Abstract

Background

The FDA requires that red cells must be refrigerated within 8 hours of whole blood collection. Longer storage of whole blood at 22°C before component preparation would have many advantages.

Study Design And Methods

Two methods of holding whole blood for 20 to 24 hours at room temperature were evaluated; i.e., refrigerated plates or a 23°C incubator. After extended whole blood storage, platelet concentrates were prepared from platelet-rich-plasma on day 1 post-donation, and the platelets were stored for 6 more days. On day 7 of platelet storage, blood was drawn from each subject to prepare fresh platelets. The stored and fresh platelets were radiolabeled and transfused into their donor.

Results

Eleven subjects’ whole blood was stored using refrigerated Compocool plates and 10 using an incubator. Post-storage platelet recoveries averaged 47 ± 13% versus 53 ± 11% and survivals averaged 4.6 ± 1.7 days versus 4.7 ± 0.9 days for Compocool versus incubator storage, respectively (p=N.S.). Using all results, post-storage platelet recoveries averaged 75 ± 10% of fresh and survivals 57 ± 13% of fresh; platelet recoveries met FDA guidelines for post-storage platelet viability but not survivals.

Conclusion

Seven-day post-storage platelet viability is comparable when whole blood is stored for 22 ± 2 hour at 22°C using either refrigerated plates or an incubator to maintain temperature prior to preparing platelet concentrates.

Keywords: Platelets, Platelet Concentrates, Platelet Storage

INTRODUCTION

The current Food and Drug administration (FDA) requirement that red cells must be refrigerated within 8 hours of collection means that preparation of platelet concentrates must be initiated within approximately six hours of collection to ensure that platelet processing is completed within the allowed time interval. In contrast, overnight hold of the whole blood at room temperature has long been used in Europe prior to the preparation of buffy-coat platelet concentrates.(1) This method both increases the yield of platelets in platelet concentrates(1,2) and it also may facilitate bacterial ingestion by white cells of any contaminating bacteria prior to leukocyte-filtration, thereby reducing the incidence of transfusion-transmitted sepsis.(3,4) However, the concept that wbcs may remove any contaminating bacteria during an overnight hold of the whole blood remains controversial.(5)

Overnight hold of whole blood prior to component preparation has several logistical and economic advantages for blood centers, in addition to those just described. It would facilitate allowing all collected blood to be processed into platelet concentrates, regardless of the distance of blood collection from the processing center. It would also mean that all component processing could be done on a single shift rather than the multiple shifts now required. Frequent trips from the collection site to the processing center could be eliminated with blood returned on a single trip at the end of the blood drive. As all of the costs of donor recruitment, blood drawing, and testing are already incurred with blood collection, the additional costs related to preparing platelet concentrates from whole blood are minimal compared to collecting platelets by apheresis procedures. Thus, pooled platelet concentrates are much cheaper to obtain an equivalent platelet dose compared to apheresis platelets.

Although we recognize that there may be adverse effects of an overnight hold of the whole blood at 22°C on red cell viability during storage, concentration of labile plasma clotting factors, and the efficiency of filter leukoreduction,(reviewed in References 6, 7) the purpose of our study was to assess the effects of an overnight hold of the whole blood on platelet-rich plasma prepared platelet concentrates. We also wanted to determine whether there would be a difference in the post-storage viability of the platelets with rapid cooling of the whole blood to 22°C using refrigerated plates or whether the same results would be achieved using an incubator to maintain whole blood at 23°C. All of the whole blood units, regardless of the storage method, were stored for 20 to 24 hours before processing into platelet concentrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Twenty-one healthy subjects who met allogeneic blood donor requirements were recruited to participate in these studies, and each subject signed a study consent. The study protocol and consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Experimental Design Of The Storage Studies

Whole blood was stored using Compocool platelets in the Compocool II storage container (these materials supplied courtesy of Fresenius Medical Care of North America, Waltham, MA) The Compocool plate was placed upright in the middle of the Compocool II container, one unit of whole blood was placed next to the plate, and the container was placed on its side to maximize bag-to-plate contact. Alternatively, one unit of blood was placed in a 23°C incubator (Forma Scientific, Inc., Marietta, OH). The units were stored for an average of 22 ± 2 hours before preparing a PRP platelet concentrate.

Whole Blood Cooling Rates

The time for a unit of whole blood to decrease from body temperature (37°C) to 22°C was evaluated using three different methods; i.e., 1) in the Compocool storage container with a Compocool plate, 2) 23°C incubator, or 3) just placing a unit of blood on a test tube rack in our research laboratory. A temperature probe (Temptale 4, Sensitech, Beverly, MA) with an attached recorder was placed inside each whole blood unit that had been warmed to 37°C to determine the rate of decrease in temperature over time.

Preparation Of Stored Platelets

Each subject donated 500 mls of blood into a Terumo Teruflex® blood bag with Diversion Sampling Arm (BB* AGQ456A2) (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) using routine whole blood donation procedures. The primary blood collection bag contains 70 mls of Citrate-Phosphate-Dextrose as the anticoagulant and adenine as a red cell preservative. This bag system is used routinely at our blood center, and the platelet storage bag is made of polyvinyl chloride with citrate plasticizer. A subject participated in each study only once. All stored platelets met the bag manufacturer’s guidelines for platelet concentration, total platelet count, and storage volume.

Following an overnight hold of each bag using its assigned device, the whole blood was centrifuged at 2300g for 4½ minutes (start to finish), with 5 minutes of brake time to prepare platelet-rich plasma (PRP) which was then transferred to the attached platelet storage bag. The PRP was centrifuged at 3000g for 6 minutes to prepare a platelet concentrate. The platelet concentrates were not leukoreduced. An average of 63 ± 7 mls of plasma was left with the platelet concentrates, and the rest of the plasma was transferred to a satellite bag using a plasma expressor. The platelet concentrates were allowed to rest undisturbed at room temperature for 1½ hours before placing them in a Helmer Incubator Model PF96 (Helmer Corporation, Fort Wayne, IN) for re-suspension and continuous agitation at 70 cycles/minute during storage at 22 ± 2°C for 6 days. The platelets were maintained for 1 day within the collected whole blood unit and for an additional 6 days as a platelet concentrate, for a total in vitro storage time of 7 days.

Preparation Of Fresh Platelets

Fresh platelets were prepared from a 43 ml sample of whole blood drawn from the subject into 9 mls of Acid-Citrate-Dextrose (ACD-A) anticoagulant on day 7 post-whole blood donation. The whole blood was transferred into two 50 ml Becton Dickson conical screw-top tubes (Franklin Lakes, NJ) and rested for 30 minutes. The tubes were centrifuged at 200g for 15 minutes to prepare PRP, and the PRP from each tube was transferred to another conical tube. ACD-A equal to 15% of the PRP volume was added, the PRP was centrifuged at 2000g for 15 minutes. The ACD added was calculated to give a pH of 6.5 to allow immediate platelet re-suspension.

In Vitro Platelet Assays

Platelet counts were performed on the day following collection and after storage using an ABX Hematology Analyzer (ABX Diagnostics, Irvine, CA). At the end of storage, glucose concentration, blood gases, pH at 22°C, extent of shape change (ESC),(8) hypotonic shock response (HSR),(8) Annexin V binding, morphology score,(9) and mean platelet volumes (MPV) were determined. HSR and ESC were performed using a chrono-log whole blood aggregometer (Chrono-Log Model 500-Ca, Havertown, PA) to measure platelet responses photometrically. Platelets were stained for Annexin using invitrogen Annexin 5 alexa fluor, (emits in FL1 channel) and a FACSCAN (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) was used to detect Annexin V binding. Chicken red cells were used to set the flow cytometer to 103 in the FL1 channel. One percent paraformaldehyde-fixed platelets were used as the positive control. Test platelet samples were run in duplicate, and any cell greater than fl1=16 was counted as positive (only cells within platelet gate r1 were considered).

Platelet Radiolabeling

A 43 ml aliquot of the stored platelet concentrate was radiolabeled with either 111In or 51Cr, and the opposite label was used to radiolabel the donor’s fresh platelets. Radiolabeling was performed by established techniques, and platelet recoveries and survivals were corrected for elution of the label and for residual radioactivity at day 10 post-transfusion that was considered due to contaminating radiolabeled red cells.(10) The radiolabeled platelet recoveries and survivals were calculated using the COST program’s multiple hit model.(11) Blood samples were drawn from the donor before, at 2 hours, and on days 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10 post-infusion. The radiolabels used for the fresh and stored platelets were rotated with each sequential subject enrolled in a study so that, at the end of each storage experiment, equal numbers of the subjects’ fresh and stored platelets were labeled with each isotope.

Statistical Methods

Comparisons of means of in vivo and in vitro variables grouped by hold method (Compocool plate or incubator) were made using t-tests with a Bonferroni adjustment for the number of in vivo and in vitro variables evaluated. Evaluation of stored platelet recovery and survival with respect to the FDA criteria were made using the method of Dumont.(12)

RESULTS

Whole Blood Cooling Rates

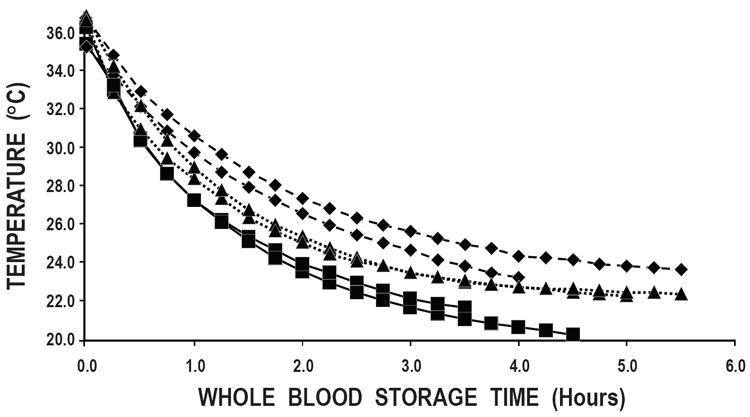

It took approximately 3 hours using the Compocool plate for the temperature of the whole blood units to decrease to 22°C, approximately 3½ hours to decrease to 23°C in the incubator, and, by 3½ to 4 hours, the room temperature units were still at about 23°C to 25°C, which may have been the temperature of the room (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the lowest temperature we could achieve with our incubator was 23°C.

Figure 1. Whole Blood Cooling Rates.

Two individual units of whole blood were warmed to body temperature (37°C) and allowed to cool by three different methods: 1) in the Compocool storage container with a Compocool plate (■); 2) in a 23°C incubator (▲); and 3) on a test tube rack in our research laboratory (◆).

In Vivo Radiolabeled Autologous Platelet Recoveries and Survivals

There were 11 healthy subjects whose blood was stored for 22 ± 2 hours using Compocool plates before preparation of a PRP platelet concentrate and 10 healthy subjects whose blood was stored for similar times in a 23°C incubator. Seven-day stored platelet recoveries averaged 47 ± 13% versus 53 ± 11%, and survivals averaged 4.6 ± 1.7 days versus 4.7 ± 0.9 days, respectively, for the subjects whose whole blood was stored using Compocool plates versus those stored in a 23°C incubator (Table 1). The Compocool and incubator stored platelet concentrates were evaluated with respect to the FDA’s criteria for post-storage platelet viability using Dumont’s method.(12) Stored platelet recoveries as a percent of fresh averaged 74 ± 11% and 79 ± 11% for the Compocool and incubator methods, respectively. The 95% lower confidence limits for percent of fresh recoveries for the Compocool and incubator stored platelets were 66% and 71%, respectively, which met the FDA criterion of being 66% of fresh.(13) Stored platelet survivals as a percent of fresh averaged 57 ± 14% and 58 ± 12% for the Compocool and incubator methods, respectively, and both 95% lower confidence limits for percent of fresh survivals were less than the FDA criterion of 58% (48% and 49%, respectively). There were no significant differences between any of these results.

TABLE 1.

EFFECTS OF COMPOCOOL PLATE VERSUS INCUBATOR STORAGE OF WHOLE BLOOD AT 22°C FOR 22 ± 2 HOURS ON 7-DAY STORED PLATELET VIABILITY

| N | Maintain 22°C Whole Blood Storage | PLATELET RECOVERIES (%) | Stored Platelet Recoveries (% of Fresh) | PLATELET SURVIVALS (Days) | Stored Platelet Survivals (% of Fresh) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | Stored | Fresh | Stored | ||||

| 11 | Compocool Plate | 63 ± 14 | 47± 13 | 74 ± 11 (66%)* | 8.0 ± 1.5 | 4.6 ± 1.7 | 57 ± 14 (48%)* |

| 10 | Incubator | 67 ± 12 | 53 ± 11 | 79 ± 11 (71%)* | 8.2 ± 1.4 | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 58 ± 12 (49%)* |

Data are reported as the average ±1 S.D.

No significant differences between any of the measurements.

Numbers in parentheses are the 95% lower confidence limits of the data.

In Vitro Platelet Assays

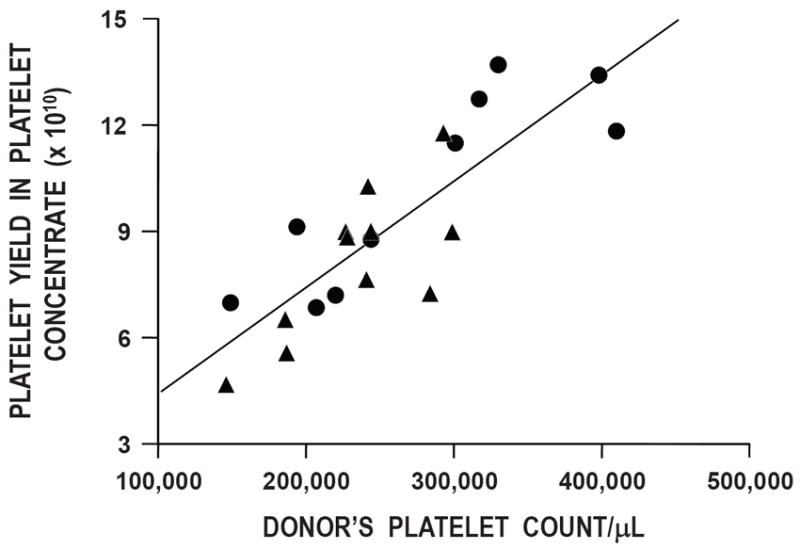

The results of the in vitro assays of the platelet concentrates prepared from the whole blood stored using the Compocool plates versus incubator storage are shown in Table 2. Platelet counts of the platelet concentrates on day 7 were higher for the incubator stored whole blood prepared platelet concentrates versus the platelet concentrates prepared from the units stored using Compocool plates, but the difference did not attain statistical signficance (10.21 ± 2.73 × 1010 versus 8.11 ± 2.07 × 1010, respectively, p>0.20). However, the donors’ platelet counts were higher for the incubator stored units compared to the Compocool stored units; i.e., 277,000 ± 88,000/μl versus 234,000 ± 48,000/μl. When the yield of the donor’s platelet concentrate was plotted against their platelet count, the data show that the platelet concentrate yields are consistent with the donor’s platelet count (Figure 2). There were no significant differences between any of the in vitro assay results based on how the whole blood units were stored.

TABLE 2.

IN VITRO ASSAYS OF PLATELET CONCENTRATES PREPARED FROM WHOLE BLOOD STORED USING COMPOCOOL PLATES VERSUS 23°C INCUBATOR

| Whole Blood Storage At 22°C |

N | Donor’s Platelet Count/μl |

Platelet Yield(× 1010) | Morphology Score |

Annexin V Binding (% surface expression) |

ESC (%) |

HSR (%) |

MPV (fL) |

pH (22°C) |

PCO2 (mmHg) |

PO2 (mmHg) |

HCO3 (mmol/L) |

Glucose (mgm/dL) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 7 | |||||||||||||

| Compocool Plate | 11 | 234,000 ± 48,000 | 7.86 ± 1.98 | 8.11 ± 2.07 | 298 ± 36 | 15 ± 10 | 11 ± 7 | 29 ± 10 | 8 ± 0.3 | 7.2 ± 0.1 | 29 ± 6 | 132 ± 25 | 12 ± 2 | 265 ± 28 |

| Incubator | 10 | 277,000 ± 88,000 | 9.77 ± 2.48 | 10.21 ±2.73 | 295 ± 44 | 17 ± 7 | 17 ± 4 | 39 ± 14 | 8 ± 0.3 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 32 ± 6 | 122 ± 23 | 11 ± 1 | 246 ± 37 |

All in vitro assays were performed on Day 7.

ESC = Extent Of Shape Change.

HSR = Hypotonic Shock Response.

MPV = Mean Platelet Volume.

Figure 2. Donor’s Platelet Count Versus Platelet Count Of The Platelet Concentrate On Day 7 Post-Storage.

There is a direct relationship between the donor’s platelet count and the platelet yield in the concentrate on day 7 (r2=0.70) (p<0.001). Data for whole blood units stored with the Compocool plates are shown as triangles (▲) and in the incubator as circles (●).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated three important findings: 1) the platelet yield in platelet concentrates prepared from whole blood held for 22 ± 2 hours at room temperature (22 ± 2°C) is well above FDA requirements of 5.5 × 1010 platelets/concentrate (i.e., overall average was 8.78 ± 2.37 × 1010, n=21); 2) after storing the platelets for 7 days, platelet recoveries averaged 49 ± 12% (76 ± 11% of fresh recoveries), and platelet survivals averaged 4.6 ± 1.3 days (57 ± 13% of fresh survivals) -- platelet recoveries but not platelet survivals met FDA requirements for post-storage platelet quality (the lower 95% confidence limit for stored platelet recoveries should be 66% of the same donor’s fresh recoveries and stored platelet survivals should be 58% of fresh);(13) and 3) the method of storing the whole blood to maintain room temperature prior to platelet concentrate preparation using either Compocool plates or storing the whole blood in an incubator does not affect any in vivo or in vitro platelet parameter after 7 days of storage. The sample sizes of 10 and 11 units of whole blood to evaluate differences in platelet quality between the incubator and Compocool methods of storing the whole blood, respectively, were based on the usual FDA requirement that a single laboratory perform 10 normal volunteer in vivo autologous radiolabeled platelet recovery and survival measurements to assess post-storage platelet viability. Given our sample sizes, we had 76% power to detect a 15% difference in platelet recoveries and 66% power to detect a 1.5 day difference in platelet survivals between the two methods of whole blood storage, if such existed. Larger sample sizes to increase the power to detect differences between the storage methods would have required recruiting another laboratory.

Our results demonstrating no difference in measures of platelet quantity or quality of platelet-rich-plasma prepared platelet concentrates using Compocool plates or a 23°C incubator to maintain temperature during an overnight hold of whole blood are consistent with European studies. Using a variety of methods of preparing buffy-coat platelets from whole blood units, (14-15) “n vitro” platelet assays of buffy coat prepared platelets showed no differences, but, unfortunately, “in vivo” measures of platelet viability were not performed. In addition, in the European studies, no differences were seen in in vitro measures of rbc quality or concentration of plasma clotting factors whether whole blood units were stored with or without active cooling.

Our data are also consistent with a prior study that evaluated the effects of the whole blood storage times in a paired study in 10 healthy volunteers who donated a unit of whole blood on two occasions.(16) One whole blood unit was held at 22°C for 8 hours, and the other unit was held for 24 hours before preparation of a PRP platelet concentrate. After storage for 5 days, post-transfusion platelet recoveries averaged 55% and 57% and survivals 6.6 and 5.8 days for whole blood units stored for 8 and 24 hours, respectively, before preparation of PRP platelet concentrates.

One problem with our study is that an incubator was used to maintain 22°C rather than storing the platelets in a temperature-controlled room as would be done at a blood center. We used a temperature-controlled incubator as we wanted to be able to maintain a constant temperature to get valid results, and a temperature-controlled room was not available. However, it is likely that the same results as obtained in our study using an incubator would be achieved in a temperature-controlled room.

In summary, holding whole blood at 22 ± 2°C for up to 24 hours prior to preparation of PRP platelet concentrates provides platelet yields and platelets that can be stored for 7 days and still meet FDA guidelines for post-storage platelet recoveries but not platelet survivals. Seven-day post-storage viability data demonstrating that only platelet recoveries but not platelet survivals meet FDA standards is similar to our prior results with extended stored PRP platelet concentrates.(17) However, in a separate paired study where whole blood units collected from the same donors on two separate occasions were held overnight at 22°C using Compocool plates, neither post-storage platelet recoveries nor survivals of 7-day stored PRP or buffy-coat prepared platelet concentrates were able to meet FDA post-storage platelet viability criteria.(18) Furthermore, rapid cooling of the whole blood to room temperature is not required to meet FDA quantity and quality platelet standards. Eliminating the need to use cooling plates would represent a substantial cost-savings to blood centers.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the excellent administrative support provided by Ginny Knight in the preparation of this manuscript.

This research study was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (1 P50 HL081015).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors certify that they have no affiliation with or financial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Disclaimers / Disclosures: S.J. Slichter: None

J. Corson: None

M.K. Jones: None

T. Christoffel: None

E. Pellham: None

D. Bolgiano: None

References

- 1.Pietersz RN, de Korte D, Reesink HW, Dekker WJ, van den Ende A, Loose JA. Storage of whole blood for up to 24 hours at ambient temperature prior to component preparation. Vox Sang. 1989;56:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1989.tb02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Meer PF, de Wildt-Eggen J. The effect of whole-blood storage time on the number of white cells and platelets in whole blood and in white cell-reduced red cells. Transfusion. 2006;46:589–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Högman CF, Gong J, Eriksson L, Hambraeus A, Johansson CS. White cells protect donor blood against bacterial contamination. Transfusion. 1991;31:620–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31791368338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanz C, Pereira A, Vila J, Faundez A-I, Gomez J, Ordinas A. Growth of bacteria in platelet concentrates obtained from whole blood stored for 16 hours at 22°C before component preparation. Transfusion. 1997;37:251–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37397240204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heal JM, Cohen HJ. Do white cells in stored blood components reduce the likelihood of posttransfusion bacterial sepsis? (Editorial) Transfusion. 1991;31:581–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31791368331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thibault L, Beausejour A, de Grandmont MJ, Lemieux R, Leblanc J-F. Characterization of blood components prepared from whole-blood donations after a 24-hour hold with the platelet-rich plasma method. Transfusion. 2006;46:1291–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas S. Ambient overnight hold of whole blood prior to the manufacture of blood components. Transfusion Medicine. 2010;203:361–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2010.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holme S, Moroff G, Murphy S. A multi-laboratory evaluation of in vitro platelet assays: The tests for extent of shape change and response to hypotonic chock. Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion Working Party of the International Society of Blood Transfusion. Transfusion. 1998;38:31–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.38198141495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunicki TJ, Tuccelli M, Becker GA, Aster RH. A study of variables affecting the quality of platelets stored at “room temperature”. Transfusion. 1975;15:414–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1975.15576082215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative. Platelet radiolabeling procedure. Transfusion. 2006;46(Suppl 3):59S–66S. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lötter MG, Rabe WL, Van Zyl JM, Heyns AD, Wessels P, Kotze HF, Minnaar PC. A computer program in compiled BASIC for the IBM personal computer to calculate the mean platelet survival time with the multiple hit and weighted mean methods. Comput Biol Med. 1988;18:305–15. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(88)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumont LT. Analysis and reporting of platelet kinetic studies. Transfusion. 2006;46(Suppl):67S–73S. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vostal JG. Efficacy evaluation of current and future platelet transfusion products. J Trauma. 2006;(6 Suppl):S78–82. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000199921.40502.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilsher C, Garwood M, Sutherland J, Turner C, Cardigan R. The effect of storing whole blood at 22°C for up to 24 hours with and without rapid cooling on the quality of red cell concentrates and fresh-frozen plasma. Transfusion. 2008;48:2338–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas S, Beard M, Garwood M, Callaert M, van Waeg G, Cardigan R. Blood components produced from whole blood using the Atreus processing system. Transfusion. 2008;48:2515–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moroff G, AuBuchon JP, Pickard C, Whitley PH, Heaton WA, Holme S. Evaluation of the properties of components prepared and stored after holding of whole blood units for 8 and 24 hours at ambient temperature. Transfusion. 2011;51(Suppl 1):7S–14S. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slichter SJ, Bolgiano D, Corson J, Jones MK, Christoffel T. Extended storage of platelet-rich plasma prepared platelet concentrates in plasma or Plasmalyte. Transfusion. 2010;50:2199–2209. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumont LJ, Dumont DF, Unger ZM, Siegel A, Szczepiorkowski ZM, Corson JS, Jones MK, Christoffel T, Pellham E, Bailey SL, Slichter SJ for the BEST Collaborative. A randomized controlled trial comparing autologous radiolabeled in vivo platelet recoveries and survivals of 7-day stored platelet-rich plasma and buffy coat platelets from the same subjects. Transfusion. 2011;51(6):1241–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]