Fast dissolution-dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP)[1] is the latest and most successful attempt to solve the problem of low sensitivity in liquid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). The most prominent applications of this technology are in vitro and in vivo NMR spectroscopy and imaging with hyperpolarized 13C which has been used to study biochemical/metabolic activities in various tissues (heart, liver, tumors) in real time.[2–4] Non-biological applications of this technique include the monitoring of transient chemical kinetic reactions and fast sample characterization via one- and two-dimensional high resolution NMR spectroscopy.[5,6]

The choice of free radicals is critical in DNP. Mounting evidence[7–9] show that higher nuclear polarization levels can be achieved when radicals with narrower EPR linewidths D are used. Currently, the water soluble trityl-based stable free radicals (Figure 1) are the most frequently used polarizing agents in 13C and 15N dissolution DNP because their EPR linewidth is among the narrowest (D = 60–70 MHz).[9] Although the physical principles of DNP have been described in detail,[10] the chemical ramifications of the nature of the radical are not well understood yet. This research was initiated to explore other stable radicals as DNP polarizing agents. Here we demonstrate that the well-known 1,3-bisdiphenylene-2-phenylallyl (BDPA) radical may offer a viable alternative to trityl radicals in dissolution DNP. BDPA (Figure 1), first synthesized by Koelsch in 1957,[11] is one of the most stable carbon-centered free radicals. It has a comparable D to that of trityl radicals and has been used in polarized target experiments and solid-state DNP.[12–14] However, this radical has never been tried in dissolution DNP, most likely because it is practically insoluble in water and therefore, cannot be used in conventional water-based glassing mixtures such as a glycerol-water matrix. Our preliminary experiments have shown that BDPA is reasonably soluble (over 100 mM) in sulfolane, a dipolar aprotic solvent that can dissolve a wide range of compounds. Sulfolane (tetramethylene sulfone) is a crystalline solid at room temperature (m.p. = 27.5 °C); however, it forms a glass at low temperature when mixed with other solvents. To demonstrate the general applicability of BDPA as a DNP polarizing agent, we have polarized a number of compounds in the presence of this radical using the HyperSense commercial polarizer. The DNP experiments were performed as previously described.[1,2]

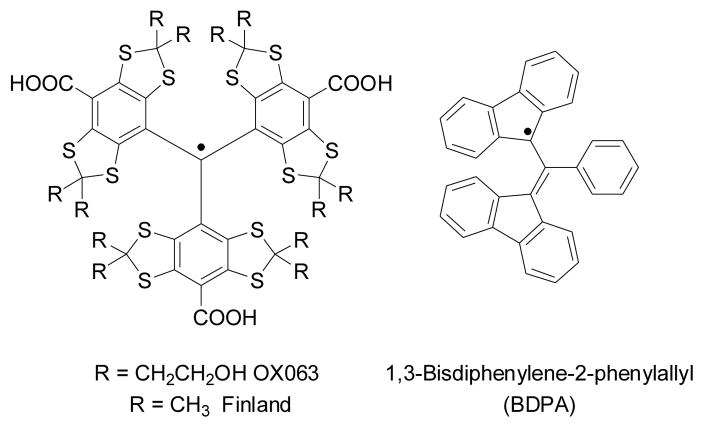

Figure 1.

Structure of free radical polarizing agents discussed in this work.

The data in Table 1 show that a variety of spin I= ½ nuclei with a gyromagnetic ratio ranging from γ = −2.086 MHz/T (89Y) to 17.24 MHz/T (31P) and an I=1 nucleus 6Li (γ = 6.2655 MHz/T) could be polarized with an efficiency comparable to or higher than what has been achieved with trityl radicals. The glassing mixtures usually consisted of sulfolane-diethylene glycol monobenzyl ether mixtures (Supporting Information). Samples containing water-soluble compounds were dissolved with 4 mL water after DNP. The use of water for dissolution offered a very simple way to remove the BDPA radical from the hyperpolarized sample: the radical naturally precipitated out from the solution and could be completely removed by a simple and rapid filtration (Supporting Information). The dissolution of hydrophobic substrates was carried out with methanol, in which the BDPA remained in solution.

Table 1.

Liquid-state NMR enhancements (N=3) measured 8 s after dissolution of various compounds polarized with BDPA (40 mM) and trityl OX063 (15 mM) in sulfolane-based glassing matrices (Supporting Information). The liquid-state T1 values and NMR enhancements were measured at 9.4 T and 298 K in unfiltered dissolution liquids.

| Nucleus/Compound | Dissolution solvent | T1 (s) | Enhancement BDPA (OX063) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C-pyruvic acida,c | water | 42 | 14,000 (12,000) |

| 13C-ureaa | water | 46 | 10,010 (10,160) |

| 13C-maleic acida | water | 30 | 8,250 |

| 13C-benzenea | methanol | 33 | 8,840 |

| 13C-tetramethylalleneb | methanol | 59 | 9,120 |

| 15N-cholinea | water | 215 | 8,000 (8,560) |

| 15N-pyridinea | water | 40 | 4,920 |

| 15N-nitrobenzenea | methanol | 100 | 7,880 |

| 31P-triMe phosphateb | water | 20 | 5,550 |

| 29Si-tetraethylsilaneb | methanol | 88 | 6,330 |

| 6LiCla | water | 273 | 6,480 |

| 89Y(acac)3b | methanol | 287 | 3,740 |

| 89Y(OTf)3b | waterd | 460 | 7,420 |

enriched

natural abundance

the dissolution liquid consisted of 15 mM NaHCO3

the dissolution liquid consisted of 10-fold excess of diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid solution (pH 7.8).

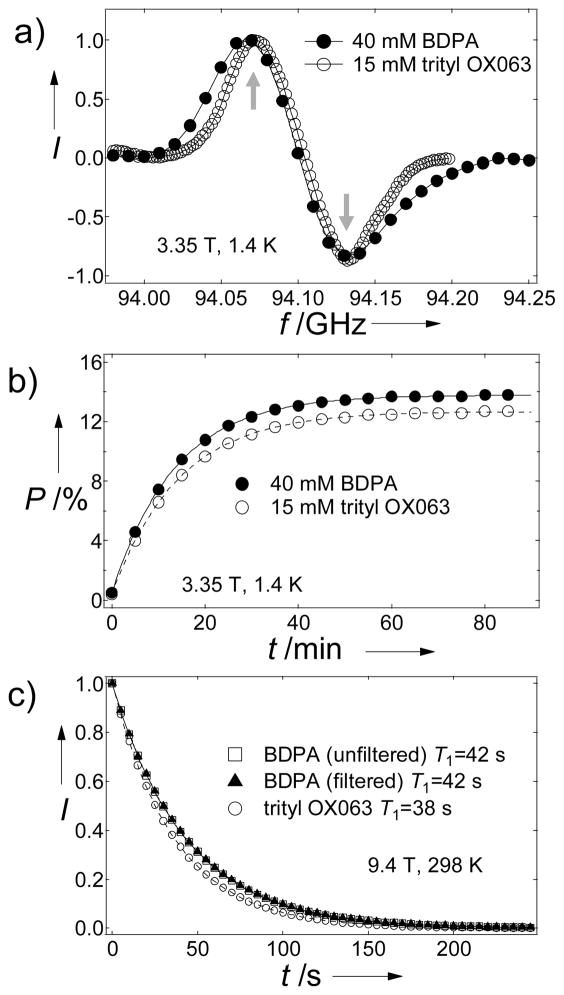

Due to its biological importance and favourably long longitudinal relaxation time T1, hyperpolarized [1–13C] pyruvic acid is frequently used to study metabolism in heart, liver, kidney, and tumors.[2–4] Here we demonstrate that BDPA in sulfolane is capable of producing large NMR enhancements of 13C pyruvic acid samples. The 13C DNP microwave spectra of [1-13C]pyruvic acid recorded in sulfolane in the presence BDPA and trityl OX063 almost overlap with a separation of 60–70 MHz between the positive and negative polarization peaks (Figure 2a). This close similarity of microwave 13C DNP spectra is the result of the comparable EPR linewidths of the two radicals, indicating the same dominant DNP mechanism (thermal mixing). The optimal concentration of BDPA in pyruvic acid-sulfolane (1:1) samples that would afford maximum polarization in approximately 1 hour of DNP irradiation time was 40 mM (Figures S1 and S2, Supporting Information). Figure 2b shows comparable solid-state 13C polarization P of [1-13C]pyruvic acid:sulfolane samples doped with the optimum concentrations of trityl OX063 (15 mM)[15] [P=12 %] and BDPA (40 mM) [P=14 %]. We note that DNP of neat [1-13C]pyruvic acid (self-glassing) doped with 15 mM trityl OX063 in the HyperSense yielded P=15 % while TEMPO-doped (40 mM) 13C pyruvate samples in glycerol:water matrix produced lower polarization (P=5.5 %) (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

a) Microwave DNP spectra of 1:1 [1-13C]pyruvic acid:sulfolane doped with BDPA (40 mM) (●) and trityl OX063 (15 mM) (○). The up and down arrows denote the positive [P(+)=94.06 GHz)] and negative [P(−)=94.13 GHz] polarization peaks, respectively. b) Polarization buildup curves of 13C pyruvic acid doped with BDPA(●) and OX063 (○) taken at P(+). c) Liquid-state T1 decay of 13C pyruvic acid samples: BDPA filtered (□), unfiltered (▲) and OX063 (○).

The average liquid-state NMR enhancement ε of BDPA-doped pyruvic acid:sulfolane sample was about 14,000 [P=11 %] times the thermal signal at 298 K in a 9.4 T magnet whereas the same sample doped with trityl yielded ε =12,000 [P=9.7 %]. The slight polarization decrease from solid-state to liquid-state is attributed mainly to T1 decay and field gradients experienced by the sample during dissolution transfer[16] (in our case, the tranfer time is 8 s). Upon dissolution, the BDPA separated out and could be removed from the hyperpolarized pyruvate solution by filtration (Figures S4 and S5, Supporting Information), while the trityl radical stayed in solution. The absence of BDPA radical in the dissolution liquid after filtration, an important consideration for the production of injectable liquid samples for in vivo experiments, was verified by UV-vis spectrophotometry (Figure S6, Supporting Information). The filtered and unfiltered dissolution liquids of samples polarized with BDPA had practically identical T1 values while the 13C T1 value was slightly shorter in the sample polarized with the trityl radical due to the paramagnetic effect of the dissolved radical (Figure 2c).

We managed to polarize several other water soluble compounds (maleic acid, choline, pyridine, trimethyl phosphate, and LiCl) to achieve high liquid-state NMR enhancements of 13C, 15N, 31P and 6Li nuclei (Table 1) which further demonstrate that BDPA works well with water-soluble substrates.

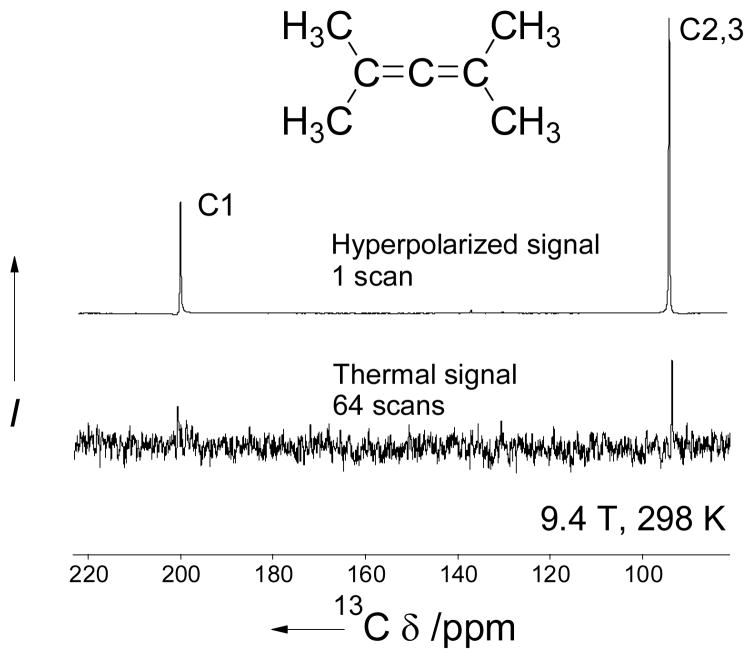

As one would expect, BDPA in sulfolane is extremely well suited for the hyperpolarization of water-insoluble aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons as well as other hydrophobic compounds (Table 1). While usually 13C-enriched substrates are used in in vivo hyperpolarized experiments, unlabeled compounds can also be polarized to produce high signal enhancement as demonstrated by the 13C DNP-NMR spectrum of nonlabeled tetramethylallene (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Hyperpolarized (1 scan) and thermal (64 scans) 13C NMR spectra of tetramethylallene after dissolution with methanol at 9.4 T and 298 K. The C4,5,6,7 NMR signal at 21 ppm (Figure S7, Supporting Information) is not shown here because of the lower intensity due to short T1.

In summary, we have shown that carbon-centered stable free radical BDPA is an efficient polarizing agent in dissolution DNP experiments not only for hydrophobic compounds but also for a number of hydrophilic substrates. Large signal enhancements of 13C, 15N, 31P, 6Li, 29Si, and 89Y nuclei have been achieved with BDPA using sulfolane-based glassing matrices. After the DNP of water-soluble compounds such as [1-13C]pyruvic acid or 15N-choline, when water is used as the dissolution solvent, the hydrophobic BDPA radical can conveniently be removed from the hyperpolarized solution by a simple and rapid mechanical filtration process. In addition, water-soluble derivatives of BDPA[17] may allow the use of water-containing glassing mixtures, thus widening the range of compounds that could be polarized with BDPA-based radicals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH grant numbers 1R21EB009147 and RR02584.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chemeurj.org/ or from the author.

References

- 1.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Storey C, Mark Jeffrey F, Dean Sherry A, Malloy Craig R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19773–19777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706235104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Brindle KM. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp. 2009;55:285–295. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Brindle K, Chekmenev EY, Comment A, Cunningham CH, DeBerardinis RJ, Green GG, Leach MO, Rajan SS, Rizi RR, Ross BD, Warren WS, Malloy CR. Neoplasia. 2011;13:81–97. doi: 10.1593/neo.101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen S, Hilty C. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;120:5313–5315. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frydman L, Blazina D. Nature Phys. 2007;3:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lumata L, Jindal AK, Merritt ME, Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Kovacs Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8673–8680. doi: 10.1021/ja201880y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goertz ST, Harmsen J, Heckmann J, Heb Ch, Meyer W, Radtke E, Reicherz G. Nuc Instr And Meth. 2004;526:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heckmann J, Meyer W, Radtke E, Reicherz G, Goertz S. Phys Rev B. 2006;74:134418. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abragam A, Goldman M. Rep Prog Phys. 1978;41:395–467. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koelsch CF. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;22:4439–4441. [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Boer W. J Low Temp Phys. 1976;22:185–212. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu JZ, Zhou J, Yang B, Li L, Qiu J, Ye C, Solum MS, Wind RA, Pugmire RJ, Grant DM. Sol St Nuc Magn Res. 1997;8:129–137. doi: 10.1016/s0926-2040(96)01263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becerra LR, Gerfen GJ, Temkin RJ, Singel DJ, Griffin RG. Phys Rev Lett. 1993;71:3561–3564. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolber J, Ellner F, Fridlund B, Gram A, Johannesson H, Hansson G, Hansson LH, Lerche MH, Mansson S, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. Nuc Instr And Meth. 2004;526:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mieville P, Jannin S, Bodenhausen G. J Magn Reson. 2011;210:137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dane EL, Swager TM. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3533–3536. doi: 10.1021/jo100577g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.