, 1723–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]