Abstract

Previous studies of adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV among young injection drug users (IDU) have been limited because financial barriers to care disproportionately affect youth, thus confounding results. This study examines adherence among IDU in a unique setting where all medical care is provided free-of-charge. From May 1996 to April 2008, we followed a prospective cohort of 545 HIV-positive IDU of 18 years of age or older in Vancouver, Canada. Using generalized estimating equations (GEE), we studied the association between age and adherence (obtaining ART≥95% of the prescribed time), controlling for potential confounders. Using Cox proportional hazards regression, we also studied the effect of age on time to viral load suppression (<500 copies per milliliter), and examined adherence as a mediating variable. Five hundred forty-five participants were followed for a median of 23.8 months (interquartile range [IQR]=8.5–91.6 months). Odds of adherence were significantly lower among younger IDU (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=0.76 per 10 years younger; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.65–0.89). Younger IDU were also less likely to achieve viral load suppression (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR]=0.75 per 10 years younger; 95% CI, 0.64–0.88). Adding adherence to the model eliminated this association with age, supporting the role of adherence as a mediating variable. Despite absence of financial barriers, younger IDU remain less likely to adhere to ART, resulting in inferior viral load suppression. Interventions should carefully address the unique needs of young HIV-positive IDU.

Introduction

Outside Sub-Saharan Africa, a large proportion of new HIV infections remain attributable to transmission by injection drug use. The Joint United National Programme on HIV/AIDS estimates that approximately one third of such new infections are acquired by injection drug users (IDU),1 and in North America in particular, IDU represent approximately 1 in 5 new diagnoses of HIV infection.2,3 In some locations worldwide, most notably Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the proportion of new HIV cases ascribed to injection drug use approaches nearly two thirds.1

Concurrent injection drug use may also complicate successful management of HIV infection. Early administration of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been shown to decrease acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related opportunistic infections and improve survival,4 but ongoing injection drug use appears to be linked to poor ART adherence and rapid progression of HIV-related illness.5,6 Complete or near-complete adherence is required to reliably suppress HIV replication, and incomplete adherence may result in the rapid emergence of antiretroviral resistance.7 Moreover, delivery of care to HIV-infected IDU is often complicated by the unique life circumstances of this population, who experience high rates of homelessness, poverty, incarceration, and mental illness.8,9 For these reasons, clinicians and policymakers may be inclined to assume that IDU are less likely to benefit from ART, a finding substantiated by some studies.10–12 However, recent studies have highlighted that the survival of HIV-positive IDU is equivalent to that of their non-drug–using peers when ART adherence is similar,13 and that they are no more likely than non-IDU to develop antiretroviral resistance.14

It is therefore imperative to identify the factors that make certain IDU less likely to adhere to ART. In particular, it is worth considering whether younger age impacts ART adherence. Indeed, HIV infection is a clear risk factor for early mortality among at-risk youth.15,16 When compared to older IDU, younger IDU may demonstrate higher prevalence of homelessness, of recent sex trade involvement and of incarceration, and may also exhibit different (and often more intense) patterns of illicit drug use and lower enrollment in methadone maintenance therapy.17 Knowing how age impacts adherence and subsequent viral load suppression could inform policy development, resulting in programs that more effectively target younger members of this vulnerable population.18

Because British Columbia, Canada, has a universally accessible health care system and free provision of ART, it is a unique setting to study adherence to ART. IDU in British Columbia may obtain ART without user fees or copayments, and therefore analyses may be freer of the potentially confounding effect of financial barriers to ART access. Studies conducted elsewhere may be limited by the fact that younger IDU have fewer financial resources available to them and therefore may be less likely to afford a sustained supply of ART. The present study aims to examine the association between age and adherence among IDU, and to determine whether age ultimately affects attainment of viral load suppression.

Materials and Methods

Study sample

Data were collected from the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Access to Survival Services (ACCESS), a prospective cohort study of HIV-positive IDU that has been described previously.19,20 ACCESS was originally nested within the larger Vancouver Injection Drug User Study (VIDUS). Briefly, VIDUS participants have been recruited since May 1996 through self-referral and street-based outreach from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside neighborhood. Inclusion criteria for VIDUS were injection of illicit drugs in the month prior to study enrollment and residency in the Greater Vancouver region. The ACCESS cohort is comprised of all HIV-seropositive VIDUS participants (i.e., those that were HIV-positive at study entry or who seroconverted during follow-up). The sample in the present study was restricted to all ACCESS participants for whom baseline laboratory data were available (i.e., had CD4+ cell count and plasma viral load measured within 12 months of recruitment).

At baseline and semiannually thereafter, participants completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire soliciting sociodemographic data and information on drug use patterns. At each of these visits, HIV antibody testing was performed. All participants provided informed consent and were provided $20 (CAD) remuneration at each visit. VIDUS and ACCESS have been approved annually by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board.

Outcome variables

The first of two analyses sought to examine factors associated with antiretroviral adherence, measured using prescription refill compliance data.13,21 Adherence over the preceding 6 months was defined as the ratio of the number of days that ART was dispensed relative to the total number of days during the prior 6 months.13,21 Consistent with previous analyses, this ratio was dichotomized to 95% or more versus less than 95%.19,22–24 In British Columbia, all provision of ART is centralized through a province-wide antiretroviral dispensation program. Confidential linkage of records from this program to the ACCESS database allowed for accurate determination of adherence.13,25 Even if participants missed a study follow-up appointment, it was still possible to ascertain this variable from the centralized database. The second of the two analyses examined the outcome of time to HIV-1 RNA suppression, defined as having achieved plasma levels of less than 500 copies per milliliter during study follow-up. Since less than 500 copies per milliliter was the lower limit of detection for the plasma viral load assay for the early years of the study, we used this cut-off for the entire study period.

Explanatory variables

The primary explanatory variable considered in both analyses was age in years at time of enrollment, which was treated as a continuous variable for analyses except where otherwise indicated. Other time-varying, independent variables considered in multivariate analyses included male gender (yes versus no); Aboriginal ancestry (yes versus no); partnered relationship status (married, common law or single, regular partner versus single or dating); high school education (having completed high school versus not ever having completed high school); homelessness in the last 6 months (yes versus no); incarceration in the last 6 months (yes versus no); sex trade involvement in the last 6 months (having traded sex for money, drugs, shelter or gifts versus not having traded sex); daily alcohol consumption in the last 6 months (yes versus no); daily crack use (yes versus no); daily cocaine use in the last 6 months (yes versus no); daily heroin use in the last 6 months (yes versus no); daily crystal methamphetamine use in the last 6 months (yes versus no); nonfatal overdose in the last 6 months (yes versus no); use of outreach services in the last 6 months (use of Alcoholics' and/or Narcotics' Anonymous, outreach worker, street nurse, health van, food bank, drop-in center, or supervised injection site versus no use of any of these services); and enrollment in drug treatment including methadone maintenance therapy in the last 6 months (yes versus no). Less than daily frequency of use of alcohol and drugs was explored as possibly influential on adherence to ART. However, preliminary analyses revealed that the vast majority of participants had at least weekly use of many substances; therefore, greater specificity of frequent substance use was felt to have been attained with a cutoff of daily use of these substances, as in previous analyses.17

Effect of age on adherence to ART

In our first analysis, which focused on adherence as an outcome, we examined bivariate relationships between adherence and the explanatory variables listed above in a series of bivariate generalized estimating equations (GEE). In order to adjust for possible confounders in subsequent multivariate analyses, we employed a variable selection process described previously.26 For a variable to have been considered a confounder of the relationship between age and adherence, it had to be associated with both variables and not be in the causal pathway between the two variables. We employed a conservative p value cutoff ≤0.20 to determine which candidate variables were associated with adherence in the bivariate GEE analyses described above. We then included all these variables in a “full” multivariate model (using multiple logistic regression) and, in a stepwise manner, removed all variables that did not change the coefficient for the effect of age on adherence by at least 5%. Remaining variables were considered confounders and were included in all subsequent multivariate analyses (including those in which viral load suppression was the outcome variable of interest).

In addition, baseline CD4+ cell count (as a continuous variable, in cells/μL) and baseline plasma viral load (as a continuous variable, in log10[number of copies per milliliter]) were forced into all analyses in order to control for eligibility for ART. This was done because distribution of ART in the province of British Columbia and elsewhere has traditionally been based on CD4 cell count and plasma HIV RNA levels,27 and since these levels have changed over time, it was appropriate to adjust for these values.44 Once additional sociodemographic and drug use-related confounders were identified, we used GEE to examine the effect of age on adherence, including the selected and forced variables in the multivariate model.

Effect of age on viral load suppression and mediation by adherence

For the second analysis, we sought to identify the relationship between age and viral load suppression while on ART, and more specifically, whether adherence explained any relationship between these two variables. (Stated differently, we were interested in determining whether adherence was a mediating variable in the relationship between age and viral load suppression.) To do so, we employed Cox proportional hazards regression with time to attainment of viral load suppression as the primary outcome of interest. Explanatory variables again included age as well as baseline CD4+ cell count and baseline plasma HIV RNA to control for ART eligibility. This analysis was limited to participants who initiated ART during the observation period (i.e., it did not include participants who were already on ART at the time of enrollment), with time “zero” defined as the date of ART initiation. Finally, to examine whether adherence mediated the effect of age on viral load suppression, we ran an additional Cox proportional hazards regression model in which the adherence variable was added and examined whether the age variable maintained its statistical significance.28,29

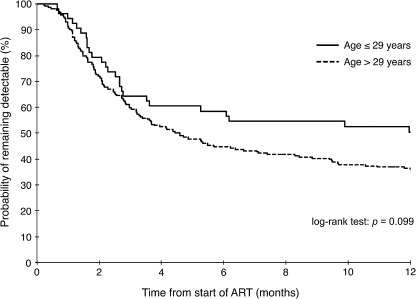

Finally, a Kaplan-Meier survival curve was for time to viral load suppression, with age dichotomized to 29 years or younger versus older than 29 years. A sensitivity analysis was conducted in preliminary data analyses that revealed substantial differences in adherence among those 29 years or younger when compared to those older than 29 years with relatively comparable adherence among members within these two separate groups. As such, little data were felt to be lost by combining youth 29 years or younger together and adults older than 29 years together.

We performed all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). All reported p values are two-sided and considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

From May 1996 to April 2008, 545 ACCESS participants met inclusion criteria for the present analysis and provided a median of 23.8 months (interquartile range [IQR], 8.5–91.6 months) of prospective follow-up. Median age of eligible participants was 37.2 years (IQR, 31.1–43.6 years). At baseline, 195 (35.8%) of participants were already on ART. Of these, 66 (33.8%) discontinued ART during the follow-up period. Of the 350 who were not on ART at baseline, 211 (60.3%) initiated ART during follow-up. Table 1 demonstrates baseline characteristics of the study sample stratified by age. (Although age is treated as a continuous variable throughout the present study, it is presented in Table 1 as a dichotomized variable, 29 years or younger versus older than 29 years at ART initiation, for ease of interpretation.) Median baseline CD4+ cell count among those aged 29 years or less was 380 cells per microliter (IQR, 260–540 cells per microliter) and among those older than 29 years was 330 cells per microliter (IQR, 200–480 cells per microliter; p=0.004, Wilcoxon rank sum test). Median baseline viral load among those 29 years or younger was 33,000 copies per milliliter (IQR, 5500–83,000 copies per milliliter) and among those older than 29 years was 13,000 copies per milliliter (IQR, 359–61,600; p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic Characteristics and Substance Use Behaviors Among HIV-Positive IDU, Stratified by Age

| |

|

Age |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total (%) (n=545) | ≤29 yrs (%) (n=107) | >29 yrs (%) (n=438) | p Value |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||

| Male gender | 341 (62.6) | 42 (39.3) | 299 (68.3) | <0.001 |

| Aboriginal ancestry | 185 (33.9) | 45 (42.1) | 140 (32.0) | 0.048 |

| In relationshipa | 143 (26.2) | 19 (17.8) | 124 (28.3) | 0.026 |

| Completed high school | 76 (13.9) | 22 (20.6) | 54 (12.3) | 0.028 |

| Recently homelessb | 143 (26.2) | 35 (32.7) | 108 (24.7) | 0.090 |

| Recently incarceratedb | 137 (25.1) | 31 (29.0) | 106 (24.2) | 0.308 |

| Sex trade involvementb | 135 (24.8) | 58 (54.2) | 77 (17.6) | <0.001 |

| Substance use behaviorsb | ||||

| Daily alcohol use | 68 (12.5) | 15 (14.0) | 53 (12.1) | 0.590 |

| Daily crack use | 132 (24.2) | 24 (22.4) | 108 (24.7) | 0.630 |

| Daily cocaine use | 192 (35.2) | 49 (45.8) | 143 (32.7) | 0.011 |

| Daily heroin use | 152 (27.9) | 45 (42.1) | 107 (24.4) | <0.001 |

| Daily crystal meth injection | 169 (31.0) | 24 (22.4) | 145 (33.1) | 0.032 |

| Recently overdosedb | 75 (13.8) | 23 (21.5) | 52 (11.9) | 0.010 |

| Use of outreach servicesc | 516 (94.7) | 98 (91.6) | 418 (95.4) | 0.112 |

| Enrolled in drug treatment (including methadone maintenance therapy)b | 330 (60.6) | 72 (67.3) | 258 (58.9) | 0.112 |

Is legally married, is in common law relationship, or has a regular partner.

Denotes behaviors during 6 months prior to baseline interview.

Includes use of Alcoholics' and/or Narcotics' Anonymous, outreach worker, street nurse, health van, food bank, drop-in center, or supervised injection site.

IDU, injection drug user.

There were 1186 (26.6%) periods in which individuals were more than 95% adherent of 4460 total observations. Of these periods of adherence, 222 observations (18.7%) were by participants 29 years of age or younger, and 964 (81.3%) were by participants older than 29 years. Table 2 compares sociodemographic and recent substance use behaviors associated with adherence to ART as obtained from univariate GEE analyses. All variables significant at p<0.20 were eligible for inclusion in subsequent multivariate modeling using the variable selection process outlined in the Methods section. Gender was not included in the final multivariate model. Importantly, no outreach service (i.e., use of Alcoholics' and/or Narcotics' Anonymous, outreach worker, street nurse, health van, food bank, or drop-in center) was associated with increased likelihood of adhering to ART, and therefore were also not included in the final multivariate model. Ultimately, the only variable that independently altered the effect of age on adherence by 5% or more using the variable selection process outlined in the Methods section was sex trade involvement in the last six months.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Recent Substance Use Behaviors Associated with Adherence to ART Among HIV-Positive IDU in Univariate GEE Analysis

| Characteristic | Crude odds ratio, OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | ||

| Age (per 10 years younger) | 0.56 (0.48–0.65) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 1.46 (1.11–1.91) | 0.006 |

| Aboriginal ancestry | 0.97 (0.74–1.28) | 0.841 |

| In relationshipa | 0.98 (0.82–1.17) | 0.800 |

| Completed high school | 1.79 (1.18–2.73) | 0.007 |

| Recently homelessb | 0.63 (0.51–0.77) | <0.001 |

| Ever incarcerated | 0.69 (0.58–0.81) | <0.001 |

| Sex trade involvement | 0.52 (0.41–0.67) | <0.001 |

| Substance use behaviorsb | ||

| Daily alcohol use | 0.64 (0.47–0.86) | 0.004 |

| Daily crack use | 0.94 (0.78–1.13) | 0.509 |

| Daily cocaine use | 0.48 (0.40–0.57) | <0.001 |

| Daily heroin use | 0.38 (0.30–0.48) | <0.001 |

| Daily crystal meth use | 0.71 (0.44–1.14) | 0.152 |

| Overdosed | 0.61 (0.46–0.81) | <0.001 |

| Use of outreach servicesc | 1.11 (0.87–1.40) | 0.405 |

| Enrolled in drug treatment (including methadone maintenance therapy) | 1.50 (1.26–1.79) | <0.001 |

Is legally married, is in common law relationship, or has a regular partner.

Denotes during preceding 6 months.

Includes use of Alcoholics' and/or Narcotics' Anonymous, outreach worker, street nurse, health van, food bank, drop-in center, or supervised injection site.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; IDU, injection drug user; GEE, generalized estimating equations; CI, confidence interval.

Once age and recent sex trade involvement were included in multivariate GEE analysis and were controlled for baseline ART eligibility, their respective adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were 0.76 per 10 years younger (95% CI, 0.65–0.89; p<0.001) and 0.52 (95% CI, 0.38–0.71; p<0.001).

Table 3 illustrates the results of the Cox proportional hazards regression model examining the effect of age on plasma HIV RNA. As outlined in the table, the model that included age as an explanatory variable (additionally controlled for ART eligibility) revealed a strongly statistically significant effect of age on viral load suppression, with older IDU demonstrating greater likelihood of obtaining viral load suppression relative to younger IDU. However, in the next model, when adherence was included as an additional explanatory variable, this effect of age was no longer statistically significant, strongly indicating that the effect of age on viral load suppression was mediated by adherence.28,29 To confirm this, a Sobel test was performed to test for mediation, which was significant (Sobel statistic, 3.08; p=0.002).30

Table 3.

Adjusteda Hazard Ratios Highlighting the Effect of Age (per 10 Years Younger) on Time to Viral Load Suppression in Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Models

| Model | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Effect of age, without adherence (mediator) variable included | 0.75 (0.64–0.88) | <0.001 |

| Effect of age, including adherence (mediator) variableb | 0.85 (0.72–1.01) | 0.06 |

Additionally adjusted for baseline CD4+ count (AHR, 0.90 for each increase of 100 cells per microliter; 95% CI, 0.84–0.97 in model with adherence) and viral load (AHR, 0.55 for each log10 decrease in counts per milliliter; 95% CI, 0.44–0.69 in model with adherence).

Sobel test for mediation: statistic, 3.08; p=0.002.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 1 demonstrates a Kaplan-Meier curve in which age was dichotomized to 29 years or less and more than 29 years with the outcome of viral load suppression. Log-rank test was not significant for a difference in time to viral load suppression when age was dichotomized in this fashion (p=0.099).

FIG. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for time to viral load suppression (<500 copies per milliliter) after starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) for first 12 months of study follow-up (n=267).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we observed poorer adherence and attainment of viral load suppression among young IDU compared to their older counterparts. Our results are unique because they are conducted in the setting of universal health care, where all medical care, including provision of HIV-related care and ART, is delivered free of charge. In studies of non-drug–using adults, younger age has been associated with poorer adherence to ART,18 a finding that has been replicated in HIV-infected IDU populations.31,32 However, to our knowledge, our study represents the first to have examined this association in a setting in which ART is provided in a public health care system without any copayments or other financial prerequisites. It is particularly important to consider such barriers when considering the effect of age on adherence, since, in general, young adult patients may have fewer financial resources available to them than older patients.33,34 In settings where medical care is not universally available, it would be reasonable to hypothesize that younger IDU may be less likely to continue ART because they cannot afford their medical visits or their medication copayments. Although our participants may face additional barriers related to personal finances (e.g., lack of transportation to medical appointments or to the pharmacy), we believe that, in general, financial barriers are substantially reduced for our participants.

Given that young age remained strongly linked with poor adherence in our sample despite such barriers being minimal, it is important to consider non-economic reasons for lower adherence among younger IDU. Aboriginal ethnicity, which in another similar study was marginally associated with increased time to HIV care,35 was associated with younger age in our study, but not with poor adherence to ART. An important finding in our study was that younger age was, in univariate analyses, associated with a unique set of other sociodemographic characteristics and risk-taking behaviors, such as homelessness, incarceration, and use of crystal methamphetamine. These findings are consistent with other studies of injection drug users showing that younger age is correlated with increased prevalence of risk-taking behavior.34,36,37 Because increased prevalence of such risk-taking behaviors were additionally associated with poor adherence in univariate analyses in our study, it appears that the young people in our study were dually less likely to adhere to ART regimens and more likely to engage in risk behaviors, a finding replicated elsewhere.38 The same association also appears to apply to those with recent sex trade involvement in our study, who were independently more likely to demonstrate poor adherence. Taken together, these findings may suggest common, underlying psychological profile among some of the youth in our study, that is, youth willing to engage in greater risk-taking with regard to drug use and sexual behaviors may also be more likely to assume the risks of poor HIV medication compliance.39 Indeed, impulsivity appears to be an important risk factor for poor ART adherence among HIV-positive youth elsewhere.40 If this is indeed true, it highlights a need for specially tailored interventions that address the special emotional and developmental concerns of younger IDU.41

Similarly, it may be that younger IDU are more difficult to engage in effective medical care. Interestingly, among mainstream patients accessing primary care in the United Kingdom, another setting providing universal medical care, younger patients were less likely to perceive that the care they received was of high quality.42 If this principle can be generalized to IDU populations, it may be that young IDU are less likely to have a favorable view of their HIV-related care, and are therefore less likely to adhere to ART. Indeed, among patients living with HIV, patients reporting better engagement with their health care provider also report improved adherence to ART and to provider advice when compared to those with poorer engagement.43 Again, these findings suggest that attempts to improve ART among younger IDU may require special consideration of the unique health care needs of younger individuals living with a chronic disease such as HIV.

This study has several limitations. First, because ACCESS is an observational cohort, the potential effect of unmeasured confounders must be considered when interpreting the effect of age on adherence. Still, our analysis included a substantial array of explanatory variables and we used a relatively liberal approach to variable selection in our multivariate models.26 Second, because adherence was defined in our study using prescription refill compliance, it is important to consider that IDU in our study may have been filling prescriptions but not necessarily taking ART exactly as prescribed. However, the measure of adherence used in this study has previously been shown to predict virologic suppression,23 CD4+ cell count response,44 and survival,13,21 and therefore is likely to be a clinically significant marker of ART effectiveness.

Third, in interpreting our results, it is important to consider that during the 12-year study period, there were likely to have been several secular trends that may have affected adherence across the cohort. For example, ART regimens have been vastly simplified in recent years to reduce the number of pills an individual must take, a fact that has resulted in improved adherence among at-risk populations.45 Although it is likely that the earlier complexity of ART regimens universally affected adherence among all IDU, it is possible that these regimens disproportionately affected adherence among younger compared to older IDU. Fourth, our study drew on some self-reported information, and given the sensitive nature of many questions, there may have been some degree of socially desirable reporting among the youth interviewed, even despite our efforts to assure confidentiality and build trust with all participants.46 The effect of this would be to underestimate the true prevalence of some of the risk behaviors examined.

This study adds new knowledge to the literature on provision of HIV care by delineating the lower likelihood of younger IDU and those engaged in sex work to adhere to ART and to obtain viral load suppression. In particular, our work is unique among studies because it demonstrates this poor adherence in the setting of universal health care and free provision of ART, and therefore these results are less likely to be confounded by the financial barriers to obtaining ART that IDU may encounter in other settings. Although it is increasingly becoming apparent that IDU, like their non-drug-using peers, greatly benefit from access to ART,13 it is clear that IDU represent a heterogeneous population with differential adherence despite universal availability of ART. Although expanding services to aid all IDU in adhering to ART is merited, our findings suggest that in redoubling efforts to do so, policymakers might heed the apparent vulnerability of young IDU and sex workers to even poorer rates of adherence than their other injecting peers.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Vancouver Injection Drug User Study (VIDUS) and AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Access to Survival Services (ACCESS) participants for their willingness to be included in the study, as well as current and past VIDUS/ACCESS investigators and staff. We also acknowledge Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Brandon Marshall, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, Benita Yip, and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance.

The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA021525) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-79297, RAA-79918). Dr. Kerr is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Mr. Malloy is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. None of the aforementioned organizations had any further role in study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Drs. Hadland, Kerr, and Wood designed the study. Drs. Hadland and Wood wrote the protocol. Dr. Hadland conducted the literature review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Ms. Zhang undertook statistical analyses with additional input from Drs. Hadland and Wood. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Montaner has received educational grants from, served as an ad hoc advisor to or spoken at various events sponsored by Abbott Laboratories, Agouron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Borean Pharma AS, Bristol–Myers Squibb, DuPont Pharma, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann–La Roche, Immune Response Corporation, Incyte, Janssen–Ortho Inc., Kucera Pharmaceutical Company, Merck Frosst Laboratories, Pfizer Canada Inc., Sanofi Pasteur, Shire Biochem Inc., Tibotec Pharmaceuticals Ltd., and Trimeris Inc.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 2008 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2008. www.unaids.org:80/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/ [Aug 9;2010 ]. www.unaids.org:80/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/

- 2.CDC. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: Cases of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Depedent Areas, 2005. Vol. 17. Revised June 2007. www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2005report/ [Aug 9;2010 ]. www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2005report/

- 3.Karon JM. Fleming PL. Steketee RW. De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the century: An epidemic in transition. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1060–1068. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Sadr WM. Lundgren JD. Neaton JD, et al. CD4+ count-guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2283–2296. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucas GM. Cheever LW. Chaisson RE. Moore RD. Detrimental effects of continued illicit drug use on the treatment of HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:251–259. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucas GM. Griswold M. Gebo KA. Keruly J. Chaisson RE. Moore RD. Illicit drug use and HIV-1 disease progression: A longitudinal study in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:412–420. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeks SG. Treatment of antiretroviral-drug-resistant HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 2003;362:2002–2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Treisman GJ. Angelino AF. Hutton HE. Psychiatric issues in the management of patients with HIV infection. JAMA. 2001;286:2857–2864. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood E. Montaner JS. Yip B, et al. Adherence and plasma HIV RNA responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected injection drug users. CMAJ. 2003;169:656–661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loughlin A. Metsch L. Gardner L. Anderson-Mahoney P. Barrigan M. Strathdee S. Provider barriers to prescribing HAART to medically-eligible HIV-infected drug users. AIDS Care. 2004;16:485–500. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maisels L. Steinberg J. Tobias C. An investigation of why eligible patients do not receive HAART. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2001;15:185–191. doi: 10.1089/10872910151133701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson IB. Landon BE. Hirschhorn LR, et al. Quality of HIV care provided by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:729–736. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood E. Hogg RS. Lima VD, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and survival in HIV-infected injection drug users. JAMA. 2008;300:550–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werb D. Mills EJ. Montaner JS. Wood E. Risk of resistance to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive injecting drug users: A meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:464–469. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy E. Haley N. Boudreau JF. Leclerc P. Boivin JF. The challenge of understanding mortality changes among street youth. J Urban Health. Jan. 2009;87:95–101. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy E. Haley N. Leclerc P. Sochanski B. Boudreau JF. Boivin JF. Mortality in a cohort of street youth in Montreal. JAMA. 2004;292:569–574. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller CL. Strathdee SA. Li K. Kerr T. Wood E. A longitudinal investigation into excess risk for blood-borne infection among young injection drug users (IUDs) Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:527–536. doi: 10.1080/00952990701407397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta S. Moore R. Graham N. Potential factors affecting adherence with HIV therapy. AIDS. 1997;11:1665. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199714000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palepu A. Tyndall MW. Joy R, et al. Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: The role of methadone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strathdee SA. Patrick DM. Currie SL, et al. Needle exchange is not enough: Lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11:F59–65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood E. Hogg RS. Yip B. Harrigan PR. O'Shaughnessy MV. Montaner JS. Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV-infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4+ cell count is 0.200 to 0.350×10(9) cells/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:810–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogg RS. Heath K. Bangsberg D, et al. Intermittent use of triple-combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up. AIDS. 2002;16:1051–1058. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Low-Beer S. Yip B. O'Shaughnessy MV. Hogg RS. Montaner JS. Adherence to triple therapy and viral load response. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23:360–361. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palepu A. Yip B. Miller C, et al. Factors associated with the response to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patients with and without a history of injection drug use. AIDS. 2001;15:423–424. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood E. Kerr T. Marshall BD, et al. Longitudinal community plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations and incidence of HIV-1 among injecting drug users: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:b1649. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldonado G. Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson MA. Aberg JA. Cahn P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraemer H. Stice E. Kazdin A. Offord D. Kupfer D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:848. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothman K. Greenland S. Lash T. Modern Epidemiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kastrissios H. Su√°rez J-Rn. Katzenstein D. Girard P. Sheiner LB. Blaschke TF. Characterizing patterns of drug-taking behavior with a multiple drug regimen in an AIDS clinical trial. AIDS. 1998;12:2295–2303. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199817000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moatti JP. Carrieri MP. Spire B, et al. Adherence to HAART in French HIV-infected injecting drug users: The contribution of buprenorphine drug maintenance treatment. AIDS. 2000;14:151–155. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Callahan ST. Cooper WO. Uninsurance and health care access among young adults in the United States. Pediatrics. 2005;116:88–95. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callahan ST. Cooper WO. Access to health care for young adults with disabling chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:178–182. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plitt SS. Mihalicz D. Singh AE. Jayaraman G. Houston S. Lee BE. Time to testing and accessing care among a population of newly diagnosed patients with HIV with a high proportion of Canadian Aboriginals, 1998–2003. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:93–99. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans JL. Hahn JA. Page-Shafer K, et al. Gender differences in sexual and injection risk behavior among active young injection drug users in San Francisco (the UFO Study) J Urban Health. 2003;80:137–146. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roy E. Haley N. Leclerc P. Cedras L. Blais L. Boivin JF. Drug injection among street youths in Montreal: Predictors of initiation. J Urban Health. 2003;80:92–105. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mellins CA. Tassiopoulos K. Malee K, et al. Behavioral health risks in perinatally HIV-exposed youth: Co-occurrence of sexual and drug use behavior, mental health problems, and nonadherence to antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:413–422. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson TE. Barròn Y. Cohen M, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its association with sexual behavior in a national sample of women with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:529–534. doi: 10.1086/338397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malee K. Williams P. Montepiedra G, et al. Medication adherence in children and adolescents with HIV infection: Associations with behavioral impairment. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:191–200. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudy BJ. Murphy DA. Harris DR. Muenz L. Ellen J. Patient-related risks for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected youth in the United States: A study of prevalence and interactions. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23:185–194. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campbell JL. Ramsay J. Green J. Age, gender, socioeconomic, and ethnic differences in patients' assessments of primary health care. Qual Health Care. 2001;10:90–95. doi: 10.1136/qhc.10.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakken S. Holzemer WL. Brown MA, et al. Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2000;14:189–197. doi: 10.1089/108729100317795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood E. Montaner JS. Yip B, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and CD4 T-cell count responses among HIV-infected injection drug users. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bangsberg DR. Ragland K. Monk A. Deeks SG. A single tablet regimen is associated with higher adherence and viral suppression than multiple tablet regimens in HIV+ homeless and marginally housed people. AIDS. 2010;24:2835–2840. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328340a209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Des Jarlais DC. Sloboda Z. Friedman SR. Tempalski B. McKnight C. Braine N. Diffusion of the D.A.R.E and syringe exchange programs. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1354–1358. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]