Abstract

Emerging data in the field of cardiac development as well as repair and regeneration indicate a complex and important interplay between endocardial, epicardial, and myofibroblast populations that is critical for cardiomyocyte differentiation and postnatal function. For example, epicardial cells have been shown to generate cardiac myofibroblasts and may be one of the primary sources for this cell lineage during development. Moreover, paracrine signaling from the epicardium and endocardium is critical for proper development of the heart and pathways such as Wnt, FGF, and retinoic acid signaling have been shown to be key players in this process. Despite this progress, interactions between nonmyocyte cells and cardiomyocytes in the heart are still poorly understood. We review the various nonmyocyte-myocyte interactions that occur in the heart and how these interactions, primarily through signaling networks, help direct cardiomyocyte differentiation and regulate postnatal cardiac function.

Keywords: heart, cardiomyocyte, endocardium, epicardium, cardiac fibroblast

INTRODUCTION

Given that nonmyocytes outnumber cardiomyocytes in the heart, the dearth of information on these cells is striking. There has been much focus on the role of the endocardium during cardiac development including seminal findings show that these cells generate valvular tissue through an endocardial-mesenchymal transformation (EMT). Moreover, recent data using novel fate-mapping approaches has identified the epicardium as an important source of cardiac fibroblasts in the developing heart. Cardiac fibroblasts play important roles in postnatal cardiac remodeling after injury and stress by helping to stabilize myocardial structure and form scar tissue. Despite these findings, less is understood about the role of nonmyocardial lineages in comparison to cardiomyocytes in both heart development and the postnatal response to injury and repair.

There has been much attention paid to how signaling from the endocardium and epicardium to the developing myocardium promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation. From these studies, it is clear that important paracrine signaling pathways such as Wnt, FGF, and retinoic acid (RA) play important roles in balancing the proliferative and differentiation processes in the developing myocardium. What is less clear is whether any of these pathways or other pathways are reactivated in the adult heart after injury and what their role, if any, is in directing the cardiac injury response. These are key questions as the mammalian heart generally repairs itself through scar formation which involves activation and expansion of cardiac fibroblasts but not cardiomyocytes in the adult. This is quite different than lower vertebrates such as zebrafish which can repair efficiently through replacement of injured or lost myocardium through cardiomyocyte proliferation. Moreover, in zebrafish it has been shown that the epicardium can respond even at a distance to dramatic cardiac injury through activation of pathways critical for promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation such as RA. Whether a similar mechanism exists in mammals is at this point unknown although a recent report showed that Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the epicardium is essential for cardiac repair after injury by regulating epicardial cell expansion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition 1.

In this review, we will highlight recent data on the importance of nonmyocyte lineages in the heart including cardiac fibroblasts, endocardium, and epicardium. Recent studies have demonstrated important plasticity in some of these nonmyocyte cell lineages which complicates the study of these cells but also opens the door to potential reprogramming of these cells in a setting of cardiac injury and stress to promote cardiomyocyte replacement. Although such ideas are still untested, our increasing knowledge of nonmyocyte lineages in the heart will undoubtably increase our overall understanding of both cardiac development as well as the ability of the adult heart to respond to stress and injury.

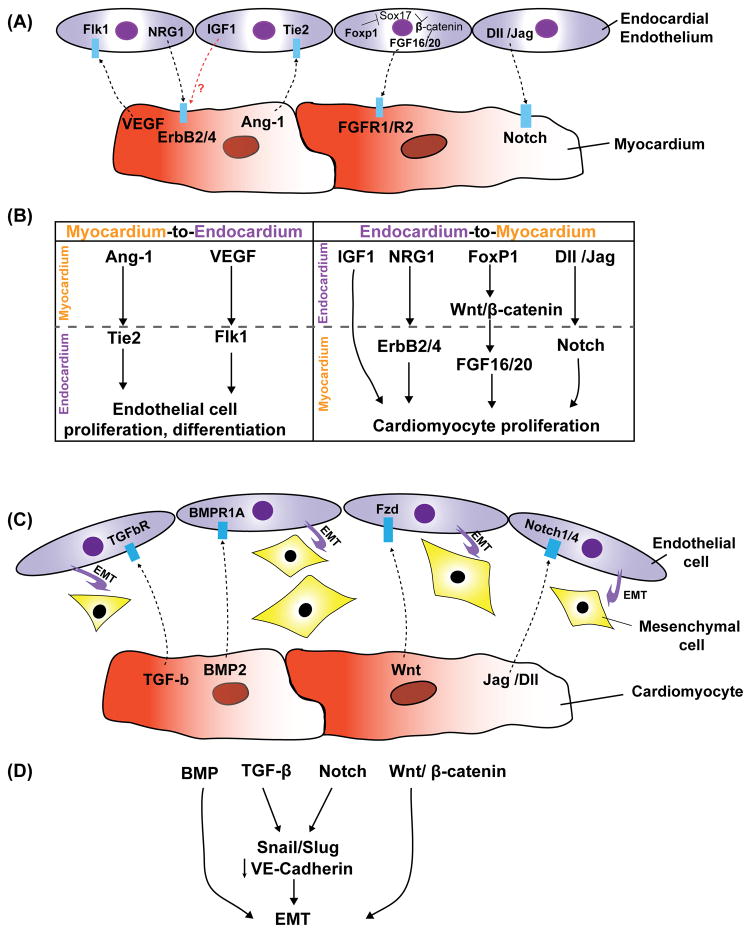

Dynamic interactions between endocardium and myocardium

The endothelial cells closely juxtaposed to the myocardium in the heart called the endocardium, are derived from early cardiac mesoderm 2. However the origin of endocardial cells has been controversial. Using mouse fate-mapping studies and ex vivo approaches, one model suggests that endocardial and myocardial cells are derived from a common multipotent progenitor within the cardiac mesoderm 3–7. A second model is largely based on observations in zebrafish and chick embryos and suggests that endocardial cells in the cardiac mesoderm are pre-specified in the primitive streak, prior to migration to the cardiac cresent, to become endocardium 3, 8, 9. Through a process of endothelial-mesenchymal transition, the endocardium is also an important source of mesenchymal cells during cardiac valve development. As outlined below, one of the critical roles for the endocardium during heart development is to regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation. Multiple pathways are important for endocardial-myocardial signaling and many of these act as mitogens as well as promoting cardiomyocyte differentiation.

Signaling from the endocardium regulates cardiomyocyte differentiation and proliferation

Evidence for the essential role of endocardium in orchestrating myocardial cell maturation and function come from studies on the NRG-1/ErbB2/B4, Notch, VEGF, Ang-1 and FGF signaling pathways. The vertebrate heart develops initially as the linear tube, consisting of two epithelial layers, the endocardium and the myocardium, widely separated by an extracellular matrix called the cardiac jelly 10. After looping morphogenesis of the cardiac linear tube to form the multi-chambered vertebrate heart, the process of trabeculation occurs to help increase contractility and direct blood flow. Evidence for the necessity of the underlying endocardium for trabeculi formation comes from studies using the zebrafish cloche mutant which lacks all endocardium and most other endothelial cells 11. The cloche mutant displayed markedly reduced contractility with distended atria and collapsed ventricles due to failure to develop trabeculation within the ventricle 11, 12. Further evidence of the importance of the endocardium in trabecular development is highlighted by several mouse mutants which lack or have greatly diminished cardiac trabeculi while still maintaining the presence of endocardium. Neuregulins (NRG) are a family of growth factors synthesized by endothelial cells 13. It has been shown that NRG-1 is able to promote cell survival and growth via activation of ErbB receptors 13, 14. NRG-1 is expressed in the endocardium where it is released as a paracrine signal that activates the tyrosine kinase receptor ErbB4 and its coreceptor ErbB2, expressed on adjacent cardiomyocytes. Activation of the ErbB2/ErbB4 receptor complex by NRG is required for trabeculation of the primitive heart 15–17. As in the cloche mutant zebrafish embryo, global loss of NRG-1 in the mouse also resulted in absence of ventricular trabeculation, with subsequent failure of myocardial maturation and embryonic lethality 15–18. In mouse embryos with homozygous null alleles for either of the NRG-1 myocardial receptors, ErbB2 or ErbB4, the heart tube formed and looped normally, but trabeculation was blocked 15, 16. Conversely, using the whole mouse embryo culture system, Hertig and colleagues showed that injection of NRG-1 through the ventricular wall into the developing heart led to hyper-trabeculation 19. NRG-1 can promote the proliferation, survival, and hypertrophic growth of cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes 20, which may explain why this growth factor is essential for normal trabeculation. IGF-1 is also secreted by the endocardium 21, 22. While loss of IGF-1 has no apparent effect on cardiomyocytes by itself, IGF-1 interacts with NRG-1 synergistically to promote ventricular cardiomyocyte proliferation and maturation 19. The NRG-1/ErbB4 pathway has recently been shown to promote proliferation in differentiated cardiomyocytes 23. Bersell and colleagues showed that exposure of less differentiated mononuclear cardiomyocytes, but not more differentiated binucleated cells, either in vitro or in vivo, to NRG-1 caused them to proceed through the cell cycle. Global loss of the receptor ErbB4 resulted in a reduction in cardiomyocyte proliferation whereas increased ErbB4 expression enhanced cardiomyocyte proliferation 23. NRG-1 also promoted cardiac regeneration after ischemic injury presumably through promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation in these studies. Thus, the NRG-1/ErbB4 pathway may be a promising new therapeutic target for promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation and regeneration in the setting of injury and disease.

Another important pathway in endocardium development is Notch signaling. Ventricular Notch1 activity is highest in presumptive trabecular endocardium at E8.5 and mutant embryos with endocardial-specific deletion of RBPJk or Notch1 showed impaired trabeculation and reduced EphrinB2, NRG1 and BMP10 expression 24. Using in vitro whole embryo culture system, Grego-Bessa and colleagues showed that exogenous BMP10 rescued myocardial proliferation in RBPJk deficient hearts, while exogenous NRG1 rescued myocardial differentiation defects in these mutants 24.

The tyrosine kinase receptor VEGFR-2 (also known as Flk-1) is expressed at an early stage in all endothelial cells, including the endocardium. Mutant embryos deficient in Flk-1 expression lacked an obvious endothelial lineage and also lacked cardiac trabeculation resulting in embryonic demise by E9.5 12, 25. Tie-2 (also known as Tek) is an additional tyrosine kinase receptor expressed in endocardial cells. Binding of angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1), which is expressed in the myocardium, is required for Tie-2 mediated initial differentiation and proliferation of endocardium. Germline deletion of Ang-1 or Tie-2 causes embryonic lethality in mouse 26–28. Notably, the initial differentiation and assembly of endothelial cells is unperturbed in these mutants 26–28. Tie2 null mutant embryos underwent normal vasculogenesis, but died by E10.5 as a result of hemorrhaging and cardiac failure. The endocardial lining was poorly formed and had a collapsed appearance, resulting in markedly diminished myocardial trabeculation 26. Moreover, Ward and colleagues showed that over-expression of Ang-1 in myosin heavy chain a-expressing cells under control of doxycycline led to embryonic lethality between E12.5-15.5 due to dilated atria, thinning of the myocardial wall and lack of coronary vessels 29. However, one concern with these studies is that Tie-2 and Ang-1 are also expressed in the extra-embryonic tissues, such as placental endothelium 30. Thus the lethality of Tie-2 mutants might be due to the defects in placenta development. These studies suggest that Ang-1 produced by the myocardium influences the development of the adjacent endocardium which, in turn, provides key paracrine signals required for normal myocardial trabeculation.

FGF signaling is also an important pathway that regulates cardiac development through the paracrine activity of ligands expressed in the endocardium 31–33. FGF-9, FGF-16, and FGF-20 are all expressed in the endocardium during cardiac development 31, 33. These FGFs signal to the myocardium through FGFR1 and FGFR2, stimulating myocyte proliferation and differentiation. Recently, Zhang and colleagues showed that endocardial loss of the transcription factor Foxp1 using Tie2-cre mediated excision led to embryonic lethality with reduced myocardial proliferation and a hypoplastic myocardium 33. Decrease expression of FGF3/FGF16/FGF17/FGF20 was observed in the embryonic heart with the endocardial specific deletion of Foxp1. Moreover, the loss of myocardial proliferation could be rescued by addition of exogenous FGF20 33. Together, these studies suggest that the endocardium regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and maturation in a paracrine manner.

Signaling from cardiomyocytes regulates endocardial-mesenchymal transformation

Endocardial cushions are formed in the outflow (OFT) and atrioventricular canal (AVC) regions of the embryonic heart, in part, by EMT of the endocardium to mesenchyme 34. Multiple signaling pathways and transcription factors regulate this EMT process and subsequent cardiac valve development including TGF-β, BMP, Wnt and Notch signaling pathways 35, 36.

During mouse heart development, TGF-β2 is expressed in the endocardium and myocardium of the OFT and AV regions at the time when EMT occurs 37–39. Absence of TGF-β2 in mice results in abnormal valve leaflets and septa that derive from endocardial cushion tissue 35, 36. Using explanted chick endocardial cushions cultured on collagen gels, Potts and colleagues showed that inhibition of TGF-β3 blocked the EMT in AV endocardium co-cultured with associated myocardium 40. Nakajima and colleagues also showed that the expression of TGF-β3 in AV endocardium was induced by myocardial derived signals other than TGF-β3 and that TGF-β3 functioned in an autocrine manner to induce phenotypic changes in endothelial cells 41. TGF-β activity has been associated with Wnt/β-catenin pathway in the induction of EMT in mice 40. Mice lacking β-catenin in the developing endothelium through Tie2-cre mediated deletion failed to form AVC endocardial cushions due to defective EMT. In zebrafish, over-expression of Wnt inhibitors APC or DKK1 inhibited AVC endodardial cushion formation 42. These results demonstrate that TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin signaling are important to induce EMT, a process critical for formation of endocardial cushions and cardiac valves in the developing heart. However the interplay between these pathways has not been well defined and is likely important for proper valve development in the heart.

BMPs are members of the TGF-β growth factor superfamily and are also expressed in the myocardium adjacent to the endocardial cushions where they act synergistically with TGF-β to initiate EMT 43–45. During murine cardiogenesis, BMP2 and BMP4 are expressed in the myocardium of the OFT and AVC regions 46, 47. BMP2 treatment of AVC explants enhances TGF-β-induced EMT 45. This suggests that BMP is a myocardium-derived inductive signal that regulates AV cushion EMT. Supporting this concept, Sugai and colleagues indicated that BMP2 could substitute for myocardium to induce EMT, TGF-β2 expression, and initiate EMT in cultured mouse AV endothelial monolayer 44. Mice lacking myocardial BMP2 expression exhibited no AVC endocardial cushion mesenchyme formation 48. Deletion of BMP receptor-1A (BMPR-1A) in endocardium led to decreased phopho-SMAD1/5/8 activity and defective EMT in the endocardial cushion 48. Taken together, these studies demonstrate an important role for the TGF-β superfamily, including both TGF-β and BMP ligands, in promoting the endocardial EMT process critical for proper cardiac valve development.

Several Notch ligands and receptors Notch1-4 are expressed in the endocardium during endocardial cushion formation 24, 40, 49. Mouse embryos with complete loss of either Notch1 or RBPJk showed collapsed, hypocellular endocardial cushions, and the endocardial cells failed to show ultrastructural signs of EMT 49. This loss of EMT was associated with diminished Snail expression and failure to inhibit VE-cadherin expression. Conversely, over-expression of the Notch1 intracellular domain in endothelial cells resulted in Snail induction, loss of VE-cadherin expression, and morphological changes consistent with EMT 49.

Communication between cardiomyocyte and endothelial cells regulates cardiac conduction system development

The inductive signaling from endothelial cells plays an essential role in cardiac conduction system development. The cardiac conduction system (CCS) controls the generation and propagation of electric activity through the heart. Cardiac conduction is initiated by the sinoatrial node (SAN or pacemaker). After a delay mediated by the atrioventricular node (AVN), the electric activity is rapidly transmitted to the ventricular apex through the His-Purkinje system (review elsewhere 50). There has been a longstanding debate as to the origin of conductive cells, particularly Purkinje fibers. This debate is due, in part, to observations that the conductive cells express certain neuronal makers as well as genes expressed by cardiomyocytes 51–54. By using replication-defective retroviral infection, Mikawa and colleagues carried out the pioneering clonal analysis experiments in the avian embryos which showed that conduction cells predominantly differentiate from a subset of contractile cardiomyocytes 51. The theory of the myogenic origin of the conduction system is further supported by the findings that embryonic myocytes have the potential to convert their phenotype into Purkinje fiber conduction cells in response to paracrine signals. Gourdue and colleagues infected chick embryonic cardiomyocytes with endothelin-1 (ET-1), a cytokine produced by the endothelial cells of coronary arteries and endocardium. ET-1 expressing cardiomyocytes up-regulated expression of several Purkinje fiber-specific genes 55. Hyer and colleagues also showed that global or localized manipulation of the coronary branching patterns led to abnormal organization and induction of the peripheral conduction network 56. Consistent with this idea, embryonic cardiomyocytes converted in vitro to impulse-conducting Purkinje cells after exposure to endothelin-converting enzyme, a metalloprotease essential for converting the endothelin precursor polypeptide into an active peptide 57.

Additional signaling pathways have been implicated in regulation of Purkinje fiber development. Bond and colleagues revealed that the treatment of cardiomyocytes with ET-1 led to increased expression of Wnt11 and Wnt7a, suggesting Wnt signaling might be involved in inducing Purkinje fiber-specific genes 58. Recently, NRG-1 has been shown to induce differentiation of cardiomyocytes to components of the cardiac conduction system. The addition of exogenous NRG-1 in whole mouse embryo culture caused expansion of conduction system marker expression and changes in the ventricular electrical activation pattern 59. In zebrafish, Notch1b and NRG are required for specification of central cardiac conduction tissue 60. Thus, differentiation of Purkinje fibers may be spatiotemporally regulated both by inductive signals from endothelial cells.

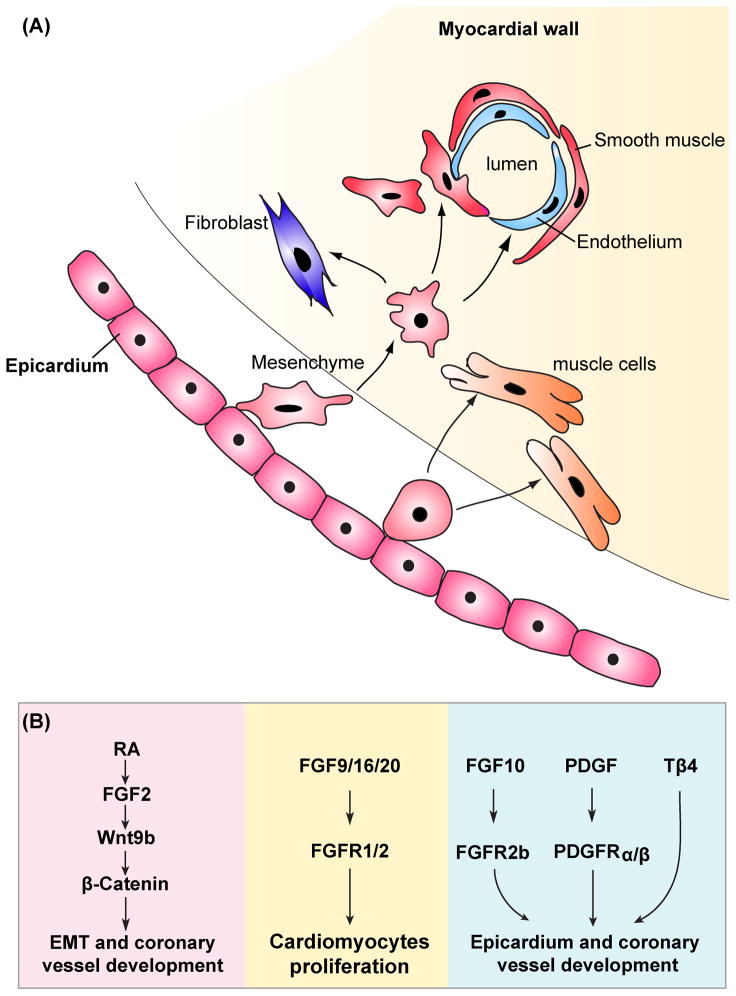

Dynamic interactions between myocardium and epicardium

Epicardium influences myocardial development

Soon after the heart tube forms, the epicardium begins to ensheath the heart to form the outmost epithelial layer. The epicardium is derived from the proepicardium which resides posterior and dorsal to the forming heart tube (reviewed elsewhere 61). As a result of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, the epicardial-derived cells (EPDCs) are currently thought to be a major source of cardiac fibroblasts, undifferentiated subepicardial mesenchymal, coronary endothelium and coronary VSMCs 62. The importance of the epicardium in modulating myocardial development was demonstrated by elimination of the PE. The major consequence of the absence of PE was a thin myocardial compact layer within the ventricular wall that resulted in poor cardiac function and embryonic lethality 63, 64. This suggests that epicardium acts as a source of secreted paracrine signals for proper myocardial development.

Several important paracrine signaling pathways have been shown to be involved in myocardial development, including FGF, Shh, RA and Wnt. In embryonic chick heart, Pennisi and colleagues used microsurgical inhibition of epicardial formation to examine cardiomyocyte proliferation 64. Epicardium-deficient hearts displayed a reduction in the thickness of the ventricular compact zone. Expression of FGF-2 and FGFR-1 were reduced in the myocardium in these experiments suggesting that FGF-2 signaling from the epicardium was necessary for proliferation of myocytes in the compact myocardial wall 64. However, complete loss of FGF-2 in the mouse heart resulted in no cardiac abnormalies, indicating redundant roles for FGFs in ventricular myocardial compaction 65, 66. Lavine and colleagues showed that FGF-9, -16, and -20 were expressed in the epicardium and these ligands signaled through FGFR-1 and FGFR-2 31. Mice with complete loss of FGF-9 or a myocardial-specific deletion of FGFR-1/FGFR-2 displayed decreased myocardial proliferation, indicating that interruption of FGF signaling between epicardium and myocardium reduced myocardial proliferation and led to defective differentiation of cardiac myocytes 31. Recently, Lavine and colleagues revealed a role for epicardial FGF signaling for development of the coronary vasculature as well. These studies showed that epicardial FGF signals induced myocardial activation of Hedgehog signaling, that in turn up-regulated VEGF-A, -B, -C, and Ang-2 expression, resulting in the formation of coronary vasculature 67.

Retinoic acid (RA) signals are transduced by 2 families of nuclear hormone receptors, the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs). Conditional deletion of RXRα in epicardial-derived cells using Gata5-Cre mediated exercision has an abnormal phenotype in cardiac development including a detached epicardium and a thin subepicardial mesenchymal layer, which is likely due to decreased FGF-2 production by the epicardium 68. The coronary arteries are also abnormal in Gata5-cre:RXRα mutants, with reduced vascular branching suggesting a defect in coronary arteriogenesis. Notably, persistent expression of atrial myosin heavy chain 2, which is normally down-regulated in ventricular myocytes during cardiac development, was observed in the ventricular myocardium of these mutants. This study indicates that the epicardium not only supports myocardial proliferation, but also plays an instructive role in myocardial differentiation. Moreover, there is evidence that epicardial RA signaling may act upstream of FGF and Wnt expression 68. RXRα-null epicardial cells express lower levels of both FGF-2, Wnt9b, and β-catenin 68. In addition, these studies showed that FGF-2 could activate epicardial Wnt signaling through the induction of Wnt9b in the epicardium. Taken together, these data suggest a model in which epicardial retinoic acid signaling activates FGF-2 expression directly in the epicardium or indirectly in the myocardium, resulting in the induction of epicardial Wnt9b expression and increased β-catenin activation. Activated β-catenin in epicardial cells then promotes the process of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and coronary vasculature development 68. However, one issue with these studies is that the Gata5-Cre-drived deletion of RXRα is not restricted to the epicardium. Gata5-Cre is active not only in epicardium, but also in diaphragm, pericardium, and cardiac cushions 68. Thus, further studies using an epicardium-restricted Cre mouse line such as WT-1/cre is needed to clarify whether the above findings are caused by loss of RXRα specifically in the epicardium.

Signaling from the myocardium regulates epicardial development and function

The key features of epicardial development are the directional protrusion of the proepicardium to the heart tube, epicardial cells migrating to cover the heart, and epicardial cell entry into the myocardium by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition 69–74. Epicardial cells mainly give rise to nonmyocyte lineages, including endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and cardiac fibroblasts that are essential to coronary vessel formation and matrix organization 69, 75–80. Recent studies from Ishii and colleagues have noted that myocardial-derived BMP signals regulate the entry of PE cells to the specific site of the heart by directing their morphogenic movement 70. The embryonic chick hearts were transfected with GFP tagged Noggin, a well-established BMP antagonist, to inhibit BMP signaling. Examination of GFP expression in myocardium indicated that mis-expression of Noggin disrupted proepicardium attachment to the heart. Conversely, over-expression of BMP2 or BMP4 ligands in the embryonic myocardium resulted in attachment of proepicardial cells to aberrant sites of the heart 70.

Signals emanating from the myocardium can also regulate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and subsequent differentiation. The Wnt and FGF signaling pathways have been demonstrated to play a critical role in epicardial development 81–83. Multiple Wnt ligands have been shown expressed in the developing myocardium 84. The primary effector of canonical Wnt signaling is the protein β-catenin which is stabilized and translocated to the nucleus upon active Wnt signaling where it binds LEF/TCF transcription factors to activate gene expression. Inactivation of β-catenin in epicardium using Gata5-Cre results in embryonic death due to reduced myocardial proliferation and a thinned myocardium 85. Reduced expansion of the subepicardial mesenchyme was noted by reduced vimentin expression, suggesting defects in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Although Gata5-cre:β-catenin mutants displayed a primitive capillary plexus in the subepicardial space and the coronary venous system, the coronary arterial vessels did not form. However, it is also possible that β-catenin functions in the epicardium to maintain important cell–cell interactions. Using an in vitro explant culture system, Von Gise and colleagues showed that treatment of epicardial-derived cells (EPDCs) with inhibitors of canonical Wnt signaling such as Dkk1 or Sfrp2, led to diminished epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition 86. This study suggests that Wnt signaling is involved in a cell intrinsic manner in the epicardium to promote proper coronary vessel development. Additional support for an important role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the epicardium comes from studies using Wilm’s tumor-1 (WT1) mutant mice which have defective epicardial development 86. WT1-null mutants showed broad defects in Wnt signaling, including reduced expression of epicardial β-catenin, downstream transcriptional targets of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling including axin2, cyclinD1 and cyclinD2 as well as Wnt5a, a non-canonical Wnt ligand 86. Together these studies point to a crucial role for Wnt signaling in regulation of epicardial development.

Among the FGF ligands expressed in the developing mouse heart, FGF10 has been identified in the myocardium 87, 88. Global inactivation of FGF-10 led to myocardial hypoplasia as well as the defects in cardiac fibroblast formation 87. Mice lacking FGFR-2 in the epicardium exhibited a similar phenotype as that of FGF-10 null mutants 87. This suggests that FGF-10 signals through FGFR-2b in the epicardium to control its development and function.

The PDGF signaling and Thymosin β4 signaling also regulates myocardial-epicardial signaling. Both PDGF receptors, α and β, are expressed in the epicardium in early embryonic development 89, 90. Epicardial deletion of both PDGF receptors lead to failure of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and EPDC formation. Notably, loss of PDGFRα resulted in a deficient in cardiac fibroblast formation, but normal coronary VSMC development 89. Conversely, inactivation of PDGFRβ caused defects in coronary VSMC development, whereas cardiac fibroblasts were unperturbed 90. These studies indicated that PDGF signals from the adjacent myocardium are required for the proper epicardium development and function. Thymosin β4 is a 43-amino-acid G-actin-sequestering peptide implicated in reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Thymosin β4 is expressed throughout the developing myocardium, but is not expressed in the epicardium 91. Cardiac-specifc knockdown of Thymosin β4 mouse embryos using Nkx2.5-Cre revealed that EPDCs were retained in the epicardium and failed to give rise to coronary vessels 91. This study indicated that Thymosin β4 is critical for epicardial development and coronary artery formation.

Interactions between cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes

The cardiac fibroblast is the largest nonmyocyte cell population in the adult heart. Cross talk between cardiac fibroblasts and cardiac myocytes is important for both cardiac development and the ability of cardiac repair in response to injury. In the developing heart, cardiac fibroblast synthesizes ECM and growth factors, which regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation in a paracrine manner. Using co-culture of cardiac fibroblasts (Thy1+, DDR2+, CD31-) with cardiomyocytes (Nkx2.5-YFP) from embryonic mouse hearts, Ieda and colleagues showed the embryonic cardiac fibroblast promoted cardiomyocyte proliferation 92. Knockdown of fibronectin and collagen expression in embryonic cardiac fibroblast by siRNA resulted in decreased cardiomyocyte proliferation. They showed that the β1 integrin, the receptor for fibronectin and collagen, was expressed in cardiomyocytes coincidentally with the appearance of cardiac fibroblasts. An antibody against the β1 integrin inhibited cardiomyocyte proliferation when co-culturing cardiomyocytes with embryonic cardiac fibroblasts. Moreover, β1 integrin mutant mice exhibited a reduction in myocardial proliferation and abnormal muscle integrity. These findings suggest that embryonic cardiac fibroblasts regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation through ECM/β1 integrin signaling during development. However, in the adult heart, the role of cardiac fibroblasts on cardiomyocyte proliferation is still unclear. Studies from Kuhn and colleagues indicated that administration of periostin, a matricellular protein synthesized by cardiac fibroblast, could induce differentiated cardiomyocyte to reenter the cell cycle and undergo cell division in vivo 93. However, the loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies of periostin from Lorts and colleagues demonstrated that periostin did not affect cardiomyocyte proliferation or cell cycle entry. 94.

Cardiomyocyte-noncardiomycyte communication in cardiovascular diseases

Signaling crosstalk between cardiomyocytes and noncardiomyoctes, including endothelial cells and cardiac fibroblasts, is crucial in the development of cardiac hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, ventricular remodeling and heart failure. The vascular endothelium controls vascular tone by balancing local levels of vasoconstrictors and vasodilators. Under physiological conditions, vascular endothelial cells continuously release nitric oxide (NO), which relaxes surrounding smooth muscle cells and ensures vessel patency 95. However, in response to injury, such as sustained pressure overload, activation of endothelial cells may lead to diminished NO signaling, while increasing levels of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS)-derived reactive oxygen species 96. NO is known to influence myocardial excitation-contraction coupling, substrate metabolism, and hypertrophy, as well as cell survival, which are in part dependent on eNOS and nNOS expression in cardiomyocytes 97. Mice homozygous null for eNOS develop concentric left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis 98, indicating the importance of the autocrine and paracrine effects of NO in cardiac remodeling 99.

Accumulating evidences support the notion that an increase in angiogenesis not only may support cardiomyocyte hypertrophy but also may actually induce this process. Using an inducible mouse transgenic model, Tirziu and colleagues showed that mice with α-MHC-targeted over-expression of an angiogenic peptide (PR39) exhibit myocardial hypertrophy in the absence of any external stimuli 100. Heart enlargement in PR39 transgenic adult mice was due to an increase in cardiomyocyte size, and it was prevented by concurrent treatment with an endothelial NOS inhibitor. However, the mechanism by which NO induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is not clear 101. One possibility is that NO may control Gα q-protein-induced hypertrophic signaling. Low levels of NO would favor this hypertrophic program, whereas high NO levels, as a result of an increase in endothelial cell mass, would inhibit this hypertrophic program 100, 102–104. Moreover, the link between angiogenesis and myocardial hypertrophy was addressed in another study in which inhibition of VEGF action using an adenoviral vector encoding a decoy VEGF receptor or an anti-VEGF antibody, accelerated the progression from compensatory hypertrophy to cardiac failure in response to pressure overload in mice 105. Conversely, VEGF treatment during prolonged pressure overload preserved contractile function 105, 106.

The importance of myocardial regulation of coronary vascular function has been indicated by the role of PDGF signaling and Thymosin β4 signaling during the process of adult heart repair after injury. A neutralizing PDGF-A-specific antibody attenuated induction of pressure overload-induced atrial fibrosis and fibrillation in mice 107. However several inhibitors of receptor tyrosine kinases, including PDGFRs, have been linked to the development of cardiomyopathy in some treated patients 108–111. PDGFR in cardiomyocytes is indispensable for the cardiac response to pressure overload and may regulate angiogenesis 112. For therapeutic targeting PDGF signaling in cardiac remodeling, it will be important to further clarify the precise roles played by the PDGF pathway under various pathological and physiological conditions. Thymosin β4 can stimulate migration of cardiomyocytes in vitro and promotes survival of cardiomyocytes and cardiac function in adult mice 113. The role of Thymosin β4 signaling in coronary vessel development has been assessed for its potential as a therapeutic target in terms of cardioprotection and repair. Ectopic administration of Thymosin β4 in a mouse model of myocardial infarction promoted an angiogenic response 114, 115.

Recent studies have shown that cardiac fibroblasts regulate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in the adult heart 116, 117. Angiotensin II (Ang II), a potent hypertropic stimulant, induces TGF-β expression by cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts 118. TGF-β, in turn, promotes cardiac hypertrophy by activation of Smad proteins and TGF-β-activated kinase-1. Complete loss of TGF-β in mice showed no significant cardiac hypertrophy or fibrosis when subjected to chronic doses of AngII 119. Likewise, an ALK5 (TGF-βR1) inhibitor inhibited cardiac fibroblast activation and systolic dysfunction in the rat model of myocardial infarction 120. Moreover, Insulin Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling is also association with adaptive and cardioprotective response. IGF-1 is primarily expressed in cardiac fibroblasts where it activates downstream signal transducers including PI3K, leading to cardiac hypertrophy 121. Tekade and colleagues showed that Klf5 regulated IGF-1 expression in cardiac fibroblasts in response to stress 116. Cardiac fibroblast-specific deletion of Klf5 reduced the cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis initiated by moderate-intensity pressure overload 116. Recently, Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF, also known as CCN2), a TGF-β-activated factor, has been shown to regulate cardiac fibroblast proliferation and ECM deposition during the progression of myocardial fibrosis 122. In mice, CTGF is expressed in cardomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts. Transgenic mice with α-MHC-targeted over-expression of CTGF displayed significantly increased fibrosis and contractile dysfunction in response to pressure overload 123. Duisters and colleagues showed that CTGF expression is negatively regulated by cardiac microRNA-133 (miR-133) and miR-30 124. miR-133 is expressed specifically in cardiomyocytes and inhibition of miR-133 expression in vivo by an antagomir causes cardiac hypertrophy 125. However, complete loss of miR-133a-1 and miR-133a-2 showed no evidence of cardiac hypertrophy, but instead, resulted in dilated cardiomyopathy and cardiac fibrosis 126. Despite such discrepant results, enhancing the endogenous regenerative capacity of the heart via extracellular factors is a potential approach to therapeutic cardiac regeneration.

Another important regulatory mechanism of cardiac repair is the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. A number of studies have shown that several Wnt ligands, along with intracellular mediators of canonical Wnt signaling including Disheveled and β-catenin, are induced after experimental myocardial infarction (MI) 1, 127–132. However there is conflicting evidence about the role of Wnt pathway in cardiac repair after MI. For example, over-expression of secreted frizzled-related protein 2 (Sfrp2), a Wnt antagonist, caused up-regulated expression of anti-apoptotic genes in cardiac myocytes 133, 134. Exogenous administration of Sfrp2 by injection into the injured heart led to reduced infarct size and decreased cardiac fibrosis 135. However, mice with complete loss of Sfrp2 also exhibited decreased fibrosis and better recovery after myocardial injury 131. Consistent with the last finding, Hahn and colleagues showed that adenovirus-mediated transfer of constitutively active β-catenin, the primary canonical Wnt pathway activator, caused a reduction in myocardial infarct size in a rat MI model, suggesting that canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays an anti-fibrotic role during cardiac repair 136. These discrepant results might be due to the use of different models and techniques to promote or inhibit Wnt signaling. Most recently, two studies have demonstrated that the activation of canonical Wnt/β-catenin is essential for cardiac tissue repair after MI 1, 132. Using the TOPGAL reporter transgenic mouse line, which carries the lacZ gene under the control of β-catenin-responsive consensus TCF/LEF-binding motif, Aisagbonhi and colleagues showed increased activity of canonical Wnt/β-catenin in subepicardial endothelial cells and perivascular smooth muscle actin positive (SMA+) cells 4 days after MI 132. Moreover, Duan and colleagues showed the dynamic injury response of Wnt1/β-catenin activated the epicardium and cardiac fibroblasts to promote cardiac repair 1. Inactivation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cardiac fibroblasts using Cola2CreERT-mediated excision of β-catenin resulted in poor cardiac repair and cardiac dysfunction 1. These findings reveal that temporal and cell type specific manipulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling could offer a new target for development of therapeutic strategies to improve cardiac repair after acute ischaemic injury.

Recently, Ieda and colleagues demonstrated that three cardiac restricted transcription factors, Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 can reprogram neonatal cardiac fibroblasts into cells that resemble cardiomyocytes 137. These studies also showed that the reprogramming of neonatal cardiac fibroblasts to differentiated cardiomyocytes was more efficient than reprogramming of tail-tip fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes by Gata4/Mef2c/Tbx5. One explanation is that cardiac fibroblasts express a transcriptome more similar to cardiomyocytes compared to tail-tip fibroblasts. Future studies using additional factors including microRNAs, signaling proteins, or small molecules may lead to increased efficiency of this reprogramming process and allow for in vivo cardiomyocyte reprogramming in the setting of cardiac injury or disease.

Summary

While our knowledge of the development and response to injury for cardiomyocytes has grown dramatically in recent years, less is known about the role of nonmyocyte populations in the heart. The endocardium and epicardium clearly play critical roles as not only direct contributors to specific tissues within the heart including cardiac valves but also as important signaling centers that help regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation. Less understood nonmyocyte lineages including the cardiac fibroblast are likely to become more relevant to our understanding of how cardiomyocytes develop and respond to injury as ongoing studies reveal more about their developmental origins and function. Studies implicating that direct conversion between cardiac fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes through expression of certain transcription factors open intriguing possibilities to promote cardiac regeneration by promoting this process in vivo. Thus, nonmyocytes may ultimately be an important target for maintaining cardiac homeostasis as well as promoting cardiomyocyte regeneration in the setting of injury or disease.

Figure 1. Model of reciprocal signaling between endocardial cells and myocytes during cardiac development, growth, and maturation.

(A) Depiction of this reciprocal signaling during myocardial trabeculation. (B) The left side depicts myocardial-endocardial signaling while the right side depicts endocardial-myocardial signaling. (C) Depiction of this signaling during endocardial cushion formation. (D) Major signaling pathways regulating endocardial-mesenchymal transformation (EMT).

Figure 2. Model of interactions between epicardium and myocardium in cardiac development.

(A) A schematic depiction of epicardium-myocardium communication. Epicardial progenitors undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, invade the myocardium, and differentiate into various mature cardiac cell types, including vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts and cardiac myocytes.(B) Important signaling pathways regulating this process are shown. The left side (pink) depicts the signaling within epicardium, the middle side (yellow) depicts how epicardium influences myocardial proliferation, while the right side (blue) depicts myocardium regulating epicardial development and function.

Acknowledgments

We apologize in advance to investigators whose research was not cited in this review due to space limitations. Work in the Morrisey Lab is supported by funding from the NIH and the American Heart Association Jon Holden DeHaan Myogenesis Center grant.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- EMT

Endocardial - mesenchymal transformation

- NRG

neuregulin

- Ang-1

angiopoietin-1

- AVC

atrioventricular canal

- OFT

outflow tract

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

- BMPR-1A

BMP receptor-1A

- CCS

cardiac conduction system

- SAN

sinoatrial node

- AVN

atrioventricular node

- ET-1

endothelin-1

- EPDC

epicardial-derived cell

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- RXR

retinoid X receptor

- PE

proepicardium

- NO

nitric oxide

- eNOS

endothelial NO synthase

- Ang II

Angiotensin II

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- Sfrp2

secreted frizzled-related protein 2

- SMA

smooth muscle actin

- E

embryonic day

- WT1

Wilm’s tumor-1

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- CTGF

connective tissue growth factor

- MI

myocardial infarction

Footnotes

COMPETING FINNACIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Duan J, Gherghe C, Liu D, Hamlett E, Srikantha L, Rodgers L, Regan JN, Rojas M, Willis M, Leask A, Majesky M, Deb A. Wnt1/betacatenin injury response activates the epicardium and cardiac fibroblasts to promote cardiac repair. Embo J. 2011;31:429–442. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishii Y, Langberg J, Rosborough K, Mikawa T. Endothelial cell lineages of the heart. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335:67–73. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0663-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris IS, Black BL. Development of the endocardium. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31:391–399. doi: 10.1007/s00246-010-9642-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bu L, Jiang X, Martin-Puig S, Caron L, Zhu S, Shao Y, Roberts DJ, Huang PL, Domian IJ, Chien KR. Human isl1 heart progenitors generate diverse multipotent cardiovascular cell lineages. Nature. 2009;460:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature08191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kattman SJ, Huber TL, Keller GM. Multipotent flk-1+ cardiovascular progenitor cells give rise to the cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Dev Cell. 2006;11:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motoike T, Markham DW, Rossant J, Sato TN. Evidence for novel fate of flk1+ progenitor: Contribution to muscle lineage. Genesis. 2003;35:153–159. doi: 10.1002/gene.10175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masino AM, Gallardo TD, Wilcox CA, Olson EN, Williams RS, Garry DJ. Transcriptional regulation of cardiac progenitor cell populations. Circ Res. 2004;95:389–397. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138302.02691.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen-Gould L, Mikawa T. The fate diversity of mesodermal cells within the heart field during chicken early embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 1996;177:265–273. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei Y, Mikawa T. Fate diversity of primitive streak cells during heart field formation in ovo. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:505–513. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1076>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brutsaert DL, De Keulenaer GW, Fransen P, Mohan P, Kaluza GL, Andries LJ, Rouleau JL, Sys SU. The cardiac endothelium: Functional morphology, development, and physiology. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1996;39:239–262. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(96)80004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stainier DY, Weinstein BM, Detrich HW, 3rd, Zon LI, Fishman MC. Cloche, an early acting zebrafish gene, is required by both the endothelial and hematopoietic lineages. Development. 1995;121:3141–3150. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao W, Bisgrove BW, Sawyer H, Hug B, Bell B, Peters K, Grunwald DJ, Stainier DY. The zebrafish gene cloche acts upstream of a flk-1 homologue to regulate endothelial cell differentiation. Development. 1997;124:381–389. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falls DL. Neuregulins: Functions, forms, and signaling strategies. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:14–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lemmens K, Doggen K, De Keulenaer GW. Role of neuregulin-1/erbb signaling in cardiovascular physiology and disease: Implications for therapy of heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:954–960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gassmann M, Casagranda F, Orioli D, Simon H, Lai C, Klein R, Lemke G. Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the erbb4 neuregulin receptor. Nature. 1995;378:390–394. doi: 10.1038/378390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KF, Simon H, Chen H, Bates B, Hung MC, Hauser C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbb2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature. 1995;378:394–398. doi: 10.1038/378394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer D, Birchmeier C. Multiple essential functions of neuregulin in development. Nature. 1995;378:386–390. doi: 10.1038/378386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai D, Liu X, Forrai A, Wolstein O, Michalicek J, Ahmed I, Garratt AN, Birchmeier C, Zhou M, Hartley L, Robb L, Feneley MP, Fatkin D, Harvey RP. Neuregulin 1 sustains the gene regulatory network in both trabecular and nontrabecular myocardium. Circ Res. 2010;107:715–727. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hertig CM, Kubalak SW, Wang Y, Chien KR. Synergistic roles of neuregulin-1 and insulin-like growth factor-i in activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway and cardiac chamber morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37362–37369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao YY, Sawyer DR, Baliga RR, Opel DJ, Han X, Marchionni MA, Kelly RA. Neuregulins promote survival and growth of cardiac myocytes. Persistence of erbb2 and erbb4 expression in neonatal and adult ventricular myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10261–10269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bondy CA, Werner H, Roberts CT, Jr, LeRoith D. Cellular pattern of insulin-like growth factor-i (igf-i) and type i igf receptor gene expression in early organogenesis: Comparison with igf-ii gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 1990;4:1386–1398. doi: 10.1210/mend-4-9-1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brutsaert DL. Cardiac endothelial-myocardial signaling: Its role in cardiac growth, contractile performance, and rhythmicity. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:59–115. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bersell K, Arab S, Haring B, Kuhn B. Neuregulin1/erbb4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell. 2009;138:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grego-Bessa J, Luna-Zurita L, del Monte G, Bolos V, Melgar P, Arandilla A, Garratt AN, Zang H, Mukouyama YS, Chen H, Shou W, Ballestar E, Esteller M, Rojas A, Perez-Pomares JM, de la Pompa JL. Notch signaling is essential for ventricular chamber development. Dev Cell. 2007;12:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi TP, Gertsenstein M, Wu XF, Breitman ML, Schuh AC. Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in flk-1-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;376:62–66. doi: 10.1038/376062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puri MC, Partanen J, Rossant J, Bernstein A. Interaction of the tek and tie receptor tyrosine kinases during cardiovascular development. Development. 1999;126:4569–4580. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato TN, Tozawa Y, Deutsch U, Wolburg-Buchholz K, Fujiwara Y, Gendron-Maguire M, Gridley T, Wolburg H, Risau W, Qin Y. Distinct roles of the receptor tyrosine kinases tie-1 and tie-2 in blood vessel formation. Nature. 1995;376:70–74. doi: 10.1038/376070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suri C, Jones PF, Patan S, Bartunkova S, Maisonpierre PC, Davis S, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD. Requisite role of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the tie2 receptor, during embryonic angiogenesis. Cell. 1996;87:1171–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81813-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward NL, Van Slyke P, Sturk C, Cruz M, Dumont DJ. Angiopoietin 1 expression levels in the myocardium direct coronary vessel development. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:500–509. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagen AS, Orbus RJ, Wilkening RB, Regnault TR, Anthony RV. Placental expression of angiopoietin-1, angiopoietin-2 and tie-2 during placental development in an ovine model of placental insufficiency-fetal growth restriction. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:1228–1232. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000185266.23265.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavine KJ, Yu K, White AC, Zhang X, Smith C, Partanen J, Ornitz DM. Endocardial and epicardial derived fgf signals regulate myocardial proliferation and differentiation in vivo. Dev Cell. 2005;8:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugi Y, Ito N, Szebenyi G, Myers K, Fallon JF, Mikawa T, Markwald RR. Fibroblast growth factor (fgf)-4 can induce proliferation of cardiac cushion mesenchymal cells during early valve leaflet formation. Dev Biol. 2003;258:252–263. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Li S, Yuan L, Tian Y, Weidenfeld J, Yang J, Liu F, Chokas AL, Morrisey EE. Foxp1 coordinates cardiomyocyte proliferation through both cell-autonomous and nonautonomous mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1746–1757. doi: 10.1101/gad.1929210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamers WH, Viragh S, Wessels A, Moorman AF, Anderson RH. Formation of the tricuspid valve in the human heart. Circulation. 1995;91:111–121. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potts JD, Dagle JM, Walder JA, Weeks DL, Runyan RB. Epithelial-mesenchymal transformation of embryonic cardiac endothelial cells is inhibited by a modified antisense oligodeoxynucleotide to transforming growth factor beta 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1516–1520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potts JD, Runyan RB. Epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart can be mediated, in part, by transforming growth factor beta. Dev Biol. 1989;134:392–401. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boyer AS, Ayerinskas, Vincent EB, McKinney LA, Weeks DL, Runyan RB. Tgfbeta2 and tgfbeta3 have separate and sequential activities during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart. Dev Biol. 1999;208:530–545. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartram U, Molin DG, Wisse LJ, Mohamad A, Sanford LP, Doetschman T, Speer CP, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Double-outlet right ventricle and overriding tricuspid valve reflect disturbances of looping, myocardialization, endocardial cushion differentiation, and apoptosis in tgf-beta(2)-knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;103:2745–2752. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.22.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanford LP, Ormsby I, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Sariola H, Friedman R, Boivin GP, Cardell EL, Doetschman T. Tgfbeta2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non-overlapping with other tgfbeta knockout phenotypes. Development. 1997;124:2659–2670. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liebner S, Cattelino A, Gallini R, Rudini N, Iurlaro M, Piccolo S, Dejana E. Beta-catenin is required for endothelial-mesenchymal transformation during heart cushion development in the mouse. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:359–367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakajima Y, Yamagishi T, Nakamura H, Markwald RR, Krug EL. An autocrine function for transforming growth factor beta 3 in the atrioventricular endocardial cushion tissue formation during chick heart development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;857:272–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hurlstone AF, Haramis AP, Wienholds E, Begthel H, Korving J, Van Eeden F, Cuppen E, Zivkovic D, Plasterk RH, Clevers H. The wnt/beta-catenin pathway regulates cardiac valve formation. Nature. 2003;425:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature02028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakajima Y, Yamagishi T, Hokari S, Nakamura H. Mechanisms involved in valvuloseptal endocardial cushion formation in early cardiogenesis: Roles of transforming growth factor (tgf)-beta and bone morphogenetic protein (bmp) Anat Rec. 2000;258:119–127. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(20000201)258:2<119::AID-AR1>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sugi Y, Yamamura H, Okagawa H, Markwald RR. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 can mediate myocardial regulation of atrioventricular cushion mesenchymal cell formation in mice. Dev Biol. 2004;269:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamagishi T, Nakajima Y, Miyazono K, Nakamura H. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 acts synergistically with transforming growth factor-beta3 during endothelial-mesenchymal transformation in the developing chick heart. J Cell Physiol. 1999;180:35–45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199907)180:1<35::AID-JCP4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones CM, Lyons KM, Hogan BL. Involvement of bone morphogenetic protein-4 (bmp-4) and vgr-1 in morphogenesis and neurogenesis in the mouse. Development. 1991;111:531–542. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.2.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lyons KM, Pelton RW, Hogan BL. Organogenesis and pattern formation in the mouse: Rna distribution patterns suggest a role for bone morphogenetic protein-2a (bmp-2a) Development. 1990;109:833–844. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma L, Lu MF, Schwartz RJ, Martin JF. Bmp2 is essential for cardiac cushion epithelial-mesenchymal transition and myocardial patterning. Development. 2005;132:5601–5611. doi: 10.1242/dev.02156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Timmerman LA, Grego-Bessa J, Raya A, Bertran E, Perez-Pomares JM, Diez J, Aranda S, Palomo S, McCormick F, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, de la Pompa JL. Notch promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mikawa T, Hurtado R. Development of the cardiac conduction system. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fischman DA, Mikawa T. The use of replication-defective retroviruses for cell lineage studies of myogenic cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1997;52:215–227. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gorza L, Schiaffino S, Vitadello M. Heart conduction system: A neural crest derivative? Brain Res. 1988;457:360–366. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90707-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gorza L, Vitadello M. Distribution of conduction system fibers in the developing and adult rabbit heart revealed by an antineurofilament antibody. Circ Res. 1989;65:360–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vitadello M, Matteoli M, Gorza L. Neurofilament proteins are co-expressed with desmin in heart conduction system myocytes. J Cell Sci. 1990;97 ( Pt 1):11–21. doi: 10.1242/jcs.97.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gourdie RG, Wei Y, Kim D, Klatt SC, Mikawa T. Endothelin-induced conversion of embryonic heart muscle cells into impulse-conducting purkinje fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6815–6818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hyer J, Johansen M, Prasad A, Wessels A, Kirby ML, Gourdie RG, Mikawa T. Induction of purkinje fiber differentiation by coronary arterialization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13214–13218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takebayashi-Suzuki K, Yanagisawa M, Gourdie RG, Kanzawa N, Mikawa T. In vivo induction of cardiac purkinje fiber differentiation by coexpression of preproendothelin-1 and endothelin converting enzyme-1. Development. 2000;127:3523–3532. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.16.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bond J, Sedmera D, Jourdan J, Zhang Y, Eisenberg CA, Eisenberg LM, Gourdie RG. Wnt11 and wnt7a are up-regulated in association with differentiation of cardiac conduction cells in vitro and in vivo. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:536–543. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rentschler S, Zander J, Meyers K, France D, Levine R, Porter G, Rivkees SA, Morley GE, Fishman GI. Neuregulin-1 promotes formation of the murine cardiac conduction system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10464–10469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162301699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Milan DJ, Giokas AC, Serluca FC, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Notch1b and neuregulin are required for specification of central cardiac conduction tissue. Development. 2006;133:1125–1132. doi: 10.1242/dev.02279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wessels A, Perez-Pomares JM. The epicardium and epicardially derived cells (epdcs) as cardiac stem cells. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;276:43–57. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snider P, Standley KN, Wang J, Azhar M, Doetschman T, Conway SJ. Origin of cardiac fibroblasts and the role of periostin. Circ Res. 2009;105:934–947. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manner J, Schlueter J, Brand T. Experimental analyses of the function of the proepicardium using a new microsurgical procedure to induce loss-of-proepicardial-function in chick embryos. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:1454–1463. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pennisi DJ, Ballard VL, Mikawa T. Epicardium is required for the full rate of myocyte proliferation and levels of expression of myocyte mitogenic factors fgf2 and its receptor, fgfr-1, but not for transmural myocardial patterning in the embryonic chick heart. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:161–172. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schultz JE, Witt SA, Nieman ML, Reiser PJ, Engle SJ, Zhou M, Pawlowski SA, Lorenz JN, Kimball TR, Doetschman T. Fibroblast growth factor-2 mediates pressure-induced hypertrophic response. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:709–719. doi: 10.1172/JCI7315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou M, Sutliff RL, Paul RJ, Lorenz JN, Hoying JB, Haudenschild CC, Yin M, Coffin JD, Kong L, Kranias EG, Luo W, Boivin GP, Duffy JJ, Pawlowski SA, Doetschman T. Fibroblast growth factor 2 control of vascular tone. Nat Med. 1998;4:201–207. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lavine KJ, White AC, Park C, Smith CS, Choi K, Long F, Hui CC, Ornitz DM. Fibroblast growth factor signals regulate a wave of hedgehog activation that is essential for coronary vascular development. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1651–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.1411406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Merki E, Zamora M, Raya A, Kawakami Y, Wang J, Zhang X, Burch J, Kubalak SW, Kaliman P, Belmonte JC, Chien KR, Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardial retinoid x receptor alpha is required for myocardial growth and coronary artery formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18455–18460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504343102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dettman RW, Denetclaw W, Jr, Ordahl CP, Bristow J. Common epicardial origin of coronary vascular smooth muscle, perivascular fibroblasts, and intermyocardial fibroblasts in the avian heart. Dev Biol. 1998;193:169–181. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ishii Y, Garriock RJ, Navetta AM, Coughlin LE, Mikawa T. Bmp signals promote proepicardial protrusion necessary for recruitment of coronary vessel and epicardial progenitors to the heart. Dev Cell. 2010;19:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ratajska A, Czarnowska E, Ciszek B. Embryonic development of the proepicardium and coronary vessels. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:229–236. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072340ar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reese DE, Mikawa T, Bader DM. Development of the coronary vessel system. Circ Res. 2002;91:761–768. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000038961.53759.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Viragh S, Challice CE. The origin of the epicardium and the embryonic myocardial circulation in the mouse. Anat Rec. 1981;201:157–168. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092010117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Viragh S, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Poelmann RE, Kalman F. Early development of quail heart epicardium and associated vascular and glandular structures. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1993;188:381–393. doi: 10.1007/BF00185947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Vrancken Peeters MP, Mentink MM, Gourdie RG, Poelmann RE. Epicardium-derived cells contribute a novel population to the myocardial wall and the atrioventricular cushions. Circ Res. 1998;82:1043–1052. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manner J. Does the subepicardial mesenchyme contribute myocardioblasts to the myocardium of the chick embryo heart? A quail-chick chimera study tracing the fate of the epicardial primordium. Anat Rec. 1999;255:212–226. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0185(19990601)255:2<212::aid-ar11>3.3.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mikawa T, Cohen-Gould L, Fischman DA. Clonal analysis of cardiac morphogenesis in the chicken embryo using a replication-defective retrovirus. Iii: Polyclonal origin of adjacent ventricular myocytes. Dev Dyn. 1992;195:133–141. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001950208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mikawa T, Gourdie RG. Pericardial mesoderm generates a population of coronary smooth muscle cells migrating into the heart along with ingrowth of the epicardial organ. Dev Biol. 1996;174:221–232. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Perez-Pomares JM, Carmona R, Gonzalez-Iriarte M, Atencia G, Wessels A, Munoz-Chapuli R. Origin of coronary endothelial cells from epicardial mesothelium in avian embryos. Int J Dev Biol. 2002;46:1005–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhou B, Ma Q, Rajagopal S, Wu SM, Domian I, Rivera-Feliciano J, Jiang D, von Gise A, Ikeda S, Chien KR, Pu WT. Epicardial progenitors contribute to the cardiomyocyte lineage in the developing heart. Nature. 2008;454:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature07060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Garriock RJ, D’Agostino SL, Pilcher KC, Krieg PA. Wnt11-r, a protein closely related to mammalian wnt11, is required for heart morphogenesis in xenopus. Dev Biol. 2005;279:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hamblet NS, Lijam N, Ruiz-Lozano P, Wang J, Yang Y, Luo Z, Mei L, Chien KR, Sussman DJ, Wynshaw-Boris A. Dishevelled 2 is essential for cardiac outflow tract development, somite segmentation and neural tube closure. Development. 2002;129:5827–5838. doi: 10.1242/dev.00164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Park M, Wu X, Golden K, Axelrod JD, Bodmer R. The wingless signaling pathway is directly involved in drosophila heart development. Dev Biol. 1996;177:104–116. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cohen ED, Tian Y, Morrisey EE. Wnt signaling: An essential regulator of cardiovascular differentiation, morphogenesis and progenitor self-renewal. Development. 2008;135:789–798. doi: 10.1242/dev.016865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zamora M, Manner J, Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardium-derived progenitor cells require beta-catenin for coronary artery formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18109–18114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702415104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.von Gise A, Zhou B, Honor LB, Ma Q, Petryk A, Pu WT. Wt1 regulates epicardial epithelial to mesenchymal transition through beta-catenin and retinoic acid signaling pathways. Dev Biol. 2011;356:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.05.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vega-Hernandez M, Kovacs A, De Langhe S, Ornitz DM. Fgf10/fgfr2b signaling is essential for cardiac fibroblast development and growth of the myocardium. Development. 2011;138:3331–3340. doi: 10.1242/dev.064410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marguerie A, Bajolle F, Zaffran S, Brown NA, Dickson C, Buckingham ME, Kelly RG. Congenital heart defects in fgfr2-iiib and fgf10 mutant mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith CL, Baek ST, Sung CY, Tallquist MD. Epicardial-derived cell epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fate specification require pdgf receptor signaling. Circ Res. 2011;108:e15–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.235531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mellgren AM, Smith CL, Olsen GS, Eskiocak B, Zhou B, Kazi MN, Ruiz FR, Pu WT, Tallquist MD. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta signaling is required for efficient epicardial cell migration and development of two distinct coronary vascular smooth muscle cell populations. Circ Res. 2008;103:1393–1401. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Smart N, Risebro CA, Melville AA, Moses K, Schwartz RJ, Chien KR, Riley PR. Thymosin beta4 induces adult epicardial progenitor mobilization and neovascularization. Nature. 2007;445:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature05383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ieda M, Tsuchihashi T, Ivey KN, Ross RS, Hong TT, Shaw RM, Srivastava D. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kuhn B, del Monte F, Hajjar RJ, Chang YS, Lebeche D, Arab S, Keating MT. Periostin induces proliferation of differentiated cardiomyocytes and promotes cardiac repair. Nat Med. 2007;13:962–969. doi: 10.1038/nm1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lorts A, Schwanekamp JA, Elrod JW, Sargent MA, Molkentin JD. Genetic manipulation of periostin expression in the heart does not affect myocyte content, cell cycle activity, or cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2009;104:e1–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dinerman JL, Lowenstein CJ, Snyder SH. Molecular mechanisms of nitric oxide regulation. Potential relevance to cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 1993;73:217–222. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kai H, Mori T, Tokuda K, Takayama N, Tahara N, Takemiya K, Kudo H, Sugi Y, Fukui D, Yasukawa H, Kuwahara F, Imaizumi T. Pressure overload-induced transient oxidative stress mediates perivascular inflammation and cardiac fibrosis through angiotensin ii. Hypertens Res. 2006;29:711–718. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Seddon M, Shah AM, Casadei B. Cardiomyocytes as effectors of nitric oxide signalling. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ruetten H, Dimmeler S, Gehring D, Ihling C, Zeiher AM. Concentric left ventricular remodeling in endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice by chronic pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Takeda N, Manabe I. Cellular interplay between cardiomyocytes and nonmyocytes in cardiac remodeling. Int J Inflam. 2011;2011:535241. doi: 10.4061/2011/535241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tirziu D, Chorianopoulos E, Moodie KL, Palac RT, Zhuang ZW, Tjwa M, Roncal C, Eriksson U, Fu Q, Elfenbein A, Hall AE, Carmeliet P, Moons L, Simons M. Myocardial hypertrophy in the absence of external stimuli is induced by angiogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3188–3197. doi: 10.1172/JCI32024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tirziu D, Simons M. Endothelium-driven myocardial growth or nitric oxide at the crossroads. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tirziu D, Giordano FJ, Simons M. Cell communications in the heart. Circulation. 2010;122:928–937. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.847731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hu RG, Sheng J, Qi X, Xu Z, Takahashi TT, Varshavsky A. The n-end rule pathway as a nitric oxide sensor controlling the levels of multiple regulators. Nature. 2005;437:981–986. doi: 10.1038/nature04027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Izumiya Y, Shiojima I, Sato K, Sawyer DB, Colucci WS, Walsh K. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade promotes the transition from compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to failure in response to pressure overload. Hypertension. 2006;47:887–893. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215207.54689.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sano M, Minamino T, Toko H, Miyauchi H, Orimo M, Qin Y, Akazawa H, Tateno K, Kayama Y, Harada M, Shimizu I, Asahara T, Hamada H, Tomita S, Molkentin JD, Zou Y, Komuro I. P53-induced inhibition of hif-1 causes cardiac dysfunction during pressure overload. Nature. 2007;446:444–448. doi: 10.1038/nature05602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Friehs I, Barillas R, Vasilyev NV, Roy N, McGowan FX, del Nido PJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor prevents apoptosis and preserves contractile function in hypertrophied infant heart. Circulation. 2006;114:I290–295. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.001289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liao CH, Akazawa H, Tamagawa M, Ito K, Yasuda N, Kudo Y, Yamamoto R, Ozasa Y, Fujimoto M, Wang P, Nakauchi H, Nakaya H, Komuro I. Cardiac mast cells cause atrial fibrillation through pdgf-a-mediated fibrosis in pressure-overloaded mouse hearts. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:242–253. doi: 10.1172/JCI39942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chu TF, Rupnick MA, Kerkela R, Dallabrida SM, Zurakowski D, Nguyen L, Woulfe K, Pravda E, Cassiola F, Desai J, George S, Morgan JA, Harris DM, Ismail NS, Chen JH, Schoen FJ, Van den Abbeele AD, Demetri GD, Force T, Chen MH. Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet. 2007;370:2011–2019. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61865-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schmidinger M, Zielinski CC, Vogl UM, Bojic A, Bojic M, Schukro C, Ruhsam M, Hejna M, Schmidinger H. Cardiac toxicity of sunitinib and sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5204–5212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Khakoo AY, Kassiotis CM, Tannir N, Plana JC, Halushka M, Bickford C, Trent J, 2nd, Champion JC, Durand JB, Lenihan DJ. Heart failure associated with sunitinib malate: A multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Cancer. 2008;112:2500–2508. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kerkela R, Grazette L, Yacobi R, Iliescu C, Patten R, Beahm C, Walters B, Shevtsov S, Pesant S, Clubb FJ, Rosenzweig A, Salomon RN, Van Etten RA, Alroy J, Durand JB, Force T. Cardiotoxicity of the cancer therapeutic agent imatinib mesylate. Nat Med. 2006;12:908–916. doi: 10.1038/nm1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chintalgattu V, Ai D, Langley RR, Zhang J, Bankson JA, Shih TL, Reddy AK, Coombes KR, Daher IN, Pati S, Patel SS, Pocius JS, Taffet GE, Buja LM, Entman ML, Khakoo AY. Cardiomyocyte pdgfr-beta signaling is an essential component of the mouse cardiac response to load-induced stress. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:472–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI39434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bock-Marquette I, Saxena A, White MD, Dimaio JM, Srivastava D. Thymosin beta4 activates integrin-linked kinase and promotes cardiac cell migration, survival and cardiac repair. Nature. 2004;432:466–472. doi: 10.1038/nature03000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Smart N, Risebro CA, Clark JE, Ehler E, Miquerol L, Rossdeutsch A, Marber MS, Riley PR. Thymosin beta4 facilitates epicardial neovascularization of the injured adult heart. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1194:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shrivastava S, Srivastava D, Olson EN, DiMaio JM, Bock-Marquette I. Thymosin beta4 and cardiac repair. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1194:87–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Takeda N, Manabe I, Uchino Y, Eguchi K, Matsumoto S, Nishimura S, Shindo T, Sano M, Otsu K, Snider P, Conway SJ, Nagai R. Cardiac fibroblasts are essential for the adaptive response of the murine heart to pressure overload. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:254–265. doi: 10.1172/JCI40295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kakkar R, Lee RT. Intramyocardial fibroblast myocyte communication. Circ Res. 2010;106:47–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.207456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gray MO, Long CS, Kalinyak JE, Li HT, Karliner JS. Angiotensin ii stimulates cardiac myocyte hypertrophy via paracrine release of tgf-beta 1 and endothelin-1 from fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;40:352–363. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schultz Jel J, Witt SA, Glascock BJ, Nieman ML, Reiser PJ, Nix SL, Kimball TR, Doetschman T. Tgf-beta1 mediates the hypertrophic cardiomyocyte growth induced by angiotensin ii. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:787–796. doi: 10.1172/JCI14190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tan SM, Zhang Y, Connelly KA, Gilbert RE, Kelly DJ. Targeted inhibition of activin receptor-like kinase 5 signaling attenuates cardiac dysfunction following myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1415–1425. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01048.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.McMullen JR. Role of insulin-like growth factor 1 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase in a setting of heart disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;35:349–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chen MM, Lam A, Abraham JA, Schreiner GF, Joly AH. Ctgf expression is induced by tgf- beta in cardiac fibroblasts and cardiac myocytes: A potential role in heart fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1805–1819. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yoon PO, Lee MA, Cha H, Jeong MH, Kim J, Jang SP, Choi BY, Jeong D, Yang DK, Hajjar RJ, Park WJ. The opposing effects of ccn2 and ccn5 on the development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;49:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, van der Made I, Herias V, van Leeuwen RE, Schellings MW, Barenbrug P, Maessen JG, Heymans S, Pinto YM, Creemers EE. Mir-133 and mir-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: Implications for a role of micrornas in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res. 2009;104:170–178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. 176p following 178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, Bang ML, Segnalini P, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Elia L, Latronico MV, Hoydal M, Autore C, Russo MA, Dorn GW, 2nd, Ellingsen O, Ruiz-Lozano P, Peterson KL, Croce CM, Peschle C, Condorelli G. Microrna-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007;13:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Liu N, Bezprozvannaya S, Williams AH, Qi X, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Microrna-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3242–3254. doi: 10.1101/gad.1738708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Barandon L, Couffinhal T, Ezan J, Dufourcq P, Costet P, Alzieu P, Leroux L, Moreau C, Dare D, Duplaa C. Reduction of infarct size and prevention of cardiac rupture in transgenic mice overexpressing frza. Circulation. 2003;108:2282–2289. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093186.22847.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Barandon L, Dufourcq P, Costet P, Moreau C, Allieres C, Daret D, Dos Santos P, Daniel Lamaziere JM, Couffinhal T, Duplaa C. Involvement of frza/sfrp-1 and the wnt/frizzled pathway in ischemic preconditioning. Circ Res. 2005;96:1299–1306. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000171895.06914.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]