Abstract

The current study provides a qualitative test of a recently proposed application of an Information, Motivation, Behavioral Skills (IMB) model of health behavior situated to the social-environmental, structural, cognitive-affective, and behavioral demands of retention in HIV care. Mixed-methods qualitative analysis was used to identify the content and context of critical theory-based determinants of retention in HIV care, and to evaluate the relative fit of the model to the qualitative data collected via in-depth semi-structured interviews with a sample of inner-city patients accessing traditional and nontraditional HIV care services in the Bronx, NY. The sample reflected a diverse marginalized patient population who commonly experienced comorbid chronic conditions (e.g., psychiatric disorders, substance abuse disorders, diabetes, hepatitis C). Through deductive content coding, situated IMB model-based content was identified in all but 7.1% of statements discussing facilitators or barriers to retention in HIV care. Inductive emergent theme identification yielded a number of important themes influencing retention in HIV care (e.g., acceptance of diagnosis, stigma, HIV cognitive/physical impairments, and global constructs of self-care). Multiple elements of these themes strongly aligned with the model's IMB constructs. The convergence of the results from both sets of analysis demonstrate that participants' experiences map well onto the content and structure of the situated IMB model, providing a systematic classification of important theoretical and contextual determinants of retention in care. Future intervention efforts to enhance retention in HIV care should address these multiple determinants (i.e., information, motivation, behavioral skills) of self-directed retention in HIV care.

Introduction

Current standards of HIV clinical care in the United States recommend one medical visit (including CD4 and viral load evaluation) with a primary care provider every 3–4 months for asymptomatic patients prescribed antiretroviral (ARV) treatment.1 For many patients, especially those with comorbid illnesses, such as those found in the current sample (e.g., psychiatric disorders, substance abuse disorders, diabetes, hepatitis C), more frequent visits are often warranted. Failure to attend HIV care in the recommended intervals has been consistently associated with increased odds of mortality and poorer viral suppression.2–6 Despite the dramatic negative effects on clinical outcomes, retention in HIV care, once initiated, is problematic for some 30%7 to 41%8 of people living with HIV (PLWH) in the United States. Additionally, poor retention in care is a critical public health concern in terms of controlling individual and community level viral burden9,10; key components of test-and-treat strategies.10,11 Presently, there are few behavioral models and little in-depth research to guide our understanding of critical factors that influence care utilization once individuals have enrolled in (are linked to) HIV care, which extend beyond patient demography or simple correlates.9 Therefore, a theoretical framework that provides an in-depth, systematic understanding of the core facilitators and barriers to self-sustained retention in HIV care is desperately needed to inform efforts supporting PLWH in maintaining routine HIV care within the recommended intervals.9,12–14

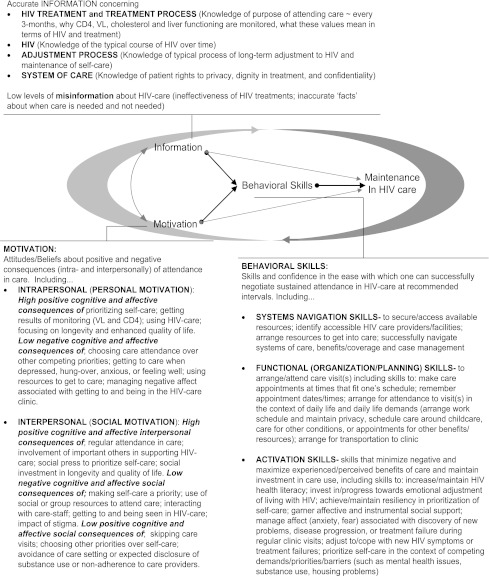

Recent research has sought to identify individual-level factors associated with retention in care that may be amenable to behavior change efforts (e.g., health beliefs, acceptance of HIV status, abilities to overcome practical barriers to care) through the use of qualitative methodologies.15–21 In line with these efforts, Amico and colleagues22,23 recently proposed an application of the Information, Motivation, Behavioral Skills (IMB) model,24 and more specifically of the IMB model of antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence,25 as an explanatory model of how such factors can be systematically organized, identified, and targeted through theoretically informed intervention efforts to support initiation and maintenance in clinical care for chronic medical conditions. This model, the situated Information, Motivation, Behavioral Skills (sIMB) model of Care Initiation and Maintenance for chronic diseases (see Fig. 1), provides a detailed exploration of how an IMB model framework could apply to understanding the behavioral dynamics of self-sustained retention in HIV care. Also identified by this situated IMB model are specific contextual factors, related to engagement in care for chronic conditions that may shape, or “situate”, the kinds of information, motivation, and behavioral skills most relevant to engagement in care. Specifically, both affective (i.e., acceptance of diagnosis or disease stigma) and socio-cultural-environmental contexts (i.e., comorbid mental health or substance use issues, community or cultural norms about engaging in medical care for non-acute conditions, or availability of trusted care providers) are incorporated into the core constructs of the sIMB model. These factors reflect the contexts within which individuals experience living with and obtaining care for their chronic medical condition(s).

FIG. 1.

Situated Information, Motivation, Behavioral Skills model of Retention in HIV Care. (Reproduced from Amico22 with kind permission from the Journal of Health Psychology.

An IMB-based model situated to retention in HIV care

The IMB model, as a model of health behavior change,26 has amassed considerable support over the last 20 years across a host of diverse health behaviors (e.g., HIV prevention, ART adherence, diabetes self-care), and forms the basis of the sIMB model of Care Initiation and Maintenance for chronic medical conditions.22 Across the body of work examining the IMB model26, individuals' levels of information, motivation, and behavioral skills have consistently been shown to predict self-directed health promotion behaviors.24,27 The IMB model27 applied to retention in HIV care would propose that: (1) well-informed, highly-motivated individuals who possess adequate skills for enacting complex patterns of behavior identified as requisite for long-term retention in HIV care will engage in this behavior optimally over time; (2) feedback from execution of the behavior (i.e., self-sustained retention in care) further influences each of the core determinants of the model, and, in turn, the health behavior at focus; and (3) the model is meditational, with the effects of information and motivation on behavior generally “working through,” and limited by an individual's level of behavioral skills,27 particularly for more complex health behaviors (e.g., self-sustained retention in care).

In situating the IMB model to retention in HIV care, the only divergence from previous IMB model applications is that the moderation hypothesis of the IMB model26,27 was handled somewhat differently. Factors identified as moderators in other applications of the IMB model, such as acute depression, homelessness, or active drug use, are used in the situated approach within each of the core IMB model constructs to shape the types of information, motivation, and behavioral skills important for retention in HIV care. Previous IMB models27 have suggested that such moderators, when present at very high levels, may influence the relations among the IMB model determinants of the behavior and the behavior itself, although the relations between IMB model constructs and behavior have generally been shown to be robust for populations with high levels of depression, homelessness, or drug use. The relative value of incorporating moderating variables into the core IMB constructs, versus retaining them as external moderators, was not the focus of the current research. Rather, it sought to provide a qualitative evaluation of a situated approach in which factors such as depression, substance use, coping, and affect regulation are explicitly explored in relation to their influence on the content of retention-relevant IMB elements.

The current research provides the first qualitative test of a situated application of the IMB model27 to retention in HIV care,22,23 through the systematic evaluation of patients' perceived facilitators and barriers to retention in HIV care, using richly detailed key informant interviews. The experiences of PLWH and their perceptions of engagement and retention in HIV care are specifically evaluated in terms of (1) the relative fit of participants' self-reported experiences of retention in HIV care to the sIMB model, as well as (2) the identification of critical content associated with each of the core theoretical determinants (i.e., information, motivation, behavioral skills). As efforts to understand the dynamics of patient retention in HIV care continue to expand, the application of vetted health behavior change models will be increasingly valuable to researchers and practitioners seeking to target and enhance retention in HIV care.

Methods

Participants and study design

Between February and May 2009, twenty HIV-infected men (n=12) and women (n=8) residing in the Bronx, NY, and accessing either traditional HIV-primary care services at a community clinic or nontraditional services through providers and staff comprising a mobile medical outreach team28,29 participated in an in-depth semi-structured interview about their HIV care experiences since being diagnosed with HIV. The community clinic provides adult primary care and integrated HIV and specialty care services to a predominantly low-income ethnic minority inner-city population. The medical outreach team, affiliated with the community clinic, was developed to provide mobile primary care services to HIV-infected clients residing in the same local community as the clinical care site, who may face additional barriers to accessing care related to housing instability and/or substance use.28,29

Sampling was stratified between the community clinic (n=10) and medical outreach venues (n=10) to ensure that a range of HIV care experiences were represented. In line with qualitative procedures,30 interviews were conducted until a saturation of responses was obtained (i.e., interviews were no longer producing novel information). Participants were recruited at point of contact with their respective HIV care service, and were eligible to participate if they were English speaking and reported first initiating HIV care a minimum of 24 months prior to recruitment. All participants consented to their interview being audiotaped; however, because of equipment failure, only 18 of the 20 interviews were successfully recorded for further transcription and analysis. The saturation of participant responses was maintained with the recorded interviews, which averaged 27 min in length. All participants were compensated $15 cash for their participation, and study protocols were approved by the University of Connecticut and Albert Einstein College of Medicine's institutional review boards.

Measures

The interview guide developed for the present research elicited participants' experiences with accessing and utilizing HIV care services through both structured and open-ended items (structured and open-ended items are available at www.chip.uconn.edu/chipweb/supplemental/QualHIVCare.pdf). Open-ended qualitative items were specifically designed to elicit participants' spontaneous responses30 about their HIV care utilization experiences since diagnosis, with an emphasis on experiences related to participant retention in care. The first set of open-ended items prompted participants to reflect on their general HIV care experiences initiating HIV care post-diagnosis and maintaining themselves in HIV care over time (i.e., retention), factors related to prolonged absences from HIV-clinical care of 6 months or more, and re-engaging in care following such a prolonged absence. A second set of open-ended items that were theoretically guided by the sIMB model then broadly elicited participants' perceptions of retention-relevant HIV treatment information, motivation for engaging/not engaging in HIV medical care, and behavioral skills used to negotiate attendance at HIV medical care appointments. Analysis indicated that there was no significant difference in the proportion of sIMB content identified across participants' responses to the two sets of open-ended items; therefore, the remaining analysis and results are not differentiated by question type.

Analytical methods

Structured demographic and HIV care items were analyzed via SPSS version 17.031 to characterize the study sample. Qualitative data were prepared for analysis by transcribing interviews verbatim, independently checking transcripts for accuracy, and segmenting transcripts for coding30 once uploaded into the qualitative analysis program, ATLAS.ti.32 A “segment” of text (i.e., meaningful unit of analysis)33 was defined as any participant discourse that contained a single train of thought. Once utterances moved to a new train of thought, a new independent text segment was marked. Coders mutually agreed upon the body of discourse identified as a single segment of text, identifying a total of 665 text segments, which were then systematically coded across 18 interviews. There was no significant difference between number of segments per interview and participant recruitment venue (i.e., community clinic or medical outreach team).

Transcripts were iteratively coded by trained coders in ATLAS.ti,32 using established coding protocols.30 Each text segment was first coded for mutually exclusive factors identifying the type of HIV care experience (i.e., initiation or retention in care), and whether the segment content reflected a barrier, facilitator, or both. Next, a series of non-mutually-exclusive theory-based codes were applied. This code set was derived from the sIMB model and related correlates of retention in care anticipated to be of relevance to patients' experiences in the current study (see Table 1, left two columns for non-mutually-exclusive codes and code definitions). Through this process, segments that did not contain sIMB-based content could be identified to capture facilitators and barriers relevant to participants' retention in care that might not have been included in the sIMB constructs.22 Inter-rater reliability between coders yielded an overall Kappa of 0.81 (Type of HIV care, κ=0.93; HIV care facilitators/barriers, κ=0.72; sIMB content, κ=0.78) indicating good reliability.34,35

Table 1.

Frequency of Observed Theoretical Content Across Retention-Related Discourse

| |

|

Frequency (%) of retention text segments |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content codes | Code definitions | Facilitator (k=162) | Barrier (k=77) | Total (k=239) |

| Information | 34 (21%) | 10 (13%) | 44 (18.4%) | |

| Accurate information | Accurate knowledge of HIV disease, availability of care, HIV treatment recommendations/procedures/benefits/consequences. | 26 | 2 | 28 |

| Misinformation | Incorrect knowledge of HIV disease, availability of care, HIV treatment recommendations/procedures/benefits/consequences. | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Cognitive heuristics | Accurate/inaccurate implicit theories common to the local/regional culture regarding reasons to access care or associated costs/consequences of care. | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| Motivation | 157 (97%) | 64 (83%) | 221 (92.5%) | |

| Personal attitudes/beliefs | Attitudes/beliefs toward having HIV or engaging in HIV care system related to one's previous experiences or cultural beliefs. | 27 | 7 | 34 |

| Perceived vulnerability | Attitudes/beliefs about the perceived personal benefit or positive/negative consequences of accessing available HIV care/treatment/medications. | 53 | 4 | 57 |

| Competing priorities | Attitudes/beliefs about engaging in HIV care in the context of daily hassles (work/child care) or comorbidities (depression). | 1 | 23 | 24 |

| Patient–provider relationships | Perceptions of trust in and positive/negative social interactions with available providers/clinic staff/systems of care. | 26 | 12 | 38 |

| Social norms and support | Perceptions of important other's attitudes/beliefs about HIV or medical care; social support or social costs for accessing care. | 50 | 18 | 68 |

| Behavioral skills | 95 (59%) | 32 (42%) | 127 (53.0%) | |

| Accessing ancillary services | Strategies or perceived ability/confidence to address unmet need (insurance/case management/transportation/locate care provider). | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| Addressing practical barriers | Strategies or perceived ability/confidence to attend HIV care appointments within the recommended intervals. | 17 | 5 | 22 |

| Daily hassles/comorbidities | Strategies or perceived ability/confidence to negotiate care in the context of daily hassles (work/child care) or comorbidities. | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| Planning/reminder strategies | Strategies or perceived ability/confidence to manage HIV care-related time commitments (scheduling/planning/long wait times). | 24 | 9 | 33 |

| Obtaining social support | Strategies or perceived ability/confidence to obtain support from important others (family/friends/service agency staff) for care. | 39 | 1 | 40 |

| sIMB contextual factors | 44 (27%) | 40 (52%) | 84 (35.0%) | |

| Affective factors | Positive or negative feelings about living with HIV including acceptance or denial of diagnosis, desire/no desire to live as HIV positive, HIV stigma. | 40 | 27 | 67 |

| Socio-cultural factors | Co-occurring experiences with acute substance use and mental health diagnosis (e.g., depression, anxiety), resource/housing instability. | 4 | 13 | 17 |

Once coded, applicable text segments were selected for a mixed-methods analytic approach30 to test the relative fit of participants' self-reflected experiences of retention in HIV care to the sIMB model. Both content analysis (deductive approach) and emergent theme identification (inductive approach) were utilized. Content coding was used to characterize facilitators and barriers to retention, assessing the degree to which the sIMB theoretical determinants occurred within participants' discourse related to retention in HIV care. This analysis was conducted on 239 text segments coded as a facilitator or barrier to retention in care. Emergent theme identification was employed to obtain important facilitators and barriers of retention in care in the target population that might not have been currently well accounted for in the sIMB model, or that extended beyond the model's concepts. The body of text analyzed in this approach (310 text segments) was broadened to include experiences of unstable retention in HIV care (i.e., text segments coded as facilitators or barriers of falling out of or re-engaging in routine HIV care) previously identified in the literature as influencing the process of self-sustained retention in care.18,21 Once selected, segments were unlinked from all codes (including sIMB-based codes) prior to the emergent theme identification analysis.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participant characteristics were similar to the patient population seen by the community clinic and outreach providers in terms of race/ethnicity (65% Latino, 35% black/African- American) and lower socioeconomic status (SES) characteristics (i.e., 80% reported an annual family income ≤$5,000–$10,000, 80% were currently on disability or sick leave, 50% having some high school education or less). Average age at time of interview was 49 years. Participants were predominantly male (60%), heterosexual (80%), and reported acquiring HIV via heterosexual intercourse (60%). The sample was relatively “experienced” in terms of HIV care and treatment histories, with three-fourths of participants (75%) reporting they had been in HIV care for ≥10 years. At time of interview most participants (80%) reported currently attending their HIV primary care visits within the recommended intervals for these clinical care sites (i.e., visits ≥once every 2–3 months); however, 30% of the total sample reported experiencing a significant gap in care of ≥6 months in the past 2 years (25% within the past year).

Qualitative test of the sIMB model of retention in HIV care

Content coding

Across participant discourse related to facilitators or barriers to retention in HIV care (239 text segments), sIMB-model based codes characterized all but 17 (7.1%) text segments involving facilitators and barriers to retention in HIV care (see Table 1); with information, motivation, behavioral skills content and contextual factors represented in 18.4%, 92.5%, 53.0%, and 35.0% of the text segments, respectively.

Emergent theme identification

An iterative review of participant discourse on facilitators or barriers to retention in HIV care, falling out of or re-engaging in routine care (310 text segments with all codes removed), identified nine key emergent themes for sustained retention in HIV care (see Table 2). Thematic content important to the process of sustaining retention in HIV care for the study population was explicated below each theme, then evaluated by two raters for fit with the core constructs of the sIMB model of retention in HIV care (see second column of Table 2). Overall, there was considerable convergence between the emergent themes inductively identified and the a priori assumptions of the sIMB model (highlighted in column 2). Very few elements identified as important to retention did not directly align with the core IMB constructs. Such elements reflected structural or systems-level barriers (i.e., transportation, clinic wait times) and facilitators (e.g., clinic-based services employed to reduce structural barriers to care). Although these structural components are not specified in the sIMB model per se, the model as proposed by Amico22 identifies motivation and behavioral skills to attend care in the context of such structural barriers as relevant to patients' retention in care.

Table 2.

Emergent Themes of Facilitators and Barriers Influencing Sustained Retention in HIV Care

| Themes facilitating or impeding retention in HIV care | sIMB model convergence |

|---|---|

| 1. Positive vs. negative adjustment and coping to living with HIV | |

| • Adjusting to life with HIV, moving toward acceptance of diagnosis, incorporating HIV into existing health beliefs. | Information |

| • Behavioral/mental disengagement (substance use, depression, indifference, avoidance of care) in response to HIV diagnosis. | Motivation |

| • Effective/ineffective regulation of affect (isolation, HIV stigma, frustration, anger) related to one's diagnosis or obtaining HIV care. | Behavioral skills |

| 2. Empowered vs. negative/limiting heuristics of self-care | |

| • Personalized view of self-care as “one's responsibility to self,” “care must always be your #1 priority.” | Information |

| • Global view of self-care as an “all or nothing behavior,” if one component of self-care lapses (e.g., medication adherence, appointment attendance, refraining from substance use, resisting depression), then there is no reason to engage in or re-engage in any of the components). | Motivation |

| 3. High vs. low perceived benefits of routine HIV care attendance | |

| • Dual role of perceived vulnerability: attending care to ensure good health vs. attending care to address acute health concerns. | Information |

| • Routine HIV care facilitates access to HIV medication, treatment for comorbid health conditions, new HIV treatment opportunities. | Motivation |

| • Routine HIV care is pointless if one is not engaging in global self-care behaviors (e.g., not adhering to HIV medications or HIV care appointments, using drugs, not prioritizing one's health above other needs, or not loving one's self enough). | Behavioral skills |

| 4. Positive vs. negative social interactions with providers, clinic staff, system of care | |

| • Providers viewed as a source of support for HIV and other life issues (discuss and feel listened to, have point of view respected). | Motivation |

| • Negative reactions/attitudes of providers (e.g., belittling/disregarding treatment concerns, not providing type of care/assistance patient perceives as relevant) and clinic staff (e.g., having a bad attitude, acting like it is just a job and not about the patients). | Structural factors |

| • Perceive system of care as responsive to one's needs (able to accommodate personal issues) vs. the system of care as a structural barrier to meeting one's needs (problems accessing transportation vouchers/clinic resources, long or excessive wait times). | |

| 5. Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and clinic-based strategies to attend HIV care | |

| • Self-directed use of scheduling/reminder strategies (e.g., calendar, planner, visible notes), perceived ability to access alternative HIV care sites when travel to clinic is impeded by physical impairments (i.e., difficulty walking) or extensive travel time is too burdensome. | Behavioral skills Structural factors |

| • Social-directed strategies include accessing case management or support from important others to help attend to scheduling conflicts, facilitate appointment reminders, or accompany one to an appointment for support or to assist with various tasks. | |

| • Clinic-based strategies to reduce structural barriers to care (e.g., consistency of provider, same-day appointments, shorter wait times, centralized care, clearly defined channels to address unmet needs, provision of transportation vouchers and nutritional supplements). | |

| 6. Prioritization or choice of competing priorities over HIV care attendance | |

| • Choosing or having to prioritize competing priorities instead of HIV care appointments often related to family commitments (e.g., children/partners sick, hospitalized, or incarcerated), time conflicts (e.g., work, other appointments, drug treatment), or personal comfort (e.g., sleep, relaxing, pain, wanting to avoid inclement weather, obtaining drugs). | Motivation Behavioral skills |

| 7. HIV-related memory/cognitive and physical impairments on HIV care attendance | |

| • Misjudgment of time elapsed since last appointment, habituation to reminders/prompts. | Motivation |

| • Long-term effects of living with HIV or treatment side effects on organic cognitive/memory and physical impairments (e.g., pain, “feeling the HIV,” “HIV ages you/tires you out”). | Behavioral skills |

| 8. Expressed desire or perceived investment in longevity | |

| • Expressed desire to live, ensure more time with important others, perceived need to be healthy to care for important others. | Motivation |

| • Enhanced commitment to regular HIV care by observing the health costs/benefits associated with the adoption/non-adoption of HIV care/treatment for other PLWH (living or deceased). | |

| 9. Perceived and associated consequences of substance use | |

| • Drug use or treatment (i.e., methadone) can mask need for HIV care (e.g., physical pain, symptoms). | Information |

| • Internalized stigma related to substance use acts as a barrier to care attendance (e.g., self-shame, anticipated judgment from providers), often accompanied by views that HIV care as incompatible with substance use. | Motivation |

| • Structural barriers to HIV care encountered as a consequence of active substance use (e.g., homeless, incarceration, running the street). | Structural factors |

Explicating critical sIMB model content for an inner-city sample of PLWH

A concise overview of retention-relevant content identified across both sets of analysis (see Tables 1 and 2) as reflecting the sIMB model's situated IMB constructs, is presented in aggregate below under their respective IMB headings. Within each heading, qualitative examples are provided to illustrate findings across participants' experiences of retention in HIV care. Affective (i.e., acceptance of diagnosis or disease stigma) and socio-cultural (i.e., comorbid mental health or substance use issues, norms for engaging in medical care) contextual factors, proposed by the sIMB model to be important in shaping the content of the model's constructs, are integrated within the respective IMB constructs.

Information

Retention-relevant information (or misinformation) reflected knowledge of HIV disease and its impact on physical and emotional health outcomes, as well as knowledge of the process, benefits, and costs associated with HIV treatments. For example, one participant explained his/her awareness of HIV's effect on immune functioning and the purpose of medical evaluation as

If I'm not feeling well, then I would come faster to see the doctor ‘cause…we're [PLWH] open to any disease at this point.

Other information used by participants as reasons to routinely monitor their health were identified, including information on the role of HIV medication and the purpose of treatment monitoring, such as

some medications don't work for you…that's why you got to tell [the doctor] what's going on with your medication…that's why you have to keep seeing the doctor.

Knowledge of medical treatment and monitoring for comorbid chronic conditions common in the patient population similarly facilitated retention in participants who were informed about the relationship between their HIV and comorbid condition(s). As one woman stated

I see my HIV doctor every month, because I got diabetes that's not well controlled, and with the virus together, it's not real good.

Accurate contextual knowledge of ways active substance use can “cause the virus to come out more” or “mask symptoms” of HIV in need of medical attention also emerged as an important facilitator of retention in this population.

Accurate/inaccurate cognitive heuristics guiding participants' HIV care decisions reflected health beliefs specific to HIV, such as that regular monitoring is important because one's viral load or CD4 count can “change quickly”. As part of the adjustment to living with and maintaining HIV care, participants further identified the need for PLWH to relearn certain health beliefs as a person now living with HIV (e.g., learning that one's perceptions, or how one feels is no longer a good “barometer” of one's internal health). However, most heuristics used to indicate the need for medical monitoring integrated broader, less accurate, health beliefs reflecting general indicators of subjective health, such as presence or absence of acute physical symptoms, weight loss/gain, and quality of nutrition. For example:

I base my whole treatment on if I feel like there's something [physically] wrong with me…if I'm not feeling nothing I'm not gonna go see the doctor, but if something's wrong, like recently with my joints…I'm gonna go.

Another inaccurate heuristic identified as influencing participants' withdrawal from routine HIV care stemmed from a perception that HIV care is an “all or nothing process” that is, that one is either doing everything they can to treat the HIV or there is no point to engaging in any HIV or self-care behaviors. This perception was typically reflected in the presence of participants' engagement in suboptimal self-care behaviors (e.g., missing medical appointments, medication nonadherence, problems coping with acute mental illness, or active substance use), and implied that by enacting such behaviors one was not fully invested in their HIV care or health, and often resulted in HIV treatment decisions to withdraw from care.

I think it's what your involved in…how you carry yourself…that makes a person either go or don't go to their appointments, like me last year I wasn't taking my meds, I was into selling them [HIV medications] and getting depressed, just not caring if I lived or died…so it's [HIV care] pointless.

Motivation

Retention-relevant personal attitudes and beliefs toward having HIV and accessing HIV care fell into two distinct factors, those related to ways that HIV itself impacts the process of accessing care versus those related to adjustment and coping with being HIV positive. Cognitive/memory and physical impairments resulting from HIV disease or long-term treatment was identified as affecting participants' attitudes and beliefs about maintaining HIV care. One participant explained the importance of seeing her doctor when scheduled, even if she “looked fine” to her family as

[With HIV] your body feels fine, 100%, now…but tomorrow you feel like crap…emotionally or mentally…You know, like tired, aches and pains here and there, and it varies every day.

Attitudes related to living with HIV primarily reflected contextual affective factors in which participants reflected on ways their feelings about being HIV positive influenced their decision to access or not access care. For example:

in the beginning…you looked at it as a death sentence… [now HIV care is] something I have to do to stay alive…I want to live today, so that's…the best incentive [to come in].

or

Nobody likes going to the doctors, but on top of that I have to go because [I'm positive]…I guess that's where the depression kicks in.

Such feelings reflected experiences with effective/ineffective regulation of affect when reminded of one's HIV diagnosis, and HIV-related stigma concerns. Additional contextual factors influencing retention in HIV care were related to stigma associated with comorbidities such as substance use and depression. Such experiences (e.g., shame, anticipated judgment from providers, viewing care attendance as incompatible with drug use), when identified by participants, significantly impacted their attitudes toward engaging in care. In particular, internalized stigma emerged as a critical barrier to care in this population.

It wouldn't have been difficult [to see the doctor]…I think I just purposely chose not to see them…I was [drinking heavily]. I would come in to see the doctor, and I would like walk around and leave [before seeing them]! I was doing wrong…it wasn't something that they did; just the choice I made.

Themes surrounding perceived vulnerability to the benefits and consequences of accessing HIV care revealed a range of attitudes and beliefs. The benefits of routine HIV care were perceived as lower for PLWH who were asymptomatic, not receiving or adherent to HIV medications, or otherwise engaged in poor self-care behaviors (e.g., using drugs, selling their medications). The benefits of routine care were perceived as greater for those who believed it helped them to stay informed of new treatment opportunities, or provided treatment opportunities that enhanced their quality of life or ensured they had a longer life span to spend with important others. Additionally, perceived vulnerability to HIV disease reflected both a reactive and proactive influence on participants' reasons for accessing care. For example, coming to care out of fear something bad is happening to one's health, such as

If I see myself getting a little skinny or losing weight, I'm flying to the doctor, to find out if I'm losing weight because of the HIV!

Others identified a more tangible value in attending care regularly and receiving feedback on their health status, such as

I always get a good report when I come in…even when I get a bad report, I'll come back again, “No you have to give me a good report Mamí [referring to the doctor], what's going on here?” Just knowing…[helps me] do what I'm supposed to.

Attitudes and beliefs about accessing care in the context of competing priorities such as daily hassles (e.g., family commitments, conflicting appointment times, desire for personal/leisure activities) and comorbid conditions (e.g., substance use or depression and related treatment demands) were commonly reported as barriers to retention in care. For example:

I don't miss my appointments, but I get here late and can't be seen till the next day or the next week… because your whole life revolves around going to get this methadone.

In such cases, participants expressed frustration with the competing priorities and perceived added burden of treatment for other conditions. Nevertheless, such frustrations did not typically diminish the belief that their HIV care appointments were equally important. Participants also discussed the processes by which they developed an understanding of attending care in relation to such competing priorities, such as

I have the choice to come or not come [to my appointments] when I don't, I [have to effectively] deal with whatever is going on around me, with me, or inside me…it's just a matter of responsibility, [you] find a way [to make it in].

The role of trust in the patient–provider relationship and in the system of care facilitated retention in HIV care. For example, participants perceived actions at the clinic level (e.g., seeing the same provider each visit, same-day appointments, centralized care, appointment reminder calls), as being personally responsive to their needs, facilitating more positive attitudes toward HIV care. One participant, with debilitating anxiety, described this perceived responsiveness as facilitating her perception that she remains connected to her HIV care even when she has not been adherent to her medical appointments as

I could miss three visits in nine months because of my anxiety… walk into the clinic whenever I wanted to, because they know of my anxiety, I'm never denied…they'll get [any available doctor] when they hear my name, “Oh, shit, she's here. Let's get her. I've been blessed with them doctors.

Favorable attitudes also emerged when providers were viewed as a reliable source of support for coping with depression, substance use, or daily hassles. Such perceptions were highlighted by beliefs about the importance of being "open" with providers, particularly when one is not following their care/treatment recommendations or exhibiting poor self-care.

[My provider and I] had a good talk last month…I told her that I had been depressed and that I had started getting high. I was really glad I could be honest with her…because she advised me I can go to therapy…so I can have someone to talk with when I get like that.

However, retention in care appeared more strained in participant discourse reflecting difficult interpersonal interactions with clinic staff or providers, such as when clinic staff is perceived as having an “attitude” or when patients felt providers belittled or disregarded concerns patients had about their HIV medications or treatments.

Relevant to retention in care, social norms and support reflected specific cultural beliefs about HIV and accessing medical care, such as

In my culture, in my family, you wait till the very last minute to go to the hospital… I guess that's another reason you can easily put it off [routine HIV care].

Descriptive norms of other PLWH in the community misusing/taking advantage of the system of care and available services (e.g., accessing services without following through on their treatment plan, or selling one's medications), were observed. Several participants disclosed having a high proportion of HIV-positive others in one's or ones partner's immediate family. Likewise, normative beliefs reflecting perceived consequences of poor retention in care reflected a substantial amount of loss of HIV-positive others, especially before the availability of antiretroviral medications.

My brother died from HIV and quite a few relatives passed from it. Wasn't no cure then…well ain't no cure, wasn't no medicine at all at that time. But right now…there is some medicine to help…and being that I had a lot of family members pass from it…that's what makes me come here.

Multiple sources of perceived social support for attending HIV care appointments were identified, including emotional and instrumental support from important others, HIV care providers, and the presence of external support systems (e.g., case management, mental health treatment). An important contextual area where the presence or absence of perceived support appeared critical to retention was at the intersection of stigma related to drug use or mental illness, and different sources of social support such as families or HIV care providers. These intersections demonstrated unique consequences with respect to retention-related social motivation, as seen in the following quotation:

I've been at it [depression] for more than 35 years and there [was] times I…choose to pick up [illicit drugs]. Whereas now I know I can come tell [my doctor] before I pick up…so I don't have to deal with it all myself…because that's something I wouldn't tell my family – I'm depressed I feel like getting high or…I got high.

Behavioral skills

System navigation skills to identify appropriate HIV care providers (including locating alternative HIV care providers when travel to clinic is impeded by extensive travel time or other physical impairments), and access to ancillary services (e.g., case management, AIDS drug assistance programs, or treatment for comorbid conditions) to address unmet needs facilitated participants' retention. One participant with self-disclosed HIV-related cognitive impairments describes this process as

Because I be forgetting a lot of things…I got outside help. I joined a program for people that have HIV with other problems. The counselors there, I go see them, or them come see me and they remind me of my appointments and things that I have to do…that's what helps me get in here [HIV care].

Participant discourse on addressing practical barriers to attend one's routine HIV care visits as scheduled almost exclusively reflected a strong perceived ability that any changes to one's benefits or competing demands could be managed effectively. However, participants varied in the degree to which they effectively used functional skills to remember and attend their appointments, especially when faced with other priorities. Participants often misjudged the amount of time that had passed since their last appointment or cited not using or forgetting to attend to any personal planning/reminder strategies (e.g., use of daily planner, calendar, visible notes) as barriers to retention. Whereas such strategies facilitated retention in care when participants identified a system by which they routinely used the strategies they has put in place. For example:

I got little post-it things put all over…that helps. If I remember to write it right there and then, I'll put it on my mirror. I don't have no mirror cause I have paper all over it, so I can try to remember.

Competing demands such as daily hassles/comorbidities (e.g., mental health, substance use) most often reflected perceived and objective abilities to coordinate multiple appointments for one's self or family, including therapy and methadone treatment. Abilities to obtain social support for coordinating HIV care attendance in the context of competing demands (e.g., coordinating family/household responsibilities, receiving reminders or support from family/partners to attend appointments) and coping with comorbidities such as anxiety or depression related to accessing HIV care, facilitated retention. For example:

Sometimes you have two appointments at the same time; I got my wife…to meet with the electrician so I could make my appointment…It's good to have somebody, she covered me…helped me.

Similarly, specific skills for prioritizing HIV care in relation to sIMB contextual factors emerged from participants' discourse. For example, when co-occurring substance use (e.g., recognizing the role of substance use or depression in masking personal motivation, as well as physical signs/symptoms indicating a need for medical care) is implicated in one's HIV care attendance. Managing affect related to one's HIV status (e.g., skills to identify and address behavioral and mental disengagement and regulate emotional affect) emerged as an additional retention-relevant skill set. One participant, still struggling with his HIV status, reflected on this, saying

Feeling that I have to [see the doctor]…I get more depressed, I'll keep myself occupied to not think about [having HIV], make other things a priority instead of going to the doctors…when I should be going to the doctors.

Identifying appropriate sources of support for managing perceived or anticipated HIV and related stigmas (e.g., mental illness, drug use) from providers or important others, and to cope with one's HIV-diagnosis/prognosis and HIV-related cognitive or physical impairments also emerged as important skills for addressing contextual factors.

In sum, these findings aid in articulating the types of information, motivation, behavioral skills underlying participants' experiences with retention in care in an inner-city sample of marginalized PLWH accessing traditional or nontraditional HIV care services. These experiences strongly aligned with sIMB model of retention in care IMB constructs and contextual content (e.g., affect toward and acceptance of HIV status, socio-cultural-environmental factors) proposed by Amico,22 supporting the utility of a sIMB-based approach to retention in HIV care.

Discussion

An understanding of the dynamics of self-directed retention in HIV care is critical to promote the development, implementation, and evaluation of effective behavioral interventions that enhance sustained retention in HIV care. To date, limited theoretical efforts or in-depth research has focused on illuminating theses dynamics. The current research represents an important step in facilitating future intervention efforts by providing the first qualitative examination of a comprehensive model articulated to retention in HIV care, a situated Information, Motivation, Behavioral Skills model of Care Initiation and Maintenance for chronic conditions.22 This work supports the utility and validity of this theoretical model in explicating the behavioral factors underlying retention in HIV care in an inner-city population of PLWH. The consistency between the content identified in the situated application of the IMB model and data collected via participant discourse suggests this situated IMB-based approach offered a potentially valuable way of characterizing retention in HIV care in the current sample.

As articulated, the sIMB model of retention in HIV care provides a coherent organization of retention-relevant factors identified in the current study, and readily extends to individual correlates identified in previous work (e.g., knowledge of HIV treatment benefits,36 attitudes toward HIV providers,18,21,37,38 affect17,21,39 and skills17,21 to adjust to life with HIV, and skills to access support and address unmet needs40–42). Findings from the current study build upon the extant work, supporting the sIMB model's proposed integration of these individual elements and articulation of how they may work together to affect retention in care. Additional insights were gained on processes important to retention in HIV care for the current population, which included aspects of how patients integrate specific information, motivation, and behavioral skills into personal schemas guiding HIV care decisions, and how patients contextualized HIV care into a more global framework of self-care behaviors (e.g., nutrition, substance use, medication adherence).

Personal schemas guiding HIV care decisions

A number of informational factors (i.e., routine HIV care facilitates one's access to new treatment information, HIV medications, and treatments for comorbid chronic conditions; or knowledge that one's active substance use/methadone treatment can limit one's awareness of pain or other acute physical symptoms) were identified in participants' discourse as important in driving decisions to routinely attend HIV care. Schemas that reflected proactive attitudes (i.e., attending regular HIV care appointments is how one can achieve and maintain good health) were drawn from participants' personal motivation to ensure optimal health outcomes, longevity, and more time with important others, as well as observations of the health costs/benefits encountered by other PLWH who maintained (failed to maintain) routine HIV care. Identifying ways one's perceived ability (inability) to manage acute affect related to one's HIV diagnosis, or memory/cognitive and physical impairments resulting from the long-term effects of HIV and HIV treatments represented important behavioral skills that participants had integrated into their HIV care schemas for addressing barriers to retention in HIV care.

Global framework of self-care behaviors

Participants' decisions to engage or not engage in HIV care were often guided by an “all or nothing” global view of self-care behaviors (e.g., giving way to depression, substance use, frequently missing appointments, medication nonadherence, or failing to adhere to other treatment recommendations), meaning that if one aspect of self-care was poor, there is no reason to engage/re-engage in any other aspects of self-care. Consequences of this perspective in the current sample were profound, and impacted retention in HIV care on multiple levels. The root of this heuristic appeared to be a sense that practicing any of these behaviors demonstrated that one did not care about or love one's self enough to take responsibility for one's health, thus legitimizing one's withdrawal from all other of self-care behaviors including routine HIV care visits. Experiences of internalized stigma related to severe depression/substance use reflected ways participants' self-shaming led to the avoidance of HIV care and perceived limitation of available avenues of social support for maintaining care under these circumstances. Perceived or anticipated stigma/negative reactions from HIV care providers regarding one's engagement in any of these poor self-care behaviors similarly facilitated participants' avoidance of HIV care, limiting avenues of support from clinic providers/staff, and linkage to ancillary services that could address unmet needs related to these behaviors (e.g., therapy, harm reduction, medication adherence counseling). Additionally, participants' perceived or anticipated stigma from important others on these issues additionally limited avenues of support for addressing comorbidities or obtaining support to continue with one's HIV care in these circumstances. Conversely, participants who perceived that HIV care was possible, even in the presence of other poor self-care behaviors, almost unanimously described the critical role of established trust in their patient–provider relationships. Such discourse identified HIV care providers as a reliable source of support for coping with these challenges, and a sense that they did not “have to go it alone”.

The current study builds upon an emerging body of work aimed at identifying key factors influencing retention in HIV care8,9,11,15,19,21 that may be amenable to targeted intervention and behavior change.43,44 Importantly, these findings demonstrate the utility of a theory-based approach to retention in HIV care in explicating important facilitators and barriers to retention in care, offering a vetted framework to systematically organize, identify and target these factors in future intervention efforts to enhance retention in HIV care. Although the present work on retention in HIV care was informed by, and importantly extends beyond, the extant work on care utilization across a diverse range of PLWH, there are some limitations to the generalizability and application of the results from the current model evaluation.

Reliance on retrospective recall of experiences with HIV care and the fact the trained coders were not blind to situated IMB model hypotheses are limitations in the present research. Further, the current work cannot speak to any relative contributions of “situating” specific contextual factors within model constructs. Traditional IMB approaches with a given cohort or behavior employ elicitation work (e.g., focus groups, brief surveys, key informant interviews) to illuminate contextual and other critical elements in the absence of any a priori assertions regarding the role of contextual factors. Supportive results for this situated application may additionally, in part or in whole, generalize to more traditional (non-situated) IMB model methods that could have been used to articulate the IMB model to retention in HIV care. Regardless, these results are valuable for the development of interventions leveraging an IMB-model focus, which was one of the main objectives of this research.

In line with past work in applying the IMB model across diverse populations,24 it is anticipated that work with a situated IMB model of retention in HIV care across populations of PLWH will continue to support the centrality of the core information, motivation, behavioral skills constructs.22,24,45 Consistent with past work on the IMB model,27,46 the specific content associated with each of these constructs, which is most relevant for structural model tests, intervention development, and testing, should be tailored to address the interrelationships between the core determinants of HIV care for a given population. As in previous research,7 approximately one-third of the sample had had a significant gap in HV care of ≥6 months in the past 2 years, 25% of which reported such a gap in the past 12 months. The ability to identify PLWH at risk for falling out of routine HIV care before they do so, or to help re-engage those returning from a prolonged absence, is critical to enhancing the health and care of PLWH at risk of suboptimal health outcomes. Results of the first qualitative test of the sIMB model of retention in HIV care support the model's ability to specify important theoretical (i.e., IMB skills) and contextual (i.e., affect toward and acceptance of one's diagnosis, mental health, substance use) factors involved in this behavioral process in an inner-city sample of PLWH. At present, a formal test of the model's proposed structural relations and ability to predict retention in HIV care among the inner-city clinic population is underway. This program of work alongside rigorous evaluations of model-based intervention approaches, using randomized control designs, are needed before any conclusions regarding the model's structure and function can be inferred. Notwithstanding, findings of the current study are pertinent to inform current “test and treat” efforts.10 Specifically, this work is independently valuable in moving the known correlates of retention in HIV care into a viable comprehensive model likely to inform and easily translate future intervention efforts relevant to individual and public health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants and medical outreach and clinic staff for their contributions to the project. The project described was supported by Award Number F31MH093264 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and by NIH R25DA023021 and the Center for AIDS Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center (NIH AI-51519). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Aberg JA. Kaplan JE. Libman H, et al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus: 2009 update by the HIV medicine association of the infectious diseases society of america. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:651–681. doi: 10.1086/605292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg MB. Safren SA. Mimiaga MJ. Grasso C. Boswell S. Mayer KH. Nonadherence to medical appointments is associated with increased plasma HIV RNA and decreased CD4 cell counts in a community-based HIV primary care clinic. AIDS Care. 2005;17:902–907. doi: 10.1080/09540120500101658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giordano T. Gifford A. White J. Cliton A., et al. Clinton, et al. Retention in care: A challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1493–1499. doi: 10.1086/516778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mugavero MJ. Lin HY. Willig JH, et al. Missed visits and mortality among patients establishing initial outpatient HIV treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:248–256. doi: 10.1086/595705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugavero MJ. Lin HY. Allison JJ, et al. Racial disparities in HIV virologic failure: Do missed visits matter? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5c37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park WB. Choe PG. Kim SH, et al. One-year adherence to clinic visits after highly active antiretroviral therapy: A predictor of clinical progress in HIV patients. J Intern Med. 2007;261:268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mugavero MJ. Improving engagement in HIV care: What can we do? Top HIV Med. 2008;16:156–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks G. Gardner LI. Craw J. Crepaz N. Entry and retention in medical care among HIV–diagnosed persons: A meta-analysis. AIDS. 2010;24:2665–2678. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f4b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horstmann E. Brown J. Islam F. Buck J. Agins BD. Retaining HIV-infected patients in care: Where are we? where do we go from here? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:752–761. doi: 10.1086/649933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer KH. Introduction: Linkage, engagement, and retention in HIV care: Essential for optimal individual-and community-level outcomes in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 2):S205–S207. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mugavero MJ. Norton WE. Saag MS. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: Piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 2):S238–S246. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheever LW. Engaging HIV-infected patients in care: Their lives depend on it. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1500–1502. doi: 10.1086/517534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mkanta WN. Uphold CR. Theoretical and methodological issues in conducting research related to health care utilization among individuals with HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:293–303. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uphold C. Mkanta W. Use of health care services among persons living with HIV infection: State of the science and future directions. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:473–485. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beer L. Fagan JL. Valverde E. Bertolli J. Health-related beliefs and decisions about accessing HIV medical care among HIV-infected persons who are not receiving care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:785–792. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kempf MC. McLeod J. Boehme AK, et al. A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators to retention-in-care among HIV-positive women in the rural southeastern United States: Implications for targeted interventions. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:515–520. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallinson KR. Relf MV. Dekker D. Dolan K. Darcy A. Ford A. Maintaining normalcy: A grounded theory of engaging in HIV-oriented primary medical care. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2005;28:265–277. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mallinson R. Rajabiun S. Coleman The provider role in client engagement in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:S77–s84. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moneyham L. McLeod J. Boehme A, et al. Perceived barriers to HIV care among HIV-infected women in the deep south. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21:467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nunn A. Cornwall A. Fu J. Bazerman L. Loewenthal H. Beckwith C. Linking HIV-positive jail inmates to treatment, care, and social services after release: Results from a qualitative assessment of the COMPASS program. J Urban Health. 2010;87:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9496-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajabiun S. Mallinson R. McCoy K, et al. 'Getting me back on track': The role of outreach interventions in engaging and retaining people living with HIV/AIDS in medical care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:S20–s29. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amico KR. A situated-information motivation behavioral skills model of care initiation and maintenance (sIMB-CIM): An IMB model based approach to understanding and intervening in engagement in care for chronic medical conditions. J Health Psychol. 2011;16:1071–1081. doi: 10.1177/1359105311398727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amico KR. Smith LR. Urso J, et al. The situated information motivation behavioral skills model of HIV care initiation and maintenance (sIMB-CIM): Preliminary support for characterizing gaps in HIV care. [Abstract 61557]; 5th International Conference on HIV Treatment Adherence; Miami Beach, Florida. May 22;; to May 25, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Amico KR. Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25:462–473. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher WA. Fisher JD. Harman J. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model: A general social psychological approach to understanding and promoting health behavior. In: Suls J, editor; Wallston K, editor. Social Psychological Foundations of Health. London; Blackwell Publishing: 2003. pp. 82–106. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher JD. Fisher WA. Shuper PA. The Information–Motivation–Behavioral skills model of HIV preventive behavior. In: Di Clemente RJ, editor; Crosby RA, editor; Kegler MC, editor. Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practices and Research. San Franscisco, CA: Jossey–Bass Publishers; 2009. pp. 21–63. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham CO. Sanchez JP. Heller DI. Sohler NL. Assessment of a medical outreach program to improve access to HIV care among marginalized individuals. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1758–1761. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mund PA. Heller D. Meissner P. Matthews DW. Hill M. Cunningham CO. Delivering care out of the box: The evolution of an HIV harm reduction medical program. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:944. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 4th. Oxford, UK: Altamira Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.SPSS Inc. SPSS version 17.0. Chicago, IL: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muhr T. Friese S. User's manual for ATLAS. ti 5.0. Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson B. Christensen LB. Educational Research: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Approaches. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleiss JL. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd. New York: John Wiley; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landis JR. Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brewer TH. Zhao W. Pereyra M, et al. Initiating HIV care: Attitudes and perceptions of HIV positive crack cocaine users. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:897–904. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bodenlos J. Grothe K. Whitehead D. Konkle–Parker D. Jones G. Brantley P. Attitudes toward health care providers and appointment attendance in HIV/AIDS patients. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sohler NL. Li X. Cunningham CO. Gender disparities in HIV health care utilization among the severely disadvantaged: Can we determine the reasons? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:775–783. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakken S. Holzemer WL. Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:189–197. doi: 10.1089/108729100317795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo W. MacGovern T. Bradford Association of ancillary services with primary care utilization and retention for patients with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2002;14:S45–S57. doi: 10.1080/0954012022014992049984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tobias C. Cunningham Cabral H, et al. Living with HIV but without medical care: Barriers to engagement. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:426–434. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rumptz M. Tobias C. Rajabiun S, et al. Factors associated with engaging socially marginalized HIV-positive persons in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:S30–S39. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hightow–Weidman LB. Smith JC. Valera E. Matthews DD. Lyons P. Keeping them in “STYLE”: Finding, linking, and retaining young HIV-positive black and latino men who have sex with men in care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:37–45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hightow–Weidman LB. Jones K. Wohl AR, et al. Early linkage and retention in care: Findings from the outreach, linkage, and retention in care initiative among young men of color who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:S31–S38. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher JD. Cornman DH. Osborn CY. Amico KR. Fisher WA. Friedland GA. Clinician-initiated HIV risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive persons: Formative research, acceptability, and fidelity of the options project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:S78–S87. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000140605.51640.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher JD. Amico KR. Fisher WA. Harman JJ. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of antiretroviral adherence and its applications. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s11904-008-0028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]