Abstract

Purpose

To determine corneal sensitivity and evaluate corneal nerves before and after keratoplasty for Fuchs endothelial dystrophy.

Methods

Central corneal sensitivity, measured by using a Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometer in 69 eyes before and after different keratoplasty procedures for Fuchs dystrophy, was compared to that of 35 age-matched normal corneas. Corneal nerves were qualitatively examined by confocal microscopy in 42 eyes before and after Descemet-stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK).

Results

Corneal sensitivity in Fuchs dystrophy (4.61 ± 1.42 cm) was lower than that of age-matched controls (5.74 ± 0.48 cm, p<0.001). Sensitivity decreased by 1 month after DSEK (2.98 ± 2.01 cm, p<0.001), returned to preoperative sensitivity by 24 months (4.50 ± 1.63 cm, n=33, p=0.99), but remained lower than controls at 36 months (4.50 ± 1.48 cm, n=15, p<0.001). Sensitivity at 36 months after penetrating keratoplasty (1.46 ± 1.98 cm) remained decreased compared to preoperative sensitivity (p<0.001). Subbasal nerves appeared sparse with abnormal branching before and through 36 months after DSEK. Sensitivity was lower in corneas without visible subbasal nerves by confocal microscopy at 12 months after DSEK (p<0.005) than in corneas with visible nerves. Stromal nerves were frequently tortuous and formed loops in Fuchs dystrophy, and this appearance persisted in some eyes at 36 months after DSEK.

Conclusions

Corneal sensitivity is decreased in Fuchs dystrophy compared to normal and remains subnormal even at 3 years after endothelial keratoplasty. Decreased sensitivity is likely to be related to loss of subbasal nerves and abnormal nerve morphology, which persist after endothelial keratoplasty.

Keywords: corneal sensitivity, corneal nerves, Fuchs dystrophy, confocal microscopy

INTRODUCTION

Fuchs endothelial dystrophy is accepted to be a primary disorder of the corneal endothelium characterized by the formation of guttae on Descemet membrane and corneal edema from endothelial dysfunction. In advanced cases, chronic corneal edema results in anterior corneal pathologic changes that include subepithelial fibrosis,1 increased anterior corneal haze,2,3 and anterior keratocyte depletion.4 Without the aid of slit-lamp biomicroscopy, Fuchs’ original description of the disease was that of an anterior corneal dystrophy,5 presumably because the cases he described were representative of the most advanced stages of the disease. With current imaging techniques, anterior corneal changes are, in fact, visible in corneas with Fuchs dystrophy at earlier stages than described by Fuchs. These anterior corneal changes were of little importance when penetrating keratoplasty (PK) was the surgical treatment of choice because the full-thickness cornea was excised and replaced. However, in the current era of endothelial keratoplasty (EK), which retains the host cornea, determining residual anterior corneal changes has become important for understanding the repair of the anterior cornea and how this affects visual outcomes.2,4,6

Interactions between epithelial, stromal and neural cells of the anterior cornea are critical for maintaining the structure of the anterior cornea, and the health of the ocular surface for good vision. The anterior corneal surface is the strongest refracting surface of the eye, and irregularities of the anterior surface can degrade vision; indeed, anterior corneal irregularities are associated with poor visual outcomes after EK.7 Normal corneas are densely innervated by branches of the trigeminal nerve; in addition to providing sensation, the corneal nerves presumably supply neurotrophic factors to the epithelium, and might also influence keratocytes.8,9 Therefore, corneal nerves might have a role in maintaining the integrity of the anterior cornea, including the regularity and transparency of the epithelial-stromal boundary. Little is known about the corneal nerves in Fuchs dystrophy, and especially after EK, when they might be important for repairing the anterior cornea. The goal of this study was to assess corneal innervation in Fuchs dystrophy by examining corneal sensitivity and nerve morphology. In addition, we investigated the effect of EK, and thus the restoration of endothelial function, on corneal sensation and nerve morphology through three postoperative years, and compared this to the effect of PK.

METHODS

Subjects

Patients requiring keratoplasty for Fuchs endothelial dystrophy were recruited from the cornea service at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, to two consecutive, prospective studies. The first study was a randomized controlled trial of PK versus deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty (DLEK) for endothelial dysfunction, with all subjects enrolled between 2003 and 20063; only data from subjects with a recipient diagnosis of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy are included in the present report. The second study was a prospective, observational study of Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK), with subjects enrolled after 20062; all subjects had Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. The inclusion, exclusion and randomization criteria for the studies have been previously reported.2,3 Inclusion criteria for the two studies were identical, except that best-corrected visual acuity at enrollment for the randomized trial was 20/40 or worse, whereas there was no entrance visual acuity criterion for the DSEK study. All subjects in both studies were either pseudophakic or had a cataract requiring extraction; patients were excluded if they had central corneal scarring unrelated to Fuchs dystrophy, a filtering bleb or uncontrolled glaucoma, a history of herpetic or other neurotrophic keratitis, or diabetes.

Age-matched subjects with normal corneas were recruited as controls for corneal sensitivity. Controls had no history of herpetic or neurotrophic disease, no history of previous intraocular surgery, and were not using topical ophthalmic medications. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study after explaining the nature and possible consequences of the study. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Surgical procedures

The surgical procedures and postoperative treatment regimen have been described previously.2,3,10,11 All PKs had a recipient diameter of 7.5 or 7.75 mm (mean, 7.55 mm) with the donor secured to the host by using a double-running suture technique. DLEK was performed through a superior 9 to 10 mm scleral tunnel incision that was initiated at a depth of 350 µm. DSEK was performed through a 5 to 6 mm temporal scleral tunnel incision. In procedures combined with cataract surgery, the cataract was extracted through the keratoplasty incision for PK and DSEK, and through a separate clear corneal incision when combined with DLEK. Postoperatively, all eyes were treated with a topical antibiotic for 7 days or until epithelialization was complete, and with topical prednisolone acetate 1% four times daily, typically tapering to once daily by 6 months postoperative.

Outcome measures

The diagnosis of Fuchs dystrophy was confirmed by the presence of guttae and stromal edema with slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Central corneal thickness was measured by using an ultrasonic pachometer (DGH 1000; DGH Technologies, Frazer, PA).

Corneal sensitivity was examined before and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after keratoplasty in the subjects with Fuchs dystrophy, and on one occasion in controls. Sensitivity was measured by using a Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometer12 (Luneau Ophtalmologie, Chartres, France), which had a 0.12 mm-diameter nylon filament with lengths ranging from 0 to 6 cm. Sensitivity was assessed in the center of the cornea by decreasing the length of the filament in 0.5 cm steps until the subject felt the filament touch the cornea.

Central corneal subbasal and stromal nerves were assessed in corneas with Fuchs dystrophy before and after DSEK by using confocal microscopy in vivo (ConfoScan 4 with z-ring, Nidek Technologies, Greensboro, NC). The examination technique has been described in detail previously.13 Confocal images were qualitatively reviewed by two independent observers (YA and SVP) for the presence of nerves and their morphology.

Statistical analysis

Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometry was reported as filament length (cm) and also converted to pressure (g/mm2) against the cornea by using a conversion table provided by the manufacturer (6 cm corresponded to 0.4 g/mm2, and 0.5 cm corresponded to 15.9 g/mm2). Sensitivity in Fuchs dystrophy was compared to that in controls by using generalized estimating equation models to account for possible correlation between fellow eyes of the same subject.14 Generalized estimating equation models were also used to compare preoperative sensitivity to postoperative sensitivity, and to compare the change in sensitivity between preoperative and 1 month across treatments. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons by using the Bonferroni technique, and p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Post-hoc minimum detectable differences (MDDs) were calculated for non-significant differences (α=0.05, β=0.20).

Quantitative analysis of stromal and subbasal nerve densities from confocal images was not possible in many corneas because of corneal haze that might have prevented visualization of nerves. Thus, the morphology of nerves was assessed qualitatively before, and at 12, 24 and 36 months after DSEK.

RESULTS

Subjects

Sixty-nine corneas of 61 patients with Fuchs dystrophy were examined prior to keratoplasty; mean recipient age was 69 ± 10 years (± standard deviation; range, 47–87 years; Table 1). All corneas had guttae and stromal edema; epithelial edema or bullae were evident in 6 eyes at the time of examination. Central corneal thickness was 661 ± 50 µm (range, 535 to 779 µm). Nineteen of the 69 eyes (27%) had received previous ocular surgery, cataract surgery by phacoemulsification in all cases (Table 1). No eye was treated with topical ocular hypotensive agents before keratoplasty, whereas 6 eyes (9%) received topical ocular hypotensive treatment (beta-blocker in 5 of these eyes) for an extended period after keratoplasty (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number and age of subjects within the keratoplasty treatment groups.

| Treatment | Number of eyes (subjects) |

Subject age (years) Mean ± SD (Range) |

Number of pseudophakic eyes prior to keratoplastya (%) |

Number of eyes that received postoperative topical ocular hypotensive treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descemet-stripping with endothelial keratoplasty | 44 (38) | 67 ± 10 (41–87) | 9 (20) | 3 (7) |

| Deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty | 12 (11) | 74 ± 9 (56–85) | 4 (33) | 0 (0) |

| Penetrating keratoplasty | 13 (12) | 72 ± 7 (62–86) | 6 (46) | 3 (23) |

| Total | 69 (61) | 69 ± 10 (41–87) | 19 (27) | 6b (9) |

The only ocular surgical procedure performed prior to keratoplasty was cataract surgery in the number of eyes indicated; no other ocular surgery had been performed prior to keratoplasty in any eye.

Topical beta-blocker treatment was administered in 5 of the 6 eyes.

Thirty-five corneas of 24 control subjects were recruited; mean age was 70 ± 10 years (range, 51–90 years). No eye had received ocular surgery or was treated with topical ocular medications.

Corneal Sensitivity

Central corneal sensitivity in Fuchs dystrophy (4.61 ± 1.42 cm, n=69) was lower than that of age-matched controls (5.74 ± 0.48 cm, n=35, p<0.001). In Fuchs dystrophy, corneal sensitivity in the eyes without previous ocular surgery (4.82 ± 1.39 cm, n=50) was higher than in eyes with previous ocular (cataract) surgery (4.05 ± 1.39 cm, n=19, p=0.02). Corneal sensitivity was not correlated with central corneal thickness in eyes with Fuchs dystrophy (r= −0.01, p=0.89, n=69).

Before keratoplasty for Fuchs dystrophy, there were no differences in corneal sensitivity between the eyes that were destined for the three keratoplasty treatments (p≥0.29, Table 2). Sensitivity was decreased compared to preoperative at 1 month after DSEK (p<0.001), DLEK (p<0.001), and PK (p<0.001) (Table 2). The decrease in sensitivity at 1 month was greater after PK than after DLEK or DSEK (p<0.001), and greater after DLEK than after DSEK (p=0.01). After DSEK, sensitivity remained decreased at 1 year (p=0.001) but returned to the preoperative sensitivity by 2 years (4.50 ± 1.63 cm; p=0.99). Sensitivity remained decreased at 3 years after DSEK compared to controls (p<0.001). After DLEK, sensitivity remained decreased at 3 months (p=0.01) and did not differ statistically from the preoperative sensitivity at 6 months (3.08 ± 1.98 cm, p=0.48), although the minimum detectable difference between sensitivity at 6 months and before surgery was 1.5 cm (α=0.05/6, β=0.20, n=12). After PK, sensitivity did not return to preoperative sensitivity by 3 years (1.46 ± 1.98 cm, p<0.001).

Table 2.

Corneal sensitivity (mean ± SD) before and after keratoplasty for Fuchs endothelial dystrophy.

| Corneal Sensitivity, Filament Length (cm) [Filament Pressure (g/mm2)a] pb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Time after keratoplasty (months) |

Before | 1 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 |

|

Descemet-stripping with endothelial keratoplastyc |

4.68 ± 1.49 | 2.98 ± 2.01 | 3.20 ± 1.87 | 3.86 ± 1.91 | 3.83 ± 1.74 | 4.50 ± 1.63 | 4.50 ± 1.48 |

| [1.10 ± 1.69] | [4.69 ± 5.22] | [3.80 ± 4.52] | [2.62 ± 3.90] | [2.41 ± 3.48] | [1.37 ± 2.74] | [1.36 ± 2.50] | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.99 | 0.99 | ||

|

Deep lamellar endothelial keratoplastyd |

4.27 ± 1.49 | 1.58 ± 1.56 | 2.25 ± 1.96 | 3.08 ± 1.98 | 2.82 ± 1.72 | 4.18 ± 1.83 | 4.80 ± 1.48 |

| [1.06 ± 0.91] | [8.25 ± 6.04] | [6.39 ± 5.36] | [3.68 ± 4.10] | [4.45 ± 4.68] | [2.40 ± 3.91] | [0.84 ± 0.76] | |

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.99 | 0.99 | ||

|

Penetrating keratoplastye |

4.54 ± 0.77 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.15 ± 0.55 | 0.46 ± 0.97 | 1.46 ± 1.98 |

| [0.77 ± 0.39] | [≥16.0] | [≥16.0] | [≥16.0] | [≥16.0] | [≥15.9] | [≥5.1] | |

| - | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Filament length of 0 cm cannot be converted to a filament pressure, and thus was reported as ≥16.0 g/mm2.

vs. preoperative, p-values are adjusted for six comparisons.

n=44 at preoperative and 6 months; n=41 at 1 month; n=43 at 3 months; n=39 at 12 months; n=33 at 24 months; n=15 at 36 months.

n=12 at all examinations, except n=11 at 6 and 12 months, and n=10 at 36 months

n=13 at all examinations

Corneal nerves

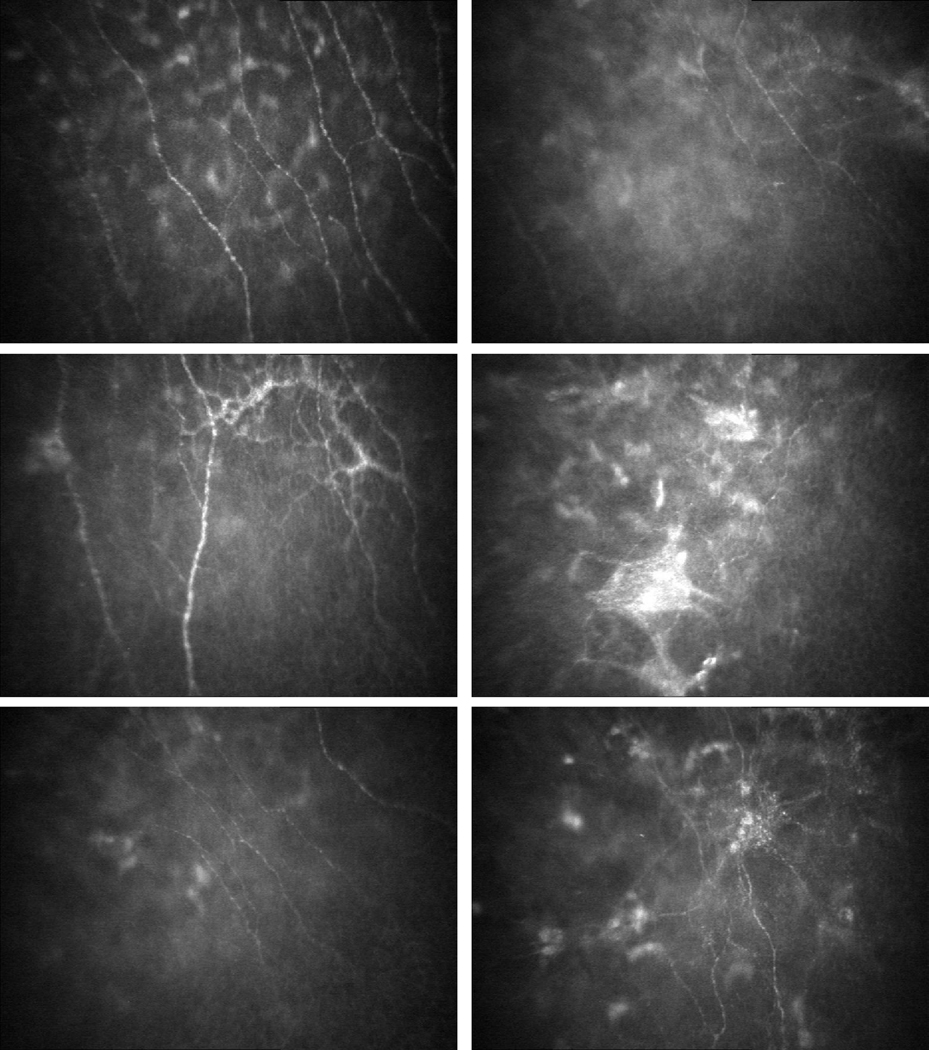

Confocal microscopy examination was performed in 42 of the 44 corneas before DSEK, 35 of the 39 corneas at 12 months, 28 of the 33 corneas at 24 months, and 13 of the 15 corneas at 36 months after DSEK. In Fuchs dystrophy, subbasal nerves were visible in 25 corneas (60%), and were abnormal in 17 of these corneas (68%). Typically, when subbasal nerves were visible, they were fine and sparse compared to normal (Figure 1). Occasionally, there were irregular nerve branching patterns or fine and fragmented nerves associated with thick stellate bright reflections (Figure 1). Qualitatively, nerve density appeared lower than normal, although the visibility of nerves in confocal images might have been impaired because of anterior corneal haze (bright reflectivity in confocal images). In Fuchs dystrophy, central corneal thickness did not differ if subbasal nerves were visible (656 ± 49 µm) or not visible (664 ± 53 µm; p=0.61), or if subbasal nerves appeared normal (654 ± 63 µm) or abnormal (657 ± 43 µm; p=0.89). Subbasal nerves continued to appear fine and sparse with occasional irregular branching compared to normal through 36 months after DSEK, (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Subbasal nerve fiber bundles in a normal cornea, and before and after Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) for Fuchs dystrophy (confocal microscopy).

Top Left, Subbasal nerve fiber bundles appear as linear bright structures between the basal epithelial cells and anterior keratocytes in normal corneas; the bright, out-of-focus objects in the image represent anterior keratocyte nuclei deep to the nerves. Top Right, In Fuchs dystrophy, when the subbasal nerves were visible, they were typically finer and sparser compared to normal; the diffuse increase in reflectivity represents subepithelial haze, which might have precluded visibility of subbasal nerve fiber bundles in some eyes. Second row, Occasionally in Fuchs dystrophy, there were thickened subbasal nerve fiber bundles with abnormal branching patterns (left), and thick, stellate brightly reflective structures associated with fine and fragmented nerve fiber bundles (right). Third row, Twenty-four months after DSEK for Fuchs dystrophy, the subbasal nerve fiber bundles typically remained fine and sparse (left) and occasionally there were thickened, brightly reflective nerve branch points with abnormal branching patterns (right). Dimensions of the confocal images were 428 × 325 µm (horizontal × vertical).

In Fuchs dystrophy, stromal nerves were visible in 31 corneas (74%), and were abnormal in 20 of these corneas (65%). Stromal nerves were tortuous, often forming loops, and appeared to be associated with brightly reflective keratocyte nuclei in some corneas (Figure 2). Tortuous nerves were often present in corneas that also exhibited stromal nerves of normal morphology. In Fuchs dystrophy, central thickness of corneas in which stromal nerves appeared normal was 675 ± 52 µm, and of corneas in which stromal nerves were not normal was 644 ± 53 µm, but the difference was not significant. (p=0.12). After DSEK, many corneas continued to exhibit tortuous and looped nerves, although they were typically thinner than they were before keratoplasty (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Stromal nerve fiber bundles in a normal cornea, and before and after Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) for Fuchs dystrophy (confocal microscopy).

Top Left, Stromal nerves in normal corneas typically appear as straight brightly reflective structures, and well-defined branching points are often visible. Top right and second row, In Fuchs dystrophy, nerves often were tortuous and formed loops in the mid stroma. Frequently, the tortuous nerves were associated with brightly reflective keratocyte nuclei. Third row, After DSEK, the tortuous nature of the stromal nerves persisted at 12 months (left) and 24 months (right) with the nerves typically appearing finer than before keratoplasty and often associated with brightly reflective keratocyte nuclei. Dimensions of the confocal images were 428 × 325 µm (horizontal × vertical), and all images were from the anterior and middle thirds of the corneal stroma.

At 12 months after DSEK, sensitivity was higher in corneas with visible subbasal nerves compared to corneas in which subbasal nerves were not visible (p=0.005, Table 3); a similar trend was noted before DSEK and at 24 and 36 months after DSEK, although these differences were not statistically significant (limited sample size). There were no statistical differences in sensitivity of corneas according to subbasal nerve morphology, or stromal nerve visibility or morphology (Table 3).

Table 3.

Corneal sensitivity by visibility and morphology of subbasal and stromal nerves in confocal microscopy images.

| Time after DSEK | Corneal Sensitivity (Filament Length, cm) (Number of eyes) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve visibility in confocal images | Nerve Morphologya | |||

| Visible | Not visible | Normal | Abnormal | |

| Subbasal Nerves | ||||

| Before | 4.84 ± 1.57 (25) |

4.35 ± 1.46 (17) |

5.06 ± 1.32 (8) |

4.74 ± 1.70 (17) |

| 12 months | 4.70 ± 1.51b (15) |

3.05 ± 1.67 (20) |

5.25 ± 0.96 (4) |

4.50 ± 1.66 (11) |

| 24 months | 5.02 ± 1.48 (21) |

4.29 ± 1.15 (7) |

5.05 ± 1.50 (10) |

5.00 ± 1.53 (11) |

| 36 months | 5.42 ± 0.80 (6) |

4.43 ± 1.13 (7) |

5.25 ± 0.96 (4) |

5.75 ± 0.35 (2) |

| Stromal Nerves | ||||

| Before | 4.61 ± 1.51 (31) |

4.73 ± 1.62 (11) |

4.73 ± 1.62 (11) |

4.55 ± 1.49 (20) |

| 12 months | 4.09 ± 1.73 (23) |

3.13 ± 1.79 (12) |

4.25 ± 1.49 (8) |

4.00 ± 1.89 (15) |

| 24 months | 5.05 ± 1.32 (21) |

4.21 ± 1.63 (7) |

5.35 ± 1.30 (13) |

4.56 ± 1.29 (8) |

| 36 months | 4.56 ± 1.12 (8) |

5.40 ± 0.89 (5) |

4.50 ± 1.32 (3) |

4.60 ± 1.14 (5) |

Nerve morphology could only be assessed when nerves were visible.

p=0.005 versus sensitivity when nerves were not visible.

DISCUSSION

Corneal sensitivity was decreased in eyes with Fuchs dystrophy and was not associated with central corneal thickness. Confocal microscopy of corneas with Fuchs dystrophy showed that subbasal nerves were frequently sparse and stromal nerves were often tortuous and formed loops. Three years after EK, corneal sensitivity had returned to preoperative sensitivity, but not to that of normal corneas, and abnormalities of the subbasal and stromal nerves persisted.

In his original case series with very advanced anterior corneal changes, Fuchs used a thread to qualitatively test corneal sensation and found that sensation was reduced or absent in most cases.5 A similar observation was made by Klien in one eye with Fuchs dystrophy that did not require surgical intervention.15 The eyes in our study did not have as advanced disease as those described by Fuchs, but were at the stage of requiring keratoplasty by current standards. None of the eyes in our study had corneal neovascularization or significant corneal scarring. We are unaware of other studies that have rigorously quantified corneal sensation in Fuchs dystrophy. Kumar et al. found that corneal sensitivity by Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometry was 5.9 cm in a group of 29 eyes, of which 14 eyes had Fuchs dystrophy and 10 eyes had pseudophakic corneal edema.16 Although their results contradict our findings, we found a reproducible decrease in mean sensitivity in the two groups of patients with Fuchs dystrophy enrolled to two consecutive studies (Table 2). Older age has been associated with a small decrease in corneal sensitivity,17 but not enough to explain the large difference between corneas with Fuchs dystrophy and controls, and our controls were age-matched. Similarly, decreased sensitivity in the Fuchs dystrophy group was not explained by a previous limbal incision for cataract surgery, because 50 of the 69 eyes had not had previous surgery, and the sensitivity of these 50 eyes was still lower than in controls. Interestingly, we did find a larger difference in corneal sensitivity between phakic and pseudophakic eyes with Fuchs dystrophy than has been reported in normal corneas after phacoemulsification.18 Sensitivity of the control corneas in this study was similar to that found by other investigators,17,19–21 and similar to that of young normal corneas (5.95 ± 0.15 cm) that were examined by the same technique in another study from our laboratory.22

Decreased corneal sensitivity in Fuchs dystrophy might not be unexpected given the ultrastructural changes that occur in the anterior cornea, but the exact mechanism of decreased sensitivity is unknown. It is possible that subepithelial fibrosis,1,2 and epithelial edema and bullae formation, result in damage to the subbasal nerves and epithelial nerve endings. Indeed, the subbasal nerves frequently appeared abnormal, and were qualitatively sparse or absent compared to normal corneas.13,23,24 We also found a trend toward decreased sensitivity in corneas in which subbasal nerves were not visible (Table 3), and this difference was statistically significant at 12 months after DSEK. However, the sparsity of subbasal nerves in confocal images of Fuchs dystrophy should be interpreted with caution, because of sampling errors by confocal microscopy, and because corneas with chronic edema exhibit increased backscatter (haze) from the subepithelial region.2,25 Subepithelial haze manifests as diffuse bright reflections in confocal images and can prevent visualization of subbasal nerves when, in fact, they are present. Thus, we did not attempt to measure subbasal nerve density in this study because the data might have been misleading. In a histologic study of 5 bullous corneas that were also examined by confocal microscopy,26 subbasal nerves were absent in 3 corneas by histology, which supports our qualitative confocal findings; however, in 1 cornea, subbasal nerves were present by histology and absent by confocal microscopy, indicating the limitation of confocal microscopy, and subbasal nerve density data were not validated by histologic data.26

Corneal stromal nerves were abnormally tortuous in Fuchs dystrophy, and this appearance persisted through 3 years after DSEK. Whether stromal nerve tortuosity is the result of damage to the distal subbasal nerves and epithelial nerve endings, or is a direct effect of chronic stromal edema, is unknown. In several corneas, stromal nerves formed loops, which were closely associated with brightly reflective keratocyte nuclei (Figure 3), suggesting that the nerve fiber bundles were attracted to the keratocytes. Corneal nerves have been shown to invaginate the cytoplasm of keratocytes by electron microscopy,27 suggesting communication between neural cells and keratocytes in the cornea,9 similar to that between epithelial and stromal cells.8 Regardless, with known abnormalities of keratocytes4,28 and the extracellular matrix in Fuchs dystrophy,29 it is conceivable that abnormalities of the stromal nerves are caused by the abnormal stromal environment in addition to any effect from distal nerve damage.

Corneal sensitivity was preserved after EK in contrast to sensitivity after PK, and this represents another advantage of EK over PK. Clinically, this preservation could eliminate threatening ocular surface complications that can be associated with a denervated cornea.30,31 Nevertheless, corneal sensitivity after EK did not return to that of age-matched normal corneas, and corneal nerve morphology was frequently abnormal even at 3 years after DSEK, providing further evidence of slow or incomplete anterior corneal repair.2,3 Whether corneal sensitivity will eventually return to normal will require extended follow-up.

The postoperative decrease in corneal sensitivity after keratoplasty correlated with the size of the keratoplasty incision, with least loss of sensitivity in the smallest incision (DSEK) group. Similarly, recovery of corneal sensitivity was also related to the size of the incision, with faster recovery after DSEK and DLEK than after PK. Although our data suggested that sensitivity recovered more quickly after DLEK (9–10 mm incision) than after DSEK (5–6 mm incision), the small size of the DLEK group limited our statistical power, and the smallest statistical difference that could have been found between preoperative and postoperative was 1.5 cm. Thus, with a larger sample size, it is likely that we would have found decreased sensitivity in the DLEK group at 6 and 12 months, similar to the DSEK group. After PK, there was limited recovery of corneal sensitivity by three years, confirming the results of previous studies.32–34

The lack of a simple and ideal esthesiometric method is a limitation of this and other corneal sensitivity studies. We standardized our Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometry technique between three observers to minimize technique-related variability in measurements, and we found a reproducible mean decrease and variance in sensitivity in two consecutive groups of subjects with Fuchs dystrophy. Cochet-Bonnet esthesiometry is also limited by ceiling and floor effects in normal and very abnormal (PK) eyes, and thus the true difference in sensitivity between Fuchs dystrophy and normal corneas was probably underestimated. Although corneal sensitivity might have been affected by topical medications, such as topical beta-blockers,35–37 none of the eyes in our study received topical ocular hypotensive treatment prior to keratoplasty, and only 9% received such treatment after keratoplasty. All eyes received topical corticosteroids postoperatively, but we are unaware of studies evaluating the effect of corticosteroids on corneal sensitivity. It is also important to emphasize that the findings in this study are not specific to Fuchs dystrophy, but are probably present in any etiology of chronic corneal edema.4,26

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant EY 02037, Bethesda, MD; Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY (SVP as Olga Keith Wiess Special Scholar, and an unrestricted departmental grant), and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Vision and Research in Ophthalmology, Fort Lauderdale, FL, May 2, 2010.

Financial disclosures: None (all authors)

REFERENCES

- 1.Morishige N, Yamada N, Teranishi S, Chikama T-i, Nishida T, Takahara A. Detection of subepithelial fibrosis associated with corneal stromal edema by second harmonic generation imaging microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3145–3150. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3309. (Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel SV, Baratz KH, Hodge DO, Maguire LJ, McLaren JW. The effect of corneal light scatter on vision after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(2):153–160. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel SV, McLaren JW, Hodge DO, Baratz KH. Scattered light and visual function in a randomized trial of deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hecker LA, McLaren JW, Bachman LA, Patel SV. Anterior keratocyte depletion in Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(5):555–561. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs E. Dystrophia epithelialis corneae. Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1910:76478–76508. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seery LS, McLaren JW, Kittleson KM, Patel SV. Retinal point-spread function after corneal transplantation for Fuchs' dystrophy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(2):1003–1008. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi T, Negishi K, Yamaguchi K, et al. Effect of anterior and posterior corneal surface irregularity on vision after Descemet-stripping endothelial keratoplasty. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35(4):688–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson SE, Netto M, Ambrósio R., Jr Corneal cells: chatty in development, homeostasis, wound healing, and disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(3):530–536. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.You L, Kruse FE, Volcker HE. Neurotrophic factors in the human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(3):692–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaren JW, Patel SV, Bourne WM, Baratz KH. Corneal wavefront errors 24 months after deep lamellar endothelial keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147(6):959–965. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed KA, McLaren JW, Baratz KH, Maguire LJ, Kittleson KM, Patel SV. Host and graft thickness after Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty for Fuchs endothelial dystrophy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(4):490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.05.011. Epub 2010 Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochet P, Bonnet R. L'esthesie corneene: sa mesure clinique: ses variations physiologiques et pathologiques. Clin Ophthalmol. 1960;(4):3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erie EA, McLaren JW, Kittleson KM, Patel SV, Erie JC, Bourne WM. Corneal subbasal nerve density: A comparison of two confocal microscopes. Eye Contact Lens. 2008;34(6):322–325. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31818b74f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klien BA. Fuchs' epithelial dystrophy of the cornea; a clinical and histopathologic study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1958;46(3 Part 1):297–304. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(58)90253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar RL, Koenig SB, Covert DJ. Corneal sensation after Descemet stripping and automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2010;29(1):13–18. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181ac052b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roszkowska AM, Colosi P, Ferreri FM, Galasso S. Age-related modifications of corneal sensitivity. Ophthalmologica. 2004;218(5):350–355. doi: 10.1159/000079478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JH, Chung JL, Kang SY, Kim SW, Seo KY. Change in corneal sensitivity and corneal nerve after cataract surgery. Cornea. 2009;28(11):S20–S25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linna TU, Vesaluoma MH, Perez-Santonja JJ, Petroll WM, Alio JL, Tervo TM. Effect of myopic LASIK on corneal sensitivity and morphology of subbasal nerves. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(2):393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnenfeld ED, Solomon K, Perry HD, et al. The effect of hinge position on corneal sensation and dry eye after LASIK. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(5):1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00100-3. discussion 1029–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mian SI, Li AY, Dutta S, Musch DC, Shtein RM. Dry eyes and corneal sensation after laser in situ keratomileusis with femtosecond laser flap creation: Effect of hinge position, hinge angle, and flap thickness. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35(12):2092–2098. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SV, McLaren JW, Hodge DO, Bourne WM. Confocal microscopy in vivo in corneas of long-term contact lens wearers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(4):995–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erie JC, McLaren JW, Hodge DO, Bourne WM. The effect of age on the corneal subbasal nerve plexus. Cornea. 2005;24(6):705–709. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000154387.51355.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel SV, McLaren JW, Kittleson KM, Bourne WM. Subbasal nerve density and corneal sensitivity after LASIK: Femtosecond laser versus mechanical microkeratome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(11):1413–1419. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi A, Mawatari Y, Yokogawa H, Sugiyama K. In vivo laser confocal microscopy after Descemet stripping with automated endothelial keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(6):977–985. e971. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Aqaba M, Alomar T, Lowe J, Dua HS. Corneal nerve aberrations in bullous keratopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011 Feb 10; doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.11.013. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller LJ, Pels L, Vrensen GF. Ultrastructural organization of human corneal nerves. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(4):476–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li QJ, Ashraf MF, Shen DF, et al. The role of apoptosis in the pathogenesis of Fuchs endothelial dystrophy of the cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(11):1597–1604. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.11.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calandra A, Chwa M, Kenney MC. Characterization of stroma from Fuchs' endothelial dystrophy corneas. Cornea. 1989;8(2):90–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson SE, Kaufman HE. Graft failure after penetrating keratoplasty. Surv Ophthalmol. 1990;34(5):325–356. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(90)90110-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beuerman RW, Schimmelpfennig B. Sensory denervation of the rabbit cornea affects epithelial properties. Exp Neurol. 1980;69(1):196–201. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(80)90154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao GN, John T, Ishida N, Aquavella JV. Recovery of corneal sensitivity in grafts following penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(10):1408–1411. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33857-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathers WD, Jester JV, Lemp MA. Return of human corneal sensitivity after penetrating keratoplasty. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(2):210–211. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060130220030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richter A, Slowik C, Somodi S, Vick HP, Guthoff R. Corneal reinnervation following penetrating keratoplasty-- correlation of esthesiometry and confocal microscopy. Ger J Ophthalmol. 1996;5(6):513–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weissman SS, Asbell PA. Effects of topical timolol (0.5%) and betaxolol (0.5%) on corneal sensitivity. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74(7):409–412. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.7.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogel R, Clineschmidt CM, Hoeh H, Kulaga SF, Tipping RW. The effect of timolol, betaxolol, and placebo on corneal sensitivity in healthy volunteers. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1990;6(2):85–90. doi: 10.1089/jop.1990.6.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Buskirk EM. Corneal anesthesia after timolol maleate therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88(4):739–743. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90675-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]