Abstract

Gas embolic lesions linked to military sonar have been described in stranded cetaceans including beaked whales. These descriptions suggest that gas bubbles in marine mammal tissues may be more common than previously thought. In this study we have analyzed gas amount (by gas score) and gas composition within different decomposition codes using a standardized methodology. This broad study has allowed us to explore species-specific variability in bubble prevalence, amount, distribution, and composition, as well as masking of bubble content by putrefaction gases. Bubbles detected within the cardiovascular system and other tissues related to both pre- and port-mortem processes are a common finding on necropsy of stranded cetaceans. To minimize masking by putrefaction gases, necropsy, and gas sampling must be performed as soon as possible. Before 24 h post mortem is recommended but preferably within 12 h post mortem. At necropsy, amount of bubbles (gas score) in decomposition code 2 in stranded cetaceans was found to be more important than merely presence vs. absence of bubbles from a pathological point of view. Deep divers presented higher abundance of gas bubbles, mainly composed of 70% nitrogen and 30% CO2, suggesting a higher predisposition of these species to suffer from decompression-related gas embolism.

Keywords: gas emboli, decompression, putrefaction, gas-off, marine mammals, nitrogen, strandings

Introduction

Marine mammals moved from land to water around 55–60 million years ago (Ponganis et al., 2003). Marked anatomical and physiological modifications were necessary to meet the physical demands of living in water instead of air (Williams and Worthy, 2002). These required variations include adaptations for breath-hold diving, temperature regulation in cold water, water, and salt balance, underwater navigation, and high pressure at great depth (Elsner, 1999).

Marine mammals have not been considered to suffer from decompression sickness (DCS) because of anatomical, physiological, and behavioral adaptations that help them to prevent gas bubble formation. More specifically compression of the respiratory system together with blood-flow changes during the dive would limit the amount of nitrogen absorbed on a dive (Scholander, 1940; Butler and Jones, 1997; Kooyman and Ponganis, 1998; Fahlman et al., 2006). Compression of the respiratory system was suggested to force the air into the upper airways where no gas exchange should take place, therefore it was assumed that the finite volume of gas available in the lung would not be sufficient to increase the tissue and blood inert gas tension. Finally, partial pressure of nitrogen in the blood would decrease as nitrogen is distributed among tissues (Piantadosi and Thalmann, 2004).

In human breath-hold divers, nitrogen accumulates in tissues as pulmonary nitrogen partial pressure (PN2) increases with depth. If the surface interval between repeated dives is insufficient to remove the inert gas, nitrogen accumulation will occur (Ferrigno and Lundgren, 2003). A causal relationship between breath-hold diving in humans and DCS is only slowly being accepted despite the growing number of cases of DCS-like symptoms in breath-hold diving humans (Schipke et al., 2006). Some of these symptoms might include vertigo, visual disturbances, unconsciousness, and partial or complete paralysis of one or more extremity that could be temporary or permanent. When these symptoms respond to recompression, the most reasonable explanation is the presence of bubbles due to gas phase separation in the body (Paulev, 1965). It has been generally assumed that the risk of DCS is virtually zero during a single breath-hold dive in humans, however DCS has also been reported (although unusual) in 2 out of 192 deep single breath-hold dives (Fitz-Clarke, 2009). Diagnosis of both cases was based on DCS symptoms and recovery after treatment in a hyperbaric chamber.

Recent work has suggested that the depth of lung compression is not the same for all marine mammals species (Moore et al., 2011) and one suggested reason is because of anatomical differences of the thorax and even of the lung airways (Belanger, 1940; Denison and Kooyman, 1973; Kooyman, 1973). Indirect measurements of nitrogen uptake and removal have suggested that alveolar collapse occurs at between 30 m (Falke et al., 1985) in the Weddell seals and 70 m in the bottlenose dolphins (Ridgway and Howard, 1979). However, the physiological assumptions used in these studies are suspect (Bostrom et al., 2008) and direct measurements in seals and sea lions suggest that alveolar collapse and cessation of gas exchange may not happen until depths greater than 100 m (Kooyman and Sinnett, 1982).

Moreover, intramuscular nitrogen levels as great as two to three times the normal surface levels have been measured in voluntary diving bottlenose dolphins after repeated short duration dives to 100 m depth (Ridgway and Howard, 1979). Moore et al. (2009) described a high prevalence of bubble lesions in bycaught seals and dolphins trapped at depth (15 out of 23) compared to stranded marine mammals (1 out of 41), probably due to off gassing from supersaturated tissues. In addition, several theoretical studies have predicted end-dive nitrogen levels for marine mammals that would cause a significant proportion of DCS cases in land mammals (Houser et al., 2001; Zimmer and Tyack, 2007; Hooker et al., 2009).

In the last 8 years, an increasing number of studies have reported lesions related to in vivo bubbles. Systemic venous gas emboli were first described in an atypical beaked whale (BW) mass stranding related to military maneuvers that occurred in the Canary Islands in 2002. BWs (8 out of 8) presented acute lesions consistent with acute trauma due to in vivo bubble formation (Jepson et al., 2003; Fernandez et al., 2005). Chronic gas bubble lesions were also reported in single strandings of Risso’s dolphin (3 out of 24), common dolphins (3 out of 342), harbor porpoises (1 out of 1035), and in a Blainville’s BW (1 out of 1) stranded in the United Kingdom (Jepson et al., 2003, 2005). Further gas analyses from one Cuvier’s BW stranded along the Spanish coastline in temporal and spatial association with military (naval) exercises and one UK-stranded Risso’s dolphin with chronic gas embolic lesions in the spleen, have confirmed high nitrogen content, of around 95% in the Risso’s dolphin case (Bernaldo de Quirós et al., 2011). Additionally, dysbaric osteonecrosis (a chronic pathology of deep diving recognized in humans) has been described in sperm whales (Moore and Early, 2004). Finally, a recent publication showed the existence of intravascular bubbles and peri-renal subcapsular emphysema (gas found beneath the kidney capsule) in live stranded dolphins using a B-mode ultrasound (Dennison et al., 2012).

Given these recent observations, it is valuable to review the diving behavior of cetaceans. Some species of BWs have dive profiles not previously observed in other marine mammals such as very deep foraging dives (up to 2000 m and as long as 90 min), and relatively slow controlled ascents followed by a series of bounce dives of 100–400 m (Hooker and Baird, 1999; Tyack et al., 2006). These diving profiles are considered as extreme dives and alterations of these dive sequences by a behavioral response might induce excessive nitrogen supersaturation driving growth of bubbles in a manner similar to DCS in humans (Cox et al., 2006). Indeed, it was in BWs stranded in spatiotemporal concordance with military maneuvers when the “gas bubble lesions” were described for the first time (Jepson et al., 2003; Fernandez et al., 2005). Authors suggested a DCS-like disease as a plausible mechanism for explaining the observed lesions. These findings have been widely discussed since then and have become a scientific controversy. Further investigations, including analysis of gas in bubbles were recommended (Piantadosi and Thalmann, 2004).

Here we present a comprehensive study of prevalence, amount, distribution, and composition of intravascular bubbles and subcapsular emphysema found in cetaceans stranded on the Canary Islands coast, Spain, with different decomposition codes. The waters of the Canary Islands are one of the richest and most diverse areas in the Northeast Atlantic, with 28 different cetacean species reported, 21 of the Odontocete and 7 of the Mysticete group. Of these 28 species, at least 26 have been found stranded on the coasts of the Canary Islands (Martin et al., 2009). The high biodiversity, including both shallow and deep diving species, make the Canary Islands an excellent natural laboratory for the study of gas emboli in cetaceans with different diving behaviors.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Animals included in the study were stranded cetaceans in the Canary Islands between 2006 and 2010, mass stranded sperm whales in Italy in 2009, and two sea lions (Otaria byronia) from aquatic-parks of the Canary Islands submitted for necropsy to our institution. A total of 88 necropsies were performed on marine mammals belonging to 18 different species. Species were segregated into two broad groups: deep divers and non-deep divers, defining deep divers as those species known to dive deeper than 500 m for foraging (Kogia, Physeter, Ziphius, Mesoplodon, Globicephala, and Grampus; Gannier, 1998; Astruc and Beaubrun, 2005; Aguilar de Soto, 2006; Tyack et al., 2006; Watwood et al., 2006; West et al., 2009). These genera were further studied separately except for Ziphius and Mesoplodon, which were studied together as the family Ziphiidae. Twenty-nine out of 88 (33%) necropsied animals were deep divers.

Animals were identified by their stranding codes, represented by CET (“cetacean”) followed by the stranding number. Animals not stranded in the Canary Islands were identified by their investigation numbers, represented by I (“investigation”) followed by their corresponding numbers and the year when their necropsies were performed (Table 1). Cause(s) of death (defined as pathological entities) were determined by the Division of Histology and Animal Pathology of the Institute for Animal Health, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC; Unit of Cetaceans Research, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010; Arbelo, 2007; Table 1).

Table 1.

Identification number of the marine mammals included in the study, biological information, stranding circumstances, storing conditions, decomposition code, and most likely (*) cause of dead established by individual pathological studies.

| Identification number | Species | Deep diver | Gender | Age | Active stranding | Mass stranding | Frozen | Decomposition code | Cause of dead* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CET 339 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | Yes | F | Adult | Yes | No | No | 2 | Septicemia |

| CET 360 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | Yes | M | Calve | Yes | No | No | 1 | Infectious meningitis |

| CET 361 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | Yes | ND | Adult | No | No | No | 5 | Trauma |

| CET 362 | Stenella frontalis | No | F | Adult | Yes | No | No | 1 | Septicemia |

| CET 363 | Stenella frontalis | No | F | Subadult | ? | No | Yes | 2 | Obstruction by foreign body |

| CET 364 | Delphinus delphis | No | M | Subadult | No | No | Yes | 3 | Infectious meningoencephalitis |

| CET 367 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Calve | No | No | Yes | 5 | Abnormal development |

| CET 368 | Stenella frontalis | No | M | Juvenile | ? | No | Yes | 3 | Trauma |

| CET 369 | Balaenoptera physalus | No | F | Adult | No | No | No | 4 | Trauma |

| CET 370 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Adult | Yes | No | No | 3 | Septicemia |

| CET 371 | Stenella frontalis | No | F | Adult | ? | No | No | 2 | Trauma |

| CET 372 | Balaenoptera borealis | No | F | Subadult | No | No | No | 5 | Not determined |

| CET 373 | Delphinus delphis | No | F | Adult | Yes | No | No | 2 | Septicemia |

| CET 374 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Adult | No | No | No | 3 | Trauma |

| CET 375 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Neonate | No | No | Yes | 3 | Neonatal weakness |

| CET 376 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Adult | No | No | Yes | 2 | Neoplasia |

| CET 379 | Mesoplodon bidens | Yes | M | Adult | ? | No | No | 2 | Trauma, Septicemia |

| CET 380 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Subadult | ? | No | No | 2 | Infectious encephalitis |

| CET 381 | Delphinus delphis | No | M | Subadult | No | No | Yes | 4 | Infectious encephalitis |

| CET 382 | Delphinus delphis | No | M | Adult | ? | No | No | 3 | Sinusitis and meningoencefalitis by Nasitrema sp. |

| CET 384 | Stenella frontalis | No | M | Adult | No | No | Yes | 3 | Toxoplasmosis |

| CET 390 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | Yes | M | Calve | ? | No | No | 3 | Septicemia |

| CET 393 | Stenella frontalis | No | F | Adult | ? | No | No | 2 | Neoplasia |

| CET 395 | Stenella frontalis | No | M | Adult | No | No | Yes | 2 | Neoplasia |

| CET 397 | Kogia breviceps | Yes | F | Adult | No | No | No | 3 | Trauma, septicemia |

| CET 399 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | Yes | M | Neonate | No | No | No | 5 | Trauma |

| CET 400 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Adult | No | No | No | 2 | Parasitoses, senile disease |

| CET 402 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Adult | No | No | No | 5 | Septicemia, senile disease |

| CET 404 | Kogia breviceps | Yes | M | Adult | Yes | No | No | 1 | Encephalopathy of unknown etiology |

| CET 409 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Subadult | No | No | Yes | 3 | Infectious encephalitis, Parasitoses |

| CET 413 | Pseudorca crassidens | No | M | Juvenile | Yes | No | No | 2 | Trauma, septicemia |

| CET 418 | Stenella frontalis | No | F | Adult | ? | No | Yes | 2 | Heart failure |

| CET 419 | Steno bredanensis | No | F | Juvenile | No | No | Yes | 2 | Septicemia |

| CET 421 | Stenella frontalis | No | M | Calve | No | No | Yes | 2 | Not determined |

| CET 425 | Delphinus delphis | No | F | Juvenile | No | No | Yes | 4 | Parasitoses |

| CET 430 | Steno bredanensis | No | F | Subadult | No | No | No | 4 | Not determined |

| CET 431 | Grampus griseus | Yes | M | Juvenile | Yes | No | No | 2 | Infectious meningitis |

| CET 434 | Steno bredanensis | No | M | Adult | No | Yes | No | 5 | Not determined |

| CET 435 | Stenella frontalis | No | F | Adult | No | No | No | 5 | Trauma |

| CET 437 | Steno bredanensis | No | F | Adult | No | Yes | No | 5 | Not determined |

| CET 438 | Steno bredanensis | No | F | Subadult | No | No | No | 5 | Not determined |

| CET 456 | Grampus griseus | Yes | F | Adult | Yes | No | Yes | 2 | Infectious meningoencephalitis |

| CET 459 | Kogia breviceps | Yes | M | Adult | No | No | 3 | Trauma, bycatch? | |

| CET 460 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Calve | No | No | No | 4 | Trauma |

| CET 462 | Stenella frontalis | No | F | Calve | No | No | Yes | 5 | Not determined |

| CET 463 | Physeter macrocephalus | Yes | F | Neonate | Yes | No | No | 1 | Parental segregation |

| CET 464 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | Yes | M | Juvenile | No | No | No | 4 | Enterotoxaemia septicemia |

| CET 469 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Adult | ? | No | No | 3 | Parasitoses, senile disease |

| CET 471 | Ziphius cavirostris | Yes | F | Calve | ? | No | No | 2 | Chronic renal failure |

| CET 472 | Grampus griseus | Yes | F | Subadult | No | No | No | 2 | Trauma |

| CET 473 | Steno bredanensis | No | F | Juvenile | Yes | No | No | 2 | Septicemia |

| CET 474 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Adult | No | No | Yes | 2 | Septicemia |

| CET 476 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Calve | No | No | No | 2 | Chronic renal failure |

| CET 482 | Delphinus delphis | No | F | Adult | No | No | Yes | 3 | Bacterial bronchopneumonia |

| CET 483 | Grampus griseus | Yes | M | Adult | Yes | No | No | 2 | Venous gas embolism |

| CET 487 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Juvenile | No | No | No | 5 | Not determined |

| CET 504 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | Yes | M | Adult | No | No | No | 4 | Meningitis, septicemia |

| CET 505 | Tursiops truncatus | No | M | Juvenile | No | No | No | 5 | Not determined |

| CET 506 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Neonate | No | No | Yes | 4 | Not determined |

| CET 509 | Tursiops truncatus | No | M | Subadult | No | No | No | 4 | Not determined |

| CET 510 | Mesoplodon europaeus | Yes | M | Adult | ? | No | No | 3 | Trauma, possible viral disease |

| CET 512 | Globicephala macrorhynchus | Yes | M | Adult | No | No | No | 3 | Septicemia |

| CET 515 | Stenella frontalis | No | M | Adult | No | No | Yes | 2 | Toxoplasmosis |

| CET 517 | Delphinus delphis | No | M | Adult | No | No | No | 2 | Chronic renal failure |

| CET 520 | Physeter macrocephalus | Yes | F | Calve | No | No | No | 4 | Trauma |

| CET 521 | Delphinus delphis | No | ND | Juvenile | No | No | Yes | 5 | Not determined |

| CET 522 | Stenella frontalis | No | M | Adult | No | No | Yes | 3 | Toxoplasmosis |

| CET 523 | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | No | M | Calve | No | No | No | 2 | Parental segregation |

| CET 526 | Tursiops truncatus | No | F | Adult | ? | No | No | 2 | Septicemia |

| CET 527 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Adult | Yes | No | Yes | 3 | Parasitoses Bacterial infection |

| CET 530 | Stenella frontalis | No | F | Adult | ? | No | No | 2 | Trauma toxoplasmosis |

| CET 531 | Stenella frontalis | No | M | Juvenile | ? | No | No | 2 | Septicemia |

| CET 533 | Grampus griseus | Yes | M | Adult | No | No | No | 4 | Not determined, Parasitoses |

| CET 534 | Grampus griseus | Yes | M | Subadult | Yes | No | No | 1 | Viral disease, bacterial/mycotic infection |

| CET 537 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | F | Adult | No | No | No | 2 | Septicemia |

| CET 542 | Kogia sima | Yes | ND | Adult | No | No | No | 4 | Septicemia |

| CET 543 | Tursiops truncatus | No | M | Adult | No | No | No | 5 | Senile disease, parasitoses |

| CET 544 | Physeter macrocephalus | Yes | M | Juvenile | No | No | No | 5 | Trauma, ship collision |

| CET 546 | Stenella coeruleoalba | No | M | Adult | Yes | No | No | 3 | Trauma, stranding stress syndrome |

| CET 547 | Mesoplodon europaeus | Yes | M | Adult | ? | No | No | 4 | Not determined |

| CET 548 | Stenella frontalis | No | M | Calve | No | No | No | 2 | Viral disease |

| CET 549 | Grampus griseus | Yes | F | Adult | No | No | No | 2 | Venous gas embolism |

| CET 552 | Balaenoptera borealis | No | M | Juvenile | No | No | No | 5 | Pending |

| I134/07 | Otaria byronia | No | M | Adult | No | No | No | 3 | Not determined |

| I185/09 | Mesoplodon bidens | Yes | F | Adult | No | Yes | No | 5 | Pending |

| I344/07 | Otaria byronia | No | M | Juvenile | No | No | No | 2 | Iatrogenic pneumomediastinum |

| I298/09 | Physeter macrocephalus | Yes | M | Juvenile | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | Not determined |

| I299/09 | Physeter macrocephalus | Yes | M | Juvenile | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | Not determined |

| I300/09 | Physeter macrocephalus | Yes | M | Juvenile | Yes | Yes | No | 2 | Not determined |

? Indicates those animals that have been found dead, without signs of active stranding, but where passive stranding can not be either confirmed since they were found already dead.

Methods

At necropsy, putrefaction of the animal was evaluated using a morphological decomposition code from one to five according to Kuiken and García-Hartmann (1991) where one is the animal alive (becomes code 2 at death), code 2 is when the animal is extremely fresh (no bloating), code 3 is moderate decomposition (bloating, skin peeling but organs still intact), code 4 is advanced decomposition (major bloating, organs beyond recognition), and finally code 5 when no organs are present. Dissection, gas sampling and analysis were performed following procedures described by Bernaldo de Quirós et al. (2011). A total of 429 samples were recovered and analyzed from the studied animals, 208 (48%) of which belong to deep diving animals.

Samples containing blood were considered contaminated, since putrefaction gases from the blood will alter original gas sample composition. When no gas compound had a chromatographic signal higher than the detection limit, the sample was considered empty. In addition, if only one compound was present in slightly higher quantities than the established detection limit, the sample was considered small and not representative of its original composition. Finally samples with an atmospheric-air-like composition (around 79% nitrogen and 21% oxygen) were considered as “atmospheric-air polluted.” Thus, samples with blood, empty, or identified as small or atmospheric-air polluted were not included in the results. These samples represented 28% of the total. Most of them were emptied intestines or blood contaminated samples from the heart when only the vacutainer was applied. This problem was prevented later in the study by using an aspirometer (Bernaldo de Quirós et al., 2011).

The amount of gas present in veins and tissues was evaluated retrospectively using pictures and data in the necropsy reports. Gas amount was semi-quantified by giving a score to different vascular locations as well as to the presence of subcapsular gas (emphysema), defined as macroscopically visible gas found beneath the capsule of body organs (e.g., kidneys). Vascular locations studied for gas scoring were subcutaneous, mesenteric, and coronary veins as well as the lumbo-caudal venous plexus. We used the following score for these locations: grade 0 is no bubbles, grade I represented few bubbles and grade II represented abundant presence of bubbles. Prevalence of subcapsular gas, was evaluated with a similar grading system: grade 0 is no subcapsular gas, grade I represented the presence of subcapsular gas in one or two organs, and grade II represented wide distribution through the body organs. The summation of gas score (0–II) in the different vascular locations and tissues (subcapsular gas; n = 5), gave the total gas score for each animal that ranged from 0 to 10. However, because gas score was done retrospectively, some information was missing on occasion. Those cases on which only one localization could not be scored were marked with an asterisk (*), indicating that the total gas score might be up to two units higher according to the established gas score (e.g., 8*). If information from more than one localization was missing, the total gas score was not reported as it would not be a realistic estimate. Finally, there were some animals with advanced putrefaction where the veins could not be clearly distinguished from the rest of the tissues. Gas score was not undertaken in these cases.

The proportion of observations were analyzed for non-random associations between two categorical variables with the Fisher exact test. Hypothesis testing was considered significant when the corresponding P-value was less than 0.05. All data were analyzed using Sigma Stat software, version 3.5.

Results

Prevalence of bubbles

Intravascular bubbles were found in 51 out of 88 animals (58%). They were absent in 33 out of 88 (37%) and the observation was not correctly undertaken in 4 out of 88 animals (5%). Bubbles were statistically (P = 0.006) more frequently present in deep divers (76%) compared to non-deep divers (52%). Subcapsular emphysema (mostly peri-renal) was found in 57 out of 88 animals (65%). It was found in 66% of the non-deep diving animals and in 71% of the deep divers. This difference was statistically non-significant (P = 0.474).

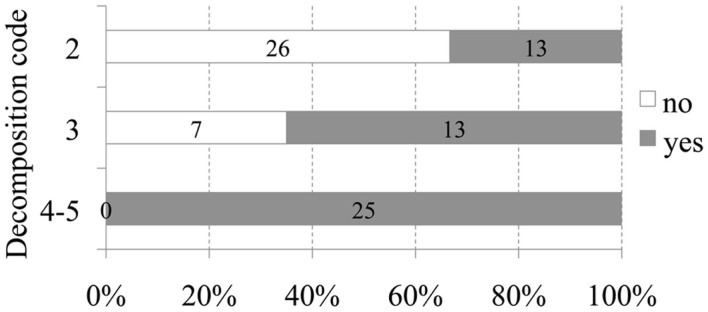

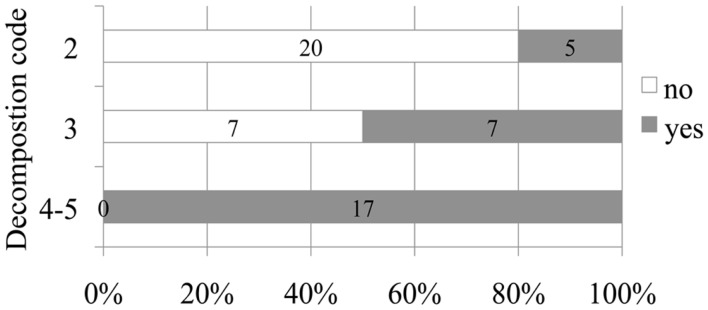

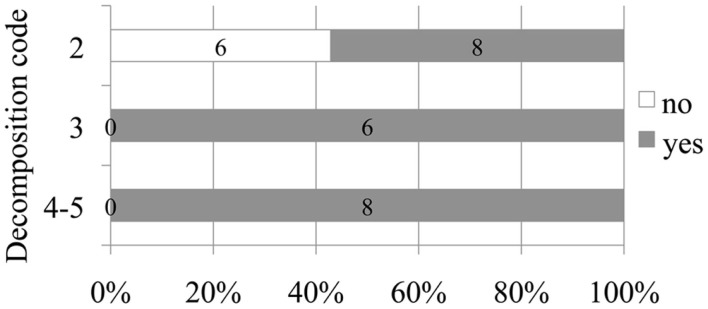

A positive relationship between decomposition code and presence of intravascular bubbles and/or subcapsular emphysema was found (Figure 1). Intravascular bubbles were present in all the studied animals with decomposition code 4 or higher. However, intravascular bubbles had a higher prevalence (P = 0.006) in deep divers compared to non-deep divers regardless of decomposition code (Figures 2 and 3); they were present in 57% of the fresh (decomposition code 2) deep diving animals compared to 20% of non-deep divers (P = 0.001), and in 100% of deep diving animals with decomposition code 3 compared to 50% of non-deep divers within the same decomposition code (P = 0.019). In addition, subcapsular emphysema was found in 64% of the deep divers vs. 44% with decomposition code 2, and in 66% of the deep divers vs. 61% of the non-deep divers with decomposition code 3, although these differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.204 and P = 0.648 respectively).

Figure 1.

Number and relative percentage of animals with intravascular bubbles (in dark gray) compared to those without bubbles (in white) regarding to decomposition code.

Figure 2.

Number and relative percentage of non-deep diving animals in which bubbles were observed (in dark gray) compare to those in which bubbles were absent (in white) attending to decomposition code.

Figure 3.

Number and relative percentage of deep diving animals in which bubbles were observed (in dark gray) compare to those in which bubbles were absent (in white) attending to decomposition code.

In 40% of the fresh animals with subcapsular emphysema, intravascular bubbles were additionally present, while 61% of the fresh animals with intravascular bubbles also had subcapsular emphysema.

In freshly dead animals, intravascular bubbles were seen in 7 out of 14 of the cetaceans that were known to strand actively (by swimming ashore) but only in 3 out of 15 that were found floating ashore dead or dead in the beach with no signs of active stranding. Animals found dead but suspected to have stranded alive were not included in the study. Differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.128).

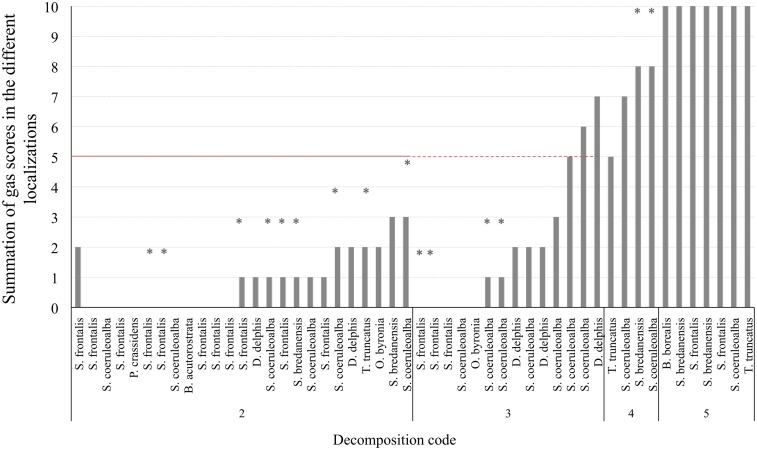

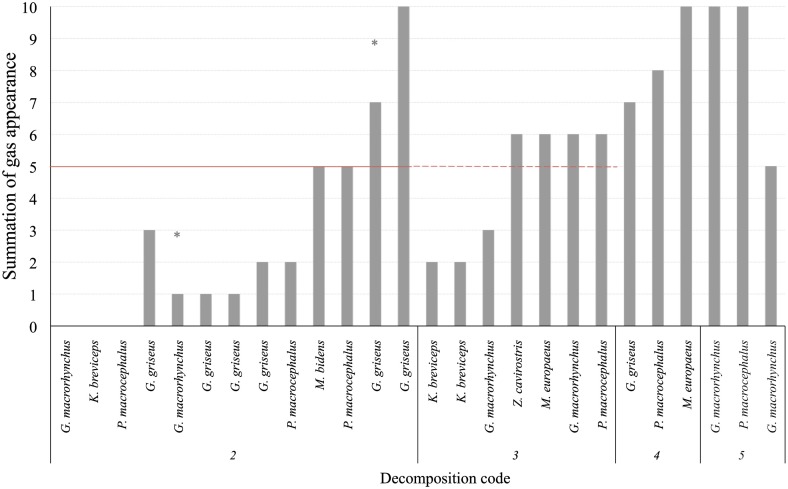

Amount of bubbles (gas score)

Non-deep divers

Gas score from fresh non-deep diving animals was always lower than half of the scale (5 on a scale of 10). Forty-four percent of them (11 out of 25) did not present either intravascular bubbles or subcapsular emphysema (gas score 0). Gas score of dolphins with incipient autolysis (decomposition code 3) varied greatly (from 0 to 7). Dolphins with advanced autolysis (decomposition code 4) had gas score ranging from 5 to 8 and potentially 10, while all animals in a very advanced state of autolysis (decomposition code 5) had the maximum gas score until an advanced state of decay was reached and integrity of the tissues was lost (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Total gas score (summation of gas scores in the different localizations) for each animal (non-deep divers). Asterisks represent the maximum potential summation gas score for a given animal, on which one localization was not adequately observed for bubbles. The red line is presented at half of the total gas score (5 of 10) in order to better illustrate the total gas scores of animals that fall above and bellow the medium.

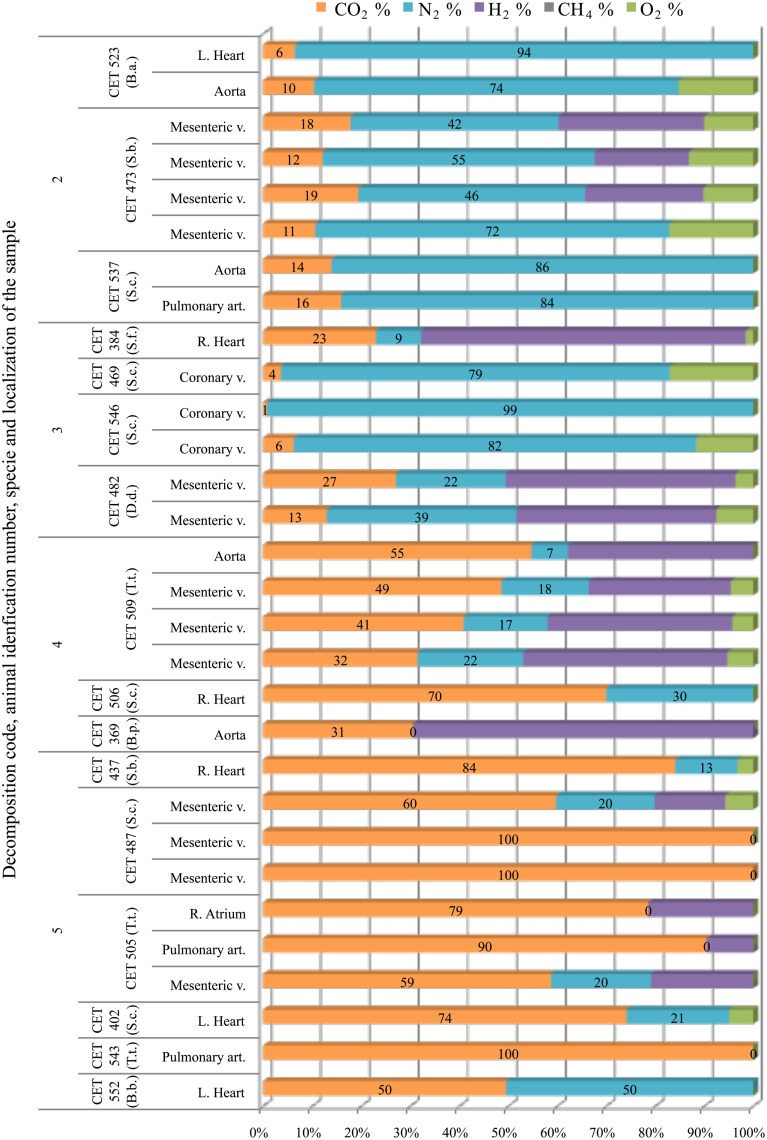

Deep divers

Gas score from fresh deep divers was higher compared to non-deep divers. Thirty-five percent of the animals (5 out of 14) presented gas score 5 or higher. Indeed, two of these animals presented the highest gas score of all studied animals with decomposition code 2. They presented high (7*) and very high (9) gas score. All deep divers with decomposition code 3 presented bubbles, most of them with values around or slightly higher than gas score 5. Deep divers with decomposition code 4 had a gas score ranging from 7 to 10, while those with decomposition code 5 had a gas score of 9 or 10 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Total gas score (summation of gas scores in the different localizations) for each animal (deep divers). Asterisks represent the maximum potential summation gas score for a given animal, on which one localization was not adequately observed for bubbles. The red line is presented at half of the total gas score (5 of 10) in order to better illustrate the total gas scores of animals that fall above and bellow the medium.

Gas composition

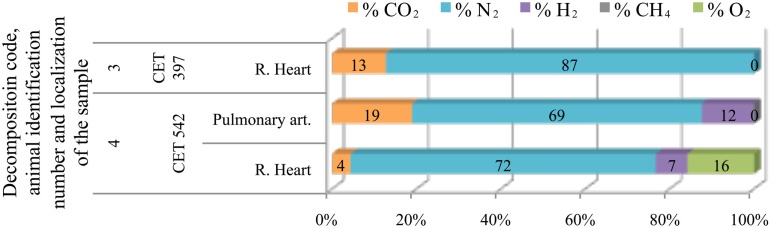

Intravascular bubbles of non-deep divers

The main gas compound in intravascular bubbles recovered from non-deep divers in a fresh status or with incipient autolysis (codes 2 and 3) was nitrogen. Hydrogen was found in some samples of these animals (in one animal with decomposition code 2 and in two animals with decomposition code 3), especially in the mesenteric veins. When hydrogen was not present, nitrogen concentrations were between 70 and 90%. On the other hand, samples from more decomposed animals (codes 4 and 5) consisted of high levels of CO2 (>30%) together with some hydrogen and/or nitrogen (Figure 6). In some cases, the sample was 100% CO2.

Figure 6.

Intravascular bubble’s gas composition sampled form different non-deep diving species (B.a., Balaenoptera acutorostrata; S.b., Steno bredanensis; S.c., Stenella coeruleoalba; S.f., Stenella frontalis; D.d., Delphinus delphis; T.t., Tursiops truncatus; B.p., Balaenoptera physalus; B.b., Balaenoptera borealis), in different tissues and decomposition codes, illustrating the contribution of each gas to the total amount in percentage μmol.

Intravascular bubbles of deep divers

Kogiidae

Only four Kogia sp. individuals were studied. In addition they presented low gas scores, therefore few gas samples could be obtained. Gas samples were mainly composed of nitrogen (70–90%) although hydrogen appeared with decomposition code 4 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Intravascular bubble’s gas composition of deep diving animals belonging to Kogiidae family in different tissues and decomposition codes, illustrating the contribution of each gas to the total amount in percentage μmol.

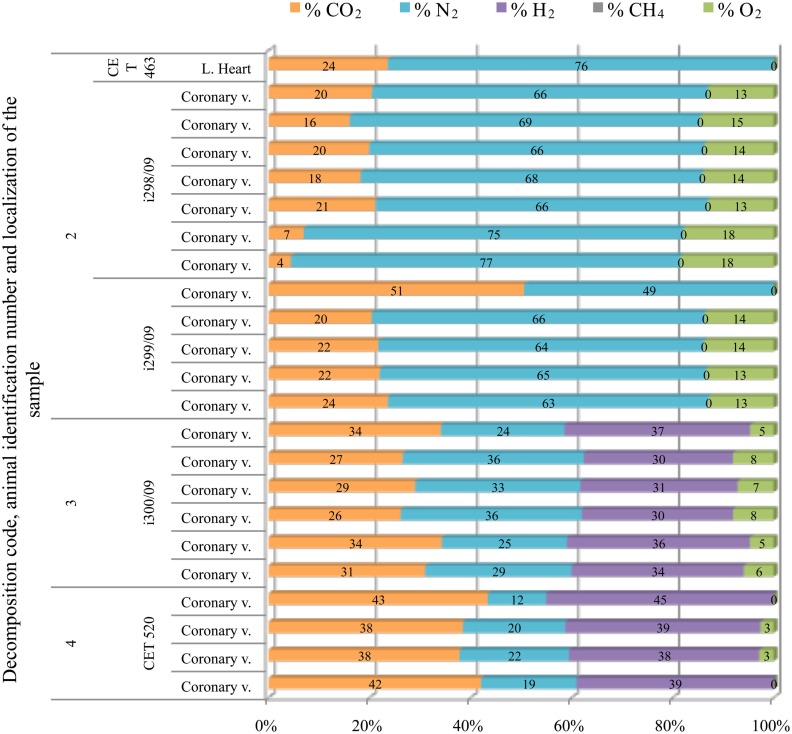

Physeteridae

In sperm whales, gas composition from fresh animals had consistently high nitrogen content (around 70%). This gas composition changed dramatically with incipient autolysis. Gas composition from more decomposed animals consisted of a mixture of hydrogen, CO2, and nitrogen. Oxygen was only present in the three animals that stranded alive in the coast of Italy (Bernaldo de Quirós et al., 2011; Mazzariol et al., 2011; Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Intravascular bubble’s gas composition of deep diving animals belonging to Physeteridae family in different tissues and decomposition codes, illustrating the contribution of each gas to the total amount in percentage μmol.

Globicephala

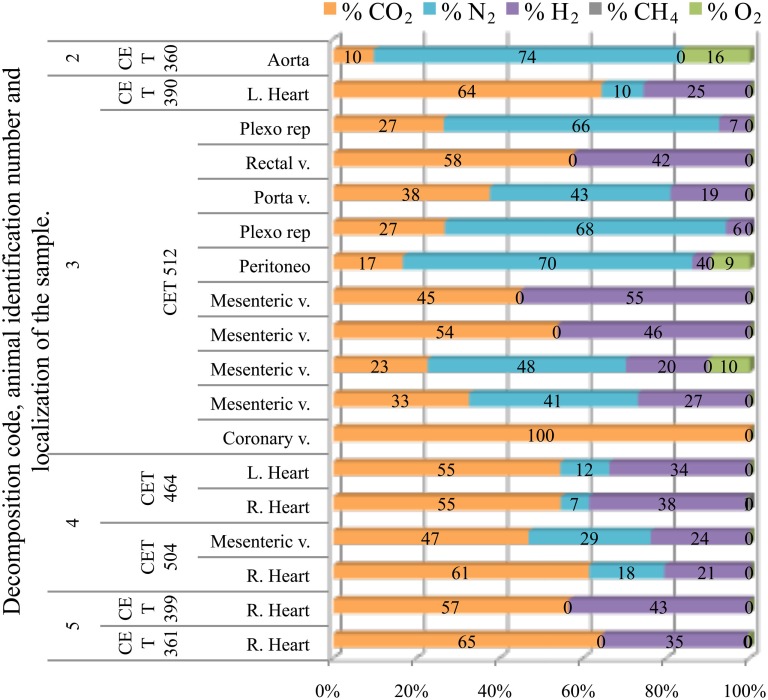

Fresh pilot whales presented none or few bubbles; therefore only one sample from a fresh animal could be obtained. This sample was composed of a high concentration of nitrogen (74%) together with oxygen and CO2. Samples from animals with incipient autolysis varied in composition. There were some intravascular bubbles with high nitrogen content although hydrogen was already present. The rest of the bubbles were composed of a mixture of CO2, hydrogen, and nitrogen in similar concentrations. In more decomposed animals, nitrogen levels decreased further, and the gas was composed of a mixture of CO2 and hydrogen; CO2 having the highest concentration with nitrogen having concentrations lower than 30%. In the samples from the most decomposed animals, nitrogen was no longer present. Intravascular bubbles were composed of a mixture of CO2 and hydrogen with similar concentrations, although CO2 content was always slightly higher than hydrogen. In summary, a clear difference was found in gas composition of bubbles in animals with different decomposition codes (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Intravascular bubble’s gas composition of deep diving animals belonging to Globicephala macrorhynchus specie in different tissues and decomposition codes, illustrating the contribution of each gas to the total amount in percentage μmol.

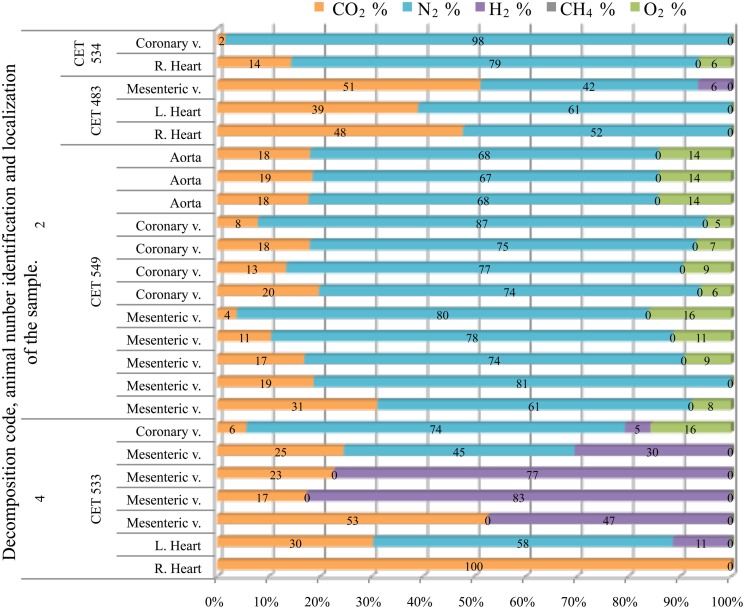

Grampus

Samples from fresh animals were composed of nitrogen, CO2, and in most cases some oxygen. They were composed of 76 ± 7% of nitrogen and 15 ± 9% of CO2, with the exception of “CET 483” where higher CO2 concentrations were found (40–60%). All these samples were clearly different from samples obtained from a more decomposed animal (with decomposition code 4) whose samples were mainly composed of CO2 and hydrogen (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Intravascular bubble’s gas composition of deep diving animals belonging to Grampus griseus specie in different tissues and decomposition codes, illustrating the contribution of each gas to the total amount in percentage μmol.

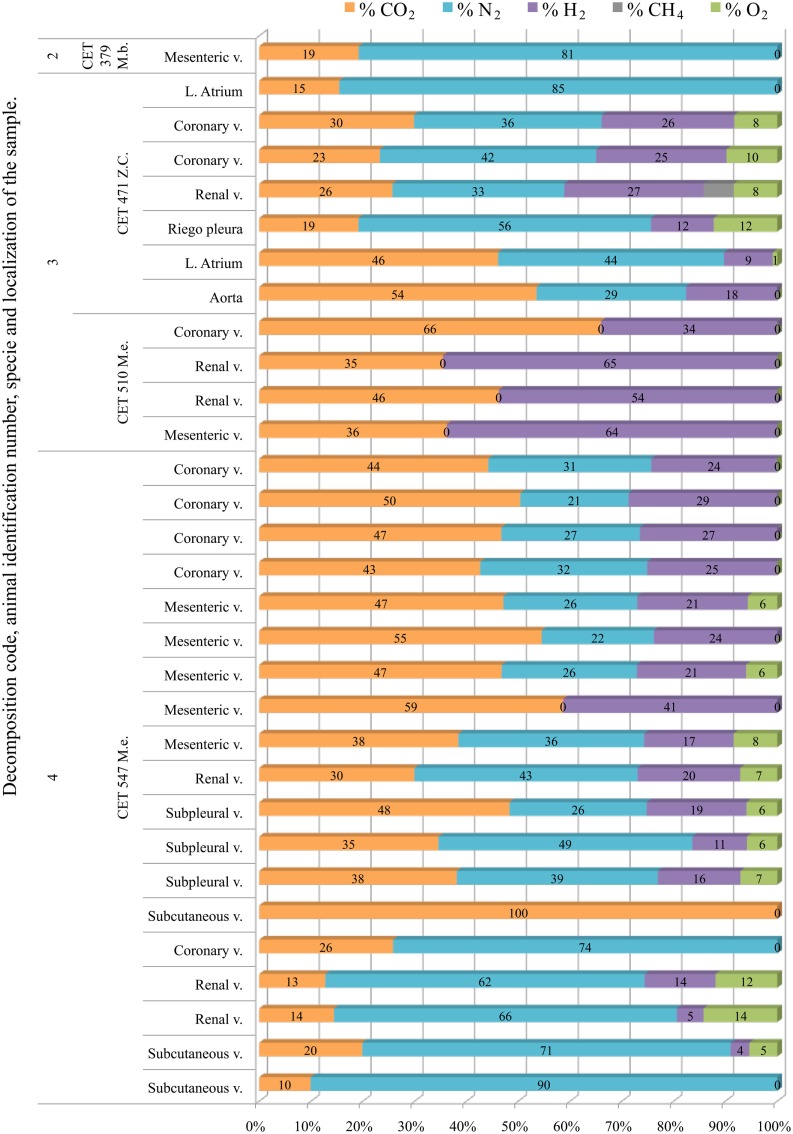

Ziphiidae

Only one sample was successfully analyzed from a fresh animal. It was composed of high nitrogen content (81%) and CO2. Gas composition from more decomposed animals was highly variable, with no clear trend along decomposition codes. Hydrogen was always present except for two samples from “CET 547” with decomposition code 4. In this same animal there were three more samples with low hydrogen concentration (below 15%). With the exception of these samples, nitrogen was always lower than 60% in the more decomposed animals. Samples were a mixture of CO2, nitrogen, and hydrogen. In some samples nitrogen was absent and bubbles were composed of CO2 and hydrogen exclusively (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Intravascular bubble’s gas composition of deep diving animals belonging to Ziphiidae (M.b., Mesoplodon bidens; Z.c., Ziphius cavirostris; M.e., Mesoplodon europaeus) family in different tissues and decomposition codes, illustrating the contribution of each gas to the total amount in percentage μmol.

Intestinal gas

Gas composition from the intestines was highly variable with no trend with PM time. Nitrogen was found in high concentrations (higher than 60%) in 21% of the samples. However, nitrogen was found in very low concentrations in the rest of the samples. In 40% of the samples, nitrogen was not present. In most of the samples (67%), CO2 was the major compound reaching values as high as 100%. Hydrogen was very frequently found in the intestine (in 64% of the samples). Therefore most of the samples were a mixture of high CO2 levels with hydrogen and some, if any, nitrogen. Methane was only detected in Kogiidae and Physeteridae.

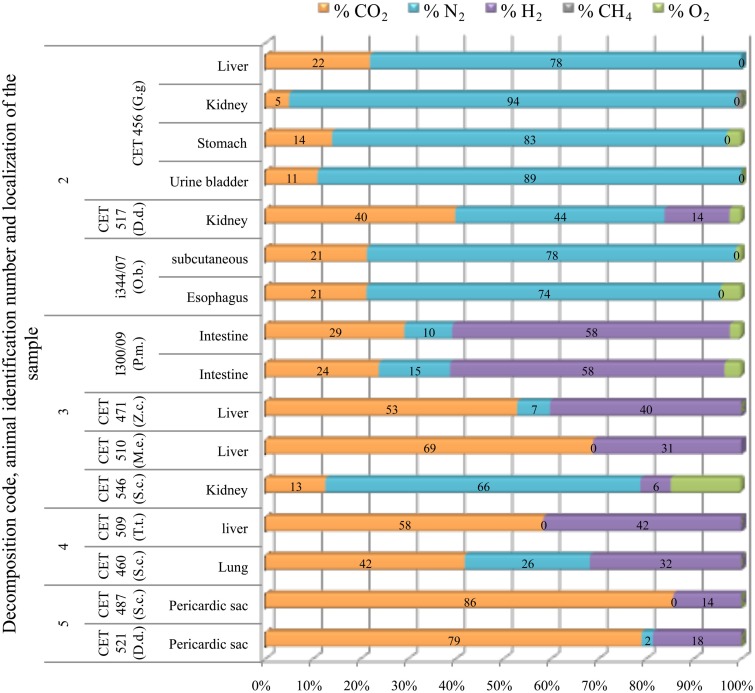

Subcapsular emphysema

Subcapsular gas was composed of around 80% of nitrogen and 20% of CO2 in the fresh animals studied (a Risso’s dolphin and a sea lion), except from one sample recovered from the peri-renal area of a common dolphin (CET 517). Gas composition of subcapsular samples from the fresh animals was clearly different from those of more decomposed animals, which mainly consist on CO2 and hydrogen. Nitrogen was lower than 30% when present. Nitrogen was found in high concentrations in only one sample from the most decomposed animals. This sample also presented the highest concentration of oxygen (15% compared to a maximum of 4% in the rest of the samples; Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Subcapsular gas (emphysema) composition found in different tissues from deep diving (G.g., Grampus griseus; D.d., P.m., Physeter macrocephalus; Z.c., Ziphius cavirostris; M.e., Mesoplodon europaeus) and shallow diving animals (D.d., Delphinus delphis; O.b., Otaria byronia; S.c., Stenella coeruleoalba; T.t., Tursiops truncatus) with different decomposition codes, illustrating the contribution of each gas to the total amount in percentage μmol.

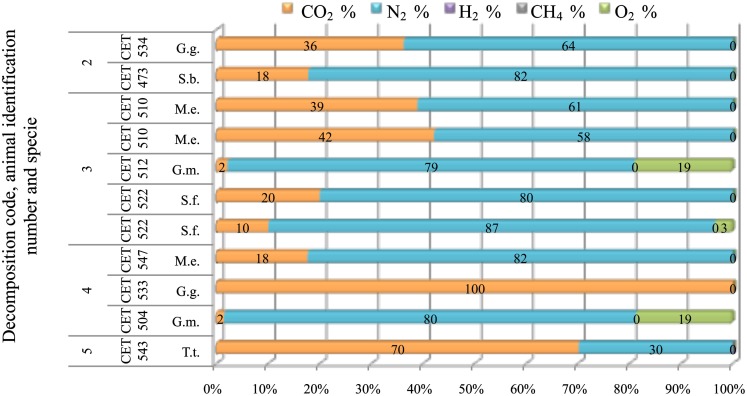

Gas from the pterygoidal sinuses

Gas composition from the sinuses remained constant for longer PM time compared to gas recovered from other tissues. Nitrogen was always the major compound (58–87%) until decomposition code 4 was reached. Within these decomposition codes, CO2 was present in concentrations ranging from 10 to 36%. After decomposition code 4, CO2 increased devaluating nitrogen presence. There were two samples with atmospheric-air like composition (CET 512 and CET 504) (Figure 13)

Figure 13.

Gas composition of pterygoid air sacs from animals (G.g., Grampus griseus; S.b., Steno bredanensis; M.e., Mesoplodon europaeus; S.f., Stenella frontalis; G.m., Globicephala macrorhynchus; T.t., Tursiops truncatus) with different decomposition codes, illustrating the contribution of each gas to the total amount in percentage μmol.

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive study of prevalence, amount (gas score), distribution, and composition of bubbles found in stranded cetaceans. The animals included in the study presented different decomposition codes allowing us to study putrefaction gases that may mask a decompression-induced gas phase. In addition, the high number of animals (83) and species included in the study (18) enabled us to relate the results with the diving behavior of the animals. This study demonstrates the utility of scoring and analyzing the gas in stranded marine mammals, especially in fresh animals, encouraging the performance of the necropsy as soon after death as possible.

Bubble prevalence and abundance

Fifty-one out of 88 stranded animals presented macroscopic bubbles during the necropsy. This represents 58% of the animals that were studied indicating that the presence of gas bubbles within the cardiovascular system in stranded cetaceans is a common gross finding during necropsy.

In forensic human pathology the presence of intravascular gas in carcasses decomposing under different environmental conditions is well known and widely reported (Knight, 1996). Indeed, bubbles were found in all the studied animals with decomposition code 4 and 5. Putrefaction is a continual process of gradual decay and disorganization of organic tissues and structures after death that results in the production of liquids, simple molecules, and gases (intravascular gas and/or putrefactive emphysema; Vass et al., 2002; Lerner and Lerner, 2006). However, it is very unusual to find gas bubbles within the cardiovascular system in fresh necropsied domestic animals or humans (King et al., 1989; Knight, 1996). Therefore, the most interesting data are those recorded from fresh animals. Our results demonstrated that it is not uncommon to find intravascular bubbles in fresh cetaceans. Thirty-three percent of our fresh animals presented intravascular bubbles to some extent, but only two animals presented high gas score. Recent studies have demonstrated that large amounts of intravascular bubbles found within a few hours PM are not due to putrefaction processes (Bernaldo de Quirós, 2011). Indeed, these animals were the only ones diagnosed with gas embolism according to the pathological studies carried out by the ULPGC. Therefore amount of intravascular bubbles is more important than the mere presence of bubbles from a pathological point of view in stranded cetaceans, and the gas score is also an efficient tool to distinguish between gas embolism and putrefaction gases in stranded cetaceans. Although we used a simple gas scoring technique with a scale from 0 to 10 because the study was done retrospectively, we encourage using a larger gas score scale (0–27) described by Bernaldo de Quirós (2011). This gas score has a grading scoring of 0–6 for the different vascular localizations (n = 4) and a 0–3 grading scoring for subcapsular gas (0–3). Therefore, total gas score in each animal ranged from 0 to 27. A larger scale highlights better the possible differences in gas score along decomposition codes.

Subcapsular emphysema in the peri-renal area has been described in 22 of 22 alive stranded animals using B-mode ultrasound (Dennison et al., 2012). In our study, we found it in 20 out of 39 fresh animals. Although the prevalence is smaller in our study, it still suggests that subcapsular emphysema is a common finding in dead stranded cetaceans. However, we could not find a clear relationship between subcapsular emphysema and intravascular bubbles. There is a 60% chance that a fresh animal with intravascular bubbles presents subcapsular emphysema, but 60% of the fresh animals with subcapsular emphysema showed no intravascular bubbles. Therefore, intravascular bubbles can occur without simultaneous subcapsular emphysema and vice versa.

An interesting result from our data was that intravascular bubbles were more frequently found (P = 0.006) and in higher quantities in deep divers than in non-deep divers regardless of decomposition code. The higher prevalence of intravascular bubbles related to the diving behavior of the species, together with the fact that finding bubbles in necropsied domestic animals or humans is very unusual and mostly linked to iatrogenic air embolism or diving fatalities (Knight, 1996; Muth and Shank, 2000), suggest that the most parsimonious explanation for the presence of small quantities of intravascular bubbles in fresh stranded cetaceans would be diving physiology related (Tikuisis and Gerth, 2003). Thus our results further suggest that deep divers might be at a higher risk from decompression.

Gas composition

Intravascular bubbles and subcapsular emphysema of fresh marine mammals (decomposition code 2) showed high concentrations of nitrogen (>70%) and values of CO2 around 20%. Similar results were obtained in animal models exposed to air embolism or compression and decompression using the same methodology (Bernaldo de Quirós, 2011). Furthermore, these values are in accordance to what has been reported in cases of air embolism and/or DCS in humans and laboratory animals (Bert, 1878; Armstrong, 1939; Pierucci and Gherson, 1968; Smith-Sivertsen, 1976; Ishiyama, 1983; Bajanowski et al., 1998; Bernaldo de Quirós, 2011). In addition, gas from pterygoideal sinuses showed high concentrations of nitrogen in animals with decomposition codes 2 and 3. This was an additional finding that needs further investigation (Figure 13).

Hydrogen, which is a putrefaction indicator (Pierucci and Gherson, 1969), was mostly found after decomposition code 3 in gas collected from the different localizations (intravascularly, subcapsularly, or in the pterygoideal sinuses). Animals with incipient autolysis (decomposition code 3), had gas samples that varied from typical gas embolism composition to putrefaction gases (Pierucci and Gherson, 1968, 1969). Samples from animals with decomposition code 4 and 5 always presented high CO2 concentrations together with hydrogen in most of the cases and low concentration of nitrogen (mostly lower than 40%) if present. In a few decomposed samples, small quantities of oxygen were also detected. This gas composition was very similar to the gas composition of the subcapsular emphysema found in very decomposed animals and completely different from gas composition of intravascular bubbles and subcapsular emphysema in fresh animals.

These data show that detection of hydrogen and/or very high levels of CO2 are “signal” gases indicative of putrefaction, while nitrogen decreases progressively until disappearing (not detected chromatographically) in carcasses with the highest decomposition code (code 5). Similar results have been described in humans and laboratory animals (Pierucci and Gherson, 1968, 1969; Keil et al., 1980; Bajanowski et al., 1998). In this sense, we can state that hydrogen in stranded cetaceans is also a key putrefaction marker with one exception that will be discussed later. In some cases, we have found one sample’s composition to be clearly different from the rest of the samples, presenting significantly higher nitrogen and oxygen content. Thus, we have considered as a first option, a likely contamination of atmospheric-air during sampling (see as an example the sample from CET 546 in Figure 12). The exception previously mentioned, was a Steno bredanensis (CET 473) with decomposition code 2 that presented hydrogen in the mesenteric veins. Here, it is important to remember that these are stranded animals, and in most of the cases sick animals. Therefore these gas results should be considered together with the individual diagnostic analysis (including pathology, microbiology, toxicology, etc.). Speculatively, we have considered acute gastrointestinal disease as a primary source of hydrogen or due to overlapping with other pathogenic processes, although further research is needed in order to confirm this hypothesis.

One of the most interesting and unexpected results was CO2 concentrations of around 40–50% in the animal with the second highest gas score for fresh animals and diagnosed with gas embolism by the ULPGC (CET 483). This gas composition is not in accordance with traditional DCS theories or some of the empirical values reported for DCS (Bert, 1878; Smith-Sivertsen, 1976; Ishiyama, 1983; Tikuisis and Gerth, 2003). However Armstrong (1939) reported values of 30% of CO2 in decompressed goats, and Bernaldo de Quirós (2011) has recently reported very similar CO2 concentrations to our results in rabbits.

In addition there are several empirical and physical models suggesting an important role of CO2 in bubble formation: (i) there is a higher prevalence of elevated CO2 in bends following dives using compressed air (Behnke, 1951), (ii) a statistically significant increase in DCS risk in rats breathing elevated levels of CO2 in either He-O2, or N2-O2 mixtures during the hyperbaric exposure has been reported (Berghage et al., 1978), (iii) bubbles moving vertically through different water layers alternately saturated with air or CO2, increase in size in the CO2 saturated water and decreasing in the air-saturated layer (Harvey, 1945), (iv) bubbles formed with less mechanical agitation and grew at a faster rate in decompressed tubes filled with water saturated of CO2 rather than nitrogen (Harris et al., 1945). All these findings, suggest that CO2 might play an important role in bubble formation due to the high diffusivity of this gas. If this is the case, prolonged dives where CO2 will build up might pose an additional risk to animals with nitrogen saturation.

Theoretical studies have predicted BWs end-dive nitrogen levels that would cause a significant proportion of DCS cases in land mammals (Houser et al., 2001; Zimmer and Tyack, 2007; Hooker et al., 2009). In addition BWs have both the deepest (3120 m) and longest (137 min) dives ever recorded from an air-breathing mammal (Schorr et al., 2011). Furthermore, BWs exposed to mid-frequency sonar playback have reacted with unusual longer and slower ascent dives (Tyack et al., 2011). All BWs included in our study presented a minimum gas score of 5, this was not found in the other studied sub groups. Although more fresh animals should be studied in order to make conclusions, our results suggest that BWs might be the most sensitive species to bubble formation. Future theoretical studies should consider CO2 accumulation in addition to nitrogen saturation, and its possible role in bubble formation.

We have shown that gas analysis may be a valid a technique to differentiate between gas embolism and putrefaction gases in stranded cetaceans. Therefore we encourage gas analysis. To try to avoid putrefaction-masking gases, necropsy, and gas sampling must be performed as soon as possible, before 24 h PM is recommended but preferably within 12 h PM. However, if gas analyses are not possible due to logistics, we strongly recommend doing the gas scoring, which is of no additional cost.

Source of bubbles

In summary, intravascular bubbles and subcapsular emphysema are a common finding during necropsies of stranded marine mammals, although they are present in low quantities (low gas score) and with a gas composition of around 70–80% of nitrogen and 20–30% of CO2. They are more frequently found (P = 0.006) and in higher quantities in deep divers vs. non-deep divers. They have higher prevalence in active stranded animals, although they are also present in passive stranded animals. Based on gas composition and in the highest prevalence of bubbles in deep divers, the most likely source of these bubbles is decompression-related.

In air-breathing animals, nitrogen can build up in tissues and formed bubbles. Although they only have a finite amount of air in their lungs available for nitrogen diffusion, PN2 in the alveoli increases with compression of the thorax as the pressure increases. This results in a net exchange of nitrogen across the alveolar membrane and it is either taken up or removed by the blood and tissues depending on the partial pressure gradient. During ascent, nitrogen diffusion from tissues to blood and alveolus is slower, and if the surface interval is too short, not all of the nitrogen that has been taken up is removed. This may result in nitrogen build up in tissues during repeated dives (Ferrigno and Lundgren, 2003). When the sum of the dissolved gas tensions (oxygen, CO2, nitrogen, helium) and water vapor exceeds the local absolute pressure, a state known as supersaturation, bubbles may form due to gas phase separation (Hamilton and Thalmann, 2003; Vann et al., 2011). Bubbles can form without negatively impacting a diving animal, but bubbles can have mechanical, embolic, and biochemical manifestations ranging from trivial to fatal (Vann et al., 2011). They are generally considered a pivotal event in the occurrence of DCS (Francis and Simon, 2003).

Decompression bubble formation may still occur even after death if the animal dies at depth and is later depressurized, a phenomenon known as post mortem off gassing (Brown et al., 1978; Lawrence, 1997; Cole et al., 2006; Lawrence and Cooke, 2006; Wheen and Williams, 2009). Post mortem off gassing has been proposed for explaining the existence of bubbles in marine mammals trapped in fishing nets (Moore et al., 2009). These animals died at depth and were later hauled out. Our studied animals are stranded marine mammals, which presumably have not died at depth. Thus, post mortem off gassing is ruled out as a plausible mechanism. The stated absence of bubbles in stranded animals in the Moore et al. study probably reflects a relative, rather than absolute absence, with bubble quantity being far more obvious in the animals drowned at depth that off-gassed post mortem. These authors probably failed to record the low prevalence of bubbles commonly seen in stranded animals in the current study (Michael Moore, personal communication). It is interesting that the Moore et al. findings likely reflect a routine supersaturation state in foraging, diving marine mammals. Analysis of the gas bubble composition of drowned bycatch would test this hypothesis.

The most likely explanation for the observed gas composition in the freshly dead animals is that bubbles were in vivo or peri mortem formed from supersaturated tissues by physiological off gassing. Indeed, a recent study has shown that intravascular bubbles and peri-renal subcapsular emphysema occur in live marine mammals and without clinical consequences (Dennison et al., 2012). The stranding itself has been proposed as a causal mechanism for bubble formation in marine mammals (Houser et al., 2010; Dennison et al., 2012). According to this hypothesis, a fast stranding will result in the inability to recompress resulting in problematic supersaturation of the tissues. In addition, as a consequence of the stranding, there would be tissues of reduced perfusion and blood pooling that would continue to off-gas, but because the vascular flow to the lung is supposed to be compromised, nitrogen elimination would not be as effective and autochthonous bubble formation would increase (Houser et al., 2010).

Another plausible stranding mechanism related would be tribonucleation. Tribonucleation occurs when two surfaces in intimate contact but separated by a viscous liquid film are suddenly separated in an abrupt way. Then, the viscosity will avoid sudden filling and cavities, which will be filled by diffusing gases, can occur (Banks and Mill, 1953; Hayward, 1967; Campbell, 1968; Ikels, 1970; Blatteau et al., 2006). This phenomenon has been proposed to happen with movements, exercise (McDonough and Hemmingsen, 1984a,b, 1985a,b), within the joints (Fick, 1911), or in the heart valves (Hennessy, 1989). The agonal actions of the beached animals have been proposed to promote bubble formation (Houser et al., 2010).

We have found intravascular bubbles in 3 out of 15 of the animals that stranded passively, where reduced perfusion and tribonucleation are not expected. Regardless of the low number of passive strandings studied, our results support the idea that bubbles can occur independently to the stranding, as reported in three BWs (one fresh, one partially autolytic, and an autolytic animal) which were recovered floating in the atypical mass stranding event of the Canary Islands in 2002 (Fernandez et al., 2005). However, since we have found a higher prevalence of bubbles in actively stranded animals (although the difference was non-statistically significant), we suggest that stranding is not a necessary factor but a contributing factor in bubble formation.

More recently, Houser et al. (2010) and Dennison et al. (2012) hypothesized that the abnormal behavior of moribund cetaceans that might spend a period of time at sea with reduced depth and repetitiveness, may allow them to wash out nitrogen prior to stranding. Few (Dennison et al., 2012) or no (Houser et al., 2010) empirical data were presented to support this suggestion. Our study animals are mostly single stranded specimens, affected by different pathologies (Table 1). According to the mentioned hypothesis, it is presumed that our case studies have washed out their nitrogen prior to stranding. Our results do not support this hypothesis; intravascular bubbles were found in 57% of the fresh deep diving animals and in 20% of the non-deep diving animals, and they were mainly composed of nitrogen (70–80%). Dennison et al. (2012) further hypothesize that the prevalence of bubbles will be less in most single stranded than mass stranded animals, if they were diving less over an extended period. Since our study cases are mostly single stranded animals, we could not test this hypothesis. Further studies are needed to confirm whether mass stranded animals have higher prevalence of bubbles compared to single–stranded animals.

If bubbles are not a consequence of the stranding, and since no embolic related lesions were found in the pathological study, it is reasonable to consider as a hypothesis that this small amount of bubbles composed of nitrogen found in fresh stranded animals, were silent bubbles. The existence of potentially asymptomatically bubbles in marine mammals has been reported before (Dennison et al., 2012). However, we studied dead animals where symptoms could not be evaluated, therefore our results are indicative but not conclusive by itself of the existence of silent bubbles in marine mammals. A recent review of evidences for gas bubble incidence in marine mammals concluded that they may deal with bubbles on a more regular basis than previously thought (Hooker et al., 2012) and suggested that our view of marine mammal adaptations should therefore change from one of simply minimizing nitrogen loading to one of management of the nitrogen load. Our study further supports the hypothesis that decompression-induced bubbles are relatively common but that marine mammals have unknown adaptations allowing them to tolerate these under natural conditions. It is important to remember that our case studies have only few bubbles and died from numerous pathological reasons different from gas embolism. Only two animals, showing a lot of bubbles widely dispersed and with no other pathological signs, were diagnosed with massive gas embolism.

Further research is needed in order to clarify questions that remain unanswered from this study. The clinical impact of subcapsular emphysema remains unclear from this study since gas composition indicates a plausible physiological decompression-related off gassing origin, but no clear relationship with intravascular bubbles was found. More studies are needed in order to better understand the formation of this gas and the plausible impact that might have on the health status of the animals. Comparison between single-active, single-passive, mass stranded, and by caught animals, might contribute to a better understanding of the causative factor of intravascular bubble formation as well as nitrogen supersaturation levels on these animals, and different species sensibilities (like deep divers vs. non-deep divers). These will provide new data that should be considered in future diving physiology models and studies.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that bubbles are a common finding in stranded cetaceans. The amount and composition of these bubbles in fresh animals suggests that these bubbles have formed from nitrogen-supersaturated tissues, most likely formed in vivo. This study has also demonstrated that these bubbles were more frequently found in deep divers indicating a higher risk of decompression to these species. Further research is needed in order to determine if there are any species-specific sensibilities to bubble formation as preliminary results point out, as well as the implications that CO2 accumulation along a dive might have for these animals from a diving physiology perspective. Finally, monitoring live non-deep diving and deep diving animals with an ultrasound might help to confirm the hypothesis deduced from our results.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all colleagues from the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain) that contribute to this work and to the different stranding networks and governments: Canary Islands, United Kingdom, and Italy. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation with two research projects: (AGL 2005-07947) and (CGL 2009/12663), as well as the Government of Canary Islands (DG Medio Natural). The Spanish Ministry of Education contributed with personal financial support (the University Professor Formation fellowship). The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Marine Mammal Centre and Wick and Sloan Simmons provided funding for the latest stage of this work.

References

- Aguilar de Soto N. (2006). Acoustic and Diving Behaviour of the Short Finned Pilot Whale (Globicephala macrorhynchus) and Blainville’s Beaked Whale (Mesoplodon densirostris) in the Canary Islands. Implications of the Effects of Man-Made Noise and Boat Collisions. Doctoral thesis, La Laguna University, La Laguna [Google Scholar]

- Arbelo M. (2007). Patología y causas de la muerte de los cetáceos varados en las Islas Canarias (1999–2005). Ph.D. Doctoral thesis, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong H. G. (1939). Analysis of Gas Emboli. Engineering Section Memorandum Report EPX-17-54-653-8, Wright Field, OH. [Google Scholar]

- Astruc G., Beaubrun P. (2005). Do Mediterranean cetaceans diets overlap for the same resources? Eur. Res. Cet. 19, 81 [Google Scholar]

- Bajanowski T., Kohler H., Duchesne A., Koops E., Brinkmann B. (1998). Proof of air embolism after exhumation. Int. J. Legal Med. 112, 2–7 10.1007/s004140050189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks W. H., Mill C. C. (1953). Tacky adhesion - A preliminary study. J. Colloid Sci. 8, 137–147 10.1016/0095-8522(53)90014-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke A. R. (1951). “Decompression sickness following exposure to high pressures,” in Decompression Sickness, ed. Fulton J. F. (Phyladelphia: Saunders; ), 53–89 [Google Scholar]

- Belanger L. F. (1940). A study of the histological structure of the respiratory portion of the lungs of aquatic mammals. Am. J. Anat. 67, 437–469 10.1002/aja.1000670305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berghage T. E., Keating L. J., Wooley J. M. (1978). “Decompression sickness in rats and mice rapidly decompressed after breathing various concentrations of carbon dioxide,” in Proceedings of the Sixth Underwater Physiology Symposium, ed. Lambertsen C. J. (Bethesda: ), 485–496 [Google Scholar]

- Bernaldo de Quirós Y. (2011). Methodology and Analysis of Gas Embolism: Experimental Models and Stranded Cetaceans. Ph.D. Doctoral thesis, University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria [Google Scholar]

- Bernaldo de Quirós Y., González-Díaz Ó., Saavedra P., Arbelo M., Sierra E., Sacchini S., Jepson P. D., Mazzariol S., Di Guardo G., Fernández A. (2011). Methodology for in situ gas sampling, transport and laboratory analysis of gases from stranded cetaceans. Sci. Rep. 1, 193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert P. (1878). La Pression Barometrique: Recherches de Physiologie Expérimentale. Paris: Masson [Google Scholar]

- Blatteau J. E., Souraud J. B., Gempp E., Boussuges A. (2006). Gas nuclei, their origin, and their role in bubble formation. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 77, 1068–1076 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom B. L., Fahlman A., Jones D. R. (2008). Tracheal compression delays alveolar collapse during deep diving in marine mammals. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 161, 298–305 10.1016/j.resp.2008.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. D., Kime W., Sherrer E. L. (1978). Postmortem intra-vascular bubbling – decompression artifact. J. Forensic Sci. 23, 511–518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler P. J., Jones D. R. (1997). Physiology of diving of birds and mammals. Physiol. Rev. 77, 837–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. (1968). The tribonucleation of bubbles. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 1, 1085–1088 10.1088/0022-3727/1/8/421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A. J., Griffiths D., Lavender S., Summers P., Rich K. (2006). Relevance of postmortem radiology to the diagnosis of fatal cerebral gas embolism from compressed air diving. J. Clin. Pathol. 59, 489–491 10.1136/jcp.2005.031708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox T. M., Ragen T. J., Read A. J., Vos E., Baird R. W., Balcomb K., Barlow J., Caldwell J. M., Cranford T., Crum L. A., D’Amico A., D’Spain G., Fernandez A., Finneran J. J., Gentry R., Gerth W. A., Gulland F. M. D., Hildebrand J., Houser D., Hullar T., Jepson P. D., Ketten D., Macleod C. D., Miller P., Moore S., Mountain D. C., Palka D., Ponganis P. J., Rommel S., Rowles T., Tyack P. L., Wartzok D., Gisiner R., Mead J., Benner L. (2006). Understanding the impacts of anthropogenic sound on beaked whales. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 7, 117–187 [Google Scholar]

- Denison D. M., Kooyman G. L. (1973). Structure and function of small airways in pinniped and sea otter lungs. Respir. Physiol. 17, 1–10 10.1016/0034-5687(73)90105-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison S., Moore M. J., Fahlman A., Moore K., Sharp S., Harry C. T., Hoppe J., Niemeyer M., Lentell B., Wells R. S. (2012). Bubbles in live-stranded dolphins. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279, 1396–1404 10.1098/rspb.2011.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsner R. (1999). “Living in water: solutions to physiological problems,” in Biology of Marine Mammals, eds Reynolds J. E., III., Rommel S. (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press; ), 73–116 [Google Scholar]

- Fahlman A., Olszowka A., Bostrom B., Jones D. R. (2006). Deep diving mammals: dive behavior and circulatory adjustments contribute to bends avoidance. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 153, 66–77 10.1016/j.resp.2005.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falke K. J., Hill R. D., Qvist J., Schneider R. C., Guppy M., Liggins G. C., Hochachka P. W., Elliott R. E., Zapol W. M. (1985). Seal lungs collapse during free diving – evidence from arterial nitrogen tensions. Science 229, 556–558 10.1126/science.4023700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A., Edwards J. F., Rodriguez F., De Los Monteros A. E., Herraez P., Castro P., Jaber J. R., Martin V., Arbelo M. (2005). “Gas and fat embolic syndrome” involving a mass stranding of beaked whales (Family Ziphiidae) exposed to anthropogenic sonar signals. Vet. Pathol. 42, 446–457 10.1354/vp.42-4-446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrigno M., Lundgren C. E. G. (2003). “Breath-hold diving,” in Physiology and Medicine of Diving, eds Brubakk A. O., Neuman T. S. (Edinburgh: Saunders; ), 153–180 [Google Scholar]

- Fick R. (1911). Zum Streit um dem Gelenkdruck. Anat. Hefte. 43, 397. 10.1007/BF02214688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitz-Clarke J. R. (2009). Risk of decompression sickness in extreme human breath-hold diving. Undersea Hyperb. Med. 36, 83–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis T. J. R., Simon J. M. (2003). “Pathology of decompression sickness,” in Bennett and Elliott’s Physiology and Medicine of Diving, eds Brubakk A. O., Neuman T. S. (Edinburgh: Saunders; ), 530–556 [Google Scholar]

- Gannier A. (1998). Variation saisonnière de l’affinité bathymétrique des cétacés dans le bassin Luguro-provençal (Méditerranée occidentale). Vie Milieu 48, 25–34 [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton R. W., Thalmann E. D. (2003). “Decompression practice,” in Bennett and Elliott’s Physiology and Medicine of Diving, eds Brubakk A. O., Neuman T. S. (Edinburgh: Saunders; ), 455–500 [Google Scholar]

- Harris M., Berg W. E., Whitaker D. M., Twitty V. C., Blinks L. R. (1945). Carbon dioxide as a facilitating agent in the initiation and growth of bubbles in animals decompressed to simulated altitudes. J. Gen. Physiol. 28, 225–240 10.1085/jgp.28.3.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey E. N. (1945). Decompression sickness and bubble formation in blood and tissues. Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 21, 505–536 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward A. T. J. (1967). Tribonucleation of bubbles. Br. J. Appl. Phys. 18, 641–644 10.1088/0508-3443/18/7/312 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy T. R. (1989). “On the site, origin, evolution and effects of decompression,” in Supersaturation and bubble formation in fluids and organisms, eds Brubakk A. O., Hemmingsen B. B., Sundnes G. (Trondheim: The Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters, The Foundation; ), 291–340 [Google Scholar]

- Hooker S., Baird R. W. (1999). Deep-diving behaviour of the northern bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus (Cetacea: Ziphiidae). Proc. Biol. Sci. 266, 671–676 10.1098/rspb.1999.0688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker S. K., Baird R. W., Fahlman A. (2009). Could beaked whales get the bends? Effect of diving behaviour and physiology on modelled gas exchange for three species: Ziphius cavirostris, Mesoplodon densirostris and Hyperoodon ampullatus. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 167, 235–246 10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker S. K., Fahlman A., Moore M. J., Aguilar De Soto N., Bernaldo De Quiros Y., Brubakk A. O., Costa D. P., Costidis A. M., Dennison S., Falke K. J., Fernandez A., Ferrigno M., Fitz-Clarke J. R., Garner M. M., Houser D. S., Jepson P. D., Ketten D. R., Kvadsheim P. H., Madsen P. T., Pollock N. W., Rotstein D. S., Rowles T. K., Simmons S. E., Van Bonn W., Weathersby P. K., Weise M. J., Williams T. M., Tyack P. L. (2012). Deadly diving? Physiological and behavioural management of decompression stress in diving mammals. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279, 1041–1050 10.1098/rspb.2011.2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser D. S., Dankiewicz-Talmadge L. A., Stockard T. K., Ponganis P. J. (2010). Investigation of the potential for vascular bubble formation in a repetitively diving dolphin. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 52–62 10.1242/jeb.028365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser D. S., Howard R., Ridgway S. (2001). Can diving-induced tissue nitrogen supersaturation increase the chance of acoustically driven bubble growth in marine mammals? J. Theor. Biol. 213, 183–195 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikels K. G. (1970). Production of gas bubbles in fluids by tribonucleation. J. Appl. Phys. 28, 524–527 [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama A. (1983). Analysis of gas composition of intra vascular bubbles produced by decompression. Bull. Tokyo Med. Dent. Univ. 30, 25–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson P. D., Arbelo M., Deaville R., Patterson I. A. P., Castro P., Baker J. R., Degollada E., Ross H. M., Herraez P., Pocknell A. M., Rodriguez F., Howie F. E., Espinosa A., Reid R. J., Jaber J. R., Martin V., Cunningham A. A., Fernandez A. (2003). Gas-bubble lesions in stranded cetaceans – was sonar responsible for a spate of whale deaths after an Atlantic military exercise? Nature 425, 575–576 10.1038/425575a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson P. D., Deaville R., Patterson I. A. P., Pocknell A. M., Ross H. M., Baker J. R., Howie F. E., Reid R. J., Colloff A., Cunningham A. A. (2005). Acute and chronic gas bubble lesions in cetaceans stranded in the United Kingdom. Vet. Pathol. 42, 291–305 10.1354/vp.42-3-291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil W., Bretsxhneider K., Patzelt D., Behning I., Lignitz E., Matz J. (1980). Luftembolie oder Fäulnisgas? Zur Dianostik der cardialen Luftembolie an der Leiche. Beitr. Gerichtl. Med. 38, 395–408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. M., Dodd D. C., Newson M. E., Roth L. (1989). The Necropsy Book. Ithaca: Charles Louis Davis, D.V.M. Foundation [Google Scholar]

- Knight B. (1996). Forensic Pathology. London: Arnold [Google Scholar]

- Kooyman G. L. (1973). Respiratory adaptations in marine mammals. Am. Zool. 13, 457–468 [Google Scholar]

- Kooyman G. L., Ponganis P. J. (1998). The physiological basis of diving to depth: birds and mammals. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 60, 19–32 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooyman G. L., Sinnett E. E. (1982). Pulmonary shunts in harbor seals and sea lions during simulated dives to depth. Physiol. Zool. 55, 105–111 [Google Scholar]

- Kuiken T., García-Hartmann M. (1991). “Dissection techniques and tissues sampling,” in 1st European Cetacean Society Workshop on Cetacean Pathology, Vol.17, Leiden [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C. (1997). Interpretation of gas in diving autopsies. SPUMS J. 27, 228–230 [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence C., Cooke C. (2006). Autopsy and the investigation of scuba diving fatalities. Diving Hyperb. Med. 36, 2–8 [Google Scholar]

- Lerner L., Lerner B. W. (2006). Decomposition. Available at: http://www.enotes.com/forensic-science/decomposition [accessed November 30, 2010].

- Martin V., Servidio A., Tejedor M., Arbelo M., Brederlau B., Neves S., Perez-Gil M., Urquiola E., Perez-Gil E., Fernandez A. (2009). “Cetaceans and conservation in the Canary Islands,” in 18th Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals. Quebec, Canada, 153 [Google Scholar]

- Mazzariol S., Di Guardo G., Petrella A., Marsili L., Fossi C. M., Leonzio C., Zizzo N., Vizzini S., Gaspari S., Pavan G., Podestà M., Garibaldi F., Ferrante M., Copat C., Traversa D., Marcer F., Airoldi S., Frantzis A., Bernaldo De Quirós Y., Cozzi B., Fernández A. (2011). Sometimes sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) cannot find their way back to the high seas: a multidisciplinary study on a mass stranding. PLoS ONE 6, e19417. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonough P. M., Hemmingsen E. A. (1984a). Bubble formation in crabs induced by limb motions after decompression. J. Appl. Phys. 57, 117–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonough P. M., Hemmingsen E. A. (1984b). Bubble formation in curstaceans following decompression from hyperbaric gas exposures. J. Appl. Phys. 56, 513–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonough P. M., Hemmingsen B. B. (1985a). A direct test for the survival of gaseous nuclei in vivo. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 56, 54–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdonough P. M., Hemmingsen E. A. (1985b). Swimming movements initiate bubble formation in fish decompressed from elevated gas-pressures. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Comp. Physiol. 81, 209–212 10.1016/0300-9629(85)90290-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J., Bogomolni A. L., Dennison S. E., Early G., Garner M. M., Hayward B. A., Lentell B. J., Rotstein D. S. (2009). Gas bubbles in seals, dolphins, and porpoises entangled and drowned at depth in gillnets. Vet. Pathol. 46, 536–547 10.1354/vp.08-VP-0065-M-FL [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J., Early G. A. (2004). Cumulative sperm whale bone damage and the bends. Science 306, 2215–2215 10.1126/science.306.5698.975b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M. J., Hammar T., Arruda J., Cramer S., Dennison S., Montie E., Fahlman A. (2011). Hyperbaric computed tomographic measurement of lung compression in seals and dolphins. J. Exp. Biol. 214, 2390–2397 10.1242/jeb.055020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muth C. M., Shank E. S. (2000). Primary care: gas embolism. New Engl. J. Med. 342, 476–482 10.1056/NEJM200002173420706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulev P. (1965). Decompression sickness following repeated breath-hold dives. J. Appl. Physiol. 20, 1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi C. A., Thalmann E. D. (2004). Pathology: whales, sonar and decompression sickness. Nature 428, 1–716; discussion 712–716. 10.1038/428001a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierucci G., Gherson G. (1968). Experimental study on gas embolism with special reference to the differentiation between embolic gas and putrefaction gas. Zacchia 4, 347–373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierucci G., Gherson G. (1969). Further contribution to the chemical diagnosis of gas embolism. The demonstration of hydrogen as an expression of “putrefactive component.” Zacchia 5, 595–603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponganis P. J., Kooyman G. L., Ridgway S. (2003). “Comparative diving physiology,” in Physiology and Medicine of Diving, eds Brubakk A. O., Neuman T. S. (Edinburgh: Saunders; ), 211–226 [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway S. H., Howard R. (1979). Dolphin lung collapse and intramuscular circulation during free diving – evidence from nitrogen washout. Science 206, 1182–1183 10.1126/science.505001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schipke J. D., Gams E., Kallweit O. (2006). Decompression sickness following breath-hold diving. Res. Sports Med. 14, 163–178 10.1080/15438620600854710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholander P. F. (1940). Experimental investigations on the respiratory function in diving mammals and birds. Hvalradets Skrifter 22, 1–131 [Google Scholar]

- Schorr G. S., Falcone E. A., Moretti D. J., McCarthy E. M., Hanson M. B., Andrews R. D. (2011). “The bar is really noisy, but the food must be good: high site fidelity and dive behavior of Cuvier’s beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostris) on an anti-submarine warfare range,” in 19th biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Tampa, FL, 265 [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Sivertsen J. (1976). “The origin of intravascular bubbles produced by decompression of rats killed prior to hyperbaric exposure,” in Proceedings of the Fifth Symposium on Underwater Physiology, ed. Lambertsen C. J. (Bethesda: Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology; ), 303–309 [Google Scholar]

- Tikuisis P., Gerth W. A. (2003). “Decompression theory,” in Physiology and Medicine of Diving, eds Brubakk A. O., Neuman T. S. (Edinburgh: Saunders; ), 419–454 [Google Scholar]

- Tyack P. L., Johnson M., Soto N. A., Sturlese A., Madsen P. T. (2006). Extreme diving of beaked whales. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 4238–4253 10.1242/jeb.02505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyack P. L., Zimmer W. M. X., Moretti D., Southall B. L., Claridge D. E., Durban J. W., Clark C. W., D’Amico A., Dimarzio N., Jarvis S., Mccarthy E., Morrissey R., Ward J., Boyd I. L. (2011). Beaked whales respond to simulated and actual navy sonar. PLoS ONE 6, e17009. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unit of Cetaceans Research U.L.P.G.C. (2006). Necropsies of Cetaceans Stranded in Canary Islands in 2006 Report. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Canary Islands Government [Google Scholar]

- Unit of Cetaceans Research U.L.P.G.C. (2007). Necropsies of Cetaceans Stranded in Canary Islands in 2007 Report. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Canary Islands Government [Google Scholar]

- Unit of Cetaceans Research U.L.P.G.C. (2008). Necropsies of Cetaceans Stranded in Canary Islands in 2008 Report. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Canary Islands Government [Google Scholar]

- Unit of Cetaceans Research U.L.P.G.C. (2009). Necropsies of Cetaceans Stranded in Canary Islands in 2009 Report. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Canary Islands Government [Google Scholar]

- Unit of Cetaceans Research U.L.P.G.C. (2010). Necropsies of Cetaceans Stranded in Canary Islands in 2010 Report. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Canary Islands Government [Google Scholar]

- Vann R. D., Butler F. K., Mitchell S. J., Moon R. E. (2011). Decompression illness. Lancet 377, 153–164 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61085-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vass A. A., Barshick S. A., Sega G., Caton J., Skeen J. T., Love J. C., Synstelien J. A. (2002). Decomposition chemistry of human remains: a new methodology for determining the postmortem interval. J. Forensic Sci. 47, 542–553 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watwood S. L., Miller P. O., Johnson M., Madsen J., Tyack P. L. (2006). Deep-diving foraging behaviour of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). J. Anim. Ecol. 75, 814–825 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2006.01101.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West K. L., Walker W. A., Baird R. W., White W., Levine G., Brown E., Schofield D. (2009). Diet of pygmy sperm whales (Kogia breviceps) in the Hawaiian archipelago. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 25, 931–943 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2009.00295.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheen L. C., Williams M. P. (2009). Post-mortems in recreational scuba diver deaths: the utility of radiology. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 16, 273–276 10.1016/j.jflm.2008.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T. M., Worthy G. A. J. (2002). “Anatomy and physiology: the challenge of aquatic living,” in Marine Mammal Biology, ed. Hoelzel A. R. (Oxford: Blackwell Science; ), 73–97 [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer W. M. X., Tyack P. L. (2007). Repetitive shallow dives pose decompression risk in deep-diving beaked whales. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 23, 888–925 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00152.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]