Abstract

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) are key regulators of posttranscriptional gene silencing, which is referred to as RNA interference (RNAi) or RNA silencing. In RNAi, siRNA loaded onto the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) downreugulates target gene expression by cleaving mRNA whose sequence is perfectly complementary to the siRNA guide strand. We previously showed that highly functional siRNAs possessed the following characteristics: A or U residues at nucleotide position 1 measured from the 5′ terminal, four to seven A/Us in positions 1–7, and G or C residues at position 19. This finding indicated that an RNA strand with a thermodynamically unstable 5′ terminal is easily retained in the RISC and functions as a guide strand. In addition, it is clear that unintended genes with complementarities only in the seed region (positions 2–8) are also downregulated by off-target effects. siRNA efficiency is mainly determined by the Watson–Crick base-pairing stability formed between the siRNA seed region and target mRNA. siRNAs with a low seed-target duplex melting temperature (Tm) have little or no seed-dependent off-target activity. Thus, important parts of the RNA silencing machinery may be regulated by nucleotide base-pairing thermodynamic stability. A mechanistic understanding of thermodynamic control may enable an efficient target gene-specific RNAi for functional genomics and safe therapeutic applications.

Keywords: siRNA, RNAi, off-target effect, thermodynamic stability, seed region

Introduction

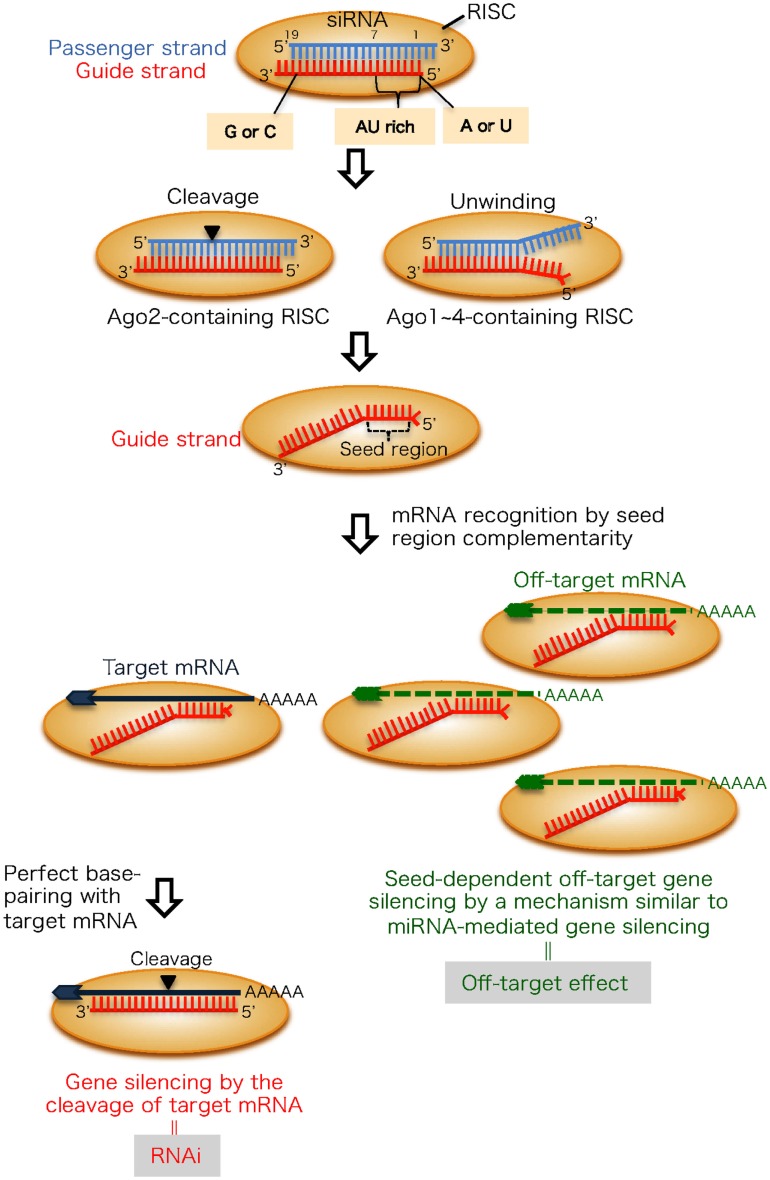

Small RNA molecules, including small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), are crucial regulators of posttranscriptional gene silencing referred to as RNA interference (RNAi) or RNA silencing. RNAi is an evolutionarily conserved pathway induced by siRNAs, 21–23-nt double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) with 2-nt 3′ overhangs (Figure 1). siRNAs incorporated into cells are transferred to an RNAi effector complex called the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC; Hutvagner and Simard, 2008; Jinek and Doudna, 2009). The RISC assembles on one of the two strands of the siRNA duplex and is activated upon removal of the passenger strand (Martinez et al., 2002; Schwarz et al., 2002, 2003; Khvorova et al., 2003; Ui-Tei et al., 2004). We and others reported that asymmetrical features of both siRNA terminals are common to functional siRNAs (Amarzguioui and Prydz, 2004; Reynolds et al., 2004; Ui-Tei et al., 2004). An RNA strand with a thermodynamically unstable 5′ terminal is easily retained in the RISC. The activated RISC is a ribonucleoprotein complex that minimally consists of the core protein Argonaute (Ago) and a siRNA guide strand, which recognizes mRNAs with complementary sequences (Liu et al., 2004; Meister et al., 2004; Song et al., 2004). In siRNA-mediated RNAi, the Ago2 protein siRNA guide strand usually base-pairs with mRNA that is perfectly complementary and cleaves them (Figure 1). However, this can also lead to silencing of other genes with incompletely complementary sequences. This phenomenon is referred to as an off-target effect (Figure 1). The target recognition mechanism of the off-target effect is similar to that of miRNA-mediated gene silencing (Jackson et al., 2003, 2006a; Bartel, 2004; Scacheri et al., 2004; Lewis et al., 2005; Lim et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2005; Birmingham et al., 2006; Grimson et al., 2007). The transcripts with sequences complementary to the seed region (i.e., nucleotide positions 2–8 from the 5′ end of siRNA guide strand or miRNA loaded on Ago1–4 proteins) are mainly reduced. This is likely because seed nucleotides are present on the Ago surface in a quasi-helical form to serve as the entry or nucleation site for small RNAs in the RISCs (Ma et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2005; Ui-Tei et al., 2008a). Thus, siRNA target recognition might be partially determined by structural features. However, the off-target effect silencing efficiency is mainly determined by the thermodynamic properties of nucleotide base-pairing between the siRNA guide strand seed region and their off-target mRNAs (Ui-Tei et al., 2008a). Understanding thermodynamic control of the siRNA off-target effect may make it possible to avoid the off-target effect for a target gene-specific RNAi.

Figure 1.

The mechanism of RNAi and its off-target effect in mammalian cells. An RNA strand with A or U at position 1, four to seven A/Us in positions 1–7 and G/C at position 19 (measured from the guide strand 5′ end) are easily unwound from the 5′ end and retained in the RISC. The passenger strand is dissociated from the Ago1 ∼ 4-containing RISC following unwinding, but cleaved in the Ago2-containing RISC. The guide strand recognizes target and off-target transcripts with complementary sequences to seed region positions 2–8. The target transcript, which has complete complementarity in positions 9-21, in addition to positions 2–8, is knocked down by RNAi. Conversely, off-target transcripts are downregulated according to the thermodynamic stability in the duplex formed between the siRNA seed region and target mRNA.

Functional siRNA Sequences

RNA interference efficiency in mammalian cells varies considerably depending on the siRNA sequence (Holen et al., 2002; Harborth et al., 2003). We showed that there are three siRNA classes based on their RNAi gene silencing activity (Ui-Tei et al., 2004). Class I siRNAs, which are highly functional in mammalian RNAi, have A or U residues at nucleotide position 1, four to seven A/Us in nucleotide positions 1–7 (AU ≥ 57%) and G/C at position 19, with the nucleotide position measured from the 5′ end of the guide strand (Figure 1). In addition, a GC stretch of no more than nine nucleotides occurs in class I siRNA sequences. Class III siRNAs have opposite features with respect to the first three conditions and cause the least RNAi-silencing effects. The remaining siRNAs belong to class II and are a mixture of functional and non-functional siRNAs.

We and others demonstrated that functional siRNA with an unstable RNA strand 5′ terminal in the siRNA duplex is functional as a guide strand (Amarzguioui and Prydz, 2004; Reynolds et al., 2004; Ui-Tei et al., 2004); A or U residues at the 5′ end of the guide strand are especially important. In RNAi, thermodynamic asymmetry is not essential for target gene silencing because the passenger strand of most double-stranded siRNAs loaded onto RISC are cleaved by catalytic activity of the Ago2 protein and degraded (Figure 1; Kawamata et al., 2009; Yoda et al., 2010). Thus, in this case, A/U nucleotide itself at 5′ terminal might be strongly contributed to the RNAi activity, as nucleotide monophosphates, AMP, and UMP, bind to Ago2 with up to 30-fold higher affinity than either CMP or GMP (Frank et al., 2010). However, when the siRNA duplex is loaded into other Ago proteins without slicer activity, siRNAs might be unwound into a single-strand from the thermodynamically unstable 5′ terminal as shown in miRNA-mediated gene silencing (Figure 1; Matranga et al., 2005; Miyoshi et al., 2005; Leuschner et al., 2006; Kawamata et al., 2009; Yoda et al., 2010). As off-target gene silencing is performed using both mechanisms for eliminating the passenger strand, siRNA thermodynamic asymmetry in addition to A/U nucleotide itself at the 5′ terminal might be involved in seed-dependent off-target effects.

Seed-Dependent Off-Target Effect Efficiency Varies Depending on Seed Sequence

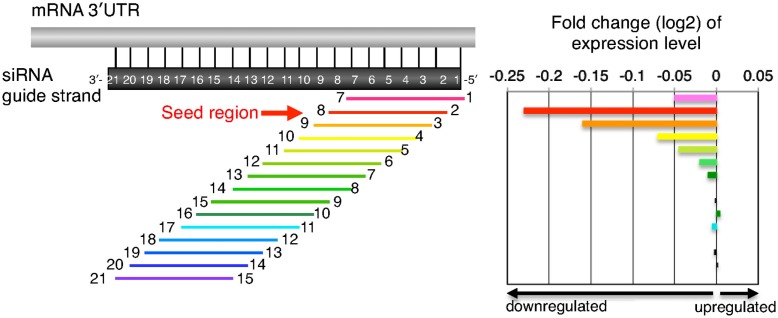

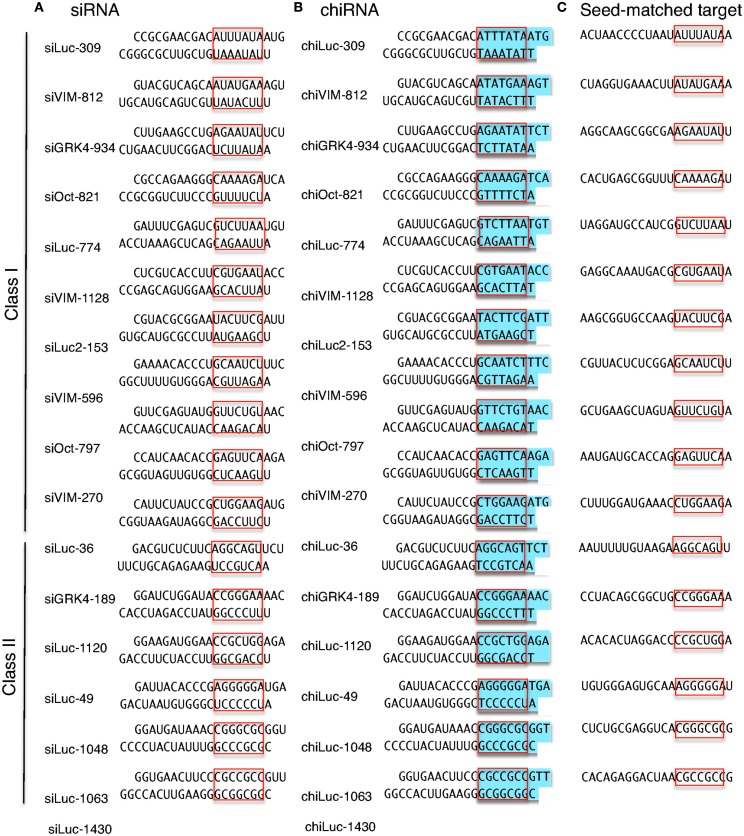

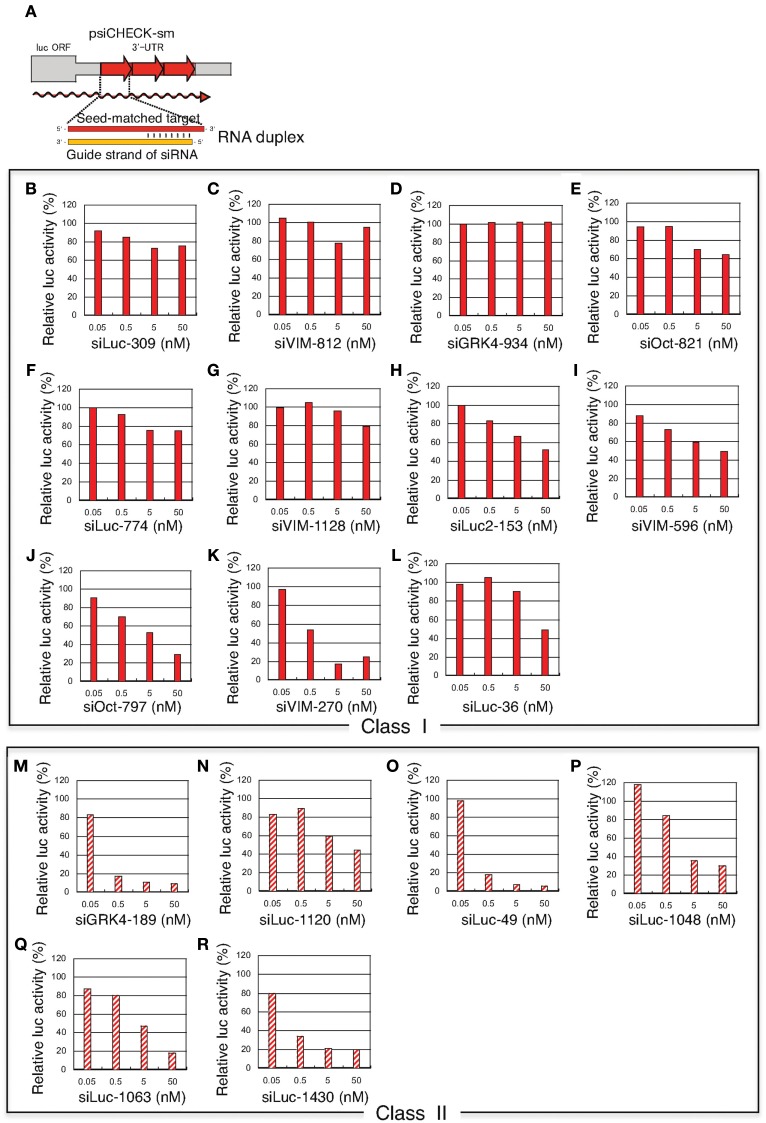

Accumulated evidence from large-scale knockdown experiments (Jackson et al., 2003, 2006a; Scacheri et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2005; Birmingham et al., 2006) suggests that siRNA can generate off-target effects through a mechanism similar to that of miRNA target silencing (Lewis et al., 2005; Lim et al., 2005; Grimson et al., 2007). The 3′UTRs of off-target transcripts or miRNA targets are complementary to the guide strand seed region (i.e., nucleotide positions 2–8; Figure 2; Lim et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2005; Birmingham et al., 2006; Jackson et al., 2006a). We determined the relationship between class I siRNA seed sequences and off-target effect using the expression reporter plasmid, psiCHECK, which encodes the Renilla luciferase gene. Three tandem repeats of seed-matched target sequences (Figure 3C) complementary to the entire seed-containing region (positions 1–8), but not to the remaining non-seed region (positions 9–21), were introduced into the region corresponding to the 3′UTR of the luciferase mRNA to generate psiCHECK-sm and used to determine the efficiency of the seed-dependent unintended off-target effect (see Figure 4A; Ui-Tei et al., 2008a). Although all siRNAs examined exhibited high activity for intended gene silencing at 50 nM, the off-target gene silencing calculated using psiCHECK-sm was much less effective and more susceptible to changes in siRNA concentration (Ui-Tei et al., 2008a). These findings indicated that variations in the efficiency of unintended off-target gene silencing were due to a difference in the interactions between the guide strand RNA entrapped in the RISC and mRNA.

Figure 2.

Schematic presentation of downregulation of transcripts with seed-complementary sequences. In the left panel, transcripts possessing 3′UTR complementarity to a given 7-nt-long guide strand sequence were divided into 15 groups based on the position of the complementary sequence in the siRNA guide strand. Transcripts labeled with “1” and “7” at both ends possess complementarity to nucleotides 1–7 of the siRNA guide strand and vice versa. The horizontal arrow indicates a transcript group with seed complementarity. In the right panel, changes in gene expression levels are shown by log 2 of fold change ratio to mock transfection. Note that the groups of transcripts labeled with 2–8 are the most sensitive to the off-target effects, suggesting that guide strand nucleotides 2–8 serve as a “seed.”

Figure 3.

Structures and sequences of siRNAs and chiRNAs used in this study and their seed-matched target sequences. (A) The structures of 11 human class I siRNAs and six class II siRNAs. (B) The structures of 11 human class I chiRNAs and six class II chiRNAs. (C) The seed-matched target sequences used for psiCHECK-sm constructs shown in Figures 4 and 7. The red box indicates the seed region, and blue indicates the DNA-substituted regions within the chiRNA.

Figure 4.

Concentration-dependent gene silencing effects of authentic siRNA of seed-matched targets. Both class I siRNAs and functional class II siRNAs were included. The gene silencing effects were examined using HeLa cells transfected with psiCHECK-sm plasmids containing various seed-matched targets. The relative luciferase (luc) activity in transfected HeLa cells was determined using a dual luciferase assay. (A) Authentic, non-modified siRNA psiCHECK-sm plasmid structures and gene silencing mechanism. Three tandem repeats of seed-matched target sequences were introduced into the region corresponding to the 3′UTR of the luciferase mRNA. In (B–R), the effects of non-modified siRNA transfection on seed-matched targets are shown. (B–L) class I siRNAs, (M–R) class II siRNAs, (B) siLuc-309, (C) VIM-812, (D) GRK4-934, (E) Oct-821, (F) Luc-774, (G) VIM-1128, (H) Luc2-153, (I) VIM-596, (J) Oct-797, (K) VIM-270, (L) Luc-36, (M) GRK4-189, (N) Luc-1120, (O) Luc-49, (P) Luc-1048, (Q) Luc-1063, (R) Luc-1430. siRNA sequences and structures are shown in Figure 3A.

Seed-Dependent Off-Target Effect Efficiency Varies Depending on Seed Region GC Content

Class I siRNA seed region GC content used in our previous study (Ui-Tei et al., 2008a) ranged from 0 to 57%. To further determine the relationship between seed region GC content exceeding 57% and off-targeting efficiency of the corresponding siRNA, six functional class II siRNAs with high GC content in the seed region were arbitrarily selected (Figure 3A), and their capability to exert off-target effects was examined using luciferase reporter assays (Figure 4; Ui-Tei et al., 2009). Note that two of the six class II siRNAs (siLuc-1063 and siLuc-1430) possessed a 100% GC content in the seed region (Figure 3A). In contrast to class I siRNAs, which have little or no off-target effects, class II siRNAs were frequently associated with a considerable level of off-target gene silencing on the seed-matched targets (Figure 4). This apparent difference in the off-target effect may be due to differences in the GC content in the seed region between functional class I and II siRNAs.

Seed-Dependent Off-Target Effect is Determined by Thermodynamic Stability in the Duplex Formed Between the siRNA Guide Strand Seed Region and Target mRNA

The results shown above indicated that siRNAs with high GC content in the seed sequence have strong seed-dependent off-target effects. Thus, one possible efficiency regulator of the seed-dependent off-target effect might be the thermodynamic stability of the nucleotide duplex. The melting temperature (Tm) and standard free energy change (ΔG) of the seed–target duplex formation are good measures of the thermodynamic stability of the protein-free seed–target duplex. In a previous experiment using class I siRNAs (Ui-Tei et al., 2008a), we verified a close linear relationship between ΔG and Tm in seed region positions 2–8; a strong positive correlation between luciferase activity and ΔG (r = 0.69), and a strong negative correlation between Tm and luciferase activity (r = −0.72) was found. By replacing class I siRNAs with a mixture of class I and II siRNAs, the ΔG range expanded from −13 and −7 to between −19 and −7 kcal/mol (Figures 5A,B), while the Tm range expanded from −8 and 28°C to −8 and 55°C (Figures 5A,C). Correlation coefficients between luciferase activity and ΔG or Tm were 0.72 or −0.76, respectively, indicating a close relationship between the seed-dependent off-target effect and the seed duplex ΔG and Tm. The linear relationships among these parameters were almost invariant (Figure 5A). The dissociation constant (Kd) of the 17 siRNAs calculated using the formula ΔG = −RTln(1/Kd) indicated that the highest Kd was more than 108 times greater than the lowest one (Table 1). Therefore, it may follow that in both functional class I and II siRNA-mediated gene silencing, the degree of off-target effects is governed primarily by the thermodynamic stability of the seed-target duplex formed between the seed region of the siRNA guide strand and its mRNA counterpart. In Figure 6A, all possible 7-nt seed sequences (47 = 16,384) were ordered as a function of GC content and Tm values of their double-stranded counterparts, and the siRNAs were plotted against the absence or presence of off-target effects. The data suggest that Tm values between 21 and 25°C serve as a Tm boundary, which may discriminate off-target-free seed sequences from off-target-positive ones. Approximately 22% of 7-nt sequences had Tm values under 21°C, indicating that limited seed sequences are available for selecting siRNAs with reduced off-target effects.

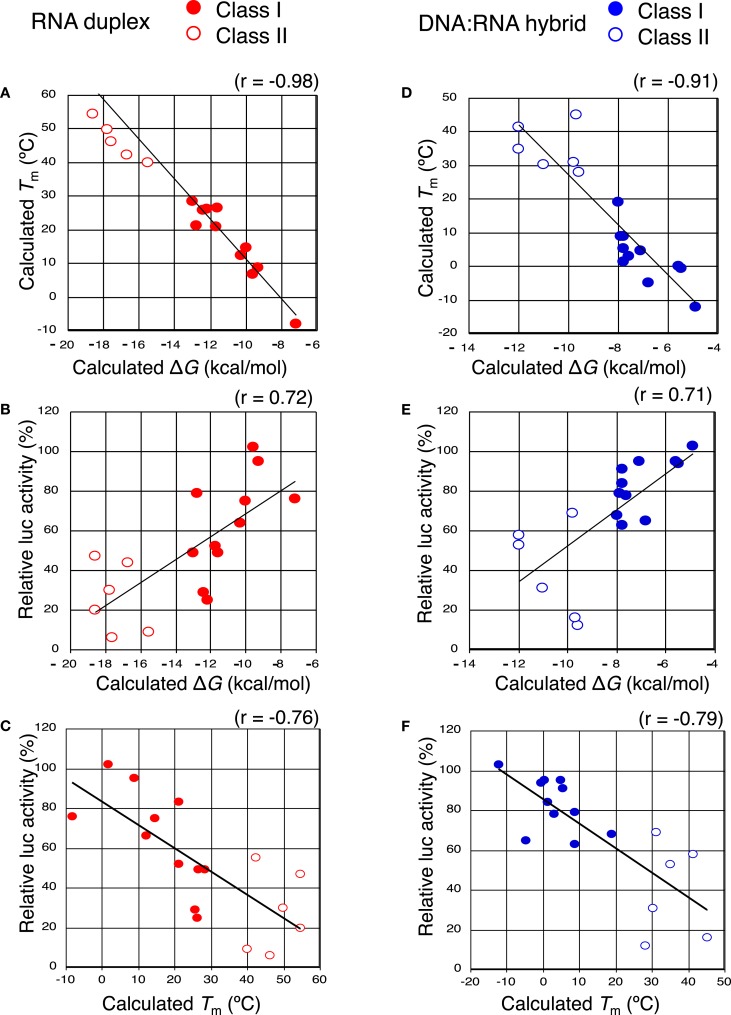

Figure 5.

The close relationship between the efficiency of seed-dependent off-target gene silencing and seed-target duplex thermodynamic stability. Both class I siRNAs and functional class II siRNAs (A–C) and class I chiRNAs and functional class II chiRNAs (D–F) were analyzed. Solid red circles and open red circles represent the class I and II siRNA data, respectively. Solid blue circles and open blue circles represent the class I and II chiRNA data, respectively. (A,D) The calculated Tm of the seed-target duplex decreased with increasing standard free energy (ΔG) for seed-target duplex formation (correlation coefficient: −0.98 and −0.91, respectively). (B,E) Luciferase activity (seed-dependent off-target gene silencing at a 50 nM siRNA concentration) was positively correlated with ΔG (correlation coefficient: 0.72 and 0.71, respectively). (C,F) The correlation between the seed-dependent gene silencing activity (luciferase activity) and the calculated Tm of the seed-target duplex. Luciferase activity based on seed-dependent gene silencing with 50 nM siRNA was obtained from Figures 4 and 7, respectively. Seed-target duplex ΔG and Tm were calculated using the nearest neighbor method. The relative luciferase activity and calculated Tm were correlated with each other and had a coefficient of −0.76 and −0.79, respectively.

Table 1.

Relative luciferase activities and Tms, ΔGs, and Kds at seed regions of class I and II siRNAs.

| Luciferase activity (% at 50 nM) | Seed region GC number | Tm 2–8 (°C) | ΔG 2–8 (kcal/mol) | Kd (M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLASS I | |||||

| siLuc-309 | 76 | 0 | −8.1 | −7.2 | 5.3 × 10−6 |

| siVIM-812 | 95 | 1 | 8.8 | −9.3 | 1.5 × 10−7 |

| siGRK4-934 | 102 | 1 | 6.7 | −9.6 | 9.2 × 10−8 |

| siOct-821 | 64 | 2 | 12.2 | −10.3 | 2.8 × 10−8 |

| siLuc-774 | 75 | 2 | 14.6 | −10 | 4.7 × 10−8 |

| siVIM-1128 | 79 | 3 | 21.2 | −12.8 | 4.1 × 10−10 |

| siLuc2-153 | 52 | 3 | 21.0 | −11.7 | 2.6 × 10−9 |

| siVIM-596 | 49 | 3 | 26.4 | −11.6 | 3.1 × 10−9 |

| siOct-797 | 29 | 3 | 25.7 | −12.4 | 8.1 × 10−10 |

| siVIM-270 | 25 | 3 | 26.2 | −12.2 | 1.1 × 10−9 |

| siLuc-36 | 49 | 4 | 28.4 | −13 | 3.0 × 10−10 |

| CLASS II | |||||

| siGRK4-189 | 9 | 4 | 40.1 | −15.5 | 4.3 × 10−12 |

| siLuc-1120 | 44 | 5 | 42.3 | −16.7 | 5.7 × 10−13 |

| siLuc-49 | 6 | 6 | 46.3 | −17.6 | 1.3 × 10−13 |

| siLuc-1048 | 30 | 6 | 49.7 | −17.8 | 8.9 × 10−14 |

| siLuc-1063 | 18 | 7 | 54.5 | −18.6 | 2.3 × 10−14 |

| siLuc-1430 | 20 | 7 | 54.5 | −18.6 | 2.3 × 10−14 |

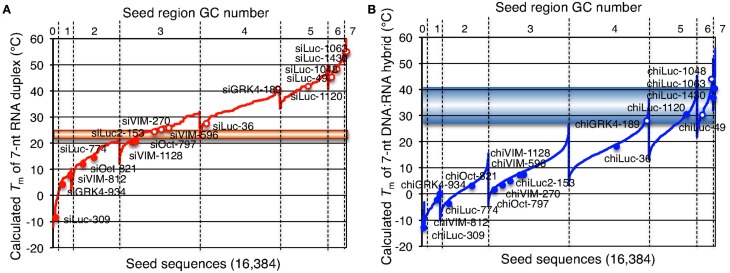

Figure 6.

Correlation between seed-dependent gene silencing activity of siRNA and chiRNA and calculated Tm of the protein-free seed duplex. Gene silencing activity was measured using relative luciferase activity in HeLa cells transfected with psiCHECK-sm and cognate siRNAs or chiRNAs at a 50 nM concentration, as shown in Figures 4 and 7. Tm of the protein-free seed region (positions 2–8) was determined using the nearest neighbor method. (A,B) All possible 7-nt seed sequences (47 = 16,384) were ordered as a function of GC content and Tm values of their double-stranded counterparts with RNA (A) and DNA (B). Note that because of its definition, class I siRNA or chiRNA cannot possess more than four GCs in the seed region. Open red (A) or blue (B) circles represent combinations of target and siRNA resulting in less than 50% relative luciferase activity. Solid red (A) or blue (B) circles represent combinations of target and siRNA with little or no off-target effect (luciferase activity >50%). The horizontal line at 21–25°C (A) or 28–41°C (B) may correspond to 50% luciferase activity reduction.

Thermodynamic Control of RNA Strand Incorporation into the Risc by Chemical Modifications

RNA strand incorporation into the RISC is determined by siRNA duplex thermodynamics. The RNA strand with lowest binding stability in the 5′ end of the guide strand is preferentially incorporated into the RISC. Thus, rational chemical modifications can be used to improve selective guide strand loading into the RISC (Table 2). High-affinity modifications [e.g., locked nucleic acid (LNA)] at the 5′ end of the passenger strand increase selective loading of the guide strand (Elmén et al., 2005). In addition, base modifications of a high-affinity 2-thiouracil base at the 3′ end of the guide strand and a low-affinity dihydrouracil base at the 3′ end of the passenger strand can be used to the same effect (Sipa et al., 2007). Furthermore, a moderately active siRNA duplex is significantly improved by modifying the high-affinity 4′-thioribonucleoside (Hoshika et al., 2007). Similarly, other modifications, such as high-affinity 5-methyluracil and 5-methylcytosine modifications (Terrazas and Kool, 2009), or low-affinity 2,4-difluorotoluene and 5-nitroindole modifications (Addepalli et al., 2010), may also control the efficiency of RISC loading.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic siRNA modification.

| Chemical modification | Nucleotide position | Modified base-pairing stability | Functional modification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNA | The 5′ end of the passenger strand | Increase the stability at 5′ end of the passenger strand | Elmén et al. (2005) | |

| 4′-Thioribonucleoside | Four residues on both ends of the passenger strand and 3′ end of the guide strand | Increase the stability at 3′ end of the guide strand | Enhancement of selective RISC loading of the guide strand | Hoshika et al. (2007) |

| 2-Thiouracil | The 3′ end of the guide strand | Increase the stability at 3′ end of the guide strand | Sipa et al. (2007) | |

| Dihydrouracil | The 3′ end of the passenger strand | Decrease the stability at 3′ end of the passenger strand | ||

| 2′-O-methyl | Position 2 of the guide strand and positions 1 + 2 of the passenger strand | The conformational alteration of RISC by the guide strand modification reduces the rate of RISC formation to dissociate off-target transcripts with weaker binding to the guide strands | Reduction of the seed-dependent off-target effect | Jackson et al. (2006b) |

| 2′-Deoxy (DNA) | Positions 1–8 of the guide strand and positions 12–21 of the passenger strand | Decrease the stability in the seed region of the guide strand | Ui-Tei et al. (2008b) |

Elimination of Seed-Dependent off-Target Effect by Chemical Modifications

The seed-dependent off-target effect is also eliminated by chemical modifications (Table 2). 2′-O-methyl modification of the guide strand seed region alters the RISC conformation and reduces seed-dependent off-target effects by dissociating off-target transcripts with weak binding to the guide strand (Jackson et al., 2006b). Low-affinity dihydrouracil base, 2,4-difluorotoluene, or 5-nitroindole modifications in the seed region may also reduce the seed-dependent off-target effects. Furthermore, we revealed that 2′-deoxy modification (DNA replacement) of nucleotides 1–8 in the guide strand and 12–21 in the passenger strand (DNA:RNA chimeric siRNA, chiRNA; Figure 3B) reduces thermodynamic stability in the seed-target duplex, and almost completely eliminates off-target effects with little or no loss of target gene silencing activity (Ui-Tei et al., 2008b). In contrast, replacing the 3′-proximal RNA sequence of the guide strand with its DNA counterpart resulted in almost complete loss of gene silencing activity of the passenger strand. As shown in Figure 7, most functional class II siRNAs could not effectively eliminate the off-target effects by DNA replacement in the seed region (Ui-Tei et al., 2009). We examined the relationship between the relative luciferase activity and the ΔG or Tm of the DNA:RNA seed duplex in 11 class I and six class II chiRNAs (Figure 5D–F). We verified a close linear relationship between ΔG and Tm in the seed region (Figure 5D), a strong positive correlation between luciferase activity and ΔG (r = 0.71) and a strong negative correlation between Tm and luciferase activity (r = −0.79), irrespective of the presence or absence of DNA replacement in the seed region (Figure 5E,F). However, DNA replacement increased ΔG and reduced both the seed-target duplex Tm and luciferase activity considerably. Tm was reduced to less than 20°C in all the class I chiRNAs, while the relative luciferase activity at 50 nM exceeded 60%, the minimum relative luciferase activity necessary for a practical off-target effect. In contrast, the relative luciferase activity at 50 nM was 30% or less in three of six cases treated with functional class II chiRNAs, even though the seed-target Tm was reduced; this demonstrates a strong negative correlation with ΔG for seed-target duplex formation (Figure 5D). Therefore, it appears that the reduced off-target effect in chiRNA-dependent gene silencing is generally attributable to a reduction in the thermodynamic stability of the DNA:RNA hybrid in the seed–target duplex. According to Tables 1 and 3, DNA replacement throughout the guide strand seed region is roughly equivalent to a 13°C reduction in Tm, a 5 kcal/mol increment in ΔG, and about two to three G/C → A/U changes in the seed duplex. In Figure 6B, Tm values of all possible 7-nt DNA:RNA hybrids are ordered and plotted against chiRNAs with or without off-target silencing activity. For DNA:RNA hybrids, 28–41°C might be a boundary line that discriminates off-target-free from off-target-positive seed sequences. However, this boundary had higher Tm values, as compared to those of RNA duplexes shown in Figure 6A. This might be partially due to different parameters used in calculating Tm values of RNA duplexes and DNA:RNA hybrids. The proportion of 7-nt DNA:RNA hybrids with Tm values under 28°C was about 88%, indicating that most 7-nt sequences are available for off-target effect-reduced RNA silencing by replacing RNA with DNA in the seed region.

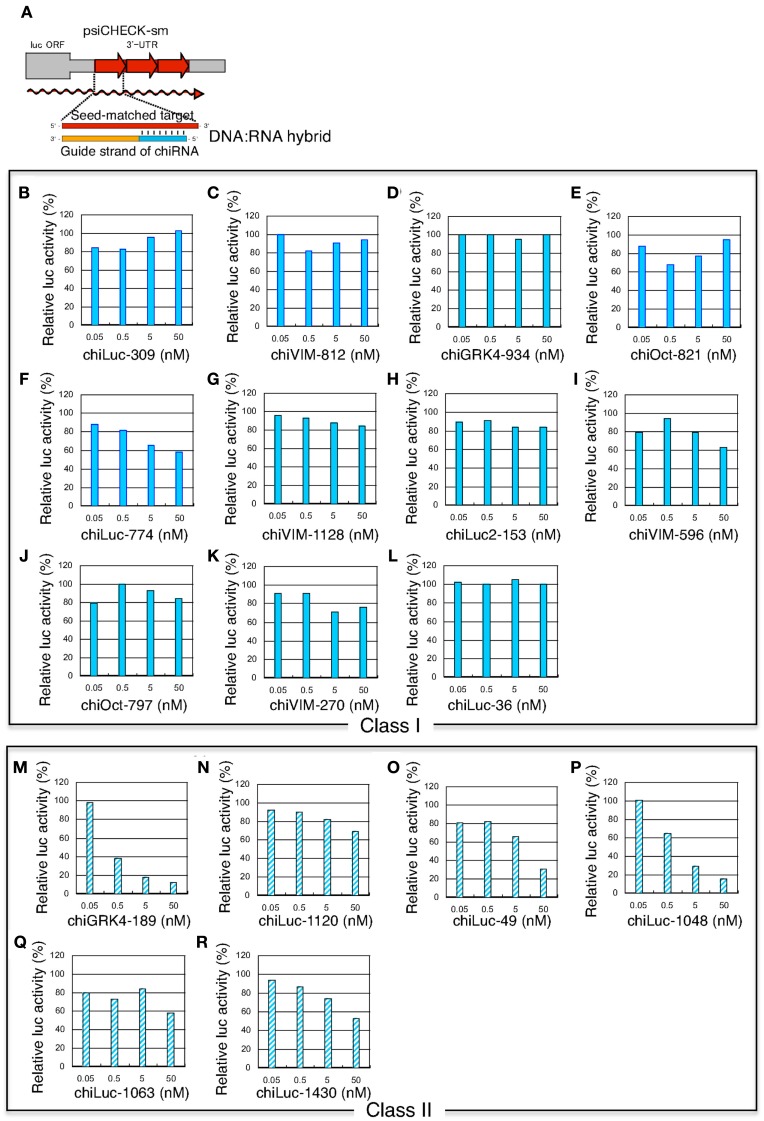

Figure 7.

Concentration-dependent gene silencing effects of DNA-seed-containing chiRNA for seed-matched targets. Both class I chiRNAs and functional class II chiRNAs were included. The gene silencing effects were examined using HeLa cells transfected with psiCHECK-sm plasmids containing various seed-matched targets. The relative luciferase (luc) activity in transfected HeLa cells was determined using a dual luciferase assay. (A) chiRNA psiCHECK-sm plasmid structures and gene silencing mechanism. Three tandem repeats of seed-matched target sequences were introduced into the region corresponding to the 3′UTR of the luciferase mRNA. In (B–R), the effects of chiRNAs transfection on seed-matched targets are shown. (B–L) class I chiRNAs, (M–R) class II chiRNAs, (B) chiLuc-309, (C) chiVIM-812, (D) chiGRK4-934, (E) chiOct-821, (F) chiLuc-774, (G) chiVIM-1128, (H) chiLuc2-153, (I) chiVIM-596, (J) chiOct-797, (K) chiVIM-270, (L) chiLuc-36, (M) chiGRK4-189, (N) chiLuc-1120, (O) chiLuc-49, (P) chiLuc-1048, (Q) chiLuc-1063, (R) chiLuc-1430. chiRNA sequences and structures are shown in Figure 3B.

Table 3.

Relative luciferase activities and Tms, ΔGs, and Kds at seed regions of class I and II chiRNAs.

| Luciferase activity (% at 50 nM) | Seed region GC number | Tm 2–8 (°C) | ΔG 2–8 (kcal/mol) | Kd (M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLASS I | |||||

| chiLuc-309 | 103 | 0 | −12.2 | −4.9 | 2.6 × 10−4 |

| chiVIM-812 | 94 | 1 | −0.5 | −5.5 | 9.3 × 10−5 |

| chiGRK4-934 | 95 | 1 | 0.2 | −5.6 | 7.3 × 10−5 |

| chiOct-821 | 95 | 2 | 4.7 | −7.1 | 6.2 × 10−6 |

| chiLuc-774 | 65 | 2 | −4.8 | −6.8 | 1.0 × 10−5 |

| chiVIM-1128 | 79 | 3 | 8.8 | −7.9 | 1.6 × 10−6 |

| chiLuc2-153 | 91 | 3 | 5.4 | −7.8 | 1.9 × 10−6 |

| chiVIM-596 | 63 | 3 | 8.8 | −7.8 | 1.9 × 10−6 |

| chiOct-797 | 84 | 3 | 1.3 | −7.8 | 1.9 × 10−6 |

| chiVIM-270 | 78 | 3 | 3.1 | −7.6 | 2.7 × 10−6 |

| chiLuc-36 | 68 | 4 | 19 | −8.0 | 1.4 × 10−6 |

| CLASS II | |||||

| chiGRK4-189 | 12 | 4 | 28.1 | −9.6 | 9.2 × 10−8 |

| chiLuc-1120 | 69 | 5 | 31.1 | −9.8 | 6.5 × 10−8 |

| chiLuc-49 | 31 | 6 | 30.4 | −11.0 | 8.6 × 10−9 |

| chiLuc-1048 | 16 | 6 | 45.2 | −9.7 | 7.7 × 10−8 |

| chiLuc-1063 | 58 | 7 | 41.4 | −12.0 | 1.6 × 10−9 |

| chiLuc-1430 | 53 | 7 | 35 | −12.0 | 1.6 × 10−9 |

Genome-Wide Analysis Revealed that siRNA with Low Stability in the Seed-Target Duplex is Capable of Inducing Target Gene-Specific Silencing

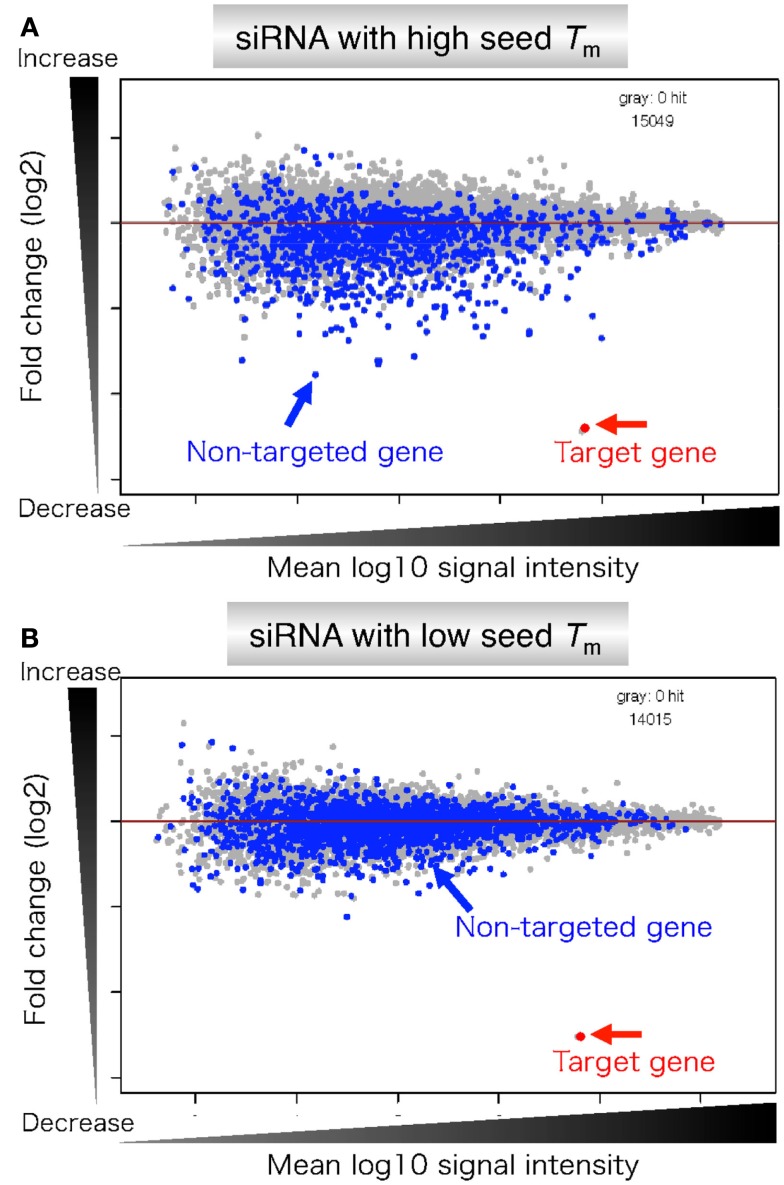

The hypothesis that off-target gene silencing is determined primarily by seed-target duplex stability was apparent in genome-wide expression profiling using class I siRNA with high or low seed Tm value (Figure 8). The reporter assay described above predicted that siRNA with high seed Tm value would be good inducer, while that with low seed Tm value would be poor inducer of the off-target effect.

Figure 8.

Microarray profiles of transcripts downregulated by transfection of siRNA with high or low stability in the seed-target duplex. (A) siRNA with high seed Tm is capable of forming stable seed duplexes with the 3′ UTR counterpart of target mRNA. (B) siRNA with low seed Tm is capable of forming unstable seed duplexes with the 3′ UTR counterpart of target mRNA. Microarray-based expression profiles were examined 24 h after transfection. Gene expression changes are shown by log 2 of fold change ratio (ordinate) relative to mock transfection. The abscissa represents transcript signal intensity (log 10). Blue and gray dots represent transcripts complementary to the seed and those with no seed complementarity, respectively. Target genes are colored red and indicated by arrows. Their expression levels were similarly reduced. The number of genes examined is shown on the upper right edge of each panel.

As anticipated, both siRNAs effectively reduced the amount of completely matched target mRNA to less than 20% as a result of intended RNAi (red arrows in Figure 8). In contrast, a high level of off-target effects was evident in the case of transfection with siRNA with high seed Tm value. Conversely, transfection with siRNA with low seed Tm value exhibited little off-target effects. Thus, it was concluded that the level of off-target gene silencing is determined by the thermodynamic stability of the seed duplex formed between the siRNA guide strand and the target mRNA.

Conclusion

In this review, we demonstrated that siRNA seed-dependent off-target effect efficiency is controlled by thermodynamic properties of the nucleotide duplex. This conclusion was drawn from the following: (1) The functional siRNA duplex is asymmetric in its terminal nucleotide base-pairing. An RNA strand with an unstable 5′ terminal is effective as a guide strand, probably because it is easily retained in the RISC. (2) The siRNA off-target effect efficacy can be determined by seed region nucleotide duplex thermodynamic properties. The seed-dependent off-target effect efficiency is positively and negatively correlated with ΔG and Tm in seed region positions 2–8. Thus, small RNA-mediated gene silencing is partly regulated by nucleotide base-pairing thermodynamic stability.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eigo Shimizu for excellent assistance in preparing Figure 6. This work was partially supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT), and the Cell Innovation Project (MEXT) to Kumiko Ui-Tei.

References

- Addepalli H., Meena Peng, C. G., Wang G., Fan Y., Charisse K., Jayaprakash K. N., Rajeev K. G., Pandey R. K., Lavine G., Zhang L., Jahn-Hofmann K., Hadwiger P., Manoharan M., Maier M. A. (2010). Modulation of thermal stability can enhance the potency of siRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 7320–7331 10.1093/nar/gkq568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarzguioui M., Prydz H. (2004). An algorithm for selection of functional siRNA sequences. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 316, 1050–1058 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel D. P. (2004). MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham A., Anderson E. M., Reynolds A., Ilsley-Tyree D., Leake D., Fedorov Y., Baskerville S., Maksimova E., Robinson K., Karpilow J., Marshall W. S., Khvorova A. (2006). 3′ UTR seed matches, but not overall identity, are associated with RNAi off-targets. Nat. Methods 3, 199–204 10.1038/nmeth0606-487a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmén J., Thonberg H., Ljungberg K., Frieden M., Westergaard M., Xu Y., Wahren B., Liang Z., Ørum H., Koch T., Wahlestedt C. (2005). Locked nucleic acid (LNA) mediated improvements in siRNA stability and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 439–447 10.1093/nar/gki193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank F., Sonenberg N., Nagar B. (2010). Structural basis for 5′-nucleotide base-specific recognition of guide RNA by human AGO2. Nature 465, 818–822 10.1038/nature09039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A., Farh K. K., Johnston W. K., Garrett-Engele P., Lim L. P., Bartel D. P. (2007). MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol. Cell 27, 91–105 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harborth J., Elbashir S. M., Vandenburgh K., Manninga H., Scaringe S. A., Weber K., Tuschl T. (2003). Sequence, chemical and structural variation of small interfering RNAs and short hairpin RNAs and the effect on mammalian gene silencing. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 13, 83–105 10.1089/108729003321629638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holen T., Amrzguioui M., Wiiger M. T., Babaie E., Prydz H. (2002). Positional effects of short interfering RNAs targeting the human coagulation trigger tissue factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 1757–1766 10.1093/nar/30.8.1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshika S., Minakawa N., Shinonoya A., Imada K., Ogawa N., Matsuda A. (2007). Study of modification pattern-RNAi activity relationships by using siRNAs modified with 4′-thioribonucleosides. Chembiochem 8, 2133–2138 10.1002/cbic.200700342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G., Simard M. J. (2008). Argonaute proteins: key players in RNA silencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 22–32 10.1038/nrm2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L., Bartz S. R., Schelter J., Kobayashi S. V., Burchard J., Mao M., Li B., Cavet G., Linsley P. S. (2003). Expression profiling reveals off-target gene regulation by RNAi. Nat. Biotechol. 21, 635–637 10.1038/nbt831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L., Burchard J., Schelter J., Chau B. N., Cleary M., Lim L., Linsley P. S. (2006a). Widespread siRNA “off-target” transcript silencing mediated by seed region sequence complementarity. RNA 12, 1179–1187 10.1261/rna.184206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson A. L, Burchard, J., Leake D., Reynolds A., Schelter J., Guo J., Johnson J. M., Lim L., Karpilow J., Nichols K., Marshall W., Khvorova A., Linsley P. S. (2006b). Position-specific chemical modification of siRNAs reduces “off-target” transcript silencing. RNA 12, 1197–1205 10.1261/rna.184206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Doudna J. A. (2009). A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature 457, 405–412 10.1038/nature07755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata T., Seitz H., Tomari Y. (2009). Structural determinants of miRNAs for RISC loading and slicer-independent unwinding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 953–960 10.1038/nsmb.1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khvorova A., Reynolds A., Jayasena S. D. (2003). Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell 115, 209–216 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00801-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuschner P. J., Ameres S. L., Kueng S., Martinez J. (2006). Cleavage of the siRNA passenger strand during RISC assembly in human cells. EMBO Rep. 7, 314–320 10.1038/sj.embor.7400637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B. P., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. (2005). Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120, 15–20 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim L. P., Lau N. C., Garrett-Engele P., Grimson A., Schelter J. M., Castle J., Bartel D. P., Linsley P. S., Johnson J. M. (2005). Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature 433, 769–773 10.1038/nature03315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Ruan X., Anderson M. G., McDowell J. A., Kroeger P. E., Resik S. W., Shen Y. (2005). siRNA-mediated off-target gene silencing triggered by a 7 nt complementation. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 4527–4525 10.1093/nar/gki623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Carmell M. A., Rivas F. V., Marsden C. G., Thomson J. M., Song J. J., Hammond S. M., Joshua-Tor L., Hannon G. J. (2004). Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science 305, 1437–1441 10.1126/science.1102513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.-B., Yuan Y. R., Meister G., Pei Y., Tuschl T., Patel D. J. (2005). Structural basis for 5′-end-specific recognition of guide RNA by the A. fulgidus piwi protein. Nature 434, 666–670 10.1038/nature03514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J., Patkaniowska A., Urlaub H., Lührmann R., Tuschl T. (2002). Single-stranded antisense siRNAs guide target RNA cleavage in RNAi. Cell 110, 563–574 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00908-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matranga C., Tomoari Y., Shin C., Bartel D. P., Zamore P. S. (2005). Passenger-strand cleavage facilitates assembly of siRNA into Ago2-containing RNAi enzyme complexes. Cell 123, 607–620 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G., Landthaler M., Patkaniowska A., Dorsett Y., Teng G., Tuschl T. (2004). Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs. Mol. Cell 15, 185–197 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi K., Tsukumo H., Nagami T., Siomi H., Siomi M. C. (2005). Slicer function of Drosophila Argonautes and its involvement in RISC formation. Genes Dev. 19, 2837–2848 10.1101/gad.1370605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds A., Leake D., Boese Q., Scaringe S., Marshall W. S., Khvorova A. (2004). Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 326–330 10.1038/nbt936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scacheri P. C., Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Caplen N. J., Wolfsberg T. G., Umayam L., Lee J. C., Hughes C. V., Shanmugam K. S., Bhattacharjee A., Meyerson M., Collins F. S. (2004). Short interfering RNAs can induce unexpected and divergent changes in the levels of untargeted proteins in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1892–1897 10.1073/pnas.0308698100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz D. S., Hutvágner G., Du T., Xu Z., Aronin N., Zamore P. D. (2003). Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell 115, 199–208 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00759-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz D. S., Hutvágner G., Haley B., Zamore P. D. (2002). Evidence that siRNAs function as guides, not primers, in the Drosophila and human RNAi pathways. Mol. Cell 10, 57–548 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00651-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipa K., Sochacka E., Kazmierczak-Baranska J., Maszewska M., Janicka M., Nowak G., Nawrot B. (2007). Effect of base modifications on structure, thermodynamic stability, and gene silencing activity of short interfering RNA. RNA 13, 1301–1316 10.1261/rna.538907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. J., Smith S. K., Hannon G. J., Joshua-Tor L. (2004). Crystal structure of Argonaute and its implications for RISC slicer activity. Science 305, 1434–1437 10.1126/science.305.5686.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas M., Kool E. T. (2009). RNA major groove modifications improve siRNA stability and biological activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 346–353 10.1093/nar/gkn958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui-Tei K., Naito Y., Nishi K., Juni A., Saigo K. (2008a). Thermodynamic stability and Watson-Crick base pairing in the seed duplex are major determinants of the efficiency of the siRNA-based off-target effect. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 7100–7109 10.1093/nar/gkn042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui-Tei K., Naito Y., Zenno S., Nishi K., Yamato K., Takahashi F., Juni A., Saigo K. (2008b). Functional dissection of siRNA sequence by systematic DNA substitution: modified siRNA with a DNA seed arm is a powerful tool for mammalian gene silencing with significantly reduced off-target effect. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2136–2151 10.1093/nar/gkn042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui-Tei K., Naito Y., Takahashi F., Haraguchi T., Ohki-Hamazaki H., Juni A., Ueda R., Saigo K. (2004). Guidelines for the selection of highly effective siRNA sequences for mammalian and chick RNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 936–948 10.1093/nar/gkh247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ui-Tei K., Nishi K., Naito Y., Zenno S., Juni A., Saigo K. (2009). “Reduced base-base interactions between the DNA seed and RNA target are the major determinants of a significant reduction in the off-target effect due to DNA-seed-containing siRNA,” in Proceedings of the 2009 Micro-NanoMechatronics and Human Science (MHS2009), Nagoya, 298–304 10.1109/MHS.2009.5351913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoda M., Kawamata T., Paroo Z., Ye X., Iwasaki S., Liu Q., Tomari Y. (2010). ATP-dependent human RISC assembly pathways. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 117–123 10.1038/nsmb.1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y.-R., Pei Y., Ma J. B., Kuryavyi V., Zhadina M., Meister G., Chen H. Y., Dauter Z., Tuschl T., Patel D. J. (2005). Crystal structure of A. aeolicus Argonaute, a site-specific DNA-guided endoribonuclease, provides insights into RISC-mediated mRNA cleavage. Mol. Cell 19, 405–419 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]