Abstract

Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) is a leading cause of acute tubular necrosis and delayed graft function in transplanted organs. Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) propagates the micro-inflammatory response that drives IRI. This study sought to determine the specific effects of Marimastat (Vernalis, BB-2516), a broad spectrum MMP and tumor necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme inhibitor, on IRI-induced acute tubular necrosis. Mice were pre-treated with Marimastat or methylcellulose vehicle for 4 days prior to surgery. Renal pedicles were bilaterally occluded for 30 minutes and allowed to reperfuse for 24 hours. Baseline creatinine levels were consistent between experimental groups; however, post-IRI creatinine levels were four-fold higher in control mice (P<0.0001). The mean difference between the post-IRI histology grades of Marimastat-treated and control kidneys was 1.57 (P=0.003), demonstrating more severe damage to control kidneys. Post-IRI mean (±SEM) MMP-2 activity rose from baseline levels in control mice (3.62±0.99); however, pretreated mice presented only a slight increase in mean MMP-2 activity (1.57±0.72) (P<0.001). In conclusion, these data demonstrate that MMP inhibition is associated with a reduction of IRI in a murine model.

Ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI) affects post-transplant renal function and largely determines short and long-term graft survival. Although some ischemia is unavoidable, IRI continues to be the leading cause of acute renal injury and delayed graft function in transplanted organs (1). The development of acute tubular necrosis (ATN), one of the leading causes of intrinsic acute renal injury, is a hallmark of IRI. IRI induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines which, in turn, contribute to graft fibrosis (2,3). There is no clinically acceptable therapy that directly addresses the cellular damage induced by IRI (4,5). Due to its intrinsic nature, IRI remains a challenge in the field of organ transplantation.

Ischemia–reperfusion initiates a cascade of events that involve tubular epithelial injury, inflammation, and altered microvascular function (6). The initial ischemic event depletes ATP reservoirs which subsequently impairs cellular processes such as protein synthesis, lipogenesis, and membrane transport. The succeeding biochemical abnormalities disrupt the cytoskeleton, damage cellular proteins and degrade DNA, leading to apoptosis and/or necrosis of tubular epithelial cells (7). The cellular damage induces a vigorous inflammatory response which further propagates post-ischemic tissue damage (8,9).

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are active components of inflammation that are also involved in other processes in which tissue remodeling maintains proper function such as embryonic development, angiogenesis and wound healing (10,11). Upregulation of MMPs propagates the micro-inflammatory response that drives IRI. Evidence of MMP activation has been inferred microscopically from loss of junctional complexes and altered expression and distribution of cellular adhesion molecules, suggesting a disruption of cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions (12,13). MMPs are sequestered by neutrophils and are activated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) which is upregulated in animal models of ischemic injury (14,15). TNF-α is a critical mediator of both the physiologic defensive response to and pathogenesis of IRI, and exists in a biologically active, secreted form and in an inactive membrane-anchored precursor. Cleavage of the TNF-α proform into its soluble form is mediated by TNF-α-converting enzyme (TACE, also known as ADAM17 and CD156b), which belongs to the disintegrin and metalloproteinase family of zinc-metalloproteinases (16,17). The TACE-induced increase in TNF-α availability is thought to promote a more extensive inflammatory response which would directly impact the severity of tissue injury.

The degree and duration of MMPs elevation (protein or activity) has been shown to influence the extent of renal damage (11). Although IRI is a strong predictor of graft survival, no current therapies address the role of MMPs during kidney transplantation. The present study was designed to determine the specific effects of pre-treatment with Marimastat (Vernalis, BB-2516), a broad spectrum MMP-inhibitor, on IRI-induced ATN. Marimastat is a synthetic, low molecular weight succinate peptidomimetic inhibitor that covalently binds to the Zn2+ ion in the active site of MMP, thus inhibiting its action. Marimastat has been used in multiple oncologic clinical trials in the adult population. The most consistently reported toxicity concern is musculoskeletal pain that likely to occur after two months of treatment (18,19). We previously demonstrated that Marimastat is capable of decreasing serum TNF-α receptor II levels (20). Although Marimastat is a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor, this study focused on its ability to inhibit MMP-2 and MMP-9 (gelatinases), both of which play a role in ischemia-related inflammation. We propose that Marimastat will reduce kidney IRI, predominantly through its role as an inhibitor of MMP-2 and MMP-9.

Materials & Methods

Animal Model

5-7 week old male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were housed five animals to a cage in a barrier room with ad libitum access to food and water. Animal protocols complied with the NIH Animal Research Advisory Committee guidelines and were approved by the Children’s Hospital Boston Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To ensure that Marimastat (half life 10 hrs) reaches a steady state plasma level, ninety-six hours prior to surgery, the experimental group (n=7) received 100mg/kg of Marimastat treatment (MT) in 100 μl of 0.45% methylcellulose vehicle (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) via orogastric gavage twice daily (21). Control mice (n=8) received methylcellulose vehicle alone. A sham group (n=5) was given methylcellulose vehicle alone. A dose-dependent relationship between Marimastat and TNF-α showed complete inhibition at 200 mg/kg (22).

IRI was performed through a flank incision after the animals were anesthetized with 2-4% isofluorane inhalation. IRI was induced as previously described (23). The kidney was isolated and a microvascular clamp (Roboz, Rockville, MD) was placed on the renal pedicle for 30 minutes, during which the kidney and clamp were gently placed back into the peritoneum. The contra-lateral kidney underwent the same procedure within 5 minutes. Treatment was continued for 24 hours post-operatively. Sham mice underwent bilateral flank incisions without clamping the renal pedicles.

Specimen Collection

24 hours after reperfusion, the experiment was ended. Animals was anesthetized, blood was collected and centrifuged at 4°C at 8000 rpm for 10 min to separate the serum. Creatinine and BUN levels were measured using a Hitachi 917 analyzer (Roche, Branford, CT).

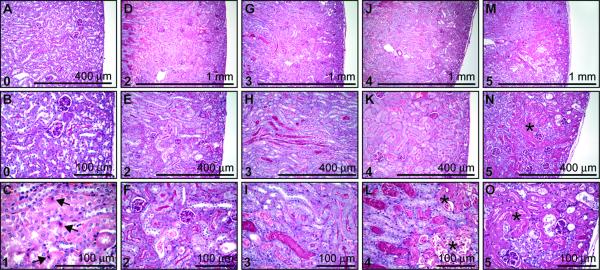

At the time of sacrifice, the kidneys were excised, weighed and bisected transversely to their length. Approximately one half of each kidney was fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin at 4°C overnight, washed with phosphate buffered saline and stored in 70% ethanol and then embedded in paraffin. Tissues were cut into 5-μm sections and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or periodic acid-Schiff reagent (PAS). Histological sections were reviewed by a pathologist in blinded fashion and scored with a semiquantitative scale (Fig. 1) to evaluate the extent of tubular necrosis: 0, normal kidney; 1, normal kidney with focal apoptosis; 2, focal tubular necrosis (TN) <50% of the cortical-medullary junction (CMJ); 3, TN in the CMJ; 4, TN in the CMJ with focal extension into the cortex; 5, TN extending through the cortex to the surface of the kidney. Histological assessment and the scoring parameters were modified from previously described methods, with an emphasis on the location of TN (24,25).

Figure 1. Histological scoring criteria.

(A-O) Representative PAS stained kidney sections, unless otherwise stated, obtained 24hr after IR. Representative grade denoted at the top left corner of each frame. (A-B) Grade 0, normal kidney. (C) Grade 1, normal kidney (H&E) with focal apoptosis (denoted by arrow). (D-F) Grade 2, focal tubular necrosis (TN) (<50% of CMJ). (G-I) Grade 3, TN in the CMJ. (J-L) Grade 4, TN in the CMJ with focal extension into the cortex. (M-O) Grade 5, TN extending through the cortex to the surface of the kidney. Necrosis is labeled with a star (*).

Zymography

Urine samples were collected before bilateral IRI and 24 hours following IRI. Gelatin zymography was performed on urine samples as previously described (26,27) with modifications to determine MMP activity in the urine. Fifteen microliter of each urine sample was mixed with 10 μl buffer consisting of 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.15 M Tris (pH 6.8), 20% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.5% (w/v) bromphenol blue. Samples were loaded into wells of a 10% SDS-PAGE gel containing 0.1% (w/v) gelatin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) on a mini gel apparatus. Gels were run at 200 V for 50 minutes then soaked in 2.5% TritonX-100 with gentle shaking for 30 minutes at ambient temperature. After incubating overnight at 37°C in substrate buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL buffer pH 8, 5 mM CaCl2, and 0.02% NaN3), gels were stained for 30 minutes in 0.5% Coomassie Blue R-250 in acetic acid, ethanol, and water (1:3:6) and destained for 1 hour. As previously described, MMP levels were quantified by scoring the band strength of each type of MMP examined on the zymogram on a scale of zero to seven, with zero indicating no detectable MMPs, and seven indicating strong bands (28).

Western Blot Analysis

Western Blot analysis was performed on the lysate of the other half of each kidney. Protein extraction was performed using an ActiveMotif extraction kit according to the manufacture’s protocol (ActiveMotif, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were normalized for protein content by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Seventy-five micrograms of protein per sample were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Membranes were then probed overnight at 4°C with either goat anti-mouse MMP-2 (1:500, R&D Systems), goat anti-mouse MMP-9 (1:500, R&D Systems), or rabbit polyclonical anti-human TACE (1:500, Novus Biologicals). The secondary antibodies used were either horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked donkey anti-goat IgG in a 1:5,000 dilution (Santa Cruz, CA), or ECL donkey anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked whole antibody in a 1:5,000 dilution (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Equal protein loading was verified by incubating the same membrane with α-actin antibody in a 1:500 dilution (MS X Actin, Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). The probed proteins were developed with Pierce enhanced chemiluminescent substrate for detection of HRP according to manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Statistical Analysis

ANOVA with Turkey-Kramer multiple comparisons test was performed (unless otherwise indicated) using GraphPad InStat Version 3.05 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Results were obtained from two independent occasions and were expressed as mean ± SEM. For all experiments probabilities of error (P values) were included; values for P<0.05 were regarded as significant.

Results

Histology Grades

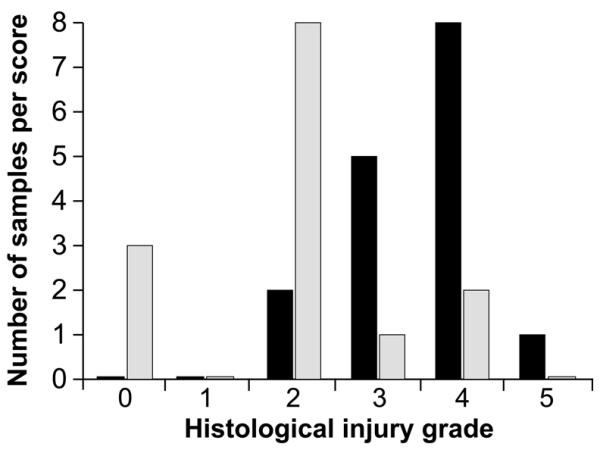

Histological scores were determined by the presence and location of necrosis within the kidney. Both kidneys from each mouse received a separate, blinded grade. MT kidneys received a mean (±SEM) histological score of 1.93±0.34. Control kidneys demonstrated a significant degree of tubular damage and received a histological score of 3.50±20 (Fig. 2). The mean difference between MT and control kidneys was 1.57 (P=0.003).

Figure 2. Distribution of Histological injury scores.

(A) Vehicle (100 μl of 0.45% methylcellulose), denoted in black, and Marimastat (100 mg/kg in 100 μl of vehicle), denoted in grey, were administered twice daily. Scores were determined 24hr post-IRI by a blinded pathologist.

The injury seen in MT mice was mild and consistently limited to the CMJ (85.6% of the total number of kidneys). Extension of necrosis into the cortex denoted more severe tubular injury, frequently observed in control mice (56.3%). Injury severity increased in parallel to the proximity of necrotic extension towards the outer cortical surface, and more than half of control mice had necrotic extension into the cortex. One of the 2 kidneys from 2 MT mice had focal necrotic extension into the cortex (grade 4); however, neither mouse showed a significant increase in post-IRI plasma creatinine levels (0.0 and 0.4).

Serum Creatinine

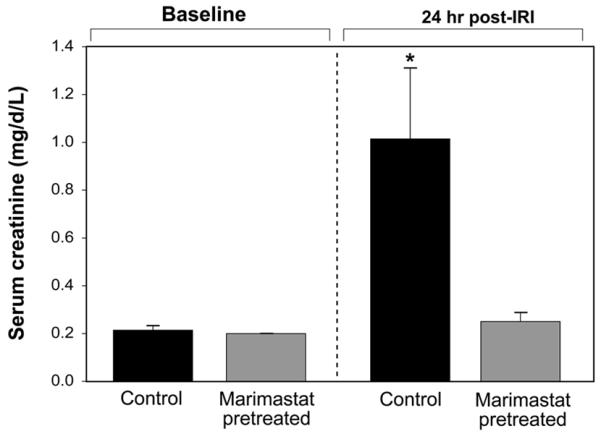

Serum creatinine levels were obtained from all experimental groups immediately prior to IRI and again 24-hours after IRI. An additional draw was taken prior to the first Marimastat dose and showed that Marimastat did not affect creatinine levels prior to IRI (data not shown). Baseline creatinine levels prior to IRI were consistent between experimental groups (P=0.788) (Fig. 3). Mean serum creatinine levels in mice pretreated with Marimastat (0.25±0.03) were not statistically different from baseline levels (0.20±0.00) (P=0.268). In contrast, the post-IRI control mice demonstrated a significant increase to 1.01±0.29 from the baseline levels of 0.21±0.01 (P=0.003). Post-IRI, the creatinine levels of control mice were four-fold higher than in MT mice (P<0.0001).

Figure 3. Creatinine levels 24hr post-IRI.

In vivo creatinine levels were measured prior to injury and prior to euthanasia (24 hours post-IRI). Vehicle (100 μl of 0.45% methylcellulose) and Marimastat (100 mg/kg in 100 μl of vehicle) were administered 96 hours prior to surgery and was continued 24 h post operatively for a total of 10 doses. *P= 0.003 compared with baseline levels.

Gelatin zymography

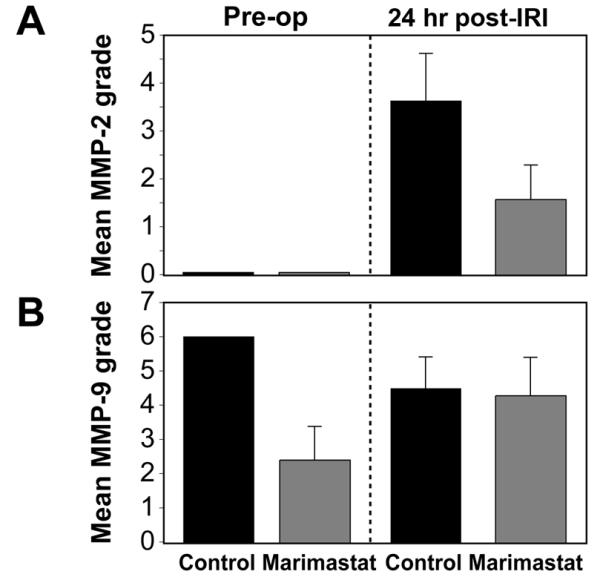

Urine was screened for MMP activity by gelatin zymography prior to bilateral IRI and 24 hours following IRI. In contrast to blood-specimen collection, urine collection is noninvasive and will not influence detectable MMP levels. The band strength visualized by gelatin zymography provided an estimation of relative activity of the gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Fig. 4A-B).

Figure 4. Matrix metalloproteinase activity.

Gelatin zymography was performed on mouse urine collected prior to and following IRI; both proenzyme and activated proteinases appear as zones of substrate clearing. (A) Graph of MMP-2 and (B) MMP-9 activity prior to injury and prior to euthanasia (24hr post-IRI) in control and Marimastat-treated mice.

Active MMP-2 was undetectable in the pre-op samples of MT and control mice. MMP-2 activity rose significantly from baseline levels 24 hours post-IRI in control mice (3.62±0.99) however MT mice demonstrated only a slight increase in MMP-2 activity (1.57±0.72) (Fig. 4D). The post-IRI rise in MMP-2 activity between control and MT mice was significant (P<0.001). There was no statistically difference in MMP-9 activity between groups and time points (Fig. 4E).

Western Blot

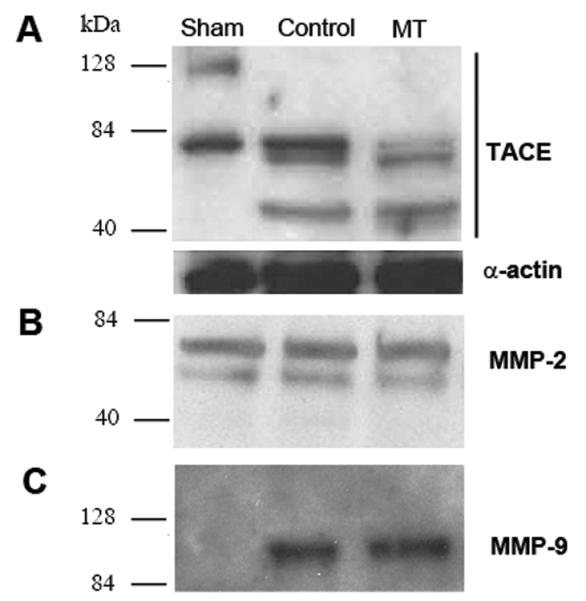

Western blot analysis was conducted to determine the levels of MMP-2, MMP-9 and TACE in kidney tissue. In normal kidney, TACE is expressed constitutively as an 85 kDa protein. Another 120 kDa band has also been described under reducing conditions in the normal kidney (17). In normal kidneys, both bands were present (Fig. 5A). Twenty four hours after IRI, control mice showed a decreased in expression of the 85 kDa band, whereas the 120 kDa band was no longer present. Instead, a smaller, approximately 45 kDa band was noted. Mice in the MT group showed reduced expression of the 85 kDa band.

Figure 5. Western Blots of tissue TACE, MMP-2 and MMP-9.

Western Blots were performed on sham, control and Marimastat treated (MT) kidneys. TACE expressed as 120 kDa and 85 kDa bands in sham kidney; 85 kDa and 45 kDa bands in untreated (control) kidney; and 85 kDa and 45 kDa bands in MT kidney (A). MMP-2 was expressed as a 65 kDa band in the sham, control and MT kidneys (B). MMP-9 was not expressed in sham kidney but expressed as 90 kDa in control and MT kidneys (C).

MMP-2 was expressed in normal kidneys (29) as a 65 kDa band and there was no change in its level in control and MT kidneys postoperatively (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, MMP-9 (90 kDa band) was not expressed in normal kidney. IRI kidneys expressed MMP-9 in the control and MT group after 24 hours (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

Inflammation plays an important role in the progression from IRI to ATN and ultimately compromised renal function. Post-IR inflammation is a pivotal phase which heavily dictates the severity of tubular injury. Upregulation of MMPs propagates this microinflammatory response (30). The limited research regarding MMP expression in post-IRI of the kidneys has focused on its later role in tubulointerstitial fibrosis and chronic allograft nephropathy (31,32). This study is directed at MMP participation in earlier stages of injury.

MMP activity is most pronounced and their inhibition is most effective in the early stage of disease. Animal models studying the efficacy of MMP inhibition in IRI and various cancers have suggested that MMP inhibition initiated prior to or in the initial period of disease progression significantly reduced the severity and degree of tissue damage (33,34). Lutz et al. demonstrated that MMP-2 inhibition reduced allograph nephropathy if initiated in the early, prefibrotic stages of disease but produced more severe nephropathy once fibrosis was established (35). In clinical trials, however, MMP inhibition has been typically implemented at more advanced stages of disease (36,37). The therapeutic modalities appropriate at the early stages may be misdirected once significant injury has been established. The disparity of outcome between experimental models and clinical trials demonstrates that the point of therapeutic intervention may be a critical factor determining the relevance and efficacy of MMP inhibition.

The murine model of renal IRI used in this study represents the renal injury observed during early graft dysfunction in the transplanted kidney (23). Tubular dysfunction begins shortly after the onset of ischemia, initiating a dynamic interplay between pro-inflammatory mediators that will direct subsequent inflammation.

MMP activity is mediated by several mechanisms and at several levels. TNF-α plays a role in the induction and propagation of inflammation by directly activating MMPs and initiating an influx of neutrophils to the site of injury (9). Cleavage of the cell-associated TNF-α proform into its soluble, biologically-active form is mediated by TACE (16,17). Activation of TACE following ischemia-reperfusion has been shown to directly contribute to the pathogenesis of brain, lung, heart and liver tissue injury (38-40). The upstream inhibition of TACE potentially abrogates the inflammatory cascade by reducing the amount of activated TNF-α. Results obtained from western blot analysis showed a change in the pattern of expression of TACE between controls and mice that underwent IRI. Twenty four hours after IRI, a new band with molecular weight 45 kDa was identified with anti-TACE antibody. Although further investigation is warranted, this molecule could be the catalytic domain of TACE that has been described elsewhere (41). When administered prior to IRI, Marimastat reduced IRI as evidenced by both histological and biochemical analysis. Morphologically, Marimastat diminished the scope and severity of ATN. Although apoptosis does contribute to ischemic injury, necrosis is more often associated with IRI. In contrast to apoptosis, which occurs under normal physiological conditions and requires ATP, necrosis does not require ATP to proceed and only occurs after gross cellular injury (42). The location of necrosis was an important consideration in the histological analysis because differential metabolic demands within the kidney may determine areas most affected by ischemia. Necrosis was most prominent in the CMJ, which is presumably due to its high metabolic activity and its limited ability to sustain anaerobic metabolism amidst decreased oxygen tension (43,44). Not only do cortical proximal tubules require very low oxygen extraction to support tubule metabolism, blood flow in the post-ischemic kidney is more concentrated in the cortex rather than the medulla, which could explain the initiation and predominance of injury in the CMJ (44). Tubular necrosis is associated with elevated serum creatinine levels as seen in control mice. In contrast, serum creatinine in Marimastat mice demonstrated a non-significant increase over baseline indicating that Marimastat reduced tubular necrosis.

Although MMP-2 is constitutively expressed in renal tissue, the absence of MMP-2 activity in urine samples at baseline of both MT and control mice might reflect its low urinary level until IRI occurs. A recent study found that while MMP-2 activity increased 24 hours after ischemia, an increase in MMP-9 activity was not detected until 48-72 hours post ischemia (45). Since we only measured MMP levels 24 hours following IRI, our findings are consistent with this study demonstrating that urine MMP-2 is a prominent initial participant in post-IRI.

Results from the western blot showed increased MMP-9 protein levels following renal IRI. Gelatin zymography, however, demonstrated that MMP-9 activity remained unchanged between groups and time points. MMP-9 has been shown to form a complex with other molecules such as NGAL, which protects it from degredation (46) and is a marker of renal injury (47). Therefore, it is likely that increased MMP-9 protein level was partially due to a decrease of MMP-9 degradation.

Inhibition of MMPs has become a widely studied topic because of their involvement in many pathologic states. Pretreatment with MMP inhibitors may be applicable clinically. It may benefit those awaiting transplantation in which viable, fully functional organs are expected to undergo transient ischemia, an important one being pediatric transplantation. A crucial element of graft health and sustainability is the degree of ischemic injury, which may be effectively reduced if MMP inhibition is initiated prior to insult. Pretreatment with Marimastat may be a preferable alternative to current therapies in pediatric transplantation, such as tetracyclines, due to its more favorable side effect profile. Despite being protective against ischemia reperfusion injury in a variety of tissues, the use of tetracyclines in the pediatric population is complicated by non-compliance, enamel discoloration, stunted growth and nephrotoxicity (48,49). The period immediately following reperfusion is a critical point in the prevention of renal injury (6). In conclusion, as we have shown that urine MMPs can be used as biomarkers to follow a disease process (50), we demonstrate here that prevention of MMP-2 activation may be a possible mechanism for renal post-transplant protection. Prophylactic MMP inhibition in both donor and recipient prior to and following renal transplant may decrease post-transplant morbidity and foster graft function.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: K.B.N was supported by the Children’s Hospital Surgical Foundation (Boston, MA). H.D.L was the recipient of the Joshua Ryan Rappaport Fellowship and supported by the Children’s Hospital Surgical Foundation (Boston, MA). M.P. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant DK069621-05) and the Children’s Hospital Surgical Foundation (Boston, MA).

Abbreviations

- ATN

acute tubular necrosis

- CMJ

cortico-medullary junction

- EMC

extracellular matrix

- H&E

haematoxylin and eosin

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IRI

ischemia-reperfusion injury

- MT

Marimastat treatment

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- TACE

TNF-α-converting enzyme

- TN

tubular necrosis

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor–alpha

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shoskes DA, Halloran PF. Delayed graft function in renal transplantation: etiology, management and long-term significance. J Urol. 1996;155:1831–1840. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul LC. Chronic renal transplant loss. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1491–1499. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azuma H, Nadeau K, Takada M, Mackenzie HS, Tilney NL. Cellular and molecular predictors of chronic renal dysfunction after initial ischemia/reperfusion injury of a single kidney. Transplantation. 1997;64:190–197. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Star RA. Treatment of acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1817–1831. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly KJ, Molitoris BA. Acute renal failure in the new millennium: time to consider combination therapy. Semin Nephrol. 2000;20:4–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonventre JV, Weinberg JM. Recent advances in the pathophysiology of ischemic acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2199–2210. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000079785.13922.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padanilam BJ. Cell death induced by acute renal injury: a perspective on the contributions of apoptosis and necrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F608–F627. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00284.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonventre JV, Zuk A. Ischemic acute renal failure: an inflammatory disease? Kidney Int. 2004;66:480–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.761_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnahoo KK, Shames BD, Harken AH, Meldrum DR. Review article: the role of tumor necrosis factor in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Urol. 1999;162:196–203. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199907000-00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy R, Zhang B, Moses MA. Making the cut: protease-mediated regulation of angiogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:608–622. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenz O, Elliot SJ, Stetler-Stevenson WG. Matrix metalloproteinases in renal development and disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:574–581. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V113574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonventre JV. Mechanisms of ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1993;43:1160–1178. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton TA, Molitoris BA. Mechanisms of cellular injury in ischemic acute renal failure. Semin Nephrol. 1998;18:490–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donnahoo KK, Meng X, Ayala A, Cain MP, Harken AH, Meldrum DR. Early kidney TNF-alpha expression mediates neutrophil infiltration and injury after renal ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R922–R929. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.3.R922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donnahoo KK, Meldrum DR, Shenkar R, Chung CS, Abraham E, Harken AH. Early renal ischemia, with or without reperfusion, activates NFkappaB and increases TNF-alpha bioactivity in the kidney. J Urol. 2000;163:1328–1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss ML, Jin SL, Milla ME, Bickett DM, Burkhart W, Carter HL, Chen WJ, Clay WC, Didsbury JR, Hassler D, Hoffman CR, Kost TA, Lambert MH, Leesnitzer MA, McCauley P, McGeehan G, Mitchell J, Moyer M, Pahel G, Rocque W, Overton LK, Schoenen F, Seaton T, Su JL, Warner J, Willard D, Becherer JD. Cloning of a disintegrin metalloproteinase that processes precursor tumour-necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1997;385:733–736. doi: 10.1038/385733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, Castner BJ, Stocking KL, Reddy P, Srinivasan S, Nelson N, Boiani N, Schooley KA, Gerhart M, Davis R, Fitzner JN, Johnson RS, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Cerretti DP. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature. 1997;385:729–733. doi: 10.1038/385729a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bramhall SR, Hallissey MT, Whiting J, Scholefield J, Tierney G, Stuart RC, Hawkins RE, McCulloch P, Maughan T, Brown PD, Baillet M, Fielding JW. Marimastat as maintenance therapy for patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1864–1870. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenbaum E, Zahurak M, Sinibaldi V, Carducci MA, Pili R, Laufer M, DeWeese TL, Eisenberger MA. Marimastat in the treatment of patients with biochemically relapsed prostate cancer: a prospective randomized, double-blind, phase I/II trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4437–4443. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alwayn IP, Andersson C, Lee S, Arsenault DA, Bistrian BR, Gura KM, Nose V, Zauscher B, Moses M, Puder M. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases increases PPAR-alpha and IL-6 and prevents dietary-induced hepatic steatosis and injury in a murine model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G1011–G1019. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00047.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen HS, McCann PP. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition as a novel anticancer strategy: a review with special focus on batimastat and marimastat. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;75:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuji F, Oki K, Okahara A, Suhara H, Yamanouchi T, Sasano M, Mita S, Horiuchi M. Differential effects between marimastat, a TNF-alpha converting enzyme inhibitor, and anti-TNF-alpha antibody on murine models for sepsis and arthritis. Cytokine. 2002;17:294–300. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weight SC, Furness PN, Nicholson ML. New model of renal warm ischaemia-reperfusion injury for comparative functional, morphological and pathophysiological studies. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1669–1673. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McWhinnie DL, Thompson JF, Taylor HM, Chapman JR, Bolton EM, Carter NP, Wood RF, Morris PJ. Morphometric analysis of cellular infiltration assessed by monoclonal antibody labeling in sequential human renal allograft biopsies. Transplantation. 1986;42:352–358. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198610000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solez K, Racusen LC, Marcussen N, Slatnik I, Keown P, Burdick JF, Olsen S. Morphology of ischemic acute renal failure, normal function, and cyclosporine toxicity in cyclosporine-treated renal allograft recipients. Kidney Int. 1993;43:1058–1067. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moses MA, Wiederschain D, Loughlin KR, Zurakowski D, Lamb CC, Freeman MR. Increased incidence of matrix metalloproteinases in urine of cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1395–1399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camphausen K, Moses MA, Beecken WD, Khan MK, Folkman J, O’Reilly MS. Radiation therapy to a primary tumor accelerates metastatic growth in mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2207–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan LW, Moses MA, Goley E, Sproull M, Muanza T, Coleman CN, Figg WD, Albert PS, Menard C, Camphausen K. Urinary VEGF and MMP levels as predictive markers of 1-year progression-free survival in cancer patients treated with radiation therapy: a longitudinal study of protein kinetics throughout tumor progression and therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:499–506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reponen P, Sahlberg C, Huhtala P, Hurskainen T, Thesleff I, Tryggvason K. Molecular cloning of murine 72-kDa type IV collagenase and its expression during mouse development. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:7856–7862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winn RK, Ramamoorthy C, Vedder NB, Sharar SR, Harlan JM. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;832:311–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb46259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts IS, Brenchley PE. Mast cells: the forgotten cells of renal fibrosis. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:858–862. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.11.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada M, Ueda M, Naruko T, Tanabe S, Han YS, Ikura Y, Ogami M, Takai S, Miyazaki M. Mast cell chymase expression and mast cell phenotypes in human rejected kidneys. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1374–1381. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590041374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto H, Koga H, Iida M, Tarumi K, Fujita M, Haruma K. Blockade of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme improves experimental small intestinal damage by decreasing matrix metalloproteinase-3 production in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1320–1329. doi: 10.1080/00365520600684571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergers G, Javaherian K, Lo KM, Folkman J, Hanahan D. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on multistage carcinogenesis in mice. Science. 1999;284:808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutz J, Yao Y, Song E, Antus B, Hamar P, Liu S, Heemann U. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases during chronic allograft nephropathy in rats. Transplantation. 2005;79:655–661. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000151644.85832.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bramhall SR, Rosemurgy A, Brown PD, Bowry C, Buckels JA. Marimastat as first-line therapy for patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3447–3455. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295:2387–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilles S, Zahler S, Welsch U, Sommerhoff CP, Becker BF. Release of TNF-alpha during myocardial reperfusion depends on oxidative stress and is prevented by mast cell stabilizers. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;60:608–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goto T, Ishizaka A, Kobayashi F, Kohno M, Sawafuji M, Tasaka S, Ikeda E, Okada Y, Maruyama I, Kobayashi K. Importance of tumor necrosis factor-alpha cleavage process in post-transplantation lung injury in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1239–1246. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200402-146OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang ZY, Loss G, Carmody I, Cohen AJ. TIMP-3 ameliorates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme activity in rats. Transplantation. 2006;82:1518–1523. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000243381.41777.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amour A, Slocombe PM, Webster A, Butler M, Knight CG, Smith BJ, Stephens PE, Shelley C, Hutton M, Knauper V, Docherty AJ, Murphy G. TNF-alpha converting enzyme (TACE) is inhibited by TIMP-3. FEBS Lett. 1998;435:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nicotera P, Leist M, Ferrando-May E. Apoptosis and necrosis: different execution of the same death. Biochem Soc Symp. 1999;66:69–73. doi: 10.1042/bss0660069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheridan AM, Bonventre JV. Cell biology and molecular mechanisms of injury in ischemic acute renal failure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2000;9:427–434. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200007000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vetterlein F, Petho A, Schmidt G. Distribution of capillary blood flow in rat kidney during postischemic renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:H510–H519. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.3.H510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basile DP, Fredrich K, Weihrauch D, Hattan N, Chilian WM. Angiostatin and matrix metalloprotease expression following ischemic acute renal failure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F893–F902. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00328.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan L, Borregaard N, Kjeldsen L, Moses MA. The high molecular weight urinary matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity is a complex of gelatinase B/MMP-9 and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL). Modulation of MMP-9 activity by NGAL. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37258–37265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mishra J, Ma Q, Kelly C, Mitsnefes M, Mori K, Barasch J, Devarajan P. Kidney NGAL is a novel early marker of acute injury following transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:856–863. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fine RN, Tejani A. Growth following renal transplantation in children. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:1959–1960. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guyot C, Karam G, Soulillou JP. Pediatric renal transplantation without maintenance steroids. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith ER, Zurakowski D, Saad A, Scott RM, Moses MA. Urinary biomarkers predict brain tumor presence and response to therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2378–2386. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]