Abstract

The Short Form-12 Health Survey (SF-12) is used to assess the patient’s quality of life (QoL) using the physical component score (PCS) and the mental component score (MCS). The purpose of this study was to determine whether the SF-12 PCS and MCS are associated with psoriasis severity and to compare QoL between Murdough Family Center for Psoriasis (MFCP) patients and patients with other major chronic diseases included in the National Survey of Functional Health Status data. We used data from 429 adult patients enrolled in MFCP. Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) was used to assess psoriasis severity at the time of completion of the SF-12 questionnaire. Other variables included age, sex, body mass index, psoriatic arthritis, psychiatric disorders, and comorbidities. Linear regression models were used to estimate effect sizes ±95% confidence intervals. For every 10-point increase in PASI, there was a 1.1±1.3 unit decrease in MCS (P = 0.100) and a 2.4±1.3 unit decrease in PCS (P<0.001). Psoriasis severity was associated with PCS and MCS after adjusting for variables, although the strength of the relationship was attenuated in some models. Psoriasis severity is associated with decreased QoL. SF-12 may be a useful tool for assessing QoL among psoriasis patients.

INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies have demonstrated the significant negative impact that psoriasis has on quality of life (QoL; Finlay and Coles, 1995; Fleischer et al., 1996; De Arruda and De Moares, 2001; Krueger et al., 2001; Zachariae et al., 2002). Furthermore, as a chronic disease, psoriasis affects the QoL of both patients and their close relatives in a cumulative way (Tadros et al., 2011). Various factors may contribute to the lower QoL in psoriasis patients. The chronic nature of the disease and the lack of control over unexpected outbreaks of the symptoms are among the most bothersome aspects of psoriasis (Gelfand et al., 2004). Patients may feel humiliated when they need to expose their bodies during swimming, intimate relationships, using public showers, or living in conditions that do not provide adequate privacy (Fortune et al., 2005). Psoriasis affects patients’ social life, daily activities, occupational, and sexual functioning (Weiss et al., 2002). People suffering from psoriasis feel that the general public and sometimes their own physicians fail to appreciate the negative impact of psoriasis on their life (Stern et al., 2004). Treatment of psoriasis, as it may add a substantial financial burden to patients and may be associated with risks for adverse effects, is also an important component of the QoL of psoriasis patients (Feldman et al., 1997). Although the impact of psoriasis on QoL may decrease over time regardless of the treatment of the disease (Unaeze et al., 2006), improving the QoL of psoriasis patients is a desirable and attainable goal. Therefore, the interventions to improve the process of care for this population often assess QoL outcomes such as social functioning, overall health status, and emotional well-being. These outcomes may be affected by coexisting chronic conditions and it is therefore important to adjust for these effects.

Various measures have been used to assess QoL in psoriasis patients, each of them emphasizing a different aspect of the disease that may or may not incorporate the impact of psoriasis comorbidities (Bronsard et al., 2010). Usually, generic measures are used to compare outcomes across different populations and interventions, particularly for cost-effectiveness studies. Disease-specific measures assess the special states and concerns of diagnostic groups. Specific measures may be more sensitive for the detection and quantification of small changes that are important to clinicians or patients (Patrick and Deyo, 1989). By utilizing the Short Form-36 (SF-36), a generic QoL instrument, it has been demonstrated that psoriasis may cause as much disability as other major medical diseases, including cancer, arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and depression (Rapp et al., 1999).

We sought to determine whether the Short Form-12 (SF-12), a shorter, yet valid alternative to the SF-36 (Ware et al., 2002), whose 12 questions are all selected from the SF-36, might be useful in assessing the QoL of psoriasis patients. The purpose of this study was to determine whether the SF-12 physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS) are associated with psoriasis severity and to compare QoL between Murdough Family Center for Psoriasis (MFCP) patients and patients with other major chronic diseases included in the National Survey of Functional Health Status (NSFHS) data.

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis

Summary of the descriptive statistics for variables of interest is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for variables of interest in the sample of chronic plaque psoriasis patient

| Continuous variables | Available sample size | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 429 | 48.7 | 15.4 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 429 | 30.4 | 7.5 |

| PASI | 429 | 8.0 | 9.2 |

| Comorbidities (number) | 429 | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| PCS | 429 | 45.6 | 12.5 |

| MCS | 429 | 47.5 | 12.2 |

| DLQI | 162 | 8.7 | 7.0 |

| Categorical variables | Number | Available sample size | Percent |

| Males | 231 | 429 | 54% |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 111 | 425 | 26% |

| Psychiatric disorder | 142 | 429 | 33% |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated by the ratio between weight in kilograms and the square of height in meters; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; MCS, mental component score; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PCS, physical component score.

The mean values of SF-12 scores for the present sample were compared with the mean values from the 1998 National Survey of Functional Health Status data (Ware et al., 2002). A qualitative comparison of the scores revealed that psoriasis patients had MCSs that were similar to those of patients with heart disease, chronic allergies, hearing impairment, osteoarthritis, back pain or sciatica, dermatitis, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer, whereas they had PCSs that were similar to those of patients with back pain or sciatica, dermatitis, depression, anemia, and vision or hearing impairment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mental and physical component scores of psoriasis patients compared with general US populations, including healthy adults and those with chronic diseases

| MCS

|

PCS

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Rank | Mean (SD) | Rank | |

| Healthy adults | 52.3 (7.9) | 1 | 54.3 (6.2) | 1 |

| General US population | 49.4 (9.8) | 2 | 49.6 (9.9) | 2 |

| Hypertension | 49.1 (9.5) | 3 | 43.7 (10.3) | 10 |

| Chronic allergies | 48.6 (10.0) | 4 | 49.4 (10.0) | 3 |

| Heart disease | 48.3 (10.1) | 5 | 38.8 (10.0) | 17 |

| Hearing impairment | 48.0 (9.9) | 6 | 44.7 (10.4) | 9 |

| Psoriasis (MFCP database) | 47.5 (12.2) | 7 | 45.6 (12.5) | 6 |

| Osteoarthritis/degenerative arthritis | 47.5 (10.2) | 7 | 38.9 (10.1) | 16 |

| Back pain or sciatica | 47.4 (10.5) | 8 | 46.0 (11.0) | 5 |

| Dermatitis | 47.3 (10.5) | 9 | 47.8 (10.8) | 4 |

| Diabetes | 47.3 (10.7) | 9 | 41.5 (11.1) | 13 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 47.2 (10.3) | 10 | 40.6 (10.5) | 15 |

| Cancer (except skin cancer) | 47.1 (10.1) | 11 | 40.8 (10.0) | 14 |

| Vision impairment | 45.7 (11.2) | 12 | 44.1 (11.2) | 8 |

| Lung disease | 45.6 (10.7) | 13 | 38.3 (10.5) | 18 |

| Kidney disease | 45.2 (10.1) | 14 | 37.9 (11.2) | 19 |

| Ulcer or stomach disease | 45.1 (11.3) | 15 | 43.2 (11.6) | 11 |

| Anemia | 44.8 (11.00) | 16 | 45.5 (11.9) | 7 |

| Liver disease | 44.1 (12.9) | 17 | 42.0 (12.1) | 12 |

| Depression | 37.4 (10.8) | 18 | 45.6 (11.7) | 6 |

Abbreviations: MCS, mental component score; MFCP, Murdough Family Center for Psoriasis; PCS, physical component score.

Unadjusted associations of variables with SF-12

Unadjusted associations of variables with SF-12 are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Unadjusted associations of variables with SF-12

| N | MCS

|

PCS

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect1 (CI) | P-value | Effect1 (CI) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | 429 | 0.13 (0.06, 0.21) | <0.001 | −0.23 (−0.31, −0.16) | <0.001 |

| Gender (males) | 429 | 3.14 (0.84, 5.45) | 0.008 | 3.08 (0.71, 5.44) | 0.011 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 429 | 0.10 (−0.05, 0.25) | 0.206 | −0.47 (−0.63, −0.32) | <0.001 |

| PASI (10-point change) | 429 | −1.1 (−2.3, 0.2) | 0.100 | −2.4 (−3.7, −1.1) | <0.001 |

| PsA | 425 | 0.04 (−2.60, 2.69) | 0.976 | −6.86 (−9.49, −4.23) | <0.001 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 429 | −9.16 (−11.46, −6.86) | <0.001 | −4.10 (−6.59, −1.61) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidites (number) | 429 | −0.48 (−1.12, 0.16) | 0.138 | −3.40 (−3.97, −2.83) | <0.001 |

| DLQI | 162 | −0.53 (−0.78, −0.29) | <0.001 | −0.50 (−0.74, −0.26) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated by the ratio between weight in kilograms and the square of height in meters; CI, confidence interval; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; MCS, mental component score; PCS, physical component score; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SF-12, the Short Form-12 Health Survey.

Effect indicates the estimated average change in MCS or PCS associated with a unit change in the covariate.

On average, older subjects felt worse physically but better mentally. Men reported higher PCS and MCS compared with women. Increased body mass index was associated with decreased physical health component, whereas it was not associated with mental health component. It was evident that Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) was associated with low mental health, although the P-value did not show statistical significance: for every 10-point increase in PASI, there was an associated 1.1±1.3 unit decrease in MCS (P = 0.100). PASI was associated with low physical health: for every 10-point increase in PASI, there was an associated 2.4±1.3 unit decrease in PCS (P<0.001). On average, subjects who had psoriatic arthritis (PsA) reported worse physical well-being but not worse mental well-being. Psychiatric conditions and other comorbidities were associated with decreased QoL: for each additional comorbidity, there was an associated 3.40±0.57 unit decrease in PCS (P<0.001) and an associated 0.48±0.64 unit decrease in MCS (P = 0.138). Worse QoL measured by Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was associated with worse overall QoL measured by SF-12 physical and MCSs.

Adjusted associations of PASI with SF-12

Adjusted associations of PASI with SF-12 MCS

After adjusting for age, gender, and body mass index, the effect of PASI on MCS was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.017). Additional adjustment for PsA, psychiatric disorders, or comorbidities did not change this result. The observed size of the effect of PASI on MCS was similar for the set of models considered (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adjusted associations of PASI with SF-12 MCS and PCS

| Other covariates | N | MCS

|

PCS

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of 10-point PASI change (CI) | P-value | Effect of 10-point PASI change (CI) | P-value | ||

| None | 429 | −1.1 (−2.3, 0.2) | 0.100 | −2.4 (−3.7, −1.1) | <0.001 |

| Age+gender+BMI | 429 | −1.5 (−2.8, −0.3) | 0.017 | −2.1 (−3.3, −0.9) | <0.001 |

| Age+gender+BMI+PsA | 425 | −1.5 (−2.8, −0.2) | 0.025 | −1.5 (−2.8, −0.3) | 0.015 |

| Age+gender+BMI+psychiatric disorder | 429 | −1.0 (−2.2, 0.2) | 0.097 | −1.9 (−3.1, −0.7) | 0.002 |

| Age+gender+BMI+comorbidity | 429 | −1.3 (−2.6, −0.1) | 0.038 | −1.6 (−2.8, −0.5) | 0.004 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated by the ratio between weight in kilograms and the square of height in meters; CI, confidence interval; MCS, mental component score; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PCS, physical component score; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SF-12, the Short Form-12 Health Survey.

Adjusted associations of PASI with SF-12 PCS

For the outcome of PCS, adjusting for age, gender, and body mass index did not change the association of PASI with PCS (Table 4). Adjusting additionally for psychiatric disorders also did not change the relationship very much. However, PsA and comorbidities were confounders accounting for the greatest decrease of the association of PASI with PCS (Table 4).

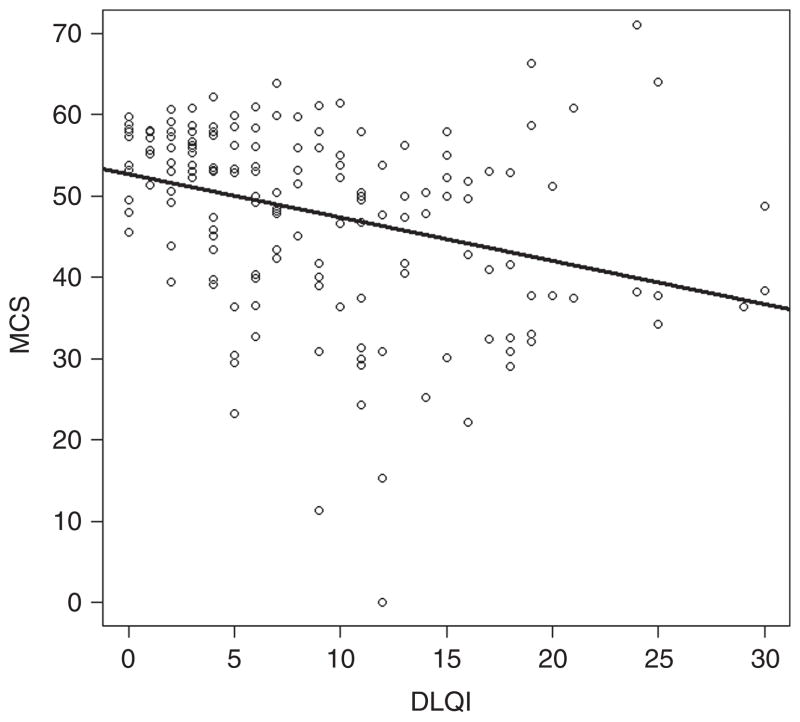

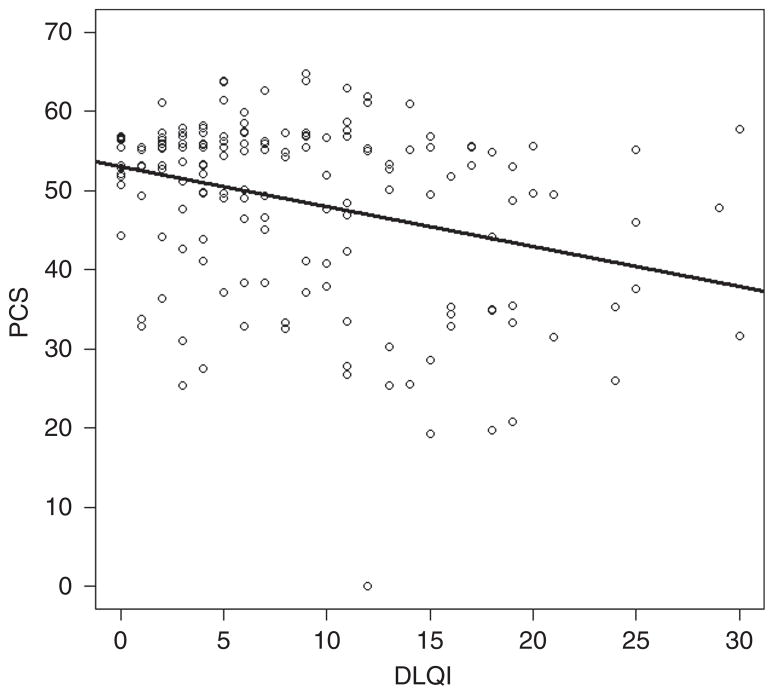

Association of DLQI with SF-12

We found a statistically significant association of DLQI with SF-12: for every unit increase in DLQI, there was an associated 0.50±0.24 unit decrease in the physical component of SF-12 (P<0.001), as well as an associated 0.53±0.25 unit decrease in the mental component of SF-12 (P<0.001; Table 3). Although statistically significant, this association was weak (correlation coefficient of −0.33 for DLQI versus MCS, and correlation coefficient of −0.31 for DLQI versus PCS; Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Associations of DLQI with SF-12.

Plot of the association between DLQI and MCS (correlation coefficient −0.33). DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; MCS, mental component score; SF-12, the Short Form-12 Health Survey.

Figure 2. Associations of DLQI with SF-12.

Plot of the association between DLQI and PCS (correlation coefficient −0.31). DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PCS, physical component score; SF-12, the Short Form-12 Health Survey.

DISCUSSION

This study extends research on the impact of psoriasis on QoL by introducing the SF-12 tool. Previously, the SF-12 has been used in dermatology to assess health values (utilities) from the general public for health states common to people with PsA and scleroderma for economic evaluations (Khanna et al., 2010). We have used the SF-12 to assess the physical and mental components of QoL of patients with chronic plaque psoriasis.

Comparative impact of psoriasis on QoL

As a generic QoL measure, the SF-12 provides an opportunity to compare the impact of psoriasis on QoL with the impact of other chronic conditions, as well as with the QoL of a normal population. Our results confirm that psoriasis has a negative impact on QoL, outlining its place among 18 other chronic medical conditions (Table 2). These findings are consistent with a previous study that used SF-36 and compared it with 1990 National Survey of Functional Health Status data (Rapp et al., 1999). In that study, it was demonstrated that the mean values of MCSs for patients with psoriasis were lower than those for patients with heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. Regarding the PCSs, only patients with congestive heart failure had lower scores than psoriasis patients. However, it should be noted that 51% of the patients with psoriasis in that study had arthritis (type undefined) as compared with 26% of our patients having PsA. Although our SF-12 physical and MCS results did not place psoriasis among the lowest groups of chronic medical conditions, our results did show that psoriasis had a negative impact on QoL comparable to the impact of other major medical and psychiatric diseases.

Impact of psoriasis severity on the mental and physical component of QoL

Because psoriasis severity is associated with MCS, perhaps patients with psoriasis need to have the severity of their disease addressed not only by the more traditional physical measures but also by determining the impact of the disease on patients’ mental functioning.

PsA and other comorbidities were potential confounders, revealing a smaller effect of PASI on PCS than it was suggested without adjusting for them; hence, the SF-12 results should be interpreted with caution in psoriasis patients as psoriasis is commonly associated with PsA and with other comorbidities. Our findings support the concept that psoriasis severity should include both physical and psychosocial measures of severity (Nichol et al., 1996; Kirby et al., 2001; Bhosle et al., 2006). Measures such as PASI, which include only a physical component, might be reinforced by a more global assessment of psoriasis disease severity. It is appropriate to include QoL assessment in the treatment decision-making process as well (Feldman et al., 2005).

We confirm previously reported results that age is negatively associated with measures of physical functioning but is positively correlated with mental functioning scores (Stern et al., 2004; Jankovic et al., 2011): older patients feel physically worse, but mentally better. This finding is intriguing as medical comorbidities and functional deficits typically increase with age, leading to limited physical abilities in the elderly.

Association of DLQI and SF-12

It has been previously demonstrated that capturing patient-reported outcomes is important in clinical trials of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (Shikiar et al., 2006). Although the DLQI provides the most reliable measure of clinical change, the SF-36 and the EuroQOL-5D (EQ-5D) generic tools performed well as general measures of health status outcomes (Tadros et al., 2011). The DLQI is useful as a QoL measure in skin-specific settings and our study shows the SF-12 to be useful as well. The existence of patients with poor PCS/MCS and good DLQI is what we would expect to see given the weak correlation between these two tools. However, as the DLQI and the SF-12 are not highly correlated, we believe that these two tools measure different aspects of QoL. We therefore suggest that it may be prudent to use two different tools to assess QoL among psoriasis patients (for example, the DLQI or another skin-specific instrument, as well as SF-12, SF-36, or another generic instrument).

Strengths and limitations

A potential limitation of the study is the use of a convenience rather than a random sample. The specific contribution of this work is that we show the advantage of the SF-12 over the widely used generic SF-36 because it is shorter, takes less time to be filled out than the SF-36, and gives information as valid as that of the SF-36.

Conclusions

Psoriasis has a negative impact on the patient’s QoL, similar to the impact of other major chronic diseases. The impact of the disease on the mental and physical functions of patients is greater in those with more severe disease. Presence of PsA, psychiatric disorders, and other comorbidities should be taken into account when assessing the impact of psoriasis severity on patients’ QoL. The SF-12 may be a useful tool for assessing QoL among psoriasis patients, along with disease-specific tools such as DLQI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The data were derived from the MFCP database, a questionnaire-based survey approved by the Institutional Review Board of University Hospitals, Cleveland. Any patient of any age with chronic plaque psoriasis was eligible to enter the database. All patients were derived either from routine dermatology clinics at the University Hospitals Case Medical Center or from community-based dermatology practices in northeast Ohio. The MFCP database questionnaire has five distinct sections, including general information, personal psoriasis and medical history, family medical history, health-related QoL self-reported measurements such as SF-12 and DLQI, and data derived from physical examination including PASI, body surface area, blood pressure, height, and weight. A total of 429 chronic plaque psoriasis patients have completed the MFCP database questionnaire since its inception in 2007.

Measures

Original Short Form-12 Health Survey (SF-12)

The SF-12, a compact 12-item one-page self-reported questionnaire, provides easily interpretable scales for physical and mental health. All “SF” forms measure the same eight domains of health: physical functioning, role functioning related to physical status, body pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role functioning related to emotional status, and mental health. The eight dimensions of the SF-12 can be combined into two summary scores, the PCS and the MCS. PCS and MCS range from 0 to 100, where zero indicates the lowest level of health and 100 indicates the highest level of health. Both PCS and MCS are scored in such a way that they compare to a national norm with a mean score of 50.0 and a standard deviation of 10.0. The SF-12 has been developed, tested, and validated by Quality Metric Incorporated (Ware et al., 2002).

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)

The DLQI is a skin-specific compact self-reported questionnaire to measure QoL over the previous week in patients with skin diseases. It consists of 10 items covering symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationships, and treatment. Each item is scored on a four-point scale with scores ranging from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating higher levels of QoL (Finlay and Khan, 1994).

Psoriasis severity

Psoriasis disease severity was assessed using the PASI measured at the time of completion of the SF-12 questionnaire.

Outcomes and variables

Our hypothesis was that QoL would be worse for patients with the most severe form of psoriasis and would be better for those with milder psoriasis and that the SF-12 would be able to measure these differences. Variables that we adjusted for included age, gender, and body mass index. We also adjusted for the following: evidence of PsA, which was defined by self-reported diagnosis of PsA and confirmed by a rheumatologist; the presence of psychiatric disorders, which was defined by a self-reported diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or obsessive compulsive disorder, which was confirmed either by a psychiatrist or by the use of psychiatric medications (including antidepressant or antianxiety agents); and for the number of medical comorbidities, which was defined by the Charlson comorbidity index, a validated index to measure the burden of comorbidity calculable from the self-reported data in the MFCP database (Charlson et al., 1987; Katz et al., 1996).

Statistical analysis

Simple and multivariable linear regression models were used to estimate effect sizes and their 95% confidence intervals.

Acknowledgments

Ivan Grozdev, Douglas Kast, and Diana Carlson were supported by the Murdough Family Center for Psoriasis Fellowships.

Abbreviations

- DLQI

Dermatology Life Quality Index

- MCS

mental component score

- PASI

Psoriasis Area Severity Index

- PCS

physical component score

- PsA

psoriatic arthritis

- QoL

quality of life

- SF-12

the Short Form-12 Health Survey

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Bhosle MJ, Kulkarni A, Feldman SR, et al. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:35. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronsard V, Paul C, Prey S, et al. What are the best outcome measures for assessing quality of life in plaque type psoriasis? A systematic review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(Suppl 2):17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Arruda LH, De Moares AP. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:33–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.144s58033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM, et al. The economic impact of psoriasis increases with psoriasis severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:564–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SR, Koo JY, Menter A, et al. Decision points for the initiation of systemic treatment for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AY, Coles EC. The effect of severe psoriasis on the quality of life of 369 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:236–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb05019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology life quality ondex (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer AB, Jr, Feldman SR, Rapp SR, et al. Disease severity measures in a population of psoriasis patients: the symptoms of psoriasis correlate with self-administered psoriasis area severity index scores. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:26–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12297659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune DG, Richards HL, Griffiths CE. Psychologic factors in psoriasis: consequences, mechanisms, and interventions. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:681–94. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand JM, Feldman SR, Stern RS, et al. Determinants of quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a study from the US population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:704–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic S, Raznatovic M, Marinkovic J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patient with psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15:29–36. doi: 10.2310/7750.2010.10009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JN, Cjang LC, Sangha O, et al. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna D, Frech T, Khanna PP, et al. Valuation of scleroderma and psoriatic arthritis health states by the generic public. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:112. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby B, Richards HL, Woo P, et al. Physical and psychologic measures are necessary to assess overall psoriasis severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:72–6. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, et al. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol MB, Margolies JE, Lippa E, et al. The application of multiple quality-of-life instruments in individuals with mild-to-moderate psoriasis. Pharmacoeconomics. 1996;10:644–53. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199610060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DL, Deyo RA. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care. 1989;27(3 Suppl):S217–32. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, et al. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikiar R, Willian MR, Okun MM, et al. The validity and responsiveness of three quality of life measures in the assessment of psoriasis patients: results of a phase II study. Health Qual Life Measures. 2006;4:71. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern RS, Nijsten T, Feldman SR, et al. Psoriasis is common, carries a substantial burden even when not extensive, and is associated with widespread treatment dissatisfaction. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:136–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros A, Vergou T, Stratigos A, et al. Psoriasis: is it the tip of the iceberg for the quality of life of patients and their families? Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1282–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unaeze J, Nijsten T, Murphy A, et al. Impact of psoriasis on health-related quality of life decreases over time: an 11-year prospective study. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:1480–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al., editors. User’s Manual for the SF-12v2 Health Survey with a Supplement Documenting SF-12 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Incorporated; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SC, Kimball AB, Liewehr DJ, et al. Quantifying the harmful effect of psoriasis on health-related quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:512–8. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae R, Zachariae H, Blomqvist K, et al. Quality of life in 6497 Nordic patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:1006–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]