Abstract

Hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate has become an important diagnostic tracer of normal and aberrant cellular metabolism for in vitro and in vivo NMR spectroscopy (MRS) and imaging (MRI). In pursuit of achieving high NMR signal enhancements in dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) experiments, we have performed an extensive investigation of the influence of Gd3+ doping, a parameter previously reported to improve hyperpolarized NMR signals, on the DNP of this compound. [1-13C]Pyruvate samples were doped with varying amounts of Gd3+ and fixed optimal concentrations of free radical polarizing agents commonly used in fast dissolution DNP: trityl OX063 (15 mM), 4-oxo-TEMPO (40 mM), and BDPA (40 mM). In general, we have observed three regions of interest, namely: (i) a monotonic increase in DNP-enhanced nuclear polarization Pdnp upon increasing the Gd3+ concentration until a certain threshold concentration c1 (1–2 mM) is reached, (ii) a region of roughly constant maximum P from c1 until a concentration threshold c2 (4–5 mM), and (iii) a monotonic decrease in Pdnp at Gd3+ concentration c > c2. Of the three free radical polarizing agents used, trityl OX063 gave the best response to Gd3+ doping with a 300 % increase in the solid-state nuclear polarization whereas addition of the optimum Gd3+ concentration on BDPA and 4-oxo-TEMPO-doped samples only yielded a relatively modest 5–20 % increase in the base DNP-enhanced polarization. The increase in Pdnp due to Gd3+ doping is ascribed to the decrease in the electronic spin-lattice relaxation T1e of the free radical electrons which plays a role in achieving lower spin temperature Ts of the nuclear Zeeman system. These results are discussed qualitatively in terms of the spin temperature model of DNP.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the pivotal invention of the fast dissolution technique in dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) by Ardenkjaer-Larsen and co-workers in 2003,1 DNP has attracted renewed and increasing interest especially in chemistry and biomedical NMR spectroscopy and imaging. DNP, a technology that has been used in the production of polarized targets for nuclear and particle physics experiments since the 1950s,2–5 uses microwave irradiation to transfer high electronic polarization to the target nuclear spins (e.g. protons and deuterons) with optimal results at low temperature (1 K or less) and moderate magnetic field (> 1 T). While polarization transfer occurs at cryogenic temperatures, the incorporation of a fast dissolution device1 that rapidly dissolves the frozen polarized sample allows the production of injectable liquids at physiological temperatures containing highly polarized nuclei of biological interest. Since the hyperpolarized state decays by spin-lattice T1 relaxation, an important requirement for successful dissolution DNP experiments is that the nucleus of interest should have sufficiently long T1 (typically at least 10 s) to preserve some or preferably, most of the nuclear spin polarization during the dissolution transfer from the polarizer to an NMR magnet/imaging system, a process that normally takes 5–10 s. Notable examples of biomedical applications of this technology include pH mapping in tumors using hyperpolarized 13C-bicarbonate,6 grading the aggressiveness of prostate cancer with hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate,7 and in general, real-time monitoring of in vitro and in vivo biochemical/metabolic activities8–30 via hyperpolarized 13C NMR spectroscopy (MRS) and imaging (MRI). Other long T1 nuclei that have been polarized via the fast dissolution DNP method include 15N,31 6Li,32 89Y,33–35 and 107,109Ag,36 among others.

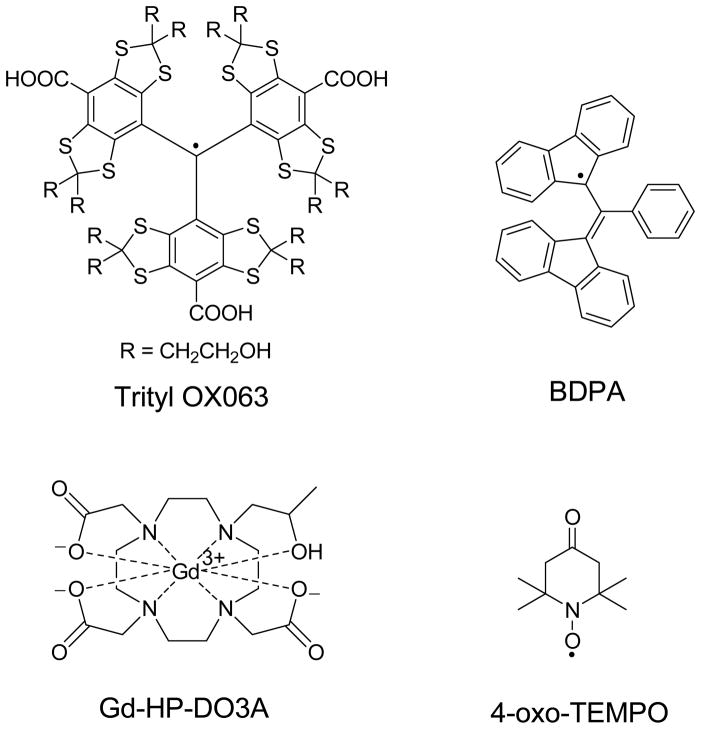

Free radicals commonly used as polarizing agents in DNP include carbon centered free radicals such as trityl OX063 and BDPA and nitroxyls (Chart 1). The ESR properties of the free radical are crucial parameters in DNP. In this work, the results are qualitatively discussed in the context of the thermodynamic model of DNP involving the interaction of three thermal baths: electron Zeeman system, electron dipolar or spin-spin interaction system, and the nuclear Zeeman system.2–5 Thermal mixing, which is the expected predominant DNP mechanism in our experiments, occurs when the ESR linewidth D of the free radical is greater than or comparable to the nuclear Larmor frequency.2–5 In this regime, microwave irradiation dynamically cools the electron spin-spin interaction reservoir that has an energy matching the nuclear Zeeman reservoir, and there is thermal contact between the two reservoirs thereby resulting in equal spin temperature Ts for both systems.2–5 The nuclear polarization levels achieved in DNP can be maximized by using appropriate glassing agents,35,37 free radicals with narrow ESR linewidths,35,38 and lower polarizer operating temperatures.39 Another factor that can improve the maximum polarization (minimum Ts for nuclear spins) in DNP is the use of Gd3+ which has been described in earlier experiments on 13C samples doped with trityl OX063.40,41 Consequently, several hyperpolarized 13C MRS and MRI experiments have reported the routine use of trace amounts (1–2 mM) of Gd3+ compounds and complexes such as GdCl3, ProHance®, Magnevist®, Dotarem®, and 3-Gd® in trityl-doped 13C samples to dramatically improve the liquid-state NMR signal enhancements after dissolution.6,17–30,42–44 The impact of Gd3+ on trityl-based polarizing agents has only been investigated over a limited concentration range (0–2 mM). Here, we present our studies on the influence of Gd3+ on the DNP of [1-13C]pyruvate samples doped with three different free radical polarizing agents: trityl OX063, BDPA, and 4-oxo-TEMPO (Chart 1). In this work, the effect of Gd3+ (hereafter refers to the Gd-HP-DO3A complex) on the solid-state nuclear polarization Pdnp and spin-lattice relaxation T1 of [1-13C]pyruvate was investigated over a wider concentration range (up to 8 mM) with each radical.

Chart 1.

The free radical polarizing agents and Gd3+ complex used in this work.

2. EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Materials

The free radical polarizing agents used in this work were obtained from commercial sources: (i) tris{8-carboxyl-2,2,6,6-benzo(1,2-d:5-d)-bis(1,3)dithiole-4-yl}methyl sodium salt (trityl OX063) [Oxford Instruments Molecular Biotools], (ii) 1,3-bisdiphenylene-2-phenylallyl (BDPA) [Sigma-Aldrich], and (iii) 4-oxo-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) [Sigma-Aldrich]. [1-13C]pyruvic acid and [1-13C]sodium pyruvate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. ProHance® (Bracco Diagnostics, New Jersey) was obtained as 0.5 M Gd-HP-DO3A solution in water. All chemicals and glassing solvents (glycerol, sulfolane) used in this study were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification.

Trityl-doped samples

[1-13C]sodium pyruvate solution (1.4 M) in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water glassing matrix was prepared and doped with trityl OX063 (15 mM). Small aliquots of these samples were prepared with different concentrations of Gd3+ (0–8 mM ProHance).

BDPA-doped samples

BDPA was prepared in sulfolane via sonication (80 mM) and mixed with equal amount (volume) of [1-13C]pyruvic acid as previously described.45 The final concentration of BDPA in the mixture was 40 mM. Small aliquots were prepared with different concentrations of Gd3+ (0–8 mM ProHance).

TEMPO-doped samples

[1-13C]sodium pyruvate (1.4 M) in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water glassing matrix was prepared and doped with 4-oxo-TEMPO (40 mM). Small aliquots were prepared with different concentrations of Gd3+ (0–8 mM ProHance).

Microwave frequency sweep

The samples (100 μL aliquots) were polarized in a HyperSense® DNP (Oxford Instruments, England) for 3 minutes at each different microwave frequency and the NMR signal intensity was recorded with the built-in solid state NMR spectrometer. A series of hard rf excitation pulses was applied to destroy the residual magnetization before starting the polarization of the sample at the next microwave frequency. In addition, the 13C microwave DNP spectra with longer microwave irradiation time (1 hour) of trityl-doped 13C pyruvate samples were also recorded (see the Supporting Information) for comparison.

Measurement of solid-state nuclear polarization

The DNP-enhanced nuclear polarization of the frozen sample Pdnp was calculated by multiplying the NMR signal enhancement ε (ratio of integrated NMR intensity of the hyperpolarized NMR signal over the thermal NMR signal of the sample) with the calculated thermal nuclear polarization Pthermal of the sample at cryogenic conditions. The calculated 13C thermal polarization at 3.35 T and 1.4 K is Pthermal=6.147×10−2% using the Boltzmann distribution equation for an ensemble of 13C nuclear spins. The NMR spectra were acquired using a Varian VNMRS spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Measurement of solid-state nuclear spin-lattice relaxation time T1

100 μL aliquots were polarized at 3.35 T and 1.4 K in the HyperSense until they reached their corresponding maximum polarizations. The microwave source was then turned off and the decay of the hyperpolarized NMR signal of the sample inside the polarizer (3.35 T, 1.4 K) was monitored by applying a 1.5-degree rf excitation pulse (see pulsewidth calibration in the Supporting Information) every 300 s using the Varian VNMRS spectrometer. The decay curves were fitted to an equation accounting for the magnetization decay due to T1 decay and rf excitation.46 Values of 13C T1 of the sample in the frozen state were extracted from these fits.

Data Analyses

The NMR data were acquired using a Varian VNMR spectrometer and the spectra were processed using ACDLABS ver. 12 software (Advanced Chemistry Development, Inc., Toronto, Canada). The graphs, fits, and data analyses were done using Igor Pro ver. 6 (Wavemetrics Inc., Portland, OR).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. DNP of trityl-doped [1-13C] sodium pyruvate

A number of experiments1,35,41,47 have shown that the DNP of low-γ nuclei (e.g. 13C, 89Y) doped with the free radical trityl OX063 proceeds predominantly via thermal mixing. The optimum concentration of trityl OX063 in 13C samples that gives the maximum solid-state polarization in a reasonable amount of microwave irradiation time has been reported to be ~15 mM41,48 (see also the Supporting Information). Trityl OX063 (Chart 1) has an ESR linewidth D = 2.24 mT,41 which is among the narrowest of the free radicals used for fast dissolution DNP-NMR. In the thermal mixing regime, trityl OX063 is an efficient DNP polarizing agent for low-γ nuclei such as 13C because its narrow D translates to lower electron heat capacity yielding a lower spin temperature for the electron spin-spin interaction reservoir which is in thermal contact with the nuclear Zeeman system.2–5 This results in lower spin temperature of the nuclear Zeeman system/high nuclear polarization Pdnp.

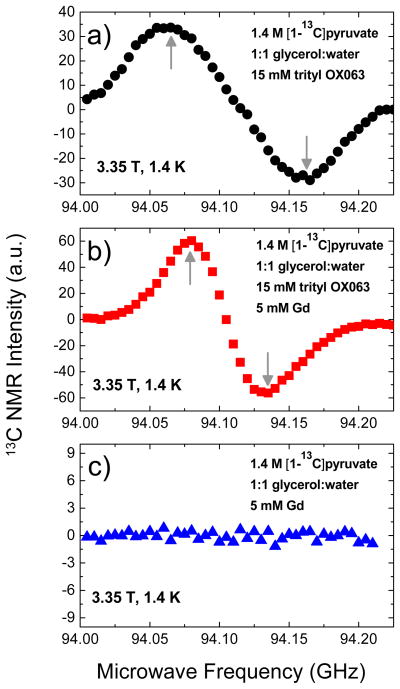

Figure 1 shows the microwave DNP spectra of 1.4 M [1-13C]sodium pyruvate in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water glassing matrix doped with a) 15 mM trityl OX063, b) 15 mM trityl OX063 plus 5 mM Gd3+, and c) 5 mM Gd3+. The microwave DNP spectra shown here were plotted by recording the 13C NMR intensity every after three minutes of microwave irradiation of the sample at different microwave frequencies. This relatively short irradiation time would give the approximate locations of the optimum DNP irradiation frequencies, namely the positive polarization peak P(+) and negative polarization peak P(−). A comparison with the microwave DNP spectra of 13C samples taken at a longer microwave irradiation time (1 hour; see the Supporting Information) reveals almost the same locations of P(+) and P(−), with a slight offset of 5–10 MHz down in frequency relative to the data taken with a 3-minute irradiation time shown in Figure 1. Theoretically, the longer irradiation times would give values closer to the actual locations of the optimum polarization peaks. For practical purposes, however, the shorter irradiation times could show the approximate locations of P(+) and P(−). Nevertheless, this slight offset only has a relatively minor effect on the polarization buildup results considering the broadness of the polarization peaks.

Figure 1.

Microwave DNP spectra of 100 μL samples containing 1.4 M [1-13C]sodium pyruvate in 1:1 glycerol:water glassing matrix doped with a) 15 mM trityl, b) 15 mM trityl and 5 mM Gd3+, and c) 5 mM Gd3+. These data were taken in the HyperSense at 3.35 T and 1.4 K using a 100 mW microwave source. The up and down arrows indicate the approximate locations of the positive and negative polarization peaks, respectively.

The addition of Gd3+ to trityl-doped [1-13C]sodium pyruvate samples leads to two main effects: (1) a decrease in the separation distance between polarization peaks P(+) and P(−) as shown in Figure 1b and (2) an increase in the NMR intensity. Since it was shown elsewhere49 that the polarization buildup time constant τbu tends to become longer further out the tails of the microwave DNP spectrum, a question arises on whether or not the first effect is due to polarization buildup kinetic effect attributed to a relatively short irradiation time (3 minutes). The 13C microwave spectrum of the 13C pyruvate sample doped with 4 mM Gd3+ measured at the longer irradiation time (1 hour; see the Supporting Information) shows the same narrowing of the polarization peak separation distance. Currently, the exact cause for the decrease in the separation between P(+) and P(−) is not clear. For the second effect, the improvement in the DNP-enhanced NMR intensity in the presence of Gd3+ has been observed previously40,41 and is ascribed to the shortening of the electronic spin-lattice relaxation time T1e.

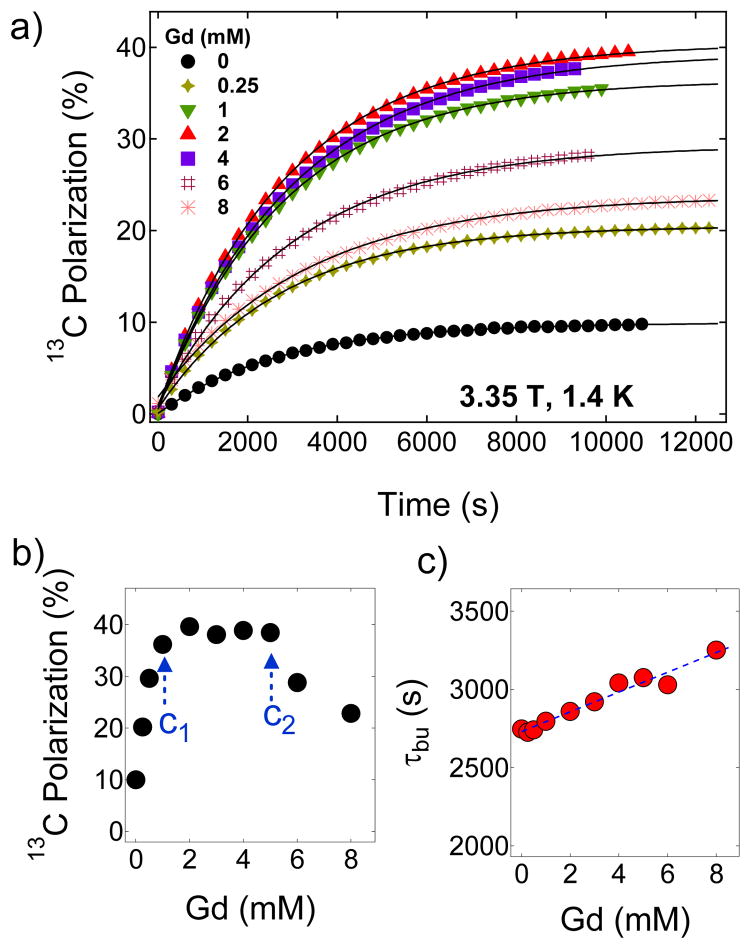

Figure 2.

a) Representative polarization buildup curves of 1.4 M [1-13C]pyruvate in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water glassing matrix doped with 15 mM trityl OX063 and mixed with different concentrations of Gd3+. These curves were taken by irradiating the samples at 94.072 GHz with a 100 mW microwave source at 3.35 T and 1.4 K. The solid lines are fits to a mono-exponential buildup equation. b) The maximum 13C nuclear polarization of [1-13C]pyruvate sample as a function of Gd3+ concentration at 3.35 T and 1.4 K. c) Polarization buildup time constant τbu versus Gd3+ concentration derived by fitting the polarization buildup curves with a single-exponential buildup equation.

To eliminate the possibility that the paramagnetic Gd3+ itself acts as polarizing agent, we also performed a microwave sweep on [1-13C] sodium pyruvate samples doped with 5 mM Gd3+ only as displayed in Figure 1c and found no indication that Gd3+ acts as polarizing agent in this microwave frequency window. This is expected because the frequency range the HyperSense is capable of is centered on g≈2 organic free radicals such as trityl OX063 and BDPA. The ESR resonance of g≠2 metal ions such as Gd3+ is located further upfield (lower microwave frequency in a fixed field) that is outside the microwave frequency window of the HyperSense. It should be noted however, that Gd3+ compounds such as GdCl3 and the Gd3+ complex of 1,4,7,10-teraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA) have been used as DNP polarizing agents for protons at 70–80 K where, neglecting the broad overlapping resonances of the higher order transitions, the narrow ESR linewidth of the central transition ±½→∓½ of the S=7/2 Gd3+ can transfer polarization to the proton spins via the solid effect.50,51 However, at low temperature close to 1 K, the electron polarization is higher and most of the electron spins reside in the Zeeman ground state (ms=7/2) and thus the transitions from this level form a broad signal which dominates the ESR spectrum.52 In addition to the fact that the Gd3+ ESR resonance is located far from that of the trityl OX063, the very broad ESR line of Gd3+ due to the higher-order transitions would be ineffective for DNP via thermal mixing. Therefore, the Gd3+ in this system does not act as polarizing agent in this case but rather aids the free radical electrons in achieving more efficient transfer of polarization to the nuclear spins.

So far, the effect of Gd3+ has not been investigated systematically over a wide concentration range. Therefore, we have performed DNP experiments with trityl-doped (15 mM) [1-13C] sodium pyruvate samples in which the concentration of Gd3+ was varied from 0 to 8 mM. The samples were irradiated at 94.072 GHz near the positive polarization peaks of Gd-free and Gd-doped 13C samples. Figure 2a shows the representative 13C polarization buildup curves at 3.35 T and 1.4 K of samples containing different concentrations of Gd3+. Figure 2b provides a summary that highlights the three Gd3+ concentration regions of interest on the basis of its effect on solid-state nuclear polarization of [1-13C]pyruvate. The maximum 13C polarization in the absence of Gd3+ was 9.6 % after microwave irradiation of the sample for 3–4 hours. The 13C nuclear polarization increases nearly linearly as Gd3+ is increased from 0–2 mM then plateaus between 2–5 mM at a polarization level of ~40 % as shown in Figure 2b, and then declines at Gd3+ concentration c >5 mM. In comparison, a previous DNP study on neat [1-13C]pyruvic acid doped 15 mM trityl OX063 polarized at 3.35 T and 1.2 K yielded a 13C nuclear polarization improvement from ~20 % to ~40 % with the addition of 1.5 mM GdCl3.41 In Figure 2c, the polarization buildup time constant τbu monotonically increases with Gd3+ doping over this same concentration range. In a simple scenario, a shorter electronic T1e would mean that the free radical electron would polarize nuclear spins faster, thus τbu should decrease. This result however suggests that the polarization buildup kinetics in this case is more than just fast electronic relaxation and nuclear spin diffusion.

We interpret the increase in nuclear polarization with Gd3+ doping using the spin temperature model of DNP to explain the increase in the nuclear polarization with Gd3+ doping. Theoretically, the upper limit of DNP-enhanced nuclear polarization Pdnp,max for an ensemble of nuclei with spin I=1/2 is given by:53,54

| (1) |

where βL= Ħ/kBTL (Ħ, kB, TL are the Planck’s constant divided by 2π, the Boltzmann constant, and lattice temperature, respectively), ωe and ωI are the electron and nuclear Larmor frequencies, respectively, D is the ESR linewidth, η=T1Z/T1D (T1Z, T1D are the electronic Zeeman and dipolar spin-lattice relaxation times, respectively), and f is the so-called “leakage factor” of nuclear relaxation. Equation 1 can be simplified to Pdnp,max=tanh(μB/kBTs,min) where the minimum spin temperature is expressed as .35 These equations point out that the key to achieving high nuclear polarization levels under the thermal mixing DNP mechanism is to minimize the spin temperature Ts of the electron spin-spin interaction reservoir and in this model, lower Ts can be achieved by decreasing the values of these parameters: D, TL, η, and f and/or increasing the magnetic field (higher ωe). Since TL and B are determined by the physical limits of the DNP hardware, the parameters that can be influenced by Gd3+ doping can be narrowed to D, η, and f. It is assumed that Gd3+ doping has a minimal effect on the ESR linewidth D over the concentration range examined here (0 to 8 mM). This leaves the factor as the composite parameter that effectively changes with Gd3+ doping.

Previous ESR studies41 on trityl-doped samples (15 mM trityl OX063 in neat [1-13C] pyruvic acid at 3.35 T and 1.2 K) have shown that the electronic Zeeman T1Z of the free radical paramagnetic electron was reduced from approximately 1.2 s to 0.3 s with the addition of 1 mM GdCl3 while the nuclear longitudinal relaxation T1 seemingly remained unaffected at this GdCl3 concentration. This result implies that the parameter η, in particular the electronic Zeeman relaxation time T1Z, is reduced in the presence of Gd3+ thereby lowering the spin temperature of the electron spin-spin interaction reservoir. A thermodynamic view of this case is that the rate of cooling of the electron Zeeman system is faster than the rate of heating of the electron dipolar system.55

Let us first consider the Gd3+ concentration range of 0 to 1 mM where Pdnp monotonically rises. As mentioned before, the nuclear T1’s in this region are barely affected as the Gd3+ predominantly shortens only the electronic T1Z (Figure 3). Figure 2b shows the dependence of the maximum solid-state 13C nuclear polarization on the concentration of Gd3+. The maximum 13C Pdnp for the Gd3+-free sample (1.4 M [1-13C] pyruvate and 15 mM trityl OX063 in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water glassing matrix) is 9.6 % which corresponds to a spin temperature Ts=8.96 mK. Pdnp increases almost linearly, which implies that the composite parameter monotonically decreases, on the gradual addition of Gd3+ from 0 to c1=1 mM. Further addition of Gd3+ complex in the sample from c1=1 mM to c2=5 mM yielded a constant polarization of approximately 40 % which corresponds to Ts≈2 mK. This suggests that remains the same in this concentration range; in this case, a further decrease in electronic relaxation ratio (η) due to Gd3+ doping is probably offset by a slight increase in the leakage factor f as suggested by the decrease of solid-state nuclear T1 with higher Gd3+ concentration shown in Figure 3. Finally for c>c2, the polarization drops monotonically suggesting a monotonic increase in (higher spin temperature). A detailed ESR measurement of the electronic relaxation of the free radical at DNP conditions is required to identify the individual effects of Gd3+ doping on η and implicitly on f.

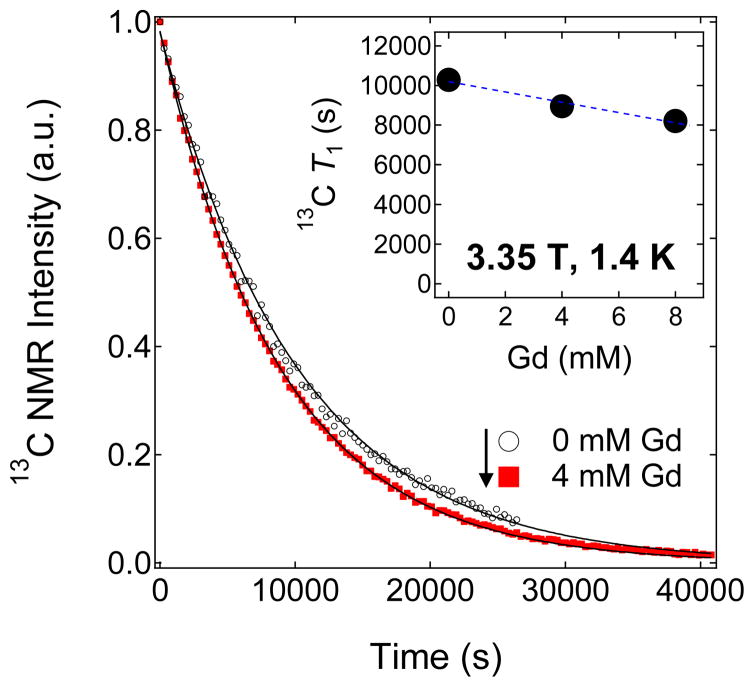

Figure 3.

Representative decay curves of the hyperpolarized solid-state NMR signal of 100 μL trityl-doped samples (1.4 M [1-13C]pyruvate in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water doped with 15 mM trityl OX063) mixed with different concentrations of Gd3+. Inset: 13C solid-state T1 values extracted from the decay curves versus different Gd3+ concentrations.

The solid-state nuclear relaxation T1 of [1-13C] pyruvate samples (1.4 M in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water doped with 15 mM trityl OX063) at 3.35 T and 1.4 K monotonically decreases with increasing Gd3+ concentration as shown in Figure 3. At this low temperature, the relative motions of the electron and nuclear spins are frozen out, and thus the nuclear spins can relax through the fixed paramagnetic impurities which, in this case, refer to the trityl OX063 free radical (with a fixed 15 mM concentration) and a varying Gd3+ concentration (0 to 8 mM) present in the 13C pyruvate samples. In general, the decrease in solid-state 13C T1 with Gd3+ doping can thus be approximately explained by a relaxation equation of an ensemble of nuclear spins due to a low concentration of fixed paramagnetic impurities:2,3

| (2) |

where S is the spin number, Ns is the number of paramagnetic impurities per unit volume, b is the diffusion barrier, τc is the spin correlation time, and Pe is the electron thermal polarization. The correlation time τc is due to the fluctuating local field of the electrons. In the slow motion limit ωnτc≫1, the term τc/(1+(ωnτc)2) reduces to 1/ωn2τc. The factor (1−Pe2) indicates that as electron thermal polarization approaches unity (100 %) by decreasing the temperature and/or increasing the field, the nuclear relaxation rate 1/T1 approaches zero because the electron spins are all in the ground state; the fluctuations disappear and the source of nuclear relaxation is removed.2,3 It can be easily seen from Equation 2 that increasing the concentration of paramagnetic impurities Ns can lead to faster nuclear relaxation rate (shorter T1). Experimentally, although the decrease in the trityl OX063 free radical T1e with Gd3+ doping was drastic (the T1e at 3.35 T and 1.2 K decreased from ~1.2 s to 0.3 s with the addition of 1 mM GdCl3),41 the decrease in nuclear T1 is less dramatic (from T1=10300 s for a Gd-free sample to T1=8200 s for a 13C pyruvate sample doped with 8 mM Gd3+) as shown in Figure 3. These results suggest that the 13C nuclear relaxation in this case proceeds predominantly through the electron dipolar system and the small decrease in 13C T1 with Gd3+ doping is attributed to the slight effect of the mechanism described in Equation 2. The solid-state T1 decay curves of hyperpolarized trityl-doped 13C pyruvate samples with 0 mM and 4 mM Gd3+ (Figure 3) almost overlap in agreement with the results of a previous study41 where GdCl3 doping barely changed the 13C T1 in the concentration range 0–2 mM.

3.2. DNP of BDPA-doped [1-13C]pyruvic acid

The carbon-centered free radical, 1,3-bisdiphenylene-2-phenylallyl (BDPA) has an ESR linewidth D comparable with that of trityl OX063 and, therefore, is expected to have similar DNP efficiency via the thermal mixing process. Although BDPA is insoluble in water, it is readily soluble in sulfolane and a few other solvents (e.g. methanol, diethylene glycol monobenzyl ether, DMSO). We have shown recently that comparable or slightly higher nuclear polarizations can indeed be achieved for [1-13C]pyruvic acid doped with BDPA (40 mM) than with trityl OX063 (15 mM) in the absence of Gd3+.45 In addition, BDPA offers the advantage of easy removal in the dissolution liquid by simple filtration when water is used as the dissolution solvent.45 The optimum concentration of BDPA for DNP was found to be 20–40 mM, but, for practical purposes, 40 mM BDPA concentration is used because maximum nuclear polarization is reached with less microwave irradiation time.

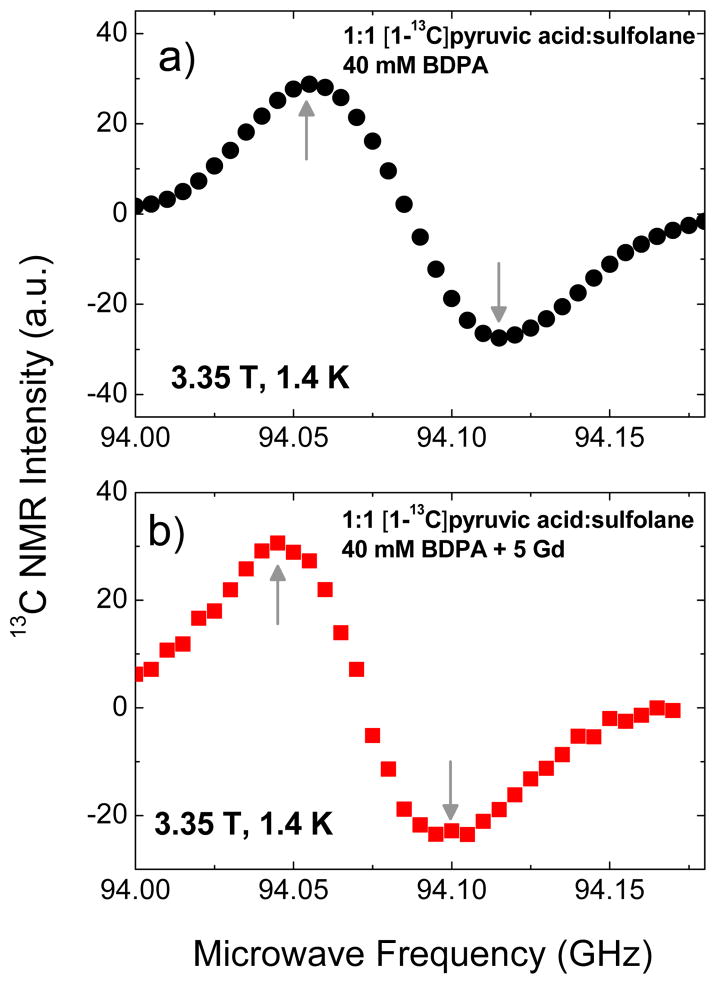

For DNP experiments with BDPA, we opted to use free [1-13C]pyruvic acid, which is miscible with sulfolane, instead of sodium [1-13C]pyruvate salt which is poorly soluble in the glassing solvents (DMSO or sulfolane) suitable for BDPA. The DNP samples consisted of 1:1 (v/v) sulfolane:[1-13C]pyruvic acid doped with 40 mM BDPA as described in a previous work.45 The 13C microwave DNP spectra of BDPA-doped [1-13C] pyruvic acid in the presence and absence of Gd3+ (Figure 4) are similar to those obtained with trityl OX063. The narrowing in the separation distance of the positive and negative polarization peaks in the presence of Gd3+ is also present. The polarization buildup curves were taken at 94.055 GHz, close to the positive polarization peaks of the Gd-free and Gd-doped DNP samples.

Figure 4.

Microwave DNP spectra of 1:1 [1-13C]pyruvic acid:sulfolane samples doped with a) 40 mM BDPA and b) 40 mM BDPA plus 5 mM Gd3+. These data were taken in the HyperSense at 3.35 T and 1.4 K using a 100 mW microwave source. The up and down arrows indicate the approximate locations of the positive and negative polarization peaks, respectively.

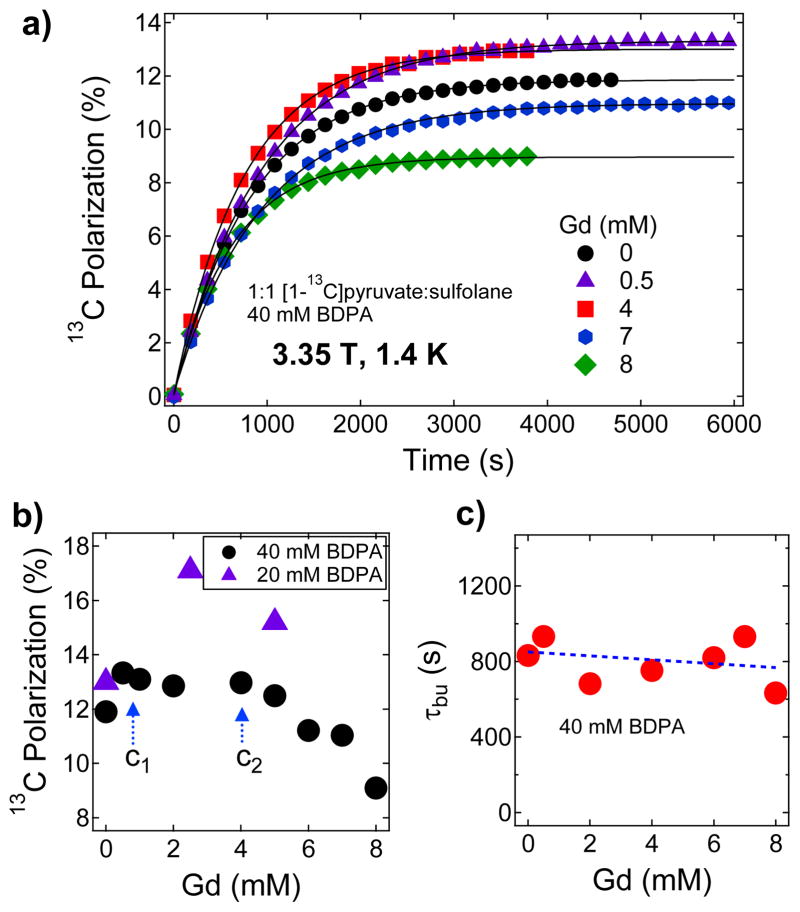

Figure 5a shows the polarization buildup curves for [1-13C]pyruvic acid samples doped with different concentrations of Gd3+ and a summary of maximum Pdnp obtained with different Gd3+ concentrations is displayed in Figure 5b. Figure 5c shows that the polarization buildup time constant remains roughly constant (τbu≈800 s) over the Gd3+ concentration range of 0–8 mM. The relatively faster polarization buildup time τbu for these BDPA-doped samples is attributed to a faster spin diffusion,56 a combined effect of the high density of 13C spins (7.7 M [1-13C]pyruvic acid after mixing with equal volume of sulfolane) as well as to the high BDPA free radical concentration (40 mM). The maximum 13C nuclear polarization attained for a Gd-free BDPA-doped (40 mM) pyruvic acid sample is close to 12 % corresponding to Ts=7.16 mK. Addition of Gd3+ in the sample of up to 1 mM led to a small increase in Pdnp (up to 14 % maximum polarization; Ts=6.12 mK) and this polarization level remained roughly constant in the Gd3+ concentration range from c1=1 mM to c2=4 mM. Further addition of Gd3+ at c>c2 led to a monotonic decrease in the nuclear polarization.

Figure 5.

a) Polarization buildup curves of 1:1 (v/v) [1-13C]pyruvic acid:sulfolane doped with 40 mM BDPA and mixed with different concentrations of Gd3+ at 3.35 T and 1.4 K. The buildup was monitored by irradiating the samples at 94.055 GHz with a 100 mW microwave source. b) the maximum 13C nuclear polarization of [1-13C]pyruvate sample as a function of Gd3+ concentration derived from Figure 5ac) Polarization buildup time constant versus Gd3+ concentration derived by fitting single-exponential buildup equation of data from Figure 5a.

These trends are similar to those obtained for the trityl doped-samples, but the improvement in the base nuclear polarization (Gd-free Pdnp) for BDPA-doped samples is relatively small compared to the results obtained with trityl OX063. A question arises whether a lower concentration of BDPA would improve the maximum nuclear polarization currently achieved with Gd3+ doping. To this end, we have performed DNP measurements of the same samples doped with 20 mM BDPA. The base Pdnp was found to be close to 13 % and with the addition of 2.5 mM Gd3+, the polarization jumped to 17 % (Ts=5.03 mK) as shown in Figure 5b. With a lower BDPA concentration (20 mM) in the sample, the improved polarization level was achieved at the expense of a longer microwave irradiation time with a buildup time constant increased to τbu=2050 s (see the Supporting Information).

It should be noted that direct comparison of the effect of Gd3+ on the DNP with trityl OX063 and BDPA samples cannot be made because the substrates (sodium pyruvate and pyruvic acid) as well as the glassing matrices (water-glycerol and sulfolane) were different. The nature of glassing agents may have significant influence on DNP.35,37 Preliminary data (Supporting Information) on the polarization of 1:1 sulfolane:[1-13C]pyruvic acid sample doped with 15 mM trityl OX063 yielded a value close to 12 % and with the addition of 2.5 mM Gd3+, the nuclear polarization only doubled to Pdnp≈25 %.

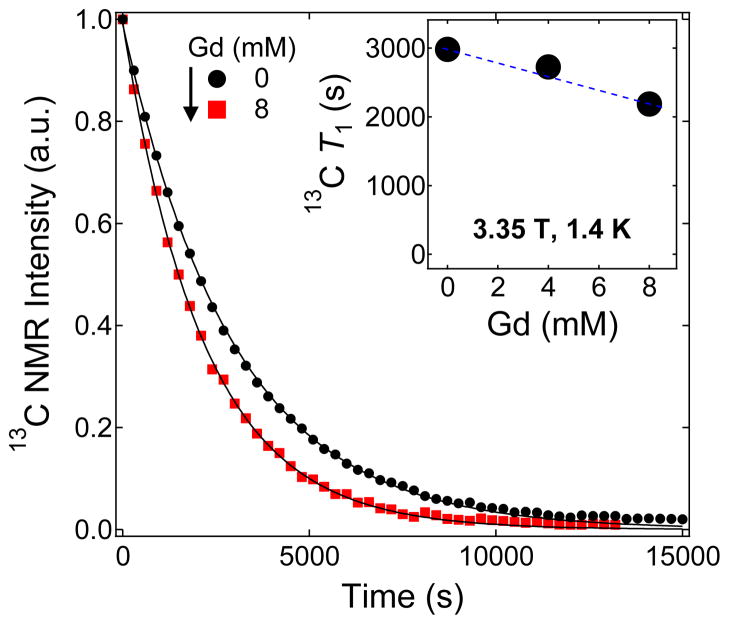

Figure 6 shows the effect of Gd3+ doping on the solid-state nuclear T1 of the BDPA-doped samples inside the HyperSense polarizer at 3.35 T and 1.4 K. The solid-state T1 relaxation for a Gd-free [1-13C] pyruvic acid sample doped with 40 mM BDPA is close to 3000 s and it decreases to 2200 s with the addition of 8 mM Gd3+. On the other hand, a Gd-free 13C pyruvic acid sample doped with 20 mM BDPA has a T1=6800 s and with 10 mM Gd3+ doping, T1=3400 s (see the T1 decay curves in the Supporting Information). The higher polarization obtained with Gd-doped [1-13C]pyruvic acid in the presence of 20 mM BDPA suggests that achieving optimal results requires a delicate balance of the electronic and nuclear relaxation parameters53 that are embedded in Equation 1.

Figure 6.

Representative decay curves of the hyperpolarized 13C NMR signal of 1:1 (v/v) [1-13C]pyruvic acid:sulfolane doped with 40 mM BDPA mixed with different Gd3+ concentration. The solid lines are fits to an equation accounting for the decay of hyperpolarized NMR signal due to rf excitation and T1 decay. Inset: a summary of the solid-state 13C nuclear T1 relaxation values of BDPA-doped samples mixed with different Gd3+ concentration.

3.3. DNP of [1-13C] sodium pyruvate doped with 4-oxo-TEMPO

The nitroxide-based free radical 4-oxo-TEMPO has an ESR linewidth (D=5.25 mT at 2.5 T and 1 K)53 that is much wider than that of the carbon-centered free radicals, trityl OX063 and BDPA. As a consequence, the DNP of 4-oxo-TEMPO-doped 13C substrates, which proceeds predominantly via thermal mixing, yields relatively lower polarization compared with trityl and BDPA. Nevertheless, 4-oxo-TEMPO and other nitroxyls are becoming routine polarizing agents in fast dissolution DNP-NMR because of their commercial availability and lower cost. The optimum concentration of 4-oxo-TEMPO for 13C DNP samples was found to be around 30-50 mM.37,57

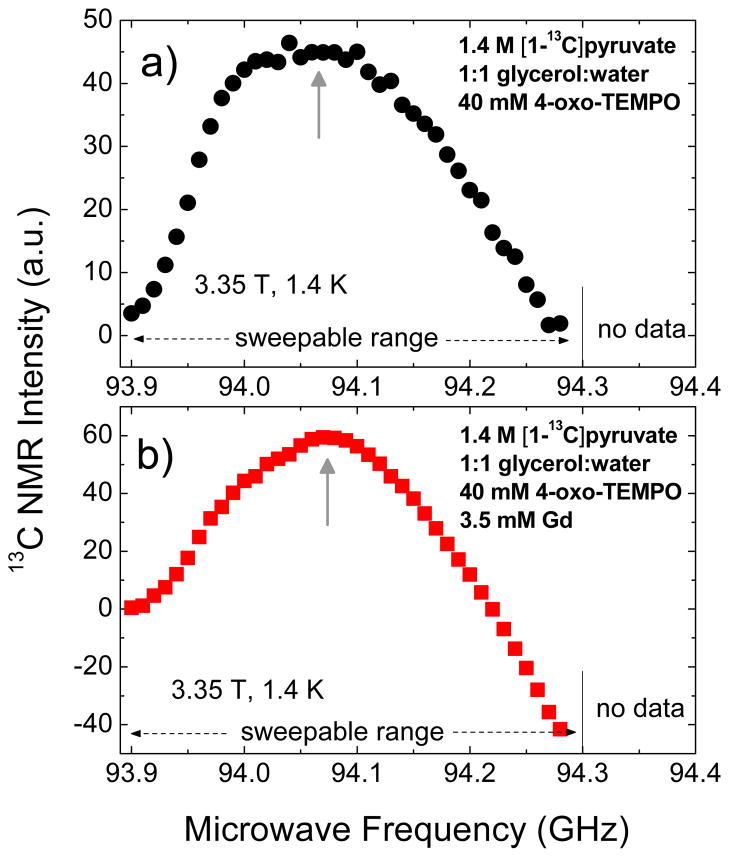

Figure 7 shows the microwave DNP spectra of 1.4 M [1-13C]pyruvate in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water glassing matrix doped with 40 mM 4-oxo-TEMPO in the presence and absence of Gd3+. Due to the limited frequency range of the microwave source in the HyperSense, only the positive polarization peak of the DNP spectrum is accessible for measurement; the negative polarization peak is located at higher microwave frequency. The microwave DNP spectrum of the Gd-free sample in Figure 7a only shows positive NMR intensity whereas the Gd-doped sample in Figure 7b starts to show negative NMR intensity in the frequency range 94.20–94.30 GHz, indicative of negative spin temperature. The latter hints that part of the negative polarization peak is shown, most likely due to a substantial shift of P(−) to lower frequency similar to the 13C microwave DNP spectra of trityl and BDPA-doped samples with Gd3+. It should be pointed out that the ESR linewidth of 4-oxo-TEMPO53 is larger than the Larmor frequencies of both 1H and 13C, thus both nuclear species could be polarized at the same microwave frequency via the thermal mixing process.37 Unlike the trityl-doped 13C samples where it was shown in a previous study48 that 1H proceeds mainly via the solid effect at 3.35 T and 1.2 K, a proper way to prepare identical initial state when plotting the 13C microwave DNP spectrum of TEMPO-doped 13C samples may necessitate destroying the proton polarization in addition to depolarizing the remnant 13C magnetization from a previous microwave frequency. In our current instrumental setup, we could not verify this experimentally because the built-in NMR coil of the HyperSense polarizer cannot be tuned to 1H but this point should be noted for future experiments of TEMPO-doped samples because of the thermal contact of 1H and 13C nuclear Zeeman systems via the electron spin-spin interaction reservoir.

Figure 7.

Microwave DNP spectra of 100 μL samples of 1.4 M [1-13C]pyruvate in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water doped with a) 40 mM 4- oxo-TEMPO and b) 40 mM 4-oxo-TEMPO and 3.5 mM Gd3+. These data were taken in the HyperSense at 3.35 T and 1.4 K using a 100 mW microwave source. The up arrows indicate the approximate location of the positive polarization peak. Due to the limited microwave frequency range of the source, measurement at frequency ωe>94.30 GHz, where the negative polarization peak is located, is not accessible.

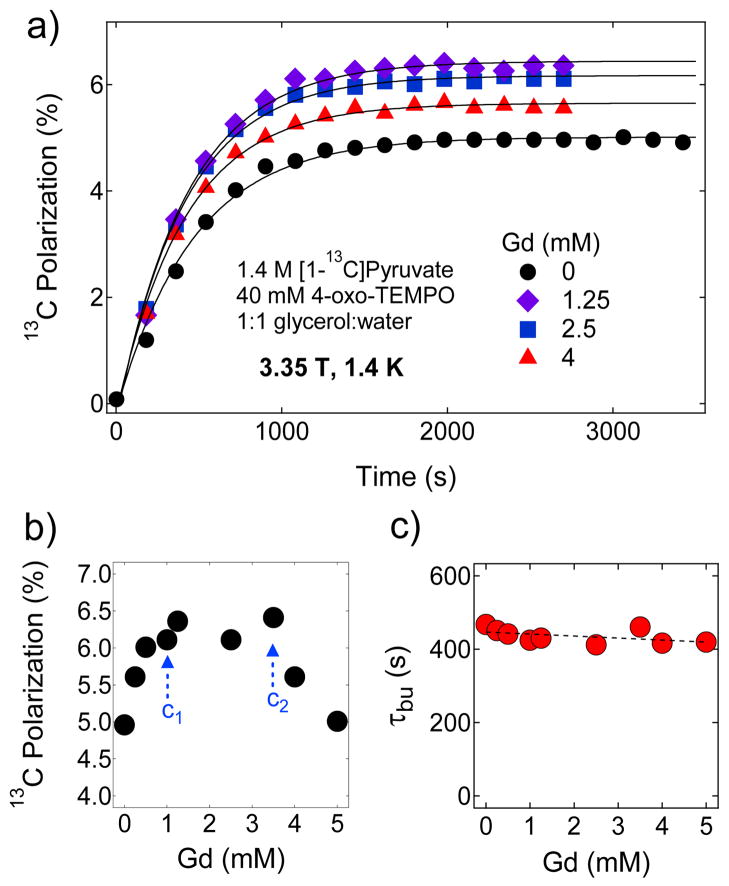

Figure 8a shows the representative polarization buildup curves of 100 μL aliquots of 4-oxo-TEMPO-doped 13C pyruvate samples mixed with different concentrations of Gd3+ at 3.35 T and 1.4 K. These buildup curves were taken at 94.07 GHz, the approximate location of P(+) for the TEMPO-doped 13C samples. In the absence of Gd3+, the base DNP-enhanced nuclear polarization of the TEMPO-doped sample was found to be Pdnp≈5 % which is approximately half the base Pdnp yielded on the same sample doped with 15 mM trityl OX063 at 3.35 T and 1.4 K shown in Figure 2a. As mentioned before, this is expected since the broad 4-oxo-TEMPO D corresponds to a higher electronic heat capacity which leads to relatively higher spin temperature achieved for both the electron dipolar system and nuclear Zeeman reservoir.35,53 A summary of the maximum nuclear polarization achieved as a function of Gd3+ concentration is displayed in Figure 8b. Additionally, the polarization buildup time constants τbu displayed in Figure 8c remained roughly the same in the 0–5 mM Gd3+ doping range. The relatively short τbu’s here is attributed to the high concentration of free radical present in these samples.

Figure 8.

a) Representative polarization buildup curves of 1.4 M [1-13C]pyruvate samples doped 40 mM 4-oxo-TEMPO and mixed with different concentrations of Gd3+ at 3.35 T and 1.4 K. The buildup was monitored by irradiating the samples at 94.07 GHz with a 100 mW microwave source. b) the maximum 13C nuclear polarization of [1-13C]pyruvate sample as a function of Gd3+ concentration derived from Figure 8a. c) Polarization buildup time constant vs. Gd3+ concentration derived by fitting the polarization buildup curves with a single-exponential buildup equation.

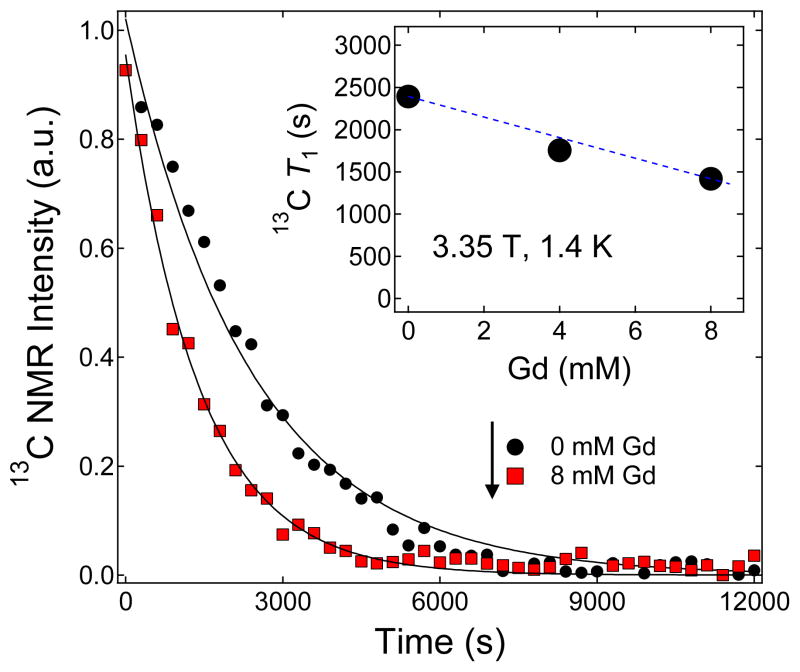

Similar to the pattern observed in trityl OX063 and BDPA-doped samples, the nuclear polarization monotonically increases as Gd3+ is added until a concentration c1≈1 mM, although the increase was relatively modest (only 20 % improvement of base Pdnp) compared to the results obtained with trityl OX063 (approximately 300 % increase in base Pdnp). Also, the solid-state nuclear polarization was roughly constant in the Gd3+ concentration c1<c<c2, where in this particular case c2≈3.5 mM and at c>c2, a monotonic decrease in Pdnp is observed. These results point out that the influence of Gd3+ on Pdnp are similar for all three radicals, however the effect is most pronounced in trityl-doped samples where the free radical concentration used is relatively lower (15 mM). Similar measurements performed on samples doped with reduced 4-oxo-TEMPO concentration (20 mM; see the Supporting Information) yielded roughly the same improvement in Pdnp with Gd3+ doping at a longer microwave irradiation time. Concomitant with these changes in Pdnp with Gd3+ doping is a monotonic decrease in the solid-state nuclear T1 as the sample is doped with Gd3+ from 0 to 8 mM as shown in Figure 9. The 13C T1 drop from 2400 s with 0 mM Gd3+ to 1400 s with 8 mM Gd3+. Finally, it is currently unclear why the optimum concentration of trityl OX063 in DNP samples is generally lower than the optimum concentration of 4-oxo-TEMPO and even BDPA. It should be noted, however, that the chemical structure of trityl OX063 as shown in Chart 1 is special compared to 4-oxo-TEMPO and BDPA: its paramagnetic electron is a) enclosed in a very symmetric structure to minimize the g-anisotropy and b) surrounded mainly by non-NMR active nuclei which lowers the hyperfine interaction.53

Figure 9.

Representative decay curves of the hyperpolarized solid-state NMR signal of 100 μL TEMPO-doped samples (1.4 M [1-13C]pyruvate in 1:1 (v/v) glycerol:water doped with 40 mM 4-oxo-TEMPO) mixed with different concentrations of Gd3+. The experiments were performed after the samples achieved maximum polarization level and the microwave source was turned off. Inset: Summary of the 13C solid-state T1 values extracted from the decay curves versus different Gd3+ concentrations.

4. CONCLUSION

In summary, we have extensively investigated the effects of Gd3+ over a wide concentration range on the DNP of a biologically important substrate [1-13C]pyruvate polarized with different free radicals used in fast dissolution DNP, trityl OX063, 4-oxo-TEMPO, and BDPA. We have found three regions of interest for all three radicals in the plot of DNP-enhanced polarization versus Gd3+ concentration: (i) a monotonic increase in DNP-enhanced nuclear polarization Pdnp upon increasing the Gd3+ concentration until a certain threshold concentration c1 (1–2 mM), (ii) a region of constant maximum Pdnp from c1 until a concentration threshold c2 (4–5 mM), and (iii) a monotonic decrease in Pdnp at Gd3+ concentration c > c2. Of the three free radical polarizing agents examined here, the symmetric, carbon-centered trityl OX063 (15 mM) gave the best response to Gd3+ doping with 300 % increase in the base solid-state DNP-enhanced polarization whereas addition of Gd3+ at the optimum concentration to BDPA (40 mM) and 4-oxo-TEMPO-doped (40 mM) samples yielded only a modest 5–20 % increase in the base polarization. The improvement in Pdnp with Gd3+ doping is ascribed to the decrease in the electronic relaxation parameter η which results in a lower spin temperature achieved by the nuclear Zeeman system. Extensive ESR studies are needed to elucidate the details of the exceptional improvement in the DNP-enhanced polarization of trityl-doped samples with Gd3+ doping compared to samples doped with BDPA or 4-oxo-TEMPO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R21EB009147, RO1-HL34557, and P41-RR02584/P41-EB02584) for the financial support of this work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. 13C microwave DNP spectra of trityl-doped [1-13C]pyruvate samples with longer irradiation times, 13C pulsewidth calibration at DNP conditions, optimization of trityl OX063 free radical concentration in 13C sodium pyruvate samples, polarization buildup curves of trityl-doped (15 mM) 1:1 (v/v) [1-13C]pyruvic acid:sulfolane sample with and without Gd-HP-DO3A, DNP-enhanced solid-state nuclear polarization Pdnp and T1 decay of BDPA-doped (20 mM) [1-13C]pyruvic acid samples, and solid-state Pdnp of 4-oxo-TEMPO-doped (20 mM) [1-13C]pyruvate samples. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ardenkjær-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abragam A, Goldman M. Nuclear Magnetism: Order and Disorder. Clarendon, Oxford University Press; UK: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abragam A, Goldman M. Rep Prog Phys. 1978;41:395–467. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crabb DG, Meyer W. Annu Rev Nucl Part Sci. 1997;47:67–109. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boer W. J Low Temp Phys. 1976;22:185–212. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Day SE, Hu DE, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, in’t Zandt R, Jensen PR, Karlsson M, Golman K, Lerche MH, et al. Nature. 2008;453:940–944. doi: 10.1038/nature07017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albers MJ, Bok R, Chen AP, Cunningham CH, Zierhut ML, Zhang VY, Kohler SJ, Tropp J, Hurd RE, Yen YF, et al. J Cancer Res. 2008;68:8607–8615. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Day SE, Kettunen MI, Gallagher FA, Hu DE, Lerche M, Wolber J, Golman K, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Brindle KM. Nat Med. 2007;13:1382–1387. doi: 10.1038/nm1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lupo JM, Chen AP, Zierhut ML, Bok RA, Cunningham CH, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Nelson SJ. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;28:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Storey C, Jeffrey FM, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19773–19777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706235104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Brindle K, Chekmenev EY, Comment A, Cunningham CH, DeBerardinis RJ, Green GG, Leach MO, Rajan SS, et al. Neoplasia. 2011;13:81–97. doi: 10.1593/neo.101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brindle KM, Bohndiek SE, Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:505–519. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, Burgess SC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19084–19089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111247108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brindle K. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:94–107. doi: 10.1038/nrc2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Brindle KM. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2009;55:285–295. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Storey C, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:1029–1036. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohndiek SE, Kettunen MI, Hu DE, Kennedy BWC, Boren J, Gallagher FA, Brindle KM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11795–11801. doi: 10.1021/ja2045925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder MA, Atherton HJ, Ball DR, Cole MA, Heather LC, Griffin JL, Clarke K, Radda GK, Tyler DJ. Faseb Journal. 2009;23:2529–2538. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohndiek SE, Kettunen MI, Hu DE, Witney TH, Kennedy BWC, Gallagher FA, Brindle KM. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3278–3288. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson DM, Keshari KR, Larson PEZ, Chen AP, Hu S, Van Criekinge M, Bok R, Nelson SJ, Macdonald JM, Vigneron DB, et al. J Magn Reson. 2010;205:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Hu DE, Jensen PR, in’t Zandt R, Karlsson M, Gisselsson A, Nelson SK, Witney TH, Bohndiek SE, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19801–19806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911447106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen PR, Peitersen T, Karlsson M, in’t Zandt R, Gisselsson A, Hansson G, Meier S, Lerche MH. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:36077–36082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurd RE, Yen YF, Tropp J, Pfefferbaum A, Spielman DM, Mayer D. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1734–1741. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlsson M, Jensen PR, in’t Zandt R, Gisselsson A, Hansson G, Duus JO, Meier S, Lerche MH. Intl J Cancer. 2010;127:729–736. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau AZ, Chen AP, Ghugre NR, Ramanan V, Lam WW, Connelly KA, Wright GA, Cunningham CH. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:1323–1331. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witney TH, Kettunen MI, Hu DE, Gallagher FA, Bohndiek SE, Napolitano R, Brindle KM. British J Cancer. 2010;103:1400–1406. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day SE, Kettunen MI, Cherukuri MK, Mitchell JB, Lizak MJ, Morris HD, Matsumoto S, Koretsky AP, Brindle KM. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:557–563. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Day SE, Hu DE, Karlsson M, Gisselsson A, Lerche MH, Brindle KM. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:18–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu S, Balakrishnan A, Bok RA, Anderton B, Larson PEZ, Nelson SJ, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Goga A. Cell Metab. 2011;14:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacKenzie JD, Yen YF, Mayer D, Tropp JS, Hurd RE, Spielman DM. Radiology. 2011;259:414–420. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10101921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cudalbu C, Comment A, Kurdzesau F, van Heeswijk RB, Uffmann K, Jannin S, Denisov V, Kirik D, Gruetter R. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:5818–5823. doi: 10.1039/c002309b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Heeswijk RB, Uffmann K, Comment A, Kurdzesau F, Perazzolo C, Cudalbu C, Jannin S, Konter JA, Hautle P, van den Brandt B, et al. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1489–1493. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Kovacs Z, Kshirsagar P, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12942–12943. doi: 10.1021/ja075768z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jindal AK, Merritt ME, Suh EH, Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Kovacs Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1784–1785. doi: 10.1021/ja910278e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lumata L, Jindal AK, Merritt ME, Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Kovacs Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8673–8680. doi: 10.1021/ja201880y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lumata L, Merritt ME, Hashami Z, Ratnakar SJ, Kovacs Z. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2012;51:525–527. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurdzesau F, van der Brandt B, Comment A, Hautle P, Jannin S, van der Klink JJ, Konter JA. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2008;41:155506. doi: 10.1063/1.2951994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goertz ST, Harmsen J, Heckmann J, Heß C, Meyer W, Radtke E, Reicherz G. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res, Sect A. 2004;526:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer W, Heckmann J, Hess C, Radtke E, Reicherz G, Triebwasser L, Wang L. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res, Sect A. 2011;631:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thaning M, Servin R. WO 2007/064226 A2. W. I. P; Norway: International Patent Publication Number.

- 41.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Macholl S, Johannesson H. Appl Magn Reson. 2008;34:509–522. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lerche MH, Meier S, Jensen PR, Baumann H, Petersen BO, Karlsson M, Duus JO, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. J Magn Reson. 2010;203:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen PR, Karlsson M, Meier S, Duus JO, Lerche MH. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:10010–10012. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grant AK, Vinogradov E, Wang X, Lenkinski RE, Alsop DC. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66:746–755. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lumata L, Ratnakar SJ, Jindal A, Merritt M, Comment A, Malloy C, Sherry AD, Kovacs Z. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:10825–10827. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patyal BR, Gao JH, Williams RF, Roby J, Saam B, Rockwell BA, Thomas RJ, Stolarski DJ, Fox PT. J Magn Reson. 1997;126:58–65. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johanneson H, Macholl S, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. J Magn Reson. 2009;197:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolber J, Ellner F, Fridlund B, Gram A, Johannesson H, Hansson G, Hansson LH, Lerche MH, Mansson S, Servin R, et al. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res, Sect A. 2004;526:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jannin S, Comment A, Kurdzesau F, Konter JA, Hautle P, van der Brandt B, van der Klink JJ. J Chem Phys. 2008;128:241102–24104. doi: 10.1063/1.2951994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corzilius B, Smith AA, Barnes AB, Luchinat C, Bertini I, Griffin RG. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5648–5651. doi: 10.1021/ja1109002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagarajan V, Hovav Y, Feintuch A, Vega S, Goldfarb D. J Chem Phys. 2010;132:214504–214513. doi: 10.1063/1.3428665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benmelouka M, Van Tol J, Borel A, Port M, Helm L, Brunel LC, Merbach AE. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:7807–7816. doi: 10.1021/ja0583261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heckmann J, Meyer W, Radtke E, Reicherz G, Goertz S. Phys Rev B. 2006;74:134418. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heß C. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2011;295:012021. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goertz ST. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res, Sect A. 2004;526:28–42. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lumata L, Kovacs Z, Malloy C, Sherry AD, Merritt M. Phys Med Biol. 2011;56:N85–N92. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/5/N01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Comment A, van der Brandt B, Uffman K, Kurdzesau F, Jannin S, Konter JA, Hautle P, Wenkebach WT, Gruetter R, van der Klink JJ. Concepts Magn Reson, Part B. 2007;31:255–269. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.