Abstract

Objective

To assess the glucose disposition index (DI) using an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT; oDI) compared with the DI measured from the combination of the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic clamps (cDI) in obese pediatric subjects spanning the range of glucose tolerance.

Study design

Overweight/obese adolescents (n=185) with varying glucose tolerance (87 normal [NGT], 54 impaired [IGT], 31 with type 2 diabetes [T2DM] and 13 with type 1 diabetes [OT1DM]) completed an OGTT and both a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic and a hyperglycemic clamp study. Indices of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function were calculated, and four different oDI estimates were calculated as the products of insulin and C-peptide-based sensitivity and secretion indices.

Results

Mirroring the differences across groups by cDI, the oDI estimates were greatest in NGT and lowest in T2DM and OT1DM. The insulin-based oDI estimates correlated with cDI overall (r≥0.74, P<0.001) and within each glucose tolerance group (r≥0.40, P<0.001). Also, oDI and cDI predicted 2-h OGTT glucose similarly.

Conclusions

Oral disposition index is a simple surrogate estimate of β-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity that can be applied to obese adolescents with varying glucose tolerance in large-scale studies where the applicability of clamp studies is limited due to feasibility, cost and labor intensiveness.

Keywords: disposition index, beta cell function, obesity, pediatric, insulin sensitivity

Conditions associated with impairment in glucose homeostasis in pediatrics, including obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), are on the rise.1–4 Because these disorders involve impairment of both insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion, which are tightly coupled,5–7 reliable measures of insulin sensitivity and pancreatic β-cell function are needed. Even though the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp and the hyperglycemic clamp are considered the gold standards for measuring insulin sensitivity and secretion,8–9 respectively, they are labor intensive, costly and not suitable for large scale epidemiological or interventional studies. Furthermore, to evaluate β-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity, two separate clamps are needed; one a hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp for insulin sensitivity measurement, and another, the hyperglycemic clamp for insulin secretion measurement.7, 10 Therefore, due to the importance of simultaneously assessing insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion,5, 7, 11 simple estimates of the disposition index (DI) to describe insulin secretion relative to insulin sensitivity have been proposed for use in large scale studies which preclude the use of clamp studies and the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT).12–13 These estimates can be calculated from fasting and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) data and have been dubbed the oral disposition index (oDI).12 In longitudinal cohorts of adults without diabetes, baseline oDI is shown to be the strongest metabolic predictor of future diabetes and appears to differentiate those who progress from normal to abnormal glucose metabolism from non-progressors.14–15 We previously demonstrated that fasting surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity, namely 1/fasting insulin, correlated strongly with in vivo insulin sensitivity measured with the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp in obese youth.16 The aim of the current investigation was to assess simple estimates of oDI, based on fasting and OGTT-derived insulin sensitivity and secretion, in relation to clamp-measured DI (cDI) in overweight/obese adolescents with varying glucose tolerance, including diabetes.

METHODS

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh, and parental consent and child assent were obtained prior to any research procedure. A total of 185 overweight/obese youth (70 African American [AA], 109 Caucasian [C]; 6 biracial [BR]; 65 girls with untreated polycystic ovary syndrome; ages 8 to <20 years old; Tanner II–V), who had participated in our ongoing “Childhood Metabolic Markers of Adult Morbidity in Blacks” and “Childhood Insulin Resistance” grants, and had complete OGTT and hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic and hyperglycemic clamp data were included. Some of these participants were reported previously.10, 16–18 There were 87 with normal glucose tolerance (NGT) including 38 with PCOS, 54 with impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) including 27 with PCOS, 31 with a diagnosis of T2DM and negative GAD65 and IA2 antibodies, and 13 obese with type 1 diabetes mellitus (OT1DM) and positive GAD65 and IA2 antibodies. Among patients with T2DM, there were 7 on lifestyle therapy alone, 15 on metformin alone, 2 on insulin alone and 4 on metformin and insulin combined. Among OT1DM patients, there were 1 on lifestyle therapy alone, 3 on insulin alone, 2 on metformin alone and 7 on insulin and metformin combined. A glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) above 8.5% was an exclusion criterion for subjects with diabetes for patient safety reasons in undergoing the experimental procedures. Participants were recruited through advertisements in newspapers, buses and fliers posted on the medical campus, and the outpatient clinics in the Weight Management and Wellness Center and the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology. Participants’ health status was assessed by history, physical exam and routine hematologic and biochemical tests. Stage of pubertal development was determined by physical examination according to Tanner criteria19 and confirmed with measurement of plasma testosterone in males, estradiol in females and dehyroepiandrosterone sulfate in both males and females. Overweight was defined as body mass index (BMI) ≥ 85th and < 95th percentile and obesity was BMI ≥ 95th percentile according to age and sex-specific percentiles of BMI.20 Tests were conducted at the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center (PCTRC) of the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

A 3-hr hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp was performed after a 10–12 hour overnight fast following admission to the PCTRC the afternoon prior. The details of the clamp procedures have been described previously.17, 21 Briefly, participants were advised to consume a standard diet of 55% carbohydrate, 30% fat and 15% protein the week prior to the clamp study. In patients with diabetes, irrespective of type, metformin and long-and/or intermediate-acting insulin were discontinued 48 hours prior to the clamp procedures and 24 hours prior to the OGTT studies, as described.10, 22 Subcutaneous injections of rapid-acting insulin were used to manage glycemia during this withdrawal period, day and night, with the last dose given 6–8 hours prior to study procedures. Clamp constant-rate insulin infusion (80 mu/m2/min) was initiated following collection of 4 baseline blood samples every 10 minutes on the morning of the clamp study. Blood glucose was clamped at 100 mg/dL (5.5 mmol/L) by a variable rate infusion of 20% dextrose in water. Peripheral insulin sensitivity was calculated during the last 30 min of the clamp to be equal to the rate of exogenous glucose infusion divided by the steady-state clamp insulin concentration and expressed per kg body weight (mg/kg/min per μu/mL).

On a separate occasion, one to three weeks apart, and in a random order, a 2-hr hyperglycemic clamp (225 mg/dL) was performed after a 10–12 hour overnight fast. The details of the clamp procedures have been described previously.8, 17, 23 Diet and glycemia management was the same as above for the euglycemic clamp. Briefly, plasma glucose concentration was rapidly increased to ~225 mg/dL with a bolus dextrose infusion and maintained with a variable rate infusion of 20% dextrose in water. First phase insulin (μU/mL) was calculated as the mean insulin concentration of five measurements at times 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10 and 12.5 minutes of the clamp.

Either the day preceding one of the clamp procedures or on a separate visit within a 1 to 3 week period, assigned at random, a 120-min OGTT (1.75 g/kg glucola, maximum 75 g) was performed in the morning after a 10–12 hour overnight fast. Diet and glycemia management was the same as described above. Blood samples were obtained at −15, 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min for determination of glucose, insulin and C-peptide as described previously.22, 24

Plasma glucose was measured by the glucose oxidase method (Yellow Springs Instrument Co., Yellow Springs, OH). Plasma insulin was analyzed by a commercial radioimmunoassay (Linco catalog no. 1011, St. Charles, MO) as before.17 C-peptide concentration was measured using a double-antibody radioimmunoassay (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY). Pancreatic auto-antibodies (GAD65 and IA2) were measured to distinguish obese youth with auto-immune type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes as reported before.10

Fasting glucose (GF), insulin (IF), and C-peptide (CF) concentrations were derived from the baseline measurements of the OGTT. From IF and GF, the homeostasis model assessment for insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IS) was calculated using the HOMA2 calculator at http://www.dtu.ox.ac.uk.25–26 The insulinogenic index and comparable C-peptide index (ΔI30/ΔG30, ΔC30/ΔG30) were calculated as the ratio of the incremental change of insulin, glucose or C-peptide from 0 to 30 minutes of the OGTT as previously reported.24, 27–28 From these indices of insulin sensitivity and insulin or C-peptide secretion, oDI estimates were calculated according to the following formulae: IF oDI = 1/IF × ΔI30/ΔG30, HOMA oDI = HOMA-IS × ΔI30/ΔG30, CF oDI = 1/CF × ΔC30/ΔG30, GFCF oDI = GF/CF × ΔC30/ΔG30. The cDI (mg/kg/min) was calculated as the product of first phase insulin from the hyperglycemic clamp (μu/mL) and insulin sensitivity from the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp (mg/kg/min per μu/mL) as before.10, 17

Statistical analyses

Differences in continuous variables across groups were determined by univariate analysis of variance using Bonferroni post-hoc correction in SPSS (PASW 18, Chicago, IL). Spearman correlation coefficients were used because most variables were not distributed normally, to examine the relationship between oDI estimates and clamp measures overall and within each glucose tolerance group separately. Linear regression analysis with either cDI or each of the oDI estimates was performed to compare the proportion of variation in 2-hr OGTT glucose concentration contributed by oDI versus cDI. All DI values were log-transformed for linear regression analysis, and the regression was performed in the total group in order to include a wide range of values of DI. C-peptide data were unavailable for 24 participants (9 NGT and 15 IGT) due to loss of banked samples during the transition from one laboratory location to another. Data are presented as mean ± SE. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant and P ≤ 0.10 was considered a trend.

RESULTS

Age, sex, Tanner stage and race were similar across groups (Table I). Mean BMI and BMI percentiles were different among the four groups due primarily to lower BMI and BMI percentile in the OT1DM. There was also a trend (P=0.07) for fat mass differences across the groups, with the lowest value in OT1DM. However, % body fat was not different among the groups. As expected, HbA1C was higher in T2DM and OT1DM compared with NGT and IGT.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics by glucose tolerance group.

| NGT (1) | IGT (2) | T2DM (3) | OT1DM (4) | P | P, post-hoc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=87 | n=54 | n=31 | n=13 | ANOVA | 1 vs 2 | 1 vs 3 | 1 vs 4 | 2 vs 3 | 2 vs 4 | 3 vs 4 | |

| Age | 14.9 ± 0.2 | 14.6 ± 0.3 | 15.1 ± 0.3 | 14.1 ± 0.7 | 0.40 | ||||||

| Sex (male) | 43% | 33% | 42% | 38% | 0.73 | ||||||

| Tanner stage (IV–V) | 84% | 81% | 90% | 77% | 0.53 | ||||||

| Race (% AA,C,BR) | 37, 57, 6 | 35, 63, 2 | 48, 52, 0 | 31, 69, 0 | 0.50 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.9 ± 0.6 | 36.8 ± 0.9 | 36.6 ± 0.9 | 30.8 ± 1.4 | 0.01 | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| BMI percentile | 97.8 ± 0.3 | 98.7 ± 0.1 | 98.9 ± 0.1 | 95.7 ± 1.1 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.01 | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Fat mass (kg)* | 40.8 ± 1.3 | 43.3 ± 1.7 | 41.0 ± 1.9 | 33.6 ± 3.3 | 0.07 | ns | ns | ns | ns | 0.05 | ns |

| Percent body fat* | 43.2 ± 0.7 | 44.2 ± 0.7 | 42.4 ± 1.2 | 40.3 ± 2.4 | 0.20 | ||||||

| HbA1C (%) | 5.3 ± 0.04 | 5.4 ± 0.06 | 6.6 ± 0.13 | 6.3 ± 0.29 | <0.001 | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ns |

9 subjects (3 NGT, 2 IGT, 4 T2DM) did not have fat mass or percent body fat data available.

For cDI and each of the oDI estimates, there were significant differences across glucose tolerance groups (Table II). In particular, cDI and oDI estimates were greatest in NGT, lower in IGT and lowest in T2DM and OT1DM. All oDI estimates mirrored cDI detected statistical differences among the groups (Table II).

Table 2.

Differences across groups in cDI, insulin-based oDI and C-peptide-based oDI, including the separate components of insulin sensitivity and secretion indices used to calculate each.

| NGT (1) | IGT (2) | T2DM (3) | OT1DM (4) | P | P, post-hoc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA | 1 vs 2 | 1 vs 3 | 1 vs 4 | 2 vs 3 | 2 vs 4 | 3 vs 4 | |||||

| First phase insulin | 237 ± 19 | 232 ± 19 | 110 ± 24 | 37 ± 5 | <0.001 | ns | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | ns |

| Insulin sensitivity | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 0.028 | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| cDI | 488 ± 32 | 344 ± 28 | 109 ± 11 | 112 ± 14 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.011 | ns |

| ΔI30/ΔG30 | 4.59 ± 0.42 | 3.28 ± 0.23 | 1.42 ± 0.24 | 0.33 ± 0.06 | <0.001 | 0.064 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.034 | 0.008 | ns |

| 1/IF | 0.037 ± 0.002 | 0.027 ± 0.002 | 0.029 ± 0.004 | 0.047 ± 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.009 | ns | ns | ns | 0.001 | 0.007 |

| IF oDI | 0.138 ± 0.01 | 0.079 ± 0.006 | 0.032 ± 0.004 | 0.014 ± 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.019 | ns |

| ΔI30/ΔG30 | as above | ||||||||||

| HOMA-IS | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.065 | ns | ns | 0.007 | 0.018 |

| HOMA oDI | 1.26 ± 0.09 | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.015 | 0.015 | ns |

| ΔC30/ΔG30 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.003 | <0.001 | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 | ns | 0.05 | ns |

| 1/CF | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | <0.001 | ns | 0.07 | 0.04 | ns | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| CF oDI | 0.048 ± 0.003 | 0.033 ± 0.003 | 0.015 ± 0.002 | 0.010 ± 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.003 | ns |

| ΔC30/ΔG30 | as above | ||||||||||

| GF/CF | 36.5 ± 3.1 | 28.8 ± 2.0 | 30.4 ± 1.6 | 82.9 ± 23.6 | <0.001 | ns | ns | <0.001 | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| GFCF oDI | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.011 | ns |

Insulin (μu/mL), C-peptide (ng/mL), glucose (mg/dL), insulin sensitivity (mg/kg/min per μu/mL) and cDI (mg/kg/min).

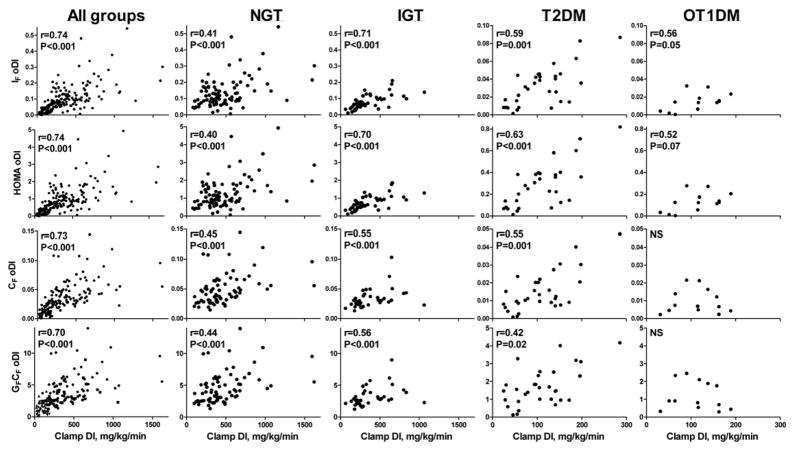

In Figure 1, rows 1 and 2 depict the correlations between insulin-based oDI estimates (IF oDI, HOMA oDI) and cDI. With all the groups combined, cDI correlated strongly with the insulin-based oDI estimates (r≥0.74, P<0.001 for both). However, the strength of the correlations varied across groups, with the highest correlations in IGT subjects and the lowest in NGT.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots with correlations of the four oral DI (oDI) estimates (rows 1 and 2: insulin-based oDI, rows 3 and 4: C-peptide-based oDI) compared with clamp DI (cDI) in all the groups combined and in each glucose tolerance category (columns) separately.

In Figure 1, rows 3 and 4 illustrate the correlations between C-peptide-based oDI estimates (CF oDI, GFCF oDI) and cDI. With all the groups combined, cDI correlated with the C-peptide-based oDI estimates (r ≥0.70, P<0.001 for both). However, within each glucose tolerance group separately, the correlations were significant in NGT, IGT and T2DM, but not in OT1DM.

When NGT, IGT and T2DM were considered with the OT1DM group removed, overall correlations between cDI and the oDI estimates were similar to those reported above for the total group (n=172: IF oDI, r=0.70; HOMA oDI, r=0.70; CF oDI, r=0.69; GFCF oDI, r=0.66; P<0.001 for all). Correlations between cDI and oDI estimates of NGT and IGT combined, excluding both diabetic groups, were lower (n=141: IF oDI, r=0.55; HOMA oDI, r=0.54; CF oDI, r=0.50; GFCF oDI, r=0.50; P<0.001 for all).

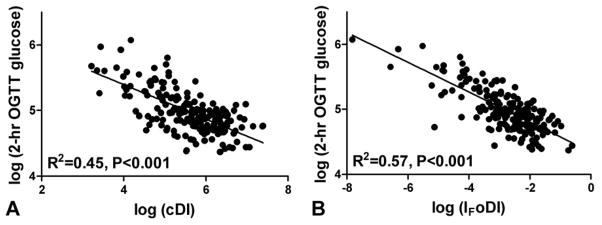

In a linear regression analysis with OGTT 2-hr glucose concentration as the dependent variable, IF oDI could be substituted for cDI with little change in the R2 achieved (Figure 2). Similarly, the HOMA oDI, CF oDI and GFCF oDI produced R2 values of 0.58, 0.54 and 0.45 (P<0.001 for all), respectively, for prediction of 2-hr OGTT glucose concentration.

Figure 2.

Linear regression analysis of log-transformed clamp DI (cDI) (A) or oral DI derived from 1/fasting insulin × insulinogenic index (IF oDI) (B) on log-transformed 2-hr glucose concentration from the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

DISCUSSION

The recent proposal for use of OGTT-based disposition index estimates necessitates the testing of their applicability in various populations. We investigated four different oDI estimates in obese adolescents ranging from normal to impaired glucose tolerance to diabetes. The primary findings are: 1) all four oDI estimates distinguished the same group differences (NGT vs. IGT vs. T2DM vs. OT1DM) as those determined with cDI, 2) the insulin-based oDI estimates (IF oDI, HOMA oDI) correlated with cDI within each separate glucose tolerance category: NGT, IGT, T2DM and OT1DM, and 3) oDI predicted 2-hr glucose concentration during the OGTT similarly as the cDI.

Longitudinal studies of the progression of worsening glucose tolerance in adults have indicated that β-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity declines even prior to the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and is a key component in the development of hyperglycemia.29–30 Furthermore, oDI in adults was shown to be the strongest metabolic predictor of progression through IGT to diabetes, more so than insulin sensitivity, fasting glucose or OGTT glucose concentrations alone.12, 14–15 In adulthood, declining insulin sensitivity is coupled with increased β-cell function in those maintaining glucose homeostasis, whereas in those who progress to IGT and eventual diabetes, insulin sensitivity may decline similarly, but with a decline also in β-cell function.29 Therefore, assessment of DI which is a measure of β-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity is critical for describing the risk for and progression of diabetes.

Despite the widespread use of oral DI in adult studies, data are limited in pediatrics. One study assessed the usefulness of oDI in pediatrics,31 after introducing the ISSI-213 (Matsuda’s insulin sensitivity index × OGTT insulin area under the curve/glucose area under the curve) and the IF oDI presented here, using IVGTT DI as the reference method, and found both estimates to be significantly correlated to IVGTT DI, but with r values ≤ 0.32. Furthermore, the study identified that ISSI-2 had a stronger relationship than IF oDI to IVGTT DI.31 In contrast, in the present study we found greater overall correlations (r≥0.73, P<0.001) among oDI estimates and the clamp DI; and we identified similar, if not greater, correlations to cDI with IF oDI (r=0.73 overall) than with ISSI-2 (overall, r=0.68; NGT, r=0.28; IGT, r=0.53; T2DM, r=0.66; OT1DM, r=0.54; P<0.01 for all, except OT1DM where p=0.06; data not shown). A possible explanation for the different correlations reported by Retnakarna et al31 compared with the present report is that subjects of this previous study were younger (mean age, 11.1 years), Latino and none had diabetes nor were any indicated to have IGT, unlike the present report. Furthermore, this previous study utilized minimal model analysis of a frequently-sampled IVGTT which provides insulin sensitivity and acute insulin secretion from a single test, whereas the present report used the combination of the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic and hyperglycemic clamps which were conducted on separate days to derive insulin sensitivity and secretion, respectively.

The present report supports the prudent use of these oDI estimates for describing β-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity in pediatric populations with varying states of glucose tolerance. In IGT compared with NGT the cDI was ~30% lower; likewise the various oDI estimates ranged from 31–43% decrement in IGT relative to NGT. Further, cDI was 78% lower in T2DM compared with NGT, similar to the 63–77% difference between NGT and T2DM using oDI. In addition, the oDI estimates predicted the 2-hr glucose concentration of the OGTT, a key criterion for the diagnosis of diabetes, similarly to cDI. The similar, if not greater, R2 produced when IF oDI was substituted for cDI in a linear regression analysis may contribute to the observations in the longitudinal studies in adults that oDI is the ideal metabolic predictor of subsequent diabetes.12, 14

Regarding correlation strength between clamp and OGTT-based estimates of DI, the correlation strengths achieved with oDI reported here and by others31 were relatively modest in comparison with the higher correlations reported for indices of insulin sensitivity alone.16 Lower correlation strength with DI estimates may be due to the inherent variability in measures of insulin secretion relative to the lesser variability of insulin sensitivity measures, as previously discussed,6 and the hyperbolic relationship between insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion which defines DI.7, 11, 29 The lack of a significant correlation between C-peptide based oDI estimates and cDI in the OT1DM group may be due to the violation of the basic assumptions of disposition index: that insulin secretion and sensitivity are related in a feedback loop where when one goes up, the other goes down.29, 32 Instead, insulin secretion is deficient (which is made apparent by C-peptide measurement), unrelated to changes in insulin sensitivity in youth with type 1 diabetes.

The strengths of this study include the use of 2 separate clamp experiments, one to measure insulin sensitivity and the other to measure first phase insulin secretion, both considered the “gold standard” for their respective measurements, to calculate clamp DI as the reference method. Also, the present study includes adolescents with varying glucose tolerance, which has not been reported before, with comparison of oDI estimates to cDI separately in each glucose tolerance group. A potential limitation of our study is the use of a single OGTT because of our prior finding of its poor reproducibility for the 2-h glucose concentration.24 However, in that study we found that the difference between discordant and concordant OGTT pairs was reflected in the DI. Because oDI is the measure of interest in the current study, we believe that the current results would not have been significantly different had we used 2 OGTT tests. Furthermore, almost all pediatric studies have used a single OGTT33–35 and very few adult studies use two OGTTs.36 Another limitation of this study is that the patients with diabetes were on a variety of treatments including metformin and insulin. Thus, the insulin-based fasting and oDI results in diabetic subjects who required insulin may be somewhat modulated with the exogenous insulin. To overcome this potential problem, our protocol for metformin and insulin withdrawal was uniform in all diabetic patients, and designed such that the last dose of rapid-acting insulin was given 6–8 hours prior to any experimental procedures. From an ethical perspective it is not possible to perform the clamp investigations at the time of diagnosis before the institution of any therapy. Also, the OT1DM group had a lower level of obesity (lower BMI, BMI percentile) which could confound interpretation of the differences reported in this group; however, this group was still classified as obese (mean BMI percentile > 95th) similar to the other three groups. Finally, these results in diabetic patients may not be applicable to those with less well-controlled glycemia, as HbA1C >8.5% was an exclusion criterion here.

We found significant, albeit moderate, correlations between clamp-measured and OGTT-derived estimates of β-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity in adolescents with NGT, IGT and controlled diabetes. These oDI estimates detected group differences in β-cell function similar to the cDI, had analogous predictive power to cDI for the 2-hr glucose concentration of the OGTT, and identified comparable decrements in β-cell function across the glucose intolerant groups as did the cDI. Notably, the IF oDI, which was arguably the simplest estimate of oDI and has been previously published,31 produced some of the strongest correlations to cDI observed here. Such data would justify the use of fasting and OGTT-derived estimates, such as IF oDI, to assess β-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity, but only in large scale prevention/intervention studies, where it is important to assess the effectiveness of any intervention in modifying the pathophysiological mechanisms of T2DM in high risk youth.

Acknowledgments

These studies would not have been possible without the nursing staff of the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center, the devotion of the research team (Nancy Guerra, CRNP, Kristin Porter, RN, Sally Foster, RN, CDE, Lori Bednarz, RN, CDE), the laboratory expertise of Resa Stauffer and Jackie Jones, and, most importantly, the commitment of the study participants and their parents.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lewy V, Danadian K, Arslanian SA. Early metabolic abnormalities in adolescents with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) Pediatr Res. 1999;45:93a. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.109603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:242–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmert MR, Gordon CM, Kartashov AI, Legro RS, Emans SJ, Dunaif A. Screening for abnormal glucose tolerance in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2002;87:1017–23. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberti G, Zimmet P, Shaw J, Bloomgarden Z, Kaufman F, Silink M, et al. Type 2 diabetes in the young: The evolving epidemic - the International Diabetes Federation Consensus Workshop. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1798–811. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahren B, Pacini G. Importance of quantifying insulin secretion in relation to insulin sensitivity to accurately assess beta cell function in clinical studies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;150:97–104. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrannini E, Mari A. Beta cell function and its relation to insulin action in humans: A critical appraisal. Diabetologia. 2004;47:943–56. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1381-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn SE. Regulation of beta-cell function in vivo: From health to disease. Diabetes Rev. 1996;4:372–89. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arslanian SA. Clamp techniques in paediatrics: What have we learned? Horm Res. 2005;64:16–24. doi: 10.1159/000089313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Defronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique - method for quantifying insulin-secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:E214–E23. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tfayli H, Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian S. Phenotypic type 2 diabetes in obese youth: insulin sensitivity and secretion in islet cell antibody-negative versus-positive patients. Diabetes. 2009;58:738–44. doi: 10.2337/db08-1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergman RN, Ader M, Huecking K, Van Citters G. Accurate assessment of beta-cell function - the hyperbolic correction. Diabetes. 2002;51:S212–S20. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Utzschneider KM, Prigeon RL, Faulenbach MV, Tong J, Carr DB, Boyko EJ, et al. Oral disposition index predicts the development of future diabetes above and beyond fasting and 2-h glucose levels. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:335–41. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Retnakaran R, Shen S, Hanley AJ, Vuksan V, Hamilton JK, Zinman B. Hyperbolic relationship between insulin secretion and sensitivity on oral glucose tolerance test. Obesity. 2008;16:1901–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyssenko V, Almgren P, Anevski D, Perfekt R, Lahti K, Nissen M, et al. Predictors of and longitudinal changes in insulin sensitivity and secretion preceding onset of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:166–74. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdul-Ghani MA, Williams K, DeFronzo RA, Stern M. What is the best predictor of future type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1544–8. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George L, Bacha F, Lee S, Tfayli H, Andreatta E, Arslanian S. Surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity in obese youth along the spectrum of glucose tolerance from normal to prediabetes to diabetes. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2011;96:2136–45. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacha F, Lee S, Gungor N, Arslanian S. From prediabetes to type 2 diabetes in obese youth: Pathophysiological characteristics along the spectrum of glucose dysregulation. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2225–31. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S, Guerra N, Arslanian S. Skeletal muscle lipid content and insulin sensitivity in black versus white obese adolescents: Is there a racial difference? J Clin Endocr Metab. 2010;95:2426–32. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanner JM. Growth and endocrinology in the adolescent. In: Gardner L, editor. Endocrine and Genetic Diseases of Childhood. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1969. pp. 19–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosner B, Prineas R, Loggie J, Daniels SR. Percentiles for body mass index in US children 5 to 17 years of age. J Pediatr. 1998;132:211–22. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burns SF, Lee S, Arslanian SA. In vivo insulin sensitivity and lipoprotein particle size and concentration in black and white children. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2087–93. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tfayli H, Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian S. Islet cell antibody-positive versus-negative phenotypic type 2 diabetes in youth does the oral glucose tolerance test distinguish between the two? Diabetes Care. 2010;33:632–8. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacha F, Gungor N, Lee S, Arslanian SA. In vivo insulin sensitivity and secretion in obese youth what are the differences between normal glucose tolerance, impaired glucose tolerance, and type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009;32:100–5. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Libman IM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Bartucci A, Robertson R, Arslanian S. Reproducibility of the oral glucose tolerance test in overweight children. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2008;93:4231–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–95. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian SA. Measures of beta-cell function during the oral glucose tolerance test, liquid mixed-meal test, and hyperglycemic clamp test. J Pediatr. 2008;152:618–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utzschneider KM, Prigeon RL, Tong J, Gerchman F, Carr DB, Zraika S, et al. Within-subject variability of measures of beta cell function derived from a 2 h OGTT: Implications for research studies. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2516–25. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0819-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahn SE. Clinical review 135 - the importance of beta-cell failure in the development and progression of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2001;86:4047–58. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cnop M, Vidal J, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM, Carr DB, Schraw T, et al. Progressive loss of beta-cell function leads to worsening glucose tolerance in first-degree relatives of subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:677–82. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Goran MI, Hamilton JK. Evaluation of proposed oral disposition index measures in relation to the actual disposition index. Diabetic Med. 2009;26:1198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mari A, Ahren B, Pacini G. Assessment of insulin secretion in relation to insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr. 2005;8:529–33. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000171130.23441.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahon JL, Sosenko JM, Rafkin-Mervis L, Krause-Steinrauf H, Lachin JM, Thompson C, et al. The Trialnet Natural History Study of the Development of Type 1 Diabetes: Objectives, design, and initial results. Pediatr Diabetes. 2009;10:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stumvoll M, Mitrakou A, Pimenta W, Jenssen T, Yki-Jarvinen H, Van Haeften T, et al. Use of the oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin release and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:295–301. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shield JPH, Ford AL, Hunt LP, Cooper A. What reduction in BMI SDS is required in obese adolescents to improve body composition and cardiometabolic health? Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:256–61. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.165340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindstrom J, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, Rastas M, Salminen V, Eriksson J, et al. The Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3230–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]