Abstract

The yeast, fungal and mammalian prions determine heritable and infectious traits that are encoded in alternative conformations of proteins. They cause lethal sporadic, familial and infectious neurodegenerative conditions in man, including Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS), kuru, sporadic fatal insomnia (SFI) and likely variable protease-sensitive prionopathy (VPSPr). The most prevalent of human prion diseases is sporadic (s)CJD. Recent advances in amplification and detection of prions led to considerable optimism that early and possibly preclinical diagnosis and therapy might become a reality. Although several drugs have already been tested in small numbers of sCJD patients, there is no clear evidence of any agent’s efficacy. Therefore, it remains crucial to determine the full spectrum of sCJD prion strains and the conformational features in the pathogenic human prion protein governing replication of sCJD prions. Research in this direction is essential for the rational development of diagnostic as well as therapeutic strategies. Moreover, there is growing recognition that fundamental processes involved in human prion propagation – intercellular induction of protein misfolding and seeded aggregation of misfolded host proteins – are of far wider significance. This insight leads to new avenues of research in the ever-widening spectrum of age-related human neurodegenerative diseases that are caused by protein misfolding and that pose a major challenge for healthcare.

Keywords: conformation of human prion protein, diagnosis, human prion strains, neurodegeneration, neuropathologic classification, sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD)

Introduction

Prion diseases,1 originally called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies,2 are invariably fatal neurodegenerative diseases that affect humans and animals. The key characteristics of human spongiform encephalopathies are (1) heterogeneity of the clinical and pathologic phenotype,3-5 (2) a single pathologic process, which may present as a sporadic, genetic, or infectious illness,6 and (3) the age dependence of genetic as well as sporadic forms: the annual peak incidence is 3–6 cases per million people between 65 and 79 years of age.6,7 Despite their rarity, human prion diseases have gained considerable importance because their unique etiology and pathogenesis challenged basic principles of biology. Furthermore, prion diseases can be transmitted between humans as well as from animals to humans by an agent that is highly resistant to inactivation and which thus poses novel problems to disease control and public health. Finally, because of the marked heterogeneity of their clinical phenotype, prion diseases are difficult to differentiate from other age-related brain neurodegenerations, a feature that has prompted the establishment of specialized prion disease surveillance centers worldwide. Human prion diseases also include inherited forms as well as forms acquired by infection (Table 1). However, this review focuses on the molecular aspects of the pathogenesis of sporadic forms.

Table 1. Etiologic classification of human prion diseases.

| Etiology | Mechanism | Disease |

|---|---|---|

| |

|

|

|

Sporadic |

Somatic mutation or spontaneous conversion of PrPC into PrPSc ? |

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

| |

Somatic mutation or spontaneous conversion of PrPC into PrPSc ? |

Sporadic fatal insomnia |

| |

Unknown |

Variable protease-sensitive prionopathy |

| |

|

|

|

Hereditary |

Germ-line mutations in the PRNP gene |

Familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

| |

Germ-line mutations in the PRNP gene |

Fatal familial insomnia |

| |

Germ-line mutations in the PRNP gene |

Gerstmann–Sträussler-Scheinker disease |

| |

|

|

|

Acquired |

Infection through ritualistic cannibalism |

Kuru |

| |

Zoonotic infection with bovine prions |

Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

| Infection from prion-contaminated human growth hormone, dura mater grafts, etc. | Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

From slow virus to the prion concept

Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) is the most common form of human spongiform encephalopathy, accounting for ~85% of all human prion disease.8 The term “Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease” (CJD) was introduced by Alfons Maria Jakob in 1921, who referred to a previous case described by Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt in 1920.9,10 These original cases were clinically heterogeneous, and neuropathologic review of the historical material with modern tools provided confirmation of the diagnosis of CJD in only two of the original five cases.11 Over the next two decades, the clinicopathological classification of CJD remained uncertain and for example Wilson concluded that CJD is a “dumping ground for several rare cases of presenile dementia”12. Although monograph by Kirschbaum13 listed the clinical and pathologic characteristics of 150 cases diagnosed before 1965, it included also cases such as Creutzfeldt’s original case, which would not fulfill criteria for the diagnosis of CJD today. Importantly, in the 1960s, Nevin and Jones described the typical clinical symptoms, electroencephalogram (EEG), and neuropathologic changes, including spongiform change, which together are now recognized as the paradigm features of sporadic CJD.14 Subsequently, new sporadic forms of the spongiform encephalopathies with unique phenotypic features were described; specifically, sporadic fatal insomnia (SFI) in 1997,15,16 and the latest likely new candidate, variable protease-sensitive prionopathy (VPSPr) in 2008.17

Controversy concerning the cause of human spongiform encephalopathies has polarized the scientific community for decades. The 1950s saw considerable interest in an epidemic of a neurodegenerative disease, kuru, characterized principally by a progressive cerebellar ataxia, among the Fore people of the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea.18,19 Fieldwork by Carleton Gajdusek and Vincent Zigas suggested that kuru was transmitted during cannibalistic feasts.20 Importantly, in 1959 Hadlow pointed out the similarities between kuru and scrapie of sheep at the neuropathologic and clinical levels and suggested that human diseases might also be transmissible.21 Subsequent transmission of kuru (in 1966) and then CJD (in 1968) by intracerebral inoculation of brain homogenates into chimpanzees, work which was conducted by Gajdusek, Gibbs, and colleagues, was a landmark discovery which led to the concept of the “transmissible spongiform encephalopathies”22,23. The transmission of Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease (GSS) followed in 198124 and fatal familial insomnia (FFI) in 1995.25 Interestingly, Jakob, suspecting in his original observations that the condition might be transmissible, inoculated rabbits experimentally, in an attempt to demonstrate this in the 1920s.26 However, thanks to the important role of serendipity in science, his experiment was unsuccessful and we know now that rabbits are uniquely resistant to prion infections.27

The transmission of CJD and of kuru allowed refinement of the diagnostic pathologic criteria for human spongiform encephalopathy and led to the conclusion that all the human conditions share common histopathologic features: spongiform vacuolation (affecting any part of the cerebral gray matter), neuronal loss, and astrocytic proliferation that may be accompanied by amyloid plaques.28-31 On analogy with scrapie in sheep, it was assumed that the causative agent must be some type of atypical “slow virus,” the term Sigurdsson coined in 1954 for scrapie infection.2,32 Regrettably, despite extensive efforts in Europe and the US, no non-host DNA or RNA could be found, and a growing body of data pointed to a causative agent having unique characteristics.33,34 Most researchers today accept the model according to which the infectious pathogen responsible for human prion diseases is an abnormal protein, designated PrPSc 1.

The discovery that proteins could be infectious represented a new paradigm of molecular biology and medicine. Although originally deemed heretical, this protein-only model is now supported by a wealth of biochemical, genetic and animal studies.6,35-38 Moreover, the concept of prion diseases has important implications for other neurodegenerative disorders. Recent studies with Amyloid β, tau, α-synuclein, huntingtin, and superoxide dismutase 1 suggest that molecular and cellular mechanims that were first discovered in studies of prions are involved in the pathogenesis of other neurodegenerative disorders associated with the accumulation of misfolded proteins, including Parkinsonism, Huntington disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Alzheimer disease.39-43

Pathogenetic mechanisms of human sporadic prion diseases

The basic event shared by all three forms of prion diseases – sporadic, inherited and acquired by infection – is a change in conformation of the normal or cellular PrP (PrPC) which is converted into a pathogenic PrP isoform commonly identified as PrPSc for prototypic scrapie (Sc) PrP.1 Human PrPC is encoded by the PrP gene (PRNP) on chromosome 20 and expressed at different levels in most mammalian cells. It comprises 209 amino acids (23–231), two sites of N-linked glycosylation, a disulfide bond and a glycolipid anchor.44-49 The variable degree of glycosylation is responsible for the presence of di-, mono- and un-glycosylated forms of PrPC. Because of the glycolipid anchor, most of the PrPC is extracellularly linked in specialized cholesterol-rich domains (caveoli) of the cell plasma membrane.48,50 In normal conformation, human PrPC comprises a C-terminal globular domain (involving residues 127–231), which consists of three α-helices and two short β-sheets.51 In contrast, the N-terminus is unstructured.51

The PrPSc, in contrast, is pathogenic, infectious and displays different biophysical features, forming insoluble aggregates of different sizes with predominantly β-sheet secondary structure; the C-terminal region is relatively resistant to proteolytic degradation.52-54 The conformational transition that underlies these pronounced changes is believed to involve refolding of the C-terminal region whereby the α-helical structures of PrPC are replaced by β-sheet to different extents and with variable patterns.55 Although insolubility and protease resistance were the original defining features of PrPSc, the finding of protease-sensitive small oligomers of pathogenic PrPSc 56, 57 significantly broadened the spectrum of pathogenic conformers.

Although some authors believe that the toxicity in prion disease can be explained as a loss of function of PrPC due to the conformational transformation,58 others argue that a gain of toxic function is more likely.59,60 Nevertheless, there is general agreement that PrPC serves as a substrate for conversion to PrPSc and as a major receptor for toxic effects of PrPSc. Thus the neuroprotective function physiologically provided by PrPC could be lost following its conversion to PrPSc. The prevailing presence of PrPSc on neuronal plasma membrane also at the synapse might explain the widespread spongiform degeneration, which can be viewed as intracellular edema. All these changes are pathognomonic of sCJD. Apoptosis and oxidative stress are reported to occur when PrPSc aggregates form at the cell surface and may well contribute to the neuronal cell loss that is prominent in prion diseases of long duration and in prion diseases like SFI, which manifest no or minimal spongiosis as well as severe neuronal loss.61 Astrogliosis, a common reaction to injury, is considered a secondary response.

The origin and phenotypic heterogeneity of sCJD

Several explanations have been proposed for the etiology of sporadic prion diseases. These include spontaneous somatic mutations in the PRNP gene or rare stochastic conformational changes in the structure of PrPC 62. These explanations presuppose that the mutant PrPSc would have to be capable of recruiting wild-type PrPC; however, this process which might occur with some mutations or conformations but is unlikely with others.63 According to a second explanation, low amounts of PrPSc-like isoforms are normally present in brain, and possibly bound to other proteins such as heat shock proteins, however, this protective mechanism fails with aging.64,65 Finally, it has been suggested that at least some cases of apparent sCJD result from covert, low-level exposure to a “common external factor”66.

With more cases investigated after the original reports by Jakob, it became clear that the clinical as well as histopathologic features of sCJD are remarkably diverse, perhaps making the human prion diseases the most heterogeneous of all neurodegenerative disease. On the basis of predominant clinical and pathologic features, the following phenotypic subtypes of sCJD were proposed in the 1980s: 1) myoclonic or cortico-striatal-spinal, 2) amaurotic or Heidenhain, 3) classical or diffuse, 4) thalamic, 5) ataxic or cerebellar, and 6) amyotrophic.67-69 Researchers today generally agree that the genotype at codon 129 of the chromosomal gene PRNP, and to some degree the phenotypes of these diseases, underlie susceptibility to prion diseases.5 Additionally, many lines of evidence from experiments with laboratory prion strains support the view that the phenotype of sCJD—its distinctive incubation time, clinical features, and brain pathology—is enciphered in the strain-specific conformation of PrPSc 56,70–73. However, in contrast to the experiments with laboratory rodent prion strains, in which the digestion of brain PrPSc with proteolytic enzyme proteinase K (PK) consistently results in a single protease-resistant domain with mass ~19 kDa, the outcome in sCJD is more complex. Distinctive glycosylation patterns and up to four PK-resistant fragments of the pathogenic prion protein (rPrPSc) found in sCJD brains are easily distinguishable on western blot (WB).5,71,74-77

The WB findings together with human PRNP gene polymorphism led Parchi, Gambetti, and colleagues to posit a clinicopathological classification of sCJD into five or six subtypes; notably, the WB characteristics of PrPSc breed true upon transmission to susceptible transgenic mice and Guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus).5,71,74,78 An alternative classification of the PrPSc types and their pairing with CJD phenotypes has been proposed by Collinge and collaborators.37,75,76,79 This classification differs from the previous one in two major aspects: first, it recognizes three (not two) PrPSc electrophoretic mobilities and second, it also identifies PrPSc isoforms with different ratios of the three PrP glycoforms.37 Although the disease phenotypes of patients with sCJD are remarkably heterogeneous, 21 kDa fragments of unglycosylated PrPSc (Type 1) frequently differ from the disease duration and phenotypes associated with the 19 kDa fragments of unglycosylated PrPSc (Type 2).3,5,71,74

Cumulatively, these findings argue that the PrPSc type represents yet an additional major modifier of the phenotype in human prion diseases; accordingly, WB-based clinicopathologic classifications became an important tool in studies of prion pathogenesis in human brains and in transgenic mice models.37,71 Because two distinct PK cleavage sites in PrPSc Types 1 and 2 most likely stem from distinct conformations, some investigators contend that PrPSc Types 1 and 2 code distinct prion strains.3,71,75,80 However, the heterogeneity of sCJD, along with a growing number of studies including bioassays, all suggest that the range of prions causing sCJD exceeds the number of categories recognized within the current WB-based clinicopathologic schemes.81-83 Additionally, recent findings of the co-occurrence of PrPSc Types 1 and 2 in 40% or more sCJD cases created a conundrum and suggested that the originally observed differences were quantitative rather than qualitative.84-89 Finally, up to 90% of brain PrPSc in sCJD eludes WB analysis because it is destroyed by proteinase-K treatment, which is necessary to eliminate PrPC 81. Consequently, the conformation or role of this major protease-sensitive (s) fraction of PrPSc in the pathogenesis of the disease is a subject of speculation.64,81,90 Thus, no direct structural data are available for sCJD brain PrPSc beyond the evidence that it is resistant to proteolytic digestion. Nevertheless, to determine the full spectrum of sCJD prion strains, and the conformational features in the pathogenic human prion protein governing replication of sCJD prions is fundamental for the rational development of diagnostic as well as therapeutic strategies.

Novel conformational methods derived from a conformation-dependent immunoassay (CDI)

Three obstacles have slowed progress in the research of human prions: phenotypic variability of sCJD on complex genetic background, biosafety constraints, and lack of suitable tools for studying molecular characteristics beyond WB typing. Aiming to advance our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of human prion diseases, we developed the conformation-dependent immunoassay (CDI)56,81,91 to determine the conformational range and strain-dependent molecular features of sCJD PrPSc, first in patients who were homozygous for codon 129 of the PRNP gene.92 Even relatively minute variations in a soluble protein structure can be determined by measuring conformational stability in a denaturant such as Gdn HCl.93 Utilizing this concept, we designed a procedure in which PrPSc is first exposed to denaturant Gdn HCl and then exposed to europium-labeled mAb against the epitopes hidden in the native conformation.56 As the concentration of Gdn HCl increases, PrPSc dissociates and unfolds from native β-sheet-structured aggregates, and more epitopes become available to antibody binding. These experiments involve insoluble oligomeric forms of PrPSc, and denaturation of this protein is irreversible in vitro; consequently the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) of PrPSc cannot be calculated.94 Therefore we chose instead to use the Gdn HCl value found at the half-maximal denaturation ([GdnHCl]1/2) as a measure of the relative conformational stability of PrPSc. The differences in stability reveal evidence of distinct conformations of PrPSc 56, 93, 94.

To measure the concentration of different forms of PrPSc and follow the unfolding, we used europium-labeled mAb 3F495 (epitope residues 107–112) for detection and 8H4 mAb (epitope residues 175–185)96 to capture human PrPSc in a sandwich CDI format.81,97 The analytical sensitivity and specificity of the optimized CDI for detection of PrPSc was previously reported by us and others in numerous publications56,81,91,98-100 and has been shown to be as low as ~500 fg (~20 attomoles) of PrPSc which is similar to the sensitivity of human prion bioassay in Tg(MHu2M)5378/Prnp0/0 mice.81 Because CDI is not dependent on protease treatment, it allowed us to address fundamental questions concerning the concentration and conformation of different isoforms of sCJD PrPSc, including protease-sensitive (s) and protease-resistant (r)PrPSc 92.

The dissociation and unfolding of PrPSc in the presence of increasing concentration of Gdn HCl can be described as follows:

[PrPSc]n → [sPrPSc]n → iPrP → uPrP

where [PrPSc]n are native aggregates of PrPSc, [sPrPSc]n are soluble protease-sensitive oligomers of PrPSc, iPrP is an intermediate, and uPrP is completely unfolded (denatured) PrP.53,57,94 The CDI monitors the global transition from native aggregates to fully denatured monomers of PrPSc. In contrast, the WB-based techniques monitor either the partial solubilization of PrPSc 101 or conversion of rPrPSc to protease-sensitive conformers72 after exposure to denaturant. As a result, the stability data on soluble protease-sensitive oligomers and intermediates of PrPSc cannot be obtained with WB techniques and may explain some markedly different values.102

Structural heterogeneity of sCJD PrPSc and the role of sPrPSc in pathogenesis

Our recent finding of 6-fold difference in concentrations of PrPSc between Type 1 and Type 2 PrPSc(129M) in the frontal cortex was surprising, even though some variability was to be expected due to differences in the predominantly affected areas in distinct sCJD phenotypes.81,92 Moreover, the average levels of PrPSc were up to 100-fold lower than those in standard laboratory prion models such as Syrian hamsters infected with Sc237 prions56; and together with the up to 100-fold variability within each phenotypic group, these lower levels of PrPSc may explain why some sCJD cases are difficult to transmit, and why lower endpoint titers are obtained with human prions in transgenic mice expressing human or chimeric PrPC 37, 71, 81, 103.

Up to 90% of the pathogenic prion protein in sCJD is protease-sensitive81 and we found the highest concentrations in Type 2 PrPSc(129M) (Fig. 1).92 The broad range of absolute and relative levels of rPrPSc and sPrPSc offers evidence of a broad spectrum of PrPSc molecules differing in protease sensitivity in each group with an identical polymorphism at codon 129 of the PRNP gene and an identical WB pattern. Moreover, these findings signal the existence of a variety of sCJD PrPSc conformers; and since protease sensitivity is one of the characteristics of prion strains, they also suggest that distinct sCJD prion strains exist.56,57,81,82,104,105

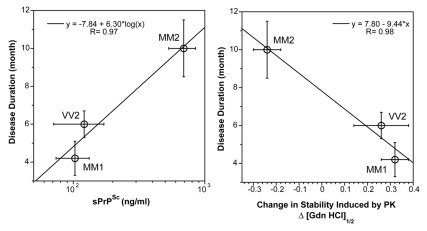

Figure 1. The relationship between duration of the disease, (left panel) concentration, and (right panel) conformational stability of sPrPSc conformers in sCJD patients with different WB patterns and PRNP gene polymorphisms.92 The stability of PrPSc was determined with CDI before and after protease treatment and the change is expressed as ΔGdn HCl1/2.92 The symbols are mean ± SEM in each sCJD group.

The heterogeneity of PrPSc conformations we found with CDI within sCJD patients homozygous for codon 129 plymorphism of the PRNP gene is remarkable, having a range corresponding to that of stabilities found in approximately 30 distinct strains of de-novo and natural laboratory rodent prions studied up to now.56,72,92,106 The intriguing differential effect of PK treatment with increasing stability of type 1 and decreasing stability of Type 2 PrPSc(129M) suggests that in contrast to Type 1, the protease-resistant core of Type 2 was profoundly destabilized. Together with the increased frequency of exposed epitopes in codon 129 MM samples with Type 2 rPrPSc after PK treatment, these observations may indicate one of three possibilities: that the ligand protecting the 3F4 epitope was removed by PK treatment; that epitope 108–112 was protected by the N-terminus of PrPSc; or that conformational transition resulted in more exposed 108–112 epitope. Whether the epitope hindrance in undigested PrPSc is the result of lipid, glycosaminoglycan, nucleic acid, or protein binding to the conformers unique to the MM2 sCJDF PrPSc remains to be established. Since sCJD cases with Type 2 PrPSc(129M) have remarkably extended disease durations, the molecular mechanism underlying these effects calls for detailed investigation. Cumulatively, our findings indicate that sCJD PrPSc exhibits extensive conformational heterogeneity and suggest that a wide spectrum of sCJD prions cause the disease. Whether this heterogeneity originates in a stochastic misfolding process that generates many distinct self-replicating conformations37,62 or in a complex process of evolutionary selection during development of the disease73 remains to be established.

We discovered protease-sensitive conformers of PrPSc while developing a conformation-dependent immunoassay (CDI), which does not require proteolytic degradation of ubiquitous PrPC 56. Although the original definition of sPrPSc was purely operational, considerable additional data demonstrate that (1) sPrPSc replicates in vivo and in vitro as an invariant and major fraction of PrPSc; (2) sPrPSc separates from rPrPSc in high speed centrifugation, and (3) the proteolytic sensitivity of PrPSc can reliably differentiate various prion strains.56,57,81,82,104,105 Accumulation of sPrPSc precedes protease-resistant product (rPrPSc) in prion infection64,107; and up to 90% of PrPSc accumulating in CJD brains consists of sPrPSc 81. Thus, the detection by CDI of sPrPSc as a disease-specific marker is widely regarded as a more reliable basis for diagnosing prion diseases. This improved detection led to the discovery of a new human prion disorder, variably protease-sensitive prionopathy (VPSPr).17,56,81,90,108 It is noteworthy that synthetic prions generated in vitro during polymerization of recombinant mouse PrP into amyloid fibers produced prions composed exclusively of sPrPSc upon inoculation into wild mice.106

Our recent data indicate that the levels as well as stability of sPrPSc are a good predictor of the progression rate in sCJD (Fig. 1).92 Despite the inevitable influence of variable genetic background and the potential difficulties in evaluating initial symptoms, the disease progression rate and incubation time jointly represent an important parameter, which is influenced by replication rate, propagation, and clearance of prions from the brain.64,109 The correlations among the levels of sPrPSc, the stability of sPrPSc, and the duration of the disease found in this study all indicate that sPrPSc conformers play an important role in the pathogenesis. When sPrPSc is less stable than rPrPSc, the difference in stability correlates with less accumulated sPrPSc and shorter duration of the disease. Conversely, when sPrP conformers are more stable than rPrPSc, we observed the opposite effect—more accumulated sPrPSc and extended disease duration (Fig. 1).

In laboratory rodent prion models, we found that levels of sPrPSc varied with the incubation time of the disease56 and we hypothesized that the molecular mechanism of this link may be related to the replication or clearance rate of prions.56,64,81 Our recent data on sCJD prions extend this observation and indicate that higher levels of less stable sPrPSc lead to faster progression of the disease.92 These observations are in accord with the experiments on yeast prions and suggest that the stability of misfolded protein is inversely related to the replication rate.110 Although the modulating effect of prion clearance in the mammalian brains is likely,64 the data from both yeast and human prions lead to the hypothesis that the less stable prions replicate faster by exposing more available sites for growth of the aggregates. In mammalian prions, this effect leads to shorter incubation time and faster progression of the disease.

Future directions

Additional steps are necessary to improve our understanding of the phenotypic diversity of sCJD. One step is to determine whether the mixed WB patterns of Type 1–2 rPrPSc in the same or different anatomical areas represent a unique conformation or a mixture of conformers, and to map the distribution in the individual brain.89 Additionally, novel conformational approaches using tandem protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) and CDI should allow analysis of the impact of different PrPSc polymorphisms and conformations on the replication rate of human prions. Such studies have clearly broader implications, as recent data suggest that the process of intercellular induction of protein misfolding is relevant in the pathogenesis of growing number of other neurodegenerative diseases.39-43

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pierlugi Gambetti and Witold Surewicz for encouragement and stimulating discussions. This work was supported by grants from NIA (AG-14359), NINDS (NS074317), CDC (UR8/CCU515004), and the Charles S. Britton Fund.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CDI

conformation-dependent immunoassay

- CJD

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- GSS

Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPC

normal or cellular prion protein

- PrPSc

pathogenic prion protein

- PRNP

prion protein gene

- rPrPSc

protease-resistant conformers of pathogenic prion protein

- sPrPSc

protease-sensitive conformers of pathogenic prion protein

- sCJD

sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- SFI

sporadic fatal insomnia

- VPSPr

variable protease-sensitive prionopathy

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/prion/article/18666

References

- 1.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–44. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gajdusek DC. Slow-virus infections of the nervous system. N Engl J Med. 1967;276:392–400. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196702162760708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monari L, Chen SG, Brown P, Parchi P, Petersen RB, Mikol J, et al. Fatal familial insomnia and familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: different prion proteins determined by a DNA polymorphism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2839–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, Brown P, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Windl O, et al. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:224–33. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199908)46:2<224::AID-ANA12>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gambetti P, Kong Q, Zou W, Parchi P, Chen SG. Sporadic and familial CJD: classification and characterisation. Br Med Bull. 2003;66:213–39. doi: 10.1093/bmb/66.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prusiner SB, ed. Prion Biology and Diseases. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holman RC, Belay ED, Christensen KY, Maddox RA, Minino AM, Folkema AM, et al. Human prion diseases in the United States. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masters CL, Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ Jr., Bernouilli C, Asher DM. Familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and other familial dementias: an inquiry into possible models of virus-induced familial diseases. In: Prusiner SB, Hadlow WJ, eds. Slow Transmissible Diseases of the Nervous System, Vol 1. New York: Academic Press, 1979:143-94. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakob A. Über eine der multiplen Sklerose klinisch nahestehende Erkrankung des Zentralnervensystems (spastische Pseudosklerose) mit bemerkenswertem anatomischem Befunde. Mitteilung eines vierten Falles. Med Klin (Munich) 1921;17:372–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creutzfeldt HG. Über eine eigenartige herdförmige Erkrankung des Zentralnervensystems. Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr. 1920;57:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF02866081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masters CL, Gajdusek DC. The spectrum of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and virus-induced subacute spongiform encephalopathies. Recent Adv Neuropathol. 1982;2:139–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson SAK. Syndrome of Jakob: Cortico-striato-spinal degeneration. London: Edward Arnold, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirschbaum WR. Jakob-Creutzfeldt Disease. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nevin S, McMENEMEY WH, Behrman S, Jones DP. Subacute spongiform encephalopathy--a subacute form of encephalopathy attributable to vascular dysfunction (spongiform cerebral atrophy) Brain. 1960;83:519–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/83.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gambetti P, Parchi P. Insomnia in prion diseases: sporadic and familial. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1675–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905273402111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mastrianni J, Nixon F, Layzer R, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB. Fatal sporadic insomnia: fatal familial insomnia phenotype without a mutation of the prion protein gene. Neurology. 1997;48(Suppl.):A296. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gambetti P, Dong Z, Yuan J, Xiao X, Zheng M, Alshekhlee A, et al. A novel human disease with abnormal prion protein sensitive to protease. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:697–708. doi: 10.1002/ana.21420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gajdusek DC, Zigas V. Kuru; clinical, pathological and epidemiological study of an acute progressive degenerative disease of the central nervous system among natives of the Eastern Highlands of New Guinea. Am J Med. 1959;26:442–69. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(59)90251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gajdusek DC, Zigas V. Degenerative disease of the central nervous system in New Guinea; the endemic occurrence of kuru in the native population. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:974–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195711142572005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajdusek DC. Kuru. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1963;57:151–69. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(63)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hadlow WJ. Scrapie and kuru. Lancet. 1959;274:289–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(59)92081-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibbs CJ, Jr., Gajdusek DC, Asher DM, Alpers MP, Beck E, Daniel PM, et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (spongiform encephalopathy): transmission to the chimpanzee. Science. 1968;161:388–9. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3839.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ, Jr., Alpers M. Experimental transmission of a Kuru-like syndrome to chimpanzees. Nature. 1966;209:794–6. doi: 10.1038/209794a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masters CL, Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ., Jr. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease virus isolations from the Gerstmann-Sträussler syndrome with an analysis of the various forms of amyloid plaque deposition in the virus-induced spongiform encephalopathies. Brain. 1981;104:559–88. doi: 10.1093/brain/104.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tateishi J, Brown P, Kitamoto T, Hoque ZM, Roos R, Wollman R, et al. First experimental transmission of fatal familial insomnia. Nature. 1995;376:434–5. doi: 10.1038/376434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakob A. Über eigenartige Erkrankungen des Zentralnervensystems mit bemerkenswertem anatomischen Befunde (spastische Pseudosklerose-Encephalomyelopathie mit disseminierten Degenerationsherden) Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr. 1921;64:147–228. doi: 10.1007/BF02870932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loftus B, Rogers M. Characterization of a prion protein (PrP) gene from rabbit; a species with apparent resistance to infection by prions. Gene. 1997;184:215–9. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00598-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klatzo I, Gajdusek DC, Zigas V. Pathology of Kuru. Lab Invest. 1959;8:799–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibbs CJ, Jr., Gajdusek DC. Experimental subacute spongiform virus encephalopathies in primates and other laboratory animals. Science. 1973;182:67–8. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4107.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lampert PW, Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ., Jr. Experimental spongiform encephalopathy (Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease) in chimpanzees. Electron microscopic studies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1971;30:20–32. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck E, Daniel PM, Matthews WB, Stevens DL, Alpers MP, Asher DM, et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. The neuropathology of a transmission experiment. Brain. 1969;92:699–716. doi: 10.1093/brain/92.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sigurdsson B. Rida, a chronic encephalitis of sheep with general remarks on infections which develop slowly and some of their special characteristics. Br Vet J. 1954;110:341–54. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safar JG, Kellings K, Serban A, Groth D, Cleaver JE, Prusiner SB, et al. Search for a prion-specific nucleic acid. J Virol. 2005;79:10796–806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10796-10806.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riesner D. The search for a nucleic acid component to scrapie infectivity. Semin Virol. 1991;2:215–26. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caughey B, Baron GS, Chesebro B, Jeffrey M. Getting a grip on prions: oligomers, amyloids, and pathological membrane interactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:177–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082907.145410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cobb NJ, Surewicz WK. Prion diseases and their biochemical mechanisms. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2574–85. doi: 10.1021/bi900108v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collinge J, Clarke AR. A general model of prion strains and their pathogenicity. Science. 2007;318:930–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1138718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morales R, Abid K, Soto C. The prion strain phenomenon: molecular basis and unprecedented features. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007; 1772:681-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, Kilger E, et al. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science. 2006;313:1781–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1131864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frost B, Jacks RL, Diamond MI. Propagation of tau misfolding from the outside to the inside of a cell. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12845–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808759200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Crews L, et al. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13010–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luk KC, Song C, O’Brien P, Stieber A, Branch JR, Brunden KR, et al. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils seed the formation of Lewy body-like intracellular inclusions in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:20051–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao W, Beers DR, Henkel JS, Zhang W, Urushitani M, Julien JP, et al. Extracellular mutant SOD1 induces microglial-mediated motoneuron injury. Glia. 2010;58:231–43. doi: 10.1002/glia.20919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oesch B, Westaway D, Wälchli M, McKinley MP, Kent SBH, Aebersold R, et al. A cellular gene encodes scrapie PrP 27-30 protein. Cell. 1985;40:735–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90333-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liao Y-C, Lebo RV, Clawson GA, Smuckler EA. Human prion protein cDNA: molecular cloning, chromosomal mapping, and biological implications. Science. 1986;233:364–7. doi: 10.1126/science.3014653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baldwin MA, Stahl N, Burlingame AL, Prusiner SB. Structure determination of glycoinsotiol phospholipid anchors by permethylation and tandem mass spectrometry. Methods: A Companion to Methods in Enzymology 1990; 1:306-14.

- 47.Baldwin MA, Stahl N, Reinders LG, Gibson BW, Prusiner SB, Burlingame AL. Permethylation and tandem mass spectrometry of oligosaccharides having free hexosamine: analysis of the glycoinositol phospholipid anchor glycan from the scrapie prion protein. Anal Biochem. 1990;191:174–82. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90405-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Safar J, Ceroni M, Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ., Jr. Differences in the membrane interaction of scrapie amyloid precursor proteins in normal and scrapie- or Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease-infected brains. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:488–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haraguchi T, Fisher S, Olofsson S, Endo T, Groth D, Tarentino A, et al. Asparagine-linked glycosylation of the scrapie and cellular prion proteins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;274:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90409-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stahl N, Baldwin MA, Burlingame AL, Prusiner SB. Identification of glycoinositol phospholipid linked and truncated forms of the scrapie prion protein. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8879–84. doi: 10.1021/bi00490a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zahn R, Liu A, Lührs T, Riek R, von Schroetter C, López García F, et al. NMR solution structure of the human prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:145–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pan K-M, Baldwin M, Nguyen J, Gasset M, Serban A, Groth D, et al. Conversion of alpha-helices into beta-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10962–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Safar J, Roller PP, Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ., Jr. Conformational transitions, dissociation, and unfolding of scrapie amyloid (prion) protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20276–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caughey BW, Dong A, Bhat KS, Ernst D, Hayes SF, Caughey WS. Secondary structure analysis of the scrapie-associated protein PrP 27-30 in water by infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1991;30:7672–80. doi: 10.1021/bi00245a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smirnovas V, Kim JI, Lu X, Atarashi R, Caughey B, Surewicz WK. Distinct structures of scrapie prion protein (PrPSc)-seeded versus spontaneous recombinant prion protein fibrils revealed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24233–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Safar J, Wille H, Itri V, Groth D, Serban H, Torchia M, et al. Eight prion strains have PrP(Sc) molecules with different conformations. Nat Med. 1998;4:1157–65. doi: 10.1038/2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tzaban S, Friedlander G, Schonberger O, Horonchik L, Yedidia Y, Shaked G, et al. Protease-sensitive scrapie prion protein in aggregates of heterogeneous sizes. Biochemistry. 2002;41:12868–75. doi: 10.1021/bi025958g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nazor KE, Kuhn F, Seward T, Green M, Zwald D, Pürro M, et al. Immunodetection of disease-associated mutant PrP, which accelerates disease in GSS transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2005;24:2472–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aguzzi A, Baumann F, Bremer J. The prion’s elusive reason for being. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:439–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Westergard L, Christensen HM, Harris DA. The cellular prion protein (PrP(C)): its physiological function and role in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:629–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Milhavet O, Lehmann S. Oxidative stress and the prion protein in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;38:328–39. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prusiner SB. Shattuck lecture--neurodegenerative diseases and prions. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1516–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105173442006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tremblay P, Ball HL, Kaneko K, Groth D, Hegde RS, Cohen FE, et al. Mutant PrPSc conformers induced by a synthetic peptide and several prion strains. J Virol. 2004;78:2088–99. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.2088-2099.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Safar JG, DeArmond SJ, Kociuba K, Deering C, Didorenko S, Bouzamondo-Bernstein E, et al. Prion clearance in bigenic mice. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:2913–23. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80947-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yuan J, Xiao X, McGeehan J, Dong Z, Cali I, Fujioka H, et al. Insoluble aggregates and protease-resistant conformers of prion protein in uninfected human brains. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34848–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Linsell L, Cousens SN, Smith PG, Knight RS, Zeidler M, Stewart G, et al. A case-control study of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the United Kingdom: analysis of clustering. Neurology. 2004;63:2077–83. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145844.53251.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cathala F, Baron H. Clinical aspects of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. In: Prusiner SB, McKinley MP, eds. Prions - Novel Infectious Pathogens Causing Scrapie and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Orlando: Academic Press, 1987:467-509. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown P, Cathala F, Castaigne P, Gajdusek DC. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: clinical analysis of a consecutive series of 230 neuropathologically verified cases. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:597–602. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown P, Cathala F, Sadowsky D, Gajdusek DC. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in France: II. Clinical characteristics of 124 consecutive verified cases during the decade 1968--1977. Ann Neurol. 1979;6:430–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.410060510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bessen RA, Marsh RF. Distinct PrP properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J Virol. 1994;68:7859–68. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7859-7868.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Telling GC, Parchi P, DeArmond SJ, Cortelli P, Montagna P, Gabizon R, et al. Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion protein enciphering and propagating prion diversity. Science. 1996;274:2079–82. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peretz D, Scott MR, Groth D, Williamson RA, Burton DR, Cohen FE, et al. Strain-specified relative conformational stability of the scrapie prion protein. Protein Sci. 2001;10:854–63. doi: 10.1110/ps.39201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li J, Browning S, Mahal SP, Oelschlegel AM, Weissmann C. Darwinian evolution of prions in cell culture. Science. 2010;327:869–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1183218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Parchi P, Capellari S, Chen SG, Petersen RB, Gambetti P, Kopp N, et al. Typing prion isoforms. Nature. 1997;386:232–4. doi: 10.1038/386232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Collinge J, Sidle KCL, Meads J, Ironside J, Hill AF. Molecular analysis of prion strain variation and the aetiology of ‘new variant’ CJD. Nature. 1996;383:685–90. doi: 10.1038/383685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wadsworth JDF, Hill AF, Joiner S, Jackson GS, Clarke AR, Collinge J. Strain-specific prion-protein conformation determined by metal ions. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:55–9. doi: 10.1038/9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zou WQ, Capellari S, Parchi P, Sy MS, Gambetti P, Chen SG. Identification of novel proteinase K-resistant C-terminal fragments of PrP in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40429–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308550200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Safar JG, Giles K, Lessard P, Letessier F, Patel S, Serban A, et al. Conserved properties of human and bovine prion strains on transmission to guinea pigs. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1326–36. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hill AF, Desbruslais M, Joiner S, Sidle KCL, Gowland I, Collinge J, et al. The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature. 1997;389:448–50, 526. doi: 10.1038/38925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parchi P, Castellani R, Capellari S, Ghetti B, Young K, Chen SG, et al. Molecular basis of phenotypic variability in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:767–78. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Safar JG, Geschwind MD, Deering C, Didorenko S, Sattavat M, Sanchez H, et al. Diagnosis of human prion disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3501–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Uro-Coste E, Cassard H, Simon S, Lugan S, Bilheude JM, Perret-Liaudet A, et al. Beyond PrP9res) type 1/type 2 dichotomy in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000029. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Polymenidou M, Stoeck K, Glatzel M, Vey M, Bellon A, Aguzzi A. Coexistence of multiple PrPSc types in individuals with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:805–14. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Puoti G, Giaccone G, Rossi G, Canciani B, Bugiani O, Tagliavini F. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: co-occurrence of different types of PrP(Sc) in the same brain. Neurology. 1999;53:2173–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kovács GG, Head MW, Hegyi I, Bunn TJ, Flicker H, Hainfellner JA, et al. Immunohistochemistry for the prion protein: comparison of different monoclonal antibodies in human prion disease subtypes. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Head MW, Bunn TJ, Bishop MT, McLoughlin V, Lowrie S, McKimmie CS, et al. Prion protein heterogeneity in sporadic but not variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: UK cases 1991-2002. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:851–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lewis V, Hill AF, Klug GM, Boyd A, Masters CL, Collins SJ. Australian sporadic CJD analysis supports endogenous determinants of molecular-clinical profiles. Neurology. 2005;65:113–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167188.65787.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schoch G, Seeger H, Bogousslavsky J, Tolnay M, Janzer RC, Aguzzi A, et al. Analysis of prion strains by PrPSc profiling in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cali I, Castellani R, Alshekhlee A, Cohen Y, Blevins J, Yuan J, et al. Co-existence of scrapie prion protein types 1 and 2 in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: its effect on the phenotype and prion-type characteristics. Brain. 2009;132:2643–58. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cronier S, Gros N, Tattum MH, Jackson GS, Clarke AR, Collinge J, et al. Detection and characterization of proteinase K-sensitive disease-related prion protein with thermolysin. Biochem J. 2008;416:297–305. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Safar JG, Scott M, Monaghan J, Deering C, Didorenko S, Vergara J, et al. Measuring prions causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy or chronic wasting disease by immunoassays and transgenic mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:1147–50. doi: 10.1038/nbt748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim C, Haldiman T, Cohen Y, Chen W, Blevins J, Sy MS, et al. Protease-sensitive conformers in broad spectrum of distinct PrPSc structures in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease are indicator of progression rate. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002242. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shirley BA, ed. Protein Stability and Folding: Theory and Practice. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Safar J, Roller PP, Gajdusek DC, Gibbs CJ., Jr. Scrapie amyloid (prion) protein has the conformational characteristics of an aggregated molten globule folding intermediate. Biochemistry. 1994;33:8375–83. doi: 10.1021/bi00193a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Tonna-DeMasi M, Fersko R, Carp RI, et al. Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J Virol. 1987;61:3688–93. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3688-3693.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zanusso G, Liu D, Ferrari S, Hegyi I, Yin X, Aguzzi A, et al. Prion protein expression in different species: analysis with a panel of new mAbs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8812–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Choi EM, Geschwind MD, Deering C, Pomeroy K, Kuo A, Miller BL, et al. Prion proteins in subpopulations of white blood cells from patients with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lab Invest. 2009;89:624–35. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bellon A, Seyfert-Brandt W, Lang W, Baron H, Gröner A, Vey M. Improved conformation-dependent immunoassay: suitability for human prion detection with enhanced sensitivity. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:1921–5. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18996-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Thackray AM, Hopkins L, Bujdoso R. Proteinase K-sensitive disease-associated ovine prion protein revealed by conformation-dependent immunoassay. Biochem J. 2007;401:475–83. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jones M, Peden AH, Yull H, Wight D, Bishop MT, Prowse CV, et al. Human platelets as a substrate source for the in vitro amplification of the abnormal prion protein (PrP) associated with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Transfusion. 2009;49:376–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pirisinu L, Di Bari M, Marcon S, Vaccari G, D’Agostino C, Fazzi P, et al. A new method for the characterization of strain-specific conformational stability of protease-sensitive and protease-resistant PrP. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Choi YP, Peden AH, Gröner A, Ironside JW, Head MW. Distinct stability states of disease-associated human prion protein identified by conformation-dependent immunoassay. J Virol. 2010;84:12030–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01057-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bishop MT, Will RG, Manson JC. Defining sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease strains and their transmission properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12005–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004688107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pastrana MA, Sajnani G, Onisko B, Castilla J, Morales R, Soto C, et al. Isolation and characterization of a proteinase K-sensitive PrPSc fraction. Biochemistry. 2006;45:15710–7. doi: 10.1021/bi0615442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Notari S, Strammiello R, Capellari S, Giese A, Cescatti M, Grassi J, et al. Characterization of truncated forms of abnormal prion protein in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:30557–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801877200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Colby DW, Wain R, Baskakov IV, Legname G, Palmer CG, Nguyen HO, et al. Protease-sensitive synthetic prions. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000736. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mallucci GR, White MD, Farmer M, Dickinson A, Khatun H, Powell AD, et al. Targeting cellular prion protein reverses early cognitive deficits and neurophysiological dysfunction in prion-infected mice. Neuron. 2007;53:325–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jones M, Peden AH, Prowse CV, Gröner A, Manson JC, Turner ML, et al. In vitro amplification and detection of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease PrPSc. J Pathol. 2007;213:21–6. doi: 10.1002/path.2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Prusiner SB, Scott MR, DeArmond SJ, Carlson G. Transmission and replication of prions. In: Prusiner SB, ed. Prion Biology and Diseases. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2004:187-242. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tanaka M, Collins SR, Toyama BH, Weissman JS. The physical basis of how prion conformations determine strain phenotypes. Nature. 2006;442:585–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]