Abstract

Individuals who suffer from acid reflux at night, who snore chronically, or who have sleep apnea are frequently encouraged to sleep in a particular lying position. Side sleeping decreases the frequency and severity of obstructive respiratory events (e.g. apnea and hypopnea) in patients with positional sleep apnea. It has been suggested that individuals with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease sleep on their left sides in order to help minimize symptoms. In this paper, we present a method of predicting the position of an individual lying on the bed using load cells placed under each of the bed supports. Our results suggest that load cells utilized in this manner could be successfully implemented into a system that tracks or helps train individuals to sleep in a particular lying position.

I. Introduction

Sleeping position is a clinically relevant parameter that must be taken into consideration when dealing with several sleep disturbances. Research has shown that for individuals who suffer from Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (acid reflux) the optimal sleeping position is to lie on the left side [1]. Sleep apnea - which is associated with several cardiovascular diseases [2] and is estimated to occur in up to 24% of middle aged men and 9% of middle aged women [3] - is frequently exacerbated by sleeping position. Many studies have shown that lying on one’s side or the lateral decubitus position will reduce the number of apneic events as compared to lying on one’s back or the supine sleeping position [4–6]. A similar positional effect has been observed in non-apneic snorers [7]. In patients with significant apnea exclusively in the supine position, treatment may consist of simply avoiding supine sleep. Other patients may require more sophisticated positive airway pressure treatment therapy or supplemental oxygen therapy in combination with positional restriction. This positional effect seen in sleep apnea led to development of techniques that encourage patients to sleep on their sides. Night shirts or specially designed belts containing lightweight large volume objects positioned over the back have been used with variable success to prevent sleeping in the supine position. Gravity sensors strapped to the chest have been used in an attempt to train patients to sleep on their sides by activating an alarm when the patient rolls onto their back [8]. Whether used to improve patient awareness of position or to monitor patient compliance with position restriction, an unobtrusive method for collecting this data without affecting sleep is needed.

Several groups, including our lab, have and are currently investigating the utility of using load cells placed under the supports of a bed as a means to make inferences about an individual’s sleep. Load cells are able to detect [9, 10] and classify [11] movements on the bed. Load cells can be used to monitor sleep hygiene by tracking a person’s in-bed and out-of-bed states [12]. It has also been shown that load cells placed under the bed are sensitive enough to detect an individual’s respiration [10] and heart beats [10, 13–15]. Recently in our lab, we demonstrated the ability of load cell data to discriminate apneic events from normal breathing [16]. In this paper, we introduce the use of load cells placed under the supports of a bed as a method for detecting lying position of an individual on top of the bed.

II. Methods

A. Subjects

Nineteen healthy subjects were recruited from a convenience sample to participate in the study. Eleven subjects were female and 8 were male. The average age was 30.5 years and the average BMI was 24.9 kg/m2.

B. Setup

Each participant was outfitted with respiration belts around both their chest and abdomen, a nasal pressure cannula placed in their nostrils, a finger pulse oximeter attached to their right index finger, and 5 tri-axial accelerometers (PAM-RL, Phillips Respironics, OR, USA), one attached to each wrist and each ankle, and one placed around their abdomen. One load cell (AG 100C3SH5eU, SCAIME, Annemasse, France) was installed under each of the 4 supports of a full sized bed for a total of 4 load cells. To prevent aliasing, the load cell signals were filtered using a 4 pole Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 150 Hz before being digitized at 2 kHz using a 16-bit A/D converter (USB-1608FS, Measurement Computing, Norton, MA).

C. Data Collection

The study participants were instructed to lie on the bed and breathe normally without any extraneous movements except when explicitly instructed to move. The experiment lasted 32 minutes during which time the participants were instructed using a prerecorded message to lie in 4 different positions. The participants spent 8 minutes lying in each of the following positions: back, left side, right side, and stomach. The interpretation of how to lie in each of these positions was left up to the discretion of each participant. At the 2.5 and 5 minute mark after having assumed each of the 4 positions, the participants were prompted to shift the position of either their arm(s) or leg(s). Once again, the particular movement of the arm or leg was left to the participant’s own interpretation. The study protocol was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board.

D. Data Analysis

For every participant, the signals from each load cell were first low passed filtered and decimated to a sampling rate of 2 Hz. The center of pressure (CoP) of the weight on the bed in both the x and y-directions - the x-direction being parallel to the short axis of the bed and the y-direction being parallel to the long axis - were calculated using:

| (1) |

where di is the [x,y] location of the ith load cell in a Cartesian coordinate system and LCi(t) is the force measured by the ith load cell at time t (see Fig. 1). In order to isolate the respiration signal, the CoP signal was low-pass filtered using a 4th order Chebyshev Type II filter that was monotonic in the pass-band, had a stop-band edge frequency of 0.7 Hz, and attenuated the stop band by 30 dB. From each subject’s CoP signal, 24 movement free minutes were selected for analysis comprised of three 2 minute periods (total = 6 minutes) of quiescent breathing for each of the four body positions (back, right, left, stomach). Following sleep study convention, the 6 minute periods were divided into 30 second segments for a total of 12 epochs per position.

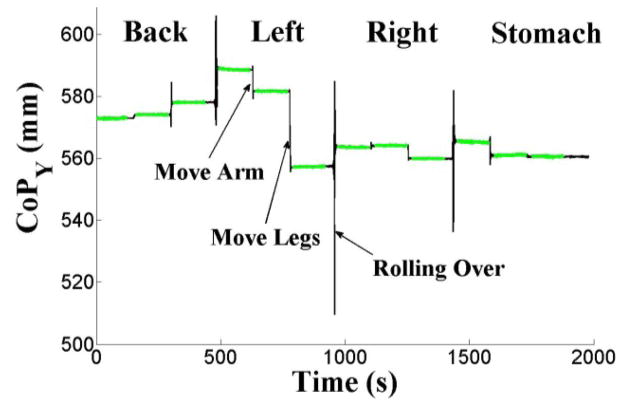

Fig. 1.

Approximately 30 minutes of decimated CoP load cell signal in the y-direction (i.e. parallel to the long axis of the bed) for a participant lying in the back, left, right, and stomach positions. Examples of small movements (leg and arm) and a large movement (rolling over) are marked. Data utilized for analysis is marked in green.

It was our conjecture that as an individual lies quietly on the bed and breathes, the visceral organs are displaced in rhythmic pattern following the respiration that can be detected by the load cells (i.e. CoP signal). We further hypothesized that the relative angle of displacement (ANG) on a breath by breath basis in the xy plane could be indicative of the position that an individual is lying in on top of the bed. Therefore, from each 30 second epoch, we calculated the ANG for each breath in the CoP signal using:

| (2) |

where PeakCoPy is the value of CoP in the y-direction at time point ‘t’ which represents the end of expiration for the preceding breath and the beginning of inspiration for the coming breath. TroughCoPy represents the y-value of CoP at either the beginning of expiration for the preceding breath or the end of inspiration for the following breath. CoPx represents the corresponding displacement of CoP in the x-direction for either time ‘t’ or time ‘t±Δt’.

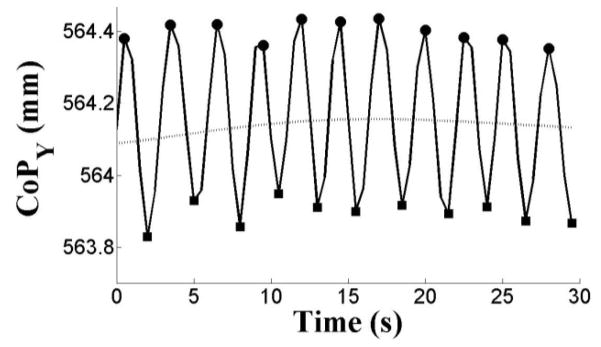

Since the majority of the displacement of the CoP is in the y-direction during respiration, the end of expiration and beginning of inspiration occur at the point of maximum displacement in the y-direction. Conversely, the beginning of expiration and ending of inspiration occur at the point of least deflection in the y-direction. Therefore, we are able to determine PeakCoPy by detecting the local peaks in the y-direction of the CoP signal and the local troughs representing TroughCoPy (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Example of local peak (filled in circles) and local trough (filled in squares) detection in the y-direction of the CoP (solid line) load cell signal. The peaks and troughs were detected by first estimating the trend (dotted line) of the CoP signal in the y-direction using a 2nd order low pass Chebyshev Type II filter that was monotonic in the pass-band, had a stop-band edge frequency of 0.1 Hz, and attenuated the stop band by 30 dB. Peaks were detected by finding the point of maximum value during the period that CoPy was greater than the trend. The local troughs were then defined as the minimum value between consecutive peaks.

The mean of the population of angles for each 30 second epoch was calculated as a representative of the overall ANG. K-means was then utilized to segregate all the 30 second observations (i.e. mean of displacement angles) into k clusters by iteratively minimizing the sum of all the squared Euclidian distances between each jth 30 second observation (Oj) and the respective mth centroid (Cm):

| (3) |

The 30 second observations for each participant were first classified using K-means on an individual basis using 4 centers – one for each position (back, right, left, stomach). Then the observations for all subjects were combined, and K-means was used to obtain a generalized classification for the k = 4 centers case. Finally, both individual and generalized K-means clustering were re-run using 3 centers under the hypothesis that the back and stomach position may be similar enough that they would cluster together. The accuracy for each K-means classification was calculated in a hierarchal manner. First, the cluster containing the majority of ‘back’ observations was considered to be the ‘back’ cluster. Then the cluster containing the majority of ‘right’ observations was considered to be the ‘right’ cluster unless it had already been defined as the ‘back’ cluster. In which case, the cluster with the next highest occurrence of ‘right’ observations was deemed the ‘right’ cluster. This process was repeated for the ‘left’ observations next and then finally the ‘stomach’ observations. The ‘back’ and ‘stomach’ observations were simply combined for the K-means analysis using k = 3 centers. Finally, the accuracy of classification for each lying position was calculated as the number of a particular position’s observations in the correct cluster divided by the total number of that position’s observations.

III. Results

Table I contains the participant demographics together with the accuracy using 3 or 4 K-means centers for each participant. Combining the observations for all the subjects into a single classifier resulted in generalized accuracies of 0.68, 0.57, 0.69, and 0.33 for the back, right, left, and stomach positions respectively. In contrast, the generalized accuracies for k = 3 classes were 0.92, 0.75, and 0.86 for the back/stomach, right, and left positions respectively.

TABLE I.

Individual K-Means Results & Participant Demographics

| K-Means (k = 4 centers) | K-Means (k = 3 centers) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Gender | Age | BMI | Back | Right | Left | Stomach | B./Stom. | Right | Left |

| 1 | M | 25 | 21.6 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.97 |

| 2 | F | 28 | 32.3 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.73 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.63 |

| 3 | F | 23 | 22.6 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.38 |

| 4 | F | 22 | 20.3 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.10 | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.55 |

| 5 | M | 36 | 22.7 | 0.71 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.80 |

| 6 | M | 43 | 29.7 | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.70 |

| 7 | F | 25 | 19.4 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.88 | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.92 |

| 8 | F | 29 | 23.8 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| 9 | F | 35 | 23.3 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.95 |

| 10 | M | 29 | 37.7 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.90 |

| 11 | F | 26 | 22.4 | 1.00 | 0.34 | 0.83 | 0.40 | 0.97 | 0.40 | 0.92 |

| 12 | M | 25 | 21.3 | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.43 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.90 |

| 13 | M | 39 | 24.4 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 1.00 |

| 14 | F | 32 | 29.7 | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.90 | 0.23 | 0.85 | 0.30 | 0.97 |

| 15 | M | 31 | 26.6 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.93 |

| 16 | M | 28 | 23.6 | 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 0.43 | 0.89 | 0.53 | 0.95 |

| 17 | F | 25 | 21.3 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| 18 | F | 56 | 33.3 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

| 19 | F | 23 | 17.7 | 0.70 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.45 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.00 |

| Means | 30.5±8.4 | 24.9±5.3 | 0.92±0.11 | 0.75±0.20 | 0.84±0.13 | 0.34±0.22 | 0.92±0.10 | 0.73±0.20 | 0.85±0.17 | |

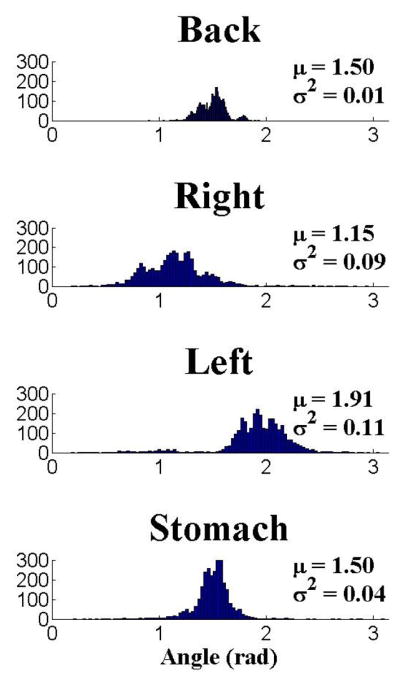

Fig. 3 contains histograms for all the angle estimations for every participant at every lying position. The histograms show the similarity in the angles for both the back and stomach lying positions which most likely accounts for the poor accuracy of the stomach position in the k = 4 centers case and the high accuracy for all three positions when the back and stomach lying positions were combined.

Fig. 3.

Histograms showing the distribution of all the angles of displacement estimated for all the participants. An angle of π/2 corresponds to a vertical displacement parallel to the y-axis of the bed. Notice the similarity of the mean (μ) displacement for the back and stomach lying positions and the apparent differences in the mean displacement angles for the back/stomach, right, and left lying positions. The off-vertical displacement angles for the right and left lying positions are likely attributed to the horizontal component added by the distention of the visceral organs in the x-direction as one lies on their side.

IV. Discussion

Our results demonstrate the feasibility of using load cells placed under the supports of a bed to classify the position of an individual lying on the bed. Using load cells in this manner could be beneficial for patients suffering from sleep apnea, snoring, and acid reflux where the severity of their condition is sleeping position dependent. Conceptually, the load cells could be integrated into a system that warns/informs the patient when they have assumed a non-ideal sleeping position.

When interpreting the results presented herein, some limitations must be kept in mind. First, participants were allowed to assume lying positions at their own discretion. Therefore, in some instances, a participant’s interpretation of a lying position could have had a negative effect on our results. For example, we noted that participant #14 spent 1/3 of her time lying on her left side in a position that appeared to be half on her side and half on her stomach. It was also noted that 2/3 of her time spent lying on her right side was in a position that appeared to be a combination of lying on her right side and lying on her back.

The second limitation of our study is that it is based upon the estimated ANG of the CoP breathing signal. It is feasible that this could lead to confusion between an individual lying on their side versus them lying on their back at a slight angle. Similarly, polysomnography fails to discriminate prone or supine from ambiguous lateral positions. This may be caused by signal loss, artifact or disagreement between head shoulder and hips during a given position which can not be reconciled despite utilization of wired position sensors applied to the patient and visual inspection of video. Our method identified left lateral from right lateral positions relatively well and future work will include development of a model to better differentiate prone from supine.

In our lab, our main focus is on using the load cell system to detect and monitor patients with sleep apnea [16], where sleeping position may alter the characteristic respiration signal detected by the load cells. We are encouraged by the results presented herein. We have previously shown that large movements (i.e. posture shifts) are easily detected by the load cell system [9]; therefore, it is only necessary to accurately predict the sleeping position between two known position shifts the majority of the time in order to correctly estimate the lying position for the entire segment. We expect the ability to determine an individual’s sleeping position will aid our ability to develop an algorithm for automatically detecting sleep apnea.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NHLBI grant R01HL098621.

Contributor Information

Zachary T. Beattie, Email: beattiez@bme.ogi.edu, Graduate student in the Biomedical Engineering department, Oregon Health & Science University. 3303 SW Bond Avenue, Portland, OR 97239 USA; phone: 503-418-9302.

Chad C. Hagen, Email: chagenmd@snoreweb.com, Pacific Sleep Program, 11790 SW Barnes Road, Ste 330, Portland OR 97225 USA

Tamara L. Hayes, Email: hayest@bme.ogi.edu, Biomedical Engineering department, Oregon Health & Science University. 3303 SW Bond Avenue, Portland, OR 97239 USA.

References

- 1.Khoury RM, Camacho-Lobato L, Katz PO, Mohiuddin MA, Castell DO. Influence of spontaneous sleep positions on nighttime recumbent reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2069–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redline S, Budhiraja R, Kapur V, Marcus CL, Mateika JH, Mehra R, Parthasarthy S, Somers VK, Strohl KP, Sulit LG, Gozal D, Wise MS, Quan SF. The scoring of respiratory events in sleep: reliability and validity. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:169–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartwright RD. Effect of sleep position on sleep apnea severity. Sleep. 1984;7:110–4. doi: 10.1093/sleep/7.2.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George CF, Millar TW, Kryger MH. Sleep apnea and body position during sleep. Sleep. 1988;11:90–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips BA, Okeson J, Paesani D, Gilmore R. Effect of sleep position on sleep apnea and parafunctional activity. Chest. 1986;90:424–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakano H, Ikeda T, Hayashi M, Ohshima E, Onizuka A. Effects of body position on snoring in apneic and nonapneic snorers. Sleep. 2003;26:169–72. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartwright RD, Lloyd S, Lilie J, Kravitz H. Sleep position training as treatment for sleep apnea syndrome: a preliminary study. Sleep. 1985;8:87–94. doi: 10.1093/sleep/8.2.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adami AM, Pavel M, Hayes TL, Singer CM. Detection of movement in bed using unobtrusive load cell sensors. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2010;14:481–90. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2008.2010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brink M, Muller CH, Schierz C. Contact-free measurement of heart rate, respiration rate, and body movements during sleep. Behav Res Methods. 2006;38:511–21. doi: 10.3758/bf03192806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adami AM, Hayes TL, Pavel M, Singer CM. Detection and classification of movements in bed using load cells. presented at 27th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; Shanghai, China. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adami AM, Adami AG, Schwarz G, Beattie ZT, Hayes TL. A subject state detection approach to determine rest-activity patterns using load cells. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2010;2010:204–7. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5627935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi BH, Chung GS, Lee JS, Jeong DU, Park KS. Slow-wave sleep estimation on a load-cell-installed bed: a non-constrained method. Physiol Meas. 2009;30:1163–70. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/30/11/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung GS, Choi BH, Jeong DU, Park KS. Noninvasive heart rate variability analysis using loadcell-installed bed during sleep. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2007;2007:2357–60. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4352800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin JH, Choi BH, Lim YG, Jeong DU, Park KS. Automatic ballistocardiogram (BCG) beat detection using a template matching approach. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008;2008:1144–6. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4649363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beattie ZT, Hagen CC, Pavel M, Hayes TL. Classification of breathing events using load cells under the bed. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2009;2009:3921–4. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]