Abstract

The multivariate relationship between hair cortisol, whole blood thyroid hormones, and the complex mixtures of organohalogen contaminant (OHC) levels measured in subcutaneous adipose of 23 East Greenland polar bears (eight males and 15 females, all sampled between the years 1999 and 2001) was analyzed using projection to latent structure (PLS) regression modeling. In the resulting PLS model, most important variables with a negative influence on cortisol levels were particularly BDE-99, but also CB-180, -201, BDE-153, and CB-170/190. The most important variables with a positive influence on cortisol were CB-66/95, α-HCH, TT3, as well as heptachlor epoxide, dieldrin, BDE-47, p,p′-DDD. Although statistical modeling does not necessarily fully explain biological cause-effect relationships, relationships indicate that (1) the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in East Greenland polar bears is likely to be affected by OHC-contaminants and (2) the association between OHCs and cortisol may be linked with the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis.

Keywords: cortisol, thyroid hormone, contaminants, stress, organohalogens, polar bear, HPA axis, HPT axis

Introduction

The Arctic is a sink for long-range transportable persistent organohalogen contaminants (OHCs), all of which are produced and released into wind and ocean currents in the industrialized world (AMAP 2004). Many of these pollutants and their metabolites have been shown to possess biological activities within the context of the broad classification of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). That is, they have an ability on some biochemical or level of biological organization basis to disrupt the balance of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, as well as the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. This effect can occur even at chronic low-level EDC exposure, causing detrimental effects on development, behavior, reproduction, immunology and general survival of the affected organism (Colborn et al. 1993; Vos et al. 2000; Mendes 2002; Chalubinski & Kowalski 2006; Prasanth et al. 2010; Hamlin & Guillette 2011). OHCs are often lipophilic, accumulating in the fatty tissues of e.g. ringed (Phoca hispida) and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus), the preferred prey of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) (Ramsay & Stirling 1988; Derocher et al. 2002). Hence, East Greenland and Barents Sea polar bears have been found to carry some of the highest OHC loads of any Arctic mammal species (Norstrom et al. 1998; Dietz et al. 2004; Verreault et al. 2005; Muir et al. 2006; Dietz et al. 2007; Gebbink et al. 2008; Letcher et al. 2010). Chronic exposure to OHCs in polar bears have been associated with afflictions such as endocrine disruption, impaired immune system, reduced size of sexual organs, and organ histopathology (Gutleb et al. 2010; Letcher et al. 2010; Sonne 2010; Villanger et al. 2011a; Bechshøft et al. Submitted).

Several studies of wildlife species, including polar bears, indicate the vitally important corticoid and thyroid hormone systems are potentially vulnerable to disruption by OHCs (Braathen et al. 2004; Odermatt et al. 2006; Verboven et al. 2010; Villanger et al. 2011a,b). Cortisol is the major corticosteroid hormone in most mammals and participates in the physiological regulation of most body tissues (McDonald & Langston 1995), including the regulation of metabolism, growth, and development, as well as responses to stress influencing the physiology and endocrinology of the reproductive and immune systems (Moberg 1991; Dobson & Smith 2000; Sjaastad et al. 2003; von Borell et al. 2007; Schmidt & Soma 2008). Polar bear cortisol levels have traditionally been measured in blood plasma (Tryland et al. 2002; Haave et al. 2003; Oskam et al. 2004), but were reported recently in hair of East Greenland polar bears (Bechshøft et al. 2011; Bechshøft et al. Submitted). Hair provides a much more stable matrix which reflects long-term stress levels instead of rapid fluctuations brought on by acute stress or inherent variation (Koren et al. 2002; Davenport et al. 2006).

The thyroid hormones (THs) thyroxine (T4, 3,5,3′,5′-tetraiodothyronine) and triiodothyronine (T3, 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine) are of critical importance to neurodevelopment in young animals (fetus, neonate, and juvenile) and for the development and function of somatic cells and gonads (Cooke et al. 2004). THs also influence the circulating levels of sex steroids, and are involved in the regulation of metabolism, thermoregulation, reproduction, and in maintaining the general physiological homeostasis (Hadley 1996; McNabb 1992; Cooke et al. 2004; Zoeller et al. 2007). An increased level of cortisol can result in an inhibition of the production of THs in the thyroid gland itself, or lead to a decrease in the deiodination of T4 to T3 (Chastain & Panciera 1995). Thus, high cortisol levels can lead to lower serum T4 or T3 or both. However, clinical studies of hyperthyroid patients and animals have shown that (sub)clinical hyperthyroidism may be associated with adrenocortical hyperactivity, i.e. increased cortisol concentrations (Johnson et al. 2005 and references there-in). Therefore, increased thyroid levels may actually in some cases lead to increased cortisol concentrations.

The connection between cortisol and THs has been studied extensively in controlled experiments involving birds, fish, and humans (Geris et al. 1999; Douyon & Schteingart 2002; Kitaysky et al. 2005; Walpita et al. 2007; Peter 2011). However, wildlife ecotoxicology studies tend to examine the effect of contaminants on either cortisol or the THs (Jenssen et al. 1994; Skaare et al. 2001; Routti et al. 2010; Corlatti et al. 2011), or actually measure both but without correlating them (Bubenik & Brown 1989; Saeb et al. 2010). The objective of the present study was therefore to investigate the multivariate relationship between hair cortisol, whole blood circulating thyroid hormone, and tissue complex mixtures of organohalogen contaminant levels measured in subcutaneous adipose of East Greenland polar bears.

Materials and methods

The sample

A total of 23 East Greenland polar bears were included in this study. Of these eight were males (mean age: 6.7 years, range: 5–9) and 15 were females (mean age: 9.8 years, range: 3–22). All bears were sampled between the years 1999 and 2001. Age estimation had been done according to Dietz et al. (1991). The individual polar bears and their cortisol and TH levels have previously been included in, respectively, the studies presented in Bechshøft et al. (2011; Submitted) and Villanger et al. (2011a), which also give further details on the samples used in the present study. Biological measurements were taken in the field when sampling the bear. Detailed descriptions of tissue sampling and biological measurements are given elsewhere (Dietz et al. 2004; Sandala et al. 2004). Body mass (BM) was calculated based on measured body length and girth according to Derocher & Wiig (2002), and date of capture was calculated into a numerical value between 1 and 365.

OHC analysis of adipose tissue

The OHC analysis methods and subsequent quantitative results for the present polar bears have been reported in Dietz et al. (2004, 2007). The individual or co-eluted compounds measured in subcutaneous adipose tissue included in the present study were: CB-31/28, -52, -60, -64/71, -66/95, -74, -97, -99, -101/84, -118, -128, -129/178, -138, -146, -151, -153, -170/190, -171/202/156, -172, -177, -180, -182/187, -183, -194, -195, -200, -201, -203/196, and -206; BDE-47, -99, -100, -153, α- and β-hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), hexachlorobenzene (HCB), trichlorobenzene (TCB), pentachlorobenzene (QCB), 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl)ethane) (p,p′-DDT), 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl)ethylene), (p,p′-DDE),1,1,dichloro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl) ethane) (p,p′-DDD), oxychlordane, cis-chlordane, trans-chlordane, cis-nonachlor, trans-nonachlor, heptachlor epoxide, dieldrin and octachlorostyrene (OCS). All contaminant concentrations are given in nanograms per gram lipid weight (ng/g l.w.).

Cortisol analysis of hair

Hair samples were analyzed for cortisol according to the procedure described in Bechshøft et al. (2011). In short, hair samples were washed, dried, and then ground to a fine powder in an MM 200 ball mill (Retsch, Newtown, USA). Approximately 50 mg of powdered hair was extracted for 24 h with HPLC-grade methanol (Fisher Scientific), dried down, reconstituted in assay buffer, and then analyzed for cortisol using a sensitive and specific enzyme immunoassay (Salimetrics, State College, PA, USA). Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation of this assay averaged less than 10 %.

Thyroid hormone analysis of whole blood

Polar bear whole blood samples were analyzed for total T3 (TT3) and total T4 (TT4) at the Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU, Trondheim, Norway). The blood samples were extracted with ethanol prior to analysis using commercially available solid-phase 125I radioimmunoassay (RIA) kits (Coat-A-Count Total T3 and Coat-A-Count Total T4, Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA, USA). The procedures described in the test protocols were followed (Siemens 2006a, b). A more detailed description of the analytical procedures and quality assurance are presented in Villanger et al. (2011a).

Data analysis

The data in this study consisted of 23 polar bears grouped according to age and sex (Rosing-Asvid et al. 2002); Subadults (Sub, consisting subadult females <5 yr and subadult males <6 yr, n = 5); Adult males (AdM, consisting of males ≥ 6 yr, n = 6), and adult females (AdF consisting of females ≥ 5 yr, n = 12). Multivariate analyses were performed using the software Simca-P+ (Version 12.0, Umetrics AB, Umeå, Sweden). Projections to latent structures by means of partial least squares (PLS; Eriksson et al. 2006) was applied to investigate the multivariate relationships between the predictor (X)-variables (contaminants and biological data including circulating TH levels) and their unidirectional influence on the response (Y)-variable cortisol. This multivariate regression method has been applied in several recent wildlife studies (Murvoll et al. 2006; Jenssen et al. 2010; Villanger et al. 2011a, b). Since factors such as age and sex can influence TH levels and responses, effect studies should ideally consider these as covariates or perhaps separate statistical analyses based on these factors (Gochfeld 2007; Zoeller et al. 2007; Abdelouahab et al. 2008). However, hair cortisol levels have been shown to be independent of age and sex (Bechshøft et al. Submitted). In any case, sample size in the various age and sex groups in the current study was considered too low for separate analyses. Thus, Sub, AdF and AdM were grouped together when investigating the multivariate influence of individual OHC load, age, sex, morphometric data, lipid content of adipose tissue, capture day, and circulating TT3 and TT4 on hair cortisol levels using PLS.

Since normality is not required for PLS regression, data were not transformed. All variables were centered and scaled (to variance 1), and significance level was set to 0.05 (Umetrics 2008). PLS modeling was validated by the explained variation in the X-matrix (R2X), explained variance of the Y-variables by the X-matrix (goodness of fit, R2Y), goodness of prediction (Q2) obtained by cross-validation and permutation analyses (20 permutations) and an analysis of variance testing of cross-validated predictive residuals (CV-ANOVA; see Eriksson et al. 2008; Umetrics 2008). The importance of individual X-variables in explaining the X- and Y-matrix were evaluated using the variable importance for the regression (VIP) values. A VIP value > 1 denotes high importance for the model, and a VIP < 0.5 indicate low or no importance (Umetrics 2008). Optimizing of the PLS model was done by successively removing X-variables with lowest VIP values. Another evaluation parameter for individual X-variables used herein is the regression coefficient (CoeffCS) value, which shows the correlative relationship (strength and direction) between each X-variable with Y (Umetrics 2008). A more detailed description of PLS can be found elsewhere (Eriksson et al. 2006; Umetrics 2008; Wold et al. 2001).

Results

The sample

Basic statistics for hormones and contaminants levels in hair, whole blood, and subcutaneous adipose tissue are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary statistics (Mean ± SD, Min-Max, n) for age, hair cortisol samples (pg mg−1 hair), whole blood thyroid hormones (nmol/L), and subcutaneous adipose tissue organohalogen contaminants (ng/g l.w.) measured in 23 East Greenland polar bears. Contaminant data were originally published as part of Dietz et al. (2004, 2007). Circulating TT3 and TT4 levels were first presented in Villanger et al. (2011a) and cortisol levels were published in Bechshøft et al. (Submitted).

| Adult males | Adult females | Subadults | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (n = 6, 12, 5) | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 11.4 ± 6.4 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | |||||||||||

| 6.0–9.0 | 5.0–22.0 | 3.0–5.0 | ||||||||||||

| Hair | Cortisol (n = 6, 12, 5) | 11.3 ± 3.2 | 12.5 ± 2.9 | 14.2 ± 3.5 | ||||||||||

| 6.5 – 15.0 | 8.0–16.7 | 9.7–18.7 | ||||||||||||

| Whole blood | TT3 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | ||||||||||

| 0.7–1.3 | 0.4–1.6 | 0.2–1.3 | ||||||||||||

| TT4 (n = 1, 10, 2) | 1.4 ± 0 | 17.5 ± 11.3 | 23.4 ± 1.2 | |||||||||||

| 1.4 | 3.3–36.6 | 22.0–24.7 | ||||||||||||

| Subcutaneous adipose tissue | PCB congeners | CB-31/28 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 34.0 ± 19.8 | 28.0 ± 19.8 | 49.2 ± 21.8 | |||||||||

| 0.9–62.4 | 3.7–54.7 | 19.7–71.4 | ||||||||||||

| CB -52 (n = 5, 11, 5) | 8.5 ± 2.8 | 10.6 ± 2.8 | 11.4 ± 4.4 | |||||||||||

| 4.9–12.1 | 6.6–15.6 | 6.2–18.2 | ||||||||||||

| CB -60 (n = 3, 10, 4) | 5.7 ± 2.6 | 7.9 ± 7.1 | 6.0 ± 3.9 | |||||||||||

| 2.8–7.9 | 2.5–27.0 | 2.7–11.6 | ||||||||||||

| CB -64/71 (n = 5, 9, 4) | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 4.1 | 6.4 ± 4.4 | |||||||||||

| 1.7–4.9 | 0.1–11.9 | 3.0–12.8 | ||||||||||||

| CB -66/95 (n = 2, 8, 3) | 4.3 ± 4.6 | 10.4 ± 6.6 | 6.2 ± 1.9 | |||||||||||

| 1.0–7.5 | 1.9–20.3 | 4.6–8.3 | ||||||||||||

| CB -74 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 14.6 ± 7.3 | 24.8 ± 19.9 | 43.1± 30.7 | |||||||||||

| 6.4–23.0 | 3.7–65.5 | 8.7–86.4 | ||||||||||||

| CB -97 (n = 3, 9, 5) | 6.7 ± 4.7 | 8.1 ± 6.4 | 3.4 ± 1.2 | |||||||||||

| 2.3–11.7 | 0.1–17.5 | 2.1–4.7 | ||||||||||||

| CB -99 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 524.0 ± 102.0 | 386.0 ± 172.0 | 422.6 ± 140.6 | |||||||||||

| 426.2–676.5 | 65.8–601.5 | 315.6–663.1 | ||||||||||||

| CB -101/84 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 19.3 ± 5.9 | 15.4 ± 8.1 | 27.5 ± 18.2 | |||||||||||

| 12.5–27.8 | 2.2–32.5 | 18.8–60.0 | ||||||||||||

| CB -118 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 96.6 ± 52.2 | 64.3 ± 39.2 | 96.4 ± 34.2 | |||||||||||

| 26.2–153.8 | 16.0–147.2 | 44.9–133.4 | ||||||||||||

| CB -128 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 16.6 ± 3.4 | 15.2 ± 17.0 | 18.6 ± 8.2 | |||||||||||

| 11.6–20.2 | 2.0–65.1 | 10.9–32.3 | ||||||||||||

| CB -129/178 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 15.1 ± 6.6 | 7.2 ± 4.0 | 8.3 ± 1.9 | |||||||||||

| 2.7–21.0 | 1.4–16.2 | 6.2–11.3 | ||||||||||||

| CB -138 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 835.2 ± 264.8 | 586.3 ± 213.1 | 701.7 ± 204.1 | |||||||||||

| 401.2–1149.2 | 128.4–874.7 | 409.5–942.1 | ||||||||||||

| CB -146 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 99.3 ± 41.5 | 59.1 ± 21.6 | 78.0 ± 20.9 | |||||||||||

| 29.6–153.5 | 15.8–87.5 | 50.1–98.4 | ||||||||||||

| CB -151 (n = 2, 6, 3) | 2.7 ± 3.2 | 3.3 ± 3.2 | 5.7 ± 3.8 | |||||||||||

| 0.5–5.0 | 0.5–7.8 | 1.7–9.2 | ||||||||||||

| CB -153 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 2659.3 ± 514.7 | 1674.5 ± 776.5 | 1866.3 ± 547.8 | |||||||||||

| 2023.1–3486.8 | 303.8–2993.3 | 1163.0–2478.9 | ||||||||||||

| CB -170/190 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 1091.7 ± 322.8 | 679.0 ± 359.8 | 635.9 ± 198.2 | |||||||||||

| 802.0–1681.8 | 86.1–1337.3 | 432.6–931.7 | ||||||||||||

| CB -171/202/156 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 64.3 ± 15.2 | 47.2 ± 23.8 | 46.3 ± 13.1 | |||||||||||

| 35.6–78.6 | 5.6–87.2 | 36.0–68.5 | ||||||||||||

| CB -172 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 16.2 ± 7.7 | 7.9 ± 3.1 | 9.2 ± 3.7 | |||||||||||

| 2.9–25.9 | 1.4–12.3 | 5.2–13.4 | ||||||||||||

| CB -177 (n = 5, 10, 5) | 7.0 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 1.9 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | |||||||||||

| 5.0–9.8 | 1.8–8.1 | 2.4–6.1 | ||||||||||||

| CB -180 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 1996.2 ± 690.2 | 1241.9 ± 678.0 | 1149.3 ± 380.0 | |||||||||||

| 1433.7–3289.0 | 171.4–2600.3 | 787.7–1765.3 | ||||||||||||

| CB -182/187 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 69.9 ± 31.3 | 38.3 ± 17.8 | 47.3 ± 11.2 | |||||||||||

| 11.7–98.5 | 11.5–66.5 | 29.7–60.8 | ||||||||||||

| CB -183 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 85.9 ± 35.1 | 49.3 ± 18.7 | 55.6 ± 18.8 | |||||||||||

| 27.8–132.6 | 11.3–67.6 | 29.7–80.4 | ||||||||||||

| CB -194 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 328.8 ± 124.1 | 305.2 ± 227.8 | 168.2 ± 60.4 | |||||||||||

| 196.4–546.3 | 42.8–923.2 | 107.1–242.4 | ||||||||||||

| CB -195 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 12.4 ± 6.5 | 7.2 ± 3.2 | 7.8 ± 3.1 | |||||||||||

| 3.6–23.4 | 1.3–11.4 | 3.2–10.6 | ||||||||||||

| CB -200 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 56.4 ± 8.2 | 40.4 ± 23.4 | 39.0 ± 14.2 | |||||||||||

| 44.6–67.4 | 3.3–81.7 | 27.7–63.8 | ||||||||||||

| CB -201 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 49.6 ± 31.6 | 17.6 ± 7.5 | 20.0 ± 8.1 | |||||||||||

| 5.9–102.4 | 3.4–27.8 | 9.2–30.2 | ||||||||||||

| CB -203/196 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 37.1 ± 20.6 | 18.3 ± 7.6 | 20.7 ± 8.4 | |||||||||||

| 7.7–71.6 | 3.9–26.2 | 9.0–30.7 | ||||||||||||

| CB -206 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 82.6 ± 37.1 | 74.6 ± 68.8 | 38.1 ± 17.0 | |||||||||||

| 37.7–145.9 | 10.3–257.2 | 15.3–58.4 | ||||||||||||

| PBDE congeners | BDE-47 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 29.0 ± 7.3 | 34.7 ± 11.2 | 36.3 ± 7.3 | ||||||||||

| 19.4–39.4 | 19.2–51.5 | 31.1–48.9 | ||||||||||||

| BDE-99 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 37.2 ± 64.1 | 21.2 ± 40.2 | 7.8 ± 6.3 | |||||||||||

| 3.4–166.7 | 1.6–112.0 | 4.6–19.0 | ||||||||||||

| BDE-100 (n = 6, 11, 5) | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | |||||||||||

| 0.8–2.1 | 0.7–2.4 | 0.8–1.9 | ||||||||||||

| BDE-153 (n = 6, 12, 5) | 21.9 ± 10.3 | 13.7 ± 7.3 | 12.2 ± 4.8 | |||||||||||

| 3.2–33.7 | 3.1–29.1 | 6.5–18.6 | ||||||||||||

| HCH | α-HCH (n = 6, 12, 5) | 35.3 ± 15.9 | 49.2 ± 24.7 | 48.2 ± 6.5 | ||||||||||

| 15.9–58.4 | 5.0–82.8 | 41.6–55.1 | ||||||||||||

| β-HCH (n = 6, 12, 5) | 150.2 ± 33.7 | 141.8 ± 189.8 | 122.6 ± 46.6 | |||||||||||

| 110.6–185.5 | 9.0–734.7 | 86.0–204.3 | ||||||||||||

| CB | HCB (n = 6, 12, 5) | 65.1 ± 29.0 | 76.3 ± 66.1 | 82.3 ± 32.6 | ||||||||||

| 33.8–105.7 | 8.8–226.8 | 61.3–139.4 | ||||||||||||

| TCB (n = 5, 5, 3) | 33.1 ± 6.4 | 29.1 ± 5.4 | 44.8 ± 17.4 | |||||||||||

| 23.3–40.2 | 23.4–35.8 | 33.4–64.8 | ||||||||||||

| QCB (n = 5, 12, 5) | 16.9 ± 4.1 | 11.4 ± 6.5 | 18.6 ± 7.2 | |||||||||||

| 10.7–21.0 | 2.2–20.5 | 10.7–29.9 | ||||||||||||

| DDT | p,p′-DDT (n = 6, 12, 5) | 44.7 ± 26.1 | 33.5 ± 26.8 | 39.8 ± 12.8 | ||||||||||

| 9.7–73.1 | 5.4–92.0 | 22.2–54.2 | ||||||||||||

| p,p′-DDE (n = 6, 12, 5) | 426.0 ± 335.8 | 332.2 ± 225.3 | 449.7 ± 140.9 | |||||||||||

| 102.9–1019.3 | 66.6–830.0 | 277.8–598.9 | ||||||||||||

| p,p′-DDD (n = 6, 12, 5) | 13.0 ± 7.7 | 10.8 ± 10.2 | 11.1 ± 3.2 | |||||||||||

| 3.4–21.4 | 1.4–37.7 | 7.4–14.6 | ||||||||||||

| CHL | Oxychlordane (n = 6, 12, 5) | 832.5 ± 390.7 | 1050.0 ± 435.9 | 1055.0 ± 434.7 | ||||||||||

| 481.2–1597.7 | 170.5–1551.5 | 736.3–1807.4 | ||||||||||||

| cis-chlordane (n = 6, 12, 5) | 333.8 ± 140.2 | 319.5 ± 127.1 | 340.1 ± 129.6 | |||||||||||

| 190.4–594.8 | 72.5–465.3 | 199.6–546.1 | ||||||||||||

| trans-chlordane (n = 5, 11, 4) | 3.1 ± 3.3 | 13.7 ± 15.0 | 3.5 ± 3.9 | |||||||||||

| 0.8–8.9 | 1.0–44.0 | 1.0–9.1 | ||||||||||||

| cis-nonachlor (n = 6, 12, 5) | 13.9 ± 8.0 | 10.1 ± 5.7 | 11.7 ± 5.5 | |||||||||||

| 3.3–25.0 | 3.2–19.2 | 6.2–18.2 | ||||||||||||

| trans-nonachlor (n = 6, 12, 5) | 280.3 ± 158.0 | 204.2 ± 91.7 | 251.5 ± 86.8 | |||||||||||

| 90.6–478.5 | 68.7–368.2 | 120.2–358.1 | ||||||||||||

| heptachlor epoxide (n = 6, 12, 5) | 145.0 ± 56.8 | 150.2 ± 58.3 | 156.7 ± 31.2 | |||||||||||

| 71.0–241.5 | 25.5–239.1 | 110.4–197.3 | ||||||||||||

| Dieldrin (n = 6, 12, 5) | 178.8 ± 79.1 | 175.4 ± 67.0 | 213.2 ± 44.7 | |||||||||||

| 112.7–293.7 | 26.0–248.1 | 141.9–259.2 | ||||||||||||

| OCS (n = 6, 12, 5) | 14.1 ± 4.0 | 18.6 ± 14.6 | 15.0 ± 3.8 | |||||||||||

| 8.0–19.8 | 1.4–44.7 | 10.2–19.7 | ||||||||||||

TT3: total T3 (triiodothyronine)

TT4: total T4 (thyroxine)

PCB: polychlorinated biphenyl

PBDE: polybrominated diphenyl ether

HCH, here: α- and β-hexachlorocyclohexane

CB, here: HCB: hexachlorobenzene; TCB: trichlorobenzene; QCB: pentachlorobenzene; DDT, here: DDT: p,p′-DDT: 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl)ethane); p,p′-DDE: 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl)ethylene); p,p′-DDD: 1,1,dichloro-2,2-bis(4-chlorophenyl) ethane)

CHL: chlordane

OCS: octachlorostyrene

PLS modeling of OHCs, THs, and cortisol

The first PLS regression model consisting of Y=cortisol and 58 X-variables (capture date, age, sex, BM, girth, length, lipid content, TT3 and TT4 and 49 contaminants) was significant (one PLS component: R2X=0.16, R2Y=0.51, Q2=0.107). Improvement of the PLS model was done in a stepwise manner with evaluations of validation parameters and permutation analyses for each step. First, all parameters with VIP values < 0.5 were removed (CB-101/84, -52, girth, CB-97, -138, 146, -118, -64/71, -99, QCB, Sex, CB-177, -171/202, BM, and CB-200) due to no or little influence on the model. This step improved the model (one PLS components; R2X=0.20, R2Y=0.50, Q2=0.29), especially the Q2. The model was further improved by a successive removal of three X-variables with the lowest VIP values (HCB, CB-182/187, and OCS). The resulting model (one PLS component; R2X=0.20, R2Y=0.50, Q2=0.30) was evaluated to be the best model. The model’s R2Y and Q2 values were approaching the values that define a good model using biological data; R2Y > 0.7 and Q2 > 0.4 ( Lundstedt et al. 1998). A model with higher validation parameters would be possible to develop by reducing the majority of the X-variables. However, since the aim of this study was to investigate the intricate relationships between contaminants and THs with cortisol, such a radical reduction of parameters in the model would not fully represent the complexity of the data. Hence, the choice was made to use the previously described less reduced but still fully valid model. The significant CV-ANOVA (p = 0.03) and the permutation analyses also confirmed the validity of the model; cortisol intercepts: R2Y= (0.0, 0.31), Q2=(0.0, −0.11).

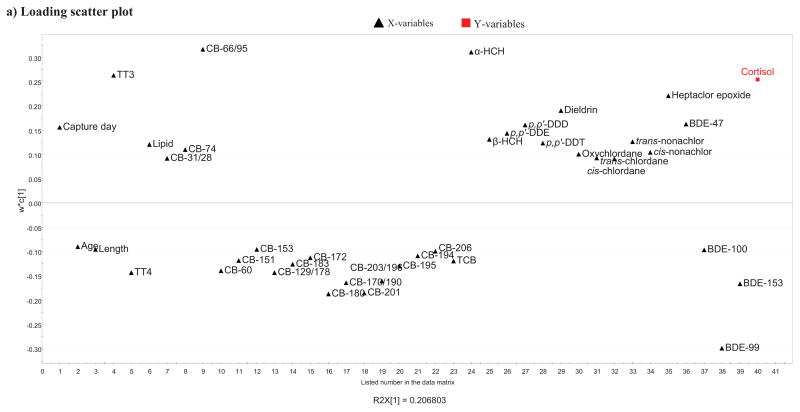

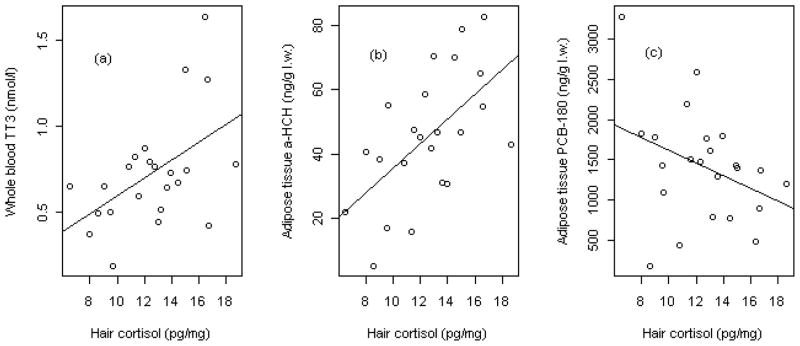

Effects on cortisol concentrations

In the resulting PLS model, the most important contaminant variables (VIP > 1.0) with a negative influence on cortisol levels were particularly BDE-99 (VIP > 1.5), and CB-180, -201, BDE-153 and CB-170/190 (all VIP > 1.0). The most important contaminant variables with a positive influence on cortisol were especially CB-66/95, α-HCH (VIP >1.5), heptachlor epoxide, dieldrin, BDE-47, p,p′-DDD (VIP > 1.0) (Fig. 1a–c). With respect to the influence of biological variables on cortisol, TT3 (VIP > 1.5) appeared to be the only biological variable that significantly influenced cortisol, in a positive manner. The biological variables age, length, TT4, and lipid content had little importance in explaining cortisol levels (Fig. 1b). The variables sex and girth were removed during model improvement due to low VIP values and thus appear to have low influence on cortisol concentration. Spearman’s rank order correlation tests on cortisol vs. the 12 parameters with VIP values > 1.0 (Fig. 1b) showed that there were significant associations between cortisol and TT3 (p = 0.04, rs = 0.42, n = 23) and cortisol and α-HCH (p < 0.01, rs = 0.60, n = 23). In addition, there was a correlation trend between cortisol and CB-180 (p < 0.10, rs = −0.36, n = 23). Scatter plots of the three correlations are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 1.

a) Loading score plot showing loadings of the significant PLS model between Y=cortisol and 58 X-variables (49 individual organohalogens in adipose tissue [ng/g lipid weight], lipid content, girth, length, estimated BM, age, sex, capture day, and circulating TT3 and TT4 levels) of 23 polar bears (Ursus maritimus) including subadult and adult males and females. The PLS model had significant components: R2X=0.2, R2Y=0.5, Q2=0.3, and CV-ANOVA: p=0.03. The loading plot displays the correlation structure of the variables and shows how the X-variables relates to Y. Herein, variable loading of the single PLS component is plotted against their listed number in the data matrix. Thus, this loading plot must only be interpreted vertically. The variables with the highest loading (w*c) above zero have the highest positive influence on Y. The variables with the lowest loading below zero have the highest negative influence on Y. Loadings with value close to zero are unimportant.

b) All bars show variable importance for the projection (VIP) values that summarizes the importance of the variables in explaining the X-matrix and to correlate with Y=cortisol. The error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. VIP ≥ 1 indicates important X-variables (dark grey bars) and the open bars indicate X-variables with 1 > VIP > 0.5. The X-variables that obtained VIP ≤ 0.5 are considered unimportant and not included in the figure.

c) The regression coefficient plot of the PLS model. All bars show regression coefficient (CoeffCS) values of each variable indicating the direction and strength of the relationships between individual X-variables and Y=cortisol. The error bars represent the 95 % confidence intervals. The full bars present CoeffCS values of variables with VIP values ≥1 from Fig. 1b, which indicate high importance for the model.

Please see text for further details.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of the Spearman’s rank order correlation tests conducted on some of the parameters deemed most important according to the PLS model; a) TT3, b) α-HCH, c) CB-180. Please see text for further details.

Discussion

Effects of OHCs on cortisol

OHCs have been shown to affect vertebrate cortisol levels in a range of experimental studies (Nelson & Woodard 1948; Lund et al. 1988; Brandt et al. 1992; Jönsson et al. 1993; Lacroix & Hontela 2003; Jørgensen et al. 2006; Sonne et al. 2008; Zimmer et al. 2009). For Svalbard polar bears there are also correlative studies that support changes in the HPA axes as a function of OHC exposure, as Oskam et al. (2004) found that the sum of pesticides combined with the PCBs and their interactions explained over 25% of the variation in the cortisol concentration in Svalbard polar bear blood plasma.

The BDE congeners found by the current study to have the most significant effects on cortisol levels were congeners -47, -99, and -153. According to Dietz et al. (2007) most prevalent congener in East Greenland polar bears are BDE-47 followed by -153, -99 and -100 in decreasing order together comprising 99.6% of all the PBDEs. This is also substantiated for East Greenland polar bears as reported elsewhere (Gebbink et al. 2008; McKinney et al. 2011). BDE congeners -99 and -47 are some of the PBDEs in the environment as such with the highest known biomagnification capabilities (Kelly et al. 2007). The PCB congener -180, which is one of the most abundant PCB congeners in Svalbard polar bears (Bernhoft et al. 1997; Norstrom et al. 1998; Skaare et al. 2000; Braathen et al. 2004), also had a large influence on cortisol. In addition, the lipophilic pesticide-compunds α-HCH, heptachlor epoxide, dieldrin, and p,p′-DDD also influenced cortisol. BDE-99 was found by the PLS model to play an important role in determining cortisol levels. However, there was no significant correlation between the two when using a Spearman’s rank order correlation test. This could possibly be because BDE-99 plays a large role in combination with other variables, but not alone, which illustrates the complexity of assessing the role of single compounds when working with what is in reality a mixed cocktail of various chemicals. Also noteworthy was that fact that most of the PCB congeners with an influence on cortisol levels were of a highly chlorinated and globular (non-dioxin-like) nature.

Female Greenland sled dogs (Canis familiaris) were exposed to a complex OHC mixture in a controlled study by Sonne et al. (2008), who found blood plasma cortisol levels to be non-significantly higher in the exposed parent generation when comparing with a control group, while no such trend was found in the pups. In wildlife, PCB and DDT metabolites have been suggested to cause elevated cortisol levels in Baltic grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) and ringed seals, which is in accordance with laboratory studies (Bergman & Olsson 1985; AMAP 2004). However, other results are conflicting; Zimmer et al. (2009) recently found low-dose exposure of CB-126 and -153 during fetal and postnatal development to alter stress-induced cortisol levels in goats (Capra aegagrus hircus). Also, in rats fed low levels of toxaphene, DDT, and technical PCB (Aroclor 1254), no hyperplasias were observed, but adrenal glucocorticoid production was inhibited (Young et al. 1973; Mohammed et al. 1985; Byrne et al. 1988). Similarly, Hart et al. (1973) found that a combination of DDD isomers inhibited ACTH-induced steroid production in dogs. Miller et al. (1993), however, reported that technical PCB exposure elevated the basal serum levels of corticosterone in rats, but not the stress-induced rise. Also, chronic exposure of dogs to DDT caused adrenal enlargement but no effects on steroid production (Copeland & Cranmer 1974). HCH isomers have been found to suppress adrenocortical function in female mice (Lahiri & Sircar 1991), which is supported by the in vitro study by Zisterer et al. (1996). In vitro studies also provide conflicting results; for example Song et al. (2008) found only small responses in hormone levels after exposure to various hydroxylated PBDE congeners, whereas a similar study, though with relatively higher exposure concentrations, by He et al. (2008) found that the expression of most steroidgenic genes were upregulated by methoxylated metabolites. Considering the array of varying results presented above, it is clear that more research is needed into how EDCs affect the HPA axis.

Cortisol values in Svalbard polar bear blood plasma were found by Oskam et al. (2004) to overall be negatively related to organochlorine compounds (Σ pesticides as well as Σ PCBs). The authors analyzed a wide range of OCs, but statistical analysis was performed only for the compounds that were found in all the bears. However, of the single compounds, they found α-HCH, oxychlordane, and CB-153, -170, and -180 to have a negative relationship with cortisol values. This is in accordance with our results (Fig. 1c), except with regards to oxychlordane and α-HCH, which we found to be positively correlated with cortisol in the present study. In addition, whereas Oskam et al. (2004) found that the OCs explained approx. 25% of the variation, axillary girth and body mass determined more than 50%, unlike in the present PLS model where such biological factors had a lower importance in explaining the variation in cortisol levels compared to contaminants and TT3. However, it is worth noting that the bears included in the Oskam et al. (2004) study were collected over a much shorter time of year (March-May and August, 1995–1998) than the bears analyzed in the present study (January-May and July-October, 1999–2001). Still, the previously suggested modulation of the polar bear HPA axis was confirmed by the present study.

In Bechshøft et al (Submitted) few relationships were indicated between polar bear adipose OHC compounds and hair cortisol levels using bivariate correlations. In the present study, which included many of the same polar bears, using multivariate regression modeling and including also THs and other biological factors, the HPA axis indeed appear affected by OHCs. Although statistical modeling does not fully explain or prove biological cause-effect relationships, the results herein indicate that contaminants influence cortisol levels both negatively (e.g. BDE-99, -153, CB-170/190, -180, -201) and positively (CB-66/95, BDE-47, α-HCH, heptachlor epoxide, dieldrin and p,p′-DDD). That these relationships were not initially described by univariate associations in Bechshøft et al. (Submitted) demonstrate the importance of including the total mixture of lipophilic contaminants and biological factors when investigating potential effects on cortisol levels. The great advantage of PLS is that influence of all X-variables on the response variable Y is simultaneously modeled in a unidirectional manner (Wold et al. 2001; Umetrics 2008). Also, the results suggest that the association between OHCs and cortisol are in some way linked with the HPT axis, due to the high and positive influence of TT3 on cortisol. This finding is in accordance with previously reported findings in an experimental rodent study where hyperthyroidism is associated with adrenal hyperactivity and significant elevations in corticosterone levels (Johnson et al. 2005). Similar associations between hyperthyroidism and hypercorticism have been reported in human studies (Levin & Daughaday 1955; Peterson & Wuygaarden 1956). Furthermore, Saeb et al. (2010) found both cortisol, T3, and T4 to be elevated in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) after exposure to long-term stress of road transportation, although the study failed to correlate the results and it is therefore unknown whether the correlation between cortisol and TH is significant. A plausible physiological link between THs and cortisol might explain the positive influence of TT3 on cortisol levels. However, the results in the present study could also indicate that the effects of specific OHCs indirectly affect cortisol through their effects on the HPT axis. Several mammal studies have linked thyroid hormone disruption with OHCs (Sørmo et al. 2005; Gutleb et al. 2010). That East Greenland polar bear HPT axis is influenced by OHCs is supported by recent studies conducted by Sonne et al. (2011) and Villanger et al. (2011a). As shown by Sonne et al. (2011), thyroid gland histological lesions in East Greenland polar bears were similar to those of OHC exposed laboratory animals as well as wildlife contaminated animals such as farmed blue foxes (Alopex lagopus) and glaucous gulls (Larus hyperboreus) (Sonne et al. 2009, 2010, 2011). By using PLS modeling, Villanger et al. (2011a) indicated a linkage between TH levels and complex OHC mixtures accumulated in adipose tissue of East Greenland polar bears. These complex relationships probably reflect multiple and overlapping target points of OHCs and their metabolites on the HPT axis such as interference with TH production, protein binding and transport in blood, enzymatic metabolism and excretion or thyroid receptor binding (Gutleb et al. 2010; Letcher et al. 2010; Ucan-Marin et al. 2010; Villanger et al. 2011a and references therein). Indeed, PCB metabolites had completely saturated thyroid hormone transport capacity in blood of Svalbard polar bears (Gutleb et al. 2010). Also the results presented by Skaare et al. (2001) and Braathen et al. (2004) this notion, as the authors found indications that OHCs may affect circulating TH levels in Svalbard polar bears. In addition to this, Villanger et al. (2011b) found disruptive effects of OHCs on thyroid function in white whales (Delphinapterus leucas), a species with relatively high OHC levels in comparison to other marine mammals, including the polar bear (Villanger et al. 2011a,b). In Villanger et al. (2011a) some of same contaminants were associated with increased or decreased TT3 levels in polar bears from East Greenland as were found to influence cortisol in the present study, such as BDE-99 and -153, α-HCH, and p,p′-DDD.

Health implications

Neither hair cortisol nor blood thyroid concentration is apparently influenced by the acute stress of hunting and/or tagging (Bechshøft et al. 2011; Villanger et al. 2011b). Hence it can be assumed that the concentrations presented here are instead related to chronic stressors. Little is known about the timing of molt and growth of new hair in polar bears. According to Pedersen (1945) molt in polar bears is between mid May and mid December, whereas the new winter fur is produced in September-October. Thus cortisol is likely imbedded in hair during few fall months thus representing an overall fall health/stress status of the bear, as the animal renews its fur. It would be of interest to measure TH in hair too, if possible, correlating the two matrices over the same period of time.

Given the multiple functions and the requirements of cortisol and THs during development, disruption of these hormone systems could negatively impact individual as well as population health. Neurocognitive deficits in young polar bears due to OHC-induced TH disruption in utero or postnatal juvenile stages (Porterfield 2000; Howdeshell 2002; Branchi et al. 2003; Zoeller & Crofton 2005; Nakajima et al. 2006) could reduce their ability to learn, and thus affect their ability to find and hunt prey, change behaviour (e.g. mating) and ultimately affect reproduction and survival. Furthermore, disturbances of the TH system could also reduce an individual’s ability to thermoregulate and to adjust metabolic rate in relation to external factors such as temperature, ice-cover, food availability (fasting), migratory needs or other shifts in energy requirements. Also sexual development and fertility may be affected through OHC-induced TH disruption (Cooke et al. 2004; Kuriyama et al. 2005). Cortisol, like THs, is also involved in a wide range of vital functions; metabolism, growth, development, and responses to stress influencing the physiology and endocrinology of the reproductive and immune systems (Moberg 1991; Dobson & Smith 2000; Sjaastad et al. 2003; von Borell et al. 2007; Schmidt & Soma 2008). Hence disturbances of the HPA axis could mean bears that were more prone to disease, had lower reproductive rates, and which were sub-optimally equipped to handle fluctuations in prey availability.

Conclusion

Cortisol levels in East Greenland polar bears were significantly related to a range of organohalogen contaminants. In addition, the present study linked TT3 and cortisol, thus indicating a complex relationship between chronic physiological stress and thyroid hormone levels. A wider study incorporating a larger number of polar bears is therefore recommended. This would help clarify the relationship between hormones and contaminants further, as the increased sample size would allow for separate analysis of the different sex/age groups. The endocrine disrupting abilities of many contaminants are of great concern (Jenssen 2006; Sonne 2010; Letcher et al. 2010) and further knowledge of their function and dynamics is needed.

Highlights.

Cortisol was measured in hair of East Greenland polar bears.

The relationship with thyroid hormones and contaminant levels was investigated.

Results indicate the HPA axis to be affected by contaminants.

The association between contaminants and cortisol may be linked with the HPT axis.

Acknowledgments

Jonas Brønlund and local hunters are acknowledged for organizing the sampling in East Greenland. We also thank Rita R. Fjeldberg, Grethe S. Eggen and Jenny Bytingsvik (NTNU) for assistance during thyroid hormone analysis and data evaluation. Financial support was provided by the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, the Danish Cooperation for Environment in the Arctic, and the Commission for Scientific Research in Greenland, Norwegian Research Council (IPY project BearHealth) and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). The hair cortisol assays were supported by US NIH grants RR11122 to MAN and RR00168 to the New England Primate Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdelouahab N, Mergler D, Takser L, Vanier C, St-Jean M, Baldwin M, Spear PA, Chan HM. Gender differences in the effects of organochlorines, mercury, and lead on thyroid hormone levels in lakeside communities of Quebec (Canada) Environmental Research. 2008;107:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMAP (Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme) AMAP assessment 2002: persistent organic pollutants in the Arctic. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme; Oslo: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bechshøft TØ, Sonne C, Dietz R, Born EW, Novak MA, Henchey E, Meyer JS. Cortisol levels in hair of East Greenland polar bears. Science of the Total Environment. 2011;409:831–834. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechshøft TØ, Rigét FF, Sonne C, Letcher RJ, Muir DCG, Novak M, Henchey E, Meyer JS, Eulaers I, Jaspers VLB, Covaci A, Dietz R. Measuring environmental stress in East Greenland polar bears, 1892–2009: what does hair cortisol tell us? Submitted to Environment International. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.04.005. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman A, Olsson M. Pathology of Baltic grey seal and ringed seal females with special reference to adrenocortical hyperplasia: Is environmental pollution the cause of a widely distributed disease syndrome? Finnish Game Research. 1985;44:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhoft A, Wiig Ø, Skaare JU. Organochlorines in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) at Svalbard. Environmental Pollution. 1997;95:159–175. doi: 10.1016/s0269-7491(96)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braathen M, Derocher AE, Wiig Ø, Sørmo EG, Lie E, Skaare JU, Jenssen BM. Relationships between PCBs and thyroid hormones and retinol in female and male polar bears. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112:826–833. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchi I, Capone F, Alleva E, Costa LG. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers: neurobehavioral effects following developmental exposure. Neurotoxicology. 2003;24:449–462. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt I, Jonsson CJ, Lund BO. Comparative studies on adrenocorticolytic DDT metabolites. Ambio. 1992;21:602–605. [Google Scholar]

- Bubenik GA, Brown RD. Seasonal levels of cortisol triiodothyronine and thyroxine in male axis deer. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 1989;92:499–503. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(89)90356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JJ, Carbone JP, Pepe MG. Suppression of serum adrenal cortex hormones by low-dose polychlorobiphenyl or polybromobiphenyl treatments. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 1988;17:47–53. doi: 10.1007/BF01055153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalubinski M, Kowalski ML. Endocrine disruptors – potential modulators of the immune system and allergic response. Allergy. 2006;61:1326–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastain CB, Panciera DL. Hypothyroid diseases. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. 4. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, USA: W. B. Saunders Company; 1995. pp. 1487–1501. chapter 115. [Google Scholar]

- Colborn T, vom Saal FS, Soto AM. Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1993;101:378–84. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke PS, Holsberger DR, Witorsch RJ, Sylvester PW, Meredith JM, Treinen KA, Chapin RE. Thyroid hormone, glucocorticoids, and prolactin at the nexus of physiology, reproduction, and toxicology. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2004;194:309–335. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland MF, Cranmer MF. Effects of o,p′-DDT on the adrenal gland and hepatic microsomal enzyme system in the beagle dog. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1974;27:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(74)90168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corlatti L, Palme R, Frey-Roos F, Hackländer K. Climate clues and glucocorticoids in a free-ranging riparian population of red deer (Corvus elaphus) Folia Zoologica. 2011;60:176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport MD, Tiefenbacher S, Lutz CK, Novak MA, Meyer JS. Analysis of endogenous cortisol concentrations in the hair of rhesus macaques. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2006;147:255–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derocher AE, Wiig Ø. Postnatal growth in body length and mass of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) at Svalbard. Journal of Zoology. 2002;256:343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Derocher AE, Wiig Ø, Andersen M. Diet composition of polar bears in Svalbard and the western Barents Sea. Polar Biology. 2002;25:448–452. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz R, Heide-Jørgensen MP, Teilmann J, Valentin N, Härkönen T. Age determination in European Harbour seals Phoca vitulina L. Sarsia. 1991;76:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz R, Riget F, Sonne C, Letcher RJ, Born EW, Muir DCG. Seasonal and temporal trends in polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides in East Greenland polar bears (Ursus maritimus), 1990–2001. Science of the Total Environment. 2004;331:107–24. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz R, Rigét FF, Sonne C, Muir DCG, Backus S, Born EW, Kirkegaard M, Muir DCG. Age and seasonal variability of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in free-ranging East Greenland polar bears (Ursus maritimus) Environmental Pollution. 2007;146:177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson H, Smith RF. What is stress, and how does it affect reproduction. Animal Reproduction Science. 2000;60–61:743–752. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(00)00080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douyon L, Schteingart DE. Effect of obesity and starvation on thyroid hormone, growth hormone, and cortisol secretion. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. 2002;31:173–189. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(01)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson L, Johansson E, Kettaneh-Wold N. Part I: basic principles and applications. Umeå, Umetrics; 2006. Multi- and megavariate data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson L, Trygg J, Wold S. CV-ANOVA for significance testing of PLS and OPLS (R) models. Journal of Chemometrics. 2008;22:594–600. [Google Scholar]

- Gebbink WA, Sonne C, Dietz R, Kirkegaard M, Riget FF, Born EW, Muir DCG, Letcher RJ. Tissue-specific congener composition of organohalogen and metabolite contaminants in East Greenland polar bears (Ursus maritimus) Environmental Pollution. 2008;152:621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geris KL, Berghman LR, Kuhn ER, Darras VM. The drop in plasma thyrotropin concentrations in fasted chickens is caused by an action at the level of the hypothalamus: role of corticosterone. Domestic Animal Endocrinology. 1999;16:231–237. doi: 10.1016/s0739-7240(99)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gochfeld M. Framework for gender differences in human and animal toxicology. Environmental Research. 2007;104:4–21. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutleb AC, Cenijn P, van Velzen M, Lie E, Ropstad E, Skaare JU, Malmberg T, Bergman Å, Gabrielsen GW, Legler J. In vitro assay shows that PCB metabolites completely saturate thyroid hormone transport capacity in blood of wild polar bears (Ursus maritimus) Environmental Science & Technology. 2010;44:3149–3154. doi: 10.1021/es903029j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haave M, Ropstad E, Derocher AE, Lie E, Dahl E, Wiig Ø, Skaare JU, Jenssen BM. Polychlorinated biphenyls and reproductive hormones in female polar bears at Svalbard. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2003;111:431–436. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley ME. Thyroid hormones. In: Hadley ME, editor. Endocrinology. 4. Chapter 13. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1996. pp. 290–337. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin HJ, Guillette LJ., Jr Embryos as targets of endocrine disrupting contaminants in wildlife. Birth Defects Research (Part C) 2011;93:19–33. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart MM, Reagan RL, Adamson RH. The effect of isomers of the DDD on the ACTH-induced steroid output, histology and ultrastructure of the dog adrenal cortex. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1973;24:101–113. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(73)90185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Murphy MB, Yu RMK, Lam MHW, Hecker M, Giesy JP, Wu RSS, Lam PKS. Effects of 20 PBDE metabolites on steroidogenesis in the H295R cell line. Toxicology Letters. 2008;176:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howdeshell KL. A model of the development of the brain as a construct of the thyroid system. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;110(S3):337–348. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen BM. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and climate change: A worst-case combination Arctic marine mammals and seabirds? Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006;114(S1):76–80. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen BM, Aarnes JB, Murvoll KM, Herzke D, Nygard T. Fluctuating wing asymmetry and hepatic concentrations of persistent organic pollutants are associated in European shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) chicks. Science of the Total Environment. 2010;408:578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen BM, Skaare JU, Ekker M, Vongraven D, Silverstone M. Blood sampling as a nondestructive method for monitoring levels and effects of organochlorines (PCB and DDT) in seals. Chemosphere. 1994;28:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Kamilaris TC, Calogero AE, Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Experimentally-induced hyperthyroidism is associated with activation of the rat hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2005;153:177–185. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson CJ, Lund BO, Brandt I. Adrenocorticolytic DDTmetabolites: studies in mink, Mustela vison and otter, Lutra lutra. Ecotoxicology. 1993;2:41–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00058213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen EH, Vijayan MM, Killie J-EA, Aluru N, Aas-Hansen Ø, Maule A. Toxicokinetics and effects of PCBs in Arctic fish: a review of studies on Arctic charr. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health A. 2006;69:37–52. doi: 10.1080/15287390500259053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Ikonomou MG, Blair JD, Morin AE, Gobas FAPC. Food web–specific biomagnification of persistent organic pollutants. Science. 2007;317:236–240. doi: 10.1126/science.1138275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaysky AS, Romano MD, Piatt JF, Wingfield JC, Kikuchi M. The adrenocortical response of tufted puffin chicks to nutritional deficits. Hormones and Behavior. 2005;47:606–619. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren L, Mokady O, Karaskov T, Klein J, Koren G, Geffen E. A novel method using hair for determining hormonal levels in wildlife. Animal Behaviour. 2002;63:403–406. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama SN, Talsness CE, Grote K, Chahoud I. Developmental exposure to low-dose PBDE-99: effects on male fertility and neurobehavior in rat offspring. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113:149–154. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix M, Hontela A. The organochlorine o,p′-DDD disrupts the adrenal steroidogenic signaling pathway in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2003;190:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri P, Sircar S. Suppression of adrenocortical function in female mice by lindane (γ-HCH) Toxicology. 1991;66:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(91)90179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letcher RJ, Bustnes JO, Dietz R, Jenssen BM, Jørgensen EH, Sonne C, Verreault J, Vijayan MM, Gabrielsen GW. Exposure and effects assessment of persistent organohalogen contaminants in arctic wildlife and fish. Science of the Total Environment. 2010;408:2995–3043. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ME, Daughaday WH. The influence of the thyroid on adrenocortical function. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1955;15:1499–1511. doi: 10.1210/jcem-15-12-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund BO, Bergman Å, Brandt I. Metabolic activation and toxicity of a DDT-metabolite, 3- methylsulphonyl-DDE, in the adrenal zona fasciculata in mice. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 1988;65:25–40. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(88)90028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstedt T, Seifert E, Abramo L, Thelin B, Nystrom A, Pettersen J, Bergman R. Experimental design and optimization. Chemometrics and Intelligent Lab Systems. 1998;42:3–40. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RK, Langston VC. Use of corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. In: Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. 4. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, USA: W. B. Saunders Company; 1995. pp. 284–293. chapter 59. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney MA, Letcher RJ, Born EW, Branigan M, Dietz R, Evans TJ, Gabrielsen GW, Peacock E, Sonne C. Flame retardants and legacy contaminants in polar bears from Alaska, Canada, East Greenland and Svalbard, 2005–2008. Environment International. 2011;37:365–374. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNabb FMA. Thyroid hormones. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes JJA. The endocrine disruptors: a major medical challenge. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2002;40:781–788. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB, Gary LE, Jr, Andrews JE, Luebke RW, Smialowicz RJ. Repeated exposure to the polychlorinated biphenyl (Arochlor 1254) elevates the basal serum levels of corticosterone but does not affect the stress-induced rise. Toxicology. 1993;81:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(93)90014-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg GP. How behavioral stress disrupts the endocrine control of reproduction in domestic animals. Journal of Dairy Science. 1991;74:304–311. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed A, Hallberg E, Rydstrom J, Slanina P. Toxaphene: Accumulation in the adrenal cortex and effect on ACTH-stimulated corticosteroid synthesis in the rat. Toxicology Letters. 1985;24:137–143. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(85)90049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir DCG, Backus S, Derocher AE, Dietz R, Evans TJ, Gabrielsen GW, Nagy J, Norstrom RJ, Sonne C, Stirling I, Taylor MK, Letcher RJ. Brominated flame retardants in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from Alaska, the Canadian Arctic, East Greenland, and Svalbard. Environmental Science & Technology. 2006;40:449–455. doi: 10.1021/es051707u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murvoll KM, Skaare JU, Moe B, Anderssen E, Jenssen BM. Spatial trends and associated biological responses of organochlorines and brominated flame retardants in hatchlings of North Atlantic kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 2006;25:1648–1656. doi: 10.1897/05-337r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima S, Saijo Y, Kato S, Sasaki S, Uno K, Kanagami N, Hirakawa H, Hori T, Tobiishi K, Todaka T, Nakamura Y, Yanagiya S, Sengoku Y, Iida T, Sata F, Kishi R. Effects of prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins on mental and motor development in Japanese children at 6 months of age. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006;114:773–778. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AA, Woodard G. Adrenal cortical atrophy and liver damage produced in dogs by feeding 2,2-bis(parachlorophenyl)-1,1-dichloroethane (DDD) Federation of American Societys for Experimental Biology. 1948;7:276–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norstrom RJ, Belikov SE, Born EW, Garner GW, Malone B, Olpinski S, Ramsay MA, Schliebe S, Stirling I, Stishov MS, Taylor MK, Wiig Ø. Chlorinated hydrocarbon contaminants in polar bears from eastern Russia, North America, Greenland, and Svalbard: Biomonitoring of Arctic pollution. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 1998;35:354–367. doi: 10.1007/s002449900387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odermatt A, Gumy C, Atanasov AG, Dzyakanchuk AA. Disruption of glucocorticoid action by environmental chemicals: Potential mechanisms and relevance. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 2006;102:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskam IC, Ropstad E, Lie E, Derocher AE, Wiig O, Dahl E, Larsen S, Skaare JU. Organochlorines affect the steroid hormone cortisol in free-ranging polar bears (Ursus maritimus) at Svalbard, Norway. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, Current Issues. 2004;67:959–977. doi: 10.1080/15287390490443731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen A. Der Eisbär. Aktieselskabet E. Bruun & Co.’s trykkerier; København: 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Peter MCS. The role of thyroid hormones in stress response of fish. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2011;172:198–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RE, Wuygaarden JB. The miscible pool and turnover rate of hydrocortisone in man. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1956;38:552–556. doi: 10.1172/JCI103308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield SP. Thyroidal dysfunction and environmental chemicals — potential impact on brain development. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2000;108(S3):433–438. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanth GK, Divya LM, Sadasivan C. Bisphenol-A can bind to human glucocorticoid receptor as an agonist: an in silico study. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2010;30:769–774. doi: 10.1002/jat.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay MA, Stirling I. Reproductive biology and ecology of female polar bears (Ursus maritimus) Journal of Zoology. 1988;214:601–634. [Google Scholar]

- Rosing-Asvid A, Born EW, Kingsley MCS. Age at sexual maturity of males and timing of the mating season of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in Greenland. Polar Biology. 2002;25:878–883. [Google Scholar]

- Routti H, Arukwe A, Jenssen BM, Letcher RJ, Nyman M, Bäckman C, Gabrielsen GW. Comparative endocrine disruptive effects of contaminants in ringed seals (Phoca hispida) from Svalbard and the Baltic Sea. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part C. 2010;152:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeb M, Baghshani H, Nazifi S, Saeb S. Physiological response of dromedary camels to road transportation in relation to circulating levels of cortisol, thyroid hormones and some serum biochemical parameters. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 2010;42:55–63. doi: 10.1007/s11250-009-9385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandala GM, Sonne-Hansen C, Dietz R, Muir DCG, Valters K, Bennett ER, Born EW, Letcher RJ. Hydroxylated and methyl sulfone PCB metabolites in adipose and whole blood of polar bear (Ursus maritimus) from East Greenland. Science of the Total Environment. 2004;331:125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt KL, Soma KK. Cortisol and corticosterone in the songbird immune and nervous systems: local vs. systemic levels during development. American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2008;295:R103–R110. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00002.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemens. Coat-A-Count Total T3 user manual. Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics; Los Angeles, CA, USA: 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- Siemens. Coat-A-Count Total T4 user manual. Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics; Los Angeles, CA, USA: 2006b. [Google Scholar]

- Sjaastad ØV, Hove K, Sand O. The endocrine system. In: Sjaastad O, Hove K, Sand O, editors. Physiology of domestic animals. Scandinavian Veterinary Press; Oslo: 2003. pp. 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Skaare JU, Bernhoft A, Derocher A, Gabrielsen GW, Goksoyr A, Henriksen E, Larsen HJ, Lie E, Wiig O. Organochlorines in top predators at Svalbard - occurrence, levels and effects. Toxicology Letters. 2000;112:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(99)00256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaare JU, Bernhoft A, Wiig Ø, Norum KR, Haug E, Eide DM, Derocher AE. Relationships between plasma levels of organochlorines, retinol and thyroid hormones from polar bears (Ursus maritimus) at Svalbard. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 2001;62:227–241. doi: 10.1080/009841001459397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song RF, He YH, Murphy MB, Yeung LWY, Yu RMK, Lam MHW, Lam PKS, Hecker M, Giesy JP, Wu RSS, Zhang WB, Sheng GY, Fu JM. Effects of fifteen PBDE metabolites, DE71, DE79 and TBBPA on steroidogenesis in the H295R cell line. Chemosphere. 2008;71:1888–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonne C. Health effects from long-range transported contaminants in Arctic top predators: An integrated review based on studies of polar bears and relevant model species. Environment International. 2010;36:461–491. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonne C, Dietz R, Kirkegaard M, Letcher RJ, Shahmiri S, Andersen S, Moller P, Olsen AK, Jensen AL. Effects of organohalogen pollutants on haematological and urine clinical-chemical parameters in Greenland sledge dogs (Canis familiaris) Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2008;69:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonne C, Iburg T, Leifsson PS, Born EW, Letcher RJ, Dietz R. Thyroid gland lesions in organohalogen contaminated East Greenland polar bears (Ursus maritimus) Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry. 2011;93:789–805. [Google Scholar]

- Sonne C, Verreault J, Gabrielsen GW, Letcher RJ, Leifsson PL, Iburg T. Screening of thyroid gland histology in organohalogen-contaminated glaucous gulls (Larus hyperboreus) from the Norwegian Arctic. Toxicological and Environmental Chemistry. 2010;92:1705–1713. [Google Scholar]

- Sonne C, Wolkers H, Leifsson PS, Iburg T, Jenssen BM, Fuglei E, Ahlstrøm Ø, Dietz R, Kirkegaard M, Muir DCG, Jørgensen EH. Chronic dietary exposure to environmental organochlorine contaminants induces thyroid lesions in Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus) Environmental Research. 2009;109:702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørmo EG, Jüssi I, Jüssi M, Braathen M, Skaare JU, Jenssen BM. Thyroid hormone status in gray seal (Halichoerus grypus) pups from the Baltic Sea and the Atlantic Ocean in relation to organochlorine pollutants. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 2005;24:610–616. doi: 10.1897/04-017r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryland M, Brun E, Derocher AE, Arnemo JM, Kierulf P, Ølberg RA, Wiig Ø. Plasma biochemical values from apparently healthy free-ranging polar bears from Svalbard. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 2002;38:566–575. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-38.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ucan-Marin F, Arukwe A, Mortensen AS, Gabrielsen GW, Letcher RJ. Recombinant albumin and transthyretin transport proteins from two gull species and human: chlorinated and brominated contaminant binding and thyroid hormones. Environmental Science and Technology. 2010;44:497–504. doi: 10.1021/es902691u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umetrics. [Accessed 19 June 2011];User guide to Simca-P+. Version 12. 2008 [Online]. Available: http://www.umetrics.com.

- Verboven N, Verreault J, Letcher RJ, Gabrielsen GW, Evans NP. Arenocortical function of Arctic-breeding glaucous gulls in relation to persistent organic pollutants. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2010;166:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verreault J, Muir DCG, Norstrom RJ, Stirling I, Fisk AT, Gabrielsen GW, Derocher AE, Evans TJ, Dietz R, Sonne C, Sandala GM, Gebbink W, Riget FF, Born EW, Taylor MK, Nagy J, Letcher RJ. Chlorinated hydrocarbon contaminants and metabolites in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from Alaska, Canada, East Greenland, and Svalbard: 1996–2002. Science of the Total Environment. 2005;351–352:369–390. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanger GD, Jenssen BM, Fjeldberg RR, Letcher RJ, Muir DCG, Kirkegaard M, Sonne C, Dietz R. Exposure to mixtures of organohalogen contaminants and associative interactions with thyroid hormones in East Greenland polar bears (Ursus maritimus) Environment International. 2011a;37:694–708. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanger GD, Lydersen C, Kovacs KM, Lie E, Skaare JU, Jenssen BM. Disruptive effects of organohalogen contaminants on thyroid function in white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) from Svalbard. Science of the Total Environment. 2011b;409:2511–2524. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Borell E, Dobson H, Prunier A. Stress, behaviour and reproductive performance in female cattle and pigs. Hormones and Behavior. 2007;52:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos JG, Dybing E, Greim HA, Ladefoged O, Lambré C, Tarazona JV, Brandt I, Vethaak AD. Health effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on wildlife, with special reference to the European situation. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2000;30:71–133. doi: 10.1080/10408440091159176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walpita CN, Grommen SVH, Darras VM, Van der Geyten The influence of stress on thyroid hormone production and peripheral deiodination in the Nile tilapia. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2007;152:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wold S, Sjostrom M, Eriksson L. PLS-regression: a basic tool of chemometrics. Chemometrics and Intelligent Lab Systems. 2001;58:109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Young RB, Bryson MJ, Sweat ML, Street JC. Complexing of DDT and o,p′-DDD with adrenal cytochrome P-450 hydroxylating systems. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 1973;4:585–591. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(73)90033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer KE, Gutleb AC, Lyche JL, Dahl E, Oskam IC, Krogenæs A, Skaare JU, Ropstad E. Altered Stress-Induced Cortisol Levels in Goats Exposed to Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB 126 and PCB 153) During Fetal and Postnatal Development. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 2009;72:164–172. doi: 10.1080/15287390802539004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisterer DM, Moynagh PN, Williams DC. Hexachlorocyclohexanes inhibit steroidgenesis in Y1 cells. Absence of correlation with binding to the peripheral-type benzodiazepine binding site. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51:1303–1308. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller RT, Crofton KM. Mode of action: developmental thyroid hormone insufficiency - neurological abnormalities resulting from exposure to propylthiouracil. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2005;35:771–781. doi: 10.1080/10408440591007313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller RT, Tan SW, Tyl RW. General background on the hypothalamic–pituitary– thyroid (HPT) axis. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2007;37:11–53. doi: 10.1080/10408440601123446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]