Abstract

We report on the development and online testing of an EEG-based brain-computer interface (BCI) that aims to be usable by completely paralysed users—for whom visual or motor-system-based BCIs may not be suitable, and among whom reports of successful BCI use have so far been very rare. The current approach exploits covert shifts of attention to auditory stimuli in a dichotic-listening stimulus design. To compare the efficacy of event-related potentials (ERPs) and steady-state auditory evoked potentials (SSAEPs), the stimuli were designed such that they elicited both ERPs and SSAEPs simultaneously. Trial-by-trial feedback was provided online, based on subjects’ modulation of N1 and P3 ERP components measured during single 5-second stimulation intervals. All 13 healthy subjects were able to use the BCI, with performance in a binary left/right choice task ranging from 75% to 96% correct across subjects (mean 85%). BCI classification was based on the contrast between stimuli in the attended stream and stimuli in the unattended stream, making use of every stimulus, rather than contrasting frequent standard and rare “oddball” stimuli. SSAEPs were assessed offline: for all subjects, spectral components at the two exactly-known modulation frequencies allowed discrimination of pre-stimulus from stimulus intervals, and of left-only stimuli from right-only stimuli when one side of the dichotic stimulus pair was muted. However, attention-modulation of SSAEPs was not sufficient for single-trial BCI communication, even when the subject’s attention was clearly focused well enough to allow classification of the same trials via ERPs. ERPs clearly provided a superior basis for BCI. The ERP results are a promising step towards the development of a simple-to-use, reliable yes/no communication system for users in the most severely paralysed states, as well as potential attention-monitoring and -training applications outside the context of assistive technology.

Keywords: brain-computer interface (BCI), auditory event-related potentials (ERP), N100, P300, steady-state evoked potentials, auditory steady-state responses, dichotic listening, auditory attention

1. Introduction

The aim of research into brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) is to develop systems that allow a person to interact with his or her environment using signals from the brain, without the need for any muscular movement or peripheral nervous system involvement—for example, to allow a completely paralysed person to communicate. Total or near-total paralysis can result in cases of brain-stem stroke, cerebral palsy, and amytrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease). It has been shown [1] that some people in a “locked-in” state (LIS), in which most cognitive functions are intact despite almost-complete paralysis, can learn to communicate via an interface that interprets electrical signals from the brain, measured externally by electro-encephalogram (EEG). However, for people in the so-called “completely-locked-in” or “totally-locked-in” state (CLIS or TLIS), in which absolutely no communication is possible via muscular movement, successful communication even via BCI has proved more elusive [2]—although there have been some encouraging early reports of success [3].

There is, therefore, still considerable room for development of BCI systems targeted at those people, in the most-severely paralysed states, who need the technology most. The majority of BCI studies have so far been devoted to one of two approaches: the first approach is the exploitation of event-related potentials (ERPs) in response to visual stimuli [after 4, 5]. However, this is rather unsuitable for people in TLIS, whose eye movements are uncontrollable or entirely absent—among other problems, the inability to direct gaze, focus to the desired depth, or blink the eye to prevent corneal disease and eye infections, all tend to add up to very poor spatial vision or none at all. The second popular approach is based on signals from the motor and pre-motor cortex in response to imagined muscle movements However, since TLIS often results from progressive degeneration of the motor system, it is still unclear for how long users in TLIS, having hypothetically made the breakthrough of using such a system successfully in TLIS, might continue to be able to rely on motor-system signals in this way.

Hence there is considerable motivation to continue exploring BCI modalities that have been relatively little explored in the literature: those based on non-motor mental tasks such as the mental calculation and music imagery tasks used by Naito et al. [3], or those based on attention to tactile stimuli [e.g. 6, 7] or auditory stimuli [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. The current design is a development of the first such auditory approach to be published [8]. It is based on voluntary shifts of attention in a two-stream (and in the current paper, dichotic) listening task. Two sequences or “streams” of auditory stimuli are played simultaneously, and the user may make a binary decision by focusing on one stream and ignoring the other. This leads to a modulation of ERPs in response to the stimuli of the two streams—an effect reported in 1973 by Hillyard et al. [16], which Hill et al. [8] showed could be classified on a single-trial basis for potential use in BCI.

1.1. BCIs driven by Auditory Event-Related Potentials

Various auditory-ERP-based BCI approaches have been reported since 2005. In table 1.1, these are categorized according to whether they used a streaming or sequential stimulus arrangement.

Table 1.

Auditory-ERP-based BCI studies

| Study | Interface design | Stimulus Arrangement | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hill et al. 2005 [8] | binary choice | streaming | offline |

| Sellers & Donchin 2006 [9] | 4-way choice | sequential | offline |

| Furdea et al. 2009 [10, 17] | 5+5-choice speller | sequential | online |

| Klobassa et al. 2009 [11] | 6+6-choice speller | sequential | online |

| Kanoh et al. 2010 [12] | binary choice | streaming | offline |

| Halder et al. 2010 [13] | binary choice | sequential | offline |

| Schreuder et al. 2009,2010 [18, 14] | 6+6-choice speller | sequential | offline |

| Schreuder et al. 2011 [19] | 6+6-choice speller | sequential | online |

| Belitski et al. 2011 [20] | 6+6-choice speller | sequential | online |

| Höhne et al. 2010,2011 [21, 15]: | 9-choice speller | sequential | online |

In streaming approaches, users may or may not be asked to monitor the attended stream for particular (relatively infrequent) target stimuli. However, the BCI is driven not by the contrast of target responses vs. non-target responses, but rather by the contrast between responses to stimuli in the attended stream vs. responses to stimuli in the unattended stream. The stimuli used for this contrast could be non-targets, targets (if present in the design), or both.

In sequential approaches, by contrast, the user monitors a single stream for a target stimulus, and it is the brain response to the target that carries the crucial information. This has a disadvantage in the two-class case, that the system must wait longer between information-bearing stimuli. However, it has the distinct advantage that the stream may consist of a large number of different targets, allowing a multi-way choice. Two or more multi-way choices, made in succession, allow a letter to be selected in a spelling application, provided the user is sufficiently familiar with the layout of letters in, for example, a grid [10, 17, 11, 15] or a nested pattern of hexagons [14]. For a subject able to use both systems, a fully-fledged spelling application is clearly superior to a binary chooser considered in isolation. For now, however, our aim is not to design a full speller, but rather to create a reliable binary interface that places little demand on working memory. The long-term aim is that this might be useful for re-establishing simple, initial contact with a person who has entered the totally-locked-in state—either as a basis for, or as a stepping-stone towards, more sophisticated communication). Hence, we continue to pursue the streaming method.

Table 1.1 also categorizes the studies as presenting either “offline” or “online” analyses. Both of the streaming studies, and some of the sequential studies, assessed classification performance offline (i.e. by dividing data into training and test sets after all the data were gathered). A vital step in developing such methods for BCI is to ensure that the system works online (i.e. that the system can act on its interpretation of a decision made by the user, and report this to the user, in time for the user to make the next decision). One function of the current paper is therefore to provide an in-depth assessment of online performance of the streaming approach. The second goal is to use the online attention paradigm as a platform for investigating the usefulness of a second class of brain signal, as described in the following section.

1.2. Steady-State Evoked Potentials

A very different approach to auditory stimulus-driven BCI was attempted by Kallenberg [22] using a streaming design, and by Farquhar et al. [23] using both streaming and sequential designs. Here, the focus was on a different class of brain responses known as steady-state auditory evoked potentials (SSAEP) or auditory steady-state responses (ASSR). These are sustained responses to continuous, fluctuating stimuli [24]. They are typically elicited by trains of click stimuli, tone pulses, or amplitude-modulated tones, with a repetition or modulation rate between 20 and 100 Hz. The resulting brain response can be localized in primary (and, for lower frequencies, also secondary) auditory cortex [25] and are frequency-matched and phase-locked to the modulation. Ross et al. [26] found that the largest signal-to-noise ratio was produced by modulation frequencies around 40Hz, and indeed this is the frequency typically used in many SSAEP studies.

For BCI use, first the signal needs to be able to be modified by the user’s voluntary shifts of attention; second, this modulation needs to be detectable on a single-trial basis, where a “trial” lasts some reasonably small number of seconds. Steady-state evoked potentials in other modalities have been shown to meet these criteria. Visual SSEPs are well-established as a basis for BCI, with users able to modulate them by overt [27] or covert [28, 29, 30] shifts of attention to spatial [27, 28] or non-spatial [29, 30] aspects of a stimulus array. Promising results have also been shown for somatosensory SSEPs [6].

Auditory SSEPs, however, have had more difficulty in living up to this promise. A 1987 EEG study [31] failed to find any significant attention-modulation of SSAEPs at all, and it took another 17 years for a measurable effect to be found: first in MEG using a cross-modal paradigm [32], then using pure-auditory streaming designs in ECoG [33] and MEG[34], and finally in EEG using a sequential design [35].

In their attempts at single-trial classification, both Kallenberg [22] and Farquhar et al. [23] report performance below that is mostly below 65%. This is well below the level of performance at which one can expect to construct any kind of BCI system for independent use. Lopez et al. [36] also reported significant attention-modulation of SSAEPs in their offline analysis of a BCI-like experiment, but concluded that the effect may still be too weak for practical use since the time required per trial (over 40 seconds) was excessively long. Most recently, Kim et al. [37] have shown slightly more encouraging preliminary results from an SSAEP-based BCI system using 20-second stimuli (however,see the Discussion section, below). Note that offline performance levels in all these studies was significantly above chance: they do at least, therefore, add to the evidence that SSAEPs can be modulated by attention at all. However, for BCI, which requires high classification accuracy in a short time, the results seem discouraging.

Nonetheless, it is impossible to draw definitive conclusions from studies that fail to find a large effect, since any such failure can be ascribed to a large number of potential factors. For example, these previous studies did not verify, in any independent and objective way, the extent to which subjects were able to focus their attention on one stimulus and ignore the other. It may be, therefore, that some aspect of the stimulus or task design made it difficult for subjects to shift their attention optimally. The current study aims to control for this possibility: it uses the existing auditory-ERP-based BCI design to confirm that subjects can indeed modulate their attention in a single-trial-classifiable way, while at the same time, and in the same stimuli, introducing frequency “tagging” to examine the effects of attention on SSAEPs.

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Subjects were 13 healthy participants (9 male, 4 female) with an age range of 23–37 years (27.8 ± 4.6). All subjects were right-handed, had corrected-to-normal vision and no history of significant hearing defects. They had answered public advertisements for experimental subjects, had given informed consent, and were paid for their participation. Experiments were performed at, and approved by, the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics. No subjects were excluded from the analysis.

2.2. Stimuli and task design

One trial was defined as the attempt to make one binary choice (left or right). One block consisted of 20 trials and lasted about 5 mins. After each block, the subject could rest for a few minutes if they so desired. In a single sitting lasting two hours (excluding setup), each subject performed ten 20-trial blocks of the normal attention condition, for a total of 200 attention trials. For comparison with the studies of Kallenberg [22] and Farquhar et al. [23], a perception condition was included: here, the instructions and task are the same, as are the stimuli except in that the unattended stream is silent. Two 20-trial blocks of the perception condition were performed: one right at the beginning of the measurement period (which helped in introducing the task to the subject) and one half-way though the session between attention blocks, for a total of 40 perception trials per subject.

At the start of each trial, subjects were given a visual cue (either the word “LEFT” or the word “RIGHT” appearing in the centre of the screen for 2 seconds) instructing them which stream to attend to. Half the trials in a given block were left, and half were right, in random order. The very last block was an exception to this: it was a free-choice attention block in which, instead of an explicit instruction, the word “CHOOSE” appeared for 3 seconds, during which subjects decided freely whether to choose left or right, and wrote their choice down on paper. The purpose of this was to verify, for the benefit of both subject and experimenter, that the system’s classification performance must be based on the EEG input alone.

Subjects were instructed that, from the moment the cue appeared, they should keep their gaze fixed on the centre of the screen, and refrain as much as possible from blinking, swallowing or moving. After 2 seconds (or 3 in the free-choice block), the cue was replaced by a fixation cross and the sound stimulus began.

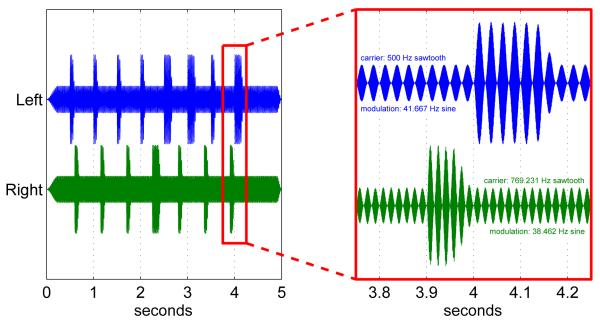

The stimulus is illustrated in Figure 1. It lasted 5 seconds in total including 250-msec attack and decay periods. The stimulus was dichotic: a different stimulus stream was presented to each ear. Each stream consisted of an anti-aliased sawtooth carrier wave (500 Hz on the left, 769.231 Hz on the right), amplitude-modulated to 100% depth by a sine wave (41.667 Hz on the left, 38.462 Hz on the right). For most of the time, the peak-to-peak amplitude of the stimulus was at 30% of the soundcard’s maximum output. However, starting at 504 msec on the left, and 598 msec on the right, the stimulus began to “pulse”: that is, with a raised-cosine attack of 5 msec, a plateau lasting 45 msec, and a decay of 50 msec, the amplitude of the stimulus was raised to 100% output. These pulses were repeated with a period of 504 msec (left) and 546 msec (right), for a total of 8 on the left and 7 on the right. The pulses were designed to elicit ERPs, analogously to the beeps of Hill et al. [8].

Figure 1.

An example of the dichotic stimulus used on each trial. Amplitude-modulation at close to 40 Hz induces auditory steady-state responses, whereas the periodic “pulsing” induces event-related potentials. Target pulses for the counting task are longer than standard pulses (in this example there are 3 targets in the left stream and 1 in the right).

These parameters were chosen by hand over the course of several exploratory parameterizations and pilot experiments, to meet multiple criteria: AM frequencies should be as close as possible to 40 Hz (in order to produce measurable SSAEP responses from as many subjects as possible) while still being distinguishable from each other in the EEG; AM cycles should last an integer number of EEG samples (to aid in analysis); carrier frequencies should be integer multiples of the modulation frequency (to aid in stimulus generation); pulse periods should be such that responses to pulses on the left are minimally correlated with responses to pulses on the right when averaged over the whole stimulus (as in Hill et al. [8]); the pulses should sound, subjectively, like they are “part of” the 30%-amplitude background trilling of their respective streams; finally and most importantly, it should be as easy as possible to focus one’s attention on one stream and ignore the other, there being as little as possible perceptual “binding” between the two streams. The streams’ opposite laterality, their differing carrier, modulation and pulse frequencies, and the temporal offset between the first pulses on each side, all contributed to this.

Before the experiment began, subjects were asked to listen to the stimulus a few times while adjusting the volume of the left and right headphone outputs using two analog sliders. The criteria were that the volume should be comfortable, and that attending to the left stream and ignoring the right should be, subjectively, equally easy as vice versa.

Since our design included a target-counting task, one final aspect of the stimulus design was that a minority of the pulses were longer in duration. The first two pulses on each side were always standard 100-msec pulses. After this, the remaining pulse sequence might contain 1, 2 or 3 target pulses whose duration was 180 msec. The correct number of targets was chosen uniformly, randomly and independently for each stream on each trial. The example stimulus of figure 1 contains 3 targets on the left and 1 on the right.

At the end of the stimulus, the fixation cross was replaced by a question-mark in the centre of the screen. This signalled to the subject that they were free to blink, swallow, and move. At this moment they received acoustic feedback (a single “ding!” of a bell) if the system had correctly classified attention-to-the-left vs. attention-to-the-right using their EEG. The question-mark also signalled that the subject had up to 5 seconds in which to press a key on their numeric keypad, to report how many target stimuli had been in the attended stream. As soon as they pressed the key (or after 5 seconds had elapsed) the screen displayed, for 2 seconds, the correct number of targets in each stream: the numeral on the attended side was green if the subject had responded correctly, red if not. After a 1-2 second pause, the next trial began.

In the final free-choice block, the classification result could not, of course, be judged as “correct” or “incorrect” until after the experiment, so there was no bell sound. To ease the increased complexity of the task (making a free choice and writing it down) we also removed the obligation to press a key and the feedback about the number of targets. Instead, the screen simply reported “interpreted as LEFT” or “interpreted asRIGHT” according to the classifier’s output.

2.3. Hardware and software

A BrainProducts 136-channel QuickAmp was used, in combination with the BCI2000 software platform [38] to acquire signals at 500 Hz from 67 EEG positions, roughly evenly distributed throughout the 10/20 system and mounted on an ElectroCap EEG cap, as well as 3 EOG electrode positions around the left eye: above (EU1), below (EL1) and lateral to the outer canthus (EO1). Impedances were lowered below 5kΩ and unused channels were grounded. The cap used a ground electrode at AFz, and the amplifier applied a builtin common average reference across the 70 biosignal inputs. For all online and offline analyses, the electrodes were re-referenced in software to remove this, using the sparse spatial filter option of BCI2000. The result was 66 EEG signals referenced to linked mastoids ([TP9 + TP10]/2), as well as horizontal and vertical EOG (EO1 − [EU1 + EL1]/2 and EU1 − EL1 respectively).

Auditory stimuli were delivered using 4 independent channels of a multi-channel soundcard: left and right channels to the headphones, plus two channels which were fed via an optical isolator into two auxiliary imputs of the EEG amplifier. These auxiliary channels served to provide a synchronization signal for the timing of the left and right stimuli, in the EEG datastream. Visual stimuli were presented on an LCD monitor at a comfortable distance.

Data were recorded using BCI2000 [38]. Online signal-processing, stimulus generation and stimulus presentation were implemented in Python using the “BCPy2000” add-on to BCI2000 [39]. Offline analysis, and training of classifiers between blocks, was performed using Matlab.

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Online (ERPs)

Online classification was based entirely on event-related potentials, using methods and parameters optimized via the experience gained from analysing the results of Hill et al. [8] offline. First, the re-referenced EEG signals were band-pass filtered using an order-6 Butterworth filter designed to pass frequencies between 0.1 and 8 Hz. Second, following the onset of every pulse in either the left or the right stream, a 600-msec segment or epoch of the filtered EEG signal was cut out and stored in memory. Within each trial, the first two left-pulse responses and the first two right-pulse responses were discarded (on the assumption that the subject might require some time to “lock on” their attention to the correct stream), after which the system maintained a running average XL of the epochs following left-stream pulses, and an average XR of the epochs following right-stream pulses. The difference X = XR − XL, a 68-channel-by-300-sample matrix, was used as a feature set. Every time a new pulse occurred and X changed, a new classifier output was computed by multiplying the elements of X by a set of linear weights. At the end of each trial i, the final X(i) for that trial was written to disk to provide one training exemplar for future classifiers. In the first attention block there was no feedback from the classifier, but after each attention block, a classifier was trained on all the attention data gathered so far, and the resulting weights loaded into the system. Thus, from the second attention block onwards, subjects received feedback about how well their signals could be classified.

Spatial whitening of the data has previously been shown to produce a benefit in linear ERP classification.‡ Therefore, our first step in classification to estimate a 68-by-68-channel spatial covariance matrix Σs from the training data, and whiten the feature representation for each trial i using . The XP(i) were then classified using an L2-regularized linear classifier (for online purposes we used the logistic-regression method), with the regularization parameter being found by 10-fold cross-validation within the training set. The weights found by the classifier in the whitened space (call them MP) were then transformed back to yield weights that can be applied directly to the unwhitened data.

2.4.2. Offline (ERPs and SSAEP)

Further offline analysis of the ERPs used very similar methods to those described above, the only differences being that the preprocessing chain was re-created offline in Matlab, and performance was assessed by 10-fold cross-validation (and since the training procedure itself employed cross-validation for model selection, this resulted in double-nested cross-validation). To examine the potential effect of manipulating the length of a trial, the analysis was repeated using only the first beat of each stream in each trial, only the first two beats, only the first three beats, and so on until all beats were used (unlike the online classification procedure, no beats were discarded).

For offline analysis of the SSAEPs, we cut two segments of the re-referenced multi-channel signal of each trial: a baseline segment measured during visual cue presentation, and a stimulus segment starting 1 second after stimulus onset. The segment length of 1872 milliseconds (i.e. 936 samples) was chosen since it was close to the classification interval length of 2 seconds used by Farquhar et al [23], while being an exact integer multiple of both the amplitude-modulation periods. The SSAEPs induced by sinusoidal amplitude modulation are, themselves, almost pure sinusoids, and stand out very clearly in single components of the Fourier transform when this condition is fulfilled. Since, furthermore, the signal is phase-locked to the stimulation, it is appropriate to use linear preprocessing and classification methods. We follow Farquhar et al. [23] in using a correlation method: for each EEG channel and for each of the two AM frequencies in question, we take the real and imaginary coefficients of the discrete Fourier transform as features (i.e. the correlation coefficients of the segment with a cosine-wave and with a sine-wave, a linear basis for fitting a sinusoid at any phase). This ensures that, as far as possible, only the information from the SSAEPs is being used, to allow their assessment in isolation from that of the ERPs. Once again we classify the features with a linear L2-regularized classifier (logistic regression).

3. Results

3.1. Online Performance

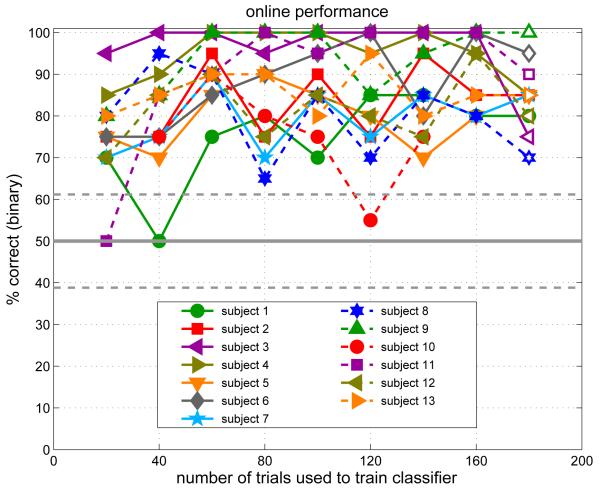

Figure 2 shows the BCI classification performance attained and experienced by the subjects during the experimental session. Since the classifier was retrained after each block of 20 trials, the horizontal axis serves to indicate both the number of training trials and, roughly, the time elapsed during the experimental session. We might expect performance to improve over time as a function of subject learning and of the number of training trials with which the classifier has to work, although we might also anticipate some deterioration of performance over time if the subjects become fatigued. The figure allows us to assess the combined effect of these factors. For many subjects (e.g. subjects 3, 4, 9 and 13) performance appears to reach its peak very quickly, after only 40-60 training trials (i.e. about 10–15 minutes of calibration). For others, such as subject 1 or even the very high-performing subject 6, it may take longer (120 trials, or 30 mins). Only two subjects (8 and 10) appear to show a net decline after reaching an early peak—possibly due to fatigue.

Figure 2.

BCI performance expressed as the percentage of trials classified correctly online. Each point denotes one block of 20 trials. After each block, the classifier was retrained on all the data gathered so far, so the “number of trials” axis is also effectively a time axis. The different symbol shapes/colours correspond to different subjects. Filled symbols denote blocks of cued trials with trial-by-trial feedback, whereas open symbols denote a final “free-choice” block in which subjects wrote down their decisions on paper as they went along. The horizontal tramlines indicate chance classification performance (50%) ±1 standard error for assessing the significance of a single 20-trial block. For assessing the significance of one subject’s results over all 9 data points (180 trials), the tramlines would indicate ±3 standard errors.

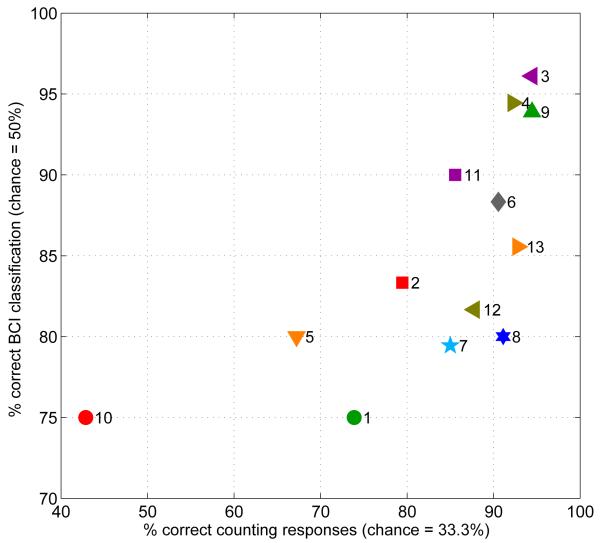

Online performance was then averaged across all 9 blocks for each subject. This performance statistic has a mean of 84.8% and a standard deviation of 7.2% across all 13 subjects. In Figure 3 these values plotted as a function of each subject’s counting accuracy. Overall mean counting accuracy was 82.9% with a standard deviation of 14.6% across subjects. The relationship between the BCI and behavioural measures of attention, though non-linear, is clearly quite monotonic, with a Spearman rank correlation coefficient of 0.79 (n = 13, p = 6 × 10−4). To a large extent, inter-subject variation in BCI performance can therefore be explained by variation in counting performance (see discussion in section 5, below).

Figure 3.

Online BCI classification accuracy for each subject (averaged across all the blocks of figure 2) is plotted against the subjects’ accuracy in reporting the number of target stimuli. Numerals next to the symbols denote (chronological) subject ID numbers. Each subject also has a characteristic symbol shape/colour matching those in figures 2, 4 and 7. Our behavioural measure of attentional performance explains a great deal of the between-subject variation in BCI performance (Spearman’s rank correlation: r = 0.79, n = 13, p = 6 × 10−4).

3.2. Offline Re-analysis (ERPs)

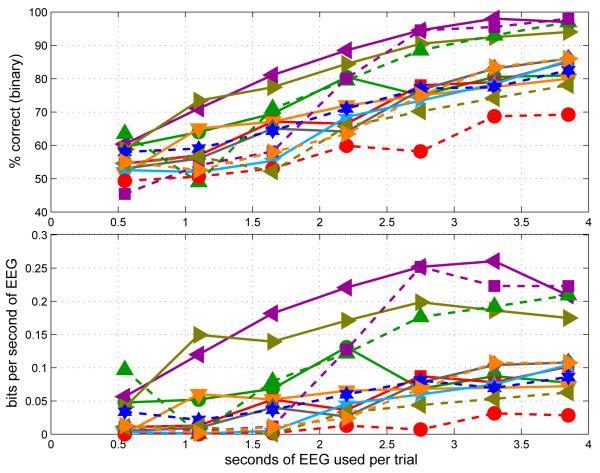

Figure 4 shows hypothetical performance, as estimated by offline cross-validation, as a function of the length of the trial. Disregarding the ceiling effect for the best subjects, % accuracy increases steadily as more stimuli are averaged (upper panel). Accuracy may be traded off for time taken to measure a single trial: this tradeoff is seen in the lower panel, where the same results are expressed as an information transfer rate (ITR), computed in bits per symbol according to the definition presented in Wolpaw et al. [40], then divided by the number of seconds of EEG used per symbol. (Note: we avoid expressing this in bits/min to draw attention to the fact that it is not directly comparable to the ITR frequently reported in bits/min in BCI studies. The latter statistic usuallytakes into account the “overhead” of the inter-trial gaps, which are not meaningful in the context of this analysis.)

Figure 4.

Hypothetical BCI performance estimated by offline cross-validation. In the upper panel, results are expressed as the percentage of trials classified correctly in 10-fold cross-validation, each point being based on the full data set for one subject (200 trials for most; 160 for subject AS). In the lower panel, the same results are re-represented as information transfer rates in bits per second. The different symbol shapes/colours correspond to different subjects. The analysis was performed repeatedly using only the first n beats from each stream in each trial, with n varying from 1 to 7 along the abscissa.

In this view, there seems to be relatively little value added by playing more than 5 pulses on each side, or thereby acquiring more than about 3 seconds of EEG data per trial. (Naturally, this is an upper bound on the amount of useful information that can be transmitted, and may be unrealistic: depending on the level of error-correction that can be built in while retaining usability, any real instantiation of a full BCI+HCI system might achieve less than this maximum, and may benefit from trading off moretime for accuracy than this apparent optimum would suggest.)

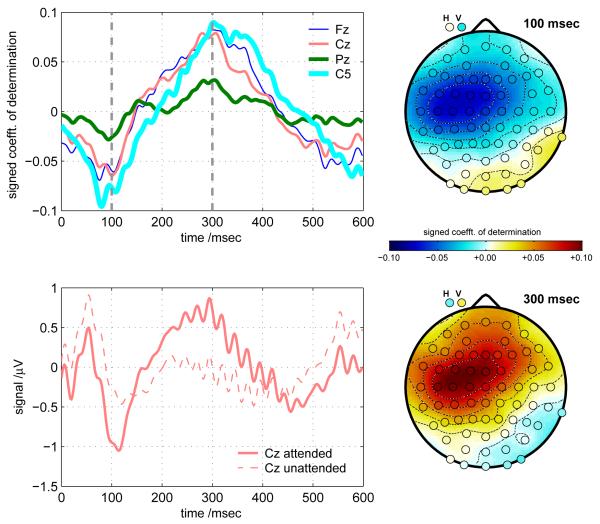

To gain some insight into where and when the useful discriminative information arises in the EEG features, signed coefficients-of-determination (SCD) were computed to measure the extent to which each individual feature separates the two different types of trial (attend-left or attend-right). SCD is also known as “signed r2”, where r is the correlation coefficient, computed across trials, between the feature value in question and the label value (label −1 denoting attend-left or +1 denoting attend-right). r2 can be interpreted as the proportion of variance in label values that the feature in question, considered alone, can account for; and multiplying it by the sign of the original r preserves the direction of the correlation. Figure 5 shows the results. Note that attend-right trials are assigned the larger label value (+1) and the features were computed as XR − XL (response to right-stream stimuli minus response to left-stream stimuli). This means that, making the simplifying assumption of equal variances of XR and XL, we can show that we would obtain identical SCD values for a single subject, up to a scaling factor of , if we were instead to take each XR and XL as a separate data exemplar, and redefine the labels such that we were contrasting responses to attended (+1) vs. unattended (−1) stimuli. If we do this (results not shown) we do in fact obtain results which are qualitatively almost identical to those of figure 5: the figure may therefore alsobe understood, perhaps more intuitively, as indicating the contrast between attended and unattended stimuli. This also means that comparisons between the upper-left panel (where SCDs are shown) and the lower-left (averaged EEG for attended and unattended stimuli) are meaningful.

Figure 5.

Signed coefficients of determination (SCDs, also referred to as signed r2 values), averaged across all 13 subjects. These contrast values illustrate how each feature is correlated with the distinction between attend-right (positive class) and attend-left (negative class) trials. The SCD values were computed from a space consisting of 68 channels × 300 time-samples: each feature value denotes the response averaged for all right-stream stimuli in a given trial (targets and non-targets) minus the response averaged for all left-stream stimuli (targets and non-targes) in the same trial. The upper left panel shows the time-course of the SCD values at 4 different EEG channels, from time t = 0 (the moment of stimulus presentation) to t = +600 msec. The scalp maps show the spatial distributions of SCD values across the EEG montage, at the two instants t = +100 msec and t = +300 msec. The horizontal and vertical EOG channels are marked H and V, respectively. The lower left panel shows the EEG signal at Cz bandpass-filtered between 0.1 Hz and 45 Hz, time-locked to attended and unattended stimuli (averaged across all stimuli, both streams, and all subjects).

The figure shows four temporal and two spatial views of the discriminative information, from SCD values that have been averaged across all subjects. One must be cautious in interpreting the patterns, because of overlap effects: every stimulus-locked average is polluted by responses to previous and subsequent stimuli from the opposite stream (however, because of the phase drift between attended and unattended sides, the pollution is not time-locked to t = 0 in the average and is therefore somewhat attenuated relative to responses to the stimuli whose onset is at t = 0). There is a negative peak which appears at Cz/Fz at around 100 msec after stimulus presentation (this actually tended to be lateralized to the left, and tended to originate a little earlier and more lateralized, as reflected by the C5 trace). There is also a positive component originating fronto-centrally around 200 msec and evolving into an (also slightly left-lateralized) 250-400 msec peak.

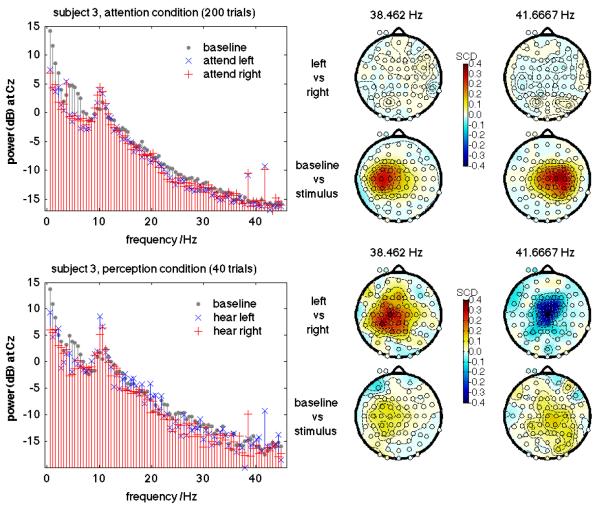

3.3. Offline Analysis (SSAEPs)

Figure 6 shows the SSAEP signals from one example subject (subject 3, the best performer in ERP-based BCI). The spectra are computed at Cz, referenced to linked mastoids. With a window length carefully chosen to contain an integer number of cycles of both amplitude-modulation signals, the two SSAEPs components stand out very sharply in the power spectrum as estimated by an FFT on a rectangular-windowed segment. For the purposes of this illustration the log power was computed at the two precise SSAEP frequencies across the whole mastoid-referenced scalp montage. Then, SCD scores (see section 3.2) were computed for these features, to show the degree to which each feature can be used to separate baseline from stimulus segments (2nd and 4th row of scalp plots) or attend-left vs. attend-right segments (1st and 3rd row of scalp plots). The scalp distribution of the SSAEPs is somewhat lateralized, centred roughly on C3 and C4, contralateral to the ear to which the corresponding stimulus component was presented. There was no such pattern of features, and very poor overall separation, when attempting to separate attend-left vs. attend-right conditions (top row).

Figure 6.

Steady-state auditory evoked potentials (SSAEPs) for one example subject—the best-performing subject in the ERP-based BCI. The upper half of the figure shows the attention condition (200 trials), and the lower half shows the perception condition (40 trials). In the leftmost plots, averaged power spectra at Cz are shown for the silent baseline (grey dots), attend-left (blue x) and attend-right (red +) time intervals. The scalp maps all show the signed coefficient of determination (SCD, also known as signed r2) for individual spectral power features in separating left trials from right trials, or baseline periods from stimulus periods. For the purposes of illustration, power values are computed without spatial filtering, from signals referenced to the mastoids.

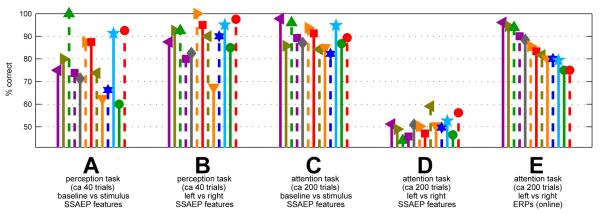

Figure 7 presents a summary of the results for all the subjects, showing that the pattern illustrated with subject 3 is consistently repeated. The FFT coefficients at the precise amplitude-modulation frequencies could be used to classify baseline vs. stimulus segments at about 89.5% correct (±4.9% across subjects) in offline cross-validation (group C in the figure). They could also be used to classify listen-right trials from listen-left trials in the perception-only condition, where the unattended stream was silent, at 88.8%±8.6 (group B; the increased variability can be attributed to the smaller number of trials collected in this condition). However, the same feature extraction and classification procedures could not be used to solve the BCI problem of discriminatingthe attended side when both streams were audible (50.2% ± 4.2, group D), despite the proven ability of the subjects to modulate their ERPs by shifting their attention to the same stimuli (84.8% ± 7.2, group E).

Figure 7.

Classification results. Groups A through D show classification using SSAEP features only (FFT coefficients at the precisely-known SSAEP frequencies). A and B show results from the “perception” condition where the unattended stimulus stream was silent, whereas C and D reflect the normal attention condition. A and C show performance in distinguishing stimulus-presentation periods from baseline (silence) periods, whereas A and D show performance in identifying which of the two stimulus streams, left or right, was attended. Each subject is shown individually with his or her unique symbol shape and colour, and within each group the subjects are ordered from left to right in decreasing order of the online (ERP-based) BCI performance they achieved using the very same stimuli. For comparison, these ERP-based BCI performance values are shown in group E.

3.4. Subjective user reports

The following subjective phenomena were each reported, unprompted, by three or more of the subjects:

Subjects reported that the counting task seemed helpful as a tool for focusing attention at the beginning of the session, but that gradually (as the trial-by-trial feedback became more accurate and the subject grew more accustomed to it) it became redundant. The latter observation is partially supported by the results of the final free-choice block in which counting was made optional: some subjects reported that they had not bothered to count, yet overall BCI accuracy was not significantly lower than in previous blocks.

Subjects made statements like “I knew I had done well/not so well on many of the trials, even before the bell” suggesting that after a few blocks of trial-by-trial BCI feedback, there was strong sense of being able to evaluate one’s own attention-shifting performance to a degree that seemed correlated with the BCI’s evaluation.

More-rigorous support for these unlooked-for subjective observations may be a valuable aspect of future studies.

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate that attentional shifts to dichotically presented auditory streams are a feasible basis for an effective online binary-choice BCI, in which high single-trial accuracy can be achieved within a few seconds per trial.

The ERP-based BCI appears to rely on early (N1) as well as later (P3) components. The usefulness of the N1 component is consistent with the observation of attention-modulation of the N1 component by Hillyard et al. [16], and is an encouraging sign that BCIs might be constructed using every stimulus in a periodic sequence, rather than necessarily having to rely on, (and wait for) a smaller number of less-frequent “oddball” stimuli, on which purely-P3-driven stimulus designs are traditionally assumed to rely.

4.1. Performance comparison with other auditory-ERP studies

Our subjects’ average online accuracy of 84.8% is very slightly higher than the 82.4% that was predicted by the best analysis method in our previous offline study [8].

Unfortunately we cannot compare against the results of Kanoh et al. [12], since the latter authors only reported offline accuracies in which “all the measured responses were used as both sample and test data” (ibid. p38). We interpret this to mean performance was measured on the classifier’s own training set and was therefore a drastically inflated performance measure.

Our results can be compared with those of Halder et al. [13] if we convert to information transfer rate (ITR). Computing ITR for each subject separately before averaging, we obtain a mean of 0.415 bits/trial with a standard deviation of 0.195 across subjects. Following Halder et al.’s convention of taking into account only the time used to play the stimulus and discarding inter-trial gaps, we obtain 4.98 bits/min ± 2.3. This is twice the mean ITR of 2.46 bits/min reported in the best condition in Halder et al.’s table 3, which in turn exceeds all the other auditory studies reviewed in that table. Our interpretation of this performance difference highlights an important point about streaming designs. In a streaming design, subjects may be asked to discriminate between “targets” and “non-targets”, or they may not. If they do so, as in the current study, then this has the advantage of providing a concrete strategy and incentive for shifting attention, and an opportunity for the experimenter to verify the level of attention using a behavioural response. However, the target-non-target contrast is not a necessary part of the BCI design, and it is not solely the brain response to the target stimulus that is important in classification. Rather, as Hilyard’s original paper also reported, attention modulates the response to every stimulus that the user is monitoring (assessing it, if required to do so, as target or non-target) relative to the responses to the stimuli in the stream the user is ignoring. This has the advantage that the system does not need to wait for an infrequent “oddball” target before updating its interpretation of the user’s attentional state: a meaningful update to the BCI system’s output could be made, and assessed to see whether enough information has been gathered to make a decision, every time a stimulus is presented (roughly twice per second in the current stimulusdesign). Seen in this light, the Halder et al. study had the worst of both worlds: it was a sequential rather than a streaming design (so the system has to wait for the target) but had only two classes of target, plus a majority of unused non-targets.

It is possible, however, to take advantage of the non-targets by diversifying them into multiple classes. To compare our study with multi-class sequential designs, however, one must be aware that the performance metric is usually different from that used above, because such systems are usually assessed in the context of a more complex real-world task. Before pruning their subject group to select only the better subjects, Schreuder et al. [19] report a mean ITR of 2.84 bit/min across all their 21 subjects. Note that the metric now includes the time taken outside of stimulus presentation, i.e. the “overhead” of following cues and choosing a letter in a real, practical task—something for which neither our minimal two-class experiment, nor that of Halder et al. has any analog. Our subjects performed an average of 4 trials per minute: one trial every 15 seconds on average, of which the stimulus was played for 5 seconds. To match the mean ITR of Schreuder et al. our subjects would have had to perform 6.84 trials per minute (5 seconds’ stimuli out of every 8.8 sec). While this might easily have been possible with our task (healthy subjects mindlessly repeating left-right choices that are prescribed for them) it would be a considerable challenge to design a communication interface based on free binary choices, including all the necessary auditory prompts and feedback, that could achieve this. For communication, binary BCIs will probably only be the preferred choice for users who are unable to use a more complicated speller.

4.2. Implications for SSAEP BCIs

Our results also provide evidence that SSAEPs are a much poorer neural basis for attention-based BCI than auditory ERPs. Furthermore it seems unlikely that the negative finding in this study (and hence probably also the previous negative finding of Farquhar et al. [23]) can be attributed to an inadequate attention-task design, since exactly the same stimuli that elicited the SSAEPs also, simultaneously, elicited ERPs that were very successfully modulated by attention. Although SSAEP features could clearly be seen, and could easily be used to detect which of the two stimuli was heard, there was absoutely no evidence that they could be used to detect attention: SSAEP classifier performance did not tend to predict even the rank-order of the subjects’ attention-modulation ability, as measured either behaviourally by the counting task or electrophysiologically by their ERP-based BCI performance.

From the current results, one might even conclude that absolutely no attention-modulation of SSAEP is detectable on a practicable single-trial basis. Recent results, however, taken together with the literature reviewed in the introduction, suggest that this cannot be entirely true: Kim et al. [37] played 20-second-long trials consisting of two-stream amplitude-modulated stereo sound, used FFT features from EEG measured from only 4 electrodes, and showed that one pilot subject may have been able to use attention-modulation for online BCI selection, obtaining 10 correct trials out of 14. Notethat this is only tentative positive evidence: this online performance of 71.4% is only 1.6 standard-errors above chance (under the null hypothesis of probability correct=0.5, standard error would be ). Offline results from the same study are also moderately encouraging: averaged over 6 subjects each performing 50 trials, percentage accuracy in cross-validated offline tests ranged from the low 70’s to the mid 80’s depending on the feature representation in use, provided the stimulus length was 10 seconds or more. (Note, however, that since their offline analysis methods did not appear to use double-nested cross-validation, it is not appropriate to take the averaged-across-subjects maximum-across-feature-sets performance of 86.3% as a fair indication of expected generalization performance.) Despite their relative statistical weakness, these results are suggestive of significant attention-modulation of SSAEP, of the kind that might be harnessed for BCI, even if the strength of the effect is inferior to the attention-modulation of ERPs. The minor differences between Kim et al. [37] and the current study are too many to be able to pin down the reason for this difference in findings exactly: the different numbers of electrodes, the use of speakers in free field instead of dichotic listening through headphones, the constant rather than pulsed envelope the stimuli and (the most likely influential factor) the much longer stimulus durations, may all play a role which bears closer investigation.

5. Outlook

As in most BCI systems, accuracy varies widely from subject to subject—however, we have evidence that this variation can in large part be explained by the subject’s ability (or perhaps motivation) to focus attention on the stimuli, as indicated by our behavioural measure of counting performance. This is somewhat unusual in the BCI literature: although most BCI studies report large inter-subject variation, it is rare for the design to include an independent behavioural test of attention. The finding raises the hope that BCI performance for many poorer-performing subjects could be improved considerably by training, since clearly there is still a behavioural learning-curve that the poorer BCI performers can attempt to climb. Furthermore, the design of the system allows for a quantitative measure of auditory attention to be computed online and updated almost in real time—roughly 3-4 times per second in the current design, although this output signal would need to be smoothed. Such a signal could be fed back to the subject, perhaps as a visual or tactile stimulus: this would potentially breathe life into neurofeedback methodologies for improving attention, now based on direct, immediate correlates of performance in an attention-driven task, i.e. the attention-modulation of brain responses to specific stimuli, in contrast to more traditional approaches that train the amplitude of oscillatory components known to be correlated indirectly with attention-task performance [see for example 41, 42]. The effectiveness of this kind of neurofeedback (as compared to ordinary behavioural training on the same counting task) remains to be tested. Favourable results in such a comparison might establish auditory-streaming BCI as a valuable tool outside the sphere of BCI-for-communication. Oneexample of its application might be as a treatment for people who have specific difficulty with dichotic listening and auditory attention tasks, as in some cases of central auditory processing disorder (CAPD) [43]. Another might be as a training tool—for example for people in occupations such as simultaneous interpreting [44], that require dichotic listening skills or other forms of selective attention in “cocktail-party”-style acoustic environments.

Future extensions of the current paradigm might investigate:

whether stimuli can be speeded up without sacrificing performance, to yield a larger information transfer rate;

whether the stimuli are suitable for an older population, more matched to the demographics of the target population of people in the totally-locked-in state;

whether other, more-pleasant or more-intuitive stimuli (e.g. voices repeating task-relevant pairs of words such as “yes” and “no”) might be used without sacrificing performance;

to what extent usability and performance are served by an adaptive stopping mechanism, whereby stimuli continue indefinitely until the classifier has enough confidence in its output on each trial (this is related to the question of how well the no-intentional-control brain state can be distinguished from the brain states corresponding to left-selection and right-selection).

Further development of the system will also require integration of the BCI-based left-right selection into a comprehensive human-computer interface based on binary decision trees, through which a user might spell, or control other systems such as domotic control interfaces that are useful for the target population. Integration of the BCI described here into such a wider system would provide a valuable expansion of communication and control possibilities for people who are paralysed and (hence, or otherwise) have limited vision.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Max Planck Gesellschaft, and by the NIH (NIBIB; EB00856). The authors would like to thank Bernd Battes for his excellent work as lab technician and all-round EEG troubleshooter, and for coordinating with subjects and gathering the data. We would also like to thank Peter Desain and Jason Farquhar for helpful discussions during the development of the paradigm.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. None of the material presented in this manuscript has been published or is under consideration elsewhere, including the Internet.

Comparing the fourth and sixth columns of Table 1 of Hill et al. [8], we can compare offline classification accuracies immediately before and immediately after applying the FastICA algorithm to the data. The percentage-point improvement from applying FastICA was 4.0 on average, with standard error 1.0 across 15 subjects. Since FastICA consists of a PCA whitening step followed by a rotation in the electrode space, and since L2-regularized classifiers are invariant to such rotations, this performance improvement reflects what can be achieved by spatial whitening alone—a fact which our experiments in offline data analysis (results not shown here) have confirmed for both the 2005 data and the current data.

References

- [1].Birbaumer N, Ghanayim N, Hinterberger T, Iversen I, Kotchoubey B, Kübler a, Perelmouter J, Taub E, Flor H. A spelling device for the paralysed. Nature. 1999;398(6725):297–8. doi: 10.1038/18581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Birbaumer N, Murguialday AR, Cohen L. Brain-computer interface in paralysis. Current opinion in neurology. 2008;21(6):634–8. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328315ee2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Naito M, Michioka Y, Ozawa K, Ito Y, Kiguchi M, Kanazawa T. A Communication Means for Totally Locked-in ALS Patients Based on Changes in Cerebral Blood Volume Measured with Near-Infrared Light. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems. 2007;E90-D(7):1028–1037. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Farwell LA, Donchin E. Talking off the top of your head: toward a mental prosthesis utilizing event-related brain potentials. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1988;70(6):510–523. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(88)90149-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Donchin E, Spencer KM, Wijesinghe R. The mental prosthesis: assessing the speed of a P300-based brain-computer interface. IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering. 2000;8(2):174–9. doi: 10.1109/86.847808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Müller-Putz GR, Scherer R, Neuper C, Pfurtscheller G. Steady-state somatosensory evoked potentials: suitable brain signals for brain-computer interfaces? IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 2006;14(1):30–7. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2005.863842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Brouwer A-M, van Erp JBF. A tactile P300 brain-computer interface. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2010 May;4:19. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hill NJ, Lal TN, Bierig K, Birbaumer N, Schölkopf B. An Auditory Paradigm for Brain-Computer Interfaces. In: Saul LK, Weiss Y, Bottou L, editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 17. Vol. 17. 2005. pp. 569–576. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sellers EW, Donchin E. A P300-based brain-computer interface: initial tests by ALS patients. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2006;117(3):538–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Furdea A, Halder S, Krusienski D, Bross D, Nijboer F, Birbaumer N, Kübler A. An auditory oddball (P300) spelling system for brain-computer interfaces. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(3):617–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Klobassa DS, Vaughan TM, Brunner P, Schwartz NE, Wolpaw JR, Neuper C, Sellers EW. Toward a high-throughput auditory P300-based brain-computer interface. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2009;120(7):1252–61. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kanoh S, Miyamoto K.-i., Yoshinobu T. A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) System Based on Auditory Stream Segregation. Journal of Biomechanical Science and Engineering. 2010;5(1):32–40. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4649234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Halder S, Rea M, Andreoni R, Nijboer F, Hammer E, Kleih S, Birbaumer N, Kübler A. An auditory oddball braincomputer interface for binary choices. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2010;121(4):516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schreuder M, Blankertz B, Tangermann M. A new auditory multi-class brain-computer interface paradigm: spatial hearing as an informative cue. PloS ONE. 2010;5(4):e9813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Höhne J, Schreuder M, Blankertz B, Tangermann M. A novel 9-class auditory ERP paradigm driving a predictive text entry system. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2011;5:99. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hillyard SA, Hink RF, Schwent VL, Picton TW. Electrical Signs of Selective Attention in the Human Brain. Science. 1973;182(4108):177–180. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4108.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kübler A, Furdea A, Halder S, Hammer EM, Nijboer F, Kotchoubey B. A Brain-Computer Interface Controlled Auditory Event-Related Potential (P300) Spelling System for Locked-In Patients. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1157(1):90–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.04122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schreuder EM, Tangermann M, Blankertz B. Initial results of a high-speed spatial auditory BCI. International Journal of Bioelectromagnetism. 2009;11(2):105–109. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schreuder M, Rost T, Tangermann M. Listen, you are writing! Speeding up online spelling with a dynamic auditory BCI. Frontiers in Neuroprosthetics. 2011 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00112. page (submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Belitski a, Farquhar J, Desain P. P300 audio-visual speller. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2011;8(2):025022. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/8/2/025022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Höhne J, Schreuder M, Blankertz B, Tangermann M. Two-dimensional auditory p300 speller with predictive text system; Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; 2010; pp. 4185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kallenberg M. Masters Thesis. Radboud University Nijmegen; 2006. Auditory Selective Attention as a method for a Brain Computer Interface. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Farquhar J, Blankespoor J, Vlek R, Desain P. Towards a Noise-Tagging Auditory BCI-Paradigm; Proceedings of the 4th International Brain-Computer Interface Workshop and Training Course; 2008.pp. 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Galambos R, Makeig S, Talmachoff PJ. A 40-Hz auditory potential recorded from the human scalp. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1981;78(4):2643–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Liégeois-Chauvel C, Lorenzi C, Trébuchon A, Régis J, Chauvel P. Temporal Envelope Processing in the Human Left and Right Auditory Cortices. Cerebral Cortex. 2004;14:731–740. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ross B, Borgmann C, Draganova R, Roberts LE, Pantev C. A high-precision magnetoencephalographic study of human auditory steady-state responses to amplitude-modulated tones. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2000;108(2):679–91. doi: 10.1121/1.429600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cheng M, Gao X, Gao S, Xu D. Design and implementation of a brain-computer interface with high transfer rates. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2002;49(10):1181–6. doi: 10.1109/tbme.2002.803536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kelly SP, Lalor EC, Finucane C, McDarby G, Reilly RB. Visual spatial attention control in an independent brain-computer interface. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2005;52(9):1588–96. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2005.851510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Allison BZ, McFarland DJ, Schalk G, Zheng SD, Jackson MM, Wolpaw JR. Towards an independent brain-computer interface using steady state visual evoked potentials. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008;119(2):399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.09.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhang D, Maye A, Gao X, Hong B, Engel AK, Gao S. An independent brain computer interface using covert non-spatial visual selective attention. Journal of Neural Engineering. 2010;7:016010. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/7/1/016010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Linden R, Picton T, Hamel G, Campbell K. Human auditory steady-state evoked potentials during selective attention. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1987;66:145–159. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(87)90184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ross B, Picton TW, Herdman AT, Pantev C. The effect of attention on the auditory steady-state response. Neurology & Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bidet-Caulet A, Fischer C, Besle J, Aguera P-E, Giard M-H, Bertrand O. Effects of selective attention on the electrophysiological representation of concurrent sounds in the human auditory cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(35):9252–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1402-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Müller N, Schlee W, Hartmann T, Lorenz I, Weisz N. Top-down modulation of the auditory steady-state response in a task-switch paradigm. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2009;3:1–9. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.001.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Skosnik PD, Krishnan GP, O’Donnell BF. The effect of selective attention on the gamma-band auditory steady-state response. Neuroscience Letters. 2007;420(3):223–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lopez M.-a, Pomares H, Pelayo F, Urquiza J, Perez J. Evidences of cognitive effects over auditory steady-state responses by means of artificial neural networks and its use in braincomputer interfaces. Neurocomputing. 2009;72(16-18):3617–3623. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kim D-W, Hwang H-J, Lim J-H, Lee Y-H, Jung K-Y, Im C-H. Classification of Selective Attention to Auditory Stimuli: Toward Vision-free Brain-Computer Interfacing. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2011;197(1):180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Schalk G, McFarland D, Hinterberger T, Birbaumer N, Wolpaw J. BCI2000: a general-purpose brain-computer interface (BCI) system. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2004;51(6):1034–1043. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2004.827072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hill NJ, Schreiner T, Puzicha C, Farquhar J. BCPy2000. 2007 http://bci2000.org/downloads/BCPy2000. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wolpaw JR, Ramoser H, McFarland DJ, Pfurtscheller G. EEG-based communication: improved accuracy by response verification. IEEE Transactions on Rehabilitation Engineering. 1998;6(3):326–33. doi: 10.1109/86.712231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lubar JF, Swartwood MO, Swartwood JN, Timmermann DL. Quantitative EEG and Auditory Event-Related Potentials in the Evaluation of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder : Effects of Methylphenidate and Implications for Neurofeedback Training. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, ADHD Speci. 1995:143–160. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fuchs T, Birbaumer N, Lutzenberger W, Gruzelier JH, Kaiser J. Neurofeedback treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children: a comparison with methylphenidate. Applied psychophysiology and biofeedback. 2003;28(1):1–12. doi: 10.1023/a:1022353731579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].ASHA . ( Central ) Auditory Processing Disorders. Technical Report of the The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lambert S. Simultaneous interpreters : One ear may be better than two. TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction. 1989;2(1):153–162. [Google Scholar]